Boston too ‘refined’?

Boston Latin {High} School was established in 1635 and is the oldest public school in the U.S.

“For no matter how they might want to ignore it, there was an air of excellence about this city (Boston), an air of reason, a feeling for beauty, a memory of something very good, and perhaps a reminiscence of the vast aspiration of man which could never entirely vanish.’’

— Arona McHugh (1924-1996), American novelist who set two of her novels in her native Boston

xxx

“The society of Boston was and is quite uncivilized but refined beyond the point of civilization.’’

— T.S. Eliot (1888-1965), Nobel Prize-winning Anglo-American poet, critic, essayist and playwright who came from an old Boston Brahmin family.

As the sea rises

“Crane Beach Gloucester MA’’ (archival pigment print), by Newton, Mass.-based photographer Vicki McKenna, at Fountain Street Fine Art Gallery, Boston.

The gallery says:

“Capturing photos of simplicity, subtlety, and serenity, Vicki McKenna’s work transmits a genuine sense of place. Her curiosity about natural landscapes stems from her background in geology, and her interest in architecture leads her to photograph the built environment. Working in both color and black and white she uses techniques that range from modern archival inks to traditional platinum/palladium prints

“In her current project McKenna creates images that are meant as harbingers from the future. They present the intertwining of ocean and shore environments as sea level rises. Her selection of locations to photograph is informed by, but not limited by, maps of projected sea level rise of 6 feet, a possibility by 2100. The mapping is visualized online by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. …

“After earning a PhD in Geological Sciences from Brown University and ALB in Natural Sciences from Harvard University, McKenna studied photography at the New England School of Photography and the Photography Atelier at the Griffin Museum. She has had juried solo shows at the Firehouse Center for the Arts, Newburyport and the Newton Free Library, and has exhibited extensively throughout New England and along the East Coast….’’

‘Fragment of an ancient land’

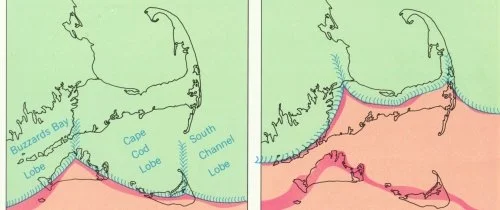

Moraines and heads of outwash plains on Martha's Vineyard, Nantucket and Cape Cod mark positions of the ice front during retreat. The also define lobes of the Laurentide ice sheet. The relationship between the deposits and lobes can be seen in this figure. Native Americans thousands of years ago lived on some of the land now underwater east and south of the Cape.

“East and ahead of the coast of North America, some thirty miles and more from the inner shores of Massachusetts, there stands in the open Atlantic the last fragment of an ancient and vanished land.’’

— From Henry Beston’s (1888-1968) The Outermost House (1928), about his time living in a beach shack on Cape Cod’s Nauset Beach.

‘Connectedness of all creation’

“Nest” (acrylic, netting, colored sand, papier-mache, wire) by Rhonda Smith, in her show “Say I am You,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, through January.

The gallery says:

“Inspired by the work of 12th-century Sufi mystic and poet Rumi, Rhonda Smith seeks to repair humanity and the broken environment. ‘Say I Am You’ draws from the connectedness of all creation to question the truth of society’s predominant model of colonialism, enslavement, and self-serving capitalism that ultimately destroys the natural world. Smith believes that repair lies in referring to mystics and poets like Rumi, who understood that separating ourselves from the universe is the un-making of all that exists.’’

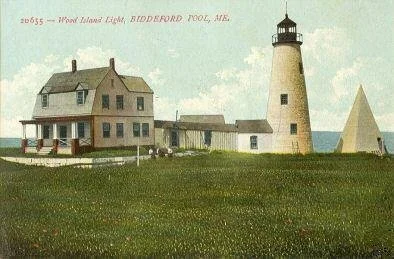

Ms. Smith is based in Boston and in the southern Maine Coast village of Biddeford Pool, which has long attracted artists and summer people.

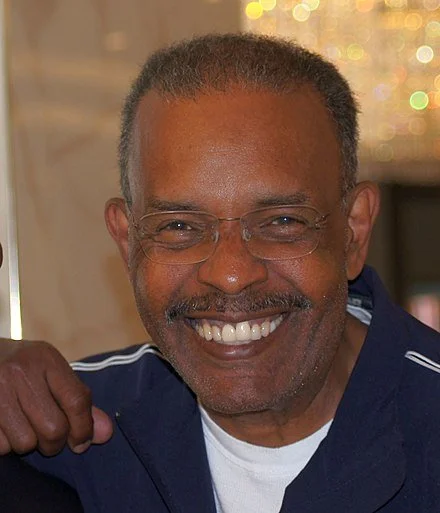

Llewellyn King: Joe Madison thinks that U.S. voting rights are worth risking his life

Joe Madison

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Election Day isn’t celebrated as a national holiday, and for most of us voting is inconvenient. So much so that only presidential elections draw a decent turnout. In 2020, a record year, 66.8 percent of the electorate voted.

The ballot box towers in significance in its consequence, but it seems banal when you traipse to a church hall, an armory, or a high school to do the deed.

Also, people in line to vote act strangely, suspecting each other of being a supporter of the rascals who have either made a mess of things or the rascals who will make a mess of things.

Given these things, and without regard to the present standoff in Congress over the For the People Act, it would seem to me that voting by mail, or even electronic voting, makes sense. We do most things of consequence electronically. The failsafe ID for voting in most states is a driver’s license. The Republicans are against voting by mail and electronic voting, but in most states, you can renew a driver’s license by either means. Kafkaesque?

For Joe Madison, the legendary Black broadcaster and human and civil- rights activist, voting is vital, and the ability to cast your vote easily and without duress is sacred. Further, He believes that contrived exclusion from the polls is a major felony against people of color.

Madison is prepared to put his life where his mouth is: He began a hunger strike for voting rights on Nov. 8, 2021.

During his college days, Madison was an all-conference running back on the football team, but now he is emaciated. He is following a liquid diet like one his friend Dick Gregory, the late comedian and civil rights activist, developed for his hunger strikes.

Madison told me he falls asleep at odd times and wakes up during the night. There is physical discomfort. Although he is getting to the point where the stress is showing, he plans to continue his hunger strike.

I have known Madison for over 20 years. I can hear the weakness in his voice. He is still doing his live radio talk show on SiriusXM Radio daily from 6 a.m. until 10 a.m. Eastern Time. As someone who has done four hours straight on radio, I can attest that in the best of health, it is a workout.

Madison sees the current battle over voting rights in the Senate and the Republican-controlled state legislatures’ push to restrict voting rights as reminiscent of the end of Reconstruction, when the South began to push back against Black voting rights granted at the end of the Civil War. “It included poll taxes, literacy qualifications, and property ownership, and led to lynching and the emergence of the Ku Klux Klan,” Madison said.

He told me he is worried for the future of his children and grandchildren if voting rights should be abridged again. He has three daughters, a son, five grandchildren and one great grandchild. He wants the vote to be free and fair for them and their children. That is why he is staring death in the face and hoping that the Democrats will prevail, and good sense will triumph, he told me.

