Vox clamantis in deserto

David Warsh: The Blake Bailey case and the logic of woke

Blake Bailey in 2011

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

“Society is a game with rules, people are players in this game, and politics is the arena in which we affirm and change these rules. Unlike the rules in standard game theory, however, social rules are continually contested by players allying to scrap old rules and create new rules to serve their purposes.”

That framing, by Herbert Gintis, in the first paragraph of Individuality and Entanglement (2017), struck me as particularly apt when I read it. It’s been useful to me ever since in understanding matters large and small.

Take the case of Blake Bailey’s biography of the novelist Philip Roth, now withdrawn from print. Its publisher, W.W. Norton, returned the manuscript to the possession of its author, along with that of Bailey’s memoir, The Splendid Things We Planned, which Norton published in 2014.

Ten days ago, The New York Times reported that accusations of sexual assault and other bad behavior by Bailey, 57, had led the publisher to stop shipping and promoting the book, which had just that week reached the Times’s best-seller list.

Two days after that, Terry Pristin, a former reporter for The Times, in a letter published on the paper’s editorial page, wrote, “If Blake Bailey, Philip Roth’s biographer, is credibly accused of rape and attempted rape, let him be prosecuted to the full extent of the law. But why punish the rest of us? Don’t prevent me from reading a biography that no less a writer than Cynthia Ozick has labeled a ‘narrative masterwork.’”

The difference between the front-page treatment the story received initially, and the less prominent play, on page B4 in the business section, of the news that the publisher had taken out of print its editions of both books, reflected contesting opinions about the story’s significance, perhaps even within the newspaper. Then again, the second story, being a follow-up and so subsidiary to the first story, may have reflected nothing more than classic journalistic procedure.

Bailey has adamantly denied the charges.

The most interesting details had to do with the timing of the allegations, their nature, and the manner in which they were communicated to the publisher. Most of these were spelled out with clarity in The Times’s account.

It was apparently in 2018, that a publishing executive, Valentina Rice, using a pseudonymous email account, wrote to Julia A. Reidhead, the president of Norton, accusing Bailey of non-consensual sex three years earlier, when both had been overnight guests at the home of a Times book critic and his wife. She also emailed a Times reporter, who responded, but Ms. Rice decided not to pursue it further and did not reply.

“I have not felt able to report this to the police but feel I have to do something and tell someone in the interests of protecting other women,” she wrote to the publisher, adding: “I understand that you would need to confirm this allegation which I am prepared to do, if you can assure me of my anonymity even if it is likely Mr. Bailey will know exactly who I am.”

The publisher did not respond to her note, Rice told The Times. But a week later Rice received an email from Bailey, who said that Norton had forwarded her complaint.

“I can assure you I have never had non-consensual sex of any kind, with anybody, ever, and if it comes to a point I shall vigorously defend my reputation and livelihood,” he wrote in the email, which Rice shared with The Times, though it is not clear when. “Meanwhile, I appeal to your decency: I have a wife and young daughter who adore and depend on me, and such a rumor, even untrue, would destroy them.”

In other words, Rice wrote Norton just as the Me Too movement gathered steam. It was some months after The Times and The New Yorker had published the stories about powerful Hollywood sexual predators for which they were awarded the 2018 Public Service Pulitzer Prize.

What was the president of Norton thinking? What did Blake Bailey think to himself? What did the publisher and author think might or might not happen when the biography eventually appeared? Litigation and much shoe-leather reporting seem sure to ensue. We can hope that eventually a satisfying reconstruction will appear, along the lines of other careful post-mortems of furiously contested events: Sanford Ungar’s The Papers and the Papers: An Account of the Legal and Political Battle over the Pentagon Papers (1974); Janet Malcolm’s The Journalist and the Murderer (1990), about the strategies of authors dealing with sensational events (in this case, the murder of a Green Beret physician’s daughters and pregnant wife); Devlin Barrett’s October Surprise: How the FBI Tried to Save Itself and Crashed an Election (2020), about FBI decision-making in the last months of the 2016 presidential election. I should mention how proud I am that that Norton published my Knowledge and the Wealth of Nations: A Story of Economic Discovery (2006). Like many others, I consider the company to be among the very best in the industry.

In the meantime, the story of the Roth biography is one more illustration of how culture changes and why: social rules are contested by allies who, often successfully, seek to scrap old rules and create new ones to serve their purposes. Call me cynical, but I believe that the relevance of stories about movie mogul Harvey Weinstein’s predatory behavior was driven home by Donald Trump’s election to the presidency, despite plentiful evidence of his sexual misconduct. Heightened attention to racial inequities, exemplified by the Black Lives Matter movement, was stoked even more by the murder of George Floyd.

There are times when the law is not enough.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this piece first appeared.

Editor’s note: Roth lived for many years in Warren, Conn., in a 1790s farmhouse. For a look:

http://www.klemmrealestate.com/properties_details_pk.php?For%20Sale-2255

Bailey’s other books include {John} Cheever: A Life, about that great short-story writer and novelist, who though he lived most of his life in and around New York, never ceased to be a New Englander.

Frank Carini: The vast poisoning that goes with maintaining lawns

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

The amount of pollution, from noise to air to water, created to maintain green carpets and immaculate yards is jarring. Lawn mowers, weed whackers, leaf blowers, pesticides, herbicides, fungicides and fertilizers. Much of this effort is powered by or made from fossil fuels.

Lawn-care equipment is typically powered by two-stroke engines. They are cheap, compact, lightweight, and simple. They are also highly polluting, generating up to 5 percent of the country’s air pollution, according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Each weekend for much of the year, according to estimates, some 54 million Americans mow their lawns. All this weekend grass cutting uses some 800 million gallons of gasoline annually. That doesn’t include the gas used to trim around trees and fences and to blow grass clippings around.

Those 800 million gallons also don’t include the gas used for lawns mowed during the week or by landscaping companies. It doesn’t include the oil that is also burned by these cheap engines. It doesn’t include grass cut on golf courses and along median strips and other public spaces covered by green carpets devoid of diversity.

A 2011 study showed that a leaf blower emits nearly 300 times the amount of air pollutants as a pickup. The EPA has estimated that lawn care produces 13 billion pounds of toxic pollutants annually.

This equipment is also noisy. Leaf blowers emit between 80 and 85 decibels, but cheap or mid-range ones can emit up to 112 decibels. Lawn mowers range from 82 to 90 decibels. Weed whackers can emit up 96 decibels of noise.

Electric lawn equipment is gaining in popularity and will slowly lessen the amount of fossil fuels burned to cut millions of acres of grass — a 2005 study found that about 40 million acres in the continental United States has some form of lawn on it. Electric equipment is also quieter than its gas-powered counterparts.

Much of the 90 million pounds or so of fertilizer dumped on lawns annually are fossil-fuel products. Nitrogen fertilizer, for instance, is made primarily from methane.

As stormwater carrying nitrogen and phosphorus from fertilizer runs off into streams and rivers and eventually into larger waterbodies such as Narragansett Bay, it impacts ecosystems and fuels algal blooms, some toxic, that suck oxygen from water.

On Rhode Island’s Aquidneck Island, for example, stormwater runoff carrying these nutrients is stressing coastal waters and contaminating the reservoirs that feed the Newport Water System.

The amount of toxic chemicals applied to lawns and public grounds annually to jolt grass to life and kill pests is staggering. This copious amount of poison, about 80 million pounds annually, is marked by white and yellow flags warning us not to let children or pets onto these monolithic spaces whose appearance trumps their health and that of the surrounding environment.

These warning flags are planted because of the 30 commonly used lawn pesticides 17 are probable or possible carcinogens; 11 are linked to birth defects; 19 to reproductive impacts; 24 to liver or kidney damage; 14 possess neurotoxicity; and 18 cause disruption of the endocrine (hormonal) system. Another 16 are toxic to birds; 24 are toxic to aquatic life; and 11 are deadly to bees.

Of course, these poisons don’t just kill or harm their intended targets.

