Who was he?

The Somerset Club on Beacon Street, Boston, long a social center for Boston Brahmins.

“It used to be said that, socially speaking, Philadelphia asked who a person is, New York how much is he worth, and Boston what does he know. Nationally it has now become generally recognized that Boston Society has long cared even more than Philadelphia about the first point and has refined the asking of who a person is to the point of demanding to know who he was. Philadelphia asks about a man's parents; Boston wants to know about his grandparents.’’

Cleveland Amory (1917-1998), in his book The Proper Bostonians (1947). Amory was a reporter, editor, social historian, essayist, TV critic and animal-rights crusader. He came from a Boston Brahmin family.

Thomas A. Barnico: Should Feds dictate rules on campus sexual misconduct? Beware

“My Eyes Clear Away Clouds” (collage), by Timothy Harney, a professor at the Montserrat College of Art, in Beverly, Mass.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

The U.S. Department of Education is poised to reverse Trump-era rules governing claims of sexual misconduct on campus. One could forgive weary college counsel for a case of vertigo: The Trump rules themselves reversed the Obama rules, and Biden’s 2021 nominee to enforce the rules—Catherine Lhamon—held the same office at the Education Department under Obama. In three years, the election of 2024 may bring yet another volte-face at the department. Even those who support the likely Biden changes may wonder: Is this any way to run a government?

As they ponder that question, frustrated counsel should note the primary source of the problem: the desire by serial federal officials to dictate hotly contested standards of student conduct for millions of students in thousands of colleges in a nation of 330 million people.

Some issues are better left to the provincials. As Duke Law professors Margaret Lemos and Ernest Young argue: “Federalism can mitigate the effects of [national] political polarization by offering alternative policymaking venues in which the hope of consensus politics is more plausible.” Delegation to state or local governments or, in education, to private actors, can “operate as an important safety valve in polarized times, lowering the temperature on contentious national policy debates.”

Of course, as Lemos and Young admit, “a federalism-based modus vivendi is unlikely to satisfy devoted partisans on one side or another of any divisive issue.” Such conflicts pit competing and compelling interests against one another.

In the Title IX context, parties fiercely debate the adequacy of protections for complainants and respondents alike: Does the respondent have a right to confront and cross-examine the complainant? Does the respondent have a right to counsel in their meeting with student affairs personnel? Do colleges and universities have to abide by a common definition of “consent” to intimacy in their student conduct manuals?

And, in polarized times, many will be unsatisfied with a patchwork of rules that apply state-by-state or college-by-college. Lost in this good-faith debate is the point that, even for issues with national effects, an oscillating national rule can cause more instability than an entrenched array of differing local rules.

Noted diplomat and scholar George F. Kennan aptly described the problem in Round the Cragged Hill: “The greater a country is, and the more it attempts to solve great social problems from the center by sweeping legislative and judicial norms, the greater the number of inevitable harshnesses and injustices, and the less the intimacy between the rulers and ruled. … The tendency, in great countries, is to take recourse to sweeping solutions, applying across the board to all elements of the population.” Central dictates, Kennan said, often show “diminished sensitivity of … laws and regulations to the particular needs, traditional, ethnic, cultural, linguistic and the like, of individual localities and communities.”

Of course, changes in administrations often bring changes in policy. Elections matter, and victors arrive with fresh ideas and an appetite for change. This is a highly democratic impulse; as U.S. Chief Justice William Rehnquist wrote: “A change in administration brought about by the people casting their votes is a perfectly reasonable basis for an executive agency’s reappraisal of the costs and benefits of it programs and regulations.”

Sometimes, such reappraisals will follow a reversal in the public current of the times. Where the new current runs strong and fast—and newly elected officials carry a decisive electoral mandate—a sweeping national solution may reflect a consensus view. But when electoral margins are slim, dangers lurk. When national executive and legislative power repeatedly changes hands by slim margins, policy changes may reflect not strong new currents but more of a series of quick, jolting bends.

The shifting procedural rights of the complainants and respondents in the Title IX misconduct hearings more resemble the latter. The abruptness of such changes grows when the commands flow not from a congressional act but by “executive order,” administrative “guidance,” or “Dear Colleague” letters that lack the procedural protections of a statute passed by both houses of Congress. Moreover, too-frequent changes in rules—whatever their procedural sources—have long been seen to create uncertainty, undermine compliance and lessen respect for law.

