One-man sculpture park in Vermont

David Stromeyer and his wife, Sarah, during the installation of “Body Politic,’’ last year. For 50 years the celebrated artist has been installing his monumental steel sculptures on his 45-acre domain in Enosburg, Vt., which he named Cold Hollow Sculpture Park.

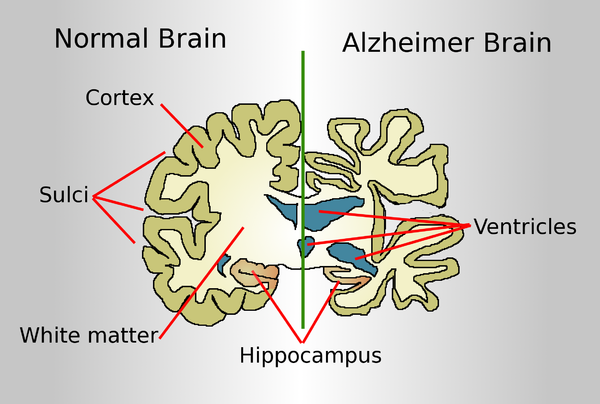

Elisabeth Rosenthal: Why we may never know if Biogen’s Alzheimer’s drug works

A normal brain on the left and a late-stage Alzheimer's brain on the right.

The Food and Drug Administration’s approval in June of a drug purporting to slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease was widely celebrated, but it also touched off alarms. There were worries in the scientific community about the drug, developed by Cambridge, Mass.-based Biogen, mixed results in studies — the FDA’s own expert advisory panel was nearly unanimous in opposing its approval. And the annual $56,000 price tag of the infusion drug, Aduhelm, was decried for potentially adding costs in the tens of billions of dollars to Medicare and Medicaid.

But lost in this discussion is the underlying problem with using the FDA’s “accelerated” pathway to approve drugs for conditions such as Alzheimer’s, a slow, degenerative disease. Though patients will start taking it, if the past is any guide, the world may have to wait many years to find out whether Aduhelm is actually effective — and may never know for sure.

The accelerated approval process, begun in 1992, is an outgrowth of the HIV/AIDS crisis. The process was designed to approve for sale — temporarily — drugs that studies had shown might be promising but that had not yet met the agency’s gold standard of “safe and effective,” in situations where the drug offered potential benefit and where there was no other option.

Unfortunately, the process has too often amounted to a commercial end run around the agency.

The FDA explained its controversial decision to greenlight the Biogen pharmaceutical company’s latest product: Families are desperate, and there is no other Alzheimer’s treatment. Also, importantly, when drugs receive this type of fast-track approval, manufacturers are required to do further controlled studies “to verify the drug’s clinical benefit.” If those studies fail “to verify clinical benefit, the FDA may” — may — withdraw them.

But those subsequent studies have often taken years to complete, if they are finished at all. That’s in part because of the FDA’s notoriously lax follow-up and in part because drugmakers tend to drag their feet. When the drug is in use and profits are good, why would a manufacturer want to find out that a lucrative blockbuster is a failure?

Historically, so far, most of the new drugs that have received accelerated approval treat serious malignancies.

And follow-up studies are far easier to complete when the disease is cancer, not a neurodegenerative disease such as Alzheimer’s. In cancer, “no benefit” means tumor progression and death. The mental decline of Alzheimer’s often takes years and is much harder to measure. So years, possibly decades, later, Aduhelm studies might not yield a clear answer, even if Biogen manages to enroll a significant number of patients in follow-up trials.

Now that Aduhelm is shipping into the marketplace, enrollment in the required follow-up trials is likely to be difficult, if not impossible. If your loved one has Alzheimer’s, with its relentless diminution of mental function, you would want the drug treatment to start right now. How likely would you be to enroll and risk placement in a placebo group?

The FDA gave Biogen nine years for follow-up studies but acknowledged that the timeline was “conservative.”

Even when the required additional studies are performed, the FDA historically has been slow to respond to disappointing results.

In a 2015 study of 36 cancer drugs approved by the FDA, only five ultimately showed evidence of extending life. But making that determination took more than four years, and over that time the drugs had been sold, at a handsome profit, to treat countless patients. Few drugs are removed.

It took 17 years after initial approval via the accelerated process for Mylotarg, a drug to treat a form of leukemia, to be removed from the market after subsequent trials failed to show clinical benefit and suggested possible harm. (The FDA permitted the drug to be sold at a lower dose, with less toxicity.)

Avastin received fast-track approval as a breast cancer treatment in 2008, but three years later the FDA revoked the approval after studies showed the drug did more harm than good in that use. (It is still approved for other, generally less common cancers.)

In April, the FDA said it would be a better policeman of cancer drugs that had come to markets via accelerated approval. But time — as in delays — means money to drug manufacturers.

A few years ago, when I was writing a book about the business of U.S. medicine, a consultant who had worked with pharmaceutical companies on marketing drug treatments for hemophilia told me the industry referred to that serious bleeding disorder as a “high-value disease state,” since the medicines to treat it can top $1 million a year for a single patient.

Aduhelm, at $56,000 a year, is a relative bargain — but hemophilia is a rare disease, and Alzheimer’s is terrifyingly common. Drugs to combat it will be sold and taken. The crucial studies that will define their true benefit will take many years or may never be successfully completed. And from a business perspective, that doesn’t really matter.

Elisabeth Rosenthal, M.D., is editor of Kaiser Health News.

Seeing the show in Boston

Brother Jonathan, in the 19th Century a visual personification of New England

To get betimes in Boston town I rose this morning early,

Here's a good place at the corner, I must stand and see the show.

Clear the way there Jonathan!

Way for the President's marshal--way for the government cannon!

Way for the Federal foot and dragoons, (and the apparitions

copiously tumbling.)

I love to look on the Stars and Stripes, I hope the fifes will play

Yankee Doodle.

How bright shine the cutlasses of the foremost troops!

Every man holds his revolver, marching stiff through Boston town.

A fog follows, antiques of the same come limping,

Some appear wooden-legged, and some appear bandaged and bloodless.

