Vox clamantis in deserto

Bet the farm

UConn women’s basketball team’s 2004 NCAA Championship trophy, ring and signed ball

—Photo by Sphilbrick

“Bottom line, you’re either a risk taker, or you’re not, and if you never take take risks, you’ll never win big.’’

— Luigi “Geno’’ Auriemma (born 1954), coach of the University of Connecticut’s astonishingly successful women’s basketball team. The Italian-born coach has led UConn to 11 NCAA Division I national championships, the most in women's college basketball history, and has won eight national Naismith College Coach of the Year awards.

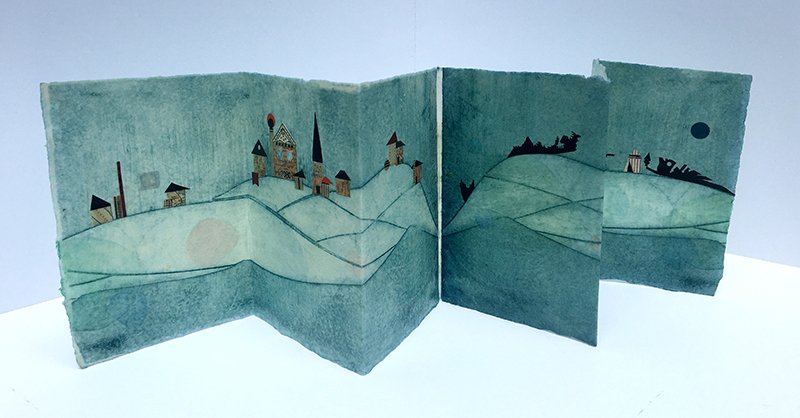

Folding up winter

“Dragon Journey Book” (monoprint, antique paper, encaustic, on BFK paper), by Soosen Dunholter, who lives in Peterboro, N.H., which has long hosted many artists. The MacDowell residence there for artists founded in 1907, has attracted famed creative types (painters, writers, composers, etc.) from around America since its inception. Ms. Dunholter is a member of New England Wax (newenglandwax.com). Hit this link for her Web site.

View of Peterboro circa 1907, looking toward Mt. Monadnock.

Sarah Varney: Omicron hits even super-vaxxed Vermont but packs less punch

Lamoille County Superior Courthouse, in Hyde Park, Vt.

Fog in the Lamoille River valley in Hyde Park.

Even Eden, a snow-covered paradise in northern Vermont’s Lamoille County, is poisoned by Omicron. {The area was poisoned for decades by the mining of asbestos at Belvidere Mountain.}

The nearly vertical ascent of new coronavirus cases in recent weeks, before peaking in mid-January, affected nearly every mountain hamlet, every shuttered factory town, every frozen bucolic college campus in this state despite its near-perfect vaccination record.

Of all the states, Vermont appeared best prepared for the omicron battle: It is the nation’s most vaccinated state against covid, with nearly 80% of residents fully vaccinated — and 95% of residents age 65 and up, the age group considered most vulnerable to serious risk of covid.

Yet, even this super-vaxxed state has not proved impenetrable. The state in mid-January hit record highs for residents hospitalized with COVID-19; elective surgeries in some Vermont hospitals are on hold; and schools and day care centers are in a tailspin from the numbers of staff and teacher absences and students quarantined at home. Hospitals are leaning on Federal Emergency Management Agency paramedics and EMTs.

And, in a troubling sign of what lies ahead for the remaining winter months: about 1 in 10 covid tests in Vermont are positive, a startling rise from the summer months when the delta variant on the loose elsewhere in the country barely registered here.

“It shows how transmissible Omicron is,” said Dr. Trey Dobson, chief medical officer at Southwestern Vermont Medical Center, a nonprofit hospital in Bennington. “Even if someone is vaccinated, you’re going to breathe it in, it’s going to replicate, and if you test, you’re going to be positive.”

But experts are quick to note that Vermont also serves as a window into what’s possible as the U.S. learns to live with covid. Although nearly universal vaccination could not keep the highly mutated Omicron variant from sweeping through the state, Vermont’s collective measures do appear to be protecting residents from the worst of the contagion’s damage. Vermont’s COVID-related hospitalization rates, while higher than last winter’s peak, still rank last in the nation. And overall death rates also rank comparatively low.

Children in Vermont are testing positive for COVID, and pediatric hospitalizations have increased. But an accompanying decrease in other seasonal pediatric illnesses, such as influenza and respiratory syncytial virus, and the vaccinated status of the majority of the state’s eligible children, has eased the strain on hospitals that many other states are facing.

“I have to remind people that cases don’t mean disease, and I think we’re seeing that in Vermont,” said Dr. Rebecca Bell, a pediatric critical-care specialist at the University of Vermont Health Network in Burlington, the only pediatric intensive-care hospital in the state. “We have a lot of cases, but we’re not seeing a lot of severe disease and hospitalization.”

She added, “I have not admitted a vaccinated child to the hospital with COVID.”

Vermont in many ways embodies the future that the Biden administration and public health officials aim to usher in: high vaccination rates across all races and ethnicities; adherence to evolving public health guidelines; and a stick-to-itiveness and social cohesion when the virus is swarming. There is no “good enough” in Vermont, a state of just 645,000 residents. While vaccination efforts among adults and children have stalled elsewhere, Vermont is pressing hard to better its near-perfect score.

“We have a high percentage of kids vaccinated, but we could do better,” said Dobson.

He continues to urge unvaccinated patients to attend his weekly vaccination clinic. The “first-timers” showing up seem to have held off due to schedules or indifference rather than major reservations about the vaccines. “They are nonchalant about it,” he said. “I ask, ‘Why now?’ And they say, ‘My job required it.’”

Replicating Vermont’s success may prove difficult.

“There is a New England small-town dynamic,” said Dr. Tim Lahey, director of clinical ethics at the University of Vermont Medical Center in Burlington. “It’s easy to imagine how your behavior impacts your neighbor and an expectation that we take care of each other.”

While other rural states in the Midwest and South have struggled to boost vaccination rates, New England, in general, is outpacing the pack. Behind Vermont, Rhode Island, Maine and Connecticut have the highest percentage of fully vaccinated residents in the country.

“It’s something beyond just the size,” said Dr. Ben Lee, an associate professor at the Robert Larner, M.D. College of Medicine at the University of Vermont. “There is a sense of communal responsibility here that is a bit unique.”

In a state with the motto “Freedom and Unity,” freedom has largely yielded to unity, and the state’s pandemic response has been met with eager compliance. “The general attitude here has been enthusiasm to be safer,” said Lahey.

Lahey credits the state’s Republican governor, Phil Scott, who has been “unambivalent about pro-vax messaging.” Combined with a “tendency to trust the vaccine, you get a different outcome than in places where political leaders are exploiting that minority voice and whipping people up in anger.”

Vermont’s medical leaders are advising state leaders to shift from a covid war footing — surveillance testing, contact tracing, quarantines, and lockdowns — to rapprochement: testing for COVID only if the outcome will change how doctors treat a patient; ceasing school-based surveillance testing and contact tracing; and recommending that students with symptoms simply recuperate at home.