Madison studied sociology at Washington University in St. Louis where, in addition to being a football player, he sang solo baritone in the college chorus. On graduating, Madison went into civil-rights work. At age 24, he became the youngest director of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in Detroit.

Madison began his broadcasting career in Detroit in 1980 and moved to Washington in the 1990s, where he mixed broadcasting with activism in a slew of causes.

I met Madison when he was protesting slavery in Africa and went to Sudan to free slaves. He wants the world to know how critical the voting-rights legislation is to the African-American community. “If we don’t get that bill, it could cost the Democrats both houses and the White House. African Americans may just be so fed up that they stay home and don’t vote,” he said.

Madison supports moves to modify the filibuster to bring about Senate passage. He is very hopeful the legislation will pass, and recalcitrant Democratic Senators Joe Manchin (W. Va.) and Krysten Sinema (Ariz.) will vote for changes to the filibuster. {Editor’s note: As of late last week, they opposed such changes.}

You don’t have to agree with Madison to admire him: a man with the courage of his convictions, measured by the endangerment of his health.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, DC.

Web site: whchronicle.com

Loco in loco

Storefront on Wooster Street in New Haven. New Haven is well known for its pizza but Yale students have been ordered not to eat in the city’s restaurants at least until Feb. 7 in an example of stringent medical theater.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

This note from a Connecticut boarding school is a display of that fragmenting thing, for a multiethnic semi-democracy, of excessive identity politics:

“As we continue the important dialogue

among Taft's BIPOC {Black and Indigenous People of Color} alumni and students,

we hope you will join us virtually

Thursday, January 13, 7pm EST

This event includes

Taft's Pan-Asian Affinity Group,

Mosaics (Black/LatinX Female Affinity Group),

Shades (Black/LatinX Male Affinity Group),

and Somos (LatX Affinity Group)’’

Education should be almost entirely focused on people as individuals, not as members of groups.

In other academic craziness, Yale has told students, whom they have placed under a quarantine until Feb. 7, that they:

“{M}ay not visit New Haven businesses or eat at local restaurants (even outdoors) except for curbside pickup.”

Does the university plan to send the campus cops around the city to arrest resisters at their tables?\

Then we have Princeton University’s order:

“Beginning January 8 through mid-February, all undergraduate students who have returned to campus will not be permitted to travel outside of Mercer County or Plainsboro Township for personal reasons, except in extraordinary circumstances. … We’ll revisit and, if possible, revise this travel restriction by February 15.”

Will there be roadblocks at the county line?

This is ridiculous medical theater and lunatic in loco parentis that will have little or no effect on the spread of COVID, which is pretty much everywhere now anyway.

But it’s certainly a good way to create right-wingers.

‘Business-like cold’

Photo by Stephen Hudson

“There has been more talk about the weather around here this year than common, but there has been more weather to talk about. For about a month now we have had solid cold—firm, business-like cold that stalked in and took charge of the countryside as a brisk housewife might take charge of someone else’s kitchen in an emergency.”

— E.B. White, in 1944, writing in his Harper’s Magazine “One Man’s Meat’’ column on life at his coastal Brooklin, Maine, farm.

Life at his “salt-water farm’’ inspired E.B. White to write this classic.

Victoria Knight: No, your cotton face mask isn’t all that effective

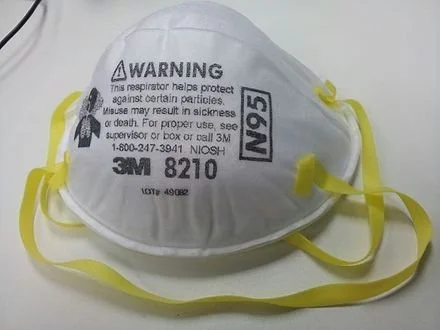

This N95 mask is highly effective.

— Photo by Banej

From Kaiser Health News in cooperation with PolitiFact

“From the perspective of knowing how covid is transmitted, and what we know about omicron, wearing a higher-quality mask is really critical to stopping the spread of omicron.’’

— Dr. Megan Ranney, academic dean for the School of Public Health at Brown University.

The highly transmissible omicron variant is sweeping the U.S., causing a huge spike in COVID-19 cases and overwhelming many hospital systems. Besides urging Americans to get vaccinated and boosted, public health officials are recommending that people upgrade from their cloth masks to higher-quality medical-grade masks.

But what does this even mean?

At a recent Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee hearing, top public health officials displayed different types of masking. Dr. Rochelle Walensky, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, wore what appeared to be a surgical mask layered under a cloth mask, while Dr. Anthony Fauci, chief medical adviser to the president, wore what looked like a KN95 respirator.

(Dr. Wakensky was formerly chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School.)

Some local governments and other organizations are offering their own policies. Los Angeles County, for instance, will require as of Jan. 17 that employers provide N95 or KN95 masks to employees. In late December, the Mayo Clinic began requiring all visitors and patients to wear surgical masks instead of cloth versions. The University of Arizona has banned cloth masks and asked everyone on campus to wear higher-quality masks.

Questions about the level of protection against COVID that masks provide — whether cloth, surgical or higher-end medical grade — have been a subject of debate and discussion since the earliest days of the pandemic. We looked into the question last summer. And as science changes and variants emerge with higher transmissibility, so do opinions.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has not updated its mask guidance since October, before the omicron variant emerged. That guidance doesn’t recommend the use of an N95 respirator but states only that masks should be at least two layers, well-fitting and contain a nose wire.

Multiple experts we consulted said that the current CDC guidance does not go far enough. They also agreed on another point: Wearing a cloth mask is better than not wearing a mask at all, but if you can upgrade — or layer cloth with surgical — now is the time.

Although cloth masks may appear to be more substantial than the paper surgical mask option, surgical masks as well as KN95 and N95 masks are infused with an electrostatic charge that helps filter out particles.

“From the perspective of knowing how COVID is transmitted, and what we know about omicron, wearing a higher-quality mask is really critical to stopping the spread of omicron,” said Dr. Megan Ranney, academic dean for the School of Public Health at Brown University.

A large-scale real-world study conducted in Bangladesh and published in December showed that surgical masks are more effective at preventing covid transmission than cloth masks.

So, one easy strategy to improve protection is to layer a surgical mask underneath cloth. Surgical masks can be bought relatively cheaply online and reused for about a week.

Ranney said she advises people who opt for layering to put the better-quality mask, such as the surgical mask, closest to your face, and put the lesser-quality mask on the outside.

If you’re really pressed for resources, Dr. Stephen Luby, a professor specializing in infectious diseases at Stanford University and one of the authors of the Bangladesh mask study, said surgical masks can be washed and reused, if finances are an issue. Nearly two years into the pandemic, such masks are cheap and plentiful in the U.S. and many retailers make them available free of charge to customers as they enter businesses.

“During the study, we told the participants they could wash the surgical masks with laundry detergent and water and reuse them,” Luby said. “You lose some effect of the electrostatic charge, but they still outperformed cloth masks.”

