Philip K. Howard: How to fight back against the forces that are tearing apart America: End the ‘vetocracy’

Trump supporters crowding the steps of the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021 as they prepare to force their way into it to try to overturn the election won by Joe Biden.

— Photo by TapTheForwardAssist

NEW YORK

What can we do about our country? That’s the question I hear most often. Washington is mired in a kind of trench warfare, with no prospects of forward movement. And Americans today can be divided into two camps: discouraged or angry.

Americans are retreating into warring identity groups as extremists demand absolutist solutions to defeat the other side. It’s nighttime in America.

Yet, Americans still share basic values of self-reliance, tolerance and practicality, surveys show. Put Americans in a crisis, and unfailingly they put themselves on the line to help their fellow citizens, as essential workers did during the COVID-19 lockdowns.

Do we really hate each other? I don’t think so. We’re being forced apart by organized forces that profit from polarizing the country.

Extremists have the stage, and are relishing their new power to cow reasonable people into unreasonable positions — whether to deny the results of elections or benefits of vaccines, or to demand that most Americans wear hair shirts because of the sins of their ancestors.

Political insiders are manipulating extremism to their own goals. Political parties no longer compete by accomplishment but by stoking fears that the other side is worse.

The bottom line: Washington will not pull America back from the extremist precipice.

New leaders are obviously needed. But new leaders are not sufficient. Remember that Barack Obama promised “change we can believe in.” When that didn’t work out, frustrated voters (albeit with almost 3 million fewer votes than Hilary Clinton got) elected his polar opposite, Donald Trump, who promised to “drain the swamp.” Nothing much changed except more frustration, leading to greater extremism.

A new governing vision is needed – one that appeals to common interests while also responding to our frustrations. To talk polarized Americans off the precipice, we must understand how we got to the edge of this cliff.

The root cause of extremism, throughout history, is often a sense of powerlessness. Humans have an innate need for self-determination and opportunity. Can you do and say what you think makes sense? If not, sooner or later, you will want to break out. The Tea Party, Occupy Wall Street, Black Lives Matter, Stop the Steal: All these recent movements are ignited by a sense of powerlessness.

Government controls decision-making

What Obama and Trump failed to comprehend is this: The operating philosophy of modern government does not honor the role of human judgment in social activities. Instead of providing an open framework of goals and principles, activated by people taking responsibility, government strives to supplant human agency altogether.

At every level of society, Americans have been disempowered from making the choices needed to move forward. The operating structures of modern society are versions of central planning – dictating exactly how to do everything.

Why do Americans feel powerless? Because they can’t make a difference, and neither can their elected officials.

A new governing vision is needed to address this powerlessness. What I propose is to restore the human responsibility model that the Framers envisioned. As James Madison put it, giving responsibility to “citizens, whose wisdom may best discern the true interest of their country.”

Law should set goals and boundaries, but leave implementation to responsible people. Our protection from bad choices is accountability, not mindless compliance. "No man is a warmer advocate for proper restraints," George Washington wrote, but you cannot remove “the power of men to render essential services, because a possibility remains of their doing ill.”

Building an open governing framework activated by human responsibility is not difficult – it’s far easier to articulate goals than to dictate the details of implementation. Look at any organization or agency that works tolerably well, and you will find people focusing on the goals, not legalities.

But this new governing vision represents a radical departure from the status quo. No longer can bureaucrats avoid responsibility by being sticklers for rules. No longer can one lousy teacher or loud parent get what they want by demanding their rights. People in charge will actually be in charge, and will be empowered to act on their judgment. Other people will be empowered to make the judgments to hold them accountable.

America has become a 'vetocracy'

The federal government will never return willingly to a governing philosophy built on the foundation of human responsibility. All the detailed rules and red tape may prevent forward progress, but they empower insiders to block anything they don’t like. The power in Washington is the power of veto – a governing structure that political scientist Francis Fukuyama calls a “vetocracy.”

Change must come from the outside. The vision for change is to replace red tape with human responsibility. Let Americans use their judgment again. Instead of compliance, give people freedom to hold others accountable.

This is how a free society and democratic government is supposed to work. Instead of driving Americans into warring camps by trying to force one conception of the good, this vision can unite Americans by empowering them to shape their own conception of the good within broad legal boundaries.

Allow Americans to make things work again, and the darkness will soon turn into morning.

Philip K. Howard, a lawyer, author, New York civic and cultural leader and photographer, is founder and chairman of Common Good, a legal- and regulatory-reform nonprofit organization. His latest book is Try Common Sense: Replacing the Failed Ideologies of Right and Left. Mr. Howard is a friend and former colleague of New England Diary’s editor, Robert Whitcomb, who has worked on several Common Good projects in the past.

David Warsh: Nobel economics prize committee needs to look at the lessons of the 2008 crisis

Lehman Brothers headquarters in New York before the firm’s bankruptcy in September 2008 sent the world into the worst financial panic since the Great Depression.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It was a substantial responsibility the government of Sweden licensed when, in the 1960s, it gave its blessing to the creation of a prize in economic sciences in memory of Alfred Nobel, to be administered by Nobel Foundation and awarded by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. That bold action wasn’t easy, but it was as easy as it would get.

The Cold War smoldered ominously between two very different systems, “capitalist” and “communist.” In the West, the prestige of the Keynesian revolution was at its height, compared by some historians of science to the Darwinian, Einsteinian, Freudian and quantum revolutions. And the Science Academy possessed seventy-five years of experience as administrators of the physics and chemistry awards that were among the five prizes mandated by Nobel’s handwritten will.

