Abstracted walk in the woods

“Lookout” (acrylic on canvas), by Liz Hoag at Edgewater Gallery, Middlebury, Vt.

The gallery says:

“Hoag [based in Westbrook, Maine} is inspired by her walks in the Maine woods and is known for her abstracted tree-filled landscapes that give the viewer a glimpse of the hidden vignettes that exist in the forest but are often overlooked. She begins her compositions with dark canvas and builds light tones on top of the dark creating the positive space in the composition. The result is a painting that conveys the beauty of light filtering through trees and the serenity one feels on a walk in the woods.’’

This sign and gazebo are across the street from the Westbrook Public Library. The mural was a project of Westbrook Arts & Culture, painted by aerosol artist Mike Rich and funded by the Warren Memorial Foundation and several Westbrook businesses. See the old mill building in the distance.

Westbrook is an old mill town and now mostly just seen as a suburb of Portland.

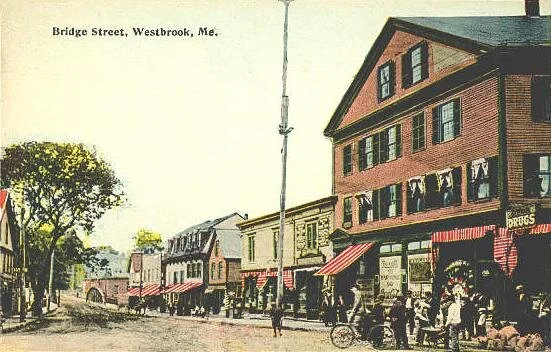

Bridge Street in Westbrook in 1912

Sounds from the field

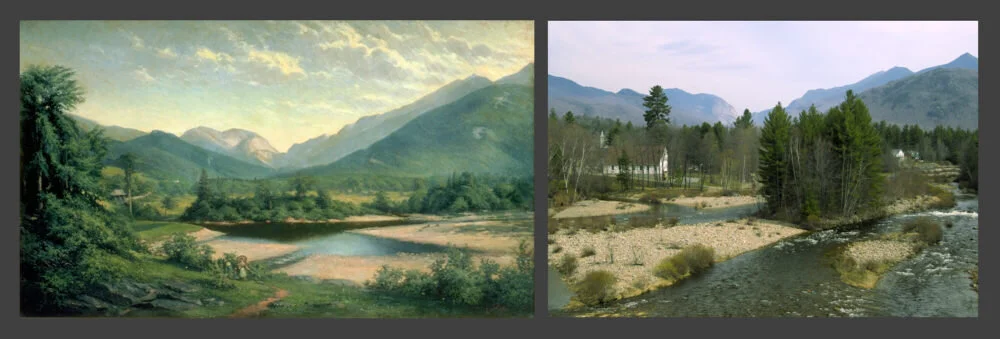

“Franconia Notch” (oil painting, left), by George Albert Frost (1843-1907); Franconia Notch in 2004 (right)

“There was a sound of grouse from the field

of grouse or a box guitar

And the way the storm idled over the mountain

revealing the mountain dissolving in light….’’

— From ‘‘Five Nights in the North Country Solstice,’’ by Kathy Fagan, an American poet. She was the poet-in-residence at The {Robert} Frost Place, in Franconia, N.H. , in 1985.

'The amount of maniacs'

Doyle's Cafe, in Boston’s Jamaica Plain neighborhood. It’s a well-known watering hole.

— Photo by John Phelan

"It’s just a really interesting place to grow up. The sports teams, the colleges, the racial tension, the state workers, the boozing, the anger. All of that stuff. I don’t think I ever appreciated the amount of maniacs that live in Massachusetts until I left. When I lived here, I took it for granted that everyone was kind of funny and a bit of a character."

— Bill Burr (born in 1968), stand-up comedian who grew up in the inner Boston suburb of Canton

Arthur Allen: Some experts skeptical about vaccinating kids against COVID-19

Tufts Children’s Hospital, in downtown Boston

Lucien Wiggins, 12, arrived at Tufts Children’s Hospital, in Boston, by ambulance June 7 with chest pains, dizziness and high levels of a protein in his blood that indicated inflammation of his heart. The symptoms had begun a day earlier, the morning after his second vaccination with the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA shot.

For Dr. Sara Ross, chief of pediatric critical care at the hospital, the event confirmed a doubt that she’d been nursing: Was the country pushing its luck by vaccinating children against COVID at a time when the disease was relatively mild in the young — and skepticism of vaccines was frighteningly high?

