Llewellyn King: Alternative energy is disrupting world order

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Glance up and around and you’ll know the horizon is changing. From Canada to South Africa, Brazil to China, windmills and solar panels are telling a story of change.

In the United States, the landscape is collecting a kind of 21st-Century raiment. Wind farms, solar farms, and just stray windmills and solar panels on roofs are signaling something big and different.

When they were making Tom Jones in 1963, the very funny film based on Henry Fielding’s classic novel, the big problem was finding English villages that dated from the 18th Century and still looked it. The filmmakers found plenty of appropriate villages, but all the skylines were despoiled with television aerials. No filmmaker today can avoid windmills and solar panels, and computer graphics will have to come to the rescue for period dramas.

Alexander Mirtchev, a respected member of the Washington foreign-policy establishment and vice chairman of the Atlantic Council, in a new book based on a study he conducted for the Wilson Center, names this changed horizon for what it is: a megatrend. In doing this Mirtchev joins other megatrend energy spotters of the past, including environmentalist Amory Lovins and economist Daniel Yergin. Mirtchev’s book is titled The Prologue: The Alternative Energy Megatrend in the Age of Great Power Competition.

Energy has been shaping society and the relationship between nations since humans switched from burning wood to coal. The next step after that was the Industrial Revolution, ushering in what might be called “the first megatrend.”

Mirtchev builds on how energy supply changes relationships and looks to a future where the balance of power could be upended, and energy production could affect neighbors in new ways. For example, I have noted, the Irish are unhappy about British nuclear activity across the Irish Sea. There also is tension along the border between Austria and Slovakia: The Slovaks favor a nuclear future, and the Austrians are into wind and opposed to any nuclear power. As a result, windmills line the Austrian side of this central European border.

Mirtchev’s book is a serious work by a serious scholar that pulls together the impact of alternative energy on national security, the interplay between great powers, and the changing landscape between great powers and a few lesser ones. It is wonderfully free of the idealistic tropes about alternative energy as a morally superior force.

There also are changes within countries. Recently, I wrote about how Houston — the holy of holies of the oil industry — is seeking to rebrand the oil capital as a tech mecca as well as holding onto its oil and gas status as those decline.

If you look at the world, you can see how President Biden can stand up to Saudi Arabia in a way that other presidents couldn’t do. Saudi oil reserves don’t mean what they once did. They aren’t as essential to the future of the world as they once were. There is more oil around and the trend is away from oil. Historic coal exporters, such as Poland, Australia, South Africa and the United States, are losing their markets.

Other losses, including U.S. technological dominance in energy technology, are more subtle. For example, although jubilation over solar and wind is widely felt in the United States by environmentalists, it should be tempered by the fact that solar cells and wind turbines are being provided by China. China has seized manufacturing dominance in alternative energy, endangering national security for dependent countries.

Mirtchev’s arguments have found powerful endorsements. A number of big-name, international security thinkers have come forward to endorse the concept of a realignment caused by the megatrend of alternative energy. These range from Henry Kissinger to a who’s who of foreign-policy stalwarts here and in Europe.

James L. Jones, retired Marine general and President Obama’s national-security adviser, said, summing up thoughts expressed by a full panoply of experts, “ ‘The Prologue’ offers a valuable new framework for international strategic action.”

Retired Adm. James G. Stavridis, an executive of the Carlyle Group and other enterprises, said the book is “a masterpiece of original thought, and it should be must-reading in universities and war colleges.”

Who would have thought of the wind and sun as players in the rivalry between nations or that they would spearhead a megatrend?

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Wind turbines at Lempster Mountain, New Hampshire

Historic shots

“I now live in the town of Concord, Massachusetts, not far from the Old North Bridge, where the American Revolution began. Whenever I take visitors to see the monument, and stand before the marble shaft (above) reading that lovely inscription which commemorates ‘the shot heard round the world,’ I think privately of Bobby Thomson’s (below) home run.’’

From Doris Kearns Goodwin’s (born 1943) Wait Till Next Year: A Memoir

Bobby Thomson (1923-2010) in 1951. The "Shot Heard 'Round the World" was a game-winning home run by New York Giants outfielder and third baseman Bobby Thomson off Brooklyn Dodgers pitcher Ralph Branca at the Polo Grounds in New York City on Oct. 3, 1951, to win the National League pennant. Thomson's three-run homer came in the ninth inning of the third game of a three-game playoff for the pennant in which the Giants trailed, 4–1 entering the ninth, and 4–2 with two runners on base at the time of Thomson's at-bat.

