Beyond makeup

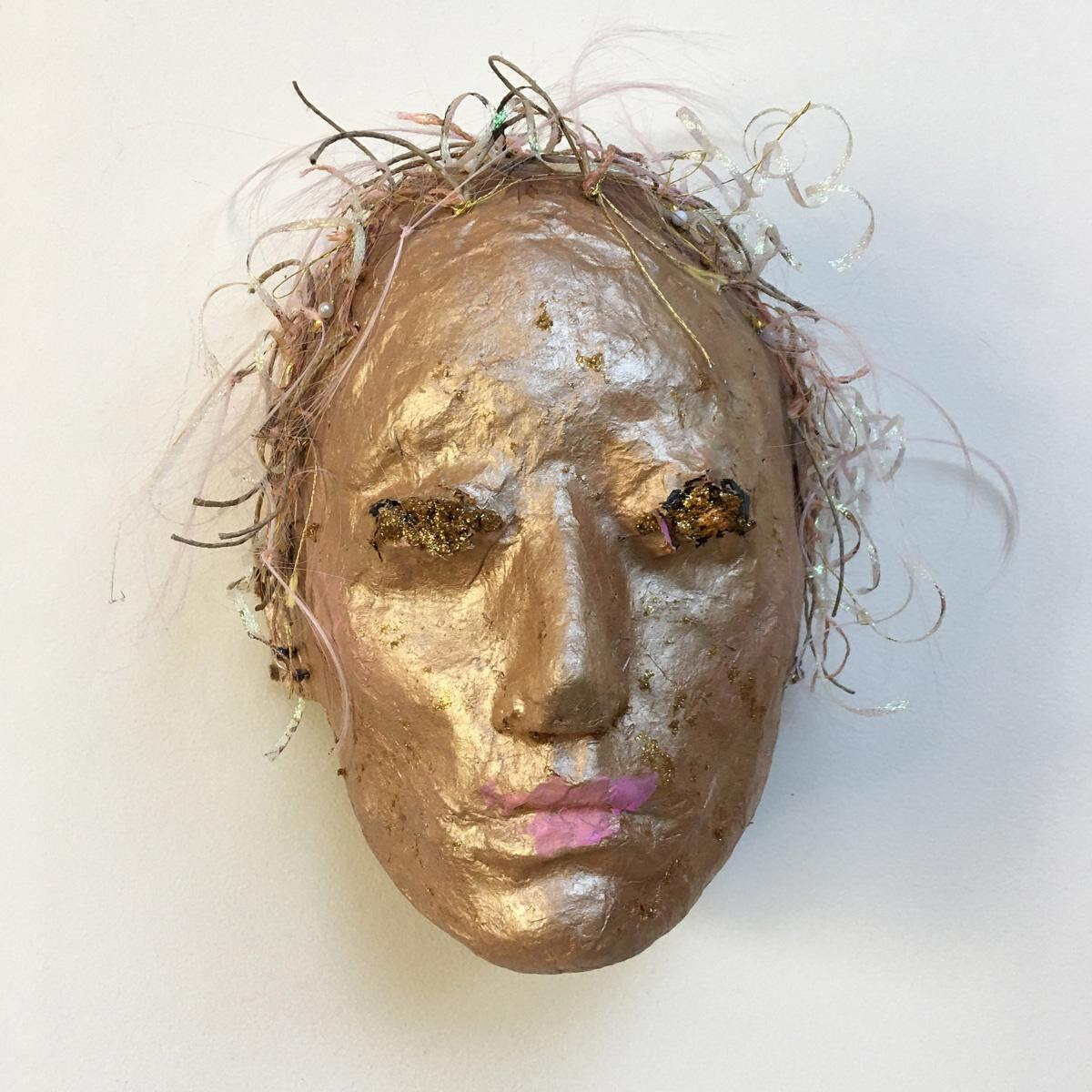

“Shedding” (mixed media), by Christine Palamidessi, in her show “The Future Has an Ancient Face,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, for month of October.

The gallery explains:

“In 2020, Christine Palamidessi called on the Goddess Nike, the embodiment of Victory, to make a comeback. ‘Who are the warriors, the champions, and what challenges are they fighting?’ the goddess asked. ‘Pandemic. Politics. Conspiracies,’ the artist answered. Nike handed Palamidessi her face, ‘Use it,’ she said.

“The artist used Nike’s face as a container to make masks that embody a swirl of words and emotions: Wuhan, Shedding, Lockdowns, Culture Cancelling, Recounts. She painted, stitched, bejeweled and wrote on the masks; some are frightening and others make us smile. Each reminds us we survived something hard: we entered a world that was interrupted and have the opportunity to create a different, more humane way of life -- a life without masks.’’

Don Pesci: The body count in New Haven

New Haven from the south, with The Hill in the foreground. East Rock is visible in the background

— Photo by Emilie Foyer

VERNON, Conn.

Paul Bass of the New Haven Independent is keeping a body count.

From January to March alone, the publication notes, “Alfreda Youmans, 50, and Jeffrey Dotson, 42, were found dead by the police inside a Winthrop Avenue apartment, Jorge Osorio-Caballero, 32, was shot and killed in Fair Haven, Marquis Winfrey, 31, was shot and killed in Newhallville, and Joseph Vincent Mattei, 28, was shot and killed in the Hill. Someone shot Kevin Jiang, 26, to death in Goatville on Feb. 6. Angel Rodriguez, 21, was shot to death in Fair Haven in mid-February, his body dumped by the Mill River in East Rock. Dwaneia Alexandria Turner, 28, was shot to death in the Hill on March 16 during an argument with two other women.”

And the year’s total body count so far for the city that has given us Yale, two nationwide recognized pizza houses, the inimitable Roger Sherman, and William Celentano, a funeral director and the first Italian-American mayor of New Haven -- indeed, the last Republican mayor elected in New Haven 68 years ago – is 21.

“There have been 21 homicides in New Haven this year,” NBC Connecticut reports. “Twenty murders were reported citywide in 2020, according to statistics from the New Haven Police Department” – and we have about 3 months left to close out the year.”

It promises to be a record year, not only for new Haven but for all major cities in Connecticut.

The New Haven Independent, whose reporting on murders in New Haven has been more granular than some might wish, tells us the latest shooting victim is Trequon Lawrence, 27 years old, employed by Yale New Haven Hospital, and a new home owner.