Once the Omicron wave passes and less virus is circulating, Dobson said, a highly vaccinated state like Vermont “could really drop nearly all mitigation measures and society would function well.” Vermonters will become accustomed to taking appropriate measures to protect themselves, he said, not unlike wearing seat belts and driving cautiously to mitigate the risk of a car accident. “And yet,” he added, “it’s never zero risk.”

Spared the acrimony and bitterness that has alienated neighbor from neighbor in other states, Vermont may have something else in short supply elsewhere: stamina.

“All of us are just exhausted,” said Lahey, the ethics director. But “we’re exhausted with friends.”

Sarah Varney is a Kaiser Health News journalist.

svarney@kff.org, @SarahVarney4

William Morgan: A medical firm’s lost design opportunity in a very dramatic spot

When can a substandard commercial building be transformed into good architecture? Can a despised icon of second-rate design become a beloved object? More specifically, can the ugly behemoth of University Orthopedics, in East Providence, R.I., overcome the stigma of being just another spec medical box?

University Orthopedics, 1 Kettle Point, East Providence, N/E/M/D Architects.

Photo by William Morgan

Kettle Point, which is also the site of a development of the kind of suburban housing seen near urban interstates everywhere, is a gorgeous promontory with unparalleled views of the Providence skyline, a working waterfront and down Narragansett Bay. If this site were not in the perceived ugly step-sister of East Providence, it would have been one of the most desirable pieces of land in the state. One thinks of what will happen to the neighboring Metacomet Golf Club course, glorious open land with tremendous potential: It will turn into the all-too-familiar faux-Colonial tackiness on a sea of asphalt.

Kettle Point housing development.

— Photo by Will Morgan

On the positive side, University Orthopedics is affiliated with Brown University’s Warren Alpert Medical School and so is one of the parts of Providence’s growing importance as a medical center. And the Kettle Point location offers expansive and maybe healing views of water, trees and skyline. This giant infusion of sunlight and a panorama of nature must surely contribute to the wellness of the patients and the happiness of the staff.

Providence harbor and downtown skyline from Kettle Point.

— Photo by William Morgan

The ugly duckling becomes a swan when a loved one needs treatment for osteoporosis or a broken limb. Then the state-of-the-art facilities and the staff’s training seem more important than aesthetics. But do they need to be mutually exclusive? What if the medical group that commissioned 1 Kettle Point had hired someone besides a value-engineering-minded developer? At the very least, a location this visible demanded a better design than a clunky real-estate container wrapped in cheap materials, one that looks like every other new medical office block from Boise to Little Rock.

Does this signage or the Home Depot-orange cladding symbolize quality medicine and research?

— Photo by William Morgan

A sensitive architect might have at least given 1 Kettle Point a more distinctive skyline. (Please do not whine that a good architect costs too much, as a really smart designer might have even given University Orthopedics a lot more for less.) And given such an environmentally sensitive site, a landscape architect should have been consulted, and maybe allowed to integrate this hulk into its prime surroundings.

Alas, the response in our high-quality (for those who can access it) but often unobtainable, fragmented and even chaotic American health-care system to such concerns is always one of money. What a building looks like seems minor compared to the medicine it delivers. But why not heal the entire patient, while at the same time supporting a quality building that could have been a great advertisement for the practice, for Brown, for Rhode Island?

The handsome lights on the stair compliment the undoubtedly unintentional industrial aesthetic of the metal railings.

— Photo by Will Morgan

Hospital needs, admittedly, dictate their forms. Think of all the university-affiliated and other medical centers that keep spreading across America, with new wings and additions, often in disparate styles. Yet, a handsome example that exists within the jumble of buildings that comprise the main campus of the august Massachusetts General Hospital, in Boston, is the handsome neoclassical original building, designed by Charles Bulfinch. In erecting their signature structure, the hospital trustees chose the architect of both the Massachusetts State House and the U.S. Capitol.

Massachusetts General Hospital, Charles Bulfinch, architect, 1818-23. Wikimedia Commons.

My favorite example of a successful hospital that is also a work of architecture is a tuberculosis sanatorium in rural Finland, designed in 1929 by a then-young Alvar Aalto. Built with limited resources, the sanatorium launched Aalto’s career, but it also became one of the noblest landmarks of modern architecture. The revolutionary aspects of the design were dictated by the treatment of TB, which emphasized abundant sunlight and fresh air. Aalto fashioned draft-less windows and splash-less sinks, along with bright colors and inexpensive furniture that is still being manufactured.

Tuberculosis sanatorium, Paimio, Finland, 1929-33.

— Photo by the Alvar Aalto Foundation.

Why should what University Orthopedics looks like, and how it contributes to or detracts from its environment, be any less important than the layout of its labs and operating rooms? This medical group, presumably, would not accept low professional standards of medicine. So, it is unfortunate that, in the quest for medical integrity, University Orthopedics’ patronage did not aspire to high standards of architectural design

William Morgan has taught the history of modern architecture at several colleges, including Princeton and Roger Williams Universities, and has written extensively on Finnish architecture.

Save working waterfronts

Lobster boat in a Portland, Maine, Harbor marina competing for space with yachts.

—Photo by Bd2media

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Perhaps because I’m slightly involved with a project in Maine to preserve working waterfronts, I noticed that one of Rhode Island Gov. Dan McKee’s projects in his state-of-the-state address on Jan. 18 was to boost seafood-processing facilities in the state so that more of the profit from that processing stays in or close to the state. A fine idea for the Ocean State, which, like Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Maine, needs to do a lot more to preserve and if possible expand its working waterfronts.

People in many communities on our coasts are fighting to save waterfronts by being almost completely taken over by expensive houses and pleasure boats (replacing fishing boats). Many of these houses are used only seasonally. Suggestions requested!

For a look at how Mainers are trying to save what’s left of their working waterfronts, hit this link.

xxx

There are continuing controversies about the susceptibility of the Rhode Island Coastal Resources Management Council to political and business pressures. CRMC members are political appointees who aren’t required to have experience in coastal environmental matters.

So I ask yet again why it can’t just be abolished and all its powers granted to the (now understaffed) state Department of Environmental Management, whose employees include people with technical and scientific training, not political and business connections.

This becomes more important with the rising seas caused by global warming.

Save the Bay, the state’s leading environmental advocacy organization, has been denouncing state leaders for slashing the DEM’s staff, especially inspectors and enforcement officers.

“The Department of Environmental Management has seen its budget and staff cut dramatically over the past 20 years. These cuts have led to delays in permitting, reduced inspections of potential polluters, and lax enforcement of RI’s environmental laws and rules,” said Jed Thorp, advocacy coordinator of the organization.

Hit this link for more information.

