David Warsh: America’s fracturing ‘politics of purity’ since the ‘70s

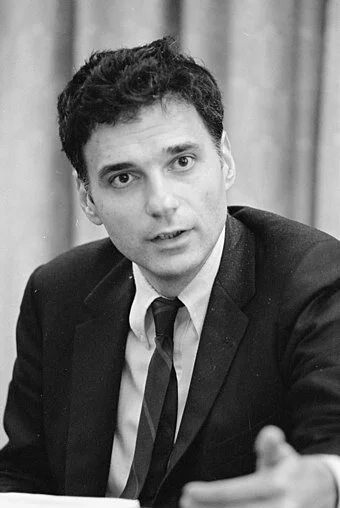

Ralph Nader in 1975, in his heyday

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Like a lot of people, I am interested in what has been happening in the world, the U.S. in particular, since the end of World War II. I am especially intrigued by goings on in university economics, but I take a broad view of the subject. I grew up in the Fifties, and the single most persuasive account I’ve found of the underlying nature of changing times since 1945 has been a series of five books by historian Daniel Rodgers, of Princeton University. In Age of Fracture (Belknap, Harvard, 2011), Rodgers described very well my experience of the increasingly thinner life of things.

Across the multiple fronts of ideational battle, from the speeches of presidents to books of social and cultural theory, conceptions of human nature that in the post-World War II era had been thick with context, social circumstance, institutions, and history gave way to conceptions of human nature that stressed choice, agency, performance and desire. Strong metaphors of society were supplanted by weaker ones. Imagined collectivities shrank; notions of structure and power thinned out. Viewed by its acts of mind, the last quarter of the century was an era of disaggregation, a great age of fracture.

But I’m always interested in a new narrative. One such is Public Citizens: The Attack on Big Government and the Remaking of American Liberalism (Norton, 2021), by historian Paul Sabin, of Yale University. Sabin employs the career of Ralph Nader, the arc of which extends from Harvard Law School and auto-safety crusader in Sixties to his Green Party candidacy in the U.S. presidential election of 2000, as a metaphor for a variety of other liberal activists who mounted assaults of their own on centers of government power in the second half of the 20th Century.

The harmonious post-war partnership of business, labor and government proclaimed in the Fifties by economist John Kenneth Galbraith and New Dealer James Landis, symbolized by the success of the Tennessee Valley Authority’s government-sponsored electrification of the rural South, was not built to last. But how did government go from being the solution to America’s problems to being the cause of them? It was more complicated than Milton Friedman and Ronald Reagan, Sabin shows.

Jane Jacobs (The Death and Life of Great American Cities, 1961), Rachel Carson (Silent Spring, 1962) and Nader (Unsafe at Any Speed. 1965), were exemplars of a new breed of critics of capture industrial manipulation and capture of government function, Sabin writes. Jacobs attacked large-scale city planning and urban renewal. Carson exposed widespread abuses by the commercial pesticide industry. Nader criticized automotive design. These were only the first and most visible cracks in the old alliance of industries, labor unions and federal administrative agencies. Public-interest law firms began springing up, loosely modeled on civil-rights organizations. The National Resources Defense Council; the Conservation Law Foundation; the Center for Law and Social Policy and many other start-ups soon found their way into federal courts. Nader tackled the leadership of the United Mineworkers Union, leading then-UMW President Tony Boyle to order the murder of reform candidate Tony Yablonski, his wife, and daughter, on New Year’s Eve, 1969.

In Age of Fracture, Rodgers wrote that “The first break in the formula that joined freedom and obligation all but inseparably together began with Jimmy Carter.” Carter’s outside-Washington experience as a peanut farmer and Georgia governor, as well as his immersion in low-church Protestant evangelical culture led him to shun presidential authority. “Government cannot solve our problems, it can’t set our goals, it cannot define our vision,” he said in 1978.

Sabin takes a similar view but offers a different reason for the rupture. Caught in between the idealistic aspirations of outside critics inspired by Nader and the practical demands of governing by consensus, Carter struggled to maintain the traditional balance but failed to placate his critics. “Disillusionment came easily and quickly to Ralph Nader,” Sabin writes. “I expect to be consulted, and I was told that I would be,” Nader complained almost immediately. Reform-minded critics attacked Carter from nearly every direction. A fierce primary challenge by Sen. Edward M. Kennedy (D.-Mass.) failed in 1980. The stage was set for Ronald Reagan.

Sabin recalls the battles of the 1970s with grim determination to show the folly of politics of purity. Nader made his first run for the presidency as leader of the Green Party in 1996, challenging Bill Clinton and Bob Dole. He was in his sixties; his efforts were half-hearted. In his second campaign, in 2000, he campaigned vigorously enough to tip the election to George W. Bush. Even then it wasn’t Nader’s last hurrah. He ran again, in 2004, as candidate of the Reform Party; and a fourth time, as an independent, in 2008. At 87, he is today conspicuously absent from the scene.