“I purchased my first multi-family dwelling,” Lawrence wrote on Facebook. “Truly blessed and highly favored. Yet this is a bitter sweet time in my life. As some of you may know I lost my baby girl a few weeks back. And in all honesty she was my motivation for buying the house. When she left a piece of me left with her. Nonetheless I still had to make this move toward putting my family in a better position. In life we will experience many highs and many lows. But without the lows we can’t truly appreciate the highs. I am GRATEFUL overall and will continue to strive for greatness in light of my daughter.”

Lawrence was shot eight times. The shooting occurred, the publication noted, “down the street from the home of state Sen. Gary Winfield,” who “observed afterwards that the police department has not been giving the public much information about what’s behind this year’s flood of shootings.”

Contacted for comment by the publication, Winfield said, “My experience over a couple of decades is that you don’t get the intimate details of the shooting itself. But you get, ‘This is what we’re seeing. We’re seeing these are isolated incidents.’ Or: ‘They’re related to gangs or cliques’ …. You get some kind of trending information to give some sense of what is actually happening,’ Winfield said.”

Sure, sure. The causes of shootings in New Haven this year are not materially different than the previous year, and the year before that, and the two decades before that.

Even so, the accumulative data apparently is not sufficient to allow the General Assembly to remediate city shootings through legislation.

“While the police need to keep certain details about individual shootings confidential while they investigate,” the publication noted, “in the past they have communicated more about what’s behind outbreaks of violence, Winfield said. He argued that officials and the community can’t craft an effective response without more information.”

The notice posted on Dante’s Gates of Hell was, “Abandon hope, all ye who enter here.” Things are not quite that bad in New Haven. The state delegation, Winfield said, has “reached out to the mayor to have a conversation about what has been going on. In order to tackle the problem we need to know what is actually happening. People in the city have fear. Some of that is born from what is going on. Some of that is born from a lack of information.”

New Haven has had a surfeit of insouciant Democrat politicians over the last 60 years, but Winfield’s indifference to a murder in his city that occurred “down the street from his home” is a high bar to surmount.

Whatever can Winfield mean when he says he lacks the proper data from New Haven police to fashion an answering piece of legislation – other than that legislation for which Winfield is best known: a bill that withdraws from all police officers in the state a partial immunity from suits that would allow plaintiffs to seize the personal assets of police officers in Connecticut? The removal of protective immunity in Winfield's signature bill, some have argued, likely contributed to a drop-off in urban police recruitment, and a flight from urban areas to the suburbs by city police officers, this at a time when New Haven’s murder rate is growing by leaps and bounds.

Following an affirmative vote on the Winfield bill, police chiefs warned, “There is not and cannot be an alternative to this for any police officer or agency. We strongly believe that the loss of qualified immunity will destroy our ability to recruit, hire, and retain qualified police officers both now and in the foreseeable future. We are also very concerned about losing our current personnel at a higher rate than we normally can replace. Any impact on our ability to recruit qualified personnel in general will also impact our minority recruitment efforts, which is a goal in this bill that we strongly support.”

Any of the survivors of the relatives of victims listed by the New Haven Independent in its granular coverage of New Haven murders doubtless would appreciate a clear answer to the above question?

Surely it is the greater part of Winfield’s obligation as a state senator to fix his attention on murders that occur right under his nose and to propose legislative fixes that really do fix the problem.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

Got milk?

