Grave matters

Part of the Ancient Burying Ground in Hartford, with the First Church of Christ (aka Congregational), the congregation's fourth church, built in 1807, next to it. The cemetery, which dates back to 1636, was the city's sole cemetery until 1803.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24

New England Cemeteries: A Collector’s Guide, by Andrew Kull, is extensive (260 places!) and honest. He describes ugly and badly maintained and even abandoned graveyards as well as such grand, gorgeous 19th Century “garden cemeteries’’ as Providence’s Swan Point Cemetery and Mt. Auburn Cemetery, on the Cambridge-Watertown line, just outside of Boston.

Some are ancient, by American standards, with the oldest probably at Cole’s Hill, in Plymouth, Mass. (1620), and King’s Chapel Burying Ground, in Boston, dating to 1630.

Mr. Kull notes:

“People who have never paid much attention to the subject tend to think that one graveyard is much like another. In some parts of the country this is undoubtedly the case. In New England, a longer history has included changing attitudes toward death and its proper commemoration.’’

I love some of the gravestone inscriptions Mr. Kull quotes, such as this on the grave of Samuel Stone (who died in 1663) in Hartford’s Ancient Burying Ground (1636):

“Errors corrupt by sinnewous dispute

He did oppugne, and clearly them confute:

Above all things, he Christ his Lord prefer’d

Hartford! Thy richest jewel’s here interd.’’

This book was published way back in 1975 but I think it still holds up as a guide to many places, lovely or not, that inspire reflection about transitory lives and the sweep of history. Vermont native Mr. Kull (also a distinguished legal scholar) was born in 1947. But he isn’t yet a resident of a cemetery.

In Mt. Auburn Cemetery

‘Playground’

From Jennifer Moses’s show “Rock, Paper, Scissors” (gouche on paper), at Kingston Gallery, Boston, Dec. 1-Jan. 16.

The gallery says from her statement:

“…. Moses explores a playground game literally and metaphorically. This classic game of chance and anticipation is designed to negotiate conflicts, make decisions, and establish power; rock dominates scissors, paper binds rock, and scissors cut paper. The game is also a metaphor for art-making, in which one aesthetic or conceptual choice supplants another. This kind of improvisational response is a signature of Moses's approach to constructing images.’’

‘Uncaged and free’

View of Mission Church and the Boston skyline from near the top of Mission Hill. Mission Church is the popular name of the Basilica and Shrine of Our Lady of Perpetual Help, a Roman Catholic basilica. The Redemptorists of the Baltimore Province have ministered to the parish since the church was opened, in 1870.

“Down around here positive minds meet; Plotting dreams into plans that manifest into beats; Well here you got a problem speak it coolly and calmly; Cause we're supporting those with evolved mentalities; Boston here fluent in stroll; The people's confidence is full in control; You'll find me at 42 longitude 71 latitude; Only European-style city in the US man; It's arguable Jamaica Plain, Mission Hill, my worn out sneaks; Just hanging out on rooftops uncaged and free”

—From the song “Down Around Here” by Big D and the Kids Table (2009)

‘Blue and bluer still’

Welcome to Boston!

“When the cold comes to New England it arrives in sheets of sleet and ice. In December, the wind wraps itself around bare trees and twists in between husbands and wives asleep in their beds. It shakes the shingles from the roofs and sifts through cracks in the plaster. The only green things left are the holly bushes and the old boxwood hedges in the village, and these are often painted white with snow. Chipmunks and weasels come to nest in basements and barns; owls find their way into attics. At night, the dark is blue and bluer still, as sapphire of night.”

—Alice Hoffman (born 1952), Boston-based novelist, in Here on Earth.

The plot involves a woman named March Murray, who returns with her teenage daughter to the small Massachusetts town where she grew up, in a story inspired by the 1847 Emily Brontë novel Wuthering Heights. In the town, March is reunited with the boy she fell in love with years before. But, "{I}n heaven and in our dreams, love is simple and glorious. But it is something altogether different here on earth.…"

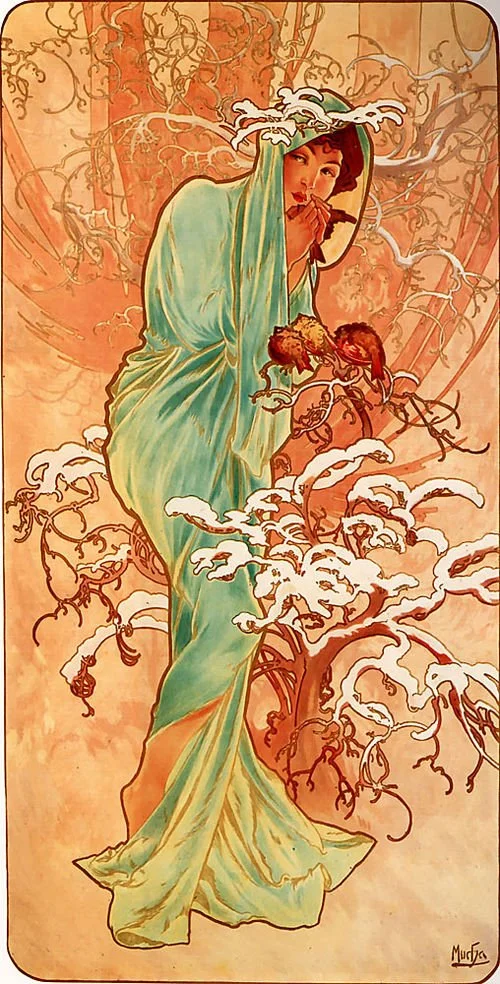

“Winter,” by Alfons Mucha (1896)

A raging ‘diminutive jock’

Coxswain, at the right and yelling, at the Head of the Charles (River) Regatta.

“In crew, contempt is important. In Boston, Boston University and Northeastern crew are treated with contempt by the college up the river. Intramural crew is treated with contempt. Nonathletic coxswains (Chinese engineering majors, poets) are treated with contempt. A true coxswain is a diminutive jock, raging against the pint size that made him the butt of so many jokes at Prep school. He runs twenty stadiums a day, his girlfriend is six feet one, and he can scream orders even when he has the flu (which he catches at least three times a winter).”