“I have practiced pediatric ICU for almost 15 years and I have never taken care of a single patient with a vaccine-related complication until now,” Ross told KHN. “Our standard for safety seems to be different for all the other vaccines we expose children to.”

To be sure, cases of myocarditis such as Lucien’s have been rare, and the reported side-effects, though sometimes serious, generally resolve with pain relievers and, sometimes, infusions of antibodies. And a COVID infection itself is far more likely than a vaccine to cause myocarditis, including in younger people.

Lucien went home, on the mend, after two days on intravenous ibuprofen in intensive care. Most of the 800 or so cases of heart problems among all ages reported to a federal vaccine-safety database through May 31 followed a similar course. Yet the pattern of these cases — most occurred in young males after the second Pfizer or Moderna shot — suggested that the ailment was caused by the vaccine, rather than being coincidental.

At a time when the vaccination campaign is slowing, leading conservatives are openly spreading disinformation about vaccines, and scientists fear a possible upsurge in cases this fall or winter, side-effects in young people pose a conundrum for public health officials.

On June 11, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s vaccine advisory committee is set to meet to discuss the possible link and whether it merits changing its recommendations for vaccinating teenagers with the Pfizer vaccine, which the Food and Drug Administration last month authorized for children 12 and older. A similar authorization for the Moderna vaccine is pending, and both companies are conducting clinical trials that will test their vaccines on children as young as 6 months old.

At a meeting last week of an FDA advisory committee, vaccine experts suggested that the agency require the pharmaceutical companies to hold larger and longer clinical trials for the younger age groups. A few said FDA should hold off on authorizing vaccination of younger children for up to a year or two.

Interestingly, Lucien and his mother, Beth Clarke, of Rochester, N.H., disagreed. Her son’s reaction was “odd,” she said, but “I’d rather him get a side-effect [that doctors] can help with than get COVID and possibly die. And he feels that way, which is more important. He thinks all his friends should get it.”

Data regarding covid’s impact on the young are somewhat messy, but at least 300 COVID-related deaths and thousands of hospitalizations have been reported in children under 18, which makes COVID’s toll as large or larger than any childhood disease for which a vaccine is currently available. The American Academy of Pediatrics wants children to receive the vaccine, assuming tests show it is safe.

But healthy people under 18 have generally not suffered major COVID effects, and the number of serious cases among the young has tumbled as more adults become vaccinated. Unlike other pathogens, such as influenza, children are generally not infecting older, vulnerable adults. Under these circumstances, said Dr. Cody Meissner — who as chief of pediatric infectious diseases at Tufts consulted on Lucien’s case — the benefits of covid vaccination at this point may not outweigh the risks for children.

“We all want a pediatric vaccine, but I’m concerned about the safety issue,” Meissner told fellow advisory commission members last week. An Israeli study found a five- to 25-fold increase in the heart ailment among males ages 16-24 who were vaccinated with the Pfizer shot. Most recovered within a few weeks. Two deaths occurred in vaccinated men that don’t appear to have been linked to the vaccine.

Young people could experience long-term effects from the suspected vaccine side-effect such as scarring, irregular heartbeat or even early heart failure, Meissner said, so it makes sense to wait until the gravity of the problem becomes clearer.

“Could the disease come back this fall? Sure. But the likelihood I think is pretty low. And our first mandate is do no harm,” he said.

Ross said the biggest pandemic threats to children that her ICU has witnessed are drug overdoses and mental illness brought on by the shutdown of normal life.

“Young children are not the vectors of disease, nor are they driving the spread of the epidemic,” Ross said. While eventually everyone should be vaccinated against COVID, use of the vaccines should not be expanded to children without extensive safety data, she said.

The government could authorize childhood vaccination against COVID without recommending it immediately, noted Dr. Eric Rubin, an advisory committee member who is editor-in-chief of the New England Journal of Medicine. “In September, when kids are back in school, people are indoors, and the vaccination rates are very low in certain parts of the country, who knows what things are going to look like? We may want this vaccine.”

Moderna and Pfizer this summer began testing their vaccines in younger kids. A Pfizer spokesperson said the company expects to give about 2,250 children ages 6 months-11 years vaccine as part of its trial; Moderna said it would vaccinate about 3,500 children in the 2-11 age range.

Some members of the FDA advisory committee proposed that up to 10,000 kids be included in each trial. But Marion Gruber, leader of the FDA’s vaccine regulatory office, pointed out that even trials that large wouldn’t necessarily detect a side-effect as rare as myocarditis seems to be.

