Black or white only

Nathanael Herreshoff climbing aboard Defender in 1895; Herreshoff designed five successful America’s Cup defenders in 1993-1920, including Defender.

-- Photo by John S. Johnston

“There are only two colors to paint a boat, black or white, and only a fool would paint a boat black.’’

— Nathanael G. Herreshoff (1848-1938), famed naval architect. He was born and died in Bristol, R.I. He died on June 2, 1938, thereby missing the great hurricane that wrecked the Herreshoff boatyard in Bristol on Sept. 21 of that year.

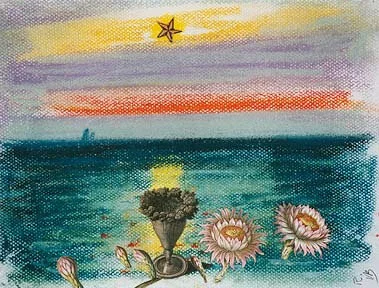

Star power

“Star’’ (mixed media), by Paul Resika and the late Varujan Boghosian, in a show at the Berta Walker Gallery, Provincetown, Mass., through Aug. 14.

The gallery’s motto is “the history of American Art as seen through the eyes of Provincetown.’’

Don Pesci: Unstable Democratic coalition is breaking down

— Photo by Heptagon

VERNON, Conn.

Former Vice President Joe Biden may have campaigned for president as a Kennedy Democrat, but his nose ring while in office has been fashioned in a far-left smithy. And whenever Biden feels the tug, he moves inexorably to the left.

When the late Barry Goldwater said “If you lop off California and New England, you’ve got a pretty good country,” he meant that the ideological and historical center of the country should be central to Democrat and Republican politics.

U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and U.S. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer naturally think differently. The locus of political power within the Democratic Party is precisely that portion of the country Goldwater would have lopped off, the New England states plus New York and California. Pelosi is from California, Schumer from New York.

Since the Obama administration, the national Democratic Party has been able to cobble together a majority by including within its “Big Tent,” more narrowly constricted ideologically than most people realize, an eccentric coalition of the supposed disenfranchised: African Americans, some of whom are now straying dangerously into conservative territory; working women, enfranchised by the 19th Amendment, enacted in 1920, and liberated from their kitchens by World War II; paroled criminals; libertarian drug users; chronic gamblers; citizens of Honduras who have crashed our border with Mexico and who, some mildly assert, may not be prevented from voting in U.S. elections if they are not compelled to produce at poll stations proof of citizenship; Critical Race Theorists who really do believe, solipsistically, that U.S. history has always revolved around a racial- discrimination pole; teachers who would rather stay home than teach; a Coronavirus-sidelined General Assembly that continues to rent out to Connecticut’s governor powers and responsibilities the constitution assigns to legislators; cities, most of them run by Democrats during the past half century, smoldering in violence and crime induced, leftists believe, by ill-mannered, unrestrained cops; and so on and so on…

We are witnessing the breakdown of this temporary and unstable coalition. And the battering rams smashing it are unblinking views of reality.

The mother of a three-year-old child murdered by a 19 year-old kid who couldn’t shoot straight knows, in her heart of hearts, that the politicians who showed up in Hartford to mug for the TV cameras were not there to help, because nothing they had done in the past half century in Hartford had helped to reduce crime or make any Connecticut large city as pleasant and prosperous a place to live as, say, Glastonbury, a suburb of Hartford lately experiencing its own uptick in crime.

In a previous posting, “Politicians And The Memory Hole”, this writer predicted at the time that “it would take politicians who turned up to commiserate with stricken family members – [Connecticut Sen. Dick] Blumenthal, known to show up, as he said, ‘at garage door openings,’ appeared to be absent without a by-your-leave -- only a few hours to forget the child’s name. A 29 year-old woman, walking her dog a few blocks from the murder scene, was asked by a reporter to comment. ‘I was raised in this neighborhood,’ she said, ‘It’s always been kind of a thing, especially when the weather starts to warm up. It’s kind of expected.’”

Along with the dominant Democratic Party in Connecticut, leaning left for a good many years, those who report on politics in the state also are left-leaning. Partly, this is natural. Reporters report on power-players, and the Connecticut GOP, especially in cities, has been unplugged for a long while. Editorial page editors listing left are temperamentally hostile to contrarians, many of them preferring supportive opinion that reaffirm editorial views.

It is human nature to purr at flattery.

“Everyone likes flattery,” Benjamin Disraeli, British prime minister in Victorian days, said, “and when you come to royalty, you should lay it on with a trowel.”

Leading Democrats in Connecticut are the state’s royalty.

Contrarian opinion on op-ed pages is a marker indicating editorial vigor. To put it mildly, one does not find contrarian opinion on matters affecting the state laid on with a trowel in most Connecticut news publications. Then too, it is easier, indeed effortless, to swim with rather than against the current. G. K. Chesterton, a favorite contrarian, tells us that even a dead thing can flow with the current, but only a live body can struggle effectively against the current. Swimming upstream against the current is becoming in Connecticut a rare heroic act.

If Republicans were to capture more seats in the General Assembly, maybe even the governor’s office, Connecticut’s media might, for business reasons, be more open to contrary opinion. And, of course, contrarian opinion just might enliven papers and boost sagging sales.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

Julie Appleby: Biogen launches propaganda campaign to promote its costly Alzheimer’s drug

Cognitive tests such as the Mini–Mental State Examination (MMSE) can help diagnose Alzheimer's disease. In this test instructions are given to copy drawings like the one shown, remember some words, read, and subtract numbers serially.

Do you sometimes lose your train of thought or feel a bit more anxious than is typical for you?

Those are two of the six questions in a quiz on a Web site co-sponsored by the makers of Aduhelm, a controversial new Alzheimer’s drug. But even when all responses to the frequency of those experiences are “never,” the quiz issues a “talk to your doctor” recommendation about the potential need for additional cognitive testing. The drug would cost an estimated $55,000 a year per patient.

Facing a host of challenges, Aduhelm’s makers Cambridge, Mass.-based Biogen and its partner Tokyo-based Eisai are taking a page right out of a classic marketing playbook: Run an educational campaign directed at the consumer, one who is already worried about whether those lost keys or a hard-to-recall name is a sign of something grave.

The campaign — which also includes a detailed advertisement on The New York Times’ Web site, a Facebook page and partnerships aimed at increasing the number of places where consumers can get cognitive testing — is drawing fire from critics. They say it uses misleading information to tout a drug whose effectiveness is widely questioned.

“It’s particularly egregious because they are trying to convince people with either normal memories or normal age-related decline that they are ill and they need a drug,” said Dr. Adriane Fugh-Berman, a pharmacology professor at Georgetown University Medical Center, who wrote about the website in an opinion piece.

The Web site’s “symptoms quiz” asks about several common concerns, such as how often a person feels depressed, struggles to come up with a word, asks the same questions over and over, or gets lost. Readers can answer “never,” “almost never,” “fairly often” or “often.” No matter the answers, however, it directs quiz takers to talk with their doctors about their concerns and whether additional testing is needed.

While some of those concerns can be symptoms of dementia or cognitive impairment, “this clearly does overly medicalize very common events that most adults experience in the course of daily life: Who hasn’t lost one’s train of thought or the thread of a conversation, book or movie? Who hasn’t had trouble finding the right word for something?” said Dr. Jerry Avorn, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School who has been sharply critical of the approval.

Aduhelm was approved in June by the Food and Drug Administration, but that came after an FDA advisory panel recommended against it, citing a lack of definitive evidence that it works to slow the progression of the disease. The FDA, however, granted what is called “accelerated approval,” based on the drug’s ability to reduce a type of amyloid plaque in the brain. That plaque has been associated with Alzheimer’s patients, but its role in the disease is still being studied.