Still, experts maintain that wearing either a KN95 or an N95 respirator is the best protection against omicron, since these masks are highly effective at filtering out viral particles. The “95” in the names refers to the masks’ 95% filtration efficacy against certain-sized particles. N95 masks are regulated by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, while KN95s are regulated by the Chinese government and KF94s by the South Korean government.

Americans were initially urged not to buy either surgical or N95 masks early in the pandemic to ensure there would be a sufficient supply for health care workers. But now there are enough to go around.

So, if you have the resources to upgrade to an N95, a KN95 or a KF94 mask, you should absolutely do so, said Dr. Leana Wen, a professor of health policy and management at George Washington University. Although these models are more expensive and can be more uncomfortable, they are worth the investment for the safety they provide, she said.

“[Omicron is] a much more contagious virus, so there is a much lower margin of error in regards to the activities you were once able to do without getting infected,” Wen said. “We have to increase our protection in every way, because everything is riskier now.”

Wen also said that though these masks are characterized as one-use, unless you are in a health care setting, KN95s and N95s can be worn more than once. She uses one of her personal KN95s for more than a week at a time.

Another important thing to note is there are many counterfeit N95 and KN95 masks being sold online, so consumers must be careful when ordering them and be sure to get them only from a legitimate, trusted vendor.

The CDC maintains a list of NIOSH-approved N95 respirators. Wirecutter and The Strategist have both published guides to purchasing approved KN95 and KF94 masks. Ranney also recommends consulting the website Project N95 or engineer Aaron Collins’s “Mask Nerd” YouTube channel.

And remember, the risk of transmission depends not just on the mask you wear but also the masking practices of others in the room — so going into a meeting or restaurant where others are unmasked or wearing only cloth masks increases the odds of getting infected, no matter how careful you are. This chart demonstrates the huge differences.

Even with a mask upgrade, if you are still worried about omicron and, in particular, a serious case of , the No. 1 thing you can do to protect yourself is get vaccinated and boosted, said Dr. Neal Chaisson, an assistant professor of medicine at the Cleveland Clinic.

“There’s been a lot of talk about people who have been vaccinated getting omicron,” said Chaisson. “But I’ve been working in the ICU and probably 95% of the patients that we’re taking care of right now did not take the advice to get vaccinated.”

Victoria Knight is a Kaiser Health News reporter

vknight@kff.org, @victoriaregisk

George McCully: Can academics build safe partnership between humans and now-running-out-of-control artificial intelligence?

— Graphic by GDJ

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org), based in Boston

Review

The Age of AI and our Human Future, by Henry A. Kissinger, Eric Schmidt and Daniel Huttenlocher, with Schuyler Schouten, New York, Little, Brown and Co., 2021.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is engaged in overtaking and surpassing our long-traditional world of natural and human intelligence. In higher education, AI apps and their uses are multiplying—in financial and fiscal management, fundraising, faculty development, course and facilities scheduling, student recruitment campaigns, student success management and many other operations.

The AI market is estimated to have an average annual growth rate of 34% over the next few years—to reach $170 billion by 2025, more than doubling to $360 billion by 2028, reports Inside Higher Education.

Congress is only beginning to take notice, but we are told that 2022 will be a “year of regulation” for high tech in general. U.S. Sen. Kristen Gillibrand (D-N.Y.) is introducing a bill to establish a national defense “Cyber Academy” on the model of our other military academies, to make up for lost time by recruiting and training a globally competitive national high-tech defense and public service corps. Many private and public entities are issuing reports declaring “principles” that they say should be instituted as human-controlled guardrails on AI’s inexorable development.

But at this point, we see an extremely powerful and rapidly advancing new technology that is outrunning human control, with no clear resolution in sight. To inform the public of this crisis, and ring alarm bells on the urgent need for our concerted response, this book has been co-produced by three prominent leaders—historian and former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger; former CEO and Google Chairman Eric Schmidt; and MacArthur Foundation Chairman Daniel Huttenlocher, who is the inaugural dean of MIT’s new College of Computer Science, responsible for thoroughly transforming MIT with AI.

I approach the book as a historian, not a technologist. I have contended for several years that we are living in a rare “Age of Paradigm Shifts,” in which all fields are simultaneously being transformed, in this case, by the IT revolution of computers and the internet. Since 2019, I have suggested that there have been only three comparably transformative periods in the roughly 5,000 years of Western history; the first was the rise of Classical civilization in ancient Greece, the second was the emergence of medieval Christianity after the fall of Rome, and the third was the secularizing early-modern period from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment, driven by Gutenberg’s IT revolution of printing on paper with movable type, which laid the foundations of modern Western culture. The point of these comparisons is to illuminate the depth, spread and power of such epochs, to help us navigate them successfully.

The Age of AI proposes a more specific hypothesis, independently confirming that ours is indeed an age of paradigm shifts in every field, driven by the IT revolution, and further declaring that this next period will be driven and defined by the new technology of “artificial intelligence” or “machine learning”—rapidly superseding “modernity” and currently outrunning human control, with unforeseeable results.

The argument

For those not yet familiar with it, an elegant example of AI at work is described in the book’s first chapter, summarizing “Where We Are.” AlphaZero is an AI chess player. Computers (Deep Blue, Stockfish) had already defeated human grandmasters, programmed by inputting centuries of championship games, which the machines then rapidly scan for previously successful plays. AlphaZero was given only the rules of chess—which pieces move which ways, with the object of capturing the opposing king. It then taught itself in four hours how to play the game and has since defeated all computer and human players. Its style and strategies of play are, needless to say, unconventional; it makes moves no human has ever tried—for example, more sacrificing of valuable pieces—and turns those into successes that humans could neither foresee nor resist. Grandmasters are now studying AlphaZero’s games to learn from them. Garry Kasparov, former world champion, says that after a thousand years of human play, “chess has been shaken to its roots by AlphaZero.”

A humbler example that may be closer to home is Google’s mapped travel instructions. This past month I had to drive from one turnpike to another in rural New York; three routes were proposed, and the one I chose twisted and turned through un-numbered, un-signed, often very brief passages, on country roads that no humans on their own could possibly identify as useful. AI had spontaneously found them by reading road maps. The revolution is already embedded in our cellphones, and the book says “AI promises to transform all realms of human experience. … The result will be a new epoch,” which it cannot yet define.

Their argument is systematic. From “Where We Are,” the next two chapters—”How We Got Here” and “From Turing to Today”—take us from the Greeks to the geeks, with a tipping point when the material realm in which humans have always lived and reasoned was augmented by electronic digitization—the creation of the new and separate realm we now call “cyberspace.” There, where physical distance and time are eliminated as constraints, communication and operation are instantaneous, opening radically new possibilities.

One of those with profound strategic significance is the inherent proclivity of AI, freed from material bonds, to grow its operating arenas into “global network platforms”—such as Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple, Microsoft, et al. Because these transcend geographic, linguistic, temporal and related traditional boundaries, questions arise: Whose laws can regulate them? How might any regulations be imposed, maintained and enforced? We have no answers yet.

