Evanescence on ice

Ice-fishing structures on Alton Bay in Lake Winnipesaukee, in New Hampshire.

“And there ain’t much to ice fishing till you miss a day or more

And the hole you cut freezes over

and it’s like you have never been there before.’’

— From “Ice Fishing,’’ a song by New Hampshire-based songwriter-singer Bill Morrissey (1951-2011)

From Marxism to the Burlington marketplace

Church Street Marketplace in Burlington

“‘People’s Republic

of Burlington,’ old Marxist

stronghold, now just a stage

on its way to high

capitalism. Church

Street commodified.

Out on the loop roads

of Montpelier, what does ‘strip

development’ strip? Grass

from pastures….”

— From “Hayden’s Shack I Can See to the End of Vermont,’’ by Neil Shepard (born 1951), a Johnson, Vt.-based poet

Tough but softening a bit in Boston

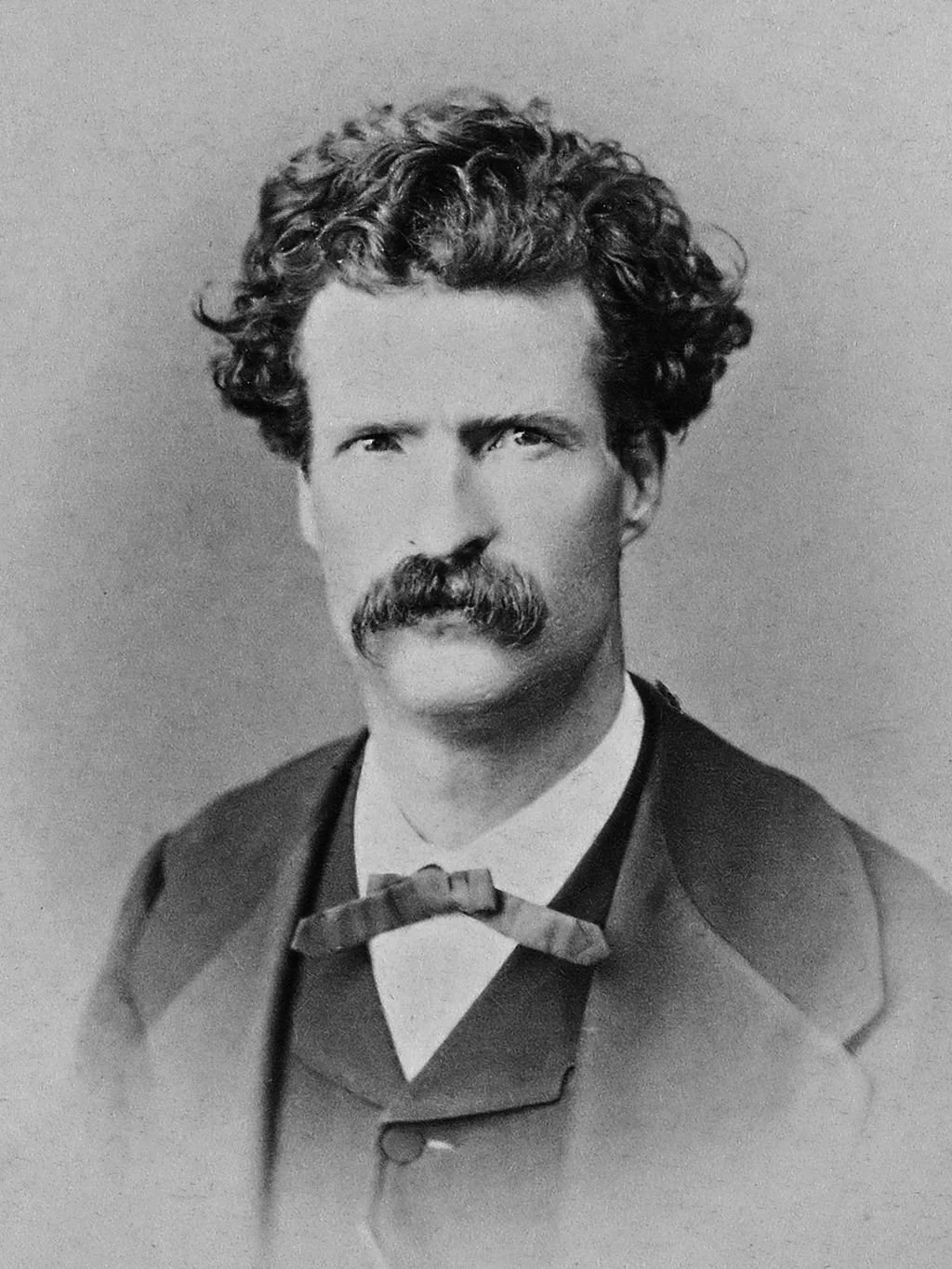

Mark Twain at age 31

“Tomorrow night I appear for the first time before a Boston audience - 4,000 critics”

— Mark Twain (1835-1910), in a Nov. 9, 1869 letter to his sister Pamela Clemens Moffat

xxx

“Boston’s upper zones

Are changing social habits

And I hear the Cohns

Are taking up the Cabots’’

— From Ira Gershwin’s lyrics for the 1931 song “Love Is Sweeping the Country,’’ with music by his brother George.

Jenny Gold: The emotional exhaustion from too many choices

Most all of us have felt the exhaustion of pandemic-era decision-making.

Should I travel to see an elderly relative? Can I see my friends and, if so, is inside OK? Mask or no mask? Test or no test? What day? Which brand? Is it safe to send my child to day care?

Questions that once felt trivial have come to bear the moral weight of a life-or-death choice. So it might help to know (as you’re tossing and turning over whether to cancel your non-refundable vacation) that your struggle has a name: decision fatigue.

In 2004, psychologist Barry Schwartz wrote an influential book called The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less. The basic premise is this: Whether picking your favorite ice cream or a new pair of sneakers or a family physician, choice can be a wonderful thing. But too many choices can leave us feeling paralyzed and less satisfied with our decisions in the long run.

And that’s just for the little things.

Faced with a stream of difficult choices about health and safety during a global pandemic, Schwartz suggests, we may experience a unique kind of burnout that could deeply affect our brains and our mental health.