At some point, federal regulators and the public must decide how much risk they are willing to accept from vaccines versus the risk of a COVID virus that continues to spread and mutate around the world, said Dr. Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

“We’re going to need a highly vaccinated population for years or perhaps decades,” Offit said at the meeting. “It seems hard to imagine that we won’t have to vaccinate children going forward.”

Ross argued that it makes more sense to selectively vaccinate children who are most at-risk for serious covid disease, such as those who are obese or have diabetes. Yet even to raise questions about the vaccination program can be a freighted decision, she said. While authorities have a duty to speak frankly about the safety of vaccines, there is also a responsibility not to frighten the public in a way that discourages them from seeking protection.

A 10-day pause in the Johnson & Johnson vaccination campaign in April, while authorities investigated a link to an occasionally fatal blood-clotting disorder, led to a major decline in public confidence in that vaccine, although as of late May authorities had detected only 28 cases among 8.7 million U.S. recipients of the vaccine. Because of the declining appetite for the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, millions of doses are in danger of passing their use-by date in refrigerators around the country.

Focusing too much attention on potential harms from the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines for children could have a tragic result, said Dr. Saad Omer, director of the Yale Institute for Global Health and an expert on vaccine hesitancy. “Very soon we could be in a situation where we really need to vaccinate this population, but it will be too late because you’ve already given the message that we should not be doing it,” he said.

Eventually, perhaps next year, K-12 mandates might be called for, said Dr. Sean O’Leary, a professor of pediatric infectious diseases at the University of Colorado. “There’s so much misinformation and propaganda spreading that people are reticent to go there, to further poke the hornet’s nest,” he said. But once there is robust safety data for children, “when you think about it, there’s no logical or ethical reason why you wouldn’t.”

Arthur Allen is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

But just water vapor

“Forbidding & Sublime”” (oil painting), by Linda Pearlman Karlsberg, at Alpers Fine Art, Andover, Mass.

Self-complacent city

“Boston is a curious place….When a society has reached this point, it acquires a self-complacency which is wildly exasperating. My fingers itch to puncture it.; to do something which will sting it into impropriety.’’

Henry Adams (1838-1918), famed historian, autobiographer and descendent of Presidents John Adams and John Quincy Adams

Leave it to those species

Lobstermen in Casco Bay, Maine

As a child of Maine, he knew better than to learn to swim in the water {there}; the Maine water, in Wilbur Larch’s opinion, was for summer people and lobsters.’’

— John Irving, in his (1985) novel Cider House Rules

Brian P.D. Hannon: Invasive ticks in the Northeast

An Asian longhorned tick nymph, left, and an adult female.

— Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) photo

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

This year’s tick season has brought an unwelcome development beyond the usual concerns about the disease-bearing arachnids with the confirmation of what one scientist said is a new invasive species in the Northeast.

The Asian longhorned tick, which poses a threat to livestock, was found in April to have moved to the Rhode Island mainland after an initial discovery on one of the state’s islands last year.

“This is truly an invasive species,” said Thomas Mather, a professor of public health entomology at the University of Rhode Island.

The ticks pose a risk to livestock because they attach themselves to various warm-blooded animals to feed. If too many attach to one animal, the loss of blood can kill the animal.

Mather said he found four Asian longhorned ticks about a month ago in South Kingstown while looking for the common blacklegged ticks known to bedevil outdoor enthusiasts and pet owners with the threat of Lyme disease and other infections transmitted through their bites as they hatch and grow to maturity in spring and summer.

Tick season is now in full swing .

“We’ve been seeing sporadic nymphs since April,” said Mather, noting these efficient carriers of disease will continue to spread as temperatures rise. “Somewhere around the week before Memorial Day they start to reach their peak numbers.”

The Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM) announced in late September that the Asian longhorned tick had been detected on Block Island, about nine miles off the mainland. But Mather’s recent discovery was the first on the state’s mainland and the presence of both nymphal and adult-stage ticks indicates that they have been present for at least one life cycle, he said.

Known by the scientific name Haemaphysalis longicornis, the Asian longhorned tick was first detected in the United States in 2017. As of early October 2020, the tick was known to be in Northeast states, including Rhode Island, Connecticut, Delaware, New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Other states where the tick appears include Arkansas, Kentucky, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Ohio, Tennessee, Virginia and West Virginia, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Mather said the Asian longhorned tick differs in a few key ways from the blacklegged ticks, which are better known as deer ticks for their habit of using white-tailed deer as hosts.

The Asian longhorned tick can be found in batches of thousands in grass, shrubbery or on animals. But they don’t require the same high levels of humidity needed for survival by other tick varieties, Mather said.

“They don’t mind being out in the open” said Mather, noting that the arachnids can live in sunny areas beyond the moist lawn edges, fallen leaves or high grass areas normally targeted by homeowners or professional pest controllers applying insecticides.