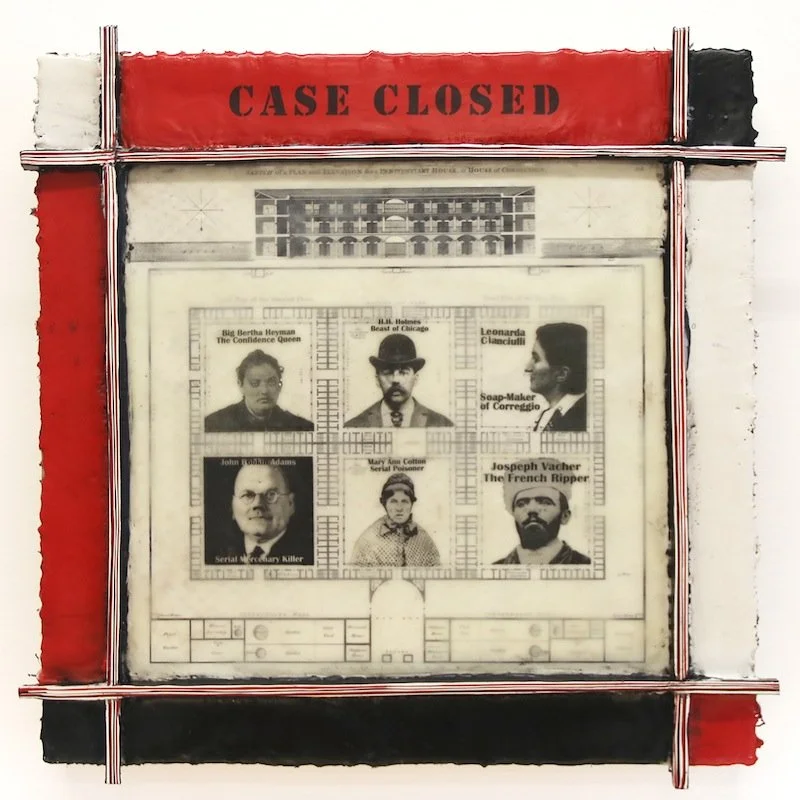

Creative criminals of yore

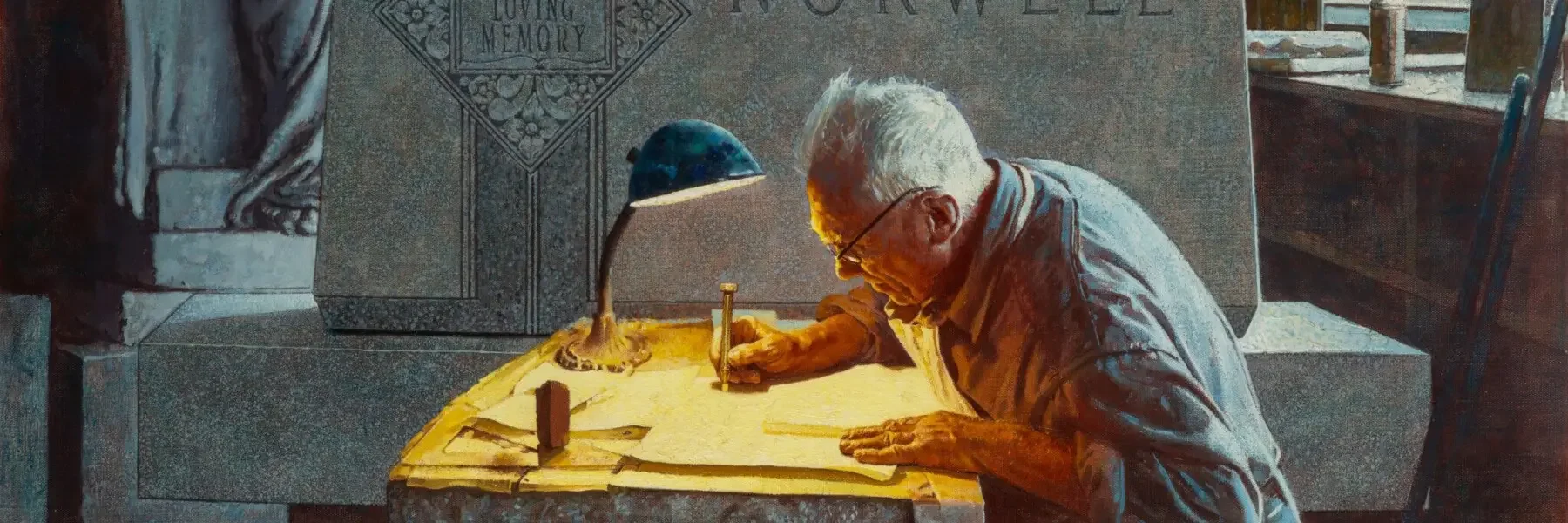

“Case Closed” (encaustic with image transfers), by Providence-based artist Angel Dean. She is a member of New England Wax (newenglandwax.com)

Linda Gasparello: Millennials can be pioneers in cities with cheap houses

In Danville, Va., home of tobacco entrepreneur William T. Sutherlin, called by locals the "Last Capitol of the Confederacy.’’ But most houses there don’t look like this!

WEST WARWICK

Millennials are supercharging the U.S. housing market. They have lots of cash, and they’re making a dash for cities like Boise, Idaho, Raleigh, North Carolina, Tampa, Florida, and Austin, Texas.

As home-mortgage rates rise and inventory shrinks in those and other A-list cities, Millennials, particularly those who can work remotely, might want to consider C-list – C for cheap -- cities.

Hey, Millennial. Don’t be bummed about being outbid for that pricey “adorable vintage house within walking distance to entertainment” in Austin (actually, a teardown with a honky-tonk a few yards from the back porch). Be cheered that Wall Street 24/7, a news and financial site, has just released a special report entitled “The Cheapest City to Buy a Home in Every State.”

If you’re a pioneering Millennial, here are a few cities in the report:

Gary, Ind., could be “your home sweet home” -- just like the line from the song in The Music Man, which was a hit on stage and screen long before you were born. The median home value is $66,000. Cheap homes abound in this not-so-cheerful city.

Flint, Mich., The fact that you can’t drink the water is no problem for you because you’ve only ever drunk bottled water. The median home value is $29,000. If you decide to buy a home there, keep buying bottled water from fresh municipal springs -- in other states.

Camden, N.J. There is great news for home buyers. Trenton has taken the “Murder Capital of New Jersey” title away from Camden, a perennial titleholder. The median home value in Camden is a bargain $84,000 versus $335,600 for New Jersey as a whole. Camden is downriver from Trenton, so mind the floating corpse risk.

Minot, N.D. It’s a hot market: the median home value is $208,700 versus $193,900 for the state. As for temperature, it’s not. I had a school friend from Minot who told me the saying there was, “Why not Minot? Because freezing is the reason.” Look at those months of frigid temperatures as being the reason to get more wear out of your chichi Canada Goose Expedition Parka.

East St. Louis, Mo. One resident, in a review on the Niche site, wrote, “I didn't like all of the abandoned homes and buildings. It looked like the area isn't livable and then two houses down, it is livable.” The Niche reviewers give the city bad marks for violence, but great ones for the high school football team and the diners. The median house value is $54,000.

The city that really caught my eye in the report was Danville, Va. – in a state where I lived for most of my life.

For years, because I’m interested in architecture, I’ve pored through listings on historic house sites. Recently on one site, there were many dilapidated Victorian houses listed in Danville’s Old West End, priced from $15,000 to $55,000.

For much of its history, Danville was a D-list city – D for disreputable. This tobacco-processing and textile-manufacturing city’s reputation rolled downhill for a century, from the Civil War (where it was major center of Confederate activity and was the “Last Capital of the Confederacy” from April 3-7, 1865) to “Bloody Monday,” the name given to a series of arrests and brutal attacks that took place during a nonviolent protest by Blacks against segregation laws and racial inequality on June 10, 1963. Of the protests, leading up to the March on Washington on Aug. 28, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. preached, “As long as the Negro is not free in Danville, Virginia, the Negro is not free anywhere in the United States of America.”