The public-interest movement initiated by urbanist Jane Jacobs, scientist Rachel Carson and Ralph Nader was effective in its early stages, Sabin concludes. The nation’s air and water are cleaner; its highways and workplaces safer; its cities more open to possibility. But Sabin is surely right that all too often, go-for-broke activism served mainly to undermine confidence in the efficacy of administrative government action among significant segments to the public.

The critique of federal regulation was clearly not the whole story, any more than was The Great Persuasion, undertaken in 1948 by the Mont Pelerin Society, pitched unsuccessfully in 1964 by presidential candidate Barry Goldwater, and translated into slogans in 1980 by Milton and Rose Friedman. Nor is the thoroughly disappointing 20-year aftermath to 9/11, another day when the world seemed to many to “break apart,” as historian Dan Rodgers put it in an epilogue to Age of Fracture.

What might put it back together? Accelerating climate change, perhaps. But that’s another story.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first appeared.

'Stay and wonder'

The Rudyard Kipling House is a Shingle Style house on Kipling Road in Dummerston, Vt., a few miles outside Brattleboro. The house was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1993 for its association with the English author Rudyard Kipling (1865–1936), who had it built in 1893 and made it his home until 1896. It is in this house that Kipling wrote Captains Courageous, The Jungle Book, The Day's Work, and The Seven Seas, and did work on Kim and The Just So Stories. The house is now owned by the Landmark Trust, and is available for rent.

“And there is nothing uprooted that is not changed.

Better to stay and wonder in the half light

How New England saunters where Kipling loved and ranged, so

And watch the starling flocks in first autumn flight.’’

— From “Thoughts of New England,’’ by Ivor Gurney (1890-1937), English composer and poet

But you never find it

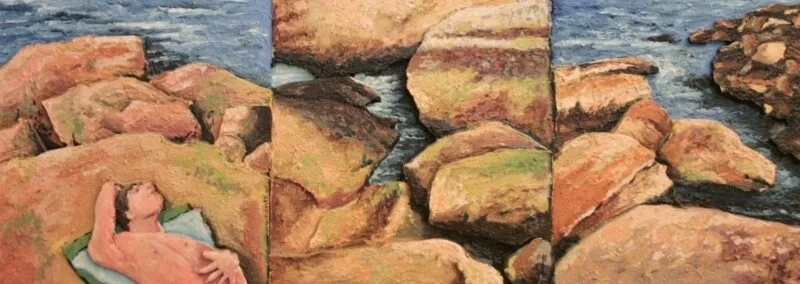

“In Search of Lost Time,’’ by Salvatore Del Deo, in the group show “The Mysterious’’, at Berta Walker Gallery, Provincetown, Mass., through Sept. 12.

The gallery says:

“{Provincetown-based} Salvatore Del Deo is a painter engaged in a spirited dialogue with his work, responding to the deep questions presented by the paintings themselves. It is this challenge that has held Del Deo's passion through the over 50 years of his painting career and has resulted in an immense and diverse body of work. His is a style that seems to traverse the continuum from the realistic to the abstract, with a natural fluidity available only to one who is thoroughly centered. Del Deo has painted all the familiar scenes of his life at land's end – fish, dunes, figures on the back beach, boats moored at the town wharf, trap sheds and lighthouses – made new for the viewer through the painter's rich palette and soulful perspective. It is as if he is focusing long-stored energy through the lens of pure color – the color concentrated, coagulated by that intense focus.’’

Mr. Del Deo also has a beloved Provincetown restaurant called Sal’s Place.

‘This piece of paradise’

From Barbara Gilson’s photography show at Dedee Shattuck Gallery, Westport, Mass., Sept. 11-Oct 10.

She explains:

“In the fall of 2020, I traveled from Portland, Ore., to arrive in South Dartmouth, Mass., to quarantine for two weeks before I was able to safely visit my family and spend time with my 92-year-old mom. I was so lucky to have this extended time in this landscape and very grateful to wander this piece of paradise.

“It was 70 degrees some of the days, snowed on Halloween, and when the winds stirred they rattled the windows and doors of the wooden structure I was lodged in.

“I began each day looking out onto the {Slocum} river and ended each day looking out onto the river. In between I wandered, hiked, always with my camera in hand.

“Alone, amidst the open sky, wide stretches of rivers and bays, I ventured into the maze of wetlands and trails, enchanted by the endless variations in light as it transformed the landscape.’’

