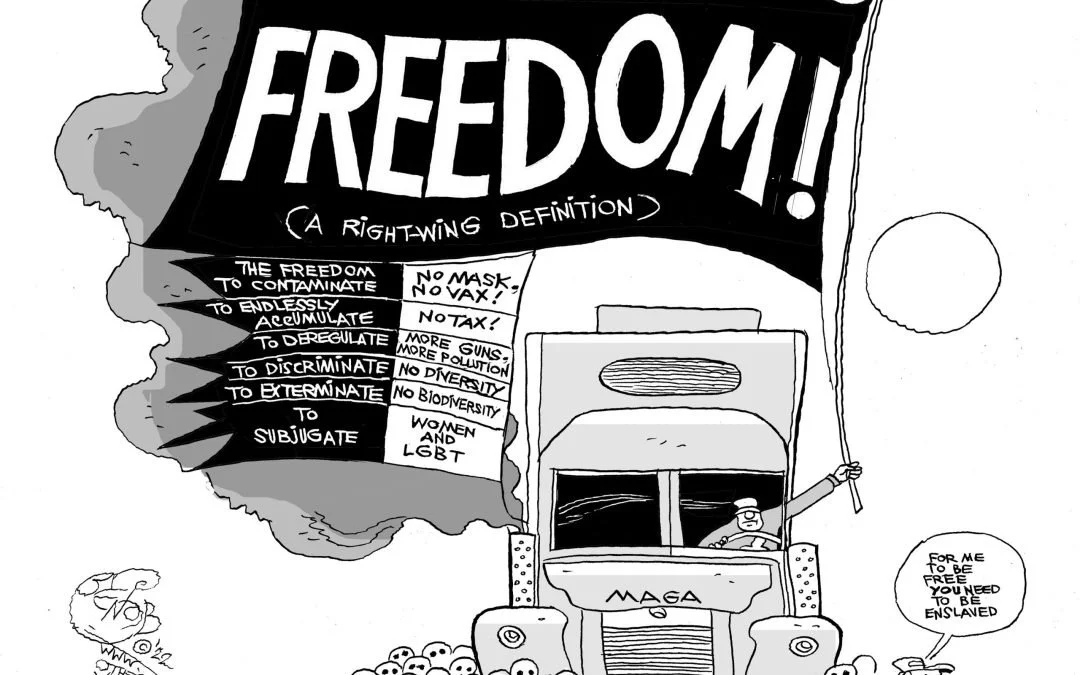

Malaise of elderly grows as pandemic grinds on

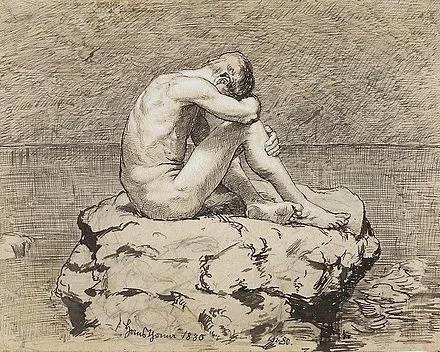

“Loneliness,’’ by Hans Thoma, in the National Museum in Warsaw.

“Folks are becoming more anxious and angry and stressed and agitated because this has gone on for so long.’’

— Katherine Cook, chief operating officer of Monadnock Family Services in Keene, N.H., which operates a community mental-health center that serves older adults.

Late one night in January, Jonathan Coffino, 78, turned to his wife as they sat in bed. “I don’t know how much longer I can do this,” he said, glumly.

Navigating Aging focuses on medical issues and advice associated with aging and end-of-life care, helping America’s 45 million seniors and their families navigate the health care system

Coffino was referring to the caution that’s come to define his life during the COVID-19 pandemic. After two years of mostly staying at home and avoiding people, his patience is frayed and his distress is growing.

“There’s a terrible fear that I’ll never get back my normal life,” Coffino told me, describing feelings he tries to keep at bay. “And there’s an awful sense of purposelessness.”

Despite recent signals that COVID’s grip on the country may be easing, many older adults are struggling with persistent malaise, heightened by the spread of the highly contagious omicron variant. Even those who adapted well initially are saying their fortitude is waning or wearing thin.

Like younger people, they’re beset by uncertainty about what the future may bring. But added to that is an especially painful feeling that opportunities that will never come again are being squandered, time is running out, and death is drawing ever nearer.

“I’ve never seen so many people who say they’re hopeless and have nothing to look forward to,” said Henry Kimmel, a clinical psychologist in Sherman Oaks, California, who focuses on older adults.

To be sure, older adults have cause for concern. Throughout the pandemic, they’ve been at much higher risk of becoming seriously ill and dying than other age groups. Even seniors who are fully vaccinated and boosted remain vulnerable: More than two-thirds of vaccinated people hospitalized from June through September with breakthrough infections were 65 or older.

The constant stress of wondering “Am I going to be OK?” and “What’s the future going to look like?” has been hard for Kathleen Tate, 74, a retired nurse in Mount Vernon, Wash. She has late-onset post-polio syndrome and severe osteoarthritis.

“I guess I had the expectation that once we were vaccinated the world would open up again,” said Tate, who lives alone. Although that happened for a while last summer, she largely stopped going out as first the delta and then the omicron variants swept through her area. Now, she said she feels “a quiet desperation.”

This isn’t something that Tate talks about with friends, though she’s hungry for human connection. “I see everybody dealing with extraordinary stresses in their lives, and I don’t want to add to that by complaining or asking to be comforted,” she said.

Tate described a feeling of “flatness” and “being worn out” that saps her motivation. “It’s almost too much effort to reach out to people and try to pull myself out of that place,” she said, admitting she’s watching too much TV and drinking too much alcohol. “It’s just like I want to mellow out and go numb, instead of bucking up and trying to pull myself together.”