Since 1969, when the first economics prize was awarded, the committee that oversees it has done pretty well, at least in the judgment of those who have followed the program closely. The Nobel system has imposed a narrative order on various developments since the 1940s in an otherwise fractious profession, often by recognizing its close neighbors. Goodness knows where we in the audience would be without it – still reading Robert Heilbroner’s The Worldly Philosophers, perhaps, first published in 1953, as though nothing since had happened.

Now, however, the Nobel Prize in economic sciences is facing a crucial test. The authorities need to give a prize to clarify understanding inside and outside the profession of the events of 2008, when emergency lending and institutional restructuring by the world’s central banks halted a severe financial panic. What might have turned into a second Great Depression was thus averted. Governments’ responsibilities as lenders of last resort were the heart of the issue over which Keynesians and Monetarists jousted for seventy-five years after 1932.

Either the Swedes have something to say about what happened in 2008, not necessarily this year, but soon, or else they don’t. Their discussions are well underway. The credibility of the prize is at stake.

The Nobel committees that administered the prizes in physics and chemistry faced similar problems in their early years. When the first prizes were awarded, in 1901, well-established discoveries dating from the 1890s made the decisions relatively noncontroversial – the discovery of x-rays, radioactivity, the presence of inert gases in the atmosphere, and the electron. Foreign scientists were invited to make nominations; Swedish experts on the small committees, several of them quite cosmopolitan, made the decisions. The members of the much larger academy customarily accepted their recommendations.

But a pair of scientific revolutions, in quantum mechanics and relativity theory, soon generated “problem candidacies” that took several years to resolve. Max Planck, first seriously considered in 1908 for his discovery of energy quanta, was final recognized in 1918. Albert Einstein, first nominated in 1910 for his special relativity theory, was recognized only in 1921, and then for his less important work on the photo-voltaic effect.

It is thanks to Elisabeth Crawford, the Swedish historian of science who first won permission to study the Nobel archive, that we know something about behind-the-scenes campaigns among rival scientists that underlay these decisions. Overlooked altogether may have been the significance of the work of Ludwig Boltzmann, who committed suicide in 1906.

The economics committee has what it needs to make a decision about 2008. The Swedish banking system suffered a similar crisis in the early Nineties and dealt with it in a similar way. Fifteen years later, Swedish economists paid close attention to what was happening in New York and Washington,

In 2017, in cooperation with the Swedish House of Finance, the committee organized a symposium on money and banking, at which the leading interpreters of the 2008 crisis contributed discussions. (You can see here for yourself some of the sessions from that two-and-half day affair, but good luck making sense of the program. That’s what the committee exists to do – after the fact.)

A previous symposium, in 1999, considered economics of transition from planned economies, and wisely steered off. No such inquiry was required to arrive the sequence of prizes that interpreted the disinflation that followed the Volcker stabilization – Robert Lucas (1995), Finn Kydland and Edward Prescott (2004), Thomas Sargent and Christopher Sims (2012) – a process that unfolded more slowly and less certainly than the intervention of 2008.

The money and banking prize should be understood as fundamentally a prize for theory. For all the talk in the last few years about the rise of applied economics, the Nobel narrative, at least as I understand it, has emphasized mainly surprises of various sorts that have emerged from fresh applications of theory, in keeping with Einstein’s dictum that it is the theory that determines what we can observe.

Some of these applications may have reached dead ends, leading to new twists and turns. The advent of cheap, powerful computer and designer software in the Nineties handed economists a power new tool, and two recent prizes have reflected the uses to which the tools have been put – devising randomized controlled tests of economic policies, and drawing conclusion from carefully-studied “natural experiments.” But otherwise “the age of the applied economist” may be mainly a marketing campaign for a generation of young economists eager to advance their careers. It won’t be an age in economic science until the Nobel timeline says it is.

As a journalist, I’ve covered the field for forty years. My impression is that many exciting developments have occurred in that time that have not yet been recognized, some of them quite surprising, many of them reassuring. As the Nobel view of the evolution of the field is revealed in successive Octobers, the effect may be to buttress confidence in the field and diminish skepticism about its roots – or not. As for natural experiments, it is hard to beat the events of 2008. The Swedes have many nominations. What they must do now is decide.

David Warsh, an economic historian and a veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first appeared.

Chris Powell: Amid most infections ever, time to reappraise pandemic policies

Graphic of COVID-19 infection by Colin D. Funk, Craig Laferrière, and Ali Ardakani.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut doesn't audit the performance of any of its major and expensive state government policies -- not education, not welfare, not urban -- but now would be a pretty good time for state government to audit its response to the virus epidemic.

For the epidemic has consumed nearly two years of state government's focus, impairing everything important -- commerce, schools, mental health, social order and basic liberty and democracy themselves -- only for all official efforts to fail to stop the spread of the virus. New daily confirmed cases in Connecticut in the last week averaged almost 4,000, the most yet, and weekly "virus-associated" deaths are double what they were only a few weeks ago.

An increase in infections might have been expected as colder weather pushed people closer together indoors and because of the holidays. But then a decline in infections also might have been expected because of the state population's high degree of vaccination and face-masking -- that is, might have been expected if vaccines and face-masking really work as promoted.

