Fun in Fitchburg when we need it

“Untitled (Balloons) Coney Island, Brooklyn, NYC” (Kodak Endura metallic print), by Ruben Natal-San Miguel, in the show “The BIG Picture: Giant Photographs and Powerful Portfolios,’’ at the Fitchburg (Mass.) Art Museum, through June 6.

The museum says: “Discover exciting recent acquisitions to the Fitchburg Art Museum’s growing collection of photography: from huge digital color prints to portfolios of related works by innovative contemporary artists.’’

Fitchburg, in north-central Massachusetts, in its industrial heyday. Originally powered by water power from the Nashua River, large factories produced machines, tools, clothing, paper and guns. The city is noted for its architecture, particularly in the Victorian style, built at the height of its mill town prosperity. A few examples: the Fay Club, the old North Worcester County Courthouse and the Bullock House.

For a small city, the Fitchburg Art Museum has a remarkably rich collection and many exciting events.

Chris Powell: To change city's image its reality must be changed

Spiffy Blue Black Square in West Hartford

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Amid dissension and turnover at Hartford's Wadsworth Atheneum, an art museum of international standing, Hartford Business Journal editor Greg Bordonaro wrote the other day that the city has an "image problem," especially when compared to West Hartford, about which The New York Times recently published a report lauding, among other things, the suburb's great restaurants. (The Times seldom cares much about anything in Connecticut unless it's edible.)

But while The Times was merely patronizing, Bordonaro was profoundly mistaken. For the dissension at the art museum has no bearing on Hartford's image, and the city doesn't have an image problem but a reality problem.

Dissension at the art museum is nothing compared to the other recent widely publicized troubles of the city.

For starters, Hartford has a "shot spotter" system that is often in the news as it monitors all the gunplay in the city. While it is a small city, Hartford has murders every month, some especially depraved, like April's murders of 3- and 17-year-old boys.

Even so, Hartford also has a cadre of political activists who want to "defund the police" and who last summer bullied Mayor Luke Bronin into cutting the police budget just before a spate of murders caused him to ask Gov. Ned Lamont to send in state troopers.

Some elected officials in West Hartford embody political correctness, but at least the town has a respectable school system, which Hartford doesn't. Even as the city's schools kept deteriorating a few years ago, Hartford put itself on the verge of bankruptcy by contracting to build a minor-league baseball stadium it couldn't afford, leading to a bailout by state government, the assumption of more than $500 million of the city's long-term debt.

Downtown West Hartford long ago superseded downtown Hartford as the hub of central Connecticut not because of the lovely restaurants lauded by The Times but because the suburb still has large middle and upper classes residing near its downtown, while misguided urban renewal in the 1960s turned downtown Hartford into an office district without a neighborhood.

Most of all West Hartford is desirable residentially because many of its children have two parents at home, while most children in Hartford are lucky if they have even one parent around and so tend to live in financial, educational, and emotional poverty.

Art museums are nice but with or without them middle-class places can take care of themselves. Impoverished places can't.

Now Hartford city government is considering paying a special stipend to single mothers in the hope that it will help them climb toward self-sufficiency. Such projects in other cities have not produced impressive results even as they risk inducing more women to adopt the single-parent lifestyle when they can't even support themselves.

But Hartford can't be blamed too much, for the city's poverty is largely the consequence of state government policy -- the failure of state welfare and education policy. Hartford and Connecticut's other cities are what happens when welfare policy makes fathers seem unnecessary, relieves them of responsibility for their children, and aborts family formation, and when social promotion in school tells students that they needn't learn.

Of course ,social promotion is also policy in West Hartford and suburbs throughout the state, but those towns have parents who compel their kids to take education more seriously.

To achieve racial and economic class integration and to reduce housing prices generally, Connecticut urgently needs to build much more inexpensive housing in the suburbs and should outlaw the worst of their exclusive zoning. But the state has an even more urgent need to stop manufacturing the poverty that has been dragging the cities down for decades.

When the cities themselves are less poor, when more of their children have fathers at home and come to school ready to learn, when their home and school environments motivate rather than demoralize them, more people will want to live in Hartford just as people now want to live in West Hartford -- and the management of the art museum won't mean any more than it means now.

To change Hartford's image -- and Bridgeport's and New Haven's -- state government has to change their reality.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Dunkin' Donuts Park, in Hartford. It is the home of the Minor League team the Hartford Yard Goats. It’s been a financial disaster for the city so far.

'Blurred thumbprint'

“In a parking lot in Boston,

a flock of birds passed over me,

blurred thumbprint on the massing clouds.

The hair on the back of my neck

moved with wind….’’

— From Vermont poet Jennifer Bates’s “Storm, after ‘Approaching Storm: Beach Near Newport,’” by Martin Johnson Heade (1819-1904)(above)

David Warsh: The tradeoffs of financial-market stability and widening inequality

The New York Stock Exchange feeling patriotic

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It was a powerful column, appearing last month in The Washington Post and ProPublica, an online news site that had participated in its preparation, and it wanted a rejoinder. Allan Sloan is the dean of American financial columnists and Cezary Podkul, a former investigative reporter for The Wall Street Journal is now working on special projects of his own.

The Federal Reserve Board’s “quantitative-easing” policies since 2009 have helped stabilize the economy, promote employment, keep home prices rising, and support the stock market, wrote the pair. But the Fed’s bond-buying spree otherwise had done little to better the lives of those who possessed only income rather that wealth.

