Raise your voice of protest

Protesters on Atlantic Avenue, Boston, on Oct. 3, 2011

— Photo by Tim Pierce

“The voice of protest, of warning, of appeal is never more needed than when the clamor of fife and drum, echoed by the press and too often by the pulpit, is bidding all men fall in and keep step and obey in silence the tyrannous word of command. Then, more than ever, it is the duty of the good citizen not to be silent.”

— Charles Eliot Norton (1827-1908), American author, social critic and Harvard professor

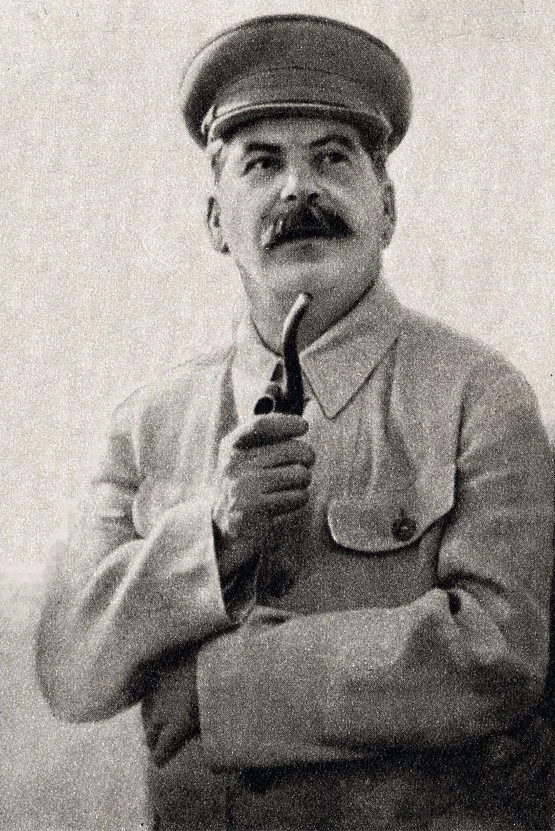

David Warsh: What brought us to today's Russia; Stalin's library

A kindly-looking Stalin — mass murderer and true believer

— 1937 Soviet propaganda photo

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

As a newspaperman covering the economics of transition after 1989, I became interested in the Russian experience of the ‘90s, especially after a young Russian immigrant who, having become a Harvard economics professor, took advantage of his appointment as a U.S. State Department adviser to the government of Boris Yeltsin to enter the Russian mutual-fund industry with his wife and their pals.

Since then I’ve followed the story of U.S.-Russian relations as it has gradually widened into front-page news. A friend pointed me to a fascinating book by a young philosopher about her and her family’s experience in Albania in the early ‘90s. That book, in turn, reminded me of a somewhat older account of coming-of-age as an economist in communist Hungary during the ‘60s and ‘70s.

Free: A child and a country at the end of history (Norton, 2022), by Lea Ypi, a professor of political philosophy in the government of the London School of Economics, is consistently engaging, at least until its chapter on Albanian civil wars of 1997 (at which point it turns horrifying), though it offers very little interpretation of the historical Marx. This Lunch with the FT feature, by Alec Russell, describes Ypi and her views very well, but fails to tell how she pronounces her name. (It’s Ee-P, just as you would say the name of this weekly.)

The older story is By Force of Thought: Irregular memoirs of an intellectual journey, by János Kornai (MIT, 2006). Kornai died last year, at 93. For an account of his hard, heroic, ultimately distinguished career, see Klaus Nielsen’s obituary in the Guardian, or Eric Maskin’s tribute for Econometrica. More is the pity that, though often nominated, Kornai failed to be included in the Nobel pantheon; he left behind the best account that we possess of the economics of chronic shortage in centrally planned economies.

Perusing these books led in turn to Tony Barber’s review of Stalin’s Library: A dictator and his books (Yale, 2022), by historian Geoffrey Roberts. As its dictator between 1922 and 1953 (when he died), Stalin created the modern Soviet Union, killing millions of his fellow countrymen in the name of “class struggle,” while delivering victory over the Nazis at Stalingrad (previously Volgograd) in World War II, occupying half of Europe afterwards, and producing the nuclear weapons and missiles that stood off the West in a Cold War lasting forty years. It turns out that Stalin was quite the reader, possessing a personal library of 25,000 books, including more than 400 that he personally annotated. Barber writes,

Of exceptional interest are the pometki, or markings, on the books that Stalin read most closely. Using red, blue and green pencils, he scribbled expressions of disdain or disagreement: “ha ha”, “hee hee”, “gibberish”, “nonsense”, “rubbish”, “fool”, “bastards”, “scumbag”, “swine”, “liar”, “scoundrel” and “piss off”. Yet the author he read most was Vladimir Lenin, and there is not a hint of criticism in his markings on Lenin’s works — or, indeed, on those of Karl Marx.

As this suggests, Stalin was no skeptical thinker weighing up all sides of a question. He started from the premise that Marxism-Leninism had the answers. Roberts makes a convincing case that the key to understanding Stalin’s capacity for mass murder is “hidden in plain sight: the politics and ideology of ruthless class war in defense of the revolution and the pursuit of communist utopia”.

Through the tumultuous ‘80’s and the smash-and-grab ‘90’s, Russia found its way to a market economy. See Greg Ip’s well-informed appraisal of stakes the nation is facing in the current situation. Vladimir Putin is not Joseph Stalin, but he is a gambler. Keep that in mind as you read about the show-of-force bargaining now taking place over the future of Ukraine.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first appeared.

Don Pesci: ‘Honest graft’ in Connecticut

John Bailey and John F. Kennedy, whom Mr. Bailey helped make president.

VERNON, Conn.

John Bailey (1904-1975) Connecticut’s Democratic Party chairman from 1946-1975 and national Democratic chairman from 1961 to 1968, dominated Connecticut politics from 1950 until his death. He coordinated his party’s politics in Connecticut and oversaw election campaigns in the state’s General Assembly, which is a polite way of saying he pulled most of the political strings in what used to be a rock-ribbed Republican state. When he had finished bossing Democrats, his party had become a bastion of highly electable Jewish and Catholic politicians, such as Gov. Abraham Ribicoff, U.S. Sen.Thomas Dodd, Gov. John Dempsey and Gov. Ella T. Grasso.

The reformed post-modern Democratic Party of today is considerably less disciplined, and political candidates have long discovered that the two major parties are little more than flags under which Democrats and Republicans gather to sport the wares of individual savior politicians, all of whom are responsible for raising their own campaign funds. Nearly every major politician of long standing in Connecticut is, in effect, his own political party. The party boss is dead these many years. Long live party primaries, which resemble nothing so much as Thomas Hobbes’ s view of life in general "nasty, brutish and short."

