David Warsh: A smelly red herring in Trump-Russia saga

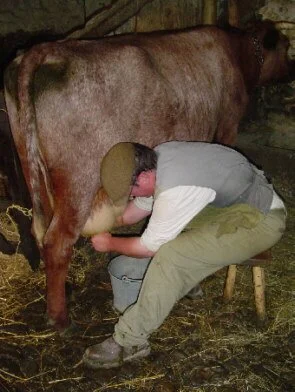

Herrings "kippered" by smoking, salting and artificially dyeing until made reddish-brown, i.e., a "red herring". Before refrigeration kipper was known for being strongly pungent. In 1807, William Cobbett wrote how he used a kipper to lay a false trail, while training hunting dogs—a story that was probably the origin of the idiom.

Grand Kremlin Palace, in Moscow, commissioned 1838 by Czar Nicholas I, constructed 1839–1849, and today the official residence of the president of Russia

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

A red herring, says Wikipedia, is something that misleads or distracts from a relevant and important question. A colorful 19th Century English journalist, William Cobbett, is said to have popularized he term, telling a story of having used strong-smelling smoked fish to divert and distract hounds from chasing a rabbit.

The important questions long have had to do to do with the extent of Trump’s relations with powerful figures in Russian before his election as president; and with whether the FBI did a competent job of investigating those charges.

The herring in this case is the Durham investigation of various forms of 2016 campaign mischief, including (but not limited to) the so-called “Steele Dossier’’. The inquiry into Trump’s Russia connections was furthered (but not started) by persons associated with Hillary Clinton’s campaign. {Editor’s note: The political investigations of Trump’s ties with Russia started with anti-Trump Republicans.}

Trump’s claims that his 2020 defeat were the result of voter fraud have been authoritatively rejected. What, then, of his earlier fabrication? It has to so with the beginnings of his administration, not its end. The proposition that Clinton campaign dirty tricks triggered a tainted FBI investigation and hamstrung what otherwise might have been promising presidential beginning has been promoted for five years by Trump himself. The Mueller Report on Russian interference in the 2016 election was a “hoax,” a “witch-hunt’’ and a “deep-state conspiracy,” he has claimed.

Today, Trump’s charges are being kept on life-support in the mainstream press by a handful of columnists, most of them connected, one way or another, with the editorial page of The Wall Street Journal. Most prominent among them are Holman Jenkins, Kimberly Strassel and Bret Stephens, now writing for The New York Times.

Durham, a career government prosecutor with a strong record as a special investigator of government misconduct (the Whitey Bulger case, post 9/11 CIA torture) was named by Trump to be U.S. attorney for Connecticut in early 2018. A year later, Atty. Gen. William Barr assigned him to investigate the president’s claims that suspicions about his relations with Russia had been inspired by Democratic Party dirty tricks, fanned by left-wing media, and pursued by a complicit FBI. Last autumn, Barr named Durham a special prosecutor, to ensure that his term wouldn’t end with the Biden administration.

There is no argument that Durham has asked some penetrating questions. The “Steele Dossier,” with its unsubstantiated salacious claims, is now shredded, thanks mostly to the slovenly methods of the man who compiled it, former British intelligence agent Christopher Steele. Durham’s quest to discover the sources of information supplied to the FBI is continuing. The latest news of it was supplied last week, as usual, by Devlin Barrett, of The Washington Post. (Warning: it is an intricate matter.)

What Durham has not begun to demonstrate is that, as a duly-elected president, Donald Trump should have been above suspicion as he came into office. There was his long history of real estate and other business dealings with Russians. There was the appointment of lobbyist Paul Manafort as campaign chairman in June 2016; the secret beginning on July 31 of an FBI investigation of links between Russian officials and various Trump associates, dubbed Crossfire Hurricane; Manafort’s forced resignation in August; the appointment of former Defense Intelligence Agency Director Michael Flynn as National Security adviser and his forced resignation after 22 days; Trump’s demand for “loyalty” from FBI Director James Comey at a private dinner a week after his inauguration, and Comey’s abrupt dismissal four months later (which triggered Robert Mueller’s appointment as special counsel to the Justice Department): none of this has been shown to do Hillary Clinton’s campaign machinations.

The Steele Dossier did indeed embarrass the media to a limited extent – Mother Jones and Buzzfeed in particular – but it was President Trump’s own behavior, not dirty tricks, that disrupted his first months in office. Those columnists who exaggerate the significance of campaign tricks are good journalists. So why keep rattling on?

In the background is the 30-year obsession of the WSJ editorial page with Bill and Hillary Clinton. WSJ ed page coverage of the story of John Durham’s investigation reminds me of Blood and Ruins, The Last Imperial War 1931-1945 (forthcoming next April in the US), in which Oxford historian Richard Overy argues that World War II really began, not in 1939 or 1941, but with the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931. Keep sniffing around if you like, but what you smell is smoked herring.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

© 2021 DAVID WARSH

Before the water rose higher

“What Was” (oil on canvas), by Cotuit, Mass-based Julie Gifford, at Alpers Fine Art, Andover, Mass. She writes:

“I’m interested in celebrating the spirit of land, sea and sky and the resilience of the creatures who inhabit it. When painting, I’m working on an internal script…a bit of prose which reveals itself through marks on canvas – a personal conversation that comes from within and becomes clear only upon completion.’’