Adult blacklegged tick (aka deer tick)

— CDC photo

Ticks feed on blood, with the blacklegged strain preferring white-tailed deer and white-footed mice, which are a primary source of tickborne Lyme disease. Up to 70 percent of white-footed mice in Rhode Island carry the Lyme bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, Mather said.

The parasites transmit infections by exchanging blood with those they bite, whether animals or humans. The longer they remain attached, the more blood and germs they pass, making their quick removal paramount to avoiding Lyme disease, which causes headaches, fatigue, swollen lymph nodes, muscle and joint aches, fever and chills.

“It takes some time for the Lyme disease-causing bacteria to move from the tick to the host,” according to the CDC. “The longer the tick is attached, the greater the risk of acquiring disease from it.”

The first known instance of an Asian longhorned tick biting a person was in June 2018 in Yonkers, N.Y., which was reportedly confirmed by the CDC. As testing continues in the United States, “it is likely that some ticks will be found to contain germs that can be harmful to people. However, we do not yet know if and how often these ticks are able to pass these germs along to people and make them ill,” the CDC reported.

“This tick is a little weird. Happily, though, it doesn’t seem to like to bite people,” said Mather, who noted the Asian longhorned isn’t believed to be a Lyme disease carrier.

Deer ticks are among the most prevalent types in Northeast and Mid-Atlantic states, along with larger dog ticks, although only the former carry Lyme disease.

Ticks can also transfer anaplasmosis and babesiosis, blood infections with symptoms including fever, chills and sweats, fatigue and gastrointestinal ailments such as nausea and vomiting. One in four ticks in Rhode Island carry the germ causing Lyme disease, but Mather warned vaccination strategies focusing on Lyme prevention alone can cause a false sense of security and possibly result in the other infections being overlooked.

Climate change has no direct effect on ticks, because they are affected by humidity levels rather than temperature. Without enough humidity, ticks will dry up like a plant without enough water, but they can survive in varying climates.

“These ticks are in Duluth, Minnesota,and Florida,” Mather said. Yet he explained the changes in global climate can impact ticks – hurting or helping them – by altering the number of animals on which they feed. “The change that we’re finding is more related to the presence or absence of reproductive hosts.”)

Mather said Rhode Island also has experienced an increase in lone star ticks. Lone star ticks, which have moved northward in the United States for a decade, were previously only found off Rhode Island’s shore on Prudence Island, but now have infested Conanicut Island, Mather said.

A lone star tick

The lone star tick is a “very aggressive biter but it won’t carry or transmit the Lyme disease germ,” said Mather, who added there is still a danger of the parasites transmitting anaplasmosis and babesiosis.

Mather said lone star tick bites can also produce a red-meat allergy. Ticks taking in blood from an animal can ingest a specific sugar — galactose-α-1,3-galactose, also known as alpha-gal — found in red meat and then transfer the material to humans. The resulting symptoms, including rash, hives, nausea and difficulty breathing, can take hours to first appear and possibly months to fully develop, making the bite, rather than the existing allergy — referred to as Alpha-gal syndrome — appear to be the cause of the adverse reaction.

The University of Rhode Island’s TickEncounter website provides abundant information about the arachnids and the harmful infections they transmit, as well as tools for sharing tick locations, strategies to avoid bites and blog posts by experts.

People who plan to be in tick habitats should wear clothing treated with the tick-killing chemical permethrin and use tactics to prevent the insects from reaching skin such as tucking pant legs into socks. Daily tick checks are also important, especially in hiding spots including the backs of knees, inside armpits and around waistbands.

Regardless of the type of tick encountered, Mather echoed the CDC warning about removing the parasites as quickly as possible.

“The longer a tick is attached, the more likely it’s going to deliver an infectious dose,” he said.

Brian P.D. Hannon is an ecoRI News journalist.

‘Like raccoons’

“The Swimming Hole’’ (1885), by Thomas Eakins

“Remember the way we bore our bodies to the pond

like raccoons with food to wash? Onto the blue,

smooth foil of the gift-wrapped water I slid….’’

