Well-papered Edwardian Boston

Boston’s “Newspaper Row’’ in 1910, when the city had seven daily papers.

The University of Maine’s ‘factory of the future’

Edited from a New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com) message

“The University of Maine has been approved for $35 million in funding to build a new digital research laboratory. These funds were made possible under the omnibus spending bill that President Biden recently signed into law last week. This facility is an initiative of UMaine’s Advanced Structures and Composites Center and is a “factory of the future,” according to UMaine. It is being created to advance “large-scale, bio-based {material from living or once-living sources} additive manufacturing,” using technologies such as artificial intelligence and 3D printers.

“The cost of building this facility is expected to total $75 million. According to the university, the center’s new capabilities could lead to technology development in the affordable-housing industry, clean energy, transportation industry and more.’’

Llewellyn King: We must face the fact that world crises in food, inflation and energy require tough decisions and new thinking

Messengers going to Job, each with bad news.

— 1860 woodcut by Julius Schnorr von Karolsfeld

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

There is a rough road ahead for the world and our political class isn’t leveling with us.

As Steve Odland, president and CEO of The Conference Board, one of the nation’s premier business-research organizations, said in a television interview, serious inflation will continue at least until 2024, and longer if things continue to deteriorate with supply-chain crises and the war in Ukraine.

Particularly, Odland, who also serves as a director of General Mills Inc., fears a global food crisis with famine in Africa and many other vulnerable places if Ukrainian farmers don’t start seeding spring crops to start this year’s harvest. Already, Ukraine – once known as one of the world’s breadbaskets -- has cut off exports to make sure that there is enough food for their own people, as war rages.

Odland sees U.S. inflation continuing at 7 to 8 percent for several years at best. But his primary worry is global food supplies, as countries face a crisis of new and frightening proportions.

His second worry is stagflation. If the rate of productivity falls below 3 percent, “then we will have stagflation,” Odland told me during a recording of White House Chronicle, on PBS, the weekly news and public affairs program I produce and host.

Odland faults the Federal Reserve for being timid in raising interest rates to counter inflation.

I fault the political class for not leveling with us – both parties. As we are in a state of perpetual election fervor, we are also in a state of perpetual happy talk. “Get the rascals out, and all will be well when my band of happy angels will fix things.” That is what the political class says, and it is a lie.

We are in for a long and difficult period which began with the pandemic that disrupted supply chains and set off inflation, and now the war in Ukraine has compounded that. Supply chains won’t magically return to where they were before COVID-19 struck, and more likely they will have further constrictions because of the war. New supply chains need to be forged and that will take time.

For example, nickel, which is used in the batteries that are reshaping the worlds of electricity and transportation and for stainless steel, will have to come from places other than Russia. At present, Russia supplies 20 percent of the world’s voracious appetite for high-purity nickel. Opening new mines and expanding old ones will take time.

The world’s largest challenge is going to be food: starvation in many poor countries and high prices at the supermarkets in the rich ones, including the United States. There are technological and alternative supply fixes for everything else, but they will take time. Food shortages will hit early and will continue while the world’s farms adjust. There will be suffering and death from famine.

The curtailing of Russian exports will affect the United States in multiple ways, some of which might eventually turn out to be beneficial as the creative muscle is flexed.

In the utility industry, someone who is thinking big and boldly is Duane Highley, president and CEO of Tri-State Generation and Transmission Association in Denver.

Highley told Digital 360, the weekly webinar that emanates from Texas State University in San Marcos, the challenging problem of electricity storage could be solved not with lithium-ion batteries, but with iron-air batteries.

In its simplest form, an iron-air battery harnesses the process of rusting to store electricity. The process of rusting is used to produce power when it is exposed to oxygen captured on site. To charge the battery, an electric current reverses the process and returns the rust to iron.

Clearly, as Highley said, this won’t work for electric vehicles because of the weight of iron. But in utility operations, these batteries could offer the possibility of very long drawdown times --not just four hours, as with current lithium-ion batteries. And there is plenty of iron stateside.

Another Highley concept is that instead of dealing with all the complexities of transporting hydrogen, it should be stored as ammonia, which is more easily handled.

This isn’t magical thinking, but the kind of thinking which will lead us back to normal -- someday.

Politicians should stop the happy talk and tell us what we are facing.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C

It all depends on what you mean by ‘new’

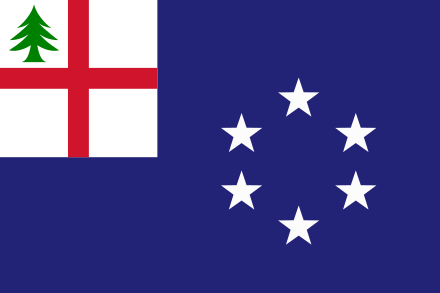

The New England Flag.

“New England is the illegitimate child of Old England….It is England and Scotland again in miniature and in childhood.’’

Calvin Colton, in Manual for Emigrants to America (1832)

xxx

“Of course what the man from Mars will find out first about New England is that it is neither new nor very much like England.’’

— John Gunther, in Inside U.S.A. (1947)

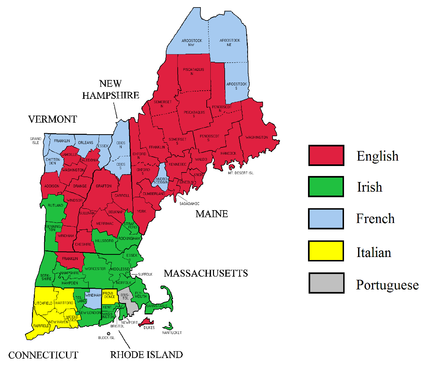

New England by background ethnicity

Better go by land

“River Currents” (oil on panel), by Cambridge, Mass.-based artist Wendy Prellwitz at Alpers Fine Art, Andover, Mass.

Go Green Airport! fight Putin by shrinking your car

In Green Airport’s terminal lobby

— Photo by Antony-22

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

There’s at least some good news -- locally. After years in which businesses and individuals have pleaded for nonstop air service between Rhode Island T.F. Green International Airport and the West Coast, Breeze Airways has announced that it will start twice-a-week service to Los Angeles in late June. The initial plan is only for summer service, but obviously that would change fast if demand shows the need for it to be year-round. I think that will happen. T.F. Green serves a large and densely populated area and is a pleasant alternative to braving the nasty traffic to Boston’s Logan International Airport.