Moreover, because no matter how rich you are, you can only spend so much on housing, share prices since 2009 have steadily grown faster than had home equity – the value of all homes less their debt. A total market index, the Wilshire 5000, gained $22.4 trillion in value since the Fed’s most recent intervention, in response to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. In contrast, the nation’s total home equity rose only $1.3 trillion in the same period.

Since 89 percent of all stocks and mutual funds are owned by the top 10 percent of the wealth distribution, and 53 percent by the top 1 percent, the well-to-do and rich have done much better than everyone else, thanks to Fed policies. In contrast, for those nearing retirement in the bottom half of the nation’s income distribution, Social Security benefits represent something like 60 percent of net worth.

Spokespersons at the Fed, the Treasury Department or the White House declined to discuss with the authors their conclusions about the impact of soaring stock prices on inequality. So they looked for discussion by policy makers involved – Fed chair Jerome Powell, former chairs Janet Yellen, Ben Bernanke – and didn’t find much. Bernanke had argued that whatever effects that monetary policy had on inequality probably would be small compared to the ongoing effects of technology and globalization; Yellen defended low interest rates. Older savers were suffering, she acknowledged, but they had children and grandchildren.

As it happens, Agustín Carstens, general manager of the Bank for International Settlements, last week tackled the problem head-on. He spoke at Markus Academy, an online symposium open to all comers, organized by Princeton University economist Markus Brunnermeier.

If the Federal Reserve System is hard to understand, the BIS, based in Basel, Switzerland, is even harder to explain. A lending conduit for central banks around the world, the BIS was established, in 1930, by the League of Nations, to coordinate reparations payments mandated in the aftermath of World War I. It proved valuable enough as a light-touch coordinator of the global banking system to have been reinforced after 1945, despite having been pressed into service by the Nazis during the Second World War.

In a speech, Carstens laid out the logic of quantitative easing in the language of central banking. These days its task was generally considered to be two-fold: limiting business-cycle fluctuations and delivering low and stable inflation. It was widely recognized that recessions and high inflation damaged the interests of the poor and middle classes more than those of the well-to-do and the rich.

But a little-noted part of central bankers’ mission had evolved historically, he noted: managing financial stability, and restoring it when lost. Lost it had been, at least for a time, in the Great Financial Crisis of 2008. Central banks have done all they could since to restore it, he said.

Two factors in the present day especially complicate the task: Inflation has been low, and less responsive to policy than in the past, and financial factors more volatile than before.

Technical change, institutional evolution and globalization have been the primary forces driving the inequality that has been surging for decades. There was little that monetary policy could do to put on the brakes. That was a job for public policy, for fiscal policy in particular. “Monetary policy can do a lot to stabilize the economy, but it cannot do it alone.”

[G]overnment intervention to help repair balance sheets is critical to resolve the crisis and set the basis for a healthy recovery. However, in the process, central banks may be criticized for supporting Wall Street at the expense of Main Street. But this is a false dichotomy, as central banks target broader financial conditions as a channel to limit the impact of the crisis for the benefit of the entire economy.

Or, as Jason Furman put it, in plain language, more simply than Carstens, “I don’t want to have a lower stock market and higher unemployment.” The former chair of President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers, now a Harvard professor, was the one authority willing to discuss trade-offs of the present situation with Sloan and Podkul.

To their credit, they gave Furman the last word.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first appeared.

Beating the heat, if it ever comes

“The Swimmer” (oil on panel), by Lee Roscoe, at the Cahoon Museum of American Art, Cotuit, Mass. The painter is based on Cape Cod. When you think of swimming on Cape Cod, you think of beaches but there are many fine fresh-water kettle ponds to swim in on the peninsula, and the water is a lot warmer than the ocean and bay water.

The elements of Maine

View of the Damariscotta River, in Maine. The river, which is mostly an estuary, is the heartland of the state’s growing oyster-aquaculture industry.

“There are a few essential elements you find in the spirit of a Mainer: a humble appreciation of well-crafted things, wit dry enough you may not know when the joke ends and when it begins and most importantly, a love for the land and the sea.’’

— Anthony Bourdain (1956-2018) was an American chef, author, journalist and international travel documentarian

'An Inward Sea'

From Jennifer Wen Ma’s show “An Inward Sea,’’ at The New Britain (Conn.) Museum of American Art, through Oct. 24.

The museum says:

“In recent years, Ma (born 1973 in Beijing) has explored themes of utopia, dystopia, and the human condition in immersive and participatory installations. ‘An Inward Sea’ continues this exploration, while reflecting deeply on the events of the last year--including the COVID-19 pandemic, extensive shut downs, and subsequent racial justice uprising in the U.S. --and how they have impacted the lives of residents of New Britain and beyond.”

Robert Whitcomb: Beacon Hill — 19th Century theme park

Houses on Louisburg Square, the most exclusive part of Beacon Hill

Cobblestoned Acorn Street

Via The Boston Guardian

Now that the weather is mild, pick up a copy of Anthony M. Sammarco’s latest richly illustrated history book, Beacon Hill Through Time. The 96-page work, on high-quality paper, is available from Arcadia Publishing at a list price of $23.99.

The book, with a mix of Peter B. Kingman’s expertly composed photos and a multitude of archival pictures, may surprise a lot of people.