— From “Puberty,’’ by William Matthews (1942-1997), an on-and-off New Englander

Off season

“At Noon,’’ by Niva Shrestha, in her show “Place,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, July 2-Aug. 1

She tells the gallery:

"Architecture has been the main subject in my work for the last nine years. From windows to rooftops, stairs to poles; every line and shape are intertwined creating movements and stillness. Thus, I paint with the inspiration from these places where wonderful and playful compositions are naturally formed. ‘‘

Don’t leave the corridor

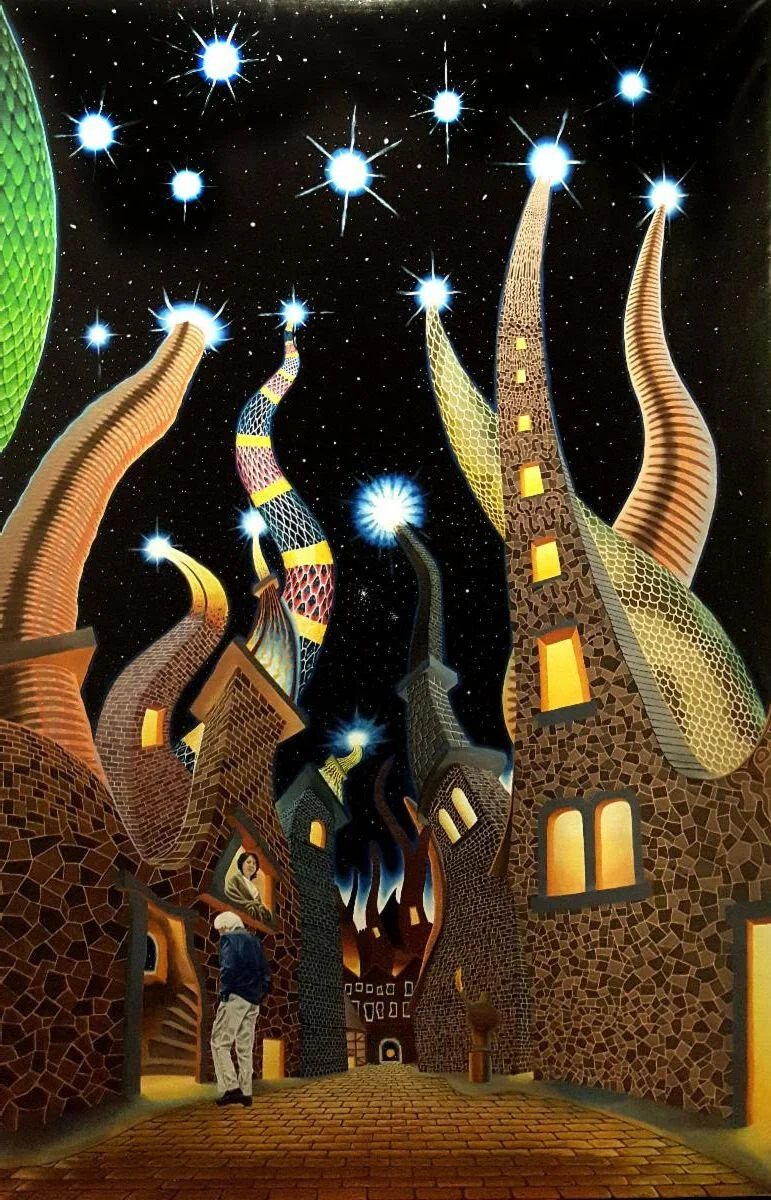

“Gateways” (oil on canvas), by Dave Martsolf, in his show “Through the Eyes of a Child,’’ at the Art League of Lowell’s Greenwald Gallery, June 23-July 18. Mr. Martsolf (born 1949) lives and works in Windham, N.H.

