Talking therapy in Brockton

“Conversation” (clay, graphite,), by Melissa Stern, in her show “Melissa Stern: The Talking Cure,’’ at the Fuller Art Museum, Brockton, Mass., Jan. 29-May 15.

The museum says that these witty (and sometimes unsettling) sculptures "are a spirited cast of characters formed in clay." The show takes its name from Sigmund Freud’s description of psychoanalysis, and centers on Ms. Stern’s 12 ceramic sculptures. The artist invited 12 writers to create inner monologues for each of the characters and 12 actors to perform them for audio recordings.

Brockton City Hall, which opened in 1892 during Brockton’s heyday as a center of manufacturing, especially of shoes.

Todd McLeish: Seeking strategies for sustaining bay scallops

Bay scallop staring at you with its blue eyes

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

In the Great Salt Pond on Block Island, native bay scallops are thriving like nowhere else in Rhode Island. Scientists from The Nature Conservancy survey the 673-acre tidal harbor every autumn and have recorded hundreds of scallops each year, despite as many as 50 recreational shellfishermen harvesting scallops from the pond each November and December.

The same cannot be said of the rest of the Ocean State’s waters, however, where bay scallops are few and far between.

On Block Island, Diandra Verbeyst leads a three-person team of Nature Conservancy scuba divers and snorkelers who monitor 12 sites around the Great Salt Pond. They have counted an average of 225 scallops annually since 2016, up from just 44 observed by previous observers in 2007, the first year of monitoring.

“There are slight rises and falls from year to year, but the population is pretty stable,” Verbeyst said. “Based on the 12 sites we monitor, the population is indicating that there is spawning happening each year, and there is recruitment to the population.”

In addition to scallop data, Verbeyst and her team also collect information on water quality and other environmental conditions during their surveys.

“The scallops are an indication that the ecosystem is healthy and doing well, and for me, that’s fascinating in itself,” she said. “No matter where you are in the pond, there’s a good chance you’ll see a scallop.”

Bay scallops are bivalve mollusks with 30-40 bright blue eyes that live in shallow bays and estuaries up and down the East Coast, preferring habitats where eelgrass is abundant. They are short-lived animals — most don’t live more than two years — and are significantly smaller than sea scallops, which are found farther offshore and are harvested by the millions by New Bedford-based fishermen.

Chris Littlefield, a Nature Conservancy coastal projects director and former part-time shellfisherman on Block Island, recalled collecting scallops as a child in the Great Salt Pond 50 years ago, and he has been gathering them in small numbers for his family’s consumption ever since. He said the scallop population received a boost in 2010, when immature scallops grown at the Milford {Conn.} Laboratory of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration were dispersed into the pond in a project funded by the Natural Resources Conservation Service.

“That project broke through some kind of threshold,” Littlefield said. “Scallops weren’t as abundant before that, and they used to be confined to certain key locations and that was it. But now they’re more abundant and more people are finding them and harvesting them.”

Unlike Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard and a few locations on Cape Cod and Long Island, where regular seeding of immature bay scallops has resulted in thriving commercial fisheries, Rhode Island has a tiny commercial fishery for bay scallops — fewer than three fishermen participate — and the fishery is not sustainable.

Anna Gerber-Williams, principal marine biologist for the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s Division of Marine Fisheries, just completed the first year of a three-year effort to assess the state’s bay scallop population. She is focused primarily on the salt ponds in South County, especially Point Judith Pond and Ninigret Pond, which historically had healthy bay scallop populations.

“We manage and regulate the bay scallop harvest, but besides Block Island, we haven’t had an actual assessment of what the population looks like in Rhode Island,” Gerber-Williams said. “We know it’s pretty low, and we know the actual commercial harvest numbers are very low. But we don’t have anything to base our management on. The hope is that this project can turn into more long-term monitoring, similar to what’s done on Block Island, and maybe lead to restoration efforts.”

Based on her first year of surveys, Gerber-Williams said there are self-sustaining populations of bay scallops in Point Judith Pond, and their abundance can fluctuate significantly from year to year.

“Scallops are very habitat-dependent,” she said. “The habitat in the salt ponds is very patchy, and those patches are very small.”

Unlike clams, which bury themselves in the sand, bay scallops sit on the seafloor and can swim around by rapidly opening and closing their shell, making them difficult to track and count. Gerber-Williams said they are threatened by several varieties of crabs, which can easily crush the scallops’ shells with their claws.

“Part of the scallop’s strategy is to hide from the crabs in the eelgrass,” she said. “When they’re younger, they attach themselves to eelgrass blades to keep themselves above the bottom and out of reach of predators.”