Cahoon Museum of American Art, in Cotuit

Todd McLeish: Weasels seem to be declining in New England and elsewhere in U.S.

The Long-Tailed Weasel seems to be the most common weasel in New England.

A Long-Tailed Weasel in winter coat

Via ecoRI News (ecori.org)

A national study of weasels from across much of the United States has revealed significant declines in all three species evaluated, which has a local biologist wondering about the status of the animals in Rhode Island.

The study by scientists in Georgia, North Carolina and New Mexico found an 87-94 percent decline in the number of least weasels, long-tailed weasels, and short-tailed weasels harvested annually by trappers over the past 60 years.

While a drop in the popularity of trapping and the low value of weasel pelts is partially to blame for the declining harvest, the researchers still detected a significant drop in the populations of all three species.

“Unless you maybe have chickens and you’re worried about a weasel eating your chickens, you probably don’t think about these species very often,” said Clemson University wildlife ecologist David Jachowski, who led the study. “Even the state agency biologists who are charged with tracking these animals really don’t have a good grasp on what is going on.”

The three weasel species are small nocturnal carnivores that feed primarily on mice, voles, shrews, and small birds, often by piercing their preys’ skull with their canine teeth. The weasels prefer dense brush and open woodland habitats, where they search for prey among stone walls, wood piles, and thickets. Because of their secretive nature and cryptic coloring, they are difficult to find and observe.

By assessing trapper data, museum collections, state statistics, a nationwide camera trapping effort, and observations reported on the internet portal iNaturalist, the scientists found the animals to be increasingly rare across most of their range.

“We have this alarming pattern across all these data sets of weasels being seen less and less,” Jachowski said. “They are most in decline at the southern edges of their ranges, especially the Southeast. Some areas like New York and the Canadian provinces can still have some dense pop ulations in localized areas.”

Jachowski noted weasel populations in southern New England are likely facing similar declines as the rest of the country. He believes, however, there is the potential for some areas of the Northeast to still have robust numbers of weasels, especially long-tailed weasels, which are considered the most common of the three species.

Charles Brown, a wildlife biologist at the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management, who contributed data to the national study, said in his 20 years of monitoring mammal populations in the Ocean State, the only one of the three weasel species he has found is the long-tailed weasel.

“I’ve had a few infrequent encounters with them over the years and seen a few dead ones on the road,” he said. “A mammal survey done in the 1950s and early ’60s documented two short-tailed weasels, and those are the only records I’ve found for the species.”

Least weasels are not found within 300 miles of Rhode Island.

Brown has contributed 19 or 20 long-tailed weasel specimens to the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University over the years from many mainland communities, including Little Compton, East Providence, Warwick, and South Kingstown. Weasels are not known to inhabit any of the Narragansett Bay islands.

“It’s hard to say what their status is here,” he said. “Trappers might bring in one or two a year, and some years none, and we don’t have any other indexes to monitor them because they’re cryptic and we rarely see them.”

Brown said a monitoring program could be developed for weasels in the state using track surveys and camera traps, but because the animals have little economic value and do not cause significant damage, they have not been a priority to study.

“In a perfect world, I’d certainly like to try to find a specimen of a short-tailed weasel to see if they’re still around here, but I have nothing to go on about them from a historic perspective,” he said.

Data from the University of Rhode Island is helping to provide a current perspective of the species’ distribution. URI scientists recently concluded a five-year study of bobcats and the first year of a study of fishers, each using 100 trail cameras scattered throughout the state. Among the 850,000 images collected so far are about 150 photos of long-tailed weasels.

According to Amy Mayer, who is coordinating the studies, the weasel images were collected at numerous locations around the state, suggesting the population does not appear to be concentrated in any particular area of Rhode Island.

It is uncertain what could be causing the national decline in weasel numbers, though Jachowski and Brown believe the increasing use of rodenticides, which kill many weasel prey species, could be one factor. A recent study of fishers collected from remote areas of New Hampshire found the presence of rodenticides in the tissues of many of the animals.

“How it’s getting into the food chain in these remote areas, we don’t know,” Brown said. “There was some discussion that a lot of people go up there to summer camps, and when they close the camp up for the season, they bomb it with rodenticides to keep the mice out. That’s just speculation, but it makes sense.”

The decline of weasels may also have to do with changes to available habitat, the scientists said. The maturing of forests and decline of agricultural land has caused a reduction in the early successional habitats the animals prefer. Brown also believes the recovery of hawk and owl populations, which compete with weasels for mice and voles and which may occasionally kill a weasel, could also be a factor.

Jachowski said the findings from his national study have led to the formation of what he is calling a “weasel working group” to share data and discuss how to monitor the animals around the country. Brown is among the state biologists and academic researchers who are members of the group.

“We’re hoping the public will become involved, too, by reporting their sightings to iNaturalist,” Jachowski said. “We need to see where they persist, and then we can tease out what habitats they’re still in, what regions, and then do our studies to figure out what kind of management may be needed.”

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish runs a wildlife blog.e

Scott Klinger: Trump’s postmaster general continues to wreak havoc as Christmas nears

The old post office in Augusta, Maine, a notable example of Romanesque architecture

Via OtherWords.org

HARPSWELL, Maine

Last year’s holiday season was not exactly a merry one for the U.S. Postal Service. In the lead-up to Christmas, overwhelmed postal workers had to leave gifts sitting in sorting facilities for weeks. They delivered just 38 percent of greeting cards and other nonlocal first-class mail on time.

