Boston drunk and sober

Drunk?

“In the course of my life I have tried Boston on all sides: I have summered it and wintered it, tried it drunk and tried it sober; and, drunk or sober, there’s nothing in it — save Boston!”

— Charles Francis Adams Jr. (1835-1915), a member of the distinguished Boston Brahmin family that has included two presidents, he was an author, historian and president of the Union Pacific Railroad. Like most in his family he was highly skeptical and sardonic.

Mr. Boston, previously Old Mr. Boston, was a distillery at 1010 Massachusetts Ave. Boston, from 1933 to 1986. It produced its own label of gin, bourbon, rum and brandies, as well as a few cordials and liqueurs.

Hollywood in Hanover

“Dolores del Rio for the Trail of '98” (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1928, gelatin silver print), by Russell Ball, in “Photographs from Hollywood’s Golden Era: The John Kobal Foundation,’’ at the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College, Hanover, N.H.

The Hood’s acquisition of these photographs gives it one of the world’s largest collections of photos from Hollywood’s golden age.

The museum says that "these images cover the gamut of studio photography from portraiture and publicity shots to film stills from Hollywood’s golden era of the 1920s through the 1950s." In addition to the photographs, a virtual lecture by renown film historian and film-maker Kevin Brownlow will be held on March 3 from 12:30–1:30 EST. For more information, please visit here.

Could lineless lobstering help save North Atlantic Right Whales from extinction?

North Atlantic Right Whale mother and calf.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

A group of Massachusetts lobstermen may have a way to be allowed to resume fishing in areas that have been closed off to such fishing because the vertical lines to traps (aka “pots”) at the sea bottom can entangle, injure and kill North Atlantic Right Whales and other whales, too.

The group would use remotely controlled balloon-like devices to bring the traps to the surface without lines. I wouldn’t be surprised if regulators mandate such arrangements, though naturally some other lobstermen are angry about the potential high expense.

Besides the fact that whales are big, highly intelligent, “charismatic” fellow mammals, why should we care if they go extinct? It’s because all species are connected. If you kill off one species, it has a knock-on and usually damaging (even lethal) effect on some others. The “web of life” and all that.

Old-fashioned lobster pot.

Chris Powell: Teen’s missing teeth indict parents and state

Possible ways for adverse childhood experiences such as abuse and neglect to influence health and well-being throughout the lifespan, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

How, in a wealthy and highly taxed state with scores of social programs and constant prattling about unmet human needs, does a 17-year-old girl approach adulthood missing six teeth and able to eat only soft food?

This month a report by Theresa Sullivan Barger, of the Connecticut Health I-Team, blamed the state Department of Children and Families for not taking custody of the girl soon enough after being notified that, after a long period of abuse and neglect, she had been expelled from her home and had to move in with a friend's family.

DCF, always reluctant to remove children from their parents, replied that neglect, abuse and an inability to function independently, criteria for removing a child, are usually harder to prove as children reach their later teens.

Of course, there will be no definitive public accounting for the girl's circumstances, because DCF case work is confidential by law until there is a fatality and the state child advocate investigates and reports. Only the girl herself and her supporters are fully free to talk and give their side now. Despite the journalism here that should stoke outrage, the governor and the General Assembly will ask no questions, much less investigate, though the girl's case is another hint about the foremost problem of both Connecticut and the country -- institutionalized child neglect.

Child-protection agencies seldom cause child neglect. Mostly they just clean up after it. Those agencies often can do little more than prevent kids from being maimed or murdered amid neglect or abuse. If children turn 18 and enter the world on their own with rotted-out teeth, child protection still can consider it a success.

But don't stop with the missing teeth. How do most Connecticut children graduate from high school without mastering high school classes, many illiterate and qualified only for menial work as they reach adulthood?

A painful answer was provided in 2016 by Superior Court Judge Thomas G. Moukawsher in his decision in one chapter of Connecticut's decades-long, futile and misdirected school-financing litigation: neglect by parents compounded by neglect by state government, whose only genuine educational policy is social promotion.

Just as it's enough for state government that children should reach 18 alive, it is enough for state government that children should finish their education with diplomas they didn't earn. Poverty begins at home, with fatherlessness generated by welfare stipends, and then is perfected in school by social promotion. Abandonment of life's crucial standards is comprehensive.

Meanwhile, ever more proclamations, policies, and programs emanate from a government that is oblivious to its failure to accomplish more than its own expansion.

The most effective way for government to end poverty might be just to stop manufacturing it -- to ensure that children have parents, to stop pretending they are learning when they're not, and to start treating government as the means to an end, not the end in itself -- the end, the purpose, being the child, the future.

The writer, philosopher and Catholic polemicist G.K. Chesterton raged about similar obliviousness in government in Britain a century ago.

"With the red hair of one she-urchin in the gutter I will set fire to all modern civilization," Chesterton wrote.

"Because a girl should have long hair, she should have clean hair; because she should have clean hair, she should not have an unclean home: because she should not have an unclean home, she should have a free and leisured mother; because she should have a free and leisured mother, she should not have an usurious landlord; because there should not be an usurious landlord, there should be a redistribution of property; because there should be a redistribution of property, there shall be a revolution.