News reports also have raised questions about FDA officials’ efforts to help Biogen get Aduhelm approved. And consumer advocates have decried the $56,000-a-year price tag that Biogen has set for the drug.

On the day it was approved, Patrizia Cavazzoni, the FDA’s director of the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said the trial results showed it substantially reduced amyloid plaques and “is reasonably likely to result in clinical benefit.”

Describing the Web site as part of a “disease awareness educational program,” Biogen spokesperson Allison Parks said in an email that it is aimed at “cognitive health and the importance of early detection.” She noted that the campaign does not mention the drug by name.

On July 22, in “an open letter to the Alzheimer’s disease community,” Biogen’s head of research, Dr. Alfred Sandrock, noted the drug is the first one approved for the condition since 2003 and said it has been the subject of “extensive misinformation and misunderstanding.” Sandrock stressed a need to offer it quickly to those who have only just begun to experience symptoms so they can be treated before the disease moves “beyond the stages at which Aduhelm should be initiated.”

While the drug has critics, it is also welcomed by some patients, who see it as a glimmer of hope. The Alzheimer’s Association pushed for the approval so that patients would have a new option for treatment, although the group has objected to Biogen’s pricing and the fact that it has nine years to submit follow-up effectiveness studies.

“We applaud the FDA’s decision,” said Maria Carrillo, chief science officer for the association. “There’s a benefit to having access to it now” because it is aimed at those in the early stages of dementia. Those patients want even a modest slowdown in disease progression so they have more time to do the things they want to accomplish, she said.

The drug is given by infusion every four weeks. It also requires expensive associated care. About 40 percent of the patients in the trials experienced brain swelling or bleeds, so regular brain imaging scans are also required, according to clinical trial results and the drug’s label. In addition, patients will likely need to be checked for amyloid protein, which is done with expensive PET scans or invasive spinal taps, according to Alzheimer’s experts.

To educate more potential patients, and customers, Biogen announced it has teamed with CVS to offer cognitive testing, and with free clinics for dementia education efforts.

Biogen is also picking up some of the laboratory costs for patients who get a spinal tap.

Still, the drug faces headwinds: There’s a congressional probe of the drug’s approval, the head of the FDA has called for an independent investigation of its review process, and there’s pushback from policy experts and insurers over its price, which they say could seriously strain Medicare’s finances. Some medical systems, including the Cleveland Clinic and Mount Sinai, say they won’t administer it, citing efficacy and safety data.

None of that is mentioned in Biogen’s campaign.

Instead, the advertisements and Web sites focus on what is called mild cognitive impairment, including a warning that 1 in 12 people over age 50 have that condition, which it describes as the earliest clinical stage of Alzheimer’s.

On its Web site, Biogen doesn’t cite where that statistic comes from. When asked for the source, Parks said Biogen’s researchers made some mathematical calculations based on U.S. population data and data from a January 2018 article in the journal Neurology.

Some experts say that percentage seems high, particularly on the younger end of that spectrum.

“I can’t find any evidence to support the claim that 1 in 12 Americans over age 50 have MCI due to Alzheimer’s disease. I do not believe it is accurate,” said Dr. Matthew S. Schrag, a vascular neurologist and assistant professor of neurology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, in Nashville.

While some people who have mild cognitive impairment progress to Alzheimer’s — about 20 percent over three years — most do not, said Schrag: “It’s important to tell patients that a diagnosis of MCI is not the same as a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s.”

Mild cognitive impairment is tricky to diagnose — and not something a simple six-question quiz can uncover, said Mary Sano, director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at the Icahn School of Medicine in New York.

“The first thing to determine is whether it’s a new memory problem or a long-standing poor memory,” said Sano, who said a physician visit can help patients suss this out. “Is it due to some other medical condition or a lifestyle change?”

Carrillo, at the Alzheimer’s Association, agreed that MCI can have many causes, including poor sleep, depression or taking certain prescription medications.

Based on a review of medical literature, her organization estimates that about 8 percent of people over age 65 have mild cognitive impairment due to the disease.

She declined to comment on the Biogen campaign but did say that early detection of Alzheimer’s is important and that patients should seek out their physicians if they have concerns rather than rely on “a take-at-home quiz.”

Schrag, however, minced no words in his opinion of the campaign, saying it “feels like an agenda to expand the diagnosis of cognitive impairment in patients because that is the group they are marketing to.”

Julie Appleby is a journalist with Kaiser Health News.

‘Moxie' —the painting, the drink and the courage

“Moxie” (acrylic on canvas), by William Conlon, in the group show art “Here & There,’’ at Cove Street Arts, Portland, Maine, through Sept. 11. Mr. Conlon lives and works on an island in Portland in the summer and in New York City in the fall.

The show features the work of 16 artists bridging the Pine Tree State and New York City.

The gallery says: “Since the early 1800s, artists have been drawn to Maine for its rugged coastline, its mysterious, primeval-feeling forests, and its magnificent quality of light. Later, Modernists such as Marsden Hartley, John Marin, Max Weber, and Marguerite and William Zorach made their summer homes here, establishing a trend that continued, post-World War II, when Maine became an annual destination for New York artists seeking respite and rejuvenation from the grit and the fast-flashing pace of the city.”

Portland from above, looking north along I-295. Note the islands in Casco Bay.

— Photo by Tye dye 9205

The word “moxie’’ has New England roots. It’s a carbonated beverage brand that was among the first mass-produced soft drinks in the United States. It was created around 1876 by Augustin Thompson (born in Union, Maine) as a patent medicine called "Moxie Nerve Food" and was produced in Lowell, Mass.

It’s flavored with gentian root extract, a very bitter substance commonly used in herbal medicine.

Moxie, designated the official soft drink of Maine in 2005, continues to be regionally popular today, particularly in New England. It was produced by the Moxie Beverage Co. of Bedford, N.H., until Moxie was purchased by The Coca-Cola Co. in 2018.

The name has become the word "moxie" in American English, meaning courage, daring, or determination. It was a favorite word of the ruthless Joseph P. Kennedy, father of the famous political family that included President John F. Kennedy. If he liked someone, he’d say “he has moxie!

'The world as given'

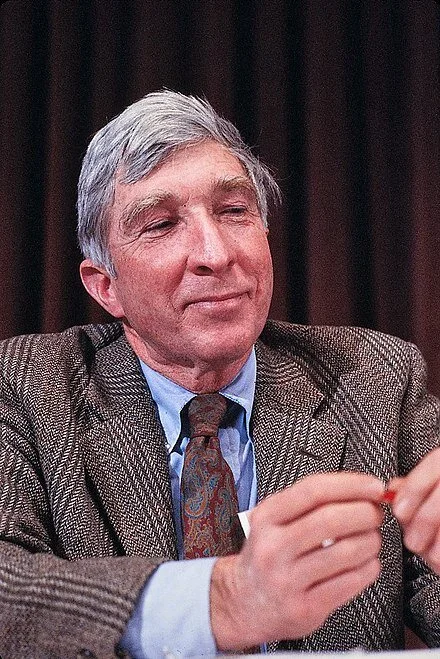

John Updike in 1986

“To say that war is madness is like saying that sex is madness: true enough, from the standpoint of a stateless eunuch, but merely a provocative epigram for those who must make their arrangements in the world as given.’’

— John Updike (1932-2009), in Self-Consciousness, a memoir. Updike was a celebrated novelist, poet, short-story writer, art critic and literary critic. Raised in Pennsylvania, he spent most of his life on the Massachusetts North Shore, including Ipswich, Georgetown andfor his last 30 years, in very affluent Beverly Farms. He came to be considered America’s leading man of letters.