Beth Spencer, 73, a recently retired social worker who lives in Ann Arbor, Mich., with her 90-year-old husband, is grappling with similar feelings during this typically challenging Midwestern winter. “The weather here is gray, the sky is gray, and my psyche is gray,” she told me. “I typically am an upbeat person, but I’m struggling to stay motivated.”

“I can’t sort out whether what I’m going through is due to retirement or caregiver stress or covid,” Spencer said, explaining that her husband was recently diagnosed with congestive heart failure. “I find myself asking ‘What’s the meaning of my life right now?’ and I don’t have an answer.”

Bonnie Olsen, a clinical psychologist at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine, works extensively with older adults. “At the beginning of the pandemic, many older adults hunkered down and used a lifetime of coping skills to get through this,” she said. “Now, as people face this current surge, it’s as if their well of emotional reserves is being depleted.”

Most at risk are older adults who are isolated and frail, who were vulnerable to depression and anxiety even before the pandemic, or who have suffered serious losses and acute grief. Watch for signs that they are withdrawing from social contact or shutting down emotionally, Olsen said. “When people start to avoid being in touch, then I become more worried,” she said.

Fred Axelrod, 66, of Los Angeles, who’s disabled by ankylosing spondylitis, a serious form of arthritis, lost three close friends during the pandemic: Two died of cancer and one of complications related to diabetes. “You can’t go out and replace friends like that at my age,” he told me.

Now, the only person Axelrod talks to on a regular basis is Kimmel, his therapist. “I don’t do anything. There’s nothing to do, nowhere to go,” he complained. “There’s a lot of times I feel I’m just letting the clock run out. You start thinking, ‘How much more time do I have left?’”

“Older adults are thinking about mortality more than ever and asking, ‘How will we ever get out of this nightmare,’” Kimmel said. “I tell them we all have to stay in the present moment and do our best to keep ourselves occupied and connect with other people.”

Loss has also been a defining feature of the pandemic for Bud Carraway, 79, of Midvale, Utah, whose wife, Virginia, died a year ago. She was a stroke survivor who had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and atrial fibrillation, an abnormal heartbeat. The couple, who met in the Marines, had been married 55 years.

“I became depressed. Anxiety kept me awake at night. I couldn’t turn my mind off,” Carraway told me. Those feelings and a sense of being trapped throughout the pandemic “brought me pretty far down,” he said.

Help came from an eight-week grief support program offered online through the University of Utah. One of the assignments was to come up with a list of strategies for cultivating well-being, which Carraway keeps on his front door. Among the items listed: “Walk the mall. Eat with friends. Do some volunteer work. Join a bowling league. Go to a movie. Check out senior centers.”

“I’d circle them as I accomplished each one of them. I knew I had to get up and get out and live again,” Carraway said. “This program, it just made a world of difference.”

Kathie Supiano, an associate professor at the University of Utah College of Nursing who oversees the COVID grief groups, said older adults’ ability to bounce back from setbacks shouldn’t be discounted. “This isn’t their first rodeo. Many people remember polio and the AIDS epidemic. They’ve been through a lot and know how to put things in perspective.”

Alissa Ballot, 66, realized recently she can trust herself to find a way forward. After becoming extremely isolated early in the pandemic, Ballot moved last November from Chicago to New York City. There, she found a community of new friends online at Central Synagogue in Manhattan and her loneliness evaporated as she began attending events in person.

With Omicron’s rise in December, Ballot briefly became fearful that she’d end up alone again. But, this time, something clicked as she pondered some of her rabbi’s spiritual teachings.

“I felt paused on a precipice looking into the unknown and suddenly I thought, ‘So, we don’t know what’s going to happen next, stop worrying.’ And I relaxed. Now I’m like, this is a blip, and I’ll get through it.”

