But don't think about the Mu variant

“By the River” (acrylic), by Massachusetts painter Ricardo Maldonado, in the group show “Reflection/Reawakening/Resilience,’’ at the Lexington (Mass.) Arts and Crafts Society, Sept. 10 to Oct 3.

The morality of nature

Louise Dickinson Rich’s former house in rather remote Upton, in western Maine.

Lake Umbagog

“Nature is strictly moral. There is no attempt to cheat the Earth my means of steel vault of bronze coffin. I hope that when I die I too may be permitted to pay at once my oldest outstanding debt, to restore promptly the minerals and salts that have been lent to me for the little while that I have use for blood and bone and flesh.”

―Louise Dickinson Rich (1903-1991), a once well known writer of fiction and nonfiction works, most set in Maine and Massachusetts.

Her best-known work was her first book, the autobiographical We Took to the Woods (1942), set in the 1930s when she and husband, Ralph, and a friend lived in a remote cabin near Lake Umbagog, Maine. She was born in Huntington, Mass., and died in Mattapoisett, Mass.

At the Mattapoisett town dock, off Buzzards Bay

Timeless sky

“I passed by the fence

and looked up,

and whatever happens

happened to make that sky

seem timeless,

awash with well-being….’’

— From “A Green Evening, September, 1952,’’ by Brendan Galvin (born in 1938), American poet. He was born in Everett, Mass., and now lives in Truro, Mass., on Cape Cod.

The grand Parlin Memorial Library, in Everett

— Photo by Elizabeth B. Thomsen

Space/time

“Wormhole” (ink on masonite), by Hampton, N.H.-based Bill Oakes, in the group show “Renewal,’’ with Barbara D’Antonio and Gene Galipea, at Haley Art Gallery, Kittery, Maine, Sept. 9-Nov. 19.

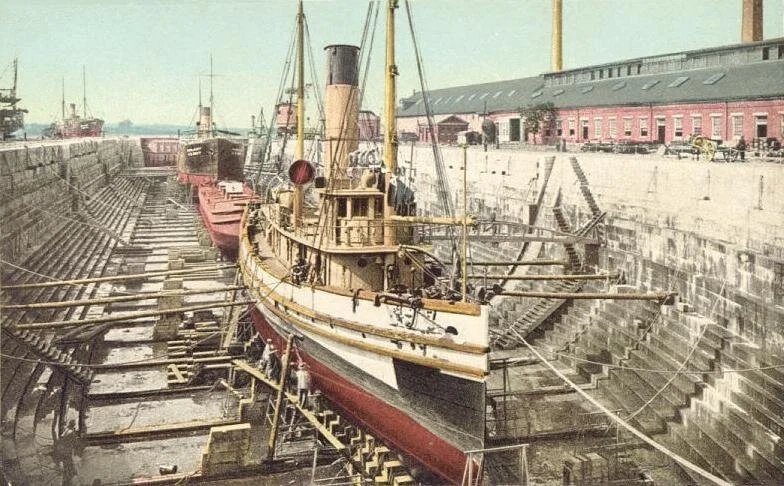

Shipyard dry dock in Kittery, circa 1908

Llewellyn King: As climate warms, utilities must become much more resilient

The severe flooding in Greater New York, New Jersey and New England from the remnants of Hurricane Ida, that storm’s devastation in New Orleans and much of the rest of Louisiana and the winter freeze in Texas usher in a new reality for the electric industry, showing how outdated their infrastructure has become and how they have to much more expect the unexpected.

Resilience is the word used by the utilities to describe their ability to speedily restore power, to bounce back after an outage. This year, resilience has been put to the test with major challenges affecting electric utilities from coast to coast. Mostly, the results have been disappointing to catastrophic.

It is reasonable to believe that resilience means that if there is an outage power will be back on forthwith or within hours, and that is often the case.

But as the attacks on the system from aberrant weather have become more frequent and severe, the bounce back has been closer to struggle back slowly.

Two cases tell a tale of catastrophe. Recently, the complete loss of electricity to New Orleans during Hurricane Ida, much of which is still in the dark and with people suffering without water in their homes, along with the absence of light, air conditioning, or the ability to charge a cell phone.

Even before Ida tore into the Gulf Coast, teams from other utilities were on their way to help. ConEd in New York was one of many utilities that had trucks rolling to the scene before Ida hit. That kind of quick, fraternal response is often what is meant by resilience. Bold and well-coordinated though it may have been, it was not nearly enough. Entergy, which supplies the power to the area, failed the resilience test.

The other standout was in the failure of the Texas grid when Winter Storm Uri struck in the middle of February. It froze much of Texas for five days and more than 150 people died, some by freezing to death in their homes. The unfortunately named Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT), which operates the electric grid of Texas, abominably failed the resilience test.

