Can't hear the forest for the trees?

“Adventures in Echolocations: Somnambulist,’’ by Serena Perrone, at Cade Tompkins Projects, Providence.

Buckland State Forest entrance, in Buckland, in western Massachusetts

Caitlin Faulds: Trying to keep climate change from turning more toxic at N.E. waste sites

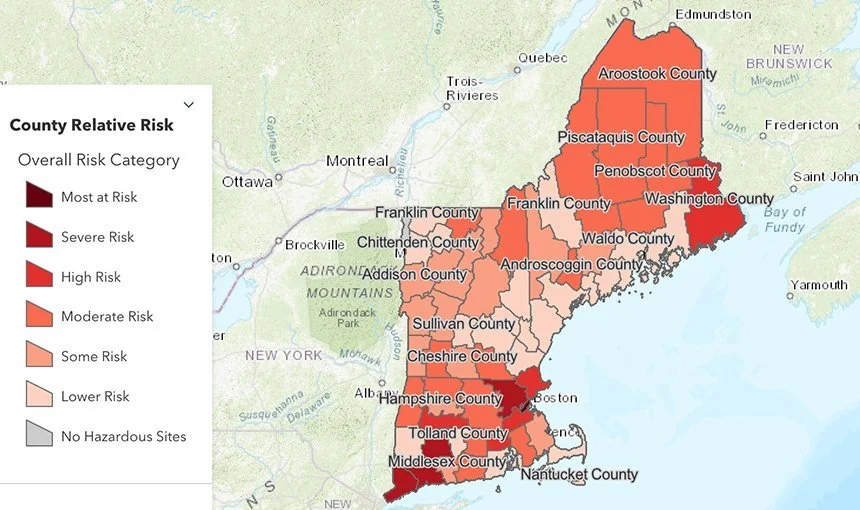

Providence County, in Rhode Island, and Suffolk County, in Massachusetts, are two of the most at-risk counties in New England from pollution buried at toxic sites.

— Conservation Law Foundation map

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Hazardous-waste sites and chemical facilities pockmark New England, leftovers of the region’s industrial past. And little action is being taken to prevent climate change from affecting these sites and cooking up a toxic future, according to analysts at the Conservation Law Foundation (CLF).

A regional report by CLF Massachusetts released this fall combined projections of climate risk with data on social vulnerability and hazardous- waste sites to build a comprehensive map of anticipated toxic-pollution risk from Connecticut to Maine. The results, which show that much of New England could face compounding threats, are startling — even to the mapmakers.

“I bought a house like six months ago … and was actually surprised by the number ... of [Superfund] sites that are in such close proximity to residential neighborhoods,” said Deanna Moran, CLF Massachusetts director of environmental planning. “It’s a little bit scary, but it’s a healthy amount of fear.”

In Rhode Island, Providence County was determined to be the county at highest risk, due to a combination of moderate wildfire risk, severe heat risk, high social vulnerability and 143 hazardous sites. Massachusetts’ s Suffolk County, which includes Boston, was deemed most at-risk in New England.

“A lot of people don’t realize how ubiquitous hazardous sites are, even Superfund sites are, throughout our region,” Moran said. “Even if a site is under remediation or fully remediated, those are the sites that we are still worried about because they were remediated without climate change at the forefront.”

The county-level analysis factors in risk associated with nearly 3,000 hazardous sites. These New England locations include landfills, Superfund sites, brownfields and 1,947 facilities across the region that generate large quantities of hazardous waste or are permitted for the treatment, storage or disposal of toxic chemicals. Many of these hazardous sites are aging, use failing technology, and/or do not have sufficient safeties in place to protect nearby communities in a warmer world, according to the CLF report.

“The techniques that we used to remediate those sites 20 years ago might not anticipate more extreme precipitation or flooding or heat,” Moran said, “and those are the ones that I think are really concerning ’cause they’re really not on the radar.”

Floods could damage infrastructure containing hazardous waste, trigger chemical fires, hinder technology monitoring toxic pollution, and create a toxic stew of floodwater and contaminants, according to the report. Rising temperatures could damage protective caps over contaminated properties and raise the toxicity level of some materials. Wildfires could ravage hazardous-waste sites, damaging protective infrastructure and releasing airborne contaminants.

The lineup of climate risks — which, according to CLF Massachusetts policy analyst Ali Hiple, were “weighted equally” in the report — paints a bleak scene of the region’s future, a future that has been glimpsed in isolated events across the country in recent years.

“Luckily, we have not seen that type of impact in the New England region yet, but we want to make sure that we’re being proactive now and not reactive later,” Moran said.

But despite knowing the dangers that climate poses, federal agencies “are not doing enough to address them, and that puts our communities in danger,” according to the CLF report. In 2019, a U.S. Government Accountability Office report suggested the Environmental Protection Agency should consider climate to ensure long-term Superfund site remediation and protection plans.

“We really just want to see the EPA really leading on this,” said Saranna Soroka, a legal fellow at CLF Massachusetts. “They’ve indicated they know the risk that climate change poses to these sites … but we want to see really consistent, really clear standards applied.”