— From The Official Preppy Handbook, by Lisa Birnbach

Memory and dream ‘in transit’

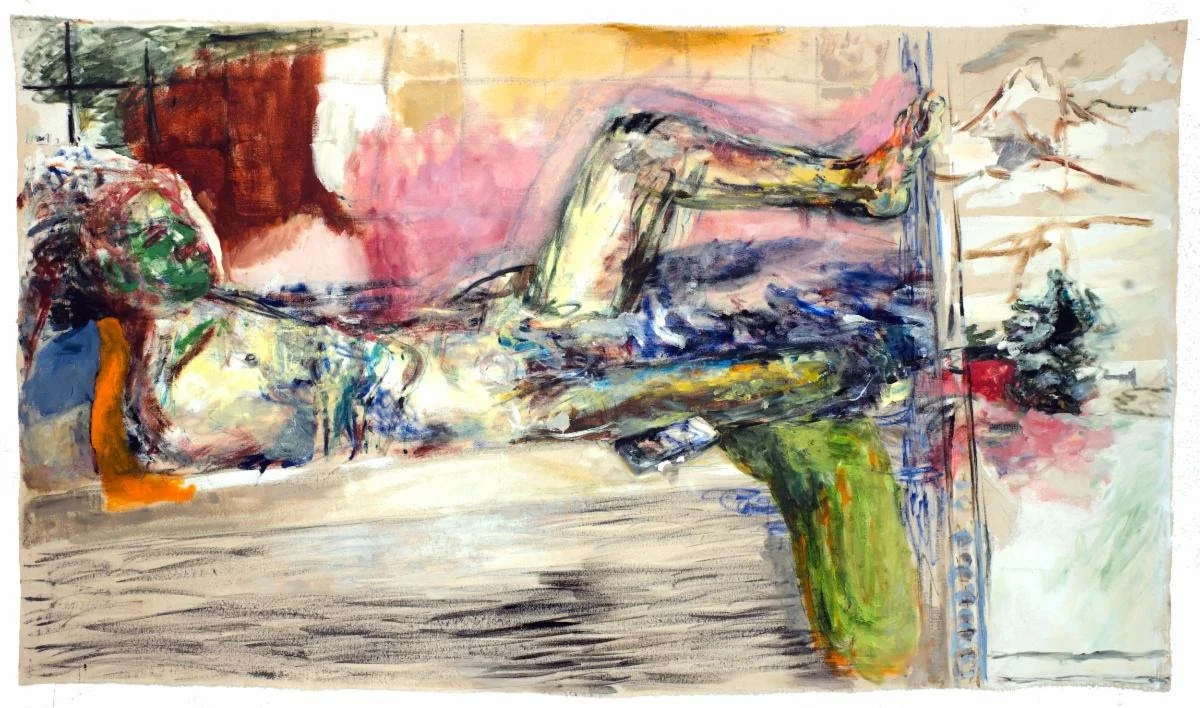

“Allan in Bathtub” (oil and mixed media on unstretched canvas), by Alexandra Thompson, in her show “Returning Trains,’’ at Gallery 444, Provincetown, Mass., through Dec. 6.

The gallery says:

“In paint, sculpture and drawing, {she creates a} landscape of memory and dream in transit between the Midwest and the Atlantic…’’ employing “a rawness of material and image.’’

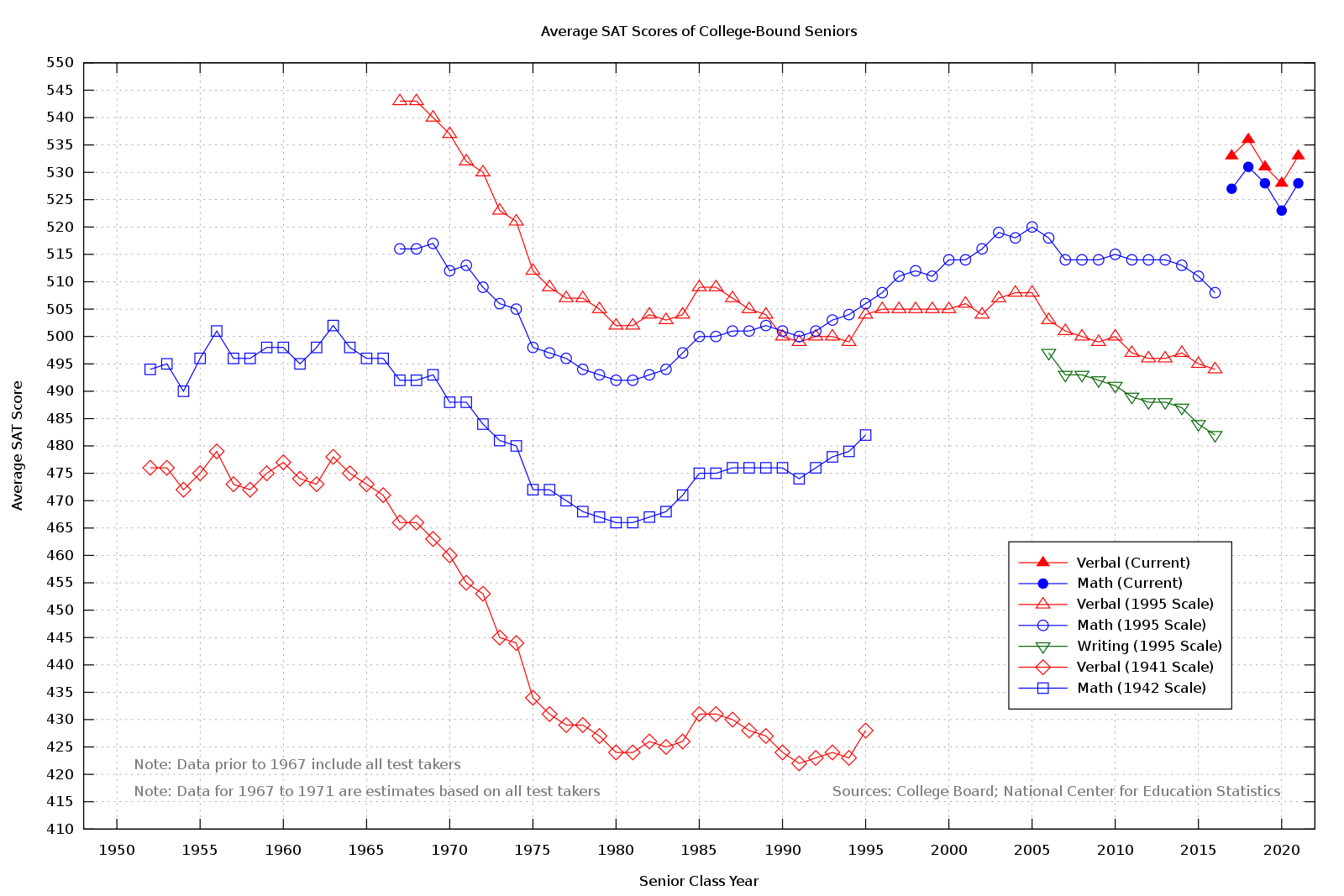

Josh M. Beach: Why we can’t measure what matters in U.S. education

Via The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

What do students learn in school? In the 21st Century, this question has become a political dilemma for countries around the globe. It is a deceptively simple question, but there has never been an easy answer.