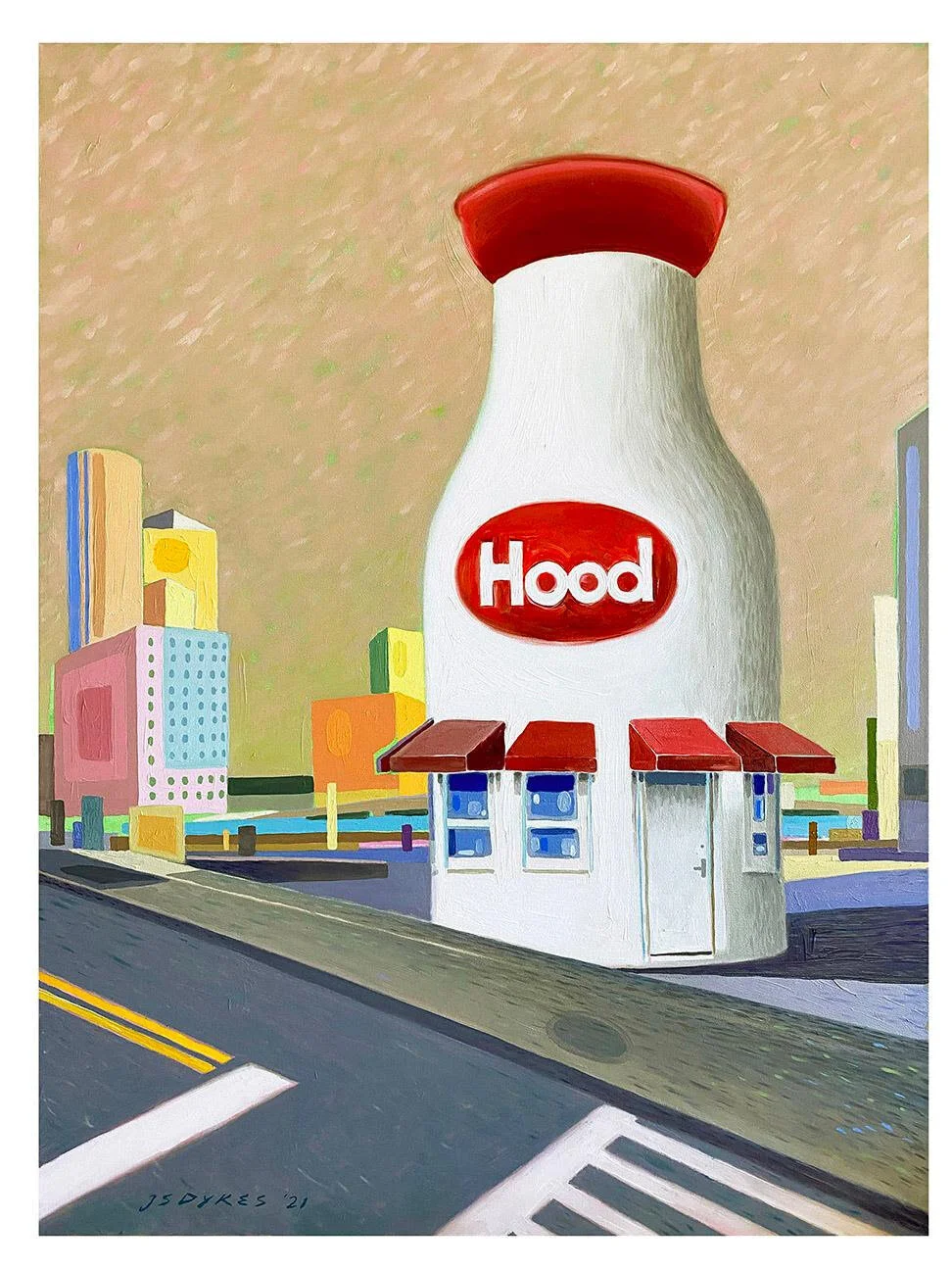

“Milk Bottle,’’ by John S. Sykes, in his show at The Gallery at 249 A Street, Boston, through Sept. 14. The show is inspired by mid-20th Century advertising. H.P. Hood for years has been the dominant New England dairy company. It was founded in 1846 in Lynnfield, Mass., and is now based in the Charlestown section of Boston.

David Warsh: Of sportswriters, race and great news publications

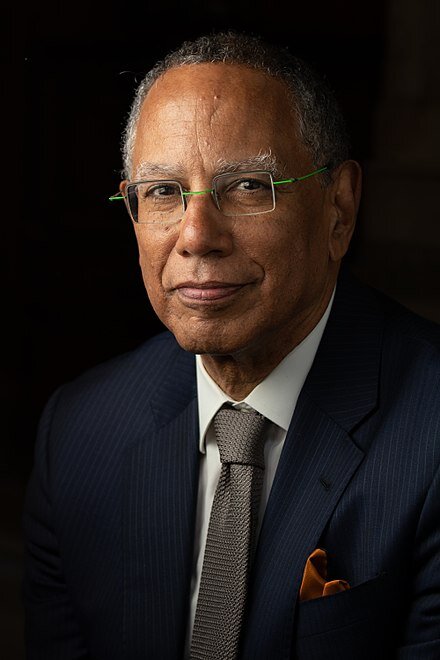

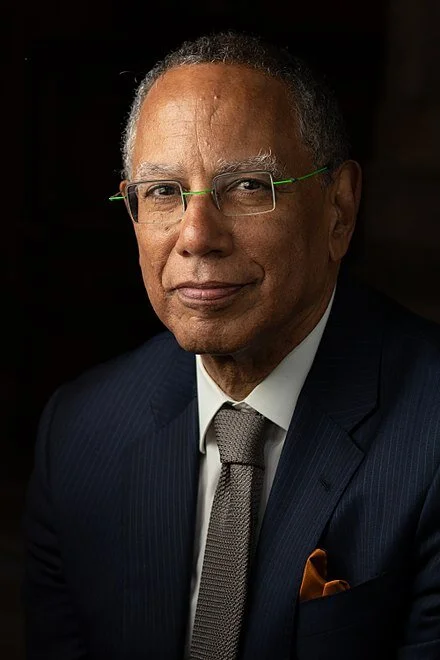

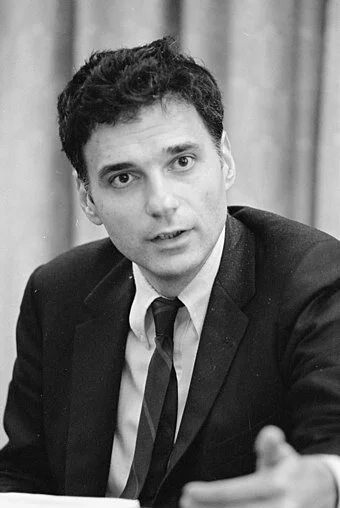

New York Times executive editor Dean Baquet

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Because it was August, I was reading Tall Men, Short Shorts, the 1969 NBA Finals: Wilt. Russ. Lakers. Celts, and a Very Young Sports Reporter (Doubleday, 2021). Leigh Montville was one of the many excellent sports columnists at The Boston Globe in the twenty years that I was there, somebody whom I always read no matter who or what he was writing about. After he was unreasonably refused an exit as columnist from the ghetto of sports, he left the paper for Sports Illustrated, where he wrote extended features and the back-of-the-magazine column for many years. He wrote eight books along the way. Tall Men, Short Pants is his ninth, a summing-up of much he learned about life in a fifty-year career as a journalist.

I’d been alerted to the book by The Globe’s former long-time managing editor, Thomas F. Mulvoy, who wrote about it in the Dorchester Reporter. At one point, Mulvoy says:

In a section that comes off the page with a sharp edge of sadness, Montville redresses himself (for the umpteenth time, his words suggest) for his silence at the press table when the Celtics played the Knicks in New York earlier in the season. A Globe colleague sitting next to him gave vent to his bigotry by loudly and repeatedly using the N-word while talking about the game being played in front of them. [Montville] writes: “I have thought for all these years of the things I should have done. I should have told [him] to shut up. Right away, I should have done that. If he didn’t shut up, I should have grabbed him, done something. … I should have reported all this to someone at the Globe on our return. I should have decided never to talk to him again. I should have done any of this stuff. I did nothing”

The 26-year-old Montville, who is White, served as no more than witness that day – the book reveals how he learned that his Globe colleague was deliberately baiting another Globe sportswriter, a well-known liberal, nearby – only much later affording a glimpse of the fractious mood of the nation in 1969. Montville attended his colleague’s wake thirty years later. Otherwise, he imaginatively covered changing attitudes about race in America, in columns and books, including Manute: The Center of Two Worlds (2011), and Sting like a Bee. Muhammad Ali vs. the United States of America, 1966-1971 (2017). Sports has done more than its share, and better than Hollywood, to illuminate rapidly changing stereotypes of race and class in the last fifty years. Montville was alert to the story every step of the way.

Reading Tall Men, Short Pants brought into focus a project of The New York Times of which I gradually became aware over the last couple of years.

I do not mean the paper’s scrutiny of the killings of Black men and the occasional Black woman by Whites, mostly police officers, before George Floyd was murdered by Officer Derek Chauvin, in Minneapolis on May 25, 2020, though even now, thanks to the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2013, it seems important to remember their names.