Why this is indeed a show--it has called the dead out of the earth!

The old graveyards of the hills have hurried to see!

Phantoms! phantoms countless by flank and rear!

Cock'd hats of mothy mould--crutches made of mist!

Arms in slings--old men leaning on young men's shoulders.

What troubles you Yankee phantoms? what is all this chattering of

bare gums?

Does the ague convulse your limbs? do you mistake your crutches for

firelocks and level them?

If you blind your eyes with tears you will not see the President's marshal,

If you groan such groans you might balk the government cannon.

For shame old maniacs--bring down those toss'd arms, and let your

white hair be,

Here gape your great grandsons, their wives gaze at them from the windows,

See how well dress'd, see how orderly they conduct themselves.

Worse and worse--can't you stand it? are you retreating?

Is this hour with the living too dead for you

Retreat then--pell-mell!

To your graves--back--back to the hills old limpers!

I do not think you belong here anyhow.

But there is one thing that belongs here--shall I tell you what it

is, gentlemen of Boston?

I will whisper it to the Mayor, he shall send a committee to England,

They shall get a grant from the Parliament, go with a cart to the

royal vault,

Dig out King George's coffin, unwrap him quick from the

graveclothes, box up his bones for a journey,

Find a swift Yankee clipper--here is freight for you, black-bellied clipper,

Up with your anchor--shake out your sails--steer straight toward

Boston bay.

Now call for the President's marshal again, bring out the government cannon,

Fetch home the roarers from Congress, make another procession,

guard it with foot and dragoons.

This centre-piece for them;

Look, all orderly citizens--look from the windows, women!

The committee open the box, set up the regal ribs, glue those that

will not stay,

Clap the skull on top of the ribs, and clap a crown on top of the skull.

You have got your revenge, old buster--the crown is come to its own,

and more than its own.

Stick your hands in your pockets, Jonathan--you are a made man from

this day,

You are mighty cute--and here is one of your bargains.

“A Boston Ballad’’ (1854), by Walt Whitcomb (1819-1892)

An intimate moment

“You Are My Refuge” (watercolor, collage, ink, paper), by Pauline Lim, in the show “The Great Outdoors, ‘‘ at the Brickbottom Artists Association, Somerville, Mass., July 15-Aug. 14.

The gallery says:

“The past year has shown us how great ‘The Great Outdoors’ really is! The visual interest, the psychological and emotional connection, the freedom and also the safety it allowed. In this group exhibition, BAA members examine and interpret the outdoors from every angle: landscapes (natural and built), sea, sky, earth, weather... Perspective is everything; even a window box or a bird feeder are ‘the great outdoors’ to a cat sitting at a closed window.’’

Philip K. Howard: Of obsolete laws and the filibuster

Anything positive that comes out of Congress is big news, as with the recent bipartisan support for a $1 trillion infrastructure package. But that’s only half the job: Congress must also fix the delivery system that delays permitting and guarantees wasteful procurement. For example, building a resilient, interconnected power grid — probably the top environmental priority—is basically impossible in a legal labyrinth that gives any naysayer multiple ways to delay, and then to delay some more.

Congress has responsibility not only for enacting new laws, but for making sure old laws work sensibly. But Congress rarely fixes old laws. Congressional oversight consists of posturing at public hearings, not corrective legislation. Congress has effectively abdicated the oversight job to the executive branch and federal courts, which have inadequate authority to make needed legal repairs. The ship of state, weighed down by a century of statutory barnacles, plows slowly in the same direction year after year.

No statutory program works as it should. Infrastructure permitting can take a decade. Health care is a tangle of red tape, consuming upwards of 30 percent of total cost; that’s $1 million per doctor. In about half the states, teachers are outnumbered by noninstructional personnel, many focused on legal compliance. Accountability of public employees is nonexistent; 99 percent of federal employees receive a “fully successful” rating. Obsolete laws notoriously distort resources; the 1920 Jones Act, for example, makes it more expensive to build offshore wind turbines because of its requirement to use U.S.-built ships.

Washington is overdue for a spring cleaning. Only Congress has the authority to do this. But neither party has a vision about how, or even whether, to fix broken government. Congressional leaders are so dug in arguing about the goals of government that they have no line of sight to how laws actually work.

The partisan myopia is revealed by the current debate over whether to retain the Senate filibuster rule. Making it hard to enact new laws, supporters of a supermajority vote argue, encourages more deliberative new programs. Eliminating the rule, on the other hand, will allow narrow Democratic majorities to enact sweeping new progressive programs. These arguments pro and con presume that lawmaking is an additive process — that Congress’s main responsibility is to enact new programs.

Fixing old programs, however, also requires lawmaking. Should Senate rules discourage repairing existing programs? Conservative scholar F.H. Buckley argues for abolishing the supermajority entirely, even though that would mean more liberal programs in the Biden administration, because making it easier to repeal or fix broken laws would be far more impactful.

Debate over the filibuster provides an opportunity to rethink how Congress does its job. The constitutional separation of powers is designed to make it hard to enact new programs. But the Framers also knew that it was important to purge old laws. James Madison believed that “the infirmities most besetting Popular Governments…are found to be defective laws which do mischief before they can be mended, and laws passed under transient impulses, of which time & reflection call for a change.”

But the Framers did not focus on the fact that, once enacted, a program will be defended by an army of interest groups. That’s why It is more difficult to repeal or amend a law than to enact a new one. The determined defense of an obsolete program by a special interest, as economist Mancur Olson explained, will always trump the general interest of the common good. That’s why farm subsidies continue 80 years after the Great Depression ended.

All laws have unintended consequences. Circumstances change. Priorities need to be reset to meet current challenges. Agencies deviate from their congressional mandate. Clear lines of authority must be clarified to give infrastructure permits on a timely basis.

Congress must come up with a practical way to fix broken and obsolete programs. One procedural change might be for the Senate to eliminate the supermajority vote for amending or repealing laws. But the backlog of broken programs is too piled up to expect much impact from one procedural change. Congress needs to go further. Here are three changes specifically aimed at fixing broken laws:

Create nonpartisan “spring cleaning commissions” to recommend updated frameworks in each area. Then, as with base-closing commissions, the proposals would be submitted for an up-or-down vote by each chamber.

