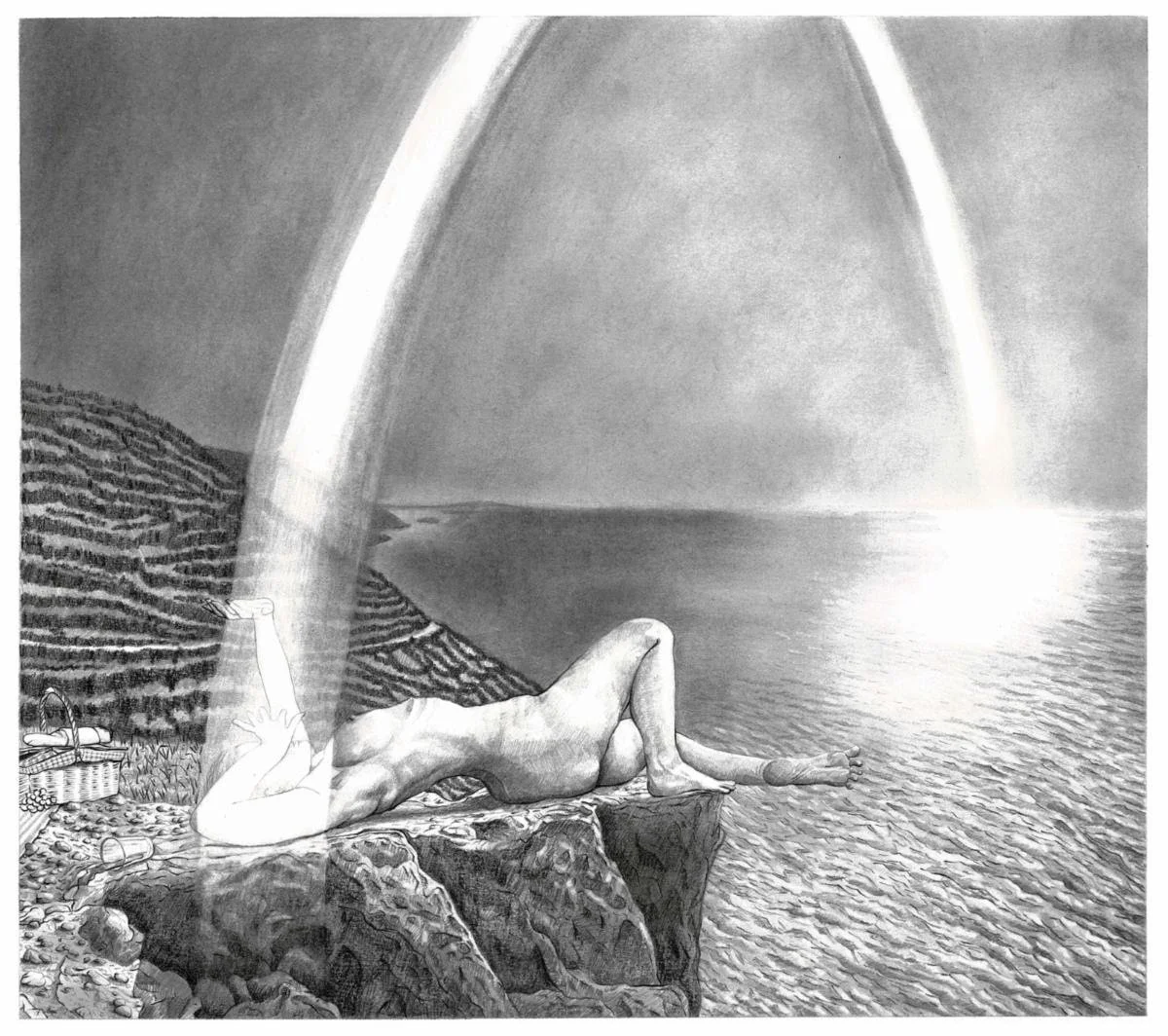

Just me and my landscape

“Light” (graphite and charcoal on paper), by New York-based Catalina Viejo Lopez de Roda, in her show “Self Care’’, at HallSpace Contemporary Art Gallery, in Boston’s Dorchester section, starting Dec. 11. {Editor’s note: This reminds me of the work of Rockwell Kent.}

The gallery says: "Dealing with a persistent virus has instigated a new direction in Viejo’s work, with the central theme being Self Care. A single woman lives in isolation in each of her drawings, paintings and animations. These women inhabit wild environments and have developed a symbiotic relationship with the landscape."

‘It’s not intellectual’

Rock of Ages granite quarry in Graniteville, Vt.

]

“Never confuse faith, or belief — of any kind — with something even remotely intellectual.’’

— From A Prayer for Owen Meany, a novel by John Irving (born 1942)

