Chris Powell: Appeal on abortion won’t lure Texas firms to Conn.

M ANCHESTER, Conn.

While he tries to be a moderate Democratic governor and indeed is more moderate than his predecessor, Connecticut’s Ned Lamont still feels obliged to make regular obeisance to his party's left wing, which constitutes a majority of the party's activists. So last week the governor posted on his social media channels a minute-long video encouraging businesses in states that are restricting abortion to relocate to Connecticut.

Connecticut, the governor said, is "family-friendly" and its liberal abortion law "respects" women.

The new abortion law in Texas is not just almost prohibitive but bizarre, delegating enforcement to civil lawsuits for damages. But it would not have been enacted if Texas was not full of women whose idea of respect includes protecting what they call the pre-born. The women of Texas are fully capable of getting the law repealed.

In the meantime, Connecticut's pitching businesses in Texas and other states restricting abortion is ridiculous, as is a similar appeal made to Texas businesses the other week by Chicago's economic-development agency, which placed an advertisement in the Dallas Morning News.

The Chicago agency's chief executive, Michael Fassnacht, told Bloomberg News: "We believe that the values of the city you are doing business in matter more than ever before." But of course the "values" of Chicago encompass scores of shootings and dozens of murders almost every weekend, while the "values" of Illinois include the country's worst insolvency.

Connecticut does not have the violent crime of Chicago, nor is Connecticut quite as insolvent as Illinois. Connecticut has advantages of climate, geography and culture. But in friendliness to business, Texas clobbers Connecticut and Illinois, having no corporate- and personal-income taxes while Connecticut and Illinois have both.

The Tax Foundation says the personal-tax burden in Connecticut and Illinois is above 10 percent but is only 7.6 percent in Texas. That is, Connecticut's personal-tax burden is almost a third higher than that of Texas.

Not surprisingly, Texas long has been gaining population relative to the rest of the country while Connecticut has been losing.

With such a differential in taxes, even Texas businesses opposed to the new abortion law might save so much money by staying put and not relocating to Connecticut that they could afford to pay for their employees to come to Connecticut for abortions every year.

No amount of the governor's pandering to his party's left wing will make Connecticut's high taxes "family-friendly."

Nevertheless, higher taxes well may be on the way for Connecticut, since the governor and Democratic leaders in the General Assembly seem inclined to revive in a special legislative session what they call the Transportation Climate Initiative. The plan would raise wholesale taxes on gasoline so the added burden wouldn't be as visible as the retail tax and would claim that the new revenue would be spent on transportation projects that reduce pollution.

But the state is already rolling in emergency federal money and billions more in federal "infrastructure" appropriations may arrive soon, so Connecticut hardly needs more gas tax money.

Raising gasoline taxes will be most burdensome to the poor and middle class even as inflation is already roaring and eroding their living standards. Further, it would be unusual if any money raised by state government in the name of transportation wasn't diverted.

With its taxes already so high, state government needs mainly to set better priorities.

xxx

Last week Governor Lamont announced with some pleasure that his administration will close another prison, the one in Montville, because the state's prison population is declining so much.

When the announcement was made four people had just been shot in separate incidents in Hartford over the Labor Day weekend, making nine shootings there for the previous week. There had just been four shootings in New Haven as well. The day before the prison announcement a Hartford man, a chronic offender, earned his 14th conviction and was sent back to prison.

The rise in violent crime and the failure to deter repeat offenders could make prison closings seem premature.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Leave him up

William Blackstone in glorious stainless steel in Pawtucket, R.I.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The bookish William Blackstone (1595-1675) (also called Blaxton) was an Anglican minister who might have been the first permanent white resident of what is now Rhode Island, moving down from Boston and settling in today’s Lonsdale section of Cumberland in 1635, the year before Roger Williams founded Providence. The Blackstone River and a bunch of other things around here are named for him.

In the future Cumberland, on the east bank of the river that would bear his name, the reclusive and apparently kindly and tolerant intellectual read, wrote, tended cattle, planted gardens, and cultivated an apple orchard; he came up with the first variety of American apples, the Yellow Sweeting. He called his home "Study Hill," and it was said to have the largest library in the English colonies at the time. Sadly, his library and house were burned down in 1675 during King Philip's War, the very bloody and destructive conflict between Native Americans and English colonists that lasted from 1675 to 1678 and changed the course of American history. Blackstone died in 1675, just before the outbreak of the conflict.

Consider that his friends included the Narragansett tribe chiefs Miantonomi and Canonchet and the Wampanoags’ Massasoit and Metacomet. Metacomet is also known as King Philip (to mark the friendly relations his father, Massasoit, had with the English), whose followers were the ones who destroyed Blackstone’s home.

But now some Narragansetts want a new stainless-steel sculpture of Blackstone at the corner of Roosevelt and Exchange streets in Pawtucket taken down. They’re trying to make him into some sort of symbol of the brutal white takeover of their lands and the vast suffering and death of Native Americans that accompanied the English colonialization of what the English named New England. But Blackstone is a pretty inaccurate example of white aggression!

It’s appropriate that his statue remain up, given his importance to the history of the region. It’s not as if this is a statue of the likes of the cruel slaveowner, and traitor, Robert E. Lee. Such works are best kept in museums. (There are no statues of Hitler in outdoor parks in Germany, despite his historical importance.)

And, yes, you could say that George Washington was a traitor to Britain and he owned slaves. But unlike Lee, he didn’t take up arms against “his country” to ally himself with a “country’’ whose central mission in its rebellion against the United States was the preservation and indeed expansion of slavery. And Washington, whose slaves were freed at his death under his will, also was not considered a cruel slaveowner.

Anyway, why not see if a statue of a Native American chief from Blackstone’s time in Rhode Island could be commissioned to be put up near Blackstone’s? It would be culturally healthy if we had a wider range of historical figures represented by our public statues.

Here’s a nice crisp biography from the Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame:

http://www.riheritagehalloffame.org/inductees_detail.cfm?iid=45

David Warsh: Prepare for multigenerational contest between China and the West

China’s national emblem

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

China is building missile silos in the Gobi Desert. The U.S. has agreed to provide nuclear-submarine technology to Australia, enraging the French, who are building a dozen diesel subs that they had expected to sell to the Aussies. Xi Jinping last week rejected Joe Biden’s suggestion that the two arrange a face-to-face meeting to discuss their differences. Clearly, the U.S. “pivot” to the Pacific is well underway. Taiwan is the new hotspot, not to mention the Philippines and Japan.

The competition between China and the West is a contest, not a cold war. Financial Times columnist Philip Stephens was the first in the circle of those whom I read to make this point. “The Soviet Union presented at once a systemic and an existential threat to the West,” he wrote. “China undoubtedly wants to establish itself as the world’s pre-eminent power, but it is not trying to convert democracies to communism….” The U.S. is not trying to “contain” China so much as to constrain its actions. He continued,

Beijing and Moscow want a return to a nineteenth century global order where great powers rule over their own distinct spheres of influence. If the habits and the institutions created since 1945 mean anything, it has been the replacement of that arrangement with the international rule of law.