Other new, twice-weekly destinations to be offered soon will be Columbus, Jacksonville, Savannah and Richmond, though Savannah will, like L.A., be summer-only to start.

Kudos to the folks at the Rhode Island Airport Corporation for pulling this off.

However, given the international situation, I doubt that new flights from Green, or indeed other airports, to foreign places are in the offing.

With a mass-murdering tyrant on the loose in Europe and, as a result, aviation and other fuel prices likely to rise even more; a recession possible, and COVID still hovering, all plans can be seen as even more imaginary than usual these days.

On those fuel prices, will Americans finally embrace smaller, fuel-efficient gasoline-powered cars and/or electric or hybrid cars instead of gas-guzzling pickup trucks and SUVs (which most people buy on credit)? Probably not….

If you want to make a patriotic gesture, get a smaller car.

1957 Heinkel Kabine bubble car

— Photo by Lothar Spurzem

When the worst of the current crisis is over, Congress should (but probably won’t have courage to) raise the federal gas tax from its present 18.4 cents a gallon -- set in 1993! -- to discourage gasoline-fueled driving, accelerate electric-vehicle use and use some of the money to aid lower-income people to deal with higher energy costs; the last thing was done in the 2008-2009 recession.

Federal payments to individuals under the Biden administration’s $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan last year have softened the blow: Far more people than usual have hefty savings. (The law of unintended consequences!)

Raising the gas tax would not only reduce the power of tyrannical and corrupt petrostates such as Russia and Saudi Arabia, whose fossil-fuel sales finance their crimes; it would also weaken over time the pricing power of American oil companies, which are now gleefully profiteering from the world crisis.

America would be in safer shape today if we had raised the gas tax long ago.

Total average U.S. state and federal gasoline taxes were 52 cents a gallon in 2019, compared to an average of $2.24 in other industrialized countries.

Oh, yes. There’s also that not-very-slow-moving catastrophe called global warming from burning fossil fuel, which we’ll still have to do lots of for some years to come. And indeed, for a couple of years we’ll probably have to extract more U.S. oil and gas than before the current world security crisis, made possible, ironically, in part by our addiction to fossil fuel.

Of course, the gasoline-cost surge will also encourage a reversal in the back-to-the office migration that has accompanied the waning (for now) of the COVID pandemic. Far too many Americans live in exurbs and suburbs far from their workplaces, and they drive gas-guzzlers. Putin has given them a good reason to go back to Zooming, in a new blow to downtowns

xxx

Note: The cost of energy from wind-power has gone up 0 percent since the current energy crisis started.

‘Feelings that art can restore’

“Multiple Phantasms” (encaustic wax, Fiber Clay, slinky), by Cheshire, Conn.-based artist Ruth Sack.

She says:

“Phantasmagoria: A bizarre or fantastic combination, collection, or assemblage.

“I slid down the tongue of a giant monster and emerged exultant. The monster was a play structure by Niki de Sainte Phalle called ‘Golem.’ I have since created my own whimsical artworks in order to spark that same thrill. The sculptures in this exhibit are inspired by Saint Phalle in pursuit of that excitement. I am as thrilled moving through a gigantic sculpture as I am when making a piece of art that delights me. These are the sort of feelings that have been quashed by the pandemic. These are the sort of feelings that art can restore.

“These works are part of a series called ‘Phantasmagoria.’ They have evolved from earlier coiled sculptures that evoked letterforms and primitive symbols. With the addition of organic shapes and detailed patterns, these pieces started to resemble lifelike characters. Each sculpture appears to be transitioning from an abstract form into an animated figure. This metamorphosis can summon thoughts of mythology and contemporary tales.’’

In Cheshire, from left to right: Cheshire Town Hall, Congregational Church, Historical Society, and Civil War memorial. The town also has a large bomb shelter under an AT&T tower. Given Russian mass murderer Putin’s tendencies, it may come in handy.

Roaring Brook Falls in Cheshire.

David Warsh: Knowledge and skepticism about the causes of inflation

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

In their introduction to the conference volume Knowledge and Skepticism, its editors wrote that there are two main questions worth asking in epistemology. What is knowledge? And, do we have any of it? Their formulation has often come to mind these days in connection with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but it has also welled-up in my thinking in connection with a very different matter, the phenomenon of inflation.

Charles Goodhart is a central banker’s expert on central banking. Having completed his PhD at Harvard University, in 1963, he worked for seventeen years as an adviser to the Bank of England on domestic monetary policy, during the tumultuous but ultimately successful battles in Britain and the United States against global inflation, all the while pursuing a thorough examination of the rationale for bank regulation in the first place.

In The Evolution of Central Banking (1988), he traced the history of the most important and least understood regulatory institution of modern government, and for the next thirty years remained in the forefront of the discussion of supervision of the world banking system.

Then, in 2020, with Manoj Pradhan, the 84-year-old Goodhart published The Great Demographic Reversal: Ageing Societies, Waning Inequality, and an Inflation Revival, arguing that that, owing to declining fertility rates in China and the West, the coronavirus pandemic has marked a watershed between the deflationary forces of the last thirty or forty years and a coming twenty years or so of rising prices. A headline of a recent story on the front page of The Wall Street Journal conveyed the story:

Will Inflation Stay High for Decades? One Influential Economist Says Yes

Charles Goodhart sees an era of inexpensive labor giving way to years of worker shortages—and higher prices. Central bankers around the world are listening.

Goodhart predicts that inflation in advanced economies will settle at 3 percent to 4 percent around the end of 2022 and remain at that level for decades, wrote WSJ reporter Tom Fairless, as opposed to about 1.5 percent in the decade before the pandemic, with interest rates correspondingly higher. The Black Death, a 14th Century pandemic, had triggered a similar quarter-century of soaring wages and rising prices, he observed. You can read Fairless’s story yourself, thanks to this free link.

The question is, if Goodhart is right, what should central bankers do about it? Ever since he first presented his findings to a meeting of central bankers in 2016, monetary policy specialists representing various interests and points of view have been arguing about it. “Lower for Longer, ‘‘the latest report of the technical advisory committee of the European Systemic Risk Boars, takes Goodhart’s argument into account and differs sharply.