Candidates in the post-modern period are expected to generate their own campaign funds, an arrangement that most often gives an unsurpassable advantage to tiresome incumbents. In the upcoming Connecticut U.S. senatorial contest, incumbent Dick Blumenthal will be carrying into his new campaign old money generated in past campaigns.

According to Open Secrets, Blumenthal raised $8,825,840 in his last campaign, spent $5,891,505, and left $2,953,419 in his campaign kitty or future use. Blumenthal’s opponent during his last campaign, Dan Carter, raised $366,217 and spent $358,095.

Rosa DeLauro, a progressive candidate in Connecticut’s Third District (New Haven and some of its suburbs), produces on average $1.2 million in her campaigns, spends far less and donates the surplus to the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, a portion of which -- in what used to be considered a quid pro quo among alert, nonpartisan reporters and editors in the state – is returned to the DeLauro household in the form of jobs for DeLauro’s husband, Stanley Greenberg, a pollster to progressives and twinkling Democrat politicians.

“Federal Election Commission data reveal that over the past four election cycles, Rep. Rosa L. DeLauro (D.-Conn.) donated more than $ 1.2 million dollars to the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee,” Human Events reported a few years ago. “Over that same time period, the DCCC paid $1.9 million for polling services to Greenberg Quinlan Rosner Research. GQRR’s founding partner is DeLauro’s husband of 33 years, Stanley B. Greenberg.”

All this is what New York’s Tammany Hall in its lustrous heyday used to call “honest graft” – that is to say, perfectly legal, self-serving enrichment. The great trick in post-modern politics is to write legislation that seemingly puts an end to dubious activity and yet imports into such legislation loopholes that do not interfere with the reprehensible activities of incumbent politicians.

Just now, the Great Incumbency is exercising itself over reforming what used to be called in the good old days insider trading and stock-option speculation. After reports emerged that U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and her investment-savvy husband may have been flirting with both, Pelosi quickly jumped on an emerging bandwagon denouncing insider trading among members of Congress.

Political corruption, like the poor, will always be with us, but campaign limits likely would tend to equalize corruption among a new brood of politicians. And, an additional benefit, limited terms in office would stir the party pot. Blumenthal would not have been state attorney general for 20 years if term limits had been in effect decades ago. He might have been senator much earlier, or governor or simply a wealthy, retired ex-officio figurehead of his party, like former President Barack Obama, who some suspect may be getting ready to shoehorn his wife into the presidency – the first Black woman president, don’t you know.

Recently, the Washington Free Beacon shot a corruption tipped arrow in Blumenthal’s direction:

“Blumenthal disclosed that he and his wife sold between $1,265,000 and $2,550,000 worth of shares of Robinhood in the last quarter of 2021. At the time, Blumenthal joined a chorus of lawmakers in calling for investigations into Robinhood's role in supporting a speculation frenzy involving shares of GameStop. Blumenthal did not probe the matter even though he was well positioned to do so as the chairman of the Senate Commerce Subcommittee on Consumer Protection.

“Blumenthal's disclosures come amid debate on Capitol Hill over whether lawmakers and their spouses should be banned from trading stocks. Lawmakers from both parties have proposed bills to limit or outright ban stock trades. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D.- Calif.), one of the most prolific stock traders in Congress, endorsed a proposal … to ban members from trading stocks. Blumenthal has yet to sponsor any of the bills proposed in the Senate.”

In high dudgeon, Blumenthal responded that his stock portfolio, handled by others, was hardened against corruption and that he didn’t know what was in it.

Sure, sure, blind trusts are neither totally blind nor corruption-free. It in the bad old days of Bailey bossism, watchful bosses in both parties kept a critical eye on such things before they pulled an Ella Grasso into a governorship or an often recirculated Abraham Ribicoff into the U.S. House, the U.S. Senate and the governorship of Connecticut.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

Frank Carini: Valiantly fighting epidemic of shoreline trash

During a single day in May 2019, Geoff Dennis and trusted sidekick Koda collected 282 balloons from the Little Compton, R.I., coastline. It was the duo’s largest balloon haul.

— Courtesy photos

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

The mission is simple but the work is aggravating, especially since Geoff Dennis’ four-legged buddy no longer joins him on the almost-daily treks. Also, he doesn’t get paid.

For the past decade, the Little Compton, R.I., resident has been picking up other people’s trash that accumulates along the local shoreline. Between 2012 and 2020, Dennis picked up 35,607 pieces of litter from the banks of the Sakonnet River, at Goosewing Beach Preserve and a few other places. The vast majority of it was some form of plastic, from bottles to spent shotgun shells.

Despite “still missing my boy Koda” — his trusted black Lab died two days after Christmas 2020 at the age of 14 — the longtime quahogger and bird photographer remains a one-person cleanup crew.

“I miss him as much today as that last day with him,” Dennis said.

His immersion into litter began in 2012 while monitoring piping plovers at Goosewing Beach for The Nature Conservancy. The amount of plastic debris at his feet disgusted him.

When he returned, he picked up more than 100 Mylar balloons from the area. He’s been picking up coastline trash ever since. He’s bothered that 10 years later, most people still don’t seem to care about the state’s growing plastic problem.

Dennis said graduation time brings the greatest number of depleted balloons. July and August are the height of trash collection.

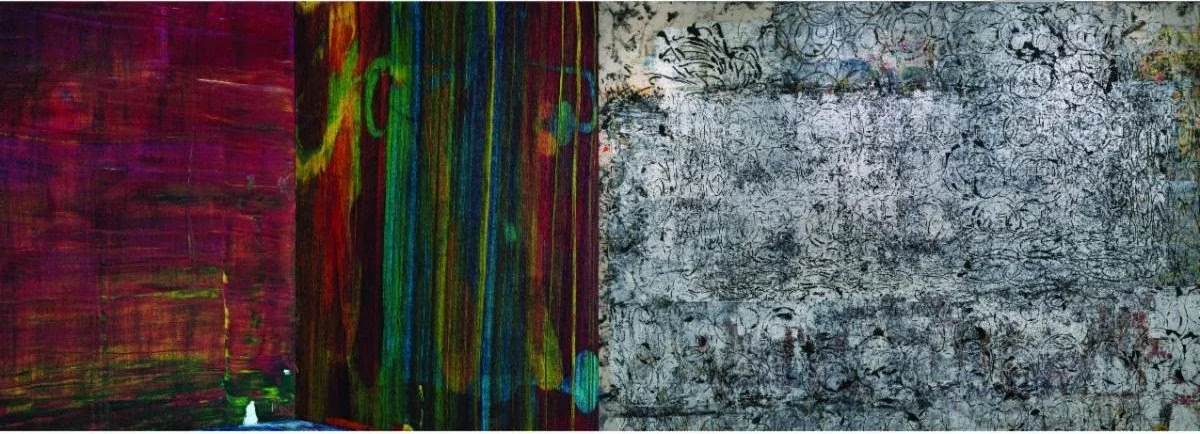

He recently tallied up his 2021 trash scorecard. Here is the breakdown:

Mylar balloons: 1,388.

