Poetic ‘predicaments’

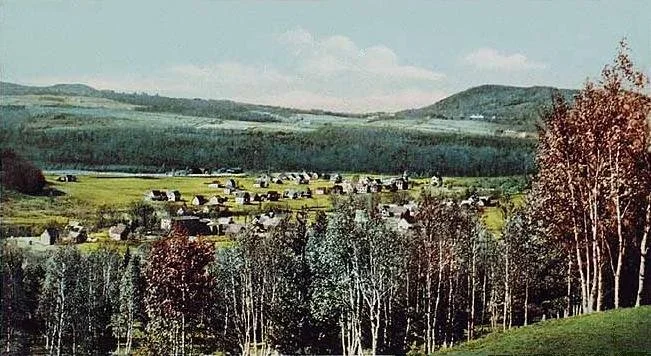

Franconia Village with Sugar Hills background, circa 1908

“….I think

”I see the parts—haze, dusk, light

broken into grains, fatigue,

the mineral dark of the White Mountains,

the wavering shadows steadying themselves—

separate, then joined, then seamless:

the way, in fact, Frost's great poems,

like all great poems, conceal

what they merely know, to be

predicaments….”

— From “On the Porch at the Frost place, Franconia, NH,’’ by William Matthews (1942-1997)

Ben Franklin, ecologist

Breeding male Brewer's blackbird.

— Photo by JerryFriedman

“In New England, they once thought blackbirds useless, and mischievous to the corn. They made efforts to destroy them. The consequence was, the blackbirds were diminished; but a kind of worm, which devoured their grass, and which the blackbirds used to feed on, increased prodigiously; then, finding their loss in grass much greater than their saving in corn, they wished again for their blackbirds.”

— Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), a U.S. founding father and polymath. He was born and raised in Boston, which he left at 17 to move to Philadelphia.

David Warsh: On why 'not every couple should have a pre-nup'

“The Marriage Contract,’’ by Flemish artist Jan Josef Horemans the Younger, circa 1768

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The annual meetings of the American Economic Association convention unfolded over the weekend, on Zoom. In Boston, where AEA members had hoped to meet in person, it snowed. After I shoveled (and read the news from Kazakhstan), I went through the motions, watching half a dozen sessions over two days, all of them interesting, none of them possessing the elusive quality of newsworthiness, at least where my column Economic Principals is concerned, given the rest of the work at hand.

So I turned instead to two more deliverable items of interest: the Kenneth J. Arrow Lecture at Columbia University, which David Kreps, of Stanford University’s Graduate School of Business, delivered in Manhattan last month; and an intriguing new paper by William A. Barnett, of the University of Kansas, editor of Macroeconomic Dynamics and first president of the Society for Economic Measurement.

. xxx

Kreps, described by Columbia’s José Scheinkman as “one of the most accomplished theorists of our generation” (“and our generation wasn’t bad”), spoke under the title “Not Every Couple Should Have a Pre-Nup: How the Context of Exchange and Experience Affect Personal Preferences, and Why This Matters Both to Economic Theory and to Practical Human Resource Management.” The reference is to a long ago BusinessWeek column by the late Gary Becker, of the University of Chicago.

If a contract were required before a couple could legally marry, Becker argued, no bad vibes or stigma would attach to divorce. Not so fast, Kreps countered. There was abundant reason to suspect that preferences are not fixed; that such contracts might interfere with their evolution over the course of a marriage. He proceeded to carefully sort through the implications, in the manner he learned as a close reader of Arrow.

Since the World War II, mainstream economics had become “mathematical,” Kreps said. Everyone understood what he meant: formal models had become the standard means of professional discourse. Developments then came in two broad waves. The first wave, between 1945 and 1970, developed choice theory, price theory and general-equilibrium theory, he said.

The second wave, beginning in 1970 and not over yet, consisted of information economics: “getting serious about the formation of beliefs, especially beliefs about the actions of other economic agents (and how they will react to your own actions).”

“It is well past time for the third wave,” he continued, “Getting serious about preference-determination and preference-evolution.” He connected the movement to concerns that Arrow had expressed as long as fifty years ago. He cited a couple of present-day books as serious curtain-raising work – Identity Economics: How Our Identities Shape Our Work, Wages, and Well-Being, by George Akerlof and Rachel Kranton; and The Moral Economy: Why Good Incentives Are No Substitute for Good Citizens, by Samuel Bowles. And he elaborated his own views, “as a commentator, not an originator” – of the extensive careful modeling and testing that would be necessary to establish preference formation as a contribution to serious economics.

On “shaky grounds,” Kreps concluded, “I contend that taking more seriously how preferences are affected by context and experience within context, will— on net — be good for our discipline.” Joseph Stiglitz, of Columbia University, contributed a lively discussion.

All the more reason then, to tune in, when you can, to the Distinguished Lecture that Nathan Nunn, of Harvard University, delivered to the AEA meetings on Friday. A recording of “On the Dynamics of Human Behavior: The Past, Present, and Future of Culture, Conflict, and Cooperation” presumably will be available for free viewing on the AEA Web site in a day or two. If you like this sort of thing, it is definitely worth the wait.

. xxx

Barnett is less well-known in the profession than is Kreps, but he is an unusually interesting gadfly, a talented outsider with a knack for connecting with talented insiders over the course of a long career. Trained as a rocket scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he spent most of the 1960s at Rocketdyne in suburban Los Angeles before leaving in 1969 for Carnegie Mellon University, and a PhD in statistics.