While these chemicals hang around “feeding your lawn” or killing life, they are breaking down and working their way into the environment — until another application is applied, sometimes just a few weeks later, and the cycle repeats.

Poisons from these artificial fertilizers and the various -cides applied to lawns can seep into groundwater — contaminating drinking-water supplies — or turn to dust and ride the wind. They cling to people and pets who walk, run, and lie on treated grass. They get kicked up during youth sporting events.

These chemicals can be inhaled like pollen or fine particulates, causing nausea, coughing, headaches, and shortness of breath. For asthmatic kids, they can trigger coughing fits and asthma attacks.

Two of the most common pesticides, glyphosate used in Roundup and 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) in Weed B Gon Max, have been linked to a number of health issues, including developmental disorders and cancer. The latter is a neurotoxicant that contains half the ingredients in Agent Orange, according to Beyond Pesticides, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit.

The Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) has called 2,4-D “the most dangerous pesticide you've never heard of.”

Developed by Dow Chemical in the 1940s, the NRDC says this herbicide helped usher in the green, pristine lawns of postwar America, ridding backyards of vilified dandelion and white clover.

Researchers have observed apparent links between exposure to 2,4-D and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and sarcoma, a soft-tissue cancer, according to the NRDC. It notes, however, that both of these cancers can be caused by a number of chemicals, including dioxin, which was frequently mixed into formulations of 2,4-D until the mid-1990s.

In 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer declared 2,4-D a possible human carcinogen.

Last year Bayer paid nearly $11 billion to settle a lawsuit over subsidiary Monsanto’s weedkiller Roundup, which has faced numerous lawsuits over claims it causes cancer.

Lawns are one of the most grown crops in the United States, but unless you are a goat or a dog with an upset stomach their nutritional value is zero. Yet the collective we continues to spend about $36 billion a year on lawn care.

Instead of putting public health at risk and degrading the environment with a chemically treated lawn, create a yard with a diverse mix of native trees, shrubs, and plants; it is cheaper to maintain, easier to take care of, environmentally beneficial, and more interesting.

Native plants support native wildlife and insects, are accustomed to the weather and soil, and are pest resistant. They support the pollinators of our food crops, clean the air and water, and help regulate the climate. They also make good natural buffers, which capture rainfall and filter stormwater runoff.

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI News.

The first gasoline-powered lawn mower, 1902

‘Burning into retinas'

Sugar maple in May

“Who knows

What it is that’s keeping the trees from appearing to us

The way they appear to the lifelong blind stricken

Unexpectedly with sight, blots and flashes of scarifying

green burning into retinas.’’

“Spring Morning,’’ by Tom Sleigh (born 1953), American poet and professor at Dartmouth College and elsewhere

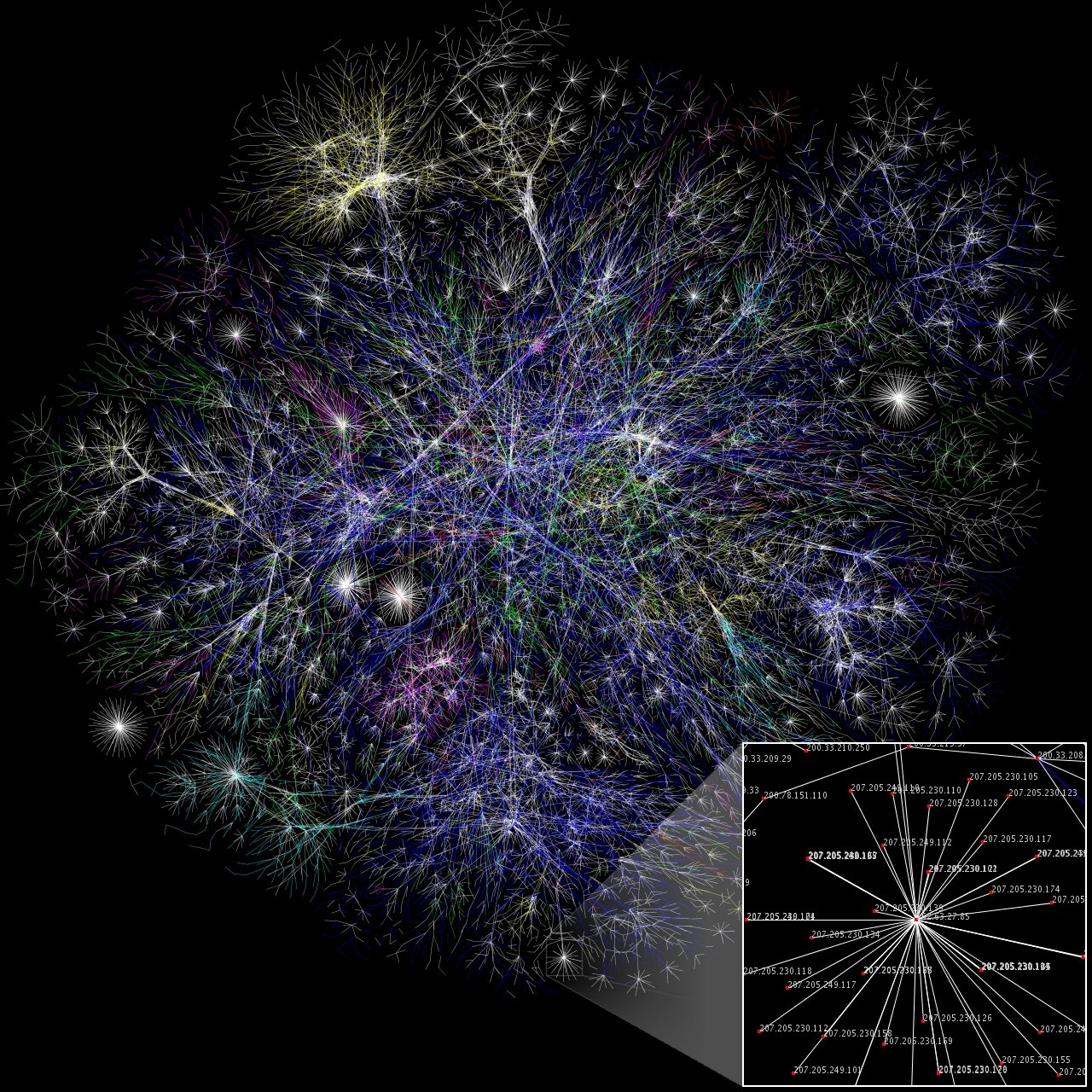

Llewellyn King: Interconnectivity at the heart of the revolution that’s upon us

Visualization from the Opte Project of the various routes through a portion of the Internet

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

When we look back on the convulsion that is going to reset America — the great technology-driven revolution that will extend to nearly every corner of American life — it may be named for President Joe Biden, but it won’t be his revolution. It is innovation’s revolution. He will help finance it and smooth it out, but it is already happening and is accelerating.

Biden’s typically soft speech to Congress (no stemwinder he) was a wish list of things dear to him, but also an acknowledgement of what already is in motion.

Technology is rampant and government’s role should be to provide partnership and, above all, standards, according to two savants of the tech world, Jeffrey DeCoux, chairman of the Autonomy Institute, and Morgan O’Brien, a visionary in U.S. wireless telecommunications, now executive chairman of Anterix, a company providing private broadband wireless networks to utilities. Above all, they said in an interview with me for the PBS program White House Chronicle, standards for the new technology are essential.

Partial interconnection with different appliances, from road sweepers to drone delivery vehicles speaking only to identical devices, will be self-defeating. The internet without international standards would have failed.

Biden is set to preside over the greatest industrial leap forward since steam provided shaft horsepower to make factories a reality. If Congress allows, the Biden administration will finance much of the upgrading of the old infrastructure. It also will be called upon to be part of the new infrastructure, the technological one. That will be expensive; both DeCoux and O’Brien warned that it will take huge sums of money to build out complete 5G broadband networks, which will carry the load of interconnectivity.

