Amazon octopus keep stretching out its arms

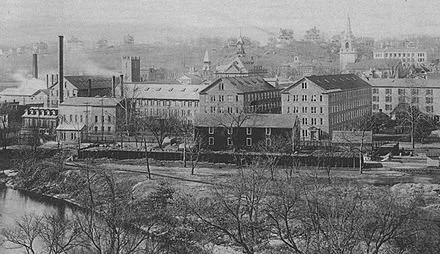

Goodyear Metallic Rubber Shoe Company and downtown Naugatuck (c. 1890). The many industrial firms in Naugatuck and Waterbury in the communities’ industrial heyday, from the mid-19th Century through the 1960’s, dumped toxic waste into the Naugatuck River, much of which eventually flowed into Long Island Sound.

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com):

“Amazon plans to develop a new distribution facility in New Haven County, Conn….Bluewater Property Group, a developer from Pennsylvania, has begun taking steps to create a tremendous Amazon distribution facility on the border of Waterbury and Naugatuck.

“Though the development is far from completion and is awaiting approval, residents of Waterbury and Naugatuck and members of the Connecticut (congressional) delegation are optimistic about the prosperity that this facility would bring to the county, and even the state.

“‘It has the potential to create up to 1,000 new jobs and go a long way in supporting these communities in their broader revitalization efforts,’ stated Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont. U.S. Rep. Jahana Hayes shared in this assertion, stating that this influx of jobs would benefit the middle class and the blue-collar workers in the area.’’

Specimens of New Hampshire

The New Hampshire State House, built between 1816 and 1819 and designed by architect Stuart Park.

The building was built in the Greek Revival style with smooth granite (natch!) blocks.

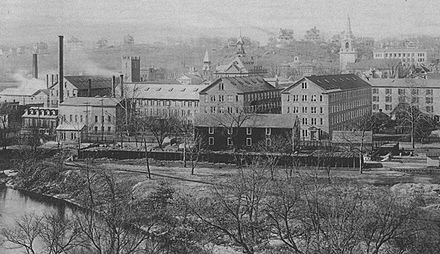

1922 map of New Hampshire published in the bulletin of the Brown {paper} Company in Berlin, N.H.

“I like your nickname, ‘The Granite State.’ It shows the strength of character, firmness of principle and restraint that have characterized New Hampshire.’’

President Gerald R. Ford, in a speech in Concord, New Hampshire’s capital, on April 17, 1975

xxx

“Just specimens is all New Hampshire has,

One each of everything as in a show-case

Which naturally she doesn't care to sell.’’

— From the 1923 poem “New Hampshire,’’ by Robert Frost

The lilac is New Hampshire’s state flower.

Wear lead

“Irradiate” (mixed media), by Mary Marley, in the group show “Space for Maybe,’’ at Fountain Street Gallery, Boston, through Feb. 13. She is based in Millis, Mass., once known as the home of some manufacturers during New England’s mill-town heyday and now to a large extent a Greater Boston commuters’ suburb.

‘The illusiveness of time’

Painting by Alexis Serio in her show “Time and Memory,’’ at Edgewater Gallery at the {Otter Creek} Falls, Middlebury, Vt., through March 31.

She calls her show “stories of beauty that I wish to share with the viewer”.

“My paintings are philosophical and formal investigations about the visual perception of light and color, the personal experience of remembering and inventing, and the natural illusiveness of time."

The gallery says:

“The viewer recognizes these as landscapes. Serio gives us a horizon line as a foothold for this but beyond this reference the compositions are investigations of color and shape, rhythmically layered to represent perceptions of light, land, and memories.’’

Otter Creek Falls, in Middlebury

Lithograph of Middlebury from 1886 by L.R. Burleigh with list of landmarks

Llewellyn King: Utilities urgently need to add transmission

In Seekonk, Mass., during the height of the Jan. 29 blizzard. Many people in southeastern Massachusetts lost power in the storm, in which winds gusted to hurricane force.

Logo of Independent System Operator, which oversees the region’s electric grid.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

It has become second nature. You hear that bad weather is coming and rush to the store to stock up on bottled water and canned and other non-perishable foods. You check your flashlight batteries.

For a few days, we are all survivalists. Why? Because we are resigned to the idea that bad weather equates with a loss of electrical power.

What happens is the fortunate have emergency generators hooked up to their freestanding houses. The rest of us just hope for the best, but with real fear of days without heat.

It happened most severely in Texas in February 2021; during Winter Storm Uri, which lasted five days, 250 people died. Recently, during the Blizzard of 2022, on Jan. 28-29, 100,000 people in Massachusetts endured bitter cold nights when the electricity failed. There were more power failures in the most recent ice storm.

There are 3,000 electric utilities in the United States. Sixty large ones, like Consolidated Edison, NextEra Energy, Pacific Gas and Electric, and the Tennessee Valley Authority, supply 70 percent of the nation’s electricity. Nonetheless, the rest are critical in their communities.

All utilities, large and small, have much in common: They are all under pressure to replace coal and natural gas generation with renewables, which means solar and wind. No new, big hydro is planned, and nuclear is losing market share as plants go out of service because they are too expensive to operate.

The word the utilities like to use is resilience. It means that they will do their best to keep the lights on and to restore power as fast as possible if they fail due to bad weather. When those events threaten, the utilities spring into action, dispatching crews to each other’s trouble spots as though they were ordering up the cavalry. The utilities have become very proactive, but if storms are severe, it often isn’t enough.