Soroka noted that the federal agency could analyze climate impact as part of its existing Superfund-site review framework, which mandates site checks every five years. So far, climate analyses have not been incorporated, she said, despite EPA authority to do so.

“I think we’re well beyond the time of thinking through how we should be doing this,” Moran said. “We know the risks are real. In some cases, we’re already seeing them, and the time to be acting on them is now.”

Editor’s note: Here are links to EPA-designated Superfund sites in Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Connecticut.

Caitlin Faulds is an ecoRI News journalist.

Warren Getler: This most uncertain winter

Luce Hall (1884) at the U.S. Naval War College, in Newport, R.I. The institution is a center of the U.S. military’s war-gaming work.

—U.S. Navy photo by Jaima Fogg

Ukrainian troops in the threatened country’s Donbas region. Russia has been massively increasing its troop strength nearby in what some observers fear is a precursor to an all-out invasion.

America faces its most challenging year-end since its formal entry into the Second World War, in December 1941.

While we have been internally grappling with COVID for nearly two years, dark clouds have gathered on the geopolitical map.

Russia is mobilizing some 175,000 troops on its border with Ukraine; China is flying repeated bomber test-runs near Taiwan; Iran is using its proxies to hit its Arab neighbors as well as Israel and U.S. bases in Iraq and Syria with drones and missiles. Russia and China are exhibiting their closest military collaboration – in joint-training exercises and bilateral arms sales – in decades. And both have signed military and economic pacts with Iran in recent years.

Will there be war, indeed, continental war, on several fronts?

The risk may be greater than at any time since World War II.

Authoritarian rulers-for-life in Moscow and in Beijing are testing the waters. Specifically, they are testing the mettle of U.S. President Joe Biden and his first-year administration. They’re gauging a Biden preoccupied with internal debates around vaccination policies, inflation, crime, supply-chain bottlenecks and other largely domestic, massively time-consuming matters.

And they perceive vulnerability in the Oval Office – with Biden, who just turned 79, coming off a grueling multi-year presidential campaign against incumbent Donald Trump and then seeing his approval ratings drop for months. What’s more, they sense a country deeply divided -- an American superpower at growing risk of civil unrest.

Are these Russian and Chinese military maneuvers mere provocations, mere signals of what could happen if the West challenges their geopolitical ambitions?

Or are these up-tempo deployments by Russia’s Putin and China’s Xi meant merely for domestic Russian and Chinese consumption? Possibly not.

This time, the activity around such large-scale mobilizations appears alarmingly furtive, and therefore open to wide interpretation, particularly regarding Moscow’s intentions toward Ukraine. These maneuvers (including rumors of a planned assault on eastern Ukraine in late January or early February) may invite retaliation and potential “miscalculations” by both sides. Putin and Xi may not appreciate the seriousness of possible "kinetic" responses by NATO allies and our friends in Asia. Israel, meanwhile, uncertain of backing from Washington, is leaning toward taking things into its own hands to stop -- with direct military action from the air -- a nuclear-armed Iran from emerging.

America, as the world’s leading democracy, is slow to anger, which is a good thing. Yet we are also at times too slow in confronting harsh realities beyond our borders. As a nation, we must focus on the large-scale threat scenarios developing in Europe, East Asia and the Middle East…with level-headed coolness and a serious, sustained focus.

John F. Kennedy, in his Harvard thesis-turned book, Why England Slept, pointed out the danger of Britain ignoring for too long Nazi Germany’s growing war machine and the bellicosity of its totalitarian dictator, Adolf Hitler.

“We can't escape the fact that democracy in America, like democracy in England, has been asleep at the switch. If we had not been surrounded by oceans three and five thousand miles wide, we ourselves might be caving in at some Munich of the Western World,” writes Kennedy, the then 22-year-old future president of the United States.

“To say that democracy has been awakened by the events of the last few weeks is not enough. Any person will awaken when the house is burning down. What we need is an armed guard that will wake up when the fire first starts, or, better yet, one that will not permit a fire to start at all. We should profit by the lesson of England and make our democracy work. We must make it work right now. Any system of government will work when everything is going well. It's the system that functions in the pinches that survives.”

To prevent tipping into something recalling the 1939-45 cataclysm, we must show resolve – an unquestioned firmness that lets our real and potential adversaries know that we stand united -- at home and with our key allies abroad. Such resolve deters dangerous opportunism among our foes, setting up a bulwark against a lurch into regional war, indeed, into seemingly unthinkable inter-continental war below the nuclear threshold.

We must recognize that both China and Russia have been developing advanced missile systems – notably conventional-use hypersonic weapons – that could put us at risk in the same manner (or more at risk) as the surprise Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. Back then, at least, we could surge into a mass production of armaments as never-before seen; today, given supply-chain restrictions and other factors, such an achievement would perhaps be less certain after any potentially devastating attack on our military bases, ports and other critical infrastructure.

Lest we forget, while Britain slept in those years before the outbreak of WWII, Germany was able to secretly develop its , first-of-their-kind V-2 rockets that would eventually rain down on London and cause widespread damage and terror. Today, Pentagon chiefs are repeatedly sounding the alarm about the yawning gap in U.S. vs. Chinese/Russian advanced hypersonic-missile capabilities, not to mention recently demonstrated Russian capabilities of destroying satellites in orbit with missiles fired from its territory.