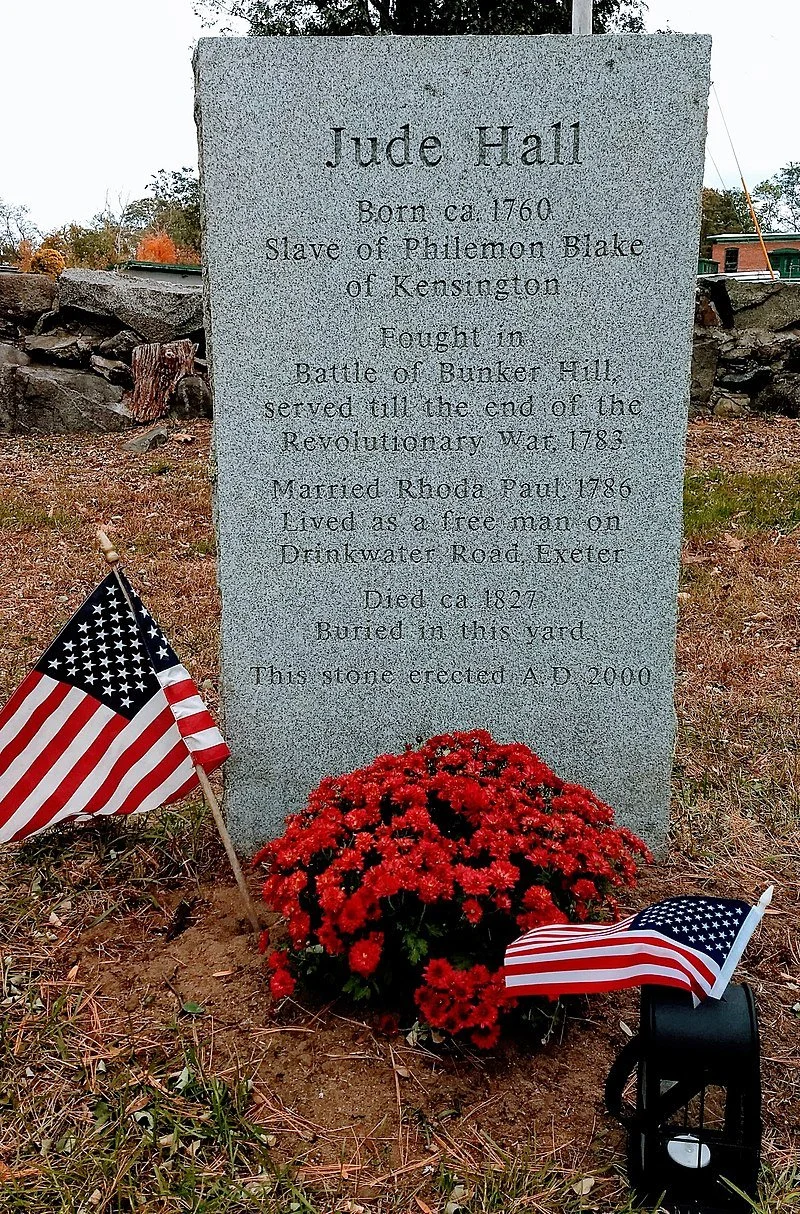

The plot centers around John Wheelwright and Owen Meany, who live in the fictional town of Gravesend, N.H. (based on Irving’s hometown of Exeter, N.H.). As boys they are close friends, although John comes from an old rich family — as the illegitimate son of Tabitha Wheelwright — and Owen is the only child of a working-class granite quarryman. John's earliest memories of Owen involve lifting him up in the air, easy because of his permanently small stature, to make him speak. And an underdeveloped larynx causes Owen to speak in a high-pitched voice. During his life, Owen comes to believe that he is "God's instrument".

Jude Hall granite memorial stone in Exeter, N.H.

A still, very New England place for reflection, not feasting

On Thanksgiving: In Jaffrey Center, N.H., with Mt. Monadnock in the background. The celebrated novelist Willa Cather is buried in Jaffrey’s Old Burying Ground.

— Photo by William Morgan

Chris Powell: Car thefts are the least of it in juvenile-justice scandal; Yale saves New Haven

Ford Explorer with broken window after it was stolen

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Democrats in Connecticut insist that there is no crime wave in the state and that concerns about crime are Republican contrivances. But it's nice that the state's minority party is pressing any issues at all, and Connecticut lately has had some criminal atrocities that really should be learned from, especially some involving juveniles.

One of those atrocities unfolded last week in Manchester, when a 14-year-old boy was charged with the rape and murder of a 13-year-old girl last June. News reports about the arrest discovered that state law prohibits the boy from being tried in open court and, if he is convicted, will prohibit him from being sentenced to anything more severe than 2½ years of probation, regardless of whether he is a predatory maniac or a great kid who made what the social workers may get away with calling a "mistake."

Whatever the boy is, the secrecy of court for murder defendants under 15 years old will prevent the public from ever finding out.

Few teenagers read newspapers or pay attention to broadcast news, but they do talk to each other and so news can spread among them all the same. Thanks to the Manchester case they now may perceive that in Connecticut they are pretty much free to rape and murder until they turn 15, and they may perceive that their exemption from criminal responsibility for car thefts, which they already well understand and that recently has become controversial, is actually the least of the scandal of juvenile justice here.

A spokeswoman for the social work school of thought, Illiana Pujols, of the Connecticut Justice Alliance, says the state's adult-justice system isn't made to serve children. But in its glorious secrecy, unaccountability and exemption of young offenders from responsibility even for atrocities, is the state's juvenile-justice system made to serve the public?

xxx

Yale University, whose ownership of so much property in New Haven takes much of it off the city's property-tax rolls, has a new six-year deal with the city. The university will increase its annual voluntary payment to the city from the current $13.2 million to $23 million, leading to total payments of more than $135 million by the arrangement's conclusion.

That kind of money could cover much of the city's underfunding of its pension programs and pay lots of raises, though whether it does much for the city itself must remain to be seen.

Mayor Justin Elicker and City Council members are thrilled by the deal, since the university, as a nonprofit corporation, isn't legally required to pay taxes on its noncommercial property. But the deal really isn't so generous.

For Yale already was suffering an embarrassment of riches, heightened by the recent stock market boom, which has boosted the university's endowment to $42 billion. The endowment has been managed extraordinarily well, so well that the joke is that Yale is actually a hedge fund disguised as a university. Yale is so wealthy that, as National Review noted the other day, it can afford to have more employees (nearly 17,000) than students (about 12,000).

But then the university's work is not just to teach but to be constantly striking politically correct poses to appease the political left that dominates it. Those poses now will be facilitated by a new city undertaking called the Center for Inclusive Growth, to which Yale will contribute $5 million over the next six years. The center may provide patronage jobs for growing still more political correctness in New Haven.

xxx

U.S. Education Secretary Miguel Cardona, briefly Connecticut's education commissioner, boasted last week of another big round of student0loan forgiveness -- $2 billion for 33,000 borrowers -- through the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program, for which teachers and employees of nonprofits are eligible.

Some of the debtors are indeed hard-pressed but as with most student-loan debt the borrowers are not the biggest beneficiaries of loan forgiveness. Student-loan debt becomes burdensome when the education for which the debt was incurred cannot qualify the borrower for a job that pays enough both to support him and repay the debt.

