Closing on final approval of Vineyard Wind 1

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

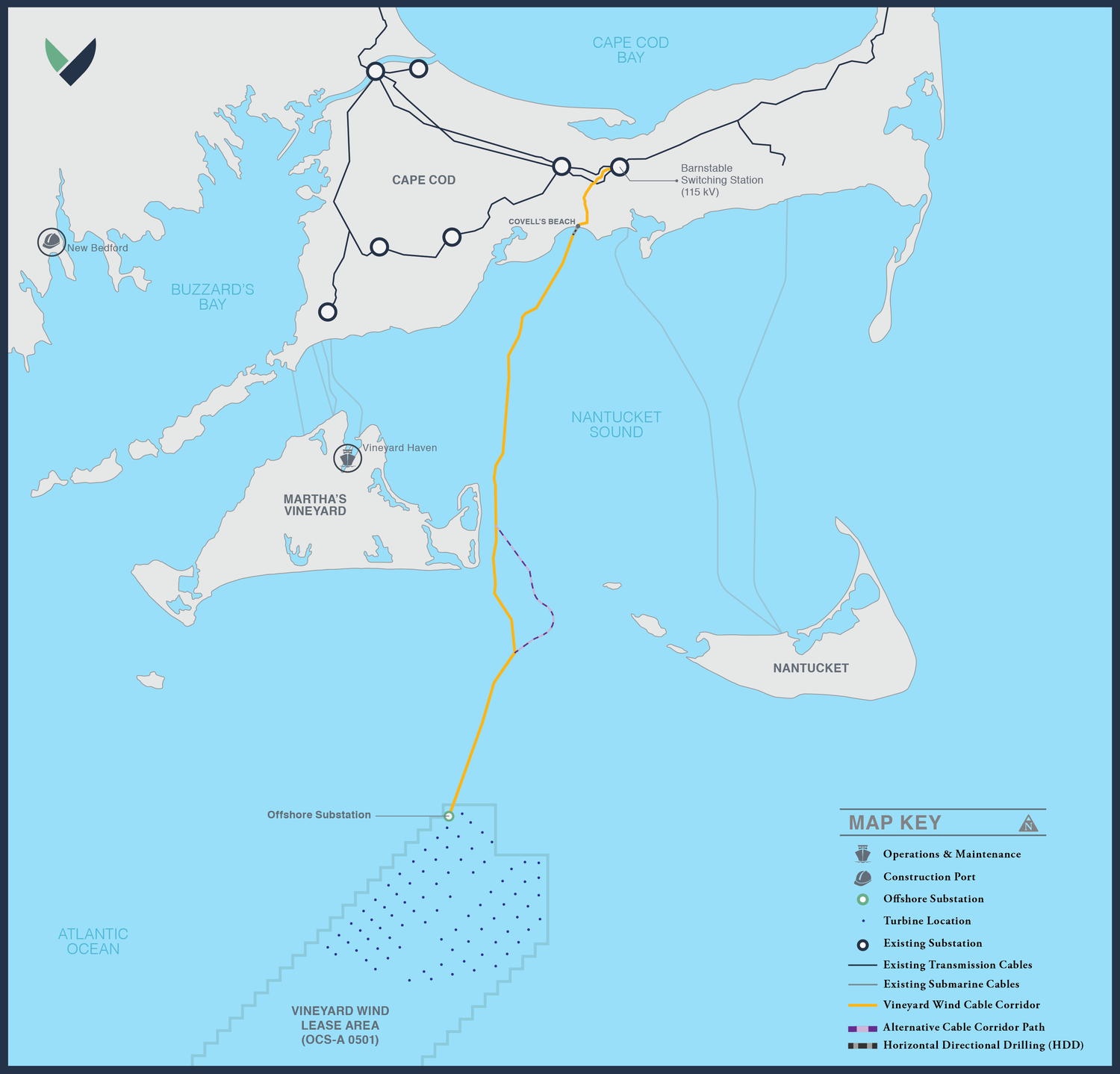

“Avangrid recently received the Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) for Vineyard Wind 1 from the U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), the last step before a Record of Decision (ROD) that would jumpstart approval for the project to begin construction.

“A joint venture between Avangrid Renewables and Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners (CIP), Vineyard Wind seeks to establish a massive offshore wind farm about 15 miles off the coast of Martha’s Vineyard.“Dennis V. Arriola, CEO of Avangrid, commented, “We are one step closer toward realizing this historic clean energy project and delivering cost-effective clean energy, thousands of jobs and more than a billion dollars in economic benefits to Massachusetts.” The project would generate electricity to power over 400,000 residences and businesses in Massachusetts, while also reducing electricity rates, carbon emissions, and creating new job opportunities.

“The New England Council looks forward to the progress Avangrid makes in developing this project for the region. Read more from the Hartford Business Journal and Avangrid’s press release.’’

In Greater Boston, the intersection of the pandemic and immigration

Cambridge Hospital, part of the Cambridge Health Alliance

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

CAMBRIDGE, Mass.

A year into the global pandemic, we are grappling with the scale of its impact and the conditions that created, permitted and exacerbated it. For those of us in the mental health field, tentative strides toward telepsychiatry pivoted to a sudden semi-permanent virtual health-care delivery system. Questions of efficacy, equity and risk management have been raised, particularly for underserved and immigrant populations. The structures of our work and its pillars (physical proximity, co-regulation, confidentiality, in-person crisis assessment) have shifted, leading to other unexpected proximities and perhaps intimacies—seeing into patients’ homes, seeing how they interact with their children, speaking with patients with their abusive partners in the room, listening to the conversation, and patients seeing into our lives.

As the pandemic crisis morphs, it is unclear if we are at the point to do meaningful reflective work, but for now, I offer some thoughts through the lens of my work at Cambridge Health Alliance (CHA), an academic health-care system serving about 140,000 patients in the Boston Metro North region.

CHA is a unique system: a teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School, which operates the Cambridge Public Health Department and articulates as “core to the mission,” health equity and social justice to underserved, medically indigent populations with a special focus on underserved people in our communities. Within the hospital’s Department of Psychiatry, four linguistic minority mental-health teams serve Haitian, Latinx, Portuguese-speaking (including Portugal, Cape Verde and Brazil) and Asian patients.

