‘A Wintry Mix’

“Would you like to swing on a star?” (collage), by Rich Fedorchak, of Thetford, Vt., in the show “Wintry Mix’,’ at AVA Gallery and Art Center, Lebanon, N.H., Nov. 19-Dec. 30.

The gallery says: "The holiday exhibition will feature the work of member artists from Vermont and New Hampshire. Works in a variety of media—oil, watercolor, drawing, printmaking, mixed media, photography, ceramics, textiles, sculpture, jewelry, and glasswork—will be on display and available for sale in a wide range of prices."

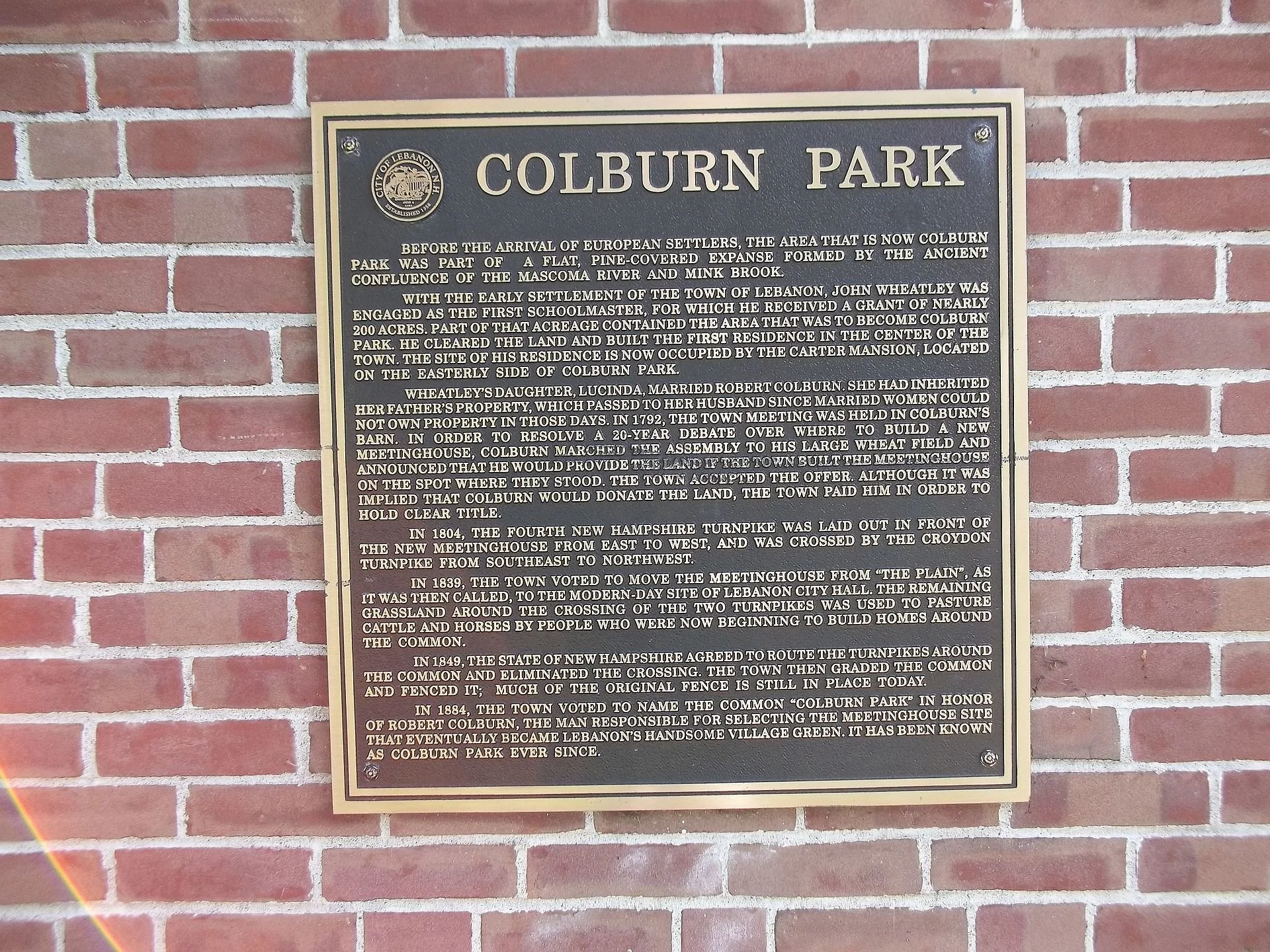

A little local history

— Photo by Artaxerxes

What colleges owe our democracy

The Seeley G. Mudd Building at Amherst College, the elite small liberal-arts college in the Massachusetts town of the same name that has abolished legacy admissions. The striking building, for math and computer science, was designed by Edward Larrabee Barnes and John MY Lee and Partners with Funds donated by the Seeley G. Mudd Foundation, named for a physician and philanthropist who lived from 1895 to 1968 and didn’t attend Amherst.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

WATERTOWN, Mass.

What Universities Owe Democracy; Ronald J. Daniels with Grant Shreve and Phillip Spector; Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore; 2021.

When the president of a major university publishes a deeply researched, closely reasoned, strongly argued powerful idea and call to the profession to respond to an urgent crisis in our national history, it is highly likely to become a classic in the literature of higher education. Ronald Daniels, president of Johns Hopkins University (co-authoring with colleagues Grant Shreve and Phillip Spector), has accomplished that with this new book, appropriately entitled What Universities Owe Democracy.

The New England Journal of Higher Education has responded to the widely recognized “epistemic crisis” in our democracy in two previous articles this year. The first, in April, unpacked the economic, technological, psychological and moral aspects of the problem, to focus on higher education’s purview of epistemology, and contended that it is incumbent upon all public educators—including journalists and jurists—from secondary schools onward, to insist that “thinking on the basis of evidence” is the only reliable way to establish and use the power of knowledge in any field. The second, in September, was a critical review of the journalist Jonathan Rauch’s recent book, The Constitution of Knowledge, asserting that he offered not a solution but part of the problem—that the epistemic crisis in public (or popular) knowledge, Rauch’s actual subject, is exacerbated by journalism’s misconceived habit of promoting as criteria of truth broad public acceptance and trust, rather than thinking on the basis of evidence.