— By Sswonk

Sam Pizzigati: Ego-space-tripping billionaires want more tax breaks

Jeff Bezos’s space-project production facilities near the Kennedy Space Center, in Florida

— Photo by MadeYourReadThis

Via OtherWords.org

BOSTON

Three of the richest billionaires on Earth are now spending billions to exit Earth’s atmosphere and enter into space. The world is watching — and reflecting.

Some charmed commentators say the billionaires racing into space aren’t just thrilling humankind — they’re uplifting us. The technologies they develop “could benefit people worldwide far into the future,” says Yahoo Finance’s Daniel Howley.

But most commentators seem to be taking a considerably more skeptical perspective.

They’re dismissing the space antics of Richard Branson, Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk as the ego trips of bored billionaires — “cynical stunts by disgustingly rich businessmen,” as one British analyst puts it, “to boost their self-importance at a time when money and resources are desperately needed elsewhere.”

“Space travel used to be about ‘us,’ a collective effort by the country to reach beyond previously unreachable limits,” writes author William Rivers Pitt. “Now, it’s about ‘them,’ the 0.1 percent.”

The best of these skeptical commentators can even make us laugh.

“Really, billionaires?” comedian Seth Meyers asked earlier this month. “This is what you’re going to do with your unprecedented fortunes and influence? Drag race to outer space?”

Let’s enjoy the ridicule. But let’s not treat the billionaire space race as a laughing matter.

Let’s see it as a wake-up call — a reminder that we don’t only get billionaires when wealth concentrates. We get a society that revolves around the egos of the most affluent and an economy where the needs of average people don’t particularly matter.

Characters like Elon Musk, notes Paris Max, host of the Tech Won’t Save Us podcast, are using “misleading narratives about space to fuel public excitement” and gain tax-dollar support for various projects “designed to work best — if not exclusively — for the elite.”

The three corporate space shells for Musk, Bezos and Branson — SpaceX, Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic — have “all benefited greatly through partnerships with NASA and the U.S. military,” notes CNN Business. Their common corporate goal: to get satellites, people, and cargo “into space cheaper and quicker than has been possible in decades past.”

Branson is hawking tickets for roundtrips “to the edge of the atmosphere and back” at $250,000 per head. He’s planning some 400 such trips a year, observes British journalist Oliver Bullough, about “almost as bad an idea as racing to see who can burn the rainforest quickest.”

The annual U.N. Emissions Gap Report last year concluded that the world’s richest 1 percent do more to foul the atmosphere than the entire poorest 50 percent combined. Opening space to rich people’s joyrides would stomp that footprint even bigger.

Bezos and Musk seem to have grander dreams than mere space tourism — they’re looking to colonize space. They see space as a refuge from an increasingly inhospitable planet Earth. And they expect tax-dollar support to make their various pipe dreams come true.

How should we respond to all this?

We should, of course, be working to create a more hospitable planet for all humanity. In the meantime, advocates are circulating tongue-in-cheek petitions that urge terrestrial authorities not to let orbiting billionaires back on Earth.

“Billionaires should not exist…on Earth or in space, but should they decide the latter, they should stay there,” reads one Change.org petition nearing 200,000 signatures.

Ric Geiger, the 31-year-old automotive-supplies account manager behind that effort, is hoping his petition helps the issue of maldistributed wealth “reach a broader platform.”

Activists like Geiger are going down the right track. We don’t need billionaires to “conquer space.” We need to conquer inequality.

Sam Pizzigati, based in Boston, is an associate fellow and co-editor of Inequality.org at the Institute for Policy Studies. He’s the author of The Rich Don’t Always Win and The Case for a Maximum Wage.

This op-ed was adapted from Inequality.org and distributed by OtherWords.org.

Ending the day in Gloucester

“Ten Pound Island {in Gloucester, Mass.} at Sunset” (1851) (oil on panel), by Fitz Henry Lane (1804-1865), at the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester.

David Warsh: Monopolistic Amazon is headed for breakup

The Amazon Spheres, part of the Amazon headquarters campus in Seattle

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Public sentiment that government should write new rules for the enterprise economy, comparable to the laws of 1892 and 1914, is growing. Firms based on Internet and block chain technologies in the 21st Century are proving comparable to the railroad, electricity and internal-combustion industries that emerged in the 19th (all of them based on the invention of interchangeable parts). Successful entrepreneurs have demonstrated that rules beyond the Sherman and Clayton Acts are required.

Meanwhile, there is Amazon.

One thing we learned from the Microsoft case in 2001 was that potentially successful anti-monopoly actions are possible. What’s required is drop-dead proof that the law has been broken and a remedy easy to understand. US District Court Judge Thomas Penfield Jackson, having ruled for the Justice Department that Microsoft has had deliberately snuffed out Netscape, set out to break Microsoft into two companies, one selling operating systems, the other applications

It didn’t happen; the conservative Washington, D.C., Circuit Court threw out the case on a technicality and politics moved on. But twenty years on, politics are back. It is intuitively obvious that the world would be a better place if the remedy had been effected. The Leviathan would have been forced to compete on two fronts instead of one. .

The Microsoft case is worth remembering when it comes to thinking about what to do about Amazon.

Matt Stoller, an anti-monopoly newsletter writer, thinks that Washington. D.C. Atty. Gen. Karl Racine has identified the smoking gun and filed suit. It’s that “free delivery” promise. It works like this, says Racine: a “most-favored nation” provision written into the Amazon contract requires that vendors not sell their goods for less in other venues, thereby raising aggregate prices to Amazon levels across the board and so harming consumers in the bargain – a violation of the Sherman Act.

For those who don’t want to read the 30-page government complaint (which is itself quite lucid), Stoller describes the argument clearly. It boils down to this: as founder Jeff Bezos himself put it in 2015, “Fulfillment by Amazon is important because it is the glue that inextricably links Marketplace and Prime.” A third of all shoppers abandon their carts when they see shipping charges. Amazon wants customers to think of whatever they have ordered and the promise of free shipping as part of their $119 annual membership fee as a unified “mega-product,” Stoller writes. What Bezos likes to call a “flywheel” exists to make the decision to buy all but inevitable. Indeed, Stoller continues, “Anytime you hear the word ‘flywheel’ relating to Amazon, replace it with ‘monopoly’ and the sentence will make sense.”

It seems clear to me from the government’s complaint that an “everything store” has no business in the delivery business, though it may take a long time to prove it in court. Bezos traveled to the edge of space on July 20, but Amazon is bound for break-up. Running afoul of the Sherman Act is one thing. The problems with Facebook, Google, Apple and Microsoft (and with the banking, pharmaceutical and agricultural industries) are more complicated. They have to do with advertising and big data. These new angles may require new legislation.

With Amazon, the question is what to do next. Nationalize Prime and fold it into the U.S. Postal Service? (Remember, the original charm of the postal system was the fact that purchase of a first-class stamp would insure that the letter would be delivered anywhere in the nation.) Or perhaps force a divestiture and set Prime in competition with United Parcel Service, Federal Express, and DHL? In that case, what to do about the USPS?

For now, it’s a question for the Department of Justice, the National Association of Attorneys General, and the economists they will eventually hire to devise remedies, (It was Rebecca Henderson, of the Harvard Business School; Paul Romer, then of Stanford University’s Graduate School of Business; and Carl Shapiro, of the University of California at Berkeley, who proposed the “ops and apps” remedy in the Microsoft case.)

President Biden still hasn’t nominated an assistant attorney general for Antitrust. Plenty of turmoil has been ongoing behind the scenes. For a reliable guide to the differences among the Chicago School, the Modern approach, and the Populists’ view, see “Antitrust: What Went Wrong and How to Fix It,” by Cal-Berkeley’s Shapiro. It seems fair to say that the whole world is watching.

. xxx

Andreu Mas-Colell, 77, is one of the most widely respected economists in the world, possessing rank as a teacher slightly different from that of a Nobel Prize-worthy researcher. He was a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, then Harvard University, and his microeconomics textbook is widely used in top graduate programs around the world. President of the Econometric Society in 1993, he left Harvard in 1995 to participate in the founding of the University of Pompeu-Fabra in his native Barcelona.