Among the experts exists a 400- year-old difference of opinion, known by different names at different times, of which Keynesian and Monetarist or Freshwater Saltwater are only the most recent. Some conclude that making appropriate policy is relatively easy: Simply require the central bank to control the supply of money. Others say central bankers’ job is difficult. John Greenwood and Steve H. Hanke, of Johns Hopkins University, put it this way in a recent Journal of Corporate Finance,

There have always been two types of explanations for inflation: ad hoc explanations and monetary explanations. Historically, the ad hoc explanations have been in terms of special factors present on particular occasions: commodity price increases due to bad harvests, supply disruptions due to restrictions on international trade, profiteers or monopolists holding back scarce goods, or trades unions pushing up wages leading to a wage-price spiral or cost-push pressures, and so on in great variety. Even the widely used aggregate demand-aggregate supply model is a species of ad hoc explanation in the sense that it relies on idiosyncratic factors driving estimates of the output gap or special factors affecting the supply of labor or productivity.

The monetary explanations for inflation have focused on increases in the quantity of money: either new discoveries of gold and silver in centuries past, or fiat money creation by the banking system or by the central bank in modern times.

I am an economic journalist, not an economist, and to my mind, there has always seemed something a circular about the shorthand explanation of rising prices, to the effect that “inflation is a matter of too much money chasing too few goods.” By making “rising prices” of goods synonymous with “inflation” of the quantity of money, the language of the shorthand assumes its own truth, and gives short shrift to the changing nature of “goods.” What about the declining fertility rate in China and the West?

As a journalist, I’ve come to think that a more revealing formulation of the difference of opinion about rising (or falling) prices is to be found in Joseph Schumpeter’s History of Economic Analysis (1954), where the economist distinguished between real and monetary analysis. Real analysis, Schumpeter wrote, is old as Aristotle. It “proceeds from the principle that all the essential phenomena of economic life are capable of being described in terms of goods and services, of decisions about them, and relations between them. Money enters the picture only in the modest role of a technical device that had been adopted in order to facilitate transactions,” and, occasionally, in the central role of what are described as “monetary disorders.”

Monetary analysis, Schumpeter continued, denies that money is of secondary importance in economic affairs., “We need only observe the course of events during and after the California gold discoveries to solidify ourselves that these discoveries were responsible for a great deal more than a change in the unit with which values are expressed,” he added, observing that money serves as a store of value as well as a means of transacting business.

Nor have we any difficulty in realizing – as A. Smith did – that the development of an efficient banking system may make a lot of difference in the development of a country’s wealth.

Schumpeter did not have an especially high opinion of Adam Smith!

As it happens, I wrote a book about all this forty years ago. As a magazine writer in New York, I had come across a 700-year index of the cost of living in a certain fashion in England. It showed two decades-long periods of steadily rising prices, one in the 16th Century, another in the 18th, both of which eventually leveled off, never returning to their prior levels. So I wrote in 1975 that the rising prices of the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s, too, would probably level off one day, though I didn’t venture why or when, much less mention Paul Volcker, the Federal Reserve Board chairman in 1979-1987.

My interest piqued, I spent a year in the New York Public Library unburdening myself of (some of) my ignorance, before turning back to the task of earning a living, this time as a newspaperman in Boston. By then I was more interested in the history of technology and government. Money and banking? Yawn! The Idea of Economic Complexity finally emerged in 1984, with nothing more to unify those ad hoc accounts of rising prices than the word complexity; intuitively appealing, perhaps, but analytically empty. It was a shaggy little book, in James Fallows’s apt description, politely received and quickly forgotten.

But before it was, Charles P. Kindleberger replied to a note I had written to say that I was entirely right that complexity does not communicate itself to economists, “at least not to this economist.” Kindleberger and I gradually became friends, and gradually I learned how little I understood how about the languages in which economist wrote for one another. Since then my knowledge of economics has increased to include, for example, the distinction between real and monetary analysis, and so has my admiration for what professional economist have achieved in the 250 years they have been doing business together. But then so have my doubts that economists have yet learned all there is to know about the understanding their science can produce. And, suddenly, primers on “inflation” are back in the news for the first time since in forty years.

So I plan to write a few pieces, half a dozen in all, one after another, about what I have learned about what I was trying to say forty years ago, anchoring each in a particular book or article that opened my eyes. I am not a true skeptic in the philosophers’ senses; don’t think that nobody knows anything: I think that economists know a lot. But I believe that they are still learning, that there are things that economists don’t yet know how to say, and that journalists can contribute to the conversation.

If you are looking for state-of-the-art knowledge, read Charles Goodhart. If you are interested in informed speculation, keep reading here. Better yet, do both. A lot of adventure lies ahead.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first appeared.

Liz Szabo: COVID's silver lining may be breakthroughs against other severe diseases