Require a sunset on all laws with budgetary impact. Over the course of a decade, Congress could then methodically update the statute books.

Revive “regular order” in Congress to provide more presumptive authority to congressional committees to fix old laws. Congress could further empower committees by automatically approving amendments that are supported by both the majority and committee ranking members.

The failure of Congress to take responsibility for the actual workings of its laws is beyond serious dispute. By delegating lawmaking to agencies, and abandoning effective oversight, Congress has severed the critical link to democratic accountability. Government keeps going in the same direction, no matter how unresponsive and ineffective. Its inability to adapt to public needs in turn spawns extremist candidates. In order to restore trust in Washington, Congress must change the rules so it can take responsibility for how laws actually work.

Philip K. Howard is a lawyer, author, New York civic and cultural leader and chairman of Common Good, a legal and regulatory reform organization that emphasizes the importance of taking institutional, political and personal responsibility. His Latest Book is Try Common Sense. This essay first ran in The Hill.

Frank Carini: In two areas on R.I. coast — improvement and new challenges

The Nature Conservancy and its partners installed a living shoreline at Rose Larisa Memorial Park, in East Providence, to help keep coastal erosion at bay.

— Photo by Frank Carini/ecoRI News)

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

EAST PROVIDENCE, R.I.

Growing up in the 1970s and ’80s across the Seekonk and Providence rivers in Rhode Island’s capital, John Torgan spent plenty of time exploring the state’s urban shoreline.

He remembers them as dumps filled with sewage and littered with decaying oil tanks.

“They were horribly polluted,” said Torgan, who still lives in Providence. “No one was fishing or sailing.”

His childhood memories, however, also include the beauty of a peaceful island in the middle of a shallow 4-mile-long salt pond.

The fortunes of these waters and their surroundings have changed since an adolescent Torgan, now 51, was skipping rocks, collecting shells and investigating the coastline for marine life. The Providence and Seekonk rivers are still impaired waters, but, like the chain-link fence topped with barbed wire that once separated much of these waterways from the public, the derelict oil tanks have been removed. The rivers’ health has improved.

The two rivers, both of which share a legacy of industrial contamination and suffer from stormwater-runoff pollution, aren’t recommended for swimming, but life on, under and around them has returned. Menhaden, bluefish, river herring, eels, osprey and cormorants are now routinely spotted. The occasional seal, dolphin, bald eagle and trophy-sized striped bass visit. Kayakers, fishermen, scullers and birdwatchers are easy to find.

Torgan, who spent 18 years as Save The Bay’s baykeeper, called the comeback of upper Narragansett Bay “extraordinary” and “dramatic.” He credited the Narragansett Bay Commission’s ongoing combined sewer overflow project with making the recovery possible.

As for that summer cottage on Great Island in Point Judith Pond, he said “tremendous development” has changed the neighborhood. Bigger houses now surround the Torgan family’s saltbox cottage, adding stress to one of Rhode Island’s largest and most heavily used salt ponds.

There is a diverse mixture of development around the shores of the pond that straddles South Kingstown and Narragansett. In the urban center of Wakefield, at the head of the pond, and at the port of Galilee at its mouth, there is an abundance of commercial development and a corresponding amount of pavement. The impacts are beginning to show.

Early last year the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management decided, based on ongoing water-quality monitoring results, to reclassify two areas of Point Judith Pond from approved to conditionally approved for shellfish harvesting. Water samples collected in the pond after certain rain events showed elevated bacteria levels and resulted in several emergency and precautionary shellfishing closures.

An underappreciated coastline

As an adult, Torgan’s interest in and passion about the marine environment hasn’t waned. The avid boater and angler has spent much of his working life protecting the Ocean State’s namesake, especially the waters not typically associated with its catchy moniker.

“This is the coast,” Torgan said while standing at the water’s edge at Rose Larisa Memorial Park. “The coast of Rhode Island doesn’t start at Rocky Point. It’s not just the beaches of South County.”

But, like most of the state’s coastline, the East Providence shoreline is vulnerable to accelerated erosion driven by the climate crisis and growing development pressures. Like much of the state’s urban shoreline, the health of this stretch of beach is better but hardly pristine. It is littered with chunks of asphalt and broken glass, most of its sharp edges dulled by tumbling in the sea. Swimming isn’t advised.

The climate challenges and improved health are why the organization Torgan currently heads, the Rhode Island chapter of The Nature Conservancy, took an interest in protecting this underappreciated stretch of beach.

More frequent and intense storms, combined with increasing sea-level rise, are eroding beaches and bluffs and damaging the state’s diminishing collection of coastal wetlands. Torgan said dealing with the negative impacts of this reality, plus increased flooding, is a huge challenge for Rhode Island’s 21 coastal communities. He noted adequately supported coastal resiliency projects that use nature are needed to inoculate the state against the changes that are coming.

To that end, The Nature Conservancy partnered with the Coastal Resources Management Council (CRMC) and the City of East Providence last year to test the effectiveness of “living shoreline” erosion controls at the popular Bullocks Point Avenue park.

The park’s steep coastal bluff rises 20-30 feet above a narrow beach. In several areas, however, erosion has crumbled sections of the bluff, exposed root balls and felled trees. Previous efforts to reduce erosion through human-made practices, such as the installation of riprap and seawalls, failed.

As its name suggests, the living shoreline model incorporated more natural infrastructure. Unlike concrete or stone seawalls, living shorelines are designed to prevent erosion while also providing wildlife habitat. Hardened shorelines, compared to living ones, also diminish public access.

The first step in returning nature to a prominent role at this coastal park, at the head of Narragansett Bay’s tidal waters, was removing debris, such as large concrete slabs more than 20 feet long that were sitting at the bottom of the bluff, left behind by those failed human attempts to keep Mother Nature at bay.