What should we expect this year?

USPS leaders claim they are ready for the rush. But customers have reason to worry about slower — and more expensive — service.

The service is aiming to hire 40,000 seasonal workers for the holidays. But that’s 10,000 less than last year — and given broader pandemic staffing shortages, recruitment and retention for these demanding jobs will not be easy. While the e-commerce surge that strained the system last year has declined somewhat, postal workers are still delivering many more packages than before the crisis.

And COVID-19 is not the only reason for concern. In fact, the root causes of our country’s postal problems are inaction by Congress and misguided action by USPS leadership.

For more than a decade, Congress has failed to fix a policy mistake that requires the Postal Service to set aside money to prefund retiree health care more than 50 years in advance. This burden, which applies to no other federal agency or private corporation, accounts for 84 percent of USPS reported losses from 2007 to 2020. If Congress had made the same demand of America’s strongest businesses, many would be bankrupt.

A bill to repeal this pre-funding mandate and put USPS on a stronger financial footing enjoys strong bipartisan support. But House and Senate leaders have not brought up this bill, the Postal Reform Act, for a vote.

In the meantime, U.S. Postmaster General Louis DeJoy, a Trump campaign contributor, is using the agency’s artificially large losses to justify jacking up prices and slowing deliveries.

If you’re planning to send holiday cards a significant distance this season, say from Pittsburgh to Boise, the USPS delivery window is now five days instead of three. These reduced service standards affect about 40 percent of First Class mail.

As part of a 10-year plan, DeJoy is also slowing delivery by 1 to 2 days for about a third of First Class packages. These are small parcels often used to ship highly time-sensitive medications, as well as other lightweight e-commerce purchases.

A big cause of the slowdown: DeJoy’s plan to cut costs by shifting long-distance deliveries from planes to trucks. This is a rollback of the introduction of airmail more than 100 years ago — one of many postal innovations that strengthened the broader U.S. economy.

For worse service, we’ll have to pay more.

In August, USPS raised rates for First Class mail by 6.8 percent and for package services by 8.8 percent. A holiday surcharge will raise delivery costs by as much as $5 per package through December 26. In January, rates for popular flat-rate boxes and envelopes will increase by as much as $1.10.

Next up on DeJoy’s plan: reduced hours at some post offices and the closure of others.

USPS officials argue these draconian moves will boost profits. But even the regulator that oversees the agency has criticized the underlying financial analysis.

Instead, DeJoy’s 10-year plan will more likely drive customers away. That, in turn, will lead to fewer of the good postal jobs that have been a critical path to the middle class, particularly for Black families.

Unless Washington lawmakers lift the financial burden they imposed on USPS, DeJoy will be empowered to keep up his self-defeating cost-cutting spree.

Postal workers and their customers have struggled to overcome the extreme challenges of the pandemic. Now it’s time for Congress to deliver by passing the Postal Reform Act and urging USPS leaders to focus on innovations to better serve all Americans for generations to come

Scott Klinger, who lives in Harpswell, is senior equitable development specialist at Jobs With Justice.

On Ragged Island, Harpswell, Maine, circa 1920

An endless harvest

Spades take up leaves

No better than spoons,

And bags full of leaves

Are light as balloons.

I make a great noise

Of rustling all day

Like rabbit and deer

Running away.

But the mountains I raise

Elude my embrace,

Flowing over my arms

And into my face.

I may load and unload

Again and again

Till I fill the whole shed,

And what have I then?

Next to nothing for weight,

And since they grew duller

From contact with earth,

Next to nothing for color.

Next to nothing for use.

But a crop is a crop,

And who's to say where

The harvest shall stop?

“Gathering Leaves,’’ by Robert Frost (1874-1963)

Raking up the sun

“Dune Shadows: Hyannis, Cape Cod’ (archival pigment print), by Bobby Baker

© Bobby Baker Fine Art

Don Pesci: Beware Democrats' ‘government of force’

VERNON, Conn.

Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont has probably learned more than he has been willing to say from recent state and municipal elections

If one could stretch Lamont out on a comfortable couch and peek into his political psyche, one might find him sharing space with Virginia’s new governor-elect, Glenn Youngkin, and the bête noir of the progressive wing of the national Democratic Party, Sen. Joe Manchin, of West Virginia.

Manchin is something of a Democrat budget hawk, whose hectoring, residual moderates believe, is very much needed in a party that has adopted improvident spending as an operative political principle.

Singing from the balcony of the party’s once vibrant moderate center are =. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, and the lead choir boy, President Biden, all of whom have borrowed hymns from socialist Bernie Sanders's progressive song book.

Budget watchers generally agree that the redistributionist Democratic Party budget, as well as the ideological arc in the once moderate party, has been heavily influenced by Sanders’s eccentric socialistic notions. There are in political parties king makers and budget makers. Sanders and members of the so called "Squad" have become important leftist budget and policy makers in the Democratic Party.

Ideology, the fierce commitment to a political doctrine, is the iron bar in the politics of force. What, we may ask, is the opposite of the politics of force? Surely, few will disagree that its opposite is the still revolutionary notion that government derives its authority to govern from the consent rather than the conquest by power and force of the governed.

