Memory and geography

“At the Beginning” (cardboard, hand-cut world map), by Vivianne Rombaldi Seppey, in the group show “A Sense of Place,’’ at Heather Gaudio Fine Art, New Canaan, Conn., through Sept. 29. The show features new works by Tegan Brozyna Roberts, Simona Prives and Viviane Rombaldi Seppey.

The gallery says:

“Memory, geography and cultural experiences are underlying themes explored by these three women artists. Through an innovative use of paper, maps, threads, printmaking, collage and projected imagery, the artists in the show create two and three-dimensional objects that express universal notions of belonging and association.’’

Moreno Clock on Elm Street where it meets with South Avenue in New Canaan.

Almost hypnotized by boxwood

Common boxwood

“I have heard New Englanders say that they have an affinity for Box {wood) — that it exerts power like a hereditary memory, and affects them with an almost hypnotic force. This is not felt by everyone, but only by those who have loved Box for centuries, in the persons of their ancestors.’’

— Eleanor Early (1895-1969), in A New England Sampler (1940)

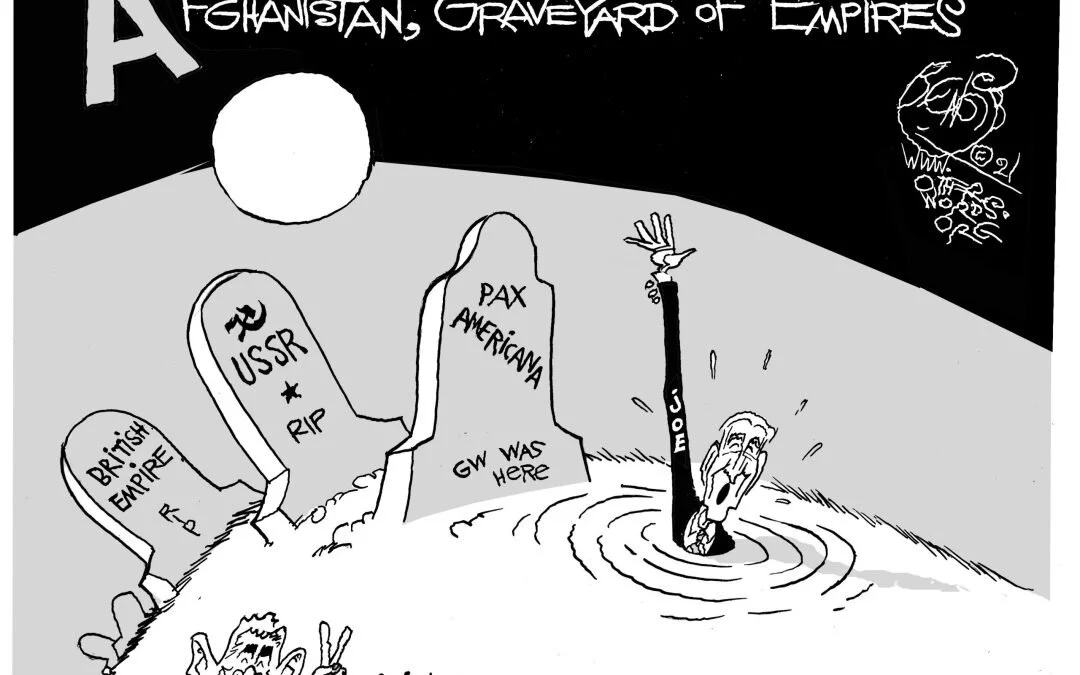

Llewellyn King: Future exports of the Taliban-run Afghanistan will include terrorists, migrants and heroin

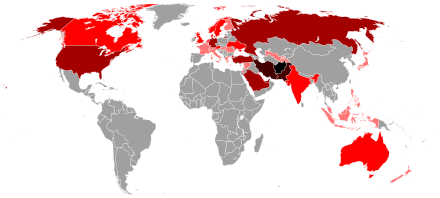

The Afghan diaspora. The darker the color, the more Afghans.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The end of empire is not pretty. Or as Neil Sedaka sang, “Breaking up is hard to do.” The terrible scenes at Kabul’s airport attest to that -- as did those, 46 years earlier, in Saigon.

Technically, the United States has never had an empire nor sought one, but we have sent troops far and wide. Like other empires, bringing them home has been difficult, ugly, and made endless by refugees. Empire, or the American equivalent, follows you home.

The British, the French and the Russians have found the end of empire hard. As did the Romans in their day. Getting out has been a lot harder and uglier than getting in.

When the British withdrew from the Indian Subcontinent, leaving behind a new nation, called Pakistan, and an old one, called India, the blood flowed freely. The sectarian slaughter then was to lead to wars and skirmishes that have lasted to this day. Improbably, Pakistan was two separate entities, East and West Pakistan. Later, East Pakistan split off and became Bangladesh.