I’m not quite sure what Stephens means by “the international rule of law.” The constantly changing Western traditions of freedom of action and thought? Is it true, as George Kennan told Congress in 1972, that the Chinese language contains no word for freedom? Is it possible that Chinese painters produced no nudes before the 20th Century?

The co-evolution of cultures between China and the West has been underway for 4,000 years, proceeding at a lethargic pace for most of that time. While the process has recently assumed a breakneck pace, it can be expected to continue for many, many generations before the first hints of consensus develop about a direction of change.

A hundred years? Three hundred? Who knows? Already there is conflict. There may eventually be blood, at least in some corners of the Earth. But the world has changed so much since 1945 that “cold war” is no longer a useful apposition. The existential threat today is climate change.

China’s cultural heritage is not going to fade away, as did Marxist-Leninism. The script of that drama, written in Europe in the 19th Century, has lost much of its punch. Vladimir Putin has embraced the Russian Orthodox Church as a source of moral authority. Xi Jinping has evoked the egalitarian idealism of Mao Zedong in cracking down on China’s high-tech groups and rock stars, and strictly limiting the time its children are allowed to play video games.

But what is the Western tradition of “rule of law” that presumes to become truly international, eventually? Expect an answer some other day. Meanwhile, I’m cooking pancakes for my Somerville grandchildren.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first appeared.

Exploring urban ‘nonspace’

“Terrain Vague” (oil on canvas), by David Barnes, in his show of the same name at Atelier Newport (R.I.), Sept. 25-Oct. 30.

Mr. Barnes explains:

"Spanish architect Ignasi de Solà-Morales refers to Terrain Vague as the ‘in- between’ spaces on the urban outskirts: parking lots, empty plots, abandoned buildings and all the uninhabited sprawl beyond the city limits that makes up a sort of urban nonspace. I chose this title for my show because much of my work deals with this type of space. Not only physical terrain vague, but also psychological and spiritual places of uncertainty.

“As de Solà-Morales states, there is a ‘relationship between the absence of use, of activity, and the sense of freedom, void as absence, and yet also as promise, as encounter, as the space of the possible yet also as promise, as encounter….’’

So get to it!

At top, “Dewey, Cheetham & Howe,” the gag name for Car Talk’s headquarters in Harvard Square.

“You will never have more energy or enthusiasm or brain cells than you have today.’’

— Ray Magliozzi (born 1949), who, with his brother Tom (1937-2014), hosted the very popular Car Talk series on NPR.

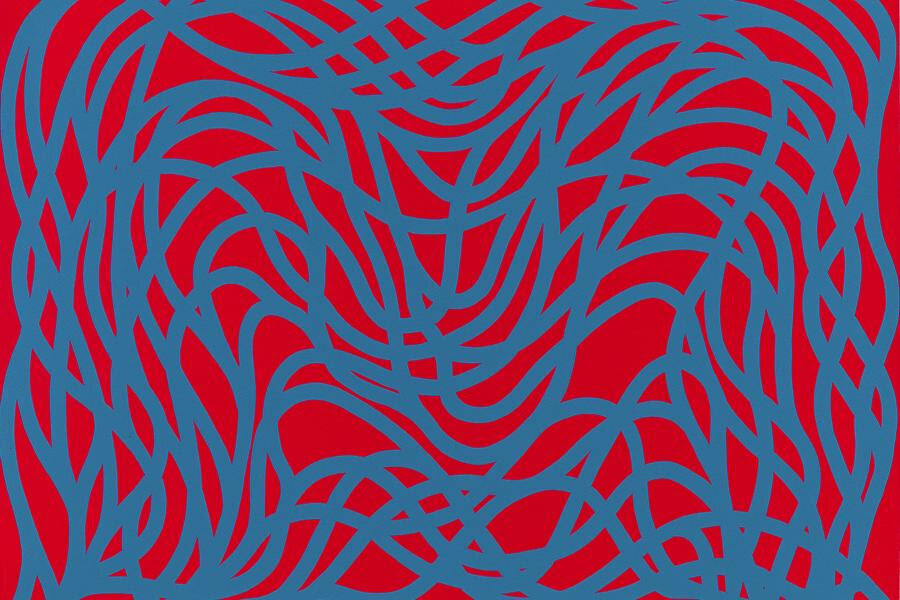

No, not the Boston street map

“Loopy Doopy, Blue/Red’’ (detail), (color woodcut), by Sol LeWitt, in his show “Strict Beauty: Sol LeWitt Prints,’’ through Jan. 9 at the New Britain (Conn.) Museum of American Museum.

Llewellyn King: We're living in an earthquake

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I have been in only one earthquake. It was in Izmir, Turkey, in 2014. The earth moved, undulating under my feet. Buildings shook and people’s fear could be felt.

Americans have reason to believe they are in a societal earthquake of unknown intensity or long-term consequence. Everywhere the earth we have known and trusted — political, social, economic, technological, and international — seems to be moving. Institutions are shaking, technology is obliterating the familiar; new and disturbing politics is rampant, left and right; and palpable climate change has arrived.

Our foreign skill set has been found wanting. Fear for the future is resident in our consciousness.

Our politics may be the most shaken of our intuitions. What we used to know how to do — like conduct an election — is in question and the fixes, as in conservative-introduced voting bills, threaten what we have held to be secure, those very elections. Electoral results are widely distrusted in a way they never have been previously.

We used to think we knew how to educate children. Now, that is in doubt as political factions fight over the curriculum, to say nothing of masks for children. To quote a vintage ad, “What’s a mother to do?”

The COVID-19 virus continues its ravages, reduced but not vanquished. It has left its mark: It has reshaped work and play to an extent we don’t yet understand. There are jobs, at least 10 million, going begging and workers who don’t want those jobs. They range from demand for drivers and warehouse personnel, reflecting the revolution in shopping, to airport workers, hospital staff, and, of course, restaurants.

Even the aerospace industry is begging. The Northrop Grumman plant in Maryland has a huge banner facing the Amtrak tracks seeking new hires.

It is a great time to change careers, obviously.

We don’t know whether work-at-home regimes will stay or whether the human need to congregate will win out. Do you move far from the office or wait out the phenomenon?

Technology controls our lives, and that isn’t always easy to live with. Try talking to any airline, insurance company, bank, or state agency and you will need a thorough familiarity with computers because the person on the line, or the recording, wants you off the telephone and online. This, even if you called because you were stymied online, to begin with.