Consider, for instance, how relatively late much of Beacon Hill was developed, considering that Boston was founded in 1630. The hill’s South Slope didn’t become the famously upscale residential area that people think of now until well after 1800, as the new wealth from the China Trade and other shipping, followed by fortunes made in manufacturing and finance, paid for grand mansions, brick and stone row houses and private clubs and other institutions.

There were some teardowns on the South Slope of a few older houses, most notably John Hancock’s mansion, built in the 1730’s and destroyed in 1863 to make way for an addition to the glorious Charles Bullfinch-designed Massachusetts State House (completed in 1798) at the top of the hill. Bullfinch, as architect and developer, is the father of Beacon Hill.

It’s basically a creation of the 19th Century, when the American public began to associate the hill (and then also the Back Bay) with the mercantile aristocracy to be called the “Boston Brahmins’’.

I was surprised to learn that many buildings I had thought were built in the late 18th or early 19th Century are actually decades newer. Architects have heavily used Colonial Revival and Federalist and 18th and 19th Century London residential styles right up to the present to maintain Beacon Hill’s antique appearance. Consider West Hill Place, where, Mr. Sammarco notes: “The design of these houses – with their high-style neoclassical details…made it seem as if London had been transplanted in Boston.’’

Then, as Mr. Sammarco explains, there were the waves of ethnic groups moving on and off the hill, along with various religious, political and other movements. For example, an African-American community developed early on the hill’s North Slope that created their own religious and other institutions, as did various Eastern European and other immigrants who followed. These flows led to such changes as, for example, a Black Baptist church being transformed into synagogue. Meanwhile, shops changed with neighborhood demographics as well as with the evolution of the broader consumer society.

You’ll see in the book how big, high-rise business buildings replaced lovely residential sections – sad but reflecting Boston’s wealth-creating capacity. Consider the elegant Pemberton Square before commerce took it over, late in the 19th Century.

Many direct most of their attention to the sights on the hill itself – e.g., Louisburg Square – rather than to the “Flat of the Hill’’ down by the Charles River and created by using fill from chopping off the tops of Beacon, Mt. Vernon and Pemberton hills (the “Tremonts’’). There are some gorgeous areas there, too, such as Charles River Square.

So you’ll probably want to plan several explorations with Mr. Sammarco’s book in hand. is

Robert Whitcomb is New England Diary’s editor and president of The Boston Guardian, where this piece first appeared.

View of John Hancock's house on Beacon Hill west of the summit from across the Common, 1768

Llewellyn King: The unfair social pressure to get a college degree

Corpus Christi College, part of the University of Cambridge

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

In case you don’t know, it is, the White House has announced, Older Americans Month.

They say, in the newspaper game, “Write what you know.” I find I know about being “older.” That sounds just a bit kinder than the bald “old.”

Chalmers M. Roberts wrote a wonderful book called How Did I Get Here So Fast?: Rhetorical Questions and Available Answers from a Long and Happy Life. Quite so.

I was the youngest at everything for a long time. I didn’t go to college, so I got a head start in journalism. Leaving school at 16 wasn’t then considered a life sentence of being second-rate. In those days and that place, Southern Rhodesia (now called Zimbabwe), a college education was a rarity; and people who had one were regarded as wise, even if they were stupid, as they frequently were.

There was a different social dynamic in London, where I launched myself on the legendary Fleet Street four years later. Few had been to college and those who had were regarded in the popular press not with reverence, as they had been in Africa, but with hostility. I was even hired at the BBC.

When a very nice man, Roger Wood, became editor of The Daily Express, there was consternation. He was a university graduate and, to make matters worse, from Oxford. The end of our hallowed way of life (phony expenses claims, heavy drinking and bad food) was at hand. En masse, the denizens of the newspaper world went to the pubs to mutter darkly about the imminent collapse of civilization. Change often is greeted with the sense that civilization is over.

Years later, I told Wood about the near-insurrection his appointment to the popular London newspaper’s editorship had caused. He was surprised. The discontent had never reached the editor's office.

In my next stop, New York, I was told, “No degree, no work.” At least not in television, and not at The New York Times. All three television networks wouldn’t grant me an interview even though I had been a scriptwriter at the BBC.

Perplexingly, The New York Times told me I could be an editor, but I could never hope to write in the newspaper because of my lack of a college degree. Go figure! You can’t write here, but you can fiddle with what others have written.

Despite this gaping hole in my past, I’ve managed and even pocketed an honorary degree along the way. I’ve lectured at a trove of universities, from Harvard and MIT to the University of Southern Mississippi. While, I think, for science there is no substitute for college, for the rest I’m less convinced.

These days, a heavy burden is put on people who don’t get at least two years of a college education, and an even heavier one on those who leave high school. Here, the language is indicative of the social stigma: You don’t “leave high school,” you “drop out.” That implies at a young age, a life going south, headed for repetitive failure.

The social pressure for an orthodox education is immense. The Biden administration, in its endless good intent, may be adding to the pressure on those who, for many reasons, took a different route in their lives. The role of the universities isn’t blameless. They have a predatory streak. They are as money hungry as any corporation, shaking down the alumni and justifying it with a moral superiority.

Treating formal education as the foundation of a social class is pernicious and destructive at all levels.

