Vox clamantis in deserto

Learning and burning

“May memory restore again and again

The smallest color of the smallest day:

Time is the school in which we learn,

Time is the fire in which we burn.’’

— From “Calmly We Walk Through This April’s Day,’’ by Delmore Schwartz (1913-1966)

James T. Brett: Pell Grants should be doubled

BOSTON

College affordability and access to higher education has been a topic of much discussion in Washington, D.C., and throughout our region in recent years. And rightfully so. The price of higher education continues to increase, and millions of Americans struggle with student loan debt. At the same time, a college degree is for so many a path to career success and financial security, and our region’s employers depend on a talented pipeline of highly skilled workers to continue to grow and thrive.

One important step Congress could take in the immediate future to help make a college degree more affordable and accessible to students is to increase the maximum grant amount under the federal Pell Grant program. In fact, the New England Council—the nation’s oldest regional business association—is calling on Congress to double the maximum Pell Grant amount.

Earlier this month, NEBHE and several New England higher ed leaders and organizations asked Congress to double the Pell Grant maximum to $12,990 by the 2021-22 academic year and ensure that the increase is permanent by making the increased portion of the grant an entitlement. Read NEBHE’s letter to Congress here.

Pell Grants were established by Congress in 1972 and named in honor of the late U.S. Sen. Claiborne Pell, of Rhode Island. The grants are financial awards provided to low-income students to pursue undergraduate degrees. The program is a vital tool to ensure that low-income students–many of whom are “first-generation,” that is, the first in their immediate families to attend college–are able to pursue their undergraduate education. It is the largest source of federal funding for students pursuing post-secondary education.

For the 2021-22 award year, the maximum Pell Grant award is $6,495, not nearly enough to cover the average cost of tuition and fees for the 2020-21 academic year. The maximum Pell Grant amount has increased only in increments of $150 over the past several years—certainly not keeping pace with tuition increases and inflation. In 1975, the Pell Grant covered almost 80 percent of tuition and room and board at a four-year public college, compared with less than 60 percent today.

Doubling the maximum Pell Grant amount would enable more low-income students to pursue higher education and incur less debt. Further, an increase in the maximum Pell Grant amount would help address racial inequities in higher education. For example, according to the U.S. Department of Education, over 57 percent of African American undergraduate students received Pell Grants during the 2015-16 academic year, compared with 32 percent of white undergraduates during the same period.

There is significant support across the U.S. for doubling the Pell Grant. The New England Council is proud to join a growing list of respected national higher education associations in advocating for this change, including the National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities and the American Council on Education. More than 900 colleges around the country recently signed on to a letter advocating for doubling the Pell Grant, including many here in New England.

As the federal Pell Grant program approaches its 50th anniversary next year, we cannot think of a better way to honor the legacy of this program and recognize the importance of ensuring access to higher education for all students than by doubling the maximum grant amount. We hope that our leaders on Capitol Hill will come together to take this important step, as it would truly be an investment in America’s future.

James T. Brett is president and CEO of the New England Council, a regional alliance of businesses, nonprofit organizations, and health and educational institutions dedicated to supporting economic growth and quality of life in New England.

In the Connecticut River Valley in Massachusetts. The valley is well known for the colleges up and down the valley. New England’s world-famous higher-education complex of big research universities, small liberal-arts colleges and specialized institutions comprise one of its biggest industries.

Ebb and flow

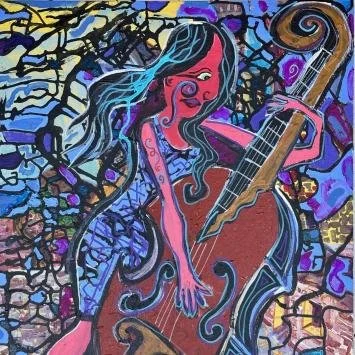

“Each Piece is Different’’ (acrylic on canvas), by Charlie Bluett, at Edgewater Gallery, Middlebury, Vt.

Charlie Bluett’s studio is in the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont. He was born in England and educated at Eton College there, and has exhibited extensively in the United Kingdom and the United States.

The gallery says:

“Bluett is an abstract painter who is inspired by the ebb and flow of the natural processes of the earth. Using this as his reference, his interest is then in the process of building form, color, and surface texture into large scale compositions that are bold and dynamic, but also subtle in their shifting shapes and tones. His works contain elements that pay homage to the techniques of the old masters, blended with abstract expressionism and the colorfield painting of the contemporary names of our time.’’

Panoramic view of Willoughby Notch and Mount Pisgah, in the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont.

— Photo by Patmac13

Todd McLeish: Surprises in book about two water-loving insect groups

Dragonflies

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Those curious about dragonflies and damselflies — the colorful, predatory aerialists seen at nearly every pond, lake, stream and river in summer — now have a new source of information about the numerous species found in Rhode Island.

Virginia “Ginger” Brown, the state’s leading dragonfly expert, recently authored and published a book called Dragonflies and Damselflies of Rhode Island. The book will help readers learn about the natural history, distribution and abundance of the state’s 139 species of odonates, the insect order that includes dragonflies and damselflies. The book was published in February by the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s Division of Fish and Wildlife, its third volume about local wildlife.

“The book is designed for beginning naturalists, experienced naturalists, conservation groups, and just about anybody with an interest in the outdoors, like fishermen who see dragonflies when they’re fishing,” said Brown, a resident of Barrington who also wrote The Dragonflies and Damselflies of Cape Cod, in 1991. “It’s not something you’re going to carry with you in the field, but it’s a reference to help you identify and learn about every dragonfly and damselfly in Rhode Island.”