Judith Graham is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

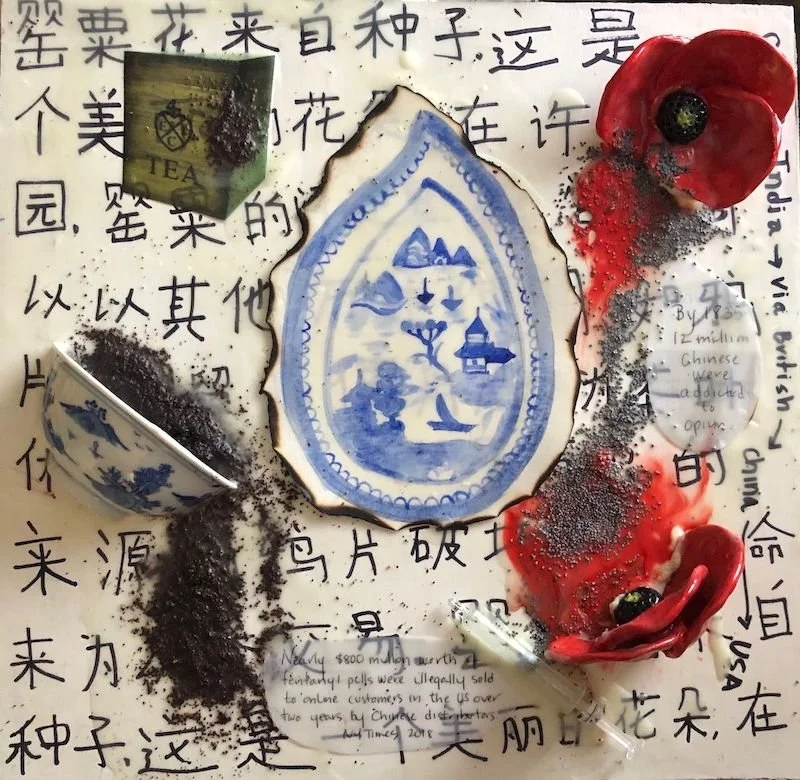

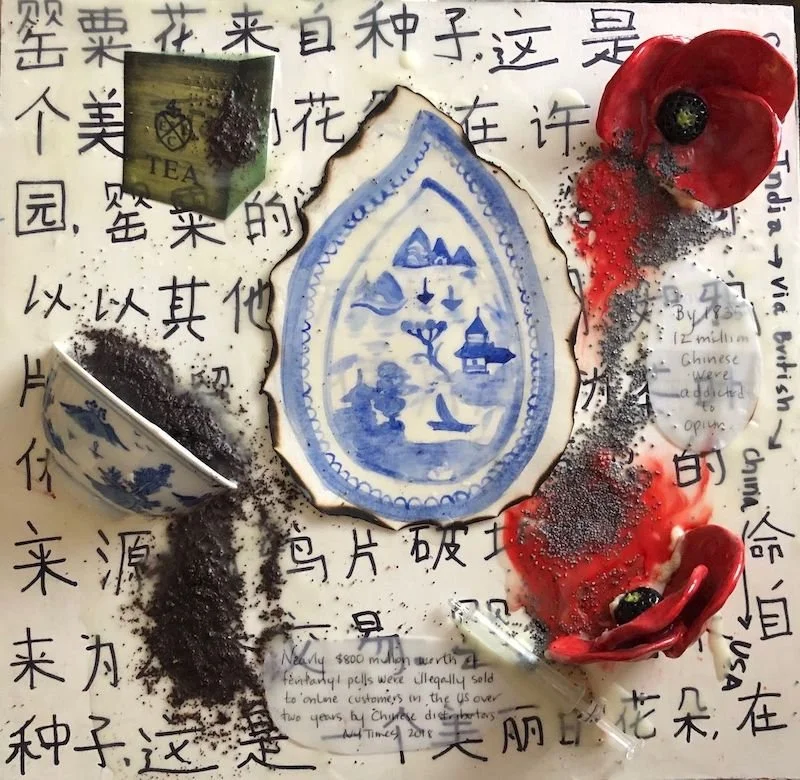

Beauty from New England’s drugged-up China Trade

“China Trade: Opium through the Ages” (encaustic, ceramic made and found objects, tea leaves, poppy seeds on panel), by Cambridge,Mass.-based artist Katrina Abbott.

New England’s “China Trade,’’ in the late 18th Century and the first half of the 19th, created great wealth for some in the region, mostly in and around its ports. Some of the trade involved selling opium to the Chinese. Much of that wealth was invested in what became very lucrative industries, such as textile, shoe and machinery manufacturing and railroads.

In her Web site, Ms. Abbott describes herself thusly:

“Katrina Abbott came to art later in life after her twins were born. Previous to this, she spent 25 years in education, including outdoor education, ocean education at sea and urban public school reform. With a BA in Environmental Biology and a Masters in Botany (studying seaweed!), she reflects her interest in and concern for the natural world in her art. She represents the nature in print, paint, wax ( encaustic) and mosaic. She is a member of the Cambridge Art Association and New England Wax and lives in Cambridge with her husband, their 20 year old boy/girl twins and small brown rabbit named Jarvis.’’

Derby House, in Salem, Mass. Elias Hasket Derby was among the wealthiest and most celebrated of post-Revolutionary War merchants in Salem. He was owner of the Grand Turk, said to be the first New England vessel to be used to trade directly with China. There were many mansions built by merchants in the China Trade, some of which was a drug trade.

—Photo by Daderot

And go away February

In March: A "sugar shack" where maple sap is boiling.

Maple-sap collecting.