I used to fly light aircraft with a brilliant pilot -- the best I have ever known. But despite skills and knowledge far above average, he was precluded from getting hired by the airlines: He didn’t finish college, instead he went off to fly airplanes.

A scientist of real ability, a friend of mine, who climbed high in Big Pharma was sidelined not because she was a woman, but because she didn’t have a doctorate, only a masters; so she became an administrator.

Governments are right to emphasize learning. However, they need to demand thoroughness and excellence in the primary and secondary schools. Our public schools are a disgrace and damage children long before they decide whether they want to continue to college.

Now that I am an “older American,” I wouldn’t deprive anyone of a joyful life, as I have had, by limiting their opportunities with rigid orthodoxy about college. The university mission should be learning, not class branding. I was lucky. I dodged the branding industry, known as college.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

River view

A perfect day on Rhode Island’s mighty Seekonk River, at the upper end of Narragansett Bay

— Photo by Lydia Whitcomb

Sam Pizzigati: Biden’s Roosveltian tax-the-rich plan

Via OtherWords.org

BOSTON

President Joe Biden has made no secret of his admiration for Franklin D. Roosevelt. The president proudly displays a portrait of FDR in the Oval Office.

More significantly, he’s announced the most ambitious plan since FDR’s New Deal for enhancing the well-being of working Americans while trimming the fortunes of America’s super rich. The president has promised to fund his big plans for infrastructure, jobs and education entirely with taxes on the top.

In fact, Biden’s new tax-the-rich plan is a good deal more Rooseveltian than the numbers, at first glance, might suggest.

In 1945, when FDR died in office, the nation’s most affluent faced a 94 percent tax on income over $200,000, a little more than $2.9 million in today’s dollars. The rates Biden has proposed come nowhere near those — they’d top out at just 39.6 percent of ordinary income over $400,000. That’s up only slightly from the current 37 percent.

But the gap between Biden’s plan and FDR shrinks big-time when we toss capital gains — the dollars the rich make buying and selling stocks and bonds, property, and other assets — into the picture.

In 1945, the nation’s deepest pockets paid a 25 percent tax on their capital-gains windfalls. Today’s rate tops off at 20 percent. For households making over $1 million in annual income, the Biden plan would raise the top capital- gains tax rate to 39.6 percent, the same top rate that applies to earnings from employment.

In other words, the Biden tax plan ends the most basic tax break for the ultra rich: the preferential treatment they get on the income from their wheeling and dealing. This would be a big deal. In 2019, 75 percent of the benefits from the capital-gains tax break went to America’s top 1 percent.

Dividends currently get the same preferential treatment. Americans making over $10 million in 2018 took in over half of their total incomes — 54 percent — via capital gains and dividends. If Congress adopts the Biden tax plan, the basic federal tax on that 54 percent would just about double, from 20 to 39.6 percent.

The Biden plan also totally eliminates the federal tax code’s open invitation to dynastic family wealth: the “step up” loophole. Under this notorious giveaway, any fabulously wealthy American sitting on unrealized capital gains can pass those gains onto heirs tax-free. The Biden plan short-circuits the simplest route to dynastic fortune.

Under Biden’s tax plan, new dynastic fortunes would have a much harder time taking root. Already existing dynastic fortunes, on the other hand, would still be with us. Biden — like FDR in his day — has not yet warmed to the idea of a wealth tax.

Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren led a recent hearing highlighting the enormous contribution that even a 2 percent annual tax on grand fortunes could make. Among the insightful witnesses at the hearing: the 61-year-old Abigail Disney, the granddaughter of Roy Disney, the co-founder of the Disney empire with his brother Walt.

“I can tell you from personal experience,” Abigail Disney told senators, “that too much money is a morally corrosive thing — it gnaws away at your character… It warps your idea of how much you matter, and rather than make you free, it turns you fearful of losing what you have.”

Franklin Roosevelt understood that debilitating dynamic well enough to propose, in 1942, a 100 percent tax on annual income over what today would be about $400,000. Biden hasn’t ventured anywhere close to that level of daring. But he’s certainly come much further than anyone could reasonably have expected.

Sam Pizzigati is the Boston-based co-editor of Inequality.org and author of The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win.

Frank Carini: When you let the sands shift naturally

Dunes on Napatree Point

WESTERLY, R.I.

In late October 2012, about a day after Superstorm Sandy’s initial surge battered much of southern New England’s coast, especially its open-ocean shoreline, Janice Sassi navigated her way through a parking lot here filled with “mountains of mud” to find a “moonscape.”

“The dunes were completely flat,” recalled Sassi, manager of the 86-acre Napatree Point Conservation Area. “I thought it was done. It looked like one big beach.”

Sandy had ripped chunks of beachgrass from sections, and one area was forced back some 30 feet. At that moment and for days after, Sassi was concerned about Napatree Point’s future.

Her friend Peter August, a now-retired University of Rhode Island professor and a Napatree Point science adviser, put her racing mind at ease. The former director of URI’s Coastal Institute told her the resilient peninsula that offers sweeping views of Little Narragansett Bay, Block Island Sound, and New York’s Fishers Island would be fine. He reminded her that Napatree Point had previously survived one of the most destructive and powerful hurricanes in recorded history.

The hurricane of 1938, also known as the “Great New England Hurricane,” smashed the peninsula’s 39 2- and 3-story houses that stood just a few feet from the churned-up fury of the Atlantic Ocean. The 3- to 4-foot-high wall in front of those summer homes did nothing to prevent their destruction.