(Those whose stories made the front pages include Trayvon Martin, in Sanford, Fla; Eric Garner, in Staten Island, New York; Michael Brown, in Ferguson, Mo.; Walter Scott, in North Charleston, S.C.; Philando Castile, in St. Paul; Stephen Clark, in Sacramento, and Breonna Taylor, in Louisville.

Nor do I mean the special issue of the magazine called The 1619 Project, the Times’s coverage of the debate over Critical Race Theory, or the series of essays by critic-at-large Wesley Morris that earlier this year was recognized with a Pulitzer Prize. I have in mind something less concrete but ultimately even more eye-opening, at least to me.

I am thinking of a surge of ordinary news stories about contributions to American culture by African-American citizens. These stories appeared in unusual numbers, day after day, over the course of the last eighteen months. In the trade, this kind of display is called ROP, or run of the paper, with stories placed anywhere in the paper at the option of an editor – world, U.S., politics, NY, business, opinion, tech, science, health, sports, arts, books, style, food, travel, real estate, obituaries. The surge was as unmistakable as it is difficult to describe. Instead of data, I have only personal experience of it, to which I aim to testify here, briefly.

I scan the print editions of The Times, The Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times each morning at home, glance online at Bloomberg and study the story list of The Washington Post when I reach the office. In the evening, I read and clip (or print) whatever is most important to me. The differing trajectories of these five great English-language news organizations in the thirty years since the Internet emerged as a public communications medium has been fascinating, but that is a subject for another day. For now it is enough to say that The Times remains the most ambitious among them, more sparkling than ever in its aspirations.

It was the morning scanning of The Times that first produced the effect. So relentless had its coverage of Blacks newsmakers and their concerns become over the last year that one day it dawned on me what The Times had achieved. Some of the stories made big impressions. Others seemed peripheral, at least to my interests. I discussed the experience with my friend, Vincent McGee, who described it thus: “I first noticed it with obituaries, some current – mainly arts, music and sports – and others ‘catch ups’, often of Black women lost in history.”

By distorting its usual budget of stories – not much, mind you, this was only a surge – the newspaper’s editors had given me, a White reader, the feeling of somehow being unimportant. For some fleeting part of the day, I felt as many Black readers must feel most days, oppressed by the relentless attention The Times paid to the Other. This was showing, not telling, how it felt to be left out. It showed, too, what it meant to be included in. As an exercise in good newspaper editing, I will never forget it.

How had the decision to reorient the coverage been made? Anyone who knows anything about newspapers understands that inspiration comes from the bottom up. Orders are given, of course; stories are assigned, or turned back for more work. There are countless meetings, discussions, bull sessions, retreats. Word gets around. Better to say that a curiosity about race, gender, ethnicity and discrimination had been authorized at The Times as long ago as the Nineties, then encouraged, becoming wide-ranging, before coming to a low boil in 2020.

The Times’s executive editor is Dean Baquet, who was born in 1956. He is a consummate newspaperman, having started working in New Orleans even before graduating from Columbia University, in 1978. He moved from The Times-Picayune, in New Orleans, to the Chicago Tribune in 1984, where he won one Pulitzer Prize, and just missed another, before joining TheTimes, in 1990. Tribune Co. hired him back in 2000 to serve as managing editor of its newly acquired Los Angeles Times; he replaced John Carroll as editor in 2006 but was quickly dismissed after opposing newsroom budget cuts. He returned to The Times later that year as its Washington bureau chief, became its managing editor in 2011, and succeeded Jill Abramson in the top newsroom job in 2014.

Baquet is also a Black man, the fourth of five sons of a successful New Orleans restaurateur. Many years will be required to hash out all that has happened on his watch, some of it under the heading of “woke.” Baquet will write a book. Culture wars will continue. The equitable distribution of attention – of “play” – will become the next editor’s problem. Baquet turns 65 later this month; he will retire next year.

Leigh Montville won the Associated Press Sports Editors Red Smith Award in 2015; he never got out of the sportswriting ghetto, but he nevertheless became one of the finest columnists of his generation, pure and simple. Dean Baquet broke race out of the newspaper ghetto and made it ROP, maintaining news values evolved by the modern profession. He will enter history books as one of The New York Times’s greatest editors. Both men made the most of their opportunities.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

Maybe to Hell but at least moving

Silver Lake Railroad at center of Silver Lake village, part of Madison, N.H., where e.e. cummings (as he signed himself) had a weekend and summer place. He died at a hospital in nearby North Conway.

“America makes prodigious mistakes, America has colossal faults, but one thing cannot be denied: America is always on the move. She may be going to Hell, of course, but at least she isn't standing still.”

— E.E. Cummings (1894-1962), American poet and essayist. He was born in Cambridge, Mass., and is buried at Forest Hills Cemetery in Boston.

Joy Farm, also now known as the E.E. Cummings House, a National Historic Landmark

‘Adding and subtracting layers’

“Railroad Ties” (oil and cold wax on panel), by Helen Shulman, at Edgewater Gallery, Middlebury, Vt.

The gallery says:

“Helen Shulman’s abstract, mixed-media paintings draw on her interest in the manipulation of surface texture, color, and mark making, and are compositions that may have their origins in the landscape or the figure but become about the process of adding and subtracting layers, creating texture, and interest that will draw the viewer in and through each piece.’’

John Hancock gives employees 5 more days off

The three John Hancock buildings in Boston. The two older structures are reflected in the façade of the newest. The Stephen L. Brown building is the low, flat one.

BOSTON

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

“Boston-based John Hancock Life Insurance Co. and its parent company, Toronto-based Manulife Financial Corp., recently announced that it would be granting employees an additional five personal days. With the continuation of the COVID-19 pandemic, the company is taking this step in an effort help their employees stay both mentally and physically healthy.

“Along with the additional personal days, John Hancock employees have been taking part in ‘Fuel Up Fridays.’ These sessions are meant to give employees a chance to grow and help workers avoid burnout. This announcement came after CEO Marianne Harrison–named a 2020 ‘New Englander of the Year’ by The New England Council —informed the Boston area workers that the offices would not fully reopen their offices until January 2022.

“‘I know some of you were looking forward to being back in the office, so this news will be disappointing… However, we do feel this is the right choice for our colleagues’ well-being and in support of public health in the communities where we live and work,’ wrote Harrison in an email to employees.’’

Lindsay Koshgarian: The wasted opportunities since 9/11

Flight paths of the 9/11 murderers

Via OtherWords.org

NORTHAMPTON, Mass.