Dear March—Come in—

How glad I am—

I hoped for you before—

Put down your Hat—

You must have walked—

How out of Breath you are—

Dear March, how are you, and the Rest—

Did you leave Nature well—

Oh March, Come right upstairs with me—

I have so much to tell—

I got your Letter, and the Birds—

The Maples never knew that you were coming—

I declare - how Red their Faces grew—

But March, forgive me—

And all those Hills you left for me to Hue—

There was no Purple suitable—

You took it all with you—

Who knocks? That April—

Lock the Door—

I will not be pursued—

He stayed away a Year to call

When I am occupied—

But trifles look so trivial

As soon as you have come

That blame is just as dear as Praise

And Praise as mere as Blame—

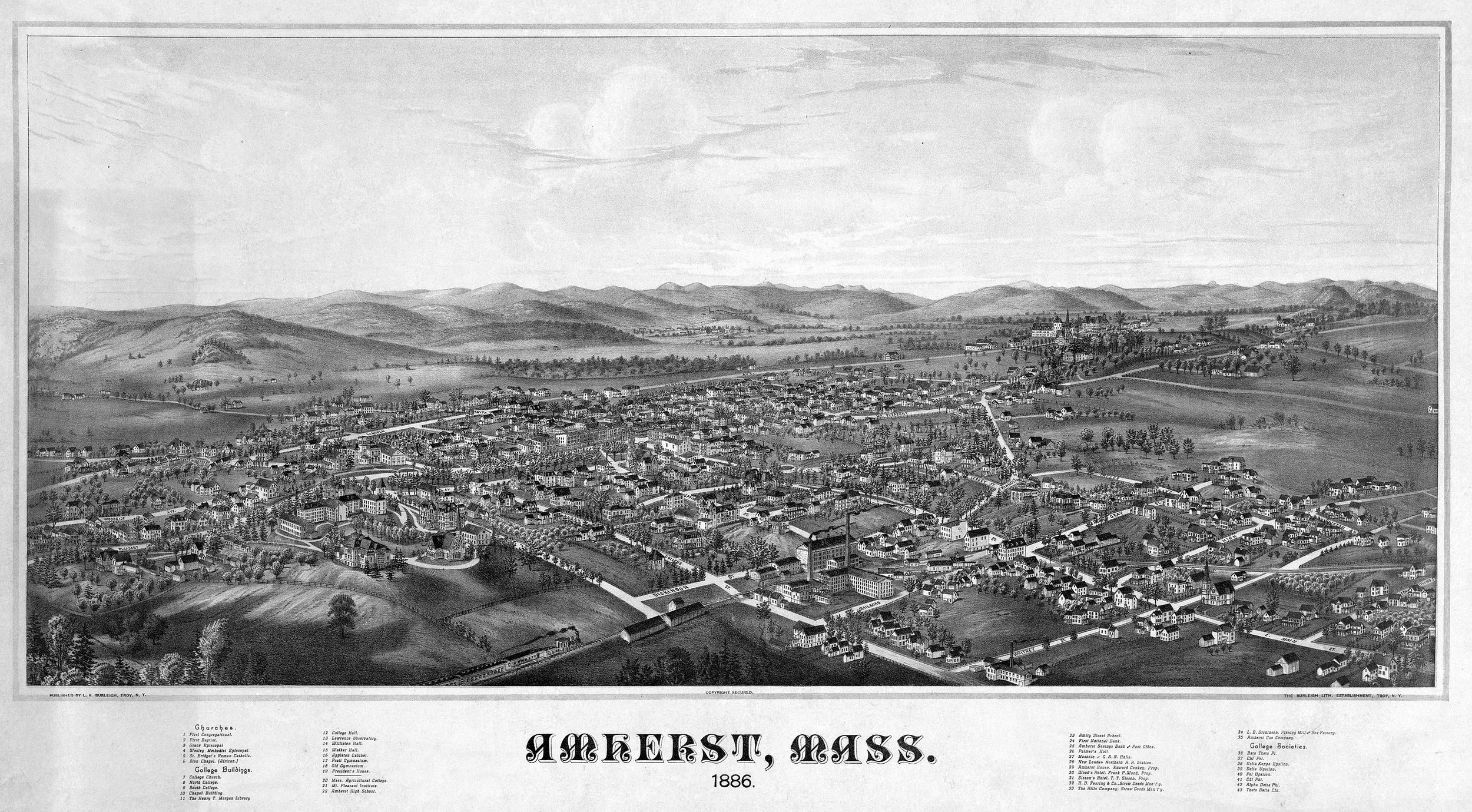

—Emily Dickinson (1830-1886), a lifelong resident of Amherst, Mass.

Don Pesci: May we be worthy of the brave Ukrainians

Albert Camus

VERNON, Conn.

In March, 1957, the French novelist and philosopher Albert Camus (1913-1960) published an essay, at great cost to himself, titled “{Janos} Kadar Had His Day Of Fear.” His epitaph on the Soviet-suppressed Hungarian Revolution, in the fall of 1956, may serve as well as an epitaph on the Ukraine’s democratic revolution, which Russian dictator Vladimir Putin is now trying to destroy. Kadar (1912-1989) was the Communist boss of Hungary, reporting to his Soviet bosses.

The Hungarian Revolution was suppressed at the order of the Kremlin, run by its then boss, Nikita Khrushchev, after Stalin had installed in Hungary a Communist dictatorship after World War II. Camus regarded the takeover of Hungary by totalitarian Stalinists as a counter-revolution.

His essay was costly to Camus for a number of reasons. It was an epistle of liberty and a resolute, unambiguous disparagement of totalitarianism.

The essay began on a defiant note: “The Hungarian Minister of State Marosan, whose name sounds like a program, declared a few days ago that there would be no further counter-revolution in Hungary. For once, one of Kadar's Ministers has told the truth. How could there be a counter-revolution since it has already seized power? There can be no other revolution in Hungary.”

And the second paragraph likely was considered in France by what we might call its philosophical establishment as an awakening slap in the face: “I am not one of those who long for the Hungarian people to take up arms again in an uprising doomed to be crushed under the eyes of an international society that will spare neither applause nor virtuous tears before returning to their slippers like football enthusiasts on Saturday evening after a big game. There are already too many dead in the stadium, and we can be generous only with our own blood. Hungarian blood has proved to be so valuable to Europe and to freedom that we must try to spare every drop of it.”

And then France’s apostle of liberty let loose the following thunderbolt: “But I am not one to think there can be even a resigned or provisional compromise with a reign of terror that has as much right to be called socialist as the executioners of the Inquisition had to be called Christians. And, on this anniversary of liberty, I hope with all my strength that the mute resistance of the Hungarian people will continue, grow stronger, and, echoed by all the voices we can give it, get unanimous international opinion to boycott its oppressors. And if that opinion is too flabby or selfish to do justice to a martyred people, if our voices also are too weak, I hope that the Hungarian resistance will continue until the counter-revolutionary state collapses everywhere in the East under the weight of its lies and its contradictions.”

Camus himself was both an atheist and a socialist fully prepared to take to the ramparts, in fine French fashion: “For it [the Stalinist false front] is indeed a counter-revolutionary state. What else can we call a regime that forces the father to inform on his son, the son to demand the supreme punishment for his father, the wife to bear witness against her husband —that has raised denunciation to the level of a virtue? Foreign tanks, police, twenty-year-old girls hanged, committees of workers decapitated and gagged, scaffolds, writers deported and imprisoned, the lying press, camps, censorship, judges arrested, criminals legislating, and the scaffold again—is this socialism, the great celebration of liberty and justice?”

Here at last was a man who knew how to draw proper distinctions. The essay was bound to tread on tender toes.

In Hungary, a Joshua horn had been sounded, and walls had begun to tumble: “Thus, with the first shout of insurrection in free Budapest, learned and shortsighted philosophies, miles of false reasonings and deceptively beautiful doctrines were scattered like dust. And the truth, the naked truth, so long outraged, burst upon the eyes of the world.