The fundamental issue underlying both those articles—that scholars and scientists have civic responsibility—has now been addressed by Daniels, who has been previously known as a leading advocate for eliminating legacy admissions at prestigious institutions, which he did at Hopkins in 2014. His example was followed by a few others, most recently Amherst College.

The excellence of his book derives from his extraordinary idealism for higher education and the essential, indispensable role of colleges and universities in what he carefully defines as “liberal democracy.” His basic argument is that the welfare of American universities and of democracy have historically been and are strongly interdependent, so it is now necessarily in the academy’s interest to defend democracy from subversion. He poses as the “relevant question,” “How does the university best foster democracy in our society?”

His answer is painstakingly developed. Each of the book’s four chapters features careful definition of terms, a highly informative history of the chapter’s specific issue in American higher education, an analysis of its current challenges, and the author’s policy recommendations. The discussion is lucid, intellectually rigorous, and considerate of the complexities involved. This brief review cannot do justice to his detailed arguments, so I shall highlight a few points of broad interest.

A leitmotif throughout the book is what Daniels calls “liberal democracy,” which he defines in detail as an Enlightenment ideal: “liberal” in favoring individual freedom, “democracy” in promoting political equality and popular sovereignty. Whereas the two can occasionally conflict, society’s common good depends on their equitable balance. On these ideals, he writes, the United States is predicated.

The first chapter focuses on the “American Dream” of social mobility for this (in JFK’s phrase) “nation of immigrants.” Daniels elucidates the pre-eminent role universities have played in promoting it; no other institution, he says, has been throughout our history and still today more influential in that essential function. “Universities are one of the few remaining places where Americans of different backgrounds are guaranteed to encounter one another.” Therefore, colleges and universities must ensure that everything they do contributes to social mobility. This is where the issue of legacy admissions arises—about which, see more to follow.

The next chapter, “Free Minds” concerns civic education. Citizenship must be cultivated; it is not an innate trait. This used to be done by civics courses required at the high school level but in recent decades, that has languished, yielding ground to the rise of science and separate specialized disciplines. Today, only 25% of secondary schools require civic education, but because 70% of students go on to some form of postsecondary education or training, that is where, by default, civic education must be revived. Daniels advocates a “renaissance in civic learning” to reaffirm how the Founders envisioned higher education in our democracy. Noting that robust civics education is unlikely to be recovered by high schools in today’s polarized political environment, he presents a strong historical case for the inclusion of promoting democratic citizenship in higher education. Acknowledging the wide diversity of institutional types and cultures in postsecondary education today, he encourages every institution to develop its own approach.

Daniels then turns to the central role of universities in the creation, promotion and defense of knowledge, upon which liberal democracy is necessarily based. American universities have uniquely combined within single institutions their own undergraduate colleges, professional graduate schools, research facilities and scholarly publishing, protected by academic freedom and tenure. This powerful and mutually reinforcing combination has produced intellectual leadership in our liberal democracy. All this has been potently challenged, however, by developments in modern philosophy (linguistic analysis and epistemology) and more recently information technology (computers, the internet, social networks and artificial intelligence). Daniels courageously addresses these extremely complex and subtle issues (e.g., post-structuralism) in detail. His discussion is enlightening and supports his thesis that universities have a crucial role to play in intellectual leadership, “building a new knowledge ecosystem” that will protect and strengthen liberal democracy.

The next chapter “Purposeful Pluralism” discusses how colleges and universities may promote both greater diversity in their student bodies and genuine mixing of their constituencies by cultivating more inclusive communications and mutual understanding. But while greater diversification has been increased by deliberate admissions strategies, there needs to be sustained follow-through in the infrastructures of student life—in housing and rooming arrangements, dining, socializing, curricular and extracurricular settings, including faculty-student interactions and intellectual life in general. “Our universities should be at the forefront of modeling a healthy, multiethnic democracy.”

He concludes then by reviewing the overall argument, its urgency, and “avenues for reform,” which include: 1) End legacy admissions and restore federal financial aid, 2) Institute a democracy requirement for graduation, 3) Embrace “open” science’ with guardrails and 4) Reimagine student encounters on campus and infuse debate into campus programming. “The university cannot, as an institution, afford to be agnostic about, or indifferent to, its opposition to authoritarianism, its support for human dignity and freedom, its commitment to a tolerant multiracial society, or its insistence on truth and fact as the foundation for collective decision-making,” Daniels writes. “It is hardly hyperbole to say that nothing less than the protection of our basic liberties is at stake.”

While I may not completely agree with all the positions Daniels takes, I strongly believe that every academic reader will find this book highly illuminating, practically useful, and I hope, compelling. One relatively minor point of difference I have is where today’s vexed issue of legacy admissions is directly addressed. Daniels acknowledges that though the numbers of admissions decisions involved is relatively small, their symbolic significance is large, especially owing to the prominence of the institutions involved. The practice is followed by 70 of the top 100 colleges in the U.S. News rankings and, though it affects only 10% to 12% of their comparatively small numbers of students, it sends a message that is widely interpreted as elitist and undemocratic. Daniels focuses more on opposing the message than upon analyzing the practice in detail, and he provides no hard data on the process or results of the elimination of the policy anywhere.

This stood out for me as an odd departure from his usual data-intensive analytical habit. One reason for its exception is that he considers the message more important than the practical details, but another might be that data have not yet shown the abolition of legacy admissions to have significant practical impact on social mobility. Still another might be that, as I understand it, the reasons for which legacies were created are not the reasons for which they should now be abolished. They were instituted and are maintained primarily for internal institutional purposes—i.e., to encourage alumni engagement and fundraising—and not for any public message.

Here we may connect a few separate dots, not presented together in the book. Daniels abolished the practice at Hopkins in 2014 but did not announce it publicly until 2019. In that interval, he also sought and secured in 2018 a sensational gift from Hopkins alumnus Michael Bloomberg, of $1.8 billion for student financial aid. While it is understandable that Daniels would be reluctant to discuss this historical process in detail, or whether it was planned from the start and enabled by a unique advantage Hopkins had with Bloomberg as an alumnus, it is also conceivable that the Hopkins decision was not problem-free, and that the extremely generous grant was invoked as a solution.