Twenty years have now passed since 9/11.

The 20 years since those terrible attacks have been marked by endless wars, harsh immigration crackdowns and expanded federal law enforcement powers that have cost us our privacy and targeted entire communities based on nothing more than race, religion, or ethnicity.

Those policies have also come at a tremendous monetary cost — and a dangerous neglect of domestic investment.

In a new report I co-authored with my colleagues at the National Priorities Project at the Institute for Policy Studies, we found that the federal government has spent $21 trillion on war and militarization both inside the U.S. and around the world over the past 20 years. That’s roughly the size of the entire U.S. economy.

Even while politicians have written blank checks for militarism year after year, they’ve said we can’t afford to address our most urgent issues. No wonder these past 20 years have been rough on U.S. families and communities.

After often strong growth from 1970 to 2000, household incomes have stagnated for 20 years as Americans struggled through two recessions in the years leading up to the pandemic. As pandemic eviction moratoriums end, millions are at risk of homelessness.

Our public-health systems have also been chronically underfunded, leaving the U.S. helpless to enact the testing, tracing, and quarantining that helped other countries limit the pandemic’s damage. Over 650,000 Americans have died from COVID-19 — the equivalent of a 9/11 every day for over seven months. The opioid epidemic claims another 50,000 lives a year.

Meanwhile, such extreme weather events as wildfires, hurricanes and floods have grown in frequency over the past 20 years. The U.S. hasn’t invested nearly enough in either renewable energy or climate resiliency to deal with the increasing effects climate change has on our communities.

In the face of all this suffering, it’s clear that $21 trillion in spending hasn’t made us any safer.

Instead, the human costs have been staggering. Around the world, the forever wars have cost 900,000 lives and left 38 million homeless — and as the disastrous withdrawal from Afghanistan has shown us, they were a massive failure.

Our militarized spending has helped deport 5 million people over the past 20 years, often taking parents from their children. The majority of those deported hadn’t committed any crime except for being here.

And it has paid for the government to listen in on our phone calls and target communities for harassment and surveillance without any evidence of crime or wrongdoing, eroding the civil liberties of all Americans.

Fortunately, there’s a silver lining: We’ve found that for just a fraction of what we’ve spent on militarization these last 20 years, we could start to make life much better.

For $4.5 trillion, we could build a renewable, upgraded energy grid for the whole country. For $2.3 trillion, we could create 5 million $15-an-hour jobs with benefits — for 10 years. For just $25 billion, we could vaccinate low-income countries against COVID-19, saving lives and stopping the march of new and more threatening virus variants.

We could do all that and more for less than half of what we’ve spent on wars and militarization in the last 20 years. With communities across the country in dire need of investment, the case for avoiding more pointless, deadly wars couldn’t be clearer.

The best time for those investments would have been during the past 20 years. The next best time is now.

Lindsay Koshgarian directs the National Priorities Project at the Institute for Policy Studies. She’s the lead author of the new report “State of Insecurity: The Cost of Militarization Since 9/11’’. She lives in Northampton.

On the Connecticut River in Northampton

David Warsh: America’s fracturing ‘politics of purity’ since the ‘70s

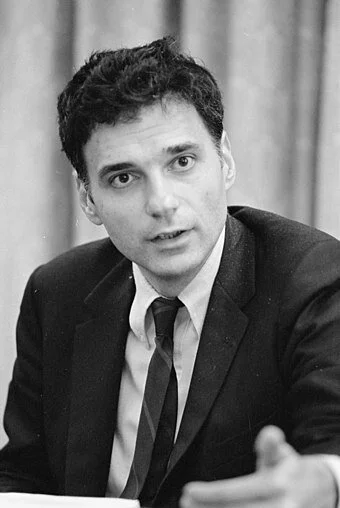

Ralph Nader in 1975, in his heyday

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Like a lot of people, I am interested in what has been happening in the world, the U.S. in particular, since the end of World War II. I am especially intrigued by goings on in university economics, but I take a broad view of the subject. I grew up in the Fifties, and the single most persuasive account I’ve found of the underlying nature of changing times since 1945 has been a series of five books by historian Daniel Rodgers, of Princeton University. In Age of Fracture (Belknap, Harvard, 2011), Rodgers described very well my experience of the increasingly thinner life of things.

Across the multiple fronts of ideational battle, from the speeches of presidents to books of social and cultural theory, conceptions of human nature that in the post-World War II era had been thick with context, social circumstance, institutions, and history gave way to conceptions of human nature that stressed choice, agency, performance and desire. Strong metaphors of society were supplanted by weaker ones. Imagined collectivities shrank; notions of structure and power thinned out. Viewed by its acts of mind, the last quarter of the century was an era of disaggregation, a great age of fracture.

But I’m always interested in a new narrative. One such is Public Citizens: The Attack on Big Government and the Remaking of American Liberalism (Norton, 2021), by historian Paul Sabin, of Yale University. Sabin employs the career of Ralph Nader, the arc of which extends from Harvard Law School and auto-safety crusader in Sixties to his Green Party candidacy in the U.S. presidential election of 2000, as a metaphor for a variety of other liberal activists who mounted assaults of their own on centers of government power in the second half of the 20th Century.

The harmonious post-war partnership of business, labor and government proclaimed in the Fifties by economist John Kenneth Galbraith and New Dealer James Landis, symbolized by the success of the Tennessee Valley Authority’s government-sponsored electrification of the rural South, was not built to last. But how did government go from being the solution to America’s problems to being the cause of them? It was more complicated than Milton Friedman and Ronald Reagan, Sabin shows.

Jane Jacobs (The Death and Life of Great American Cities, 1961), Rachel Carson (Silent Spring, 1962) and Nader (Unsafe at Any Speed. 1965), were exemplars of a new breed of critics of capture industrial manipulation and capture of government function, Sabin writes. Jacobs attacked large-scale city planning and urban renewal. Carson exposed widespread abuses by the commercial pesticide industry. Nader criticized automotive design. These were only the first and most visible cracks in the old alliance of industries, labor unions and federal administrative agencies. Public-interest law firms began springing up, loosely modeled on civil-rights organizations. The National Resources Defense Council; the Conservation Law Foundation; the Center for Law and Social Policy and many other start-ups soon found their way into federal courts. Nader tackled the leadership of the United Mineworkers Union, leading then-UMW President Tony Boyle to order the murder of reform candidate Tony Yablonski, his wife, and daughter, on New Year’s Eve, 1969.