To its credit, the Biden administration is slowly but surely turning its strategic military assessments and its inner-circle Pentagon planning toward our China challenge, thus pivoting away from the “forever wars” of Afghanistan, Iraq and, going further back, Vietnam. And, just last week, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken had this to say about the massive Russian troop buildup, including more than 1,000 tanks, on the border of Ukraine. “We don’t know whether President Putin has made the decision to invade. We do know that he’s putting in place the capacity to do so in short order should he so decide.”

As we approach the 80th anniversary of Pearl Harbor this week -- not to mention the 250th anniversary as a nation in less than five years -- America cannot afford to be ill-prepared for tectonic convulsions on the geopolitical landscape. We can not, as a society, spend too much time navel-gazing or being preoccupied with the likes of the latest crazes on Instagram, Tik-Tok or the Metaverse.

These times demand extraordinary leadership, no matter the internal challenges and pre-occupations of the world’s greatest democracy. As Americans, we will be roundly tested during this most uncertain winter -- and not merely by inflationary pressures or a new surge of the Delta and Omicron COVID-19 variants, which are eroding the fabric of civil society both here and abroad.

Warren Getler, based in Washington, D.C., writes on international affairs. He’s a former journalist with Foreign Affairs Magazine, International Herald Tribune, The Wall Street Journal and Bloomberg News. His two sons serve in the U.S. military.

Hands across the sea

Our friend Bill Perna, who grew up in Greenwich, was very surprised to come across this sign while driving into the town of Rose in Italy’s Calabria region.

— Bill Perna

Taiwan scares Beijing

The flag of the Republic of China, Taiwan’s official name.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com.

Good for the Biden administration for inviting Taiwan to the "Summit for Democracy" it has organized for Dec. 9-10, angering, of course, the Chinese dictatorship, which hates having the island democracy as a model that might tempt the dictatorship’s subjects in Mainland China. Bejing claims ownership of Taiwan.

But no, Taiwan has not “always been part of China,’’ contrary to Mainland claims. Hit this link for some history.

The summit is part of Biden’s effort to pull together the world’s democracies and semi-democracies (the latter including the U.S., where democracy is under siege by rising fascism) to push back against increasing aggression by autocracies led by China and Russia after the damage done by dictator-suck-up Donald Trump.

Taiwan, by the way, has many business investments in New England, especially in high technology, and vice versa, as well as many cultural activities. And since 1996, Taipei, the Taiwanese capital, has been a sister city of Boston.

Hit this link for more information.

Only six months to go

Union Square Farmers' Market (watercolor), by Seth Berkowitz, at Brickbottom Artists Association, Somerville, Mass., in the show “Somerville as Muse,” Dec. 9-Jan. 15

Circling makes sense

Rotary sign at a Lowell, Mass., traffic circle. Note the ‘Yield’’ sign.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

like too many other commentators on the $1.1 trillion physical-infrastructure law, have too often failed to note three very important things about, in addition, most famously, to the transportation-related stuff: It would help improve water-supply systems, which are dangerously corroded and outdated in many places and strengthen the electric grid and Internet, including their security, which are all too vulnerable to attacks by the Russians, Chinese, North Koreans and other enemies as well as those extortionists just in it for the money.

We need fewer road intersections with lights and more traffic circles, with landscaping in the middle. The latter have fewer accidents, in part because they slow down drivers where they should be slowed down.\

The Federal Highway Administration reports that traffic circles reduce injury and fatal crashes by 78-82 percent compared to conventional intersections. A typical intersection has 32 conflict points, compared to only 8 at a roundabout.

And, as I discovered last week driving up Route 10 in New Hampshire, they can be quite attractive.

Something for states and localities to consider when it comes to spending federal infrastructure money.

Even in moderation?

“Man’s Greatest Enemy” (c. 1915, oil on canvas), by Charles Allan Winter (1869-1942), at the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass.

Modernist chowder

‘‘Today we take New England clam chowder as something traditional that makes our roots as American cooking very solid, with a lot of foundation. But the first person who decided to mix potatoes and clams and bacon and cream, in his own way 100 to 200 years ago, was a modernist.’’

— Jose Andres (born 1969), Spanish-born American celebrity chef, restaurateur and founder of World Central Kitchen (WCK), a non-profit devoted to providing meals in the wake of natural disasters