The problem of measuring student learning appears to express an educational problem: What and how much do students learn? And yet, when you investigate the education-accountability movement, especially in the U.S. where it began, you realize that the preoccupation with student learning is not about education. Calls for accountability have always been more focused on politics and economics.

Accountability metrics were created to sort and rank students, teachers and schools in order to create a competition where some are winners and most are losers. This type of competitive environment creates fear, and it is not conducive to learning or high performance.

Most student learning, especially the most important types of social learning and formative interactions, happens outside school, especially in early childhood. These personal experiences later go on to affect students’ performance in schools. The most important variables that affect a student’s school achievement are environmental. They occur outside schools and affect children long before they ever set foot in a school. These three variables, which are deeply intertwined, are the social construction of: race, parental income and wealth, and parental education (especially the highest level of schooling that parents achieve).

All three of these variables are proxies for a wide range of social and economic resources that can help students learn and succeed in school, such as parenting skills and child development, especially the time parents spend talking to and reading with children, proper nutrition, access to tutors and extracurricular activities, access to top-quality schools with the best teachers, and also peer networks.

Most policymakers and school administrators talk as if schools and teachers have complete control over the student learning process, but most of the important variables that determine student success, especially in terms of learning and graduating, are beyond the control of teachers or schools.

As W. Edwards Deming pointed out, “Common sense tells us to rank children in school (grade them), rank people on the job, rank teams, divisions … Reward the best, punish the worst.” (This common-sense belief is wrong, especially, as Deming emphasized, when it comes to schooling, where the objectives are supposed to be student learning and personal development.)

Over the past half century, social scientists have found that there can be many unintended and adverse consequences when high-stake metrics get linked to individual or institutional evaluations tied to punishments and rewards.

This predicament is often called Campbell’s Law. The psychologist and social scientist Donald T. Campbell explained in 1976, “The more any quantitative social indicator is used for social decision-making, the more subject it will be to corruption pressures and the more apt it will be to distort and corrupt the social processes it is intended to monitor.”

A British economist put it more bluntly in what is now called Goodhart’s Law: “Any measure used for control is unreliable.”

According to Campbell, “When tests scores become the goal of the teaching process, they both lose their value as indicators of educational status and distort the educational process in undesirable ways.”

How have accountability measurements corrupted schools? Take high-stakes standardized testing as a perfect example. Many teachers now spend most of their classroom time teaching to the tests by giving students “tricks” to answer multiple-choice tests or “ways to game the rules used to score the tests,” according to Harvard Graduate School of Education Prof. Daniel Koretz. Students engage in little, if any, real or useful learning.

Grade inflation

Teachers have also been lowering their standards and inflating grades to make students look much more successful academically than they actually are. Some administrators have been manipulating the tested population of students to make sure the lowest-performing students don’t take high-stakes tests. Sometimes, this has taken the form of transferring low-achieving students to other schools or encouraging them to drop out of school. And most shamefully, some teachers and administrators have been engaging in plain old cheating by falsifying student achievement scores.

To make matters worse, because performance measures cannot be verified, judgments of quality are made on existing data, which can be manipulated, or can be partially or wholly fraudulent. This leads to the adverse selection of personnel, whereby deceitful agents who post the best performance markers get rewarded, even though their numbers may be questionable, if not fraudulent.

Often, as Koretz points out, “the wrong schools and programs” get “rewarded or punished, and the wrong practices may be touted as successful and emulated.” The opposite is also true. Honest, hard-working and effective teachers, with true but lackluster performance measures, are passed over for promotion, criticized, sanctioned or fired. Such moral hazards create a perverse Darwinian scenario: Survival of the corrupt.

When performance goals are mandated from above without employee input, subordinates are forced to follow meaningless targets without any intrinsic motivation. Thus, the only incentive for workers to succeed are extrinsic rewards, often money, which leads to shortcuts or fraud to get the monetary reward. Staff begin chasing performance markers for the monetary incentives without knowing about or caring about the fundamental purposes of the organization or the rationale behind accountability goals.

Thus, when it comes to schools, whenever lawmakers or administrators institute a single, predictable measure of academic performance linked to extrinsic rewards, whether it be for students, teachers, or the whole school, someone somewhere will be cheating to game the system.

A 2013 Government Accounting Office report concluded that “officials in 40 states reported allegations of cheating in the past two school years, and officials in 33 states confirmed at least one instance of cheating. Further, 32 states reported that they canceled, invalidated or nullified test scores as a result of cheating.” One scholarly study estimated that “serious cases of teacher or administrator cheating on standardized tests occur in a minimum of 4-5 percent of elementary school classrooms annually.” Temple University psychologist Laurence Steinberg sardonically quipped, “Fudging data on student performance” has been “the only education strategy that consistently gets results.”

Nationwide in the U.S., we are seeing the consequences of this cynical calculation. For decades, researchers have documented rampant social promotion and grade inflation in K-12 schools and in most institutions of higher education. Koretz has argued that grade inflation is not only “pervasive,” but also “severe,” so much so that he argued that this type of subtle cheating is “central to the failure of American education ‘reform.’”

In Houston, as an example, some high schools were officially reporting zero dropouts and 100% of their students planning to attend college, and yet one principal joked, most of her students “couldn’t spell college, let alone attend.” While Texas pioneered accountability reforms in K-12 education, which became national policy through George W. Bush’s landmark No Child Left Behind law, researchers have documented how those reforms led to the corruption of education in Texas. Policymakers and administrators lost sight of education in a push to fudge the numbers so they could secure public accolades, get more funding and build bigger football stadiums.