Danville’s work in recent decades to create a new identity is paying off. The median home value is $90,500. The city is attracting high-tech companies and Millennial workers – new residents who will continue its transformation from disreputable to desirable.

Linda Gasparello is co-host and producer of White House Chronicle, on PBS. Her email is lgasparello@kingpublishing.com, and she’s hased in West Warwick, R.I. and Washington, D.C.

Good place to work

“The living room he took me into was neat, cozy, and plain: a large circular rug, some slipcovered easy chairs, a worn sofa, a long wall of books, a piano, a phonograph, an oak library table systematically stacked with journals and magazines. Above the white wainscoting, the pale-yellow walls were bare but for half a dozen amateur watercolors of the old farmhouse in different seasons. Beyond the cushioned window seats and the colorless cotton curtains tied primly back I could see the bare limbs of big dark maple trees and fields of driven snow. Purity. Serenity. Simplicity. Seclusion. All one’s concentration and flamboyance and originality reserved for the grueling, exalted, transcendent calling. I looked around and I thought, This is how I will live.’’’

From Philip Roth’s 1979 novel The Ghost Writer. The passage was inspired by Roth’s time at his estate in Warren, Conn., where the novelist wrote some of his most important novels.

Robert P. Alvarez: The filibuster assaults democracy

The filibuster hamstrings the “pluribus’’

From OtherWords.org

If you’re under the impression that the filibuster is an important tool in the toolbox of American democracy, you’ve been misled.

The filibuster is a made-up Senate convention that lets a minority of senators block votes on bills that have majority support. Under current rules, just 41 senators can sink legislation this way.

In the past, filibusters were used only rarely. But with Republicans filibustering virtually everything these days, it now takes 60 Senate votes to pass anything at all. That’s a tall hurdle in our polarized age.

The main argument for the filibuster is that it promotes bipartisanship and debate, but research has repeatedly debunked that.

According to supporters, allowing a minority of senators to extend deliberation on a bill indefinitely forces the majority to negotiate a version that the minority feels more comfortable with. This leads, supporters contest, to legislation that appeals to the broadest number of people.

That sounds nice. But peel back the onion a bit and it’s clear that the filibuster just adds to the gridlock around issues voters want resolved.

A new University of Chicago study, for example, found that the filibuster did not “enhance the Senate’s consideration of laws.” Instead, “the filibuster detracts from, rather than bolsters, public discussion on the floors of Congress.”

This makes sense. Why would a committed minority debate or compromise on a bill they can simply kill altogether?

In Republicans’ case, it means that they can stop Democrats — who won control of the House, Senate, and presidency in the 2020 election — from delivering the policies they promised. As a result, popular ideas such as voting rights, police reform, immigration reform and an independent commission to investigate the Jan. 6th insurrection are all getting stonewalled.

It gets even worse when you factor in that the Senate already over-represents less populated and often more conservative states. According to one figure, senators representing just over 20 percent of the country can block legislation that even overwhelming majorities of voters want.

As you might imagine, this has made the filibuster a powerful political weapon, which unfortunately has been used to cause harm — particularly in the area of civil rights.

A group of Southern senators in 1922, for instance, used it to kill a bill that would have let the federal government prosecute people who participated in lynchings. Years later, South Carolina Sen. Strom Thurmond famously filibustered for over 24 hours straight, the longest individual filibuster ever, to try to tank the Civil Rights Act of 1957.

More recently, Republicans have used the filibuster to block major voting rights bills such as the Freedom to Vote Act and the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, which would have strengthened election security and made it easier to vote.

These voting rights bills were filibustered in a time of rising voter suppression. According to the Voting Rights Lab, 385 bills that restrict voter access have already been introduced in 2022 alone.

Most Democrats now agree that the filibuster needs to be eliminated or reformed. But two of their own, Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema, have joined Republicans in defending the practice. Both recently voted against making a “voting rights exception” to the 60-vote threshold.

They could have kept their commitment, however misguided, to the filibuster while still voting to make a one-off rules tweak to bring the voting rights bills up for a vote. This would have treated voting rights the same way as judicial confirmations and budget reconciliations, which can’t be filibustered.

Is there hope for filibuster reform in the future? I think so.

Manchin and especially Sinema could face primary challengers when they’re up for re-election in a few years, and support for the filibuster is likely to be a line in the sand for voters. Alternatively, if Democrats expand their Senate majority, they may be able to reform the filibuster even without those two.

Either way, the days of the filibuster appear limited.

Robert P. Alvarez is a media relations associate at the Institute for Policy Studies.

Harris Meyer: Resistance to Mass General Brigham expansion centers on fear of higher prices

MGH Brigham complex in Foxboro, Mass.

— Photo by Patriot-place

A boisterous political battle over a proposed expansion by the largest and most expensive hospital system in Massachusetts is spotlighting questions about whether similar expansions by big health systems around the country drive up health-care costs.

Boston-based Mass General Brigham, which owns 11 hospitals in the state, has proposed a $2.3 billion expansion, including a new 482-bed tower at its flagship Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston and a 78-bed addition to Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital. The most controversial element, however, is a plan to build three comprehensive ambulatory-care centers, offering physician services, surgery and diagnostic imaging, in three suburbs west of Boston.

On Jan. 25, the state’s 11-member Health Policy Commission unanimously concluded that these expansions would drive up spending for commercially insured residents by as much as $90 million a year and boost health- insurance premiums.

The commission also ordered Mass General Brigham to develop an 18-month “performance improvement plan” to slow its cost growth. The action, believed to be the first time in the country a hospital has been ordered to develop a plan to control costs, reflects concern about giant hospitals’ role in rising health care costs.

Other states, including California, Delaware, Oregon, Rhode Island and Washington, have created or are considering commissions on health care costs with the authority to analyze the market impact of mergers and expansions. That’s happening because the traditional “determination of need” process for approving health facility expansions, which nearly three dozen states still have in place, has not been effective in the current era of health system giants, said Maureen Hensley-Quinn, a senior program director at the National Academy for State Health Policy.

The Mass General Brigham health system, which generates $15.7 billion in annual operating revenue, announced that the massive expansion would better serve its existing patients, including 227,000 who live outside Boston. Its leaders said the new facilities would not raise health spending in the state, where policymakers are alarmed that cost growth in 2019 hit 4.3%, exceeding the state’s target of 3.1%.

The hospitals’ cost-analysis report, submitted to the state last month, concluded that the system’s existing patients would pay lower prices at the new suburban sites than at its downtown locations. John Fernandez, president of Mass General Brigham Integrated Care, projected that prices at the new centers would be 25% less, and he said patients will not have to pay extra hospital “facility fees” at the new outpatient sites.

“We’re all going to have a tsunami of patients over the next 20 years given the aging population, and everyone has to step up to meet that demand,” he said in explaining the expansion.

But a well-funded coalition of competing hospitals, labor unions and chambers of commerce argues that Mass General Brigham’s invasion of the Boston suburbs would spike total spending by drawing in patients from lower-priced physicians and hospitals. They cite the health system’s own planning projection, unearthed by the attorney general’s office in a November report, that the expansion would boost annual profits by $385 million.