When Lord Mountbatten, a stiff-necked British public servant and a royal, set in motion the withdrawal, he ignored plentiful intelligence that there would be strife. An alternative plan called for a slow, measured withdrawal. Mountbatten decided that if it were to be done, it should be done quickly, and the result was more than 1 million died and 15 million to 20 million were displaced, as Muslims fled to Pakistan and Sikhs and Hindus in the opposite direction.

The French withdrew from Algeria and nearly sparked a civil war in France itself. When President Charles de Gaulle announced that France would withdraw from Algeria, there was uncertainty as to which way the French generals would go; reluctantly, they stuck with de Gaulle.

Algeria was truly part of France and the decision to leave was a bitter one. Many French citizens, called Pied-Noirs, like the writer and philosopher Albert Camus, had been born in Algeria, and regarded it as a part of France. But de Gaulle stood firm and civil war was averted -- just.

The worst colonial withdrawal -- it is generally agreed -- was the graceless Belgian exit from the Congo in 1960. Unlike the many former British colonies that inherited a political structure, complete with a parliamentary system based on the one in London, and English Common Law, the Belgians didn’t leave behind a viable political or legal structure for the Congolese.

Simply packing up and coming home is never enough. The French withdrawal from Algeria began an endless immigration stream into France. The British withdrawal from India and the country they created, Pakistan, paved the way for a flood of migrants into the United Kingdom. That isn’t over, as relatives and relatives of relatives claim the right to join family.

Resettled Afghans will bring with them their culture and, more important, their religion. They will leave their mark wherever they are resettled.

The present and future of Afghanistan is made more complex because with the U.S. withdrawal, a religion cloaked in nationalism is the victor. There are many devout Muslim-majority countries, but Afghanistan under the Taliban, will be the most complete. The dominance of religion as the national purpose will be established. The only legal system will be Sharia. And if history is a guide, it will be an extreme and intolerant version that will rule the 39 million people of Afghanistan.

Communism defeated capitalism in Vietnam. But in short order, communism was defeated there, and Vietnam became friendly to the United States, and as passionate about business as Singapore or Hong Kong.

There are no expectations for Afghanistan. A mountainous country of about 38 million people riled by tribalism, it will resume the export of the three things nobody wants: Heroin (opium poppies are a traditional crop), migrants and terrorism.

The debacle that has played out with our national humiliation on television won’t, alas, bring an end. It is, in its own way, a beginning.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Asking New England fishermen to do the right thing

Fishing boats in New Bedford, America’s biggest fishing port

Mario Batali (born 1960)) scandal-rich chef, businessman and writer

Loyally provincial

Juniper Point (once called Butler’s Point), in Woods Hole. The tower room of the house built by Daniel Webster Butler sticks out through the trees at center right.

— Photo by ToddC4176

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I had a great-great grandfather named Daniel Webster Butler (1838-1907) who, after making quite a bit of money as a manufacturer in Boston from about 1860 to 1880, retired to his native Falmouth, Mass., and built a big house (which is still there) in its village of Woods Hole. He filled it with nice stuff. A cousin of my father asked Mr. Butler’s daughter Virginia: “Did Grampa Dan {as he was called in the family} travel all over the Orient to get all these beautiful objects and furnishings?’’

“Heavens no,’’ she answered. “He would never leave Woods Hole.’’

(But he might have enjoyed traveling by the World Wide Web, whose founder, Timothy Berners Lee, was married for a while to a Butler descendant.)

Dan Butler (left) with friend at the Pickwick Club

Dan Butler was also well known in the village for membership in the “exclusive’’ Pickwick Club that as far as can be determined, had no more than three members and met in an old fishing shack.

Steel BBs

How to Lose an Eye

BB guns are not toys. Getting hit by a BB in the eyes can permanently blind you. Consider that as you follow this maddening Providence police story, whose latest iteration can be seen in GoLocalProv.com.

I remember the stupid BB gun fights in the woods of my hometown by 12-year-old boys in the ‘50s. I assume that their parents actually bought them!

Weekend Training

The MBTA is maintaining surprisingly good Providence-Boston weekend train service despite COVID. Use it when you can, say to go to games, shows or plays. I do. Car traffic is intensifying again.