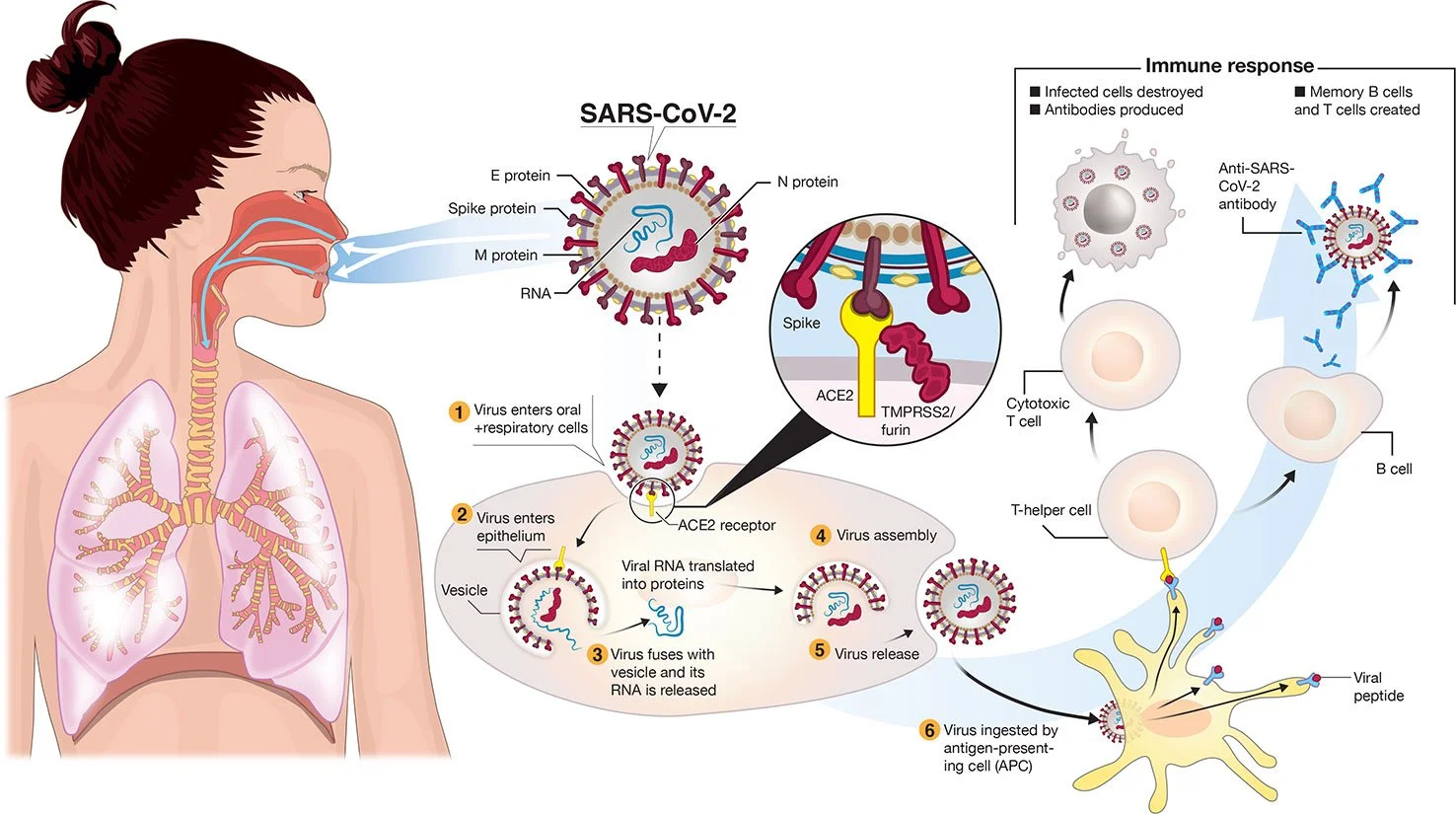

Transmission and life-cycle of SARS-CoV-2 causing COVID-19. 2/furin. A simplified depiction of the life cycle of the virus is shown along with potential immune responses elicited.

— Colin D. Funk, Craig Laferrière, and Ali Ardakani. Graphic by Ian Dennis - http://www.iandennisgraphics.com

“It’s not either/or. We’ve created this artificial dichotomy about how we think about these viruses. But we always put out a mixture of both” when we breathe, cough and sneeze.

— Dr. Michael Klompas, a professor at Harvard Medical School and infectious- disease doctor.

xxx

“There is a lot of frustration about being written off by the medical community, being told that it’s all in one’s head, that they just need to see a psychiatrist or go to the gym.’’

— Dr. David Systrom, a pulmonary and critical-care physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, in Boston.

The billions of dollars invested in COVID-19 vaccines and research so far are expected to yield medical and scientific dividends for decades, helping doctors battle influenza, cancer, cystic fibrosis and far more diseases.

“This is just the start,” said Dr. Judith James, vice president of clinical affairs for the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation. “We won’t see these dividends in their full glory for years.”

Building on the success of mRNA vaccines for covid, scientists hope to create mRNA-based vaccines against a host of pathogens, including influenza, Zika, rabies, HIV, and respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, which hospitalizes 3 million children under age 5 each year worldwide.

Researchers see promise in mRNA to treat cancer, cystic fibrosis and rare, inherited metabolic disorders, although potential therapies are still many years away.

Pfizer and Moderna worked on mRNA vaccines for cancer long before they developed covid shots. Researchers are now running dozens of clinical trials of therapeutic mRNA vaccines for pancreatic cancer, colorectal cancer, and melanoma, which frequently responds well to immunotherapy.

Companies looking to use mRNA to treat cystic fibrosis include ReCode Therapeutics, Arcturus Therapeutics, and Moderna and Vertex Pharmaceuticals, which are collaborating. The companies’ goal is to correct a fundamental defect in cystic fibrosis, a mutated protein.

Rather than replace the protein itself, scientists plan to deliver mRNA that would instruct the body to make the normal, healthy version of the protein, said David Lockhart, ReCode’s president and chief science officer.

None of these drugs is in clinical trials yet.

That leaves patients such as Nicholas Kelly waiting for better treatment options.

Kelly, 35, was diagnosed with cystic fibrosis as an infant and has never been healthy enough to work full time. He was recently hospitalized for 2½ months due to a lung infection, a common complication for the 30,000 Americans with the disease. Although novel medications have transformed the lives of most people with CF, they don’t work in 10% of patients. About one-third of patients who don’t benefit from the new medications are Black and/or Hispanic, said JP Clancy, vice president of clinical research for the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.

“Nobody wants to be hospitalized,” said Kelly, who lives in Cleveland. “If something could decrease my symptoms even 10%, I would try it.”

Predicting Which COVID Patients Are Most Likely to Die

Ambitious scientific endeavors have provided technological windfalls for consumers in the past; the race to land on the moon in the 1960s led to the development of CT scanners and MRI machines, freeze-dried food, wireless headphones, water purification systems, and the computer mouse.

Likewise, funding for AIDS research has benefited patients with a variety of diseases, said Dr. Carlos del Rio, a professor of infectious diseases at Emory University School of Medicine. Studies of HIV led to the development of better drugs for hepatitis C and cytomegalovirus, or CMV; paved the way for successful immunotherapies in cancer; and speeded the development of covid vaccines.

Over the past two years, medical researchers have generated more than 230,000 medical journal articles, documenting studies of vaccines, antivirals, and other drugs, as well as basic research into the structure of the virus and how it evades the immune system.

Dr. Michelle Monje, a professor of neurology at Stanford University, has found similarities in the cognitive side effects caused by COVID and a side effect of cancer therapy often called “chemo brain.” Learning more about the root causes of these memory problems, Monje said, could help scientists eventually find ways to prevent or treat them.