Some of the natural-gas supply was cut off during the deep freeze because the system hadn’t been weatherized, but the gas that did flow also flowed money.

The gas operators made enormous profits, including Energy Transfer, which made $2.4 billion. Not only had the gas operators not signed on to the concept of resilience, but the idea of commonweal was absent.

While electric utilities -- there are a few large electric utilities and more than 80 small ones in Texas -- struggled to honor their mandate to serve, the gas suppliers, according to those in the electric utility industry, served their mandate only to their shareholders.

Rayburn, the electric cooperative that has a service area near Dallas, spent what it had budgeted for three years in just five days on gas purchases, CEO David Naylor told me.

On my PBS show, White House Chronicle, Paula Gold-Williams, president and CEO of CPS Energy, the large, municipally owned gas and electric utility in San Antonio, said she thought that the suppliers of gas to electric generators should be regulated as Texas utilities are.

Wildfires in the West, storms in the East and up the center of the country have put a huge strain on the electric utilities. What is clear is that “resilience” needs to be defined in a much broader sense. That whole infrastructure of the electric-utility industry needs to be re-examined with a view to surviving monstrous weather. The cost in lives and in treasure is very high when electricity, the essential commodity of modern life, fails.

This new imperative comes at a bad time for the electric-utility industry, which is struggling with daily cyber-attacks, converting from fossil fuels to alternatives, and straining to find new, durable storage systems.

One of the trends to greater security is to encourage microgrids – small, self-contained grids that can store and generate electricity, often from renewables like solar. These can disengage from the grid in times of stress and continue providing power to the microgrid.

Other suggestions include undergrounding electric lines. California’s Pacific Gas and Electric has proposed undergrounding 10,000 miles of lines to counter wildfires sparked by downed cables. The cost might be insupportably high -- over $1 million a mile in level ground, according to one estimate.

Entergy, according to The Energy Daily, has 2,000 miles of lines down in New Orleans. Burying just the most vulnerable lines in the nation would be a massive civil engineering undertaking at a daunting cost. Other ideas, please?

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Long Island Expressway in New York City shut down due to flooding as the remnants of Hurricane Ida swept through the Northeast on Sept. 1-2

— Photo by Tommy Gao

Fried in Rockport

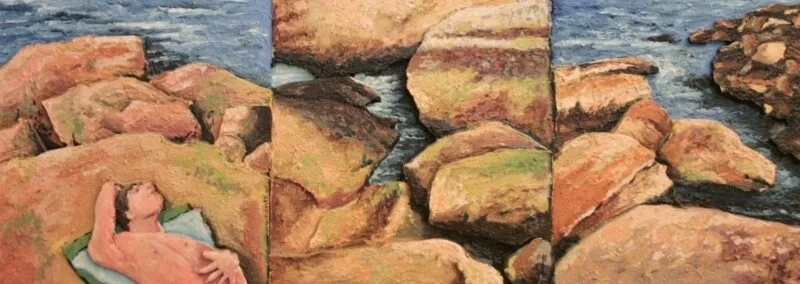

“Sunbather Rocks at Halibut Point’’ (Rockport, Mass.) (mixed media on wood), by Marja Lianko, in the Collection of the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester.

George McCully: Rauch book tries to ‘socialize knowledge’

“Knowledge’’ (1896), by Robert Reid, at the Thomas Jefferson Building, Washington, D.C.

BOSTON

From The New England Journal of Higher Education (NEJHE), a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Book Review

The Constitution of Knowledge: A Defense of Truth; Jonathan Rauch; Brookings Institution Press; Washington D.C.; 2021.

Reviewed by George McCully

This is a prominent and timely book by a distinguished journalist on a subject of profound national significance, especially for our educational and scholarly professions as NEJHE has previously noted. Yet, despite its many admirable features and high praise from leading commentators, I found the book’s argument and potential value fundamentally undermined by a surprising misconception of its central subject.

The book contends that, as with our national political Constitution, we have a “Constitution of Knowledge,” which works to channel our civic discourse in constructive directions by defining the bounds of proper intellectual customs. By acting as a filter for debates among contending parties, it sorts out true, good and beautiful ideas from their opposites, over time pointing us in progressive directions. This Constitution developed concurrently with our federal Constitution, over centuries leading to the Enlightenment, with the rise of “liberal science” and progressive ideals. Recent psychological experiments have shown, however, that humans can be and often are driven by irrational impulses to act selfishly and against the common good. The current revolution in information and communication technology has been used maliciously to favor and manipulate those impulses, as shown by our recent politics, especially under Trump. Therefore, we need now to revive and strengthen this Constitution of Knowledge in our politics and civil affairs. All this is certainly a plausible argument.