While we endeavour to gather data on this across CHA, anecdotal evidence from the minority linguistic teams supports the existing research suggesting that immigrant and communities of color are bearing a disappropriate impact of COVID-19 in multiple intersecting and devastating ways: higher burden of disease and mortality rates, poorer care and access to care, overrepresentation in poorly reimbursed and “front-facing” vulnerable jobs such as cleaning services in hospitals and assisted care facilities, personal care attendants and home health aides, and overrepresentation in industries that have been hardest hit by the pandemic such as food service, thereby facing catastrophic loss of income.

These patients also face crowded multigenerational living conditions and unregulated and crowded work conditions. These “collapsing effects” are further exacerbated by reports from our patients that they are also being targeted by hateful rhetoric such as “the China virus” and larger anti-immigrant sentiment stoked by the Trump administration and the accompanying narrative of “economic anxiety” that has masked the racialized targeting of immigrants at their workplaces and beyond.

Telehealth. As we provide services, we have also observed that, despite privacy concerns, access to and use of our care has expanded due to the flexibility of telehealth. Patients tell us that they no longer have to take the day off from work to come to a therapy appointment and have found care more accessible and understanding of the demands of their material lives.

Some immigrant patients report that since they use phone and video applications to stay in touch with family members, using these tools for psychiatric care feels normative and familiar. For deeply traumatized individuals, despite the loss of face-to-face contact, the fact that they do not have to encounter the stresses inherent in being in contact with others out in the world has made it more possible for them to consistently engage in care with reduced fear as relates to their anxiety and/or PTSD. These are interesting observations as we try to tailor care and understand “what works for whom.”

Immigrant service providers. Another theme in the dynamics of care during the pandemic is found in the experiences of immigrant service providers whose work has been stretched in previously unrecognizable ways—and remains often invisible.

Prior to the pandemic, for example, CHA had established the Volunteer Health Advisors program, which trains respected community health workers, often individuals who were healthcare providers in their home country, who have a close understanding of the community they serve. They participate in community events such as health fairs to facilitate health education and access to services and can serve as a trusted link to health and social services and underserved communities.

What we have seen during the pandemic is even greater strain on immigrant and refugee services providers who are often the front line of contact. We have provided various “care for the caregiver” workshops that address secondary or vicarious trauma to such groups such as medical interpreters often in the position of giving grave or devastating news to families about COVID-19-related deaths as well as school liaisons and school personnel, working with children who may have lost multiple family members to the virus, often the primary breadwinners, leaving them in economic peril.

While such supportive efforts are not negligible, a public system like ours is vulnerable to operating within crisis-driven discourse and decision making. With the pandemic exacerbating inequities, organizational scholars have noted in various contexts that a state of crisis can become institutionalized. This can foreclose efforts at equity that includes both patient care as well as care for those providing it. The challenge going forward will involve keeping these issues at the forefront of decisions regarding catalyzing technology and the resulting demands on our workforce.

Diya Kallivayalil , Ph.D., is the director of training at the Victims of Violence Program at the Cambridge Health Alliance and a faculty member in the Department of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School.

Something in common

The town common, also called the town green, in Douglas, Mass.

“The idea of land held in common, as part of a manifest, workday covenant with the Bestower of a new continent, has permanently imprinted the maps of these towns, and lengthens the perspectives of those who live within them.”

-- John Updike (1931-2009), famed and prolific writer, in “Common Land,’’ in New England: The Four Seasons, edited by Arthur Griffin. Updike spent most of his adult life in towns on the Massachusetts North Shore.

Robert Whitcomb: What let Flagler revolutionize Florida

A 1913 advertisement extols the many advantages of traveling on the Florida East Coast Railway, the "New Route to the Panama Canal".

From a talk I gave on March 17 to a Florida group

— Robert Whitcomb

‘When looking back at Henry Flagler's life, George W. Perkins, of J.P. Morgan & Co., reflected,

"But that any man could have the genius to see of what this wilderness of sand and underbrush was capable and then have the nerve to build a railroad there, is more marvelous than similar development anywhere else in the world."

My interest in railroads goes back to dim memories of taking the train to see relatives in Florida, other parts of the South and the Midwest as a child. Traveling in those Pullman compartments was exciting! I wrote a master’s thesis on East Coast railroads while in graduate school. And I’ve been fortunate to live in places with passenger trains, mostly in the Northeast but also when we lived in Europe in the 1980s. I love passenger trains and I’m happy to see that they’re making a comeback in Florida.

The dramatic story of the Florida East Coast Railway has been told many, many times and is easily available, especially in Palm Beach. So I’ll just give a brief chronology of it and then, of more interest to me, anyway, talk about the social and economic conditions that presaged it and kept it going for so long.

The story of Henry M. Flagler, the railway’s founder, is astonishing: From 1885 to 1913, Flagler built an empire in Florida of cross-promotional railroads, hotels, resorts and steamship lines (with close connections to his trains). His vision led to the creation of many communities, and the great expansion of some already existing ones, such as Jacksonville, from northeast Florida all the way down to Key West, most famously Palm Beach and Miami. And his work led to a huge expansion of commerce in the state, most notably tourism and agriculture. No wonder you see his name everywhere: Consider Flagler College, Flagler County, Flagler Memorial Bridge, Flagler Beach, etc., etc.

There were other great Florida early developers, mostly notably Henry Plant on the state’s west coast, but Flagler was the most important.

Henry Morrison Flagler was a partner of John D. Rockefeller in the creation, in 1867, in Cleveland, of Standard Oil, one of the greatest Gilded Age corporate behemoths. Of course, Flagler became very rich in the process. He also became very expert in railroad engineering and economics because Standard Oil obviously had to ship its petroleum long distances. The oil was first used primarily for kerosene, followed by oil to run trains, among other things (!), gasoline and other petro products.\

In 1878 he traveled with his first wife, who, like many others in those pre-antibiotic days, had tuberculosis, to winter in Jacksonville. It was then that the potential of Florida, which at that time had a small population and not much of an economy, as a winter resort and year-round agricultural area, started to jump out at him.