Plastic bottles and aluminum cans: 1,349. He said year-end totals do not include old plastic bottles that have “become eggshell brittle and started the process of fragmenting. They go directly to trash.”

Plastic bottle caps: 1,209.

Latex balloons: 780. He said latex balloons are usually only the mouth piece, or ring piece, with attached ribbon. “I do find shredded pieces of latex too, but tally only the ring. Sometimes difficult to count when it may be a 30-plus mass of rings and tangled ribbon.”

Plastic straws: 328.

Spent plastic shotgun shells: 302.

Nips: 195.

Rubber gloves: 164.

Plastic and foam cups: 132. He said Dunkin’ Donuts (67) and Cumberland Farms (38) cups are the most common. “CF is still using foam cups and all found are foam. DD ceased using foam in 2020. Plenty of their paper cups were collected but are not in the tally.”

Golf balls: 119.

Plastic lids for plastic and foam cups: 104.

Plastic wads for shotgun shells: 86.

Plastic bags: 66.

Plastic cigarette lighters: 50.

Plastic K-cups: 45.

Since Dennis returned to Goosewing Beach 10 years ago to pick up Mylar balloons, there are 41,924 fewer pieces of litter along the Little Compton shoreline.

A trio of bills has been introduced during the current General Assembly session to address the Ocean State’s plastic pollution problem, including legislation to ban the sale of nips.

Frank Carini is senior reporter and co-founder of ecoRI News.

The Benjamin Family Environmental Center at the Goosewing Beach Preserve

The Sakonnet River as viewed from Portsmouth, R.I., looking south towards the ocean.

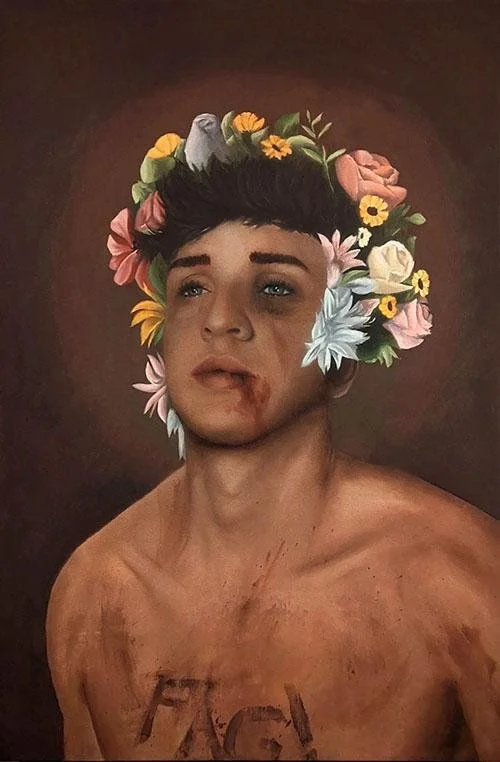

In spite of it all

“Gentle Fortitude’’ (oil on canvas), by Erik Carter, in the group show “Ardor,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, through Feb. 27. Mr. Carter is a Boston-based painter and virologist.

The gallery explains that the show is a collection of work by New England artists that reflects passion and zeal.

Media includes painting, mixed media, photography and drypoint.

Busy, busy, busy

“Gloucester Humoresque” (1923, oil on canvas), by William Meyerowitz (1896-1981) at the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass.

‘Magical mystery tour’

—Photo by Petar Milošević

“Criticizing Boston’s taxicabs is about as controversial as taking a stand against earthquakes, ax murderers, or the Third Reich….The drivers themselves are generally friendly but often topographically confused….No two rides are the same. No two taxis take you from Point A to Point B via Route C. And even if they do, the fares are somehow different. To enter a taxi in The Hub is to embark on a magical mystery tour of assorted mechanical surprises and geographic wonders.’’

— Nathan Cobb, in “Taxiing Toward a Fun City, in Cityside/Countryside (1980)

Maybe more reliable? Outside Boston’s Brutalist City Hall.

‘Glad of the burn’

“The Magpie,’’ by Claude Monet (1869)

Preston City Congregational Church

“I crouch down in blank

snow, glad of the burn

of cold air in the west,

the border of trees

black and still.’’

— From “Beginner’s Mind,’’ by Margaret Gibson (born 1944). She’s poet laureate of Connecticut and an emeritus professor at the University of Connecticut. She lives in Preston, Conn.

In the Hallville Mill Historic District, in Preston.

Information below is mostly an edited-down version of a Wikipedia entry on Preston.

“Properties in the district include 25 structures on a 50-acre site. The district includes the dam forming Hallville Pond (a mill pond — above), historic manufacturing buildings and worker housing, and the Hallville Mill Bridge, a lenticular pony truss bridge built circa 1890 by the Berlin Iron Bridge Co.

“The first mill there was built in 1752 for finishing locally produced homespun woolen cloth, with carding machines added in the early 19th Century.

“In 1857 Joseph Hall Sr., a weaver born in England, built an industrial-scale woolen mill on the site. The mill remained under his family's ownership under the name Hall Brothers' Woolen Mill (named for the founder's sons) and was expanded over the years. As of 1888 the mill employed 175 workers and produced 860,000 yards of cloth annually. The mill burned down in 1943, but manufacturing continued in Hallville until the 1960s and was a major source of employment and tax revenue for Preston.’’

It’s a classic small New England mill town. Sadly, the huge and sleazy Foxwoods casino is all too close, in Ledyard.

The joy of misdirection

Moose, Maine’s official state mammals, have bigger antlers than game wardens. Maine has more moose than any other state besides Alaska.

“Don’t ever ask directions of a Maine native….Somehow we think it funny to misdirect people and we don’t smile when we do it, but we laugh inwardly. It’s our nature.’’

— A Maine native, quoted by the novelist John Steinbeck (1902-1968), in his travel journal Travels with Charley (1962)

Hit this link for video!

xxx

“There are only two things that ever make the front page in Maine papers. One is a forest fire and the other is when a New Yorker shoots a moose instead of the game warden.’’