Searles Castle in Windham

19th Century textile mill (now a museum) and canal in Lowell

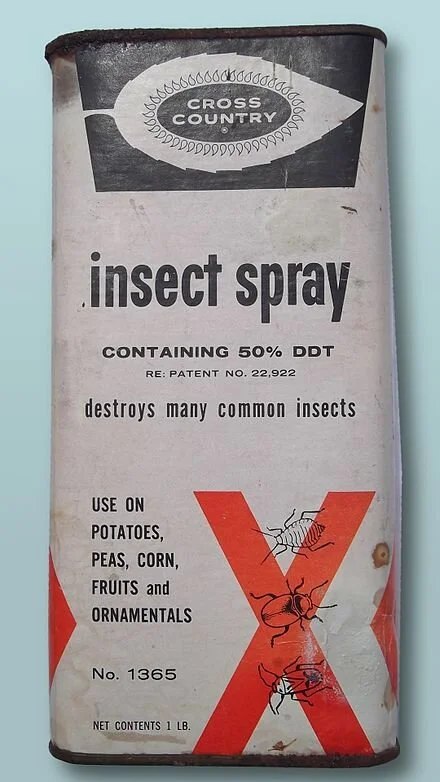

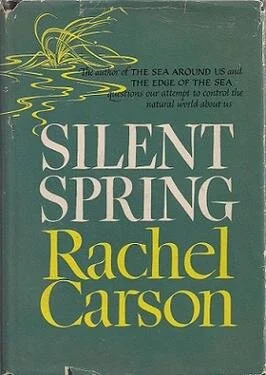

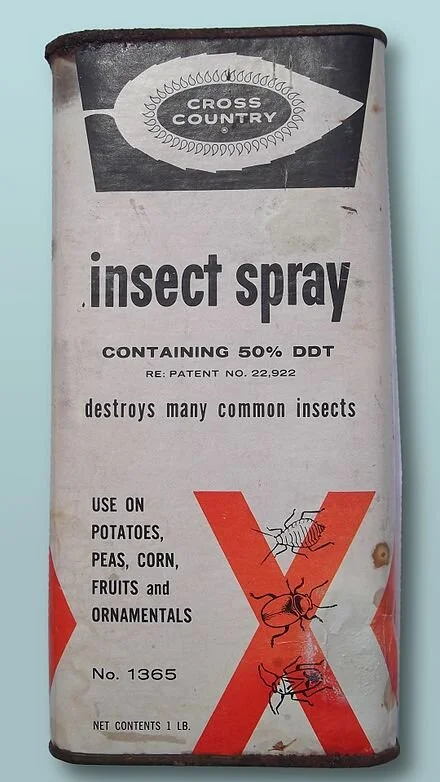

A book stopped DDT spraying

Cover of the first edition of Silent Spring

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I read Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring on our back porch in the summer of 1962 as it was first published, in The New Yorker magazine. I already liked her stuff, especially The Sea Around Us and The Edge of the Sea (but then, my family lived on Massachusetts Bay).

Silent Spring told of the devastating effects of pesticide use, and especially of DDT, on ecology. The book’s title comes from the fact that the stuff was killing songbirds and other creatures in vast numbers. Despite pushback from chemical companies, the U.S. banned DDT in 1972, for which we can thank Rachel Carson.

We were so blithe about pesticide use back then. I remember small planes swooping down to spray fields, golf courses, woods, marshes and even suburban subdivisions. (For that matter, people were still pretty relaxed about cigarettes, despite the mounting evidence of their lethal effects.)

We’re still too blithe about herbicide use – e.g., Roundup – which causes short-and-long-term damage to the environment. There’s been no book out yet about their use and misuse with the impact of Silent Spring. Anyway, thanks to Ms. Carson, at least we aren’t being drizzled with poisons from planes flying a couple of hundred feet over the ground on nice summer days. I remember adults warning “Don’t look up!’’

Too bad that so many people hate weeds. Some are beautiful and most of what we eat is in effect cultivated weeds.

An airplane spraying DDT over Baker County, Ore., as part of a spruce budworm control project in 1955

'Green oracle'

“A Day in June” (1913), by George Bellows

“You are the green oracle

cursed to remember

the seasons that circle

like the buzzards in

the dead heat.’’

— Ian Mathes, from “A Day in June’’

“Flaming June’’ (1895), by Lord Leighton

Biscuits and kittens in Vt.

Main Street in Bristol, Vt., at the western edge of the Green Mountains

“Even my children, though born here, would not be called Vermonters by most members of long-time Bristol {Vt.} families. (My neighbors might well respond, if I put the question to them, with the old Vermont joke: If the cat has kittens in the oven, does that make them biscuits?)’’

—- John Elder, in Reading the Mountains of Home (1971)

Lord’s Prayer Rock in Bristol

David Warsh: Article seems to have prompted Biden to order probe into idea that engineered COVID leaked from lab

Did COVID-19 escape from this complex?

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

There are few better-known brands in public service journalism than the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Founded in 1945 by University of Chicago physicists who helped produce the atom bomb, the organization adopted its famous clock logo two years later, with an original setting of seven minutes to midnight. Since then it has expanded the coverage of its monthly magazine and Web page to include climate change, biotech and other disruptive technologies.

In May, it published “The origin of COVID: Did people or nature open Pandora’s box at Wuhan?,” by veteran science journalist Nicholas Wade. Its appearance apparently prompted President Biden to ask U.S. intelligence agencies to reassess the possibility that a virus genetically engineered to become more dangerous had inadvertently escaped from a partly U.S.-funded laboratory in Wuhan, China, the Wuhan Institute of Virology. So when the Bulletin last week produced publisher Rachel Bronson, editor-in-chief John Mecklin and Wade for a one-hour q&a podcast, I tuned in.