Stretching out the pandemic

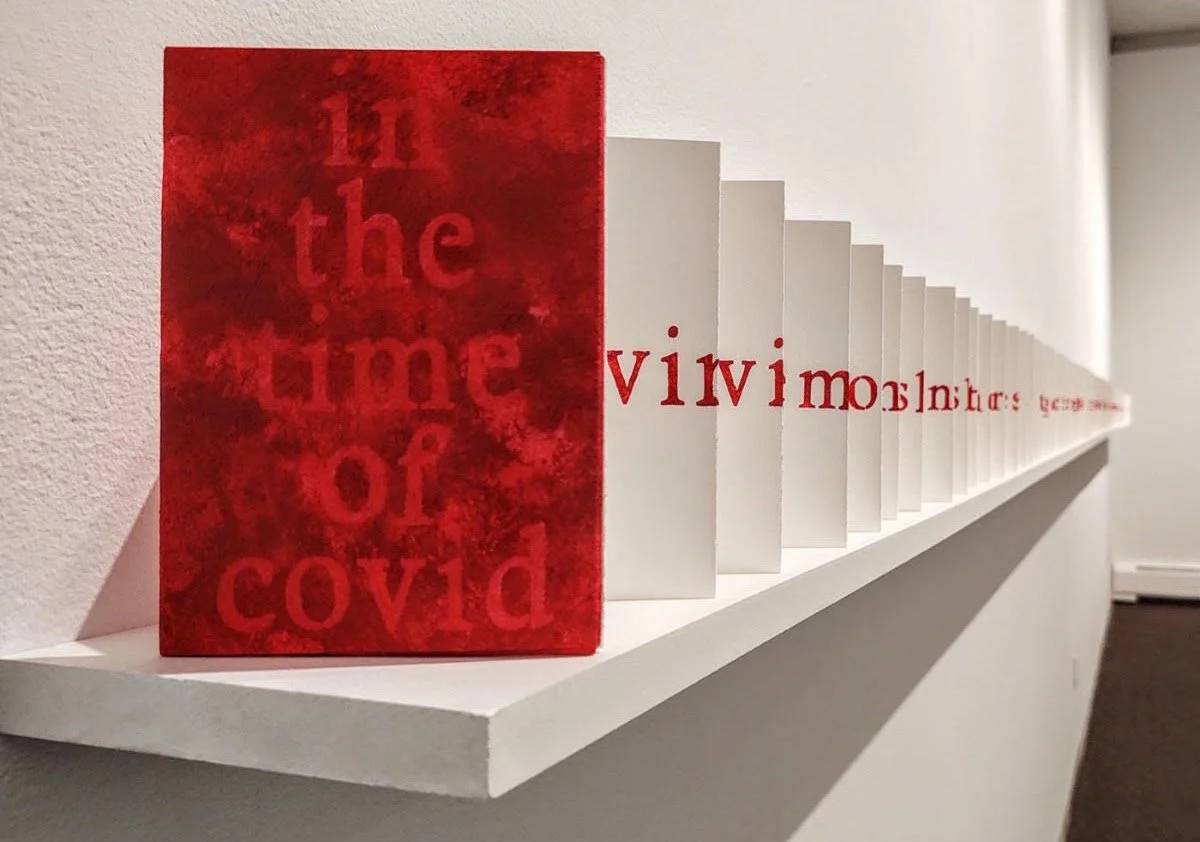

“In the Time of Covid” (acrylic on paper), by Antoinette Winters, at Kingston Gallery, Boston, for December

She tells the gallery:

“Much like everyone else, I was consumed by the news. I read and listened to anything that might inform me. The language, and its daily repetition, took hold. I made lists of phrases and words. I organized and edited them, focusing primarily on the language and events of the first three months of the pandemic. The use of a long accordion book provided both a means of including the extensive text while also emphasizing the length of the pandemic.”

Antoinette Winters is a mixed-media artist who works at her studio at the Waltham Mills Artist Association, in Waltham, Mass.

Waltham Supermarket on Main Street, in Waltham, established in 1936, was a large historic grocery store that closed in the 1990s. The building continues to be a supermarket, occupied subsequently by Shaw's, then Victory, and now Hannaford.

— Photo by jmorgan

Judith Graham: COVID-19 makes smelling the flowers more difficult

“We tend to think of our sense of smell as primarily aesthetic. What’s very clear is that it’s far more important. The olfactory system plays a key role in maintaining our emotional well-being and connecting us with the world.”

— Dr. Sandeep Robert Datta, a professor of neurobiology at Harvard Medical School

The reports from COVID-19 patients are disconcerting. Only a few hours before, they were enjoying a cup of pungent coffee or the fragrance of flowers in a garden. Then, as if a switch had been flipped, those smells disappeared.

Young and old alike are affected — more than 80% to 90% of those diagnosed with the virus, according to some estimates. While most people recover in a few months, 16% take half a year or longer to do so, research has found. According to new estimates, up to 1.6 million Americans have chronic smell problems due to covid.

Seniors are especially vulnerable, experts suggest. “We know that many older adults have a compromised sense of smell to begin with. Add to that the insult of covid, and it made these problems worse,” said Dr. Jayant Pinto, a professor of surgery and specialist in sinus and nasal diseases at the University of Chicago Medical Center.

Recent data highlights the interaction between covid, advanced age and loss of smell. When Italian researchers evaluated 101 patients who’d been hospitalized for mild to moderate covid, 50 showed objective signs of smell impairment six months later. Those 65 or older were nearly twice as likely to be impaired; those 75 or older were more than 2½ times as likely.