In Age of Fracture, Rodgers wrote that “The first break in the formula that joined freedom and obligation all but inseparably together began with Jimmy Carter.” Carter’s outside-Washington experience as a peanut farmer and Georgia governor, as well as his immersion in low-church Protestant evangelical culture led him to shun presidential authority. “Government cannot solve our problems, it can’t set our goals, it cannot define our vision,” he said in 1978.

Sabin takes a similar view but offers a different reason for the rupture. Caught in between the idealistic aspirations of outside critics inspired by Nader and the practical demands of governing by consensus, Carter struggled to maintain the traditional balance but failed to placate his critics. “Disillusionment came easily and quickly to Ralph Nader,” Sabin writes. “I expect to be consulted, and I was told that I would be,” Nader complained almost immediately. Reform-minded critics attacked Carter from nearly every direction. A fierce primary challenge by Sen. Edward M. Kennedy (D.-Mass.) failed in 1980. The stage was set for Ronald Reagan.

Sabin recalls the battles of the 1970s with grim determination to show the folly of politics of purity. Nader made his first run for the presidency as leader of the Green Party in 1996, challenging Bill Clinton and Bob Dole. He was in his sixties; his efforts were half-hearted. In his second campaign, in 2000, he campaigned vigorously enough to tip the election to George W. Bush. Even then it wasn’t Nader’s last hurrah. He ran again, in 2004, as candidate of the Reform Party; and a fourth time, as an independent, in 2008. At 87, he is today conspicuously absent from the scene.

The public-interest movement initiated by urbanist Jane Jacobs, scientist Rachel Carson and Ralph Nader was effective in its early stages, Sabin concludes. The nation’s air and water are cleaner; its highways and workplaces safer; its cities more open to possibility. But Sabin is surely right that all too often, go-for-broke activism served mainly to undermine confidence in the efficacy of administrative government action among significant segments to the public.

The critique of federal regulation was clearly not the whole story, any more than was The Great Persuasion, undertaken in 1948 by the Mont Pelerin Society, pitched unsuccessfully in 1964 by presidential candidate Barry Goldwater, and translated into slogans in 1980 by Milton and Rose Friedman. Nor is the thoroughly disappointing 20-year aftermath to 9/11, another day when the world seemed to many to “break apart,” as historian Dan Rodgers put it in an epilogue to Age of Fracture.

What might put it back together? Accelerating climate change, perhaps. But that’s another story.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first appeared.

'Stay and wonder'

The Rudyard Kipling House is a Shingle Style house on Kipling Road in Dummerston, Vt., a few miles outside Brattleboro. The house was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1993 for its association with the English author Rudyard Kipling (1865–1936), who had it built in 1893 and made it his home until 1896. It is in this house that Kipling wrote Captains Courageous, The Jungle Book, The Day's Work, and The Seven Seas, and did work on Kim and The Just So Stories. The house is now owned by the Landmark Trust, and is available for rent.

“And there is nothing uprooted that is not changed.

Better to stay and wonder in the half light

How New England saunters where Kipling loved and ranged, so

And watch the starling flocks in first autumn flight.’’

— From “Thoughts of New England,’’ by Ivor Gurney (1890-1937), English composer and poet

But you never find it

“In Search of Lost Time,’’ by Salvatore Del Deo, in the group show “The Mysterious’’, at Berta Walker Gallery, Provincetown, Mass., through Sept. 12.

The gallery says:

“{Provincetown-based} Salvatore Del Deo is a painter engaged in a spirited dialogue with his work, responding to the deep questions presented by the paintings themselves. It is this challenge that has held Del Deo's passion through the over 50 years of his painting career and has resulted in an immense and diverse body of work. His is a style that seems to traverse the continuum from the realistic to the abstract, with a natural fluidity available only to one who is thoroughly centered. Del Deo has painted all the familiar scenes of his life at land's end – fish, dunes, figures on the back beach, boats moored at the town wharf, trap sheds and lighthouses – made new for the viewer through the painter's rich palette and soulful perspective. It is as if he is focusing long-stored energy through the lens of pure color – the color concentrated, coagulated by that intense focus.’’

Mr. Del Deo also has a beloved Provincetown restaurant called Sal’s Place.

‘This piece of paradise’

From Barbara Gilson’s photography show at Dedee Shattuck Gallery, Westport, Mass., Sept. 11-Oct 10.

She explains:

“In the fall of 2020, I traveled from Portland, Ore., to arrive in South Dartmouth, Mass., to quarantine for two weeks before I was able to safely visit my family and spend time with my 92-year-old mom. I was so lucky to have this extended time in this landscape and very grateful to wander this piece of paradise.

“It was 70 degrees some of the days, snowed on Halloween, and when the winds stirred they rattled the windows and doors of the wooden structure I was lodged in.

“I began each day looking out onto the {Slocum} river and ended each day looking out onto the river. In between I wandered, hiked, always with my camera in hand.

“Alone, amidst the open sky, wide stretches of rivers and bays, I ventured into the maze of wetlands and trails, enchanted by the endless variations in light as it transformed the landscape.’’

The gallery manager was busy

“Already, by the first of September, I had seen two or three small maples turned scarlet across the pond, beneath where the white stems of three aspens diverged, at the point of a promontory, next the water. Ah, many a tale their color told! And gradually from week to week the character of each tree came out, and it admired itself reflected in the smooth mirror of the lake. Each morning the manager of this gallery substituted some new picture, distinguished by more brilliant or harmonious coloring, for the old upon the walls.’’

— From Walden, by Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862)

Clean-up operation

“Fine Dining” (oil on canvas), by Joan Baldwin, at the Kingston Gallery, Boston, through Sept. 26. She works out of a studio at River Street Artists, part of Waltham Mills Artists Association, in Waltham, Mass.

Chris Powell: Conn. doesn’t need bears; who’s paying the rent?

Black bear

MANCHESTER, Conn.

When Connecticut state legislators next put a survey in their "constituent service" mailings, it should include the question: How many bears will you accept in your neighborhood before Connecticut authorizes bear hunting?

Of course most people don't want any bears nearby. But then they don't like the idea of shooting them either, even as bear sightings have increased sharply in the state in recent years, along with home break-ins by bears, bear damage to crops and livestock, and highway crashes caused by bears.