Wade, too, has a substantial reputation. He served for many years as a staff writer and editor for Nature, Science and the science section of The New York Times. He is the author of many books as well, including The Nobel Duel: Two Scientists’ Twenty-one Year Race to Win the World’s Most Coveted Research Prize (1980), Before the Dawn: Recovering the Lost History of Our Ancestors (2006), and The Faith Instinct (2009).

True, Wade took a bruising the last time out, with Troublesome Inheritance: Genes, Race, and Human History (2014), which argued that human races are a biological reality and that recent natural selection has led to genetic difference responsible for disparities in political and economic development around the world. Some 140 senior human-population geneticists around the world signed a letter to The New York Times Book Review complaining that Wade had misinterpreted their work. But the editors of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists would have taken that controversy into consideration.

The broadcast was what I expected. Publisher Bronson was proud of the magazine’s consistent attention to issues of lab safety; investigative journalist Wade, pugnacious and gracious by turns; editor-in-chief Mecklin, cautious and even-handed. When they were done, I re-read Wade’s article. I highly recommend it to anyone interested in the details. He is a most lucid writer.

What comes through is connection between the U.S. National Institutes of Health and the Wuhan lab, one of several, in which NIH was funding a dangerous but essentially precautionary vaccine-development enterprise known as “gain-of-function” research (see Wade’s piece for a lucid explanation). Experts have known since the beginning that the virus was not a bioweapon. The only question was how it got loose in the world. What I find lacking in Wade’s account is context.

From the beginning, the Trump, administration sought a Chinese scapegoat to distract from the president’s failure to comprehend the emergency his government was facing. Wade complains that “The political agendas of governments and scientists” had generated “thick clouds of obfuscation that the mainstream media seem helpless to dispel.”

What he fails to recognize is the degree to which the obfuscation may have been deliberate, foam on the runway, designed to prevent an apocalyptic political explosion until vaccines were developed and the contagion contained. In the process, a few whoppers about the likelihood that the virus had evolved by itself in nature were devised by members of the world’s virology establishment. Wade’s generosity in his acknowledgments at the end of his article make it clear there was ample reason to want to know more about the lab-leak explanation long before Biden commissioned a review.

Wade is a journalist of a very high order, but to me he seems tone-deaf to the overtones of his assertions. I was reminded of a conversation that Emerson recorded in his journal in 1841. “I told [William Lloyd] Garrison that I thought he must be a very young man, or his time hang very heavy on his hands, who can afford to think much, and talk much, about the foible of his neighbors, or ‘denounce’ and ‘play the son of thunder,’ as he called it.” Wade, in contrast, likes to quote Francis Bacon: “Truth is the daughter, not of authority, but time.”

But remember too that time, as the saying goes, is God’s way of keeping everything from happening at once. The news Friday that The New York Times has been recognized with the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for Public Service for its coverage of the pandemic was not surprising. There are six months of developments yet to go in 2021, but my hunch is that, when preparations begin for the award next year, a leading nominee will be the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

David Warsh, an economic historian and a veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first appeared.

Under the brown water

— Photo by Bernd Schade

“What I grew up seeing as a wall of green

is really a thousand species of the rare

and seldom seen. The average swamp

is a death of stumps and snakes

the eye teases from the submerged vegetation,

hardly knowing what’s imagined

from what the brown water covers….’’

— From “The Faithful,’’ by Cleopatra Mathis (born 1947), New Hampshire based poet and professor

The bumpy road to less speeding

— Photo by Alex Sims

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I have complained about the high bumps (which the city quaintly calls “humps’’) on the road coming off the Henderson Bridge and heading to Providence’s Wayland Square neighborhood. I suggested that they be “adjusted’’ – lowered – to avoid damaging vehicles and to discourage swerving. Driving there last week, I saw that the bumps had been removed. But modest bumps there would be good, discouraging drivers from speeding into Wayland Square, with its many walkers.

In general, speed bumps, with, on some roads, indentations so that fire trucks can speed through, are a very good idea. They needn’t be quite as high as those above were to make drivers slow down. An important factor in their effectiveness is adequate warning. Two warning signs well spaced instead of one would lead to more slowing well before the bumps. Those electronic signs that flash your speed can be very useful, too.

Traffic calming is needed to improve safety and the quality of life in the city. Bumps and electronic warnings can be important parts of that, freeing up police officers to spend more time preventing and responding to serious crime. And cars going very fast are often driven by criminals. If they hit a speed bump at, say, 80 miles an hour, it could stop them very quickly, indeed perhaps ruin the vehicle they’re in – making it easier for the cops to arrest them. It’s hard to escape in a car with a broken axle.