Then, after she died, in 1881, he married one of her caregivers, who, by the way, turned out to be crazy.

With this new spouse, he traveled in 1882 to St. Augustine, which he found charming, if a bit bedraggled, and lacking in good hotels and easy and reliable transportation to get there. He saw the promise of Florida and was determined to achieve it. So he gradually withdrew from active management duties at Standard Oil to pursue his Florida interests.

In 1885, he began building the big Ponce de Leon Hotel in St. Augustine. To start to address the region’s transportation issues, he bought railways, most importantly the Jacksonville, St. Augustine & Halifax Railroad, and converted the latter to standard gauge from narrow gauge, which made it much more efficient. This railroad was extended to the south and in 1895 was renamed the Florida East Coast Railway-Flagler System, which revolutionized life on the east coast of Florida.

Meanwhile, he was building up Saint Augustine as a major resort town, including developing three more hotels, and he built more hotels southward toward Daytona, which he reached in 1889.

Then in 1892, he started extending his line much further south. He was encouraged in this effort by the State of Florida’s providing HUGE grants of land to encourage railroad expansion and other development. He took advantage of owning land that had massive potential for developing agricultural, timber, phosphate and other operations – much of the products of which ended up being shipped on his railroad. Pure synergy. Of course, much swamp-draining work was necessary in the process.

By 1894, his railroad reached West Palm Beach, from which he looked east to the big resort opportunities of Palm Beach island. So he built the first version of the Breakers there, as well as the Royal Poinciana.

In 1896 Flagler’s railroad reached then-tiny Miami, which he proceeded to turn into a major winter resort and agricultural area, with big hotels. A major incentive for developing South Florida was that two hard freezes that ravaged the citrus and vegetable crops in most of Florida in the winter of 1894-95 did not affect the area south of Palm Beach. So not only did that make Miami more alluring for winter visitors than, say, Daytona, it promoted the agricultural development of South Florida.

Flagler relentlessly worked to create full-fledged towns that would bring more people and commerce to his businesses. These people included farmers to grow and ship produce, most of it to the north, laborers to develop the area and staff for hotels and resorts. He built schools, brought in utilities, arranged for stores to be built, created parks and even financed churches and cemeteries. It was a mix of enlightened self interest tinctured with philanthropy. Synergy, synergy, synergy!

Meanwhile, he had long been fascinated by the prospect of extending the Florida East Coast Railway to Key West. One of his hopes was that that little city, which for a time had been – bizarrely -- the biggest in Florida, could be turned into a major international port, especially with the coming of the Panama Canal. It never happened, although Miami, which Flagler had a great role in developing, became a major international port. Flagler long saw South Florida as a key area for hemispheric trade, but Miami, not Key West, turned out to be the linchpin.

The first train on what was called the Key West Extension, ran in 1912. Flagler died the next year, with his dream fulfilled.=

The extension was one of the engineering marvels of the age but the great Labor Day Hurricane of 1935 did so much damage that it was abandoned. Now, of course, you can drive on the extension’s exact route.

In any event, the railway went on to prosper with a growing number of passengers, most of them drawn by the sun from the affluent but cold Northeast, Mid-Atlantic and Upper Midwest states, and a hefty freight business, much of it to carry the stuff produced on land granted to the railroad by the state and then sold off for agriculture.

The railroad mostly prospered until the late ‘20s, when the crazily speculative Florida land boom burst; two hurricanes in South Florida didn’t help either. Florida’s railroads suffered mightily, and the Florida East Coast Railway went into bankruptcy protection in 1931. In any event, freight and passenger operations continued, with, it should be said, long-haul trains from New York and the Midwest continuing to use its tracks.

But FEC passenger train service ended in 1968 after very nasty labor disputes. Still, the railway freight business continues and, as I note below, there’s a new FEC passenger train connection.

Of course, the coming of America’s automobile culture and associated construction of many more and better better roads from the 1920s on, and especially the Interstate Highway System in the late ‘50s, took a big bite out of the Florida East Coast Railway.

At the same time, longer life expectancies, the expansion of the middle class, the introduction of Social Security payments and the decades in which corporate pensions (now disappearing except for upper management) were common helped drive a huge increase in people retiring in Florida. When will it end?

Let’s look at some of the factors that enabled Flagler to build his railroad and associated developments in Florida, in addition to the state giving him lots of land for his railway and for associated development.

First was the great wealth he was able to accumulate as a result of the American industrial revolution, which gave him piles of money to spend to build his Florida empire. Part of this technological and economic revolution was development of better steel track and the aforementioned standardized railroad-track gauge. Coal-powered earth-moving equipment to drain swamps and build road beds were also essential, as was the revolutionary effect of the development of machine tools in – The first machine tools were invented.

A machine tool is a machine for handling or machining metal or other rigid materials, usually by cutting, boring, grinding, shearing, or other forms of deformation.

These included the screw cutting lathe, cylinder boring machine and the milling machine. Machine tools made the economical manufacture of precision metal parts possible, although it took several decades to develop effective techniques. Machine tools were obviously very important in train and track making, among other things.

Indeed, Flagler’s Florida empire wouldn’t have happened without what’s called the Second Industrial Revolution, also known as the Technological Revolution.

Advances in manufacturing and production technology enabled the widespread adoption of technological systems such as telegraph and railroad networks, gas and water supply, and sewage systems. The enormous expansion of rail and telegraph lines after 1870 allowed a vastly increased movement of people and ideas. Then came electrical power and telephones.

The Second Industrial Revolution was also, of course, accelerated by rapidly increasing use of oil, the source of Flagler’s wealth.

A synergy between iron and steel, railroads and coal (and petroleum) developed at the beginning of the Second Industrial Revolution. Railroads allowed cheap transportation of materials and products, which in turn led to the production of cheap rails to build more railways. Railroads also benefited from cheap coal for their steam locomotives. Virtuous circle!