Plausible, but not persuasive. The epitome of its problems is its misleading title, promising far more than the book delivers. This is not a book about “knowledge” per se, but about public knowledge. It does not offer a defense of “truth” per se, but rather an extensively researched and fervent attack against current political malpractices of mis- and dis-information, with numerous suggestions of ways to oppose and avoid them. The result is that the whole argument is weaker than expected.

The book’s essential flaw is its socialization of “knowledge.” It does not consider an assertion to be valid or true unless it has persuaded people and been accepted socially. Rauch writes (emphases mine): “The only way to validate a [specific proposition] is to submit it to the reality-based community.” He adds: “[L]iberal science’s distinctive qualities derive from two core rules: … the fallibilist rule: No one gets the final say” and “the empirical rule: No one has personal authority … Crucially, then, the empirical rule is a social principle. …”

In other words, if you and I, in our research, make some new and original discoveries based on adequate evidence, those discoveries according to Rauch’s book are not “knowledge” until other people agree with them. I found his exclusively social emphasis about “knowledge” more than a bit weird. It reminded me of the old saw about the questionable sound of an unobserved tree falling in the middle of a forest, or perhaps more pointedly of the politically incorrect joke, “If I say something and my wife doesn’t hear it, is it still wrong?” By focusing on this socialization, the book fails to promote the simple but powerful antidote we need: namely, thinking on the basis of evidence—the routine practice of all modern scholarship, science and jurisprudence, accessible by all educators and citizens.

In fact, this socialized approach to knowledge is exactly what has rendered knowledge more, not less, vulnerable to the malicious and corrupt mis- and dis-information newly empowered by the IT revolution. It is what has caused, for example, a currently reported 88,000 people per week to fight Covid with the livestock de-wormer Ivermectin which they can buy from agricultural feed stores. In contrast, the authentic empirical practice of grounding knowledge in evidence is invulnerable by communications techniques. If what good citizens promote and defend is itself demonstrably unshakeable, the cause of truth in democracy can be more effectively strengthened and defended. This book shows no awareness of this.

Moreover, conceiving knowledge in exclusively sociopolitical terms has encouraged the odd analogy Rauch has drawn to a “Constitution of Knowledge” comparable to our federal Constitution in that it governs (public) knowledge. But this comparison is obviously flawed—the alleged “Constitution of Knowledge” has no Article VI, Section 2, explicitly making it the “supreme law of the land” nor Article III, Section 1, vesting “judicial power in one supreme court” of a few officials, backed by a huge and elaborate law enforcement apparatus. Participation in Rauch’s “Constitution of Knowledge” is purely voluntary. While it is customary though not infallible among professionals, it does not guide popular thinking or discussion outside the professions and is highly vulnerable by today’s hyper-powerful communications technology in vicious hands.

In short, this important book is basically at odds with itself. While it is true that the public in general does not “think on the basis of evidence” and relies for verification on trusting other people, this is what has caused the much-discussed epistemic crisis of our democracy. Our resulting sociopolitical polarization and mutually antagonistic tribal cultures are what prevent our electorates and representatives from objectively deciding on the relative merits of various candidates and ideas. The symbiosis of journalism with civil opinions, which Rauch’s book exemplifies, is at the heart of our crisis. We need journalism and public discourse to be based on and promoting reliance on evidence, not public opinions.

I am reluctant to say this, but to this journal’s readership it bears notice: The strangeness to us of this book’s argument derives from its journalistic, rather than scholarly or scientific, habit. The sea in which journalism swims is entirely sociopolitical; that is why “fairness” and “balance” in reporting various perspectives have long been promoted as criteria of public value by schools of professional journalism. For journalists, it is understandable that “knowledge” is likely to mean “public knowledge” based on social acceptance. In contrast, the graduate schools that have trained us in professional research promote “truth” which we take to be synonymous with “knowledge” as our sole professional objective and criterion of value. For scholars (and scientists) “knowledge” is gained only by adherence to adequate evidence. Many of us in the course of our professional careers have made new and original factual discoveries, which we consider new “knowledge” even before their publication and indeed as an elementary criterion for publication in the first place.

This is a gap that needs now to be bridged, not smudged nor insisted upon. This means that we—the community of scholars and educators (including journalists)—have a substantial civic role and responsibility to collaborate in protecting democracy from its current detractors, by energetically teaching and promoting thinking on the basis of evidence in all public discourse, especially including popular journalism. When any assertion is made in civic arenas, the first question by journalists—always and predictably so that everyone becomes accustomed to it—should be, “What’s your evidence?”

George McCully is a historian, former professor and faculty dean at higher-education institutions in the Northeast, professional philanthropist and founder and CEO of the Catalogue for Philanthropy.

Import minorities?

]=

Schoolhouse built in 1832 in Sharon, N.H.