For the nation to leap forward, these networks need to bring 5G broadband to every corner of it, O’Brien said. It can’t be allowed to serve only those places where population density makes it profitable.

In his speech to Congress, Biden laid out a revolutionary abstract for the future of the nation. The human side of the Biden infrastructure plan -- things like day care, free community college, better health care, prescription drug pricing -- is the true Biden agenda.

The technology revolution is seen by the president not for what it is, a resetting of everything in America, but rather as a way to job creation. It will create jobs, but that isn’t the driving force. The driver is and has been innovation: science helping people. That, in turn, will bring about a surge of productivity and prosperity and with that, new jobs, quality jobs – robots will soon be flipping hamburgers and painting houses.

This other agenda, the one that will make the fundamental difference between the nation of today and the nation of tomorrow, is the technological revolution. The evolutionary forces for this upheaval have been gathering since the microprocessor started things moving in the 1970s.

At the core of the coming changes is interconnectivity. That is what will craft the future. Cars on highways will be connected with each other through thousands of sensors, and these will speed traffic and enhance safety both for those with drivers and new autonomous ones. Likewise, drones will deliver many goods and they will need to be interconnected and have superior flight management. Every aspect of endeavor will be involved, from managing railroads to increasing electricity resilience and the productivity of the electric infrastructure.

In an interview on the Digital Roundtable, a webinar from Texas State University, this past week, Arshad Mansoor, president of the Electric Power Research Institute, said improved interconnectivity could increase available electricity from dams and power plants often without new construction. He explained that interconnectivity wouldn’t only be essential to managing diverse generating sources, like wind and solar, but also in wringing more out of the whole system.

Technology has gotten us through the pandemic. Most obviously in the huge speed at which vaccines were developed, but also in our ability to meet virtually and the effectiveness of online ordering and delivery.

By nature, and by record, Biden is a get-along-go-along politician, a zephyr, as we heard in his address to Congress. But history looks as though it will cast him as a transformative president, a notable leader presiding over great winds of change.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Autopilot system in Tesla car

'Its own excuse for being'

Rhodora, a common flowering shrub of the New England

In May, when sea-winds pierced our solitudes,

I found the fresh Rhodora in the woods,

Spreading its leafless blooms in a damp nook,

To please the desert and the sluggish brook.

The purple petals fallen in the pool

Made the black water with their beauty gay;

Here might the red-bird come his plumes to cool,

And court the flower that cheapens his array.

Rhodora! if the sages ask thee why

This charm is wasted on the earth and sky,

Tell them, dear, that, if eyes were made for seeing,

Then beauty is its own excuse for Being;

Why thou wert there, O rival of the rose!

I never thought to ask; I never knew;

But in my simple ignorance suppose

The self-same power that brought me there, brought you.

“The Rhodora: On Being Asked, Whence Is The Flower,’’ by Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882)

Impressionist loyalty

“Spruce in Snow” (circa 1912, oil on canvas), by Alice Ruggles Sohier, in the show (with the work of Frederick A. Bosley) “Twilight of American Impressionism’’ at the Portsmouth (N.H.) Historical Society.

The two were painting at a time when realistic art was falling out of fashion in favor of more abstract art. Regardless, Sohier and Bosley painted impressionist works until their deaths, in the mid-20th Century.

Chris Powell: The best reason to raise taxes on the rich

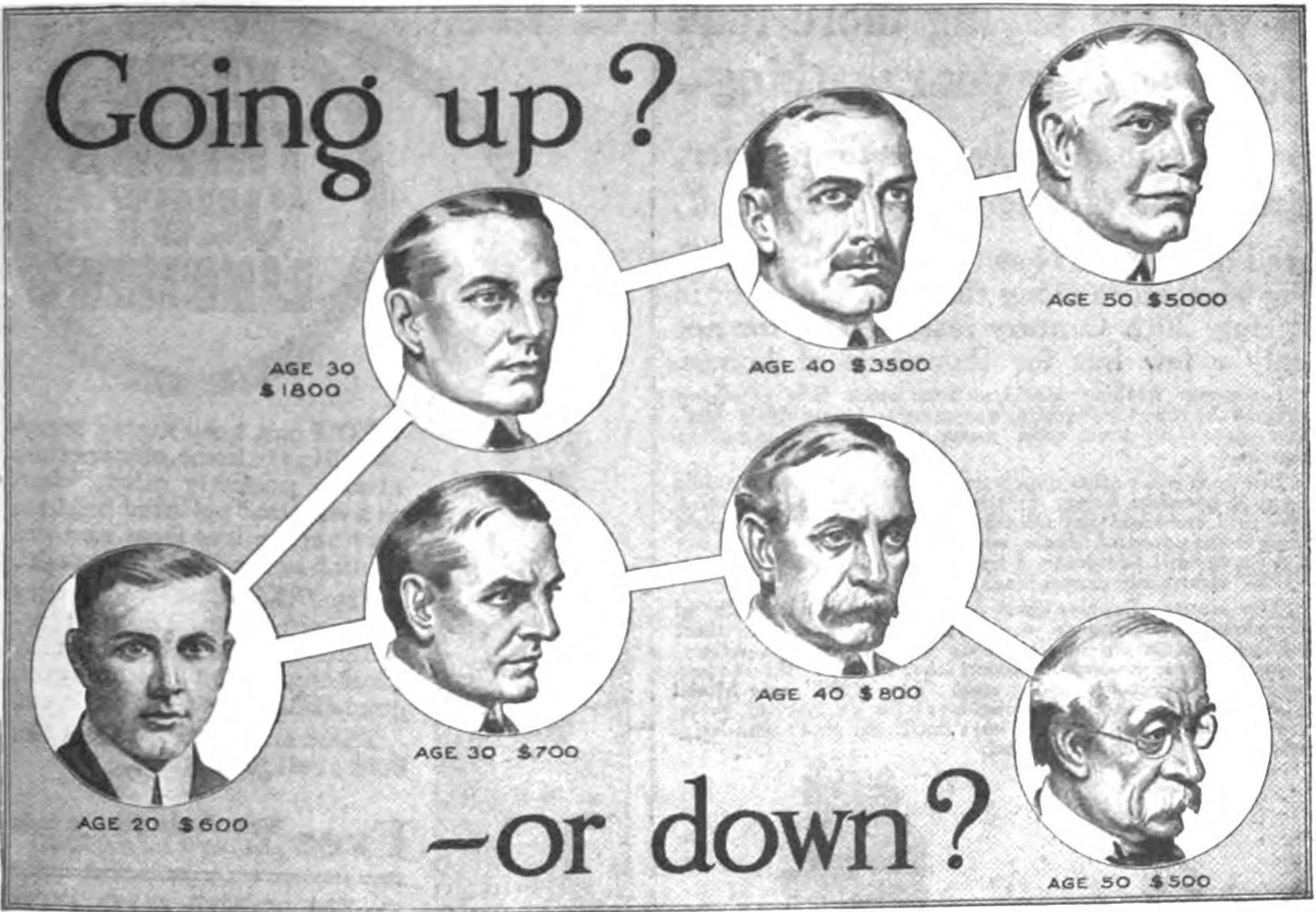

Illustration from a 1916 advertisement for a U.S. vocational school. Education has been seen as a key to higher income, and this advertisement appealed to Americans' belief in the possibility of self-betterment, and addressing the great income inequality existing during the Industrial Revolution.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

While there is a compelling reason to raise taxes on the rich, it's not the reason motivating many Democrats in the Connecticut General Assembly, who would increase both state income and capital-gains taxes on the rich and impose a special state property tax on their expensive homes.

These Democratic legislators want mainly to increase state government's political patronage, the compensation of government employees and the dependence of the poor on government. Connecticut's quality of life seldom improves from their legislation. The state's problems are never alleviated, much less solved, while state government keeps manufacturing poverty.

Besides, state government is already rolling in federal "stimulus" money, with $6 billion of it waiting to be allocated by Gov. Ned Lamont and the legislature. Properly allocated, that largesse should keep state government manufacturing poverty quite without any new taxes for years.