Now, besides more frequent severe weather events, utilities face the possibility of destabilization on another front, due to switching to renewables before new storage and battery technology is available or deployed.

The first step to avoid new instability -- and it is a critical one -- is to add transmission. This would move electricity from where it is generated in wind corridors and sun-drenched states to where the demand is, often in a different time zone.

Duane Highley, president and CEO of Tri-State Generation and Transmission Association, which serves four states in the West from its base in Westminster, Colo., says new west-east and east-west transmission is critical to take the power from the resource-rich Intermountain states to the population centers in the East and to California.

“Most existing transmission lines run north to south. They aren’t getting the renewables to the load centers,” Highley says.

Echoing this theme, Alice Moy-Gonzalez, senior vice president of strategic development at Anterix, a communications company providing broadband private networks that make the grid more secure and efficient, sees pressure on the grid from renewables and from new customer demands (such as electrical vehicles) as electrification spreads throughout society.

“The use of advanced secure communications to monitor all of these resources and coordinate their operation will be key to maintaining reliability and optimization as we modernize the grid,” Moy-Gonzalez says.

Better communications are one step in the way forward, but new lines are at the heart of the solution.

The Biden administration, as part of its infrastructure plan, has singled out the grid for special attention under the rubric “Build a Better Grid.” It has also earmarked $20 billion of already appropriated funds to get the ball rolling.

Industry lobbyists in Washington say they have the outlines of the Department of Energy plan, but details are slow to emerge. Considered particularly critical is the administration’s commitment to ease and coordinate siting obstacles with the states and affected communities.

Utilities are challenged to increase the resilience of the grid they have and to expand it before it becomes more unstable.

Clint Vince, who heads the U.S. energy practice at Dentons, the world’s largest law firm, says, “We aren’t going to reach the growth in renewables needed to address climate without exponential growth in major interstate transmission. And sadly, we won’t succeed with that goal on our current trajectory. We will need significant federal intervention because collaboration among the states simply hasn’t been working within the timeframe needed.”

Better keep the flashlights handy.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington., D.C.

Linda Gasparello

Co-host and Producer

"White House Chronicle" on PBS

Mobile: (202) 441-2703

Website: whchronicle.com

Stephen J. Nelson: Of visionary John Kemeny and decades of court battles over affirmative action at colleges

John G. Kemeny (1926-1992), Hungarian-born mathematician, computer scientist and president of Dartmouth College in 1970-1981

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

The U.S. Supreme Court is taking up affirmative action at colleges and universities for the sixth time in 50 years. In that litany, an early case was the University of California vs. Bakke. Bakke complained about being denied admission to the university’s medical school because seats were guaranteed for minority applicants, thus barring the door to him and other white applicants.

When the Bakke case was on the court’s docket, John Kemeny was president of Dartmouth College, in Hanover, N.H. The Dartmouth board of trustees wanted a public statement by the college on Bakke. Given their strong confidence in Kemeny, they gave him sole authority to craft Dartmouth’s stand on affirmative action. Kemeny’s voice from his bully pulpit into the public square about the Bakke case echoes today.

Kemeny’s argument displays ahead-of-the-curve insights. His major concern, one still very much at stake in the outcome of the court’s deliberations today, was that colleges had to be able to maintain their fundamental purposes in the face of any court judgment. Should the court mandate a cookie-cutter approach for college admissions, the unintended consequence would be to reduce diversity among institutions of higher education something that Kemeny said simply would be “highly undesirable.”

Using Dartmouth’s example, Kemeny underscored that the board had affirmed the college’s purpose as “the education of men and women with a high potential for making a significant positive impact on society.”

The board did not define that purpose as “the education of students who have the ability to accumulate high grade-point averages at the College,” a statement that would be “ludicrous!”

Kemeny pushed back against the court going over the edge if it were to compel colleges and universities exclusively to use test scores and presumed objective measures to decide which students to admit. That legal edict would restrict colleges from recruiting and admitting musicians, athletes and any student uniquely qualified to contribute to a student body and a college. Quotas of any sort were in his judgment “abhorrent.” Beware what you wish for.

Years after Bakke, in the 2003 University of Michigan cases, Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor asserted that colleges had roughly 25 more years to solve their equity and equal-opportunity problems. After that time, reliance on affirmative-action policies would run out. O’Conner’s clock continues to tick.

Getting to where she urged has proved difficult. Progress on the diversity front in the Ivory Tower is glacial and complicated because competing interests must be addressed and give their blessing or at least not actively resist new programs and initiatives. More time than O’Conner predicted is clearly needed. Ideological players on all sides agree that substantive changes in fairness and equity is the arrival point, though there will always be huge differences about the roadmap.

Greater diversity at colleges and universities makes their campus communities more engaging, more demanding, more rewarding and their members more fully educated. Absent diversity, the highest values of what we want a college education to be will remain outside our grasp. That is true for our body politic inside and outside the gates as graduates take their places in the social of communities and the nation. This picture is the goal, but how to get there and how long it will take are the great unknowns.

The new challenge brought by Students for Fair Admissions alleges that Harvard University discriminates against Asian-American students and the University of North Carolina discriminates against white and Asian- American applicants by continuing the use of race as an upfront criteria in admissions rather than observing a race-blind approach that would place more credence and consideration on an applicant’s struggles with discrimination in their life experiences.