Dan Torre at Aquidneck Island Oyster Co. experimented this year with growing bay scallops in cages in the Sakonnet River off Portsmouth. He bought scallop seed from area hatcheries last July, and they are approaching marketable size now. He has contracted with one local restaurant to buy his experimental crop, with hopes of scaling up the operation next year.

“I believe there’s a market, but it’s a niche market,” he said. “Normally with sea scallops, you sell just the shelled adductor muscle, but with bay scallops you sell the whole animal. The shelf life isn’t the longest, but it seems like there are a bunch of restaurants that are eager to try them.”

In an effort to figure out how best to restore wild bay scallop populations in the region, the Rhode Island Commercial Fisheries Research Foundation is collaborating with The Nature Conservancy to synthesize what is known about the history of the bay scallop population and fishery in Point Judith Pond.

According to Dave Bethoney, the foundation’s executive director, it will be combined with information about scallop fisheries in Massachusetts and Long Island, N.Y., as a first step to developing a restoration plan.

“How to make them sustainable is the real puzzle,” Bethoney said. “Even successful efforts on Long Island are based on a seeding plan — getting scallops every year from aquaculture facilities to replenish them. They have successful populations, but they’re not self-sustaining. I don’t know how we change that.”

Gerber-Williams agreed.

“In my opinion, the way to boost populations here and keep them at a level that’s sustainable for a good fishery in Rhode Island, we would have to have a seeding program similar to what they have in Long Island and Martha’s Vineyard,” she said. “Every year they put out thousands of baby bay scallops. They seed their salt ponds every single year to keep a decent fishery going.

“So the next step for us would be to do that kind of seeding program in Rhode Island. We’re in the process of creating a restoration plan for various species of shellfish in Rhode Island, and my hope is that bay scallops are a part of that.”

Hopefully the current researchers go back to the North Cape shellfish injury restoration project, which included release of bay scallop seed into the South County salt ponds, to learn about what worked or did not work for the multi-year that wrapped up by 2010. The reports are available and some of us who worked on the project are available to discuss challenges and successes.

Todd McLeish is an ecoRI News contributor.

Eelgrass is prime habitat for bay scallops.

Soon you can do it outside

“Ice Skating Blues” (drawing and encaustic on board), by Providence-based painter Nancy Spears Whitcomb

Wary celebrations

Work by 2019 Best of Show Winner Connor Gewirtz at the Providence Art Club.

Old salts

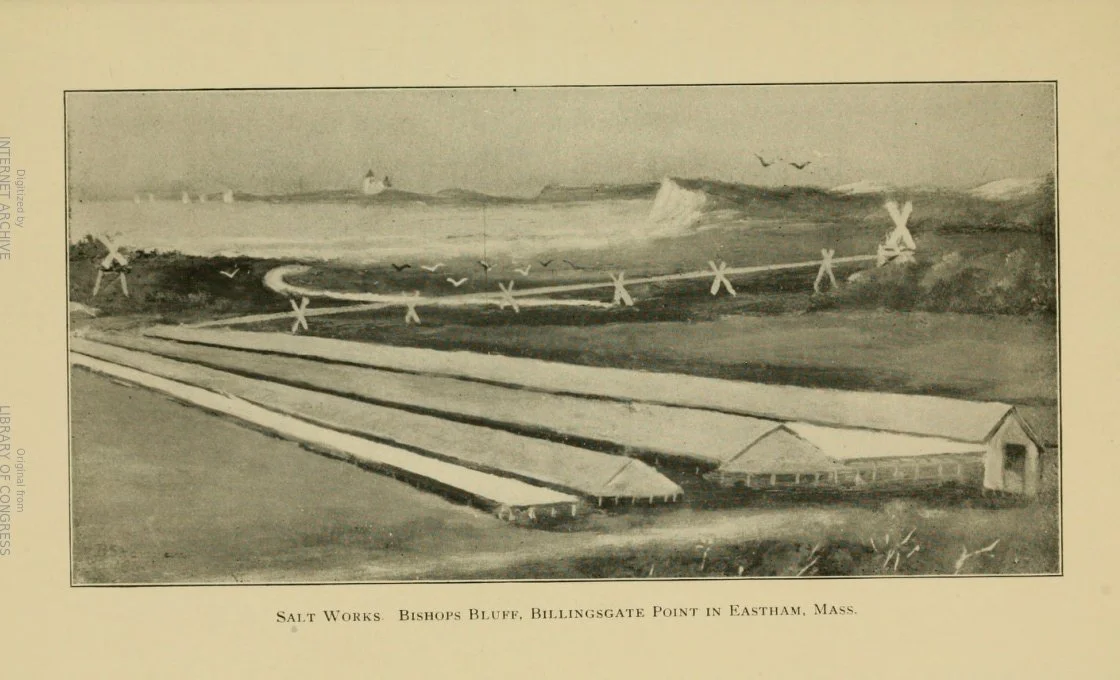

West Yarmouth salt works in the 19th Century.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Some of my ancestors were in the salt business on Cape Cod in the 19th Century; they made it from evaporating ocean water. It seems so long ago that large amounts of such a basic commodity, like ice cut from ponds in Maine, would be produced in low-tech ways in New England, for the local and faraway markets. (Blocks of ice from New England would be packed in sawdust and shipped by boat to the Southeast.)