“Contemptuous teachers, unaware that they were thereby insulting the working classes, had assured us that the masses could readily get along without liberty if only they were given bread. And the masses themselves suddenly replied that they didn't have bread but that, even if they did, they would still like something else. For it was not a learned professor but a Budapest blacksmith who wrote: ‘I want to be considered an adult eager to think and capable of thought. I want to be able to express my thoughts without having anything to fear and I want, also, to be listened to.’"

It was an essay too far for many stern socialists in France, some of whom were prepared to avert their eyes so long as the Soviet experiment in Russia moved forward unimpeded.

Camus stood in the way of totalitarian progress. He was of the party of liberty and just revolt. As such, he ended his essay: “Our faith is that throughout the world, beside the impulse toward coercion and death that is darkening history, there is a growing impulse toward persuasion and life, a vast emancipatory movement called culture that is made up both of free creation and of free work.

“Our daily task, our long vocation is to add to that culture by our labors and not to subtract, even temporarily, anything from it. But our proudest duty is to defend personally to the very end, against the impulse toward coercion and death, the freedom of that culture—in other words, the freedom of work and of creation.

“The Hungarian workers and intellectuals, beside whom we stand today with so much impotent grief, realized that and made us realize it. This is why, if their suffering is ours, their hope belongs to us too. Despite their destitution, their exile, their chains, it took them but a single day to transmit to us the royal legacy of liberty. May we be worthy of it!”

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

‘A spoon and a rolling pin’

“Aunt Fanny’s headstone in the roadside graveyard is moss-stained … but her reputation as queen of the kitchen still lingers in the village of Franconia, {N.H.} for she was one of those natural cooks who are ‘born with a mixing spoon in one hand and a rolling pin in the other.’ New England has produced many. They invented baked Indian pudding and apple pandowdy. They established the boiled dinner as a Thursday institution, and Boston baked beans and brown bread as the typical Saturday night supper.’’

-- Ellen Shannon Bowles and Dorothy S. Towle, in Secrets of New England Cooking (1947)

State-owned Cannon Mountain, a large and old (founded in the ‘30s) ski area, rising over Franconia village in 2007. The building was the home of Dow Academy, founded in 1884. It was the town's high school until 1958, after which its building, a Georgian Revival wood-frame building built in 1903, became a centerpiece of the the small and experimental Franconia College (RIP) campus. The building was converted into condominium residences in 1983; it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982.

Treasure trove of life.

“Messages From the Marsh” (video still), by Amy Kaczur, in her show at Kingston Gallery, Boston, through Feb. 26.

Her Web site says:

“Kaczur’s work is grounded in environmental concerns, community and language. Her latest projects are fueled by a sense of urgency related to water issues, specifically coastal flood zones and rising sea levels. She grew up outside Cleveland, with family ties working in farming, food industry, mills, and coal mines in rural southern Ohio to the edges of Appalachia. Those roots impacted her experience of landscape and environmental issues such as pollution and climate change, and the multilayered struggles between land use and conservation. Along with examining these issues in her art practice, she works at Massachusetts Institute of Technology as the group administrator for two research labs focused on air and water pollution, climate change, and clean energy development and storage. She continuously develops her art practice, supported by relentless research, discovery by experiment, and the pleasure of inquisitive searching.’’

‘Chill & Dream’ in a sonic sanctuary on the Cape

The Pilgrim Monument in the gloaming of Provincetown.

The radio show Chill & Dream returns to the airwaves on WOMR, in Provincetown, Mass. (92.1) and on its sister signal, WFMR, in Orleans, Mass., (91.3) and streaming worldwide on womr.org on Saturday, Feb. 26 at 9 a.m. WOMR is celebrating 40 years on the air. Where were you in 1982? Need an escape in 2022? Chill & Dream is, says creator and DJ "Braintree Jim," your sonic sanctuary, exploring old and new dimensions of sight and sound. Exclusively on WOMR.

In 1940, a beachfront art class in Provincetown, long an internationally known art center.

The Jonathan Young Windmill, a restored, working 18th-Century windmill next to Town Cove in Orleans.

— Photo by ToddC4176

David Warsh: Is Putin responding to U.S. ‘hyper use’ of force and overreach?

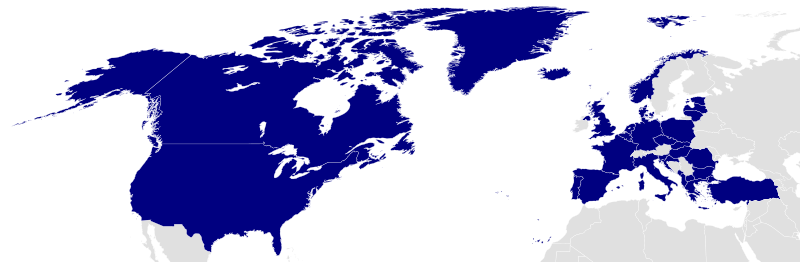

Blue indicates member states of NATO.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

With President Biden confidently forecasting a Russian “war of choice” against Ukraine –“I’m convinced he’s made the decision,” he said Feb. 18, – there is not much point in writing about it until war happens, or fails to materialize. Except to say this:

I spent some time last week leafing through books I read long ago, about an earlier “war of choice,” this one thoroughly catastrophic, as it turned – two by Robert Draper, of The New York Times, Dead Certain: The Presidency of George W. Bush, and To Start a War: How the Bush Administration took America into Iraq; one by Peter Baker, also of The Times, Days of Fire: Bush and Cheney in the White House; another by Rajiv Chandrasekaran, of The Washington Post, Imperial Lives in the Emerald City: Inside Iraq’s Green Zone; and a fifth, by Michael MacDonald, of Williams College, Overreach: Delusions of Regime Change in Iraq.