'Ever-evolving landscapes'

From Jeesoo Lee’s show “Moving Scenery’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston June 2-June 27.

The gallery says:

“Through the process of layering, cutting, and reattaching materials, Lee combines passing moments in time and the physical spaces in which they have occurred. Her solo exhibition captures the fleetingness of memory. Lee weaves poignant recollections such as ‘the sound of a young son’s laughter when he opens his eyes in the morning’ or ‘the anguish of a friend who has unexpectedly lost a loved one’. The work portrays these moments, both the intense and the mundane, to combine and form ever-evolving landscapes. Her work is based on psychological states of being which are then redefined through the physicality of her material.’’

'In the horizon of my mind'

Packed in my mind lie all the clothes

Which outward nature wears,

And in its fashion's hourly change

It all things else repairs.

In vain I look for change abroad,

And can no difference find,

Till some new ray of peace uncalled

Illumes my inmost mind.

What is it gilds the trees and clouds,

And paints the heavens so gay,

But yonder fast-abiding light

With its unchanging ray?

Lo, when the sun streams through the wood,

Upon a winter's morn,

Where'er his silent beams intrude

The murky night is gone.

How could the patient pine have known

The morning breeze would come,

Or humble flowers anticipate

The insect's noonday hum,—

Till the new light with morning cheer

From far streamed through the aisles,

And nimbly told the forest trees

For many stretching miles?

I've heard within my inmost soul

Such cheerful morning news,

In the horizon of my mind

Have seen such orient hues,

As in the twilight of the dawn,

When the first birds awake,

Are heard within some silent wood,

Where they the small twigs break,

Or in the eastern skies are seen,

Before the sun appears,

The harbingers of summer heats

Which from afar he bears.

— “The Inward Morning,’’ by Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862)

Robert P. Alvarez: Ga. voter law is an attack on my Catholic faith.

Outcome of the 2020 presidential election in Georgia, with blue signifying areas (especially cities) that voted for Biden and red for Trump

—Graphic by AdamG2016

Via OtherWords.org

I believe in God and in the right to vote. Georgia’s recent election bill doesn’t just feel like an attack on democracy — it feels like an attack on my faith.

The bill, formally SB 202, infamously makes it illegal to give people food or water while they’re waiting in line to cast their ballot. Providing food for the hungry and water for the thirsty are tenets of my Catholic faith.

So is standing with the marginalized. People don’t like to bring race into the conversation, but we have to be honest about how this bill harms people of color.

In Georgia neighborhoods that were 90 percent or more white, the average wait time to vote was around five minutes in last year’s elections. For neighborhoods that were 90 percent or more people of color, the wait time was about an hour. Some voters waited up to 11 hours.

Georgia’s new law seems designed to make these lines longer — and to punish anyone who tries to make them more comfortable. This disproportionate impact on Black, Latino, Native, and Asian communities isn’t an accident. It’s the result of public policy.

Long lines make people less likely to vote in future elections. Republicans know this. That’s why these long lines are concentrated in areas where voters are more likely to cast their ballots for Democrats.

For many voters of color, the ballot box is how we advocate for our needs — and how we defend ourselves against legislation that might harm us. Make no mistake, this bill is about silencing voters of color and chipping away at our political power.

The new law also chops the period of time when voters can request an absentee ballot in half, imposes stricter voter ID requirements for mail-in voting, and slashes the number of locations where voters can cast a ballot.

More worryingly still, it strips control of the state’s election board from Georgia’s secretary of state — and gifts it instead to the Republican-controlled state legislature.

Last year, Georgia’s Republican Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger refused President Trump’s calls to “find” 11,000 more votes for the president, who lost the state. Now, by giving themselves power over the board, Georgia Republicans are plainly laying the groundwork to decertify any future election results they don’t like.

The GOP used to shout their commitment to religious freedom, the rights of businesses, and freedom of speech from rooftops. Now, with their wide net of voter suppression drawing the condemnation of faith groups as well as businesses, they’re stumbling over their own hypocrisy. When Georgia-based businesses like Coca-Cola and Delta spoke out against these new laws, Republicans tried to raise their taxes.