Then, at the northern end of the park, the bank was cut away to reduce the slope. Stone was placed at the base of the bluff and logs made of coconut fiber were installed farther up the slope. The bluff was planted with native coastal vegetation. Near the southern boundary, low piles of purposely placed rocks and rows of beachgrass and native plants were added.

In other areas along this stretch of upper Narragansett Bay beach, boulders, cement walls and wooden structures, to varying degrees of success, strain to keep East Providence backyards from eroding and the bay from encroaching.

“As a matter of policy, we need to change our relationship with water where we’re not trying to hold it back and keep it out,” Torgan said. “In a more comprehensive way, think about how can we manage it and create basins where we are welcoming the water. That will help with flooding. It will help with sea-level rise and storm damage. It will improve water quality. The long view is changing the mindset that says we need to wall off the rising water and instead think about natural approaches and strategies that allows us to move with it.”

He noted that while living shoreline techniques have been implemented elsewhere in the United States, few have been permitted, built and evaluated in New England. He said small-scale projects like this one give coastal engineers and coastal permitting agencies a better sense of their cost and effectiveness, most notably in areas that aren’t exposed to open-ocean shoreline, like along much of the South Coast, where these artificial marshes would likely be unable to blunt stronger wave action.

When the 2020 project was announced, CRMC board chair Jennifer Cervenka said, “Much of Rhode Island’s coastline is eroding, and it’s a problem with no easy fix. This nature-based erosion control is one of the first of its kind in Rhode Island, and New England. We can’t stop erosion completely, but living shoreline infrastructure like this might buy our shores some valuable time.”

The project, which cost about $230,000, was funded by a Coastal Resilience Fund grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, The Nature Conservancy, the Newport-based foundation 11th Hour Racing and the Rhode Island Coastal and Estuarine Habitat Restoration Trust Fund.

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI News.

But no maps to get there

“Doldrum III” (painted paper, thread and wood nails on wood panel), by Tegan Brozna Roberts, in the group show “Sense of Place’’ at Heather Gaudio Fine Art, New Canaan, Conn. opening Aug. 14.

The gallery says:

“Memory, geography and cultural experiences are underlying themes explored by these women artists. Through an innovative use of paper, maps, threads, collage and video projections, the artists create two and three dimensional objects that express universal notions of belonging and association.’

Llewellyn King: The Internet — where lies tangle with truth

“The Internet Messenger,” by Buky Schwartz, in Holon, Israel

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

In this, the Information Age, truth was supposed to be the great product of the times. Spread at the speed of light, and majestically transparent, the world of irrefutable truth was supposed to be available at the click of a key.

The Internet was to be like “Guinness World Records,” conceived by Sir Hugh Beaver, managing director of the Guinness Brewery, when he missed a shot while bird hunting in Ireland in 1951. This resulted in an argument between him and his hosts about the fastest game bird in Europe, the golden plover (which he missed) or the red grouse. The idea for a reference book that would settle that sort of thing was born, which could help promote Guinness and settle barroom disputes.

The first edition was published as “The Guinness Book of Records” in 1955 and was an instant bestseller. You might have thought that there was a thirst for truth as well as beer.

Despite the U.S. Supreme Court’s (dominated by Republican justices) repeated rejection of any suggestion that the presidential election of 2020 was fraudulent and that it wasn’t won by Joe Biden, the Republican governor of Texas, Greg Abbott, has called a rare special session of the Texas legislature to pass a restrictive voting package that will likely include the power for the legislature to overturn any election result it deems fraudulent.

This is happening across Republican-controlled states. They are ready to fix something big that isn’t broken.

Abbott has called the special session because the Texas legislature -- thanks to the Democrats denying him quorum in a parliamentary procedure -- didn’t get what amounts to a rollback of democracy in the regular session. Second time lucky.

What these Republicans are doing is equivalent to forcing men to wear blinders so they don’t stare at naked women on our streets, even though there are no naked women on our streets. Better be sure.

Behind all this rebuttal of truth is the Big Lie. It is promoted, cherished and burnished by Donald Trump and those who swallowed his brand of fact-free ideology. The Big Lie is with us and will cast its shadow of pernicious doubt over future elections down through time. The loser will cry fraud and state lawmakers will, under the new scheme of things, be entitled to overturn election results, violating the will of the people to serve their own political goals.

Mark Twain wrote a short essay in 1880 entitled “On the Decay of the Art of Lying.” If Twain were alive today, he might be tempted to retitle his work “The Ascent of the Art of Lying.”

The extraordinary thing about the Big Lie is its blatancy; the fact that it has been found untrue by the courts and by every investigation, yet it rolls on like the Mississippi, unyielding to fact, unimpeded by truth.

The Big Lie is an avalanche of political desire over democratic fact. It introduces corrosive doubt where there is no justification. It is a virus in the body politic that may go dormant but won’t be eradicated. The host body, democracy, is weakened and the infection can flare at any time, triggered by political ambition.

Historically, there have been primary sources of information and tertiary sources of doubt or refutation. For example, some believed that the oil companies were sitting on a gasoline substitute that would convert water to fuel. That is a falsehood that has been spread since the internal combustion engine created a need for gasoline. It was believed by a few conspiracy theorists and laughed off by most people.

When the fax machine came into being in the mid-1970s there were those who thought that the Saudi Arabian regime would fall because information about liberal society was getting into the country. Instead, Saudi conservatism hardened and there was no great liberalization. Today Saudis are online and there is no uprising, no government in exile, no large expatriate community seeking change. Truth hasn’t overwhelmed belief.

It is an awful truism that people believe what they want to believe, even if that requires the suppression of logic and the overthrow of fact. Gradually all facts become suspect, and the lie fights hand to hand with the truth.

As newspaper people joke, “Don’t let the facts stand in the way of a good story.” Democracy isn’t a good story; it is the great story of human governance. And it is being subverted by lies.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

‘No hitch in the sequence’

“The Wounded Bricklayer,’’ by Francisco de Goya (1746-1828)

“Overhead the sea blows upside down across Rhode Island.

slub clump slub clump

Charlie drops out. Carl steps in.

slub clump

No hitch in the sequence.’’