Storm waves broke over roofs and plowed “through the cement seawall as if it were transparent,” R.A. Scotti wrote in her 2003 book, Sudden Sea: The Great Hurricane of 1938.

“If you build on a barrier beach, you are toying with nature,” she wrote.

On the other side of the Napatree Point peninsula, most if not all of the private docks that extended into Little Narragansett Bay were reduced to kindling. Some residents waited out the 100-year storm in the remains of decommissioned Fort Mansfield. Fifteen people died.

The historic ’38 storm, much more so than Superstorm Sandy nine years ago, pummeled the 1.5-mile-long, sand-swept peninsula that curves away from the affluent village of Watch Hill. It severed the connection to Sandy Point, now a mile-long island shared by Rhode Island and Connecticut. In the eight decades since Sandy Point was left afloat, the island has drifted one and a half miles to the north.

More than a century earlier, Napatree Point, which was then densely forested — its name reportedly derives from nap or nape (neck) of trees — was significantly altered by another hurricane. The Great September Gale of 1815 “wiped it clean” and no tree has grown there since, according to Scotti’s book.

Following the hurricane of 1815, Napatree Point was significantly developed, and saw the construction of a boarding house and a hotel. By the end of the century, construction of Fort Mansfield had begun.

Though Sassi, then less than three years into her job after a career in law enforcement, was initially skeptical of August’s reassurances that her beloved Napatree Point would rebound, she’s thankful it did. She said it took about five years for the conservation area to completely repair itself. The beachgrass regrew, and the dunes regained their elevation.

Napatree Point was able to heal itself because humans have given it room to breathe. After the ’38 hurricane, one of the most financially destructive storms on record, developers looking to rebuild the summer cottages and construct other structures were rebuffed.

With no roads, homes, and hardened structures obstructing Mother Nature, Napatree Point has been allowed to change with the times. August noted that the barrier beach has the space to continually wash back over itself.

“It doesn’t erode away. It just moves,” said August, who founded URI’s Environmental Data Center three decades ago. “Napatree Point was 80 acres when the hurricane of ’38 struck; it’s 80 acres now, just in a different place. Napatree Point will always be here. It rolls with the punches. It gets changed but still exists.”

The Hope Valley resident said the geology of Napatree Point is a perfect example of how a barrier dune ecosystem works naturally. He explained that when Napatree Point is hit by big storms, such as the Great New England Hurricane or Superstorm Sandy, and wave action and tidal surge punch through the dunes, it creates wash-over fans on the backside, meaning the position of the peninsula’s dunes change; they aren’t lost.

“They’re rolling over themselves and they can do that because we’re letting the sand go where the sand wants to go,” August said.

Napatree Point is owned, managed and protected by a partnership of different interests: the Watch Hill Fire District, the Watch Hill Conservancy, which employs Sassi, the Town of Westerly, the state, and a few private landowners. Conservation easements protect it from future development.

In the summer, this slender strip of land — the average width is 517 feet — at the mouth of Little Narragansett Bay, where the Pawcatuck River empties into Block Island Sound, is overrun with tourists, boaters, beachgoers, hikers, anglers and nature observers. Finding a scrap of beach can be difficult, and some areas are roped off for important visitors, most notably piping plovers and American oystercatchers, both of which nest in the sand.

Sassi is thrilled that Napatree Point is so popular, but all the human visitors have an accumulating impact on the peninsula’s delicate dune system. The West Warwick, R.I., resident noted that the fact there is no development makes it easier for the small peninsula to defend itself from a changing climate and human intrusion.

The conservation area, however, isn’t immune to sea-level rise and other stressors associated with the climate crisis. About three years ago, Sassi and August began noticing that the entrance to Napatree Point, through a large parking lot off Bay Street that is lined with boutique shops and a mix of culinary options, began to flood during extremely high tides.

It’s now beginning to flood even during normal high tides. As sea levels rise and more frequent flooding occurs, access to the peninsula, at least via land, will become more and more restricted unless something is done. August said plans are underway to elevate the entrance, which laps up against Watch Hill Harbor.

Napatree Point is a barrier beach that has been shaped and reshaped by storms, sometimes profoundly, as was the case 206 years ago, 83 years ago, and nine years ago. The peninsula is composed of more sand than soil and its shoreline is worked upon daily by ocean waves and the tide. Like most barrier beaches, especially those with no human-made structures, Napatree Point is constantly in a state of flux. Since 1939, it has shifted north, toward Little Narragansett Bay, some 200 feet, according to mapping by the Coastal Resources Management Council.

The peninsula, however, is much more than a summer destination and a birdwatcher’s paradise. It’s also a habitat provider and a storm protector.

This fragile yet pliable barrier beach helps protect Westerly’s mainland. And to help protect Napatree Point’s dynamic ecosystem — and, thus, tourist-friendly Watch Hill — from storm surge, coastal erosion, and human visitors, a number of restoration projects have been undertaken.

During the past dozen years, some 4,000 native plants, such as seaside goldenrod, beach plum, swamp milkweed and groundseltree, have been added to help anchor Napatree Point’s shifting sands — their dense root mats keep erosion in check — and to attract pollinators.