“That little urchin with the gold-red hair, whom I have just watched toddling past my house, she shall not be lopped and lamed and altered; her hair shall not be cut short like a convict's. No, all the kingdoms of the earth shall be hacked about and mutilated to suit her. She is the human and sacred image. All around her the social fabric shall sway and split and fall; the pillars of society shall be shaken, and the roofs of ages come rushing down, and not one hair of her head shall be harmed.”

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Sonali Kolhatkar: Spotify is disaster for musicians

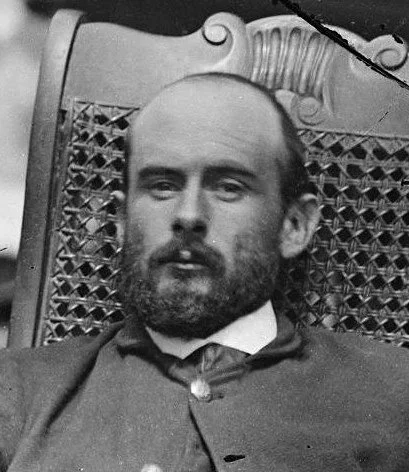

Spotify prefers Joe Rogan’s misinformation-laden podcasts to the work of musicians.

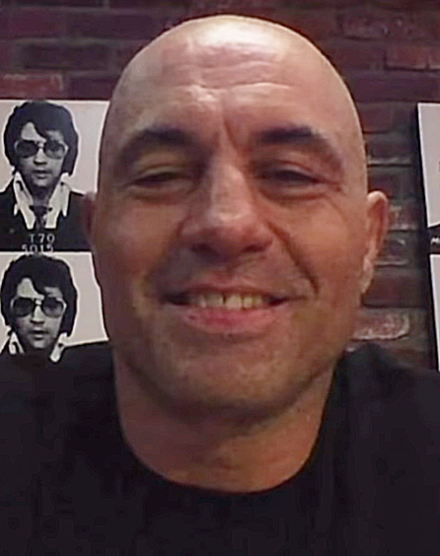

The May 1969 concert schedule for the Boston venue The Boston Tea Party displaying acts such as Led Zeppelin, the Velvet Underground and the Who.

Via OtherWords.org

Neil Young’s recent decision to pull his music from Spotify, the world’s largest streaming service, has sparked important questions about how streaming services operate.

Young demanded that the company choose between his music or Joe Rogan’s misinformation-laden podcasts. Joni Mitchell, India Arie, and Crosby, Stills, and Nash followed suit and made the same demand.

Spotify chose Rogan over all of them.

Why? “What they’re doing always comes down to profits,” says Zack Nestel-Patt, an organizer with the Union of Musicians and Allied Workers (UMAW). And Spotify sees Rogan as more profitable than even the entire catalogs of legendary musicians.

Spotify’s model isn’t the end of the world for Young, Arie or other major artists who can rely on competitors like Apple Music. But the millions of “working-class musicians struggling at the bottom of the Spotify ecosystem,” as Nestel-Patt describes them, have no such leverage.

The company’s business model, to put it simply, is built on the severely underpaid labor of millions of creators.

Say an independent musician spends years putting their heart and soul into their craft. Finally, they score a hit that garners millions of plays on Spotify. You might imagine this translates into a generous payout.

But in reality, Spotify’s paychecks are peanuts. One analyst estimated that band members with families would need more than 24 million plays on Spotify per year to just barely clear the federal poverty line.

Even those minuscule royalties may need to be split with a record label, collaborators, songwriters, managers, and more. The money that most of Nestel-Patt’s musician friends earn from Spotify is “so negligible that they don’t even account for it.”

In short, Spotify sells products that creators get almost no money to produce. It’s akin to theft. “Imagine any other business working that way,” says Nestel-Patt.

There was a time when musicians made money from selling records, cassettes and CDs — sales that were fueled by their songs being played on radio. That started changing in the late 1990s when digital platforms began offering music for little to nothing, paving the way for Spotify.

That digital transition forced musicians to rely on live performances and ticket sales to earn a living. But in 2020, when a global pandemic brought the world to a standstill, live performances abruptly stopped. “It was catastrophic for everyone I know,” recalls Nestel-Patt.

Now though, musicians are fighting back. From the ashes of musical careers rose the UMAW, where artists proclaimed that “music workers are workers, and it is time we get organized and join the fight.”

The group, which also supports universal health care, a Green New Deal, and more, led multi-city protests against Spotify in 2021. And tens of thousands of musicians signed a petition as part of UMAW’s #JusticeAtSpotify campaign.

Their demands were simple: Pay artists fairly, directly, and transparently, and treat them with dignity.

With Americans spending increasingly more money on music, there should be more than enough to go around. But even as industry revenues have risen to $43 billion a year, very little goes to musicians. Creators get only about 12 percent, with corporate middlemen sucking up a majority of the profits.

It’s not just musicians who lose out. Music itself suffers.

In a recent Atlantic magazine headline, music historian Ted Gioia asked: “Is Old Music Killing New Music?” Record labels, he observes, are “losing interest in new music.” While there’s plenty of incredible new musicians, he writes, the industry “has lost its ability to discover and nurture their talents.” And Spotify is a big reason why.