Schwartz, an emeritus professor of psychology at Swarthmore College and a visiting professor at the Haas School of Business at the University of California-Berkeley, has been studying the interactions among psychology, morality, and economics for 50 years. He spoke with KHN’s Jenny Gold about the decision fatigue that so many Americans are feeling two years into the pandemic, and how we can cope. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: What is decision fatigue?

We all know that choice is good. That’s part of what it means to be an American. So, if choice is good, then more must be better. It turns out, that’s not true.

Imagine that when you go to the supermarket, not only do you have to choose among 200 kinds of cereal, but you have to choose among 150 kinds of crackers, 300 kinds of soup, 47 kinds of toothpaste, etc. If you really went on your shopping trip with the aim of getting the best of everything, you’d either die of starvation before you finished or die of fatigue. You can’t live your life that way.

When you overwhelm people with options, instead of liberating them, you paralyze them. They can’t pull the trigger. Or, if they do pull the trigger, they are less satisfied, because it’s so easy to imagine that some alternative that they didn’t choose would have been better than the one they did.

Q: How has the pandemic affected our ability to make decisions?

In the immediate aftermath of the pandemic, all the choices that we faced vanished. Restaurants weren’t open, so you didn’t have to decide what to order. Supermarkets weren’t open, or they were too dangerous, so you didn’t have to decide what to buy. All of a sudden your options were restricted.

But, as things eased up, you sort of go back to some version of your previous life, except [with] a whole new set of problems that none of us thought about before.

And the kinds of decisions you’re talking about are extremely high-stakes decisions. Should I see my parents for the holidays and put them at risk? Should I let my kid go to school? Should I have gatherings with friends outside and shiver, or am I willing to risk sitting inside? These are not decisions we’ve had practice with. And having made this decision on Tuesday, you’re faced with it again on Thursday. And, for all you know, everything has changed between Tuesday and Thursday. I think this has created a world that is just impossible for us to negotiate. I don’t know that it’s possible to go to bed with a settled mind.

Q: Can you explain what’s going on in our brains?

When we make choices, we are exercising a muscle. And just as in the gym, when you do reps with weights, your muscles get tired. When this choice-making muscle gets tired, we basically can’t do it anymore.