Split-rail fences have been erected and signs posted to keep visitors and their wheeled coolers from making their own paths from the peninsula’s protected side to its open-ocean side. At one point several years ago, 50 crossover paths had been plodded through Napatree Point’s dunes and vegetation. Dinghies and Zodiacs land on the Little Narragansett Bay/Watch Hill Harbor side, before their occupants traverse the peninsula to the Atlantic Ocean side, where they lie in the sun, swim, and bodysurf.\

This tireless restoration work piloted by Sassi, August, Hope Leeson, Bryan Oakley and others has made Napatree Point a national model for stewardship, an important distinction since the area caters to an abundance of life, including mussel beds, bats, minks, foxes, deer, monarch butterflies, and a plethora of birds.

Off its coast are some of the biggest and healthiest eelgrass beds in Rhode Island waters. These vital marine ecosystems provide foraging areas and shelter to young fish and invertebrates, spawning surfaces for sea life, and food for migratory waterfowl. Gray and harbor seals hang out on the open-ocean side of the peninsula. In the winter, rafts of sea ducks are a common sight in the waters off the peninsula.

The Audubon Society has recognized Napatree Point as a globally important bird area. Veteran Rhode Island birder Rey Larsen has identified more than 300 different species of birds on the sandy, wind-swept peninsula.

The Napatree Point lagoon, about 3.5 feet deep in the middle, is home to a half-dozen different kinds of fish, including the American eel. It’s also an important horseshoe-crab nursery. The entrance to the 10-acre lagoon, from Little Narragansett Bay, is the peninsula’s most rapidly changing part, according to August. He said the entrance to the lagoon has moved a few times during the past decade alone.

Napatree Point, unlike much of Rhode Island’s built-up coastline, is better positioned to handle the climate crisis because humans are allowing its sands to shift naturally.

“The most important thing we can do is get people excited about Napatree Point so they want to protect it,” Sassi said.

For a wealth of science, stewardship, and monitoring information about the Napatree Point Conservation Area, click here.

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI News.

Watch Hill and Watch Hill Cove from the eastern end of Napatree Point

‘A sense of ocean and old trees’

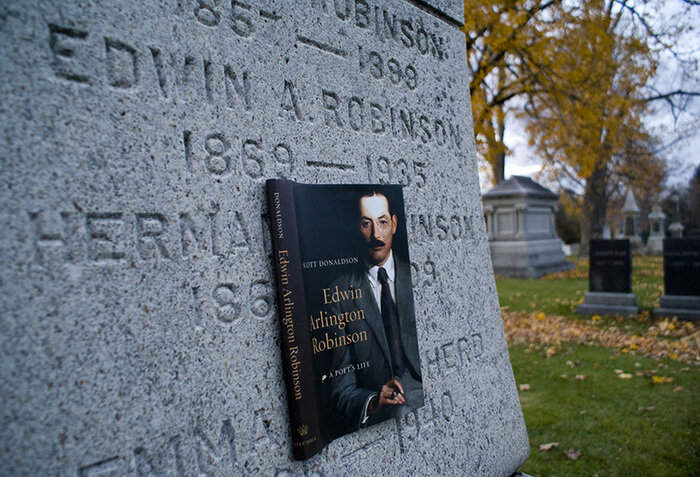

“Edwin Arlington Robinson (1916),’’ by Lilla Cabot Perry, in the Colby College Special Collections, Waterville, Maine

She fears him, and will always ask

What fated her to choose him;

She meets in his engaging mask

All reasons to refuse him;

But what she meets and what she fears

Are less than are the downward years,

Drawn slowly to the foamless weirs

Of age, were she to lose him.

Between a blurred sagacity

That once had power to sound him,

And Love, that will not let him be

The Judas that she found him,

Her pride assuages her almost,

As if it were alone the cost.—

He sees that he will not be lost,

And waits and looks around him.

A sense of ocean and old trees

Envelops and allures him;

Tradition, touching all he sees

Beguiles and reassures him;

And all her doubts of what he says

Are dimmed with what she knows of days—

Till even prejudice delays

And fades, and she secures him.

The falling leaf inaugurates

The reign of her confusion;

The pounding wave reverberates

The dirge of her illusion;

And home, where passion lived and died,

Becomes a place where she can hide,

While all the town and harbor side

Vibrate with her seclusion.

We tell you, tapping on our brows,

The story as it should be,—

As if the story of a house

Were told, or ever could be;

We’ll have no kindly veil between

Her visions and those we have seen,—

As if we guessed what hers have been,

Or what they are or would be.

Meanwhile we do no harm; for they

That with a god have striven,

Not hearing much of what we say,

Take what the god has given;

Though like waves breaking it may be,

Or like a changed familiar tree,

Or like a stairway to the sea

Where down the blind are driven.

“Eros Turannos,’’ by Edwin Arlington Robinson (1869-1935), who was born in the Alna, Maine, village of Head Tide, but grew up — generally unhappy — in Gardiner, Maine. The three-time winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry spent much time at the famous McDowell Colony, an artist residency in Peterboro, N.H. He died in New York and is buried in the family plot in Oak Grove Cemetery in Gardiner.

Gardiner’s Park and Palmer Fountain in 1909. Melted down for the World War I war effort, the bronze statue was later replaced.

Safely anonymous nudity

'‘Finsta Self’' (oil on paper), by Eben Haines. at the Corey Daniels Gallery, Wells, Maine

Don Pesci: The City Mouse fatalistically faces the spreading stupidity pandemic

1912 Drawing derived from the Aesop’s Fables tale “The Town Mouse and The Country Mouse,’’ by Arthur Rackham

VERNON, Conn.