But even government and government-friendly medical officials admit that the vaccines are quickly losing effect. Needing frequent "boosters," they aren't half as good as traditional vaccines, and there is growing concern that too many "boosters" may damage the human immune system.

This doesn't mean that the vaccines and masks haven't helped or that the epidemic might not be worse without them. It means that another approach to the epidemic is necessary -- greater emphasis on therapies, of which there are many, and not only the antiviral pills just developed by pharmaceutical giants Pfizer and Merck, which, like the vaccines themselves, are not yet adequately tested and thus full of risk.

Even government-friendly medical authorities acknowledge the correlation between virus infection and deficiency in Vitamin D, the "sunshine vitamin," especially in people with dark complexions, and many authorities recommend strengthening the immune system with Vitamin D and C and zinc supplements. Natural and manmade antivirals and anticoagulants abound and many studies have found them effective against the virus, especially if administered soon after infection.

Unfortunately at the outset of the epidemic, when medicine did not understand the virus, patients were commonly told only to go home and take cold medicine and return to a doctor or hospital if their symptoms worsened. But when their symptoms worsened, it was often too late to save them.

Now treatment is more sophisticated. On any particular day infections in Connecticut may increase by thousands but hospitalizations and deaths by only a few. On some days infections soar but hospitalizations decline. Many infected people have no symptoms and nearly all people survive infection.

Even government-friendly medical authorities also acknowledge the correlation between virus fatalities and "co-morbidities" like obesity and diabetes, which most people could control.

Gov. Ned Lamont announced last week that state government soon will distribute, without charge, millions of masks and virus tests that can be taken at home. While the tests may be helpful, there is no shortage of masks and the virus penetrates them easily. It might be far better for state government to help people understand that their immune systems and general fitness may be defenses as good as if not better than masks and vaccines, and if state government distributed free immunity-boosting vitamins and supplements and even gym memberships.

State and local government officials and the medical authorities on whom they rely have done their best in circumstances that have no precedent in living memory. But their good intentions don't vindicate mistakes.

Despite lockdowns, mandatory masks, vaccines, "boosters," and damage to society that will not be repaired for many years, Connecticut and the country are facing more virus infections than ever. So government should start questioning its policies and assumptions about the epidemic, including the assumption that the epidemic is so deadly that combating it must take priority over all other objectives in life.

What isn't working needs to change, if only to set an example for the other things in state government that, after long experience, don't work except to sustain the government itself.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

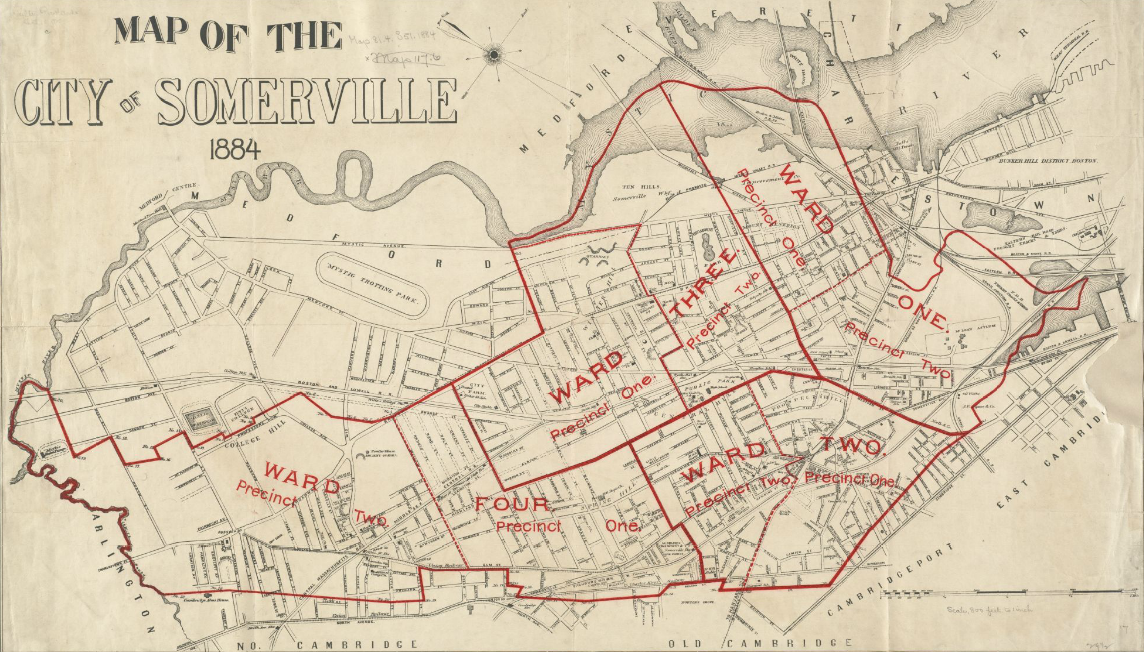

Can we save ourselves?

— Photo by Googleaseerch

When the wind works against us in the dark,

And pelts the snow

The lower chamber window on the east,

And whispers with a sort of stifled bark,

The beast,

‘Come out! Come out!’—

It costs no inward struggle not to go,

Ah, no!

I count our strength,

Two and a child,

Those of us not asleep subdued to mark

How the cold creeps as the fire dies at length,—

How drifts are piled,

Dooryard and road ungraded,

Till even the comforting barn grows far away

And my heart owns a doubt

Whether 'tis in us to arise with day

And save ourselves unaided.