The 384-page book features profiles of each species, including habitat characteristics, range, behaviors, dates when they are active locally, and a map indicating where they have been observed. All of the illustrations are by artist and entomologist Nina Briggs, of Wakefield.

Most of the data for the book was collected between 1998 and 2004, when Brown organized an extensive citizen science project that culminated with the publication of the “Rhode Island Odonata Atlas,” a statewide inventory of dragonflies and damselflies. About 70 volunteers participated in the creation of the atlas, visiting more than 1,100 ponds, lakes, streams, rivers, and other sites in every community in the state to document as many species as they could find. More than 13,000 specimens were collected and identified.

“A large amount of what we know about odonates in Rhode Island was generated by those volunteers, many who had no experience with insects before,” said Brown, a biologist who used to work for the Rhode Island Natural History Survey. “I didn’t know how much they would be able to do and how many records they would produce, and I didn’t know if they would like getting up to their knees in the muck or how successful they’d be at swinging at net to catch them. It was so much fun to work with all of those people.”

Among the findings highlighted in the book was the discovery of several species never before recorded in New England, including the southern sprite and coppery emerald, both of which are southern species that Brown didn’t expect to find in the Ocean State. A species from the far north, the crimson-ringed whiteface, was also a surprise discovery.

Another new species for Rhode Island, the unicorn clubtail, turned out to be much more common than anyone imagined.

“We ended up finding it at 60 sites in all five counties in the state, making it a pretty ubiquitous critter,” Brown said. “It’s something that occurs in ponds without a lot of vegetation, a habitat that doesn’t look particularly intriguing and that may not have a lot of other species in them. It’s a new record for the state, but it turned out to be in 26 towns.”

Brown was especially pleased with the variety of dragonfly and damselfly species found throughout the state, and was surprised to find high diversity at unlikely places, such as the Blackstone River.

Overall, more than 100 species were recorded in five communities, and at least 90 species were found in an additional seven communities.

Not all of the data for Brown’s book came from the atlas project. Brown and several other entomologists collected some data independently in the years prior to the atlas, and additional information was added while the book was being written and designed.

After the “Rhode Island Odonata Atlas” was completed, the scientists concluded that a damselfly called the northern spreadwing was actually two different species, so Brown had to sort through her records to determine which of the two species were represented at the Rhode Island sites where they were found. And when an unexpected species called the Allegheny river cruiser turned up in Connecticut, she sorted through her records again to see whether any of the Rhode Island records of a very similar species, the swift river cruiser, were misidentified.

“That’s when I learned to never make assumptions,” Brown said.

With her latest book finally completed, Brown is planning to revisit some sites to confirm that some of the rarer species are still in the waterbodies where they were initially found.

“We’ve had some population loss going on, so we need to get back to check on species of greatest conservation need,” she said. “The 2010 floods knocked out some small dams, which drained some ponds, and that might be the reason for some of these losses. With more extreme rainfall events associated with climate change, we could have more ruptured dams and more population losses.”

Damselfly

Dragonflies and Damselflies of Rhode Island is available for $25, which includes shipping, and can be bought by emailing DEM.DFW@dem.ri.gov.

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish runs a wildlife blog.

Dedicate your life

‘Status-seeking has to be fought anew in every generation. The dedicated life is the life worth living. You must give with your whole heart.’’

— Annie Dillard (born 1945), Pulitzer Prize-winning fiction and nonfiction author. She spends part of the year in Wellfleet, on outer Cape Cod.

Looking toward Wellfleet Harbor from over the town’s elementary school

— Photo by Achituv

Smith’s 'meditations on land, water and air'