Dr. Eric Dickson is CEO of UMass Memorial Health Care, a safety-net health system serving the towns west of Boston that is part of the coalition of opponents to Mass General Brigham’s expansion plans. “If you let the state’s most expensive system grow wildly, it will drive up the cost of care,” he says.(UMASS MEMORIAL HEALTH CARE)

“How could you be fooled?” said Dr. Eric Dickson, CEO of UMass Memorial Health Care, a safety-net health system serving the towns west of Boston that is part of the coalition of expansion opponents. “If you let the state’s most expensive system grow wildly, it will drive up the cost of care.”

The controversy signals a shift in the concerns about the cause of rapidly escalating health care costs. Up to now, state and federal policymakers examining how hospital system growth affects costs have largely focused on hospital mergers and purchases of physician practices. Studies have found that these deals significantly boost prices to consumers, employers, and insurers. State and federal regulators have stepped up antitrust scrutiny of mergers and acquisitions.

Deep-pocketed hospital systems increasingly are turning to solo expansion to gain a bigger share of the market. These expansions fall outside the legal authority of antitrust enforcers.

Health systems are building satellite ambulatory care centers to attract more well-insured patients and steer them to their own hospitals and other facilities, said Glenn Melnick, a health economist at the University of Southern California.

“The outcome is the same as a merger — capturing patients and keeping them,” he said. “That’s not necessarily good for consumers in terms of access to care or cost efficiency.”

Critics of Mass General Brigham’s plans also warn that the expansion would financially destabilize providers that heavily serve lower-income and minority residents because some of their more affluent patients would move to the new facilities. Those patients’ commercial insurance plans pay nearly three times what the state’s Medicaid program pays.

“It’s a very, very good business move for MGB,” said Dickson, whose system serves a large percentage of Medicaid patients. “But they know quite well this will impact our ability to care for vulnerable populations.”

The Health Policy Commission agreed with those opposing the expansion and said it would advise the state Public Health Council — which will decide on the three expansion applications by April — that the proposals are not consistent with the state’s goals for cost containment.

“Our strong assessment is this would substantially increase spending,” said Stuart Altman, a health policy professor at Brandeis University who chairs the commission. In addition, “there is a clear indication it would reduce revenues to those institutions we count on to provide services to lower-income and historically marginalized communities.”

In a written statement, Mass General Brigham ripped the commission’s findings as flawed. It also disagreed with the commission’s decision to require a cost-improvement plan but said it would work with the agency to address the challenge.

Under Massachusetts’s determination of need process, Mass General Brigham must show the Public Health Council that its expansion proposals would contribute to the state’s goals for cost containment, improved public health outcomes, and delivery system transformation.

The council has never blocked a project on cost grounds in its nearly 50-year history, said Dr. Paul Hattis, a former member of the Health Policy Commission. He argues that Massachusetts needs more explicit statutory power to decide whether health system expansions are good for the public, because he doesn’t think the council understands its own regulation.

A bill passed by the Massachusetts House of Representatives last fall would give the commission, which was created in 2012, greater authority to investigate the cost and market impact of such expansions. Its legislative fate is uncertain.

Upping the stakes in the Massachusetts expansion fight: Massachusetts General Hospital charges by far the highest prices in the state, and Brigham and Women’s Hospital isn’t far behind.

Patients with a Mass General Brigham primary care physician had the highest total per-member spending in 2019, nearly $700 per month, according to the Health Policy Commission. That was 45% higher than spending for patients served by doctors at Reliant, which is owned by UnitedHealth Group’s Optum unit. Average payments for major outpatient surgery at Massachusetts General and Brigham and Women’s were nearly twice as high as at the state’s lowest-paid high-volume hospital.

Harris Meyer is a Kaiser Health News journalist.

Harris Meyer: @Meyer_HM

Promise joy, build it and get out of town with a big profit

Polar Park, in Worcester. The local company Polar Beverages bought the naming rights.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I suppose we can mostly blame the pandemic, but revenue hasn’t looked all that rosy at the Worcester Red Sox’s new Polar Park, which, as with most such stadium projects, has received many millions in public dollars that benefit the investment group that owns the team. But then, even in pandemic-free times, rarely do such facilities pay off for the taxpayers, although pro sports fans and grandiose promises of local economic gains often overcome strenuous community opposition to these projects.

Study after study by economists finds that these are crummy investments in terms of taxpayer dollars.

A campaign by the same group for a new, taxpayer-subsidized stadium in Pawtucket as a home for the now deceased PawSox failed, and considering what’s happening in Worcester, there may be many fresh sighs of relief in Rhode Island. That’s not to say that there are not psychic benefits from having a local baseball team. (We enjoyed taking guests from out of town, especially foreigners, to PawSox games.)

But wait! The WooSox owners may well sell the team sooner than you might think, and at a big profit. Call this welfare for the rich, or just the American Way!

Slung along the sound

Long Island Sound from Calf Pasture Beach in Norwalk, Conn.

“Catechist of gnarled oak trees, marshes, small suburban marinas,

cinders, and gutted mattresses, I let myself be slung

along tracks from one city toward another. Stain

of rose water where the Sound remembers the sun….’’

From “Northeast Corridor,’’ by Rosanna Warren (born 1953), daughter of the novelist and poet Robert Penn Warren, she grew up in Connecticut.

Exterior freedom

“Liberation” (photo) by Eileen McCarney Muldoon, a Rhode Island-based fine-art photographer, in the Providence Art Club’s “Winter Member’ Exhibition,’’ through Feb. 10. This picture won the “Best of Show’’ prize.

Frank Carini: Invasive plants are winning in R.I.

Japanese barberry in Penwood State Park, in Connecticut

— Photo by Sage Ross

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

This intrusive plant was brought to the United States from Japan and eastern Asia in the late 1800s. The ornamental is still used in residential and commercial landscapes because of its fall coloring and deer resistance. But the prickly shrub easily spreads into woodlands, pastures and meadows, where, like many invasives imported from faraway lands, it chokes out native species.

Japanese barberry can also be popular with ticks. A multiyear study conducted in Connecticut looked at the relationship between the deciduous shrub, white-tailed deer, white-footed mice, and deer ticks, also known as black-legged ticks. It found that the larger amount of barberry in an area, the higher the prevalence of deer ticks, which can carry Lyme disease.

The hearty species, which can grow up to 6 feet tall, has denser foliage than most native species and, as a result, the invasive bush retains higher humidity levels that ticks crave, according to the study published in 2010. The shrubs also provide nesting areas for white-footed mice, which are a main source for larval ticks’ first blood meal.

Follow-up research in 2011 found that barberry-infested forests are about 12 times more likely to harbor deer ticks than forests without barberry.

This past fall Pennsylvania became the most recent state to include Japanese barberry on its list of invasive plants that can’t be legally sold or cultivated. The sale of the multi-stemmed shrub with needle-sharp spines has been banned in Massachusetts since 2009 and in New Hampshire since 2007. The sale of the plant is also prohibited in Maine and Vermont.

Connecticut recognizes it as an invasive, but nurseries there can grow and sell it. Connecticut does prohibit the sale of other plants on its invasive species list, but barberry is popular and the nursery industry lobbied against a ban. Big-box stores are still selling it, even after the Connecticut Nursery & Landscape Association agreed to phase out the most invasive barberry plants.