To top it all off, Republicans, including Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, are now telling businesses to “stay out of politics.”

That’s rich coming from McConnell, a lifelong defender of corporate “speech” whose super PAC took in an unbelievable $475 million from corporations last year alone. It’s like if businesses do anything other than write checks, Republicans cry “cancel culture.” Give me a break.

GOP lawmakers are pushing hundreds of bills like Georgia’s in nearly every state in the country. These coordinated attacks on voting rights will inevitably leave poor people and people of color vulnerable to harmful public policy.

As a Catholic, I’m deeply offended by this assault on our democracy. No matter what your faith is, you should be, too.

Robert P. Alvarez is a media relations associate at the Institute for Policy Studies.

'Equal to the sky'

Post Office Square in Boston’s Financial District

“To paint one rose equals a life in that place

and on the thorny path outside

one cathedral is equal to the sky.’’

— “Goodbye Post Office Square,’’ by Boston-based poet Fanny Howe

Time servers and devoted teachers

Providence’s Classical High School

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The endless standoff between the Providence Teachers Union and would-be reformers in state government reminds me again of why I don’t like public-employee unions. They become political organizations and rigid economic- interest groups, rife with conflicts of interest involving elected officials (to whom they can give or withhold campaign cash). That isn’t to say that teachers shouldn’t have rigorous Civil Service-style protections.

For some reason, the latest standoff reminds me of when I sat right behind two Providence teachers on a train coming back from New York 30 years ago. All that the duo, who looked about 40 years old, talked about were their pensions. Of course, there are many devoted teachers in the Providence public schools (which my kids attended) but also too many time servers like my fellow passengers that day.

Early Boston art

A silver porringer created by Boston silversmith John Coney, c. 1710

“Some want to rob the Puritans of art….There were ten silversmiths in Boston before there was a single lawyer. People forget all those things.’’

— Robert Frost in his commencement address “What Became of New England’’ at Oberlin College in 1937.

After looking deep inside

“Self-Portrait (BC Series)’’ (watercolor on Arches paper), by Hannah Wilke (1940-1993), through April 10, at the LaiSun Keane Gallery, Boston.

The ecological empires of oaks, Charter and otherwise

Large white oak

Adapted From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

That Southern New England has so many kinds of trees helps explain much of its ecological richness. Oaks are among the most common. I always thought of them as rather boring, especially because their leaves turn blandly brown in the fall and tend to hang on until spring. (I do have fond memories from childhood of tree houses in them and acorn fights.) But Douglas W. Tallamy, an entomologist at the University of Delaware, talks up oaks in his new book, The Nature of Oaks: The Rich Ecology of Our Most Essential Native Trees.

Mr. Tallamy explains how oaks support more life-forms than any other North American tree genus. They provide food (especially acorns and caterpillars) and protection for birds, mammals (consider squirrels, racoons, bears and bats), insects and spiders, as well as enriching soil, holding rainwater and cleaning the air. And they can live for hundreds of years.

“There is much going on in your yard that would not be going on if you did not have one or more oak trees gracing your piece of planet earth,” he writes in the book, which shows us what’s happening within, on, under, and around these trees.

Mr. Tallamy offers advice about how to plant and care for oaks, and information about the best oak species for your area.

Hug your oak trees and/or plant some. (And if they get uprooted in a storm, they make about the best firewood.) Fewer lawns, more oak trees, please. Now that it’s April, those remaining ugly brown leaves from last year will soon be pushed out and we’ll soon be enjoying the shade under oaks’ expansive canopies.

“The Charter Oak” (oil on canvas), by Charles De Wolf Brownell, 1857. It’s at the Wadsworth Atheneum, in Hartford.

The Charter Oak was an unusually large white oak tree in Hartford. It grew from the 12th or 13th century until it fell during a storm in 1856. According to tradition, Connecticut's Royal Charter of 1662 was hidden within the hollow of the tree to thwart its confiscation by the English governor-general. The oak became a symbol of American independence and is commemorated on the Connecticut State Quarter.

Photos of acorns by David Hill

'Doorway to the sea'

“Christina’s World,’’ by Andrew Wyeth (1917-2009), the very popular American “realist “ painter. The woman in the painting, Anna Christina Olson (1893-1968), had a degenerative muscular disorder that prevented her from walking after she was 30. She refused to use a wheelchair, so she would crawl. The house and barn are in Cushing, Maine, where the Wyeth family had a summer house.