The gallery manager was busy

“Already, by the first of September, I had seen two or three small maples turned scarlet across the pond, beneath where the white stems of three aspens diverged, at the point of a promontory, next the water. Ah, many a tale their color told! And gradually from week to week the character of each tree came out, and it admired itself reflected in the smooth mirror of the lake. Each morning the manager of this gallery substituted some new picture, distinguished by more brilliant or harmonious coloring, for the old upon the walls.’’

— From Walden, by Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862)

Clean-up operation

“Fine Dining” (oil on canvas), by Joan Baldwin, at the Kingston Gallery, Boston, through Sept. 26. She works out of a studio at River Street Artists, part of Waltham Mills Artists Association, in Waltham, Mass.

Chris Powell: Conn. doesn’t need bears; who’s paying the rent?

Black bear

MANCHESTER, Conn.

When Connecticut state legislators next put a survey in their "constituent service" mailings, it should include the question: How many bears will you accept in your neighborhood before Connecticut authorizes bear hunting?

Of course most people don't want any bears nearby. But then they don't like the idea of shooting them either, even as bear sightings have increased sharply in the state in recent years, along with home break-ins by bears, bear damage to crops and livestock, and highway crashes caused by bears.

The logic of Connecticut's laissez-bear policy is that eventually every town in the state will have at least a few dozen. Then no backyards, playgrounds, farms and streets will be safe. Even finding a discreet spot for smoking marijuana may become impossible, since while sale and possession of the drug are now legal, towns are already using zoning regulations to prohibit dispensaries and public smoking, marijuana being OK in principle but dope smokers being even less popular than bears. If the bears claim the woods, where will dope smokers go?

Zoning may prevent poor people from moving into leafy suburbs but bears won't comply. Sedating and relocating bears is no longer an option, their population already having exceeded what the state's wilderness areas can support. Waving bears away toward next door or the next town is no solution either, for another bear will follow soon enough.

It's not that Connecticut's bears (which are black bears) are so dangerous. They're not grizzlies. But they're not compatible with civilization either. Everything has to stop when a bear wanders by looking for food, and the animals do damage.

Trouble is always best handled by prevention. Like other hunting, bear hunting can be kept safe by regulation, and not much of it would be necessary in Connecticut if it was undertaken regularly in the northwest part of the state. Deer, while also cute, are often troublesome, too, and the state already authorizes and regulates deer hunting.

Even with bear hunting on top of deer hunting, Connecticut will have plenty of wildlife. Chipmunks, rabbits, woodchucks, foxes, opossums, raccoons, bobcats, squirrels, coyotes, weasels, beavers, birds and more will continue to delight and sometimes annoy everyone. But nature is not always harmless. The state can do without bears just as it can do without wolves and alligators.

xxx

With infinite money now at their disposal, how have the federal government and state government managed to botch the rental-housing problem so badly?

Government's closure orders during the virus epidemic crippled the economy and put millions of people out of work. Many couldn't pay their rent, so then government forbade evictions, disregarding constitutional requirements that property cannot be taken for public use without fair compensation.

Eventually rent-reimbursement funds were created but not before many landlords were ruined or nearly ruined financially, and even now much of the money has not been distributed, in part because, with evictions forbidden, renters have had little incentive to apply -- just as people have had little incentive to return to work while unemployment compensation exceeds their former wages.

A few weeks ago the federal Centers for Disease Control claimed the authority to forbid evictions. President Biden said this was probably unconstitutional but went along with it. The Supreme Court rejected it the other week.

Maybe the government should have simply instructed landlords to send their defaulted rental bills to a government agency for payment. Of course such a system would have invited substantial fraud, but at least it would have been constitutional.

This mess makes even more ridiculous the sanctimonious prattle about housing that filled the General Assembly a few months ago -- the prattle that housing is "a human right."

Rights are things people possess without having to pay for them, such asb freedom of speech and religion. There is no housing unless somebody pays for it. But housing can be arranged if the money is appropriated.

Of course, the state legislators proclaiming that housing is a human right declined to appropriate any money so that housing would be free like other rights. The legislators meant only to strike a pious pose. Could they just try to get the overdue rents paid?

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer in Manchester.

And where is it?

“Even if the place has a McDonald's,

the help may only work there,

live outside of town,

be so young they don't care about

museums, churches, health-food stores, dances,

or whether the town is on a map….’’

— From “Lost Is the Farthest Place,’’ by Richard Gillman (1929-2004), American poet and university administrator. He lived the later part of his life in Waterville, Maine, home of Colby College (and its large art museum).

Miller Library at Colby College

Caitlin Faulds: How do users interpret warnings about coastal water quality?

Misquamicut Beach, in southern Rhode Island

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

A new study on perceptions of coastal water quality shows users may have more difficulty interpreting warning signs than previously thought.