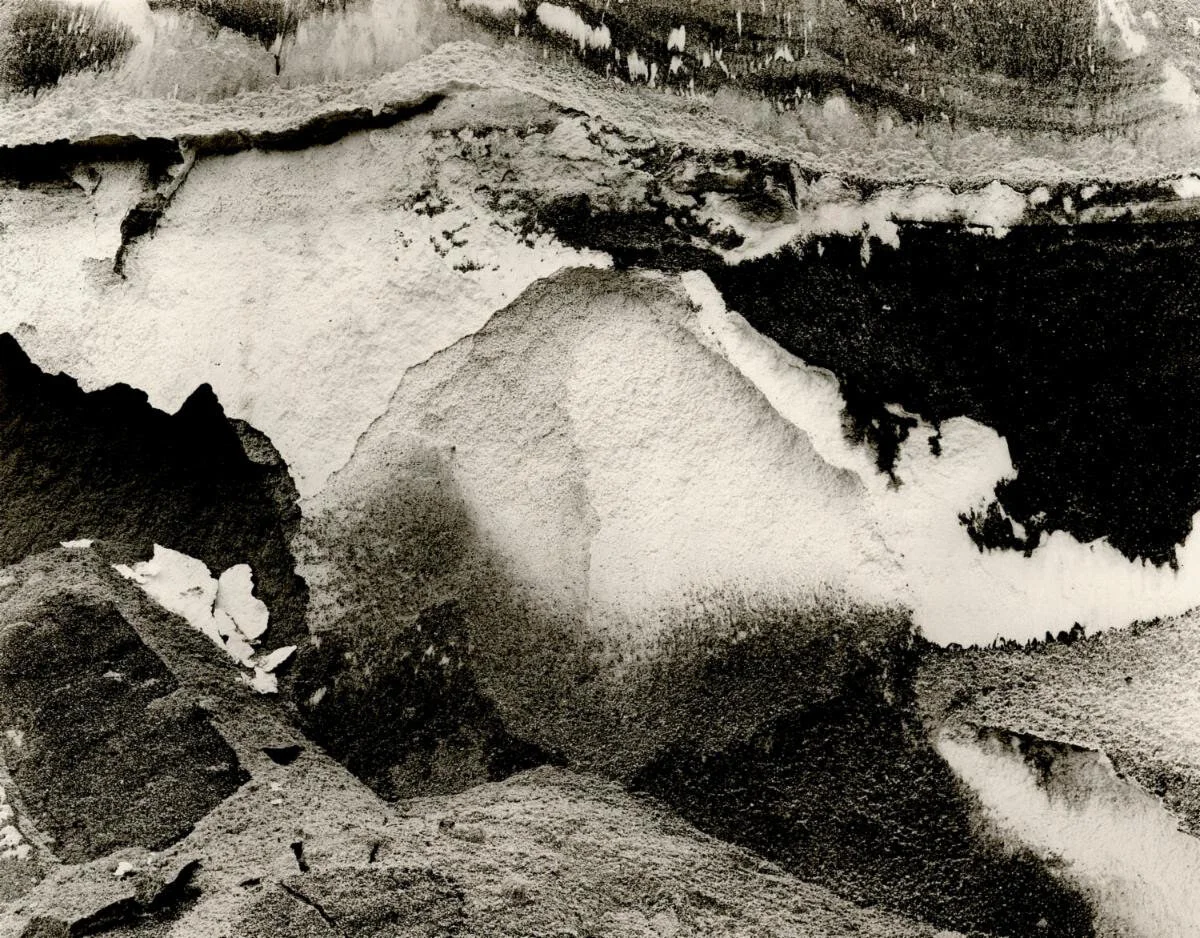

“Stream No. 31” (chromogenic print), by British-born (but now of Brooklyn) photographer Jonathan Smith, in his show at Lanoue Gallery, Boston, through May 23.

The gallery says:

Jonathan Smith spent the early years of his career assisting and printing for the renowned photographer Joel Meyerowitz {famous for his photos of Cape Cod}, and has had solo exhibitions in both nationally and internationally. His work consists of large-scale, highly nuanced color photographs of the stark natural beauty and inherent impermanence of landscapes.

“Smith has been photographing natural landscapes for more than 15 years. Shooting precisely and selectively with incredible detail, often revisiting the same site on several occasions until he feels the essential character of the landscape has been revealed to him. This conscious and gradual process of documentation results in meditations on land, water and air.’’

His investigations of landscape have led him to the remote locations of northern Iceland and southern Patagonia, where he photographed streams, glaciers, glacial rivers and waterfalls. These landscapes, devoid of human presence, display a world lost in time. Often abstracted, these photographs of mountain streams and glacial shifts are a reminder of the forces of nature at play; a sublime beauty far removed from the everyday. Drifting into frame, the dreamlike palette of these landscapes offers a window into an ephemeral world where scale and perspective become impalpable. These landscapes inspired the creation of large-scale prints that echo the vastness of the spaces they depict, inviting the viewer in to contemplate their own relationship to the natural world.

Above: Stream No. 31, chromogenic print, available sizes: 30x37.5" ed. of 8, 40x50" ed. of 5, 56x70" ed. of 3

Rachel Bluth: After a year of motorized mayhem, Mass., Conn., R.I., other states consider crackdowns

“American Landscape’’ (graphite on Strathmore rag, 1974), by Jan A. Nelson

See news on this topic from Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut below.

As more Americans start commuting to work and hitting the roads after a year indoors, they’ll be returning to streets that have gotten deadlier.

Last year, an estimated 42,000 people died in motor-vehicle crashes and 4.8 million were injured. That represents a 8 percent rise from 2019, the largest year-over-year increase in nearly a century — even though the number of miles driven fell by 13 percent, according to the National Safety Council.

The emptier roads led to more speeding, which led to more fatalities, said Leah Shahum, executive director of the Vision Zero Network, a nonprofit organization that works on reducing traffic deaths. Ironically, congested traffic, the bane of car commuters everywhere, had been keeping people safer before the pandemic, Shahum said.

“This is a nationwide public health crisis,” said Laura Friedman, a California Assembly member who introduced a bill this year to reduce speed limits. “If we had 42,000 people dying every year in plane crashes, we would do a lot more about it, and yet we seem to have accepted this as collateral damage.”

California and other states are grappling with how to reduce traffic deaths, a problem that has worsened over the past 10 years but gained urgency since the onset of the covid-19 pandemic. Lawmakers from coast to coast have introduced dozens of bills to lower speed limits, set up speed camera programs and promote pedestrian safety.

The proposals reflect shifting perspectives on how to manage traffic. Increasingly, transportation safety advocates and traffic engineers are calling for roads that get drivers where they’re going safely rather than as fast as possible.

Lawmakers are listening, though it’s too soon to tell which of the bills across the country will eventually become law, said Douglas Shinkle, who directs the transportation program at the National Conference of State Legislatures. But some trends are starting to emerge.

Some states want to boost the authority of localities to regulate traffic in their communities, such as giving cities and counties more control over speed limits, as legislators have proposed in Michigan, Nebraska and other states. Some want to let communities use speed cameras, which is under consideration in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Florida and elsewhere.

Connecticut is considering a pedestrian safety bill that incorporates multiple concepts, including giving localities greater authority to lower speeds, and letting some municipalities test speed cameras around schools, hospitals and work zones.

“For decades really we’ve been building roads and highways that are suitable and somewhat safe for motorists,” said Connecticut state Sen. Will Haskell (D.-Westport), who chairs the committee overseeing the bill. “We also have to recognize that some people in the state don’t own a car, and they have a right to move safely throughout their community.”