And what is the impact of grade inflation on students? While students no doubt like high grades that they have not academically earned, they are actually harmed a great deal by such educational fraud. First of all, students become complacent and are unmotivated to learn because they think they already know it all. When students are confronted with higher academic standards in the future, they are liable to wilt under the pressure and either blame themselves or the teacher for the difficulty of authentic learning.

Disadvantaged students hurt most

To make matters worse, grade inflation affects disadvantaged students the most. Poor students and ethnic minorities, who are often segregated in the lowest-performing schools in the poorest neighborhoods, often receive the most inflated grades. This is because their teachers often can’t teach effectively due to various social, economic and environmental conditions that obstruct the learning process.

And what happens when academically underachieving high-school students fail upwards and make it into college, mostly through the open-door community college? They are then confronted with the fact that they are unprepared for academic success.

Large percentages of freshmen in the U.S. have to start college with remedial classes because they were not adequately prepared in high school. Most of these remedial college students eventually drop out of college, for various reasons, never earning a degree, and often with substantial amounts of student debt. However, many are also just passed through the college system with inflated grades and little learning.

For decades, researchers have documented the lowering of academic standards and the inflation of grades at institutions of higher education all across the U.S., especially at community colleges.

Graduating with a degree

High grades also seem to be inversely correlated with the main measure of student success in college, which is graduating with a degree. Currently, over 80% of all college students in the U.S. are earning A or B grades, but less than half of students who enroll in higher education will actually graduate with a bachelor’s degree.

As college admissions rose, graduation rates declined from the 1970s to the 1990s because standards remained relatively high. But as admissions continued to rise, graduation rates began to increase starting in the 1990s. Students were no more academically prepared, in fact, they were less prepared, so the increase in completion rates was mostly likely due to political and administrative pressure. New accountability reforms most likely contributed to a lowering of standards, especially at non-selective public colleges and universities.

Education researchers Ernest T. Pascarella and Patrick T. Terenzini pointed out in 2005 that only about half of all college graduates “appear to be functioning at the most proficient levels of prose, document or quantitative literacy,” which means that all those inflated A and B grades aren’t translating into actual knowledge or skill, putting many college graduates at a disadvantage when they enter the labor market, and putting many firms at risk because they have hired ignorant and incompetent college graduates.

While it is certainly reasonable for teachers to use tests and grades to evaluate and measure student learning, these tools are not easy to implement in a valid way that promotes student learning and development. As Jack Schneider of the University of Massachusetts at Lowell, notes, “Measuring something as complicated as student learning” is very difficult, even under the best of circumstances, but almost impossible when it has to be done in a “uniform and cost-restricted way.” {Mr. Schneider is associate professor of leadership in education at UMass Lowell and director of research for the Massachusetts Consortium for Innovative Education Assessment.}

Josh M. Beach is the author of a number of interdisciplinary titles, including How Do You Know?: The Epistemological Foundations of 21st Century Literacy and Gateway to Opportunity? A History of the Community College in the United States. He is the founder and director of 21st Century Literacy, a nonprofit organization focused on literacy education and teacher training.

Georgian-style Longfellow Hall at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education, in Cambridge, Mass. It’s named for the daughter of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, the famous 19th Century poet and scholar.

Just me and my landscape

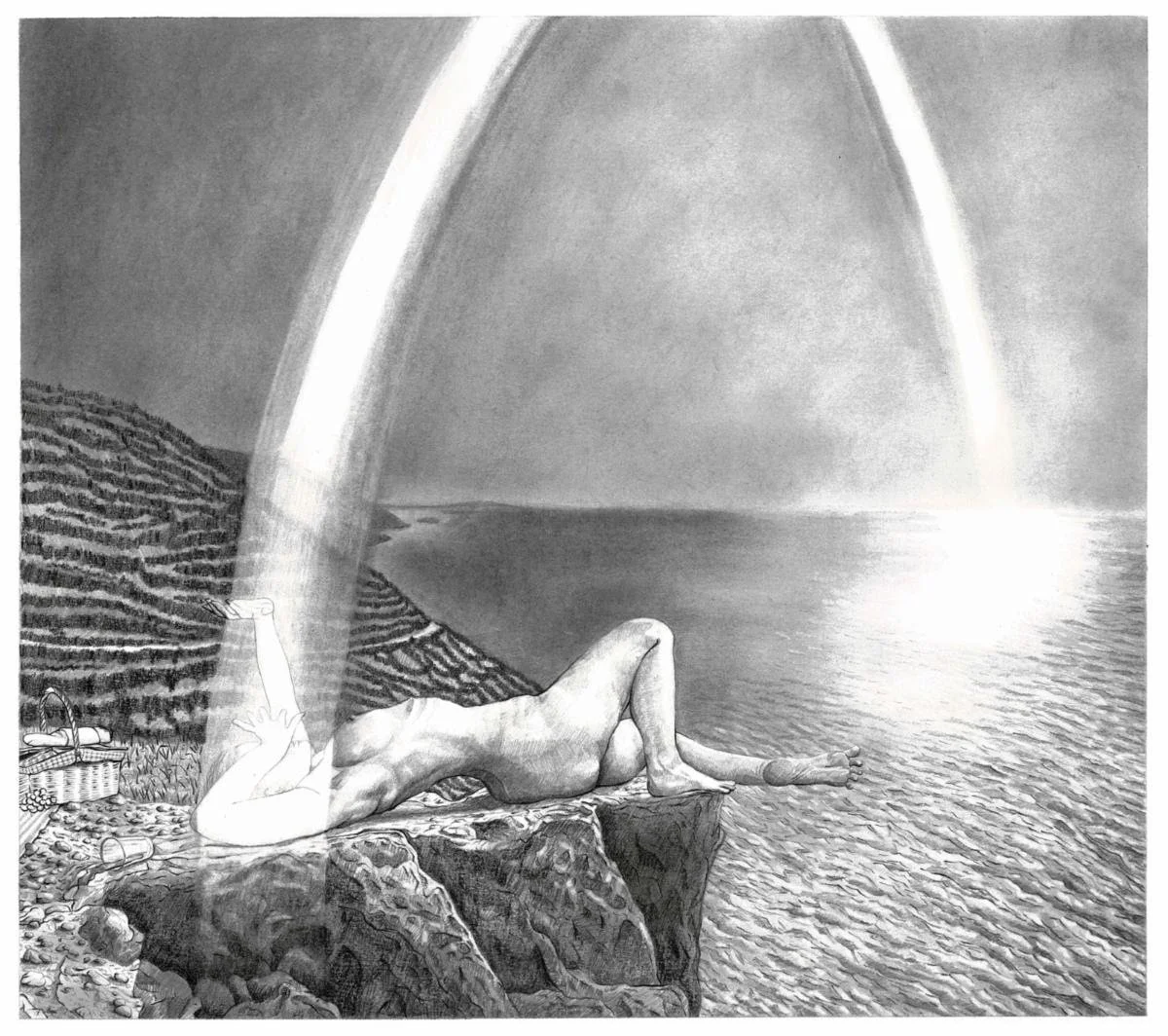

“Light” (graphite and charcoal on paper), by New York-based Catalina Viejo Lopez de Roda, in her show “Self Care’’, at HallSpace Contemporary Art Gallery, in Boston’s Dorchester section, starting Dec. 11. {Editor’s note: This reminds me of the work of Rockwell Kent.}