“This is as much a listener issue as it is a musicians’ issue,” argues Nestel-Patt. If Spotify relies on major pop acts or controversial podcasts for revenue, then “what happens to classical music? What happens to Tejano music? What happens to Appalachian bluegrass music?”

The ultimate losers here aren’t just those who make music. It’s all of us who love it.

Sonali Kolhatkar is the host of Rising Up With Sonali, a television and radio show on Free Speech TV and Pacifica stations. This commentary was produced by the Economy for All project at the Independent Media Institute and adapted by OtherWords.org.

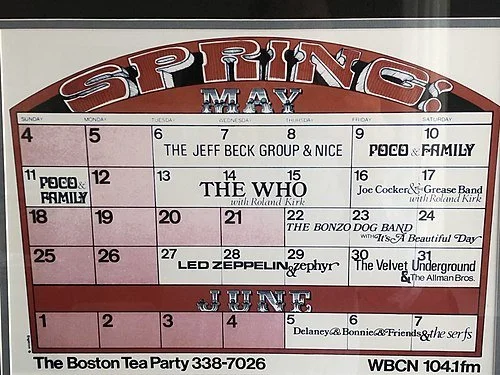

Tools of off-and-on abstraction

“Bone Music #1” (1949) (pen, ink and watercolor), by Dorothy Dehner (1901-1994), at the Yale University Art Gallery, in its group show “Midcentury Abstraction: A Closer Look,’’ Feb. 25-June 26.

The gallery says:

"Eschewing the notion that there was a linear shift toward abstraction at midcentury, the exhibition showcases a group of artists who freely moved in and out of abstraction or blended their radical approaches with traditional subject matter, such as landscape, portraiture, or still life."

John O. Harney: An early look at 2022’s college-commencement season in New England

BOSTON

From The New England Journal of Higher Education (NEJHE), a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (NEBHE.org)

Long before COVID changed everything, NEJHE and NEBHE’s Twitter channel kept a close eye on New England college commencements. “The annual spring descent on New England campuses of distinguished speakers, ranging from Nobel laureates to Pulitzer Prize winners to grassroots miracle-workers, offers a precious reminder of what makes New England higher education higher,” we bragged. “It is a lecture series without equal.”

In the past two pandemic years, we tracked a lot of postponements and virtual commencements on this beat, as well as Olin College of Engineering’s March 2020 “fauxmencement” ceremony right before coronavirus shut down the campus. Some medical schools at the time moved up graduation dates so graduates could join New England’s COVID-fighting health-care workforce. Dr. Anthony Fauci addressed graduates of the College of Holy Cross, his alma mater.

Going virtual meant hard times for some small New England communities where college-commencement days were crucial to local hospitality providers and the economy. Not to be confused with such larger commencement hosts as the Dunkin Donuts Center for Rhode Island College and Providence College and TD Garden for Northeastern University (switched to Fenway Park during COVID).

This year, as we all hope the pandemic is easing, some New England colleges plan to celebrate not only the class of 2022, but also the classes of 2020 and 2021—for the most part, in person.

Many years, we would pay special attention to the first few announcements of the season. When there was a season. Generally it was spring in the old days. But today’s nontraditional student pursing higher ed on a nontraditional academic calendar might just as easily graduate in January … or any other time for the matter.

As with other stubborn aspects of higher ed, the richest institutions often announced the heavy hitters, though sleepers at quieter places add special value too (think Paul Krugman at Bard College at Simon’s Rock or Rue Mapp at Unity College).

Harvard University, for its part, announced that the principal speaker at its 369th commencement, on May 26, would be New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern. Not a bad pick. Ardern has been lauded for her work on climate change and gender equality and, lately on how she has guided New Zealand through COVID. Harvard noted she will be “the 17th sitting world leader to deliver the address.”

John O. Harney is executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

‘Flowers as departure point’

“Bouquet “(color block & polka dots), (collage, acrylic & silkscreen on canvas), by Emily Filler, in her show “Wild Flowers,’’ at Lanoue Gallery, Boston, through March 26.

The gallery says:

“Canadian artist Emily Filler weaves painting, printmaking and photography together in her ‘painterly collages’. Using old photographs, pieces of fabric, and silk-screened images to create imaginary landscapes and whimsical bouquets of flowers, Filler’s artwork walks the line between the real and imaginary. Flowers act as a departure point to a world that dissolves into abstraction, whereby creating a sense of the familiar, but also the feeling that one is falling into a dream. What began as fragments are finalized into a complete image, something whole.’’

Chaseedaw Giles: What does it say about your Boston neighborhood if your grocery store isn’t great?

Not very healthy: A variety of Oreos line the shelves at the Stop & Shop at 460 Blue Hill Ave. in the Dorchester section of Boston.

— Photos by Chaseedaw Giles for Kaiser Health News

The Stop & Shop at 301 Centre St. in Boston’s heavily gentrified Jamaica Plain section features a large marketplace for natural and organic foods.

Though I grew up in Roxbury, “the heart of Black culture in Boston,” I now live in Los Angeles, where I typically shop for groceries at Whole Foods Market or Trader Joe’s. Their produce is fresh, green, abundant. Organic options beckon as you walk in the door.

So it gnawed at me, a Black woman, when I recently walked into a supermarket in a lower-income L.A. neighborhood and was greeted instead by an array of processed, high-sugar, high-sodium foods — often offered with a nice discount: Coca-Cola products, five 2-liter bottles for $5; sugary cereals, two for $4; boxed brownie and cake mixes, four for $5.