Nor is the reason offered by Democrats in Congress for raising federal taxes on the rich any good -- to increase the government's revenue.

For the virus epidemic already has pushed the federal government into implementing Modern Monetary Theory, which holds that government can create and disburse infinite money without levying taxes, constrained only by depreciation of the currency. The trillions of dollars recently created may go onto the government's books as debt, but that debt will never be repaid and instead will be monetized by the government's purchase of its own bonds. Indeed, as MMT notes, the debt is already treated as money when it is in private hands.

As anyone who goes grocery shopping, puts gasoline in his car and pays electricity, insurance and tax bills knows, inflation is already roaring and making a joke of the official price data.

The single compelling reason to raise taxes on the rich is to diminish income inequality a little after it has been increased so much by the federal government's policy of inflating asset prices during the economic depression caused by the epidemic -- a policy of directing far more money to the financial markets and thus to the ownership class, people who own stocks and bonds, than to the laboring class, tens of millions of whose members lost their jobs because of government policy and crashed into poverty.

But this effort to reduce wealth inequality should be undertaken at the federal level, not by state government in Connecticut -- at least not yet. That's because Connecticut is already a high-tax state whose economy has been weak for many years, and raising state taxes would disadvantage Connecticut even more relative to other states.

Money will go where it is treated best, and until the dislocations of recent months that drove thousands of people out of the New York City area, Connecticut was losing population relative to the rest of the country, losing mainly the prosperous people who pay taxes.

Connecticut's effort to reduce wealth inequality should concentrate on reducing the poverty the state manufactures with its welfare and education policies.

xxx

Many people in Connecticut, including some state legislators, argue that medical care is or should be a human right and that, as a result, state government should extend Medicaid insurance to the tens of thousands of people living in the state illegally. The cost is estimated at nearly $200 million per year.

These people are not entirely without medical care. They can pay for it themselves or present themselves at hospital emergency rooms when they are sick or injured and hospitals must treat them for free if they are indigent.

Of course, such medical care falls far short of comprehensive. But if comprehensive medical care is a human right, is living in Connecticut a human right too? If so, most people in Central America might insist on living in the state. Extending Medicaid to immigration lawbreakers would be a powerful incentive for more lawbreaking, which is already rampant.

So in addressing the Medicaid extension issue, Connecticut can't help addressing the illegal immigration issue as well. Extending Medicaid will be, in effect, more nullification of federal immigration law, just as the state's pending legalization and commercialization of marijuana, sensible as such policies may seem, will be more nullification of federal drug law.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn

Trying to save what we inherited

The "grass ramp" from the entrance to the lily pond at the Connecticut College Arboretum

“What I have done in life has not been motivated by an effort to save myself from unpleasant experiences in the next, but rather, at least in part, by a desire to preserve the beauty and biological integrity of the earth we have inherited.’’

— Richard H. Goodwin (1910-2007), botanist and conservationist, co-founder and twice president of The Nature Conservancy and long-time professor and director of the arboretum at Connecticut College, in New London

—

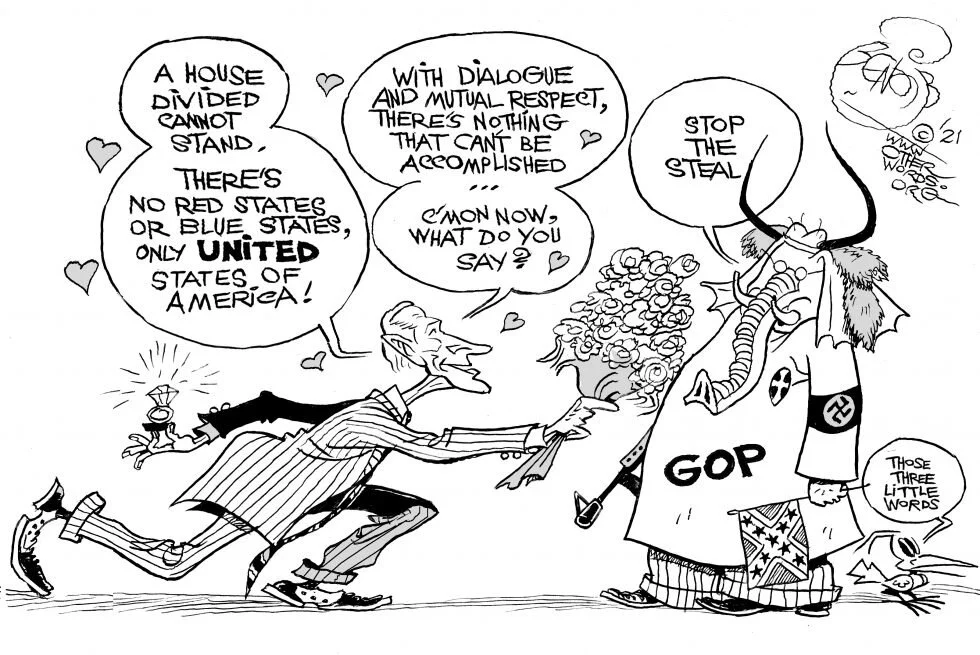

George McCully: America’s crisis of knowledge

Pinoccchio

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

There has been a growing consensus among authorities, especially in the Trump era, that the U.S. is in an epistemological crisis that threatens our democracy.

Former President Obama, for example, in a recent Atlantic interview, said: “If we do not have the capacity to distinguish what’s true from what’s false, then by definition the marketplace of ideas doesn’t work. And by definition, our democracy doesn’t work. We are entering into an epistemological crisis.”

If this is true, it is an issue which the academic and journalistic communities—i.e. those in charge of the public’s knowledge and education nationwide—need to address.

There are plenty of indications that Obama was right. The 2020 election intensified this awareness. David Brooks, in his New York Times column of Nov. 27, wrote that “77 percent of Trump backers said Joe Biden had won the presidential election because of fraud. Many of these same people think climate change is not real. Many of these same people believe they don’t need to listen to scientific experts on how to prevent the spread of the coronavirus. We live in a country in epistemological crisis, in which much of the Republican Party has become detached from reality.”

On that same day, Michael Gordon, in an op-ed for The Washington Post, wrote: “Journalism is important, and there should be more of it. An informed electorate, in the long run, will have better democratic outcomes. But the urgent problem of American politics is not an insufficient airing of policy disagreements; it is that policy views have become a function of cultural identity. A matter such as climate disruption, for example, attracts comparatively little informed and reasoned disagreement. Climate skepticism has become a tenet of populism—a revolt against elitist scientists and liberal politicians seeking excuses for social and economic control. The denial of climate change has become a cultural signifier, the policy equivalent of a gun rack in a truck.”

Multidimensional crisis

The crisis has several dimensions beyond the intellectual one. Robin Givhan, in her Washington Post column on Feb. 17, 2021, reported: “Surveys have shown that political polarization along educational lines has deepened. The gap between college-educated voters and non-college-educated voters has grown steadily over the past 60 years. The 2020 presidential election hinged on the diploma divide, which in turn, contributes to differences in income, household wealth, jobs, place of residence, cultural values and access to opportunity. … For the past four decades, incomes rose for college degree holders even as they fell for those without one, generating frustration, resentment and anger. With nearly three-quarters of new jobs requiring a bachelor’s degree, excluding nearly two-thirds of adults, earnings are linked to learning in ways that weren’t true during the 1950s and 1960s.”

There is also a technological dimension. Whereas it used to be thought that the internet would enhance democracy, we have seen an opposite effect. Thomas Edsall, in The New York Times, also on Feb. 17, wrote that “a decade ago, the consensus was that the digital revolution would give effective voice to millions of previously unheard citizens. Now, in the aftermath of the Trump presidency, the consensus has shifted to anxiety that such online behemoths as Twitter, Google, YouTube, Instagram and Facebook have created a crisis of knowledge—confounding what is true and what is untrue—eroding the foundations of democracy.”