The gallery says: "Dealing with a persistent virus has instigated a new direction in Viejo’s work, with the central theme being Self Care. A single woman lives in isolation in each of her drawings, paintings and animations. These women inhabit wild environments and have developed a symbiotic relationship with the landscape."

‘It’s not intellectual’

Rock of Ages granite quarry in Graniteville, Vt.

]

“Never confuse faith, or belief — of any kind — with something even remotely intellectual.’’

— From A Prayer for Owen Meany, a novel by John Irving (born 1942)

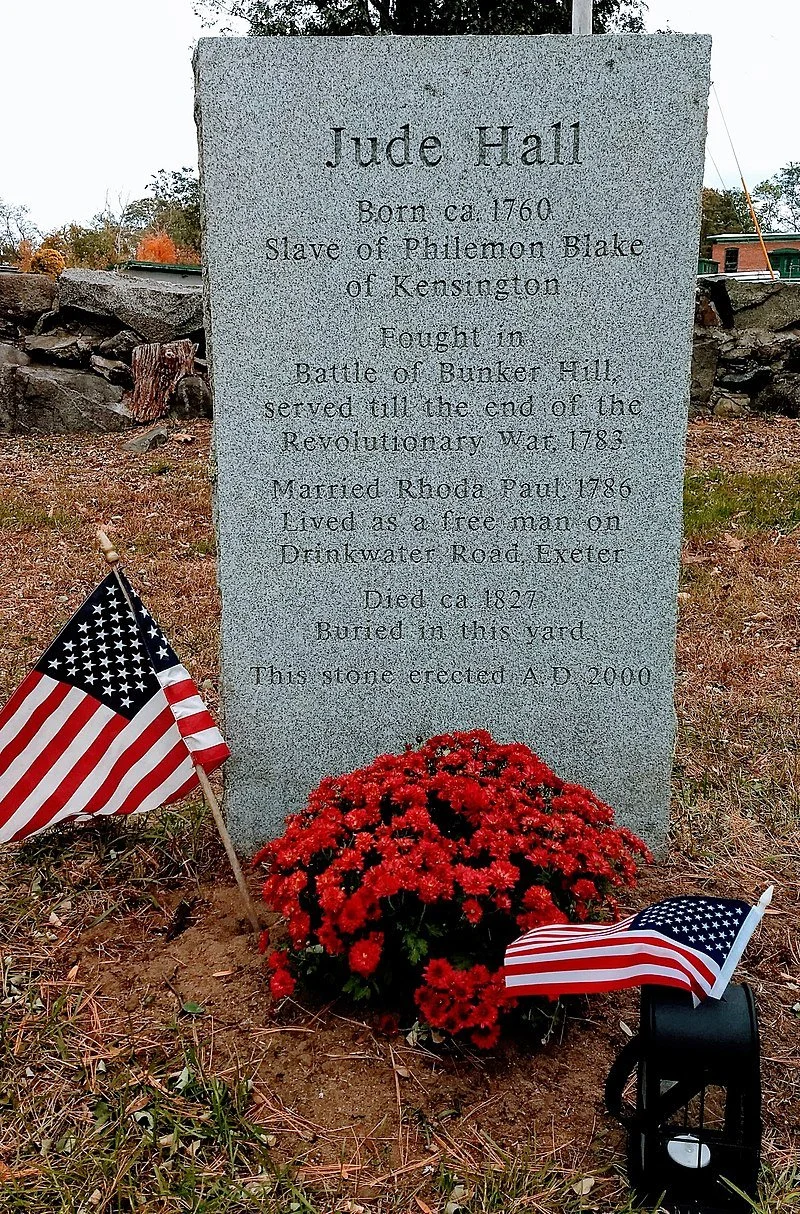

The plot centers around John Wheelwright and Owen Meany, who live in the fictional town of Gravesend, N.H. (based on Irving’s hometown of Exeter, N.H.). As boys they are close friends, although John comes from an old rich family — as the illegitimate son of Tabitha Wheelwright — and Owen is the only child of a working-class granite quarryman. John's earliest memories of Owen involve lifting him up in the air, easy because of his permanently small stature, to make him speak. And an underdeveloped larynx causes Owen to speak in a high-pitched voice. During his life, Owen comes to believe that he is "God's instrument".

Jude Hall granite memorial stone in Exeter, N.H.

A still, very New England place for reflection, not feasting

On Thanksgiving: In Jaffrey Center, N.H., with Mt. Monadnock in the background. The celebrated novelist Willa Cather is buried in Jaffrey’s Old Burying Ground.

— Photo by William Morgan

Chris Powell: Car thefts are the least of it in juvenile-justice scandal; Yale saves New Haven

Ford Explorer with broken window after it was stolen

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Democrats in Connecticut insist that there is no crime wave in the state and that concerns about crime are Republican contrivances. But it's nice that the state's minority party is pressing any issues at all, and Connecticut lately has had some criminal atrocities that really should be learned from, especially some involving juveniles.

One of those atrocities unfolded last week in Manchester, when a 14-year-old boy was charged with the rape and murder of a 13-year-old girl last June. News reports about the arrest discovered that state law prohibits the boy from being tried in open court and, if he is convicted, will prohibit him from being sentenced to anything more severe than 2½ years of probation, regardless of whether he is a predatory maniac or a great kid who made what the social workers may get away with calling a "mistake."

Whatever the boy is, the secrecy of court for murder defendants under 15 years old will prevent the public from ever finding out.