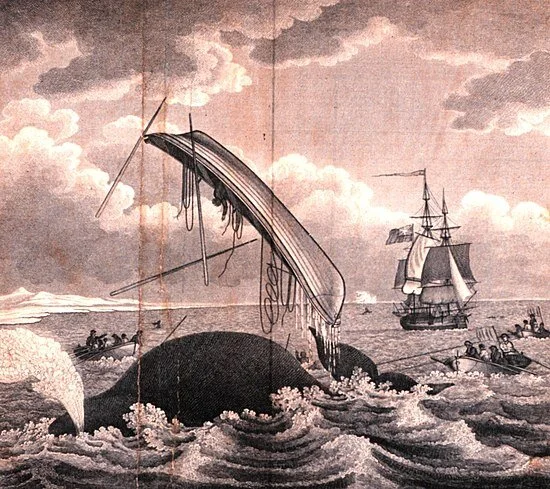

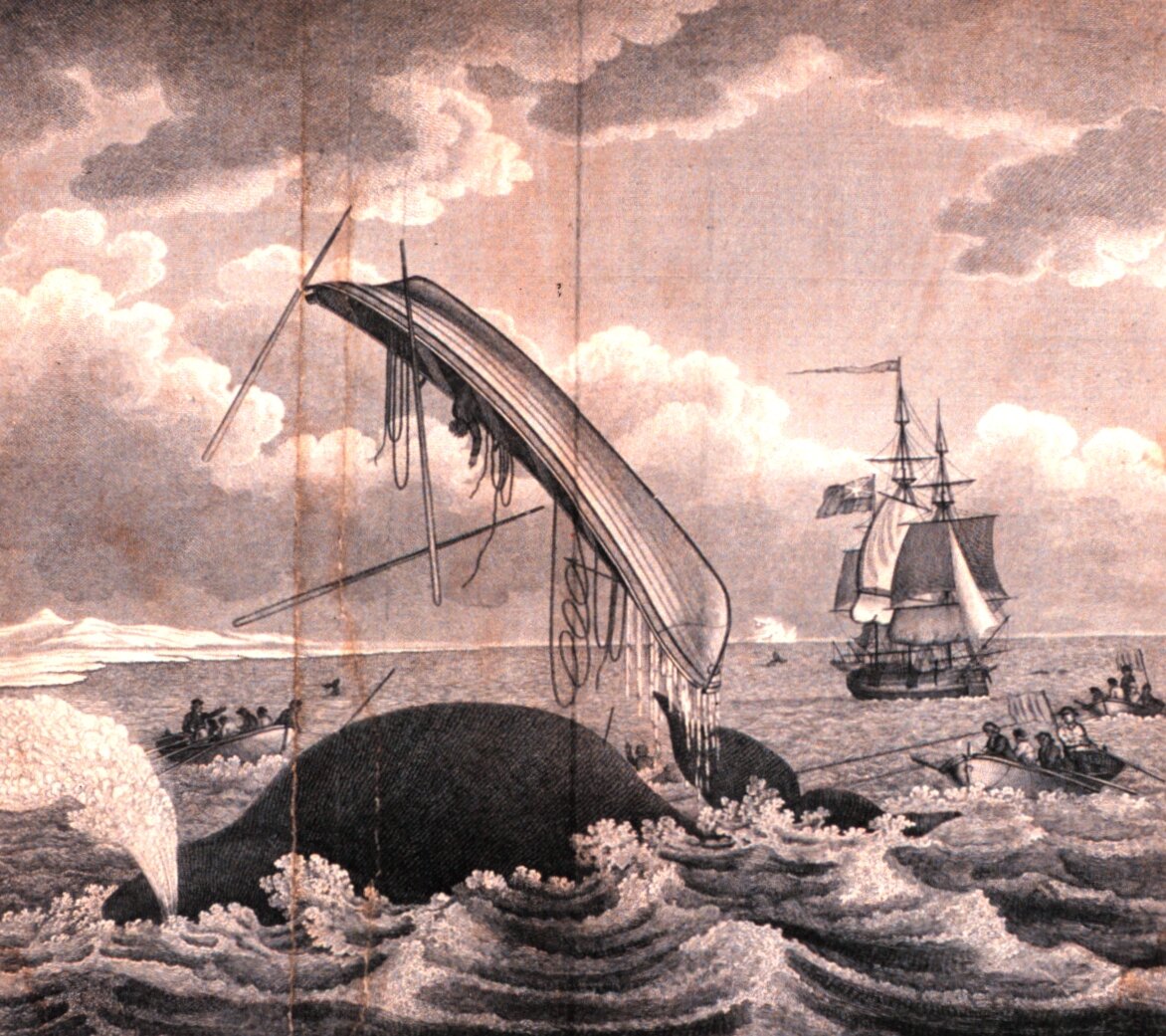

The options for beleaguered college counsel are few. Education Department rules apply to colleges because colleges desire federal funds. Few colleges wish to turn off the spout of the federal Leviathan. The masters they acquire are both the sovereign Leviathan of Hobbes and the whale dreamed by Herman Melville in Moby-Dick: a giant of the deep that pulls colleges to and fro, as if dragging them in a whaleboat on a “Nantucket Sleigh Ride.”

In our modern form of the tale, the whaleboat is the college, and the harpoon is its application for federal funding. The harpoon hits its rich federal target, but the prize brings conditions, represented by the attached rope. “Hemp only can kill me,” Ahab prophesizes. “The harpoon was darted; the stricken whale flew forward; with igniting velocity the line ran through the groove;—ran foul.” The rope—initially coiled neatly in a corner of the whaleboat—runs out smoothly until spent. Then it tangles, converting itself to a weapon more deadly than the harpoon. Bound by the rope—the conditions on federal funding—the college descends into the vortex.

Biden’s likely Title IX rules on student misconduct will pull college administrators to and fro again, whalers on a new, hard ride. The day that the federal government withdraws from the field seems distant; like Ahab, Education Department officials of both parties seem “on rails.” In the meantime, college counsel should brace for the latest chase and hope that they—like Ishmael—will live to tell the tale.

Thomas A. Barnico teaches at Boston College Law School. He is a former Massachusetts assistant attorney general (1981-2010).

“Nantucket Sleigh Ride”: Illustration of the dangers of the "whale fishery" in 1820. Note the taut ropes on the right, lines leading from the open boats to the harpooned animal.

Grace Kelly: Trying to protect the precious ecosystems/buffers that are salt marshes

The Jacob’s Point Preserve at the border of Bristol and Warren is one of Rhode Island’s healthier salt marshes.

— Photo by Joanna Detz/ecoRI News

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

“To stand at the edge of the sea, to sense the ebb and flow of the tides, to feel the breath of a mist moving over a great salt marsh, to watch the flight of shore birds that have swept up and down the surf lines of the continents for untold thousands of years, to see the running of the old eels and the young shad to the sea, is to have knowledge of things that are as nearly eternal as any earthly life can be.” — Rachel Carson

Rhode Island’s salt marshes are magical places. They are where land meets sea, liminal areas where you can hear both the chirping of crickets and the caw of seagulls. Oysters and mussels sit warm in the brackish mud.

The Jacob’s Point Preserve on the Bristol-Warren line is one of these special places. It is the flagship property of the Warren Land Conservation Trust.

It was a breezy but warm fall morning and Scott Ruhren, senior director of conservation for the Audubon Society of Rhode Island, walked along the boardwalk that leads toward the 37.6-acre marsh, which sits between the East Bay Bike Path and the Warren River.