— From “The Tragedy of Bricks,’’ by Galway Kinnell (1927-2014), Pulitzer Prize-winning poet. He was a native of Providence who spent the last part of his life in Sheffield, Vt. (pop about 700).

— Photo by Artaxerxes

Look at when temps exceed 90

“Rapture’’ (oil), by Stephanie Bush, in the show “Made in Vermont,’’ at the Bryan Memorial Gallery, in Jefferson, Vt., through Sept. 6.

The show’s organizers say it “showcases the ingenuity and resourcefulness of Vermonters’’ and centers “around Vermont’s diverse landscape of farms, growing cities, breweries, industry, old and new infrastructure and more.’’

In downtown Jeffersonville’s (pop. about 800) Historic District

Donald Brown/Sherry Earle: Springfield College’s Legacy Alumni of Color

Old postcard

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

In 1966, Jimmy Ruffin sang “What Becomes of the Brokenhearted?” This song resonates with us and many of our colleagues whose hearts were broken 55 years ago at our alma mater, Springfield College …

Virtually every Black student at the college in those days felt unwelcomed. Not only was there a dearth of Black faculty, but there were also virtually no administrators of color and no support services to address the needs of the dozen Black students on campus.

This was a time when Muhammad Ali refused the military draft. The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated. John Carlos and Tommy Smith raised their fists in a Black Power salute at the 1968 Olympics. Students of color throughout the country were demonstrating for equality and fair treatment on their campuses.

These epochal events were not lost on Black students at Springfield College. In 1969, we took over the administration building and the following year occupied a dormitory. As a result, virtually all of those who participated in the dormitory takeover were suspended from the college. Brokenhearted, most of them walked away from Springfield College not to be heard from again for 50 years.

A half-century later, I observed the racial tumult of 2020 and reflected on our experience in the 1960s. For it was then that I had an idea. I would check with a few of my sisters and brothers with whom I had shared this undergraduate experience. I began making calls asking if they would reach out to others to see if there was any interest in a Zoom conference call to generally catch up on their life journeys and to ask them how they felt about today’s Springfield College. To my surprise, everyone who was called wanted to meet. I was ecstatic.

Through the process of making calls about a possible reconnect, I and others learned that while Springfield College now has more than 300 Black and Brown full-time undergraduates, these students still have issues that demand attention from the college. These are issues that have frustrated Black students dating back to the days when there were only a handful of Black students, and virtually no Brown students at all on campus. So, in March 2020, my brother and sister alumni began meeting with current leaders of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) students. We decided that to support BIPOC students and influence change at the college, we needed to create a formal group. Hence, the Legacy Alumni of Color of Springfield College was born.

Out of a burning concern to ensure a better experience for Springfield College BIPOC students, our group decided to set up five committees focused on: Mentoring, Public Safety/Student Relations, Coaching/Faculty, Day of Diversity, and Distinguished Alumni. Each committee developed a plan of action in their respective areas. Based on committee input, the Legacy Alumni, in turn, crafted an 18-page report entitled: “Legacy Alumni of Color: A Blueprint for Change” and sent it to the president of the college, Mary-Beth A. Cooper. Responses to all of our recommendations were soon forthcoming. Overwhelmingly, the Legacy Alumni were pleased with the college’s responses to our recommendations.

Listed below are just a few of the recommendations made by the Legacy Alumni of Color.

1. Increase ethnic diversity on the senior leadership team to set an example for the college.

2. Build a pipeline to develop BIPOC students for positions in administration, teaching and coaching.

A. Begin with programs for middle school and high school BIPOC students.

B. Conduct a college-sponsored summer institute to develop BIPOC candidates.

C. Continue the mentorship work begun by the Alumni Office.

D. Continue work with NCAA initiatives on diversity and inclusion.

• Have coaches review the 2020 NCAA Inclusion Summer Series and past Equity and Inclusion Forums.

• Have the college sign the Eddie Robinson Rule to ensure that departments of athletics pledge to “interview at least one, preferably, more than one, qualified racial and ethnic minority candidate” for open head coaching jobs.

• Continue participation in the NCAA Ethnic Minority and Women’s Internship program.

• Participate in upcoming NCAA programs to advance racial equity.

3. Improve recruitment of BIPOC students by increasing the diversity of staff in the Office of Undergraduate Admissions.

4. Increase staff and provide adequate funding for the Office of Multicultural Affairs in order to continue the important work of the office to create an inclusive campus, support BIPOC students and address issues of social justice.

5. Include the Office of Multicultural Affairs on tours when prospective students visit the campus.

6. Ensure that members of underrepresented groups are included on all hiring committees.

7. Hire a person of BIPOC descent in the Counseling Center.

8. Hire a person of BIPOC descent in the Office of Spiritual Life.

9. Continue to archive oral histories of BIPOC student experiences at Springfield College.

10. Strengthen ties with the off-campus community by sponsoring and hosting activities and events.

A. Support community service currently conducted by student-run organization such as Women of Power’s supply drive for the YWCA.

B. Increase ties to Springfield’s very active Black religious community.

C. Recruit BIPOC students from Springfield’s middle and high school for on-campus events.

D. Continue to send college staff to provide technical assistance to off-campus community groups.

11. Conduct an annual climate-of-life survey to learn what the experience has been for BIPOC students.

12. Require all entering students take the newly created course in ethnic studies beginning in the fall 2021.

13. Increase funding for existing student-run associations that support BIPOC students. Provide seed money to launch new student-generated associations.

A. Adequately fund the Men of Excellence program to empower men through development of leadership skill, pride and humility

B. Support the Student Society for Bridging Diversity, originally created as the African American Club in the 1980s, to recognize and accept all members of the human race.

C. Support women on campus and in the community through Women of Power group.

14. Make A Day to Confront Racism an annual event to address power, privilege and prejudice. Allocate sufficient funds to engage a speaker with standing equal to that of Ibram X. Kendi, this year’s speaker.

15. Continue the work of the Committee on Public Safety to reduce tension and misunderstanding in interactions between BIPOC students and Public Safety Staff (PSS).