In any case, avoiding the practical issue in the book also avoids considering a possible (though admittedly unforeseeable) solution for other institutions now—i.e., taking advantage of the unprecedentedly high multibillion-dollar gains in 2020 endowment yields and personal capital to use them separately or together to make major investments in student financial aid. This may, in other words, be an opportune time to modify legacy policies—perhaps to retain them in some refined or reduced form as an instrument supporting both student diversity and strengthening alumni relations and fundraising, while heading off the public impression of elitism.

The world is changing fast, and it is essential that universities keep up the pace. Political reform is slow and now especially cumbersome, whereas the only impediment to universities adapting and leading is the will to do so. That is where a book such as this can exert palpable influence, and considering how rare it is for such a book to be written, are we not in turn professionally obliged at least to read and think about it?

George McCully is a historian, former professor and faculty dean at higher education institutions in the Northeast, professional philanthropist and founder and CEO of the Catalogue for Philanthropy, based in Watertown, Mass.

Michelle Andrews: In pandemic, many employers have expanded mental-health coverage

In group therapy

As the COVID-19 pandemic burns through its second year, the path forward for American workers remains unsettled, with many continuing to work from home while policies for maintaining a safe workplace evolve. In its 2021 Employer Health Benefits Survey, released Nov. 20, KFF found that many employers have ramped up mental health and other benefits to provide support for their workers during uncertain times.

See Rhode Island organization’s role below.

Meanwhile, the proportion of employers offering health insurance to their workers remained steady, and increases for health-insurance premiums and out-of-pocket health expenses were moderate, in line with the rise in pay. Deductibles were largely unchanged from the previous two years.

“With the pandemic, I’m not sure that employers wanted to make big changes in their plans, because so many other things were disrupted,” said Gary Claxton, a senior vice president at KFF and director of the Health Care Marketplace Project. (KHN is an editorially independent program of the foundation.)

Reaching out to a dispersed workforce is also a challenge, with on-site activities like employee benefits fairs curtailed or eliminated.

“It’s hard to even communicate changes right now,” Claxton said.

Many employers reported that since the pandemic started they’ve made changes to their mental-health and substance-use benefits. Nearly 1,700 nonfederal public and private companies completed the full survey.

At companies with at least 50 workers, 39% have made such changes, including:

31% that increased the ways employees can tap into mental-health services, such as telemedicine.

16% that offered employee assistance programs or other new resources for mental health.

6% that expanded access to in-network mental health providers.

4% that reduced cost sharing for such visits.

3% that increased coverage for out-of-network services.

Workers are taking advantage of the services. Thirty-eight percent of the largest companies with 1,000 or more workers reported that their workers used more mental health services in 2021 than the year before, while 12% of companies with at least 50 workers said their workers upped their use of mental health services.

Thundermist Health Center is a federally qualified health center that serves much of Rhode Island. (It’s based in Woonsocket.) The center’s health plan offers employees an HMO and a preferred provider organization, and 227 workers are enrolled.

When the pandemic hit, the health plan reduced the co-payments for behavioral health visits to zero from $30.

“We wanted to encourage people to get help who were feeling any stress or concerns,” said Cynthia Farrell, associate vice president for human resources at Thundermist.

Once the pandemic ends, if the health center adds a co-payment again, it won’t be more than $15, she said.

The pandemic also changed the way many companies handled their wellness programs. More than half of those with at least 50 workers expanded these programs during the pandemic. The most common change? Expanding online counseling services, reported by 38% of companies with 50 to 199 workers and 58% of companies with 200 or more workers. Another popular change was expanding or changing existing wellness programs to meet the needs of people who are working from home, reported by 17% of the smaller companies and 34% of the larger companies that made changes.

Beefing up telemedicine services was a popular way for employers to make services easier to access for workers, who may have been working remotely or whose clinicians, including mental-health professionals, may not have been seeing patients in person.

In 2021, 95% of employers offered at least some health care services through telemedicine, compared with 85% last year. These were often video appointments, but a growing number of companies allowed telemedicine visits by telephone or other communication modes, as well as expanded the number of services offered this way and the types of providers that can use them.

About 155 million people in the U.S. have employer-sponsored health care. The pandemic didn’t change the proportion of employers that offered coverage to their workers: It has remained mostly steady at 59% for the past decade. Size matters, however, and while 99% of companies with at least 200 workers offers health benefits, only 56% of those with fewer than 50 workers do so.

In 2021, average premiums for both family and single coverage rose 4%, to $22,221 for families and $7,739 for single coverage. Workers with family coverage contribute $5,969 toward their coverage, on average, while those with single coverage pay an average of $1,299.

The annual premium change was in line with workers’ wage growth of 5% and inflation of 1.9%. But during the past 10 years, average premium increases have substantially exceeded increases in wages and inflation.

Workers pay 17% of the premium for single coverage and 28% of that for family coverage, on average. The employer pays the rest.

Deductibles have remained steady in 2021. The average deductible for single coverage was $1,669, up 68% over the decade but not much different from the previous two years, when the deductible was $1,644 in 2020 and $1,655 in 2019.

Eighty-five percent of workers have a deductible now; 10 years ago, the figure was 74%.

Health-care spending has slowed during the pandemic, as people delay or avoid care that isn’t essential. Half of large employers with at least 200 workers reported that health-care use by workers was about what they expected in the most recent quarter. But nearly a third said that utilization has been below expectations, and 18% said it was above it, the survey found.

At Thundermist Health Center, fewer people sought out health care last year, so the self-funded health plan, which pays employee claims directly rather than using insurance for that purpose, fell below its expected spending, Farrell said.

That turned out to be good news for employees, whose contribution to their plan didn’t change.

“This year was the first year in a very long time that we didn’t have to change our rates,” Farrell said.

The survey was conducted between January and July 2021. It was published in the journal Health Affairs and KFF also released additional details in its full report.