The Supreme Court, of course, relies on arguments. The presidents of our colleges and universities must as a group get in the arena, present their case and gather defenders in amicus briefs. The cards will fall as the court dictates. However, jousting over what the Justices will say has to be embraced. It must be made clear to the court’s justices that they must not do harm to hard-fought policies designed to make our colleges and universities equitable, fair and open to diverse populations. Confining latitude and judgments about the scope of admissions procedures and aspirations to add greater diversity to their student bodies would rob colleges and universities of the very autonomy and freedom in their affairs that makes us the envy of the world. The shape of the future of diversity at our colleges is at stake and college presidents must weigh in with all the authority they can muster.

The voices of college presidents have to be front and center in this debate and in the court’s verdict. John Kemeny’s wisdom is a mantle that today’s presidents and those of us concerned diversity and equal opportunity on our campus must take up.

Stephen J. Nelson is professor of educational leadership at Bridgewater State University and senior scholar with the Leadership Alliance at Brown University. He is the author of the recently released book, John G. Kemeny and Dartmouth College: The Man, the Times, and the College Presidency. He has written several NEJHE pieces on the college presidency.

Chris Powell: Mocking the law and getting little integration

In Constitution Plaza in downtown Hartford

MANCHESTER, Conn.

What has Connecticut gotten for the 33 years of litigation in the Hartford school-integration case of Sheff v. O'Neill, which purportedly ended last week with a settlement between the plaintiffs and state government?

The first result of the Sheff business is a mockery of state constitutional law and the courts themselves.

The state Supreme Court's 4-3 decision in the Sheff case in 1996 proclaimed that every public school student in the state -- not just students in Hartford -- has a state constitutional right to a racially integrated education. That conclusion was not only dubious law -- it was torn to shreds by the brilliant dissent of Justice David M. Borden -- but also impossible to achieve as a practical matter, since it would have required the assignment to school by their race of tens of thousands of students across the state, which federal courts would have forbidden as federally unconstitutional.

Even the Sheff plaintiffs knew that comprehensive racial integration was impossible and they never pressed for it. They were concerned only about Hartford, where the school population consisted overwhelmingly of impoverished, fatherless, and neglected minority children whose educational performance was miserable.

While the state Supreme Court's proclamation of a constitutional right stands, 26 years later it is being violated in most towns and there is and will be no effort to enforce it.

So much for constitutional law in Connecticut.

The second result of the Sheff case is the continued de-facto racial segregation of the Hartford schools themselves.

Because of the state's creation of Hartford-area "magnet" or regional schools that draw both city and suburban students, the city's schools are less segregated than they were. But still about 60 percent of Hartford students are enrolled in schools considered segregated. Similarly, most suburban and rural schools in the state remain segregated too, overwhelmingly white.

Connecticut's huge and long-lamented racial-achievement gap between white and minority students endures in both the Hartford area and the state generally. And while the integration produced by the regional schools may have good results over the long term as students gain more diverse friends and acquaintances, the regional schools have had a negative effect as well.

That is, the regional schools drain Hartford's neighborhood schools of their more-parented students, leaving the neighborhood schools with even more disadvantaged populations. While the regional schools are advocated for mixing disadvantaged minority city students with middle-class suburban students who may provide better examples academically, this comes at the expense of neighborhood schools that lose their own better examples.

Even so, the Sheff settlement has state government promising still more regional schools and school-choice programs -- more openings for city students in suburban schools -- until there is room for every Hartford student who wants to escape a neighborhood school.

Maybe then it will be possible to acknowledge the underlying problem officially -- the most neglected kids, the core of the unassimilable urban poverty that long has driven the white flight to the suburbs and now is driving the minority middle class out of the cities as well.

In recent years state government is estimated to have spent hundreds of millions of dollars on regional schools in the Hartford area and the complicated transportation arrangements they require. The integration this has produced is so small as to invite questions as to whether other approaches might be more productive and cheaper.

Poverty may be a virtue in religious orders but it is a curse in society, since the poor don't pull their own weight. So suburban fear of housing for the poor is fair, and such housing is difficult to develop in the suburbs even as state law purports to require it in the towns with the most exclusive zoning.

So maybe once regional schools and choice programs have drained Hartford and the state's other troubled cities of their most-parented students a decade or two from now, government in Connecticut will be compelled to examine the neglected children who remain and to inquire into what has made them so poor. If it is honest, such an inquiry will begin with government itself.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

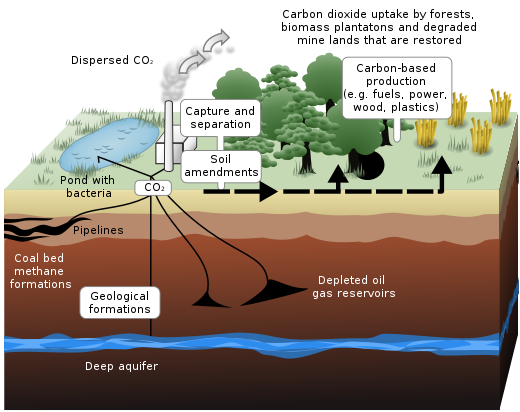

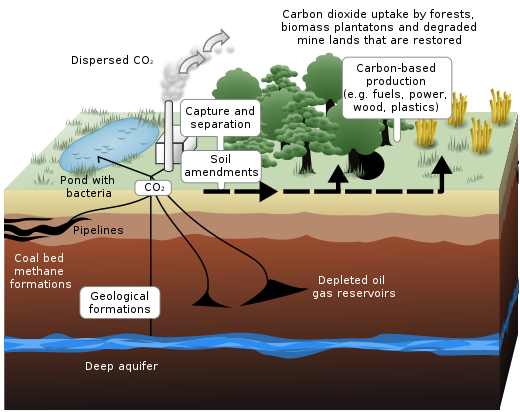

Southwest Airlines’ $10 million pledge to Yale to research natural carbon capture

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

“Southwest Airlines, announced a $10 million commitment to New Haven-based Yale University’s Center for Natural Carbon Capture (YCNCC) to research technological advancements and find new solutions to reduce net greenhouse-gas emissions.