James hopes that computer technology used to detect COVID will improve the treatment of other diseases. For example, researchers have shown that cell-phone apps can help detect potential covid cases by monitoring patients’ self-reported symptoms. James said she wonders if the same technology could predict flare-ups of autoimmune diseases.

“We never dreamed we could have a PCR test that could be done anywhere but a lab,” James said. “Now we can do them at a patient’s bedside in rural Oklahoma. That could help us with rapid testing for other diseases.”

One of the most important pandemic breakthroughs was the discovery that 15 to 20 percent of patients over 70 who die of COVID have rogue antibodies that disable a key part of the immune system. Although antibodies normally protect us from infection, these “autoantibodies” attack a protein called interferon that acts as a first line of defense against viruses.

By disabling key immune fighters, autoantibodies against interferon allow the coronavirus to multiply wildly. The massive infection that results can lead the rest of the immune system to go into hyperdrive, causing a life-threatening “cytokine storm,” said Dr. Paul Bastard, a researcher at Rockefeller University.

The discovery of interferon-targeting antibodies “certainly changed my way of thinking at a broad level,” said E. John Wherry, director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Institute for Immunology, who was not involved in the studies. “This is a paradigm shift in immunology and in COVID.”

Antibodies that disable interferon may explain why a fraction of patients succumb to viral diseases, such as influenza, while most recover, said Dr. Gary Michelson, founder and co-chair of Michelson Philanthropies, a nonprofit that funds medical research and recently gave Bastard its inaugural award in immunology.

The discovery “goes far beyond the impact of COVID-19,” Michelson said. “These findings may have implications in treating patients with other infectious diseases” such as the flu.

Bastard and colleagues have also found that one-third of patients with dangerous reactions to yellow fever have autoantibodies against interferon.

International research teams are now looking for such autoantibodies in patients hospitalized by other viral infections, including chickenpox, influenza, measles, respiratory syncytial virus, and others.

Overturning Dogma

For decades, public health officials created policies based on the assumption that viruses spread in one of two ways: either through the air, like measles and tuberculosis, or through heavy, wet droplets that spray from our mouths and noses, then quickly fall to the ground, like influenza.

For the first 17 months of the covid pandemic, the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said the coronavirus spread through droplets and advised people to wash their hands, stand 6 feet apart, and wear face coverings. As the crisis wore on and evidence accumulated, researchers began to debate whether the coronavirus might also be airborne.

Today it’s clear that the coronavirus — and all respiratory viruses — spread through a combination of droplets and aerosols, said Dr. Michael Klompas, a professor at Harvard Medical School and infectious disease doctor.

“It’s not either/or,” Klompas said. “We’ve created this artificial dichotomy about how we think about these viruses. But we always put out a mixture of both” when we breathe, cough, and sneeze.

Knowing that respiratory viruses commonly spread through the air is important because it can help health agencies protect the public. For example, high-quality masks, such as N95 respirators, offer much better protection against airborne viruses than cloth masks or surgical masks. Improving ventilation, so that the air in a room is completely replaced at least four to six times an hour, is another important way to control airborne viruses.

Still, Klompas said, there’s no guarantee that the country will handle the next outbreak any better than this one. “Will we do a better job fighting influenza because of what we’ve learned?” Klompas said. “I hope so, but I’m not holding my breath.”

Fighting Chronic Disease

Lauren Nichols, 32, remembers exactly when she developed her first covid symptoms: March 10, 2020.

It was the beginning of an illness that has plagued her for nearly two years, with no end in sight. Although Nichols was healthy before developing what has become known as “long COVID,” she deals with dizziness, headaches, and debilitating fatigue, which gets markedly worse after exercise. She has had shingles — a painful rash caused by the reactivation of the chickenpox virus — four times since her covid infection.

Six months after testing positive for COVID, Nichols was diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome, also known as myalgic encephalomyelitis, or ME/CFS, which affects more than 1 million Americans and causes many of the same symptoms as COVID. There are few effective treatments for either condition.

In fact, research suggests that “the two conditions are one and the same,” said Dr. Avindra Nath, clinical director of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, part of the National Institutes of Health. The main difference is that people with long COVID know which virus caused their illness, while the precise virus behind most cases of chronic fatigue is unknown, Nath said.

Advocates of patients with long COVID want to ensure that future research — including $1.15 billion in targeted funding from the NIH — benefits all patients with chronic, post-viral diseases.

“Anything that shows promise in long covid will be immediately trialed in ME/CFS,” said Jarred Younger, director of the Neuroinflammation, Pain and Fatigue Laboratory at the University of Alabama-Birmingham.

Patients with chronic fatigue syndrome have felt a kinship with long COVID patients, and vice versa, not just because they experience the same baffling symptoms, but also because both have struggled to obtain compassionate, appropriate care, said Nichols, vice president of Body Politic, an advocacy group for people with long COVID and other chronic or disabling conditions.

“There is a lot of frustration about being written off by the medical community, being told that it’s all in one’s head, that they just need to see a psychiatrist or go to the gym,” said Dr. David Systrom, a pulmonary and critical care physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

That sort of ignorance seems to be declining, largely because of increasing awareness about long COVID, said Emily Taylor, vice president of advocacy and engagement at Solve M.E., an advocacy group for people with post-infectious chronic illnesses. Although some doctors still refuse to believe long covid is a real disease, “they’re being drowned out by the patient voices,” Taylor said.

A new study from the National Institutes of Health, called RECOVER (Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery), is enrolling 15,000 people with long covid and a comparison group of nearly 3,000 others who haven’t had covid.

“In a very dark cloud,” Nichols said, “a silver lining coming out of long covid is that we’ve been forced to acknowledge how real and serious these conditions are.”

Liz Szabo is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

A place to be free

“We learned the shocking truth that ‘home’ isn’t necessarily a certain spot on earth. It must be a place where you can ‘feel’ at home, which means ‘free’ to us.’’

— Maria Augusta von Trapp, in The Story of the Trapp Family Singers (made famous by The Sound of Music). In 1938 the family fled the Nazis, who had taken over Austria, and eventually settled in Stowe, Vt.