A. Provide name badges for all PSS.

B. Conduct twice yearly dialog groups between BIPOC students and PSS.

C. Complete evaluation sheets following these dialogs to set the agenda for further work.

D. Continue anti-bias training for PPS staff.

16. Prominently display recognition of distinguished BIPOC alumni.

17. Ensure continued progress by issuing a twice annual scorecard on measurable progress made on these and other recommendations emanating from the “Legacy Alumni of Color: A Blueprint for Action” report and continuing feedback.

We believe that the Legacy Alumni of Color has done something at Springfield College that no other school in the nation has done. We returned to our alma mater to help fashion a welcoming, inclusive environment for students of all racial and ethnic backgrounds.

So, that’s what became of these brokenhearted. Not a bad outcome, not a bad start.

Donald Brown is the former chair of the Legacy Alumni of Color of Springfield College and the president & CEO of Brown and Associates Education and Diversity Consulting and former director of the Office of AHANA Student Programs at Boston College. Sherry Earle is a member of the Legacy Alumni of Color of Springfield College and a teacher of gifted children in Newtown, Conn.

Editor’s Note: Donald Brown wrote “What Really Makes a Student Qualified for College? How BC Promotes Academic Success for AHANA Students” for the Spring 2002 edition of NEJHE‘s predecessor, Connection: The Journal of the New England Board of Higher Education.

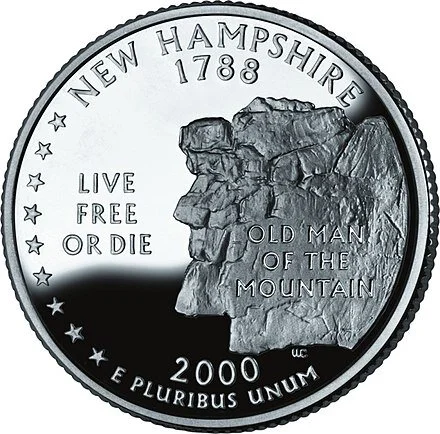

Live off Mass. or tax

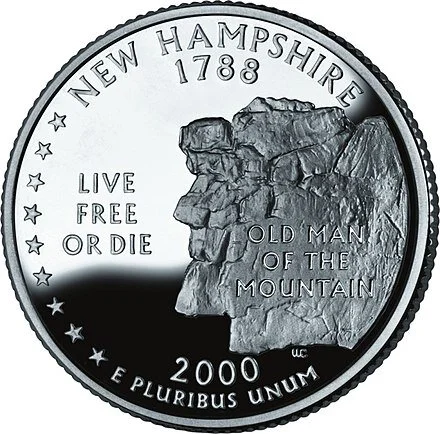

The New Hampshire quarter

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I’m rather sympathetic to Massachusetts on this one.

The U.S. Supreme Court has (surprisingly to me) declined to hear a suit seeking to bar Massachusetts from taxing people employed by Bay State companies but working remotely at home in New Hampshire since the pandemic began.

Still, this is temporary. After Sept. 13, Massachusetts will return to its prior rule, in which it will only tax workers for pay they get as a result of physically working in the state. The temporary tax move was meant to reduce the sudden fiscal hit from COVID-19.

New Hampshire (of which I’m a former resident, as I am of Massachusetts) has long been something of a parasite of the Bay State. While Massachusetts residents pay for the physical and social (especially education) infrastructure that has long made it among the two or three richest states, New Hampshire people who benefit from their proximity to it pay no state income or sales taxes, though the Granite State does have some high property and business taxes. They’re getting a nice ride.

Massachusetts’s investments in infrastructure spill over into the Granite State, whose south has become part of that great wealth-creation machine of Greater Boston, much of it stemming from its higher-education and technology complex. It seems only fair that beneficiaries of that machine who work for Massachusetts firms chip in to help keep it going.

Up against the wall

“New Galaxies,’’ from the self-portrait series Dreaming Gave Us Wings,’’ 2017—present, by Sophia Nahli Allison, at the Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence.

The ecstasy of being in Boston

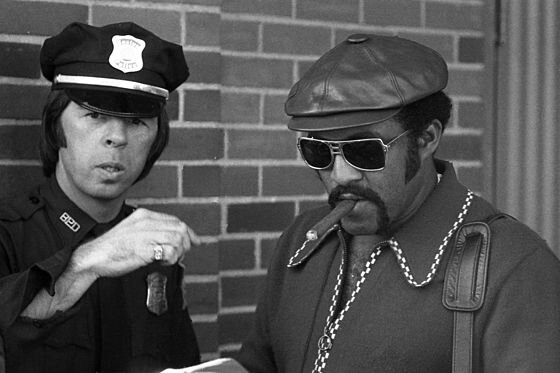

Luis Tiant outside Fenway Park in the ‘70s.

“When I’m in Boston, I always feel like I’m home. I almost cry I feel so good.’’

— Luis Tiant (born 1940), retired Major League Baseball star, most noted for his association with the Boston Red Sox.

Don't be yourself

The James Merrill House, in Stonington, Conn.

‘‘Freedom to be oneself is all very well; the greater freedom is not to be oneself.’’

— James Merrill (1926-1995) celebrated poet, in A Different Person: A Memoir. His 19th Century house in Stonington, Conn., is now a rent-free writer’s and scholar’s residence.

See:

https://www.jamesmerrillhouse.org/

Inside the James Merrill House

David Warsh: Whatever happened to Decoration Day?

“The March of Time” (oil on canvas), Decoration Day {now called Memorial Day} in Boston, by Henry Sandham (1842-1910), a Canadian painter.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Decoration Day began on May 1, 1865, in Charleston, S.C., when an estimated 10,000 people, most of them former slaves, paraded to place flowers on the newly dug graves of 257 Union soldiers who had been buried without coffins behind the grandstand of a race course. They had been held in the infield without tents, as prisoners of war, while Union batteries pounded the city’s downtown during the closing days of the Civil War.