The smarter relatives moved money that they made from this commerce into more lucrative manufacturing of shoes, tools and so on. A few even straggled into mid-20th Century high tech. Of course, all sectors fade in the end.

Llewellyn King: Taking the stand for the truth, not a political party; beware false equivalence

An angel carrying the banner of "Truth", in Midlothian, Scotland.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I remember the feeling in newsrooms back in the 1960s, as many journalists began to have doubts about the Vietnam War.

In those big workspaces where newspapers come together and broadcasts are assembled, the Vietnam War was taken by journalists to be the good guys versus the bad guys -- the way it had been in the two world wars and the Korean War. But by the mid-1960s, the media were turning against the war.

Some reporters went to Vietnam, the rest of us edited and sometimes melded several files from the war.

Initially, coverage reflected simply what the U.S. commanders were saying in daily briefings from Saigon. As our colleagues on the ground in the war zone began to tell a different story from the official one, editors and writers far from Vietnam began to change their views. Enthusiasm turned to doubt, followed by an anti-war sentiment. The media, in its way, had found its conscience.

Media doubt accelerated as the war dragged on and turned to something close to hostility. I was privy to this because I circulated as a desk editor between three newspapers: the Washington Daily News, the Washington Evening Star, and the Baltimore News-American, finally roosting at The Washington Post.

The American Newspaper Guild passed an anti-war resolution at its annual convention in Dallas in 1969. This side-taking disturbed many journalists. It wasn’t objective, but it passed anyway.

Today, the media landscape is different. There are many more partisan outlets in broadcasting and fewer strong, local newspapers. And there is the whole new world of social media, which defies monitoring. Still the reporting is done by the mainstream media, and from this all-else flows.

While the attitudes of the mainstream are important, they aren’t as commanding as they were in the time of the Vietnam War -- in the time when the nation watched the evening news with total belief and hung on every word from Walter Cronkite.

I have a strong sense of that same struggle between the professional requirement for objectivity and the private conscience is testing the media today just as it did in the days of the Vietnam War.

Can we still cover the divisions of today as an event, as we do most things, or is it morally different?

There is an emerging consensus that journalists collectively -- and a more disaggregated group couldn’t be imagined than the irregular army of nonconforming individualists which make up the Fourth Estate -- are concerned about the survival of democracy. The very basis of our freedoms, of our pride, and even of our history as a free nation capable of the orderly and willing transfer of power is at stake. You can’t work in media now and not feel the sense of the nation going off the rails.

It is, I submit, a turning point when journalists of conscience can’t fall back on the old rules of objectivity, giving one opinion and countering it with another. To give the other side, when you, the writer, know the other side is a contrived lie, is to give credence to the lie and further extend its malicious purpose.

You can’t give the lie the same credence as the truth or you will hide in false equivalence and fail the public.

Even journalists I know who are socially and politically conservative are signing on to the idea that they must take a stand for the truth.

The Big Truth being that Joe Biden won the presidential election, verified over and over again by recounts and court findings. The false equivalence would be to repeat the Big Lie and say at the end of a report, “But supporters of Donald Trump assert the election was rigged.”

When you know that the future of our democracy is in the balance, as a journalist, you feel it is time to take a stand; not to stand with Democrats, but to stand with the truth.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email address is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Linda Gasparello

Co-host and Producer

"White House Chronicle" on PBS

‘Truth as multiple’

Detail of The Khan Hotel wallpaper in Brussels,’’ by Lebanon-based architect, author and artist Raafat Majzoub, in his show “GROUNDS,’’ Jan. 15-Feb. 20 at the Boston Center for the Arts.

The Lebanon-based artist's exhibition is, he says, “an invitation to reconsider truth as multiple. To change. To engage. And to share. It presents grounds for the validity of our collective fictions and creates new grounds for shared realities to come."

Art from science

Haleh Fotowat, “Multicellularity II: (oil and charcoal on unprimed canvas), by Heleh Fotowat, in her show “Multicellularity,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, Jan. 29-Feb. 27.

Art from science! She is also a staff scientist at Harvard’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, in Cambridge.