“The world of New England is in that house – spidery, like crackling skeletons rotting in the attic – dry bones. It’s like a tombstone to sailors lost at sea, the Olson ancestor who fell from the yardarm of a square-rigger and was never found. It’s the doorway of the sea to me, of mussels and clams and sea monsters and whales.’’

-- Painter Andrew Wyeth, on the home of his model Christina Olson, in Andrew Wyeth: A Secret Life (1996), by Richard Meryman

The Olson House in 1995. The house and its occupants, Christina and Alvaro Olson, were depicted in paintings and sketches by Wyeth from 1939 to 1968. The house was designated a National Historic Landmark in June 2011. The Farnsworth Art Museum, in Rockland, Maine, owns the house, which is open to the public.

From 'the inner world'

Burdock, originally from Eurasia, and an invasive weed in North America.

“In the April sun that doesn’t yet smell, brown and red birds declaring hunger,

I appear from the inner world — a hell of beetles and voles — appointed to multiply.’’

— From “Burdock,’’ by Carol Frost (born 1948), Massachusetts-born American poet.

At the Cape Ann Museum, honoring a pioneer in promoting equality for women

John Singleton Copley’s (1738–1815) “Portrait of Mrs. John Stevens” (Judith Sargent, later Mrs. John Murray) (oil on canvas), in the show “Our Souls Are by Nature Equal to Yours: The Legacy of Judith Sargent Murray, through May 2 at the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass. This is via the Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Art Acquisition Endowment Fund. Photography ©Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago. This portrait was painted in 1770-1772.

The Cape Ann Museum says:

The show is a collaboration by Cape Ann Museum, the Terra Foundation for American Art and the Sargent House Museum, in Gloucester, to celebrate the Sargent House Museum's 100th anniversary. This exhibit is focused on the life and achievements of Judith Sargent Murray (1751-1820), a Gloucester native and civil-rights advocate. While her brothers were tutored in preparation for college, she educated herself and began writing essays, poems and letters.

Her most famous work, On the Equality of the Sexes, argued that men and women experienced the same world, and therefore deserved the same rights. This essay was first published in 1790, a time when women's rights as a political topic was practically unheard of. Murray also wrote about such other topics as education, politics, theology and money. Her outspoken writing paved the way for future advocates of women's rights.

David Warsh: From eugenics to molecular biology

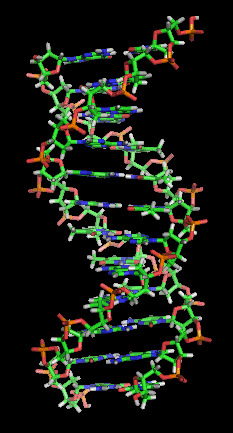

Representation of the now famous “Double Helix’’: Two complementary regions of nucleic acid molecules will bind and form a double helical structure held together by base pairs.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It was so long ago that I can no longer remember with any precision the pathways along which the book started me towards economic journalism. What I know with certainty is that The Double Helix: A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA (Athenaeum), by James Watson, changed my life when I read it, not long after it was first published, in 1968. Watson’s intimate account of his and Francis Crick’s race with Linus Pauling in 1953 to solve the structure of the molecule at the center of hereditary transmission was thrilling in all its particulars. I went into college one way and came out another, with a durable side-interest in molecular biology.

Thus when Horace Freeland Judson’s The Eighth Day of Creation: Makers of the Revolution in Modern Biology (Simon and Schuster), came along, in 1979, I marveled at Judson’s much more expansive collective portrait of the age. And when Lily Kay’s The Molecular Vision of Life: Caltech, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the Rise of the New Biology (Oxford) came out in, in 1993, I was quite taken by the institutional background it supplied.

Kay told the story of how the mathematician Warren Weaver in the 1930s decisively backed the Rockefeller Foundation away from its ill-considered funding backing of the fringes of the eugenics movement – human engineering through controlled breeding – by initiating “a concerted physiochemical attack on [discovering the nature of] the gene… at the moment in history when it became unacceptable to advocate social control based on crude eugenic principles and outmoded racial theories.”

Not until 1938 would Weaver describe his campaign as “molecular biology.” In the dozen years after 1953, Nobel prizes were awarded to 18 scientists for investigation of the nature of the gene, all but one of them funded by the Rockefeller Foundation under Weaver’s direction.