Michelle Andrews is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Woonsocket's city hall

—Photo by Kenneth C. Zirkel

The art of avoidance

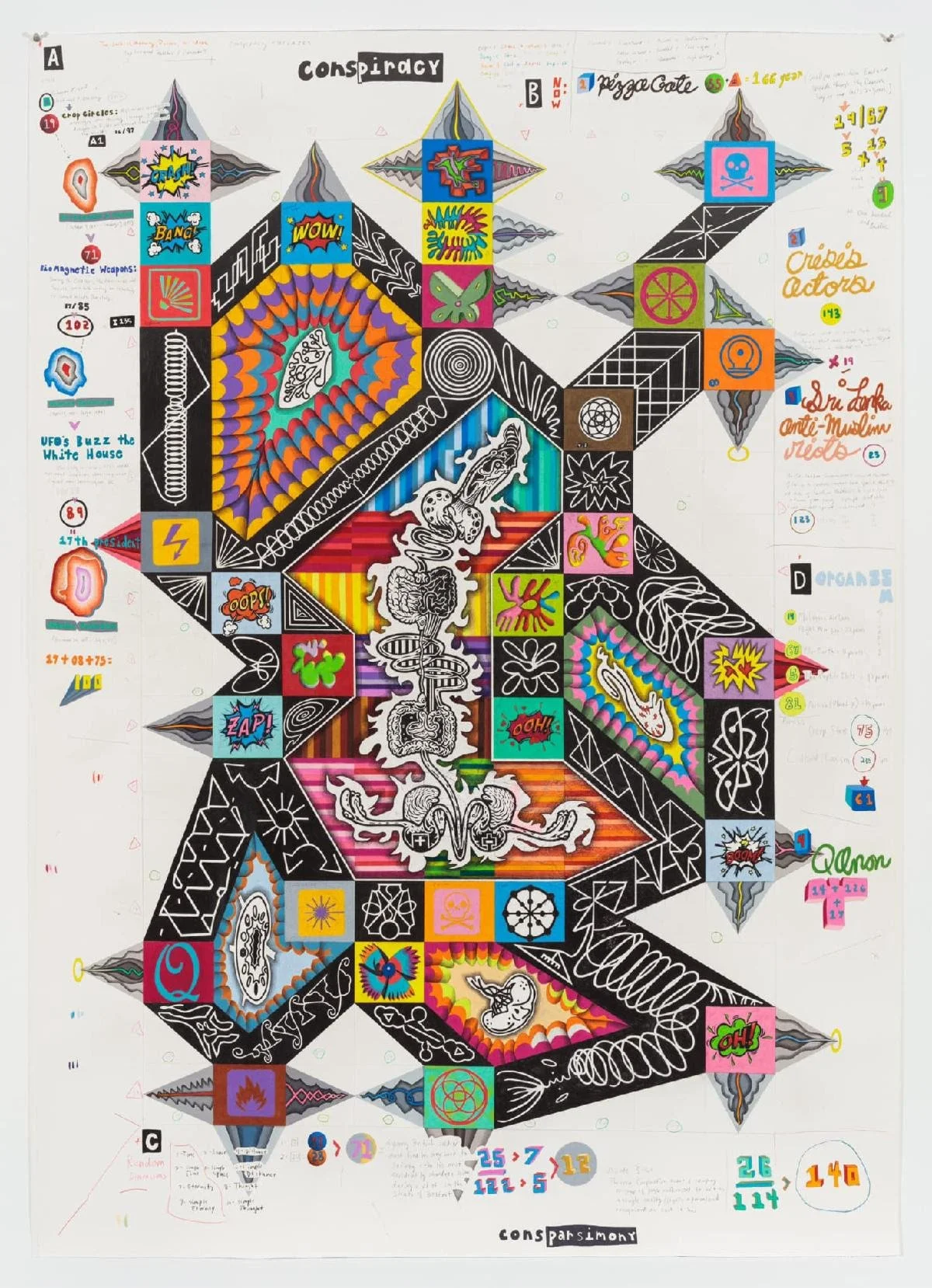

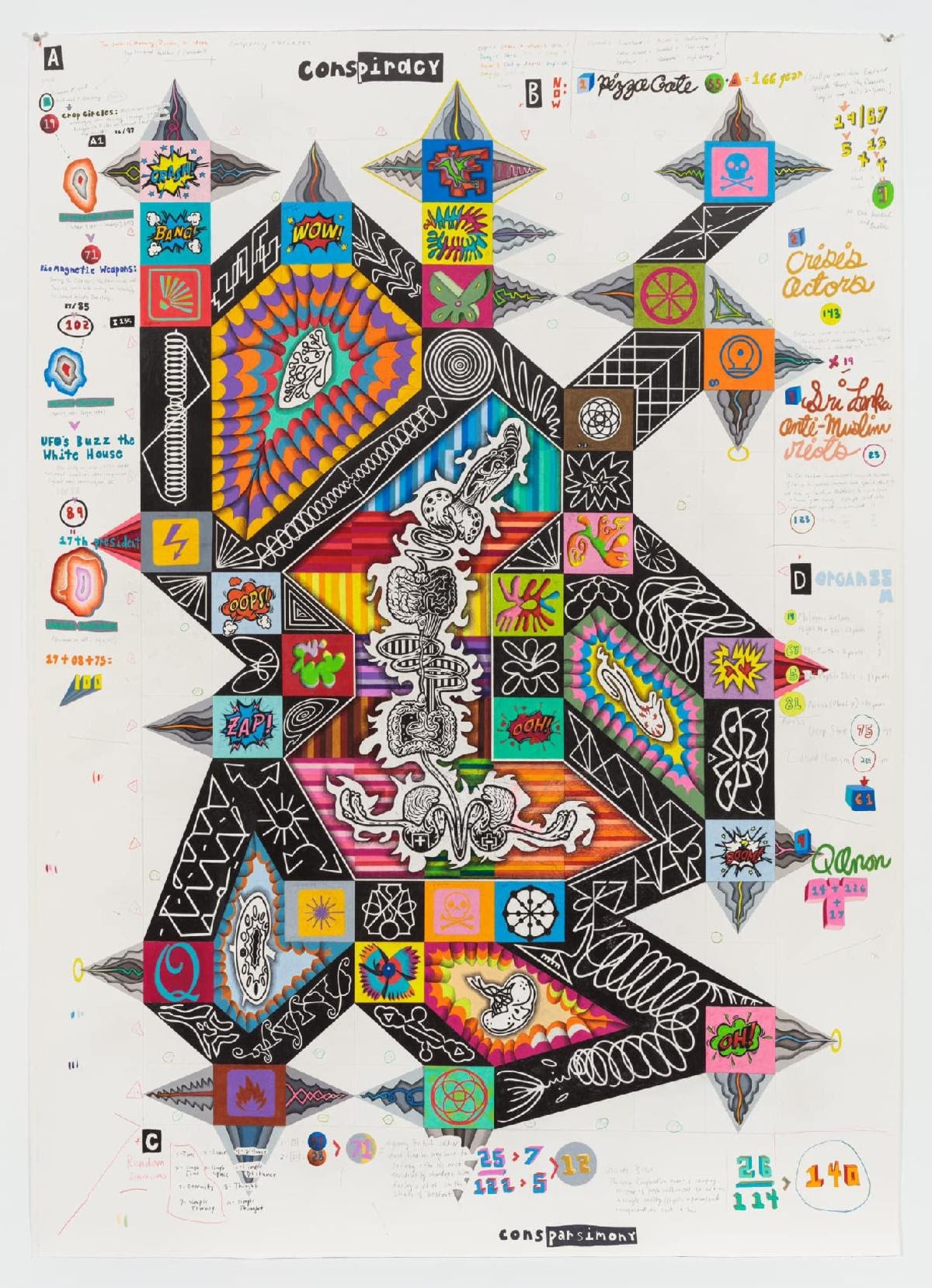

“Conspiracy Shape” (graphite and colored pencil on paper), by John O’Connor, in his show "John O’Connor: Self Avoiding Walks’’, at Bannister Gallery at Rhode Island College, Providence, through Dec. 10.

The gallery explains that Mr. O’Connor “combines text, sketch, and musings reminiscent of field journals with influence and undertones that show what ultimately cannot be avoided. His drawings evolve incrementally over long spans of time, as O’Connor absorbs, plots, and transforms information into vibrantly colored pieces that straddle an aesthetic line between diagrams and fully articulated structures, forms, and spaces.”

Based in the New York City area, he’s originally from Westfield, Mass.

Downtown Westfield and Park Square

External and internal landscapes

“Connecticut River Valley at Claremont, N.H.,’’ by Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902)

Along the Connecticut: Riverbank reconstruction project in Fairlee, Vt.

“There are few things as involuntary as a person’s identification with a landscape.’’

— Terry Osborne, writer and teacher, in his book Sightlines: The View of a Valley Through the Voice of Depression. He died of cancer in 2020 at the age of 60.

From the official summary of the book:

“For twelve years, writer Terry Osborne devoted himself to an intense exploration of the physical environment near his home in the {Upper} Connecticut River Valley {where he lived first in Thetford, Vt., and then in Etna, N.H.} The more he walked the land, the more deeply he came to know its hills and wetlands. But his growing intimacy with the area inspired something unexpected. The valley, formed by colliding and dividing continents, scoured by massive glaciers, and cut by rivers and streams, began to reveal and resonate with Osborne's internal landscape, long shaped from within by an unyielding depressive voice.’’

Llewellyn King: Using school buses, etc., to store energy in the new electricity revolution

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Carbon-free electricity isn’t a final destination – it is merely a stop along the road to a time when electricity becomes the clean fuel of choice and reduces pollution in buildings, cement and steel production, transportation and other places and industries.

That is the glorious future that Arshad Mansoor, president and CEO of the Electric Power Research Institute, sees. He revealed his vision on White House Chronicle, the weekly news and public-affairs program on PBS, which I host, on his way to the COP26 summit in Glasgow, Scotland.

Mansoor, who talks about the future with an infectious fervor, was joined on the broadcast by Clinton Vince, chairman of the U.S. Energy Practice at Dentons, the globe-circling law firm, and Robert Schwartz, president of Anterix, a Woodland Park, N.J.-based firm that is helping utilities move into the digital future with private broadband networks.