After seven years in the Special Studies Section of the Federal Reserve Board, a unit since abolished, Barnett left with the conviction that instead of depending on classical accounting procedures, the central bank should be using modern methods devised in the 1920s by the French economist François Divisia. a founder of the Econometric Society, and not well-understood by Anglophone economists until 1973. Erwin Diewert, of the University of British Columbia, suggested employing a class of index numbers. known as “superlative” indices, as a suitable alternative to the Fed’s accounting aggregates. Barnett continued to advocate an approach known as the Törnqvist-Theil Divisia index. (Elaboration added)

In 2012, MIT Press published Barnett’s Getting It Wrong: How Faulty Monetary Statistics Undermine the Fed, the Financial System, and the Economy. He has been lobbying for the change (the “Barnett Critique”) ever since, first at the University of Texas, then Washington University, and, since 2002, at the University of Kansas. He was a founder of the Center for Financial Stability, a Manhattan-based think tank, and is director of one of its programs, as well.

Last week a paper by Barnett and four others circulated widely on the Internet. “Shilnikov chaos, low interest rates, and New Keynesian macroeconomics,” from the latest Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, was sufficiently interesting that Barnett arranged to have it published open access online. “[I]t might be very important,” he wrote.

I wrote back to say that Shilnikov chaos attractors were well above my paygrade. Barnett replied in plain English:

We have another paper about how to fix the problem. It isn’t difficult to fix. The source of the problem is that attaching a myopic interest rate feedback equation (Taylor rule) to the economy’s dynamics without a long run terminal condition alters the dynamics of the system to produce downward drift in interest rates. Our results produce an amazing match to the 30-year downward drift of interest rates into the current liquidity trap. The solution is for the Fed also to have a second policy instrument to impose a long run anchor (no surprise to the ECB). Since the short run interest rate is useless as a policy instrument at the zero lower bound, central banks are now experimenting with other instruments. It would have been better if they had done that before interest rates had drifted down into the lower bound.

That wasn’t hard to understand at all, at least intuitively. Ever since William Harvey in 1628 demonstrated the heart’s circulation of the blood, economists, from John Law and François Quesnay to the designers of today’s flow of funds accounts, have sought to understand the mysteries of the economy’s circular flow of money, products and services. Though never a boatswain, I have had enough experience anchoring boats in sometimes powerful currents to recognize the virtues of having more than one anchor out, sometimes in a completely different direction.

The last fifty years have been a wild ride for the Fed’s managers of the world’s money. Don’t expect to enter a quiet harbor any time soon.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

William T. Hall: An island’s crucial boat and the widow’s fish

On the beach with a Block Island Double Ender

— Watercolor by William T. Hall

Block Island is a small landmass shaped like a pork chop 16 miles off southern Rhode Island. It’s where my father was born, in 1925. His entire family were fisherfolk. He got his start fishing at age 10.

Historically, the old salts depicted in the marine art and stories of the past were men, but the wives, mothers and daughters of island fishermen were essential to the life of any Block Island family that made its livelihood from the sea.

Of course, as usual, women saw to all the usual unsung details of daily life in the home and spiritual life in the community, but little remembered today is the extent of the decisions made, and physical labor provided by island women, and how important that was to their family’s survival and success.

Long before my father was born, the indigenous tribes and white settlers on the island took to the sea for their livelihood. They first had to overcome the major geological disadvantages of the island. The high bluffs and open ocean exposure on the southeast corner of the island were perilous, and to the north at North Light were the shallows off Sandy Point that still claim lives of surf fishermen today. These were daunting and dangerous obstacles. For many years the shores of Block Island challenged captains with hazardous approaches and no reliable anchorages.

Progress through adversity

Consider the challenge of designing boats to use at Block Island. For many years, the “perfect Block Island boat’’ was dreamed about, prayed about and then modeled out of wood. It occurred to the early settlers that the way to create a seaworthy vessel on a beach had already been invented by the Celts and Vikings . With a foggy notion of history and woodworking skills barely sufficient to fabricate a house, the new islanders patched together their own unique surf-wise boat. The design was not beautiful, but it was practical because it was based on two important borrowed principles from sea-faring people many hundreds of years before.

It should be sturdy, with two sharp ends for launching from beaches and surviving a following sea when landing. It should have a sail arrangement

best described as “simple and flexible.” It allowed for two small sails, which when reefed down, looked like oversized canvas handkerchiefs. These design considerations proved essential to moving the boats around rocks, then from high cresting waves down onto safe sandy beaches.

The most important aspect of this design was that the boats could be launched into the surf and retrieved from the brine by a small group of men and, yes, women, often with the help of oxen, horses, mules and mechanical hauling contraptions called “capstans”.

This homely workboat was a dory called “The Block Island Double Ender”. It could be launched from the beach into the morning surf and then brought back at night through a different tide, to be stored high up in the dunes safe from northerly storms. This kind of boat varied from 22 to over 36 feet long and was weighted by fieldstones for ballast that would be thrown overboard to balance the weight of a daily catch. The boat was destined to become the mainstay workboat for the island from before the American Revolution but eventually, of course, was made obsolete by steam and gasoline engines.

The stories of the colorful fishermen who manned these seaworthy boats earned them a certain notoriety with many world-class sailors. The boats form a deep mythology as colorful as the exploits of the gods on Mt. Olympus. They had names such as Dauntless, Island Bell and Bessie, I, II and III. There were perhaps as many as 50 boats built and launched from coves around the island. One such beach is even named “Dories Cove”.