If you get to a human, usually in Asia, that soul likely won’t have the advantages which come with having English as a first or second language. Hard-to-reach firms’ biggest asset isn’t, as they used to say, you, the customer. You don’t count to any large organization. Stop complaining and wait for a “customer-care representative,” who will tell you to get lost after you’ve waited for hours. You are now an insignificant part of mega-data, which some in the data business have called the new oil. Some corporate websites don’t publish a phone number. Don’t bother the tranquility of the C-suite.

The poor, who should be the beneficiaries of the new technologies, are victims. Take the unbanked: That large number of people who don’t have credit cards or a bank account. They can’t get rides from Uber or Lyft, and taxis are almost completely absent from city streets.

The unbanked can’t, should they be able to afford it, check into a hotel without plastic, or make a reservation for tickets to travel or go to a concert. They are non-members of society. They are on the wrong side of the digital divide — and that is a bleak place to be. Theirs are the children who got no education during the lockdowns and who will suffer through all their lives as a result. If you miss the techno train, you walk along tracks behind it.

The rise of China has damaged our self-esteem and we fear we are looking into the chasm of cold war or worse. Likewise, the calamitous end of our time in Afghanistan has further weakened our faith in our ability to get it right. (Heck, even “Jeopardy” can’t pick a host.) Our intelligence agencies seem to have totally failed, and our military doesn’t appear to be the winning institution we have been so proud of for so long.

After an earthquake, nations rebuild the structures. We need to start rebuilding with our institutions, and first among those is buttressing the democratic system. An invincible voting rights act would be a good starting place.

Our democracy hasn’t fallen yet, but it is shaking as the ground shifts under it.

Llewellyn King is executive producer of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C., and his email is llewellynking1@gmail.com

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

'Saucy' city and yet important?

The generally detested Brutalist Boston City Hall

“You know, Boston people are full of sauce.”

– Ellen Pompeo (born in 1969 in the Boston inner suburb of Everett), American actress and producer

“Boston is actually the capital of the world.”

— John Krasinski (born 1979 in Boston), American actor, director and producer

There’s always urban renewal

“Re-visioning Babylon” (archival inkjet), by Julee Holcombe, in the group show “The Artists Revealed: 2021 Studio Faculty Review”, at the University of New Hampshire Art Museum, Durham, through Dec. 10.

John O. Harney: N.E.’s changing ethnic demographics; shrinking police forces; honorary degrees and culture wars

1. Northwest Vermont 2. Northeast Kingdom 3. Central Vermont 4. Southern Vermont 5. Great North Woods Region 6. White Mountains 7. Lakes Region 8. Dartmouth/Lake Sunapee Region 9. Seacoast Region 10. Merrimack River Valley 11. Monadnock Region 12. North Woods 13. Maine Highlands 14. Acadia/Down East 15. Mid-Coast/Penobscot Bay 16. South Coast 17. Mountain and Lakes Region 18. Kennebec Valley 19. North Shore 20. Metro Boston 21. South Shore 22. Cape Cod and Islands 23. South Coast 24. Southeastern Massachusetts 25. Blackstone River Valley 26. Metrowest/Greater Boston 27. Central Massachusetts 28. Pioneer Valley 29. The Berkshires 30. South Country 31. East Bay and Newport 32. Quiet Corner 33. Greater Hartford 34. Central Naugatuck Valley 35. Northwest Hills 36. Southeastern Connecticut/Greater New London 37. Western Connecticut 38. Connecticut Shoreline

BOSTON

From The New England Journal of Higher Education (NEJHE), a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Population studies. The U.S. Census Bureau released new population counts to use in “redistricting” congressional and state legislative districts. Delayed by the pandemic, the counts came close to the legal deadlines for redistricting in some states, raising concerns about whether there would be enough time for public input.

The U.S. population grew 7.4% in 2010-2020, the slowest growth since the 1930s, according to the bureau. The national growth of about 23 million people occurred entirely of people who identified as Hispanic, Asian, Black or more than one race.

The Associated Press reported:

The population under age 18 dropped from 74.2 million in 2010 to 73.1 million in 2020.

The Asian population increased by one-third over the decade, to stand at 24 million, while the Hispanic population grew by almost a quarter, to top 62 million.

White people made up their smallest-ever share of the U.S. population, dropping from 63.7% in 2010 to 57.8% in 2020. The number of non-Hispanic white people dropped to 191 million in 2020.

The number of people identifying as “two or more races” soared from 9 million in 2010 to 33.8 million in 2020, accounting for about 10% of the U.S. population.

A few New England snippets

Maine remains the nation’s oldest and whitest state, even though it saw a 64% increase in the number of Blacks from 2010 to 2020, as well as large increases in the number of Asians and Pacific Islanders.

Connecticut’s population crawled up 0.9% over the decade from 2010 to 2020 to 3,605,944 residents. The number of residents who are Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) increased from 29% of the population in 2010 to 37% in 2020. Connecticut’s number of congressional seats won’t change, but district borders will.

The total population of the only city on Boston’s South Shore, Quincy, Mass., topped 100,000 (at 101,636), as its Asian population grew to represent nearly 31% of all residents. Further south, the city of Brockton’s population increased by nearly 13% as the white population dropped by 29%, and the Black population increased by 26%.

Amazon jungle. Amazon last week announced it will pay full college tuition for its 750,000 U.S. hourly employees, as well as the cost of earning high school diplomas, GEDs, English as a Second Language (ESL) and other certifications. While collecting praise for its educational goodwill, stories of dire conditions in the e-commerce giant’s workplace also triggered a new California law that would ban all warehouses from imposing penalties for “time off-task” (which reportedly discouraged workers from using the bathroom) and prohibit retaliation against workers who complain.

Police shrink. Police forces in New England have recently felt new recruitment and retention pressures. In August 2021, The Providence Journal ran a piece headlined “Promises made, promises delivered? A look at reforms to New England police departments.” GoLocal reported that month that Providence policing staff levels stood at 403, down from 500 or so in the 1980s under then-Mayor David Cicilline. The number of officers employed by Maine’s city and town police departments and county sheriffs’ offices shrank by nearly 6% between 2015 and 2020, according to the Maine Criminal Justice Academy. Reporter Lia Russell of the Bangor Daily News noted, “It’s also a challenge that police in Maine are far from alone in facing, especially following a year during which police practices across the nation were called into question following the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police Officer Derek Chauvin.” The Burlington, Vt., City Council in August defeated efforts to reverse a steep cut in city police ranks. The police department currently has 75 sworn officers, down from 90 in June 2020. A survey by the police officers’ union found that roughly half of Burlington cops were actively seeking employment elsewhere.