Mansoor outlined a trajectory in which electric utilities must invest substantially in the near future to deal with severe weather and decarbonization. For example, he said, some power lines must be put underground and many must be tested for much higher wind speeds than were envisaged when they were installed. Some coastal power lines must be raised, he said.

While driving toward a carbon-free future, Mansoor cautioned against utilities going so fast into renewables the nation ignores the ongoing carbon-reduction programs of other industries. Further, if utilities can’t meet the electricity demands of transportation or manufacturing, these industries will turn away from the electric solution.

“Overall, we looked at the numbers and they showed a huge national role in decarbonization for the electric utility industry,” Mansoor said. However, the transition is fraught. It must be managed, sometimes using more gas until the system can be totally weaned from fossil fuels, he said. An orderly transition is vital.

Clinton Vince said the electric utility world has experienced a lot of volatility from severe weather, due to climate change, to the Covid-19 pandemic, and cyber-intrusions. “If I were to boil down to one word what is vital for utilities, it would be ‘resilience.’ ”

Resilience is an ongoing utility goal: It is the ability of a single utility or a group of utilities to bounce back from adversity, often by restoring power quickly. Anterix’s Robert Schwartz said that with his company’s private broadband networks and the deployment of enough sensors, a utility could identify a power line break in 1.4 seconds, before it hits the ground.

One of the most exciting and revolutionary aspects of Mansoor’s thinking is that the consumer will become a partner in the electric utility future. They will join the ecosystem by providing load-management assistance through smart meters, now installed in 60 percent of homes.

Mansoor thinks that the nation’s 480,000 school buses, if electrified, along with private electric vehicles, can be used to store energy. This answers the concern many utility executives have about storage and the concern that a tsunami of electric vehicles will overpower electric supply in the coming decade.

I think the utilities should plan right now for the integration of electric vehicles into their systems. They should offer electric vehicle owners financial incentives for plugging in and sending their stored power to the grid.

Likewise, the utilities should provide rate incentives for off-peak electric vehicle charging. They could do worse than look at the algorithms that have made Uber and Lyft possible, unlocking value in the personal car.

The utilities could devise a flexible system whereby they pay for power when needed and give a price break for charging during off-peak hours, or when there is a surfeit of renewable energy. That is the kind of data flow that will mark the utilities going forward and stimulate demand for private broadband networks.

We, the consumers, will be partners in the electric future, managing our own uses and supporting the grid with our electric cars and trucks. That is Mansoor’s achievable vision.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

White House Chronicle

'The return of hope'?