For over 200 years, they faced Neptune’s furry and a vengeful Old Testament God, as they fished a bountiful sea around Block Island. Then, over just a few decades, the boats melted away. The end of these boats was ignoble. Finally abandoned by the careless hands of progress, their exposed ribs and rigging melted into the island’s underbrush and rose-hip bushes. It was said by a Civil War veteran, “Only those who had witnessed soldiers left unburied after a battle can feel the shame at the sight of this wasteful demise”.

The holiest of testaments paid to Block Island Double Enders was repeated by the captains who had fished in them, “With all that time and everything they went through, only one boat was ever lost to the sea”. Is it true? As an owner of an original reproduction of this wonderful boat I can only say, “It is possible”.

All along, women have played a part in the history of the island, its boats and its success as an island community. In the early history, when a man’s hand heaved at the side rails, or the harnesses of the

oxen, female voices as well as men’s voices were heard shouting as they all pulled in unison with the men. Every able-bodied fisherman, woman, boy and elder was needed to launch and retrieve the boats of the fleet each day.

Women also helped with maintenance, sail repair, outfitting, marshaling supplies, cleaning the catches, gathering and managing bait, all while feeding their families and sharing child-care.

Some women were on the beaches for much of the day waiting for the boats to return. And some women might ride the family mule back to work in their gardens, feed livestock and hang laundry while they kept an eye on the horizon for their family boat to come into sight. Some made stews and chowders and roasted potatoes in the coals of beach fires while they waited. Some cared for the oxen and set wire minnow traps in the salt estuaries. Some dug quahogs for bait from the wet sand on the lower parts of the beaches for the next day’s bottom fishing. \

When the boats were out the women were assisted by old men and school-age boys and girls, before and after school. Young girls helped the working mothers by babysitting the youngest children, tending stew pots, mending nets and making clothing. The women’s contribution would be universally appreciated on Block Island and earn them an equal place in the fabric and soul of the island.

At the time when my father was young many things had changed. Commercial fishing had become totally the purview of men, often symbolized artistically by heroic images of stalwart captains on mammoth commercial fishing boats. By this time, most daughters of fishing families were educated and provided such services on the island as teaching, nursing, real estate, bookkeeping, town business, cab driving and tourism, to mention only a few.

Regardless of these changes, appreciation of women’s role on the island continued. Quiet acknowledgement by giving shares to those who contribute became a tradition in my father’s generation called simply “The Widow’s Fish”.

Although difficult to translate directly, it means always making sure that all the elder and/or widowed women still living on the island would receive fish from every day’s catch. It was standard for every fisherman and farmer on the island to share part with those in need with little fanfare. Sermons in the island’s churches, grace said at daily meals, dedications at public benedictions and remembrances of departed fishing folks were often framed around the notion of “sharing and appreciation,’’ including the crucial role that women played.

I remember this quiet homage paid by my father during our summer vacations, from Vermont, on the island. Although he had migrated off the island to work as a salesman and gentleman farmer, we vacationed on the island, visiting relatives and friends and fishing daily on boats owned by relatives.

One day we had caught more flounder than we could eat, and my father made sure to separate out the catch into portions or “shares”. In that bounty was a special offering, something he called, “The Widow’s Fish”. He always put that portion aside during the filleting. All the harbor’s fishermen had one or two additional people outside their immediate families who were living alone and as Father would say “are living a little closer to the bone than we are”.

In those days, he’d leave the boat and go up the dock to the phone booth by Ernie’s Restaurant. There he’d call a prospective list of names to ask if they could use some flounder, bluefish, fluke, black bass and occasionally

Swordfish. (The last were getting scarce in those days.) I remember the names on his list -- Ida, Annie Pickles, Aunt Annie Anderson, Blanche Hall and Bea Conley. These were elderly ladies whose homes we often visited on the way home with pails of filleted fish.

As I later found out, my father, when he was a teenager, had often crewed as a deck hand or swordfish striker for the husbands of the ladies we visited. All or most of the men were captains who operated fishing boats that Dad had worked on before he went into the Army, in 1944. It wasn’t until later in life I found out there was an added depth to my father’s gratitude.

In those old days these women had found a way to stretch many of their own family meals so that my father, orphaned at age seven, could stay for dinner.

These grateful ladies of the island formed a matriarchal umbrella of love and service to each other and their community. They always remembered my grandmother Suzie Milliken, whom some fondly called “Sister Suzie,” through a custom they referred to as “calling her to the room’’. The expression was used from Victorian times to mean connecting with a departed soul in a séance. As they thanked and hugged my father, they tearfully called him by the boyhood nickname Suzie had given him.

“Billy,’’ they assured him, “Suzie, would be proud of you for remembering to bring us our fair share”.

William T. Hall is a painter, writer and former advertising agency creative director based in Florida and Rhode Island.

Fishermen at the long-gone fish market co-op building at Old Harbor, Block Island, in the ‘40s.

— Photo courtesy of George Mott

Chris Powell: $75 million could be spent better; stop hysteria over COVID home testing

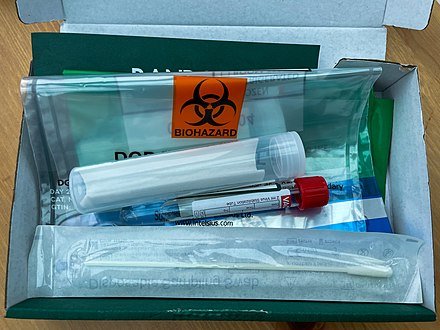

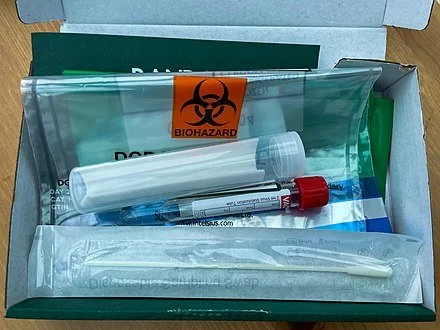

COVID-19 home test kit.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont could have found worse things to do with the $75 million in federal emergency aid he ordered distributed last week as a bonus to poor households receiving the state's earned-income tax credit. On average those households probably have suffered more financially from the long virus epidemic, since many of their breadwinners hold, or held, the service-sector jobs that were the first to be cut back or eliminated.