The University of Rhode Island study, recently published in the Marine Pollution Bulletin, surveyed more than 600 recreational users around Narragansett Bay regarding their understanding of water quality to find that water quality had “multiple meanings.” A complicated conceptualization of water quality could have big implications for water policy and management.

“Water quality is pretty complex for people,” said Tracey Dalton, a URI marine affairs professor and Rhode Island Sea Grant director, who co-authored the study. “It’s not as simple as the chemical components that we tend to manage for.”

Water quality managers typically look at a variety of biochemical and physical indicators, including nutrients, temperature, acidity, oxygen levels, phytoplankton, fecal coliform and enterococci, to see if a site meets surface water quality guidelines set by the Environmental Protection Agency and outlined in the Clean Water Act.

But, according to the recent study led by URI marine affairs doctoral candidate Ken Hamel, these indicators can be difficult to understand for beachgoers, who more commonly tote sunscreen and beach towels than sterile sample bottles, plankton nets or conductivity, temperature and depth (CTD) sensors.

With help from his research team, Hamel conducted hundreds of in-person surveys at 19 sites along the Rhode Island shoreline. They asked recreational users to grade water quality in the area on a scale from 1 to 10, and then explain the reasons for their score.

Users generally perceived water quality in upper Narragansett Bay to be worse than in the lower bay. This assessment aligned fairly well with biochemical reports in the area, Hamel said, generally cleaner on the southern, open end of the bay than in the more urban, post-industrial north.

“You’ve got to wonder … how do people make that judgment,” he said. “Because they don’t necessarily know how much sewage effluence is in the water. They can’t see E. coli or enterococcus. They can’t smell it. Nutrients are also invisible.”

After a statistical analysis of the responses, the survey showed nearly 23 percent of users based water quality determinations on the presence of macroalgae or seaweed.

“Seaweed, which is a perfectly ecologically healthy organism for the most part — people perceive that as a water quality problem,” Hamel said. “From a Clean Water Act perspective, [seaweed in] the north is a water quality problem, the south is not.”

In the northern reaches of Narragansett Bay, macroalgal concentrations are often the result of nutrient overload, especially nitrogen and phosphorous borne of fertilizers and road runoff. It can indicate a problem with marine water quality.

But further south, macroalgae are less associated with pollution and are not necessarily an indicator of nutrient enrichment or water degradation, according to Hamel. Seaweed grows in reefs off the coast, breaks up due to wave action and can be blown on shore, especially on south-facing sands.

With no simple association between water degradation and seaweed, Hamel was surprised to see so many people use it as a basis for water quality determinations.

“There is very little research on perceptions of algae or seaweed period,” Hamel said. “It’s just a very understudied subject.”

Shoreline trash, “broadly defined” pollution, strong odor, water clarity, swimming prohibitions and nearby sewage treatment plants were also cited by beachgoers as indicators of poor water quality.

“People figured if there was a sewage plant nearby the water must be dirty,” Hamel said. “Although if you think about it, it’s slightly backward right. That should make the water a little bit cleaner.”

Another 9 percent of respondents also indicated that firmly held place beliefs played a role in water quality grades. These place beliefs, Hamel said, were “hard to pin down,” but were based primarily on the reputation of a place, whether linked to former industry or long-embedded regional knowledge of Narragansett Bay.

“One person even said, ‘This place is too upper bay.’ Like it was just common sense for them that water in the upper bay must be bad,” Hamel said.

Narragansett Bay visitors with water-quality questions can find detailed reports for sites through the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management and through the Narragansett Bay Commission. But, according to Hamel, the survey shows a need and opportunity to better engage beachgoers in water quality education, so the average recreation user can more accurately read the warnings presented in an environment.

“As a group of social scientists, we’re really interested in understanding how people are connected to their environment,” Dalton said. “From a policy perspective, it's really important to understand what the general public thinks since they’re the ones who are going to coastal sites, they’re the ones affected by policies.”

The Clean Water Act, Hamel said, has gaps in the way it was written and interpreted by water managers. As set out in 1972, the federal law mandated that states reduce and eliminate pollutants primarily to protect wildlife and recreation. Nicknamed the “fishable/swimmable goal,” the law gives priority to recreational users.

The law is enforced at the state level, with slight variations in procedure, though it typically takes the form of measuring and monitoring biochemical and physical variables. But, according to Hamel, that strategy can leave out certain stakeholders and minimize non-user concerns.

“There’s a lot of other people that use the water that aren’t necessarily in it or on it,” he said. “And their … perspectives aren’t really considered by the way the Clean Water Act is implemented.”

There isn’t necessarily anything wrong with the law, Hamel said, and it has been instrumental in improving water quality. But policymakers and managers could better address all stakeholders and “more explicitly consider” the needs of non-users, he said, including those who may work or live nearby.