As we walked, he pointed out various native and invasive plants, the skeletons of tupelo trees that remain after a 10-mile brushfire ripped through the marsh in 2008, and an old farming path that tramples through the rushing phragmites.

When we meandered into the coastal flatlands of the marsh, Ruhren stepped off the path and headed over to a patch of rusty-red sea pickle. “This is edible,” he said, picking a few ends of the succulent plant. “It has a salty flavor, and turns this beautiful red in the fall.”

Seaside goldenrod bends in the ocean breeze, and Ruhren spotted what he thought could be the elusive and endangered saltmarsh sparrow flitting through cordgrass.

“This is one of the spots they’re doing incredibly well,” he said. “But if the salt marshes go away and sea level rises faster, it could disappear. It’s a sad story.”

But the saltmarsh sparrow isn’t the only species in danger if sea levels continue their accelerated rise. You see, salt marshes are more than just diverse brackish ecosystems. They are more than stinky, slimy, mucky patches of water-land. They are also natural buffers that protect land from sea. They’re priceless.

“From a sea-level rise standpoint, they absorb tons of energy,” Ruhren said. “We have a couple coastal refugees around the state and after big storms like Sandy or Irene, people always think the salt marshes are going to be wiped out, but the natural salt marshes survive those events better than human landscapes. For example, when Misquamicut was wiped out, a lot of the buildings were gone, but the marsh itself absorbed the impact. So, it’s like the first line of defense for the inland habitats.”

But this defense is at risk. As sea levels rise and as human development hardens the land along the coast, salt marshes are running out of room to adapt. They are on a path toward functional extinction. As they drown, the vital services they provide — habitat, storm buffering and carbon sequestration — will also disappear.

In fact, the loss of coastal wetlands is one of the biggest causes of permanent landscape alteration in the United States. Rhode Island, for example, has already lost more than 50 percent of its original salt marsh habitats during the past two centuries because of human activities.

“We’re dealing with two things with salt marshes in Rhode Island,” Ruhren said. “It’s all the manmade issues and disturbances, and then the lack of sediment building up in the marsh like it normally would, which is compounded by more frequent storms and sea-level rise.”

Salt marshes are getting squeezed out, with sea water encroaching on one side and humans on the other. And Jacob’s Point, while a relatively healthy example of a salt marsh, has a history of human-induced degradation.

“The path that the Warren Land Trust uses to get out to the water was actually built by a landowner who lived up hill, and he used to bring a seaplane in and bring in supplies that way,” Ruhren said. “That path led to a lot of the problems on the marsh because there were stone culverts — probably early 20th Century — and one by one the stone culverts started to collapse … and created an impoundment on the south side of the marsh. And what you want in a salt marsh is that twice day flushing of the salt water. If you don’t get that, you start to get the degradation.”

Development in and around salt marshes impairs their ability to naturally move when waters rise.

Another sign of human meddling that could have impacts in the future is the sprawling private neighborhood development up the hill from the salt marsh. Also called Jacob’s Point, it’s an example of the hardening of the shoreline, an area once wild being taken over by cookie-cutter houses with manicured, chemical-green lawns.

It’s quite the contrast to the wild, unkempt scraggle of the salt marsh below.

“I always like to use Connecticut as an analogy,” Ruhren said. “When you drive up [Interstate] 95, they pretty much have a hardened shoreline all the way up. We’re trying to avoid that.”

To combat the further loss of these important coastal ecosystems, various state agencies have worked together to assess and save salt marshes. In 2016, the Coastal Resources Management Council (CRMC) released a Rhode Island Salt Marsh Monitoring and Assessment Program (SMMAP) that “presents a strategy for developing a comprehensive, statewide monitoring and assessment program.”

In essence, SMMAP is triage for salt marshes.

“A lot of the salt marshes have been assessed to try to determine which ones are worth saving,” Ruhren said. “Because one that is so horribly degraded, well, it doesn’t pay to work on it.”

Besides building modern culverts and enhancing marsh elevation with dredge materials, the best way humans can reverse the wrong we have wrought on salt marshes — and in the process help our species survive — is simple: preserve land.

“Ideally the best thing to do is to save land, and land right from the marsh, which is not always possible because it’s such a built-up shoreline,” Ruhren said. “That allows for salt marsh migration, because salt marshes naturally move, and with sea-level rise, if they don’t have a place to move inland, they’re just going to be squashed and shrink and shrink more.”

Editor’s note: Grace Kelly was a ecoRI News staffer when she filed this story.

Shrivel season

American elm tree known as "Ed Cotton's elm," at the corner of Old South Street and Conz Street in Northampton, Mass. This tree dates back to the late 1800s.

— Photo by Msact

“The elm leaves shrivel on the twig

and the sun beats through and our time is big….

—From “The Long Hot Summer,’’ by Archibald MacLeish (1892-1982) poet, playwright, lawyer and government official. He spent his final decades in Conway, Mass.

Dynamic wooden shapes

“Plaid Flannel” (carved polychromed sugar maple), by Vermont artist Clark Derbes, in his show “Time Travelers and Portals,’’ at the Hall Art Foundation, Reading, Vt., Aug. 28-Nov. 28.

The show’s organizers say: “Derbes first cuts blocks of wood from a variety of tree species, including elm, poplar and maple. Continuing to carve each block into a unique and dynamic shape, he meticulously chisels, paints, sands and burnishes each piece in order to achieve a variety of complex geometric visual systems, planes, patterns and patinas.”

The much-photographed Jenne Farm, in Reading

Reading Town Hall and post office.

Susan Jaffe: Designating 'essential support' people for nursing-home residents

From Kaiser Health News (kaiserhealthnews.org)

After COVID-19 hit Martha Leland’s nursing home — Sheridan Woods Health Care Center, in Bristol — it logged 28 fatalities; last year, she and dozens of other residents contracted the disease while the facility was on lockdown.

“The impact of not having friends and family come in and see us for a year was totally devastating,” she said. “And then, the staff all bound up with the masks and the shields on, that too was very difficult to accept.” She summed up the experience in one word: “scary.”