Perhaps the most acute illustration of the danger here is with the field of geopolitics—national and international security, “the minimum objective of … organized society.” A beautifully lucid chapter concisely summarizes the history of these fields, and how they were successfully managed to deal with the most recent development of unprecedented weapons of mass destruction through arms control treaties between antagonists. But in the new world of cyberspace, “the previously sharp lines drawn by geography and language will continue to dissolve.”

Furthermore, the creation of global network platforms requires massive computing power only achievable by the wealthiest and most advanced governments and corporations, but their proliferation and operation are possible for individuals with handheld devices using software stored in thumb drives. This makes it currently impossible to monitor, much less regulate, power relationships and strategies. Nation-states may become obsolete. National security is in chaos.

The book goes on to explore how AI will influence human nature and values. Westerners have traditionally believed that humans are uniquely endowed with superior intelligence, rationality and creative self-development in education and culture; AI challenges all that with its own alternative and in some ways demonstrably superior intelligence. Thus, “the role of human reason will change.”

That looks especially at us higher educators. AI is producing paradigm shifts not only in our various separate disciplines but in the practice of research and science itself, in which models are derived not from theories but from previous practical results. Scholars and scientists can be told the most likely outcomes of their research at the conception stage, before it has practically begun. “This portends a shift in human experience more significant than any that has occurred for nearly six centuries …,” that is, since Gutenberg and the Scientific Revolution.

Moreover, a crucial difference today is the rapidity of transition to an “age of AI.” Whereas it took three centuries to modernize Europe from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment, today’s radically transformative period began in the late 20th Century and has spread globally in just decades, owing to the vastly greater power of our IT revolution. Now whole subfields can be transformed in months—as in the cases of cryptocurrencies, blockchains, the cloud and NFTs (non-fungible tokens). With robotics and the “metaverse” of virtual reality now capable of affecting so many aspects of life beginning with childhood, the relation of humans to machines is being transformed.

The final chapter addresses AI and the future. “If humanity is to shape the future, it needs to agree on common principles that guide each choice.” There is a critical need for “explaining to non-technologists what AI is doing, as well as what it ‘knows’ and how.” That is why this book was written. The chapter closes with a proposal for a national commission to ensure our competitiveness in the future of the field, which is by no means guaranteed.

Evaluation

The Age of AI makes a persuasive case that AI is a transformative break from the past and sufficiently powerful to be carrying the world into a new “epoch” in history, comparable to that which produced modern Western secular culture. It advances the age-of-paradigm-shifts-analysis by specifying that the driver is not just the IT revolution in general, but its particular expression in machine learning, or artificial intelligence. I have called our current period the “Transformation” to contrast it with the comparable but retrospective “Renaissance” (rebirth of Classical civilization) and “Reformation” (reviving Christianity’s original purity and power). Now we are looking not to the past but to a dramatically new and indefinite future.

The book is also right to focus on our current lack of controls over this transformation as posing an urgent priority for concerted public attention. The authors are prudent to describe our current transformation by reference to its means, its driving technology, rather than to its ends or any results it will produce, since those are unforeseeable. My calling it a “Transformation” does the same, stopping short of specifying our next, post-modern, period of history.

That said, the book would have been strengthened by giving due credit to the numerous initiatives already attempting to define guiding principles as a necessary prerequisite to asserting human control. Though it says we “have yet to define its organizing principles, moral concepts, or aspirations and limitations,” it is nonetheless true that the extreme speed and global reach of today’s transformations have already awakened leading entrepreneurs, scholars and scientists to its dangers.

A 2020 Report from Harvard and MIT provides a comparison of 35 such projects. One of the most interesting is “The One-Hundred-Year Study on Artificial Intelligence (AI100),” an endowed international multidisciplinary and multisector project launched in 2014 to publish reports every five years on AI’s influences on people, their communities and societies; two lengthy and detailed reports have already been issued, in 2016 and 2021. Our own government’s Department of Defense in 2019 published a discussion of guidelines for national security, and the Office of Technology and Science Policy is gathering information to create an “AI Bill of Rights.”

But while various public and private entities pledge their adherence to these principles in their own operations, voluntary enforcement is a weakness, so the assertion of the book that AI is running out of control is probably justified.

Principles and values must qualify and inform the algorithms shaping what kind of world we want ourselves and our descendants to live in. There is no consensus yet on those, and it is not likely that there will be soon given the deep divisions in cultures of public and private AI development, so intense negotiation is urgently needed for implementation, which will be far more difficult than conception.

This is where the role of academics becomes clear. We need to beware that when all fields are in paradigm shifts simultaneously, adaptation and improvisation become top priorities. Formulating future directions must be fundamental and comprehensive, holistic with inclusive specialization, the opposite of the multiversity’s characteristically fragmented exclusive specialization to which we have been accustomed.

Traditional academic disciplines are now fast becoming obsolete as our major problems—climate control, bigotries, disparities of wealth, pandemics, political polarization—are not structured along academic disciplinary lines. Conditions must be created that will be conducive to integrated paradigms. Education (that is, self-development of who we shall be) and training (that is, knowledge and skills development for what we shall be) must be mutual and complementary, not separated as is now often the case. Only if the matrix of future AI is humanistic will we be secure.

In that same inclusive spirit, perhaps another book is needed to explore the relations between the positive and negative directions in all this. Our need to harness artificial intelligence for constructive purposes presents an unprecedented opportunity to make our own great leap forward. If each of our fields is inevitably going to be transformed, a priority for each of us is to climb aboard—to pitch in by helping to conceive what artificial intelligence might ideally accomplish. What might be its most likely results when our fields are “shaken to their roots” by machines that have with lightning speed taught themselves how to play our games, building not on our conventions but on innovations they have invented for themselves?

I’d very much like to know, for example, what will be learned in “synthetic biology” and from a new, comprehensive cosmology describing the world as a coherent whole, ordered by natural laws. We haven’t been able to make these discoveries yet on our own, but AI will certainly help. As these authors say, “Technology, strategy, and philosophy need to be brought into some alignment” requiring a partnership between humans and AI. That can only be achieved if academics rise above their usual restraints to play a crucial role.

George McCully is a historian, former professor and faculty dean at higher education institutions in the Northeast, professional philanthropist and founder and CEO of the Catalogue for Philanthropy.

The Infinite Corridor is the primary passageway through the campus, in Cambridge, of MIT, a world center of artificial intelligence research and development.

Don Pesci: The great dividing Connecticut River

VERNON, Conn.

Every so often a random piece in Quora, a site devoted to answering questions, will hit the eyeball like a hockey puck. Such is Patrick Reading’s short piece, “Why do New Englanders dislike Connecticut and feel it's not part of New England?”

Those of us who live east of the Connecticut River will appreciate his discussion and his tone, a blend of sturdy New England cynicism mixed with melted, buttery humor – very New England.

Reading’s working premise is that those with fortunes enough to live west of the river are imprinted with few characteristics normally associated with New England.