“In terms of how we direct our investments and direct our funds, we want to make sure that we’re also addressing what people care about,” Dalton said. “It’s really important to ground that in what the understanding is of the concept of water quality.”

Caitlin Faulds is an ecoRI News journalist.

Light-headed

“Ugly duck” (limited edition archival pigment print on fine art paper), by Flora Borsi, in her show “Identity: The Self-Portrait Series,’’ at Lanoue Gallery, Boston, through Sept. 20.

What can be endured?

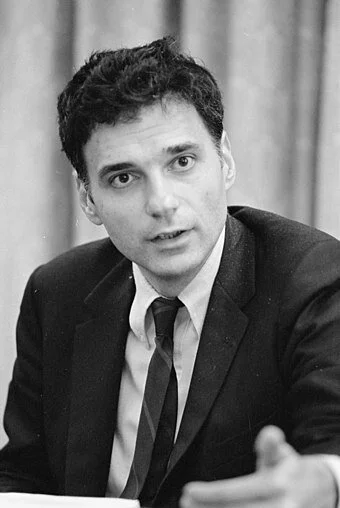

Sperm whale striking The Essex on Nov. 20, 1820 (sketched by Thomas Nickerson)

“There is no knowing what a stretch of pain and misery the human mind is capable of contemplating when it is wrought upon by the anxieties of preservation; nor what pangs and weaknesses the body is able to endure, until they are visited upon it; and when at last deliverance comes, when the dream of hope is realized, unspeakable gratitude takes possession of the soul, and tears of joy choke the utterance.’’

-- Owen Chase, sailor, in Narrative of the Most Extraordinary and Distressing Shipwreck of the Whale-Ship Essex, of Nantucket

Here’s an edited version of a good Wikipedia summary of the background of this horror story:

“The Essex was a whaler from Nantucket launched in 1799. In 1820, while in the Pacific Ocean under the command of Capt. George Pollard Jr., she was attacked and sunk by a sperm whale. Thousands of miles from the coast of South America with little food and water, the 20-man crew was forced to try to make for land in the ship's surviving whaleboats.

“The men suffered severe dehydration, starvation, and exposure on the open ocean, and the survivors eventually resorted to eating the bodies of the crewmen who had died. When that proved insufficient, members of the crew drew lots to determine whom they would sacrifice so that the others could live. A total of seven crew members were cannibalized before the last of the eight survivors were rescued, more than three months after the sinking of The Essex. First mate Owen Chase and cabin boy Thomas Nickerson later wrote accounts of the ordeal. The tragedy attracted international attention, and inspired Herman Melville to write his 1851 novel Moby-Dick.’’

Those old small-town reports

The Cohasset Common still looks much as it did in the ‘50s except the elms are gone because of Dutch Elm Disease.

Still the venue of generally polite town meetings

— Photo by ToddC4176

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The other day I looked at municipal reports of my hometown, Cohasset, Mass., in the late ‘50s, when I lived there. There have been big changes since then, among them that Republicans outnumbered Democrats by more than 5 to 1, reflecting the old allegiances of small-town New England Yankees back then: The town’s Democratic now. And they called the town dump the “town dump’’ instead of the euphemism of Cohasset’s current “Recycling Transfer Station’’.

The old reports’ language was a bit more formal than now, indeed sort of Victorian, to wit, in the late ‘50s: “That the Selectmen are instructed to advise His Excellency the Governor and our Senators and Representatives….” And nicknames are frequently used now in the reports, a practice unheard of back then.

There were also such reminders of the passage of time as Memorial Day being called Decoration Day (in my house we still called Veterans Day Armistice Day back then) and a plan to spray a wetland with DDT, the environmental menace that wouldn’t be banned until 1972. But perhaps the most noticeable change was that most of the names of town officers in the reports in the late ‘50s were WASP, and now there are lots of Irish and Italian names, and some names whose ethnicity is hard to figure. Those once-city dwellers left the city to move to the suburbs, including now-rich ones such as Cohasset.

But I was charmed to read that the town still has that old colonial occupation of “fence viewers,’’ charged with dealing with property disputes.

You can learn a bit of local culture and sociology by reading old small-town reports.

But don't think about the Mu variant

“By the River” (acrylic), by Massachusetts painter Ricardo Maldonado, in the group show “Reflection/Reawakening/Resilience,’’ at the Lexington (Mass.) Arts and Crafts Society, Sept. 10 to Oct 3.

The morality of nature

Louise Dickinson Rich’s former house in rather remote Upton, in western Maine.