The sale of barberry is allowed in Rhode Island. In fact, the Ocean State is the only New England state that doesn’t have a complete list of noxious plants. While the other five states have a long list of invasive species that are banned or at least identified in Connecticut’s case, the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s invasive plants webpage notes the damage inflicted by non-native species but only mentions one: phragmites, which aren’t sold at nurseries and garden centers.

“For more information and resources about invasive plant species in Rhode Island,” the state’s environmental agency directs those interested in the problem to a broken link on the website of the Rhode Island Natural History Survey, a small nonprofit that over the years, as DEM staffing and funding have been cut, has become increasingly relied on to help protect the local environment.

The organization’s executive director, David Gregg, said the Natural History Survey and others have been working since the early 2000s to get Rhode Island to at least create a list of invasive plants that should be avoided, such as burning bush, privet and Japanese barberry.

Those efforts have continually stalled, thanks in part from pushback from lobbyists representing nurseries, garden centers and growers who have developed their businesses based on consumer demand.

This snarl of oriental bittersweet has climbed into trees along a roadside in Portsmouth, R.I.

— Photo by Frank Carini/ecoRI News

Shannon Brawley, executive director of the Rhode Island Nursery & Landscape Association (RINLA), said the organization favors a list but wants the industry to have a significant say in what species are listed or banned.

“We have to make sure we’re not collapsing someone’s business by outlawing particular plants,” she said. “It takes a long time to grow them. Nurseries are growing it and then they have to tear out acres and acres of product, and it takes five to eight years to grow something else to sell. If it’s not done carefully, there’s going to be an economic impact on these businesses.”

Gregg said if that is the case then there needs to be a plan to deal with the issue of economic hardship. But maintaining the status quo, he added, can’t be an option.

Like many other non-native species, Japanese barberry can tolerate a range of site and soil conditions, which means, like multiflora rose, oriental bittersweet and autumn olive, it comes to dominate the landscape, and can change soil chemistry.

Common barberry, a European invasive first brought to this country during the 17th Century, is shade-tolerant, which allows it to easily invade woodlands. It can reach a height of 13 feet.

Barberry, like other ornamentals brought in from overseas, spreads from home and commercial gardens to open spaces and areas that have been disturbed, such as roadsides. Barberry produces a lot of seeds and has a high germination rate. Its seeds aren’t very nutritious for wildlife, but they are eaten anyway and deposited in more areas, where more of the invasive becomes established — part of a larger cycle that is crowding out native plants, destroying habitat, and starving native insects and wildlife.

Tangles of bittersweet, forests of burning bush and heaps of multiflora rose mar much of Rhode Island’s landscape.

“Invasive species are the second-greatest threat to biodiversity after development when it comes to areas of habitat they wipe out,” Gregg said, “It’s what wrecks the outdoor experience for people who want to relax in green space. There’s a crack ton of it. It’s a physiological and cultural problem, as well as an environmental and economic one.”

He noted that both sides of the East Bay Bike Path from end to end are full of invasives. “Good luck getting a view of the water. It’s like going through a tunnel of phragmites.”

Brawley noted she gets out-of-state phone calls from people looking to buy burning bush because of its intense red foliage. She provides them with native alternatives that are similar but don’t suffocate woodlands and coastal scrublands.

“I couldn’t in good conscience recommend the purchase of this plant,” said Brawley.

She said most Rhode Island nurseries and garden centers don’t sell burning bush, or if they do, it’s a sterile variety.

Burning bush was introduced to the United States in the mid-1800s as an ornamental plant for use in landscaping. The sale of it is prohibited in Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Maine, and the invasive is on watch lists in Connecticut and Vermont.

— Photo by Chris Barton/Gif absarnt

Douglas Tallamy, a University of Delaware entomologist and author of Bringing Nature Home: How You Can Sustain Wildlife with Native Plants and Nature’s Best Hope: A New Approach to Conservation That Starts in Your Yard, has been researching and writing for years about the threat invasives pose to native insects and wildlife habitat.

His work has shown that the transformation of native plant communities into landscapes dominated by imported species and lawns imperil insects, most notably caterpillars, and the birds and other animals that depend on them for survival.

A paper he co-authored in 2020 reviewed the research supporting the theory — which has had its detractors — that the widespread displacement of native plant communities by non-native species is contributing to insect decline. It found that our longtime fascination with ornamentals over native plants is degrading the local environment.

Japanese knotweed can grow 3 inches a day and reach 10 feet in height. Oriental bittersweet can climb to 60 feet, strangling host trees. Tree-of-heaven can reach a height of 80 feet and grow to be 35-50 feet wide. Glossy buckthorn can colonize without disturbance, and its dense foliage and ability to mature quickly allows it to easily outcompete native plants. Extensive stands of it can also produce conditions favored by deer ticks.

These four invasives and most others don’t have natural predators feeding on or killing them. The vast majority of native insects can’t eat or reproduce on these invaders — native plants and insects co-evolved over thousands of years — creating a food desert for invertebrates and the birds and animals that feed on them. They provide little support for pollinators.

Many of the worst invasives strangling Rhode Island, such as bittersweet, knotweed and glossy buckthorn, are no longer sold, but the lack of diversity created by the totality of the state’s invasive species problem, including the continued sale of many intrusive plants, makes the local environment much less resilient, by leaving it, for example, with fewer options when responding to the climate crisis.

The continued sale of invasives is directly tied to consumer demand and the Rhode Island landscape and nursery industry responding to those wants.

Catherine Weaver, a RINLA board member and past president who owns a North Kingstown-based landscape design studio, said her clients often request miscanthus, also known as Chinese silvergrass, a popular ornamental grass she called “a nuisance.” Hedges of invasive privet are also a high-demand request by her clients. She called privet “a nasty invasive,” and said she instead recommends the use of natives like sweet pepperbush or viburnums.

“We need to prioritize environmental integrity over aesthetics,” Weaver said, “but we’re so used to using aesthetics to judge if a plant is good. Planting something beautiful is pleasing … but we have to use other criteria when we’re making these decisions. We shouldn’t be sacrificing ecosystem function for beauty. We can have both. There are so many great native plants.”

Both Weaver and Brawley said the public needs to be better educated about the importance of native plants to create more demand. They believe progress is being made on that front, albeit slowly.

“Five clients in the past year have asked for mostly native plants,” Weaver said. “That almost never happened before.”

Not every non-native species is invasive, however. Invasives are those that, reproducing outside their native range, actively cause ecological or economic harm, according to the Invasives Species Act of 1996.

Species exchange is natural, as there has always been drift — plants moving with the tides and seeds scattered by birds and storms. Ecosystems change over time. Early humans brought hitchhikers with them as they migrated. But comparatively, today’s invasive species levels are monstrous, because of growing human globalization, including two-plus centuries of importation of ornamentals from exotic places to show off wealth and later to keep up with the Joneses.

In Rhode Island, the limited amount of attention being paid to invasive plants is largely focused on aquatic invaders, which interfere with boating, paddling, fishing and other recreational activities. More than 100 lakes and 27 river segments in Rhode Island are plagued with at least one species of invasive plant, according to DEM.

The agency’s webpage for aquatic invasives includes a list of the problem species. Many only need a couple of cells or a leaf to reproduce. They can take over a waterbody quickly.