Q: We’ve heard a lot about more people feeling depressed and anxious during the pandemic. Do you think that decision fatigue is exacerbating mental health issues?

I don’t think that you need decision fatigue to explain the explosion of mental-health problems. But it puts an additional burden on people.

Imagine that you decided that, starting tomorrow, you are going to be thoughtful about every decision you make. OK, you wake up in the morning: Should I get out of bed? Or should I stay in bed for another 15 minutes? Should I brush my teeth, or skip brushing my teeth? Should I get dressed now, or should I get dressed after I’ve had my coffee?

What the pandemic did for a lot of people is to take routine decisions and make them non-routine. And that puts a kind of pressure on us that accumulates over the course of the day, and then here comes tomorrow, and you’re faced with them all again. I don’t see how it could possibly not contribute to stress and anxiety and depression.

Q: As the pandemic wears on, are we getting better at making these decisions? Or does the compounded exhaustion make us worse at gauging the options?

There are two possibilities. One is that we are strengthening our decision-making muscles, which means that we can tolerate more decisions in the course of a day than we used to. Another possibility is that we just adapt to the state of stress and anxiety, and we’re making all kinds of bad decisions.

In principle, it ought to be the case that when you’re confronted with a dramatically new situation, you learn how to make better decisions than you were able to make when it all started. And I don’t doubt that’s true of some people. But I also doubt that it’s true in general, that people are making better decisions than they were when it started.

Q: So what can people do to avoid burnout?

First, simplify your life and follow some rules. And the rules don’t have to be perfect. [For example:] “I am not going to eat indoors in a restaurant, period.” You will miss out on opportunities that might have been quite pleasant, but you’ve taken one decision off the table. And you can do that with respect to a lot of things the way that, when we do our grocery shopping, we buy Cheerios every week. You know, I’m going to think about a lot of the things I buy at the grocery, but I’m not going to think about breakfast.

The second thing you can do is to stop asking yourself, “What’s the best thing I can do?” Instead, ask yourself, “What’s a good enough thing I can do?” What option will lead to good enough results most of the time? I think that takes an enormous amount of pressure off. There’s no guarantee that you won’t make mistakes. We live in an uncertain world. But it’s a lot easier to find good enough than it is to find best.

Jenny Gold is a Kaiser Health News reporter

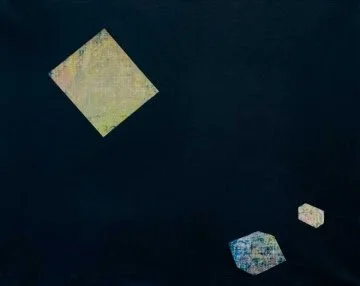

‘Spatial painting’

“Three Boxes” (oil on canvas), by Don Smith, in his show “Space, Intuition, and Expression”, at Bannister Gallery, Providence, through Feb. 11. It’s only on view in person for Rhode Island College faculty and students but can be seen online.

The gallery says: “The show features a variety of different painting techniques, including the method Smith calls ‘Spatial.’

"The Spatial pieces are arrived at through a complicated format of drawing, usually done from life. Once the drawing is in place, Smith begins to paint over areas he feels to be extraneous, leaving various shapes or forms to which he assigns a particular color value."

Mr. Smith lives and works in Johnston, R.I., a Providence suburb.

Clemence Irons House in Johnston, built in 1691

‘Thaw through frost’

— Photo by Scoo

“Home drive. High beams shearing the bromegrass,

blackcaps, brambles by the roadside;

red stems siphon frozen ground

grown soft, a bruise beneath the smooth suede

winter peach that rolls across

the dashboard. Thaw through frost….

…Mount Equinox, Ascutney …far ahead….’’

— From “Driving Sleeping People,’’ by Richard Kenney, who has lived in western Vermont and teaches at the University of Washington.

Mount Ascutney, in eastern Vermont

Boston Children’s to buy Franciscan in bid to improve mental-health care

Boston Children’s Hospital

Via The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

“Boston Children’s Hospital plans to acquire Franciscan Children’s {hospital}, in Boston’s Brighton section. Through this acquisition, Boston Children’s Hospital hopes to improve its response time for children who are awaiting psychiatric treatment and expand the mental-health resources available to its patients.