The pandemic had underlined long-standing health disparities of Black and brown communities. COVID had resulted in a 2.9-year decrease in life expectancy for Black Americans, compared with 1.2 years for white Americans. Research had consistently shown that among the underlying factors giving rise to those poor health statistics — high rates of diabetes and heart disease, for example — is poor diet, fueled by a lack of healthy food options in their neighborhoods.

“I could go into a supermarket, and I can tell everything about the people who live [in the area] based on what’s in their carts, based on what’s at eye level, what’s not at eye level,” said Phil Lempert, also known as the “Supermarket Guru.”

In retail, specific product placement — not just a store’s inventory — heavily influences a shopper’s experience. So shouldn’t responsible markets encourage shoppers to make better choices?

“There’s a lot of racism, to be honest, I think, behind these decisions, whether it’s unconscious or implicit,” said Andrea Richardson, a policy researcher focused on nutrition epidemiology at the Rand Corp. and professor at the Pardee Rand Graduate School. The presence of a supermarket in your neighborhood should signal that you aren’t living in a food desert, but, I wondered, if the supermarket isn’t guiding you toward more healthful food choices, you might as well be.

Chaseedaw and Lilie’s Shopping List

– Oat milk

– Lettuce

– Ezekiel bread

– Breakfast sausage (MorningStar)

– Fruit

– Cereal

– Cashew cheese

– Quinoa

– Snacks/chips

– Soda/juice

– Meat (fish)

– Mushrooms

So when I flew home for Thanksgiving, I enlisted my mother, Lilie — who always cared about her kids’ diets — to help with more research. I have vivid childhood memories of her scouring multiple grocery stores — often traveling to different parts of town — for the freshest ingredients when none were available close by. We set out one Sunday last fall to buy 12 items on a simple “healthy eating” shopping list at five locations of Stop & Shop, a supermarket chain with stores in a cross-section of Boston neighborhoods.

First the good news: We were able to find every item we wanted at each store. But, just as I’d experienced in L.A., healthy foods were easier to find in higher-income neighborhoods. In lower-income areas, junk food was more likely to be front and center.

At the Stop & Shop I recall from my childhood in Jamaica Plain, the food choices had become much more balanced, with a plentiful organic food section in the front of the store. My mom can now buy fresher greens locally.

But that likely in part reflects the gentrification that has taken place since I was a kid. Jamaica Plain now has a median income of almost $77,000 — though the poverty rate is 18.3 percent and the aroma of Dominican and Haitian patties still scented the air as we approached the entrance.

Our next two stops were in even fancier areas, Brookline (median income over $115,000) and Somerville — both green oases compared with many of Boston’s grittier neighborhoods.

At the Brookline location, each aisle started with low-fat, low-sugar choices like Crystal Light and V8, and the candy section was minuscule. In Somerville, the produce section was spacious, leaving plenty of room to browse the bins of guava and dragon fruit.

Our next Stop & Shop was in South Boston — a working-class, Irish Catholic community. It was strikingly different than our first three stops. The organic section consisted mostly of breakfast bars and cereals. The produce section positioned caramels, candied apples, and pumpkin-spice doughnuts in a bin alongside regular apples — at the bargain price of two packages for $3. The “International Foods” aisle sold everything you need for a very American Taco Tuesday, while a big part of this section was dedicated to Italian and Irish foods.

In the Grove Hall neighborhood in Dorchester — a predominantly Black neighborhood with a median income of $55,000 — the offerings were downright dispiriting.

Soda was displayed prominently near one entrance. And as we walked the aisles it seemed that many of the “sale” items were sugary soda products, chips, or cookies. This store had a dizzying array of snack food options, including 20 kinds of Oreos. And there wasn’t an organic food section at all.

The chain has been “doing a lot of work” to make sure that stores are “culturally relevant and [reflect] the demographics of the neighborhood,” said Jennifer Brogan, director of Stop & Shop’s corporate external communications and community relations.

How a store is stocked depends on size, product movement, shelf size, and a mixture of customer feedback and data. That data comes from companies like IRi, a research company, that provides consumer, shopper, and retail market intelligence and analyses.

Lempert, the “supermarket guru,” further explained that companies and brands pay retailers “promotional dollars” to put their goods “at eye level” or on sale, or make them available for consumers to sample.

But in making these largely commercial decisions, markets make it more difficult for people in low-income areas to eat healthfully, encouraging those with poor diets to continue the habits that landed them with diet-related illnesses.

“It has been well documented that junk-food companies spend significantly more money advertising in certain communities,” said Kelly LeBlanc, director of nutrition at Oldways, a Boston-based food and nutrition nonprofit. A 2019 report, for instance, found that junk-food advertising disproportionately targeted Black and Hispanic youth.

Stop & Shop has started to try to redress the inequity, with changes coming first to its Dorchester location, including an in-store dietitian. The Grove Hall store also sends out an ad circular that features promotional pricing on better-for-you items, which may include fish, vegetables, and fruit. It has joined the Fresh Connect food prescription program that allows participating doctors to prescribe to patients a prepaid Visa card that can be used to purchase fruits and vegetables.