Nathaniel Persily, a Stanford University law professor, summarized the dilemma in his 2019 report, “The Internet’s Challenge to Democracy: Framing the Problem and Assessing Reforms.” He wrote that “in a matter of just a few years the widely shared utopian vision of the nternet’s impact on governance has turned decidedly pessimistic. The original promise of digital technologies was unapologetically democratic: empowering the voiceless, breaking down borders to build cross-national communities, and eliminating elite referees who restricted political discourse. Since then that promise has been replaced by concern that the most democratic features of the internet are, in fact, endangering democracy itself. Democracies pay a price for Internet freedom, under this view, in the form of disinformation, hate speech, incitement and foreign interference in elections.”

He continued, “Margaret Roberts, a University of California-San Diego political scientist, says bluntly, ‘The difficult part about social media is that the freedom of information online can be weaponized to undermine democracy.'” In an email to Edsall, she wrote, “Social media isn’t inherently pro[-] or anti-democratic, but it gives voice and the power to organize to those who are typically excluded by more mainstream media. In some cases, these voices can be liberalizing, in others illiberal.” We are reminded that while Franklin Roosevelt used radio for fireside chats to promote his liberal agenda, Hitler was using it to promote his fascism.

Today, the new technology is more dangerous, because with AI, it becomes progressively easier to disguise mis- or disinformation as authentic news, and to scrape data from users’ devices to then target the citizens most likely to be vulnerable to dissuasion. Training in “media literacy” or how to discern authentic from fraudulent communication especially on the web, has been a growing field for decades, and will continue to be so as technology advances. But communications techniques and evaluation of sources are less our concern here than epistemology per se, and, in particular, reliance upon trusted sources, which most people use as their criterion for recognizing truth.

The truth is out there?

What is to be done? First, let us understand that the principal constituency bearing civic responsibility for the health and welfare of public intelligence, has to be scholars and educators, including journalists; and that in these roles, our professional and technical focus must be less on the economic, technological or even psychological and moral dimensions of the epistemic (i.e. relating to knowledge) crisis than on its epistemological (i.e. the study or science of knowledge) core.

We notice that the journalistic discussions quoted above focus on trust as the main issue—i.e., whom people should or want to believe in matters of science, public policy or politics and how trustworthiness has been subverted by political, economic and technological developments. While it is probably true that this is how most people actually know and think, as scholars we do not and, in fact, are trained not to trust even one another, because trust is an invalid and unreliable criterion of truth. From our professional perspective, public trust itself is intrinsic to the public’s epistemological crisis.

Another intrinsic element of that core obviously is inadequate factual knowledge or sheer ignorance of how and why our government works. On our watch over the past 50 years, there has been a steady erosion in the teaching of civics and history. While we spend about $50 per student annually on science and math education, only about five cents is allocated to civics education. Ten states currently have no civics requirement in schools. Large numbers of Americans cannot even name the three branches of government, never mind the value for democracy of checks and balances, or how elections are essential for peaceful transfers of power. This past year we have seen how misunderstanding of governmental politics has fed distrust, non-participation and polarization. The federal government is aware of this and has developed a purportedly high-quality K-12 civics and history program called “Educating for American Democracy,” but it has not been funded for implementation. While this initiative might help to address the knowledge issue,it does not address the crisis in epistemology—confusion about how to know and recognize truth.

Many years ago, on my first day at Brown University, the freshman class assembled in Sayles Hall to be welcomed by the university’s president, Barnaby Keeney (later the founding director of the National Endowment for the Humanities). He told us that one of the most essential and valuable skills we would learn in college—central to every scholarly discipline as the most reliable way to think about the world—was “to think on the basis of evidence.” That simple phrase—this was the first time I had heard it—blew me away, and has stuck with me for life.

Several years later, while studying history in graduate school at Columbia University, I recall discussions we often had with fellow students in one of the nation’s leading schools of journalism. They were being taught to build their stories around “balance” among various contending points of view, as a “fair” way to report to the public on current events. We history students considered this absurd, ridiculous and misleading to the public, implying that all points of view are equally valid and significant. We were right, but we see today that “balance” has set the modern standard in journalism, still practiced and still, as predicted, pernicious and dangerous. I have been amazed at how leading journalists these days struggle to articulate the challenge of ascertaining truth, treating it as discovering whom to trust. They rarely use the word “evidence”—a rare exception is Lester Holt of NBC Nightly News, who said recently in accepting the Edward R. Murrow Award for Lifetime Achievement in Journalism, “I think it’s become clearer that fairness is overrated,” and he advocated that reporters not give “unsupported arguments” equal coverage.

Follow the evidence

About the only venue where “evidence” has been determinative in current politics is our court system, wherein attempts by Trumpists to quash results of the last presidential election on grounds of corruption were summarily rejected by 63 courts at all levels nationwide for their total “lack of evidence.” The words were quoted by reporters of those decisions, and gradually the criterion of “evidence” has begun to be used comfortably by leading journalists, though we do not know if they appreciate its epistemological value—in fact, necessity in determining truth.

But the health of our democracy cannot safely rely solely on our judiciary and the best of journalism, which brings us back to the issue of our proper civic responsibilities, as scholars and teachers, for the health of public thought and discourse. What can we do to help resolve our national epistemological crisis, to protect our democracy?

First, we need to promote, for all courses and disciplines in all colleges and universities, explicitly and emphatically, that the best—i.e., surely, most reliable—way to think about the world is “on the basis of evidence.” We must work to help make it consciously automatic and habitual for all who are in or have been to college.

Second, and this is critically important, there is no reason “thinking on the basis of evidence” cannot also be taught as the explicit standard and simple lesson throughout secondary schools nationwide. We need to promote this pedagogy in every way we can, including in the media, to eliminate the apparent political divide between citizens who have been to college and those who have not. There is no justification for this particular separation in our body politic.

Third, we need to promote at every opportunity stronger academic, journalistic and media offerings in American history and civics, to combat the widespread ignorance that has also undermined our politics.

Fourth and finally, we need to promote to journalists their need to habitually ask, as the first question after hearing any political opinion or unsupported assertion, “What’s your evidence?”, and if none is forthcoming, to report that fact—that non-event as an event, that the dog didn’t bark, as it were—an integral part of their stories. This past year, it took far too long for that to happen with countless baseless assertions about the election. Journalism is a teaching profession; its responsibility is to provide the first or early accounts of current history for public use and information. Journalistic “fairness” should be to truth in public record, not to all sides of contentions in controversies.

We cannot and do not expect epistemological problems, much less crises, to be successfully resolved for all parties in any specific time frame. All I am advocating here is a concerted effort on the part of as many of us as possible to achieve a better—more constructive—balance in public discourse, between efforts to promote respect for truth, and efforts to promote partisanship with no respect for truth. I have attempted to identify the main parties responsible for truth in civic and political packaging—i.e., scholars, educators and journalists—who are all our public’s teachers. These responsible parties must work much harder to promote “thinking on the basis of evidence” rather than trusting people or institutions as a way of learning truth, on which the health of our democracy necessarily depends.

George McCully, a historian, has been a former professor and faculty dean at higher- education institutions in the Northeast, then professional philanthropist and founder and CEO of the Catalogue for Philanthropy.

Keeps them moving

“Geisha-Revue, The Dance on the Volcano’’ (1911/13, oil on canvas), by Georg Tappert, at the Wadsworth Athenaeum Museum of Art, Hartford. It’s part of the show “The Dance on the Volcano: German Expressionism at the Wadsworth,’’ through May 30.

Jim Hightower: Wall Street moves in on water

— Photo by José Manuel Suárez

From OtherWords.org

Oh great — here comes a new stealth attack on the fragile, life-sustaining natural resources of Planet Earth. This latest assault by Wall Street alchemists would redefine one of our most basic resources: water.

Everyone knows that water is “invaluable” — it’s literally life, requiring a constant intake by each of us, or we quickly die. But the Wizards of Wall Street want to reduce potable H2O from its environmental, humanitarian and spiritual essence to just another perishable economic good that they can market-price and sell to the highest bidder — turning our water into speculators’ gold.