Few teenagers read newspapers or pay attention to broadcast news, but they do talk to each other and so news can spread among them all the same. Thanks to the Manchester case they now may perceive that in Connecticut they are pretty much free to rape and murder until they turn 15, and they may perceive that their exemption from criminal responsibility for car thefts, which they already well understand and that recently has become controversial, is actually the least of the scandal of juvenile justice here.

A spokeswoman for the social work school of thought, Illiana Pujols, of the Connecticut Justice Alliance, says the state's adult-justice system isn't made to serve children. But in its glorious secrecy, unaccountability and exemption of young offenders from responsibility even for atrocities, is the state's juvenile-justice system made to serve the public?

xxx

Yale University, whose ownership of so much property in New Haven takes much of it off the city's property-tax rolls, has a new six-year deal with the city. The university will increase its annual voluntary payment to the city from the current $13.2 million to $23 million, leading to total payments of more than $135 million by the arrangement's conclusion.

That kind of money could cover much of the city's underfunding of its pension programs and pay lots of raises, though whether it does much for the city itself must remain to be seen.

Mayor Justin Elicker and City Council members are thrilled by the deal, since the university, as a nonprofit corporation, isn't legally required to pay taxes on its noncommercial property. But the deal really isn't so generous.

For Yale already was suffering an embarrassment of riches, heightened by the recent stock market boom, which has boosted the university's endowment to $42 billion. The endowment has been managed extraordinarily well, so well that the joke is that Yale is actually a hedge fund disguised as a university. Yale is so wealthy that, as National Review noted the other day, it can afford to have more employees (nearly 17,000) than students (about 12,000).

But then the university's work is not just to teach but to be constantly striking politically correct poses to appease the political left that dominates it. Those poses now will be facilitated by a new city undertaking called the Center for Inclusive Growth, to which Yale will contribute $5 million over the next six years. The center may provide patronage jobs for growing still more political correctness in New Haven.

xxx

U.S. Education Secretary Miguel Cardona, briefly Connecticut's education commissioner, boasted last week of another big round of student0loan forgiveness -- $2 billion for 33,000 borrowers -- through the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program, for which teachers and employees of nonprofits are eligible.

Some of the debtors are indeed hard-pressed but as with most student-loan debt the borrowers are not the biggest beneficiaries of loan forgiveness. Student-loan debt becomes burdensome when the education for which the debt was incurred cannot qualify the borrower for a job that pays enough both to support him and repay the debt.

That is, the real beneficiaries of student loans are employees of higher education, which is overvalued and yet made still more expensive by those loans.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

‘Time nearing an end’

“Mantle” (oil and gold leaf on panel), by western Massachusetts-based Jeff Strauder, in his show “The Reckoning,’’ at the Grubbs Gallery at the Williston Northampton School, Easthampton, Mass., Dec. 5 to Jan. 5.

Mr. Strauder says "The Reckoning’’is a continuation of my preceding Pilgrim series, with an allegorical cosmology of my own design. Recurrent characters from that series appear again here, with the rising waters now an urgent threat. There is a sensation that time is nearing an end. The owl, a central new presence flanked by subservient beings, now presides over this world."

Williston Northampton School is a private, co-educational, day and boarding college-preparatory school established in 1841.

View of Mt. Tom from downtown Easthampton, in the Connecticut Valley.

Llewellyn King: Today’s lessons from the 1970’s energy crises

During the 1973-74 part of the 1970’s oil crisis.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I’ve been here before. I’ve heard this din at another time. I’m writing about the cacophony of opinions about global warming and climate change.

In the winter of 1973, the Arab oil embargo unleashed a global energy crisis. Times were grim. The predictions were grimmer: We’d never again lead the lives we had led -- energy shortage would be the permanent lot of the world.

The Economist said the Saudi Arabian oil minister, Sheik Ahmad Zaki Yamani, was the most important man in the world. It was right: Saudi Arabia sat on the world’s largest proven oil reserves.

Then as now, everyone had an answer. The 1974 World Energy Congress in Detroit, organized by the U.S. Energy Association, and addressed by President Gerald Ford, was the equivalent in its day to COP26, the UN Climate Change Conference which has just concluded in Glasgow, Scotland.

Everyone had an answer, instant expertise flowered. The Aspen Institute, at one of its meetings, held in Maryland instead of Colorado to save energy, contemplated how the United States would survive with a negative growth rate of 23 percent. Civilization, as we had known it, was going to fail. Sound familiar?

The finger-pointing was on an industrial scale: Motor City was to blame and the oil companies were to blame; they had misled us. The government was to blame in every way.

Conspiracy theories abounded. Ralph Nader told me that there was plenty of energy, and the oil companies knew where it was. Many believed that there were phantom tankers offshore, waiting for the price to rise.

Across America, there were lines at gasoline stations. London was on a three-day work week with candles and lanterns in shops.

In February 1973, I had started what became The Energy Daily and was in the thick of it: the madness, the panic -- and the solutions.

What we were faced with back then was what appeared to be a limited resource base that the world was burning up at a frightening rate. Oil would run out and natural gas, we were told, was already a depleted resource. Finished.

The energy crisis was real, but so was the nonsense -- limitless, in fact.

It took two decades, but economic incentive in the form of new oil drilling, especially in the southern hemisphere, good policy, like deregulating natural gas, and technology, much of it coming from the national laboratories, unleashed an era of plenty. The big breakthrough was horizontal drilling which led to fracking and abundance.

I suspect if we can get it right, a similar combination of good economics, sound policy, and technology will deliver us and the world from the impending climate disaster.

The beginning isn’t auspicious, but neither was it back in the energy crisis. The Department of Energy is going through what I think of as scattering fairy dust on every supplicant who says he or she can help. On Nov. 1, DOE issued a press release which pretty well explains fairy dusting: a little money to a lot of entities, from great industrial companies to universities. Never enough money to really do anything, but enough to keep the beavers beavering.

That isn’t the way out.

The way out, based on what we have on the drawing board today, is for the government to get behind a few options. These are storage, which would make wind and solar more useful; capture and storage of carbon released during combustion; and a robust turn to nuclear power.

All this would come together efficiently and quickly with a no-exceptions carbon tax. Republicans will diss this tax, but it is the equitable thing to do.

Nuclear power deserves a caveat. It is unique in its relation to the government, which should acknowledge this and act accordingly.

The government is responsible for nuclear safety, nonproliferation, and waste disposal. It might as well have the vendors build a series of reactors at government sites, sell the power to the electric utilities, and eventually transfer plant ownership to them.