The evolution of Decoration Day over the next fifty years was one of the questions that led historian David W. Blight to write Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (Harvard, 2001). After Blight’s book appeared, it was quickly overshadowed by the events of 9/11. Eric Foner conveyed its message most clearly in The New York Times Book Review – but only on page 28. Today Race and Reunion is more relevant than ever. For a better idea of what the book is about than I can give you, read Foner’s review.

When I was a kid, May 30, Decoration Day was still ostensibly about remembering the Civil War, but the events of that May day in Charleston were no part of the story (though the POW camp at Andersonville, Ga., certainly had become part of the lore.). The names of veterans of various wars were read on the village green. A bugler played taps. Decoration Day had been proclaimed a day of commemoration in 1868, when the commander of the Grand Army of the Republic ordered soldiers to visit their comrades’ graves. In 1890 it was declared a state holiday in New York.

And by the time that Woodrow Wilson, the first Southerner to be elected president since the Civil War, spoke at Gettysburg, on July 4, 1913, fifty years after the battle itself, the holiday had become national – but the experiences of black Americans had all but dropped out of the narrative. The hoopla was about the experiences of the Blue and the Gray, never mind that many blacks had served in the Union army.

Soon after the war had ended, another war had begun, a contest of ideas about how the meaning of the war was to be understood: the emancipation of the slaves vs. the reconciliation of the contending armies. The politics of Reconstruction – the attempted elevation of Blacks to full citizenship and constitutional equality – ended in defeat. In his book, Blight wrote, “The forces of reconciliation overwhelmed the emancipation vision in the national culture.” Decoration Day gradually became Memorial Day, just as Armistice Day in November became Veterans Day. Americans got what the novelist William Dean Howells said they inevitably wanted: tragedies with a happy endings.

The age of segregation didn’t end until the Sixties. Black leaders such as Frederick Douglass and W.E. B. Du Bois had burnished the vision of emancipation. Educators, writers, and agitators articulated it and put it into practice. A second Reconstruction began in the years after World War II. In the 1960s the Civil Rights Movement reached a political peak. A new equilibrium was achieved and lasted for a time.

So don’t fret about “Critical Race Theory.” A broad-based Third Reconstruction has begun. Blight was an early text, as was Derrick Bell’s Faces at the Bottom of a Well: The Permanence of Racism, which appeared in 1992. The tumult will continue for some time. Rising generations will take account of it. A new equilibrium will be attained. It will last for a time, before a Fourth Reconstruction begins.

In the meantime, the new holiday of Juneteenth is an appropriate successor to the original Decoration Day – a civic holiday of importance second only to the Fourth of July.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

\

Still life with house frames

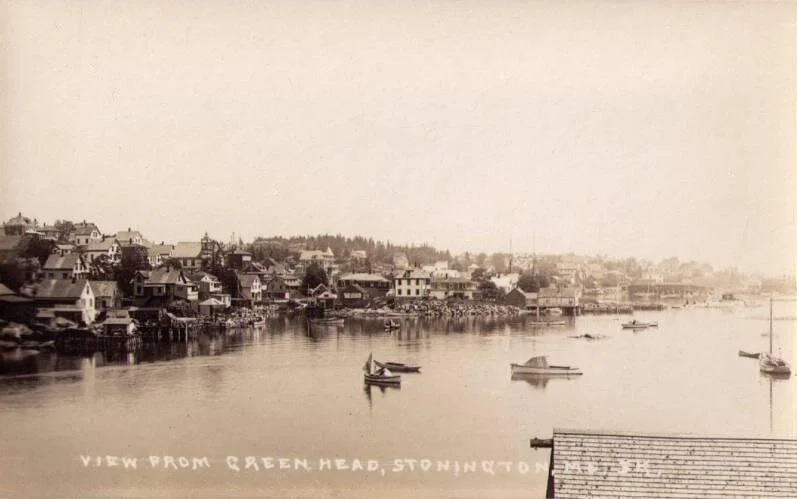

“Two Roses in Stonington {Maine},’’ by Jay Wu, in his show “Flowers, Trees and Other Things,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, through Aug 1.

Stonington, on Deer Isle, circa 1915. It remains the biggest lobster port in Maine.

The famously vibrating Deer Isle Bridge

Jill Richardson: Right-wing-run Florida's new law imperils academic freedom there

“Unveiling of the Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World” (1886) (oil on canvas), by Edward Moran, in The J. Clarence Davies Collection at Museum of the City of New York.

Via OtherWords.org

Unveiling of the Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World (1886) by Edward Moran. Oil on canvas. The J. Clarence Davies Collection, Museum of the City of New York.

Florida just passed a law that — to put it mildly — grossly violates academic freedom. Under the new bill, recently signed by Gov. Ron DeSantis, a right-wing Republican and in the past a fervent supporter of Donald Trump, students and faculty will be surveyed about their political views to ensure “intellectual freedom and ideological diversity.”

The real intent appears to be the opposite.

The bill doesn’t specify what will happen with this data once it’s collected. But DeSantis and the bill’s sponsor, state Sen. Ray Rodrigues, have suggested the responses could be used to target schools for budget cuts if politicians find the views of student and faculty objectionable.

This is a gross violation of academic freedom, which is supposed to protect students and faculty and pave the way for the production of knowledge.

As a PhD student who teaches undergraduates, I’m having visions of professors being subjected to forced confessions, as in China’s Cultural Revolution. (Scholars were so scorned then that the word “intelligentsia” — zhishifenzi — became derogatory.)

To see how state interference with academic freedom is problematic, consider Lysenkoism.

In the mid-20th Century, Soviet agronomist Trofim Lysenko rejected Mendelian genetics and instead embraced a pseudoscience of his own creation. Communists governments adopted Lysenkoism as a “Communist” science of agriculture, with disastrous consequences. Stalin executed scientists who disagreed with Lysenkoism, even while Lysenko’s pseudoscience produced famines.

I hope that Florida Republicans — who are so concerned that people like me will turn students into Communists that they’re also now mandating professors teach the “evils of Communism” — will note the irony.

Florida Republicans might also like to know that a court case upholding academic freedom (Adams vs. University of North Carolina Wilmington) was essential to protecting conservative speech as well. In that case, the court sided with Prof. Michael Adams, who’d been denied a promotion over columns he’d written for a right-wing Web site, ruling that his views were protected speech.