They usually are

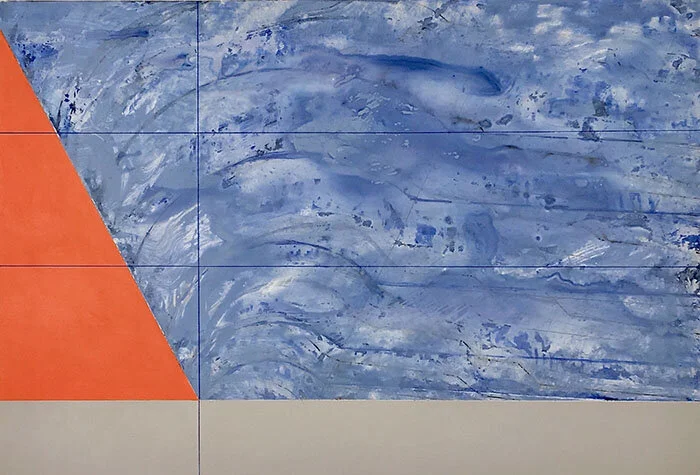

“Disturbed Interactions” (acrylic on canvas), by Pat Paxson, in the group show “The Momentary,’’ at Fountain Street Fine Art, Boston, through Aug. 29.

She tells the gallery (mysteriously…):

"‘Function of time’ for me is: imaginary in terms of temporal possibilities in outer space, related to our uncontrolled release of physical and experimental sounds and images. ‘Time’ for me functions by way of imagination as well as articles in newspapers and results of experimental painting.’’

Looking at 'Water through the lens of climate change'

“Watermark” (acrylic on Yupo), by Greater Boston-based Patty Stone, in her show “Watermark’’, at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, Sept. 1-26. Many of her paintings have been inspired by her close observation of the Charles River.

The gallery says:

“Patty Stone investigates the movement of water through the lens of climate change in a new series of abstract paintings and works on paper. Watermark juxtaposes a fluid paint surface against geometric shapes and lines of measurement suggesting rising tides or changing shorelines.’’

The Charles River at the Medfield-Millis (Mass.) town line

‘Beloved recognition’

Photo by Griffinstorm

Struck, was I, nor yet by Lightning –

Lightning – lets away

Power to perceive His Process

With Vitality –

Maimed – was I – yet not by Venture –

Stone of Stolid Boy –

Nor a Sportsman’s Peradventure –

Who mine Enemy?

Robbed – was I – intact to Bandit –

All my Mansion torn –

Sun – withdrawn to Recognition –

Furthest shining – done –

Yet was not the foe – of any –

Not the smallest Bird

In the nearest Orchard dwelling –

Be of Me – afraid –

Most – I love the Cause that slew Me –

Often as I die

It’s beloved Recognition

Holds a Sun on Me –

Best – at Setting – as is Nature’s –

Neither witnessed Rise

Till the infinite Aurora

In the Other’s Eyes –

— By Emily Dickinson (1830-1886)

Don Pesci: Conn.’s beleaguered moderate Democrats try to push back Progressive schemes

VERNON, Conn.

There is a modest residue of “moderate Democrats” in the Connecticut General Assembly, according to the indispensable Yankee Institute. The moderate Democrat caucus – everyone these days has a caucus – numbers about 28 souls.

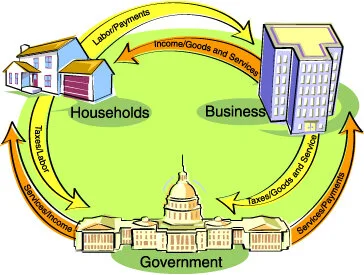

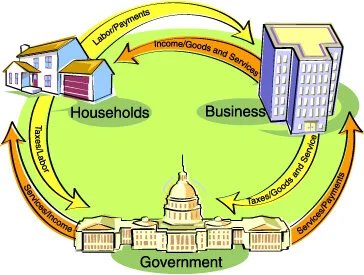

The term “moderate”, particularly as it relates to economics, an art rather than a science, is not merely a meaningless point between extremes.

Until the Democratic Party was dropped into the fiery furnace of Keynesian economics, most Democrats were responsible moderates. Bill Clinton, for example, was the last president, Republican or Democrat, who gave the nation a balanced budget. He was, to be sure, a big spender – and so were all other Keynesians who supposed that deficits were worry-proof because the national debt was “a debt we owed to ourselves.”

This mode of thinking, which demolished spending barriers, has now left us with a national debt currently tipping the scales at $28 trillion and growing, so rapidly has the debt we owe to ourselves metastasized. Actually, the national debt, future generations of Americans will be disappointed to learn, is a charge on the future which, as Yogi Berra once said, “ain’t what it used to be.”

In Connecticut, the residue of moderate Democrats is skittish about ever expanding budgets.

Their beef is displayed in a May media release: ““Moderate House Democrats applaud Governor {Ned} Lamont’s stance on No Tax Increases for the current biennial budget. The State of Connecticut should take advantage of higher than expected consensus revenue, a healthy rainy day fund, and its strong financial position to pass a budget that does not include tax increases.”