Actor/comedian/writer Groucho Marx (1890-1977) in a letter to Variety, Aug. 23, 1934

Llewellyn King: Trying to spread the innovation culture to old businesses

100, 300, and 500 Technology Square, in Cambridge, Mass., as seen from Main Street. The neighborhood has been the site of many technological breakthroughs for decades.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Microsoft is buying, subject to regulatory approval, Activision Blizzard for $69 billion. The Internet of Things is white-hot and likely to remain so.

If you want to whistle at that humongous sum for a company that makes games, you may have to add many octaves to the known musical scale.

Yes, high-tech is chasing trivia. The imperative at work here is if you don’t get your latest game into the market, someone else will. The threshold of entry is low and the rewards are astronomical.

If you are talking innovation and creativity, you are talking the Internet. That means that whole areas of society aren’t progressing as fast as they might and should. There is asymmetry.

The Internet firmament is driven not by market demand, but by a business dynamic that exists in the world of internet entrepreneurism: Innovate and create because the internet can create great wealth — and take it away, too.

Most non-Internet companies — and I talk to a fair number of CEOs — say that they are innovative and that they are innovation-driven but, in fact, they aren’t. Most companies don’t need to innovate the way the internet giants do. The metaverse is demonstrably an unstable place.

Most companies are looking for stability, for a plateau where they can manage what has been created while adding to it cautiously, often by acquisition. They confuse innovation with evolutionary improvement. The last thing they want is the kind of destructive innovation that characterizes Silicon Valley.

The febrile need to innovate in the Internet world is unique to that world. This because internet companies are all on a treacherous slope; failure can come as fast as success. Remember MySpace, Nokia, Palm, and Wang?

The Internet is global, and it is intrinsically favorable to monopoly. In the internet world, first past the post takes the prize money — all of it.

When you have market caps that value a company at $1 trillion, and all of that is dependent on the next innovation not overtaking you, you are going to throw money and talent at innovation because the alternative is known. Whenever possible, you are going to buy up your competition, hence the Microsoft purchase.

With all of the money, all of the glamor, all of the talent, there also is fear that some kid in a garage somewhere will invent the next big thing.

I submit that for the non-Internet world the business dynamic is very different. Most CEOs of public companies, snug in their C-suites and buttressed by huge salaries, are seeking a quiet place; a plateau where profits grow but there is some business serenity. For example, Boeing doesn’t want new airframes, it wants upgraded models.

They won’t admit to it, but many businesses long to be rent takers (known collectively as rentiers). They want a steady income with small risk.

Unfortunately, the business culture, including that spawned in business schools, aims to channel ambition into the rent-taking model. We have a business culture where ambition is channeled toward climbing to the top of the established order, not creating a new order.

There are many excellent minds managing established companies, often established many decades earlier, but there are few who yearn to create something wholly new.

The great names of management are many, but the great names of true innovation are few. Almost always, they have to break away from the established to create the new, to alter the world.

My friend Morgan O’Brien, the co-creator of Nextel, and now the executive chairman of the pioneering wireless company Anterix, is that kind of innovator who saw new horizons and went for them.

Today’s standout inventor is Elon Musk. He began as an Internet whiz with PayPal and has blazed the innovation trail like no other since Thomas Edison, more than a century earlier. He has changed the world underground with new concepts of subways, changed surface transportation by going electric, and changed space with his rockets.

Thirty years ago, I wrote that the weakness of U.S. companies is that they are happy to make silent movies when the talkies have been invented. Today, the established auto manufacturers are hell-bent to make electric pickup trucks now that new entrepreneurs are in the truck market with electric trucks. They never wanted to abandon the internal-combustion engine, just improve it a little at a time.

If the dynamic of the Internet and its constant innovation is missing in most American businesses, it needs to be grafted onto the business body politic. Must the Internet be behind every innovation of consequence? Ride-sharing and additive manufacturing (3D printing) are all computer-driven — software at work.

The challenge for the business culture is to harness ambition – it is never in short supply — and point it not toward the greasy pole of promotion, but toward the firmament of innovation.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

White House Chronicle

100, 300, and 500 Technology Square, in Cambridge, Mass., as seen from Main Street. The neighborhood has long been the site of many technological breakthroughs.

Microsoft is buying, subject to regulatory approval, Activision Blizzard for $69 billion. The Internet of Things is white-hot and likely to remain so.

If you want to whistle at that humongous sum for a company that makes games, you may have to add many octaves to the known musical scale.

Yes, high-tech is chasing trivia. The imperative at work here is if you don’t get your latest game into the market, someone else will. The threshold of entry is low and the rewards are astronomical.

If you are talking innovation and creativity, you are talking the internet. That means whole areas of society aren’t progressing as fast as they might and should. There is asymmetry.

The internet firmament is driven not by market demand, but by a business dynamic that exists in the world of internet entrepreneurism: Innovate and create because the internet can create great wealth — and take it away, too.

Most non-internet companies — and I talk to a fair number of CEOs — say they are innovative and that they are innovation-driven but, in fact, they aren’t. Most companies don’t need to innovate the way the internet giants do. The metaverse is demonstrably an unstable place.

Most companies are looking for stability, for a plateau where they can manage what has been created while adding to it cautiously, often by acquisition. They confuse innovation with evolutionary improvement. The last thing they want is the kind of destructive innovation that characterizes Silicon Valley.

The febrile need to innovate in the internet world is unique to that world. This because internet companies are all on a treacherous slope; failure can come as fast as success. Remember MySpace, Nokia, Palm, and Wang?

The internet is global, and it is intrinsically favorable to monopoly. In the internet world, first past the post takes the prize money — all of it.

When you have market caps that value a company at $1 trillion, and all of that is dependent on the next innovation not overtaking you, you are going to throw money and talent at innovation because the alternative is known. Whenever possible, you are going to buy up your competition, hence the Microsoft purchase.

With all of the money, all of the glamor, all of the talent, there also is fear that some kid in a garage somewhere will invent the next big thing.

I submit that for the non-internet world the business dynamic is very different. Most CEOs of public companies, snug in their C-suites and buttressed by huge salaries, are seeking a quiet place; a plateau where profits grow but there is some business serenity. For example, Boeing doesn’t want new airframes, it wants upgraded models.

They won’t admit to it, but many businesses long to be rent takers (known collectively as rentiers). They want a steady income with small risk.

Unfortunately, the business culture, including that spawned in business schools, aims to channel ambition into the rent-taking model. We have a business culture where ambition is channeled toward climbing to the top of the established order, not creating a new order.

There are many excellent minds managing established companies, often established many decades earlier, but there are few who yearn to create something wholly new.

The great names of management are many, but the great names of true innovation are few. Almost always, they have to break away from the established to create the new, to alter the world.