“The pledge will also support research and educational efforts at the Yale School of the Environment to explore the current state of sustainability, strategy, policy, and economics, emphasizing trends related to the aviation industry and focusing on finding new ways to reduce atmospheric carbon. Established in March 2021, YCNCC is focused on strategies for removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and safely storing it within plants, soils, rocks, and oceans. It also aims to develop methods for industrial carbon capture to convert carbon dioxide into useful fuels, plastics, and building materials.

“‘This innovative partnership gives Southwest the opportunity to support the development of crucial science to combat climate change, including fostering innovative research aimed at informing and advancing efforts to reduce atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations,’ said Stacy Malphurs, vice president of supply chain management & environmental sustainability for Southwest Airlines. We recognize the importance of supporting initiatives that take a holistic approach to de-carbonization in the long-term, which aligns with the U.S. government’s goal for the aviation industry to be carbon neutral by 2050.’

‘Migrant to nomad’

From the show“The Levitating Perils” (video installation), by Frank Wang Yefeng, at the Chazan Gallery at Wheeler, Providence, Feb. 10-March 2

The gallery says that the mixed-media artist's works often relate to the experience of being a Chinese immigrant in the United States. He “left his place of origin at a young age, the memory from a migrant to a nomad has led him to investigate the transformation of emotions, autonomous objects of continuous movements, and the in-between states of nomadic subjects that occur in both virtual and physical realms."

Glass nips better

A collector's cabinet full of miniature bottles

— Photo by kerinin

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Rhode Island state legislators are considering banning those plastic nip liquor bottles of which you see all too many along roads, sidewalks and on beaches.

Good idea. They’ve added to the plastic pollution you see everywhere and that’s bad for wildlife as well as aesthetics (and thus tourism). That’s in part because all too many of the people who buy them are slobs and/or drunk.

And the smallness of the nip bottles discourages reuse.

If only more people demanded glass containers, which can be used indefinitely. And even if slobs dropped them in the water or on, say, a beach, they gradually wear down from the abrasion from sand, etc., and can become quite beautiful Anyone remember collecting “sea glass” (aks “beach glass”) as a kid?

Will someone some day finally invent a plastic that degrades rapidly with no harm to the environment?

“Sea glass’’

And stick around

“Hug and kiss whoever helped get you – financially, mentally, morally, emotionally – to this day. Parents, mentors, friends, teachers. It you’re too uptight to do that, at least do the old handshake thing, but I recommend a hug and a kiss. Don’t let the sun go down without saying thank you to someone, and without admitting to yourself that absolutely no one gets this far alone.’’

Stephen King (born 1947), hugely successful novelist, and a Maine native, in his University of Maine at Orono (the flagship campus of the university) commencement address in 2005.

And:

King has chosen to live in his native state for most of his life. His main home is in nearby Bangor. So he asked the graduates to stay in the Pine Tree State.

''This can be home if you want it to be. If you leave, you will miss it, so you might as well skip the going away part."

Stephen King’s house in Bangor, built in 1858

'A blue-gray glow'

“Underneath,

mice and shrews are moving,

the dog can hear them down there,

out of sight and reach….’’

“a whole landscape laid out

in a blue-gray glow….’’

— From “Listening Through Snow,’’ by Burlington, Vt.-based poet and teacher Nora Mitchell

David Warsh: Putin wants to get his foes thinking

Vladimir Putin in 2018

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The first bright light on the murky situation in Ukraine shone Jan. 28, when Ukraine officials “sharply criticized” the Biden administration, according to The New York Times in its Jan. 29 edition, “for its ominous warnings of an imminent Russian attack,” saying that the U.S. was spreading unnecessary alarm.

Since those warnings have been front-page news for weeks in The Times and The Washington Post. Ukrainian President Volodynyr Zelensky implicitly rebuked the American press as well. As the lead story in The Post indignantly put it, he “ [took] aim at his most important security partners as his own military braced for a potential security attack.”

Meanwhile, Yaroslav Trofimov, The Wall Street Journal’s chief foreign-affairs correspondent, writing Jan. 27 in the paper’s news pages, identified a well-camouflaged off-ramp to the present stand-off, in the form of an agreement signed in the wake of the Russian-backed offensive in eastern Ukraine in February 2015. The so-called Minsk-2 had since remained dormant, he wrote, until recently.

Now, after a long freeze, senior Ukrainian and Russian officials are talking about implementing the Minsk-2 accords once again, with France and Germany seeing this process as a possible off-ramp that would allow Russian President Vladimir Putin a face-saving way to de-escalate.