Named secretary general of the European Research Council, in 2009, he resigned a year later to become cabinet minister for the economy of Catalonia, four prosperous provinces in northeast Spain whose longstanding desire for independence has been an especially divisive issue since the restoration of Spanish democracy, in the 1970s. Mas-Colell resigned his post a year before Catalonia conducted a referendum in 2017 and declared itself autonomous in a manner deemed by the Spanish government to have been illegal.

As part of proceedings against 34 former Catalan officials, Mas-Colell was recently accused of misspending funds in pursuit of Catalonia’s independence. Spain’s Court of Auditors, an administrative body that oversees public accounts, imposed penalties of as much as €2.8 million (about $3.3 million) which the accused would have to pay immediately, before they can appeal them in court. Fellow economists around the world, have rallied to Mas-Colell’s defense, kept abreast of matters by his son, Alexandre. a Princeton University economist.

A friend in Barcelona writes:

The Catalan Government is trying to use (indirectly) public funds to post bail for the defendants; the Spanish government will take a careful look to make sure the arrangement is legally correct. Meanwhile, Mas-Colell has published a well-thought-out article stating that it is improper for an administrative tribunal to employ procedures normally the province of the judiciary. I assume all will end well (not for the reputation of the Court of Auditors) Mas-Colell? All through his life he has been willing to take risks and to make sacrifices for causes he thought were good.

Correspondent Xavier Fontdegloria writes in The Wall Street Journal, “Spain’s Socialist Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez is trying to defuse the long-running confrontation with Catalan nationalists by pursuing talks aimed at conciliation.”

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran.

Robert Davey: Film would deconstruct what really happened to TWA Flight 800

Wreckage of TWA 800 being reconstructed at Calverton Executive Airpark, in Riverhead, New York, by the National Transportation Safety Board in May 1997

Flight path of TWA 800. The colored rectangles are areas from which wreckage was recovered.

BRIDGEPORT, Conn.

What would a documentary film about the crash of TWA Flight 800 look like? For more than six years I have been a member of a group of four journalists at a series of meetings (paused by the pandemic) to try to raise something over $1 million to make what we intend will be the definitive account of what really destroyed a 25-year-old Boeing 747-100 and killed its total of 230 passengers and crew, only 12 or so minutes after leaving Kennedy International Airport, in New York City, on an overnight flight to Paris on July 17, 1996. This year marks 25 years since the crash.

Our group is rich in experience. Three are veterans of TV news, while I owe my place on the team to my work reporting on the story for the Village Voice in the late 90s and early aughts. After three years, we were joined by physicist Tom Stalcup, whose own documentary film on the crash, TWA Flight 800, released in 2013, received favorable reviews. That film, directed by former CBS journalist Kristina Borjesson, raised questions about the official conclusion of the National Transportation Safety Board that an electrical fault produced a spark that ignited fuel vapors in the airplane’s almost empty center fuel tank. Tom was keen to join us and help make a second film that would finish the job.

Our film will show that the huge, gentle beast that was that 747, tail number N93119, was perfectly safe, with no hitherto unsuspected ignition sources lurking within its complex systems and miles of wiring.

As part of that effort I am looking forward to being able to demonstrate that the NTSB falsely insinuated that a tiny amount of liquid Jet A kerosene fuel—too little to register on the aircraft’s fuel gauges—could have evaporated inside a vast tank with a capacity of just under 13,000 gallons and then exploded with such force that the 400,000-pound aircraft disintegrated within seconds.

Government research into the flammability of hydrocarbon fuels and gases goes back to work done by the U.S. Bureau of Mines in the 1950s, and continued in the following decades with reports produced by the Navy and Air Force and Federal Aviation Administration. These reports explain that if there is too little fuel vapor per unit volume of air, the mixture will be too lean to burn, and if there is too much, it will be too rich to burn.

In our film it will be satisfying to be able to report that, for example, NTSB investigators were able to ignite a warm mixture of Jet A fuel vapor and air equivalent to what they estimated was contained within TWA 800’s center tank at about 13,700 feet, but only with a spark produced by a current far stronger than any on the 747. Even then, ignition only lasted for a brief moment. A mixture is not technically flammable unless it will burn independently of the ignition source, yet the NTSB’s tests never showed that this was possible with the vapor mixture investigators tested.

For most of its ignition experiments, the NTSB used small laboratory flasks, but the largest-scale and most spectacular of the tests that it showed the public was conducted in what it called a “quarter-scale” tank.

The safety board did not explain for reporters and family members that while its quarter-scale tank had dimensions a quarter of the size of the dimensions of TWA 800’s center fuel tank, its volume was really only one 64th the volume of a full-sized tank, about 200 gallons, although it acknowledged this size difference in a footnote of its report.

Size evidently matters when a mixture of fuel vapor and air is ignited, since some of the military research into fuel flammability established that the larger the container, the smaller the force produced when the military equivalent of Jet A vapor explodes.

The quarter-scale tests were no match for TWA 800’s center tank, which was 64 times larger. But apart from that, the NTSB used in its quarter-scale tests not Jet A vapor, but a mixture of propane and hydrogen and air, and an ignition source much more powerful than any that existed, even as a remote possibility, on any 747.

Yet investigators never demonstrated that the mixture’s explosive characteristics matched those of Jet A, at any altitude. Hydrogen, after all, is highly flammable, and propane is considered so dangerous that supermarkets bar customers from bringing even empty canisters inside the store.

On that question, I’d like to include a comment from a professor at Leeds University, in England, John Griffiths, co-author of Flame and Combustion (Blackie Academic and Professional, Third ed., 1995), who told me, after reviewing a description of the quarter-scale tests, that as the ignited mixture of propane and hydrogen and air encountered structural panels inside the tank, it became “turbulent,” a technical term meaning more rapid and violent. He said he’d be “astonished” if the ignition of a mixture of Jet A vapor and air would have developed in a comparable way.

And I would like our film to make public an incident that occurred in 1995, a little more than a year before its final flight, when N93119 was approaching Rome and was twice struck by lightning. The flight engineer told me the story, and he also showed me a photograph of the airplane after it landed safely at Rome, with its right-wing tip damaged by the lightning strikes. The tail number is clearly visible in the photo. He told me the lightning had charred wiring near the wing fuel tanks on that side. Yet no fire and explosion had happened, and the 747 had landed safely. I looked up the NTSB’s TWA 800 maintenance report, but I could not find any record of the lightning incident and the repairs to the wing, which were visible in a July 29, 1996, Time magazine cover photo of floating debris. Yet a Boeing spokesman told me that the information had been shared with the NTSB.

In a way, the 1995 incident was a bookend to another incident at Rome, in 1964, one that did not end so well, when another TWA Flight 800, a Boeing 707, struck a steamroller on the tarmac as the pilot was attempting to abort his takeoff after an engine failed. A flame traveled down the wing and into the center fuel tank, which exploded into a horrific fire. A total of 51 people were killed and another 23 injured.

The captain of the plane, Vernon William Lowell, wrote a book — Airline Safety Is a Myth — in which he blamed the disaster on the flammable fuel vapor in his almost-empty center tank—a situation uncannily similar to the NTSB’s probable cause for the 1996 TWA 800 explosion, except for the fact that the fuel in his tank was a fuel known as JP-4, a petroleum-derived mixture that was far more volatile than Jet A kerosene. He says that most airlines were already voluntarily switching to Jet A fuel, for safety’s sake, and wonders what was holding the FAA back from banning JP-4, also known as Jet B.