“I live in rural New Hampshire, and we are, frankly, short on people who are Black, gay, Jewish and Hispanic. In fact, we’re short on people. My town {Sharon} has a population of 301.’’

— P.J. O’Rourke (born 1947), American journalist and satirist

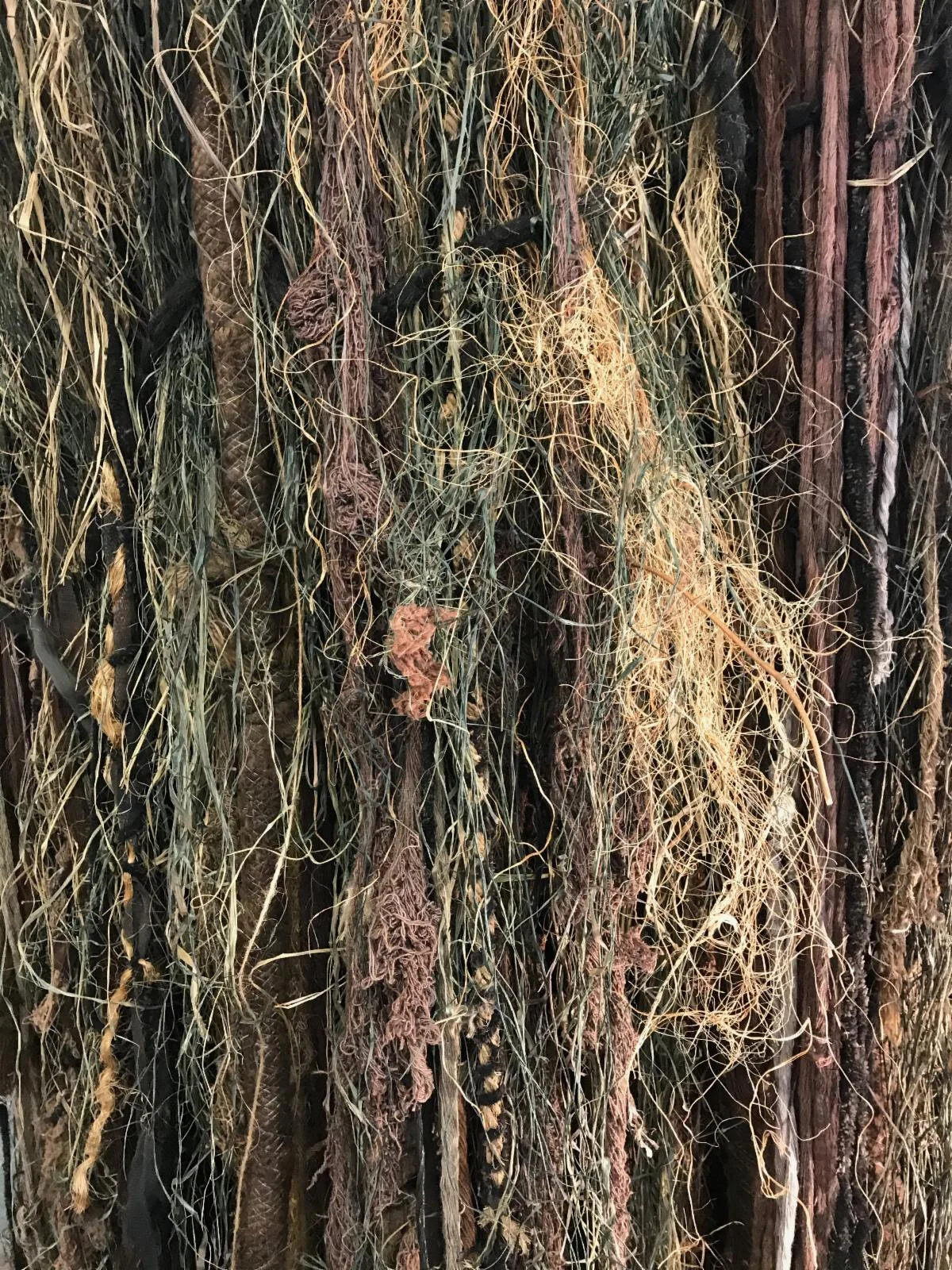

Fate in fiber

“Fate” (fiber), by Massachusetts artist Louise Farrell, this month at Kingston Gallery, Boston.

The gallery says that Ms. Farrell:

“contemplates and weaves together the stories of our lives in “Fate’’ After hearing of a dear friend suffering an unexpected and devastating setback, Farrell felt a resonance with the ancient Norse sagas that she was reading at the time. For the Norse, the symbol of life is represented through a sacred and immense tree named Yggdrasil. In the roots of this great tree are all of humanity’s histories, stories, and lives. Each root is unique; some are long and expansive, while some are very short. Her exhibition consists of a woven sculpture, monumental as an old-growth tree, in the center of the gallery. For Farrell, dyeing and attaching every rope and skein became a meditative process. Together, Fate is a journey through the universality of the human condition..