The logic of Connecticut's laissez-bear policy is that eventually every town in the state will have at least a few dozen. Then no backyards, playgrounds, farms and streets will be safe. Even finding a discreet spot for smoking marijuana may become impossible, since while sale and possession of the drug are now legal, towns are already using zoning regulations to prohibit dispensaries and public smoking, marijuana being OK in principle but dope smokers being even less popular than bears. If the bears claim the woods, where will dope smokers go?

Zoning may prevent poor people from moving into leafy suburbs but bears won't comply. Sedating and relocating bears is no longer an option, their population already having exceeded what the state's wilderness areas can support. Waving bears away toward next door or the next town is no solution either, for another bear will follow soon enough.

It's not that Connecticut's bears (which are black bears) are so dangerous. They're not grizzlies. But they're not compatible with civilization either. Everything has to stop when a bear wanders by looking for food, and the animals do damage.

Trouble is always best handled by prevention. Like other hunting, bear hunting can be kept safe by regulation, and not much of it would be necessary in Connecticut if it was undertaken regularly in the northwest part of the state. Deer, while also cute, are often troublesome, too, and the state already authorizes and regulates deer hunting.

Even with bear hunting on top of deer hunting, Connecticut will have plenty of wildlife. Chipmunks, rabbits, woodchucks, foxes, opossums, raccoons, bobcats, squirrels, coyotes, weasels, beavers, birds and more will continue to delight and sometimes annoy everyone. But nature is not always harmless. The state can do without bears just as it can do without wolves and alligators.

xxx

With infinite money now at their disposal, how have the federal government and state government managed to botch the rental-housing problem so badly?

Government's closure orders during the virus epidemic crippled the economy and put millions of people out of work. Many couldn't pay their rent, so then government forbade evictions, disregarding constitutional requirements that property cannot be taken for public use without fair compensation.

Eventually rent-reimbursement funds were created but not before many landlords were ruined or nearly ruined financially, and even now much of the money has not been distributed, in part because, with evictions forbidden, renters have had little incentive to apply -- just as people have had little incentive to return to work while unemployment compensation exceeds their former wages.

A few weeks ago the federal Centers for Disease Control claimed the authority to forbid evictions. President Biden said this was probably unconstitutional but went along with it. The Supreme Court rejected it the other week.

Maybe the government should have simply instructed landlords to send their defaulted rental bills to a government agency for payment. Of course such a system would have invited substantial fraud, but at least it would have been constitutional.

This mess makes even more ridiculous the sanctimonious prattle about housing that filled the General Assembly a few months ago -- the prattle that housing is "a human right."

Rights are things people possess without having to pay for them, such asb freedom of speech and religion. There is no housing unless somebody pays for it. But housing can be arranged if the money is appropriated.

Of course, the state legislators proclaiming that housing is a human right declined to appropriate any money so that housing would be free like other rights. The legislators meant only to strike a pious pose. Could they just try to get the overdue rents paid?

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer in Manchester.

And where is it?

“Even if the place has a McDonald's,

the help may only work there,

live outside of town,

be so young they don't care about

museums, churches, health-food stores, dances,

or whether the town is on a map….’’

— From “Lost Is the Farthest Place,’’ by Richard Gillman (1929-2004), American poet and university administrator. He lived the later part of his life in Waterville, Maine, home of Colby College (and its large art museum).

Miller Library at Colby College

Caitlin Faulds: How do users interpret warnings about coastal water quality?

Misquamicut Beach, in southern Rhode Island

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

A new study on perceptions of coastal water quality shows users may have more difficulty interpreting warning signs than previously thought.

The University of Rhode Island study, recently published in the Marine Pollution Bulletin, surveyed more than 600 recreational users around Narragansett Bay regarding their understanding of water quality to find that water quality had “multiple meanings.” A complicated conceptualization of water quality could have big implications for water policy and management.

“Water quality is pretty complex for people,” said Tracey Dalton, a URI marine affairs professor and Rhode Island Sea Grant director, who co-authored the study. “It’s not as simple as the chemical components that we tend to manage for.”

Water quality managers typically look at a variety of biochemical and physical indicators, including nutrients, temperature, acidity, oxygen levels, phytoplankton, fecal coliform and enterococci, to see if a site meets surface water quality guidelines set by the Environmental Protection Agency and outlined in the Clean Water Act.

But, according to the recent study led by URI marine affairs doctoral candidate Ken Hamel, these indicators can be difficult to understand for beachgoers, who more commonly tote sunscreen and beach towels than sterile sample bottles, plankton nets or conductivity, temperature and depth (CTD) sensors.

With help from his research team, Hamel conducted hundreds of in-person surveys at 19 sites along the Rhode Island shoreline. They asked recreational users to grade water quality in the area on a scale from 1 to 10, and then explain the reasons for their score.

Users generally perceived water quality in upper Narragansett Bay to be worse than in the lower bay. This assessment aligned fairly well with biochemical reports in the area, Hamel said, generally cleaner on the southern, open end of the bay than in the more urban, post-industrial north.

“You’ve got to wonder … how do people make that judgment,” he said. “Because they don’t necessarily know how much sewage effluence is in the water. They can’t see E. coli or enterococcus. They can’t smell it. Nutrients are also invisible.”

After a statistical analysis of the responses, the survey showed nearly 23 percent of users based water quality determinations on the presence of macroalgae or seaweed.

“Seaweed, which is a perfectly ecologically healthy organism for the most part — people perceive that as a water quality problem,” Hamel said. “From a Clean Water Act perspective, [seaweed in] the north is a water quality problem, the south is not.”

In the northern reaches of Narragansett Bay, macroalgal concentrations are often the result of nutrient overload, especially nitrogen and phosphorous borne of fertilizers and road runoff. It can indicate a problem with marine water quality.

But further south, macroalgae are less associated with pollution and are not necessarily an indicator of nutrient enrichment or water degradation, according to Hamel. Seaweed grows in reefs off the coast, breaks up due to wave action and can be blown on shore, especially on south-facing sands.

With no simple association between water degradation and seaweed, Hamel was surprised to see so many people use it as a basis for water quality determinations.

“There is very little research on perceptions of algae or seaweed period,” Hamel said. “It’s just a very understudied subject.”

Shoreline trash, “broadly defined” pollution, strong odor, water clarity, swimming prohibitions and nearby sewage treatment plants were also cited by beachgoers as indicators of poor water quality.