That is, the real beneficiaries of student loans are employees of higher education, which is overvalued and yet made still more expensive by those loans.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

‘Time nearing an end’

“Mantle” (oil and gold leaf on panel), by western Massachusetts-based Jeff Strauder, in his show “The Reckoning,’’ at the Grubbs Gallery at the Williston Northampton School, Easthampton, Mass., Dec. 5 to Jan. 5.

Mr. Strauder says "The Reckoning’’is a continuation of my preceding Pilgrim series, with an allegorical cosmology of my own design. Recurrent characters from that series appear again here, with the rising waters now an urgent threat. There is a sensation that time is nearing an end. The owl, a central new presence flanked by subservient beings, now presides over this world."

Williston Northampton School is a private, co-educational, day and boarding college-preparatory school established in 1841.

View of Mt. Tom from downtown Easthampton, in the Connecticut Valley.

Llewellyn King: Today’s lessons from the 1970’s energy crises

During the 1973-74 part of the 1970’s oil crisis.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I’ve been here before. I’ve heard this din at another time. I’m writing about the cacophony of opinions about global warming and climate change.

In the winter of 1973, the Arab oil embargo unleashed a global energy crisis. Times were grim. The predictions were grimmer: We’d never again lead the lives we had led -- energy shortage would be the permanent lot of the world.

The Economist said the Saudi Arabian oil minister, Sheik Ahmad Zaki Yamani, was the most important man in the world. It was right: Saudi Arabia sat on the world’s largest proven oil reserves.

Then as now, everyone had an answer. The 1974 World Energy Congress in Detroit, organized by the U.S. Energy Association, and addressed by President Gerald Ford, was the equivalent in its day to COP26, the UN Climate Change Conference which has just concluded in Glasgow, Scotland.

Everyone had an answer, instant expertise flowered. The Aspen Institute, at one of its meetings, held in Maryland instead of Colorado to save energy, contemplated how the United States would survive with a negative growth rate of 23 percent. Civilization, as we had known it, was going to fail. Sound familiar?

The finger-pointing was on an industrial scale: Motor City was to blame and the oil companies were to blame; they had misled us. The government was to blame in every way.

Conspiracy theories abounded. Ralph Nader told me that there was plenty of energy, and the oil companies knew where it was. Many believed that there were phantom tankers offshore, waiting for the price to rise.

Across America, there were lines at gasoline stations. London was on a three-day work week with candles and lanterns in shops.

In February 1973, I had started what became The Energy Daily and was in the thick of it: the madness, the panic -- and the solutions.

What we were faced with back then was what appeared to be a limited resource base that the world was burning up at a frightening rate. Oil would run out and natural gas, we were told, was already a depleted resource. Finished.

The energy crisis was real, but so was the nonsense -- limitless, in fact.

It took two decades, but economic incentive in the form of new oil drilling, especially in the southern hemisphere, good policy, like deregulating natural gas, and technology, much of it coming from the national laboratories, unleashed an era of plenty. The big breakthrough was horizontal drilling which led to fracking and abundance.

I suspect if we can get it right, a similar combination of good economics, sound policy, and technology will deliver us and the world from the impending climate disaster.

The beginning isn’t auspicious, but neither was it back in the energy crisis. The Department of Energy is going through what I think of as scattering fairy dust on every supplicant who says he or she can help. On Nov. 1, DOE issued a press release which pretty well explains fairy dusting: a little money to a lot of entities, from great industrial companies to universities. Never enough money to really do anything, but enough to keep the beavers beavering.

That isn’t the way out.

The way out, based on what we have on the drawing board today, is for the government to get behind a few options. These are storage, which would make wind and solar more useful; capture and storage of carbon released during combustion; and a robust turn to nuclear power.

All this would come together efficiently and quickly with a no-exceptions carbon tax. Republicans will diss this tax, but it is the equitable thing to do.

Nuclear power deserves a caveat. It is unique in its relation to the government, which should acknowledge this and act accordingly.

The government is responsible for nuclear safety, nonproliferation, and waste disposal. It might as well have the vendors build a series of reactors at government sites, sell the power to the electric utilities, and eventually transfer plant ownership to them.

The government has some things that it alone is able to do. Reviving nuclear power is one.

The energy crisis was solved because it had to be solved. The climate- change crisis, too, must be solved.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Cocktail party cacophony and claustrophobia in the latest version of The Ritz

The Newbury Hotel, overlooking the Boston Public Garden. The original 1927 wing is in the middle, the 1981 wing is on the right.

“The cocktail party effect is the phenomenon of the brain's ability to focus one's auditory attention on a particular stimulus while filtering out a range of other stimuli, such as when a partygoer can focus on a single conversation in a noisy room. Listeners have the ability to both segregate different stimuli into different streams, and subsequently decide which streams are most pertinent to them.’’

— Wikipedia

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I spent a recent evening at the Newbury Hotel (the original part of which opened in 1927), the swanky establishment in Boston’s Back Bay that some of us still call The Ritz-Carlton or just The Ritz. I thought that the evening, to which I was invited by a couple of Boston friends (thank God I wasn’t charged for it) would include a tour of the hotel, but in fact it was mostly a pleasant if noisy cocktail party in the fancy Italian fashion store in the hotel called Zegna, part of the Milan-based company of that name. Zegna makes very well-made stuff that few can afford.

Drinks were followed by dinner, with many small plates of (I think) northern Italian cuisine, in the rooftop restaurant called Contessa. The joint has spectacular views of the increasingly Manhattanized Downtown Boston skyline. The often clear and windy atmosphere of late fall and winter provides the year’s most spectacular nightime views of Boston and New York.

In Contessa, a hip great-grandson of the company founder promoted the company as being very “green,’’ touting among other things its spectacular nature preserve in the Piedmont region of northern Italy. When it comes to promotion, it’s hard to beat wrapping yourself in green, especially if you’re running a high-end company. Rich people like to consider themselves environmentalists, especially when it comes to protecting land from development near their suburban or rural estates!

I had almost forgotten how noisy such events can be, with the chattering getting louder and louder as second and third drinks were consumed. Lots of quick, superficial friendliness even as some party goers (social X-rays?) relentlessly sought out the most “important’’ people while trying to politely detach themselves from those they feared might be nonentities or just boring. Tom Wolfe would have enjoyed it.