Complaints from Republicans that the bonuses mainly will reward a constituency of the governor's party, the Democrats, as his re-election campaign begins are not so compelling. For nearly everything government does rewards some political constituency, and state law already had identified the earned income tax credit constituency as deserving. If Connecticut ever again has a Republican administration, it will be unusual if Republican-leaning constituencies -- if only ordinary taxpayers -- are not rewarded too.

The governor's dispensing that $75 million is troublesome for different reasons, starting with the disregard for democratic procedure.

The governor's office says the federal law that sent the emergency money to the state authorizes his administration to spend it on expenses incurred because of the virus epidemic. But the state has been paying its earned income-tax-credit obligations all along. No payments by the government were cut because of the epidemic. While many recipients surely suffered losses because of the epidemic, it's unlikely that all did, and no one receiving the bonus will have to show evidence of such losses. The expenses to be reimbursed here are merely being assumed.

Additionally, $75 million is a lot of money for state government to dispense out of the blue at the command of just one official, an amount never formally appropriated by the General Assembly. Indeed, as Republican legislators note, state law already had determined how much was to be spent on the tax credit. The bonus created by the governor overrides that legislation.

Since he still exercises -- at least until February -- emergency powers to rule Connecticut by decree, the governor presumably could have rewritten the tax-credit law by himself to authorize the bonus. But he did not do so, perhaps because it might have emphasized his gathering unnecessary power to himself.

Republican legislators note that Connecticut faces many other compelling needs apart from those of the tax-credit recipients and that ordinary democracy first would have summoned the legislature or legislative leaders to discuss how to spend the $75 million. That's why the governor's high-handedness here is another argument for letting his emergency powers expire.

Having continued for two years, the virus epidemic is no longer an emergency. While the epidemic will wax and wane as epidemics do, government is fully aware of what combating it may require. Most of all, combating it may require more medical facilities and staff, and thus, to finance them, fewer raises for government employees, fewer stupid imperial wars and that $75 million that instead will be spent to expand the tax credit.

That money might build a few hospital wards and hire more doctors, nurses, and auxiliary staff. It might buy and distribute antivirals and vitamins.

If the tax-credit bonus can be construed as an expense of the epidemic, surely expanding medical capacity and services could be construed similarly. With so much free money flowing from Washington, the federal government probably wouldn't object if Connecticut chose to get more relevant.

After all, unlike the tax-credit bonus, increasing medical capacity might benefit everyone who got sick.

Meanwhile government's frantic efforts to distribute home testing kits for the virus and the public's frantic efforts to obtain them seem misplaced.

Surely quite without a test most people can tell if they are sick with symptoms like those attributed to the virus, and surely most people with such symptoms might have enough sense to get to a doctor or hospital quickly, especially since early treatment of the virus is crucial to defeating it.

The people lately waiting in long lines for a home test kit for the virus well may be putting themselves at greater risk of contracting it. The virus is bad enough. Test hysteria induced by government will make it worse.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Video: 'Satanic mills' in two 'green and pleasant' lands

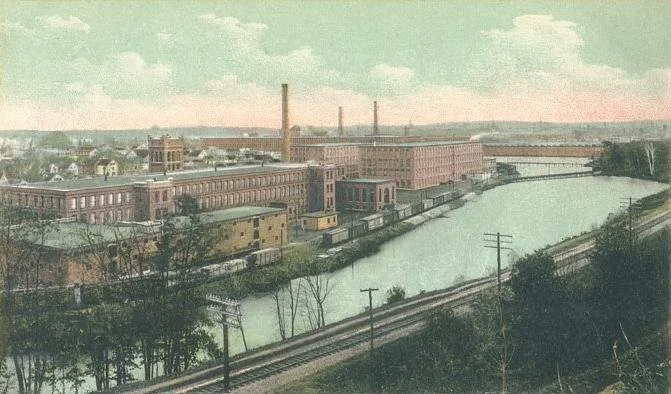

Arlington Mills, Lawrence, Mass., in 1907

A view of the Berkshires from near North Adams, Mass.

— Photo by jbcurio

Below is a local version of the weird, haunting English poem by William Blake called “Jerusalem,’’ written about 1804. It has long been best known as the hymn of the same name, with music written by Sir Hubert Parry, in 1916. (Remember the movie Chariots of Fire?)

Timmy May, of Newport, R.I., came up with the idea of inserting "New" before “England’’ in the three places where “England” appears in the original Blake poem.

The Industrial Revolution brought many, many “dark satanic mills,’’ first to England and then to its offspring.

Mr. May is on the left in the video below. The other musicians are Jamie Lawton, on violin, and Gregory Jonic, on uilleann pipes.