A huge jump in road fatalities started showing up in the data “almost immediately” after the start of the pandemic, despite lockdown orders that kept people home and reduced the number of drivers on the road, said Tara Leystra, the National Safety Council’s state government affairs manager.

“A lot of states are trying to give more flexibility to local communities so they can lower their speed limits,” Leystra said. “It’s a trend that started before the pandemic, but I think it really accelerated this year.”

In California, citations issued by the state highway patrol for speeding over 100 miles per hour roughly doubled to 31,600 during the pandemic’s first year.

Friedman, a Democrat from Burbank, wants to reform how California sets speed limits on local roads.

California uses something called the “85th percentile” method, a decades-old federal standard many states are trying to move away from. Every 10 years, state engineers survey a stretch of road to see how fast people are driving. Then they base the speed limit on the 85th percentile of that speed, or how fast 85% of drivers are going.

That encourages “speed creep,” said Friedman, who chairs the state Assembly’s transportation committee. “Every time a survey is done, a lot of cities are forced to raise speed limits because people are driving faster and faster and faster,” she said.

Even before the pandemic, a California task force had recommended letting cities have more flexibility to set their speed limits, and a federal report found the 85th percentile rule similarly inadequate to set speeds. But opposition to the rule is not universal. In New Jersey, for instance, lawmakers introduced a bill this legislative session to start using it.

Friedman’s bill, AB 43, would allow local authorities to set some speed limits without using the 85th percentile method. It would require traffic surveyors to consider areas like work zones, schools and senior centers, where vulnerable people may be using the road, when setting speed limits.

In addition to lowering speed limits, lawmakers also want to better enforce them. In California, two bills would reverse the state’s ban on automated speed enforcement by allowing cities to start speed camera pilot programs in places like work zones, on particularly dangerous streets and around schools.

But after a year of intense scrutiny on equity — both in public health and in law enforcement — lawmakers acknowledge they need to strike a delicate balance between protecting at-risk communities and overpolicing them.

Though speed cameras don’t discriminate by skin color, bias can still enter the equation: Wealthier areas frequently have narrow streets and walkable sidewalks, while lower-income ones are often crisscrossed by freeways. Putting cameras only on the most dangerous streets could mean they end up mostly in low-income areas, Shahum said.

“It tracks right back to street design,” she said. “Over and over again, these have been neighborhoods that have been underinvested in.”

Assembly member David Chiu (D.-San Francisco), author of one of the bills, said the measure includes safeguards to make the speed camera program fair. It would cap fees at $125, with a sliding scale for low-income drivers, and make violations civil offenses, not criminal.

“We know something has to be done, because traditional policing on speed has not succeeded,” Chiu said. “At the same time, it’s well documented that drivers of color are much more likely to be pulled over.”

Rachel Bluth is a Kaiser Health News journalist.

This story was produced by KHN, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

Nontheological reclusion

Saint Jerome, who lived as a hermit near Bethlehem, depicted in his study being visited by two angels (Cavarozzi, early 17th Century).

“The peculiarity of the New England hermit has not been his desire to get near to God but his anxiety to get away from man.’’

— Hamilton Wright Mabie (1845-1916), American essayist, editor, critic and lecturer

May be washable if not edible

“Fiberglass sphere” (sculpture), by Brunswick, Maine-based William Zingaro, at the Corey Daniels Gallery, Wells, Maine.

The south end of Wells Beach. How long will those houses last?

One of Wells’s one-room schoolhouses, built in the 19th Century.

— Photo by BMRR

May Worcester's big baseball gamble pay off

Rendition of Polar Park

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The new, $159.5 million Polar Park project, in Worcester, looks lovely, as well it should at that price. Worcester, through borrowing, is paying $88.2 million, the Worcester Red Sox $60.6 million and the state and Feds $10.7 million, at least according to a Feb. 4 Worcester Business Journal report.

Will Polar Park pay for itself in bigger local business revenues and payrolls and such related public benefits as more municipal-property-tax revenue? Generally, publicly financed sports stadiums don’t pay for themselves, at least in measurable monetary benefits for the taxpayers, though of course they can be very lucrative for the team owners. And there can be psychic benefits for some locals from the pride in having a (hopefully) successful team to rally around and an often jolly place to gather.

In the case of Worcester, I have some doubts on whether, after a year or two of people drawn by curiosity to the new ballpark, the WooSox can lure the number of long-term gamegoers they hope for.

While Worcester was very narrowly the second-largest city in New England in the 2010 Census, with 181,045 people, compared to Providence’s 178,042, its metro area had only 923,672 people, compared to Greater Providence’s 1.6 million. Providence proper’s area is only 20.58 square miles, compared with Worcester’ 38.41.

Those numbers seemingly would have made it much more sensical to keep the Pawtucket Red Sox going, even with less than the substantial taxpayer help that the organization had been offered in the Ocean State. Further, Providence/Pawtucket is on the main street of the East Coast and Worcester is more off to the side.

Well, que sera, sera. Now that Polar Park is up, I wish the WooSox all the best and plan a trip there soon to check it out. While I have little interest in such things as baseball statistics (real baseball fans are obsessed with such data) and don’t much follow the ups-and-downs of current stars, I do love the setting, sights and sounds of baseball: The slope of the stands; the smell of very green grass and of hot dogs and beer; the cheers (and boos); the crack of the ball against the bat; the tacky organ music; the alternations of relative immobility and explosive activity; the manic announcers, and the seventh inning stretch.