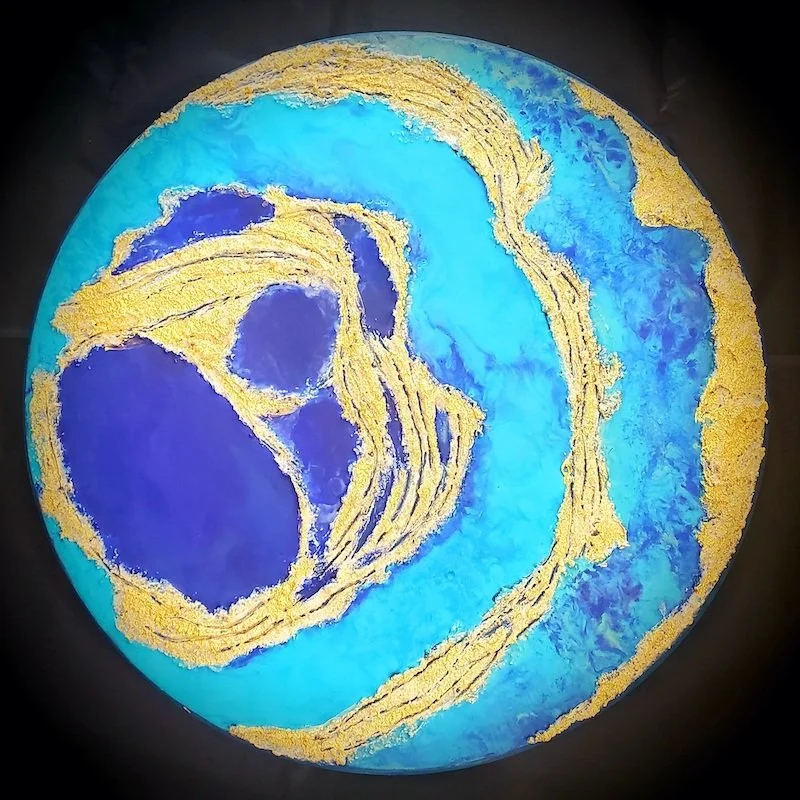

The earth in a few years?

“Blue Marble Orb” (15 inches round, encaustic, mixed media on milled pine), by Ashland, Mass.-based artist Pamela Dorris DeJong.

She says:

“After painting land and waterscapes for many years I realized that I could put forth healing energy towards the earth and our oceans. Healing can occur through painting, meditation, education, sharing the message through the image itself, and explanation of the intent.’’

Built in 1832 as an inn (now it’s just a restaurant) by Captain John Stone, to capitalize on the new Boston and Worcester Railroad, The Railroad House, later renamed John Stone's Inn, and now known as Stone's Public House, is in the center of Ashland.

Stone's is said to be haunted by various ghosts. The story of one of them: Captain Stone is said to have accidentally killed a New York salesman named Mike McPherson when he hit him on the head with a pistol when he suspected McPherson of cheating at poker. Stone and three friends with whom he had been playing allegedly swore to keep the killing secret and buried the salesman's body in the inn's basement. The legend contends that the ghosts of the salesman and the three other players involved all roam the inn. But no body has ever been found.

Maine: ‘Almost hallucinatory’

Blue Hill, Maine, from Parker Point.

“I think of those first five years in Maine as the time when this happened to me…. I was suddenly seeing, feeling, and listening as a child sees, feels, and listens.’’

– E.B. White (1899-1985), American writer

xxx

“Should fate unkind

send us to roam,

The scent of the fragrant pines,

the tang of the salty sea

Will call us home.’’

— From “State of Maine,’’ the state’s official song

xxx

“The beauty of Maine is such that you can’t really see it clearly while you live there. But now that I’ve moved away, with each return it all becomes almost hallucinatory: the dark blue water, the rocky coast with occasional flashes of white sand, the jasper stone beaches along the coast, the fire and fir forests somehow vivid in their stillness.”

— Alexander Chee ( born 1967) novelist

Chris Powell: With the right pressure would some pols support cannibalism?

A cannibal feast on Tanna, Vanuatu, circa 1885–1889

Painting by Charles E. Gordon Frazer (1863-1899)

MANCHESTER, Conn.,

For many years the case for raising the pay of Connecticut state legislators has been solid in principle.

Their base annual salary is $28,000. Representatives get another $4,500 and senators $5,500 annually for expenses they don't have to document. There is a mileage allowance. Legislators may get a few thousand dollars more if they are appointed to "leadership" positions, and, predictably enough, while most leadership positions are only nominal, they are so numerous that many legislators get one.

But the average legislator is being paid only $35,000 per year and legislators have gotten no raise since 2001, even as inflation is high.

While legislative sessions seldom last more than six months, those sessions often run from morning to late at night. Quite apart from their work at the Capitol, legislators typically are on duty most of the year dealing with constituents and interest groups. Many legislators attend civic events when they're not on the telephone hearing pleas for help, favors, or patronage.

As a result, being a state legislator is not a practical option for most people, as it offers part-time pay for what is often more than full-time work even as it requires most to hold other jobs to support themselves and their families.

In the old days the Hartford insurance companies and major law firms would give legislative leaders jobs with highly flexible schedules, even "no-show" jobs, though that practice diminished as the conflict of interest was recognized. But still, if legislators are not wealthy or financially comfortable in retirement, they need second jobs with flexible hours. For most, legislative office really is public service, no matter how well or poorly they perform.

So as a practical matter service in the General Assembly is not really open to everyone. Lawyers, financial company employees, and retirees are disproportionately represented in it. Factory workers, truckers, nurses and barbers aren't.

Theoretically, higher and effectively full-time legislative salaries would be more democratic and draw more capable and qualified people to the General Assembly. Legislators often offer such reflections upon their retirement.

But few legislators planning to seek re-election take that position, at least not in public, since they assume that voters would hold it against them and could not be persuaded by any argument in favor of raises.

Indeed, many voters probably would not even understand that the state Constitution prevents legislators from voting to raise their own salaries -- that legislators can't get a raise unless voters re-elect them to it.

But legislative pay raises aren't the only issue that fails to be addressed because of a lack of political courage. State government seldom addresses any issue with courage.

For many years state government has been mainly an exercise in distributing money to the loudest and most numerous bleaters, even as Connecticut's biggest problems -- generational poverty, educational failure, racial segregation, housing prices, criminal justice and such -- have not been alleviated, government's only response to them being to do and spend more on what doesn't work, as long as what doesn't work employs people who will support the regime at election time.