‘The refined grandeur’

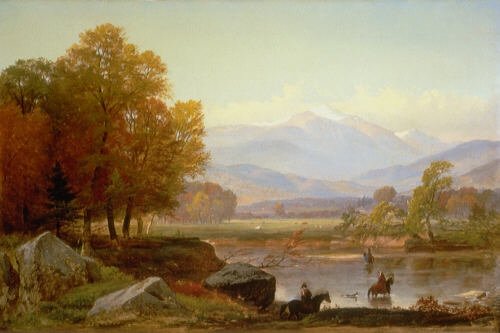

“Mount Washington,’’ by Samuel Lancaster Gerry (1813-1891)

“A visit to New Hampshire supplies the most resources to a traveler, and confers the most benefit on the mind and taste, when it lifts him above mere appetite for wildness, ruggedness, and the feeling of mass and precipitous elevation, into a perception and love of the refined grandeur, the chaste sublimity, the airy majesty overlaid with tender and polished bloom, in which the landscape splendor of a noble mountain lies.”

— Thomas Starr King (1824-1864), an American Universalist/Unitarian minister.

He was influential in California politics during the Civil War, and pressed to keep California rather than splitting off as a separate country.

He vacationed in New Hampshire’s White Mountains in the 1850’s while a minister in Boston and in 1859 published a book entitled The White Hills {Mountains}; their Legends, Landscapes, & Poetry.

Why New England has a certain coherence and consistency

The flag of the New England Governors Conference. The pine symbol has been associated with the region from early Colonial days. The wood was used for housing, boats and furniture. The nickname of the region’s most wooded state, Maine, is The Pine Tree State.

But the origin of the several similar New England flags also goes back to the Red Ensign of the Royal Navy, first used in 1625, with merchant vessels being granted its use by 1663. Shipping became a major part of the region’s economy early on.

“New England, unlike the rest of the United States and other parts of the world that were colonized by European powers, is a realized idea. The people who, from a European perspective, were its founders had envisioned that New England would continue a tradition in Christian history, and also political history, by becoming a plantation for Christianity in the “new world,” which would function as an autonomous republic.

New England was created by colonists who fanned out from that initial Massachusetts Bay colony. The colonists who were granted the charter for Massachusetts Bay were given small tracts of land. They created new colonies that were pulled together through the forces of economics and culture. So, the vision that shaped the beginnings of Massachusetts was stamped on the region as a whole. New England developed a consistency and coherence that much of the rest of the United States lacks.’’

—- Mark Peterson, a professor of history at Yale University, in an interview with Five Books

English explorer and soldier John Smith coined the name “New England’’ in 1616.

Dangerous footwear

“Winter” (1876) by Julius Sergius von Klever

“….the street

is too icy old women in pointy shoes

and high heels pass him their necks

in fur collars bent their eyes watch

their small slippery feet’’

— From “Winter Afternoon,’’ by Grace Paley (1922-2007). The poet and short-story writer lived in Thetford, Vt., from the early ‘90s to her death.

Main Street in Thetford in 1912.

Talking therapy in Brockton

“Conversation” (clay, graphite,), by Melissa Stern, in her show “Melissa Stern: The Talking Cure,’’ at the Fuller Art Museum, Brockton, Mass., Jan. 29-May 15.

The museum says that these witty (and sometimes unsettling) sculptures "are a spirited cast of characters formed in clay." The show takes its name from Sigmund Freud’s description of psychoanalysis, and centers on Ms. Stern’s 12 ceramic sculptures. The artist invited 12 writers to create inner monologues for each of the characters and 12 actors to perform them for audio recordings.

Brockton City Hall, which opened in 1892 during Brockton’s heyday as a center of manufacturing, especially of shoes.

Todd McLeish: Seeking strategies for sustaining bay scallops

Bay scallop staring at you with its blue eyes

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

In the Great Salt Pond on Block Island, native bay scallops are thriving like nowhere else in Rhode Island. Scientists from The Nature Conservancy survey the 673-acre tidal harbor every autumn and have recorded hundreds of scallops each year, despite as many as 50 recreational shellfishermen harvesting scallops from the pond each November and December.

The same cannot be said of the rest of the Ocean State’s waters, however, where bay scallops are few and far between.

On Block Island, Diandra Verbeyst leads a three-person team of Nature Conservancy scuba divers and snorkelers who monitor 12 sites around the Great Salt Pond. They have counted an average of 225 scallops annually since 2016, up from just 44 observed by previous observers in 2007, the first year of monitoring.

“There are slight rises and falls from year to year, but the population is pretty stable,” Verbeyst said. “Based on the 12 sites we monitor, the population is indicating that there is spawning happening each year, and there is recruitment to the population.”

In addition to scallop data, Verbeyst and her team also collect information on water quality and other environmental conditions during their surveys.

“The scallops are an indication that the ecosystem is healthy and doing well, and for me, that’s fascinating in itself,” she said. “No matter where you are in the pond, there’s a good chance you’ll see a scallop.”

Bay scallops are bivalve mollusks with 30-40 bright blue eyes that live in shallow bays and estuaries up and down the East Coast, preferring habitats where eelgrass is abundant. They are short-lived animals — most don’t live more than two years — and are significantly smaller than sea scallops, which are found farther offshore and are harvested by the millions by New Bedford-based fishermen.

Chris Littlefield, a Nature Conservancy coastal projects director and former part-time shellfisherman on Block Island, recalled collecting scallops as a child in the Great Salt Pond 50 years ago, and he has been gathering them in small numbers for his family’s consumption ever since. He said the scallop population received a boost in 2010, when immature scallops grown at the Milford {Conn.} Laboratory of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration were dispersed into the pond in a project funded by the Natural Resources Conservation Service.