As for folks living in and around Worcester, perhaps it will become one of those “third places,’’ such as restaurants, coffee shops, gyms and even some bookstores, where locals go to hang out with their neighbors on a regular basis. We may know within a couple of years. Maybe it will become as beloved a local institution (for many) as Clark University, the College of the Holy Cross, Worcester Polytechnic Institute and the Worcester Museum of Art, and as the PawSox were for so many years in Greater Providence. Maybe.

More rail connections, please

Current MBTA commuter rail map

—By Das48

U.S. Rep. Stephen Lynch, of South Boston, to the State House News Service on what might be built if President Biden’s infrastructure bill is enacted.

“What I’m hoping is that with East-West Rail we might be able to make those western suburbs and outlying suburbs around Greater Boston more attractive places to live so people can get in and out of the city, and continue to work there and have a vibrant, vibrant community extending up into southern New Hampshire and down into Rhode Island and Connecticut. “We lose a lot of talent in Boston and New England because of housing prices. So if we can use that rail project to make the connection between workers that need more affordable housing and those nearby suburbs, I think that’s a great blueprint for the future.”

Brent McCall: Fraudulent staffing in prisons

At the Cheshire Correctional Institution, in Cheshire, Conn.

The following two letters were written by Brent McCall, co-author along with Michael Liebowitz of Down the Rabbit Hole: How the Culture of Corrections Encourages Crime. Both concern what prisoners in New York call “clocksuckers,” prison employees who engage in stretching their paychecks at the expense of taxpayers.

— Don Pesci, Vernon, Conn.-based columnist

Editor’s note: Both McCall and Liebowitz were convicted of violent crimes.

CHESHIRE, Conn.

You’ve probably heard that Connecticut’s prison population is the lowest it has been in 30 years. Much less touted by the powers that be is that staffing levels within the Department of Corrections (DOC) remain at record highs. There are currently somewhere in the neighborhood of 6,000 corrections employees guarding fewer than 9,000 prisoners, And at a costyt of more than half as billion dollars a year to run the state’s prison system, it’s hard to imagine how such staffing levels may be justified. Even when they cannot be justified, DOC employees readily conspire to make it look like they can.

This occurred recently in the carpentry class at Cheshire Correctional Institution when, for reasons not entirely clear to me, Mr. Toth, the carpentry teacher who used to work at York Correctional Institution, was transferred here. The story Mr. Toth tells is that the DOC defunded the carpentry program he taught at York. The thing is, however, it has not funded a program for him here at Cheshire.

Since Cheshire Correctional Institution already has a carpentry teacher, Mr. Toth, for the first several months he was here, would just come into work and hang out in an empty room all day with nothing to do. Recently, however, there have been efforts by several staff members here to make it look like Mr. Toth’s services continue to be needed.

For example, On Feb. 4 the inmates of the existing carpentry class, myself included, were told that the class roster would be split in two in order to provide “justification,” their word, not mine, for Mr. Toth being here. We were also told at the time that although Mr. Toth could answer student questions, he would be unable to run a class on his own because he would not have access to the tool crib. And it didn’t take long for his so called “students” to learn what that meant.

On March 6, the original carpentry teacher was absent from his work. Despite this, Mr. Toth came into the housing unit to collect “his students.” Before leaving the unit, he got six of us together and told us that we would be going out to the shop, but that he wouldn’t be able to actually do anything because he didn’t have the keys to the crib or the office.

He further stated that he was only “going through the motions” because he had to “justify” his being here. And, sure enough, he wasn’t even able to provide as much as a single pencil for the six of us to share. Our sole purpose in being there was to help him bilk the taxpayers of Connecticut out of another day’s pay and benefits, something he had been doing, with the apparent blessing of his superiors, for more than six months.

Not only does this scheme violate at least a dozen departmental directives, it also violates the law, because documents were fabricated in order to create the illusion that Mr. Toth actually has students and therefore duties to perform. The split roster may be the tip of a larger iceberg, and while I’ll spare you the legalese, this type of document fabrication is clearly identified as second-degree forgery by Connecticut General Statutes (#53a-139); and, of course, to the extent that employees of the DOC had agreed to create this illusion, conspiracy as well (#53a-48). According to the General Statutes, second-degree forgery and conspiracy to commit forgery are both class D felonies, each punishable by up to five years in prison. Also, prisoners are conscripted into an unwitting co-conspiracy.

This brings us back to my original question: When does government mismanagement become a crime?

There are undoubtedly a number of ways this could be answered. But surely I have presented one of them here; which is to say, when state employees conspire to create “official” documents in an effort to protect a co-worker’s employment. That, I am afraid, is fraud. And if we allow the employees of any state agency to do such things with impunity, there really is no limit to the financial abuses they can perpetuate.

What Can Be Done With The ‘Clocksuckers’?

Abusers of the Department of Corrections overtime policy in New York State are known throughout the prison population as “clocksuckers.”

Indeed, abuse of overtime within the Connecticut Department of Corrections (CDOC) has been glaringly widespread for years. Year in and year out, the CDOC consistently has the highest overtime expenditures of any state agency.

In the two years prior to the Coronavirus pandemic, for instance, the CDOC spent nearly $80 million on overtime, with 2019’s expenditures exceeding 2018’s by several million; this during a period of time when the overall workforce increased while the prisoner population actually decreased.

The simple fact is Connecticut’s taxpayers spend tens of millions annually funding overtime for prison guards who have no legitimate reason to be working overtime. And the thing is – everyone in the department, from the commissioner on down, knows it.