Some love hurricanes

Storm surge in eastern Connecticut during Hurricane Carol, on Aug. 31, 1954.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary, in GoLocal24.com

The hype about Tropical Storm Henri was extreme, even by New England storm standards. After all, Henri, at its height offshore as a minimal hurricane, had lighter winds than many winter Nor’easters that hit us.

But then, many people enjoy the hype and indeed like hurricanes, as long as their property isn’t damaged, and they get their electric power back within a day or two, which they usually do. Storms take people out of themselves by putting on a diverting show. And they jazz up late summer, when many people are tiring of the season, especially this year with its months of steamy weather. (How do people live in Florida year round?)

Hurricane Carol (Aug. 31, 1954), quickly followed by Hurricane Edna (Sept. 11, 1954) left many New Englanders without juice for up to two weeks. These days, utilities pump up an oncoming storm to ensure that they get timely help from utilities outside the region and that they won’t be blamed in those rare cases in which a storm turns out to be worse than forecast, such as last year’s Tropical Storm Isaias in Connecticut.

My most vivid memory as a boy of hurricanes, besides watching a couple of trees being uprooted, is the sweet smell of Sterno, which we used for cooking after the power went out.

Those Unsightly Lines

At India Point Park, Providence. Note power lines.

— Photo by Tim Burling

People in Providence’s Fox Point neighborhood, at the head of Narragansett Bay (or the head of the Providence River, if you prefer) who have fought for almost 20 years to get the utility lines from India Point Park to East Providence buried must have felt a pang when they read in GoLocal”

“The Scenic Aquidneck Coalition has announced the completion of a project to bury power and communication lines along Third Beach Road and Indian Avenue in Middletown, Rhode Island. Inspired by the 2017 Second Beach project, the Scenic Third Beach Project removes the rest of the poles on Sachuest Point along Third Beach and up Indian Avenue, promoting ‘coastal resiliency, restoring the historic landscape and enhancing the area’s scenic appeal.’’’

But the Middletown project only cost $4 million and was entirely paid with private donations. (There are plenty of rich individuals and organizations on Aquidneck Island.) The price of burying the Fox Point lines has risen to $33.9 million, and it remains uncertain how the cost would be shared among Providence and East Providence property-taxpayers and statewide electricity rate payers and taxpayers and National Grid – or other permutations and combinations.

I suspect that a big hurricane that takes out power for a long time would work wonders in getting those lines buried. Never waste a crisis.

Resurgent feminist art

“People Have Anxiety about Ambiguity” (collage), by Liza Basso, in the group show “Re Sisters: Speaking Up; Speaking Out ,’’ at Brickbottom Artists Association, Somerville, Mass., Sept. 9-Oct 10.

The gallery says:

“The current political climate has put women’s rights and civil rights at risk. This exhibition is meant to bring attention to the recent resurgence in feminist art and its connection to activism and politics, as women face rollbacks in reproductive rights, the disproportionate effects of Covid 19, and a year that saw more women elected to political office than ever before. Through collections that delve into histories that are political, personal, and shared, ReSisters explores the experiences of women in a post-trump era.’’

Dana Brown: Consider option of having the public own firms making generic drugs

Via OtherWords.org

It’s an all too familiar story. A company with some of the best-paying jobs around and a vital anchor for the community decides to engage in “restructuring” to “maximize long-term value creation.”

In other words, it closes down and lays off its workers in pursuit of bigger profits.

But the late July closure of the Viatris pharmaceutical plant in Morgantown, W.Va. — which employed close to 1,500 people and was the largest remaining generic-medications plant in the U.S. — is particularly galling. [There are several generic-drug companies in New England.}

West Virginia Gov. Jim Justice echoed a sentiment shared across the political spectrum when he said on August 4, “I think it’s pitiful, pitiful, absolutely pitiful that our federal government at this time, with something as critical as pharmaceuticals are to our citizens, is just deciding to sit on the sideline and let this catastrophe happen.”

The closing was uniquely preventable — if there had been federal or state action premised on prioritizing protecting public health and economic wellbeing over short-term shareholder returns. We had the tools. All that was lacking was the boldness and the political will to use them.

The chain of events started in 2020 when the plant’s then-owner, Mylan (run by Heather Bresch, West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin’s daughter), merged with Upjohn to form a new company, Viatris, creating the largest generics company in the world. Not long after, Viatris announced a “restructuring initiative” that included shuttering some of its plants, including the Morgantown facility.

The Steelworkers local representing many of the plant’s workers began petitioning both the incoming Biden administration and state officials to keep the plant open. Their key argument was its role in the country’s pharmaceutical supply chain, particularly in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The plant produced 18 billion doses of low-cost generics a year — including many essential medicines paid for through various federal programs.