Most people aren’t aware of the extent to which smell can be diminished in later life. More than half of 65- to 80-year-olds have some degree of smell loss, or olfactory dysfunction, as it’s known in the scientific literature. That rises to as high as 80% for those even older. People affected often report concerns about safety, less enjoyment eating and an impaired quality of life.

But because the ability to detect, identify and discriminate among odors declines gradually, most older adults — up to 75% of those with some degree of smell loss — don’t realize they’re affected.

A host of factors are believed to contribute to age-related smell loss, including a reduction in the number of olfactory sensory neurons in the nose, which are essential for detecting odors; changes in stem cells that replenish these neurons every few months; atrophy of the processing center for smell in the brain, called the olfactory bulb; and the shrinkage of brain centers closely connected with the olfactory bulb, such as the hippocampus, a region central to learning and memory.

Also, environmental toxic substances such as air pollution play a part, research shows. “Olfactory neurons in your nose are basically little pieces of your brain hanging out in the outside world,” and exposure to them over time damages those neurons and the tissues that support them, explained Pamela Dalton, a principal investigator at the Monell Chemical Senses Center, a smell and taste research institute in Philadelphia.

Still, the complex workings of the olfactory system have not been mapped in detail yet, and much remains unknown, said Dr. Sandeep Robert Datta, a professor of neurobiology at Harvard Medical School.

“We tend to think of our sense of smell as primarily aesthetic,” he said. “What’s very clear is that it’s far more important. The olfactory system plays a key role in maintaining our emotional well-being and connecting us with the world.”

Datta experienced this after having a bone marrow transplant followed by chemotherapy years ago. Unable to smell or taste food, he said, he felt “very disoriented” in his environment.

Common consequences of smell loss include a loss of appetite (without smell, taste is deeply compromised), difficulty monitoring personal hygiene, depression and an inability to detect noxious fumes. In older adults, this can lead to weight loss, malnutrition, frailty, inadequate personal care, and accidents caused by gas leaks or fires.

Jerome Pisano, 75, of Bloomington, Ill., has been living with smell loss for five years. Repeated tests and consultations with physicians haven’t pinpointed a reason for this ailment, and sometimes he feels “hopeless,” Pisano admitted.

Before he became smell-impaired, Pisano was certified as a wine specialist. He has an 800-bottle wine cellar. “I can’t appreciate that as much as I’d like. I miss the smell of cut grass. Flowers. My wife’s cooking,” he said. “It certainly does decrease my quality of life.”

Smell loss is also associated in various research studies with a higher risk of death for older adults. One study, authored by Pinto and colleagues, found that older adults with olfactory dysfunction were nearly three times as likely to die over a period of five years as seniors whose sense of smell remained intact.

“Our sense of smell signals how our nervous system is doing and how well our brain is doing overall,” Pinto said. According to a review published earlier this year, 90% of people with early-stage Parkinson’s disease and more than 80% of people with Alzheimer’s disease have olfactory dysfunction — a symptom that can precede other symptoms by many years.

There is no treatment for smell loss associated with neurological illness or head trauma, but if someone has persistent sinus problems or allergies that cause congestion, an over-the-counter antihistamine or nasal steroid spray can help. Usually, smell returns in a few weeks.

For smell loss following a viral infection, the picture is less clear. It’s not known, yet, which viruses are associated with olfactory dysfunction, why they damage smell and what trajectory recovery takes. Covid may help shine a light on this since it has inspired a wave of research on olfaction loss around the world.

“What characteristics make people more vulnerable to a persistent loss of smell after a virus? We don’t know that, but I think we will because that research is underway and we’ve never had a cohort [of people with smell loss] this large to study,” said Dalton, of the Monell center.

Some experts recommend smell training, noting evidence of efficacy and no indication of harm. This involves sniffing four distinct scents (often eucalyptus, lemon, rose and cloves) twice a day for 30 seconds each, usually for four weeks. Sometimes the practice is combined with pictures of the items being smelled, a form of visual reinforcement.

The theory is that “practice, practice, practice” will stimulate the olfactory system, said Charles Greer, a professor of neurosurgery and neuroscience at the Yale University School of Medicine. Although scientific support isn’t well established, he said, he often recommends that people who think their smell is declining “get a shelf full of spices and smell them on a regular basis.”

Richard Doty, director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Smell and Taste Center, remains skeptical. He’s writing a review of smell training and notes that 20% to 30% of people with viral infections and smell loss recover in a relatively short time, whether or not they pursue this therapy.

“The main thing we recommend is avoid polluted environments and get your full complement of vitamins,” since several vitamins play an important role in maintaining the olfactory system, he said.

Judith Graham is a Kaiser Health News contributor.

A temporary treatment for SAD

“Christmas Cactus, Winter Light” (oil on panel), by Yvonne Troxell Lamothe, in the show “Beyond the Curve,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, Dec. 3-Jan. 16

The gallery says:

“{Ms. Lamothe} has been producing both oil paintings and watercolors mainly completed en plein air. Yvonne embraces her roots in New England. Finding intrigue with marshlands, woodlands and glorious vistas of Quincy, Mass., and Greater Boston’s South Shore, where she now lives and her cabin in Ossipee, N.H., and the White Mountains where she finds solitude gives her ample inspiration for painting. Trips to the Maine coast and Vermont offer great additional and endless places to stop and paint. It is no wonder that such a range of American painters have found their way here to New England. Among her favorites are Marsden Hartley, Lois Dodd and Milton Avery. Her paintings show close connections to the earth because of the unusual perspectives that she finds to insure a closeness to her subject. Color is of essence to Yvonne and this joy can be felt in her work. And, of course, as the earth becomes more threatened, she hopes her paintings will inspire others to take time to appreciate and celebrate our planet.’’