“East of the River,” he writes, “is classic New England. It's blue collar working class people, who root for the Patriots and the Red Sox, the Bruins and the Celtics. It's quiet old mill towns that saw better days a hundred years ago, and are still grinding along. It's rustic, with greasy old garages, motor heads with 3 cars in the front yard, corn and cow farms, and forests with stone walls running through them from farms long gone.

“West of the River is a suburb of New York City. It's money, old and new, manicured rural estates, stone walls meticulously maintained, full of Yankees ball caps and Giants bumper stickers. It's run down brick cities that lasted a little longer than the mills, but are packed with people that never moved on. It's traffic and congestion and poverty a stone's throw from elite private schools and country clubs.”

Having lived many years west of the river in southern Connecticut, I can confirm Reading’s reading of the state's East-West divide. In Redding, Danbury and Stamford, Connecticut’s West of the River capital, Hartford, often seemed to us as far off and fictional as Oz. Nearly all the television stations in Danbury and Bethel get their broadcasts from New York, not a part of New England, and denizens of southeast Connecticut infrequently thought seriously about state politics under the gold dome.

Then, too, the smell of old money was pungent. Greenwich, where my wife Andree taught in Catholic schools for many years, is what those unused to New England ways think that Connecticut represents.

“Western Connecticut is New York’s backyard,” Reading writes, “a Hollywood version of ‘New England’. They sell maple syrup to tourists, usually with Vermont’s label on it. They have someone trim their trees and sell it to the country inn that burns wood in a 300-year-old fireplace for ambiance. Other people ‘summer’ there, Their antiques stores are meticulous and curated for Manhattan interior designers, with someone in a suit making sure you don’t touch the merchandise without hearing an in depth story about its history. They have seafood dining experiences all year round, because where else are New Yorkers going to go for the ‘Christmas in Connecticut’ experience? They sell New York style pizza masquerading as ‘New Haven’ style. They talk like New Yorkers so it’s comfortable for outsiders.”

Overdone? A smidgen overdone, yes – but on the whole, Reading has Connecticut’s wealthy West of the river's number. It is impossible to imagine millionaire U.S. Sen. Dick Blumenthal or millionaire Gov. Ned Lamont living in Pomfret, although Lamont maintains an immodest summer cottage in North Haven, Maine, where his wealthy forbearers bought up much of the island. Blumenthal’s wife has deep roots in New York City, where her family owns the Empire State Building and other lush properties.

To demonstrate the bifurcation, Reading throws up a map showing the distribution of Red Sox and New York Yankee fans in the state, which conforms almost exactly to an East of the River, West of the River division, with Red Sox fans populating the eastern portion of the state.

Western and eastern Connecticut just feel different. Perhaps the best way of putting it might be to say that eastern Connecticut is Jeffersonian, full of virtuous farmers, while western Connecticut is Hamiltonian, full of Blumenthals and Lamonts, more politically inclined, with an unquenchable hankering for earning easy money and liberally spending other people’s money.

There is also a north-south divide and, as always, socialist Michael Harrington’s sundering division into poor and the very rich, who really seem to be, as F. Scott Fitzgerald many times told us, “different than you and me.”

How different are the very rich? Well, as politicians, they drag their log cabins with them wherever they go on the campaign trail, even in Connecticut’s larger cities, where the dependent and imprisoned poor wait for deliverance from political saviors who just now are promising them crumbs from rich tables in exchange for votes, the wealthiest of the politicians convinced that the quickest way to get a vote is to buy one with other people’s money.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

Brown study in a nightclub

“Jill at Ralph’s Diner” {restaurant and nightclub in Worcester}, photo by Milford, Mass.-based Anne D. McNevin at the current Attleboro Arts Museum’s members show.

First settled by English colonists in 1662 and incorporated in 1780, Milford became a booming industrial and mining community in the 19th Century, in large part because of a location that includes several rivers for waterpower and other uses, and large quantities of Milford pink granite.

Milford Pink Granite

The Flour and Grain Exchange Building, Boston (1892), built, as were many other large, impressive buildings in the Northeast, with Milford Pink Granite.

Poetic ‘predicaments’

Franconia Village with Sugar Hills background, circa 1908

“….I think

”I see the parts—haze, dusk, light

broken into grains, fatigue,

the mineral dark of the White Mountains,

the wavering shadows steadying themselves—

separate, then joined, then seamless:

the way, in fact, Frost's great poems,

like all great poems, conceal

what they merely know, to be

predicaments….”

— From “On the Porch at the Frost place, Franconia, NH,’’ by William Matthews (1942-1997)

Ben Franklin, ecologist

Breeding male Brewer's blackbird.

— Photo by JerryFriedman

“In New England, they once thought blackbirds useless, and mischievous to the corn. They made efforts to destroy them. The consequence was, the blackbirds were diminished; but a kind of worm, which devoured their grass, and which the blackbirds used to feed on, increased prodigiously; then, finding their loss in grass much greater than their saving in corn, they wished again for their blackbirds.”

— Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), a U.S. founding father and polymath. He was born and raised in Boston, which he left at 17 to move to Philadelphia.

David Warsh: On why 'not every couple should have a pre-nup'

“The Marriage Contract,’’ by Flemish artist Jan Josef Horemans the Younger, circa 1768

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The annual meetings of the American Economic Association convention unfolded over the weekend, on Zoom. In Boston, where AEA members had hoped to meet in person, it snowed. After I shoveled (and read the news from Kazakhstan), I went through the motions, watching half a dozen sessions over two days, all of them interesting, none of them possessing the elusive quality of newsworthiness, at least where my column Economic Principals is concerned, given the rest of the work at hand.

So I turned instead to two more deliverable items of interest: the Kenneth J. Arrow Lecture at Columbia University, which David Kreps, of Stanford University’s Graduate School of Business, delivered in Manhattan last month; and an intriguing new paper by William A. Barnett, of the University of Kansas, editor of Macroeconomic Dynamics and first president of the Society for Economic Measurement.

. xxx

Kreps, described by Columbia’s José Scheinkman as “one of the most accomplished theorists of our generation” (“and our generation wasn’t bad”), spoke under the title “Not Every Couple Should Have a Pre-Nup: How the Context of Exchange and Experience Affect Personal Preferences, and Why This Matters Both to Economic Theory and to Practical Human Resource Management.” The reference is to a long ago BusinessWeek column by the late Gary Becker, of the University of Chicago.

If a contract were required before a couple could legally marry, Becker argued, no bad vibes or stigma would attach to divorce. Not so fast, Kreps countered. There was abundant reason to suspect that preferences are not fixed; that such contracts might interfere with their evolution over the course of a marriage. He proceeded to carefully sort through the implications, in the manner he learned as a close reader of Arrow.

Since the World War II, mainstream economics had become “mathematical,” Kreps said. Everyone understood what he meant: formal models had become the standard means of professional discourse. Developments then came in two broad waves. The first wave, between 1945 and 1970, developed choice theory, price theory and general-equilibrium theory, he said.

The second wave, beginning in 1970 and not over yet, consisted of information economics: “getting serious about the formation of beliefs, especially beliefs about the actions of other economic agents (and how they will react to your own actions).”