I have had a long-standing interest in this story. In 2016, in the expectation that Hillary Clinton would be elected U.S. president, I began a small book with a view to warning about the ill consequences of the willy-nilly expansion of the NATO alliance that President Bill Clinton had begun in 1993, which was pursued, despite escalating Russian objections, by successors George W. Bush and Barack Obama. The election of Donald Trump intervened. Because They Could: The Harvard Russia Scandal (and NATO Expansion) after Twenty-Five Years appeared in 2018.

I was relieved when Joe Biden defeated Trump, in 2020, but alarmed in 2021 when Biden installed a senior member of Mrs. Clinton’s foreign-policy team in the State Department, as undersecretary for political affairs. Seven years before, as assistant secretary of state for European and Eurasian affairs, Victoria Nuland had directed U.S. policy towards Russia and Ukraine and passed out cookies to Ukrainian protestors during the anti-Russian Maidan demonstrations in February 2014. At their climax, Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych, a Putin ally, fled to exile in southern Russia, and, in short order, Russia seized Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula.

A couple of weeks ago, I suggested that, when it came to interpreting the situation in Ukraine, it would be wise to pay attention to a more diverse medley of voices than the chorus of administration sources uncritically amplified by The Times and The Post. David Johnson, proprietor of Johnson’s Russia List, told readers he didn’t think there would be an invasion. Neither did I. Russian and Ukrainian citizens seemed to agree; according to reports in the WSJ and the Financial Times, they were going about their business normally.

Why? Presumably because most locals understood Russian maneuvers on their borders to be a show of force, intended to affect negotiations between Kyiv and Moscow.

As for what Putin may be thinking and privately saying – his strategic aims and his tactics – I pay particular attention to Harvard historian Timothy Colton. His nuanced biography of Boris Yeltsin makes him an especially interesting interpreter of the man Yeltsin in 1999 designated his successor.

Colton, a Canadian, is a member of the Valdai Discussion Club, a Moscow-based think-tank, established in 2004 and closely linked to Putin. Its annual meetings have been patterned on those of Klaus Schwab’s better-known World Economic Forum, in Davos, Switzerland. Membership consists mainly of research scholars, East and West. A little essay by Colton surfaced 10 days ago on the club’s site, as What Does Putin’s Conservatism Seek to Conserve?

Colton observed that Putin’s personal ideas and goals, as opposed to his exercise of power as a political leader, are seldom discussed. That is not surprising, he wrote, as Putin had relatively little to say about his own convictions during his first two terms in office, aside from First Person, a book of interviews published just as he took office in 2000. That reticence diminished in his third term, Colton continued, especially now as his fourth term begins. In a speech to a Valdai conference last autumn, whose theme was “The Individual, Values, and the State,” Putin borrowed a foreign term – conservatism – and used it four times, each time with a slightly different modifier, to describe his own fundamental views. Colton wrote:

Putin noted at Valdai that he started speaking about conservativism a while back, but had doubled down on it in response not to internal Russian developments but to the fraught international situation. “Now, when the world is going through a structural crisis, reasonable conservatism as the foundation for a political course has skyrocketed in importance, precisely because of the proliferating risks and dangers and the fragility of the reality around us.”

“This conservative approach,” he stated, “is not about an ignorant traditionalism, dread of change, or a game of hold, much less about withdrawing into our own shell.” Instead, it was something positive: “It is primarily about reliance on time-tested tradition, the preservation and increase of the population, realistic assessment of oneself and others, an accurate alignment of priorities, correlation of necessity and possibility, prudent formulation of goals, and a principled rejection of extremism as a means of action.”

What of the wellsprings of Putin’s conservatism? Perhaps nothing more fundamental than the preservation of his own power. “Two decades in the Kremlin, and the prospect of years more, may incline him increasingly toward rationalizations of the status quo as principled conservatism.” An alternative explanation would emphasize life experience. The fragility that Putin was talking about at Valdai was that of the present moment, Colton wrote, but, he continued,

Putin has commented more than once on the inherent volatility of human affairs. “Often there are things that seem impossible to us,” he said in the First Person interviews, “but then all of a sudden — bang!” He gave as his illustration the event that by all accounts traumatized him more than any other — the implosion of the USSR. “That is the way it was with the Soviet Union. Who could have imagined that it would have up and collapsed? Even in your worst nightmares no one could have foretold this.” Sticking with “time-tested” formulas would suit such a temperament [Colton wrote].

What sorts of time-tested formulas might the Russian leader adopt? Colton, a player in many venues, is constrained to speak and write so carefully that it is hard for an outsider to know what with any confidence what point he was making to insiders in his recent essay. As journalist, I am not.

One time-tested formula Putin has employed frequently, to the point of habit, is a tradition I think of as having evolved in the West. This is the practice of setting out a frank public account of public-policy views. It is a rhetorical tactic set out with especial felicity by the framers of the U.S. Declaration of Independence, to the effect that “a decent respect to the opinions of mankind” requires those undertaking dramatic actions to declare the causes that impel them to act. In general, this Putin has done.

There was, for instance, his frank appraisal of the situation of Russia at the Turn of the Millennium, published as one of those First Person interviews in 2000. After he failed to dissuade George Bush from invading Iraq, Putin lambasted the U.S. in 2007 in a widely publicized speech to a security conference in in Munich. In 2014, after annexing Crimea, he delivered another blistering speech, this time to the both houses of the Russian parliament. And last summer, he published a long essay asserting his conviction that Ukrainians and Russians share “the same historical and spiritual space.