The scheme works like this: The contract that the state has with the Corrections unit dictates that prison guards be paid time and a half after working eight hours – rather than forty hours. This has led to a culture of corruption wherein officers routinely trade shifts with one another in a way that allows each of them to work as many doubles as they like. Rather than earning straight pay for their scheduled hours, prison guards are able to pad their paychecks – by as much as 50 percent or more – merely by taking advantage of the department’s over-generous overtime policy. And since CDOC retirement benefits are tied directly to an employee’s highest earning years, the graft continues to pay dividends long after one’s employment with the department has ended.

It’s clear this practice violates the law, even if authorities refuse to recognize it as such. After all, we are ultimately talking about individuals committing fraud for financial gain.

The fact that the union contract permits time and a half after eight hours in no way excuses or justifies the abusive practices in which so many CDOC employees engage. But even if an argument could be made that prison officials shouldn’t report the overtime abusers to law enforcement for arrest and prosecution, it’s hard to understand why they refuse to enforce the department’s own policies regarding the issue.

Although the CDOC Administrative Directives do not expressly prohibit abuse of overtime, there are several directives that implicitly prohibit the practice. For example, the CDOC’s Code of Employee conduct prohibits personnel from “Engaging in unprofessional or illegal behavior… that could reflect negatively on the Department…” (A.D. 2l.17~ (5)(b)12). Clearly, staff manipulating overtime policy to the detriment of taxpayers reflects negatively on the department. I know it does this with the inmate population. And I imagine it would with the public too, if the public wasn’t kept in the dark about it.

The CDOC Code of Ethics prohibits staff from engaging in “Any financial interest… which ‘substantially conflicts’ with… the public interest (A.D. 1.13 ~ (4)(B)(1).”

If prison guards fleecing the taxpayers of Connecticut out of millions of dollars a year through what amounts to nothing less than a contractual sleight of hand doesn’t “substantially conflict” with the public interest, then I don’t know what would.

The directive which mandates that employees “Promptly report any corrupt, illegal, unauthorized, or unethical behavior (A.D. 1.13~(4)(A)(7)” has proven entirely ineffective at putting a stop to overtime abuses. But I suppose that’s not all that surprising: co-conspirators rarely roll over on each other without a credible threat of punishment.

If you ask me, the solution to the widespread abuse of overtime by CDOC personnel is pretty simple. Even if prison officials refuse to report the culprits to law enforcement, they should at least move to fire the clocksuckers.

At the York Correctional Institution, in Niantic, Conn.

Use what you can

“Untitled 2101” (kozo, flax, tarleton, wire), by Vivian Pratt, in her show “Transforming Fibers,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, through May 2.

David Warsh: Spence Weart sums up the global-warming crisis that's upon us

Average surface air temperatures from 2011 to 2020 compared to a baseline average from 1951 to 1980 (Source: NASA)

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Every April since I first read it, in 2004, I take down and re-read some portions of my copy of The Discovery of Global Warming (Harvard), by Spence Weart. (The author revised and expanded his book in 2008.) I never fail to be moved by the details of the story: not so much his identification of various major players among the scientists – Arrhenius, Milankovitch, Keeling, Bryson, Bolin – but by the account of the countless ways in which the hypothesis that greenhouse-gas emissions might lead to climate change was broached, investigated, turned back on itself (more than once), debated and, eventually, confirmed.

In the Sixties, Weart trained as an astrophysicist. After teaching for three years at Caltech, he re-tooled as a historian of science at the University of California at Berkeley. Retired since 2009, he was for 35 years director of the Center for the History of Physics of the American Institute of Physics, in College Park, Md.

This year, too, I looked at the hypertext site with which Weart supports his much shorter book, updating it annually in February, incorporating all matter of new material. It includes recent scientific findings, policy developments, material from other histories that are beginning to appear. The enormous amount of material is daunting. Several dozen new references were added this year, ranging from 1956 to 2021, bringing the total to more than 3,000 references in all. Then again, all that is also reassuring, exemplifying in one place the warp and woof of discussion taking pace among scientists, of all sorts, that produces the current consensus on all manner of questions, whatever it happens to be. Check out the essay on rapid climate change, for example.

Mainly I was struck by the entirely rewritten Conclusions-Personal Note, reflecting what he describes as “the widely shared understanding that we have reached the crisis years.”

Global warming is upon us. It is too late to avoid damage — the annual cost is already many billions of dollars and countless human lives, with worse to come. It is not too late to avoid catastrophe. But we have delayed so long that it will take a great effort, comparable to the effort of fighting a world war— only without the cost in lives and treasure. On the contrary, reducing greenhouse gas pollution will bring gains in prosperity and health. At present the world actually subsidizes fossil fuel and other emissions, costing taxpayers some half a trillion dollars a year in direct payments and perhaps five trillion in indirect expenses. Ending these payments would more than cover the cost of protecting our civilization.

Plenty else is going on in climate policy. President Biden is hosting a virtual Leaders Summit on Climate on Thursday, April 22 (Earth Day) and Friday, April 23. Nobel laureate William Nordhaus pushes next month The Spirit of Green: The Economics of Collisions and Contagions in a Crowded World (Princeton), reinforcing Weart’s conviction that it actually costs GDP not to impose a carbon tax on polluters. Public Broadcasting will roll out later this month a three-part series in which the BBC follows around climate activist Greta Thunberg in A Year to Change the World. And Stewart Brand, who in 1967 published the first Whole Earth Catalog, with its cover photo of Earth seen from space, is the subject of a new documentary, We Are as Gods, about to enter distribution. There is other turmoil as well. But if you are looking for a way to observe Earth Day, reading Spencer Weart’s summing-up is an economical solution.

David Warsh, an economic historian and a veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first appeared.