Honor roll. Honorary degrees are becoming something of a frontline in the culture wars. Springfield College alumnus Donald Brown, who recently coauthored a piece for NEJHE, tells of his alma mater revoking the honorary master of physical education degree it had bestowed on U.S. Olympic Committee Chair Avery Brundage in 1940. In 1968, Brundage pressured the U.S. to take action against two Olympic athletes who gave the Black Power salute after finishing first and second in the 200 meters. That event was only the tip of the iceberg. Brundage had a history of anti-semitism, sexism and racism. Springfield President Mary-Beth Cooper met with the trustees and others and decided to take back the honor. Meanwhile, the University of Rhode Island has been tying itself in knots over the honorary degree it bestowed on Michael Flynn in 2014, before he was appointed Trump’s national security adviser and accused of sedition.

Refugees. After the U.S. ended its longest war (so far) in Afghanistan and the capital of Kabul fell, the question arose of where Afghan refugees would resettle. New England cities, including Worcester, Providence and New Haven, are among those that have readied plans to welcome Afghan refugees. In higher education, Goddard College President Dan Hocoy said it was a “no-brainer” to offer to house Afghan refugees at its Plainfield, Vt., campus for at least two months this upcoming fall. Back in 2004, NEJHE (then Connection) featured an interview with Roger Williams University President Roy J. Nirschel, who died in 2018, and his former wife Paula Nirschel on the university’s role in its community as well as their pioneering initiative to educate Afghan women.

Sunshine state. Before Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis took his most recent stand against fighting COVID, he displayed a narrow-mindedness that seems to always be in fashion. As Inside Higher Ed reported, after expressing concerns about faculty members “indoctrinating” students, DeSantis signed a law requiring that public institutions survey students, faculty and staff members about their viewpoint diversity and sense of intellectual freedom. The Miami Herald reported that DeSantis and state Sen. Ray Rodrigues, the original bill’s Republican sponsor, suggested that the results could inform budget cuts at some institutions. Faculty members have opposed the bill, which also allows students to record their professors teaching in order to file free speech complaints against them.

New colleges in a time of contraction. The nonprofit Norwalk (Conn.) Conservatory of the Arts announced plans to open a new performing-arts college and welcome its first class in August 2022. It’s unusual news amid the stream of college mergers and closures only widened by the pandemic. Among the challenges, many of the faculty members don’t have master of fine arts degrees that accrediting agencies require and, without accreditation, the college’s students won’t be eligible for federal financial aid or Pell Grants.

The Conservatory says the college will consolidate a traditional four-year undergraduate program into two years of intense training and a two-year graduate program into one year. Meanwhile, up the coast, the (Fall River, Mass.) Herald News reports that Denmark-based Maersk Training and Bristol Community College will work together to turn an old seafood packaging plant in New Bedford, Mass., into a National Offshore Wind Institute training facility to train offshore wind workers, complete with classrooms and a deepwater pool to train and recertify workers. (NEJHE has reported on the need to train talent for the burgeoning industry and the coastal economy’s special role in New England.)

Other higher-ed institutions are shapeshifting. After months of discussions and lawsuits, Northeastern University and Mills College reached agreement to establish Mills College at Northeastern University. Founded in 1852, Mills is renowned for its pre-eminence in women’s leadership, access, equity and social justice. Also, billionaire investor Gerald Chan and his family’s Morningside Foundation gave $175 million to the University of Massachusetts Medical School, which will be renamed the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School. That’s the largest-ever gift to the UMass system.

Land deals. I was recently struck by a report titled We Need to Focus on the Damn Land: Land Grant Universities and Indigenous Nations in the Northeast. The report was born of a partnership between Smith College students and the nonprofit Farm to Institution New England (FINE) to look at how land grant universities view their historic relationships with local Indigenous tribes and how food can play a role in repairing those relationships. It grabbed my attention, partly because NEJHE has published some interesting stories about Native Americans and New England higher education. (See Native Tribal Scholars: Building an Academic Community and A Different Path Forward, both by J. Cedric Woods and The Dark Ages of Education and a New Hope, by Donna Loring.) And partly because two NEBHE Faculty Diversity Fellows, professors Tatiana M.F. Cruz of Simmons University and Kamille Gentles-Peart of Roger Williams University, are spearheading a fascinating Reparative Justice initiative. Among other things, Cruz and Gentles-Peart have had the courage to remind us that land grant universities in New England occupy the land of Indigenous communities. The Smith-FINE work offered sensible recommendations: Financially support Native and Indigenous faculty, activists, programs on campuses and beyond; offer free tuition for Native American students; hire Indigenous people, and fund their research.

John O. Harney is executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

‘The company way’

Amazon fulfillment center in San Fernando de Henares, Spain

— Photo by Álvaro Ibáñez

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Amazon wants to build a gigantic, nearly 4-million-square-foot distribution center on 195 acres off Route 6 in Johnston, whose leaders seem to love the idea, even with the 20-year property-tax break involved. After all, there would purportedly be 1,500 full-time jobs (at least until more Amazonian automation eliminates some of them), and the enterprise is offering some specific goodies to Johnston and the state as sweeteners, though they’re minuscule considering the profit that the company would make from this huge operation in densely populated and generally prosperous southern New England.

This project would mean hundreds of tractor-trailer trips in and out of this behemoth every day, and so the area’s traffic and the environment (lots of fragrant truck exhaust!) would, to say the least, be affected big time, and probably so would be the region’s small retailers, who would find it even harder to compete with the Amazon octopus as it gets more stuff to local customers even faster.

But, hey, all those jobs! And the facility would be good news for southeastern New England’s many fine orthopedic surgeons and physical therapists since Amazon is well known for its high rates of worker injuries suffered as a result of its grueling work demands enforced via Orwellian surveillance.

Here’s an interesting Amazon controversy that folks around here might want to read.

“A: I play it the company way

Where the company puts me, there I'll stay.

B: But what is your point of view?

A: I have no point of view!

Supposing the company thinks... I think so too!’’

-- From “The Company Way,’’ in How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying, by Frank Loesser (1910-1969), Broadway lyricist and composer.

Place and a state of mind

“Maine Coast,’’ by Winslow Homer (1896). The site is Prout’s Neck.

“My New England is both a place and state of mind, sometimes hard to fathom, but rarely boring; it is a rugged symphony of rocky pastures and choppy birch-clad hills where partridges sun and deer flaunt white flags; it is a cold, immortal sea crashing against a coast steeped in tradition.’’