What might he do if his army goes home, having made its rhetorical point without firing a shot? My hunch is that he will give another speech.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

Spiridon Putin, Vladimir Putin’s paternal grandfather, a personal cook of Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin

Roger Warburton: Nearby ocean warming a climate-change warning for New England

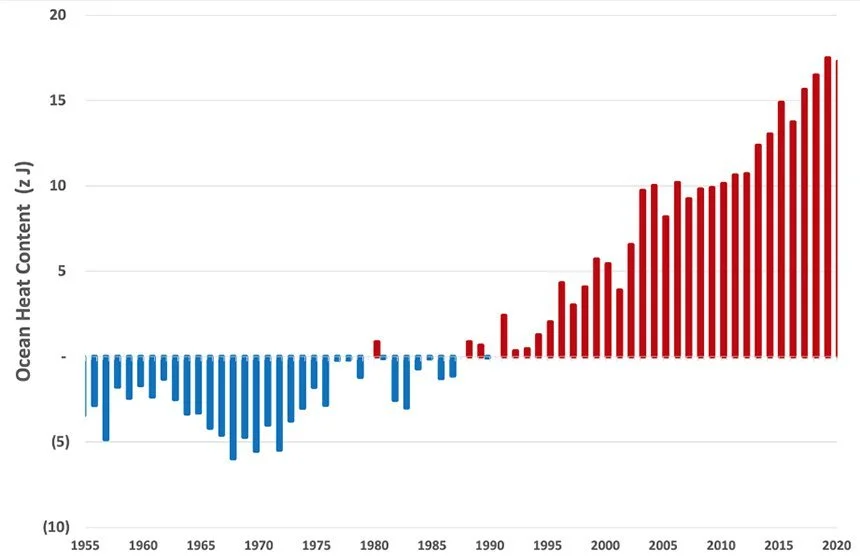

The changes in heat content of the top 700 meters of the world’s oceans between 1955 and 2020.

— Chart by Roger Warburton/NCEI and NOAA

New England’s historical and cultural identity is inextricably linked to the ocean that laps at nearly 6,200 miles of coastline. And the region’s ocean waters are warming, and not just a little.

The above chart shows just how much the ocean has warmed over the past 65 years and, due to the accumulation of greenhouse gases, the heat dumped into the ocean has doubled since 1993. It is even more concerning that ocean warming has accelerated since 2010.

The world’s oceans, in 2021, were the hottest ever recorded by humans.

The findings of the data from the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), which is part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), have been confirmed by Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization, China’s Institute of Atmospheric Physics, and the Japan Meteorological Agency’s Meteorological Research Institute.

The news for New England is worse, as the ocean here is heating up faster than that of the rest of the world.

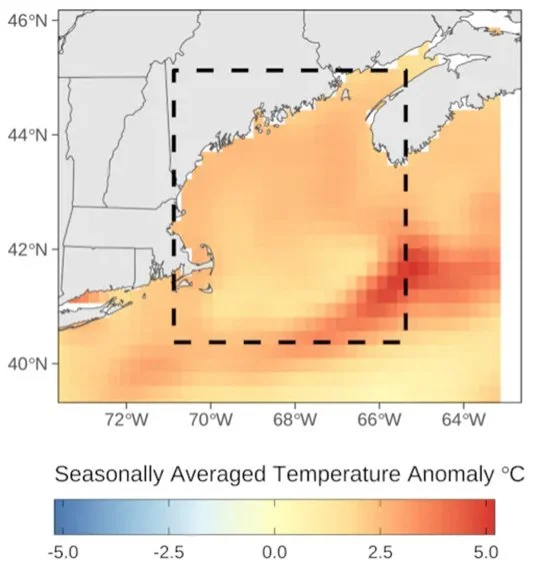

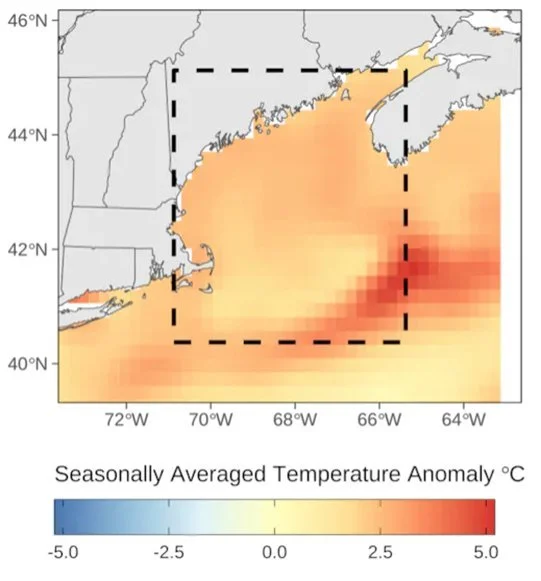

This map illustrates the seasonally averaged sea-surface temperature anomaly in the Gulf of Maine.

—Gulf of Maine Research Institute

The Gulf of Maine Research Institute announced that between September and November of last year, the warmth of inlet waters adjacent to Maine and northern Massachusetts was the highest on record.

“This year [the Gulf of Maine] was exceptionally warm,” said Kathy Mills, who runs the Integrated Systems Ecology laboratory at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute. “I was very surprised.”

The Gulf of Maine is warming faster than 96 percent of the world’s oceans, increasing at a rate of 0.1 degrees Celsius (0.18 degrees Fahrenheit) annually over the past four decades.