Lamont appears to be fighting a rearguard action on tax increases, but he is losing footing on stony ground. The White Knight of progressivism in Connecticut, Martin Looney, a cagy president pro tem of the state Senate, and progressive numbers in the General Assembly, are arrayed against him.

The central and controlling Democratic Party ideological imperative – tax more, spend more, tax more – what some would regard as a vicious cycle for the taxpaying working class in Connecticut, now has a receptive audience in much of the state.

This imperative has for decades leapt over any and every rational proposal to cut spending, long term and permanently, so as to broaden the constricting borders of what has been called "dedicated spending" – that is, automatic spending that needs no biennial budget affirmation by the General Assembly, supposedly in charge of getting and spending in Connecticut.

There are, in other words, two taxing tails and no spending-cut head on the Democrat Party coin, so that whenever it is flipped, the coin always comes up tails, a confidence trickster’s swindle.

When Chris Powell, formerly managing editor of the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, and now a regular political columnist for the paper, was told that some appropriated funding could not be touched in budget negotiations because they were “dedicated funds,” his response was both lucid and revolutionary: Well, undedicate them!

Republicans in the General Assembly, their numbers much reduced, seemed to have settled on at least one campaign platform plank – resolved: there shall be no net increase in taxes – and Lamont appears to be sitting in the same pew. Naturally, appearances in politics, a house of mirrors, are sometimes deceiving.

The fissure between leaders of the progressive movement in the General Assembly, Looney and his counterpart in the House, Speaker Matt Ritter, on the one hand, and Lamont and Democratic moderates on the other hand, appears to be widening. And if legislation were tied to best arguments, Lamont and Democrat moderates would prevail.

Last May, “Democratic legislative leaders announced they were supporting tax proposals passed out of the Finance, Revenue and Bonding Committee that would add a surcharge on capital gains and a second income tax – called a “consumption tax”—on those making over $500,000 per year,” according to Yankee.

And there are more post-Coronavirus, business-crushing tax proposals in the progressive pipeline: “Also included in the proposed taxes is a digital ads tax and making the corporate tax surcharge — which was scheduled to sunset — permanent. Altogether, the tax proposals add up to roughly $1 billion, which Democrat leaders say will be reinvested into Connecticut with a focus on cities and equity.”

These entrepreneurial knee-capping proposals, moderate Democrats feel, are both unnecessary – except perhaps for election purposes – and unwise. “With fiscally sound budgeting practices, the state has positioned itself with an unprecedented $3.5 billion rainy-day fund,” said Rep. Lucy Dathan, D-Norwalk. “Combining this with strong revenue outlook for FY 21 and the incoming ARP funds, we are able to better serve our residents and operate within our current spending cap. Now is not the time to raise taxes.”

However, best ideas and best practices are not always determinative in politics. “Government is force,” said George Washington. Force and numbers often have trumped best ideas, and in the General Assembly, Connecticut’s law-making body, force and numbers lie with Looney, Ritter and hordes of progressives.

Don Pesci is Vernon-based columnist.

Summer into fall

—Photo by fir0002

“The fields pulsate yet with the sound of cricket and cicada…{The} ponds lie there misty, warm, seductive. One day camouflaged as summer, fall can easily toss off this disguise and appear as prophet: cold, wet, angry.’’

— Anne Bernays, in “Fall,’’ in New England: The Four Seasons.

Meteorological summer ends on Aug. 31

Sam Pizzigati: War is wonderful for American military contractors

Raytheon headquarters in Waltham, Mass.

Via OtherWords.org

BOSTON

In the 21st Century, many of us are used to the murderous mass violence of modern warfare.

After all, we grew up living it or hearing about it. The 20th Century rates as the deadliest in human history — 75 million people died in World War II alone. Millions have died since, including a quarter-million during the 20-year U.S. war in Afghanistan.

But for our forebears, the incredible deadliness of modern warfare came as a shock.

The carnage of World War I — with its 40 million dead — left people scrambling to prevent another horror. In 1928, the world’s top nations even signed an agreement renouncing war as an instrument of national policy.

Still, by the mid-1930s the world was swimming in weapons, and people wanted to know why.

In the United States, peace-seekers followed the money to find out. Many of America’s moguls, they learned, were getting rich off prepping for war. These “merchants of death” had a vested interest in the arms races that make wars more likely.

So a campaign was launched to take the profit out of war.

On Capitol Hill, Senate Democrats set up a committee to investigate the munitions industry and named a progressive Republican, North Dakota’s Gerald Nye, to chair it. “War and preparation for war,” Nye noted in 1934, had precious little to do with “national defense.” Instead, war had become “a matter of profit for the few.”

The war in Afghanistan offers but the latest example.

We won’t know for some time the total corporate haul from the Afghan war’s 20 years. But Institute for Policy Studies analysts Brian Wakamo and Sarah Anderson have come up with some initial calculations for three of the top military contractors active in Afghanistan from 2016-2020.