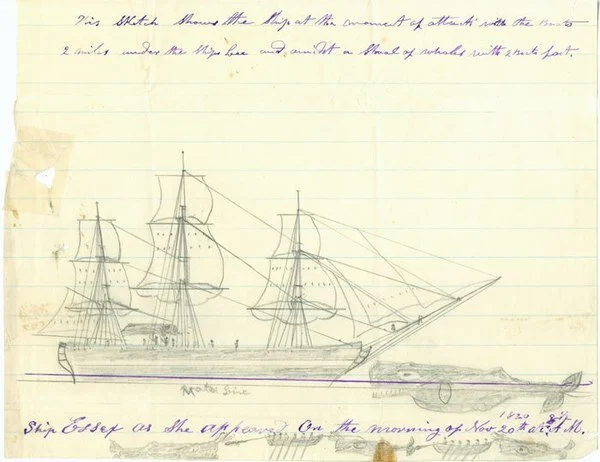

Lake Umbagog

“Nature is strictly moral. There is no attempt to cheat the Earth my means of steel vault of bronze coffin. I hope that when I die I too may be permitted to pay at once my oldest outstanding debt, to restore promptly the minerals and salts that have been lent to me for the little while that I have use for blood and bone and flesh.”

―Louise Dickinson Rich (1903-1991), a once well known writer of fiction and nonfiction works, most set in Maine and Massachusetts.

Her best-known work was her first book, the autobiographical We Took to the Woods (1942), set in the 1930s when she and husband, Ralph, and a friend lived in a remote cabin near Lake Umbagog, Maine. She was born in Huntington, Mass., and died in Mattapoisett, Mass.

At the Mattapoisett town dock, off Buzzards Bay

Timeless sky

“I passed by the fence

and looked up,

and whatever happens

happened to make that sky

seem timeless,

awash with well-being….’’

— From “A Green Evening, September, 1952,’’ by Brendan Galvin (born in 1938), American poet. He was born in Everett, Mass., and now lives in Truro, Mass., on Cape Cod.

The grand Parlin Memorial Library, in Everett

— Photo by Elizabeth B. Thomsen

Space/time

“Wormhole” (ink on masonite), by Hampton, N.H.-based Bill Oakes, in the group show “Renewal,’’ with Barbara D’Antonio and Gene Galipea, at Haley Art Gallery, Kittery, Maine, Sept. 9-Nov. 19.

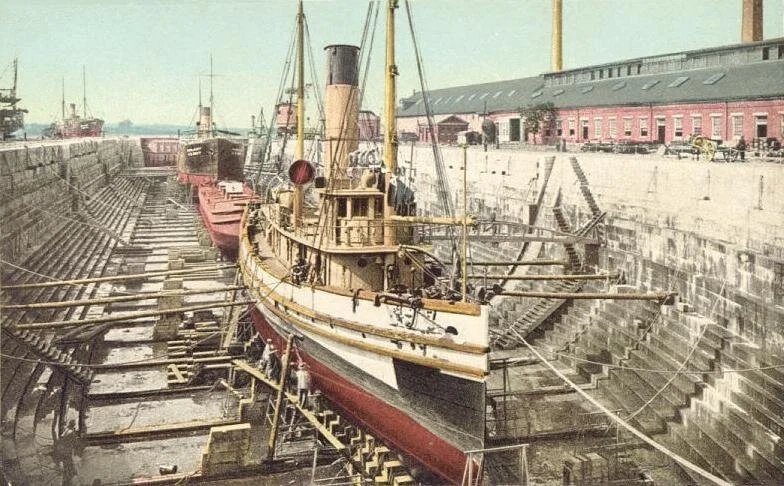

Shipyard dry dock in Kittery, circa 1908

Llewellyn King: As climate warms, utilities must become much more resilient

The severe flooding in Greater New York, New Jersey and New England from the remnants of Hurricane Ida, that storm’s devastation in New Orleans and much of the rest of Louisiana and the winter freeze in Texas usher in a new reality for the electric industry, showing how outdated their infrastructure has become and how they have to much more expect the unexpected.

Resilience is the word used by the utilities to describe their ability to speedily restore power, to bounce back after an outage. This year, resilience has been put to the test with major challenges affecting electric utilities from coast to coast. Mostly, the results have been disappointing to catastrophic.

It is reasonable to believe that resilience means that if there is an outage power will be back on forthwith or within hours, and that is often the case.

But as the attacks on the system from aberrant weather have become more frequent and severe, the bounce back has been closer to struggle back slowly.

Two cases tell a tale of catastrophe. Recently, the complete loss of electricity to New Orleans during Hurricane Ida, much of which is still in the dark and with people suffering without water in their homes, along with the absence of light, air conditioning, or the ability to charge a cell phone.