My friend Morgan O’Brien, the cocreator of Nextel, and now the executive chairman of the pioneering wireless company Anterix is that kind of innovator who saw new horizons and went for them.

Today’s standout inventor is Elon Musk. He began as an internet whiz with PayPal and has blazed the innovation trail like none other since Thomas Edison, more than a century earlier. He has changed the world underground with new concepts of subways, changed surface transportation by going electric, and changed space with his rockets.

Thirty years ago, I wrote the weakness of U.S. companies is that they are happy to make silent movies when the talkies have been invented. Today, the established auto manufacturers are hell-bent to make electric pickup trucks now that new entrepreneurs are in the truck market with electric trucks. They never wanted to abandon the internal combustion engine, just improve it a little at a time.

If the dynamic of the internet and its constant innovation is missing in most American businesses, it needs to be grafted onto the business body politic. Must the internet be behind every innovation of consequence? Ride-sharing and additive manufacturing (3D printing) are all computer-driven — software at work.

The challenge for the business culture is to harness ambition – it is never in short supply — and point it not toward the greasy pole of promotion, but toward the firmament of innovation.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of "White House Chronicle" on PBS.

Read this column on:

White House Chronicle

Inside Sources

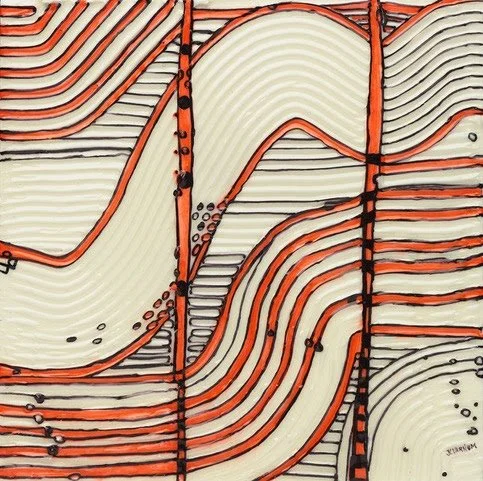

Celebration of contours

“Urban Form” (mixed media), by James C. Varnum, in his show “Contours of Change,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, March 4-27.

Galatea quotes him:

"In this exhibit … the pieces show my interpretation of changes in weather patterns and effects of climate disasters in our environments. I am influenced by the smoke maps of the world’s wildfires and by contemporary Australian Indigenous Art.

“These pieces are on cradled Claybord panels in mixed media. I create textures in acrylic molding paste, apply color and marks, then pour liquid acrylic over the work. When dry I apply more markings until the work is completed.

“I have always focused on the contours created by textures in my paintings, but these works are a change for me, from working on flat papers to creating on low-relief surfaces."

‘I celebrate plants’

“Weeds in Black” (encaustic), by Debra Claffey, who’s based in New Boston, a small town in southern New Hampshire. She’s a member of New England Wax (newenglandwax.com).

She says:

“My experience in horticulture and organic land care has led me to focus in on the plant world and the assaults on the soil, biodiversity of plant species, and the protection of native flora. I celebrate plants: their great age and history on the planet, their intelligence and successful adaptions, their beauty of form, shape, and infinite color. I marvel in our new knowledge of their ways of communication, of making themselves attractive to us and other species, and the trading of ‘goods and services’ that goes on between plants, fungi, bacteria, insects, birds, and even us mammals.’’

New Boston in 1875. Below is an edited version of the Wikipedia entry on the town, which was chartered in 1736.

“In 1820, the town had 25 sawmills, six grain mills, two clothing mills, two carding mills, two tanneries and a bark mill. It also had 14 schoolhouses and a tavern. The Great Village Fire of 1887, which started when a spark from a cooper's shop set a barn on fire, destroyed nearly 40 buildings in the lower village. In 1893, the railroad came to New Boston, and farm produce was sent by rail to city markets. Passenger service was discontinued in 1931, and the tracks were removed in 1935. Today the former grade is the multi-use New Boston Rail Trail.

“The town {along with the adjacent towns of Amherst and Mont Vernon} is home to the 2,800-acre New Boston Space Force Station, which started as an Army Air Corps bombing range in 1942. By 1960, it had become a U.S. Air Force base for tracking military satellites. In July 2021, the facility was given its current name and began operating as part of the United States Space Force. New Boston was also home to the Gravity Research Foundation from the late 1940s through the mid-1960s. Founder Roger Babson placed it in New Boston because he believed it safe from nuclear fallout should New York or Boston be attacked.’’

New Boston Space Force Station

David Warsh: Still the Free World in a second Cold War

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Since it arrived last summer, I have been reading, on and off, mostly in the evenings, The Free World: Art and Thought in the Cold War, by Louis Menand. It is a stupendous work, 18 chapters about criticism and performance, engagingly written and crammed with vivid detail. Most of it was new to me, since, while I am always interested in Thought, I don’t much follow the Arts. The book, in short, is readable, a 740- page article as from a fancy magazine. But then, Menand is a New Yorker staff writer, as well as a professor of English at Harvard University,

It is also a conundrum. The first chapter (“An Empty Sky,” is about George Kennan, a key architect of the policy of containment of the Soviet Union, its title taken from an capsule definition of realism by strategist Hans Morgenthau, in which nations after the war “meet under an empty sky from which the gods have departed”). The last chapter (”This is the End,”) is about America’s war in Vietnam (its title from the Raveonettes’ tribute to The Doors on the death of their vocalist, Jim Morrison).

In between are 16 other essays: on the post-WWII history of leftist politics, literature, jurisprudence, resistance, painting, literature, race and culture, photography, dance, popular music, consumer product design, literary criticism, new journalism and film criticism. My favorite is about how cultural anthropology displaced physical anthropology in the hands of Claude Lévi-Strauss and photographer Edward Steichen, organizer of the Museum of Modern Art’s wildly successful Family of Man exhibition in 1955

A preface begins, “This is a book about a time when the United States was actively engaged with the rest of the world,” meaning the 20 years after the end of the Second World War. Does that mean that Menand thinks the US ceased to be actively engaged with the world after 1965? The answer seems to be yes and no. When its Vietnam War finally ended, in 1975, he writes, “The United States grew wary of foreign commitments, and other countries grew wary of the United States.”

During those 20 years, says Menand, a profound rearrangement of American culture had taken place Before then, widespread skepticism existed among Americans about the place of arts and ideas in national life; respect for their government, its intentions and motives, was strong. After 1965, he finds, those attitudes were reversed. “The U.S. had lost political credibility, but it had moved from the periphery to the center of an increasing international artistic and intellectual life.” The change had come about through a policy of openness and exchange.