A letter to the Biden administration signed by the Steelworkers and about 40 other health-care and advocacy groups (including The Democracy Collaborative, where I work) called for using the Defense Production Act to stop the closure of the plant.

One of President Biden’s first executive orders called for using the law if necessary for “acquiring additional stockpiles, improving distribution systems, building market capacity, or expanding the industrial base.” But the Biden administration, like the Trump administration before it, did none of these things in Morgantown.

Keeping the Morgantown plant open would have been a clear case of assuring local distribution and manufacturing capacity for an essential good: medicine. The designation that the plant already has from the Department of Homeland Security as critical infrastructure underscores that.

Overlooked was the opportunity to explore a public-ownership option in pharmaceuticals. Public enterprises are free from profit constraints and can instead define their bottom line based on what they contribute to public health, scientific advancement, and local economic resiliency.

The gains for our communities would be massive: Reliable access to affordable generics helps keep people out of hospitals and in jobs, schools, and community service roles. Generics dramatically reduce our overall health care costs. Plus, the manufacturing plants are vital economic engines as well as hubs of home-grown intellectual capital.

It is encouraging that a public institution, West Virginia University, announced talks with Viatris to acquire the plant, but that was after hundreds of highly skilled workers were needlessly laid off, most of whom cannot wait to see if a deal is struck before looking for new jobs.

What we really need in the face of continued outsourcing and offshoring is a real industrial strategy that includes public ownership — and puts community health above the demands of absentee shareholders.

Dana Brown is director of The Next System Project at The Democracy Collaborative, “a research and development lab for the democratic economy.”

David Warsh: Time to read ‘Three Days at Camp David’

The main lodge at Camp David

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The heart-wrenching pandemonium in Kabul coincided with the seeming tranquility of the annual central banking symposium at Jackson Hole, Wyoming. For the second year in a row, central bankers stayed home, amid fears of the resurgent coronavirus. Newspapers ran file photos of Fed officials strolling beside Jackson Lake.

Market participants are preoccupied with timing of the taper, the Fed’s plan to reduce its current high level of asset purchases. That is not beside the point, but neither is it the most important decision facing the Biden administration with respect to the conduct of economic policy. Whom to nominate to head the Federal Reserve Board for the next four years? For a glimpse of the background to that question, a good place to start is a paper from a a Bank of England workshop earlier in the summer

Central Bank Digital Currency in Historical Perspective: Another Crossroads in Monetary History, by Michael Bordo, of Rutgers University and the Hoover Institution, brings to mind the timeless advice of Yogi Berra: when you come to a crossroad, take it.

Bordo briefly surveys the history of money and banking. Gold, silver and copper coinage (and paper money in China) can be traced back over two millennia, he notes, but three key transformations can be identified in the five hundred years since Neapolitan banks began experimenting with paper money.

First, fiduciary money took hold in the 18th Century, paper notes issued by banks and ostensibly convertible into precious metal (specie) held in reserve by the banks. Fractional banking emerged, meaning that banks kept only as much specie in the till as they considered necessary to meet the ordinary ebb and flow of demands for redemption, leaving them vulnerable to periodic panics or “runs.” Occasional experiments with fiat money, issued by governments to pay for wars, but irredeemable for specie, generally proved spectacularly unsuccessful, Bordo says (American Continentals, French assignats).

Second, the checkered history of competing banks and their volatile currencies, led, over the course of a century, to bank supervision and monopolies on national currencies, overseen by central banks and national treasuries.

Third, over the course of the 17th to the 20th centuries, central banks evolved to take on additional responsibilities: marketing government debt; establishing payment systems; pursuing financial stability (and serving as lenders of last resort when necessary to halt panics); and maintaining a stable value of money. For a time, the gold standard made this last task relatively simple: to preserve the purchasing power of money, maintain a fixed price of gold. But as gold convertibly became ever-harder to manage, nations retreated from their fiduciary monetary systems in fits and starts. In 1971, they abandoned them altogether in favor of fiat money. It took about 20 years to devise central banking techniques with which to seek maintain stable purchasing power.

As it happens, the decision-making at the last fork in the road of the international currency and monetary system is laid out with great clarity and charm in a new book by Jeffrey Garten, Three Days at Camp David: How a Secret Meeting in 1971 Transformed the Global Economy (2021, Harper) Garten spent a decade in government before moving to Wall Street. In 2006 he returned to strategic consulting in Washington, after about 20 years at Yale’s School of Management, ten of them as dean.