But under a law that Connecticut enacted in June, nursing-home residents will be able to designate an “essential support person” who can help take care of a loved one even during a public health emergency. Connecticut legislators also approved laws this year giving nursing-home residents free internet access and digital devices for virtual visits and allowing video cameras in their rooms so family or friends can monitor their care.

Similar benefits are not required by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the federal agency that oversees nursing homes and pays for most of the care they provide. But states can impose additional requirements when federal rules are insufficient or don’t exist.

And that’s exactly what many are doing, spurred by the virus that hit the frail elderly hardest. During the first 12 months of the pandemic, at least 34 percent of those killed by the virus were residents of nursing homes and other long-term care facilities, even though they make up fewer than 1 percent of the American population. The vaccine has since reduced virus-related nursing-home deaths to about 1 in 4 covid-related fatalities in the United States, which have risen to more than 624,000, according to The New York Times’s case tracker.

“Part of what the pandemic did is to expose some of the underlying problems in nursing homes,” said Nina Kohn, a professor at Syracuse University School of Law and a distinguished scholar in elder law at Yale Law School. “This may present an opportunity to correct some of the long-standing problems and reduce some of the key risk factors for neglect and mistreatment.”

According to a review of state legislation, 23 geographically and politically diverse states have passed more than 70 pandemic-related provisions affecting nursing home operations. States have set minimum staffing levels for nursing homes, expanded visitation, mandated access for residents to virtual communications, required full-time nurses at all times and infection control specialists, limited owners’ profits, increased room size, restricted room occupancy to two people and improved emergency response plans.

The states’ patchwork of protection for nursing home residents is built into the nation’s nursing home care regulatory system, said a CMS spokesperson. “CMS sets the minimum requirements that providers need to meet to participate with the Medicare/Medicaid programs,” he said. “States may implement additional requirements to address specific needs in their state — which is a long-standing practice — as long as their requirements go above and beyond, and don’t conflict with, federal requirements.”

Julie Mayberry, an Arkansas state representative, remembers a nursing home resident in her district who stopped dialysis last summer, she said, and just “gave up” because he couldn’t live “in such an isolated world.”

“I don’t think anybody would have ever dreamed that we would be telling people that they can’t have someone come in to check on them,” said Mayberry, a Republican and the lead sponsor of the “No Patient Left Alone Act,” an Arkansas law ensuring that residents have an advocate at their bedside. “This is not someone that’s just coming in to say hello or bring a get-well card,” she said.

When the pandemic hit, CMS initially banned visitors to nursing homes but allowed the facilities to permit visits during the lockdown for “compassionate care,” initially if a family member was dying and later for other emergency situations. Those rules were often misunderstood, Mayberry said.

“I was told by a lot of nursing homes that they were really scared to allow any visitor in there because they feared the state of Arkansas coming down on them, and fining them for a violation” of the federal directive, she said.

Jacqueline Collins, a Democrat who represents sections of Chicago in the Illinois Senate, was also concerned about the effects of social isolation on nursing home residents. “The pandemic exacerbated the matter, and served to expose that vulnerability among our long-term care facilities,” said Collins, who proposed legislation to make virtual visits a permanent part of nursing home life by creating a lending library of tablets and other devices residents can borrow. Gov. J.B. Pritzker is expected to sign the measure.

To reduce the cost of the equipment, the Illinois Department of Public Health will provide grants from funds the state receives when nursing homes settle health and safety violations. Last year, Connecticut’s governor tapped the same fund in his state to buy 800 iPads for nursing home residents.

Another issue states are tackling is staffing levels. An investigation by the New York attorney general found that covid-related death rates from March to August 2020 were lower in nursing homes with higher staffing levels. Studies over the past two decades support the link between the quality of care and staffing levels, said Martha Deaver, president of Arkansas Advocates for Nursing Home Residents. “When you cut staff, you cut care,” she said.

But under a 1987 federal law, CMS requires facilities only to “have sufficient nursing staff to attain or maintain the highest practicable … well-being of each resident.” Over the years, states began to tighten up that vague standard by setting their own staffing rules.

The pandemic accelerated the pace and created “a moment for us to call attention to state legislators and demand change,” said Milly Silva, executive vice president of 1199SEIU, the union that represents 45,000 nursing home workers in New York and New Jersey.

This year states increasingly have established either a minimum number of hours of daily direct care for each resident, or a ratio of nursing staff to residents. For every eight residents, New Jersey nursing homes must now have at least one certified nursing aide during the day, with other minimums during afternoon and night work shifts. Rhode Island’s new law requires nursing homes to provide a minimum of 3.58 hours of daily care per resident, and at least one registered nurse must be on duty 24 hours a day every day. Next door in Connecticut, nursing homes must now provide at least three hours of daily direct care per resident next year, one full-time infection control specialist and one full-time social worker for every 60 residents.

To ensure that facilities are not squeezing excessive profits from the government payment they receive to care for residents, New Jersey lawmakers approved a requirement that nursing homes spend at least 90 percent of their revenue on direct care. New York facilities must spend 70 percent, including 40 percent to pay direct-care workers. In Massachusetts, the governor issued regulations that mandate nursing homes devote at least 75 percent on direct-care staffing costs and cannot have more than two people living in one room, among other requirements.

Despite the efforts to improve protections for nursing home residents, the hodgepodge of uneven state rules is “a poor substitute for comprehensive federal rules if they were rigorously enforced,” said Richard Mollot, executive director of the Long Term Care Community Coalition, an advocacy group. “The piecemeal approach leads to and exacerbates existing health care disparities,” he said. “And that puts people — no matter what their wealth, or their race or their gender — at an even greater risk of poor care and inhumane treatment.”

Susan Jaffe is a reporter at Kaiser Health News.

Jaffe.KHN@gmail.com, @SusanJaffe

'The very heart'

“View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm—The Oxbow {of the Connecticut River},’’ by Thomas Cole, in 1836

“They came singly and in groups, in small companies and in larger bands; and rapidly homes and farms doted the valley, villages were built, and in an amazingly short time the wilderness had been conquered and tamed and the Connecticut Valley became the garden spot, the very heart of all New England.’’