She tells the gallery:

"Inspiration for this body of work comes from unpredictability, urgency, continuity, beauty, humor, and enthusiasm that is omnipresent in all forms of life. My painting process consists of spontaneous, uninhibited drawing of shapes, trajectories, words, and numbers, usually with a pen or pencil. I often listen to improvised jazz music while I work, letting my hand go free and move as it needs to. I sometimes even dance. Then I add paint, going back and forth between drawing and painting. I watch, listen to, and encourage conversations between individual elements that surface as I go along, as they form a coherent 'multicellular life form.’’’

Hannah Leighton: The growing farm-to-campus movement in New England

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

“Farm to campus” is a growing movement to mobilize the influence and power of colleges and universities to shape the food system. Research done before the COVID-19 pandemic shows that New England colleges with dining services served more than 87 million meals and spent nearly $400 million on food and beverage annually. Decisions about what food to buy, where to buy it and from whom help shape supply chains, affect the health and nutrition of those eating at the institutions, and can support the communities of which the institutions are an integral part. In addition, colleges and universities are educating and shaping opportunities for future food systems leaders, food businesses and food consumers.

Farm to Institution New England (FINE) works with the higher-education sector to better understand and help shape the role higher ed plays in our food system. The pandemic has hugely impacted college dining and food systems work. Campuses face supply-chain disruptions, staff shortages, closed dining halls and new levels of food insecurity in their communities. But as they have grappled with these disruptions over the past two years, they have also leaned on the years of partnership and collaboration with local food partners to get through this trying time. For FINE and our partners, we know that in order to continue building this foundation, we must ground our work in evidence and understanding of the changes.

As FINE and our campus partners geared up to assess the current state of farm-to-campus activity in the six New England states, we developed an innovative approach to data collection and sharing. This month we are launching the New England Farm and Sea to Campus Data Center, a new system for collecting, measuring and reporting farm-to-campus work.

The Data Center will be the one-stop shop for New England colleges to aggregate information about farm-to-campus efforts, generate reports, measure progress over time, network with other campuses, and more.

The Data Center will build on and streamline the data-collection process and decentralize data ownership across multiple stakeholders.

Multiple campus stakeholders will be able to enter data specific to their area of the food system. This includes:

Dining directors, managers and chefs

Campus farm managers

Food access/security leaders on campus (e.g., food pantry, student union, student-led food justice organizations).

Campuses will find questions about their general dining services, regional and sustainable food procurement, campus farms, food security efforts, tracking and traceability, community engagement and more. They will be able to share their results with administrators and other stakeholders while also benchmarking themselves in the region and finding new partners.

New England colleges with dining services can expect to receive an email in January with further instructions on how to log in and get started. In the meantime …

Get data points ready. FINE will start collecting them this month.

Get tracking support as you’re collecting your data. The beta version of FINE’s new purchase tracker is available free to anyone looking for support with their regional and values-based procurement tracking. It even comes with a handy calculator. More functionality coming soon (Google or Excel).

View a demo and find other resources on FINE’s website.

Over the coming year, the Data Center will also be where FINE hosts analyses and summary data, interactive dashboards and other opportunities for policymakers, funders, researchers and farm-to-institution stakeholders to better understand the landscape we’re trying to positively impact. While this beta version is being launched in the campus sector, other institutions will eventually be able to use this space to network, find supply chain partners and see how their activities compare with others in the region.

FINE has collected data from New England colleges with dining services via survey since 2015. These surveys have resulted in two reports: “Campus Dining 101: Benchmark Study of Farm to College in New England” and “Campus Dining 201: Trends, Challenges, and Opportunities for Farm to College in New England.” Findings from these efforts have informed regional funders, policy makers, researchers and others who support farm-to-institution projects across New England.

Hannah Leighton is director of research and evaluation at Farm to Institution New England.

Deeply rooted in the Hood

“Deeply Rooted in the NeighborHOOD, homage to Allan Rohan Crite” by Black muralists Johnetta Tinker and Susan Thompson, at 345 Blue Hill Ave., Boston, through Feb. 10

This is the third and final installation of “Mentoring Murals,’’ sponsored by Greater Grove Hall Main Streets, which "seeks to showcase the work of local artists {and} amplify the importance of maintaining a vibrant Black arts community".

And you can wear a beret

The University of Massachusetts’s burgeoning flagship campus, in the Connecticut River Valley in Amherst, looking southeast.

— Photo by Viking1943

{Amherst is} the last place in America where you can find people who think politically correct is a compliment…probably the only place in the United States where men can wear berets and not get beaten up.’’

Madeleine Blais (born 1946), journalist and professor at UMass Amherst, in In These Girls Hope is a Muscle (1995).