© 2021 DAVID WARSH, PROPRIETOR

—Graphic by Adam Peterson

Before sliding down the razor blade

Tom Lehrer in 1957, as he was becoming famous.

Bright college days, oh, carefree days that fly

To thee we sing with our glasses raised on high.

Let's drink a toast as each of us recalls

Ivy-covered professors in ivy-covered halls.

Turn on the spigot

Pour the beer and swig it

And gaudeamus igitur

Here's to parties we tossed

To the games that we lost

We shall claim that we won them some day.

To the girls young and sweet

To the spacious back seat

Of our roommate's beat up Chevrolet.

To the beer and benzedrine

To the way that the dean

Tried so hard to be pals with us all.

To excuses we fibbed

To the papers we cribbed

From the genius who lived down the hall.

To the tables down at Mory's

Wherever that may be

Let us drink a toast to all we love the best.

We will sleep through all the lectures

And the cheat on the exams

And we'll pass, and be forgotten with the rest.

Oh, soon we'll be out amid the cold world's strife.

Soon we'll be sliding down the razor blade of life

O-oh!

But as we go our sordid separate ways

We shall ne'er forget thee, thou golden college days.

Hearts full of youth.

Hearts full of truth.

Six parts gin to one part vermouth.

“Bright College Days,’’ by Tom Lehrer (born 1928), a now retired American musician, singer-songwriter, satirist, mathematician and professor (in which position he taught mathematics and the history of musical theater, among other topics). He’s best known for the often hilarious and sometimes biting songs that he recorded in the 1950s and 1960s, though he had written some of the songs as early as the late ‘40s. A Harvard graduate, he taught there as well as at MIT, Wellesley College and the University of California at Santa Cruz. In his heyday, he starred in numerous concerts, singing his songs as he played them on a piano.

Mory’s, founded in 1849, is a private club/restaurant/watering hole in New Haven whose membership is confined to those with Yale connections. It is virtually on the Yale campus.

'The Painted State'

“September Barrens,’’ by New Castle, N.H.-based Grant Drumheller, in the show “Maine: The Painted State: 2021,’’ at Greenhut Galleries, Portland, through May 29. (One thinks of Maine’s famous blueberry barrens here.)

This biennial exhibit celebrates Maine's place in American art history, and how this tradition carries on into the present day, with reinvention on the way. In this 44th year of the exhibit, 45 contemporary Maine artists depict places very important to them, from lush forests to rocky coastlines. But then, Maine's inspiring landscape that has made drawn great artists throughout history.

The famous Wentworth-by-the-Sea resort hotel, in New Castle, N.H., in 1920. The Wentworth is still there, in much modernized fashion.

Todd McLeish: Invasive water plants imperil ponds

In less than seven years this Sacred Lotus patch has taken over nearly two acres of 12-acre Meshanticut Pond, in Cranston, R.I.

— R.I. Department of Environmental Management photo

From ecoRI News (ecori.0rg)

When a Cranston, R.I., resident planted a Sacred Lotus in the pond at Meshanticut State Park in memory of a family member in 2014, she didn’t realize that the plant was an aggressive invasive species. The lotus, which features enormous floating leaves that shade out native plants, quickly took over a large area of the Rhode Island pond.

Five years later, 75 volunteers spent 12 hours cutting it back, but they eradicated just 10 percent of the ever-expanding plant, which today covers 1.83 acres of the 12-acre pond.

It’s one of many examples of the challenges the state faces in trying to control and eliminate aquatic invasive species. More than 100 lakes and 27 river segments in Rhode Island are plagued with at least one species of invasive plant, according to the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM). These plants pose threats to healthy ecosystems, reduce recreational opportunities, and negatively impact the economy.

“Aquatic invasives are definitely a problem for water quality, but there aren’t a lot of resources dedicated to mapping them and trying to contain them,” said Kate McPherson, riverKeeper for Save The Bay. “The problem is they can show up in really pristine areas of the state for a variety of reasons, and a lot of the plants only need a couple of cells or a leaf to reproduce. They don’t need seeds. So unless you’re really diligent about scrubbing down your boat and other equipment after each use, it’s really hard to prevent their spread.”

In its 2020 fishing regulations, DEM prohibited the transport of invasive plants on any type of boat, motor, trailer, or fishing gear as a strategy to prevent the inadvertent movement of aquatic invasive species from one waterbody to another.

“It’s essentially an incentive for boaters or anglers to clean off their gear to make sure they don’t move any plants unintentionally,” said Katie DeGoosh of DEM’s Office of Water Resources. “It’s part of a national campaign known as Clean Drain Dry to remind anyone recreating on water how they should decontaminate their gear to avoid spreading invasives.”

DEM’s latest effort to combat aquatic invasive species is proposed regulations to ban their sale, purchase, importation, and distribution in the state. Rhode Island is the only state in the Northeast that has yet to regulate the sale of these plants.

The proposed regulations have the support of Save The Bay, the Rhode Island Natural History Survey, and the Rhode Island Wild Plant Society.

Those with aquatic plants in backyard water gardens aren’t the focus of the regulations because those residents aren’t selling the plants, DeGoosh said.

A mat of Water Chestnuts in Olney Pond at Lincoln Woods State Park limits the amount of light available to other aquatic plants, allowing it to quickly displace native species and decrease biodiversity. (DEM)

The proposed regulations list 48 species of aquatic invasive species whose sale would be prohibited. All but one — Sacred Lotus — are included on the Federal Noxious Weed List, are banned by other states in the region, were nominated by the Rhode Island Invasive Species Council or are included in the Rhode Island Aquatic Invasive Species Management Plan.