“That project broke through some kind of threshold,” Littlefield said. “Scallops weren’t as abundant before that, and they used to be confined to certain key locations and that was it. But now they’re more abundant and more people are finding them and harvesting them.”

Unlike Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard and a few locations on Cape Cod and Long Island, where regular seeding of immature bay scallops has resulted in thriving commercial fisheries, Rhode Island has a tiny commercial fishery for bay scallops — fewer than three fishermen participate — and the fishery is not sustainable.

Anna Gerber-Williams, principal marine biologist for the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s Division of Marine Fisheries, just completed the first year of a three-year effort to assess the state’s bay scallop population. She is focused primarily on the salt ponds in South County, especially Point Judith Pond and Ninigret Pond, which historically had healthy bay scallop populations.

“We manage and regulate the bay scallop harvest, but besides Block Island, we haven’t had an actual assessment of what the population looks like in Rhode Island,” Gerber-Williams said. “We know it’s pretty low, and we know the actual commercial harvest numbers are very low. But we don’t have anything to base our management on. The hope is that this project can turn into more long-term monitoring, similar to what’s done on Block Island, and maybe lead to restoration efforts.”

Based on her first year of surveys, Gerber-Williams said there are self-sustaining populations of bay scallops in Point Judith Pond, and their abundance can fluctuate significantly from year to year.

“Scallops are very habitat-dependent,” she said. “The habitat in the salt ponds is very patchy, and those patches are very small.”

Unlike clams, which bury themselves in the sand, bay scallops sit on the seafloor and can swim around by rapidly opening and closing their shell, making them difficult to track and count. Gerber-Williams said they are threatened by several varieties of crabs, which can easily crush the scallops’ shells with their claws.

“Part of the scallop’s strategy is to hide from the crabs in the eelgrass,” she said. “When they’re younger, they attach themselves to eelgrass blades to keep themselves above the bottom and out of reach of predators.”

Dan Torre at Aquidneck Island Oyster Co. experimented this year with growing bay scallops in cages in the Sakonnet River off Portsmouth. He bought scallop seed from area hatcheries last July, and they are approaching marketable size now. He has contracted with one local restaurant to buy his experimental crop, with hopes of scaling up the operation next year.

“I believe there’s a market, but it’s a niche market,” he said. “Normally with sea scallops, you sell just the shelled adductor muscle, but with bay scallops you sell the whole animal. The shelf life isn’t the longest, but it seems like there are a bunch of restaurants that are eager to try them.”

In an effort to figure out how best to restore wild bay scallop populations in the region, the Rhode Island Commercial Fisheries Research Foundation is collaborating with The Nature Conservancy to synthesize what is known about the history of the bay scallop population and fishery in Point Judith Pond.

According to Dave Bethoney, the foundation’s executive director, it will be combined with information about scallop fisheries in Massachusetts and Long Island, N.Y., as a first step to developing a restoration plan.

“How to make them sustainable is the real puzzle,” Bethoney said. “Even successful efforts on Long Island are based on a seeding plan — getting scallops every year from aquaculture facilities to replenish them. They have successful populations, but they’re not self-sustaining. I don’t know how we change that.”

Gerber-Williams agreed.

“In my opinion, the way to boost populations here and keep them at a level that’s sustainable for a good fishery in Rhode Island, we would have to have a seeding program similar to what they have in Long Island and Martha’s Vineyard,” she said. “Every year they put out thousands of baby bay scallops. They seed their salt ponds every single year to keep a decent fishery going.

“So the next step for us would be to do that kind of seeding program in Rhode Island. We’re in the process of creating a restoration plan for various species of shellfish in Rhode Island, and my hope is that bay scallops are a part of that.”

Hopefully the current researchers go back to the North Cape shellfish injury restoration project, which included release of bay scallop seed into the South County salt ponds, to learn about what worked or did not work for the multi-year that wrapped up by 2010. The reports are available and some of us who worked on the project are available to discuss challenges and successes.

Todd McLeish is an ecoRI News contributor.

Eelgrass is prime habitat for bay scallops.

Soon you can do it outside

“Ice Skating Blues” (drawing and encaustic on board), by Providence-based painter Nancy Spears Whitcomb

Wary celebrations

Work by 2019 Best of Show Winner Connor Gewirtz at the Providence Art Club.