“It is well past time for the third wave,” he continued, “Getting serious about preference-determination and preference-evolution.” He connected the movement to concerns that Arrow had expressed as long as fifty years ago. He cited a couple of present-day books as serious curtain-raising work – Identity Economics: How Our Identities Shape Our Work, Wages, and Well-Being, by George Akerlof and Rachel Kranton; and The Moral Economy: Why Good Incentives Are No Substitute for Good Citizens, by Samuel Bowles. And he elaborated his own views, “as a commentator, not an originator” – of the extensive careful modeling and testing that would be necessary to establish preference formation as a contribution to serious economics.

On “shaky grounds,” Kreps concluded, “I contend that taking more seriously how preferences are affected by context and experience within context, will— on net — be good for our discipline.” Joseph Stiglitz, of Columbia University, contributed a lively discussion.

All the more reason then, to tune in, when you can, to the Distinguished Lecture that Nathan Nunn, of Harvard University, delivered to the AEA meetings on Friday. A recording of “On the Dynamics of Human Behavior: The Past, Present, and Future of Culture, Conflict, and Cooperation” presumably will be available for free viewing on the AEA Web site in a day or two. If you like this sort of thing, it is definitely worth the wait.

. xxx

Barnett is less well-known in the profession than is Kreps, but he is an unusually interesting gadfly, a talented outsider with a knack for connecting with talented insiders over the course of a long career. Trained as a rocket scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he spent most of the 1960s at Rocketdyne in suburban Los Angeles before leaving in 1969 for Carnegie Mellon University, and a PhD in statistics.

After seven years in the Special Studies Section of the Federal Reserve Board, a unit since abolished, Barnett left with the conviction that instead of depending on classical accounting procedures, the central bank should be using modern methods devised in the 1920s by the French economist François Divisia. a founder of the Econometric Society, and not well-understood by Anglophone economists until 1973. Erwin Diewert, of the University of British Columbia, suggested employing a class of index numbers. known as “superlative” indices, as a suitable alternative to the Fed’s accounting aggregates. Barnett continued to advocate an approach known as the Törnqvist-Theil Divisia index. (Elaboration added)

In 2012, MIT Press published Barnett’s Getting It Wrong: How Faulty Monetary Statistics Undermine the Fed, the Financial System, and the Economy. He has been lobbying for the change (the “Barnett Critique”) ever since, first at the University of Texas, then Washington University, and, since 2002, at the University of Kansas. He was a founder of the Center for Financial Stability, a Manhattan-based think tank, and is director of one of its programs, as well.

Last week a paper by Barnett and four others circulated widely on the Internet. “Shilnikov chaos, low interest rates, and New Keynesian macroeconomics,” from the latest Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, was sufficiently interesting that Barnett arranged to have it published open access online. “[I]t might be very important,” he wrote.

I wrote back to say that Shilnikov chaos attractors were well above my paygrade. Barnett replied in plain English:

We have another paper about how to fix the problem. It isn’t difficult to fix. The source of the problem is that attaching a myopic interest rate feedback equation (Taylor rule) to the economy’s dynamics without a long run terminal condition alters the dynamics of the system to produce downward drift in interest rates. Our results produce an amazing match to the 30-year downward drift of interest rates into the current liquidity trap. The solution is for the Fed also to have a second policy instrument to impose a long run anchor (no surprise to the ECB). Since the short run interest rate is useless as a policy instrument at the zero lower bound, central banks are now experimenting with other instruments. It would have been better if they had done that before interest rates had drifted down into the lower bound.

That wasn’t hard to understand at all, at least intuitively. Ever since William Harvey in 1628 demonstrated the heart’s circulation of the blood, economists, from John Law and François Quesnay to the designers of today’s flow of funds accounts, have sought to understand the mysteries of the economy’s circular flow of money, products and services. Though never a boatswain, I have had enough experience anchoring boats in sometimes powerful currents to recognize the virtues of having more than one anchor out, sometimes in a completely different direction.

The last fifty years have been a wild ride for the Fed’s managers of the world’s money. Don’t expect to enter a quiet harbor any time soon.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

William T. Hall: An island’s crucial boat and the widow’s fish

On the beach with a Block Island Double Ender

— Watercolor by William T. Hall

Block Island is a small landmass shaped like a pork chop 16 miles off southern Rhode Island. It’s where my father was born, in 1925. His entire family were fisherfolk. He got his start fishing at age 10.

Historically, the old salts depicted in the marine art and stories of the past were men, but the wives, mothers and daughters of island fishermen were essential to the life of any Block Island family that made its livelihood from the sea.

Of course, as usual, women saw to all the usual unsung details of daily life in the home and spiritual life in the community, but little remembered today is the extent of the decisions made, and physical labor provided by island women, and how important that was to their family’s survival and success.

Long before my father was born, the indigenous tribes and white settlers on the island took to the sea for their livelihood. They first had to overcome the major geological disadvantages of the island. The high bluffs and open ocean exposure on the southeast corner of the island were perilous, and to the north at North Light were the shallows off Sandy Point that still claim lives of surf fishermen today. These were daunting and dangerous obstacles. For many years the shores of Block Island challenged captains with hazardous approaches and no reliable anchorages.

Progress through adversity

Consider the challenge of designing boats to use at Block Island. For many years, the “perfect Block Island boat’’ was dreamed about, prayed about and then modeled out of wood. It occurred to the early settlers that the way to create a seaworthy vessel on a beach had already been invented by the Celts and Vikings . With a foggy notion of history and woodworking skills barely sufficient to fabricate a house, the new islanders patched together their own unique surf-wise boat. The design was not beautiful, but it was practical because it was based on two important borrowed principles from sea-faring people many hundreds of years before.

It should be sturdy, with two sharp ends for launching from beaches and surviving a following sea when landing. It should have a sail arrangement

best described as “simple and flexible.” It allowed for two small sails, which when reefed down, looked like oversized canvas handkerchiefs. These design considerations proved essential to moving the boats around rocks, then from high cresting waves down onto safe sandy beaches.

The most important aspect of this design was that the boats could be launched into the surf and retrieved from the brine by a small group of men and, yes, women, often with the help of oxen, horses, mules and mechanical hauling contraptions called “capstans”.

This homely workboat was a dory called “The Block Island Double Ender”. It could be launched from the beach into the morning surf and then brought back at night through a different tide, to be stored high up in the dunes safe from northerly storms. This kind of boat varied from 22 to over 36 feet long and was weighted by fieldstones for ballast that would be thrown overboard to balance the weight of a daily catch. The boat was destined to become the mainstay workboat for the island from before the American Revolution but eventually, of course, was made obsolete by steam and gasoline engines.

The stories of the colorful fishermen who manned these seaworthy boats earned them a certain notoriety with many world-class sailors. The boats form a deep mythology as colorful as the exploits of the gods on Mt. Olympus. They had names such as Dauntless, Island Bell and Bessie, I, II and III. There were perhaps as many as 50 boats built and launched from coves around the island. One such beach is even named “Dories Cove”.