Among them are Carolina Fanwort, a problem species in numerous locations, such as Stump Pond in Smithfield; American Lotus, which covers 18 acres of Chapman Pond in Westerly; Brazilian Waterweed, which has invaded Hundred Acre Pond in South Kingstown; and common Water Hyacinth, an Amazonian species now found in the Pawcatuck River in Westerly.

Perhaps the worst of them is Variable Milfoil, which has been recorded in 69 lakes and ponds and 19 river segments in Rhode Island.

“Milfoil means a million tiny leaves,” said McPherson, who monitors local rivers for invasive species. “It looks like a submerged raccoon tail, and if you’ve been paddling in any pond in Rhode Island, you’ve probably seen it. A tiny little fragment can spread it.”

In many waterbodies, especially in urban communities, multiple species of aquatic invasives have colonized.

“They’re a problem because they can choke out native species and they may not be as good a food source for animals that eat aquatic plants,” McPherson said. “They’re also indicative of a water-quality problem. We’re seeing them more commonly in areas with too much phosphorous or nitrogen in the water. Areas with pollutants encourage these plants to grow.”

David Gregg, executive director of the Rhode Island Natural History Survey, also noted the impact of pollution in helping aquatic invasives take hold.

“People really care about their lakes, but most lakes in Rhode Island are man-made, shallow, and polluted by surrounding development — lawns, septics, road runoff — and so they grow invasive plants like nobody's business,” he said.

Like at Meshanticut Pond, once the plants become established in a waterbody, they are difficult to eradicate.

“It’s a cyclical problem,” McPherson said. “It’s super satisfying to go as a volunteer to rip it out, and super discouraging to go back a year later and find that it’s still there. If you don’t get all of the root system, it grows back.”

Natural History Survey staff documented the first occurrence of invasive water chestnut in the state in 2007 at Belleville Pond in North Kingstown. They led numerous volunteer efforts to manually remove it every year for a decade, and yet the plant remains. A similar endeavor to battle water chestnut at Chapman Pond in Westerly barely made a dent in the abundance of the plant.

“It’s a big problem,” McPherson said. “We need to get folks to think about how their activities can spread the plants and get them to think about aquatic invasives as a kind of contaminant.”

The proposed regulations, if approved, would be enforced via business inspections by DEM staff. Violators could be fined up to $500 per violation.

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish runs a wildlife blog.

Jim Hightower: The scam of 'trickle-down economics'

Via OtherWords.org

The past year proves that a lot of conventional economic wisdom is neither true nor wise. For example:

1) “We don’t have the money.”

The power elites tell us it would be nice to do the big-ticket reforms America needs, but the money just isn’t there. Then a pandemic slammed into America, and suddenly trillions of dollars gushed out of Washington for everything from subsidizing meatpackers to developing vaccines, revealing that the money is there.

2) “We can’t increase the federal debt!”

Yet Trump and the Republican Congress didn’t hesitate to shove the national debt through the roof in 2017 to let a few corporations and billionaires pocket a $2 trillion-dollar tax giveaway. If those drunken spenders can use federal borrowing to make the likes of Amazon and Mark Zuckerberg richer, we can borrow funds for such productive national needs as infrastructure investment and quality education for all.

3) “The rich are the ‘makers’ who contribute the most to society.”

This silly myth quickly melted right in front of us as soon as the coronavirus arrived, making plain that the most valuable people are nurses, grocery clerks, teachers, postal employees, and millions of other mostly low-wage people. So let’s capitalize on the moment to demand policies that reward these grassroots makers instead of Wall Street’s billionaire takers.

4) “Tax cuts drive economic growth for all.”

They always claim that freeing corporations from the “burden” of taxes will encourage CEOs to invest in worker productivity and — voila — wages will miraculously rise. This scam has never worked for anyone but the scammers, and it’s now obvious to the great majority of workers that the best way to increase wages… is to increase wages!

Enact a $15 minimum wage and restore collective bargaining. Workers will pocket more and spend more, and the economy will rise.

Percolate-up economics works. Trickle-down does not.

OtherWords columnist Jim Hightower is a radio commentator, writer, and public speaker. Distributed by OtherWords.org.

Pushy spectators

“It said that the spectators at Boston will not let you drop out, they just push you back on the course.’’

— John Priester, after the 2002 Boston Marathon

The 125th Boston Marathon will be held on Monday, Oct. 11, assuming that road races are allowed as part of the Massachusetts reopening plan. In pre-COVID-19 times the marathon happened in April and presumably will again.

Nature and abstraction

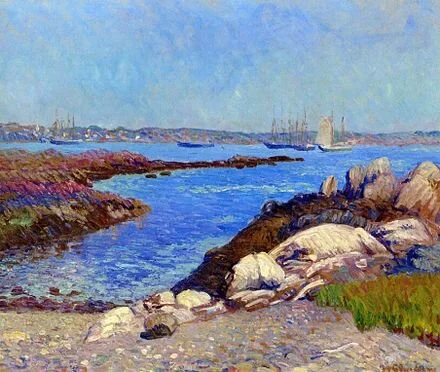

“Portsmouth (N.H.) Harbor Salt Pile’’ (archival silver gelatin print), by Carl Hyatt, a Portsmouth-based photographer, in the group show “Abstract Nature,’’ through April 24 at Cove Street Arts, Portland, Maine

The gallery explains that the show explores “the abstraction of nature through archival and digital prints. The exhibit title seems like a contradiction on the surface: abstraction is a manmade concept, thus nature on its own can't be abstract. However, abstraction as an art form elevates the essence of its subject by manipulating or removing parts of it.’’

Portsmouth Harbor, New Hampshire by William James Glackens (1909)