— Frank Woolner, in My New England

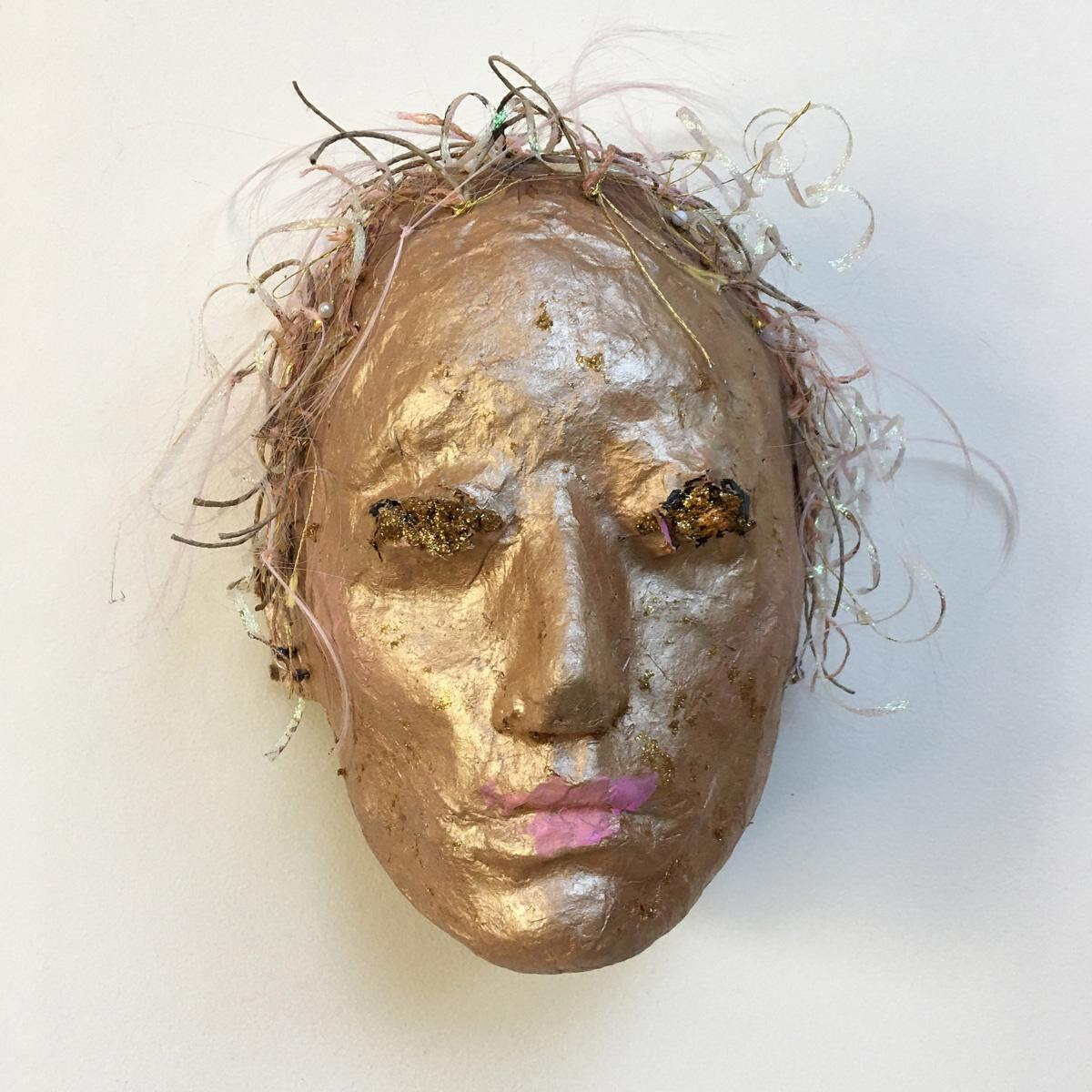

Beyond makeup

“Shedding” (mixed media), by Christine Palamidessi, in her show “The Future Has an Ancient Face,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, for month of October.

The gallery explains:

“In 2020, Christine Palamidessi called on the Goddess Nike, the embodiment of Victory, to make a comeback. ‘Who are the warriors, the champions, and what challenges are they fighting?’ the goddess asked. ‘Pandemic. Politics. Conspiracies,’ the artist answered. Nike handed Palamidessi her face, ‘Use it,’ she said.

“The artist used Nike’s face as a container to make masks that embody a swirl of words and emotions: Wuhan, Shedding, Lockdowns, Culture Cancelling, Recounts. She painted, stitched, bejeweled and wrote on the masks; some are frightening and others make us smile. Each reminds us we survived something hard: we entered a world that was interrupted and have the opportunity to create a different, more humane way of life -- a life without masks.’’

Don Pesci: The body count in New Haven

New Haven from the south, with The Hill in the foreground. East Rock is visible in the background

— Photo by Emilie Foyer

VERNON, Conn.

Paul Bass of the New Haven Independent is keeping a body count.

From January to March alone, the publication notes, “Alfreda Youmans, 50, and Jeffrey Dotson, 42, were found dead by the police inside a Winthrop Avenue apartment, Jorge Osorio-Caballero, 32, was shot and killed in Fair Haven, Marquis Winfrey, 31, was shot and killed in Newhallville, and Joseph Vincent Mattei, 28, was shot and killed in the Hill. Someone shot Kevin Jiang, 26, to death in Goatville on Feb. 6. Angel Rodriguez, 21, was shot to death in Fair Haven in mid-February, his body dumped by the Mill River in East Rock. Dwaneia Alexandria Turner, 28, was shot to death in the Hill on March 16 during an argument with two other women.”

And the year’s total body count so far for the city that has given us Yale, two nationwide recognized pizza houses, the inimitable Roger Sherman, and William Celentano, a funeral director and the first Italian-American mayor of New Haven -- indeed, the last Republican mayor elected in New Haven 68 years ago – is 21.

“There have been 21 homicides in New Haven this year,” NBC Connecticut reports. “Twenty murders were reported citywide in 2020, according to statistics from the New Haven Police Department” – and we have about 3 months left to close out the year.”

It promises to be a record year, not only for new Haven but for all major cities in Connecticut.

The New Haven Independent, whose reporting on murders in New Haven has been more granular than some might wish, tells us the latest shooting victim is Trequon Lawrence, 27 years old, employed by Yale New Haven Hospital, and a new home owner.

“I purchased my first multi-family dwelling,” Lawrence wrote on Facebook. “Truly blessed and highly favored. Yet this is a bitter sweet time in my life. As some of you may know I lost my baby girl a few weeks back. And in all honesty she was my motivation for buying the house. When she left a piece of me left with her. Nonetheless I still had to make this move toward putting my family in a better position. In life we will experience many highs and many lows. But without the lows we can’t truly appreciate the highs. I am GRATEFUL overall and will continue to strive for greatness in light of my daughter.”

Lawrence was shot eight times. The shooting occurred, the publication noted, “down the street from the home of state Sen. Gary Winfield,” who “observed afterwards that the police department has not been giving the public much information about what’s behind this year’s flood of shootings.”

Contacted for comment by the publication, Winfield said, “My experience over a couple of decades is that you don’t get the intimate details of the shooting itself. But you get, ‘This is what we’re seeing. We’re seeing these are isolated incidents.’ Or: ‘They’re related to gangs or cliques’ …. You get some kind of trending information to give some sense of what is actually happening,’ Winfield said.”