Meanwhile, Flagler had learned before his Florida projects how to use the law for maximum benefit. He was an expert in partnership and incorporation laws and in using the U.S. Constitution’s new 14th Amendment, which affirmed equal protection of the laws to all persons, to protect businesses from many lawsuits and even criminal prosecutions. This was especially after a U.S. Supreme Court ruling in the 1886 that said that companies had legal protection as “persons’’—a still controversial ruling.=

Also very helpful to furtherance of his Florida projects was the discovery that mosquitoes spread such diseases as yellow fever and malaria as part of the development of germ theory. Draining swamps near Flagler’s developments and the use of such early pesticides as kerosene (made by Standard Oil!) made promoting Florida as a resort and retirement place easier. And that Florida is flat, while meaning that its wet subtropical climate would produce a lot of swampland, also cut construction costs. Among other things, he didn’t need to build tunnels or do a lot of blasting.

As I implied above, improvements in train engineering and standardization (especially of track gauge) made passenger and freight trains much faster as well as more reliable and comfortable. This made growing and shipping produce, lumber, turpentine, etc. ,to the north much more profitable. Mining and shipping phosphate, of which Florida had a lot as the pile of limestone that it is, was also developed into a major industry. Then there was the expansion of electricity, which enabled safe and bright lighting in buildings and railway cars as well as such new luxuries as fans. Before air conditioning as we know it began on trains, in the 1930s, some passenger trains had primitive cooling systems involving having fans blow are over blocks of ice from New England.

And we shouldn’t underestimate the role of the development of luxurious Pullman sleeper cars and dining cars that were sometimes as good as fancy restaurants. While trains were getting faster, it still was a trip of two or three days from the Northeast and Midwest, and so comfort was important and the Gilded Age nouveau riche had the money to pay for it.

By the way, it’s hard to exaggerate the effect on residential and business development in Florida of modern air conditioning from the 1930s on. But at least electric fans were a start. Anyway, obviously without air conditioning, Florida’s Congo-like summer climate would have kept many winter residents and businesses from becoming year-round ones.

Very important, of course, was the developing role of new refrigeration technologies in preserving the vast amount of produce grown and shipped from Florida by train – a big business for Flagler. At first ice blocks from northern lakes were used on the freight cars. Refrigerated railroad cars created a national industry in vegetables and fruit that could now be consumed far away. The sale of this stuff was a bonanza for Flagler’s empire, which included vast acreages of land that could sold off and turned into large farms.

Flagler’s interest in developing vast tracts for agriculture on land that the state had given him along the route of his railroad was heightened by the development of improved fertilizers (much of which used Florida-mined phosphate!) and better equipment to cultivate and harvest crops.

Fast trains were essential for meeting the burgeoning demand of the rich and middle class in the North for fresh vegetables and fruit in the winter – demand created in part by the arrival of modern advertising.

At the same time, improvements in paper making, presses and inks made producing free-standing brochures and flyers, as well as ads in newspapers and magazines, touting the attractions of Florida that much easier.

Indeed, Flagler was a brilliant salesman. He took out ads in northern publications, and planted news stories about the development of “America’s Riviera’’. And he bought or started newspapers in Florida to tout its wonders, as a vehicle for real estate and travel ads and so on. He was one of the early geniuses in mass marketing to America’s rapidly expanding consumer society, in which people learned about, and wanted, a far wider variety of products and services than ever before.

The growing sophistication in the late 19th Century of modern building construction materials, for example, steel-reinforced concrete, also greatly aided Flagler’s construction projects, especially his resort hotels up and down Florida’s East Coast. Indeed, his Ponce De Leon Hotel in St. Augustine is said to have been the first large poured-concrete building project.

He had learned at Standard Oil the benefits of using state-of-the art equipment and building materials. While the initial cost was higher than using mediocre stuff, the longer-term benefits for efficiency and marketing made his emphasis on quality the right choice.

As I keep noting, the State of Florida gave Flagler’s vast acreages of undeveloped land (8,000 acres per mile of track south of Daytona) in return for extending his railroad, and the development that followed. The state gave other Florida railroads lots of land, too, but Flager proved to be the most adept at using it. His company then made piles of money from marketing this land for resorts, year-round residential communities, agribusiness and other lucrative businesses. Without these land grants his empire would have been much, much smaller. By the way, it could be said that Florida was the first place in the world where building resorts and winter and retirement communities became major industries.

And, dating back to his experience in the grain and then oil business, Flagler was an expert in making secret deals. An example is his quiet purchase of land, using dummy companies, that he wanted to develop since the price would obviously go up a lot if owners knew someone as rich as Henry Flagler was interested in a tract. It reminds me of how Disney quietly bought up land for Walt Disney World, whose development and opening I covered back in the early ’70s. And Flagler was an expert in buying distressed enterprises – most notably northern Florida rail lines – at cheap prices and turning them around.

With the goal of transforming Florida’s east coast, Flagler would ride his own railroad in disguise in an effort to discover properties that could be developed into resorts and entire communities. The disguise obviously was to avoid tipping off landowners of his plan and thus drive up prices.

And the coming of oil-fueled locomotives, to replace coal, after the turn of the 20th Century, made train travel cleaner and more efficient in getting people to and fro the Flagler empire.

Electricity and the rapid adoption of indoor plumbing made staying in winter resort hotels much more alluring, and the faster trains from the 1880s on made it much faster to get there from, say New York. Flagler himself had a keen eye for the aesthetics of hotel and other buildings, inside and out, and of the high marketability of new creature comforts, including such recreational attractions as swimming pools, tennis courts and golf courses.

The Industrial Revolution was creating a class of rich folks who had the means to travel from (mostly) the Northeast and Upper Midwest to the resort hotels built and promoted by Henry Flagler and his Florida East Railway. Previously, most of them had mostly thought of going to luxurious SUMMER resorts relatively close to such wealth centers as New York, such as Newport.