The merry month of May has burst upon Connecticut. The City Mouse went to lunch in Hartford with one of her lady friends – sans mask, while they were eating – and a conversation arose concerning the age-old quarrel between city and country.

The City Mouse is a no-nonsense character, a quality disappearing quickly in our homogenously progressive Connecticut culture -- Connecticulture? -- and differences of opinion clouded the air.

The City Mouse was not surprised that Yale law students had launched a lawsuit against a wealthy suburb because, the students asserted, Woodbridge had, through its zoning regulations, frustrated the construction of low-rent housing in what had been historically a predominantly middle-class municipality. If the suit were to be decided in favor of the Yale students, a certain percentage of low-income housing would be required in all Connecticut municipalities, not solely in Woodbridge.

“Law students will be law students,” the City Mouse said, “but the zoning regulations in Woodbridge are not racist. They regulate lot size, which has attracted middle-class homeowners to Woodbridge. How many Yale students finding employment opportunities in Connecticut’s Gold Coast, or in an increasingly impoverished New York City, have over the past few decades settled in Woodbridge rather than, say New Haven? How many of New York's tax-tortured residents have moved to New Haven rather than Woodbridge or other Connecticut Gold Coast communities? The students’ attack upon zoning regulations in Woodbridge is what it appears to be on its face – an assault upon representative municipal governance first by the courts and, at some point in the near future, by a compliant progressive legislature.”

Their server, Brian, approached to refill their wine glasses. He was a young man – well educated, both could see – who was working his way through college. He had been at a Connecticut university for a couple of years, gliding through on a partial scholarship, and both had talked with him at length before.

“Brian,” Lady Friend said, “your restaurant appears to be reviving now that Coronavirus restrictions have been lifted. Good for you, right?”

“Yes. There’s plenty of work. But a different problem has cropped up.”

“Ah,” Lady Friend asked, “What is it?”

This question caused some unease. Brian, suitably masked, looked cautiously over his shoulder, then ventured in a whisper, “The restaurant is having a problem securing help.”

“From state and federal government, you mean?”

“No, everyone there wants to undo the harm they’ve done through shutdown regulations. Help… you know, servers, dishwashers and the like.”

Looking conspiratorially over her shoulder, The Country Mouse said, “Well, no slur intended on you, Brian, but you don’t need a Harvard education to serve food and wash dishes. And there is a huge untapped, unemployed population in Hartford that has not graduated from Yale or Harvard law schools and may be tapped to work in restaurants -- so, what’s the problem?”

“They have other means.”

“I don’t understand,” said Lady Friend.

And here, the City Mouse broke in. “Brian is suggesting that welfare payments and superior benefits keep the unemployed on the public payroll.”

“Is that it?” Lady friend asked, a note of quiet desperation in her voice.

“That’s it,” Brian said, and sped off to another table.

“I can’t imagine,” the City Mouse said, with a sardonic trill in her voice, “what the solution to that problem might be, apart from bringing restaurants onto the public dole. State support of restaurants could be sold on the supposition that restaurants might be better managed by legislators rather than restaurant owners. But you and I know -- don’t we? -- that it would drive up the cost of everything. Just look at the spikes over the past five decades in welfare costs, state employee salaries and pensions and so called ‘fixed costs,’ which cannot legislatively be unfixed without unseating certain legislators.”

“Imagine that,” said Lady Friend, “you solve one problem, and another knocks you on the head.”

“Like sowing dragon’s teeth,” the City Mouse mused.

The problem has been solved, I reported to The City Mouse. On May 3, the Hartford City Council proposed an equitable solution: “City exploring universal basic income.”

The lede to the story in a Hartford paper ran as follows: “The city of Hartford is considering experimenting with a universal basic income [UBI], starting with designing a pilot program that would give no-strings-attached monthly payments to participating city residents.”

The program would “target single, working parents, with a goal of learning whether extra, guaranteed income improves recipients’ physical and emotional well-being, job prospects and financial security.”

The lessons apparently already have been learned by the City Council.

The story bulges with approving quotes from a University of Connecticut economist, the council president, various council members, all Democrats, and a solitary Working Families Party member. Those outside Connecticut should know that the state’s Working Party lives in the basement of the state’s progressive Democrat Party.

A 2018 study of a similar UBI program in Alaska, the paper reported, found that “it did not increase unemployment as some critics feared and had actually increased part-time work.”

“So, no need to worry anymore,” I teased The City Mouse.

Her response, delivered with a painful sigh: “If only stupidity were as easy to dispose of as Coronavirus.”

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

Summer as verb

View of summer houses in Hampton Bays, on Long Island

— Photo by Masterchief1307

“When I left the State of Maine for college, I met my first really rich friends, and I discovered summer could be a verb.’’

— Alexander Chee (born 1967 in Rhode lsland but spent much of his youth in Maine), novelist, poet and nonfiction writer. He now teaches at Dartmouth College.