This contrivance has opened the door for financial manipulators who’ve quietly been devising razzle-dazzle schemes to allow rich global investors to play in water. They’re now pushing water futures, automated split-second trading, “water grabbing” ventures, hedging schemes, and other financialization hustles to maneuver the monetary value of this essential resource.

To see this ethically debased future, look to an outfit with the ominous acronym of WAM (Water Asset Management).

WAM is buying up water rights in low-income farming communities in places like Arizona, then literally moving the “commodity” to rich suburban developments that will pay more. WAM profiteers call water peddling “the biggest emerging market on Earth… a trillion-dollar market opportunity.”

They even boast that the crises of “drought, flood, and fire” caused by climate change creates a market volatility that will provide “an unprecedented period of transformation and investment opportunity for the water industry,” allowing investors to “thrive and prosper.”

We need to force a public discussion about this crucial question of environmental and existential ethics: Is access to an affordable supply of clean water to be a human right for all — or will we let it become a wet dream for rich speculators.

OtherWords columnist Jim Hightower is a radio commentator, writer, and public speaker.

Philip K. Howard: Paralyzing ‘rights’ are used against the public interest; bring back fair accountability

The conviction of Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin for killing George Floyd may elevate trust in American justice, but it will do little, by itself, to repair trust in police. Nor can political leaders and their appointees do much to restore that trust, because police “rights” still render officers virtually immune from accountability and basic management decisions. Chauvin was known to be “tightly wound,” and the police department had previously received 18 complaints about him abusing his power. Despite the complaints, he was not terminated or transferred. He had his rights.

But what about the public’s rights against abusive officers? We should be protected from bad cops, of course, but we can’t get there using the language of rights. Analyzing public accountability as a matter of rights is circular: Whose rights?

Rights rhetoric sprung out of the 1960s to defend freedom against institutional discrimination. But rights have evolved into an offensive weapon against the legitimate interests of other citizens—by police to avoid accountability, by teachers to avoid returning to work, by journalists and academics to cancel offensive speech.

The fabric of a free society is torn by these self-interested rights. Upholding values like fairness, reciprocity, and mutual respect is difficult when individual rights preempt the rights of everyone else.

The solution is simple: Hold people accountable again. Take “tightly wound” cops off the beat. If college students cancel other students’ freedom to hear a speaker, invite the cancelers to matriculate elsewhere. Healthy teachers who claim their potential covid exposure entitles them not to teach should find other jobs: Why should they be more privileged than nurses and grocery clerks?

But there’s a hitch: Holding people accountable is claimed to violate their rights. We seek more justice, fairness, and freedom, but we deny ourselves the tool of accountability needed to accomplish these goals.

It’s time to reset the balance between public accountability and concerns about individual fairness. Accountability must be taken out of the penalty box: Restore the freedom, up and down the chain of responsibility, to make judgments about other people and their actions. We can provide safeguards against unfairness, but law should intercede only where there is systemic discrimination or demonstrated harassment.

A Condition of Freedom

Every day, each of us evaluates the people we deal with. These judgments about other people influence how we associate, come together, and strive to achieve our private and societal goals.

People judging people is the currency of a free society.

We think of accountability in its negative sense—as the stick for inadequate performance. But accountability is needed for a positive reason—to instill the mutual trust that everyone is doing their share. It assures mutuality of effort and values. Coworkers need to believe that energy, virtue, and cooperation will be rewarded while mediocrity, indifference, and selfishness will not be tolerated.

The paradox of accountability is that once it’s available, it rarely needs to be exercised. What’s important is the availability of accountability. Once mutual trust and obligation are established, an energetic and cooperative culture leads people to do their best.

Accountability is also the organizing principle of democracy: voters elect leaders who preside over an unbroken chain of accountability down to subordinate officials. But the links in our chain of accountability are broken. Police chiefs, school principals, and government commissioners have lost their ability to hold their personnel accountable. Over 99 percent of today’s federal employees receive a “fully successful” job rating. California has one of the country’s worst school systems but can terminate no more than two or three teachers per year for poor performance. In New York, a teacher who went to jail for selling cocaine had to be reinstated in his job after his release. Under Minneapolis’ collective bargaining agreement with its union, the city’s police chief couldn’t even reassign Derek Chauvin for past misconduct, let alone terminate him, without a legal proceeding.

Democracy can’t function effectively without accountability. The conditions for social trust disappear. One effect is widespread anger and resentment at people acting irresponsibly or demanding things they don’t deserve. Society goes into a downward spiral of cynicism and selfishness. Sometimes people take to the streets.

The Illusion of Objectivity

Most people probably support the idea of accountability; but who decides, and on what basis? Most experts and academics think the job can be defined by metrics, “key performance indicators,” or other unimpeachable criteria. The Supreme Court has embraced this idea: Thus, one dubious innovation of the 1960s rights revolution was the application of due process to public personnel decisions. “It is not burdensome to give reasons,” Justice Thurgood Marshall stated, “when reasons exist.”

But “objective” accountability leads inexorably to no accountability. Being a good cop, teacher, or coworker is more complex than can be defined by objective criteria. Focusing too much on metrics—test scores, arrests, quarterly profits—will skew behavior in ways that are typically destructive. As Jerry Muller puts it in The Tyranny of Metrics (2018), measurement is useful as a tool of human judgment but not a replacement for it.

Thus, the No Child Left Behind law held schools accountable for increases in test scores—and turned many schools into drill sheds. Some school officials, supposedly role models for our youth, were caught in organized cheating schemes. In a similar way, judging surgeons by their mortality rates led many to avoid the difficult surgeries that require the most skill. Paying corporate employees according to short-term sales or profits means they will act in ways that undermine long-term corporate health.

Successful accountability rarely involves black-and-white choices. The most important qualities of employees can’t be captured by objective criteria. Good judgment, a can-do attitude and a willingness to help others can be readily identified by co-workers but are not objectifiable.

A KIPP charter school principal described to me a teacher who looked perfect on paper and tried hard but could not succeed:

He just couldn’t relate to the students. It’s hard to put my finger on exactly why. He would blow a little hot and cold, letting one student get away with talking in class and then coming down hard on someone else who did the same thing … but the effect was that the kids started arguing back. It affected the whole school. Kids would come out of his class in a belligerent mood.… We worked with him on classroom management the summer after his first year. It usually helps, but he just didn’t have the knack. So, we had to let him go.

In The Moral Life of Schools (1993), a landmark study of the traits that distinguish effective teachers, Philip Jackson and his colleagues concluded,

Laying aside all exceptions, … there is typically a lot of truth in the judgments we make of others. And this is so even when we cannot quite put our finger on the source of our opinion. That truth, we would suggest, emerges expressively. It is given off by what a person says and does, the way a smile gives off an aura of friendliness or tears a spirit of sadness.

To complicate accountability judgments, they involve not just particular persons but the way they perform in particular settings. An effective grade-school teacher may be ineffective teaching high school. “Men are neither good nor bad,” as management expert Chester Barnard observed, “but only good or bad in this or that position.”

Today, the most important criteria for fair accountability are irrelevant because they’re not objectively provable. Some of the qualities “considered too subjective to stand up in court,” as Walter Olson notes in The Excuse Factory, include these: “temperament, habits, demeanor, bearing, manner, maturity, drive, leadership ability, personal appearance, stability, cooperativeness, dependability, adaptability, industry, work habits, attitude toward detail, and interest in the job.” How could the Minneapolis police chief prove that Derek Chauvin was too tightly wound?

The Irreducibility of Human Judgment

Reviving accountability requires coming to grips with the reality that it always requires subjective judgments, in context, about the relative performance of each employee. Since the 1960s, America has rebuilt its governing structures to eliminate human judgment as far as possible. Letting people make judgments about others leaves room for unfairness or bias. Who are you to judge? Worse, we’re told to distrust our own judgments as vulnerable to unconscious bias. How can we protect against that?