Asked shortly after the polls had closed in Virginia whether he thought “the sagging poll ratings of President Biden could affect next year’s elections for Congress and governors’ offices around the country,” Lamont first quipped that “he had spent time Tuesday night,” when election returns were rolling in, “watching the final game of the World Series,” according to a report in a Hartford paper.

Two days later, Lamont was less flippant. The shadow of the New Jersey race had fallen over many Democrats. In New Jersey, Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy won re-election by a breathtakingly small margin, according to Politico: Murphy 1,285,351, Jack Ciattarelli 1,219,906.

Lamont told a reporter, “I certainly feel like there’s a sense that the middle class is getting slammed, but I’ve felt that since I’ve been governor … I think that dysfunction in Washington, D.C., put a cloud on Democratic races…They did have a big tax increase in New Jersey, which I think got people’s attention. We’re in a very different place here in Connecticut. I’ve got to talk to Phil and see what else I can learn from that.”

During his first year in office, Biden, Pelosi and Schumer together have been the principal force leaders in their party. Both have threatened to eliminate the Electoral College in favor of the election of presidents by popular vote, a measure that would allow large population centers, mostly on the East and West coasts, to deprive small states and low-population-density areas of the country of an equitable voice in presidential selection. This measure, like the packing of the Supreme Court, would in the short run benefit a Democratic Party that values force above government action tempered by constitutional restraints. {Editor’s note: A constitutional amendment would be needed to eliminate the Electoral College.}

None of the force leaders in the Democratic Party have hesitated to use the power of government agencies to enhance their own political standing with the American public. The recently concluded elections are the first indication that the American public is, in both the pre- and post-COVID-19 epoch, generally opposed to a mode of governance that has succeeded elsewhere in the world only through the sustained application of the kind of persistent force that raises its horned head in every page of Machiavelli’s The Prince. Pelosi’s own daughter, intending to bestow a compliment, said of her mother, “She’ll cut your head off, and you won’t even know you’re bleeding,” a frighteningly accurate description of the politics of force.

Governments of force are the same everywhere – boringly vicious. Their shared characteristics are: the use of government agencies, unaccountable to the general public and not easily dismissed, to subvert the representative principle, traditional democratic government and the rule of law; the pitiless demonization of political opponents, an over reliance on propaganda and government imposed sanctions; a reliance on messaging, rather than practical and efficient policies, to capture the affections of the general public; and the transference of wealth and decision-making from the private marketplace to an overweening and seemingly omnipresent central government.

“Character,” said Thomas Paine, when the American experiment in republican government was yet in its infancy, “is better kept than recovered.”

If Lamont were a close student of history, rather than a millionaire whom fortune has blessed, he would understand why Biden’s approval ratings are abysmally low, 38 percent by at least one poll, understand what happened in in New Jersey, understand why Democrats are losing their grip on unaffiliated voters, as well as soccer moms, and why it is much easier to keep liberty, justice, constitutional government, the republic and a decentralizing power principle – the separation of the three branches of government – than it would be to restore the characteristics of the American experiment in freedom and representative government after the essential nature of the country had been deformed -- not reformed -- by leftists with knives in their brains.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

Llewellyn King: Nuclear power, a victim of an ignorant left-wing assault, urgently needs to be expanded to fight global warming

The Seabrook Nuclear Power Plant, in Seabrook, N.H.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

If the Biden administration genuinely wanted to get serious about weaning the electric-power sector from fossil fuels, it would get serious about nuclear — not just patting it on the head, as it is doing with the government equivalent of “There, there, baby.”

Nuclear was an early victim of the culture wars that started in the late 1960s, and it remains so to this day.

It is incredible that a source of power, a cutting-edge technology, should have been sidelined for more than 50 years because of fear, suspicion, ignorance and politics.

In the late 1960s, nuclear power became the target of an environmental and political left lash-up. It became part of the environmentalist catechism that nuclear was an evil source of power and must be expunged from the national list of options. The political left didn’t so much as embrace environmentalism as environmentalism embraced the left.

Some environmentalists have had an epiphany, such as the Union of Concerned Scientists, which was founded by Henry Kendall, an activist whom I knew well. We were friends who didn’t agree about nuclear. Now the Union of Concerned Scientists is pro-nuclear, but it was at the barricades against nuclear for decades.

It isn’t that the environmental movement doesn’t want to do the right thing. It does. But it has thought that it alone should decide what was right and good for the environment, and often it has been totally wrong.

The environmental movement turned the nation from nuclear to coal. In the 1970s and 1980s, environmental groups advocated for fluidized bed combustion coal plants. I remember them saying that coal eliminated the need for “dangerous nuclear.” I sat through innumerable meetings and had sparing friendships with such anti-nuclear activists as Ralph Nader and Amory Lovins.

All presidents have said they favor nuclear power, even Jimmy Carter, who was the most reluctant and did huge damage to the United States’ position as the world leader in nuclear energy and technology. Carter wouldn’t say he was opposed to nuclear, but he did talk about it as a last resort and stopped the plans to build a fast-breeder reactor. He also ended nuclear reprocessing, necessitating the disposal of whole nuclear cores, instead of capturing the mass of unburned fuel — thus creating a much larger waste disposal challenge, as well as the need to mine more uranium.