“As the coronavirus pandemic persists, there has been a significant uptick in the number of patients receiving or waiting for inpatient psychiatric care at Boston Children’s Hospital. By joining forces, Boston Children’s Hospital can increase and diversify its mental-health resources offered to patients, expanding into services such as treatments for those with psychiatric disorders and developmental disorders. This acquisition would also allow for Boston Children’s hospital to better manage the increase in patients who seek treatment.

“Dr. James Mandell, chairman of the Franciscan Children’s board, recognizes that this plan would be mutually beneficial, as the acquisition would provide Franciscan Children’s with the opportunity to ‘better train and recruit staff,’ and ‘provide access to more patients.’’’

But where to? Spring?

“Follow Me” (dye sublimation print on aluminum), by Irene Mamiye, at Lanoue Gallery, Boston

Lost and found in the mountains

Mt. Washington from Intervale, N.H.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I was wandering around in the Internet the other night and came across a 1941 movie called Sun Valley Serenade, a musical film set in the Idaho ski resort of the same name. Seeing it took me back to February 1971, when I watched the film in a hotel room in Jackson, N.H. I was up there covering, (for The Boston Herald Traveler) the search for a couple of guys lost or dead just up the road, on Mt. Washington. The search was being run out of the Appalachian Mountain Club’s Pinkham Notch facility.

For three days, about a dozen of us journalists (including from such national media such as Time magazine) hung around as rescuers from the National Forest Service looked for these guys. They eventually found them safe in a shelter somewhere near the tree line. But the authorities were very angry that such inexperienced climbers had jeopardized the rescuers on that infamously stormy mountain. (I’ve climbed it myself twice in the winter with an experienced team. It’s a beautiful spectacle.)

“Do those little bastards know how much this is costing?’’ griped one of rescuers.

Of course, we journos were bored much of the time, but some of us snuck away for cheery drinks and dinner in Jackson, hoping that nothing exciting would happen while we were enjoying ourselves.

But what I most remember from that trip, one of many crazy expeditions during my time at The Herald Traveler, was sitting in my hotel room as wet snow fell outside watching Sun Valley Serenade on the TV and, particularly, listening to the song “I Know Why’’ being sung while backed by the Glenn Miller Orchestra. One of the lines is “Even though it’s snowing, violets are growing.’’

Corny but it brings a pang about the passage of time

I probably have yellowed clips of my stories of the lost climbers in the cellar, but I’d bring on an asthma attack looking for them. In those deep, dark, pre-Internet days you’d need clips to get your next newspaper job, if you were foolish enough to want one.

Amazon octopus keep stretching out its arms

Goodyear Metallic Rubber Shoe Company and downtown Naugatuck (c. 1890). The many industrial firms in Naugatuck and Waterbury in the communities’ industrial heyday, from the mid-19th Century through the 1960’s, dumped toxic waste into the Naugatuck River, much of which eventually flowed into Long Island Sound.

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com):

“Amazon plans to develop a new distribution facility in New Haven County, Conn….Bluewater Property Group, a developer from Pennsylvania, has begun taking steps to create a tremendous Amazon distribution facility on the border of Waterbury and Naugatuck.

“Though the development is far from completion and is awaiting approval, residents of Waterbury and Naugatuck and members of the Connecticut (congressional) delegation are optimistic about the prosperity that this facility would bring to the county, and even the state.

“‘It has the potential to create up to 1,000 new jobs and go a long way in supporting these communities in their broader revitalization efforts,’ stated Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont. U.S. Rep. Jahana Hayes shared in this assertion, stating that this influx of jobs would benefit the middle class and the blue-collar workers in the area.’’

Specimens of New Hampshire

The New Hampshire State House, built between 1816 and 1819 and designed by architect Stuart Park.

The building was built in the Greek Revival style with smooth granite (natch!) blocks.

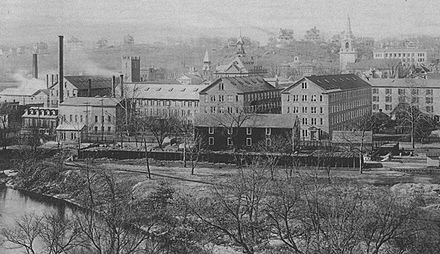

1922 map of New Hampshire published in the bulletin of the Brown {paper} Company in Berlin, N.H.