What’s needed is a new protocol that instills some level of trust in accountability judgments without getting mired in rigid rights, metrics, and near-endless legal arguments. The obvious solution is to restore the legitimacy of human judgment not only for supervisors but also for other stakeholders. Studies suggest that coworkers usually have a consensus view on who’s good and who’s not: “Everyone knows who the bad teacher is.”

A school could have a parent-teacher committee with authority to veto unfair termination decisions. A police department could have an accountability review committee comprised of police, prosecutors, and citizen representatives. Private companies like Toyota have workers’ councils that give opinions before an employee is let go.

Oversight committees are hardly infallible but can provide speed bumps against supervisory unfairness. Discriminatory practices can still be reviewed by courts or other authorities where there are credible allegations of systemic discrimination.

But the pervasive overhang of legal threats for personnel judgments must be removed. Legal proceedings asserting individual rights against accountability will be irresistible to many affected workers. Nature has wired people to self-justify, and the accountable individual, studies show, is uniquely incapable of judging the fairness of such a decision. How well anyone does in an organization, Friedrich Hayek put it, “must be determined by the opinion of other people.”

We’re trained to be reluctant to let people judge other people; we want legal proof. But putting personnel judgments through the legal grinder is even less reliable. How do you prove which person doesn’t try hard, or which teacher can’t hold students’ attention?

Journalist Steven Brill described one 45-day hearing to try to terminate a teacher who was not only inept but didn’t try. She never corrected student work, filled out report cards, or met even the most rudimentary responsibilities. Her defense? There was no proof that she had been given an instruction manual telling her to do these things. This type of sophistry is typical in due process hearings: As one union official put it, “I’m here to defend even the worst people.”

Cooking accountability in a legal cauldron is in most circumstances a recipe for bitterness and frustration. The personal disappointment of a job not working out, which would be quickly forgotten if the person got a new job, becomes a kind of holy war, consuming the life of the individual supposedly protected. Discrimination lawsuits are notorious for both their high emotions and their low success rate. A federal judge told me about a case in which the evidence was overwhelming that the employee was not up to the job—but the worker was in tears at the injustice done to him.

Honoring Everyone Else’s Rights

No human grouping can long survive if its members flout accepted norms of right and wrong or tolerate failure as normal.

The quest to make accountability a matter of objective proof has turned out to be a blind alley, leading inexorably to unaccountability. No one should have the right to be unaccountable. Any claim of superior rights violates everyone else’s rights. Rights are supposed to protect against unlawful coercion, not against the judgments of other free citizens or the choices needed to manage an institution.

Putting the magnifying glass on the accountable individual ignores the rights of other affected individuals. What about the unfairness to coworkers and the public of having to deal with an uncooperative or inept person? For institutions, removing accountability is like pouring acid over workplace culture. The 2003 Volcker Commission on the federal civil service found deep resentment at “the protections provided to those poor performers” who “impede their own work and drag down the reputation of all government workers.” That’s why America’s public culture too often lacks energy, pride, and effectiveness.

Democracy fails when public institutions can’t do their jobs properly. As demonstrated by abusive cops and inept teachers, viewing accountability as a matter of individual rights means that police, schools, and other social institutions can’t serve the public effectively. Democracy becomes vestigial, a process of electing figureheads who have little effective authority over the way government operates.

In all these ways and more, the loss of accountability has eroded the rights and freedoms of all Americans, compromising much of what is admirable and strong in American culture. Good government is impossible unless officials have room to use their common sense, but no one will trust officials without clear lines of accountability.

Like putting a plug back in a socket, restoring accountability will reenergize human initiative in government and throughout society. Most people want the freedom and self-respect of doing things in their own ways and the camaraderie of working with others who also value human initiative. But the freedom to take initiative has one condition: accountability. Individuals cannot be immune from the judgments of others without undermining freedom itself.

Philip K. Howard, a New York-based civic leader, author, lawyer and photographer, is founder of Common Good (commongood.org) and author, most recently, of Try Common Sense: Replacing the Failed Ideologies of Right and Left (2019). This essay first appeared in American Purpose

Using AI in remote learning

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

BOSTON

“In partnership with artificial intelligence (AI) company Aisera, Dartmouth College recently launched Dart InfoBot, an AI virtual assistant developed to better support students and faculty members during the pandemic. Nicknamed “Dart,” the bot is designed to improve communication and efficiency while learning and working from home, with mere seconds of response time in natural language to approximately 10,000 students and faculty on both Slack and Dartmouth’s client services portal.

“The collaboration with Aisera allows for accelerated diagnosis and resolution times, automated answers to common information and technology questions, and proactive user engagement through a conversational platform.

“At Dartmouth, we wanted our faculty and students to have immediate answers to their information and technology questions online, especially during COVID. Aisera helps us achieve our goals to innovate and deliver an AI-driven conversational service experience throughout our institution. Faculty, staff, and especially students are able to self-serve their technology information using language that makes sense to them. Now our service desk is free to provide real value to our clients by consulting with them and building relationships across our campus.” said Mitch Davis, chief information officer for Dartmouth, in Hanover, N.H.’’

The field of artificial intelligence was founded at a workshop on the campus of Dartmouth during the summer of 1956. Those who attended would become the leaders of AI research for decades. Many of them predicted that a machine as intelligent as a human being would exist in no more than a generation.

The greatest need for new Amtrak money

Sections owned by Amtrak on the Northeast Corridor are in red; sections with commuter service are highlighted in blue.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Politicians across America, even anti-“Big Government” right-wingers in rural states, want Amtrak service, some of it as local pork, however lightly it is used. But as Congress considers President Biden’s almost $2 trillion infrastructure program, and the $80 billion in it for Amtrak, they should, but might not, set aside the lion’s share of the money to improve the Northeast Corridor, where it’s by far the most needed.

That where the nation’s thickest population density is; such density is very important in justifying rail passenger service. And the great popularity of the service, between Boston and Washington, D.C., has been demonstrated for decades.

The Northeast Corridor line plays an important part in lubricating the economy of this immensely important part of America, which includes both its political (Washington) and financial (New York) capitals as well as crucial technological, education and health-care infrastructure. Amtrak service there should be expanded, for economic and environmental reasons.

Amtrak owns and controls some 80 percent of the Corridor, which means, importantly, that it has considerable control over how the few freight trains use it on short sections. New York State, Connecticut and Massachusetts, for their part, own relatively sections of the route. But Amtrak is in the driver’s seat, as it should be. That isn’t to say that at least one more set of tracks, for freight and passengers, hasn’t long been needed.

You must expect that if all or part of the Biden infrastructure package is approved, that Amtrak service to thinly populated and economically insignificant parts of the country will be preserved or even expanded with lightly used long-haul trains (much beloved by train romantics), especially in states with powerful members of Congress. So be it in legislative sausage-making, but the core need for the benefit of the entire country is the Northeast Corridor.

xxx

Note the importance of Providence’s Amtrak stop not only for Rhode Islanders but for the many people from southeastern Massachusetts and eastern Connecticut who also use it, for Amtrak and MBTA service.

An Amtrak Acela train in Old Saybook, Conn.

David Warsh: Of shadowy commodities traders, ‘tropical gangsters’, deluded crowds

At the Chicago Board of Trade before the pandemic

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Because my tastes are well-established, I sometime receive new books that otherwise might escape readers’ attention. Herewith some recent arrivals.

The World for Sale: Money, Power, and the Traders Who Barter the Earth’s Resources (Oxford), by Javier Blas and Jack Farchy. A pair of former Financial Times commodities reporters, both now working for Bloomberg News, Blas and Farchy explore the shadowy world of billionaire commodity trading firms – Glencore, Trifigura, Vitol, Cargill, and the founders of the modern industry, Phillip Brothers and Marc Rich. Firms and individuals whose business is trading physical commodities – fossil fuels, agricultural commodities, metals and rare earths – enjoy a unique degree of privacy and autonomy, except from market forces. Blas and Farchy illuminate the goings-on in an otherwise almost unnoticed immense asset class ordinarily tucked away in the interior of newspapers’ financial pages.