View of Marina Bay and Boston across Quincy Bay from Wollaston Beach, in Quincy

Center Ossipee in 1915

CVS wants stores with affluent customers — obviously; many others might be closed

In Coventry, Conn.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Woonsocket, R.I.-based CVS plans to close 10 percent of its stores. This may well be because of intensifying competition from Amazon, Walmart, etc., and the proliferation of cheap stores such as Dollar General that plan big expansions in offerings of health-related stuff. And the mail-order drug business will keep expanding.

Which stores will they close around here? I’ll bet they’ll be in poorer neighborhoods, with fewer well-insured people. CVS stores in affluent neighborhoods, such as Wayland Square, on Providence’s East Side, will survive.

Big and hugely profitable hospital chains such as Mass General Brigham are also acting to get more affluent, well-insured customer/patients by setting up mini hospitals in rich suburbs. That raises questions about what happens to the quality of care of patients in poor places as more resources are shifted to the suburban land of milk and honey.

‘Endless undulation’

“View Across Frenchman's Bay from Mount Desert Island After a Squall’’ by Thomas Cole (1845)

“There are times when a man wants solitude, and particularly this is so when he is watching the endless undulation of the sea.’’

— Dudley Cammett Lunt (1896-1981) lawyer and writer, in The Woods and the Sea: Wilderness and Seacoast Adventures in the State of Maine. He was born in Portland, Maine, but lived most of his life in Delaware while returning each year for summer vacations in The Pine Tree State.

Have a seat but bring your own cushions

“Bent Bench” (black locust, concrete and stainless steel), by Mitch Ryerson, at the Art Complex Museum, Duxbury, Mass.

The museum explains:

”As part of our 50th anniversary celebration {this year} we held a call for artists for outdoor seating. Mitch Ryerson was one of five artists we chose to create benches to be placed in our newly landscaped woodland path. Mitch is an artist, designer and craftsperson specializing in wood structures and furniture. He began his career building wooden boats in Maine.’’

Todd McLeish: Small rodents play important roles in maintaining woodland ecosystems in N.E.

Female White-Footed mouse on sumac bush.

— Photo by Peterwchen

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

When University of Rhode Island teaching professor Christian Floyd brought students in his mammalogy class to a nearby forest in September to set 50 box traps to capture mice and other small mammals, he was surprised the next morning when more than half of the traps contained a live white-footed mouse.

“I usually expect to catch three or four, and on a good year we’ll get about 12, but you never get 50 percent trap success,” URI’s rodent expert said. “White-Footed Mouse populations fluctuate in boom and bust years, and this year seems to be a boom year.”

Floyd speculated that abundant acorns, recent mild winters and healthy growth of concealing vegetation were probably factors in the unusual numbers of mice captured this year. But whatever the reason for their abundance, healthy mouse populations are a good sign for local forests.

A new study by scientists at the University of New Hampshire concluded that small mammals such as mice, voles, shrews and chipmunks play a vital role in keeping forests healthy by eating and dispersing the spores of mushrooms, truffles, and other fungi to new areas.

According to Ryan Stephens, the post-doctoral researcher at UNH who led the study, all trees form a mutually beneficial relationship with fungi. Healthy forests are dependent on hundreds of thousands of miles of fungal threads called hyphae that gather water and nutrients and supply it to the trees’ roots. In return, the trees provide the fungi with sugars they produce in their leaves. Without this symbiotic relationship, called mycorrhizae, forests would cease to exist as we know them.

Different fungal species enhance plant growth and fitness during different seasons and under different environmental conditions, so maintaining diverse fungal communities is vital for forest composition and drought resistance, according to Stephens.

But fungal diversity declines when trees die because of insect infestations, fires and timber harvests. That is why the role of small mammals in dispersing mushroom spores is so critical to forest ecology.

To effectively support healthy forests, Stephens said these animals must scatter spores of the right kind of fungi in sufficient quantities and to appropriate locations where tree seedlings are growing. But not every kind of small mammal disperses all kinds of spores, so it’s imperative that forest managers support a diversity of mammal species in forest ecosystems.

“By using management strategies that retain downed woody material and existing patches of vegetation, which are important habitat for small mammals, forest managers can help maintain small mammals as important dispersers of mycorrhizal fungi following timber harvesting” and other disturbances, Stephens said. “Ultimately, such practices may help maintain healthy regenerating forests.”

Distributing mushroom spores isn’t the only important role played by mice and voles in the forest environment. They are also tree planters.

“Almost all rodents cache food — they have a cache of acorns, seeds, maybe truffles, little bits of mushrooms,” Floyd said. “Our oak forests are probably all planted by rodents. They scurry around and dig holes and bury things.”