My interest was piqued by a dispatch from New York Times Moscow bureau chief Anton Troianovski. Is NATO dealing with a crafty strategist, he asked, or a reckless paranoid? “At this moment of crescendo for the Ukraine crisis, it all comes down to what kind of leader President Vladimir V. Putin is.” He continued,

In Moscow, many analysts remain convinced that the Russian president is essentially rational, and that the risks of invading Ukraine would be so great that his huge troop buildup makes sense only as a very convincing bluff. But some also leave the door open to the idea that he has fundamentally changed amid the pandemic, a shift that may have left him more paranoid, more aggrieved and more reckless.

It seemed to me that Troianovski, and, by extension, President Biden, had neglected a third interpretation. When Putin gave a famous speech at the Munich Security Conference in 2007, criticizing the U.S. for “almost un-contained hyper use of force in international relations,” he reminded listeners in his audience mainly of the American wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, which were then underway, but his subtext was NATO expansion into Eastern Europe and Eurasia after 1993.

Perhaps, I thought, the way to think of Putin is as an accomplished rhetorician, creating a grand show-of-force, illustrated by satellite photographs and maps, with which to quietly bargain with various Ukrainian factions, while seeking to persuade other audiences that for three decades the behavior of the Unites States has been the neglected element, or, as the saying goes, “ the elephant in the room.” Perhaps the long table at whose far end Putin was photographed speaking with French President Emmanuel Macron was more symbolic of the distance that the Russian president feels from NATO negotiators than emblematic of his fear of COVID contagion.

Meanwhile, The Times last week published a story about a secretive U.S. missile base in Poland a hundred miles from the Russian border – a presence that seemed to give the lie to verbal assurances given long ago in negotiations over the reunification of Germany that NATO would expand not one inch to the East.

What if Joe Biden’s convictions about Putin’s intentions turn out to be no better than were those of George W. Bush about Saddam Hussein? When Russian forces finally attack Kyiv – or gradually return to their bases – we’ll know who was right and who was wrong. I’ll stop writing about it when they decide.

While we are hanging on the breathless daily news reports, though, Putin has managed to remind more than a few persons around the world of the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, this time played out in in reverse. Was it really Pax Americana? Or more of a three-decade toot?

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

Now it’s cattle cars at 35,000 feet

Northeast Airlines DC-6B at Logan International Airport, Boston, in 1966. The Boston-based airline started up in 1931 as Boston-Maine Airways and lasted until it was merged into Delta Air Lines, in 1972.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I have to fly soon to Florida to give a talk on “working waterfronts” and am dreading it. It’s not because I fear getting COVID inside a plane, or, more likely, while waiting in a long line at airports.

No, the problem is too many angry, frustrated and non-civic-minded passengers, refusing, for example to wear masks in such crowded places. And a few get violent about it.

But then, except for travelers rich enough to fly first class, air travel is very unpleasant. 9/11 added layers of time-consuming security, including some useless “security theater,” and C0VID-19 was the coup de grace.

But the foundation of the mess was, I suppose, benign. Airline deregulation back in the ’70s led to lower fares for most airlines’ coach seats and thus far more customers. (The most famous low fares before then were offered by the East Coast “shuttle” service offered by Eastern Airlines. No reservations needed! If one plane was filled, you’d just wait for the next one to be quickly provided. I took the shuttle many times. Passengers could pay on board for their tickets with cash, order a drink and soon after takeoff light a cigarette.)

While cheap fares let millions of people who had never flown before enjoy trips to faraway places that before were out of their reach, they also turned airliners into cattle cars.

How much more pleasant, calmer and more civil it was before deregulation.

I also remember all those long-dead little airlines such as Mohawk and North Central that would take you to little cities in Upstate New York and the Upper Midwest. (North Central seemed to have an affinity for flying its sturdy DC-3’s into thunderstorms over Wisconsin. Very exciting.)

Most little airlines have since mostly been absorbed into a few behemoths.

They, like the big airlines, offered very pleasant service.

I remember as a kid being particularly impressed by Northwest Orient Airlines (what romance in the name!), once huge and now gone, having Pullman railroad car style sleeping quarters for those flying the long, long pre-jet trips to Asia. Alas, our trips to Minnesota were far too short to use them.

Before 9/11 things could be pretty relaxed on big planes. Back in 1982 I was flying back on a KLM 747 (the Dutch national airline) to Boston from Paris, where I had a job interview. I was sitting in business class, which, like the rest of the plane, was remarkably uncrowded (this during the “Reagan Recession of 1981-1982), when the pilot went for a stroll in the plane and on his way back, said to me: “Why don’t you join us (him and co-pilot) up front for a chat?’’ So I spent most of the rest of the trip (about three hours) talking with them and, from time to time, a stewardess, who also brought me a delicious meal and Heineken beer as I learned a little bit about how the huge plane worked.

Another memory: Some decades ago most passengers dressed up a bit to fly. Many men, for example, wore a jacket and tie. There was a certain dignity about it. After all, you were in a public place. Now it’s Slobovia.

Planes, like cars, are safer now, and airlines don’t allow smoking. But airline passengers, like drivers, are worse, and the prospect of flying has become a real downer

Take a deep one

“Breath” (mixed media on paper, wood panel), by Amherst, Mass.-based artist Sue Katz.

Mt. Norwottuck in the Mt. Holyoke Range, on the border between the towns of Amherst and Granby.