For over 200 years, they faced Neptune’s furry and a vengeful Old Testament God, as they fished a bountiful sea around Block Island. Then, over just a few decades, the boats melted away. The end of these boats was ignoble. Finally abandoned by the careless hands of progress, their exposed ribs and rigging melted into the island’s underbrush and rose-hip bushes. It was said by a Civil War veteran, “Only those who had witnessed soldiers left unburied after a battle can feel the shame at the sight of this wasteful demise”.

The holiest of testaments paid to Block Island Double Enders was repeated by the captains who had fished in them, “With all that time and everything they went through, only one boat was ever lost to the sea”. Is it true? As an owner of an original reproduction of this wonderful boat I can only say, “It is possible”.

All along, women have played a part in the history of the island, its boats and its success as an island community. In the early history, when a man’s hand heaved at the side rails, or the harnesses of the

oxen, female voices as well as men’s voices were heard shouting as they all pulled in unison with the men. Every able-bodied fisherman, woman, boy and elder was needed to launch and retrieve the boats of the fleet each day.

Women also helped with maintenance, sail repair, outfitting, marshaling supplies, cleaning the catches, gathering and managing bait, all while feeding their families and sharing child-care.

Some women were on the beaches for much of the day waiting for the boats to return. And some women might ride the family mule back to work in their gardens, feed livestock and hang laundry while they kept an eye on the horizon for their family boat to come into sight. Some made stews and chowders and roasted potatoes in the coals of beach fires while they waited. Some cared for the oxen and set wire minnow traps in the salt estuaries. Some dug quahogs for bait from the wet sand on the lower parts of the beaches for the next day’s bottom fishing. \

When the boats were out the women were assisted by old men and school-age boys and girls, before and after school. Young girls helped the working mothers by babysitting the youngest children, tending stew pots, mending nets and making clothing. The women’s contribution would be universally appreciated on Block Island and earn them an equal place in the fabric and soul of the island.

At the time when my father was young many things had changed. Commercial fishing had become totally the purview of men, often symbolized artistically by heroic images of stalwart captains on mammoth commercial fishing boats. By this time, most daughters of fishing families were educated and provided such services on the island as teaching, nursing, real estate, bookkeeping, town business, cab driving and tourism, to mention only a few.

Regardless of these changes, appreciation of women’s role on the island continued. Quiet acknowledgement by giving shares to those who contribute became a tradition in my father’s generation called simply “The Widow’s Fish”.

Although difficult to translate directly, it means always making sure that all the elder and/or widowed women still living on the island would receive fish from every day’s catch. It was standard for every fisherman and farmer on the island to share part with those in need with little fanfare. Sermons in the island’s churches, grace said at daily meals, dedications at public benedictions and remembrances of departed fishing folks were often framed around the notion of “sharing and appreciation,’’ including the crucial role that women played.

I remember this quiet homage paid by my father during our summer vacations, from Vermont, on the island. Although he had migrated off the island to work as a salesman and gentleman farmer, we vacationed on the island, visiting relatives and friends and fishing daily on boats owned by relatives.

One day we had caught more flounder than we could eat, and my father made sure to separate out the catch into portions or “shares”. In that bounty was a special offering, something he called, “The Widow’s Fish”. He always put that portion aside during the filleting. All the harbor’s fishermen had one or two additional people outside their immediate families who were living alone and as Father would say “are living a little closer to the bone than we are”.

In those days, he’d leave the boat and go up the dock to the phone booth by Ernie’s Restaurant. There he’d call a prospective list of names to ask if they could use some flounder, bluefish, fluke, black bass and occasionally

Swordfish. (The last were getting scarce in those days.) I remember the names on his list -- Ida, Annie Pickles, Aunt Annie Anderson, Blanche Hall and Bea Conley. These were elderly ladies whose homes we often visited on the way home with pails of filleted fish.

As I later found out, my father, when he was a teenager, had often crewed as a deck hand or swordfish striker for the husbands of the ladies we visited. All or most of the men were captains who operated fishing boats that Dad had worked on before he went into the Army, in 1944. It wasn’t until later in life I found out there was an added depth to my father’s gratitude.

In those old days these women had found a way to stretch many of their own family meals so that my father, orphaned at age seven, could stay for dinner.

These grateful ladies of the island formed a matriarchal umbrella of love and service to each other and their community. They always remembered my grandmother Suzie Milliken, whom some fondly called “Sister Suzie,” through a custom they referred to as “calling her to the room’’. The expression was used from Victorian times to mean connecting with a departed soul in a séance. As they thanked and hugged my father, they tearfully called him by the boyhood nickname Suzie had given him.

“Billy,’’ they assured him, “Suzie, would be proud of you for remembering to bring us our fair share”.

William T. Hall is a painter, writer and former advertising agency creative director based in Florida and Rhode Island.

Fishermen at the long-gone fish market co-op building at Old Harbor, Block Island, in the ‘40s.

— Photo courtesy of George Mott

Chris Powell: $75 million could be spent better; stop hysteria over COVID home testing

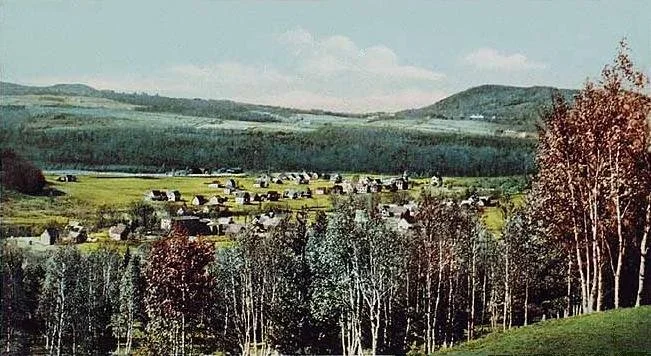

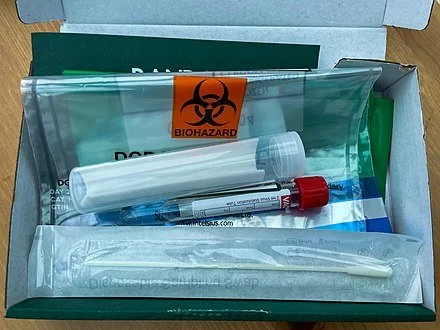

COVID-19 home test kit.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont could have found worse things to do with the $75 million in federal emergency aid he ordered distributed last week as a bonus to poor households receiving the state's earned-income tax credit. On average those households probably have suffered more financially from the long virus epidemic, since many of their breadwinners hold, or held, the service-sector jobs that were the first to be cut back or eliminated.

Complaints from Republicans that the bonuses mainly will reward a constituency of the governor's party, the Democrats, as his re-election campaign begins are not so compelling. For nearly everything government does rewards some political constituency, and state law already had identified the earned income tax credit constituency as deserving. If Connecticut ever again has a Republican administration, it will be unusual if Republican-leaning constituencies -- if only ordinary taxpayers -- are not rewarded too.

The governor's dispensing that $75 million is troublesome for different reasons, starting with the disregard for democratic procedure.