White-Footed Mice, which Floyd said are the most abundant mammal in Rhode Island, are also voracious consumers of the pupae of gypsy moths.

“For a mouse, gypsy moth pupae are like little jelly donuts; they’re a delicacy,” he said. “The theory is that when mouse numbers are high, they can regulate gypsy moth populations.”

Mice, voles, shrews and chipmunks are also the primary prey of most of the carnivores in the forest, from hawks and owls to foxes, weasels, fishers, and coyotes. These small mammals are a vital link in the food chain between the plant matter they eat and the larger animals that eat them.

Are these small mammals the most important players in maintaining healthy forests? Probably not. Floyd believes that accolade probably goes to the numerous invertebrates in the soil. But this new research on the dispersal of mushroom spores by mice and voles may move them up a notch in importance.

Todd McLeish is an ecoRI News contributor.

David Warsh: When I started to swim into the history of inflation

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

A deft headline last week on a Businessweek cover-story about inflation – “the fear is real but maybe the monster isn’t” – reminded me of the recession winter of 1974-1975, when the editor of Forbes, Jim Michaels, asked me to write a story about whether the spiraling inflation of the 70s might someday suddenly stop. Michaels was well-known for doing things like that

I was new on the job, fresh out of college, acutely conscious of the fact that I hadn’t taken Economics 101 while studying all kinds of other social-science stuff. My thoughts turned at once to measurement.

I found what I was looking for downstairs in the library: a volume of essays from the journal of the Economic History Society, and, in it, an article by E.H. Phelps Brown and Sheila Hopkins – “Seven Centuries of the Prices of Consumables, Compared with Builders’ Wage-Rates.”

I can’t offer picture of the key graphic, “Price of a composite unit of consumables in Southern England 1264-1954,” unless you have access to it here on JSTOR. Happily, though, history professors at the University of Oregon have neatly abstracted the key information here. In the current circumstances, it is definitely worth a look.

A couple of sharp spikes in prices occurred in the 14th Century, each of them relatively quickly reversed. One was apparently associated, at least in time, with the great famine of 1315-1317; the other with the Black Death, a flea-borne plague that had originated in Asia. These short-lived price disturbances were followed by 150 years of relative stability, before at the 16th Century the price of the cost-of-living composite began a steady ascent.

This unprecedented period of rising prices ended two centuries later in southern England, around 1700, but the cost of living in the specified fashion never again return to anything like its former level. The 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries presented smaller puzzles of their own. But adding, roughly, the price increases of the twenty years since 1954, and assuming, for the sake of argument, that measured prices might not return to their pre-1914 level, the only experience in those 725 years of a magnitude similar to the years after World War II were those of the unreversed surge in the money cost of living in the 15th and 16th centuries.

That was my introduction to the “price revolution” of the 17th Century, or “the Tudor inflation,” as Phelps Brown and Hopkins had called it.

Those articles led me on a merry chase, first to two scholars of the period of interest, both at the University of Chicago. It turned out that the facts of the price revolution were well-established, and had been understood in a certain way since Jean Bodin, in 1556, first pointed to the influx of New World gold and silver.

In 1934, Earl J. Hamilton published American Treasure and the Price Revolution in Spain, 1501-1650; in 1940, John Nef had produced Industry and Government in France and England 1540-1640, followed ten years later by War and human progress: an essay on the rise of industrial civilization.

I called and found Hamilton at work at his desk, In the course of a lengthy conversation about various differences of opinion about the cause of changes in money prices, he pointed me toward Joseph Schumpeter’s posthumously published History of Economic Analysis (1954). I bought a copy in a shop around the corner for what then seemed like an extravagant price, $10.

I didn’t phone Nef, who was retired and living in Washington, D.C. I had learned from his autobiography, Search for Meaning; the autobiography of a nonconformist (1973), that he had engaged in a disagreement with Frederick Hayek, his colleague on Chicago’s Committee on Social Thought, as to whether, in Nef’s opinion, economic doctrines posed a greater threat to Christianity, than, in Hayek’s view, “scientism” posed to economics. That seemed too rich for me.

I learned from Schumpeter that economists for centuries had differed among themselves about the virtues of “real” vs. “monetary” analysis. Real analysis, he wrote, maintains that all the essential phenomena of economic life “are capable of being describe in terms of goods and services.…” In this view, he continued, money is considered simply a “veil,” a technical device adopted to facilitate transactions. Monetary analysis, on the other hand, denies that money is of secondary importance in understanding economic processes.

We need only observe the course of events during and after the California gold discoveries to satisfy ourselves that these discoveries were responsible for a great deal more than a change in the unit of account in which values are expressed. Nor have we any difficulty in realizing – as did A. {Adam}Smith – that the development of an efficient banking system may make a lot of difference to the development of a nation’s wealth.

Thus did the price revolution and Schumpeter lead me to Adam Smith, and I have been reading him on these topics, on and off, ever since.