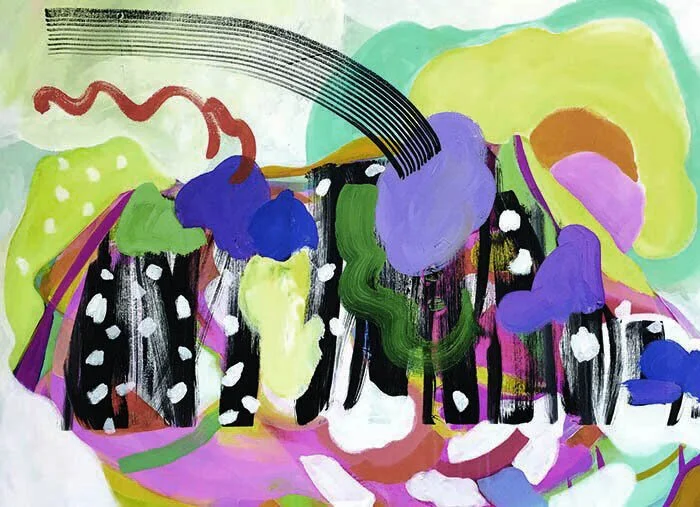

“Parades and Popsicles” (acrylic on canvas), by Amantha Tsaros, in her show “Feral Joy,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, through Nov. 28.

The gallery describes her show as “lively forms in paintings that celebrate the return of hope.’’

She’s based in Lexington, Mass.

“The Old Belfry’’ in Lexington. From the original version of this structure a bell was rung to warn townspeople of advancing British troops before the battles of Lexington and Concord, on April 19, 1775, the first major battles of the American Revolution. It’s rung every April 19 at 5:30 a.m. in celebration of that day.

— Photo by Oeoi

‘As far I can manage’

Roger Tory Peterson at work

“Why do I live in Connecticut? As an artist and a writer I need New York for the American Museum of Natural History and Boston for Houghton Mifflin, my publisher. But as a naturalist I prefer to live as far from either as I can manage.’’

— Roger Tory Peterson (1908-1996), writer, naturalist and environmentalist, in All Things Reconsidered. He became famous for his field guides to nature and especially for his bird guides, which he wrote and illustrated. He spent the last 42 years of his life living in Old Lyme, Conn., where the Connecticut River flows into Long Island Sound.

Railroad Bridge connecting Old Lyme and East Lyme

— Photo by Morrowlong

Narrow days

Northern beech in autumn

— Photo by Łukasz Smolarczyk

“My days show narrow

As the gray clouds layered behind

Branches laid bare

Who look beyond November skies.’’

— From “November Skies,’’ by Rachel Maher, a writer and painter who lives in southern Maine.

Bring back this urban starter housing

A three-decker in Cambridge, Mass.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

There’s a very useful article by Aaron Renn in Governing Magazine about how “poor neighborhoods” with lots of owner-occupied dwellings provided a springboard for people to enter the middle class. It sure beats massive, impersonal and often crime-ridden public-housing projects. An example would be those New England neighborhoods of “three-deckers” in places like South Boston. The owners often live on just one floor and rent out the rest of the building – a way to start gaining middle-class wealth.

But, as I’ve noticed in the U.S. cities where I’ve lived – Boston, New York, Philadelphia and Providence – public policies and changing social attitudes have eroded the benefits of this “starter housing’’ for years. Among Mr. Renn’s observations:

“The rise of zoning and ever-stricter building codes … played a role, especially in recent years, preventing the construction of traditional starter neighborhoods.”

“Changing zoning regulations to create more affordable neighborhoods in some of America’s most expensive cities would help establish platforms for upward mobility. …{But} other factors played into making these old neighborhoods what they were. They were high in social capital, characterized by intact married families, and populated with people who possessed the skills needed for building maintenance. These exist today in some immigrant communities, but less so in society at large.’’

(Ah yes, the collapse of marriage and the stability that went with it.)

Policy makers take note, particularly considering a housing-cost crisis that shows few signs of abating.

To read Mr. Renn’s article, please hit this link.

'Inner landscapes'

“Death Valley” (archival pigment print), by Jane Paradise, in her joint show with Alan Strassman, “American Landscape: Two Views,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, through Nov. 28.

She writes:

“My photographs represent several road trips across the East and West coasts over the past 13 years. Before my husband came down with Alzheimer’s, these road trips were an integral part of our lives. During one road trip up the California coast, we carved our initials into the side of a bullet-ridden abandoned car, shown in the image ‘Vichy Springs.’

“Looking over the photographs of our travels, I selected images that reflect the vast variations of the quirky American experience. Underlying the images of our culture are themes of its humanity. Sometimes it is turning away from one's surroundings to survey inner landscapes, catching a moment in time."

She lives in Provincetown.

Over Provincetown: Looking south east from the top of Pilgrim Monument. Macmillan Wharf, far left. Fishermen's Wharf, left-center. Coast Guard Pier, far right. Long Point, right and center, just below the horizon, with Long Point Light near the tip (just left of center).

— Photo by RoySmith

Chris Powell: Biggest barrier to GOP in Conn. in ‘22 and ‘24 is Trump redux

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Republicans did fairly well in Connecticut's municipal elections last week, picking up many suburbs and smaller towns, holding the mayoralties in some smaller cities -- New Britain, Danbury, and Norwich -- gaining the mayoralty in Bristol, and nearly gaining the mayoralty in heavily Democratic and poorly managed West Haven, which was being looted right under the mayor's nose by one of her confidants.

Bristol hosts the studios of ESPN, and Lake Compounce, founded in 1846 and the United States's oldest continuously operating theme park. Bristol was well known as a clock-making city in the 19th Century. The American Clock & Watch Museum is there, as well as the site of the former American Silver Company and its predecessor companies.

"The map is setting up beautifully for 2022 for Republicans," their state chairman, Ben Proto, crowed.

But not so fast.

First, municipal elections are the least determined by party principles and the most by local personalities. Indeed, municipal government in Connecticut has little to do with public policy. Most of its finances are on automatic pilot, a matter of just signing off on government employee union contracts devised under the pressure of binding arbitration and causing the great majority of municipal expense.

Second, Connecticut remains a solidly Democratic state. Nobody last week paid much attention to the usual huge Democratic pluralities in the big cities, since the election results there were pre-ordained. But those pluralities will reappear next year in the statewide election, where they are usually decisive no matter how well Republicans do elsewhere.