The Culture and Development Manifesto (Oxford), by Robert Klitgaard. Remember Tropical Gangsters: Development and Decadence in Deepest Africa?

The New York Times Book Review called Klitgaard’s tale of adventures during two-and-a-half years in Equatorial Guinea one of the six best nonfiction books of 1990. The author is back, summing up various lessons learned during 30 more years advising nations, foundations, and universities on how to change (and not change) their ways. Why a manifesto? His determination, with the same good humor as before, to persuade economists and anthropologists to work together, the better to understand the context of the situations they seek to change.

The Day the Markets Roared: How a 1982 Forecast Sparked a Global Bull Market (Matt Holt Books), by Henry Kaufman. What was Reaganomics all about? Plenty of doubt remains. There is, however, no doubt about the forecast that triggered its beginning. Salomon Brothers’ long-time “Dr. Doom” recalls the circumstances surrounding the “fresh look” he offered of the future of interest rates on Aug. 17, 1982. In doing so, he reconstructs a lost world. The Dow Jones Industrial Average soared an astonishing 38.81 points the next day – its greatest gain ever to that point.

The Delusions of Crowds: Why People Go Mad in Groups (Atlantic Monthly Press), by William J. Bernstein. A neurologist, author of The Birth of Plenty: How the Prosperity of the Modern World Was Created (McGraw-Hill, 2010), Bernstein tracks the spread of contagious narratives among susceptible groups over centuries, from the Mississippi Bubble and the 1847 British railway craze to the Biblical number mysticism of Millerite end-times in 19th Century New England and various end-time prophecies in the Mideast. Such behavior is dictated by the Stone Age baggage we carry in our genes, says Bernstein.

Albert O. Hirschman: An Intellectual Biography (Columbia), by Michele Alacevich. It was never hard to understand the success of Worldly Philosopher: The Odyssey of Albert O. Hirschman, by Jeremy Adelman, a Princeton University professor and personal friend of the economist and his wife. Hirschman cut a dashing figure. He fled Berlin for Paris in the ’30s, studied economics in London, fought with the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War, moved to New York, and returned to wartime France to lead refugees fleeing the Nazis over the Pyrenees, from Marseilles to Barcelona. As a historian, biographer Adelman was less attuned to Hirschman’s subsequent career as an economic theorist – of development, democracy, capitalism, and commitment. Alacevich has provided a perfect complement, a study of the works and life of the author of the classic, Exit, Voice, and Loyalty.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this piece first ran.

'Biological batteries'

Work from the show “Justin Kedl: ATOMIC GERMINATION,’’ at Boston Sculptors Gallery, through May 30.

The gallery says:

“Kedl’s installation features a colorful collection of biomorphic ceramic forms fanning out across the wall, flowering like an alien cartoon garden. Behind the humor and visual delight of this strange colony of organisms, the artist has conjured a hopeful narrative rooted in science fiction. Kedl imagines these creatures as biological batteries from the near future, genetically engineered to feed on the most toxic byproducts of human industry—micro plastics, oil spills, radioactive waste—and convert them into clean energy that can be harnessed to power our everyday lives. Kedl notes that the work offers ‘an alternative to the normal doom-and-gloom of environmental discourse and uses science fiction as a means of imagining a more hopeful future where human progress can heal the earth rather than harm it.’’’

Have to settle for where we are

The Mount, Edith Wharton’s country place, in Lenox, Mass., in The Berkshires. from when its construction was completed, in 1902, to when she left to live in France in 1911. It’s now a museum. Ms. Wharton knew the sad and impoverished aspects of The Berkshires, too, as you see her novella Ethan Frome.

“It was easy enough to despise the world, but decidedly difficult to find any other habitable region.

— Edith Wharton (1862-1937), American novelist.

A town in The Berkshires in 1884

A 'mystical and magical' land on Cape Ann

“Red Landscape #1, Dogtown,” (acrylic on canvas), by Ed Touchette, at the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass. Gift of the artist, given in memory of Dana Todd.

The museum notes:

“The 3,000-acre swath of boulder-strewn land that makes up the center of Cape Ann has been known as Dogtown for generations. Since the disappearance of the last glacier, the area has undergone many iterations—from inhabitation by Native American groups and subsequently Colonial settlers to a sparse population of those on the fringes of society—and a slow but steady reversal of pasture lands back to the woodlands that are experienced in this protected green space today. Despite these changes, Dogtown remains mystical and magical, a sanctuary from its busier surroundings, a place for quiet thought and a reunion with nature. Read on as we explore its history and impact as a vast expanse of land that endures as both a resource and a challenge for the people of Cape Ann.’’

Chris Powell: ‘Baby bonds’ idea doesn't address need for crucial human capital

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut State Treasurer Shawn Wooden has brought to Connecticut a proposal that has been floating around the country for a few years now. Wooden would have state government endow "baby bonds" for poor children, opening $5,000 savings accounts for them at birth with the proceeds made available to them at age 18 for purposes including college education, home ownership, starting a business, or retirement savings.

The idea is pending as legislation in the General Assembly, and at a meeting in Waterbury last week Wooden argued that it would break down "structural racism." Such fashionable cant seems obligatory with many policy proposals these days, but it may be silliest as it tags along with "baby bonds," since their premise is that people are most disadvantaged not by racism at all but by poverty.

Good for the "baby bonds" idea at least for recognizing that much. But the proposal fails to recognize the primary cause of generational poverty. It is not racism or the lack of financial capital but rather the lack of human capital.

Most of the babies who would be targeted by "baby bonds" are born into homes without fathers around, and sometimes without mothers as well as they are left for a grandparent to raise. These children seldom have any mentors. Because of their lack of parenting and Connecticut's pernicious educational policy of social promotion, these children graduate from high school without having mastered even elementary school work. They are not prepared to be self-sufficient adults, much less to start and operate a business with "baby bond" money -- and most new businesses fail anyway.

As for college, young people from poor minority households who have performed well in high school are likely to get scholarships for college anyway quite without having to rely on "baby bond" money, and if they perform well in college and have developed job skills, they will have no trouble getting hired by major corporations.

But throwing money at a problem seems to be the only solution of which liberalism is capable anymore.

Poverty, not racism, is the country's biggest problem and the biggest problem of racial minorities, and Connecticut's worst "structural racism" is that of its welfare and educational systems, which, far more for racial minorities than for whites, destroy families by subsidizing childbearing outside marriage and substituting self-esteem for learning.

xxx

As the General Assembly approaches legalizing and commercializing marijuana, Connecticut may be realizing that drug criminalization is futile. But meanwhile the legislature seems about to outlaw sale of flavored "vaping" fluids used with electronic cigarettes. So what gives?

The argument for the latter legislation is that most young people who use tobacco started with electronic cigarettes, which lure them with candy-store flavorings. True enough, perhaps, but then marijuana also is a "gateway" drug, an introduction to more addictive drugs like heroin, cocaine, and prescription painkillers.

Of course, alcoholic beverages long have been beyond the capacity of many people to handle, but outlawing them a century ago made the problem worse.

Decades of public-health campaigns have sharply reduced tobacco smoking. Unfortunately such campaigns against intoxicating drugs have not been successful. Many people crave intoxication, since life isn't so enjoyable for them. But "vaping" fluids don't intoxicate and have some benefit for people trying to break tobacco addiction.

If the attack on "vaping" products means to discourage tobacco smoking, young people who "vape" will run into the anti-tobacco campaigns eventually. Even before that they might encounter a parent or mentor and get some counseling about healthy living.

Besides, just as the ingredients for making alcoholic beverages remained legal and widely available during Prohibition, the ingredients for making "vaping" fluids are legal and will remain available too. The government won't be able to eliminate them much better than it has eliminated illegal drugs. Instead government mainly will run up the price and thereby enrich some clever entrepreneurs.

Government fairly enough can prohibit the sale to minors of goods that might endanger them. But a country that would be "the land of the free and the home of the brave" shouldn't treat adults like children.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer in Manchester.