‘‘Storm Fear,’’ by Robert Frost (1874-1963)

‘Only what my consciousness allows’

“The Uncertainty Principle” (graphite and acrylic on canvas), by Newton, Mass.-based Frank Capezzera, in his show “The Self as Universe: Figurative Musings in Cosmology (or the All-Compassing Universe)” Jan. 22-Feb. 27, at Galatea Fine Art, Boston.

He tells the gallery:

"...This series of paintings was developed through my amateur enthusiast’s reading of current cosmological subjects … including Newtonian and Einsteinian physics, quantum mechanics, mathematics, and astronomy from the Big Bang to the emergence of modern human consciousness. I contemplate the elementary debris of stars becoming organized into rocks, then one cell organisms and now human consciousness and self-awareness able to pose limitless questions about everything, including ‘is death the end?’

“The range of images in some of the paintings is among the very large (galaxies, nebulae, stars) or the very small (electrons, quarks, and other subatomic characters of what’s called the Standard Model) and human scale, that which we relate to intuitively. The paintings contain remnants of symbology, both mathematical and anthropological ideograms, such as kanji. For example, the Japanese kanji meaning ‘all-encompassing universe’, sometimes referred to in Aikido, either appears in the paintings or was used as an ‘armature’ for the construction of figures.

“The paintings, two dimensional in charcoal and paint, result from personal musings on how the universe might fit together including (1) how the very large (galaxies) and the very small (subatomic quanta) and gravity work together and (2) will there be anything left of me after I die? As I write this I know only what my consciousness allows. Strangely, what might be scary feels like the way for me to go. I feel as if I am crossing into the zone within myself to contemplate unknowable answers to questions in a new and evolving art-making experience."

Happy in Connecticut

Seal of Southbury, Conn

"I came to Southbury because I wanted to live a more simple life. When I was a child, I saw lots of movies about happy people living in Connecticut. And ever since then, that was where I wanted to live. I thought it would be like the movies. And it really is. It's exactly what I hoped it would be.’’

— Polly Berger (1930-2014), actress, singer, writer and TV host

Audubon Center Bent of the River Trail in Southbury.

—Photo by Karl Thomas Moore

More and smaller

Need more like this.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

There’s a bad “affordable housing” problem in Rhode Island, as in many other states, most famously in California. But the state does have some assets, for example, hotels that are closing because of what appears to be a permanent drop in business travel. Most of these could be converted to temporary and/or permanent housing.

Consider the former Cru Hotel at T.F. Greene International Airport. It’s being converted to a 181-unit building for workforce housing.

Closed schools, though more challenging to retrofit, also offer space for housing.

Meanwhile, zoning laws need to be revised to allow more and denser housing to be constructed, boosting supply and thus reducing cost pressures. This should include letting people put up “little houses” in backyards for family members in places where zoning now forbids it. And loosening some local rules mandating a large number of parking spaces as a requirement with housing construction would help, too.

Rhode Island remains the second-most-densely populated state, after New Jersey, another reminder of its housing challenges.

An ‘ordeal’ only to some

“Surely the framers of the Declaration of Independence did not have Vermonters in mind when they declared ‘all men are created equal,’ and the ordeal of winter in northern New England violates the national credo of equal justice for all.’’

Charles T. Morrissey, in Vermont: A History

‘Think of an egg’

Baby New Year 1905 chases old 1904 into the history books in this cartoon by John T. McCutcheon.

“This is the beginning.

Almost anything can happen.

This is where you find

the creation of light, a fish wriggling onto land,

the first word of Paradise Lost on an empty page.

Think of an egg, the letter A….’’

— Billy Collins (born 1941). This Holy Cross graduate was twice the U.S. poet laureate.

Our feathered friends await orders for 2022

Getting our Canada geese in a row for 2022 on the South Branch of the Pawtuxet River at Riverpoint, in West Warwick, R.I.

— Photo by Linda Gasparello of White House Chronicle

The Canada Geese on this branch of the river are like the swallows of San Juan Capistrano. They return in the winter. Their summer gorging ground is the north branch.

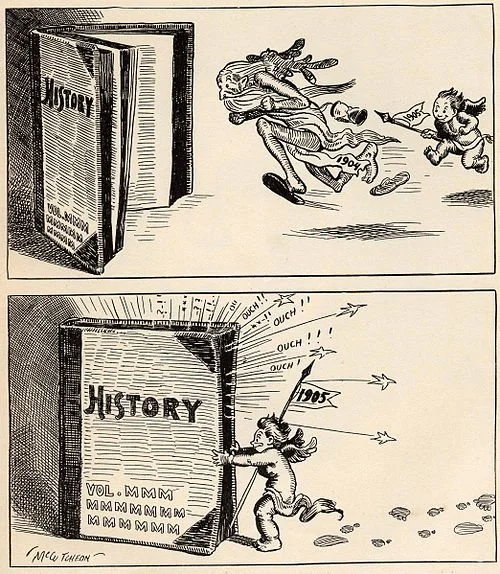

Ruthless political amphibian

Printed in March 1812, this political cartoon was made in reaction to the newly drawn state senate election district of South Essex created by the Massachusetts legislature to favor the Democratic-Republican Party. The caricature satirizes the bizarre shape of the district as a dragon-like "monster," and Federalist newspaper editors and others at the time likened it to a salamander.