Sure, sure. The causes of shootings in New Haven this year are not materially different than the previous year, and the year before that, and the two decades before that.

Even so, the accumulative data apparently is not sufficient to allow the General Assembly to remediate city shootings through legislation.

“While the police need to keep certain details about individual shootings confidential while they investigate,” the publication noted, “in the past they have communicated more about what’s behind outbreaks of violence, Winfield said. He argued that officials and the community can’t craft an effective response without more information.”

The notice posted on Dante’s Gates of Hell was, “Abandon hope, all ye who enter here.” Things are not quite that bad in New Haven. The state delegation, Winfield said, has “reached out to the mayor to have a conversation about what has been going on. In order to tackle the problem we need to know what is actually happening. People in the city have fear. Some of that is born from what is going on. Some of that is born from a lack of information.”

New Haven has had a surfeit of insouciant Democrat politicians over the last 60 years, but Winfield’s indifference to a murder in his city that occurred “down the street from his home” is a high bar to surmount.

Whatever can Winfield mean when he says he lacks the proper data from New Haven police to fashion an answering piece of legislation – other than that legislation for which Winfield is best known: a bill that withdraws from all police officers in the state a partial immunity from suits that would allow plaintiffs to seize the personal assets of police officers in Connecticut? The removal of protective immunity in Winfield's signature bill, some have argued, likely contributed to a drop-off in urban police recruitment, and a flight from urban areas to the suburbs by city police officers, this at a time when New Haven’s murder rate is growing by leaps and bounds.

Following an affirmative vote on the Winfield bill, police chiefs warned, “There is not and cannot be an alternative to this for any police officer or agency. We strongly believe that the loss of qualified immunity will destroy our ability to recruit, hire, and retain qualified police officers both now and in the foreseeable future. We are also very concerned about losing our current personnel at a higher rate than we normally can replace. Any impact on our ability to recruit qualified personnel in general will also impact our minority recruitment efforts, which is a goal in this bill that we strongly support.”

Any of the survivors of the relatives of victims listed by the New Haven Independent in its granular coverage of New Haven murders doubtless would appreciate a clear answer to the above question?

Surely it is the greater part of Winfield’s obligation as a state senator to fix his attention on murders that occur right under his nose and to propose legislative fixes that really do fix the problem.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

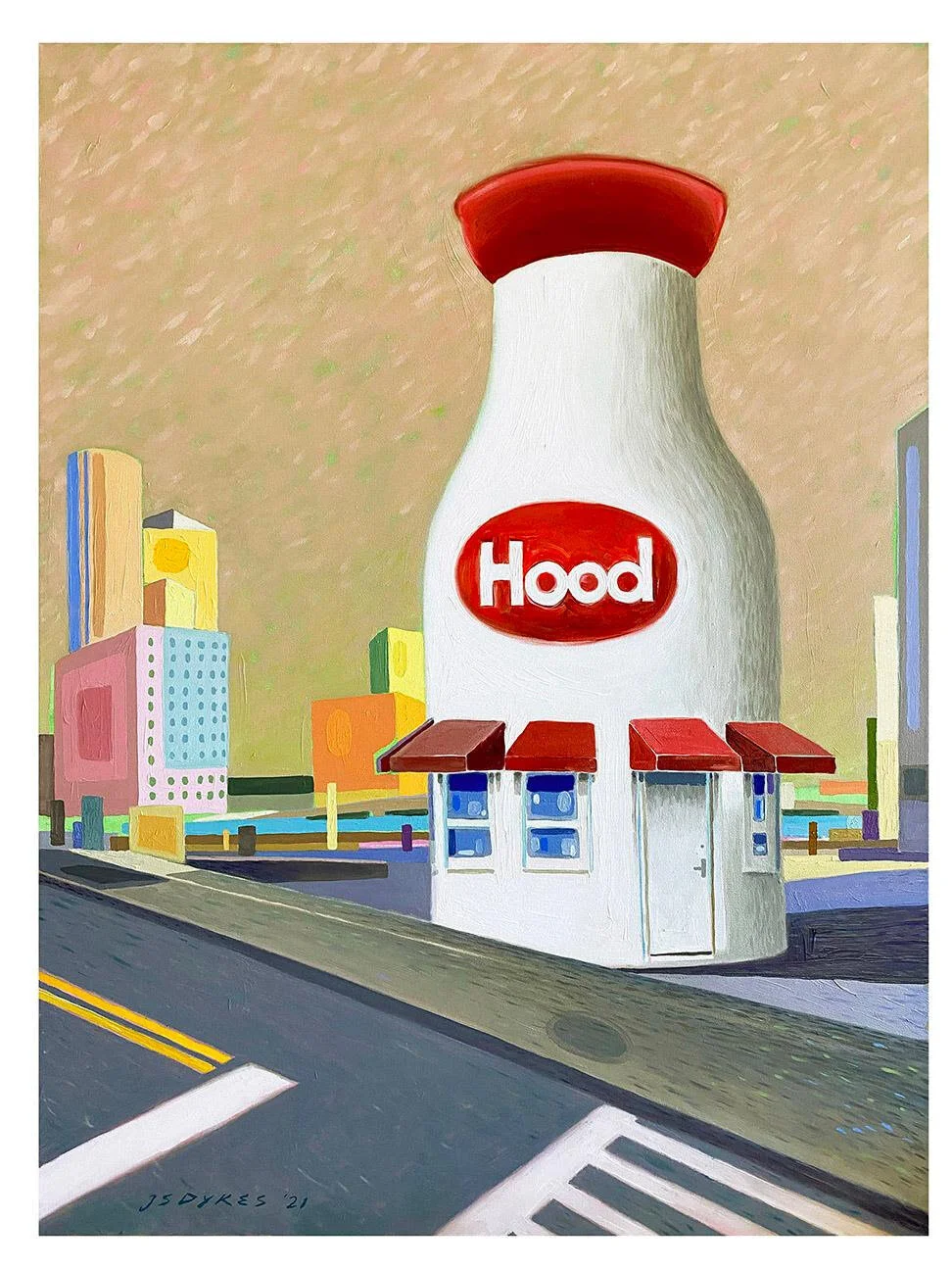

Got milk?

“Milk Bottle,’’ by John S. Sykes, in his show at The Gallery at 249 A Street, Boston, through Sept. 14. The show is inspired by mid-20th Century advertising. H.P. Hood for years has been the dominant New England dairy company. It was founded in 1846 in Lynnfield, Mass., and is now based in the Charlestown section of Boston.