Artistic and philosophical choices carried implication for the way one wanted to live one’s life and for the kind of polity in which one wished to live in it. The Cold War changed the atmosphere. It raised the stakes.

Menand is right about the big picture, I think. Inarguably the U.S. grew much more free in those years, even as the governments of Russia and China cracked down on their citizens. Whether or not the lively arts were the engine – as opposed to the GI Bill, civil disobedience, the Pill, Ralph Nader, Rachel Carson, Jane Jacobs, the Stonewall Riots, The Whole Earth Catalog, Milton Friedman – hardly matters.

The Free World’s introduction begins with a photograph: Red Army soldiers hangs a Soviet flag from the roof of the Reichstag, overlooking the ruins of Berlin. The photo was a re-enactment, as had been that of U.S. Marines raising a flag atop Okinawa’s Mount Suribachi that had appeared in newspapers six weeks before.

But there was a difference: the Soviet photo been doctored, a second watch on the wrist of the flag-bearer needled away – unwelcome evidence, perhaps, of prior looting in the otherwise heroic scene. Cover-up was the hallmark of Russian totalitarianism, Menand seems to suggest: what the Cold War was all about.

Fast forward 30 years, to the end of the Vietnam War. The book ends with a striking peroration. Menand writes, “The political capital the nation accumulated by leading the alliance against fascism in the Second World War and helping rebuild Japan and Western Europe [the U.S.] burned through in Southeast.” The Vietnamese Communists who arrived in Saigon as the Americans left “did what totalitarian regimes do: they took over the schools and universities; they shut down the press; they pursued programs of enforced relocation’ they imprisoned, tortured, and execute their former enemies. Saigon was renamed Ho Chi Minh City and Ho’s body, like Lenin’s, was installed in a mausoleum for public viewing.”

Ahead lay another flight, this time Vietnamese citizens from their homeland. Menand continues, “Between 1975 and 1995, 839,228 Vietnamese fled the country, many on boats launched into the South China Sea [bound for Hong Kong or the Philippine Islands]. Two hundred thousands of them are estimated to have died [mostly by drowning]. Those people may or may not have known the meaning of the word ‘freedom,’ but they knew the meaning of oppression.” The English writer James Fenton, then working as a news correspondent, stayed behind to witness the aftermath of war. In the last sentence of his book, Menand quotes Fenton’s judgement: “The victory of the Vietnamese a victory for Stalinism.”

What, then, of the nearly years since the fall of Saigon, in 1975? The Chinese turn towards global markets after the death of Mao? The American resurgence as an economic hyperpower beginning in 1980? The collapse of the Soviet Union? NATO’s penning-in of Russia? The World Trade Organizations open-arms to China in 2000? The American invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq after 9/11? The divisions in U.S. civil society that have increased since?

The Winter Olympics in China underscore that a second Cold War has begun. What might be the consequences of it? How long will it last? How might it end? Who will turn out to be its Harry Truman? It’s George Kennan?

The distinction between a Free World and authoritarian regimes seems to hold up, though no longer do we think of the others as “totalitarian.” Britain’s reputation is diminished. Is the U.S. still leader of the Free World? Has its authority shrunk? I put Menand’s book back on the shelf thinking that it was a valuable contribution to work in progress.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, and proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran.

MIT’s ‘Superpedestrian’ startup growing in electric-scooter sector

Superpedestrian’s LINK scooters in Downtown Los Angeles.

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

BOSTON

“Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has begun gaining traction in the electric-scooter industry. This innovative technology startup named “Superpedestrian,” is unique in its pedestrian-defense features and AI software that can optimize safety and prevent riders from harming pedestrians on sidewalks.

“Assaf Biderman, founder of the MIT Senseable City Lab and founder/chief executive of “Superpedestrian,” is optimistic about his company’s position in the micromobility market. Competitors such as Lime and Byrd are following suit with similar technological innovations, but Biderman and his company remain confident in their product, stating that they hit “the holy grail of micromobility.”

“‘Superpedestrian’ scooters are available for rent under its ‘LINK’ service across the United States as well as in such European cities as Madrid and Rome, but with investors such as Antara Capital, the Sony Innovation Fund, Innovation Growth Ventures and FM Capita participating in Superpedestrian’s new funding round, the company intends to expand its services in 25 cities this year.

The New England Council applauds the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and its technology programs for paving the way towards pedestrian safety and technological innovation.

Samantha Garcia: We shouldn’t have to rely on National Guard for basic services

National Guard members perform multiple tasks at a COVID-19 test site at Rhode Island College in May 2020.

From OtherWords.org

As the highly transmissible Omicron variant continues to spread, hospitals across the country have reported critical staff shortages. In my home state of New Mexico, nearly half of all hospitals are understaffed, and more could be soon.

The U.S. health-care system has buckled under the strain of the pandemic. COVID-19 hospitalizations reached a peak in early January, nearly two years in. According to the American Hospital Association, “we’re facing a national emergency” as health care facilities simply don’t have enough workers to keep up with these surges.

With worker shortages now plaguing hospitals, nursing homes, and other long-term care facilities, states have turned to the National Guard for relief. So too have school districts, child-care facilities, and communities reeling from natural disasters.

Montgomery County, Md., for example, recently called on the Guard to fill in as public school-bus drivers. In fact, school district leaders in at least 11 states have turned to the Guard to shuttle students to school amid acute bus driver shortages.

New Mexico recently became the first state in the nation to recruit Guard troops to fill in as substitute teachers and day-care workers, but even that’s not meeting demand.

As schools struggle to stay open, some school administrators are covering custodial duties while parent volunteers fill in as cafeteria workers, classroom support, and COVID-19 testing aides. Even New Mexico Gov. Lujan Grisham is stepping into the classroom as a substitute.

Meanwhile, there’s the increasingly constant need for disaster response. Last year, Guard members were deployed across the West to support overstretched firefighting crews. And this past January, the Virginia Guard deployed members to support winter storm response.

According to the National Guard Bureau, more than 19,000 National Guard members are now mobilized across the country to support pandemic-related relief efforts. At other times, up to 47,000 have been deployed to meet pandemic demand.

“From the beginning of the pandemic, National Guard men and women in each of the 50 states, three territories, and the District of Columbia have been on the front lines,” said Army Gen. Daniel R. Hokanson, the Guard’s bureau chief. “We continue to work closely with the states to ensure” that we’re “meeting their needs.”

Certainly, National Guard members have stepped up heroically to serve their communities. But it’s worth asking: Why has the Guard become the “Swiss army knife” to meet states’ emergency needs?