The government has some things that it alone is able to do. Reviving nuclear power is one.

The energy crisis was solved because it had to be solved. The climate- change crisis, too, must be solved.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Cocktail party cacophony and claustrophobia in the latest version of The Ritz

The Newbury Hotel, overlooking the Boston Public Garden. The original 1927 wing is in the middle, the 1981 wing is on the right.

“The cocktail party effect is the phenomenon of the brain's ability to focus one's auditory attention on a particular stimulus while filtering out a range of other stimuli, such as when a partygoer can focus on a single conversation in a noisy room. Listeners have the ability to both segregate different stimuli into different streams, and subsequently decide which streams are most pertinent to them.’’

— Wikipedia

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I spent a recent evening at the Newbury Hotel (the original part of which opened in 1927), the swanky establishment in Boston’s Back Bay that some of us still call The Ritz-Carlton or just The Ritz. I thought that the evening, to which I was invited by a couple of Boston friends (thank God I wasn’t charged for it) would include a tour of the hotel, but in fact it was mostly a pleasant if noisy cocktail party in the fancy Italian fashion store in the hotel called Zegna, part of the Milan-based company of that name. Zegna makes very well-made stuff that few can afford.

Drinks were followed by dinner, with many small plates of (I think) northern Italian cuisine, in the rooftop restaurant called Contessa. The joint has spectacular views of the increasingly Manhattanized Downtown Boston skyline. The often clear and windy atmosphere of late fall and winter provides the year’s most spectacular nightime views of Boston and New York.

In Contessa, a hip great-grandson of the company founder promoted the company as being very “green,’’ touting among other things its spectacular nature preserve in the Piedmont region of northern Italy. When it comes to promotion, it’s hard to beat wrapping yourself in green, especially if you’re running a high-end company. Rich people like to consider themselves environmentalists, especially when it comes to protecting land from development near their suburban or rural estates!

I had almost forgotten how noisy such events can be, with the chattering getting louder and louder as second and third drinks were consumed. Lots of quick, superficial friendliness even as some party goers (social X-rays?) relentlessly sought out the most “important’’ people while trying to politely detach themselves from those they feared might be nonentities or just boring. Tom Wolfe would have enjoyed it.

“Who are these people, and what do they want?’’ I kept asking myself, before skulking off to a corner and glancing at a magazine (not Vogue) for a quiet moment.

The Newbury, overlooking the beautiful Public Garden, had quite a colorful reputation as the Ritz-Carlton, both as place for Proper Bostonians to celebrate special events and for the glitz that came from it being for decades a popular place for Hollywood and Broadway celebrities to stay (and sometimes be outrageous in).

It had its own ways.

There was the sign that said “not an accredited egress”’ over one of the doors in the lobby and a strict dress code. More than half a century ago, soon after I landed a job as a reporter and writer at the now-long-dead Boston Herald Traveler, and feeling flush with my $175-a-week salary, I took a girl for a drink in the famous (especially for celebrated writers) ground floor bar of the hotel, whose windows looked out on the Public Garden, a view that at night curiously made it seem that the drinkers were in a bluish underwater chamber.

We ordered our drinks and enjoyed them and the salted peanuts, probably from S.S. Pierce, that purveyor of food, some of it exotic – rattlesnake meat! -- to affluent New Englanders, especially WASPs. But then, our waiter bent down and murmured in my ear: “I’m sorry, Sir. But this will have to be the last drink. The lady is not properly attired.’’ The problem was that she was wearing pants and not a dress or a skirt. But of course back then, people could smoke away to their lungs’ discontent in bars. Some things were a lot looser then.

Years before that, when someone took me as a kid to the grand and very formal dining room, I was impressed that they served unsalted butter, which seemed very exotic to my untrained palate.

Ah, old Boston….

17th Century marketing

“The First Thanksgiving at Plymouth”, by Jennie Augusta Brownscombe (1914), in Pilgrim Hall Museum, Plymouth, Mass.

“Loving Cousin,

“At our arrival {from England} at New Plymouth, in New England, we found all our friends and planters in good health, though they were left sick and weak, with very small means; the Indians round about us peaceable and friendly; the country very pleasant and temperate, yielding naturally, of itself, great store of fruits, as vines of divers sorts, in great abundance. There is likewise walnuts, chestnuts, small nuts and plums, with much variety of flowers, roots and herbs, no less pleasant than wholesome and profitable. No place hath more gooseberries and strawberries, nor better. Timber of all sorts you have in England doth cover the land, that affords beasts of divers sorts, and great flocks of turkeys, quails, pigeons and partridges; many great lakes abounding with fish, fowl, beavers, and otters. The sea affords us great plenty of all excellent sorts of sea-fish, as the rivers and isles doth variety of wild fowl of most useful sorts. Mines we find, to our thinking; but neither the goodness nor quality we know. Better grain cannot be than the Indian corn, if we will plant it upon as good ground as a man need desire. We are all freeholders; the rent-day doth not trouble us; and all those good blessings we have, of which and what we list in their seasons for taking. Our company are, for the most part, very religious, honest people; the word of God sincerely taught us ever Sabbath; so that I know not any thing a contented mind can here want. I desire your friendly care to send my wife and children to me, where I wish all the friends I have in England; and so I rest.’’

“Your loving kinsman,

William Hilton”

The autumn of 1621 is supposed to have been when “The First Thanksgiving’’ took place— a cooperative affair between the Calvinist Pilgrims who had landed at what they named Plymouth the year before and some Wampanoags, those who has survived the epidemics of disease brought by English sailors and traders in Maine after 1600. These epidemics had killed most of the Native Americans in eastern New England before the Pilgrims arrived.

Don Pesci: ‘Shrouded in silence’

The riderless (caparisoned) horse named "Black Jack" during the departure ceremony as President Kennedy’s body was taken from the U.S., Capitol.

VERNON, Conn.

I had been playing basketball and decided, possibly for the second time in my first year as a student at Western Connecticut State College, to take a shower. Most often I showered at Mrs. Gallagher’s, about three city blocks from the college, where I had been boarding with a roommate, Edward Kennedy, a red-headed Irish pool shark.

Mrs. Gallagher was our sometimes eccentric landlady whose features suggested that she was a stunner as a young lady. She liked Kennedy’s red hair. And he, who could easily wind people around his pinky, joined Mrs. Gallagher for rum toddy once a week before bedtime.