But faster and more trains made it much easier than it had been to travel to Florida for its winter pleasures. The hotels promoted the Florida East Coast Railway and vice versa as Pullman sleeping cars, as well as dining cars, became more and more luxurious. And it became a status thing for your friends up north to know that you spent time in Flagler System hotels and perhaps later, with development of services and infrastructure spawned by the railroad, in your own capacious place in South Florida. Starting in the ‘20s, showing up back north with a tan became seen as a sign of status and wealth. (No one worried about skin cancer, sadly.)

And such increasingly popular sports associated with wealth as golf, tennis and yachting could, unlike in the North, be enjoyed in Florida in the winter – another promotional tool! Facilities for these sports were provided at the great resort hotels.

The Spanish-American War, in 1898, by bringing many troops from other parts of the country to Florida for the first time, further expanded national interest in the state.

Now to the labor situation during Flagler’s empire building – a situation that was generally very favorable to a mogul like Flagler. For one thing, unions were weak in America then, and in some places, including Florida, virtually nonexistent, and, anyway, state and local governments usually sided with owners/managers, and not with average workers.

Indeed, there were dark sides to Flagler’s empire building. Throughout the 1880s and 1890s, Flagler, like many industrialists, virtually all of whom were white, across the South, leased African American convict labor from the state. Convicts helped extend his Florida East Coast Railway (FECR) from West Palm Beach to Miami, cleared the land for his Royal Palm Hotel in Miami and graded the rail lines running from the mainland to his FECR extension across the Keys.

Industrialists like Flagler also used another system of forced labor that mostly targeted African Americans: debt peonage. A federal statute outlawed peonage, but in practice, it overlapped with convict labor. Convicts held beyond their sentences became debt peons, forced to labor to pay off debt owed to their lessor-turned-employer. Escaped peons were often arrested for vagrancy and leased out as convicts.

Convict lease laws in almost every Southern state provided a means for authorities to arrest freed people for such pseudo-crimes as vagrancy, lease them to private companies and force their labor.

Convict leasing generated revenue and provided a tool to intimidate and control black citizens. For businesses, the state offered vulnerable laborers who could be brutalized at whim, with chains, hounds, whips, sweat boxes, stringing up workers by the thumbs. Sanitary conditions were often terrible, and medical attention scant.

White immigrant workers, especially in the gigantic project to extend the Florida East Coast Railway to Key West, often also had it bad:

Flagler worked with Northern labor agencies to lure new immigrants to work on his railroad extension to Key West in often very dangerous conditions that included extreme heat and humidity and disease-carrying mosquitoes, not to mention hurricanes.

Workers were often refused passage off the Keys unless they worked off hefty transportation, boarding and commissary fees while men who had been promised positions as cooks, foremen or interpreters were compelled to work as laborers. Those who refused to work were sometimes denied food. Foremen often carried guns, and some sick laborers were beaten and threatened with death if they didn’t work.

Cheap labor indeed!

It’s hard to know how much Flagler knew of these conditions – obviously he knew something. In some ways, he was a kindly and charitable character.

Flagler’s empire building was also aided by the climate of political corruption of the Gilded Age. He had the money to bribe state and local politicians to make it easier for him to do his projects. (He even apparently bribed the Florida Legislature and Governor to pass a law in 2001 that made incurable insanity grounds for divorce so he could divorce his insane second wife in order to marry his third wife.)

First came the rich, but the Industrial Revolutions, mostly after the turn of the 20th Century, also created a middle class that, with careful saving, could afford to visit Florida. Few could afford to stay in Flagler’s grand hotels but could pay for the innumerable other accommodations (some built by Flagler) that sprang up to no small degree because of the creation of the Florida East Coast Railway. Many of these folks liked it so much they decided to move here. Sadly, many of them lost their shirts in the implosion of the Florida land boom in the late ‘20s but the population kept growing….

Of course, the coming of America’s automobile culture and associated construction of many more and better roads from the 1920s on, and especially the Interstate Highway System, took a big bite out of the Florida East Coast Railway, as did the use of big trailer trucks to carry Florida products.

At the same time, longer life expectancies, the expansion of the middle class, the introduction of Social Security payments and the decades in which corporate pensions (now disappearing except for upper management) were common helped drive a huge increase in people retiring in Florida. It’s hard to predict how long might continue.

In any event, it’s nice to know that Brightline passenger trains were running on the Florida East Coast Railway before the pandemic shut it down. It’s supposed to reopen in the fall.

This is good news for Florida. It needed a modern (for the time) rail system developed in the late 19th and early 20th Century because it was underdeveloped and poor. Now it needs one to reduce the choking car congestion that’s a result of the development jump-started by Henry M. Flagler.

Stop the ATV angst in Providence

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com.

It seems that Providence Mayor Jorge Elorza’s administration has been unwilling or unable, at least until recently, to strictly enforce laws against the use of ATV vehicles and dirt bikes on city streets, despite the very serious public-safety and quality-of-life issues such vehicles pose, especially given the arrogant, selfish and menacing irresponsibility of some of their riders. Indeed, the mayor has expressed an interest in legalizing their use on city streets, for those who would receive licenses and insurance for such use, although he has more recently back-tracked on that.

So, as a recent GoLocalProv.com article suggested, perhaps Rhode Island Gov. Dan McKee should send in the State Police to arrest these riders. ATV’s and dirt bikes don’t belong on city streets.

To read the editorial, please hit this link.

Life in a square picture

“Candy Jar” (mixed media), by Boston-based artist Helen Canetta, in her show “Kodachrome Chronicles,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, April 2-May 2

The gallery says:

“The purchase of an old-fashioned Polaroid camera for her daughter led painter Helen Canetta to create this collection of abstract ‘snapshots.’

“‘Watching my daughter focus on and capture the little wonders of everyday life in a meaningful square picture inspired me to rediscover the magic and emotions surrounding us in all its glorious simplicity.’

“This collection was created during 2020, a year filled with momentous and complex events and emotions. Finding the simplicity and the beauty in everything that ‘is’ was a healing force and a successful coping mechanism to get through the year. It also filled Canetta with a renewed appetite for simplicity, minimalism and hope.’’