They found that total compensation for the CEOs alone at these three corporate giants — Fluor, Raytheon and Boeing — amounted to $236 million.

A modern-day, high-profile panel on war profiteering might not be a bad idea. Members could start by reviewing the 1936 conclusions of the original committee.

Munitions companies, it found, ignited and exacerbated arms races by constantly striving to “scare nations into a continued frantic expenditure for the latest improvements in devices of warfare.”

“Wars,” the Senate panel summed up, “rarely have one single cause,” but it runs “against the peace of the world for selfishly interested organizations to be left free to goad and frighten nations into military activity.”

Do these conclusions still hold water for us today? Yes — and in fact, today’s military-industrial complex dwarfs that of the early 20th century.

Military spending, Lindsay Koshgarian, of the IPS National Priorities Project, points out, currently “takes up more than half of the discretionary federal budget each year,” and over half that spending goes to military contractors — who use that largesse to lobby for more war spending.

In 2020, executives at the five biggest contractors spent $60 million on lobbying to keep their gravy train going. Over the past two decades, the defense industry has spent $2.5 billion on lobbying and directed another $285 million to political candidates.

How can we upset that business as usual? Reducing the size of the military budget can get us started. Reforming the contracting process will also be essential. And executive pay needs to be right at the heart of that reform. No executives dealing in military matters should have a huge personal stake in ballooning federal spending for war.

One good approach: IIlinois Rep. Jan Schakowsky’s Patriotic Corporations Act.

Among other things, that proposed law would give extra points in contract bidding to firms that pay their top executives no more than 100 times what they pay their most typical workers. Few defense giants come anywhere close to that ratio.

War is complicated, but greed isn’t. Let’s take the profit out of war.

Boston-based Sam Pizzigati co-edits Inequality.org at the Institute for Policy Studies. His latest books include The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win.

'Joy's trick'

“Joy’s trick is to supply

Dry lips with what can cool and slake,

Leaving them dumbstruck also with an ache

Nothing can satisfy.’’

— From “Hamlen Brook,’’ by Richard Wilbur (1921-2017), famed American poet who spent most of his life in New England. Hamlen Brook runs through the Wilbur property in the western Massachusetts “Hill Town” of Cummington.

David Warsh: Reviewing ‘The Decider’s’ disasters

Saddam Hussein being pulled from his hideaway by U.S. troop in Operation Red Dawn, Dec. 13, 2003.

The CIA already had won its war against al-Qaeda before the Bush administration, preparing to invade Iraq, decided to occupy Afghanistan. The result was a second Vietnam War, proceeding from the same combination of good intentions and wicked ignorance as the first.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Three new books stand out against the backdrop of events of this month: First Casualty: The Untold Story of the CIA Mission to Avenge 9/11, by Toby Harnden; The Afghanistan Papers: A Secret History of the War, by Craig Whitlock, of The Washington Post, based on a secret 2015 government study obtained by The Post after a three-year legal battle, and After the Apocalypse: America’s Role in a World Transformed, by Andrew Bacevich.

{Editor’s note: Mr. Bacevich is a professor emeritus of international relations and history at Boston University. He is also a retired U.S. Army colonel. He is a former director of Boston University's Center for International Relations. }

Harnden is a veteran British journalist. He is, I think, substantially correct about the beginnings of the American misadventure in Afghanistan. The CIA knew what it was doing with its minimally invasive horseback strike against al-Qaeda; the rest of the intervention there was a colossal blunder.

To judge from the early reviews, Post reporter Whitlock has done a splendid job of documenting the parallels of institutional reasoning that led, first to the occupation of South Vietnam, and then, decades later, Afghanistan.

Look for both Harnden’s and Whitlock’s books to attract attention. But the publication dates of both books are still a week and a half away., And Bacevich’s summing-up is too far-reaching to consider in the heat of the moment.

So instead I read last week several chapters of To Start a War: How the Bush Administration Took America into Iraq (2020), by Robert Draper, a writer at large for The New York Times Sunday Magazine and National Geographic Magazine. I wanted to be reminded: How did the US get out of the much bigger mess that it made in Iraq with so much less drama?