— A. Hyatt Verrill (1871-1954) inventor, writer, editor and zoologist, in The Heart of Old New England

Llewellyn King: A life in journalism: fascination and panic

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

A young man asked me for advice on a career in journalism. The following is the letter I sent to him.

For advice about a career in journalism, I may not be the person to ask

I dropped out of school at 16 because I wanted to be a journalist. I wanted to know the great figures of my time and to travel the world. Journalism has not let me down.

To me, newspapering is almost a sacred calling. You can air injustice and celebrate genius. It is true, personal freedom: You always, at heart, work for yourself within a framework of your employment. You can talk to anyone in any office in any country and expect to be allowed an audience.

In the end, it is between you and the reader. We need income to practice our trade, but our communic is always between the writer and the reader.

The commodity is news. It is news in the humblest local paper or The Washington Post. Jack Cushman, who worked for me as the editor of Defense Week, and who became a star at The New York Times, told me once, "You used to tell me when I was writing a story, 'Come on, Cushman, you won't write it better in The New York Times.' You know what? I don't."

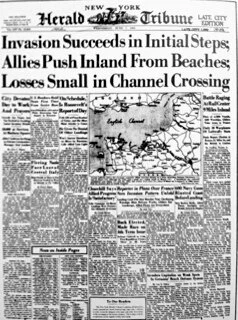

The message is: Be defined by what you write, not for whom you write it. But, of course, we all want to succeed and the measure of success can be where we work; that, I grant, and I have been a pursuer of good jobs everywhere, having worked for Time and Life as a very young stringer in Africa, the Daily Mirror and the BBC in London, The Herald Tribune in New York, and The Washington Post in Washington.

I am so much a journalistic romantic, I still get a thrill seeing my byline in any paper, big or small.

The work is simpler than people let on. Dan Raviv, then with CBS Radio, defined it for me this way, and I have never heard it said better, "I try to find out what is going on and tell people." Quite so.

I don't draw a line between magazines and newspapers, print and broadcast, or the Internet: The work is the same. The key of C, in which it is all centered, is still the newspaper, but that is changing. The struggle for accuracy, fairness and getting at the news never changes.

My first wife, the brilliant English journalist Doreen King, said that to succeed you need the "inner core of panic." That is fear that you made a mistake in a story: got a number wrong (billions not millions, for example), that you misspelled a name, and that you didn't fully understand what you were told in your reporting. The public doesn't know that we really struggle to get it right, often without the luxury of time -- an unending struggle.

Writing columns is something of an art, and some have it and some don't. A column is a newspaper within a newspaper; your own space to give evidence and share ideas. They are a fantastic form of journalism, but they aren't for everyone. To be a reporter you need news judgment. What is news? It is indefinable but if you don't have it, try something else. A test of news judgment is to watch the Sunday morning talk shows and write a mock story. Then survey what the other outlets have picked on and see if you found the same things newsworthy. You will know soon enough if you have news judgement.

I have been writing columns since the very beginning of my career. A young woman, who worked for me on The Energy Daily, was one of the finest reporters I have ever known. But when she was appointed the editorial page editor of a newspaper, she found it hard. Opinion didn't come easily to her. Facts were her domain. She moved to Europe, where she worked for a business information service and flourished. Her meticulous reporting was what was needed there.

If, like me, you have opinions about everything, then writing columns comes easily and the rest is technique. Read how others handled their material. Not what they opined, but how they managed it.

I don't hold that there is any difference between the needs of newspapers and magazines. I believe that news services or newspapers give you a grounding in the disciplines of writing that are very useful in magazine writing.

Journalism can be a hard life. A lot of journalists have money problems, drink to excess, and are known to have messy private lives. But, by God, we tell the world what is going on, and that is to be part of something huge and fabulous. It is a life of sheer adventure. I am glad of it.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Magic mushrooms

“Adventure Time” (C2 paint), by Natalia Rak, at 94 Washington St., Providence, part of the Avenue Concept, which supports public art in the urban setting by means of murals, sculptures and programs.

Chris Powell: When in doubt punt to avoid irritating public

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Gov. Ned Lamont seems to realize that Connecticut probably won't stand for another catastrophic lockdown in the name of controlling COVID-19, a virus that 99.8 percent percent of afflicted people survive. But rather than acknowledge this plainly and caution people that they must take the primary responsibility for protecting themselves, the governor has passed the buck to the state's 169 municipal governments.

The governor is putting them in charge of determining whether and where people should be required to wear masks again. This may lead to giving local officials the authority to set other rules of virus safety.

With the cities lagging badly in virus vaccinations, their mayors seem eager to order masks back on, which will push retail and restaurant business out of the cities and into the suburbs, as if city businesses can afford it.

Local option on virus safety makes little medical sense. Crowds in a suburb may pose no less risk than crowds in a city. But henceforth the resentment felt about the virus epidemic and government's regulations about it may be directed at mayors and town councils instead of the governor.

Lamont is a Democrat and Republicans long have wanted the General Assembly to end his emergency authority to rule by decree, and now, with his epidemic management no longer so successful, the governor may be happy to go along. Call it decentralization, with potentially different rules in 169 little republics and thousands of offices, stores, and restaurants.

Treatments vs. Vaccines

While the government and the medical establishment keep insisting that the virus vaccines are absolutely safe, every week brings word of a new side-effect unknown when the vaccines were authorized for emergency use and said to be so safe. The other week the vaccines were linked to eye problems.

Meanwhile the virus is mutating into "variants," more vaccinated people are becoming infected if not seriously ill, and there are signs that the vaccines may lose effect with time, perhaps as little as six months, thereby requiring frequent booster shots or entirely new shots each year, like ordinary flu shots.

So maybe eventually the government and medical authorities will start wondering whether the approach to the virus should shift to treatment and away from vaccination.