Still, why not simply cut down on the soda and bewildering number of Oreos, I wondered. “I think our job is to give customers a choice,” Brogan said. “I also think we have a responsibility to help them make healthier choices.”

I’m glad my mom taught me how to make those choices early on.

Another thing I learned: There’s a whole science behind how supermarkets are organized, and depending on where you live, that could say a lot about the surrounding area. So the next time I think about moving, the first place I’m heading to is the local supermarket because, as Lempert told me, “going to that community grocery store is going to tell you about the neighborhood.”

Chaseedaw Giles is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Perhaps we aren't doomed?

“Exuberance, Green” (clay, papier mache, wire), by Boston and Biddeford, Maine-based Rhonda Smith, in her show “Say That I Am You,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, through Feb. 27.

The gallery says:

Rhonda Smith’s sculptures “evoke humanity’s connection to the universe through the poetry of Rumi. Her multimedia pieces combine disparate elements of nature to create works that challenge the notion that destruction is our only future.’’

Melding buildings and landscape

Henry Hobson Richardson’s famous Trinity Church (built 1872-1877) on Boston’s Copley Square.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Many people have seen the great Gilded Age architect Henry Hobson Richardson’s (1838-1886) famous public and private buildings around America, with Boston’s grand Trinity Church still the most famous. Richardson invented a unique Romanesque Revival style with ingenious massing and use of stone, and he was also a pioneer in developing the remarkably modernist “Shingle Style” houses so popular in New England.

And yet while Richardson was very well known in his fairly short lifetime, few people now know his name, even though many historians consider him a founder of modern American architecture.

But Hugh Howard has come along to help rectify that with his duel biography Architects of an American Landscape: Henry Hobson Richardson, Frederick Law Olmsted, and the Reimagining of America’s Public and Private Spaces.

Olmsted (1822-1903), unlike Richardson, remains famous, as the co-designer of Central Park and designer of many other famous parks, such as those in Boston’s “Emerald Necklace,’’ across America. Many see him as the father of American landscape architecture.

Richardson and Olmsted, despite very different backgrounds and personalities, worked very closely on dozens of commissions for cooperative designs for parks, railroad stations, public libraries and houses. Their projects integrated the built and natural environments. Many of these collaborations resulted in Richardson’s buildings looking comfortably settled into Olmsted’s landscaping.

Olmsted said of Richardson:

“He was the greatest comfort and the most potent stimulus that has ever come into my artistic life.”

This is a terrific book, elegantly written. It would have even better with bigger and clearer pictures.

In Waltham, Mass.: “Stonehurst,’’ now a museum and built for Boston Brahmin lawyer Robert Treat Paine. Richardson designed the house and Olmsted the grounds, in close collaboration, in a project that took from 1883-1886.

Raise your voice of protest

Protesters on Atlantic Avenue, Boston, on Oct. 3, 2011

— Photo by Tim Pierce

“The voice of protest, of warning, of appeal is never more needed than when the clamor of fife and drum, echoed by the press and too often by the pulpit, is bidding all men fall in and keep step and obey in silence the tyrannous word of command. Then, more than ever, it is the duty of the good citizen not to be silent.”

— Charles Eliot Norton (1827-1908), American author, social critic and Harvard professor

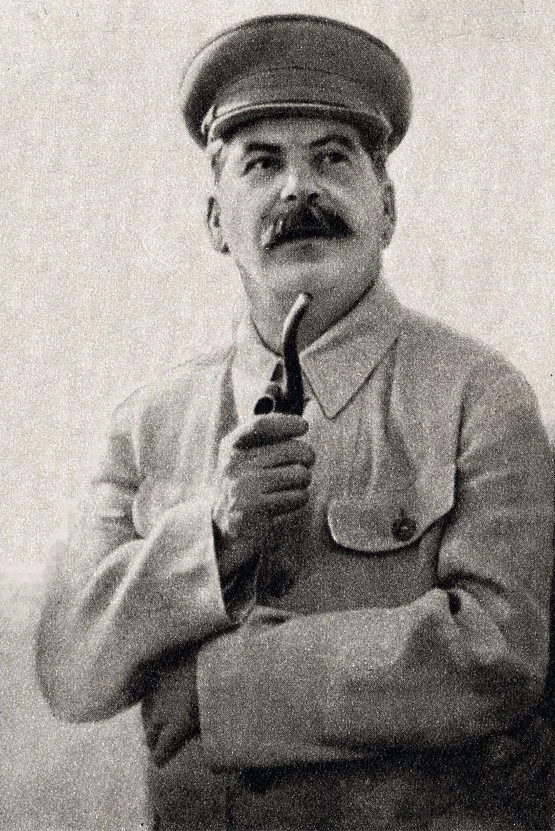

David Warsh: What brought us to today's Russia; Stalin's library

A kindly-looking Stalin — mass murderer and true believer

— 1937 Soviet propaganda photo

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

As a newspaperman covering the economics of transition after 1989, I became interested in the Russian experience of the ‘90s, especially after a young Russian immigrant who, having become a Harvard economics professor, took advantage of his appointment as a U.S. State Department adviser to the government of Boris Yeltsin to enter the Russian mutual-fund industry with his wife and their pals.