“People figured if there was a sewage plant nearby the water must be dirty,” Hamel said. “Although if you think about it, it’s slightly backward right. That should make the water a little bit cleaner.”

Another 9 percent of respondents also indicated that firmly held place beliefs played a role in water quality grades. These place beliefs, Hamel said, were “hard to pin down,” but were based primarily on the reputation of a place, whether linked to former industry or long-embedded regional knowledge of Narragansett Bay.

“One person even said, ‘This place is too upper bay.’ Like it was just common sense for them that water in the upper bay must be bad,” Hamel said.

Narragansett Bay visitors with water-quality questions can find detailed reports for sites through the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management and through the Narragansett Bay Commission. But, according to Hamel, the survey shows a need and opportunity to better engage beachgoers in water quality education, so the average recreation user can more accurately read the warnings presented in an environment.

“As a group of social scientists, we’re really interested in understanding how people are connected to their environment,” Dalton said. “From a policy perspective, it's really important to understand what the general public thinks since they’re the ones who are going to coastal sites, they’re the ones affected by policies.”

The Clean Water Act, Hamel said, has gaps in the way it was written and interpreted by water managers. As set out in 1972, the federal law mandated that states reduce and eliminate pollutants primarily to protect wildlife and recreation. Nicknamed the “fishable/swimmable goal,” the law gives priority to recreational users.

The law is enforced at the state level, with slight variations in procedure, though it typically takes the form of measuring and monitoring biochemical and physical variables. But, according to Hamel, that strategy can leave out certain stakeholders and minimize non-user concerns.

“There’s a lot of other people that use the water that aren’t necessarily in it or on it,” he said. “And their … perspectives aren’t really considered by the way the Clean Water Act is implemented.”

There isn’t necessarily anything wrong with the law, Hamel said, and it has been instrumental in improving water quality. But policymakers and managers could better address all stakeholders and “more explicitly consider” the needs of non-users, he said, including those who may work or live nearby.

“In terms of how we direct our investments and direct our funds, we want to make sure that we’re also addressing what people care about,” Dalton said. “It’s really important to ground that in what the understanding is of the concept of water quality.”

Caitlin Faulds is an ecoRI News journalist.

Light-headed

“Ugly duck” (limited edition archival pigment print on fine art paper), by Flora Borsi, in her show “Identity: The Self-Portrait Series,’’ at Lanoue Gallery, Boston, through Sept. 20.

What can be endured?

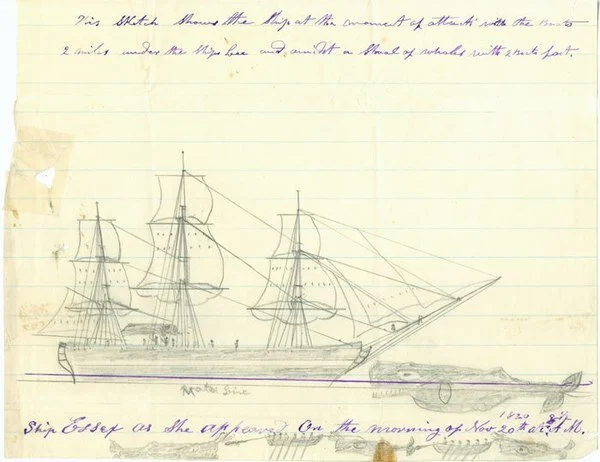

Sperm whale striking The Essex on Nov. 20, 1820 (sketched by Thomas Nickerson)

“There is no knowing what a stretch of pain and misery the human mind is capable of contemplating when it is wrought upon by the anxieties of preservation; nor what pangs and weaknesses the body is able to endure, until they are visited upon it; and when at last deliverance comes, when the dream of hope is realized, unspeakable gratitude takes possession of the soul, and tears of joy choke the utterance.’’

-- Owen Chase, sailor, in Narrative of the Most Extraordinary and Distressing Shipwreck of the Whale-Ship Essex, of Nantucket

Here’s an edited version of a good Wikipedia summary of the background of this horror story:

“The Essex was a whaler from Nantucket launched in 1799. In 1820, while in the Pacific Ocean under the command of Capt. George Pollard Jr., she was attacked and sunk by a sperm whale. Thousands of miles from the coast of South America with little food and water, the 20-man crew was forced to try to make for land in the ship's surviving whaleboats.

“The men suffered severe dehydration, starvation, and exposure on the open ocean, and the survivors eventually resorted to eating the bodies of the crewmen who had died. When that proved insufficient, members of the crew drew lots to determine whom they would sacrifice so that the others could live. A total of seven crew members were cannibalized before the last of the eight survivors were rescued, more than three months after the sinking of The Essex. First mate Owen Chase and cabin boy Thomas Nickerson later wrote accounts of the ordeal. The tragedy attracted international attention, and inspired Herman Melville to write his 1851 novel Moby-Dick.’’

Those old small-town reports

The Cohasset Common still looks much as it did in the ‘50s except the elms are gone because of Dutch Elm Disease.

Still the venue of generally polite town meetings

— Photo by ToddC4176

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The other day I looked at municipal reports of my hometown, Cohasset, Mass., in the late ‘50s, when I lived there. There have been big changes since then, among them that Republicans outnumbered Democrats by more than 5 to 1, reflecting the old allegiances of small-town New England Yankees back then: The town’s Democratic now. And they called the town dump the “town dump’’ instead of the euphemism of Cohasset’s current “Recycling Transfer Station’’.

The old reports’ language was a bit more formal than now, indeed sort of Victorian, to wit, in the late ‘50s: “That the Selectmen are instructed to advise His Excellency the Governor and our Senators and Representatives….” And nicknames are frequently used now in the reports, a practice unheard of back then.

There were also such reminders of the passage of time as Memorial Day being called Decoration Day (in my house we still called Veterans Day Armistice Day back then) and a plan to spray a wetland with DDT, the environmental menace that wouldn’t be banned until 1972. But perhaps the most noticeable change was that most of the names of town officers in the reports in the late ‘50s were WASP, and now there are lots of Irish and Italian names, and some names whose ethnicity is hard to figure. Those once-city dwellers left the city to move to the suburbs, including now-rich ones such as Cohasset.

But I was charmed to read that the town still has that old colonial occupation of “fence viewers,’’ charged with dealing with property disputes.

You can learn a bit of local culture and sociology by reading old small-town reports.