We know a great deal about how we got into Iraq. Coming long after Rise of the Vulcans: The History of Bush’s War Cabinet (2004), by James Mann, and Bob Woodward’s Plan of Attack: The Definitive Account of the Decision to Invade Iraq (2004); seven years after Peter Baker’s Days of Fire: Bush and Cheney in the White House. (2013); not to mention Draper’s own initial assessment, Dead Certain: The Presidency of George Bush (2007), which had its beginnings in a Texas Observer profile that helped launch then-Governor Bush’s presidential bid

Draper’s book is probably the last word on the decision-making that led to the war. He finds, even more persuasively than his predecessors, that there was “no ‘process’ of any kind” in making the decision to go to war, or in the thinking-through of what might happen once war had begun. The self-proclaimed “Decider” simply made up his mind, and improvised thereafter. No Iraqi connection to 9/11 has subsequently been discovered. No “weapons of mass destruction” were found. Hopes rode initially on killing Saddam and his sons on the first night of the invasion with a stealth-bomber raid that turned out to have been based on faulty intelligence. After the bombs dropped a few hours too late, chaos ensued.

Draper attaches a good deal of importance to Bush’s thinking with respect to Saddam’s presumed attempt to assassinate his father with a car bomb when the former president visited Kuwait in 1993, two years after the first war with Iraq. I was disappointed by Draper’s chapter on the role of the press in supporting the war, “Truth and the Tellers.” Both The Times and The Wall Street Journal aggressively backed the Bush administration’s charges and plans. But he realistically hints at the in-house pressures, quoting national- security specialist James Risen, who was then working for The Times: “It’s like any corporate culture, where you know what management wants, and no one has to tell you.” I looked back at what I written, both at the time and a year later, and winced.

But it was Draper’s last chapter, “The Day After,” that riveted my attention. In January, 2007, Bush announced a “surge” – 20,000 additional troops to join the 150,000 or so already in Iraq. The next year was the deadliest for U.S. forces since 2004, but the level of violence gradually dropped and the additional troops were withdrawn. The last combat troops left Iraq in 2010. Some 4,400 American soldiers were killed in Iraq; 32,000 were wounded. Of the 1.5 million who served there, 300,000 returned home suffering from post-traumatic stress disorders. But Draper notes:

The toll was heaviest for the liberated. An estimated 405,000 Iraqis would die as a result of the 2003 invasion. Instead of Saddam, Iraq now had other forces of Sunni brutality. First there was Zarqawi, the leader of al-Qaeda in Iraq; and later would come the Islamic State, commonly known as ISIS. Though participatory democracy had more or less taken root, the dominant motif in Iraq was not freedom, as Bush had hoped, but rather violence, instability, and unending recrimination.

What replaced preoccupation with Iraq? The Financial Crisis of 2008, of course.

The conventional story is that President Obama inherited the disaster and somehow saved the day by obtaining the passage of a 2009 stimulus measure. In fact, it was Federal Reserve Board Chairman Ben Bernanke and Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson, who led central bankers around the world in devising an effective lending response to the global panic. Both were Bush appointments in his second term, and it was Bush himself who took the lead in announcing Emergency Economic Stabilization measures of 2008.

The pell-mell retreat from Afghanistan and slow-motion disaster in Iraq are blows to American prestige comparable to the fall of Saigon, in 1975, the overthrow of the Shah of Iran, in 1979, and the Cuban Revolution, in1959. But they were not the End-of-Times battles of evil and good envisaged in Revelation, the last book of the Bible, from which we inherited the word “Apocalypse.” Something like an Apocalypse threatened in 2008. Thanks to American leadership and global teamwork, a Second Great Depression didn’t occur. We are still a long way from understanding the history of the last 50 years.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

Mass. medical schools join to fight racism in health care

Headquarters, in Waltham, of the Massachusetts Medical Society (MMS), the oldest continuously operating state medical association in the United States. Incorporated on Nov. 1, 1781, by an act of the Massachusetts General Court, the MMS is a non-profit organization with more than 25,000 physicians and medical students as members. Its New England Journal of Medicine is among the most prestigious and influential such publications in the world.

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

BOSTON

“The University of Massachusetts Medical School, in Worcester, and the Massachusetts Medical Society are joining other medical schools in the state to combat racism in the health-care industry and medicine. The schools released a set of principles targeting racism in medical schools and other health-care organizations.

The schools, including the Boston-based Harvard Medical School, Boston University Medical School and Tufts University Medical School, also in Boston, outlined their long-term goals in a set of four principles. The first principle relates to the need to acknowledge and learn, including from a historical standpoint, as racism in medical practice has had a longstanding presence. The second point calls on institutional leaders to visibly commit to dismantling racism, and the third call for confronting practices and policies devaluing staff and patients of color. The last of the four principles emphasizes a culture of empathy and recognition of the intersectionality of oppression.

“‘It is mission critical for the Medical Society, the DPH (Massachusetts Department of Public Health) and our state’s medical schools to lead in supporting the next generation of physicians and their patients,’ said the Medical Society’s president, Dr. Carole Allen. ‘This document outlines important steps to address systemic racism as it manifests in health care.”’