They come and they go and they come back

2020 U.S. Census enumerator’s kit

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary’’ in GoLocal24.com

The 2020 U.S. Census figures, in general, weren’t surprising. Population growth slowed to 7.4 percent in the stretch since 2010, the lowest since the Great Depression, when the population only rose 7.3 percent. The Sunbelt continued to draw many new residents, though not as fast as most demographers had predicted. So the Sunbelt’s megastates – Texas and Florida – picked up congressional seats – Texas two and Florida one; the economic dynamo North Carolina also got one new seat. (I don’t include California in the Sunbelt. It lost a seat.)

The big news around here (which surprised me) was that Rhode Island held onto enough people to retain its two congressional seats. Massachusetts will keep its nine seats and Connecticut its five. I attribute much of Rhode Island’s minor triumph to the great wealth-and-job-creation machine of Greater Boston, which spills into Rhode Island.

The Census data let New England maintain its 21 seats in the U.S. House, where for the first time in a half-century none of the region’s six states lost a seat!

Indeed, I wouldn’t be surprised if the more attractive and prosperous parts of the North, especially New England, see substantial population increases in the next decade as the Sunbelt problems cited below lead to some reverse migration, spawned by our relatively moderate weather (and lots of freshwater) and our rich technological, health-care and education complexes, beauty, generally low crime rates and sense of community and history. In any event, I doubt that the population of the country as a whole, or the economy, will surge in the Twenties, which unlike the last century’s Twenties, probably won’t be “roaring’’ for long. The demographics, including our low birth rate, don’t suggest a long-term national boom (or crash) is coming.

The assumption has been that the Census data will give the increasingly far-right Republican Party yet more clout. Maybe in the short run, but the folks moving into Sunbelt states from the Northeast, Rust Belt and California include many liberals who continue to want the sort of Democratic Party-promoted public services they had back north and in California. Thus, especially in Sunbelt metro areas, Democrats are fairly steadily increasing their share of the electorate. Strange political times! The Democrats have been moving toward European-style social democracy while parts of the GOP embrace neo-fascism.

The migration to the Sunbelt, although it’s slowing, is putting ever-increasing strains on its states’ generally thin social services and inadequate public infrastructure, as witness the Texas power-grid collapse in February.

The Sunbelt increasingly faces the heavy traffic, soaring home prices and other aspects of density that metro areas of the Northeast and California have long had to deal with. Addressing them will require major political and policy changes. The low taxes (except sales taxes), cheap real estate and wide open roads will not continue in large parts of the Sunbelt.

And this comes as the South faces the nation’s worst effects (with the possible exception of California) of global warming – including stronger hurricanes and other storms, more floods, more droughts and longer heat waves. God help Florida and the Gulf Coast as the seas keep rising.

The climate crisis has already turned away some people from the South, even as it requires very expensive infrastructure work to address. That means higher taxes, which the GOP hates more than anything else, especially when they’re imposed on the wealthy. The two most important Republican constituencies are the very rich (many of them via inheritance) and rural and exurban voters.

So I think that the Sunbelt will become increasingly politically competitive. The Census figures strongly suggest that. And New England will do all right, with or without “climate refugees.’’

Going forward, the New England states would do well to cooperate in formulating tax and other policies so as not to cannibalize themselves in marketing the compact region to business and individuals, especially to those in the Sunbelt and the Mountain States, the other high-growth region, that might be having second thoughts about where they’ve moved to in recent years.

The joy of junk mail

“Fish” (detail), by Elif Soyer, in her show “Bycatch,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, May 5-30.

The gallery says:

“The work in ‘Bycatch’ began as Elif Soyer’s ongoing attempt to journal while repurposing mounds of unsolicited junk mail, layering the mundane over the mundane. Soyer says she recognized mid-way through hanging her previous shows, ‘Balance Due’ and ‘Daily,’ that this theme was one that she would keep drawing on while incorporating ‘refuse’ from previous projects. Paper, pencil, acrylic, cloth, string, tempera, pen, watercolor, junk mail, and bills produce textured and subtle imagery suggestive of, variously, lichen, ear canals, viruses, eyeballs, branches, phrases, fish, neurons and plants, familiar motifs from the artist’s canon.

“Says Soyer: ‘The materials, the drawing, writing, and painting are informed by the way I see: space filled with layers and layers, textures, forms and contrast yet always space - the eye takes in so much, the net captures what was not intentionally looked for as well as my original focus. My friends and family say that my untraditional aesthetic must be influenced by my bi-cultural Turkish/American upbringing, surrounded by mosaics, textiles, and tapestries rich in contrast. My bycatch collects clashing materials that co-exist just the same, and eventually manage to coalesce into their own environment.”’

Acting like idiots sells

Johnny Damon at bat for the Red Sox in spring training in 2005

“We’ve got the long hair, we’ve got the cornrows, we’ve got guys acting like idiots. And I think the fans out there like it.’’

— Johnny Damon, former outfielder for the Boston Red Sox, which he played for in 2002-2005

For an NRA meeting

“Still from 'Hand Catching Lead'‘ (two-color lithograph/screenprint), by Richard Serrra, in his show “Richard Serra: Selected Prints,’’ at Heather Gaudio Fine Art, New Canaan, Conn., starting May 8.

The gallery says:

“In collaboration with master printers Gemini G.E.L., the exhibition will include monochromatic works from different series executed in the last 15 years. Serra’s explorations with printmaking have been an extension of the artist’s practice of working in monumentally-scaled sculpture. Since 1972, he has been working with Gemini to create and invent new techniques in the medium, leading to a varied output of complexly surfaced prints.’’