Amherst is best known now for UMass and Amherst and Hampshire colleges. The Connecticut Valley is thick with colleges, from Connecticut up to Dartmouth College, in Hanover, N.H.

Fayerweather Hall at Amherst College.

— Photo by Kenneth C. Zirkel

Philip K. Howard: How to fight back against the forces that are tearing apart America: End the ‘vetocracy’

Trump supporters crowding the steps of the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021 as they prepare to force their way into it to try to overturn the election won by Joe Biden.

— Photo by TapTheForwardAssist

NEW YORK

What can we do about our country? That’s the question I hear most often. Washington is mired in a kind of trench warfare, with no prospects of forward movement. And Americans today can be divided into two camps: discouraged or angry.

Americans are retreating into warring identity groups as extremists demand absolutist solutions to defeat the other side. It’s nighttime in America.

Yet, Americans still share basic values of self-reliance, tolerance and practicality, surveys show. Put Americans in a crisis, and unfailingly they put themselves on the line to help their fellow citizens, as essential workers did during the COVID-19 lockdowns.

Do we really hate each other? I don’t think so. We’re being forced apart by organized forces that profit from polarizing the country.

Extremists have the stage, and are relishing their new power to cow reasonable people into unreasonable positions — whether to deny the results of elections or benefits of vaccines, or to demand that most Americans wear hair shirts because of the sins of their ancestors.

Political insiders are manipulating extremism to their own goals. Political parties no longer compete by accomplishment but by stoking fears that the other side is worse.

The bottom line: Washington will not pull America back from the extremist precipice.

New leaders are obviously needed. But new leaders are not sufficient. Remember that Barack Obama promised “change we can believe in.” When that didn’t work out, frustrated voters (albeit with almost 3 million fewer votes than Hilary Clinton got) elected his polar opposite, Donald Trump, who promised to “drain the swamp.” Nothing much changed except more frustration, leading to greater extremism.

A new governing vision is needed – one that appeals to common interests while also responding to our frustrations. To talk polarized Americans off the precipice, we must understand how we got to the edge of this cliff.

The root cause of extremism, throughout history, is often a sense of powerlessness. Humans have an innate need for self-determination and opportunity. Can you do and say what you think makes sense? If not, sooner or later, you will want to break out. The Tea Party, Occupy Wall Street, Black Lives Matter, Stop the Steal: All these recent movements are ignited by a sense of powerlessness.

Government controls decision-making

What Obama and Trump failed to comprehend is this: The operating philosophy of modern government does not honor the role of human judgment in social activities. Instead of providing an open framework of goals and principles, activated by people taking responsibility, government strives to supplant human agency altogether.

At every level of society, Americans have been disempowered from making the choices needed to move forward. The operating structures of modern society are versions of central planning – dictating exactly how to do everything.

Why do Americans feel powerless? Because they can’t make a difference, and neither can their elected officials.

A new governing vision is needed to address this powerlessness. What I propose is to restore the human responsibility model that the Framers envisioned. As James Madison put it, giving responsibility to “citizens, whose wisdom may best discern the true interest of their country.”

Law should set goals and boundaries, but leave implementation to responsible people. Our protection from bad choices is accountability, not mindless compliance. "No man is a warmer advocate for proper restraints," George Washington wrote, but you cannot remove “the power of men to render essential services, because a possibility remains of their doing ill.”

Building an open governing framework activated by human responsibility is not difficult – it’s far easier to articulate goals than to dictate the details of implementation. Look at any organization or agency that works tolerably well, and you will find people focusing on the goals, not legalities.

But this new governing vision represents a radical departure from the status quo. No longer can bureaucrats avoid responsibility by being sticklers for rules. No longer can one lousy teacher or loud parent get what they want by demanding their rights. People in charge will actually be in charge, and will be empowered to act on their judgment. Other people will be empowered to make the judgments to hold them accountable.

America has become a 'vetocracy'

The federal government will never return willingly to a governing philosophy built on the foundation of human responsibility. All the detailed rules and red tape may prevent forward progress, but they empower insiders to block anything they don’t like. The power in Washington is the power of veto – a governing structure that political scientist Francis Fukuyama calls a “vetocracy.”

Change must come from the outside. The vision for change is to replace red tape with human responsibility. Let Americans use their judgment again. Instead of compliance, give people freedom to hold others accountable.

This is how a free society and democratic government is supposed to work. Instead of driving Americans into warring camps by trying to force one conception of the good, this vision can unite Americans by empowering them to shape their own conception of the good within broad legal boundaries.

Allow Americans to make things work again, and the darkness will soon turn into morning.