If you believe — and I do — what was said at the COP26 summit in Glasgow, Scotland, now is the time to fix the electric-power industry. It can be fixed by building up nuclear capacity so that electricity can be the go-to, clean fuel of the future. It could replace fossil fuels in everything from cement making to steel production to heating buildings. That potential, that future, is awesome and possible.

Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm should ask her national laboratories to make recommendations on a nuclear-power future, not to the detriment of wind and solar power, but embracing them.

Wind power is valuable. But depending on it is a little like having a trick knee: You never know when it is going to go out on you.

Europe has just learned that lesson the hard way. It is in the grip of a major energy crisis with electricity prices quadrupling and natural gas prices headed into the stratosphere as winter approaches. One of the causes of this crisis is that wind speeds through the summer fell to their lowest recorded levels in 60 years, with a total wind drought in the normally gale-wracked North Sea.

We won’t get to a carbon-free future unless we have a robust, committed plan to deploy state-of-the-art nuclear plants across the country. We built them in the 1960s and into the 1970s – 100 of them.

Granholm needs to declare a purpose and to pick the proven winner. It is nuclear, and it has been gravely wounded in the culture wars. She needs to rescue it – with word and deed.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Old cheap thrills for kids

Bayberries

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

With staring at screens taking up much of the waking hours of young people, how many still engage in the seasonal activities we used to enjoy in New England? In my family and those of our neighbors the seasonal cycles included smelt fishing (fried smelt are delicious!) in the early fall and making bayberry candles later in the fall.

You’d strip as many bayberries as you could off the bushes (of which we had many) and boil ‘em in water, in which the wax would rise to the surface, which we then skimmed off. Cheap and aromatic thrills, though it was a lot of time for only a little wax. Five pounds of berries could yield only about a pound of wax.

Because of this small, and from season to season, unpredictable yield, these candles were only for special occasions or as gifts. Pre-moneyed small children would happily give them as Christmas presents.

Indoor sport

Collection of basketball players, by Walker Hancock (1901-1998), 1960s, bronze. in the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass.

Here’s James Naismith, who invented basketball in 1891 at the International YMCA Training School, in Springfield, Mass.

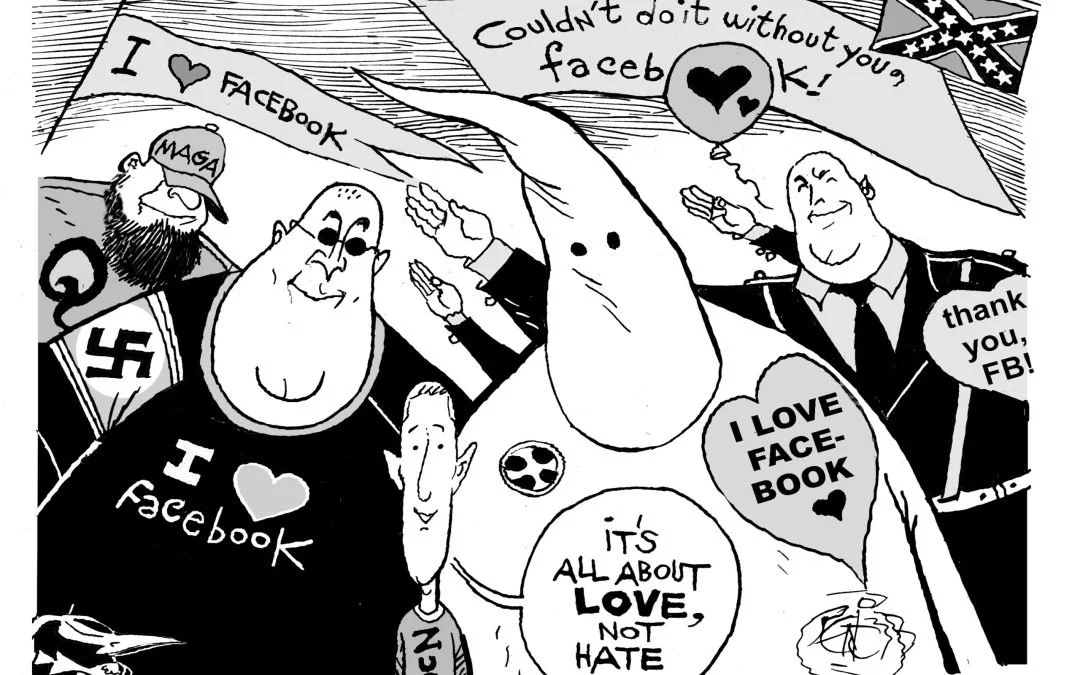

Jim Hightower: Because they ARE far-right-wing hacks

From OtherWords.org

Ralph Waldo Emerson once told about a guest who came to dinner and spent the entire evening prattling about his own integrity: “The louder he talked of his honor,” Emerson wrote: “the faster we counted our spoons.”

Today, America has not one, but six guests in our national home babbling about their integrity.

They are the six extremist Republican judges who now control our Supreme Court, and it’s a bit unsettling to hear them go on and on, almost frantically pleading with us to believe in their judicial impartiality.

For example, the court’s newest member, Amy Coney Barrett, suddenly blurted out at a public forum in September that “this court is not comprised of a bunch of partisan hacks.”

Better count our spoons! In fact, each of the six were installed on the court by right-wing Republicans specifically because they had proven to be devout partisan hacks.