The term gerrymander is named after Elbridge Gerry, the Massachusetts governor (and later U.S. vice president) who in 1811 signed a bill creating the district above. Gerrymandering is almost always considered a corruption of the democratic process.

— Jeffrey Toobin (born 1960), American lawyer and journalist, including as a CNN legal analyst.

Flowing into COVID’s third year

“Golden Rapids (Maine)” (limited-edition photo-print on anodized aluminum), by Kathleen McCarthy, at Alpers Fine Art, Andover, Mass.

Llewellyn King: Climate crisis, population growth and a solution; N.E.'s densest community

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

It wasn’t front and center at the recent climate-change summit, COP26, in Glasgow, but it was whispered about informally, in the corridors and over meals.

For politicians, it is flammable, for some religions, it is heresy. Yet it begs a hearing: the growth of global population.

While the world struggles to decarbonize, saving it from catastrophic sea-level rise and the other disasters associated with climate change, there is no recognition officially anywhere that population plays a critical part.

People do things that cause climate change from burning coal to raising beef cattle. A lot of people equal a lot of pollution equals a big climate impact, obvious and incontrovertible.

In 1950, the global population was at just over 2.5 billion. This year, it is calculated at 7.9 billion. Roughly by mid-century, it is expected to increase by another 2 billion.

There is a ticking bomb, and it is us.

There was one big, failed attempt to restrict population growth: China’s one-child policy. Besides being draconian, it didn’t work well and has been abandoned.

China is awash with young men seeking nonexistent brides. While the program was in force from 1980 to 2015, girls were aborted and boys were saved. The result: a massive gender imbalance. One doubts that any country will ever, however authoritarian its rule, try that again.

There is a long history to population alarm, going back to the 18th century and Thomas Malthus, an English demographer and economist who gave birth to what is known as Malthusian theory. This states that food production won’t be able to keep up with the growth in human population, resulting in famine and war; and the only way forward is to restrict population growth.

Malthus’s theory was very wrong in the 18th Century. But it had unfortunate effects, which included a tolerance of famine in populations of European empire countries, such as India. It also played a role in the Irish Great Famine of 1845-53, when some in England thought that this famine, caused by a potato blight, was the fulfillment of Malthusian theory, and inhibited efforts to help the starving Irish. Shame on England.

The Boston Irish Famine Memorial is on a plaza between Washington Street and School Street. The park contains two groups of statues to contrast an Irish family suffering during the Great Famine of 1845–1852 with a prosperous family that had emigrated to America. Southern New England was a focal point for Irish immigrants to America, and Irish-Americans still comprise the largest ethnic group in much of the region.

The idea of population outgrowing resources was reawakened in 1972 with a controversial report titled “Limits to Growth” from the Club of Rome, a global think tank.

This report led into battles over the supply of oil when the energy crisis broke the next year. The anti-growth, population-limiting side found itself in a bitter fight with the technologists who believed that technology would save the day. It did. More energy came to market, new oil resources were discovered worldwide, including in the previously mostly unexplored Southern Hemisphere.

Since that limits-to-growth debate, the world population has increased inexorably. Now, if growth is the problem, the problem needs to be examined more urgently. I think that 2022 is the year that examination will begin.

Clearly, no country will wish to go down the failed Chinese one-child policy, and anyway, only authoritarian governments could contemplate it. Free people in democratic countries don’t handle dictates well: Take, for example, the difficulty of enforcing mask-wearing in the time of the Covid pandemic in the United States, Germany, Britain, France and elsewhere.

If we are going to talk of a leveling off world population we have to look elsewhere, away from dictates to other subtler pressures.

There is a solution, and the challenge to the world is whether we can get there fast enough.

That solution is prosperity. When people move into the middle class, they tend to have fewer children. So much so that the non-new-immigrant populations are in decline in the United States, Japan and in much of Europe -- including in nominally Roman Catholic France and Italy. The data are skewed by immigration in all those countries -- except Japan, where it is particularly stark. It shows that population stability can happen without dictatorial social engineering.

In the United States, the not-so-secret weapon may be no more than the excessive cost of college.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Web site: whchronicle.com