Even before Ida tore into the Gulf Coast, teams from other utilities were on their way to help. ConEd in New York was one of many utilities that had trucks rolling to the scene before Ida hit. That kind of quick, fraternal response is often what is meant by resilience. Bold and well-coordinated though it may have been, it was not nearly enough. Entergy, which supplies the power to the area, failed the resilience test.

The other standout was in the failure of the Texas grid when Winter Storm Uri struck in the middle of February. It froze much of Texas for five days and more than 150 people died, some by freezing to death in their homes. The unfortunately named Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT), which operates the electric grid of Texas, abominably failed the resilience test.

Some of the natural-gas supply was cut off during the deep freeze because the system hadn’t been weatherized, but the gas that did flow also flowed money.

The gas operators made enormous profits, including Energy Transfer, which made $2.4 billion. Not only had the gas operators not signed on to the concept of resilience, but the idea of commonweal was absent.

While electric utilities -- there are a few large electric utilities and more than 80 small ones in Texas -- struggled to honor their mandate to serve, the gas suppliers, according to those in the electric utility industry, served their mandate only to their shareholders.

Rayburn, the electric cooperative that has a service area near Dallas, spent what it had budgeted for three years in just five days on gas purchases, CEO David Naylor told me.

On my PBS show, White House Chronicle, Paula Gold-Williams, president and CEO of CPS Energy, the large, municipally owned gas and electric utility in San Antonio, said she thought that the suppliers of gas to electric generators should be regulated as Texas utilities are.

Wildfires in the West, storms in the East and up the center of the country have put a huge strain on the electric utilities. What is clear is that “resilience” needs to be defined in a much broader sense. That whole infrastructure of the electric-utility industry needs to be re-examined with a view to surviving monstrous weather. The cost in lives and in treasure is very high when electricity, the essential commodity of modern life, fails.

This new imperative comes at a bad time for the electric-utility industry, which is struggling with daily cyber-attacks, converting from fossil fuels to alternatives, and straining to find new, durable storage systems.

One of the trends to greater security is to encourage microgrids – small, self-contained grids that can store and generate electricity, often from renewables like solar. These can disengage from the grid in times of stress and continue providing power to the microgrid.

Other suggestions include undergrounding electric lines. California’s Pacific Gas and Electric has proposed undergrounding 10,000 miles of lines to counter wildfires sparked by downed cables. The cost might be insupportably high -- over $1 million a mile in level ground, according to one estimate.

Entergy, according to The Energy Daily, has 2,000 miles of lines down in New Orleans. Burying just the most vulnerable lines in the nation would be a massive civil engineering undertaking at a daunting cost. Other ideas, please?

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Long Island Expressway in New York City shut down due to flooding as the remnants of Hurricane Ida swept through the Northeast on Sept. 1-2

— Photo by Tommy Gao

Fried in Rockport

“Sunbather Rocks at Halibut Point’’ (Rockport, Mass.) (mixed media on wood), by Marja Lianko, in the Collection of the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester.

George McCully: Rauch book tries to ‘socialize knowledge’

“Knowledge’’ (1896), by Robert Reid, at the Thomas Jefferson Building, Washington, D.C.

BOSTON

From The New England Journal of Higher Education (NEJHE), a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Book Review

The Constitution of Knowledge: A Defense of Truth; Jonathan Rauch; Brookings Institution Press; Washington D.C.; 2021.

Reviewed by George McCully

This is a prominent and timely book by a distinguished journalist on a subject of profound national significance, especially for our educational and scholarly professions as NEJHE has previously noted. Yet, despite its many admirable features and high praise from leading commentators, I found the book’s argument and potential value fundamentally undermined by a surprising misconception of its central subject.

The book contends that, as with our national political Constitution, we have a “Constitution of Knowledge,” which works to channel our civic discourse in constructive directions by defining the bounds of proper intellectual customs. By acting as a filter for debates among contending parties, it sorts out true, good and beautiful ideas from their opposites, over time pointing us in progressive directions. This Constitution developed concurrently with our federal Constitution, over centuries leading to the Enlightenment, with the rise of “liberal science” and progressive ideals. Recent psychological experiments have shown, however, that humans can be and often are driven by irrational impulses to act selfishly and against the common good. The current revolution in information and communication technology has been used maliciously to favor and manipulate those impulses, as shown by our recent politics, especially under Trump. Therefore, we need now to revive and strengthen this Constitution of Knowledge in our politics and civil affairs. All this is certainly a plausible argument.

Plausible, but not persuasive. The epitome of its problems is its misleading title, promising far more than the book delivers. This is not a book about “knowledge” per se, but about public knowledge. It does not offer a defense of “truth” per se, but rather an extensively researched and fervent attack against current political malpractices of mis- and dis-information, with numerous suggestions of ways to oppose and avoid them. The result is that the whole argument is weaker than expected.