After all, doctors and hospitals have learned to treat virus patients with far more sophistication than shoving ventilators down their throats, as was the practice at the beginning of the epidemic. Does anyone remember the clamor a year and a half ago for production of millions more ventilators? They turned out to kill as many patients as they saved and the clamor stopped.

For there are effective treatments for COVID-19, and two more were announced the other week by Israeli scientists.

The first was about a study validating use against the virus of the anti-parasite drug ivermectin. Its efficacy has been established by other studies but U.S. authorities seek to suppress it lest it interfere with the vaccine campaign.

The second announcement revealed that a medicine based on the CD24 molecule, found naturally in the human body, cures 93 percent of seriously ill virus patients in less than five days.

These treatments appear to be inexpensive and unlike the vaccines have no side-effects. Also unlike the vaccines, there's no big money in them, which may be their weakness.

“Equity’ Isn’t Fair

Government in Connecticut has a funny idea of what it calls "equity.”

Marijuana-retailing permits are to be reserved for "communities" that disproportionately suffered from the futile "war on drugs." But those "communities" also disproportionately profited from the contraband drug trade. For every drug dealer who was prosecuted there were several who made a lot of money and were never caught.

So where is the patronage for people who, despite the futility of the "war on drugs," obeyed the law and forfeited their chance to profit from contraband?

And to overcome skepticism about the COVID-19 vaccines, government is offering prizes and cash bounties to people who accept vaccination after rejecting it so long.

So where are the prizes and bounties for the people who, heeding government's urging, got vaccinated as soon as they could?

"Equity" sounds mainly like a way of discouraging questions.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Mission creep?

The Chinese Tea House at Marble House, in Newport, modeled on 12th Century Chinese Song Dynasty temples.

— Photo by Ekem

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

That the Preservation Society of Newport County runs restaurants at its Breakers Welcome Center and the Chinese Tea House at Marble House and has made some other changes to sex up tourism at the city’s famous mansions continues to rankle some Newporters, who noted that it’s the Preservation Society, not the development society.

I was down in Newport on a lovely day the other week, and it was hopping with people on tours and some just wandering around looking dazed. Compared to, say, New York City, I saw few people wearing masks.

It’s too bad that Route 114, a main drag through Portsmouth and Middletown heading to Newport, is one of the uglier commercial strips in America and yet so close to beautiful natural and manmade sites. One wonders what sort of dubious zoners’ and politicians’ wheeling-dealing went into allowing such a long and depressing stretch.

Planting many more trees along the way would help camouflage some of its horrors. And maybe as the World Wide Web continues to kill brick-and- mortar stores, some of the land can be allowed to revert to open space and housing. The road is a real downer for those expecting beauty to and from The City by the Sea.

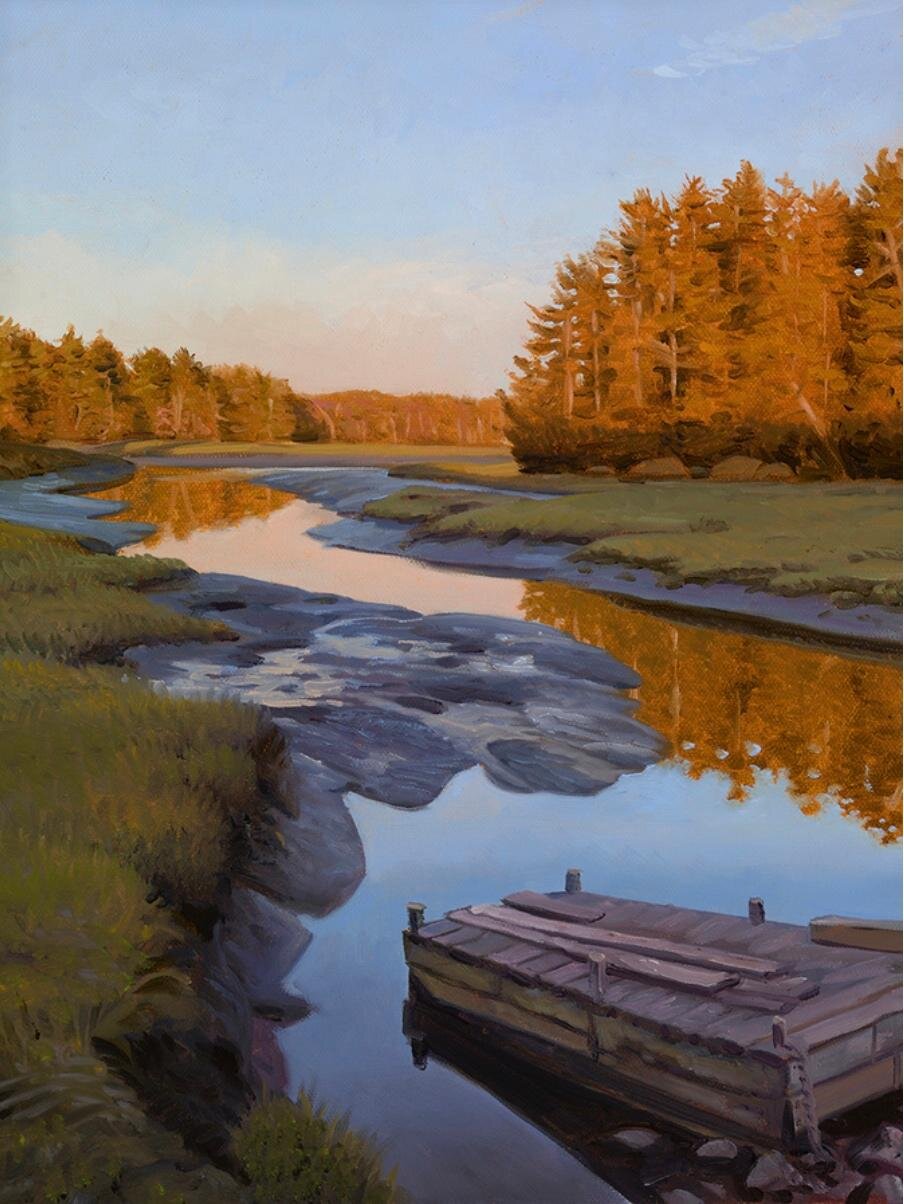

Fragrant and full of life

“Maine #20 —Freeport Sunset’’ (oil on linen), by James Mullen, at Alpers Fine Art, Andover, Mass. Freeport’s marshes are less famous than L.L. Bean, which is based in Freeport.