The increased concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere traps heat in the air. The air in contact with the ocean transfers heat to the ocean, increasing what is called the ocean heat content (OHC).

The first measurements of ocean data were taken on Capt. James Cook’s second voyage (1772-1775). Although not very accurate, those measurements were among the first instances of oceanographic data recorded and preserved.

Today, ocean measurements are taken by a variety of modern instruments deployed from ships, airplanes, satellites and, more recently, underwater robots. A 2013 study by John Abraham, a professor at the University of St. Thomas, contains an interesting historical overview of ocean measurements.

Abraham’s study used data from new instruments, such as expendable bathythermographs and Argo floats. The Argo program is an array of more than 3,000 autonomous floats that return oceanic climate data and has advanced the breadth, quality and distribution of oceanographic data.

As heat accumulates in the Earth’s oceans, they expand in volume, making this expansion one of the largest contributors to sea-level rise.

Although concentrations of greenhouse gases have risen steadily, the change in ocean-heat content varies from year to year, as the chart above shows. Year-to-year changes are influenced by events, such as volcanic eruptions and recurring patterns such as El Niño. In fact, in the chart one can detect short-term cooling from major volcanic eruptions of Mounts Agung (1963), El Chichón (1982) and Pinatubo (1991).

The ocean’s temperature plays an important role in the Earth’s climate crisis because heat from ocean surface waters provides energy for storms and influences weather patterns.

Roger Warburton, Ph.D., is a Newport, R.I., resident. He can be reached at rdh.warburton@gmail.com.

References: Cheng, L. J, and Coauthors, 2022, “Another record: Ocean warming continues through 2021 despite La Niña conditions. Adv. Atmos. Sci., https://doi.org/10.1007/s00376-022-1461-3.

Abraham, J. P., et al. (2013), “A review of global ocean temperature observations: Implications for ocean heat content estimates and climate change,” Rev. Geophys.,51, 450–483, https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/rog.20022.

‘Name the unnameable'

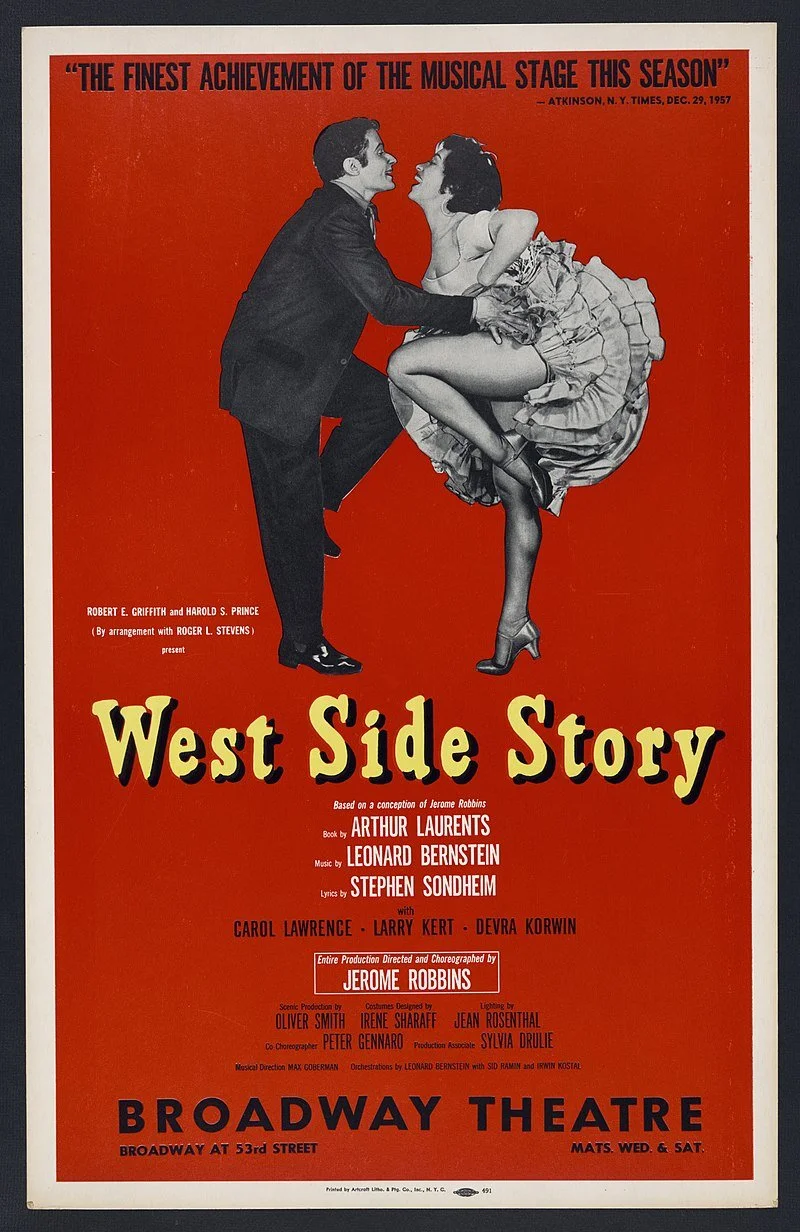

Leonard Bernstein in 1977

“Music can name the unnameable and communicate the unknowable.’’

— Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990), celebrated American composer and conductor. He was born in Lawrence, Mass., grew up in Boston and graduated from Harvard. Though based in New York, he often conducted at the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s summer venue — Tanglewood, in Lenox in the Massachusetts Berkshires.