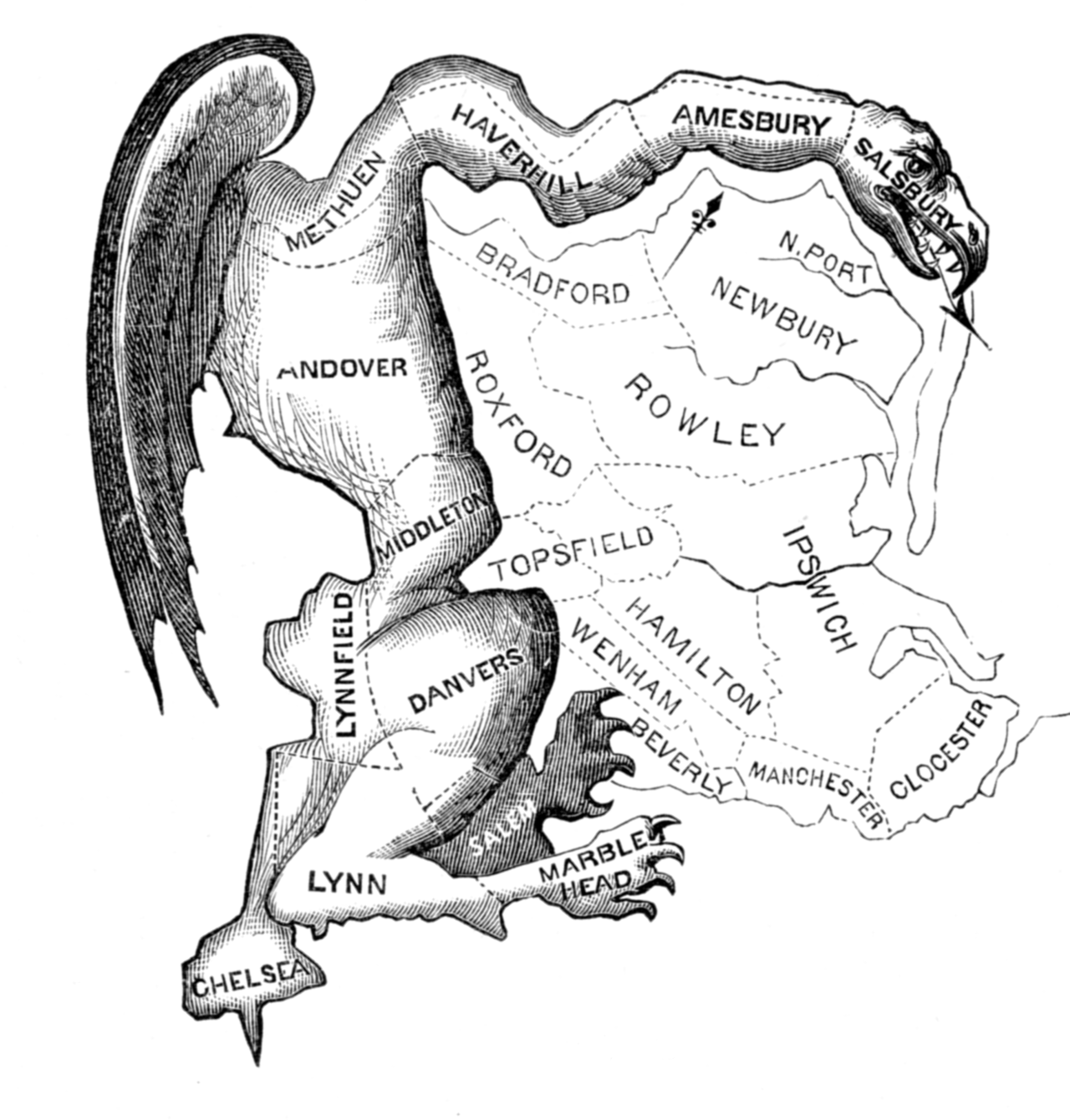

Occupying slightly over 4 square miles, with a population of 81,360 (as of the 2019 Census) (including a myriad of immigrants from all over the world), Somerville is the most densely populated community in New England and one of the most ethnically diverse cities in the nation.

Happiness front-loaded

Lake Champlain from the Burlington wharves, with New York's Adirondack Mountains in the background

“Where I live, in Vermont, there’s this thing that women know about men, which is this disease: their childhood was so idyllic that nothing in the rest of their life can ever be satisfying. It’s almost a plague.”

– Colin Trevorrow (born 1976) film director who lived in Burlington, Vt., for nine years before moving to London.

“I’m going to a commune in Vermont and will deal with no unit of time shorter than a season.”

– Tracy Kidder (born 1945), author of literary nonfiction books. He was just kidding. He has long lived in the western Massachusetts town of Williamsburg.

Cut the superiority talk

Eliza Ann Gardner

“...{I}f you commence to talk about the superiority of men, if you persist in telling us that after the fall of man we were put under your feet and that we are intended to be subject to your will, we cannot help you in New England one bit.’’

— Eliza Ann Gardner (1831-1922) a Boston African-American abolitionist, religious leader and women's movement leader in 1884. She founded the missionary society of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (AMEZ), was a strong advocate for women's equality within the church, and was a founder of the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs.