As it happened, Andrew Skinner, of the University of Glasgow, was in Manhattan the next year, promoting the six-volume Oxford commemorative edition of Smith’s works that he had co-edited. With a wink and nudge, Skinner also suggested I buy the two-volume edition of Sir James Steuart’s An Inquiry into the Principles of Political Economy that he had prepared for the Sottish Economic Society. I’ve always been glad that I did.

It was about then, too, that I read Douglas Vickers article on “Adam Smith on the Status of the Theory of Money” in the Skinner-edited volume, Essays on Adam Smith, with its discussion of “the enigma of Smith’s view of the relative unimportance of money in the explanation of the monetary economy….” And the year I began reading Milton Friedman.

Three years after that, Paul Volcker, as chairman of the Federal Reserve Board engineered an experiment in the role of money in monetary economies whose implications continue to be widely explored.

Ever since then, I have been deeply interested in central bankers and what they do. Not long after Volcker left office, An economist friend casually remarked that people who come to economics from the outside (he meant people like me) are either drawn into its orbit or go flying off on their tangent, never to return. I had been drawn in.

I have also come to believe that macroeconomists and central bankers themselves don’t completely understand the science behind what they do well enough to explain it to themselves, much less to the rest of us, though they clearly possess much technological knowledge. If that is the cases, great opportunities await theorists an applied economists alike. Central bankers, meanwhile, are left having to continue to muddle through.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

Chris Powell: Scenes from Weimar America; how about neither senile nor crazy, neither far left nor far right?

Adolf Hitler and his followers in 1932, the final year of the Weimar Republic (1919-1933). Genocide and world war followed.

Right-wing vigilante Kyle Rittenhouse shows his stuff.

Car lot destroyed by Kenosha rioters.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

With proto-Nazis and proto-Commies brawling in the streets across Weimar America, it may be more important than ever to recall Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter's wry observation that "the safeguards of liberty have been forged in controversies involving not very nice people."

At best Kyle Rittenhouse is a stupid and reckless kid and a gun nut who enlisted in a search for trouble and found it in Kenosha, Wis., among rioters, some of them armed, who purported to be enraged by the shooting of a Black man by local police.

Carrying a military-style rifle, Rittenhouse went to Kenosha in the name of protecting property against rioters and ended up killing two of them and maiming a third, all of them white, as Rittenhouse himself is.

Rittenhouse was vigorously prosecuted but, supported by video evidence and even the testimony of a prosecution witness, he maintained that the three men he shot were attacking him, and the jury acquitted him.

Now, because the rioters Rittenhouse shot were rioting in the name of a Black man, the political left is portraying them as martyrs and Rittenhouse as a white supremacist, though there is no evidence that racial oppression was or has ever been his objective. This unfairness to Rittenhouse has prompted the political right to declare him a hero of the right of self-defense and the Second Amendment.

But there were no martyrs or heroes in the brawling in Kenosha, just idiots. When politics is stripped away, Rittenhouse's acquittal fits the facts as the jury could have found them, and if the political left and right were not so crazed and hateful they would be looking for heroes elsewhere.

Of course that's not likely to happen. Instead the Rittenhouse case is inspiring protests and confrontations throughout the country, including Connecticut, where a week ago a group that had been threatening to level the Amazon warehouse in Windsor because ropes resembling nooses had been found there began blocking traffic in the center of Manchester.

Blocking traffic is a good way of looking for trouble too, especially when so many people are stressed and on edge because of the lengthy virus epidemic. People protesting in the name of environmental protection lately have been blocking traffic in the United Kingdom and getting attacked by people trying to get to work.

So as the Rittenhouse verdict protesters were blocking traffic in Manchester, a car stopped in front of them and then slowly pushed through them before driving off. The protesters were able to get out of the way and no one was really hurt, but they all were indignant that their lawbreaking wasn't appreciated but instead was resented as a provocation.

Indeed, some of them are gun nuts just like Rittenhouse and have carried and displayed guns at their previous protests, though no one has been threatening them. In Manchester last weekend they claimed to be armed as well and seemed to want to be considered heroes for not shooting at the car that had nudged them out of the way.

There is good identification of the car and if the police locate and arrest the driver maybe Manchester will be the scene of another trial to which racial implications will be falsely and opportunistically attached. As in Kenosha, MSNBC and Fox News could cover it and designate new heroes and villains, and the verdict could set off its own protests and riots.

Or maybe, realizing that there are still many more civilized ways to make a point, people could resolve to make their points without getting into each other's faces, even if that is less dramatic and satisfying to the ego.

xxx

A national poll three years ago found that nearly half the country questioned President Trump's mental stability and intelligence. Now another national poll has found that about half the country questions President Biden's mental fitness for his office and believes that his health is deteriorating.

Unfortunately, other polls say Vice President Kamala Harris's standing with public opinion is even worse.

So the next act of politics in Weimar America may be the restoration of Trump, unless someone soon can start a sensible third party whose platform might be simple:

Neither crazy nor senile, neither far left nor far right.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Post-season

"Work Horse" (acrylic on birch panel), by Alan Bull, a Newburyport, Mass.-based artist. Now on view at Battle Grounds Coffee Co., Newburyport. See The Art of Alan Bull.