“Who are these people, and what do they want?’’ I kept asking myself, before skulking off to a corner and glancing at a magazine (not Vogue) for a quiet moment.

The Newbury, overlooking the beautiful Public Garden, had quite a colorful reputation as the Ritz-Carlton, both as place for Proper Bostonians to celebrate special events and for the glitz that came from it being for decades a popular place for Hollywood and Broadway celebrities to stay (and sometimes be outrageous in).

It had its own ways.

There was the sign that said “not an accredited egress”’ over one of the doors in the lobby and a strict dress code. More than half a century ago, soon after I landed a job as a reporter and writer at the now-long-dead Boston Herald Traveler, and feeling flush with my $175-a-week salary, I took a girl for a drink in the famous (especially for celebrated writers) ground floor bar of the hotel, whose windows looked out on the Public Garden, a view that at night curiously made it seem that the drinkers were in a bluish underwater chamber.

We ordered our drinks and enjoyed them and the salted peanuts, probably from S.S. Pierce, that purveyor of food, some of it exotic – rattlesnake meat! -- to affluent New Englanders, especially WASPs. But then, our waiter bent down and murmured in my ear: “I’m sorry, Sir. But this will have to be the last drink. The lady is not properly attired.’’ The problem was that she was wearing pants and not a dress or a skirt. But of course back then, people could smoke away to their lungs’ discontent in bars. Some things were a lot looser then.

Years before that, when someone took me as a kid to the grand and very formal dining room, I was impressed that they served unsalted butter, which seemed very exotic to my untrained palate.

Ah, old Boston….

17th Century marketing

“The First Thanksgiving at Plymouth”, by Jennie Augusta Brownscombe (1914), in Pilgrim Hall Museum, Plymouth, Mass.

“Loving Cousin,

“At our arrival {from England} at New Plymouth, in New England, we found all our friends and planters in good health, though they were left sick and weak, with very small means; the Indians round about us peaceable and friendly; the country very pleasant and temperate, yielding naturally, of itself, great store of fruits, as vines of divers sorts, in great abundance. There is likewise walnuts, chestnuts, small nuts and plums, with much variety of flowers, roots and herbs, no less pleasant than wholesome and profitable. No place hath more gooseberries and strawberries, nor better. Timber of all sorts you have in England doth cover the land, that affords beasts of divers sorts, and great flocks of turkeys, quails, pigeons and partridges; many great lakes abounding with fish, fowl, beavers, and otters. The sea affords us great plenty of all excellent sorts of sea-fish, as the rivers and isles doth variety of wild fowl of most useful sorts. Mines we find, to our thinking; but neither the goodness nor quality we know. Better grain cannot be than the Indian corn, if we will plant it upon as good ground as a man need desire. We are all freeholders; the rent-day doth not trouble us; and all those good blessings we have, of which and what we list in their seasons for taking. Our company are, for the most part, very religious, honest people; the word of God sincerely taught us ever Sabbath; so that I know not any thing a contented mind can here want. I desire your friendly care to send my wife and children to me, where I wish all the friends I have in England; and so I rest.’’

“Your loving kinsman,

William Hilton”

The autumn of 1621 is supposed to have been when “The First Thanksgiving’’ took place— a cooperative affair between the Calvinist Pilgrims who had landed at what they named Plymouth the year before and some Wampanoags, those who has survived the epidemics of disease brought by English sailors and traders in Maine after 1600. These epidemics had killed most of the Native Americans in eastern New England before the Pilgrims arrived.

Don Pesci: ‘Shrouded in silence’

The riderless (caparisoned) horse named "Black Jack" during the departure ceremony as President Kennedy’s body was taken from the U.S., Capitol.

VERNON, Conn.

I had been playing basketball and decided, possibly for the second time in my first year as a student at Western Connecticut State College, to take a shower. Most often I showered at Mrs. Gallagher’s, about three city blocks from the college, where I had been boarding with a roommate, Edward Kennedy, a red-headed Irish pool shark.

Mrs. Gallagher was our sometimes eccentric landlady whose features suggested that she was a stunner as a young lady. She liked Kennedy’s red hair. And he, who could easily wind people around his pinky, joined Mrs. Gallagher for rum toddy once a week before bedtime.

The sky, as I remember it, was overcast, the weather around 38 degrees. The November wind was gentle. Girls were bent over a red convertible, its top down, weeping over the blare of a radio.

“What’s happened?” I asked as I passed them.

“Someone killed Kennedy,” one of the girls said.

Almost whispering to myself, I muttered, “Who would want to kill Ed Kennedy?’

President Kennedy was assassinated on Nov. 22, 1963, the Friday before Thanksgiving that year. Four of us, two close friends and a student I did not know well, left the day after the assassination for Washington, D.C., to pay our respects to the fallen president. We thumbed our way, bearing a large handwritten sign: “Washington DC – Kennedy funeral.”

We made the trek in three rides, astounding I thought at the time, but then our sign was an emotional passport. The assassination had scrambled everyone’s brains and hearts. And on this day, the wounded heart of the nation lay open, dissolving all the usual political oppositional chatter.

Our last chauffeurs were two young men, both taciturn Southerners who were in need of gasoline money to make their way home.

“We don’t have much, but we can give you what we can spare.”

We gave the two $10 and were let off late at night at Union Station, a short walk from the Capitol. All four of us fell asleep on the hard benches.

Early in the morning, I felt the soft tap of a baton on the sole of my shoe, and a gentle voice peeled the sleep from my eyes.

“Time to get up boys and be about your business,” the police officer said.

Even early in the morning, the streets were lined, number crunchers later said, with upwards of a million people, some having waited patiently – silently – for 10 hours and more.