For the past couple of weeks I have been reading Code Breaker: Jennifer Doudna, Gene Editing, and the Future of the Human Race (Simon & Schuster, 2021), by Walter Isaacson. Doudna, you may remember (pronounced Dowd-na), shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry last autumn with collaborator Emmanuelle Charpentier “for the development of a method of genetic editing” known as the CRISPR/Cas 9 genetic scissors. The COVID pandemic prevented the journeys to Stockholm that laureates customary make to deliver lectures and accept prizes. Medalists will be recognized at some later date. At that point, expect the significance of the new code-editing technologies to be emphasized. The new know-how recognized in 2020 Prize in Chemistry is probably the most important breakthrough since the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine went to Crick, Watson and Maurice Wilkins, in 1962. Instead of the sterilization and other forceful measures envisaged by the eugenics movement, CRISPR promises to gradually eliminate hereditary disease.

Three themes emerge from Code Breaker. The first is how much has changed with respect to gender, in biological science at least. X-ray crystallographer Rosalind Franklin died in 1958, four years before she might have shared the prize. (Dead persons are not eligible for the award.) She was cruelly disparaged in Watson’s book, despite the fact that her photographs were crucial to the discovery of the helical structure of the gene.

Opportunities for female scientists had begun to open up by the time that The Eighth Day was published, but women hadn’t yet reached levels of professional accomplishment such that their photographs would appear except rarely in pages dominated by White males. Doudna, born in 1964, and Charpentier, born in 1968, encountered abundant opportunities.

A second theme, less stressed, underscores the extent to which the tables have turned over the last century with respect to the importance attached by scientists to race. Strongly held view about the dispersion of genetic endowments across various populations are nothing new, but, as The New York Times put it a couple of years ago, “It has been more than a decade since James D. Watson, a founder of modern genetics, landed in a kind of professional exile by suggesting that black people are intrinsically less intelligent than whites.”

A third theme, the main story, is Doudna’s decision, as a graduate student in the 1990s, to study the less-celebrated RNA molecule that performs work by copying DNA-coded information in order to build proteins in cells. All this is clearly explained in Isaacson’s book, in relatively short chapters and sub-sections. The effect of this mosaic technique is to briskly move the story along.

After many twists and turns, Doudna and Charpentier showed in June 2012 that “clustered regularly interspersed palindromic repeats” (hence the easy-to-remember-and- pronounce acronym CRISPR), “Cas9” being a particular associated enzyme that did the cutting work, could be made to cut and replace fragments of genes work in a test tube. Within six months, five different papers appeared showing that such scissors would also work in live animal cells.

The famed Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, in Cambridge, where much important biomedical and genomic research is conducted.

An epic patent battle ensued, involving claims to various ways in which CRISPR systems could be used in different sorts of kinds of organisms. A nearly metaphysical argument developed: Once Doudna and Charpentier demonstrated that the technique would work on bacteria, was it “obvious” that it would work in human cells? Rival claimants included Doudna, of the University of California at Berkeley; Charpentier, of Umeå University, Sweden; geneticist George Church, of the Harvard Medical School; and molecular biologist Feng Zhang, of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard.

Church and Zhang are colorful characters with powerful minds and different scientific backgrounds. Their complicated competition with Doudna and Charpentier is said to reprise the race of Watson and Crick with Pauling forty years before. Well-disposed toward all four principals, author Isaacson spends a fair amount of effort interpreting their rival claims. At the end of the book, he expresses the hope that Zhang and Church might one day share a Nobel Prize in Medicine for their CRISPR work.

If there is a better all-around English-language journalist of the last fifty years than Isaacson, I don’t know who that might be. Born in 1952, he grew up in New Orleans, went to Harvard College and then Oxford, as a Rhodes Scholar, before beginning newspaper work. He joined Time magazine as a political reporter in 1978; by 1996 he was its editor. To that point he had written two books (the first with Evan Thomas): The Wise Men: Six Friends and the World They Made; (1986); and Kissinger: A Biography (1992).

In 2001 Isaacson left Time to serve as CEO of CNN. Eighteen months later he was named president of the Aspen Institute. There followed, among other books, biographies of Benjamin Franklin (2003), Albert Einstein (2007), Steve Jobs (2011) and Leonardo da Vinci (2017). He resigned from the Aspen Institute in 2017 to become a professor of American History and Values at Tulane University.