To put it another way: Time and again, why is it only the military that has extra resources to go around? The simplest answer is we’ve spent decades ramping up our military spending while letting these other priorities stagnate.

For what taxpayers spent on military contractors alone last year, we could have instead provided health care for 25 million low-income adults and 38 million children. We could have funded over a million elementary school teachers. And we could have launched over a million clean-energy jobs — all with money to spare.

Instead communities are often left seeking help from the military to fill these roles.

Meanwhile, military spending is only going up. Congress recently passed a $778 billion military budget bill — a peacetime record.

All that spending is supposed to make us safer. But as critical public services reach their breaking point, it’s clear that short-changing our health, our children, and our planet has left us less safe.

As the pandemic and climate crisis are showing us, real security means divesting from excessive military spending and prioritizing the things we actually need to flourish — so maybe next time there won’t be a crisis.

Samantha Garcia is the New Mexico Fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies.

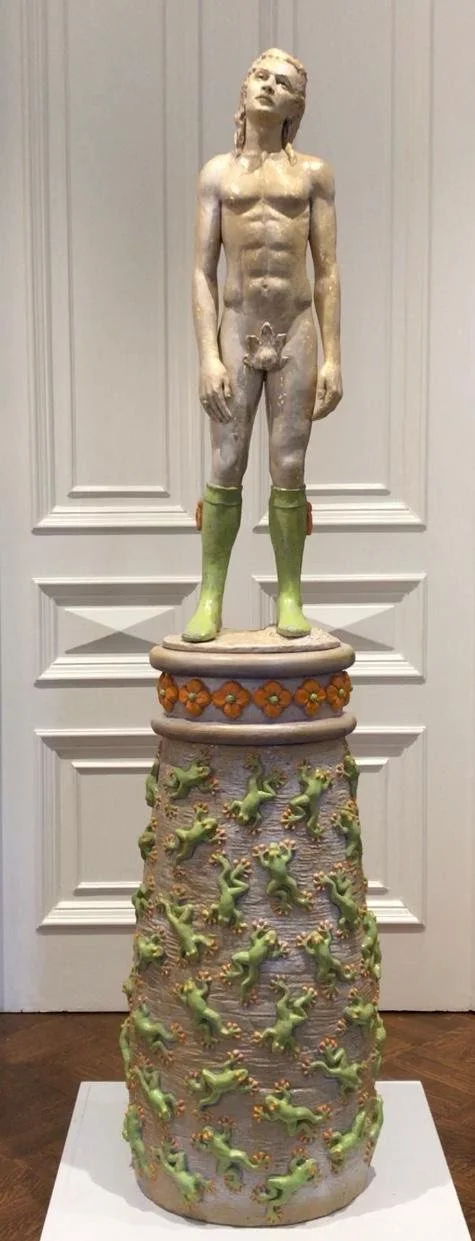

Nature crawls up

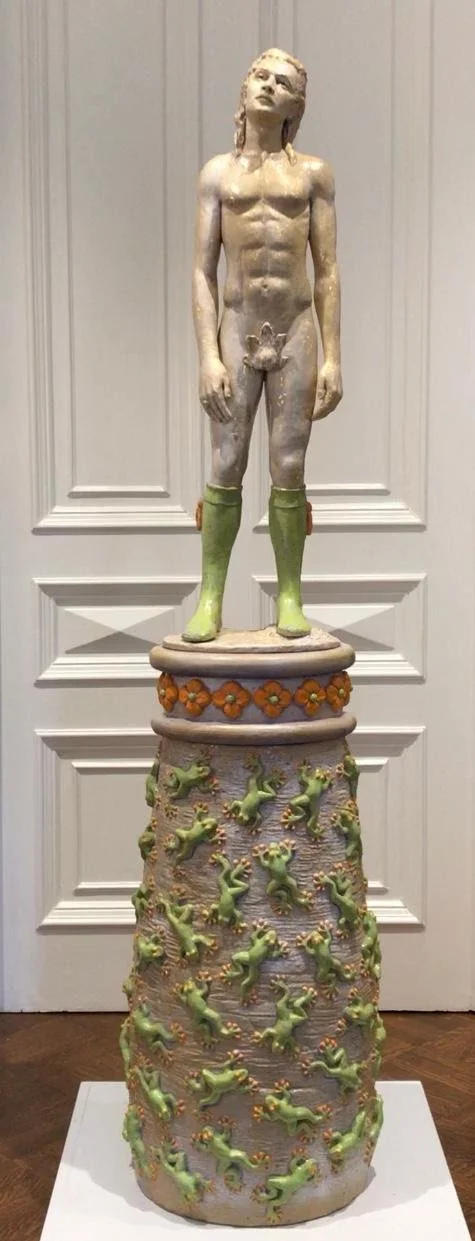

“Plague,’’ by Massachusetts artist Bruce Armitage, in the group show “Build and Lay Bare,’’ at Boston Sculptors Gallery, through Feb. 20.

The gallery says:

“Armitage’s playful yet foreboding ceramic sculpture depicts a classical figure atop a high plinth. Gazing upward, he is oblivious to the plague of colorful frogs ascending from below, laying bare humans’ neglect of nature.’’

Chris Powell: Conn. population gains don’t help if housing can’t keep up because of nimbyism

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Maybe all those people who in the last year or so have given up on New York City and its inner suburbs and moved to Connecticut are not so good for the state after all.

While they have offset the decline in population that Connecticut long has been suffering relative to the rest of the country, they also have driven up the state's housing prices and rents and have worsened its housing shortage. People who own their homes may be glad of their unrealized capital gains, but these gains come at huge expense to people who don't own their homes.

Average rents across the country are estimated to have risen 14 percent to nearly $1,900 a month last year, which should shock the many homeowners who can remember paying rents less than $500 when they were young. Of course housing price inflation has come amid enormous price increases in all other necessities, including food, energy, and medicine. Altogether lately inflation is running well above 10%, double the federal government's deceitful official figure.

This is what happens when the government hobbles the economy with ineffective epidemic restrictions and then pays people not to work, whereupon production of goods and services declines and prices rise still more. Inflation has far overtaken wage gains for ordinary people while enriching the already wealthy -- the owners of real estate and stocks, which soar with inflation.

Even three years ago, according to Harvard University's Joint Center for Housing Studies, a quarter of renters in the United States were paying more than half their income for housing. That burden for renters is surely far heavier now.

The virus epidemic and government's mistaken responses to it are the first cause of the worsening madness and despair in society -- the crime, drug abuse, and general hatefulness. But when it consumes half or more of people's income, the price of housing is a big part of what brings them to the end of their rope.