And third, Donald Trump didn't haunt Connecticut Republican campaigns this year. Since next year's election is a congressional election and Trump seems to be planning to run for president again in 2024, Connecticut voters soon may be reminded of him a lot more. The Biden administration is so incompetent and extreme leftist that it may be possible to imagine Trump winning in 2024, but it is not possible to imagine him carrying Connecticut. It is easy to imagine him destroying the Republican Party here next year and in 2024 just as he destroyed it last year, wiping out the gains that Republicans had been making in the General Assembly.

Escaping Trump remains the great challenge of any Republican who wants to win in Connecticut. It shouldn't be impossible, since many Republican policies could win a referendum in Connecticut and can be advocated without reference to Trump, while the Trump problem is mainly a matter of his hateful character and demeanor. But many Connecticut Republicans -- maybe a majority of the most active ones, primary voters -- are devoted to that character and demeanor and rather than give them up might prefer to lose on policy forever.

Using specific state issues against his Democratic opponent, Virginia's new Republican governor-elect, Glenn Youngkin, held Trump at bay without alienating Trump supporters. So the more Connecticut's Republican candidates press specific issues next year, the more they may cause people to put policy ahead of Trump. As the village rabbi in Fiddler on the Roof replied when asked if there was a blessing for the czar: "May God bless and keep the czar -- far away from us."

xxx

In any case going into next year's state election Connecticut Republicans are likely to get help from the craziness of the leftists who dominate the state's Democratic Party and make it hard for Gov. Ned Lamont to maintain a moderate stance.

City administrations, including Hartford's, are sure to provide Republicans with plenty of campaign fodder if the Republicans have the nerve to risk controversy. For example, according to The Hartford Courant, last week a city government committee drafted plans for the city's experiment with a program of "universal basic income."

The idea is to give $500 a month, unconditionally, to 25 single parents or guardians. But the committee thinks that it needs a mechanism for determining whether the money really reduces stress in the lives of the recipients. So the committee may propose making recipients undergo invasive tests to measure their stress hormones.

Of course winning a lottery's grand prize or inheriting a great amount of money may cause the stress of figuring out what to do with it. But since when is any special research needed to determine whether $500 more per month will make someone's life easier?

The movie Animal House famously depicted the statue of college founder Emil Faber inscribed with the moronic motto "Knowledge is good." Hartford could add, so scientifically: "Money too."

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

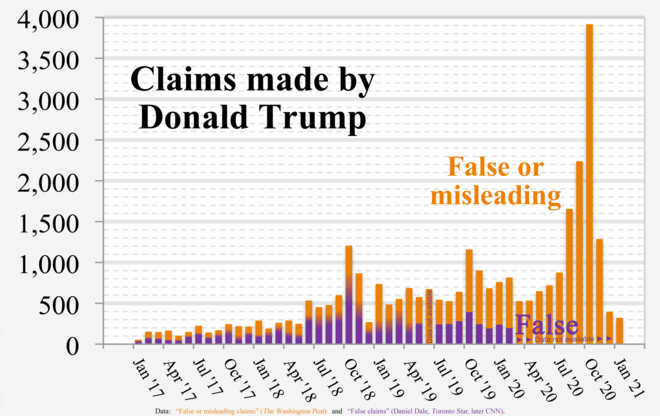

Fact-checkers from The Washington Post, the Toronto Star, and CNN compiled data on "false or misleading claims" (orange background), and "false claims" (violet foreground), respectively.

Kitchen art

“Home Brew” (oil on panel), by Rachel Wilcox, in the group show “Small Works, Big Impacts,’’ at Edgewater Gallery, Middlebury, Vt., starting Nov. 15.

The gallery says the five pieces she has delivered to the show “further explore her restaurant kitchen theme but also include vignettes from her own kitchen. Each painting gives the viewer an intimate, and compositionally intriguing snapshot of parts of working kitchens.’’

She lives and works in Amesbury, Mass., on the north side of the Merrimack River.

From The Boston Cooking School magazine of culinary science and domestic economics in 1896

The Whittier Memorial Bridge over the Merrimack River. The bridge, named for the once famous Massachusetts poet and abolitionist John Greenleaf Whittier (1807-1892), who grew up on a farm in nearby Haverhill, connects Amesbury and Newburyport.

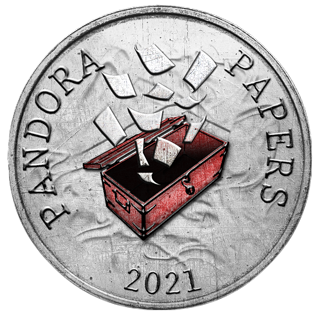

Bill Minter: The United States of places to hide corrupt foreigners' piles of money

For foreign crooks, The Granite State is a place to live free and thrive.

Via OtherWords.org

{Editor’s note: New Hampshire is also a major place to hide ill-gotten gains. Hit this link.}

There are many ways in which the United States is not one country.

I’m not referring to red states versus blue states, or racial or ethnic divisions. What I mean is that the United States, where countless corrupt billionaires and dictators have stashed their loot, is not a single tax haven, but many separate tax havens.

The Pandora Papers, released in October, show that the United States is second only to the Cayman Islands in facilitating illicit financial flows. But it’s not a simple picture.

Each state and territory has its own laws and regulations about financial transactions used for tax evasion or money laundering. And both red states and blue states are destinations for those who seek to hide their money from tax collectors and public scrutiny.

President Biden’s home state of Delaware has long been renowned for its use as a tax haven, beginning in the late 19th Century. Reliably Democratic in national politics, Delaware still ranks at the top among U.S. states providing secrecy for corporations and ultra-high-wealth individuals, both domestic and foreign.

But the Pandora Papers cite ruby-red South Dakota as an attractive destination for billionaires and others seeking to avoid estate taxes.

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), which led the Pandora Papers investigation, obtained access to the records of the Sioux Falls office of Trident Trust. Among its clients were the family of Carlos Morales Troncoso, former president of Central Romana, the largest sugar plantation in the Dominican Republic — which is notorious for its exploitation of Haitian workers.