The NTSB, at a session on fuel flammability at its December 1997 TWA Flight 800 hearings, in Baltimore, for some reason never mentioned the earlier TWA 800, but instead focused on the case of PanAm Flight 214, a Boeing 707 that crashed in Elkton, Md., in December 1963 after lightning struck its left wing, a fuel tank containing a mixture of Jet A and Jet B exploded, and the wing fell off.

Lowell, the captain of the 1964 TWA 800, points to partially filled or empty fuel tanks as an unacceptable hazard because the fuel vapor that fills them is flammable. That’s very similar to the NTSB’s message at Baltimore.

Yet, assuming that the safety board was aware of the 1995 lightning incident, someone at Baltimore might have pointed out that N93119, fueled by Jet A kerosene, survived those two mega-voltage jolts with flying colors; but that would not have helped the NTSB’s argument that there had been no improvements in fuel-tank safety since PanAm 214, and that only now, with the TWA 800 crash, were investigators facing up to the dangerously explosive conditions in aircraft fuel tanks that threatened every passenger and crew member.

In an FAA database of fuel-tank explosions, there are none, before TWA Flight 800 (1996), in which a plane crashed because an electric spark produced by the aircraft’s own systems ignited an explosion in a fuel tank containing only Jet A kerosene.

I hope that we meet someone interested in funding our film soon.

Robert Davey is a Bridgeport-based journalist. See: www.robertdavey.com or www.seedyhack. com

His email is rj_davey@me.com

Go back where you came from

Junction signage in Newfields, N.H., as seen in 2005 (left) and 2019. It’s a beautiful small town to find yourself in, even if you’re lost. See below.

"We don't enjoy giving directions in New Hampshire. We tend to think if you don't know where you're going, you don't belong where you are."

— John Irving (born 1942), novelist who was born and raised in Exeter, N.H.

Squamscott Street in Newfields

“Newfields, New Hampshire ‘‘(1917), by Childe Hassam, at the Princeton University Art Museum

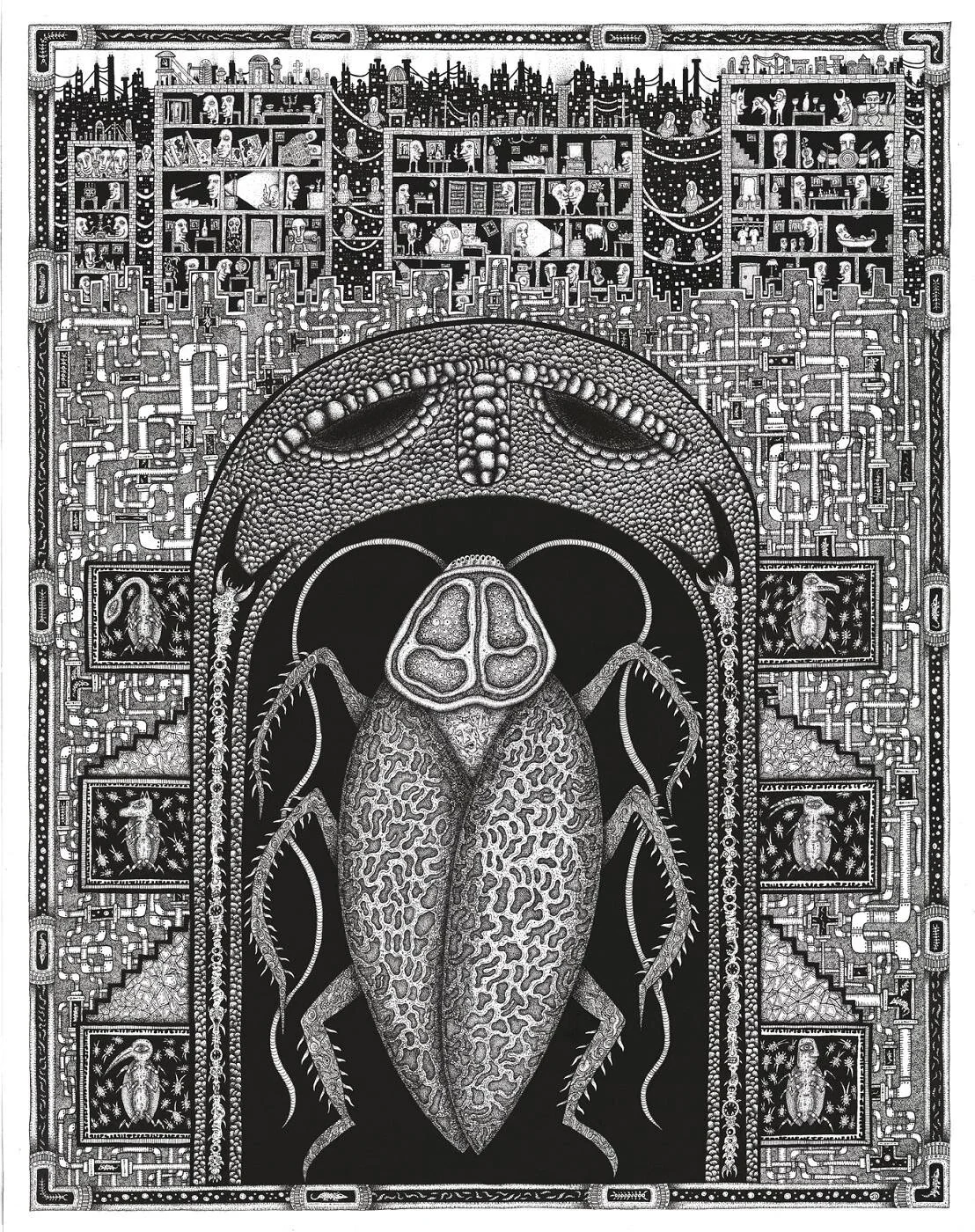

Monarch of metroland

“Citadel of the Roach Queen” (dip pen and India ink), by Worcester-based James Dye, in the New England XI, a regional juried exhibition, at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, Aug. 6-29. Mr. Dye grew up in Holden, near Worcester.

Holden Center

Clothing, brutality and movies

In “Ruth E. Carter’s Costume Retrospective’’ at the New Bedford Art Museum: Left to Right: '‘Malcolm X costume” from the film Malcolm X (1992); “Martin Luther King, Jr. and Coretta Scott King costumes” from the film Selma (2014); “Mookie costume” from the film Do the Right Thing (1989); “Rudy Ray Moore costume'‘ from the film, Dolemite is My Name” (2019). Photographs by Don Wilkinson.

Don Wilkinson comments:

"From days of slavery and human bondage represented by Roots, throughout the early days of the modern Civil Rights Movement of Malcolm X and Selma and onto the culturally significant Blaxploitation era pegged by Dolemite is My Name, Carter and her crew nail it.

“And what of Do the Right Thing? It’s a 32-year-old movie that is as relevant now as it was when it was released. The critical moment in it is when Radio Raheem is choked to death by a cop’s nightstick despite the cries and pleadings of onlookers. Nightstick or knee...the story is the same.’’

Chris Powell: To end corporate welfare, cut taxes for all business

“The tax collector's office’’ (1640), by Pieter Brueghel the Younger

MANCHESTER, Conn.

At Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont's order, state government is reducing its direct subsidies to businesses coming into the state or expanding here -- cash grants, discounted or forgivable loans and tax credits. These subsidies have reeked of political patronage and corporate welfare, have sometimes cost more than they gained, have incurred financial risk to the government, and have been unfair to businesses already in the state, which get nothing for staying.

The Lamont administration's new idea is to subsidize incoming businesses by rebating to them some of the state income taxes paid by their employees. This would incur little financial risk and expense to the state.

But this system still wouldn't be fair, for unless the line of business of the new company was unique in the state, state government still would be subsidizing the new company against its in-state competitors.

Last week, the Yankee Institute offered a better and perfectly fair idea: Eliminate grants, loans and tax credits to new businesses and simply repeal Connecticut's corporation business tax.