Since then I’ve followed the story of U.S.-Russian relations as it has gradually widened into front-page news. A friend pointed me to a fascinating book by a young philosopher about her and her family’s experience in Albania in the early ‘90s. That book, in turn, reminded me of a somewhat older account of coming-of-age as an economist in communist Hungary during the ‘60s and ‘70s.

Free: A child and a country at the end of history (Norton, 2022), by Lea Ypi, a professor of political philosophy in the government of the London School of Economics, is consistently engaging, at least until its chapter on Albanian civil wars of 1997 (at which point it turns horrifying), though it offers very little interpretation of the historical Marx. This Lunch with the FT feature, by Alec Russell, describes Ypi and her views very well, but fails to tell how she pronounces her name. (It’s Ee-P, just as you would say the name of this weekly.)

The older story is By Force of Thought: Irregular memoirs of an intellectual journey, by János Kornai (MIT, 2006). Kornai died last year, at 93. For an account of his hard, heroic, ultimately distinguished career, see Klaus Nielsen’s obituary in the Guardian, or Eric Maskin’s tribute for Econometrica. More is the pity that, though often nominated, Kornai failed to be included in the Nobel pantheon; he left behind the best account that we possess of the economics of chronic shortage in centrally planned economies.

Perusing these books led in turn to Tony Barber’s review of Stalin’s Library: A dictator and his books (Yale, 2022), by historian Geoffrey Roberts. As its dictator between 1922 and 1953 (when he died), Stalin created the modern Soviet Union, killing millions of his fellow countrymen in the name of “class struggle,” while delivering victory over the Nazis at Stalingrad (previously Volgograd) in World War II, occupying half of Europe afterwards, and producing the nuclear weapons and missiles that stood off the West in a Cold War lasting forty years. It turns out that Stalin was quite the reader, possessing a personal library of 25,000 books, including more than 400 that he personally annotated. Barber writes,

Of exceptional interest are the pometki, or markings, on the books that Stalin read most closely. Using red, blue and green pencils, he scribbled expressions of disdain or disagreement: “ha ha”, “hee hee”, “gibberish”, “nonsense”, “rubbish”, “fool”, “bastards”, “scumbag”, “swine”, “liar”, “scoundrel” and “piss off”. Yet the author he read most was Vladimir Lenin, and there is not a hint of criticism in his markings on Lenin’s works — or, indeed, on those of Karl Marx.

As this suggests, Stalin was no skeptical thinker weighing up all sides of a question. He started from the premise that Marxism-Leninism had the answers. Roberts makes a convincing case that the key to understanding Stalin’s capacity for mass murder is “hidden in plain sight: the politics and ideology of ruthless class war in defense of the revolution and the pursuit of communist utopia”.

Through the tumultuous ‘80’s and the smash-and-grab ‘90’s, Russia found its way to a market economy. See Greg Ip’s well-informed appraisal of stakes the nation is facing in the current situation. Vladimir Putin is not Joseph Stalin, but he is a gambler. Keep that in mind as you read about the show-of-force bargaining now taking place over the future of Ukraine.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first appeared.

Don Pesci: ‘Honest graft’ in Connecticut

John Bailey and John F. Kennedy, whom Mr. Bailey helped make president.

VERNON, Conn.

John Bailey (1904-1975) Connecticut’s Democratic Party chairman from 1946-1975 and national Democratic chairman from 1961 to 1968, dominated Connecticut politics from 1950 until his death. He coordinated his party’s politics in Connecticut and oversaw election campaigns in the state’s General Assembly, which is a polite way of saying he pulled most of the political strings in what used to be a rock-ribbed Republican state. When he had finished bossing Democrats, his party had become a bastion of highly electable Jewish and Catholic politicians, such as Gov. Abraham Ribicoff, U.S. Sen.Thomas Dodd, Gov. John Dempsey and Gov. Ella T. Grasso.

The reformed post-modern Democratic Party of today is considerably less disciplined, and political candidates have long discovered that the two major parties are little more than flags under which Democrats and Republicans gather to sport the wares of individual savior politicians, all of whom are responsible for raising their own campaign funds. Nearly every major politician of long standing in Connecticut is, in effect, his own political party. The party boss is dead these many years. Long live party primaries, which resemble nothing so much as Thomas Hobbes’ s view of life in general "nasty, brutish and short."

Candidates in the post-modern period are expected to generate their own campaign funds, an arrangement that most often gives an unsurpassable advantage to tiresome incumbents. In the upcoming Connecticut U.S. senatorial contest, incumbent Dick Blumenthal will be carrying into his new campaign old money generated in past campaigns.

According to Open Secrets, Blumenthal raised $8,825,840 in his last campaign, spent $5,891,505, and left $2,953,419 in his campaign kitty or future use. Blumenthal’s opponent during his last campaign, Dan Carter, raised $366,217 and spent $358,095.

Rosa DeLauro, a progressive candidate in Connecticut’s Third District (New Haven and some of its suburbs), produces on average $1.2 million in her campaigns, spends far less and donates the surplus to the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, a portion of which -- in what used to be considered a quid pro quo among alert, nonpartisan reporters and editors in the state – is returned to the DeLauro household in the form of jobs for DeLauro’s husband, Stanley Greenberg, a pollster to progressives and twinkling Democrat politicians.