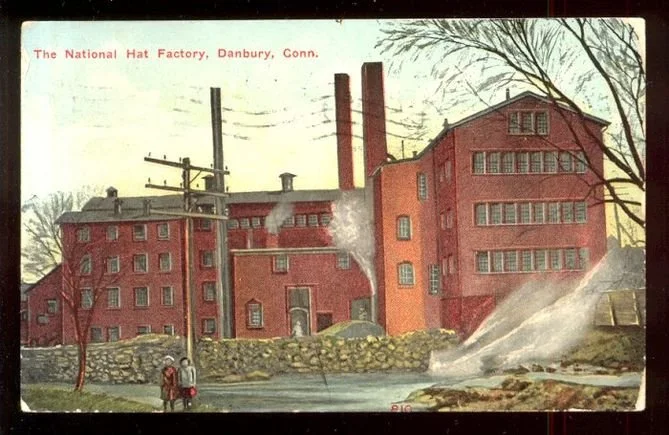

The silence suited me. During my four years in Danbury, unable to shake off a sometimes debilitating shyness, I had found comfort in the well-stocked library of Danbury State College, renamed during my time there Western Connecticut State University, writing from time to time for Conatus, the university’s literary magazine – nothing political. The political writing came much later, during the early 1980’s.

My literature professor asked me on my return from D.C. whether I had planned to write anything about the Kennedy assassination. I declined with a sharp “No.”

He would never have understood my reasoning, if one could call it reasoning.

I did not want to shatter the muffled silence – holy, in its own way – that touched everything during the ensuing days and weeks that followed. I just could not join in the general chatter, which I felt was, in some sense, obscene, because much of it was self-glorifying nonsense.

My mother, I recalled, had voted for Kennedy after the Kennedy-Nixon debates, in September 1960. My father, who was one of a handful of Republicans in Windsor Locks, Conn., a Democratic Party bastion, was astonished by this, and asked her at the supper table, where delicate matters were discussed, “Why on earth did you vote for a Democrat?”

“I found Nixon’s eyes shifty,” she said.

This revelation was followed by a muffled silence.

I married my wife, Andree, during my last year at Danbury. On a visit to her house in Fairfield, Conn., I found a framed picture of Kennedy near the family organ adorned by palms, blessed during Palm Sunday, fresh and smelling like the incense-drenched church in which we were married.

That day in Washington, we stood silent as horses’ hooves beat a tattoo on streets. First came the coffin born by white horses, wintry plums of breath streaming from the horses’ wide nostrils, these followed by “Black Jack’’, a riderless horse, boots strapped backwards covering its stirrups, then the crowd. All was shrouded in a holy silence in which, if one was paying close attention, one might hear the voice of Blaise Pascal saying, “In the end, they throw a little dirt on you, and everyone walks away. But there is One who will not walk away.”

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

National Hat Co. factory in Danbury. For many decades Danbury was famous as a center for hat making. Sadly, mercury was used for making the felt that made up most of the hats, poisoning many workers and polluting the Still River. Connecticut didn’t ban this use of mercury until 1937.

We’re all stuck in it

“Gyre” (watercolor and ink), by Newton, Mass.-based painter James Varnum in the show “Beyond the Curve: Members’ Exhibition,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, Dec. 3-Jan. 16

He writes:

“My intent is for viewers to create an association, or an interpretation of the painting that triggers their own narrative.’’

“I was a creative child who liked to sit at the dining room table and draw. I took art classes at the local library during the summer in the small, rural village where I grew up, in Southern New Hampshire. After high school I studied art in Boston and San Francisco, where I earned a B.F.A. from the San Francisco Art Institute.

'‘I soon learned that I could not support myself and a new family as a fine artist, so I went into education, earned a M.Ed. and became a classroom teacher. After nine years, I wanted to specialize my work with children. I earned a M.S. in communication disorders and worked as a Speech Language Pathologist before retiring in 2011. During those thirty-plus years, I kept in touch with my creative side by taking art classes through various continuing education organizations.’’

”Upon retiring, I promised myself that I would pursue art once again. I kept that promise and am an active artist in the Boston area. I belong to several other art associations and actively exhibit my paintings. I classify myself as an experimental watercolor painter.’’

Chestnut Hill Reservoir, near Boston College, in Newton

‘Great equality’ in Mass. in 1789

Samuel Lincoln House, in Hingham, Mass., built on land purchased in 1649 by Samuel Lincoln, an ancestor of Abraham Lincoln

" There is a great equality in the people of this state.

Few or no opulent men, no poor. Great similitude in their buildings, the general fashion of which is a chimney (always of brick or stone), and door in the middle, with a staircase fronting the latter; two flush stories with a very good show of sash and glass windows; the size generally from 30 to 50 feet in length, and from 20 to 30 in width, exclusive of back shed, which seems to be added as the family increases.’’

— George Washington, in his journal of his tour of Massachusetts in 1789

David Warsh: A smelly red herring in Trump-Russia saga

Herrings "kippered" by smoking, salting and artificially dyeing until made reddish-brown, i.e., a "red herring". Before refrigeration kipper was known for being strongly pungent. In 1807, William Cobbett wrote how he used a kipper to lay a false trail, while training hunting dogs—a story that was probably the origin of the idiom.

Grand Kremlin Palace, in Moscow, commissioned 1838 by Czar Nicholas I, constructed 1839–1849, and today the official residence of the president of Russia

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

A red herring, says Wikipedia, is something that misleads or distracts from a relevant and important question. A colorful 19th Century English journalist, William Cobbett, is said to have popularized he term, telling a story of having used strong-smelling smoked fish to divert and distract hounds from chasing a rabbit.

The important questions long have had to do to do with the extent of Trump’s relations with powerful figures in Russian before his election as president; and with whether the FBI did a competent job of investigating those charges.

The herring in this case is the Durham investigation of various forms of 2016 campaign mischief, including (but not limited to) the so-called “Steele Dossier’’. The inquiry into Trump’s Russia connections was furthered (but not started) by persons associated with Hillary Clinton’s campaign. {Editor’s note: The political investigations of Trump’s ties with Russia started with anti-Trump Republicans.}

Trump’s claims that his 2020 defeat were the result of voter fraud have been authoritatively rejected. What, then, of his earlier fabrication? It has to so with the beginnings of his administration, not its end. The proposition that Clinton campaign dirty tricks triggered a tainted FBI investigation and hamstrung what otherwise might have been promising presidential beginning has been promoted for five years by Trump himself. The Mueller Report on Russian interference in the 2016 election was a “hoax,” a “witch-hunt’’ and a “deep-state conspiracy,” he has claimed.