The Yankee Institute suggests that the tax's annual revenue to state government, averaging $834 million per year, isn't so much, only about 5 percent of the state's general-receipts.

This analysis underestimates the problem, since state government never can bring itself to reduce spending at all. But to make Connecticut much more attractive to business, it would not be necessary to repeal the whole corporation business tax. Repealing even half of it would send a remarkable signal around the country.

Of course, state government is always enacting tax cuts for the future and then repealing them when the future arrives. So to be believed, a corporation business tax cut would have to offer a contract to every business in the state and every arriving business guaranteeing that its tax would not be raised for, say, 20 years. But a big differential between Connecticut's business taxes and those of other states really might pay for itself far better than spot subsidies.

xxx

OVERKILL ON YEARBOOK: Pranking high school yearbooks is a tradition almost as old as the yearbooks themselves. What would any high school yearbook be without a defaced photograph or gross caption?

But police in Glastonbury, Conn., are treating the recent yearbook pranking there as a felony, having charged the suspect, an 18-year-old student, with two counts of third-degree computer crime, each count punishable by as much as five years in prison.

That makes the offense sound like terrorism.

Meanwhile, young people with 10 or more arrests, many of them on serious charges like assault, robbery and car theft, are being released by Connecticut's juvenile court system without any punishment at all and now apparently are moving on to kill people, confident that the state lacks the self-respect to punish them for anything.

The irony here probably will turn out to be superficial, for the Glastonbury student almost surely will get similarly lenient treatment from the criminal-justice system, whose dirty little secret is that it seldom seriously punishes anyone for anything short of murder, seldom at all for a first offense.

If the offenses attributed to the student occurred before he turned 18, he may qualify for "youthful offender status," whereby a criminal case is concealed and offenders can be let off, maybe with a little social work, and no public record of their misconduct is maintained.

If the offenses occurred after he turned 18 and he is a first offender, the student can apply to the court for "accelerated rehabilitation," a probation that suspends and eventually cancels prosecution and erases the charges.

So despite his serious charges, the student won't be going to prison. But since the publicity will make the case harder to whitewash, the court might grant the student "accelerated rehabilitation" on condition of a public apology, especially since the yearbook publishing company, with spectacular generosity, has agreed to repair the yearbooks without charge.

Turnabout being fair play, the best justice here might come if the newspapers published and television stations broadcast the student's mug shot with various defacements and a gross caption to see how he likes it.

That might send him well on his way toward a career in computer hacking, politics or journalism.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Corny and then depressing

—Photo by Marek Szczepanek

“Round the point flotillas of swans come trailing

sunlit V’s and W’s, otherworldly,

But a little corny….’’

“Garbo Lobster’s fleet has been sold; Monsanto,

windows broken, whistled an absent air; New

Yorkers long since bought up the nicer houses;

God, it’s depressing….’’

--From “Neoclassical,’’ by Daniel Hall (born 1952), Amherst, Mass.-based poet

Lobstering in Portland, Maine

— Photo by Mrosen99

Llewellyn King: Has COVID launched a new age for workers?

Most workers would like to slash the time they spend commuting.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Millions of Americans appear to be echoing the words of the Johnny Paycheck song “Take This Job and Shove It.” This is a sentiment that is changing the work scene, the way we work, and the future of work.

The workers of America are shuffling the deck in a way that has never happened before. It is accentuating an acute labor shortage.

I receive lists of job openings every day and the common denominator seems to be that you must show up at a place of business. Among the big and seemingly frantic employers are FedEx, Walmart and Amazon. Warehouse workers and delivery drivers are the most sought-after employees.

To overcome the labor shortage, wages are rising and adding to the rising inflation -- although what part of that rise is labor cost isn’t clear. Other factors are pandemic-induced supply chain disruptions, a tightening of food flows from California and other Western states, and the acute housing shortage. The economy is rebalancing; and so are workers, reassessing their lives and making changes.

There has been a severe shortage of skilled workers for a long time. It has been felt almost everywhere from construction to electric line workers. It is just worse now, exacerbated by immigration restrictions and workers who have joined the reshuffle.

During the COVID-19 lockdown, millions of individuals have assessed what they do and, apparently, found it wanting.

America’s workforce isn’t returning to the jobs that they held before the lockdown. Some are trying new things; others are demanding changes in the workplace. There is a demand for more remote working. The rat race is running short of willing rats.

Commuting seems to be the one big no-no. People in the major work hubs such as New York, Washington, Chicago, Boston and San Francisco have sampled the joys and the failings of working from home, and commuting has lost.

I know people who used to spend four or five hours every day getting to work and back home in all these cities. Sitting in a traffic jam is neither creative nor the best use of human life, these people are now saying.

In the movie Network, Peter Finch bellows, “I’m as mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore!” That is the new sentiment towards rigid travel and rigid work schedules. Working from home has taken people up the hill and shown them the valley, and they have liked the valley.

Other workers, particularly at the lower end of the work scale, have wondered whether they wouldn’t be happier doing something else now that they have had time to ponder. A friend of mine’s daughter who was a professional waiter in Florida now works for a printer. She has found she gets a more dependable income, better hours and that incalculable: a happier work environment.

I love small business, and I believe it to be the essential force for innovation and job creation. But it is also where petty boss-tyrants flourish. Lousy, egomaniacal employers aren't hard to find, especially in the restaurant business.

When I worked as a waiter in New York, between journalism jobs, I knew waiters who dreamed of the great restaurant where the tips are generous and, above all, the “patron is nice.” Unseen, there is a lot of cussing and pressure in any restaurant, and job security is unknown.

Enforced downtime has caused many to wonder whether they are even in the right line of work; whether the money, prestige or social recognition that may have gone with their old job was worth it.

For others, the gig economy has beckoned, where the employer has been cut out. Particularly, this is true of young people in communications and related work. Geeks are a hot item and can contract directly. But others, from landscape gardeners to plumbers, are going gig. The downside is there are no benefits, from Social Security deductions to pensions and health care. Society is lagging in recognizing this new arena of work.

Peculiarly, we aren’t at full employment. Unemployment is hovering around 5.9 percent and has gone up slightly as the summer has progressed. This raises the question of how many of the formerly employed are now in the gig economy, skewing the figures.

We are in what is, in effect, a post-war recovery. Traditionally, that is a time for social readjustment, for old bonds to be loosed, and for new energy to be released. Is it time to sack the boss?

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Web site: whchronicle.com

David Warsh: Of The Globe, John Kerry, Vietnam and my column

An advertisement for The Boston Globe from 1896.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It has taken six months, but with this edition, Economic Principals finally makes good on its previously announced intention to move to Substack publishing. What took so long? I can’t blame the pandemic. Better to say it’s complicated. (Substack is an online platform that provides publishing, payment, analytics and design infrastructure to support subscription newsletters.)

EP originated in 1983 as columns in the business section of The Boston Sunday Globe. It appeared there for 18 years, winning a Loeb award in the process. (I had won another Loeb a few years before, at Forbes.) The logic of EP was simple: It zeroed in on economics because Boston was the world capital of the discipline; it emphasized personalities because otherwise the subject was intrinsically dry (hence the punning name). A Tuesday column was soon added, dwelling more on politics, because economic and politics were essentially inseparable in my view.

The New York Times Co. bought The Globe in 1993, for $1.13 billion, took control of it in 1999 after a standstill agreement expired, and, in July 2001, installed a new editor, Martin Baron. On his second morning on the job, Baron instructed the business editor, Peter Mancusi, that EP was no longer permitted to write about politics. I didn’t understand, but tried to comply. I failed to meet expectations, and in January, Baron killed the column. It was clearly within his rights. Metro columnist Mike Barnicle had been cancelled, publisher Benjamin Taylor had been replaced, and editor Matthew Storin, privately maligned for having knuckled under too often to the Boston archdiocese of the Roman Catholic Church, retired. I was small potatoes, but there was something about The Globe’s culture that the NYT Co. didn’t like. I quit the paper and six weeks later moved the column online.