A legislator who merely acknowledged that state government's expensive policies toward those enduring problems don't work might be more courageous than all his colleagues.

Of course , Connecticut isn't peculiar in this respect, just maybe worse because its prosperity has insulated it somewhat from failure. A century ago the writer H.L. Mencken saw the tendency everywhere in government.

“Laws," Mencken wrote, "are no longer made by a rational process of public discussion. They are made by a process of blackmail and intimidation, and they are executed in the same manner. The typical lawmaker of today is a man wholly devoid of principle -- a mere counter in a grotesque and knavish game. If the right pressure could be applied to him, he would be cheerfully in favor of polygamy, astrology, or cannibalism.”

That's why better pay for state legislators might not change anything. For legislators don't elect themselves. Their constituents usually elect and re-elect them without ever noticing their policy failures. To get a better public life you need to get a better public.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Compressed loves and hates

The Blackinton section of North Adams, Mass., in 1889.

In Natural Bridge State Park, a Massachusetts state park in North Adams. Named for its natural bridge of white marble, unique in North America, the park also offers woodland walks with views of a dam made of white marble, and a picturesque old marble quarry.

“The village viewed from the top of the hill to the westward, at sunset, has a peculiarly happy and peaceful look; it lies on a level, surrounded by hills, and seems as if it lay in the hollow of a large hand….It is amusing to see all the distributed property, the aristocracy and commonality, the various and conflicting interests of the town, the loves and hates, compressed into a space which the eye takes in as completely as the arrangement of a tea-table.

Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-1864), on North Adams, Mass., in The American Notebooks (1838). North Adams, in The Berkshires, would become a thriving factory town. Manufacturing started to leave decades ago, and North Adams is now an arts center, particularly because of the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art.

Art auction benefits Ukrainian relief efforts

Creative Connections Gift Shop and Gallery, in Ashburnham, Mass., and Russian artist Alexey Naumovich Neyman are hosting a silent auction coinciding with the exhibit "The Habitual Light of Memory" running through April 30. All proceeds from the purchase of art from the exhibit will be donated to the International Rescue Committee's Ukrainian relief efforts.

At the top of Mount Watatic, in Ashburnham, a 1,832-foot-high monadnock just south of the Massachusetts–New Hampshire border, at the southern end of the Wapack Range. The 22-mile Wapack Trail and the 92-mile Midstate Trail both cross the mountain.

Celebrating in the ‘sugar bush’

Molten syrup poured on clean white snow to create a kind of soft maple candy.

“Then ‘sugaring off’ was a gala time, with parties in the ‘sugar bush,’ where dippers of syrup were poured into the snow to harden for the guests….Sweet, sour pickles were often served to whip up jaded appetites. They ate sugar between the buttered layers of pancakes four tiers thick; and songs were sung and jokes were cracked and even the most dour old farmer became genial at the thought that the long cold mountain winter was over and spring would soon be there.’’

-- Ernest Pole on the maple-syrup harvest after in 1938 hurricane (which blew down many, many trees) in his book The Great White Hills of New Hampshire (1946)

A "sugar shack" where sap is boiling.

Pouring the sap.

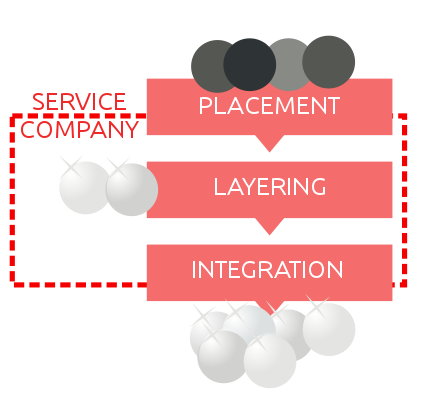

Chuck Collins: Cracking down on Russian oligarchs should include closing U.S. tax havens

Placing "dirty" money in a service company, where it is layered with legitimate income and then integrated into the flow of money, is a common form of money laundering.

Via OtherWords.org

BOSTON

As part of the sanctions against Russia for its invasion of Ukraine, the United States and its European partners are cracking down on Russian oligarchs. They’re freezing assets and tracking the yachts, private jets and luxury real estate holdings of these Russian billionaires.

“I say to the Russian oligarchs and the corrupt leaders who bilked billions of dollars off this violent regime: no more,” Biden said in his State of the Union address. “We are coming for your ill-begotten gains.”

Targeting Russia’s elites, who have stolen trillions from their own people, is an important strategy to pressure Russian President Vladimir Putin, who himself may be among the wealthiest people on the planet.

But the U.S. faces a major obstacle in this effort: Our own country has become a major destination tax haven for criminal and oligarch wealth from around the world — and not just Russians.

While European Union countries have been increasing transparency and cracking down on kleptocratic capital, the United States is a laggard. As the Pandora Papers disclosed last year, the U.S. has become a weak link in the fight against global corruption.

Delaware, the state President Biden represented in the Senate for 36 years, is the premiere venue for anonymous limited-liability companies that don’t have to disclose who their real beneficial owners are, even to law enforcement. And South Dakota is the home for billionaires creating dynasty trusts, where they can park wealth outside the reach of tax authorities for generations.

Even U.S. charities, as my colleague Helen Flannery wrote recently, have received billions from Russian oligarchs, helping to sanitize their reputations.

Global wealth continues to flood into the United States, especially in luxury real estate. In February, the New York Post did an expose on the luxury real estate holdings of Russian oligarchs in the Big Apple. But oligarchs hide their wealth in real estate all over the country, as well as art, cryptocurrency, and jewelry.

This vast wealth-hiding apparatus would not exist without an enormous enabling class of lawyers, accountants and wealth managers. These “wealth defense industry” professionals are the agents of inequality, the facilitators of the wealth disappearing act. This class of professionals uses their considerable political clout to block reforms.

The first step in fixing the hidden wealth system is ownership transparency — requiring the disclosure of beneficial ownership in real estate, trusts, and companies and corporations. Cities such as Los Angeles are exploring municipal-level disclosure of real estate ownership so they can know who’s buying their neighborhoods.

But we should also shine a spotlight on the wealth defense industry. Days after the release of the Pandora Papers, U.S. lawmakers introduced the ENABLERS Act, which would require such attorneys, wealth managers, real estate professionals, and art dealers to report suspicious activity. The attention on Russian oligarchs has revived interest in this legislation.