Philip K. Howard, a lawyer, author, New York civic and cultural leader and photographer, is founder and chairman of Common Good, a legal- and regulatory-reform nonprofit organization. His latest book is Try Common Sense: Replacing the Failed Ideologies of Right and Left. Mr. Howard is a friend and former colleague of New England Diary’s editor, Robert Whitcomb, who has worked on several Common Good projects in the past.

David Warsh: Nobel economics prize committee needs to look at the lessons of the 2008 crisis

Lehman Brothers headquarters in New York before the firm’s bankruptcy in September 2008 sent the world into the worst financial panic since the Great Depression.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It was a substantial responsibility the government of Sweden licensed when, in the 1960s, it gave its blessing to the creation of a prize in economic sciences in memory of Alfred Nobel, to be administered by Nobel Foundation and awarded by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. That bold action wasn’t easy, but it was as easy as it would get.

The Cold War smoldered ominously between two very different systems, “capitalist” and “communist.” In the West, the prestige of the Keynesian revolution was at its height, compared by some historians of science to the Darwinian, Einsteinian, Freudian and quantum revolutions. And the Science Academy possessed seventy-five years of experience as administrators of the physics and chemistry awards that were among the five prizes mandated by Nobel’s handwritten will.

Since 1969, when the first economics prize was awarded, the committee that oversees it has done pretty well, at least in the judgment of those who have followed the program closely. The Nobel system has imposed a narrative order on various developments since the 1940s in an otherwise fractious profession, often by recognizing its close neighbors. Goodness knows where we in the audience would be without it – still reading Robert Heilbroner’s The Worldly Philosophers, perhaps, first published in 1953, as though nothing since had happened.

Now, however, the Nobel Prize in economic sciences is facing a crucial test. The authorities need to give a prize to clarify understanding inside and outside the profession of the events of 2008, when emergency lending and institutional restructuring by the world’s central banks halted a severe financial panic. What might have turned into a second Great Depression was thus averted. Governments’ responsibilities as lenders of last resort were the heart of the issue over which Keynesians and Monetarists jousted for seventy-five years after 1932.

Either the Swedes have something to say about what happened in 2008, not necessarily this year, but soon, or else they don’t. Their discussions are well underway. The credibility of the prize is at stake.

The Nobel committees that administered the prizes in physics and chemistry faced similar problems in their early years. When the first prizes were awarded, in 1901, well-established discoveries dating from the 1890s made the decisions relatively noncontroversial – the discovery of x-rays, radioactivity, the presence of inert gases in the atmosphere, and the electron. Foreign scientists were invited to make nominations; Swedish experts on the small committees, several of them quite cosmopolitan, made the decisions. The members of the much larger academy customarily accepted their recommendations.

But a pair of scientific revolutions, in quantum mechanics and relativity theory, soon generated “problem candidacies” that took several years to resolve. Max Planck, first seriously considered in 1908 for his discovery of energy quanta, was final recognized in 1918. Albert Einstein, first nominated in 1910 for his special relativity theory, was recognized only in 1921, and then for his less important work on the photo-voltaic effect.

It is thanks to Elisabeth Crawford, the Swedish historian of science who first won permission to study the Nobel archive, that we know something about behind-the-scenes campaigns among rival scientists that underlay these decisions. Overlooked altogether may have been the significance of the work of Ludwig Boltzmann, who committed suicide in 1906.

The economics committee has what it needs to make a decision about 2008. The Swedish banking system suffered a similar crisis in the early Nineties and dealt with it in a similar way. Fifteen years later, Swedish economists paid close attention to what was happening in New York and Washington,

In 2017, in cooperation with the Swedish House of Finance, the committee organized a symposium on money and banking, at which the leading interpreters of the 2008 crisis contributed discussions. (You can see here for yourself some of the sessions from that two-and-half day affair, but good luck making sense of the program. That’s what the committee exists to do – after the fact.)

A previous symposium, in 1999, considered economics of transition from planned economies, and wisely steered off. No such inquiry was required to arrive the sequence of prizes that interpreted the disinflation that followed the Volcker stabilization – Robert Lucas (1995), Finn Kydland and Edward Prescott (2004), Thomas Sargent and Christopher Sims (2012) – a process that unfolded more slowly and less certainly than the intervention of 2008.

The money and banking prize should be understood as fundamentally a prize for theory. For all the talk in the last few years about the rise of applied economics, the Nobel narrative, at least as I understand it, has emphasized mainly surprises of various sorts that have emerged from fresh applications of theory, in keeping with Einstein’s dictum that it is the theory that determines what we can observe.