As editor of Time, Isaacson took a call in 2000 from Vice President Al Gore, asking on behalf of President Clinton that the visage of National Institutes of Health Director Francis Collins be added to that of biotech entrepreneur J. Craig Venter on the cover of a forthcoming issue. A crash program to sequence the human genome was threatening to break apart after the abrasive Venter devised a cheaper means and formed a private company.

Isaacson consulted his sources, including Broad Institute president Eric Lander, a friend from Rhodes Scholar days, and complied. Science journalist Nicholas Wade wrote the story. At least since then, Isaacson has been involved at the highest levels in the story of molecular biology. He is uniquely well-qualified to describe the most recent segment of its arc, and, in the second half of the book, to lay out the many thorny social choices that lie ahead.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran. © 2021 DAVID WARSH, PROPRIETOR

Walter Isaacson

Phil Galewitz: Vermont giving priority to minorities for COVID vaccinations

Starting April 1, Vermont has explicitly been giving Black adults and people from other minority communities priority status for vaccinations. Although other states have made efforts to get vaccine to people of color, Vermont is the first to offer them priority status, said Jen Kates, director of global health and HIV policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). (Kaiser Health News is an editorially independent program of KFF.)

All Black, Indigenous residents and other people of color who are permanent Vermont residents and 16 or older are eligible for the vaccine.

It will be a short-term advantage, since Vermont opens COVID-19 inoculations to all adults April 19.

Still, Vermont health officials say they hope that the change will lower the risk for people of color, who are nearly twice as likely as whites to end up in the hospital with COVID-19. “It is unacceptable that this disparity remains for this population,” Dr. Mark Levine, M.D.,

Vermont’s health commissioner, said at a recent news conference.

But providing priority may not be enough to get more minority residents vaccinated — and could send the wrong message, some health experts say.

“Giving people of color priority eligibility may assuage liberal guilt, but it doesn’t address the real barriers to vaccination,” said Dr. Céline Gounder, an infectious-diseases specialist at NYU Langone Health and a former member of President Biden’s COVID advisory board. “The reason for lower vaccination coverage in communities of color isn’t just because of where they are ‘in line’ for the vaccine. It’s also very much a question of access.”

Vaccination sites need to be more convenient to where these targeted populations live and work, and more education efforts are necessary so people know the shots are free and safe, she said.

“Explicitly giving people of color priority for vaccination could backfire,” Gounder said. “It could give some the impression that the vaccine is being rolled out to them first as a test. It could reinforce the fear that people of color are being used as guinea pigs for something new.”

Dr. Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association, said that’s why he has opposed using race as a risk factor to determine covid vaccine eligibility.

But he sees signs that vaccine hesitancy is declining nationally and called Vermont’s new approach “admirable.” Still, he said, states should continue to use a range of options to get vaccines to minority communities, such as providing vaccination sites in Black neighborhoods and places that residents trust, like churches.

No state is achieving equity in its vaccine distribution, said KFF’s Kates.

“People of color, whether they be Black or brown, are being vaccinated at lower rates compared to their representation among covid cases and deaths, and often their population overall,” she said.

Blacks make up about 2 percent of Vermont’s population and 4 percent of its COVID infections, but they have received 1 percent of the state’s vaccines, according to KFF.

“Since states are really not doing well on equity, other strategies are welcome at this point,” said Kates.

Yet, there’s another reason public health officials have balked at explicitly giving people of color vaccine priority. “It could be politically sensitive,” she said.

Phil Galewitz is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Phil Galewitz: pgalewitz@kff.org, @philgalewitz

Chris Powell: Conn. can be a golden state again

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut's lawns are turning green again. Robins are scouring them for worms, which are returning to the surface despite the high taxes and accusations of racism above ground. Redwings are trilling madly over the ponds, brooks, and marshes.

Daffodils and crocuses are in bloom. Leaf buds on the trees are swelling. Many days are blessedly sunny and mild.

Kids are going back to school -- not that anyone ever will be able to tell from their test scores, but at least they're out of the house again. Virus epidemic restrictions are fading as people get vaccinated. Money for state government doesn't just grow on trees now; it rains down from the heavens as never before.