Old salts

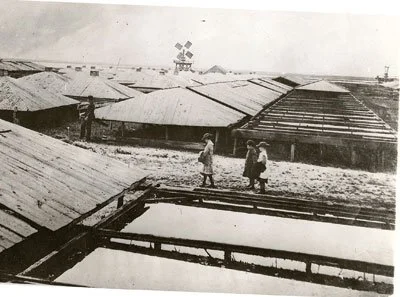

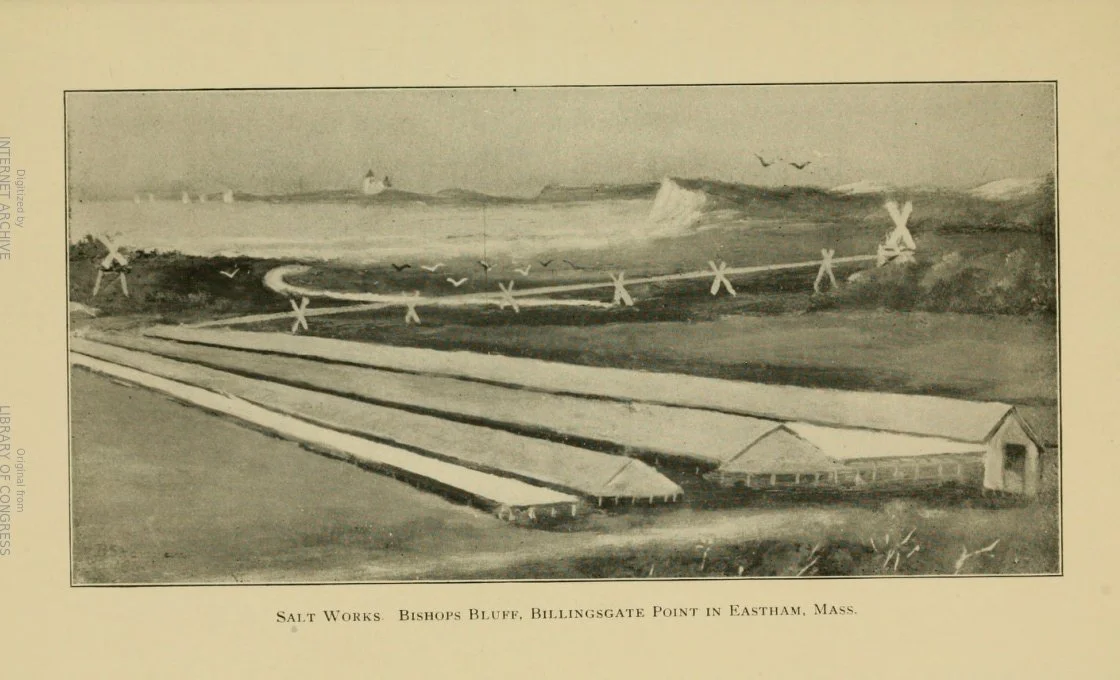

West Yarmouth salt works in the 19th Century.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Some of my ancestors were in the salt business on Cape Cod in the 19th Century; they made it from evaporating ocean water. It seems so long ago that large amounts of such a basic commodity, like ice cut from ponds in Maine, would be produced in low-tech ways in New England, for the local and faraway markets. (Blocks of ice from New England would be packed in sawdust and shipped by boat to the Southeast.)

The smarter relatives moved money that they made from this commerce into more lucrative manufacturing of shoes, tools and so on. A few even straggled into mid-20th Century high tech. Of course, all sectors fade in the end.

Llewellyn King: Taking the stand for the truth, not a political party; beware false equivalence

An angel carrying the banner of "Truth", in Midlothian, Scotland.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I remember the feeling in newsrooms back in the 1960s, as many journalists began to have doubts about the Vietnam War.

In those big workspaces where newspapers come together and broadcasts are assembled, the Vietnam War was taken by journalists to be the good guys versus the bad guys -- the way it had been in the two world wars and the Korean War. But by the mid-1960s, the media were turning against the war.

Some reporters went to Vietnam, the rest of us edited and sometimes melded several files from the war.

Initially, coverage reflected simply what the U.S. commanders were saying in daily briefings from Saigon. As our colleagues on the ground in the war zone began to tell a different story from the official one, editors and writers far from Vietnam began to change their views. Enthusiasm turned to doubt, followed by an anti-war sentiment. The media, in its way, had found its conscience.

Media doubt accelerated as the war dragged on and turned to something close to hostility. I was privy to this because I circulated as a desk editor between three newspapers: the Washington Daily News, the Washington Evening Star, and the Baltimore News-American, finally roosting at The Washington Post.

The American Newspaper Guild passed an anti-war resolution at its annual convention in Dallas in 1969. This side-taking disturbed many journalists. It wasn’t objective, but it passed anyway.

Today, the media landscape is different. There are many more partisan outlets in broadcasting and fewer strong, local newspapers. And there is the whole new world of social media, which defies monitoring. Still the reporting is done by the mainstream media, and from this all-else flows.

While the attitudes of the mainstream are important, they aren’t as commanding as they were in the time of the Vietnam War -- in the time when the nation watched the evening news with total belief and hung on every word from Walter Cronkite.

I have a strong sense of that same struggle between the professional requirement for objectivity and the private conscience is testing the media today just as it did in the days of the Vietnam War.

Can we still cover the divisions of today as an event, as we do most things, or is it morally different?

There is an emerging consensus that journalists collectively -- and a more disaggregated group couldn’t be imagined than the irregular army of nonconforming individualists which make up the Fourth Estate -- are concerned about the survival of democracy. The very basis of our freedoms, of our pride, and even of our history as a free nation capable of the orderly and willing transfer of power is at stake. You can’t work in media now and not feel the sense of the nation going off the rails.

It is, I submit, a turning point when journalists of conscience can’t fall back on the old rules of objectivity, giving one opinion and countering it with another. To give the other side, when you, the writer, know the other side is a contrived lie, is to give credence to the lie and further extend its malicious purpose.

You can’t give the lie the same credence as the truth or you will hide in false equivalence and fail the public.

Even journalists I know who are socially and politically conservative are signing on to the idea that they must take a stand for the truth.

The Big Truth being that Joe Biden won the presidential election, verified over and over again by recounts and court findings. The false equivalence would be to repeat the Big Lie and say at the end of a report, “But supporters of Donald Trump assert the election was rigged.”

When you know that the future of our democracy is in the balance, as a journalist, you feel it is time to take a stand; not to stand with Democrats, but to stand with the truth.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email address is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Linda Gasparello

Co-host and Producer

"White House Chronicle" on PBS

‘Truth as multiple’

Detail of The Khan Hotel wallpaper in Brussels,’’ by Lebanon-based architect, author and artist Raafat Majzoub, in his show “GROUNDS,’’ Jan. 15-Feb. 20 at the Boston Center for the Arts.