Some of these applications may have reached dead ends, leading to new twists and turns. The advent of cheap, powerful computer and designer software in the Nineties handed economists a power new tool, and two recent prizes have reflected the uses to which the tools have been put – devising randomized controlled tests of economic policies, and drawing conclusion from carefully-studied “natural experiments.” But otherwise “the age of the applied economist” may be mainly a marketing campaign for a generation of young economists eager to advance their careers. It won’t be an age in economic science until the Nobel timeline says it is.

As a journalist, I’ve covered the field for forty years. My impression is that many exciting developments have occurred in that time that have not yet been recognized, some of them quite surprising, many of them reassuring. As the Nobel view of the evolution of the field is revealed in successive Octobers, the effect may be to buttress confidence in the field and diminish skepticism about its roots – or not. As for natural experiments, it is hard to beat the events of 2008. The Swedes have many nominations. What they must do now is decide.

David Warsh, an economic historian and a veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first appeared.

Chris Powell: Amid most infections ever, time to reappraise pandemic policies

Graphic of COVID-19 infection by Colin D. Funk, Craig Laferrière, and Ali Ardakani.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut doesn't audit the performance of any of its major and expensive state government policies -- not education, not welfare, not urban -- but now would be a pretty good time for state government to audit its response to the virus epidemic.

For the epidemic has consumed nearly two years of state government's focus, impairing everything important -- commerce, schools, mental health, social order and basic liberty and democracy themselves -- only for all official efforts to fail to stop the spread of the virus. New daily confirmed cases in Connecticut in the last week averaged almost 4,000, the most yet, and weekly "virus-associated" deaths are double what they were only a few weeks ago.

An increase in infections might have been expected as colder weather pushed people closer together indoors and because of the holidays. But then a decline in infections also might have been expected because of the state population's high degree of vaccination and face-masking -- that is, might have been expected if vaccines and face-masking really work as promoted.

But even government and government-friendly medical officials admit that the vaccines are quickly losing effect. Needing frequent "boosters," they aren't half as good as traditional vaccines, and there is growing concern that too many "boosters" may damage the human immune system.

This doesn't mean that the vaccines and masks haven't helped or that the epidemic might not be worse without them. It means that another approach to the epidemic is necessary -- greater emphasis on therapies, of which there are many, and not only the antiviral pills just developed by pharmaceutical giants Pfizer and Merck, which, like the vaccines themselves, are not yet adequately tested and thus full of risk.

Even government-friendly medical authorities acknowledge the correlation between virus infection and deficiency in Vitamin D, the "sunshine vitamin," especially in people with dark complexions, and many authorities recommend strengthening the immune system with Vitamin D and C and zinc supplements. Natural and manmade antivirals and anticoagulants abound and many studies have found them effective against the virus, especially if administered soon after infection.

Unfortunately at the outset of the epidemic, when medicine did not understand the virus, patients were commonly told only to go home and take cold medicine and return to a doctor or hospital if their symptoms worsened. But when their symptoms worsened, it was often too late to save them.

Now treatment is more sophisticated. On any particular day infections in Connecticut may increase by thousands but hospitalizations and deaths by only a few. On some days infections soar but hospitalizations decline. Many infected people have no symptoms and nearly all people survive infection.

Even government-friendly medical authorities also acknowledge the correlation between virus fatalities and "co-morbidities" like obesity and diabetes, which most people could control.

Gov. Ned Lamont announced last week that state government soon will distribute, without charge, millions of masks and virus tests that can be taken at home. While the tests may be helpful, there is no shortage of masks and the virus penetrates them easily. It might be far better for state government to help people understand that their immune systems and general fitness may be defenses as good as if not better than masks and vaccines, and if state government distributed free immunity-boosting vitamins and supplements and even gym memberships.

State and local government officials and the medical authorities on whom they rely have done their best in circumstances that have no precedent in living memory. But their good intentions don't vindicate mistakes.

Despite lockdowns, mandatory masks, vaccines, "boosters," and damage to society that will not be repaired for many years, Connecticut and the country are facing more virus infections than ever. So government should start questioning its policies and assumptions about the epidemic, including the assumption that the epidemic is so deadly that combating it must take priority over all other objectives in life.

What isn't working needs to change, if only to set an example for the other things in state government that, after long experience, don't work except to sustain the government itself.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Can we save ourselves?

— Photo by Googleaseerch

When the wind works against us in the dark,

And pelts the snow

The lower chamber window on the east,

And whispers with a sort of stifled bark,

The beast,

‘Come out! Come out!’—

It costs no inward struggle not to go,

Ah, no!

I count our strength,

Two and a child,

Those of us not asleep subdued to mark

How the cold creeps as the fire dies at length,—

How drifts are piled,

Dooryard and road ungraded,

Till even the comforting barn grows far away

And my heart owns a doubt

Whether 'tis in us to arise with day

And save ourselves unaided.