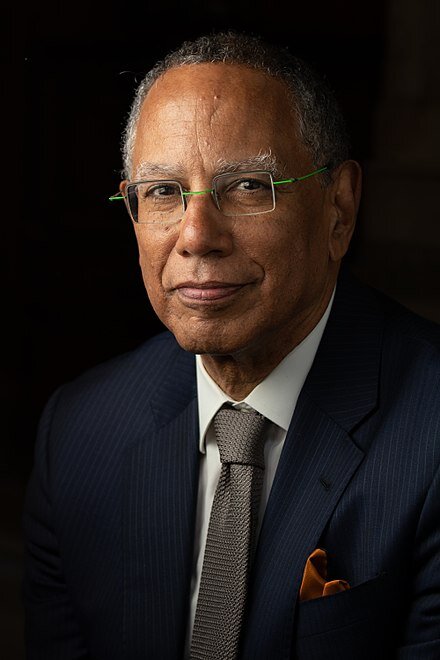

David Warsh: Of sportswriters, race and great news publications

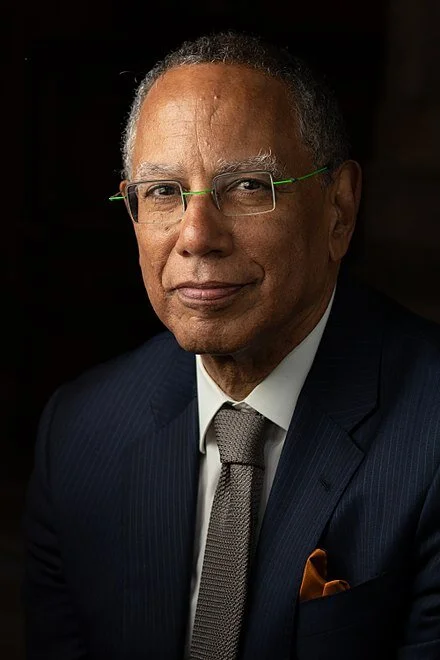

New York Times executive editor Dean Baquet

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Because it was August, I was reading Tall Men, Short Shorts, the 1969 NBA Finals: Wilt. Russ. Lakers. Celts, and a Very Young Sports Reporter (Doubleday, 2021). Leigh Montville was one of the many excellent sports columnists at The Boston Globe in the twenty years that I was there, somebody whom I always read no matter who or what he was writing about. After he was unreasonably refused an exit as columnist from the ghetto of sports, he left the paper for Sports Illustrated, where he wrote extended features and the back-of-the-magazine column for many years. He wrote eight books along the way. Tall Men, Short Pants is his ninth, a summing-up of much he learned about life in a fifty-year career as a journalist.

I’d been alerted to the book by The Globe’s former long-time managing editor, Thomas F. Mulvoy, who wrote about it in the Dorchester Reporter. At one point, Mulvoy says:

In a section that comes off the page with a sharp edge of sadness, Montville redresses himself (for the umpteenth time, his words suggest) for his silence at the press table when the Celtics played the Knicks in New York earlier in the season. A Globe colleague sitting next to him gave vent to his bigotry by loudly and repeatedly using the N-word while talking about the game being played in front of them. [Montville] writes: “I have thought for all these years of the things I should have done. I should have told [him] to shut up. Right away, I should have done that. If he didn’t shut up, I should have grabbed him, done something. … I should have reported all this to someone at the Globe on our return. I should have decided never to talk to him again. I should have done any of this stuff. I did nothing”

The 26-year-old Montville, who is White, served as no more than witness that day – the book reveals how he learned that his Globe colleague was deliberately baiting another Globe sportswriter, a well-known liberal, nearby – only much later affording a glimpse of the fractious mood of the nation in 1969. Montville attended his colleague’s wake thirty years later. Otherwise, he imaginatively covered changing attitudes about race in America, in columns and books, including Manute: The Center of Two Worlds (2011), and Sting like a Bee. Muhammad Ali vs. the United States of America, 1966-1971 (2017). Sports has done more than its share, and better than Hollywood, to illuminate rapidly changing stereotypes of race and class in the last fifty years. Montville was alert to the story every step of the way.

Reading Tall Men, Short Pants brought into focus a project of The New York Times of which I gradually became aware over the last couple of years.

I do not mean the paper’s scrutiny of the killings of Black men and the occasional Black woman by Whites, mostly police officers, before George Floyd was murdered by Officer Derek Chauvin, in Minneapolis on May 25, 2020, though even now, thanks to the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2013, it seems important to remember their names.

(Those whose stories made the front pages include Trayvon Martin, in Sanford, Fla; Eric Garner, in Staten Island, New York; Michael Brown, in Ferguson, Mo.; Walter Scott, in North Charleston, S.C.; Philando Castile, in St. Paul; Stephen Clark, in Sacramento, and Breonna Taylor, in Louisville.

Nor do I mean the special issue of the magazine called The 1619 Project, the Times’s coverage of the debate over Critical Race Theory, or the series of essays by critic-at-large Wesley Morris that earlier this year was recognized with a Pulitzer Prize. I have in mind something less concrete but ultimately even more eye-opening, at least to me.

I am thinking of a surge of ordinary news stories about contributions to American culture by African-American citizens. These stories appeared in unusual numbers, day after day, over the course of the last eighteen months. In the trade, this kind of display is called ROP, or run of the paper, with stories placed anywhere in the paper at the option of an editor – world, U.S., politics, NY, business, opinion, tech, science, health, sports, arts, books, style, food, travel, real estate, obituaries. The surge was as unmistakable as it is difficult to describe. Instead of data, I have only personal experience of it, to which I aim to testify here, briefly.

I scan the print editions of The Times, The Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times each morning at home, glance online at Bloomberg and study the story list of The Washington Post when I reach the office. In the evening, I read and clip (or print) whatever is most important to me. The differing trajectories of these five great English-language news organizations in the thirty years since the Internet emerged as a public communications medium has been fascinating, but that is a subject for another day. For now it is enough to say that The Times remains the most ambitious among them, more sparkling than ever in its aspirations.

It was the morning scanning of The Times that first produced the effect. So relentless had its coverage of Blacks newsmakers and their concerns become over the last year that one day it dawned on me what The Times had achieved. Some of the stories made big impressions. Others seemed peripheral, at least to my interests. I discussed the experience with my friend, Vincent McGee, who described it thus: “I first noticed it with obituaries, some current – mainly arts, music and sports – and others ‘catch ups’, often of Black women lost in history.”

By distorting its usual budget of stories – not much, mind you, this was only a surge – the newspaper’s editors had given me, a White reader, the feeling of somehow being unimportant. For some fleeting part of the day, I felt as many Black readers must feel most days, oppressed by the relentless attention The Times paid to the Other. This was showing, not telling, how it felt to be left out. It showed, too, what it meant to be included in. As an exercise in good newspaper editing, I will never forget it.

How had the decision to reorient the coverage been made? Anyone who knows anything about newspapers understands that inspiration comes from the bottom up. Orders are given, of course; stories are assigned, or turned back for more work. There are countless meetings, discussions, bull sessions, retreats. Word gets around. Better to say that a curiosity about race, gender, ethnicity and discrimination had been authorized at The Times as long ago as the Nineties, then encouraged, becoming wide-ranging, before coming to a low boil in 2020.