“I like your nickname, ‘The Granite State.’ It shows the strength of character, firmness of principle and restraint that have characterized New Hampshire.’’

President Gerald R. Ford, in a speech in Concord, New Hampshire’s capital, on April 17, 1975

xxx

“Just specimens is all New Hampshire has,

One each of everything as in a show-case

Which naturally she doesn't care to sell.’’

— From the 1923 poem “New Hampshire,’’ by Robert Frost

The lilac is New Hampshire’s state flower.

Wear lead

“Irradiate” (mixed media), by Mary Marley, in the group show “Space for Maybe,’’ at Fountain Street Gallery, Boston, through Feb. 13. She is based in Millis, Mass., once known as the home of some manufacturers during New England’s mill-town heyday and now to a large extent a Greater Boston commuters’ suburb.

‘The illusiveness of time’

Painting by Alexis Serio in her show “Time and Memory,’’ at Edgewater Gallery at the {Otter Creek} Falls, Middlebury, Vt., through March 31.

She calls her show “stories of beauty that I wish to share with the viewer”.

“My paintings are philosophical and formal investigations about the visual perception of light and color, the personal experience of remembering and inventing, and the natural illusiveness of time."

The gallery says:

“The viewer recognizes these as landscapes. Serio gives us a horizon line as a foothold for this but beyond this reference the compositions are investigations of color and shape, rhythmically layered to represent perceptions of light, land, and memories.’’

Otter Creek Falls, in Middlebury

Lithograph of Middlebury from 1886 by L.R. Burleigh with list of landmarks

Llewellyn King: Utilities urgently need to add transmission

In Seekonk, Mass., during the height of the Jan. 29 blizzard. Many people in southeastern Massachusetts lost power in the storm, in which winds gusted to hurricane force.

Logo of Independent System Operator, which oversees the region’s electric grid.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

It has become second nature. You hear that bad weather is coming and rush to the store to stock up on bottled water and canned and other non-perishable foods. You check your flashlight batteries.

For a few days, we are all survivalists. Why? Because we are resigned to the idea that bad weather equates with a loss of electrical power.

What happens is the fortunate have emergency generators hooked up to their freestanding houses. The rest of us just hope for the best, but with real fear of days without heat.

It happened most severely in Texas in February 2021; during Winter Storm Uri, which lasted five days, 250 people died. Recently, during the Blizzard of 2022, on Jan. 28-29, 100,000 people in Massachusetts endured bitter cold nights when the electricity failed. There were more power failures in the most recent ice storm.

There are 3,000 electric utilities in the United States. Sixty large ones, like Consolidated Edison, NextEra Energy, Pacific Gas and Electric, and the Tennessee Valley Authority, supply 70 percent of the nation’s electricity. Nonetheless, the rest are critical in their communities.

All utilities, large and small, have much in common: They are all under pressure to replace coal and natural gas generation with renewables, which means solar and wind. No new, big hydro is planned, and nuclear is losing market share as plants go out of service because they are too expensive to operate.

The word the utilities like to use is resilience. It means that they will do their best to keep the lights on and to restore power as fast as possible if they fail due to bad weather. When those events threaten, the utilities spring into action, dispatching crews to each other’s trouble spots as though they were ordering up the cavalry. The utilities have become very proactive, but if storms are severe, it often isn’t enough.

Now, besides more frequent severe weather events, utilities face the possibility of destabilization on another front, due to switching to renewables before new storage and battery technology is available or deployed.

The first step to avoid new instability -- and it is a critical one -- is to add transmission. This would move electricity from where it is generated in wind corridors and sun-drenched states to where the demand is, often in a different time zone.

Duane Highley, president and CEO of Tri-State Generation and Transmission Association, which serves four states in the West from its base in Westminster, Colo., says new west-east and east-west transmission is critical to take the power from the resource-rich Intermountain states to the population centers in the East and to California.

“Most existing transmission lines run north to south. They aren’t getting the renewables to the load centers,” Highley says.

Echoing this theme, Alice Moy-Gonzalez, senior vice president of strategic development at Anterix, a communications company providing broadband private networks that make the grid more secure and efficient, sees pressure on the grid from renewables and from new customer demands (such as electrical vehicles) as electrification spreads throughout society.