Interestingly, Barrett made her unprompted and strained assertion of judicial integrity at the McConnell Center — named for Mitch McConnell, the rabidly partisan GOP Senate leader who pulled a fast one last year, rushing Barrett onto the bench on a party-line vote just before Republicans lost control of the Senate and White House.

Indeed, old Mitch himself introduced Barrett at the forum where she gave her “we-are-not-partisan-hacks” speech. He grinned proudly at the pure hackery of his partisan protégé.

Another hard-core partisan on the court, Sam Alito, whined in October that critics accuse the court’s GOP majority of being “a dangerous cabal that resorts to sneaky and improper methods to get its way.”

Well golly, Sam, yes, we do think that. Because again and again, the court’s conservatives have pulled the court down into the mire of crass Republican politics.

They’ve corrupted the system and jiggered the law to decree that corporate campaign cash is “free speech,” that the state can take over women’s bodies, and that the Republican Party can unilaterally shut millions of voters out of America’s voting booths.

If you don’t want to be considered political hacks, stop being political hacks.

OtherWords columnist Jim Hightower is a radio commentator, writer and public speaker.

'Shortcuts when they pay'

—Photo by Malene Thyssen

“{Lee Totman} is more than just a good farmer….He doesn’t waste moves. He is always set up for the job he needs to do. He plans only as much as his equipment and help permit. He takes shortcuts where they pay and lavishes attention where that pays better. His manure truck is an old unregistered jalopy; his equipment shed is made of old telephone poles and sheer tin.’’

-- Mark Kramer, in Three Farms (1980). Mr. Totman was a dairy farmer in Conway, Mass.

— Photo by DrunkDriver

Gathering around light

“Right Whale Lantern”, by Vermont-based artist and scientist Kristian Brevik in the group exhibition “Light Show.’’ at Dedee Shattuck Gallery, Westport, Mass. through Dec. 21. (North Atlantic Right Whales are in danger of extinction.)

The gallery (which is also a diversified arts center), explains:

“Light Show” is a multimedia group show with work by Adam Frelin, Kristian Brevik, Linda Schmidt, Megan Mosholder and Steven Pestana. Each of these artists utilizes light—either artificial or natural light—as a key component of their work. This exhibition, beginning after Daylight Savings Time and leading up to the winter solstice, celebrates how we create light in darkness, how we gather together and around light sources as the ever-fascinating visual medium of people across time.’’

In a rural, or at least exurban, part of Westport, which has become increasingly attractive to affluent people from Greater New York City and Greater Boston for weekend and summer places. They’re drawn by its countryside, which includes farms and vineyards, its relatively mild climate and Buzzards Bay, which is among the warmest bodies of water in New England in the summer.

Chris Powell: Out-of-state marching band plays dirge for Connecticut

Ocean Avenue in West Haven

MANCHESTER, Conn.

West Haven may be providing the perfect metaphor for government and politics in Connecticut.

The small city has been suffering from financial excess so long that since 2017 it has been operating under the supervision of the state's Municipal Accountability Review Board. Because of a federal criminal indictment announced a few weeks ago, the city discovered that it had been looted of $636,000 of its emergency federal epidemic assistance money, allegedly embezzled by its state representative, who had been double-dipping as a salaried assistant to the City Council.

Nevertheless, Mayor Nancy Rossi's defense against the scandal right under her nose -- her obliviousness -- was accepted by the voters, who narrowly re-elected her Nov. 2.

Then enterprising journalism by the Connecticut Mirror found that apart from being embezzled, some of West Haven's emergency federal money was also spent to hire a marching band for the city's Memorial Day parade, to buy Christmas decorations, and to buy services from a City Council member's company. The New Haven Register already had reported that some of the federal money was spent to pay town officials for "compensatory time."

While the state accountability board had placed an agent at City Hall, he missed the fraud as well. So maybe the board needs to be investigated as much as city government does.

In another state such a scandal might prompt the legislature to hold hearings to investigate. But Connecticut's state legislators have left the corruption issue to federal prosecutors, just as the state's own prosecutors have.

Nevertheless, an estimated $4 billion more in federal money will be sent to Connecticut for highway and bridge improvements under the "infrastructure" legislation recently approved by Congress. Connecticut Rep. Rosa L. DeLauro, chairwoman of the House Appropriations Committee, says the money is all about "jobs, jobs, jobs."

But thousands of jobs, including many highly paid jobs in manufacturing, are already open in the state and can't be filled. Indeed, that marching band for the West Haven parade had to be imported from New York.

At least the federal infrastructure money may demolish the long-running argument for reimposing tolls on Connecticut highways. The money also may demolish the argument for joining what is called the Transportation Climate Initiative, an increase in the wholesale tax on gasoline in the name of raising money for less-polluting modes of transportation.

And if, as many members of Congress hope, their next spending bill includes a national program of paid family and medical leave, Connecticut will be able to repeal its own recently enacted program, for which the state income tax was raised by a half percent.

Federal money is considered better than state money because it can be created without taxation and thus can seem free -- as long as people don't start wondering why their fast-food hamburger and fries now cost more than $10 and gasoline more than $3 per gallon.

Whatever happens, government in Connecticut already has far more emergency federal money than it knows what to do with. That's why some has been spent on a marching band.