South Dakota led the way in providing such trusts, as reported in detail even before the current revelations. But other states, including Alaska, Florida, Delaware, Texas, and Nevada, have followed suit.

The Pandora Papers also document the luxury real estate holdings of Jordan’s King Abdullah. Like many other politicians and oligarchs around the world, King Abdullah owns real estate in many places outside his country. The ICIJ found records of his purchases in London and Washington, D.C., among other cities, as well as three side-by-side mansions in a luxury enclave in Malibu, California.

Bottom line: those seeking to track down the hidden wealth that dictators, criminals, or jet-setting billionaires have lodged in the United States must not limit their efforts to supporting changes in national legislation in Washington, D.C. They must also turn the spotlight on state and local communities around the country.

In February 2017, for example, The Washington Post called attention to the fact that U.S. relations with Gambia and Equatorial Guinea were not just “foreign policy” but also a local story in Potomac, Md.

Ousted Gambian dictator Yahya Jammeh lived at 9908 Bentcross Drive in the D.C. suburb. His counterpart Teodoro Obiang Nguema, who has ruled Equatorial Guinea since his successful coup in 1979, still owns the house at nearby 9909 Bentcross Drive.

The effects of these mechanisms to hide assets from taxation and siphon money to the rich are felt at all levels — from the failure to address global crises such as climate change and the pandemic to gross inequality in housing and other essential needs.

Exposing those mechanisms and building the political will to curb illicit financial flows requires action not only in national capitals and global institutions, but also in all the jurisdictions where wealth is hidden. Nowhere is this more true than for the United States.

In Washington, this message from the Panama Papers is beginning to be heard if not yet followed.

A recent Washington Post editorial read “States must stop letting the ultrawealthy dodge taxes — and the law.” Despite the limited progress on national legislation, that fight can begin in states across the country — probably including yours.

William Minter is the editor of AfricaFocus Bulletin and an advisor to the U.S.-Africa Bridge Building Project. This op-ed was adapted from Africa Is a Country.

Horror in the Hub

On downtown Boston’s then weekend-gloomy Washington Street in 1962. Note that the Paramount is playing a typical horror movie of that era — Premature Burial. Looks like the sailor at the left is conducting some business with a professional lady or man of the streets. And note the outlet of that quintessential Boston company Prince Spaghetti.

Easier to hike than to say

Old train station along the Ashuwillticook Rail Trail

Hit this link to see where text immediately below comes from.

“One particular attraction enjoyed by locals and visitors alike is the Ashuwillticook Rail Trail, which runs parallel to Route 8 and runs through the towns of Adams, Cheshire and Lanesborough with an extension under construction leading to Pittsfield projected to be completed next May. …Walking, biking, jogging, and rollerblading are popular trail activities on this Sometimes I grabbed my headphones and did my daily walk on the trail. It’s a great way to get some exercise while getting a beautiful view of what the Berkshires has to offer, particularly the views of Cheshire {Reservoir} as you pass through Cheshire town.’’

Cheshire Reservoir

A little history:

The Ashuwillticook Rail Trail is built on a former railroad corridor that runs parallel to Route 8 through Cheshire, Lanesborough and Adams, Mass.

The trail passes through the Hoosac River Valley, between Mount Greylock and the Hoosac Mountains. Cheshire Reservoir, the Hoosic River and associated wetlands flank much of the trail. The word Ashuwillticook (ash-oo-will-ti-cook) is from the Native American name for the south branch of the Hoosic River and means “at the in-between pleasant river,” or in common tongue, “the pleasant river in between the hills.”

Built during the 1800s industrial boom, the railway was a vital commercial link from the Atlantic Seaboard to communities that would have otherwise been isolated in the Berkshires.

‘Dreams of Boston’

Ferries and other boats at Long Wharf, Boston

“She comes from Boston

Works at the Jewelry Store

Down in the harbor

Where the ferries come to shore.’’

– From song “Boston, by Kenny Chesney

The Paifang Gate, the best-known entrance to Boston’s Chinatown. It’s the only real Chinatown left in New England, after the gradual disappearance of those in Providence and Portland.

“I’ve had dreams of Boston all of my life

Chinatown between the sound of the night.’’

—From “Ladies of Cambridge,’’ by the rock band Vampire Weekend

Easier to bike than to say

Old train station in Cheshire, Mass.

Hit this link to see where the text below comes from.

https://6park.news/massachusetts/10-quotes-will-make-you-explore-the-ashuwillticook-rail-trail.html

“One particular attraction enjoyed by locals and visitors alike is the Ashuwillticook Rail Trail, which runs parallel to Route 8 and runs through the towns of Adams, Cheshire and Lanesborough with an extension under construction leading to Pittsfield projected to be completed next May. …Walking, biking, jogging, and rollerblading are popular trail activities on this Sometimes I grabbed my headphones and did my daily walk on the trail. It’s a great way to get some exercise while getting a beautiful view of what the Berkshires has to offer, particularly the views of Cheshire {Reservoir} as you pass through Cheshire town.’’

Cheshire Reservoir

A little history:

The Ashuwillticook Rail Trail is built on a former railroad corridor that runs parallel to Route 8 through Cheshire, Lanesborough and Adams, Mass.

The trail passes through the Hoosac River Valley, between Mount Greylock and the Hoosac Mountains. Cheshire Reservoir, the Hoosic River and associated wetlands flank much of the trail. The word Ashuwillticook (ash-oo-will-ti-cook) is from the Native American name for the south branch of the Hoosic River and means “at the in-between pleasant river,” or in common tongue, “the pleasant river in between the hills.”

Built during the 1800s industrial boom, the railway was a vital commercial link from the Atlantic Seaboard to communities that would have otherwise been isolated in the Berkshires.

You have 5 minutes to untangle

“Aerial Lavender” (ceramic and mixed media), by Linda Leslie Brown, in her show “Entangled,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, through Nov. 28.

Ms. Brown, who lives in Boston, says of her recent work:

“My recent sculptural work draws upon the transformative exchanges between nature, objects and viewers’ creative perception. These works are rife with allusions to the body. At the same time they suggest the plastic, provisional, and uncertain world of a new and transgenic nature, where corporeal and mechanical entities recombine. And because they are small — no larger than a human head — they invite viewers to engage in an intimate examination that is both delightful and disturbing.’’