The special advantage of his book is how Garten brings to life the six major players at the Camp David meeting, Aug. 13-15, 1971 – Richard Nixon, John Connally, Paul Volcker, Arthur Burns, George Shultz, Peter Peterson and two supporting actors, Paul McCracken an Henry Kissinger – and explores their stated aims and private motives. The decision they took was momentous: to unilaterally quit the Bretton Woods system, to go off the gold standard, once and for all. It was a transition the United States had to make, Garten argues, and in this sense bears a resemblance to Afghanistan and the present day:

A bridge from the first quarter-century following [World War II] –where the focus was on rebuilding national economies that had been destroyed and on re-establishing a functional world economic system – to a new emvironment where power and responsibility among the allies had to be readjusted . with the burden on the United States being more equitably shared and with the need for multilateral cooperation to replace Washington’s unilateral dictates.

What about Nixon’s re-election campaign in 1972? Of course that had something to do with it; politics always has something to do with policy, Garten says. But one way or another, something had to be done to relieve pressure on the dollar. “The gold just wasn’t there” to continue, writes Garten.

The trouble is, as with all history, that was fifty years ago. What’s going on now?

Read, if you dare, the second half of Michael Bordo’s paper, for a concise summary of the money and banking issues we face. Their unfamiliarity is forbidding; their intricacy is great. The advantages of a digital system may be manifest. “Just as the history of multiple competing currencies led to central bank provision of currency,” Bordo writes, “ the present day rise of cryptocurrencies and stable coins suggests the outcome may also be a process of consolidation towards a central bank digital currency.”

But the choices that central bankers and their constituencies must make are thorny. Wholesale or retail? Tokens or distributed ledger accounts? Lodged in central banks or private institutions? Considerable work is underway, Bordo says, at the Bank of England, Sweden’s Riksbank, the Bank of Canada, the Bank for International Settlements, and the International Monetary Fund, but whatever research the Fed has undertaken, “not much of it has seen the light of day.”

Who best to help shepherd this new world into existence? The choice for the U.S. seems to be between reappointing Fed Chairman Jerome Powell, 68, to a second term, beginning in February, or nominating a Fed governor Lael Brainard, 59, to replace him. President Biden is reeling at the moment. I am no expert, but my hunch is that preferring Brainard to Powell is the better option overall, for both practical and political ends. After all, what infrastructure is more fundamental to a nation’s well-being than its place in the global system of money and banking?

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran.

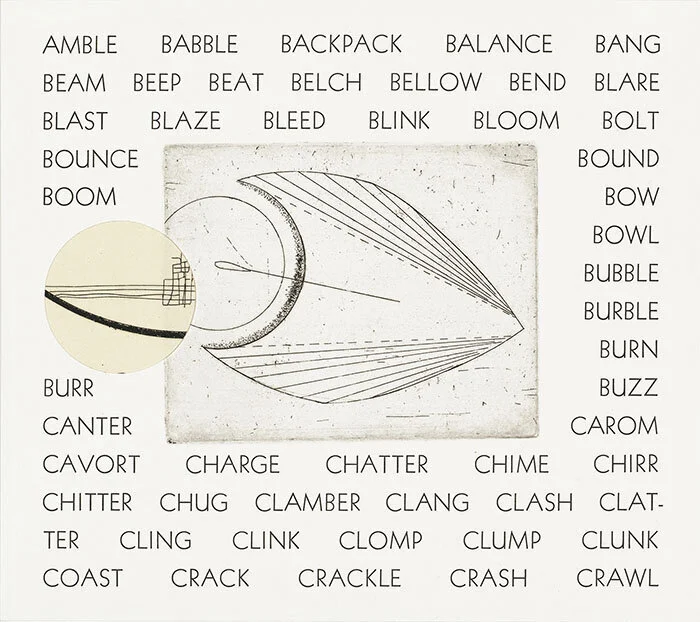

Language structures

“Figures of Speech” ((detail), etching and letterpress), by Somerville, Mass.-based Sarah Hulsey, in her show “Lexical Geometry,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, Sept. 29-Oct. 31.

The gallery says:

“Sarah Hulsey's work portrays the patterns and structures that comprise our universal instinct for language. In this body of work, she uses schematic forms and letterpress text to explore connections across the lexicon.’’

The warm side of the river

“Great Falls’’ in Bellows Falls, Vt. at high flow under the Vilas Bridge, taken from the end of Bridge St on the Vermont side, looking upriver.

“{A} Connecticut River Valley farmer …. was told that his farm was really in New Hampshire, instead of Vermont as he’d always thought. ‘Thank God,’ he said. ‘I didn’t I could stand another one of those Vermont winters.’’’

— Evan Hill (1919-2010) in The Connecticut River (1972)

Chris Powell: Censorship undermines faith in medical science

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Science is wonderful. But it is not always settled. Sometimes the prevailing view in science is wrong, especially in medicine.

For 2,000 years a primary treatment for disease was bloodletting, sometimes administered with leeches. Doctors don't do that anymore.