Since most people in Connecticut have adequate housing -- housing that they can afford and even achieve capital gains from -- the state is largely indifferent politically to the harm done by rising housing prices. A housing scandal in Danbury is receiving little attention outside the city, whose Zoning Commission is refusing to let a social-service organization, Pacific House, continue to operate a shelter for the homeless in a former motel building.

Pacific House would like to turn the building into what is called "supportive housing" -- housing that includes medical and rehabilitative services facilitating recovery for residents. But the commission wants none of it. The commission is ready to push these troubled people back out on the street -- in the winter, no less.

State government purchased the former motel for Pacific House's use, and without zoning approval the shelter is able to operate only because of one of Governor Lamont's emergency orders. Those orders are to expire in a week.

The General Assembly should extend the one applying to the Danbury shelter and demand some humanity from the city's Zoning Commission and the shelter's neighbors, who haven't been any more inconvenienced by the shelter than they were when the building was operated as a motel.

The cornerstone of the campaign of the likely Republican nominee for governor, Bob Stefanowski, is an effort to make Connecticut more affordable. That objective will resonate widely.

But most Republicans, who ordinarily celebrate property rights and an "ownership society," and most Democrats, who ordinarily pose as friends of the poor and struggling, are not enthusiastic about housing construction, at least not outside the already densely populated cities. No one wants more neighbors.

Even in the cities themselves, few people want greater population density and more facilities to help the troubled. Lately hundreds of New Haven residents have mobilized to block an addiction-treatment clinic in their neighborhood, though the city is full of people needing such treatment -- as are the suburbs.

Connecticut's state motto sometimes seems to be "Not in my backyard." But shunning problems doesn't solve them. It worsens them and makes them more expensive. More housing could make the state less expensive.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

The growing complications of admissions to elite colleges

Morgan Hall at Williams College, in Williamstown, Mass. The very prestigious college, founded in 1793, accepts less than 15 percent of applicants.

— Photo by Tim4403224246

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

What will highly selective colleges, of which New England has many, do to try to maintain student populations at least vaguely representative of the country and world if, as seems likely, the U.S. Supreme Court bans affirmative for racial minorities in admissions?

Should the Feds ban the consideration of race and ethnicity as part of a holistic evaluation of a student’s application? I’d rather leave that to the colleges’ judgment.

An example of an SAT "grid-in" math question and the correctly gridded answer.

The decision of many colleges to no longer require that applicants for admission take the SATs probably makes sense because, in part, of the increasingly unfair advantage that kids from affluent families have because their parents can afford to send them to such expensive SAT-preparation services as the Princeton Review.

I suppose something like SAT-prep services existed back in the mid-60’s when I was taking such tests but I didn’t hear of any then. My high school’s college-admissions chief, the red-faced, chain-smoking and stout Mr. Sullivan, simply announced that the next SATs would be on such and such date – always a Saturday in two weeks. He said: “Bring two {or was it three?} No. 2 pencils and try to get plenty of sleep the night before’’ (ensuring that we wouldn’t sleep well).

And now the kids will take the tests on their own laptops and tablets. Hmm…will this favor more affluent students with more digital experience and could it make cheating easier? And what about kids who may not even own a laptop or tablet?

‘Designed for EXCESS’

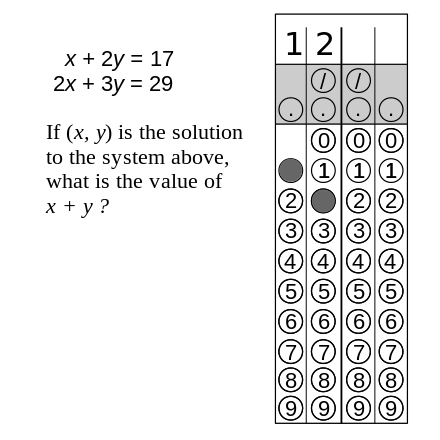

Left, Abelardo Morell’s “Paint #16” (photo). Right: Anthony Fisher’s “The Light of Day” (oil on canvas), in their joint show “Two of a Kind: Abelardo Morell and Anthony Fisher,” at the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth Art Gallery, at its Star Store Campus, in downtown New Bedford, Feb. 10-March 20.

The gallery says:

“This exhibition presents two creative approaches that focus on the abstract image – Abelardo Morell’s incredibly lush and sensual photographs of fresh paint frozen in time with the help of light, fast exposure and flash, and Anthony Fisher’s ingeniously captured lines and shapes featured on layered, monochromatic abstract paintings.

Both Morell and Fisher share a restless urgency to invent novel ways to play with traditional media, subjects, and methods. In their respective studios in the same creative community just outside of Boston, each pours his unique experimentation into their own patient and carefully crafted process. Results sometimes arrive as wonderful surprises transformed into bold work that the visitor can almost enter – inspiring, open minded, and deeply creative.’ Abelardo Morell admires Anthony’s work because he, ‘like me, thinks a lot about how a picture is made. Subject matter for him is, of course, important, but it is within his working process that the subject emerges. Anthony has used all sorts of devices to make marks on the canvas – perhaps to get his ego out of the way a bit.’

“Anthony Fisher’s studio process involves quirky and lumbering invented tools, physical struggle, gravity, chemistry, and physics to allow hundreds of marks to be thrown onto a canvas all at once. ‘My process is specifically designed for EXCESS – with so many visual ideas emerging at once, the overwhelmingly vast majority are discarded. I want the unexpected. My goal is to spark ideas that otherwise wouldn’t appear with a more deliberative, considered approach,’ says Fisher.’’

Abelardo Morell explains his admiration for the subject matter of his photographs, “When I visit museums, my eyes often take me first to the painting galleries. I marvel at the surfaces of paintings, which contain their own visual dramas, often independent of any narrative or formal aspect of the work. A difference between us as a photographer and painter is that photographers normally start with the world, while painters begin with a blank canvas and end up at times with astonishing creations.” Morell’s photographs show “that substance on its way to drying – a stage that finished paintings can never retain. “I also use other lighting sources pointed at a low angle to increase the raking light effects on the thick paint surface. I like the translucent and geometric visual marriages achieved through this method. Because what I am making are not ‘paintings’ in their own right, I am able to quote and crop discrete small paint details to make them play a big role in the final picture.”

Created specifically for this exhibition and presented at the gallery’s entrance is another visual surprise that underlines the connection between these two artists, neighbors and friends – a photograph of Abelardo Morell titled, “Paint: After Anthony Fisher’s 2021 Painting ‘Some Will Still Be Standing’, 2022” right next to the actual paintin

William Street, New Bedford, in the old “Whaling Capital’s’’ 19th Century section.

— Photo by PenitentWhaler