The Times’s executive editor is Dean Baquet, who was born in 1956. He is a consummate newspaperman, having started working in New Orleans even before graduating from Columbia University, in 1978. He moved from The Times-Picayune, in New Orleans, to the Chicago Tribune in 1984, where he won one Pulitzer Prize, and just missed another, before joining TheTimes, in 1990. Tribune Co. hired him back in 2000 to serve as managing editor of its newly acquired Los Angeles Times; he replaced John Carroll as editor in 2006 but was quickly dismissed after opposing newsroom budget cuts. He returned to The Times later that year as its Washington bureau chief, became its managing editor in 2011, and succeeded Jill Abramson in the top newsroom job in 2014.

Baquet is also a Black man, the fourth of five sons of a successful New Orleans restaurateur. Many years will be required to hash out all that has happened on his watch, some of it under the heading of “woke.” Baquet will write a book. Culture wars will continue. The equitable distribution of attention – of “play” – will become the next editor’s problem. Baquet turns 65 later this month; he will retire next year.

Leigh Montville won the Associated Press Sports Editors Red Smith Award in 2015; he never got out of the sportswriting ghetto, but he nevertheless became one of the finest columnists of his generation, pure and simple. Dean Baquet broke race out of the newspaper ghetto and made it ROP, maintaining news values evolved by the modern profession. He will enter history books as one of The New York Times’s greatest editors. Both men made the most of their opportunities.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

Maybe to Hell but at least moving

Silver Lake Railroad at center of Silver Lake village, part of Madison, N.H., where e.e. cummings (as he signed himself) had a weekend and summer place. He died at a hospital in nearby North Conway.

“America makes prodigious mistakes, America has colossal faults, but one thing cannot be denied: America is always on the move. She may be going to Hell, of course, but at least she isn't standing still.”

— E.E. Cummings (1894-1962), American poet and essayist. He was born in Cambridge, Mass., and is buried at Forest Hills Cemetery in Boston.

Joy Farm, also now known as the E.E. Cummings House, a National Historic Landmark

‘Adding and subtracting layers’

“Railroad Ties” (oil and cold wax on panel), by Helen Shulman, at Edgewater Gallery, Middlebury, Vt.

The gallery says:

“Helen Shulman’s abstract, mixed-media paintings draw on her interest in the manipulation of surface texture, color, and mark making, and are compositions that may have their origins in the landscape or the figure but become about the process of adding and subtracting layers, creating texture, and interest that will draw the viewer in and through each piece.’’

John Hancock gives employees 5 more days off

The three John Hancock buildings in Boston. The two older structures are reflected in the façade of the newest. The Stephen L. Brown building is the low, flat one.

BOSTON

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

“Boston-based John Hancock Life Insurance Co. and its parent company, Toronto-based Manulife Financial Corp., recently announced that it would be granting employees an additional five personal days. With the continuation of the COVID-19 pandemic, the company is taking this step in an effort help their employees stay both mentally and physically healthy.

“Along with the additional personal days, John Hancock employees have been taking part in ‘Fuel Up Fridays.’ These sessions are meant to give employees a chance to grow and help workers avoid burnout. This announcement came after CEO Marianne Harrison–named a 2020 ‘New Englander of the Year’ by The New England Council —informed the Boston area workers that the offices would not fully reopen their offices until January 2022.

“‘I know some of you were looking forward to being back in the office, so this news will be disappointing… However, we do feel this is the right choice for our colleagues’ well-being and in support of public health in the communities where we live and work,’ wrote Harrison in an email to employees.’’

Lindsay Koshgarian: The wasted opportunities since 9/11

Flight paths of the 9/11 murderers

Via OtherWords.org

NORTHAMPTON, Mass.

Twenty years have now passed since 9/11.

The 20 years since those terrible attacks have been marked by endless wars, harsh immigration crackdowns and expanded federal law enforcement powers that have cost us our privacy and targeted entire communities based on nothing more than race, religion, or ethnicity.

Those policies have also come at a tremendous monetary cost — and a dangerous neglect of domestic investment.

In a new report I co-authored with my colleagues at the National Priorities Project at the Institute for Policy Studies, we found that the federal government has spent $21 trillion on war and militarization both inside the U.S. and around the world over the past 20 years. That’s roughly the size of the entire U.S. economy.

Even while politicians have written blank checks for militarism year after year, they’ve said we can’t afford to address our most urgent issues. No wonder these past 20 years have been rough on U.S. families and communities.

After often strong growth from 1970 to 2000, household incomes have stagnated for 20 years as Americans struggled through two recessions in the years leading up to the pandemic. As pandemic eviction moratoriums end, millions are at risk of homelessness.

Our public-health systems have also been chronically underfunded, leaving the U.S. helpless to enact the testing, tracing, and quarantining that helped other countries limit the pandemic’s damage. Over 650,000 Americans have died from COVID-19 — the equivalent of a 9/11 every day for over seven months. The opioid epidemic claims another 50,000 lives a year.

Meanwhile, such extreme weather events as wildfires, hurricanes and floods have grown in frequency over the past 20 years. The U.S. hasn’t invested nearly enough in either renewable energy or climate resiliency to deal with the increasing effects climate change has on our communities.

In the face of all this suffering, it’s clear that $21 trillion in spending hasn’t made us any safer.

Instead, the human costs have been staggering. Around the world, the forever wars have cost 900,000 lives and left 38 million homeless — and as the disastrous withdrawal from Afghanistan has shown us, they were a massive failure.

Our militarized spending has helped deport 5 million people over the past 20 years, often taking parents from their children. The majority of those deported hadn’t committed any crime except for being here.

And it has paid for the government to listen in on our phone calls and target communities for harassment and surveillance without any evidence of crime or wrongdoing, eroding the civil liberties of all Americans.

Fortunately, there’s a silver lining: We’ve found that for just a fraction of what we’ve spent on militarization these last 20 years, we could start to make life much better.

For $4.5 trillion, we could build a renewable, upgraded energy grid for the whole country. For $2.3 trillion, we could create 5 million $15-an-hour jobs with benefits — for 10 years. For just $25 billion, we could vaccinate low-income countries against COVID-19, saving lives and stopping the march of new and more threatening virus variants.

We could do all that and more for less than half of what we’ve spent on wars and militarization in the last 20 years. With communities across the country in dire need of investment, the case for avoiding more pointless, deadly wars couldn’t be clearer.

The best time for those investments would have been during the past 20 years. The next best time is now.

Lindsay Koshgarian directs the National Priorities Project at the Institute for Policy Studies. She’s the lead author of the new report “State of Insecurity: The Cost of Militarization Since 9/11’’. She lives in Northampton.

On the Connecticut River in Northampton