Today, Trump’s charges are being kept on life-support in the mainstream press by a handful of columnists, most of them connected, one way or another, with the editorial page of The Wall Street Journal. Most prominent among them are Holman Jenkins, Kimberly Strassel and Bret Stephens, now writing for The New York Times.

Durham, a career government prosecutor with a strong record as a special investigator of government misconduct (the Whitey Bulger case, post 9/11 CIA torture) was named by Trump to be U.S. attorney for Connecticut in early 2018. A year later, Atty. Gen. William Barr assigned him to investigate the president’s claims that suspicions about his relations with Russia had been inspired by Democratic Party dirty tricks, fanned by left-wing media, and pursued by a complicit FBI. Last autumn, Barr named Durham a special prosecutor, to ensure that his term wouldn’t end with the Biden administration.

There is no argument that Durham has asked some penetrating questions. The “Steele Dossier,” with its unsubstantiated salacious claims, is now shredded, thanks mostly to the slovenly methods of the man who compiled it, former British intelligence agent Christopher Steele. Durham’s quest to discover the sources of information supplied to the FBI is continuing. The latest news of it was supplied last week, as usual, by Devlin Barrett, of The Washington Post. (Warning: it is an intricate matter.)

What Durham has not begun to demonstrate is that, as a duly-elected president, Donald Trump should have been above suspicion as he came into office. There was his long history of real estate and other business dealings with Russians. There was the appointment of lobbyist Paul Manafort as campaign chairman in June 2016; the secret beginning on July 31 of an FBI investigation of links between Russian officials and various Trump associates, dubbed Crossfire Hurricane; Manafort’s forced resignation in August; the appointment of former Defense Intelligence Agency Director Michael Flynn as National Security adviser and his forced resignation after 22 days; Trump’s demand for “loyalty” from FBI Director James Comey at a private dinner a week after his inauguration, and Comey’s abrupt dismissal four months later (which triggered Robert Mueller’s appointment as special counsel to the Justice Department): none of this has been shown to do Hillary Clinton’s campaign machinations.

The Steele Dossier did indeed embarrass the media to a limited extent – Mother Jones and Buzzfeed in particular – but it was President Trump’s own behavior, not dirty tricks, that disrupted his first months in office. Those columnists who exaggerate the significance of campaign tricks are good journalists. So why keep rattling on?

In the background is the 30-year obsession of the WSJ editorial page with Bill and Hillary Clinton. WSJ ed page coverage of the story of John Durham’s investigation reminds me of Blood and Ruins, The Last Imperial War 1931-1945 (forthcoming next April in the US), in which Oxford historian Richard Overy argues that World War II really began, not in 1939 or 1941, but with the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931. Keep sniffing around if you like, but what you smell is smoked herring.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

© 2021 DAVID WARSH

Before the water rose higher

“What Was” (oil on canvas), by Cotuit, Mass-based Julie Gifford, at Alpers Fine Art, Andover, Mass. She writes:

“I’m interested in celebrating the spirit of land, sea and sky and the resilience of the creatures who inhabit it. When painting, I’m working on an internal script…a bit of prose which reveals itself through marks on canvas – a personal conversation that comes from within and becomes clear only upon completion.’’

Cahoon Museum of American Art, in Cotuit

Todd McLeish: Weasels seem to be declining in New England and elsewhere in U.S.

The Long-Tailed Weasel seems to be the most common weasel in New England.

A Long-Tailed Weasel in winter coat

Via ecoRI News (ecori.org)

A national study of weasels from across much of the United States has revealed significant declines in all three species evaluated, which has a local biologist wondering about the status of the animals in Rhode Island.

The study by scientists in Georgia, North Carolina and New Mexico found an 87-94 percent decline in the number of least weasels, long-tailed weasels, and short-tailed weasels harvested annually by trappers over the past 60 years.

While a drop in the popularity of trapping and the low value of weasel pelts is partially to blame for the declining harvest, the researchers still detected a significant drop in the populations of all three species.

“Unless you maybe have chickens and you’re worried about a weasel eating your chickens, you probably don’t think about these species very often,” said Clemson University wildlife ecologist David Jachowski, who led the study. “Even the state agency biologists who are charged with tracking these animals really don’t have a good grasp on what is going on.”

The three weasel species are small nocturnal carnivores that feed primarily on mice, voles, shrews, and small birds, often by piercing their preys’ skull with their canine teeth. The weasels prefer dense brush and open woodland habitats, where they search for prey among stone walls, wood piles, and thickets. Because of their secretive nature and cryptic coloring, they are difficult to find and observe.

By assessing trapper data, museum collections, state statistics, a nationwide camera trapping effort, and observations reported on the internet portal iNaturalist, the scientists found the animals to be increasingly rare across most of their range.

“We have this alarming pattern across all these data sets of weasels being seen less and less,” Jachowski said. “They are most in decline at the southern edges of their ranges, especially the Southeast. Some areas like New York and the Canadian provinces can still have some dense pop ulations in localized areas.”

Jachowski noted weasel populations in southern New England are likely facing similar declines as the rest of the country. He believes, however, there is the potential for some areas of the Northeast to still have robust numbers of weasels, especially long-tailed weasels, which are considered the most common of the three species.

Charles Brown, a wildlife biologist at the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management, who contributed data to the national study, said in his 20 years of monitoring mammal populations in the Ocean State, the only one of the three weasel species he has found is the long-tailed weasel.

“I’ve had a few infrequent encounters with them over the years and seen a few dead ones on the road,” he said. “A mammal survey done in the 1950s and early ’60s documented two short-tailed weasels, and those are the only records I’ve found for the species.”

Least weasels are not found within 300 miles of Rhode Island.

Brown has contributed 19 or 20 long-tailed weasel specimens to the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University over the years from many mainland communities, including Little Compton, East Providence, Warwick, and South Kingstown. Weasels are not known to inhabit any of the Narragansett Bay islands.