Stoned on Cape Ann

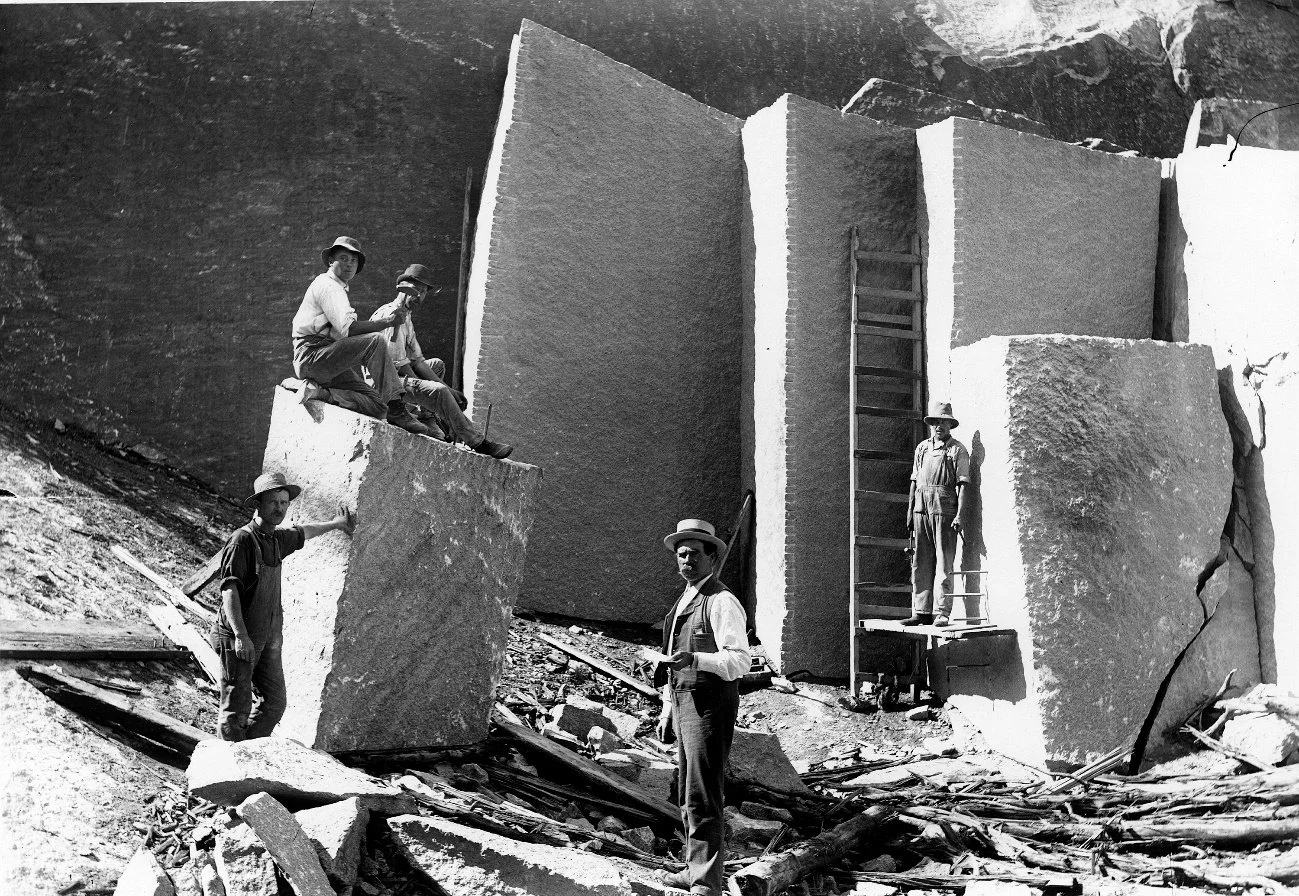

“Cheves Quarry, Lanesville, MA.’’ Barbara Erkkila Collection of the Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives, Gloucester, MA. Gift of Barbara Erkkila, 1994.

The Lanesville section of Gloucester had a thriving granite quarry business in the 19th Century. But it was dangerous work.

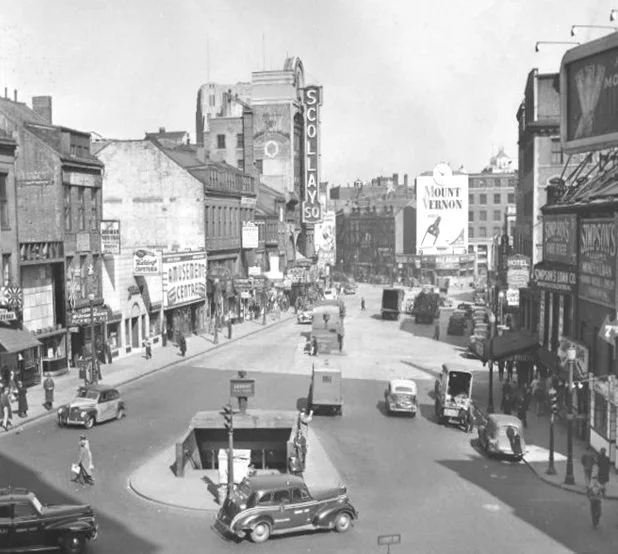

Seedy Scollay was demolished to make way for the sterile

Boston’s vibrant, if seedy, Scollay Square in the ‘30s, before it was demolished in the ‘60s to make way for the sterile Government Center (below), with its brutalist Boston City Hall. Scollay Square’s psychic heart was a burlesque house/quasi strip joint called The Old Howard.

Chilly New Englanders

Brother Jonathan, a 19th Century personification of New England, in striped pants, somber overcoat and Lincolnesque stove-pipe hat, as drawn by Thomas Nast. He is presented as wary and tight-fisted.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

“I never said, 'I want to be alone.' I only said 'I want to be let alone!' There is all the difference.’’

-- Greta Garbo (1905-1990), movie star, on her most famous quote, from Grand Hotel (1932)

An article in Commonwealth Magazine reports that new Boston Mayor Michelle Wu is disappointed that virtually no one on her MBTA Orange Line rides talks to her, even just to say hello.

She says:

“But we’ve got to change the culture of riding the T. It is a civic space for community conversations, but everyone’s always really quiet on there. Maybe I’m still a Midwesterner at heart.’’ The mayor was brought up near Chicago

To read the Commonwealth piece, please hit this link.

New Englanders tend to be reserved and guarded with strangers, unlike, say, in the South and West, where people tend to be very friendly to all, if often just superficially, like someone trying to sell you a car.

The unofficial New England flag, with its lonely pine.

It sort of reminds me of how in disasters, such as in tornado-ravaged Kentucky and other poverty-stricken “conservative’’ states, much is made of the good works of friendly churches and others in the private sector as opposed to aid from government (though Kentucky, a very poor state, is grabbing all the federal help it can now).