The book’s essential flaw is its socialization of “knowledge.” It does not consider an assertion to be valid or true unless it has persuaded people and been accepted socially. Rauch writes (emphases mine): “The only way to validate a [specific proposition] is to submit it to the reality-based community.” He adds: “[L]iberal science’s distinctive qualities derive from two core rules: … the fallibilist rule: No one gets the final say” and “the empirical rule: No one has personal authority … Crucially, then, the empirical rule is a social principle. …”

In other words, if you and I, in our research, make some new and original discoveries based on adequate evidence, those discoveries according to Rauch’s book are not “knowledge” until other people agree with them. I found his exclusively social emphasis about “knowledge” more than a bit weird. It reminded me of the old saw about the questionable sound of an unobserved tree falling in the middle of a forest, or perhaps more pointedly of the politically incorrect joke, “If I say something and my wife doesn’t hear it, is it still wrong?” By focusing on this socialization, the book fails to promote the simple but powerful antidote we need: namely, thinking on the basis of evidence—the routine practice of all modern scholarship, science and jurisprudence, accessible by all educators and citizens.

In fact, this socialized approach to knowledge is exactly what has rendered knowledge more, not less, vulnerable to the malicious and corrupt mis- and dis-information newly empowered by the IT revolution. It is what has caused, for example, a currently reported 88,000 people per week to fight Covid with the livestock de-wormer Ivermectin which they can buy from agricultural feed stores. In contrast, the authentic empirical practice of grounding knowledge in evidence is invulnerable by communications techniques. If what good citizens promote and defend is itself demonstrably unshakeable, the cause of truth in democracy can be more effectively strengthened and defended. This book shows no awareness of this.

Moreover, conceiving knowledge in exclusively sociopolitical terms has encouraged the odd analogy Rauch has drawn to a “Constitution of Knowledge” comparable to our federal Constitution in that it governs (public) knowledge. But this comparison is obviously flawed—the alleged “Constitution of Knowledge” has no Article VI, Section 2, explicitly making it the “supreme law of the land” nor Article III, Section 1, vesting “judicial power in one supreme court” of a few officials, backed by a huge and elaborate law enforcement apparatus. Participation in Rauch’s “Constitution of Knowledge” is purely voluntary. While it is customary though not infallible among professionals, it does not guide popular thinking or discussion outside the professions and is highly vulnerable by today’s hyper-powerful communications technology in vicious hands.

In short, this important book is basically at odds with itself. While it is true that the public in general does not “think on the basis of evidence” and relies for verification on trusting other people, this is what has caused the much-discussed epistemic crisis of our democracy. Our resulting sociopolitical polarization and mutually antagonistic tribal cultures are what prevent our electorates and representatives from objectively deciding on the relative merits of various candidates and ideas. The symbiosis of journalism with civil opinions, which Rauch’s book exemplifies, is at the heart of our crisis. We need journalism and public discourse to be based on and promoting reliance on evidence, not public opinions.

I am reluctant to say this, but to this journal’s readership it bears notice: The strangeness to us of this book’s argument derives from its journalistic, rather than scholarly or scientific, habit. The sea in which journalism swims is entirely sociopolitical; that is why “fairness” and “balance” in reporting various perspectives have long been promoted as criteria of public value by schools of professional journalism. For journalists, it is understandable that “knowledge” is likely to mean “public knowledge” based on social acceptance. In contrast, the graduate schools that have trained us in professional research promote “truth” which we take to be synonymous with “knowledge” as our sole professional objective and criterion of value. For scholars (and scientists) “knowledge” is gained only by adherence to adequate evidence. Many of us in the course of our professional careers have made new and original factual discoveries, which we consider new “knowledge” even before their publication and indeed as an elementary criterion for publication in the first place.

This is a gap that needs now to be bridged, not smudged nor insisted upon. This means that we—the community of scholars and educators (including journalists)—have a substantial civic role and responsibility to collaborate in protecting democracy from its current detractors, by energetically teaching and promoting thinking on the basis of evidence in all public discourse, especially including popular journalism. When any assertion is made in civic arenas, the first question by journalists—always and predictably so that everyone becomes accustomed to it—should be, “What’s your evidence?”

George McCully is a historian, former professor and faculty dean at higher-education institutions in the Northeast, professional philanthropist and founder and CEO of the Catalogue for Philanthropy.

Import minorities?

]=

Schoolhouse built in 1832 in Sharon, N.H.

“I live in rural New Hampshire, and we are, frankly, short on people who are Black, gay, Jewish and Hispanic. In fact, we’re short on people. My town {Sharon} has a population of 301.’’

— P.J. O’Rourke (born 1947), American journalist and satirist