Sunday stillness

Sunday Aug. 15 on Trenton Street, in Providence’s Fox Point neighborhood, at the head of Narragansett Bay. This picture recalls the work of American painter Edward Hopper.

--Photo by William Morgan

Outward and inner success

”Joy Cometh in the Morning “ (oil on linen), by Rory Jackson, in the “Plein Air 2021” show at Edgewater Gallery, Middlebury, Vt.

He says on his Web site:

“As a painter, my aim is to bring to life a presence to the viewer, a relationship between the earth and the people who hold covenant with it. Whether it is through light, reflection, movement or design, I want to bring everlasting life to a moment in time. As long as I can sense a progression in the development of my work, painting will remain a central part of my life. I think Robert Henri best stated my feeling of what it means to move forward as an artist when he said, ‘All outward success, when it has value, is but the inevitable result of an inward success of full living, full play and enjoyment of one’s faculties.’

“I spend my time between my home in Lincoln, Vt., and the beach of Cape Three Points, Ghana. While painting the landscape of Vermont, I focus on the dramatic light and space around the mountains and valleys, pivoting on my favorite Mountain of Abraham {Mt. Abraham}. In Ghana, I spend time studying seascapes, village scenes, boats, and the reflective light and movement of the sea and the life that depends on its abundance. All honest observation absorbs into my successes, a true vibrancy of life. The balance of the two places keeps my interest in subject matter fresh, while marking each year’s progress in two very different seasons.’’

Mt. Abraham from the west.

A hub of Lincoln, Vt.

=

Brian P.D. Hannon: Of solar power and lots of tomatoes

Young tomato plants for transplanting in an industrial-sized greenhouse.

- Photo by Goldlocki

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

National Grid has offered incentives to a company proposing to build a massive farm facility in rural Exeter, R.I., in exchange for access to the solar power expected to help grow millions of tomatoes in temperature-controlled greenhouses.

A June 24 letter from National Grid senior counsel Andrew Marcaccio to Luly Massaro, a division clerk for the Rhode Island Division of Public Utilities and Carriers, states National Grid will offer “energy efficiency incentives” to Rhode Island Grows LLC “for the utilization of a combined heat and power project with a net output of one megawatt ... or greater.”

A capacity of 1 megawatt or more is a utility-scale installation for solar power.

National Grid asks the public utilities and carriers division to follow an authorized process for combined heat and power (CHP) projects by reviewing materials submitted with the letter, including a purchase-and-sales agreement from Rhode Island Grows related to the project, an estimated budget, benefit cost analysis and a November 2020 analysis providing “well-supported justification explaining why the economic benefits are reasonably likely to be obtained.”

The letter’s attachments also include a report on the natural-gas requirements and local impact of the operation.

“These documents represent a report including a natural gas capacity analysis that addresses the impact of the CHP Project on gas reliability; the potential cost of any necessary incremental gas capacity and distribution system reinforcements; and the possible acceleration of the date by which new pipeline capacity would be needed for the relevant area,” according to the letter.

National Grid’s letter asked the public utilities and carriers division to review the materials and provide an opinion either supporting or opposing the proposal by Aug. 13.

Gail Mastrati, assistant to the director of the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM), supplied a link tracking the progress of the wetland permit sought by Richard Schartner, owner of the Schartner Farms property where Rhode Island Grows plans to build a 1-million-square-foot closed facility.

Asked if Rhode Island Grows is required to file separate permit applications for a solar array capable of producing more than 1 megawatts of power, Mastrati said the wetland and stormwater permit “is based on the size of the solar arrays, not the power output. If the number of solar panels were to increase, a new or modified permit would be required.”

“DEM does not permit the power output, just the size of the facility as indicated on the site plans,” Mastrati wrote in an email.

Mastrati declined to reveal the name of the company providing solar array services to Rhode Island Grows.

“DEM does not get involved with the choosing of the company to perform the work,” she said. “It is up to the owner to ensure that the contractor completes the work according to the permit.”

Rhode Island Grows chairman Tim Schartner and chief financial officer Frederick Laist did not respond to a request for comment.

The Rhode Island Grows project has drawn the support of Ken Ayars, chief of the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s Division of Agriculture, as well as criticism from some Exeter residents concerned about the environmental and cultural impact of the massive growing operation that would use high-tech greenhouses to grow millions of tomatoes for distribution in six states throughout the Northeast.

Rhode Island Grows proposes to use a technology called controlled environment agriculture. The automated, hydroponic system can produce food on a large scale and has resulted in extensive agricultural production in the Netherlands, according to a video on the Rhode Island Grows website.

The company projects the operation could yield 650,000 pounds of tomatoes per acre, with an expansion to 350 acres in five years and eventually to 1,000 total acres, with five employees per acre.

The Exeter Town Council voted June 7 to return the Rhode Island Grows proposal for a zoning overlay district to the Planning Board for further consideration. The overlay would allow construction of the industrial-scale operation on the Schartner Farms property off South County Trail, where Rhode Island Grows prematurely broke ground June 1.

The five members of the council did not respond to a request for comment on the National Grid letter.

Brian P.D. Hanlon is an ecoRI News journalist.

John O. Harney: Latest people moves at N.E. colleges

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

The New Commonwealth Racial Equity and Social Justice Fund named Makeeba McCreary to be the first president of the fund launched by 19 local Black and Brown executives a few weeks after the killing of George Floyd. McCreary recently served as chief of learning and community engagement at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and, before that, as managing director and senior advisor of external affairs for the Boston Public Schools.