I’d rather have the much more impressive services provided by government in “socialist’’ New England than depend, say, on local churches (which are themselves subsidized by taxpayers because they’re tax-exempt – even the many ones that operate like political-party adjuncts).

Hit this link about Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul, a Republican, who voted for the huge Trump tax cuts while saying he’s terrified of the national debt but now wants as much federal aid as possible for his state. (Who wouldn’t?):

Paul has often opposed big federal disaster-relief programs that help states that don’t include Kentucky, including bills passed following hurricanes Sandy, Harvey and Maria.

Chris Powell: Mask police do their thing as killers stay free; Spiffed up Union Station?

A Tyrannosaurus Rex sculpture outside Boston’s Museum of Science wearing a face mask and a Band-Aid indicating a COVID-19 vaccine has been administered.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Poor New Haven. Its police department has been unable to make arrests in 35 of the 45 murders committed in the city in the last two years, a failure rate of 78 percent,.

Despite $111 million in federal emergency assistance, New Haven's school system is running a deficit again, constantly losing teachers to higher-paying school systems and unable to provide drinking water to students, having shut down the water fountains in school hallways in fear that the fountains contribute to the virus epidemic. While water bottle-filling stations have been ordered, they may not be installed before the next school year begins.

But elsewhere Mayor Justin Elicker's administration is on a tear of efficiency. Last week the city launched a sweep of local businesses to check compliance with the mayor's order that everyone indoors in commercial facilities must wear a face mask.

Face masks are doubtful mechanisms of curtailing the virus, but if everyone is required to wear a mask indoors, at least medical theater can make city government seem to be taking charge, distracting from its other failures. A problem will arise only if people start comparing risks.

For even before the arrival of the latest variant of the virus, Omicron, 99.8 percent of people infected recovered, and while Omicron is believed to be more communicable, in most cases it also appears to be far less severe, no worse than a cold and less deadly than, say, a bullet to the brain and the other causes of the criminal deaths New Haven can't solve.

But all Connecticut, not just New Haven, should be questioning government's priorities in the face of the city's many unsolved murders.

A few days ago Windsor's police department announced that after eight months of investigation, it remains unable to determine who, back in April, hung ropes resembling nooses at the Amazon warehouse under construction in that town. The ropes injured no one, but many people were eager to claim that they had felt threatened.

A Windsor police statement described the extensive efforts taken to solve the supposed crime: "Numerous interviews of Amazon construction site personnel were conducted, including steel workers, electricians, safety and security workers, and administrative personnel, as well as others not directly involved in the construction site. Investigators reviewed personnel records of multiple employees, camera footage, and shift logs." Some people were given polygraph tests.

Assisting the Windsor police were the FBI, state police, and Hartford state's attorney's office.

What if such federal and regional resources had been poured instead into investigating the 35 unsolved murders in New Haven? Might one or two of them have been solved by now?

Maybe not, but at least Connecticut would have been spared eight months of expensive political correctness.

Union Station in New Haven.

The still gorgeous interior of Union Station, a major stop and train-changing center for Amtrak and Metro North.

Last week there was also a hopeful development in New Haven. After years of failure to act on the huge potential of historic Union Station, the busiest and grandest railroad station in Connecticut, city government and the state Transportation Department signed a development agreement.

State government will lease the station and its adjacent property to the city for 35 years, with a possible extension of 20 years, so the city might improve it with much-needed parking, a bus depot, restaurants and retail shops, offices, a beautiful plaza, frequent shuttle bus service to Tweed New Haven Airport, and whatever else might befit this gateway to Connecticut and link it to downtown New Haven a half mile away -- if enough free money ever can be found from the state and federal governments, since the city never will have any of its own to spare.

It's a compelling idea but as the city's police and school disasters suggest, there's little reason to believe that New Haven is capable of executing it any more than Hartford has been capable of managing its own big development projects, which is why state government has put a state agency in charge of them. The same should have been done for the Union Station project in New Haven.

So it will be no surprise if the project takes 35 years just to get started, only to end up with marijuana dispensaries, methadone and abortion clinics, gambling parlors, still more housing for people who can't support themselves -- and still not enough parking.-

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

‘Not for need of meat’

After a New Hampshire deer hunt, circa 1910.

The German- or Dutch-looking Sprague (Conn.) Public Library

“He aren’t one-a-them homasoxuals, th’po’try’s

just a hobby,” Dad rushed to assure th’Maine folk

leaving him out of his heart

in the cold of his fidgety disgrace.

Presume dad was mortified because he wasn’t

discussing my crushing shoulder bones

on a football field, bouncing balls in a track

suit or digging spikes into somebody’s ankle,

all the pursuits for your son if it wasn’t

hunting season when a’course any real boy’d

wanta be out wind blown rosy checked blowin’

birds apart or bringin’ down a deer just

because it was November when you bring deer down,

certainly not for need of meat.’’

— From “Crossing America,’’ by Leo Connellan (1928-2001), who was born in Portland, Maine, and raised in Rockland in that state. (This inspired his poems about fishermen and other coastal topics.)

Considered one of the “Beat” poets, he spent the last part of his life as a resident of the small town of Sprague, Conn. He was the Nutmeg State’s poet laureate from 1996 to his death. He made his living as a salesman. “Crossing America’’ was inspired by his trips across the country, east to west and north to south.