'Dip one's toes in'

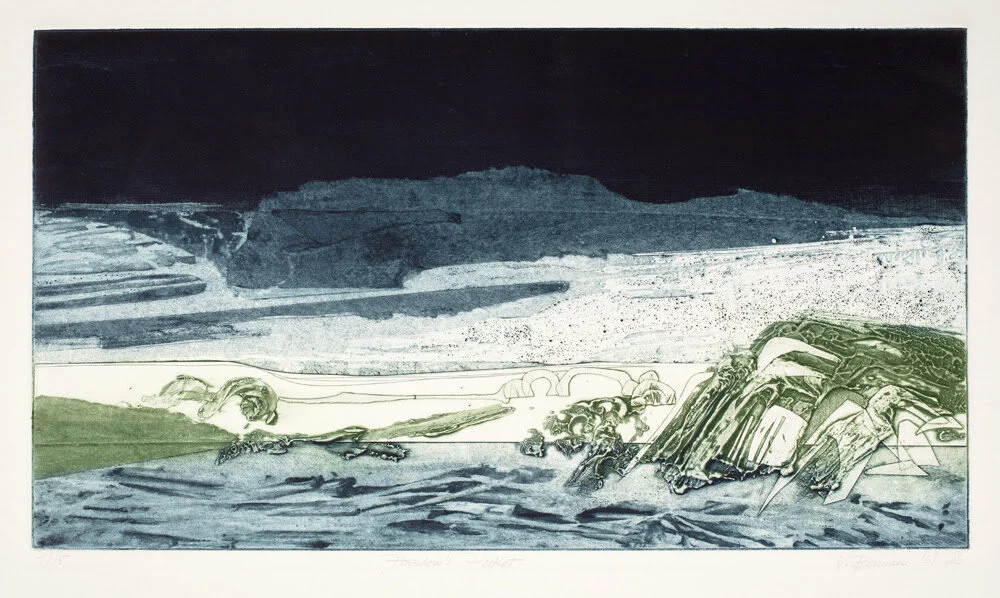

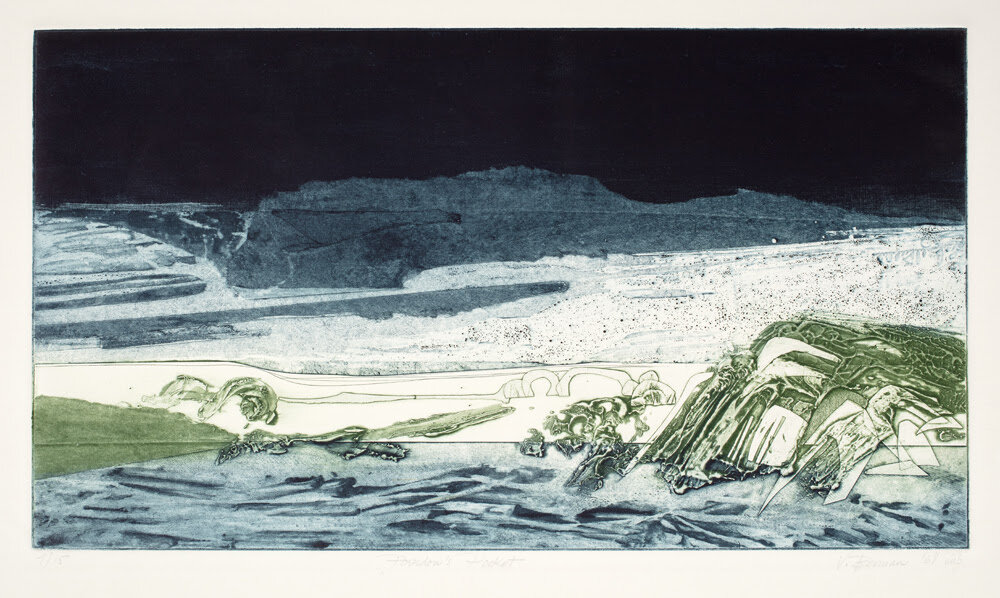

“Poseidon’s Pocket” (collagraph), by Massachusetts artist Vivian Berman (1928-2016), at the Art Complex Museum, Duxbury, Mass.

The museum says:

“Berman used silk scraps, aluminum foil, and matte acrylic medium to create a variety of textures within the single image. The print conveys such an authentic impression of the sea, one is tempted to dip one’s toes in! The artist’s abstract renderings of the sea, sky, and landscape often conveyed a sense of solitude.

…. Berman was among a small group of artists who studied with Donald Stoltenberg (1927-2016), a printmaker who explored collagraph methods in the late 1960s. These artists advanced the medium and helped it to gain recognition as a fine-art form.’’

The Art Complex Museum

Powder Point Bridge, in very sandy Duxbury

— Photo by John Phelan -

‘In chilly solitude’

Illustration from Everard Digby's “The Art of Swimming (De Arte Natandi)” (1587).