“It’s hard to say what their status is here,” he said. “Trappers might bring in one or two a year, and some years none, and we don’t have any other indexes to monitor them because they’re cryptic and we rarely see them.”

Brown said a monitoring program could be developed for weasels in the state using track surveys and camera traps, but because the animals have little economic value and do not cause significant damage, they have not been a priority to study.

“In a perfect world, I’d certainly like to try to find a specimen of a short-tailed weasel to see if they’re still around here, but I have nothing to go on about them from a historic perspective,” he said.

Data from the University of Rhode Island is helping to provide a current perspective of the species’ distribution. URI scientists recently concluded a five-year study of bobcats and the first year of a study of fishers, each using 100 trail cameras scattered throughout the state. Among the 850,000 images collected so far are about 150 photos of long-tailed weasels.

According to Amy Mayer, who is coordinating the studies, the weasel images were collected at numerous locations around the state, suggesting the population does not appear to be concentrated in any particular area of Rhode Island.

It is uncertain what could be causing the national decline in weasel numbers, though Jachowski and Brown believe the increasing use of rodenticides, which kill many weasel prey species, could be one factor. A recent study of fishers collected from remote areas of New Hampshire found the presence of rodenticides in the tissues of many of the animals.

“How it’s getting into the food chain in these remote areas, we don’t know,” Brown said. “There was some discussion that a lot of people go up there to summer camps, and when they close the camp up for the season, they bomb it with rodenticides to keep the mice out. That’s just speculation, but it makes sense.”

The decline of weasels may also have to do with changes to available habitat, the scientists said. The maturing of forests and decline of agricultural land has caused a reduction in the early successional habitats the animals prefer. Brown also believes the recovery of hawk and owl populations, which compete with weasels for mice and voles and which may occasionally kill a weasel, could also be a factor.

Jachowski said the findings from his national study have led to the formation of what he is calling a “weasel working group” to share data and discuss how to monitor the animals around the country. Brown is among the state biologists and academic researchers who are members of the group.

“We’re hoping the public will become involved, too, by reporting their sightings to iNaturalist,” Jachowski said. “We need to see where they persist, and then we can tease out what habitats they’re still in, what regions, and then do our studies to figure out what kind of management may be needed.”

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish runs a wildlife blog.e

Scott Klinger: Trump’s postmaster general continues to wreak havoc as Christmas nears

The old post office in Augusta, Maine, a notable example of Romanesque architecture

Via OtherWords.org

HARPSWELL, Maine

Last year’s holiday season was not exactly a merry one for the U.S. Postal Service. In the lead-up to Christmas, overwhelmed postal workers had to leave gifts sitting in sorting facilities for weeks. They delivered just 38 percent of greeting cards and other nonlocal first-class mail on time.

What should we expect this year?

USPS leaders claim they are ready for the rush. But customers have reason to worry about slower — and more expensive — service.

The service is aiming to hire 40,000 seasonal workers for the holidays. But that’s 10,000 less than last year — and given broader pandemic staffing shortages, recruitment and retention for these demanding jobs will not be easy. While the e-commerce surge that strained the system last year has declined somewhat, postal workers are still delivering many more packages than before the crisis.

And COVID-19 is not the only reason for concern. In fact, the root causes of our country’s postal problems are inaction by Congress and misguided action by USPS leadership.

For more than a decade, Congress has failed to fix a policy mistake that requires the Postal Service to set aside money to prefund retiree health care more than 50 years in advance. This burden, which applies to no other federal agency or private corporation, accounts for 84 percent of USPS reported losses from 2007 to 2020. If Congress had made the same demand of America’s strongest businesses, many would be bankrupt.

A bill to repeal this pre-funding mandate and put USPS on a stronger financial footing enjoys strong bipartisan support. But House and Senate leaders have not brought up this bill, the Postal Reform Act, for a vote.

In the meantime, U.S. Postmaster General Louis DeJoy, a Trump campaign contributor, is using the agency’s artificially large losses to justify jacking up prices and slowing deliveries.

If you’re planning to send holiday cards a significant distance this season, say from Pittsburgh to Boise, the USPS delivery window is now five days instead of three. These reduced service standards affect about 40 percent of First Class mail.

As part of a 10-year plan, DeJoy is also slowing delivery by 1 to 2 days for about a third of First Class packages. These are small parcels often used to ship highly time-sensitive medications, as well as other lightweight e-commerce purchases.

A big cause of the slowdown: DeJoy’s plan to cut costs by shifting long-distance deliveries from planes to trucks. This is a rollback of the introduction of airmail more than 100 years ago — one of many postal innovations that strengthened the broader U.S. economy.

For worse service, we’ll have to pay more.

In August, USPS raised rates for First Class mail by 6.8 percent and for package services by 8.8 percent. A holiday surcharge will raise delivery costs by as much as $5 per package through December 26. In January, rates for popular flat-rate boxes and envelopes will increase by as much as $1.10.

Next up on DeJoy’s plan: reduced hours at some post offices and the closure of others.

USPS officials argue these draconian moves will boost profits. But even the regulator that oversees the agency has criticized the underlying financial analysis.

Instead, DeJoy’s 10-year plan will more likely drive customers away. That, in turn, will lead to fewer of the good postal jobs that have been a critical path to the middle class, particularly for Black families.

Unless Washington lawmakers lift the financial burden they imposed on USPS, DeJoy will be empowered to keep up his self-defeating cost-cutting spree.

Postal workers and their customers have struggled to overcome the extreme challenges of the pandemic. Now it’s time for Congress to deliver by passing the Postal Reform Act and urging USPS leaders to focus on innovations to better serve all Americans for generations to come

Scott Klinger, who lives in Harpswell, is senior equitable development specialist at Jobs With Justice.