Indeed, in another month Connecticut, in its natural state, may become, as it does for a while every year, nearly the most beautiful place on Earth, just as it may be climatically the safest and most temperate.

Politically there will be as much to complain about as ever, but consider the alternatives.

Connecticut people wintering in Florida, many of them tax exiles, are planning to return north to escape the summer heat down there, as well as the alligators, Burmese pythons, lizards, and insects as big as pumpkins.

Texas, another state without an income tax that lately has drawn many people from Connecticut, was also without electricity and drinking water for much of February, and soon its heat and humidity may make its Northern transplants miss snow.

Tennessee, which also manages without an income tax, lately has been suffering floods and tornadoes on top of country music.

California, once the "golden state," has been impoverished by bad public policy and is being overwhelmed not just by taxes but also by poverty, homelessness, drugs, illegal immigration, and political correctness. State government there seems oblivious as many middle-class people depart or sign petitions to remove the governor.

Maybe the recent arrivals in Connecticut who hurriedly escaped New York can give their new neighbors some valuable reflections.

Of course no place is perfect, but nothing about geoe agraphy or climate stands in the way of Connecticut's regaining the advantages it had before it succumbed to the old corruption of prosperity -- the belief that prosperity is the natural order of things, not something that had to be earned and must be constantly re-earned. Whether Connecticut can restore its prosperity is entirely a political question, a question of whether its people retain enough civic virtue to discern and assert the public interest over the government class and other special interests.

If glorious spring in Connecticut cannot persuade people that such an undertaking is worthwhile, nothing can. Those who often threaten to leave but haven't left yet should take a bigger part in the struggle.

xxx

WHERE'S THE RACISM?: Maybe the people who are accusing Connecticut's suburbs of being racist will explain how it is racist not to want to be stuck with a school system like Hartford's, whose chronic absenteeism rate among students approaches 50 percent.

It's not the fault of school administrators and teachers. The other day The Hartford Courant reported about the daily circuses being staged by city schools to entice students to show up. The circuses seem to be helping a little, but it is not cynical to ask: Where are the parents of the chronically absent kids? Are racists blockading their homes?

Is the exclusive zoning in many suburbs why so many city kids have been skipping school?

Zoning doesn't know anyone's race. Zoning does have a good idea of people's financial circumstances and the financial capacity of the town that enacted it, and it wonders: How does any town benefit from a large population of unparented and desperately disadvantaged children who run school performance way down and expense way up?

Complaints of "structural racism" don't answer that question. They distract from it and prevent any inquiry into why so many children have no parents and are so neglected.

If structural racism was really the problem in Connecticut, laws long in place would have solved it already. But structural poverty remains to be addressed, and, worse, remains even to be acknowledged.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

To delight them downstream

The Charles River at the Medfield-Millis (Mass.) town live

Dark brown is the river,

Golden is the sand.

It flows along for ever,

With trees on either hand.

Green leaves a-floating,

Castles of the foam,

Boats of mine a-boating -

Where will all come home?

On goes the river

And out past the mill,

Away down the valley,

Away down the hill.

Away down the river,

A hundred miles or more,

Other little children

Shall bring my boats ashore.

— “Where Go the Boats,’’ by Robert Louis Stevenson (1850-1894), Scottish novelist, poet and travel writer

Satellite image of the Connecticut River depositing silt into Long Island Sound

'As it really is'

Fenway Park during a 2010 game vs. the Philadelphia Phillies

“For serious looking at baseball there are few places better than Fenway Park. The stands are close to the playing field, the fences are a hopeful green and the young men in their white uniforms are working on real grass, the authentic natural article; under the actual sky in the temperature as it really is. No Tartan Turf. No Astrodome. No air conditioning. Not too many pennants over the years but no Texans either.’’

— From crime writer Robert B. Parker’s (1932-2010) novel Mortal Stakes (1975)

Fenway Park during the 2013 World Series pregame events

If you're ever in a jam, here I am

“Getting to Know You’’ (encaustic painting), by Nancy Whitcomb

Good place to scare people from

Stephen King’s rather spooking-looking house in Bangor, Maine, one of many mansions built in the city during Bangor’s 19th Century heyday as a lumber center

“I think one of the reasons that Stephen King’s stories work so well is that he places his stories in spooky old New England, where a lot of American folk legends come from.’’

— Ted Naifeh, American comic-book author and illustrator

Paul Bunyan statue in Bangor