If the U.S. wants to clamp down on Russian oligarchs, the first step is to get our own house in order

Chuck Collins, based in Boston, directs the Program on Inequality at the Institute for Policy Studies. He’s the author of The Wealth Hoarders: How Billionaires Pay Millions to Hide Trillions.

Magical wetland

“Sunset on the Marshes” (on the Massachusetts North Shore) (1867) (oil on canvas), by Martin Johnson Heade (1819-1904), at the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass.

— Photography by Bob Packert

Llewellyn King: Helping America by helping Ukrainian refugees resettle in U.S. counties that could use more people

Wheat field in Idaho. Ukraine, like the U.S., is a very big wheat producer.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The Ukrainian diaspora is upon the world. Of the millions who are dispossessed by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it is wishful thinking that on some glorious day they will all go home. In reality, the world will have to accommodate them. They can’t all stay in Poland and Romania.

One by one, the countries of Europe falteringly are stepping up to their moral and humanitarian duty. Most countries say they will take some Ukrainian refugees.

The Biden administration, without clarity, has indicated that some refugees will be welcomed. What the administration is hoping is that these will be glommed onto existing Ukrainian communities in several cities.

This might be a mistake. The cities with large Ukrainian communities are New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Detroit, Cleveland and Indianapolis. In all these cities, housing is expensive and in very short supply; and there are many social problems for those at the bottom, where refugees traditionally find themselves.

Now comes an extraordinary proposal for refugee resettlement from an attorney, Christopher Smith, who practices in Macon, Ga. He is also the honorary consul there for Denmark, but he tells me his proposal is in no way a reflection of that office and is entirely his own as a private citizen.

Smith’s sweeping and enticing proposal is that refugees from Ukraine should be settled, with federal and state assistance and with the participation of local government, not in crowded cities but in American counties which have been losing population for decades. “Those include counties here in south Georgia,” Smith told me by telephone.

You may think, from anecdotal reporting, that there is a major move from cities to the country, spurred by COVID. But Smith tells me that movement is small and doesn’t reverse the decades-long trend of county depopulation.

My own observation of this COVID-induced trend is that it applies to such places as New York and Boston, where the outward movement has been to garden locales where virtual commuting can be accomplished, for example, people who have moved from Boston and New York to Rhode Island and Connecticut, and from Los Angeles to smaller outposts, or north to Washington and Oregon.

Smith said in a position paper: “There are 3,143 counties in the United States. From 2010 to 2020, approximately 1,660 (53 percent) of American counties lost population. Here in Georgia, 67 (42 percent) of 159 counties saw a reduction in population during that time span. Most but not all American counties that lost population during this 10-year period are located in rural areas.”

While counties tend to have a higher apartment and rental home vacancy rate and a lower cost of living than the national average, many of these communities have job shortages, Smith said.

“Logic would suggest that these communities would be an ideal location to host Ukrainian refugees,” he said.

The thing that struck me about Smith’s proposal is how thoroughly he has researched it. He hasn’t just sprouted an idea, he has worked out a plan and enshrined it in a draft act of Congress, which lays out the federal, state and county responsibilities and the issuance of work permits and residence certificates -- and, of course, the all-important issue of funding. He has sent it to his congressman, Austin Scott, a Republican.

Smith told me that it is worth noting that Scandinavians were encouraged to populate the Midwest -- as anyone who listened to Prairie Home Companion, on NPR knows.

I don’t know whether America’s wheat farmers need help, but certainly there will be pressure to grow more wheat. The chances that wheat will be sown in the middle of Russia’s war on Ukraine are unlikely. Ukraine is a huge wheat producer. Canada brought in Ukrainian immigrants in the 1890s to help boost wheat production. It was a great success.

It seems to me that Smith’s well-conceived proposal has merit and deserves attention. It has the prima facie merit of helping a part of America that needs help, and giving succor to the most desperate of people, those uprooted by war.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

--

Co-host and Producer

"White

New-museum magic

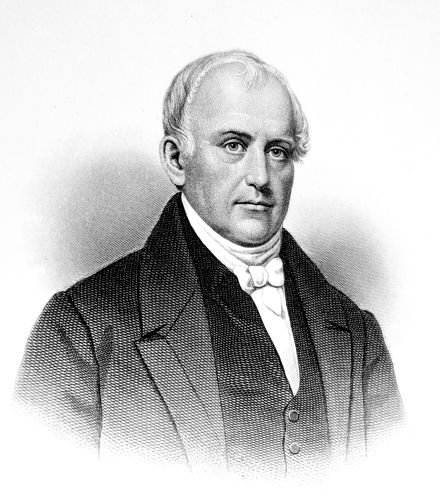

Samuel Slater

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

All hail the Samuel Slater Experience, an interactive museum in Webster, Mass., that spotlights the work of Samuel Slater (1768-1835), the English immigrant whose work in setting up manufacturing mills was a major element in the launch of the American Industrial Revolution. It also displays much of the history of Webster, an important early mill town. Slater may be best known for Slater Mill, on the Blackstone River in Pawtucket, but he set up other mills, too, most notably in Webster, where he lived from 1812 and from which he ran his empire. (He also loved using child labor….)

It's a reminder of the tremendous dynamism and economic and technological creativity of New Englanders, right up to the present. This has helped keep the region one of the most prosperous places in the world.

One example seems particularly germane now as America tries to move away from our perilous reliance on global-warming fossil fuels sold by such vicious regimes as Russia and Saudi Arabia that we have funded far too long.

Commonwealth Fusion Systems, based in Cambridge and Dever, Mass., is making progress in developing a safe form of nuclear energy that could ultimately replace all gas, oil, and coal now used to generate electricity, as well as the controlled fission nuclear plants that present spent-fuel-storage challenges.

Hit these links:

Then, there’s Cambridge-based Moderna, developer of what might well be the best COVID-19 vaccine.

xxx

In other happy news, the stunning new Sailing Museum, in Newport, will open in May, in time for the City by the Sea’s main tourist season. It’s hard to think of a better place than Newport for such a museum. It’s not only associated with major local and international sailing races, from America’s Cup on, but with the full range of small-scale recreational sailing.

But there’s more! Construction is supposed to begin this summer on the National Coast Guard Museum, on the waterfront in New London, home of the Coast Guard Academy.