Tweed New Haven Airport

Gov. Ned Lamont and other dignitaries gathered Nov. 3 to celebrate the revival of Tweed New Haven Airport, which is the new East Coast hub for startup Avelo Airlines. There are great plans for Tweed -- lengthening its runway to handle larger jetliners and construction of a terminal accommodating more traffic.

But Avelo is not what Connecticut really needs at Tweed. For the airline plans only flights to six cities in Florida, to which thousands of state residents relocate in the winter, often for tax purposes, the Sunshine State not taxing personal income.

Instead of more ways of sending people to Florida, Tweed and the New Haven area need flights to hub airports, such as the American Airlines flights to Philadelphia and Charlotte that Tweed had until the virus epidemic devastated the travel industry.

If Tweed could recover those flights and gain flights to Chicago or Dallas, the airport would put New Haven on the national map for business development. Suddenly more people might have reason to come to Connecticut than to leave it.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

David Warsh: Perhaps we're in the Third Reconstruction

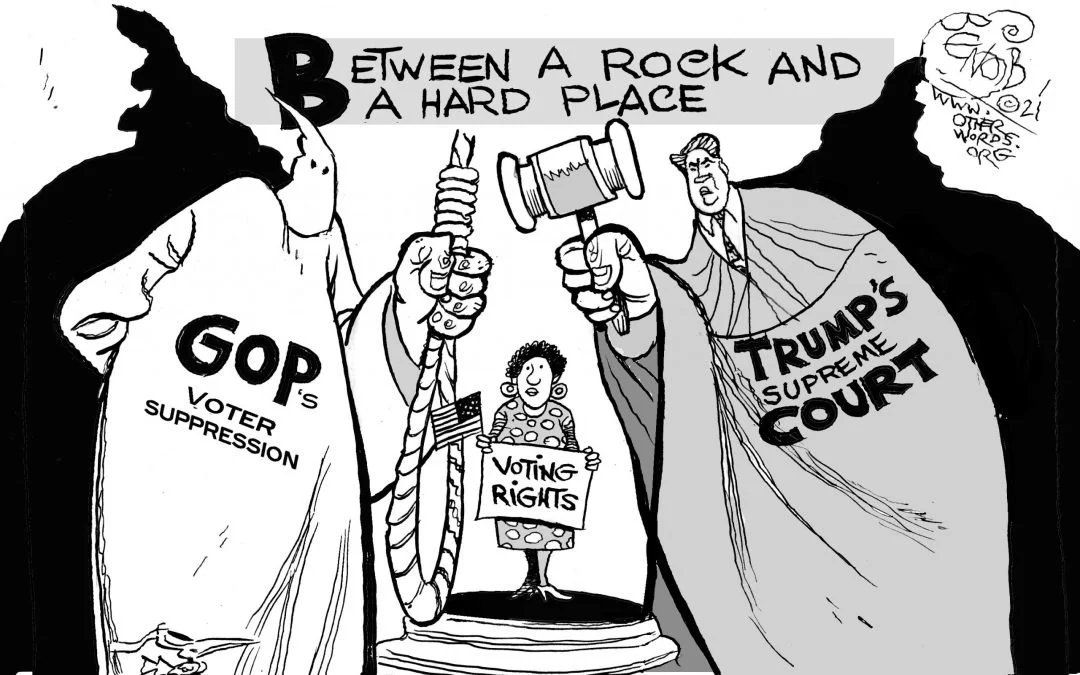

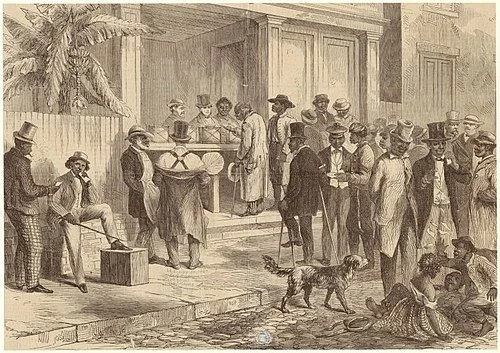

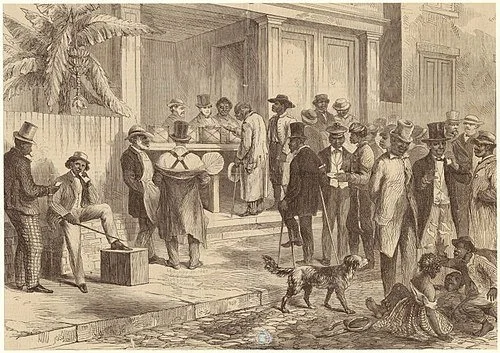

Former slaves voting in New Orleans in 1867. After Reconstruction ended, in 1977, most Black people in much of the South lost the right to vote and didn’t regain it until the 1960s.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

“Reconstruction” (1865–1877), as high school students encounter it, is the period of a dozen years following the American Civil War. Emancipation and abolition were carried through; attempts were made to redress the inequities of slavery; and problems were resolved involving the full re-admission to the Union of the 11 states that had seceded.

The latter measures were more successful than the former, but the process had a beginning and an end. After the back-room deals that followed the disputed election of 1876, the political system settled in a new equilibrium.