In its 2020 fishing regulations, DEM prohibited the transport of invasive plants on any type of boat, motor, trailer or fishing gear to help prevent the inadvertent movement of aquatic invasives from one waterbody to another.

DEM also has proposed regulations to ban their sale, purchase, importation and distribution. The proposed regulations list 48 species of aquatic invasive species whose sale would be prohibited, such as Carolina fanwort, a problem species in Smithfield’s Stump Pond; American lotus, which covers 18 acres of Chapman Pond in Westerly; Brazilian waterweed, which has invaded Hundred Acre Pond in South Kingstown; and common water hyacinth, an Amazonian species now found in the Pawcatuck River.

DEM’s proposal to limit aquatic invasives is still under review, according to an agency spokesperson. Enacting the proposal doesn’t require enabling legislation.

Gregg said Rhode Island should be taking the same precautions when it comes to terrestrial invasives, as they inflict as much damage to the environment and local economy. He noted the fact Rhode Island hasn’t banned the sale of many invasives or even bothered to compile a complete list doesn’t paint the state as very neighborly.

He said it was also unfair that as taxpayers fund efforts to eradicate invasives, nonprofits create programs to battle their spread and volunteers spend their free time cutting and pulling them from the landscape, their local garden center is selling more intrusive non-natives to be unwittingly planted at homes and businesses.

“We’re spending good money and time removing invasives from the woods to maintain the status quo,” Gregg said. “It would make more sense to have a regulation that banned the sale of these plants.”

Gregg offered a solution: remove the word “aquatic” from DEM’s invasive plant proposal.

“It’s pretty clean and simple,” he said. “Delete a single word and create an invasives species list.”

A bill filed last year would have done just that, making it illegal to import, transport, disperse, distribute, introduce, sell or purchase in the state any invasive plant species.

Black swallow-wort, an invasive vine from Europe, reproduces by sprouting new stems from existing roots and by spreading seeds. Inside this seed pod are thousands of seeds that will float on the wind or hitch rides on animals to other areas. Removing and disposing of seed pods before they open is one way of slowing the spread of this invader. (ecoRI News)

Two years earlier, in 2019, the Protection From Invasive Plant Species Act would have prohibited the planting of running bamboo within 100 feet of a property line. The fast-spreading invasive can penetrate asphalt and the siding of buildings. Many homeowners, not knowing the unintended consequence, plant running bamboo as a natural barrier that offers privacy and blocks out animals such as deer. But some bamboo species can grow 40 feet high and their roots can travel 15 feet in a year.

Violators would have been liable for the cost of removing the plant from a neighbor’s property, plus any damages. Rhode Island retailers and landscapers would have been required to provide customers written notice of the risks of running bamboo.

To address other non-native invaders, the legislation would have required DEM to create a list of invasive plant species, regulate their sale and enforce compliance.

DEM, however, was opposed to the legislation. The state agency said it already regulates invaders and can assess fines of up to $500 for transporting invasive aquatic plants. It noted it doesn’t allow federally designated noxious weeds to enter the state. The U.S. Department of Agriculture list doesn’t include Japanese barberry, privet or burning bush. It doesn’t even include multiflora rose, oriental bittersweet or phragmites.

The Rhode Island Farm Bureau feared the bill would punish farmers for invasive species they didn’t actually plant. It suggested the state — that is, taxpayers — instead offer money to farmers and property owners for the removal of invasive plants, of which some were likely bought in Rhode Island and planted by the current landowner.

Like past attempts to tackle the problem of invasive plants, such as the 2021 bill that would have removed the word aquatic, the Protection From Invasive Plant Species Act didn’t go anywhere.

Since the state seems unwilling to address the problem, Gregg said the key to reducing the impact of invasives is educating the public about the environmental harm many non-native plants cause.

“It’s in the public’s interest that we grow the right plants,” he said. “The importance of native species has come a long way in the past 15 years, but we need an invasive species list so we can have conversations that educate the public and bring awareness to the problem. It’s a complex issue, but at the end of the day we’re spending money to remove stuff people are buying at garden centers.”

Frank Carini is senior reporter and co-founder of ecoRI News.

David Warsh: How America can get out of its political mess

Not much “unum’’ lately

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The end of Joe Biden’s difficult first year in office evoked all kinds of comparisons. New York Times columnist Bret Stephens recalled successful presidential partnerships with strong chiefs of staff – Ronald Reagan and Howard Baker, George H.W. Bush and James Baker. Stephens asked, “What’s Tom Daschle up to these days?” Nate Cohn, also in The Times, compared Biden’s legislative strategy to that of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933, to Biden’s disadvantage. I asked a friend who has known Biden for forty years.

I don’t think you can pin the things that Bret Stephens doesn’t like about the Biden presidency on the staff…. Is Biden missing someone who could talk him out of bad calls? Could a Tom Daschle serve as a keel for Biden the way Leon Panetta did for Bill Clinton? … Doubtful. Think back on how Biden ran his campaign in 1987 and in 2020: lots of cooks in the kitchen. The only one he really trusted was his sister. He delegated authority to nobody. His campaigns were organizational [smash-ups]. Some people never change. At least his heart is in the right place.

Myself, I thought of the two-year presidency of Gerald Ford. The common denominator is that both Ford and Biden had to deal with long national nightmares.

As president, Ford had it easy. After 25 years as a Michigan congressman from Grand Rapids, Republican minority leader for the last nine of them, he was the first political figure to be appointed vice president, under the terms of the 25th Amendment. Vice President Spiro Agnew resigned in October 1973, having plead guilty to a felony charge of tax evasion. Ford succeeded him in December. When Richard Nixon resigned the presidency in August, 1974, after an especially damaging White House tape recording was released, Ford was sworn in.

In his inaugural address, Ford stated “[O]ur long national nightmare is over. Our Constitution works; our great republic is a government of laws and not of men.” A month later he pardoned Nixon for any crimes he might have committed as president. Nixon’s acceptance was widely viewed as tantamount to an admission of guilt, and the former president withdrew from public life pretty much altogether. Ford’s two years in office were a stream of politics as usual. Disapproval of the pardon weighed against him; so did the fall of Saigon, in April 1975. He ran for the presidency in 1976, but was defeated by Jimmy Carter, governor of Georgia.

As president, Biden faces almost the opposite situation. First, Trump lost the 2020 election, which he then falsely claimed he had won, Next, he apparently sought to interfere with the vote of the Electoral College, for which he is now under investigation. He continues to interfere in Republican primaries, and has threatened to mount a second presidential campaign. Meanwhile, much of Biden’s ambitious legislative agenda has bogged down and his popularity has dwindled in public opinion polls.

What chain of events will allow some future president to pronounce a benediction on the Trump nightmare? My hunch is that a relatively moderate Republican with no previous ties to Trump can be elected, possibly in 2024; if not, in 2028. That is easier said than done. The problem is getting by the Republican convention. It all depends in large measure on the results of the mid-term elections; on the Republican primaries in 2024; and on Biden’s standing at the end of his term, when he will be 82 years old. .