The Lebanon-based artist's exhibition is, he says, “an invitation to reconsider truth as multiple. To change. To engage. And to share. It presents grounds for the validity of our collective fictions and creates new grounds for shared realities to come."

Art from science

Haleh Fotowat, “Multicellularity II: (oil and charcoal on unprimed canvas), by Heleh Fotowat, in her show “Multicellularity,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, Jan. 29-Feb. 27.

Art from science! She is also a staff scientist at Harvard’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, in Cambridge.

She tells the gallery:

"Inspiration for this body of work comes from unpredictability, urgency, continuity, beauty, humor, and enthusiasm that is omnipresent in all forms of life. My painting process consists of spontaneous, uninhibited drawing of shapes, trajectories, words, and numbers, usually with a pen or pencil. I often listen to improvised jazz music while I work, letting my hand go free and move as it needs to. I sometimes even dance. Then I add paint, going back and forth between drawing and painting. I watch, listen to, and encourage conversations between individual elements that surface as I go along, as they form a coherent 'multicellular life form.’’’

Hannah Leighton: The growing farm-to-campus movement in New England

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

“Farm to campus” is a growing movement to mobilize the influence and power of colleges and universities to shape the food system. Research done before the COVID-19 pandemic shows that New England colleges with dining services served more than 87 million meals and spent nearly $400 million on food and beverage annually. Decisions about what food to buy, where to buy it and from whom help shape supply chains, affect the health and nutrition of those eating at the institutions, and can support the communities of which the institutions are an integral part. In addition, colleges and universities are educating and shaping opportunities for future food systems leaders, food businesses and food consumers.

Farm to Institution New England (FINE) works with the higher-education sector to better understand and help shape the role higher ed plays in our food system. The pandemic has hugely impacted college dining and food systems work. Campuses face supply-chain disruptions, staff shortages, closed dining halls and new levels of food insecurity in their communities. But as they have grappled with these disruptions over the past two years, they have also leaned on the years of partnership and collaboration with local food partners to get through this trying time. For FINE and our partners, we know that in order to continue building this foundation, we must ground our work in evidence and understanding of the changes.

As FINE and our campus partners geared up to assess the current state of farm-to-campus activity in the six New England states, we developed an innovative approach to data collection and sharing. This month we are launching the New England Farm and Sea to Campus Data Center, a new system for collecting, measuring and reporting farm-to-campus work.

The Data Center will be the one-stop shop for New England colleges to aggregate information about farm-to-campus efforts, generate reports, measure progress over time, network with other campuses, and more.

The Data Center will build on and streamline the data-collection process and decentralize data ownership across multiple stakeholders.

Multiple campus stakeholders will be able to enter data specific to their area of the food system. This includes:

Dining directors, managers and chefs

Campus farm managers

Food access/security leaders on campus (e.g., food pantry, student union, student-led food justice organizations).

Campuses will find questions about their general dining services, regional and sustainable food procurement, campus farms, food security efforts, tracking and traceability, community engagement and more. They will be able to share their results with administrators and other stakeholders while also benchmarking themselves in the region and finding new partners.

New England colleges with dining services can expect to receive an email in January with further instructions on how to log in and get started. In the meantime …

Get data points ready. FINE will start collecting them this month.

Get tracking support as you’re collecting your data. The beta version of FINE’s new purchase tracker is available free to anyone looking for support with their regional and values-based procurement tracking. It even comes with a handy calculator. More functionality coming soon (Google or Excel).

View a demo and find other resources on FINE’s website.

Over the coming year, the Data Center will also be where FINE hosts analyses and summary data, interactive dashboards and other opportunities for policymakers, funders, researchers and farm-to-institution stakeholders to better understand the landscape we’re trying to positively impact. While this beta version is being launched in the campus sector, other institutions will eventually be able to use this space to network, find supply chain partners and see how their activities compare with others in the region.

FINE has collected data from New England colleges with dining services via survey since 2015. These surveys have resulted in two reports: “Campus Dining 101: Benchmark Study of Farm to College in New England” and “Campus Dining 201: Trends, Challenges, and Opportunities for Farm to College in New England.” Findings from these efforts have informed regional funders, policy makers, researchers and others who support farm-to-institution projects across New England.

Hannah Leighton is director of research and evaluation at Farm to Institution New England.

Deeply rooted in the Hood

“Deeply Rooted in the NeighborHOOD, homage to Allan Rohan Crite” by Black muralists Johnetta Tinker and Susan Thompson, at 345 Blue Hill Ave., Boston, through Feb. 10

This is the third and final installation of “Mentoring Murals,’’ sponsored by Greater Grove Hall Main Streets, which "seeks to showcase the work of local artists {and} amplify the importance of maintaining a vibrant Black arts community".

And you can wear a beret

The University of Massachusetts’s burgeoning flagship campus, in the Connecticut River Valley in Amherst, looking southeast.

— Photo by Viking1943

{Amherst is} the last place in America where you can find people who think politically correct is a compliment…probably the only place in the United States where men can wear berets and not get beaten up.’’

Madeleine Blais (born 1946), journalist and professor at UMass Amherst, in In These Girls Hope is a Muscle (1995).

Amherst is best known now for UMass and Amherst and Hampshire colleges. The Connecticut Valley is thick with colleges, from Connecticut up to Dartmouth College, in Hanover, N.H.

Fayerweather Hall at Amherst College.

— Photo by Kenneth C. Zirkel