“Federal Election Commission data reveal that over the past four election cycles, Rep. Rosa L. DeLauro (D.-Conn.) donated more than $ 1.2 million dollars to the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee,” Human Events reported a few years ago. “Over that same time period, the DCCC paid $1.9 million for polling services to Greenberg Quinlan Rosner Research. GQRR’s founding partner is DeLauro’s husband of 33 years, Stanley B. Greenberg.”

All this is what New York’s Tammany Hall in its lustrous heyday used to call “honest graft” – that is to say, perfectly legal, self-serving enrichment. The great trick in post-modern politics is to write legislation that seemingly puts an end to dubious activity and yet imports into such legislation loopholes that do not interfere with the reprehensible activities of incumbent politicians.

Just now, the Great Incumbency is exercising itself over reforming what used to be called in the good old days insider trading and stock-option speculation. After reports emerged that U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and her investment-savvy husband may have been flirting with both, Pelosi quickly jumped on an emerging bandwagon denouncing insider trading among members of Congress.

Political corruption, like the poor, will always be with us, but campaign limits likely would tend to equalize corruption among a new brood of politicians. And, an additional benefit, limited terms in office would stir the party pot. Blumenthal would not have been state attorney general for 20 years if term limits had been in effect decades ago. He might have been senator much earlier, or governor or simply a wealthy, retired ex-officio figurehead of his party, like former President Barack Obama, who some suspect may be getting ready to shoehorn his wife into the presidency – the first Black woman president, don’t you know.

Recently, the Washington Free Beacon shot a corruption tipped arrow in Blumenthal’s direction:

“Blumenthal disclosed that he and his wife sold between $1,265,000 and $2,550,000 worth of shares of Robinhood in the last quarter of 2021. At the time, Blumenthal joined a chorus of lawmakers in calling for investigations into Robinhood's role in supporting a speculation frenzy involving shares of GameStop. Blumenthal did not probe the matter even though he was well positioned to do so as the chairman of the Senate Commerce Subcommittee on Consumer Protection.

“Blumenthal's disclosures come amid debate on Capitol Hill over whether lawmakers and their spouses should be banned from trading stocks. Lawmakers from both parties have proposed bills to limit or outright ban stock trades. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D.- Calif.), one of the most prolific stock traders in Congress, endorsed a proposal … to ban members from trading stocks. Blumenthal has yet to sponsor any of the bills proposed in the Senate.”

In high dudgeon, Blumenthal responded that his stock portfolio, handled by others, was hardened against corruption and that he didn’t know what was in it.

Sure, sure, blind trusts are neither totally blind nor corruption-free. It in the bad old days of Bailey bossism, watchful bosses in both parties kept a critical eye on such things before they pulled an Ella Grasso into a governorship or an often recirculated Abraham Ribicoff into the U.S. House, the U.S. Senate and the governorship of Connecticut.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

Frank Carini: Valiantly fighting epidemic of shoreline trash

During a single day in May 2019, Geoff Dennis and trusted sidekick Koda collected 282 balloons from the Little Compton, R.I., coastline. It was the duo’s largest balloon haul.

— Courtesy photos

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

The mission is simple but the work is aggravating, especially since Geoff Dennis’ four-legged buddy no longer joins him on the almost-daily treks. Also, he doesn’t get paid.

For the past decade, the Little Compton, R.I., resident has been picking up other people’s trash that accumulates along the local shoreline. Between 2012 and 2020, Dennis picked up 35,607 pieces of litter from the banks of the Sakonnet River, at Goosewing Beach Preserve and a few other places. The vast majority of it was some form of plastic, from bottles to spent shotgun shells.

Despite “still missing my boy Koda” — his trusted black Lab died two days after Christmas 2020 at the age of 14 — the longtime quahogger and bird photographer remains a one-person cleanup crew.

“I miss him as much today as that last day with him,” Dennis said.

His immersion into litter began in 2012 while monitoring piping plovers at Goosewing Beach for The Nature Conservancy. The amount of plastic debris at his feet disgusted him.

When he returned, he picked up more than 100 Mylar balloons from the area. He’s been picking up coastline trash ever since. He’s bothered that 10 years later, most people still don’t seem to care about the state’s growing plastic problem.

Dennis said graduation time brings the greatest number of depleted balloons. July and August are the height of trash collection.

He recently tallied up his 2021 trash scorecard. Here is the breakdown:

Mylar balloons: 1,388.

Plastic bottles and aluminum cans: 1,349. He said year-end totals do not include old plastic bottles that have “become eggshell brittle and started the process of fragmenting. They go directly to trash.”

Plastic bottle caps: 1,209.

Latex balloons: 780. He said latex balloons are usually only the mouth piece, or ring piece, with attached ribbon. “I do find shredded pieces of latex too, but tally only the ring. Sometimes difficult to count when it may be a 30-plus mass of rings and tangled ribbon.”

Plastic straws: 328.

Spent plastic shotgun shells: 302.

Nips: 195.

Rubber gloves: 164.

Plastic and foam cups: 132. He said Dunkin’ Donuts (67) and Cumberland Farms (38) cups are the most common. “CF is still using foam cups and all found are foam. DD ceased using foam in 2020. Plenty of their paper cups were collected but are not in the tally.”

Golf balls: 119.

Plastic lids for plastic and foam cups: 104.