And if the city fines a lot of people of people for speeding (as they have me a couple of times), well, the city can use the money, and the threat of fines may save some lives.

'Creation and destruction'

“Glory in the Celestial Flower’’ (mixed media and acrylic on plaster panel) by Isabel Riley, in her joint show with Lynne Harlow entitled “GLOW,” at Drive-by-Projects, Watertown, Mass., through Aug. 14.

The gallery says: “Riley's painting … are equal parts creation and destruction as she alternates between building surfaces up and scrubbing them down. She does this in the pursuit of imagined, subconscious spaces and dynamic color.”

‘Most important fish in the sea’

Atlantic menhaden

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Even though menhaden are eaten by few people, more pounds of the oily fish, often called “pogies” or “bunkers” by New Englanders, are harvested each year than any other in the United States except Alaska pollock.

The Atlantic menhaden fishery is largely dominated by industrial interests that remove the nutrient-rich species in bulk by trawlers to make fertilizer and cosmetics and to feed livestock and farmed fish. Commercial bait companies fish for menhaden to provide bait for both recreational fishing and for the lobster fishery. Recreational fishermen also access schools of menhaden directly and use them as bait for catching larger sport fish such as striped bass and bluefish.

This demand puts a lot of pressure on a species that plays a vital role in the marine ecosystem. For instance, juvenile menhaden, as they filter water, help remove nitrogen.

Conservationists often refer to menhaden as “the most important fish in the sea” — after the title of a 2007 book by H. Bruce Franklin. They believe that menhaden deserve special attention and protection because so many other species, such as bluefish, dolphins, eagles, humpback whales, osprey, sharks, striped bass and weakfish, depend on them for food.

This year’s spring migration of menhaden has brought a large influx of the forage fish into Narragansett Bay. As a result, there has been a marked increase in the number of fishing vessels and fishing activity there, according to the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM).

Agency officials said members of its Law Enforcement and Marine Fisheries divisions are closely monitoring this fishing activity.

“Rhode Island relies on Atlantic menhaden in various capacities, such as supporting commercial harvesters, recreational fisheries and the Narragansett Bay ecosystem,” said Conor McManus, chief of the DEM’s Division of Marine Fisheries. “Through our Atlantic menhaden management program, which represents one of the most comprehensive plans for the species in the region, we have constructed a science-based program that strives for sustainable harvest.”

To prevent local depletion of menhaden and to ensure a healthy population of the fish remains in Narragansett Bay’s menhaden management area for ecological services and for use by the recreational community, the DEM administers an annual menhaden-monitoring program. From May through November, a contracted spotter pilot surveys the management area twice weekly to estimate the number of schools and total biomass of menhaden present.

Biomass estimates, fishery landings information, computer modeling and biological sampling information are used to open, track and close the commercial menhaden fishery as necessary. DEM regulations require at least 2 million pounds of menhaden be in the management area before it’s opened to the commercial fishery. If at any time the biomass estimates drop below 1.5 million pounds, or when 50 percent of the estimated biomass above the minimum threshold of 1.5 million pounds is harvested, the commercial fishery is closed.

Commercial vessels engaged in the Rhode Island menhaden fishery are required to abide by a number of regulations, including net size restrictions, call-in requirements to DEM, daily possession limits and closure of the management area on weekends and holidays.

Taking in city life

“City Hall Picket Line” (pencil and gouache), by Joseph Delaney (1936), in the show “Joseph Delaney: Taking Notice,’’ at the Bates College Museum of Art, Lewiston, Maine.

The museum says:

“African American artist Joseph Delaney (1904-1991) took notice of life around him. He was drawn to figurative art and lively scenes of urban life, and his work focused primarily on the people and environment of New York City, the place where he lived much of his adult life. Delaney was an acute observer of people and their activities, and he recorded them, sometimes in paintings, but more often in works on paper—drawings, pen and ink washes, watercolors, and in the notebooks that he carried and drew in everywhere he went.

“Delaney, who created thousands of works in a life spanning every decade of the twentieth century, was recognized but never celebrated during his life. Since that time, institutions and collectors have increasingly taken notice of his work, which is now in collections including the Art Institute of Chicago and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

“Taking Notice’’ is the first exhibition in New England devoted to the work of Joseph Delaney. Drawn primarily from the extensive holdings of the University of Tennessee and complemented with several works from private collections and the Bates Museum of Art, it features paintings and many works on paper, representing a breadth of subjects about life in the city that fascinated Delaney during his prolific life, including parades and protests, figure drawings and portraits, and monuments and parks in Manhattan.’’