‘‘Storm Fear,’’ by Robert Frost (1874-1963)

‘Only what my consciousness allows’

“The Uncertainty Principle” (graphite and acrylic on canvas), by Newton, Mass.-based Frank Capezzera, in his show “The Self as Universe: Figurative Musings in Cosmology (or the All-Compassing Universe)” Jan. 22-Feb. 27, at Galatea Fine Art, Boston.

He tells the gallery:

"...This series of paintings was developed through my amateur enthusiast’s reading of current cosmological subjects … including Newtonian and Einsteinian physics, quantum mechanics, mathematics, and astronomy from the Big Bang to the emergence of modern human consciousness. I contemplate the elementary debris of stars becoming organized into rocks, then one cell organisms and now human consciousness and self-awareness able to pose limitless questions about everything, including ‘is death the end?’

“The range of images in some of the paintings is among the very large (galaxies, nebulae, stars) or the very small (electrons, quarks, and other subatomic characters of what’s called the Standard Model) and human scale, that which we relate to intuitively. The paintings contain remnants of symbology, both mathematical and anthropological ideograms, such as kanji. For example, the Japanese kanji meaning ‘all-encompassing universe’, sometimes referred to in Aikido, either appears in the paintings or was used as an ‘armature’ for the construction of figures.

“The paintings, two dimensional in charcoal and paint, result from personal musings on how the universe might fit together including (1) how the very large (galaxies) and the very small (subatomic quanta) and gravity work together and (2) will there be anything left of me after I die? As I write this I know only what my consciousness allows. Strangely, what might be scary feels like the way for me to go. I feel as if I am crossing into the zone within myself to contemplate unknowable answers to questions in a new and evolving art-making experience."

Happy in Connecticut

Seal of Southbury, Conn

"I came to Southbury because I wanted to live a more simple life. When I was a child, I saw lots of movies about happy people living in Connecticut. And ever since then, that was where I wanted to live. I thought it would be like the movies. And it really is. It's exactly what I hoped it would be.’’

— Polly Berger (1930-2014), actress, singer, writer and TV host

Audubon Center Bent of the River Trail in Southbury.

—Photo by Karl Thomas Moore

More and smaller

Need more like this.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

There’s a bad “affordable housing” problem in Rhode Island, as in many other states, most famously in California. But the state does have some assets, for example, hotels that are closing because of what appears to be a permanent drop in business travel. Most of these could be converted to temporary and/or permanent housing.

Consider the former Cru Hotel at T.F. Greene International Airport. It’s being converted to a 181-unit building for workforce housing.

Closed schools, though more challenging to retrofit, also offer space for housing.

Meanwhile, zoning laws need to be revised to allow more and denser housing to be constructed, boosting supply and thus reducing cost pressures. This should include letting people put up “little houses” in backyards for family members in places where zoning now forbids it. And loosening some local rules mandating a large number of parking spaces as a requirement with housing construction would help, too.

Rhode Island remains the second-most-densely populated state, after New Jersey, another reminder of its housing challenges.

An ‘ordeal’ only to some

“Surely the framers of the Declaration of Independence did not have Vermonters in mind when they declared ‘all men are created equal,’ and the ordeal of winter in northern New England violates the national credo of equal justice for all.’’

Charles T. Morrissey, in Vermont: A History

‘Think of an egg’

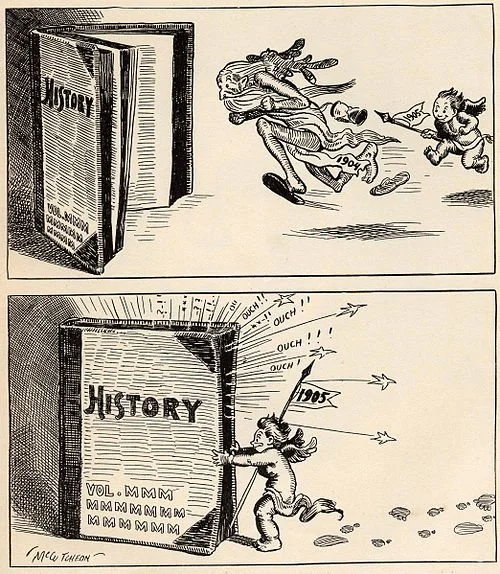

Baby New Year 1905 chases old 1904 into the history books in this cartoon by John T. McCutcheon.

“This is the beginning.

Almost anything can happen.

This is where you find

the creation of light, a fish wriggling onto land,

the first word of Paradise Lost on an empty page.

Think of an egg, the letter A….’’

— Billy Collins (born 1941). This Holy Cross graduate was twice the U.S. poet laureate.