David Warsh: Biden's policies, like Reagan's, are a big gamble, but based on experience

On Wall Street, with flag-draped New York Stock Exchange at right

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Might Democrats retain control of the White House through 2032? When I ventured that possibility the other day, my sagacious copy editor observed that one party had won three consecutive terms only once in the 70 years since Harry Truman left office on Jan. 20, 1953 – during the dozen years after Ronald Reagan was elected in 1980, reelected in 1984, and succeeded by Vice President George H. W. Bush in 1988.

I’ve been thinking ever since about why it might happen again. I know, I said I planned to write for a while mostly about economic topics, but what’s more economics than this?

It is not easy to recall how unlikely a Reagan’s victory seemed in the months running up to the 1980 election. True, he had served two terms as governor of California, but he had run unsuccessfully for president twice; he’d announced at the last minute in 1968 before running again, in 1976. His right-wing instincts were so little trusted by the Republican Party’s Establishment that Henry Kissinger sought to persuade him to accept former President Gerald Ford as his running mate. He was 69, an additional factor against him.

Similarly, Reagan’s policy initiatives – big tax cuts for the well-to-do, a willingness to tolerate the Federal Reserve Board’s high interest rates, deregulation for everyone, and an expensive confrontation with the Soviet Union – were thought to be dangerous and, at least by the Democrats, were expected to fail. Not much about America’s future was clear in 1980, except the widespread dissatisfaction with President Jimmy Carter. (Former Republican John Anderson was also on the 1980 ballot, as an independent; Reagan still would have won if he hadn’t been, but it wouldn’t have been the landslide it turned out to be.)

Then two years into Reagan’s first term, the economy took off, inflation fell, financial markets boom and China entered global markets. Over the course of the decade, the Cold War ended, and the government of the Soviet Union collapsed. Vice President Bush succeeded Reagan and fought a successful war in Iraq. Bush was defeated in 1992 because of a lack-luster economy, but the next 24 years – the presidencies of Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Barack Obama – were dominated, one way or another, by the “Washington Consensus” on economic policy that had formed during the Reagan years.

What similarities does Joe Biden share with Reagan? His candidacy was unexpected, for one thing; twice before Biden had run for president and failed to come close, in 1988 and 2008. At 78, Biden was even older than Reagan when elected. Most important, after nearly 50 years in the Senate, Biden is thoroughly wed to a movement, if that turns out to be what is unfolding, that has been in the making for as long or even longer than his service to it.

What movement? If Reagan’s gospel was that government was the problem, Biden’s credo seems to be that government spending is the solution to a variety of present-day problems – a fraying social safety net, deteriorating infrastructure, diminished U.S. competitiveness in global markets, and diminished opportunity. Gerald Seib, political columnist for the news pages of The Wall Street Journal, made a similar point to the one I’m making here the other day when he observed that not since Reagan’s presidency has a new administration opened with “a gamble as large as the one in which President Biden is now engaged” – an effort to change “not just the policies but the path of the country” with borrowed money.

Why might voters’ minds have changed in significant numbers about such fundamental matters as their enthusiasm for taxing and spending? Experience is one reason: Free markets and austerity failed to redress the problems they promised to solve. Indeed, they seem to have made them worse. Changing circumstances are others. Global warming has become manifest. A new kind of Cold War, this one with China, has emerged. And the Republican Party is deeply divided.

A shift of opinion on this scaled scale would, of necessity, entail a massive realignment of financial markets. As it happens, I have been reading The Day the Markets Roared: How a 1982 Forecast Sparked a Global Bull Market (Matt Holt Books, 2021), by Henry Kaufman. Kaufman was the authoritative Salomon Brothers economist whose forecast, on Aug. 18,1982, that interest rates would soon begin dropping ignited a stock market rally that hasn’t ended to this very day. Toward the end of his book, Kaufman mourns what he sees as a system of capitalism giving way to a system of “statism,” especially as the Treasury Department and the Federal Reserve System come under collaborative management in pursuit of White House goals. There is plenty more to be borrowed, he says — certainly enough to readjust in the future the currently skewed rates of return among stocks, bonds and commodities. Financial markets might yet sigh.

Saying how the battles of the next 10 years might play out would be a foolish venture. Forecasting who might be the Democratic and Republican Party nominees in 2024 and 2028 is considerably more pointless than guessing who will meet in the Super Bowl next year since there are far more variables involved. But there is nothing foolish about acknowledging the existence of tides of public opinion that ebb and flow. Reagan’s presidency was a “triumph of the imagination,” wrote former New York Times reporter Richard Reeves, in 2005. Might someone say the same of Biden in 2045?

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran.

Waterfront on woodcuts

“Sea Fox on an Evening Tide’’ (reduction woodcut), by Don Gorvett , in his show “Don Gorvett: Working Waterfronts," April 2 to Sept. 12, 2021, at the Portsmouth Historical Society's Academy Galleries, in Portsmouth, N.H. (This exhibit coincides the galleries show "Twilight of American Impressionism: Alice Ruggles Sohier and Frederick A. Bosley.")

Mr. Gorvett, born in Boston in 1949, is a contemporary artist and master printmaker. His immediate surroundings, the seaside, and its harbors are fundamental to his work. He’s influenced by a romantic passion for history, drama and music. He’s well known for his reduction woodcuts that record maritime subjects from Boston, Gloucester, Portsmouth and and Ogunquit, Maine.

His skills as a draftsman and understanding of printmaking are paramount features of his bold graphic style. By virtue of the reduction woodcut method, he arrives at a degree of abstract imagery and liberation from literal realism.

Don Pesci: And now Conn. considers a wealth-repelling 'mansion tax'

The Branford House, in Groton, Conn., on the Avery Point campus of the University of Connecticut, which rents it out for events. Branford House was built in 1902 for Morton Freeman Plant, a local financier and philanthropist, as his summer home; he named it after his hometown of Branford, Conn. The house is on the National Register of Historic Places.

VERNON, Conn.

”There will be time, there will be time

To prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet.’’

– T.S. Eliot

Connecticut is running out of time to prepare a face to meet the faces it will meet. “The whole world is watching,’’ as kids in the Sixties used to say when, caught in the grip of an unwanted war, TV cameras showed them sticking flowers in the barrels of National Guard rifles warding them off .