The second part of Florida’s bill stipulates that students may not be shielded from “ideas and opinions that they may find uncomfortable, unwelcome, disagreeable, or offensive.” Again, this is not a problem. It doesn’t need fixing. Academic freedom already takes care of it.

Setting aside the irony that legislators seem to want to exclude certain views they disagree with, I also worry that this law will ban professors from managing their classrooms.

I teach controversial topics regularly. They are emotional topics and many students come to class with different, sometimes opposing views. It feels like playing with dynamite because there is a lot to balance in running the class in a way that is fair and conducive to learning for all.

But what do you do when a student endorses genocide during a class discussion? And follows it up with a two thumbs up endorsement for racism? Does curtailing disruptive behavior like this, which prevents others from learning, count as shielding students from uncomfortable “ideas and opinions”?

On the other hand, what do you do when your class wants to use class time to organize for social causes, and your job is to get them to learn an academic discipline, not Rally For Your Political Ideology 101?

Or one student cries because of what other students have said? Or leaves class because it is too emotionally painful for him or her to be there?

Those things have happened in my class. Academics need to have the freedom to manage their classes, and that means finding a balance between protecting their students’ emotions and helping them when emotions get in the way of learning.

Most of all, teachers and students need the freedom to look at ideas academically — and express their views plainly — without fear of retribution from state authorities who insist on “intellectual freedom” even as they seek to stamp it out.

Jill Richardson is pursuing a PhD in sociology at the University of Wisconsin.

Chris Powell: Worried more about crime than PC trivia?

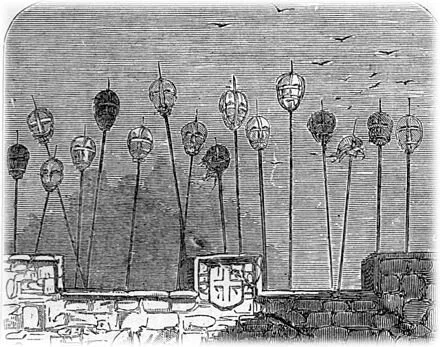

The spiked heads of executed criminals adorned the gatehouse of the medieval London Bridge.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Lately the administration of Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont has boasted about closing prisons in the state even as crime has exploded. Of course, the crime wave isn't exclusive to this state. But those in charge seem to think that since the explosion in crime can't be blamed on Donald Trump, it can be largely ignored.

So those in charge should consider the recent primary elections for mayor of New York City, where standards of political correctness are set.

It was no surprise that Curtis Sliwa, founder of the Guardian Angels crime watch group, won the Republican nomination, since Republicans encompass the law-and-order crowd. But there was some surprise in the apparent first-round victory in the Democratic primary of Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams, a former state senator and police captain.

Adams, who is Black, assembled a coalition of working-class voters from all ethnic groups and boroughs in support of a law-and-order platform. His main point is that public safety is the prerequisite of prosperity.

Could even New York City Democrats care more about public safety than politically correct nonsense like "critical race theory" and transgenderism? And if New York City Democrats can, could voters in Connecticut?

In any case Connecticut is full of criminal cases that should become political issues. The public increasingly sees, even as state government denies, that there is a scandal in the growing number of car thefts and other crimes being committed by teens and young men who know they will never be punished. The General Assembly keeps refusing to reinstate deterrence.

So the other week the 25-year-old suspect in a double shooting in Hartford in which one victim was killed was presented in court and charged with murder. It was the city's 20th murder of the year, against 25 all last year. News reports said that the defendant had been awaiting prosecution on at least five previous charges.

The other week two teens who had been living in a group home broke into and ransacked the senior citizens center in Wolcott. Stealing a car nearby, they crashed into two parked cars and then a utility pole, totaling the stolen car, before being caught. They laughed as police booked them. A judge quickly ordered them released, but after public protests they were put in detention.

And then a man jogging on a sidewalk in New Britain was struck and killed by a car stolen in Hartford. Surveillance video showed two teens running away from the scene. New Britain police located one hiding in a closet at his home and charged him with first-degree assault, reckless driving, and car theft. Though he is only 17, police said, he has been arrested 13 times in the last four years on charges including assault with a knife, narcotics possession, reckless driving, evading responsibility, car theft, and robbery. Still, he was free.

Governor Lamont weakly responded to the crime wave by proposing to spend $5 million more on crime detection. But the problem isn't detection at all but what government does with the criminals it already has detected and apprehended.

Of course, prisons aren't very good at rehabilitation. But then nothing is, and at least prisons are good at incapacitating the unrehabilitated until those in charge discover something in criminal justice that does more than strike a politically correct pose, and until they get even more relevant by asking:

Where are all the messed-up kids coming from?

xxx

Connecticut may hope that Governor Lamont was just joking the other day when asked if, now that the state is legalizing marijuana, he would smoke some. "Time will tell," the governor replied. "Not right now but we'll see."

Yes, drug criminalization has been a failure, but despite Connecticut's new law, marijuana is still prohibited by federal law, and the dignity of his office obliges the governor to obey it.

So does politics. For as a Democrat the governor already has sewn up the stoner vote, and he and his party will fare better if smoking dope can't be used to explain their raising gas taxes and coddling young criminals.

Besides, Connecticut offers much more compelling opportunities for civil disobedience. Why not try, say, buying alcoholic beverages below state-minimum prices or patronizing an unlicensed hypnotist?

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

‘Enough to stay drunk’

Pierce Cemetery, in Wolcott, Vt.

“The Pikes have come a long way down

since the old man walked to Craftsbury

every day all his life to saw boards.

There’s only Bill and Arnie left as far as I know

and both of them make only enough to stay drunk.’’

— From “The Chain Saw Dance,’’ by David Budbill (1940-2016), a poet and playwright who came to be seen as a bard of Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom.He lived in a small cabin in Wolcott for more than 40 years, where he created the fictional town of Judevine, named after a local mountain, and populated it with local folk, many highly problematic.

In Craftsbury