“The use of advanced secure communications to monitor all of these resources and coordinate their operation will be key to maintaining reliability and optimization as we modernize the grid,” Moy-Gonzalez says.

Better communications are one step in the way forward, but new lines are at the heart of the solution.

The Biden administration, as part of its infrastructure plan, has singled out the grid for special attention under the rubric “Build a Better Grid.” It has also earmarked $20 billion of already appropriated funds to get the ball rolling.

Industry lobbyists in Washington say they have the outlines of the Department of Energy plan, but details are slow to emerge. Considered particularly critical is the administration’s commitment to ease and coordinate siting obstacles with the states and affected communities.

Utilities are challenged to increase the resilience of the grid they have and to expand it before it becomes more unstable.

Clint Vince, who heads the U.S. energy practice at Dentons, the world’s largest law firm, says, “We aren’t going to reach the growth in renewables needed to address climate without exponential growth in major interstate transmission. And sadly, we won’t succeed with that goal on our current trajectory. We will need significant federal intervention because collaboration among the states simply hasn’t been working within the timeframe needed.”

Better keep the flashlights handy.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington., D.C.

Linda Gasparello

Co-host and Producer

"White House Chronicle" on PBS

Mobile: (202) 441-2703

Website: whchronicle.com

Stephen J. Nelson: Of visionary John Kemeny and decades of court battles over affirmative action at colleges

John G. Kemeny (1926-1992), Hungarian-born mathematician, computer scientist and president of Dartmouth College in 1970-1981

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

The U.S. Supreme Court is taking up affirmative action at colleges and universities for the sixth time in 50 years. In that litany, an early case was the University of California vs. Bakke. Bakke complained about being denied admission to the university’s medical school because seats were guaranteed for minority applicants, thus barring the door to him and other white applicants.

When the Bakke case was on the court’s docket, John Kemeny was president of Dartmouth College, in Hanover, N.H. The Dartmouth board of trustees wanted a public statement by the college on Bakke. Given their strong confidence in Kemeny, they gave him sole authority to craft Dartmouth’s stand on affirmative action. Kemeny’s voice from his bully pulpit into the public square about the Bakke case echoes today.

Kemeny’s argument displays ahead-of-the-curve insights. His major concern, one still very much at stake in the outcome of the court’s deliberations today, was that colleges had to be able to maintain their fundamental purposes in the face of any court judgment. Should the court mandate a cookie-cutter approach for college admissions, the unintended consequence would be to reduce diversity among institutions of higher education something that Kemeny said simply would be “highly undesirable.”

Using Dartmouth’s example, Kemeny underscored that the board had affirmed the college’s purpose as “the education of men and women with a high potential for making a significant positive impact on society.”

The board did not define that purpose as “the education of students who have the ability to accumulate high grade-point averages at the College,” a statement that would be “ludicrous!”

Kemeny pushed back against the court going over the edge if it were to compel colleges and universities exclusively to use test scores and presumed objective measures to decide which students to admit. That legal edict would restrict colleges from recruiting and admitting musicians, athletes and any student uniquely qualified to contribute to a student body and a college. Quotas of any sort were in his judgment “abhorrent.” Beware what you wish for.

Years after Bakke, in the 2003 University of Michigan cases, Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor asserted that colleges had roughly 25 more years to solve their equity and equal-opportunity problems. After that time, reliance on affirmative-action policies would run out. O’Conner’s clock continues to tick.

Getting to where she urged has proved difficult. Progress on the diversity front in the Ivory Tower is glacial and complicated because competing interests must be addressed and give their blessing or at least not actively resist new programs and initiatives. More time than O’Conner predicted is clearly needed. Ideological players on all sides agree that substantive changes in fairness and equity is the arrival point, though there will always be huge differences about the roadmap.

Greater diversity at colleges and universities makes their campus communities more engaging, more demanding, more rewarding and their members more fully educated. Absent diversity, the highest values of what we want a college education to be will remain outside our grasp. That is true for our body politic inside and outside the gates as graduates take their places in the social of communities and the nation. This picture is the goal, but how to get there and how long it will take are the great unknowns.

The new challenge brought by Students for Fair Admissions alleges that Harvard University discriminates against Asian-American students and the University of North Carolina discriminates against white and Asian- American applicants by continuing the use of race as an upfront criteria in admissions rather than observing a race-blind approach that would place more credence and consideration on an applicant’s struggles with discrimination in their life experiences.