After experimenting with various approaches for a couple of years, I settled on a business model that resembled public radio in the United States – a relative handful of civic-minded subscribers supporting a service otherwise available for free to anyone interested. An annual $50 subscription brought an early (bulldog) edition of the weekly via email on Saturday night. Late Sunday afternoon, the column went up on the Web, where it (and its archive) have been ever since, available to all comers for free.

Only slowly did it occur to me that perhaps I had been obtuse about those “no politics” instructions. In October 1996, five years before they were given, I had raised caustic questions about the encounter for which then U.S. Sen. John Kerry (D.-Mass.) had received a Silver Star in Vietnam 25 years before. Kerry was then running for re-election, I began to suspect that history had something to do with Baron ordering me to steer clear of politics in 2001.

• ••

John Kerry had become well known in the early ‘70s as a decorated Navy war hero who had turned against the Vietnam War. I’d covered the war for two years, 1968-70, traveling widely, first as an enlisted correspondent for Pacific Stars and Stripes, then as a Saigon bureau stringer for Newsweek. I was critical of the premises the war was based on, but not as disparaging of its conduct as was Kerry. I first heard him talk in the autumn of 1970, a few months after he had unsuccessfully challenged the anti-war candidate Rev. Robert Drinan, then the dean of Boston College Law School, for the right to run against the hawkish Philip Philbin in the Democratic primary. Drinan won the nomination and the November election. He was re-elected four times.

As a Navy veteran, I was put off by what I took to be the vainglorious aspects of Kerry’s successive public statements and candidacies, especially in the spring of 1971, when in testimony before the Senate Foreign Relation Committee, he repeated accusations he had made on Meet the Press that thousands of atrocities amounting to war crimes had been committed by U.S. forces in Vietnam. The next day he joined other members of the Vietnam Veterans against the War in throwing medals (but not his own) over a fence at the Pentagon.

In 1972, he tested the waters in three different congressional districts in Massachusetts before deciding to run in one, an election that he lost. He later gained electoral successes in the Bay State, winning the lieutenant governorship on the Michael Dukakis ticket in 1982, and a U.S. Senate seat in 1984, succeeding Paul Tsongas, who had resigned for health reasons. Kerry remained in the Senate until 2013, when he resigned to become secretary of state. [Correction added]

Twenty-five years after his Senate testimony, as a columnist I more than once expressed enthusiasm for the possibility that a liberal Republican – venture capitalist Mitt Romney or Gov. Bill Weld – might defeat Kerry in the 1996 Senate election. (Weld had been a college classmate, though I had not known him.) This was hardly disinterested newspapering, but as a columnist, part of my job was to express opinions.

In the autumn of 1996, the recently re-elected Weld had challenged Kerry’s bid for a third term in the Senate, The campaign brought old memories to life. On Sunday Oct. 6, The Globe published long side-by-side profiles of the candidates, extensively reported by Charles Sennott.

The Kerry story began with an elaborate account of his experiences in Vietnam – the candidate’s first attempt. I believe, since 1971 to tell the story of his war. After Kerry boasted of his service during a debate 10 days later, I became curious about the relatively short time he had spent in Vietnam – four months. I began to research a column. Kerry’s campaign staff put me in touch with Tom Belodeau, a bow gunner on the patrol boat that Kerry had beached after a rocket was fired at it to begin the encounter for which he was recognized with a Silver Star.

Our conversation lasted half an hour. At one point, Belodeau confided, “You know, I shot that guy.” That evening I noticed that the bow gunner played no part in Kerry’s account of the encounter in a New Yorker article by James Carroll in October 1996 – an account that seemed to contradict the medal citation itself. That led me to notice the citation’s unusual language: “[A]n enemy soldier sprang from his position not 10 feet [from the boat] and fled. Without hesitation, Lieutenant (Junior Grade) Kerry leaped ashore, pursued the man behind a hootch and killed him, capturing a B-40 rocket launcher with a round in the chamber.” There are now multiple accounts of what happened that day. Only one of them, the citation, is official, and even it seems to exist in several versions. What is striking is that with the reference to the hootch, the anonymous author uncharacteristically seems to take pains to imply that nobody saw what happened.

The first column (“The War Hero”) ran Tues., Oct. 24. Around that time, a fellow former Swift Boat commander, Edward (Tedd) Ladd, phoned The Globe’s Sennott to offer further details and was immediately passed on to me. Belodeau, a Massachusetts native who was living in Michigan, wanted to avoid further inquiries, I was told. I asked the campaign for an interview with Kerry. His staff promised one, but day after day, failed to deliver. Friday evening arrived and I was left with the draft of column for Sunday Oct. 27 about the citation’s unusual phrase (“Behind the Hootch”). It included a question that eventually came to be seen among friends as an inside joke aimed at other Vietnam vets (including a dear friend who sat five feet away in the newsroom): Had Kerry himself committed a war crime, at least under the terms of his own sweeping indictments of 1971, by dispatching a wounded man behind a structure where what happened couldn’t be seen?

The joke fell flat. War crime? A bad choice of words! The headline? Even worse. Due to the lack of the campaign’s promised response, the column was woolly and wholly devoid of significant new information. It certainly wasn’t the serious accusation that Kerry indignantly denied. Well before the Sunday paper appeared, Kerry’s staff apparently knew what it would say. They organized a Sunday press conference at the Boston Navy Yard, which was attended by various former crew members and the admiral who had presented his medal. There the candidate vigorously defended his conduct and attacked my coverage, especially the implicit wisecrack the second column contained. I didn’t learn about the rally until late that afternoon, when a Globe reporter called me for comment.

I was widely condemned. Fair enough: this was politics, after all, not beanbag. (Caught in the middle, Globe editor Storin played fair throughout with both the campaign and me). The election, less than three weeks away, had been refocused. Kerry won by a wider margin than he might have otherwise. (Kerry’s own version of the events of that week can be found on pp. 223-225 of his autobiography.)

• ••

Without knowing it, I had become, in effect, a charter member of the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth. That was the name of a political organization that surfaced in May 2004 to criticize Kerry, in television advertisements, on the Web, and in a book, Unfit for Command. What I had discovered in 1996 was little more than what everyone learned in 2004 – that some of his fellow sailors disliked Kerry intensely. In conversations with many Swift Boat vets over the year or two after the columns, I learned that many bones of contention existed. But the book about the recent history of economics I was finishing and the online edition of EP that kept me in business were far more important. I was no longer a card-carrying member of a major news organization, so after leaving The Globe I gave the slowly developing Swift Boat story a good leaving alone. I spent the first half of 2004 at the American Academy in Berlin.

Whatever his venial sins, Kerry redeemed himself thoroughly, it seems to me, by declining to contest the result of the 2004 election, after the vote went against him by a narrow margin of 118,601 votes in Ohio. He served as secretary of state for four years in the Obama administration and was named special presidential envoy for climate change, a Cabinet-level position, by President Biden,

Baron organized The Globe’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Spotlight coverage of Catholic Church secrecy about sexual abuse by priests, and it turned into a world story and a Hollywood film. In 2013 he became editor of The Washington Post and steered a steady course as Amazon founder Jeff Bezos acquired the paper from the Graham family and Donald Trump won the presidency and then lost it. Baron retired in February. He is writing a book about those years.

But in 2003, John F. Kerry: The Complete Biography by the Boston Globe Reporters Who Know Him Best was published by PublicAffairs Books, a well-respected publishing house whose founder, Peter Osnos, had himself been a Vietnam correspondent for The Washington Post. Baron, The Globe’s editor, wrote in a preface, “We determined… that The Boston Globe should be the point of reference for anyone seeking to know John Kerry. No one should discover material about him that we hadn’t identified and vetted first.”