The sky, as I remember it, was overcast, the weather around 38 degrees. The November wind was gentle. Girls were bent over a red convertible, its top down, weeping over the blare of a radio.

“What’s happened?” I asked as I passed them.

“Someone killed Kennedy,” one of the girls said.

Almost whispering to myself, I muttered, “Who would want to kill Ed Kennedy?’

President Kennedy was assassinated on Nov. 22, 1963, the Friday before Thanksgiving that year. Four of us, two close friends and a student I did not know well, left the day after the assassination for Washington, D.C., to pay our respects to the fallen president. We thumbed our way, bearing a large handwritten sign: “Washington DC – Kennedy funeral.”

We made the trek in three rides, astounding I thought at the time, but then our sign was an emotional passport. The assassination had scrambled everyone’s brains and hearts. And on this day, the wounded heart of the nation lay open, dissolving all the usual political oppositional chatter.

Our last chauffeurs were two young men, both taciturn Southerners who were in need of gasoline money to make their way home.

“We don’t have much, but we can give you what we can spare.”

We gave the two $10 and were let off late at night at Union Station, a short walk from the Capitol. All four of us fell asleep on the hard benches.

Early in the morning, I felt the soft tap of a baton on the sole of my shoe, and a gentle voice peeled the sleep from my eyes.

“Time to get up boys and be about your business,” the police officer said.

Even early in the morning, the streets were lined, number crunchers later said, with upwards of a million people, some having waited patiently – silently – for 10 hours and more.

The silence suited me. During my four years in Danbury, unable to shake off a sometimes debilitating shyness, I had found comfort in the well-stocked library of Danbury State College, renamed during my time there Western Connecticut State University, writing from time to time for Conatus, the university’s literary magazine – nothing political. The political writing came much later, during the early 1980’s.

My literature professor asked me on my return from D.C. whether I had planned to write anything about the Kennedy assassination. I declined with a sharp “No.”

He would never have understood my reasoning, if one could call it reasoning.

I did not want to shatter the muffled silence – holy, in its own way – that touched everything during the ensuing days and weeks that followed. I just could not join in the general chatter, which I felt was, in some sense, obscene, because much of it was self-glorifying nonsense.

My mother, I recalled, had voted for Kennedy after the Kennedy-Nixon debates, in September 1960. My father, who was one of a handful of Republicans in Windsor Locks, Conn., a Democratic Party bastion, was astonished by this, and asked her at the supper table, where delicate matters were discussed, “Why on earth did you vote for a Democrat?”

“I found Nixon’s eyes shifty,” she said.

This revelation was followed by a muffled silence.

I married my wife, Andree, during my last year at Danbury. On a visit to her house in Fairfield, Conn., I found a framed picture of Kennedy near the family organ adorned by palms, blessed during Palm Sunday, fresh and smelling like the incense-drenched church in which we were married.

That day in Washington, we stood silent as horses’ hooves beat a tattoo on streets. First came the coffin born by white horses, wintry plums of breath streaming from the horses’ wide nostrils, these followed by “Black Jack’’, a riderless horse, boots strapped backwards covering its stirrups, then the crowd. All was shrouded in a holy silence in which, if one was paying close attention, one might hear the voice of Blaise Pascal saying, “In the end, they throw a little dirt on you, and everyone walks away. But there is One who will not walk away.”

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

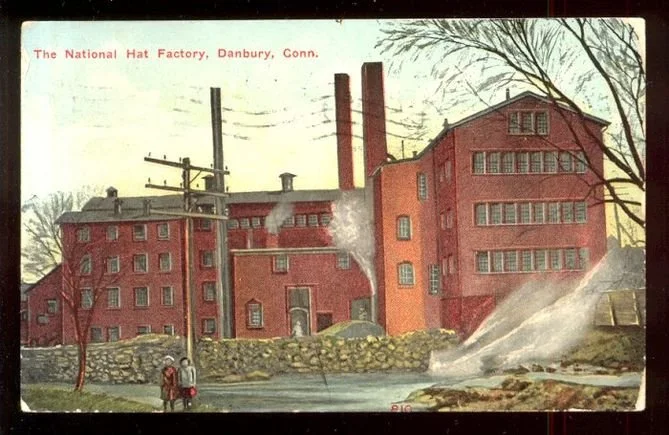

National Hat Co. factory in Danbury. For many decades Danbury was famous as a center for hat making. Sadly, mercury was used for making the felt that made up most of the hats, poisoning many workers and polluting the Still River. Connecticut didn’t ban this use of mercury until 1937.

We’re all stuck in it

“Gyre” (watercolor and ink), by Newton, Mass.-based painter James Varnum in the show “Beyond the Curve: Members’ Exhibition,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, Dec. 3-Jan. 16

He writes:

“My intent is for viewers to create an association, or an interpretation of the painting that triggers their own narrative.’’

“I was a creative child who liked to sit at the dining room table and draw. I took art classes at the local library during the summer in the small, rural village where I grew up, in Southern New Hampshire. After high school I studied art in Boston and San Francisco, where I earned a B.F.A. from the San Francisco Art Institute.

'‘I soon learned that I could not support myself and a new family as a fine artist, so I went into education, earned a M.Ed. and became a classroom teacher. After nine years, I wanted to specialize my work with children. I earned a M.S. in communication disorders and worked as a Speech Language Pathologist before retiring in 2011. During those thirty-plus years, I kept in touch with my creative side by taking art classes through various continuing education organizations.’’

”Upon retiring, I promised myself that I would pursue art once again. I kept that promise and am an active artist in the Boston area. I belong to several other art associations and actively exhibit my paintings. I classify myself as an experimental watercolor painter.’’

Chestnut Hill Reservoir, near Boston College, in Newton

‘Great equality’ in Mass. in 1789

Samuel Lincoln House, in Hingham, Mass., built on land purchased in 1649 by Samuel Lincoln, an ancestor of Abraham Lincoln

" There is a great equality in the people of this state.

Few or no opulent men, no poor. Great similitude in their buildings, the general fashion of which is a chimney (always of brick or stone), and door in the middle, with a staircase fronting the latter; two flush stories with a very good show of sash and glass windows; the size generally from 30 to 50 feet in length, and from 20 to 30 in width, exclusive of back shed, which seems to be added as the family increases.’’

— George Washington, in his journal of his tour of Massachusetts in 1789