I’ve become intrigued by the possibility that one reconstruction wasn’t enough. Perhaps the American republic must periodically renegotiate the terms of the agreement that its founders reached in the summer of 1787 – the so-called “miracle in Philadelphia,” in which the Constitution of the United States was agreed upon, with all its striking imperfections.

Is it possible that we are now embroiled in a third such reconstruction?

The drama of Reconstruction is well documented and thoroughly understood. It started with Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, continued with his Second Inaugural address, the surrender of the Confederate Army at Appomattox Courthouse; emerged from the political battles Andrew Johnson’s administration and the two terms of President U.S. Grant; and climaxed with the passage of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution – the “Reconstruction Amendments.” It ended with the disputed election of 1876, when Southern senators supported the election of Rutherford B. Hayes, a Republican, in exchange for a promise to formally end Reconstruction and Federal occupation he following year.

The shameful truce that followed came to be known as the Jim Crow era. It last 75 years. The subjugation of African-Americans and depredations of the Ku Klux Klan were eclipsed by the maudlin drama of reconciliation among of white veterans – a story brilliantly related in Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory, by David Blight, of Yale University. For an up-to-date account, see The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution, by Eric Foner, of Columbia University.

The second reconstruction, if that is what it was, was presaged in 1942 by Swedish economist Gunnar Myrdal’s book, An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and American Democracy, commissioned by the Carnegie Corporation. The political movement commenced in 1948 with the desegregation of the U.S. armed forces. The civil rights movement lasted from Rosa Parks’s arrest, in 1955, through the March on Washington, in 1963, at which Martin Luther King Jr. made delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech, and culminated in the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Repression was far less violent than on the way to the Jim Crow era. There were murders in the civil rights era, but mostly they made newspaper front pages.

And while the second reconstruction entered on race, many other barriers were breached in those rears as well: ethnicity, gender and sexual preference. In Roe v Wade the Supreme Court established a constitutional right to abortion a decade after the invention of the Pill made pregnancy a fundamentally deliberate decision.

How do reconstructions end? In the aftermath of decisive elections, it would seem – in the case of the second reconstruction, with the 1968 election of Richard Nixon, based on a Southern strategy devised originally by Barry Goldwater. Nixon was in many ways the last in a line of liberal presidents who followed Franklin Roosevelt. He had promised to “end the {Vietnam} war” the war and he did. An armistice of sorts – Norman Lear’s All in the Family television sit-com – preceded his Watergate-inspired resignation. Peace lasted until the election of President Barack Obama.

So what can be said about this third reconstruction, if that is what it is? Certainly it is still more diffuse – not just Black Lives Matter, but #MeToo, transgender rights, immigration policy and climate change, all of it aggravated by the election of Donald Trump. This latest reconstruction is often described as a culture war, by those who have never seen an armed conflict. How might this episode end? In the usual way, with a decisive election. Armistice may takes longer to achieve.

For a slightly different view of the history, see Bret Stephens’s Why Wokeness Will Fail. We journalists are free to voice opinions, but we must ultimately leave these questions to political leaders, legal scholars, philosophers, historians and the passage of time. I was heartened, though, at the thought expressed by economic philosopher John Roemer, of Yale University, who knows much more than I do about these matters, when he wrote the other day to say “I think the formulation of the first, second, third…. Reconstructions is incisive. It reminds me of the way we measure the lifetime of a radioactive mineral. We celebrate its half-life, three-quarters life, etc….. but the radioactivity never completely disappears. Racism, like radioactivity, dissipates over time but never vanishes.”

David Warsh is a veteran columnist and an economic historian He’s proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

‘I’m not all gray’

Witch hazel can bloom in November.

— Photo by Keichwa

I come, a sad November day,

Gray clad from foot to head;

A few late leaves of yellow birch,

A few of maple red.

And, should you look, you might descry

Some wee ferns, hiding low,

Or late Fall dandelions shy,

Where cold winds cannot blow.

And then, you see, I'm not all gray;

A little golden light

Shines on a sad November day,

A promise for the night.

For though gray-clad, in soft gray mist,

Floating on gray-cloud wing,

I know that I the way prepare

For brightest days of Spring.

And though witch-hazel's golden flowers

Are all the blooms I know,

They promise—so do I—the hours

When sweetest Mayflowers grow.

— “November Day,’’ by Mary B.C. Slade (1826-1882), a poet and hymnist who was born in Somerset, Mass., and spent most of her life in Fall River.

Broad Cove, an inlet of the Taunton River, is at the northern end of Somerset.

Amazon to hire 1,500 workers in Mass. to deal with holiday crush

“Battle of the Amazons (1618), ‘‘by Peter Paul Rubens

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

“Amazon recently announced that it plans to hire 1,500 seasonal workers in Massachusetts to help meet the holiday demands. This is a part of an effort to hire 150,000 seasonal workers around the country.

“Caitlyn McLaughlin, a spokesperson for Amazon, confirmed the announcement while reiterating that the supply-chain challenges that are being experienced will affect consumers around the world. ‘Everyone at Amazon is working to anticipate and prepare for various scenarios to ensure positive delivery experiences this holiday season, for instance, by launching promotions to encourage earlier shopping,’ said McLaughlin.

“Amazon is one of Massachusetts five largest employers, according to the Business Journal, and covers both the tech industry and the retail industry. Over this past summer the company had 20,000 positions available in the state for both part time and full-time positions in both industries.’’