“Into my empty head there come

a cotton beach, a dock wherefrom

I set out, oily and nude

through mist, in chilly solitude’’

— From “Morning Swim,’’ by Maxine Kumin (1925-2014), U.S. poet laureate in 1981-1982. She lived in Warner, N.H.

— Photo by Richard Palmer

Chris Powell: Day of deliverance from tribalism is coming

Census outreach flyers hang at Sure We Can - redemption center in Brooklyn last year.

— Photo by Wil540

MANCHESTER, Conn.

How strange that Connecticut and the country are being condemned as "structurally" and "systemically" racist even as the latest U.S. Census finds that they are more multiracial and multiethnic than ever and demographers expect that the country soon will have a nonwhite majority.

These trends do not suggest oppression. Rather they suggest acceptance and equality. They provide hope that within the lifetimes of today's young people the current obsessions with race and ethnicity will seem quaint and people will see each other first as people -- and maybe as Americans too.

Lincoln foresaw that day, as did the country's founders, the proclaimers of the Declaration of Independence.

In Chicago campaigning for the Senate shortly after Independence Day in 1858, Lincoln noted that half the people in the country then were not descendants of those who had fought the Revolution but instead were recent immigrants.

"If they look back through this history to trace their connection with those days by blood," Lincoln said, "they find they have none. They cannot carry themselves back into that glorious epoch and make themselves feel that they are part of us.

"But when they look through that old Declaration of Independence they find that those old men say that 'we hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,' and then they feel that that moral sentiment taught in that day evidences their relation to those men, that it is the father of all moral principle in them, and that they have a right to claim it as though they were blood of the blood and flesh of the flesh of the men who wrote that Declaration -- and so they are."

The day of deliverance from tribalism has been a long time coming and it is not here yet, but the U.S. Census shows that it is coming.

Racial and ethnic composition aren't the important things about this country. What is important is the commitment to a democratic and secular culture and to the objective of raising everyone to economic self-sufficiency, reducing the extremes of wealth and poverty so that everyone has a vital stake in that democratic and secular culture.

The census suggests that race and ethnicity will be taking care of themselves, that the country may be more integrated in those respects than some think it is. Economic inequality has become the bigger challenge.

xxx

Not that the United States ever should have cared much about Afghanistan, but how was that country to resist a return of the theocratic fascism of the Taliban when the United States planned to evacuate so many Afghans who didn't want to live under theocratic fascism and most Afghans didn't care much about how they would be governed?

The rationale offered for this evacuation was that these Afghans were helping the United States. To the contrary, the United States was helping them build a country without theocratic fascism.

That effort, costing thousands of American lives and trillions of dollars, failed mainly because most Afghans themselves are indifferent to how they are governed. As soon as the U.S. and NATO troops began to withdraw from the country, Afghan soldiers deserted or surrendered and Afghans who desire freedom failed to mobilize.

If the Afghans themselves cared so little about their freedom, why should the United States have cared more?

The Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the United States were not the consequence of the sanctuary that Afghanistan provided to some of the terrorists. They were the consequence of the failure of the United States to enforce its own immigration law, to pursue intelligence that a spectacular attack was being planned, and to maintain security in air travel.

Who rules in Afghanistan now will be far more a problem for Russia, China, Pakistan, and Iran than for the United States.

But the United States still fails to enforce immigration law. Even as the federal government and state governments are busy devising social controls in the name of reducing the spread of the COVID-19 virus, the country's southern border is wide open, with the Biden administration admitting thousands of immigration lawbreakers even when they are known to be infected.

The United States can let the Taliban have Afghanistan, but one of these days it should control its own borders.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.

Folksy?

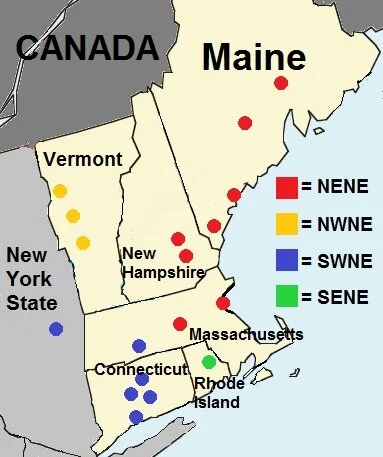

Northeastern (NENE), Northwestern (NWNE), Southwestern (SWNE), and Southeastern (SENE) New England English represented here, as mapped by the Atlas of North American English on the basis of data from important cites and towns.

— Graphic by Wolfdog

“There are areas of New England, plenty of them, with quaintness to spare, with color-changing leaves and folksy folks full of folksy homespun wisdom accompanied by folksy accents.”

— A Lee. Martinez (born 1973), Texas-based fantasy and science fiction author.