Republican contenders are already edging away from Trump, Gov. Glenn Youngkin, in Virginia; Gov. Ron DeSantis, in Florida. It is not necessary to disavow Trump’s political platform, if anyone besides Joe Biden remembers what it was – less supply-chain globalization; more domestic infrastructure investment; immigration reform (whatever that is!); recalibration of foreign relations, China and Russia in particular. All these positions are capable of commanding support among independent voters

It is Trump himself whose character must be thoroughly rejected. That will happen by degrees. There will be no pardon this time. The next president, whoever it is, will continue to leave matters up to the courts. And, sooner or later, the lingering nightmare will end.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

Chris Powell: Democrats miss this big tax break for the rich

Looking northward from Saugatuck Cribari Bridge, in Westport, Conn., one of Fairfield County’s rich towns.

— Photo from WestportWiki

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont and state Atty. Gen. William Tong, both Democrats, are pressing in federal court to restore a lucrative tax break for the rich. But somehow they are escaping criticism from those in their party who clamor for taxing the rich more.

The governor and attorney general have asked the U.S. Supreme Court to hear the appeal of Connecticut and other states that claim that it is unconstitutional for the federal tax code to limit to $10,000 the annual deductibility of state and local taxes -- the SALT cap.

The SALT cap may have been the only liberal change to the federal tax code enacted during Donald Trump's administration. Anyone who pays more than $10,000 a year in state income and local property taxes is doing pretty well. Indeed, most of the benefits of lifting the SALT cap would go to the very wealthy.

Lamont and Tong claim that the SALT cap violates state's rights -- that it interferes with Connecticut's tax system. But it doesn't. The cap just reduces the federal government's subsidy to high-tax states.

Acknowledging as much, a federal district court and a federal appeals court have already rejected Connecticut's case and the Supreme Court almost certainly will do so too.

The governor and attorney general claim that the SALT cap was "politically motivated," since the high-tax states are Democratic and the cap was imposed by a Republican national administration. But of course nearly everything in government is politically motivated to some extent, political motivations are not unconstitutional, and many principled Democrats acknowledge that the SALT cap is fairer than the previous policy, unlimited deductibility of state and local taxes.

The Lamont administration's appeal of its defeat in the two lower federal courts is politically motivated too -- doubly so.

First, the administration wants to prevent Connecticut's high-tax policy from aggravating the state's many wealthy residents who lately have been voting and contributing Democratic, especially in Fairfield County, where many people find Trump repugnant and may not vote Republican again while the party is in thrall to the former president.

Since the SALT cap makes state and local taxes more burdensome, wealthy people who have lost the federal deduction may start resenting high state and local taxes more. If Republicans can free themselves of Trump, those people may transfer their disdain to the special interests that consume so much state and local government revenue and are the core of the Democratic Party in Connecticut.

And second, with its appeal against the SALT cap the Lamont administration rides an issue that might rile up those Democratic special interests as a state election approaches. By pressing the appeal, the administration tells those special interests that it is striving behind the scenes to protect high taxes so that those special interests remain well-compensated, even as the governor, when being watched more closely, tries to restrain taxes.

The SALT cap also makes hypocrites of Connecticut's members of Congress, all Democrats who advocate repeal of the cap even as they complain about other tax breaks for the rich. But if a federal tax break for the rich helps keep Connecticut a high-tax state more able to sustain the Democratic Party's army, the delegation will suspend its supposed principles.

xxx

Connecticut law requires public high schools to offer a course in Black and Latino studies, and the other day two students at Trinity College in Hartford wrote an essay for the Connecticut Mirror calling for schools to be required to offer a course in Asian-American studies as well.

While there is much to be learned in these subjects, they are best incorporated into U.S. history courses. Separated, ethnic studies will crowd out general history, which is already neglected.

And while the law requires high schools to offer the Black and Latino studies courses, it doesn't require students to take them. Presumably it would be the same with an Asian-American studies course -- more politically correct but oblivious posturing even as most Connecticut high school students, enjoying social promotion, graduate without ever mastering English and math.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

For an all-powerful speaker

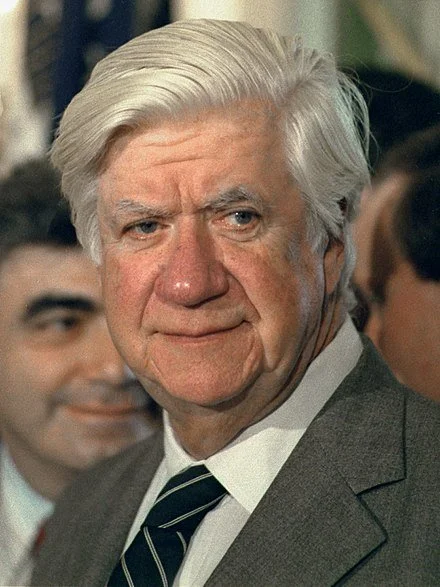

Tip O’Neill in 1978

“I think the speaker of the House in Congress should be like the Massachusetts speaker: all-powerful. He should appoint committee chairmen and remove them if they stray from the party line. He should be answerable only to the caucus, which can remove him at any time. I'd throw the seniority system out on its ear in Congress.’’

— Thomas P. (“Tip”) O’Neill Jr. (1912-1994), New Deal-style Democratic who served as speaker of the Massachusetts House (1949-1953) and speaker of the U.S. House (1977-1987). He was known for his FDR-Truman-style liberalism, pithy political sayings, most notably “All politics is local,’’ and impressive nose.

His district was centered around the northern part of Boston.

Autumn in the Alewife Linear Park, near the corner of Cedar Street and Massachusetts Avenue, North Cambridge — Tip O’Neill’s neighborhood

The hanging of the green

“Slip” (thread, day glow paint and monfilament), by Marilu Swett, in her show at Boston Sculptors Gallery, Feb. 23-March 27.

The artist, based in Boston’s Jamaica Plain neighborhood, tells the gallery:

“My sculptures and drawings allude to natural systems and subsystems, microscopic, telluric and oceanic form, the human body, and industrial artifacts. I have lately been looking at the ocean and its littoral variety with pleasure and concern, with a strong interest in our history with and debt to it. My recent work reflects my musings. I cast, draw, scrub, carve, cut, tool, dye and paint materials to produce complex drawings and forms in plastic, resin, lead, bronze, rubber and mixed media. I sometimes include found objects. The work is serious and fanciful, abstracting, inventing, and drawing relationships among forms."

Soldier's Monument and First Unitarian Universalist Church in Jamaica Plain

Skating in Jamaica Plain, by Winslow Homer, 1859. The community, a part of the town of West Roxbury for a while, became part of Boston when the city annexed West Roxbury in 1874.

‘Like an ox’s breath’

— Photo by kallerna

— Photo by Vid Pogacnik

“But what would interest you about the brook,

It's always cold in summer, warm in winter.

One of the great sights going is to see

It steam in winter like an ox's breath,

Until the bushes all along its banks

Are inch-deep with the frosty spines and bristles--

You know the kind. Then let the sun shine on it!"

— From “The Mountain,’’ by Robert Frost

‘The local idiom’

— Photo by Kenneth C. Zirkel

“I wait the proper bus, and, waiting,

hear my name called in sudden greeting —

and my own responses come

apt in the local idiom.’’

— From “Journey,’’ by Constance Currrier (1908-1991). Besides being a highly productive poet, she taught Latin in West Hartford and New Britain, Conn. She was born and raised in New Britain, which for many years as a major manufacturing center.