Plastic wads for shotgun shells: 86.

Plastic bags: 66.

Plastic cigarette lighters: 50.

Plastic K-cups: 45.

Since Dennis returned to Goosewing Beach 10 years ago to pick up Mylar balloons, there are 41,924 fewer pieces of litter along the Little Compton shoreline.

A trio of bills has been introduced during the current General Assembly session to address the Ocean State’s plastic pollution problem, including legislation to ban the sale of nips.

Frank Carini is senior reporter and co-founder of ecoRI News.

The Benjamin Family Environmental Center at the Goosewing Beach Preserve

The Sakonnet River as viewed from Portsmouth, R.I., looking south towards the ocean.

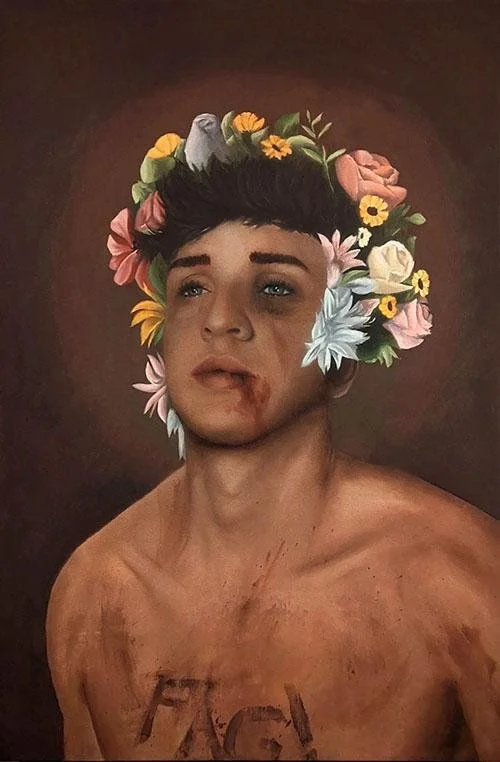

In spite of it all

“Gentle Fortitude’’ (oil on canvas), by Erik Carter, in the group show “Ardor,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, through Feb. 27. Mr. Carter is a Boston-based painter and virologist.

The gallery explains that the show is a collection of work by New England artists that reflects passion and zeal.

Media includes painting, mixed media, photography and drypoint.

Busy, busy, busy

“Gloucester Humoresque” (1923, oil on canvas), by William Meyerowitz (1896-1981) at the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass.

‘Magical mystery tour’

—Photo by Petar Milošević

“Criticizing Boston’s taxicabs is about as controversial as taking a stand against earthquakes, ax murderers, or the Third Reich….The drivers themselves are generally friendly but often topographically confused….No two rides are the same. No two taxis take you from Point A to Point B via Route C. And even if they do, the fares are somehow different. To enter a taxi in The Hub is to embark on a magical mystery tour of assorted mechanical surprises and geographic wonders.’’

— Nathan Cobb, in “Taxiing Toward a Fun City, in Cityside/Countryside (1980)

Maybe more reliable? Outside Boston’s Brutalist City Hall.

‘Glad of the burn’

“The Magpie,’’ by Claude Monet (1869)

Preston City Congregational Church

“I crouch down in blank

snow, glad of the burn

of cold air in the west,

the border of trees

black and still.’’

— From “Beginner’s Mind,’’ by Margaret Gibson (born 1944). She’s poet laureate of Connecticut and an emeritus professor at the University of Connecticut. She lives in Preston, Conn.

In the Hallville Mill Historic District, in Preston.

Information below is mostly an edited-down version of a Wikipedia entry on Preston.

“Properties in the district include 25 structures on a 50-acre site. The district includes the dam forming Hallville Pond (a mill pond — above), historic manufacturing buildings and worker housing, and the Hallville Mill Bridge, a lenticular pony truss bridge built circa 1890 by the Berlin Iron Bridge Co.

“The first mill there was built in 1752 for finishing locally produced homespun woolen cloth, with carding machines added in the early 19th Century.

“In 1857 Joseph Hall Sr., a weaver born in England, built an industrial-scale woolen mill on the site. The mill remained under his family's ownership under the name Hall Brothers' Woolen Mill (named for the founder's sons) and was expanded over the years. As of 1888 the mill employed 175 workers and produced 860,000 yards of cloth annually. The mill burned down in 1943, but manufacturing continued in Hallville until the 1960s and was a major source of employment and tax revenue for Preston.’’

It’s a classic small New England mill town. Sadly, the huge and sleazy Foxwoods casino is all too close, in Ledyard.

The joy of misdirection

Moose, Maine’s official state mammals, have bigger antlers than game wardens. Maine has more moose than any other state besides Alaska.

“Don’t ever ask directions of a Maine native….Somehow we think it funny to misdirect people and we don’t smile when we do it, but we laugh inwardly. It’s our nature.’’

— A Maine native, quoted by the novelist John Steinbeck (1902-1968), in his travel journal Travels with Charley (1962)

Hit this link for video!

xxx

“There are only two things that ever make the front page in Maine papers. One is a forest fire and the other is when a New Yorker shoots a moose instead of the game warden.’’

Actor/comedian/writer Groucho Marx (1890-1977) in a letter to Variety, Aug. 23, 1934