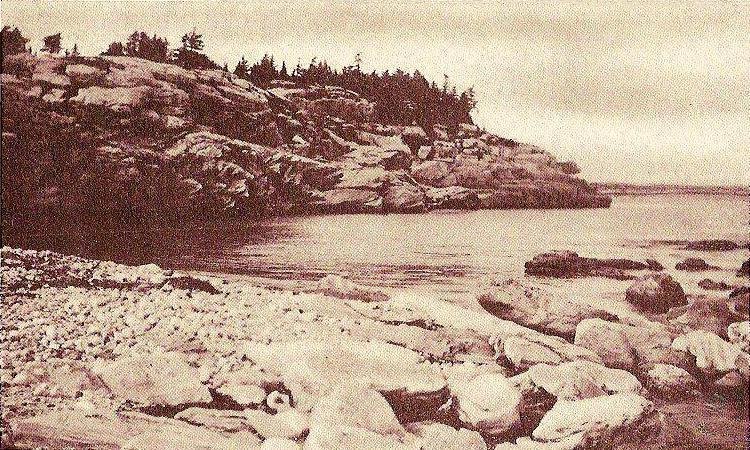

On Ragged Island, Harpswell, Maine, circa 1920

An endless harvest

Spades take up leaves

No better than spoons,

And bags full of leaves

Are light as balloons.

I make a great noise

Of rustling all day

Like rabbit and deer

Running away.

But the mountains I raise

Elude my embrace,

Flowing over my arms

And into my face.

I may load and unload

Again and again

Till I fill the whole shed,

And what have I then?

Next to nothing for weight,

And since they grew duller

From contact with earth,

Next to nothing for color.

Next to nothing for use.

But a crop is a crop,

And who's to say where

The harvest shall stop?

“Gathering Leaves,’’ by Robert Frost (1874-1963)

Raking up the sun

“Dune Shadows: Hyannis, Cape Cod’ (archival pigment print), by Bobby Baker

© Bobby Baker Fine Art

Don Pesci: Beware Democrats' ‘government of force’

VERNON, Conn.

Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont has probably learned more than he has been willing to say from recent state and municipal elections

If one could stretch Lamont out on a comfortable couch and peek into his political psyche, one might find him sharing space with Virginia’s new governor-elect, Glenn Youngkin, and the bête noir of the progressive wing of the national Democratic Party, Sen. Joe Manchin, of West Virginia.

Manchin is something of a Democrat budget hawk, whose hectoring, residual moderates believe, is very much needed in a party that has adopted improvident spending as an operative political principle.

Singing from the balcony of the party’s once vibrant moderate center are =. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, and the lead choir boy, President Biden, all of whom have borrowed hymns from socialist Bernie Sanders's progressive song book.

Budget watchers generally agree that the redistributionist Democratic Party budget, as well as the ideological arc in the once moderate party, has been heavily influenced by Sanders’s eccentric socialistic notions. There are in political parties king makers and budget makers. Sanders and members of the so called "Squad" have become important leftist budget and policy makers in the Democratic Party.

Ideology, the fierce commitment to a political doctrine, is the iron bar in the politics of force. What, we may ask, is the opposite of the politics of force? Surely, few will disagree that its opposite is the still revolutionary notion that government derives its authority to govern from the consent rather than the conquest by power and force of the governed.

Asked shortly after the polls had closed in Virginia whether he thought “the sagging poll ratings of President Biden could affect next year’s elections for Congress and governors’ offices around the country,” Lamont first quipped that “he had spent time Tuesday night,” when election returns were rolling in, “watching the final game of the World Series,” according to a report in a Hartford paper.

Two days later, Lamont was less flippant. The shadow of the New Jersey race had fallen over many Democrats. In New Jersey, Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy won re-election by a breathtakingly small margin, according to Politico: Murphy 1,285,351, Jack Ciattarelli 1,219,906.

Lamont told a reporter, “I certainly feel like there’s a sense that the middle class is getting slammed, but I’ve felt that since I’ve been governor … I think that dysfunction in Washington, D.C., put a cloud on Democratic races…They did have a big tax increase in New Jersey, which I think got people’s attention. We’re in a very different place here in Connecticut. I’ve got to talk to Phil and see what else I can learn from that.”

During his first year in office, Biden, Pelosi and Schumer together have been the principal force leaders in their party. Both have threatened to eliminate the Electoral College in favor of the election of presidents by popular vote, a measure that would allow large population centers, mostly on the East and West coasts, to deprive small states and low-population-density areas of the country of an equitable voice in presidential selection. This measure, like the packing of the Supreme Court, would in the short run benefit a Democratic Party that values force above government action tempered by constitutional restraints. {Editor’s note: A constitutional amendment would be needed to eliminate the Electoral College.}

None of the force leaders in the Democratic Party have hesitated to use the power of government agencies to enhance their own political standing with the American public. The recently concluded elections are the first indication that the American public is, in both the pre- and post-COVID-19 epoch, generally opposed to a mode of governance that has succeeded elsewhere in the world only through the sustained application of the kind of persistent force that raises its horned head in every page of Machiavelli’s The Prince. Pelosi’s own daughter, intending to bestow a compliment, said of her mother, “She’ll cut your head off, and you won’t even know you’re bleeding,” a frighteningly accurate description of the politics of force.

Governments of force are the same everywhere – boringly vicious. Their shared characteristics are: the use of government agencies, unaccountable to the general public and not easily dismissed, to subvert the representative principle, traditional democratic government and the rule of law; the pitiless demonization of political opponents, an over reliance on propaganda and government imposed sanctions; a reliance on messaging, rather than practical and efficient policies, to capture the affections of the general public; and the transference of wealth and decision-making from the private marketplace to an overweening and seemingly omnipresent central government.

“Character,” said Thomas Paine, when the American experiment in republican government was yet in its infancy, “is better kept than recovered.”

If Lamont were a close student of history, rather than a millionaire whom fortune has blessed, he would understand why Biden’s approval ratings are abysmally low, 38 percent by at least one poll, understand what happened in in New Jersey, understand why Democrats are losing their grip on unaffiliated voters, as well as soccer moms, and why it is much easier to keep liberty, justice, constitutional government, the republic and a decentralizing power principle – the separation of the three branches of government – than it would be to restore the characteristics of the American experiment in freedom and representative government after the essential nature of the country had been deformed -- not reformed -- by leftists with knives in their brains.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.