Clever politicians may hide behind their own designer masks, but the face that Connecticut presents to the world and other states cannot be hidden. The question that politicians in Connecticut should be asking, and acting upon, is this one: What is the face that Connecticut has been presenting during the last few decades to revenue producers? Is it attracting or repelling the entrepreneurial capital that the state desperately needs to finance both its operations and its best prompting from the angels of its better nature?

Consider a recent story in a Hartford paper titled “Lamont tells Connecticut businesses he opposed ‘mansion tax.’” The mansion tax is the latest sunburst from Martin Looney, the most progressive president pro tem of the state Senate in Connecticut history.

The Looney state property tax would be levied on the assets of millionaires in Connecticut. The mansion tax, we are told in the story, will “funnel more money to municipal governments.… It will raise $73 million a year as part of a package to provide property-tax relief for cash-strapped communities like his hometown of New Haven.-

The quickest and most efficient way of shuttling money from state coffers to municipalities is to reduce any tax and allow people in municipalities to retain their own assets. Doing so would avoid the trip that a dollar makes from the municipality to the state and back again – minus administrative costs – to the municipality. But this method would short circuit the progressive afflatus and considerably reduce the political influence of progressive redistributors. One imagines Looney gagging on such a solution as being too simple, workable and efficient.

The new mansion tax drew an immediate response from millionaire Gov. Ned Lamont: “I don’t support it. I don’t think it’s going anywhere, and I don’t think we need it,” Lamont told “Chris DiPentima, president of the Connecticut Business & Industry Association” on a webcast conference call.

Lamont, we are told, issued his comment “a day after a public hearing among state legislators who called for a separate 5 percent surtax on capital gains, dividends and taxable interest.” In addition, the progressive legislators want to increase the personal-income-tax rate for earners making more than $500,000 a year and couples earning more than $1 million annually.

In addition, progressive lawmakers – nearly half the Democrat caucus in the General Assembly are progressives – “support reducing the Connecticut estate tax exemption of $2 million and [eliminating] the current cap on payments that would yield higher” revenue payments from millionaires in the state who foolishly decide to remain on the spot, there to be cudgeled and deprived of their assets by tax greedy progressives.

This concerted attack on wealth accumulation in Connecticut is designed, consciously or not, to drive creative revenue production out of the state the way St. Patrick once drove serpents out of Ireland and, in the long run, the effort will succeed. Millionaire snakes will slither out of Connecticut on their way to enrich competing states.

Seen from outside the state, what does the face of Connecticut look like?

Well, it is among the highest taxed states in the nation; business flight is rampant; out-of-state companies have gobbled up Connecticut home-grown companies, such as, United Technologies, now merged with Raytheon Technologies, based in Waltham, Mass.; Sikorsky, now owned by Lockheed Martin, headquartered in Bethesda, Md.; Aetna Insurance Company, now a subsidiary of CVS Health, which is based in Woonsocket, R.I.; Colt firearms, bought by the Ceska Zbrojovka Group, a Czech company; and it seems likely that The Hartford, a company that once insured Abe Lincoln’s home in Illinois, will in the near future be bought by Chubb, incorporated in Zürich, Switzerland. This is not a fetching portrait of Connecticut's face, but it is an accurate one.

This is not a fetching portrait of Connecticut's face, but it is an accurate one.

When the Coronavirus high tide recedes, very quickly now, it will leave on the shore the wreckage of Connecticut’s economy that had been apparent to everyone before the Wuhan, China, virus arrived in our state. Connecticut, if it is to remain competitive with other states, must address a legion of problems that cannot be settled by politicians more interested in saving their seats than their state. The state’s spending spree, unchecked since 1991, must be addressed. Taxes are too high, and politicians much too clever and committed, body and soul, to unchecked spending, neither of which advances the public good.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

Myth about Nature

“We came like others to a country of farmers –

Puritans, Catholics, Scotch Irish, Quebecois:

bought a failed Yankee’s empty house and barn

from a prospering Yankee,

Jews following Yankee footprints,

prey to many myths but most of all

that Nature makes us free….”

From “Living Memory’’ by Adrienne Rich (1929-2012). She lived for time in the smalll western Massachusetts town of Montague.

Boston springs happily encourage forgetfulness

Along Boston’s Esplanade, on the Charles River, on a spring day

The spring in Boston is like being in love: bad days slip in among the good ones, and the whole world is at a standstill, then the sun shines, the tears dry up, and we forget that yesterday was stormy.”

– Louise Closser Hale (1872 -1933), an American actress, playwright, and novelist. She attended the Boston School of Oratory.

'Wetness and solidity'

“Sun with Rain” (oil on linen), by Boston-based painter Bryan McFarlane, in his show “Caught in Colorful Rain,’’ at Gallery NAGA, Boston, through March 27

The gallery says these paintings were created from memories of Mr. Farlane’s Jamaican childhood, and especially memories of the weather. His paintings include bands of paint dripping down the canvas, resembling raindrops falling. Some of his works portray such bodies as waterfalls or rivers, in which he uses thicker bands of paint and deeper, darker colors to suggest the churning depths. So his paintings are a study in opposing forces — “dark and light, warmth and coolness, wetness and solidity, all come together in the paintings just as they do in the rain that falls or the ocean waves that crash. Alongside this duality is the hope that humanity will be able to live in balance with these natural forces and continue to enjoy the rain.’’

Llewellyn King: ‘Long COVID’s’ baffling sister

CFS vitim demonstrates for more research

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

“Long COVID’’ is the condition wherein people continue to experience symptoms for longer than usual after initially contracting COVID-19. Those symptoms are similar to the ones of another long-haul disease, Myalgic Encephalomyelitis, often called Chronic Fatigue Syndrome.

For a decade, in broadcasts and newspaper columns, I have been detailing the agony of those who suffer from ME/CFS. My word hopper isn’t filled with enough words to describe the abiding awfulness of this disease.