— Photo by Andy Anderson

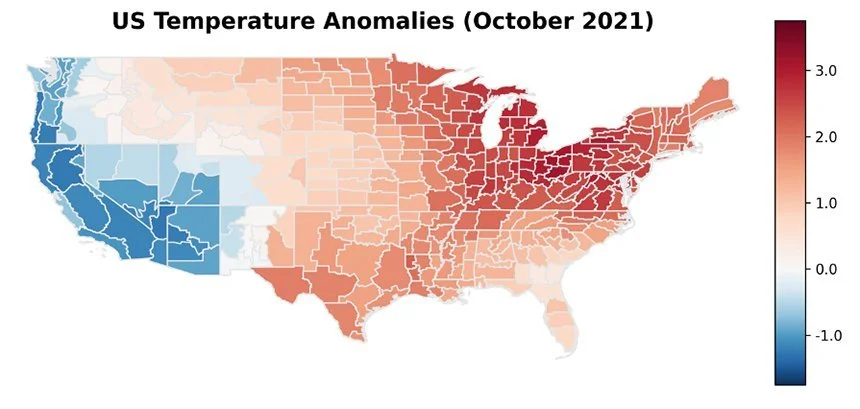

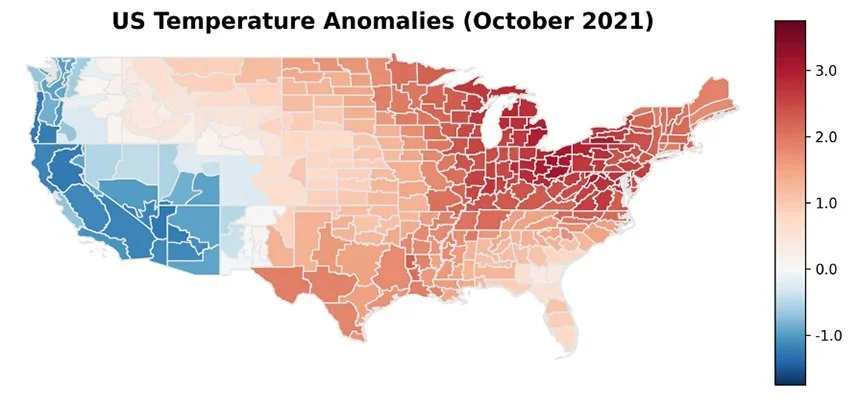

Roger Warburton: Toasty October in New England

The average temperature for October 2021 was above average across the Midwest and New England.

Roger Warburton/NCEI data)

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

During October 2021, the average U.S. temperature was 57 degrees Fahrenheit, which was 2.9 degrees above the 20th-Century average. It was sixth-warmest October in the 127-year record.

Recently released data from the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) showed temperatures above average from the Midwest through New England. Temperatures were below average on the West Coast.

Rhode Island, Massachusetts and Maine each saw their second-warmest October since 1894.

The temperature rise for Rhode Island was 2.4 degrees, which was the highest of all the New England states. While this is not a category in which the Ocean State should celebrate being No. 1, the state’s higher-than-average October temperatures meant residential energy demand was 13 percent less than average demand. It was the state’s fourth-lowest October energy demand in the 127-year record.

However, fall and winter declines in energy bills will be more than made up for by increases in cooling bills because of higher summer temperatures.

Roger Warburton, Ph.D., is a Newport, R.I., resident and contributor to ecoRI News. He can be reached at rdh.warburton@gmail.com.

Notes: NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), State of the Climate: National Climate Report for October 2021, published online November 2021, retrieved on Jan. 25, 2022 from https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/sotc/national/202110.

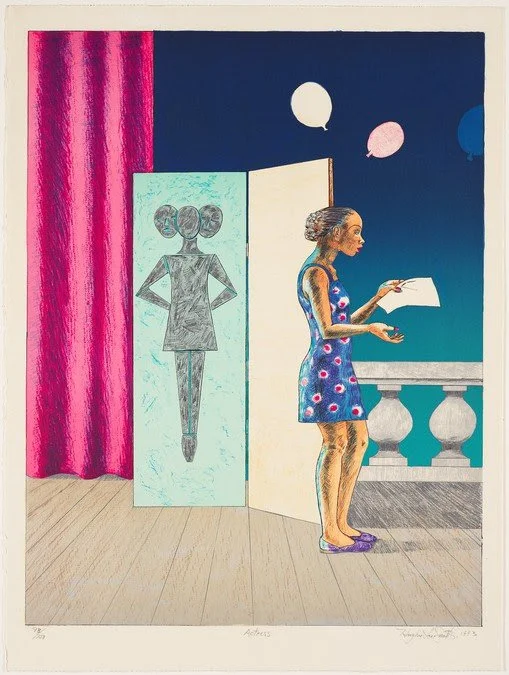

Stage fright

“Actress” (1993) (offset color lithograph), by Hughie Lee-Smith (1915-1999), in the show “Prints from the Brandywine Workshop and Archives: Creative Communities,’’ at Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, Mass., opening March 4.

The real Boston?

Twenty one people were killed on Commercial Street in Boston’s North End on Jan. 15, 1919, when a tank of molasses ruptured and exploded. An eight-foot-high wave of the syrupy brown liquid moved down Commercial Street at 35 mph. Wreckage of the collapsed tank is visible in background, center, next to light -colored warehouse.

The original Dunkin’ Donuts store, in the Boston inner-suburb of Quincy.

“I guess no true Bostonian would trust a place that was sunny and pleasant all the time. But a gritty, perpetually cold and gloomy neighborhood? Throw in a couple of Dunkin’ Donuts locations, and I’m right at home.”

— Rick Riordan (born 1964), raised in Texas, this novelist now lives in Boston.

Straining through the winter

“All winter your brute shoulders strained against collars, padding

and steerhide over the ash hames, to haul

sledges of cordwood for drying through spring and summer,

for the Glenwood stove next winter, and for the simmering range.’’

— From “Names of Horses,’’ by Donald Hall (1928-2018), a U.S. poet laureate who spent his last decades at Eagle Pond Farm, in Wilmot, N.H. This poem is a reference to the horses used by his maternal grandparents at the farm.