The Supreme Court, of course, relies on arguments. The presidents of our colleges and universities must as a group get in the arena, present their case and gather defenders in amicus briefs. The cards will fall as the court dictates. However, jousting over what the Justices will say has to be embraced. It must be made clear to the court’s justices that they must not do harm to hard-fought policies designed to make our colleges and universities equitable, fair and open to diverse populations. Confining latitude and judgments about the scope of admissions procedures and aspirations to add greater diversity to their student bodies would rob colleges and universities of the very autonomy and freedom in their affairs that makes us the envy of the world. The shape of the future of diversity at our colleges is at stake and college presidents must weigh in with all the authority they can muster.

The voices of college presidents have to be front and center in this debate and in the court’s verdict. John Kemeny’s wisdom is a mantle that today’s presidents and those of us concerned diversity and equal opportunity on our campus must take up.

Stephen J. Nelson is professor of educational leadership at Bridgewater State University and senior scholar with the Leadership Alliance at Brown University. He is the author of the recently released book, John G. Kemeny and Dartmouth College: The Man, the Times, and the College Presidency. He has written several NEJHE pieces on the college presidency.

Chris Powell: Mocking the law and getting little integration

In Constitution Plaza in downtown Hartford

MANCHESTER, Conn.

What has Connecticut gotten for the 33 years of litigation in the Hartford school-integration case of Sheff v. O'Neill, which purportedly ended last week with a settlement between the plaintiffs and state government?

The first result of the Sheff business is a mockery of state constitutional law and the courts themselves.

The state Supreme Court's 4-3 decision in the Sheff case in 1996 proclaimed that every public school student in the state -- not just students in Hartford -- has a state constitutional right to a racially integrated education. That conclusion was not only dubious law -- it was torn to shreds by the brilliant dissent of Justice David M. Borden -- but also impossible to achieve as a practical matter, since it would have required the assignment to school by their race of tens of thousands of students across the state, which federal courts would have forbidden as federally unconstitutional.

Even the Sheff plaintiffs knew that comprehensive racial integration was impossible and they never pressed for it. They were concerned only about Hartford, where the school population consisted overwhelmingly of impoverished, fatherless, and neglected minority children whose educational performance was miserable.

While the state Supreme Court's proclamation of a constitutional right stands, 26 years later it is being violated in most towns and there is and will be no effort to enforce it.

So much for constitutional law in Connecticut.

The second result of the Sheff case is the continued de-facto racial segregation of the Hartford schools themselves.

Because of the state's creation of Hartford-area "magnet" or regional schools that draw both city and suburban students, the city's schools are less segregated than they were. But still about 60 percent of Hartford students are enrolled in schools considered segregated. Similarly, most suburban and rural schools in the state remain segregated too, overwhelmingly white.

Connecticut's huge and long-lamented racial-achievement gap between white and minority students endures in both the Hartford area and the state generally. And while the integration produced by the regional schools may have good results over the long term as students gain more diverse friends and acquaintances, the regional schools have had a negative effect as well.

That is, the regional schools drain Hartford's neighborhood schools of their more-parented students, leaving the neighborhood schools with even more disadvantaged populations. While the regional schools are advocated for mixing disadvantaged minority city students with middle-class suburban students who may provide better examples academically, this comes at the expense of neighborhood schools that lose their own better examples.

Even so, the Sheff settlement has state government promising still more regional schools and school-choice programs -- more openings for city students in suburban schools -- until there is room for every Hartford student who wants to escape a neighborhood school.

Maybe then it will be possible to acknowledge the underlying problem officially -- the most neglected kids, the core of the unassimilable urban poverty that long has driven the white flight to the suburbs and now is driving the minority middle class out of the cities as well.

In recent years state government is estimated to have spent hundreds of millions of dollars on regional schools in the Hartford area and the complicated transportation arrangements they require. The integration this has produced is so small as to invite questions as to whether other approaches might be more productive and cheaper.

Poverty may be a virtue in religious orders but it is a curse in society, since the poor don't pull their own weight. So suburban fear of housing for the poor is fair, and such housing is difficult to develop in the suburbs even as state law purports to require it in the towns with the most exclusive zoning.