University of Maine System Chancellor Dannel Malloy said he would ask system trustees to approve the appointment of Vice President of Academic Affairs and Provost Joseph Szakas as interim president at the University of Maine at Augusta (UMA), while the system searches for a permanent replacement for UMA President Rebecca Wyke. In July, Wyke informed the UMA community that she would step down to become CEO of the Maine Public Employees Retirement System. Szakas will continue in his VP and provost roles while serving as interim leader.

Mark Fuller, who became interim chancellor of the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth in January, was named permanent chancellor this week. He previously served for nine years as dean of the UMass Amherst Isenberg School of Management.

Ryan Messmore, former president of Australia’s Campion College, became the fifth president of Magdalen College of the Liberal Arts in Warner, N.H.

Sharale W. Mathis joined Holyoke Community College as vice president of academic and student affairs. A biologist, she previously was dean of academic and student affairs at Middlesex Community College in Connecticut and STEM division director at Manchester Community College. Mathis was an early adopter of Open Educational Resources (OER), utilizing online resources for supplemental instruction designating that course as no cost to students.

Middlebury College appointed Caitlin Goss as its vice president for human resources and chief people officer. Goss previously served as the director of people and culture at Rhino Foods in Burlington, Vt., and as the team leader for employee engagement in global human capital at Bain & Company.

Johnson & Wales University appointed former Norwich University Executive Vice President of Operations Sandra Affenito to be vice chancellor of academic administration, and Mary Meixell, an industrial engineer and former senior associate dean of Quinnipiac University’s School of Business, to be dean of JWU’s College of Business.

Berkshire Community College appointed Stephen Vieira, former chief information officer for the Tennessee Board of Regents and at the Community College of Rhode Island, to be director of information technology at the Pittsfield, Mass., community college.

John O. Harney is executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

Infernal machines

— Photo by fir0002 fl

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,” in GoLocal24.com

A Providence mayoral candidate could get a lot of votes with credible promises for the city to crack down hard on ATV and dirt-bike users. They must be made very scared to ride in the city. The State of Rhode Island, through the State Police and new laws, must also bring much more force to bear against these potentially lethal and out-of-control offenders. Arrest, immediate jail, conviction and a memorable stay in the ACI.

And a candidate could also gain more than a few votes by supporting a ban on gasoline-fueled, shrieking and polluting leaf blowers. It used to be that these infernal devices were mostly confined to blowing fallen leaves into piles to be trucked away in mid and late autumn. Now they’re used year-round to (often pointlessly) blast dust and other debris around, turning the surrounding neighborhoods into dead zones while they work.

Affluent property owners employ yard crews of hard-working illegal aliens (too few of whom are wearing ear protection) to wield these things; I’ve noticed that many of the owners often arrange to be away at their summer or weekend houses when the crews show up.

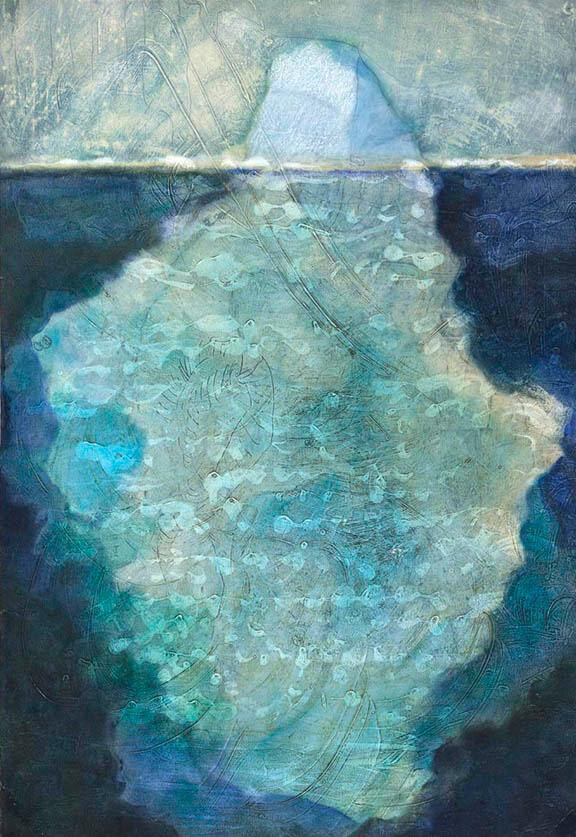

But you usually can't see the dangerous part

“Floating Island’’ (oil and mixed media on paper), by Kata Hull, in the group show of New England artists titled “Cool” at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, through Aug. 22.

The gallery says:

“Chilly, poised, nerveless, refreshing, brilliant. This exhibition features art work that helps everyone cool of in the heat of the summer.’’

Before the summer folks

Provincetown, at the tip of Cape Cod, in the years when Thoreau walked the peninsula— 1849, 1850 and 1855.

“The time must come when this coast (Cape Cod) will be a place of resort for those New-Englanders who really wish to visit the sea-side. At present it is wholly unknown to the fashionable world, and probably it will never be agreeable to them. If it is merely a ten-pin alley, or a circular railway, or an ocean of mint-julep, that the visitor is in search of, — if he thinks more of the wine than the brine, as I suspect some do at Newport, — I trust that for a long time he will be disappointed here. But this shore will never be more attractive than it is now.”

Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) in Cape Cod, first published in 1865, soon before railroads started to make The Cape a major summer-resort area.

At New Silver Beach, in Falmouth, on the western side of The Cape — probably not quite what Thoreau could have foreseen.

'Insane song'

Loon in Marshfield, Vt.

— Photo by Ano Lobb

,

“Summer wilderness, a blue light

twinkling in trees and water, but even

wilderness is deprived now. ‘What's that?

What is that sound? ‘ Then it came to me,

this insane song, wavering music….’’

— From “The Loon on Forrester’s Pond,’’ by Hayden Carruth (1921-2008), celebrated American poet who lived for years in Johnson, Vt.