They’re in charge

“Crow on a Branch,’’ by Kawanabe Kyosai (1831–1889)

“Five crows, frock-coated in dignity, have arrived and sit upright and still on a bough. One thinks, ‘Oh, beloved symbols of New England’ or ‘Drat those birds,’ depending on whether one is planning a poem or a cornfield.’’

— Richard F. Merrifield, in Monadnock Journal (1975)

Purple P.M.

“Violet Afternoon’’ (oil on canvas), by Susan Abbott, at Edgewater Gallery, Middlebury, Vt. She live in northern Vermont.

Llewellyn King: College melds arcane trades with liberal arts

The American College of the Building Arts, in Charleston, S.C.

The Breakers, the famed Newport mansion, and the other great “cottages in the city, provide work for the sort of artisans traded by the American College of the Building Arts.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

It takes years to learn to fashion something out of a block of stone. You may think that you have talent, but it isn’t intuitive. You have to study stone carving, take up the mallet and chisel, waste a lot of rock, and gradually turn from novice to craftsman.

Likewise, you won’t learn the delights of English literature in a week. It takes time.

All of this can be accomplished in one extraordinary place: the American College of the Building Arts, in Charleston, S.C. — a jewel of the South with its many antebellum mansions and other buildings, making it a place of living history.

The college offers a full liberal-arts curriculum plus a specialization in one of six building arts: Classical architecture, blacksmithing, timber framing, carpentry, plaster and stone-cutting. It owes its existence to Hugo, the Category 4 hurricane that slammed into Charleston and much of the rest of the Carolina coast in 1989. Many of Charleston’s treasured homes and buildings were damaged.

Then came the second heartbreak: There was a dearth of craft workers who could put Charleston, like Humpy Dumpty, back together again. The shortage was so acute that it took more than 10 years to restore the city to what it had been pre-Hugo.

The civic pride of the city asserted itself. A group of shocked citizens vowed they wouldn’t go through that again. They would train fine artisans right there in Charleston. But they didn’t want just a trade school; they wanted a seat of learning and restoration to be part of that learning.

They didn’t want to turn out graduates who felt that they had to go through life entering through the back door. No. These would be graduates with a robust degree in liberal arts, as comfortable reading Shakespeare as helping restore a European cathedral built in his day.

So, the American College of the Building Arts was born, in 1999, and it is flourishing and growing. By college size standards, it is minuscule: 120 graduates this year. But in terms of educational creativity, it is huge. It shines a light that shows the way to a new concept of education: students learning a trade they enjoy, that is highly marketable, and also getting the benefits of four years of liberal-arts education.

In April 2018, I visited the college to film an episode of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and was captivated. I had never seen anything like it: a slight young woman working at a 2,000-degree forge, making a beautiful piece of decorative ironwork, inspired by work in a French cathedral; a woman, who had had a previous career in the Coast Guard, carving stone, with an ambition to work on the National Cathedral, in Washington; and a gifted African-American man, a former Marine who had traveled the world, working with big timbers in the framing shop.

Because I have an interest in words, I sat in on a literature course wondering secretly whether it was, perhaps, a bit cursory. It wasn’t. The former Marine timber-framing student said the literature course, taught by Wade Razzi, who has a doctorate degree from Oxford, was his favorite, and among the authors he loved was Charles Dickens.

A friend’s daughter was attracted to the college after learning about it from my television episode. He credits the college with having done wonders for her. She is a star stone carver there, likely headed to work on Liverpool Cathedral.

The college is a beacon for these reasons:

It gives its students a sense of purpose they might not have found otherwise: The reward of making something special and durable.

The college accepts men and women, although Razzi told me women were often the stars. Twenty-five percent of the students are women, and they lead in valedictorians. Five percent are veterans.

About a third of the students, within five years of graduating, start their own contracting businesses. This is so prevalent that the college has added accounting courses so that the young entrepreneurs can keep books.

The college must teach one foreign language, and that is Spanish. In a recent episode of White House Chronicle on the college, Razzi said Spanish is taught because it is essential in the building trades, where many workers are from Latin America.

One of the college’s biggest challenges is recruiting faculty, Razzi, who also serves as chief academic officer, said in that TV episode. Many faculty members come from Europe to teach arcane-in-America trades such as decorative plaster, stone carving and blacksmithing.

Some of these trades are arcane but in great demand from Newport, R.I.’s mansions – called “cottages’’ — to the National Cathedral and the Capitol, to memorial gardens. Artisans are in demand and artisans with liberal-arts credentials are something special: roundly skilled and roundly educated.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

American College of the Building Arts junior carving a stone mantle.

Waiting to hunt

Great Horned Owl

“A gravel road leads from the house to open fields that border

on both its sides, then ends abruptly

like an incomplete sentence where dense woods loom up

with depths dark as night. Here the great horned owl

makes its home, whose mating calls persist well into the predawn

when the grip of darkness begins to loosen

and dawn’s light filters through, spreading over fields and flashing

up against my house with such intensity it might set it on fire.’’

— From “Morning of the Great Horn Owl,’’ by Maurice Rigoler

Conn. insurer offering virtual primary care

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

BOST0N

“Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield has announced that its virtual primary-care service is now available to some of its more than 1 million members in Connecticut.

“Anthem, which is the market share leader in the state, joins numerous other Connecticut insurers in rolling out virtual-primary-care services since 2020. Anthem said eligible commercial members will have access to virtual primary care through the digital health app Sydney Health. The app provides access to routine services, including new prescriptions and refills, preventive tests, lab work and referrals to in-network, in-person primary and specialty care when needed.

“‘This virtual primary care offering is the latest example of our ongoing efforts to redefine the future of health care with innovative solutions — giving members more ways to connect with doctors; integrating digital, virtual, and in-person care,’ said Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield in Connecticut President Lou Gianquinto.”