Tanglewood Music Shed and lawn, where people lie on the grass to listen to the music.

— Photo by Daderot.

1958 poster

Makes you love winter, at least for a few minutes

A gorgeous morning on the estuary in Rowayton, Conn., on Jan. 30 after the beautiful if inconvenient snowstorm the day before.

— Photo by Hilary Cosell

A model of eco-responsibility

“Our Lady of the Recycling Center” (encaustic over fiber clay with found objects), by Otty Merrill, a member of New England Wax (newenglandwax.com) who is based in Tenants Harbor, Maine.

She says in her Web site:

“Though I am surrounded by magnificent landscapes and brilliant natural light on the coast of Maine where I live and work, I tend to turn inward when making art, drawing on memories, travels and emotions. Through color, texture and often embedding photos and other materials into the surfaces of my work, I lean towards semi-abstract and interpretive imagery in my compositions. I admire the works of artists such as Harold Garde (of Maine), Milton Avery, Marsden Hartley and Mary Cassatt. You might see their influences in my work. I strive to be honest, original and hopefully a little unique, both in my artwork and my life.’’

Sail Loft, Tenants Harbor, St. George, Maine.

— Photo by Magicpiano

‘The New England idea’ could no longer serve

Dartmouth Hall at Dartmouth College, Hanover, N.H.

“Modern American literature was born in protest, born in rebellion, born out of the sense of loss and indirection which was imposed upon the new generations out of the realization that the old formal culture —the ‘New England idea’ -- could no longer serve.”

— Alfred Kazin (1915-1998), American writer, best known as a literary critic. He wrote a lot about the immigrant experience.

Don Pesci: With the middle class forgotten?

VERNON, Conn.

The question “Why do Democrats win elections in Connecticut?” is intimately bound up with the question “How do Democrats win elections in Connecticut?”

It helps a great deal to have a 400-pound gorilla in your corner.

What shall we make of the proposition that we have the kind of government we have in Connecticut, left of center and increasingly progressive, because we have the kind of media we have in Connecticut, left of center and increasingly progressive?

The media, as a political campaign amplifier, is not unimportant in campaigns. If you have a message and do not have a media to relay it objectively, you are at a considerable disadvantage. The media may not be the message, but you cannot present yourself adequately to voters if your message is damagingly edited by a media that has, in effect, chosen sides.

Is this the case in Connecticut?

The answer to the question is – maybe.

There has got to be some reason, other than superior numbers, why there has not been for many years a Republican in Connecticut’s U.S. congressional delegation. It is true that registered Democrats in Connecticut outnumber registered Republicans roughly by a ratio of two to one, and there are in the state slightly more unaffiliated than Democrats. But that was the case as well when the distribution of Republicans and Democrats within the U.S. congressional delegation was more or less even.

Money remains important in campaigns. Incumbents, of course, are always able to out-finance challengers, even though challengers in Connecticut may, provided they are willing to abide by stringent regulations, garner money for campaigns through tax dollar contributions. Self-financing of campaigns is also an option, limited, we are told, to the sort of people who own yachts and do not worry overmuch about the price of beef and gas.

Increasingly, the Democratic, not the Republican, Party is becoming the party of the rich and the disenfranchised poor. The usually productive middle class is the real orphan of post-modern politics.

According to IRS data, Democrats have now become the party of the wealthy, a turnabout when it was the party of the poor and middle class decades ago. “In 1993, the last time a president asked Congress to vote in a significant tax hike,” Bloomberg reports, “the typical congressional district represented by a Republican was 14 percent richer than the typical Democratic district, according to household-income data from the Census Bureau. By 2020, those districts were 13 percent poorer…. Democrats now represent 65 percent of taxpayers with a household income of $500,000 or more, according to pre-pandemic Internal Revenue Service statistics.”

Still, the amount of money poured into campaigns is not alone decisive. Linda McMahon, a Republican, self-financed a senatorial campaign in which she had spent $50 million, and yet she was not successful in overthrowing a popular Democrat, Dick Blumenthal, also a millionaire. Many regard this as a hopeful sign, indicating that elections cannot be bought.

Ah, but we know they can be bought, usually by incumbents whose campaign bank accounts are flush, swelling with about a million in cash even before their campaigns have officially begun.

Congresswoman Rosa DeLauro, also a millionaire, has consistently out financed and outspent all of her Republican opponents. Such is the distribution of forces in DeLauro’s 3rd District that DeLauro likely need not spend a single campaign dollar to win against any Republican challenger. That rule holds true in Congressman John Larson’s gerrymandered 1st District as well. Exceptions that prove the rule, such as McMahon’s campaign against Blumenthal, do not invalidate the rule. And the rule is: Majority incumbent Democrat politicians, moderate or otherwise, tend to rule. Money and political entropy win elections. In the land of steady bad habits, elections lie in the hands of those disposing of superior political force, mostly incumbents, and de-energized opposition voters.

“Stefanowski to put $10 million into {gubernatorial} bid,” the front page, above the fold story in The Hartford Courant announced. That would be $40 million less than was spend by McMahon on her campaign against Dick Blumenthal for the U.S. Senate. And Stefanowski’s contribution to his own campaign will be dwarfed by the money that Gov. Ned Lamont will deploy in his own campaign, the big advantages of incumbency, and Connecticut’s 400-pound media gorilla, no mean advantage. The endorsements of the 2022 gubernatorial campaign likely have already been written.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.