All three authors – Michael Kranish, Brian Mooney, Nina Easton – were skilled newspaper reporters. Their propensity to careful work appears on (nearly) every page. Mooney and Kranish I considered I knew well. But the latter, who was assigned to cover Kerry’s early years, his upbringing, and his combat in Vietnam, never spoke to me in the course of his reporting. The 1996 campaign episode in which I was involved is described in three paragraphs on page 322. The New Yorker profile by James Carroll that prompted my second column isn’t mentioned anywhere in the book; and where the Silver Star citation is quoted (page 104), the phrase that attracted my attention, “behind the hootch,” is replaced by an ellipsis. (An after-action report containing the phrase is quoted on page 102.)

Nor did Baron and I ever speak of the matter. What might he have known about it? He had been appointed night editor of The Times in 1997, last-minute assessor of news not yet fit to print; I don’t know whether he was already serving in that capacity in October 1996, when my Globe columns became part of the Senate election story. I do know he commissioned the project that became the Globe biography in December, 2001, a few weeks before terminating EP.

Kranish today is a national political investigative reporter for The Washington Post. Should I have asked him about his Globe reporting, which seems to me lacking in context? I think not. (I let him know this piece was coming; I hope that eventually we’ll talk privately someday.) But my subject here is how The Globe’s culture changed after NYT Co. acquired the paper, so I believe his incuriosity and that of his editor are facts that speak for themselves.

Baron’s claims of authority in his preface to The Complete Biography by the Boston Globe Reporters Who Know Him Best strike me as having been deliberately dishonest, a calculated attempt to forestall further scrutiny of Kerry’s time in Vietnam. In this Baron’s book failed. It is a far more careful and even-handed account than Tour of Duty: John Kerry and the Vietnam War (Morrow, 2004), historian Douglas Brinkley’s campaign biography. Mooney’s sections on Kerry’s years in Massachusetts politics are especially good. But as the sudden re-appearance of the Vietnam controversy in 2004 demonstrated, The Globe’s account left much on the table.

• ••

I mention these events now for two reasons. The first is that the Substack publishing platform has created a path that did not exist before to an audience – in this case several audiences – concerned with issues about which I have considerable expertise. The first EP readers were drawn from those who had followed the column in The Globe. Some have fallen away; others have joined. A reliable 300 or so annual Bulldog subscriptions have kept EP afloat.

Today, with a thousand online columns and two books behind me – Knowledge and the Wealth of Nations: A Story of Economic Discovery (Norton, 2006) and Because They Could: The Harvard Russia Scandal (and NATO Expansion) after Twenty-Five Years (CreateSpace, 2018) – and a third book on the way, my reputation as an economic journalist is better-established.

The issues I discuss here today have to do with aspirations to disinterested reporting and open-mindedness in the newspapers I read, and, in some cases, the failure to achieve those lofty goals. I have felt deeply for 25 years about the particular matters described here; I was occasionally tempted to pipe up about them. Until now, the reward of regaining my former life as a newsman by re-entering the discussion never seemed worth the price I expected to pay.

But the success of Substack says to writers like me, “Put up or shut up.” After the challenge it posed dawned in December, I perked up, then hesitated for several months before deciding to leave my comfortable backwater for a lively and growing ecosystem. Newsletter publishing now has certain features in common with the market for national magazines that emerged in the U.S. in the second half of the 19th Century – a mezzanine tier of journalism in which authors compete for readers’ attention. In this case, subscribers participate directly in deciding what will become news.

The other reason has to do with arguments recently spelled out with clarity and subtlety by Jonathan Rauch in The Constitution of Knowledge: A Defense of Truth (Brookings, 2021). Rauch gets the Swift Boat controversy mostly wrong, mixing up his own understanding of it with its interpretation by Donald Trump, but he is absolutely correct about the responsibility of the truth disciplines – science, law, history and journalism – to carefully sort out even the most complicated claims and counter-claims that endlessly strike sparks in the digital media.

Without the places where professionals like experts and editors and peer reviewers organize conversations and compare propositions and assess competence and provide accountability – everywhere from scientific journals to Wikipedia pages – there is no marketplace of ideas; there are only cults warring and splintering and individuals running around making noise.

EP exists mainly to cover economics. This edition has been an uncharacteristically long (re)introduction. My interest in these long-ago matters is strongly felt, but it is a distinctly secondary concern. I expect to return to these topics occasionally, on the order of once a month, until whatever I have left to say has been said: a matter of ten or twelve columns, I imagine, such as I might have written for the Taylor family’s Globe.

As a Stripes correspondent, I knew something about the American war in Vietnam in the late Sixties. As an experienced newspaperman who had been sidelined, I was alert to issues that developed as Kerry mounted his presidential campaign. And as an economic journalist, I became interested in policy-making during the first decade of the 21st Century, especially decisions leading up to the global financial crisis of 2008 and its aftermath. Comments on the weekly bulldogs are disabled. Threads on the Substack site associated with each new column are for bulldog subscriber only. As best I can tell, that page has not begun working yet. I will pay close attention and play comments there by ear.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

And then go back to bed

“Rise’’ (oil on canvas), by Alexis Serio, at Edgewater Gallery at the Falls, Middlebury, Vt.

The gallery says:

“Serio creates ethereal, abstract landscapes. Through her color choices, and layering of tones and simplified shapes the artist’s compositions become vast and dreamlike. They glow with shifting light and a sense of place. Serio’s work strives to evoke remembrance of something familiar for the viewer. Billowing skies meet rolling planes of landscape in this beautiful new series.’’

Calm down, old boy!

The north-central Pioneer Valley in South Deerfield, Mass.

— Photo by Tom Walsh

“Massachusetts! A word surrounded with an aura of hope! A state with a soul! There is gathered up into her name the brilliant program of a new world.’’

— Wallace Nutting, in Massachusetts Beautiful (1923)

Built in 1681, the Old Ship Church, in Hingham, Mass., is the oldest church in America in continuous ecclesiastical use. Massachusetts has since become one of the most irreligious states in the U.S. It was built by Puritans, then was Congregational and now is Unitarian-Universalist.

Be nice to them

The kitchen at Delmonico's Restaurant, New York City, in 1902. It was probably America’s most famous restaurant at the time.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I walk in Wayland Square, on the East Side of Providence, almost daily. It’s now dominated by a wide variety of restaurants, some of them very good. While such neighborhoods used to have more shops than restaurants, now it’s the other way around, as the Internet and other ambiguous forces take away retail business, especially clothing sales. Consider such big pharmacy chains as CVS, whose Wayland Square store, for example, sells a far wider variety of stuff (including underwear, socks and such fast food as plastic-wrapped sandwiches!) than did most drugstores a half century ago. But bring back the soda fountains!

The exit of some of the charming small shops in places like Wayland Square and Providence’s Harvard Square – Thayer Street –and their replacement by restaurants is sad, even as people are happily eating out more and more in those neighborhoods.

They like to sample food that they feel might be too complicated to prepare at home, they like being served and not having to clean up and they like the psychological ease of meeting people in a place without the complications of being a host or a guest. For one thing, it’s much easier/crisper to end an evening in a restaurant than in someone’s home.

Many people of very modest means spend a fiscally dangerous percentage of their income eating in restaurants. Indeed, it’s so pleasant and easy that many do it several times a week.

But the congenial experience requires what is often exhausting work by restaurant staffs, who must also all too often deal with arrogant, obnoxious people. It’s enlightened self-interest to be nice to restaurant workers. Don’t drive them away even as the tentative retreat of COVID-19 reopens so many understaffed restaurants to indoor service.