The governor's office says the federal law that sent the emergency money to the state authorizes his administration to spend it on expenses incurred because of the virus epidemic. But the state has been paying its earned income-tax-credit obligations all along. No payments by the government were cut because of the epidemic. While many recipients surely suffered losses because of the epidemic, it's unlikely that all did, and no one receiving the bonus will have to show evidence of such losses. The expenses to be reimbursed here are merely being assumed.

Additionally, $75 million is a lot of money for state government to dispense out of the blue at the command of just one official, an amount never formally appropriated by the General Assembly. Indeed, as Republican legislators note, state law already had determined how much was to be spent on the tax credit. The bonus created by the governor overrides that legislation.

Since he still exercises -- at least until February -- emergency powers to rule Connecticut by decree, the governor presumably could have rewritten the tax-credit law by himself to authorize the bonus. But he did not do so, perhaps because it might have emphasized his gathering unnecessary power to himself.

Republican legislators note that Connecticut faces many other compelling needs apart from those of the tax-credit recipients and that ordinary democracy first would have summoned the legislature or legislative leaders to discuss how to spend the $75 million. That's why the governor's high-handedness here is another argument for letting his emergency powers expire.

Having continued for two years, the virus epidemic is no longer an emergency. While the epidemic will wax and wane as epidemics do, government is fully aware of what combating it may require. Most of all, combating it may require more medical facilities and staff, and thus, to finance them, fewer raises for government employees, fewer stupid imperial wars and that $75 million that instead will be spent to expand the tax credit.

That money might build a few hospital wards and hire more doctors, nurses, and auxiliary staff. It might buy and distribute antivirals and vitamins.

If the tax-credit bonus can be construed as an expense of the epidemic, surely expanding medical capacity and services could be construed similarly. With so much free money flowing from Washington, the federal government probably wouldn't object if Connecticut chose to get more relevant.

After all, unlike the tax-credit bonus, increasing medical capacity might benefit everyone who got sick.

Meanwhile government's frantic efforts to distribute home testing kits for the virus and the public's frantic efforts to obtain them seem misplaced.

Surely quite without a test most people can tell if they are sick with symptoms like those attributed to the virus, and surely most people with such symptoms might have enough sense to get to a doctor or hospital quickly, especially since early treatment of the virus is crucial to defeating it.

The people lately waiting in long lines for a home test kit for the virus well may be putting themselves at greater risk of contracting it. The virus is bad enough. Test hysteria induced by government will make it worse.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

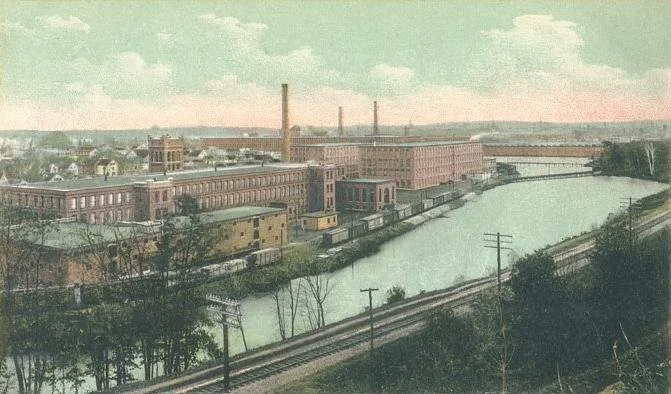

Video: 'Satanic mills' in two 'green and pleasant' lands

Arlington Mills, Lawrence, Mass., in 1907

A view of the Berkshires from near North Adams, Mass.

— Photo by jbcurio

Below is a local version of the weird, haunting English poem by William Blake called “Jerusalem,’’ written about 1804. It has long been best known as the hymn of the same name, with music written by Sir Hubert Parry, in 1916. (Remember the movie Chariots of Fire?)

Timmy May, of Newport, R.I., came up with the idea of inserting "New" before “England’’ in the three places where “England” appears in the original Blake poem.

The Industrial Revolution brought many, many “dark satanic mills,’’ first to England and then to its offspring.

Mr. May is on the left in the video below. The other musicians are Jamie Lawton, on violin, and Gregory Jonic, on uilleann pipes.

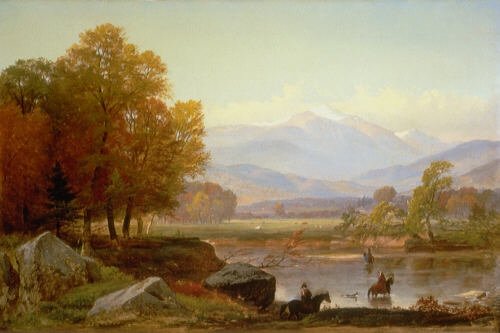

‘The refined grandeur’

“Mount Washington,’’ by Samuel Lancaster Gerry (1813-1891)

“A visit to New Hampshire supplies the most resources to a traveler, and confers the most benefit on the mind and taste, when it lifts him above mere appetite for wildness, ruggedness, and the feeling of mass and precipitous elevation, into a perception and love of the refined grandeur, the chaste sublimity, the airy majesty overlaid with tender and polished bloom, in which the landscape splendor of a noble mountain lies.”

— Thomas Starr King (1824-1864), an American Universalist/Unitarian minister.

He was influential in California politics during the Civil War, and pressed to keep California rather than splitting off as a separate country.

He vacationed in New Hampshire’s White Mountains in the 1850’s while a minister in Boston and in 1859 published a book entitled The White Hills {Mountains}; their Legends, Landscapes, & Poetry.

Why New England has a certain coherence and consistency

The flag of the New England Governors Conference. The pine symbol has been associated with the region from early Colonial days. The wood was used for housing, boats and furniture. The nickname of the region’s most wooded state, Maine, is The Pine Tree State.

But the origin of the several similar New England flags also goes back to the Red Ensign of the Royal Navy, first used in 1625, with merchant vessels being granted its use by 1663. Shipping became a major part of the region’s economy early on.

“New England, unlike the rest of the United States and other parts of the world that were colonized by European powers, is a realized idea. The people who, from a European perspective, were its founders had envisioned that New England would continue a tradition in Christian history, and also political history, by becoming a plantation for Christianity in the “new world,” which would function as an autonomous republic.

New England was created by colonists who fanned out from that initial Massachusetts Bay colony. The colonists who were granted the charter for Massachusetts Bay were given small tracts of land. They created new colonies that were pulled together through the forces of economics and culture. So, the vision that shaped the beginnings of Massachusetts was stamped on the region as a whole. New England developed a consistency and coherence that much of the rest of the United States lacks.’’

—- Mark Peterson, a professor of history at Yale University, in an interview with Five Books

English explorer and soldier John Smith coined the name “New England’’ in 1616.

Dangerous footwear

“Winter” (1876) by Julius Sergius von Klever

“….the street

is too icy old women in pointy shoes

and high heels pass him their necks

in fur collars bent their eyes watch

their small slippery feet’’

— From “Winter Afternoon,’’ by Grace Paley (1922-2007). The poet and short-story writer lived in Thetford, Vt., from the early ‘90s to her death.

Main Street in Thetford in 1912.