A sedative called thalidomide was approved for use in European and other countries in the 1960s before it was found to cause birth defects.

The painkiller OxyContin, about which federal litigation is raging because of its highly addictive and even deadly properties, was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 1995. A year later an FDA official involved in OxyContin's approval was hired for a six-figure job at the drug's manufacturer, Stamford-based Purdue Pharma. Now the drug is blamed for thousands of deaths.

Medical mistakes are considered the third leading cause of death in the United States.

This week it was reported that the Food and Drug Administration had given full, formal approval to the Pfizer vaccine for the COVID-19 virus. But the FDA seems just to have extended the vaccine's authorization for emergency use.

Whereupon the acting commissioner of Connecticut's Public Health Department, Dr. Deidre Gifford, urged state residents to "trust the science" and get vaccinated.

It would have been fair to ask the commissioner: Whose science, exactly?

Of course, the commissioner wants people to follow the government's science. But there is other science, though it is increasingly subject to censorship by Internet sites and social media under government pressure.

Yes, quacks and cranks infiltrate discussion of the virus epidemic, as they always have infiltrated medicine. But the discussion also includes many highly credentialed doctors and scientists who -- at least before they voiced objections and concerns -- were renowned and honored in their fields. Some dispute the safety and effectiveness of the vaccines, while others dispute the vaccines' necessity, arguing that effective treatments for the virus are available.

These doctors and scientists could be mistaken. But censorship isn't how contrary assertions should be handled. Contrary assertions should be rebutted and learned from in the open.

This isn't happening because government, its allied medical authorities, and, it seems, journalism don't want a debate that might interfere with their preferred policy, vaccination. They are convinced that they have nothing to learn from the dissenters.

But the public isn't convinced. Many people are indifferent or even opposed to COVID-19 vaccination, and the policy advocated by many in government and the medical establishment is to stop trying to persuade people and start coercing them by denying them the right to live ordinary lives if they don't get vaccinated.

Much indifference and much opposition to vaccination are grounded in ignorance and contrariness. But not all.

Anyone paying attention to developments can perceive fair questions. For example, in regard to the Pfizer vaccine particularly, why is the government pushing it when it is still being tested and side-effects are still being discovered? Is this "approval" really a matter of safety or just political necessity?

And why is Israel's epidemic worsening, with a new wave of virus cases exploding to the level of the country's first wave even though Israel's population now may be the world's most thoroughly vaccinated -- primarily with the Pfizer vaccine?

The more what is said to be science relies on censorship and coercion, the less trust it will deserve.

Taliban religious police beating a woman in Kabul on Aug. 26, 2001.

- Photo by RAWA

If the thousands of Afghans who have swarmed the airport in Kabul for airlift out of the country really think that their country's new Taliban regime will be so terrible, where were they a few weeks ago when the U.S. military began withdrawing from the country?

Why did those thousands not enlist in the Afghan army in defense of the less totalitarian culture the U.S.-assisted government supported?

Those thousands might have formed a few useful military divisions, just as throughout history civilians were mobilized to defend cities under siege. Since women will be oppressed by the Taliban again, where was the Afghan army's 1st Women's Infantry Division? And how will Afghanistan's prospects be improved by removing so many people who oppose theocratic fascism?

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

I'll still be here

Witchgrass

“….I was here first,

before you were here, before

you ever planted a garden.

And I’ll be here when only the sun and the moon

are left, and the sea, and the wide field.

I will constitute the field.’’

—From “Witchgrass,’’ by Louise Gluck (born in 1943), Nobel Prize winning New England poet and writer in residence at Yale

Homogeneous spirit

Above the tree line on the Presidential Range

— Photo by Fredlyfish4

“Though the landscape of New England presents the sharpest of contrasts, from gentle meadow and forest land to the rugged 5,000-foot peaks of the Presidential Range in New Hampshire, there is a kind of homogeneity about the whole that is a matter of spirit rather than of the land itself. If you love New England some inner sense will tell you when you are there.’’

— Stewart Beach (1900-1979) in New England in Color

Chase opens first ‘community center’ in New England

"Rise," a pair of statues installed in 2005, flank Blue Hill Avenue in Mattapan and define it as a gateway to Boston. The statue above is by Fern Cunningham. The one below is by Karen Eutemy.

Jon Chesto, of The Boston Globe, reports:

“Chase has opened the doors to its first ‘Community Center,’ in New England, in Mattapan Square. The retail arm of JPMorgan Chase & Co. is planning these community centers in 16 urban neighborhoods across the country, with 10 such centers opening so far. They provide traditional branch banking services, along with other community services. In the case of the Mattapan branch, Chase regional director Roxann Cooke said Chase has reached out to local nonprofits to help offer financial seminars and workshops at the branch for nearby residents and small-business owners.’’