So maybe once regional schools and choice programs have drained Hartford and the state's other troubled cities of their most-parented students a decade or two from now, government in Connecticut will be compelled to examine the neglected children who remain and to inquire into what has made them so poor. If it is honest, such an inquiry will begin with government itself.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

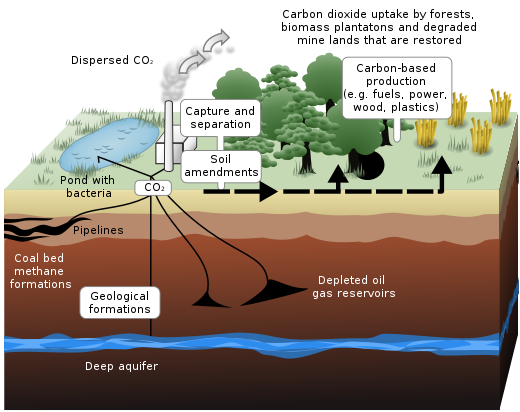

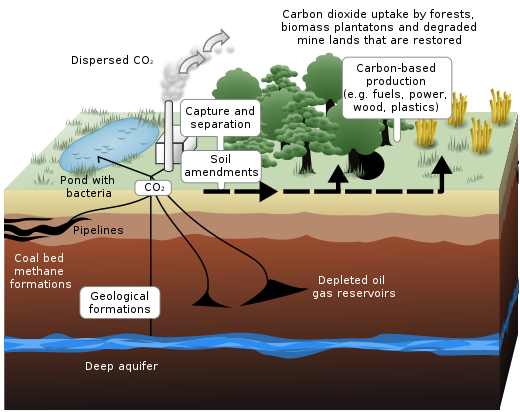

Southwest Airlines’ $10 million pledge to Yale to research natural carbon capture

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

“Southwest Airlines, announced a $10 million commitment to New Haven-based Yale University’s Center for Natural Carbon Capture (YCNCC) to research technological advancements and find new solutions to reduce net greenhouse-gas emissions.

“The pledge will also support research and educational efforts at the Yale School of the Environment to explore the current state of sustainability, strategy, policy, and economics, emphasizing trends related to the aviation industry and focusing on finding new ways to reduce atmospheric carbon. Established in March 2021, YCNCC is focused on strategies for removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and safely storing it within plants, soils, rocks, and oceans. It also aims to develop methods for industrial carbon capture to convert carbon dioxide into useful fuels, plastics, and building materials.

“‘This innovative partnership gives Southwest the opportunity to support the development of crucial science to combat climate change, including fostering innovative research aimed at informing and advancing efforts to reduce atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations,’ said Stacy Malphurs, vice president of supply chain management & environmental sustainability for Southwest Airlines. We recognize the importance of supporting initiatives that take a holistic approach to de-carbonization in the long-term, which aligns with the U.S. government’s goal for the aviation industry to be carbon neutral by 2050.’

‘Migrant to nomad’

From the show“The Levitating Perils” (video installation), by Frank Wang Yefeng, at the Chazan Gallery at Wheeler, Providence, Feb. 10-March 2

The gallery says that the mixed-media artist's works often relate to the experience of being a Chinese immigrant in the United States. He “left his place of origin at a young age, the memory from a migrant to a nomad has led him to investigate the transformation of emotions, autonomous objects of continuous movements, and the in-between states of nomadic subjects that occur in both virtual and physical realms."

Glass nips better

A collector's cabinet full of miniature bottles

— Photo by kerinin

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Rhode Island state legislators are considering banning those plastic nip liquor bottles of which you see all too many along roads, sidewalks and on beaches.

Good idea. They’ve added to the plastic pollution you see everywhere and that’s bad for wildlife as well as aesthetics (and thus tourism). That’s in part because all too many of the people who buy them are slobs and/or drunk.

And the smallness of the nip bottles discourages reuse.

If only more people demanded glass containers, which can be used indefinitely. And even if slobs dropped them in the water or on, say, a beach, they gradually wear down from the abrasion from sand, etc., and can become quite beautiful Anyone remember collecting “sea glass” (aks “beach glass”) as a kid?

Will someone some day finally invent a plastic that degrades rapidly with no harm to the environment?

“Sea glass’’