There are many sufferers, but how ME/CFS is contracted isn’t well understood. Over the years, research has been patchy. However, investigation at the National Institutes of Health has picked up and the disease now has measurable funding -- and it is taken seriously in a way it never was earlier. In fact, it has been identified since 1955, when the Royal Free Hospital, in London, had a major outbreak. The disease had certainly been around much longer.

In the mid-1980’s, there were two big cluster outbreaks in the United States -- one at Incline Village, on Lake Tahoe in Nevada, and the other in Lyndonville in northern New York. These led the Centers for Disease Control to name the disease “Chronic Fatigue Syndrome.”

The difficulty with ME/CFS is there are no biological markers. You can’t pop round to your local doctor and leave some blood and urine and, bingo! Bodily fluids yield no clues. That is why Harvard Medical School researcher Michael VanElzakker says the answer must lie in tissue.

ME/CFS patients suffer from exercise, noise and light intolerance, unrefreshing sleep, aching joints, brain fog and a variety of other awful symptoms. Many are bedridden for days, weeks, months and years.

In California, I visited a young man who had to leave college and was bedridden at his parents’ home. He couldn’t bear to be touched and communicated through sensors attached to his fingers.

In Maryland, I visited a teenage girl at her parents’ home. She had to wear sunglasses indoors and had to be propped up in a wheelchair during the brief time she could get out of bed each day.

In Rhode Island, I visited a young woman, who had a thriving career and social life in Texas, but now keeps company with her dogs at her parents’ home because she isn’t well enough to go out.

A friend in New York City weighs whether to go out to dinner (pre-pandemic) knowing that the exertion may cost her two days in bed.

I know a young man in Atlanta who can work, but he must take a cocktail of 20 pills to deal with his day.

Some ME/CFS sufferers get somewhat better. The instances of cure are few; of suicide, many.

Onset is often after exercise, and the first indications can be flu-like. Gradually, the horror of permanent, painful, lonely separation from the rest of the world dawns. Those without money or family support are in the most perilous condition.

Private groups -- among them the Open Medicine Foundation, the Solve ME/CFS Initiative, and ME Action -- have worked tirelessly to raise money and stimulate research. The debt owned them for their caring is immense. This has allowed dedicated researchers from Boston to Miami and from Los Angeles to Ontario to stay on the job when the government has been missing. Compared to other diseases, research on ME/CFS has been hugely underfunded.

Oved Amitay, chief executive officer of the Solve ME/CFS Initiative, says Long COVID gives researchers an opportunity to track the condition from onset and, importantly, to study its impact on the immune system – known to be compromised in ME/CFS. He is excited.

In December, Congress provided $1.5 billion in funding over four years for the NIH to support research into Long COVID. The ME/CFS research community is glad and somewhat anxious. I’m glad that there will be more money for research, which will spill into ME/CFS, and worried that years of endeavor, hard lessons learned and slow but hopeful progress will be washed away in a political roadshow full of flash.

Ever since I began following ME/CFS, people have stressed to me that more money is essential. But so are talented individuals and ideas.

Long COVID needs carefully thought-out proposals. If it is, in fact, a form of ME/CFS, it is a long sentence for innocent victims. I have received many emails from ME/CFS patients who pray nightly not to wake up in the morning. The disease is that awful.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

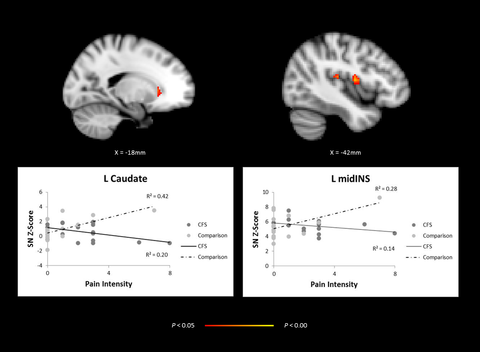

Brain imagining, comparing adolescents with CFS and healthy controls showing abnormal network activity in regions of the brain

Ah, March!

“March brings many things, but not hurricanes. But yesterday it brought a storm and a temperature drop, a farewell gesture from winter. The pipes froze again in the back part of the house. And as I viewed the solidly frozen bath mat in my shower, I felt I could do without any record-breaking statistics.’’

— Gladys Taber (1899-1980), in The Stillmeadow Road (1959). A prolific writer, she lived for 20 years in a 1690 farmhouse in Southbury, Conn., whence she wrote her “Stillmeadow series’’ about New England country living. Southbury now is more exurbia than country.

Southbury town seal

Dana Farber and MIT joining in new cancer initiative

Part of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

“Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, in Boston, and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), in Cambridge, have partnered along with three other organizations — Johns Hopkins University, in Baltimore, Memorial Sloan Kettering, in New York City, and MD Anderson, in Houston — in a pledge to treat the most challenging forms of cancer. Break Through Cancer, a new foundation backed by a $250 million donation from Mr. and Mrs. William H. Goodwin Jr. and the estate of the late William Hunter Goodwin III, who passed away in 2020 from cancer, will fund and support collaboration among the nation’s top cancer institutions.

“President Biden has expressed his support for the foundation, stating, ‘I’m delighted to see five of the nation’s leading cancer centers are joining forces today to build on the work of the Cancer Moonshot I was able to do during the Obama-Biden administration to help break through silos and barriers in cancer research.’ Break Through Cancer also focuses heavily on particularly challenging cancers, including pancreatic cancer, ovarian cancer, acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) and glioblastoma. Cancer experts and teams will receive substantial funding to develop innovative treatments, clinical trials, and cures.

“‘We realize there are no guarantees, yet we believe this effort to fight cancer, particularly with collaborative research, has a realistic probability of success,’ said Bill Goodwin. ‘We want to help people have better lives. And we sincerely hope that by being public with our support, we will inspire others to support this incredible effort.”’

Philip K. Howard: Reboot America to reempower citizens

Georgia Sen. Raphael Warnock

Oklahoma City Mayor David Holt

The most compelling political statements today are those that focus on mutual respect and factual truth — such as this statement by Republican Mayor David Holt of Oklahoma City, just two days before the mob attacked the Capitol on Jan. 6, or the victory statement by Georgia Democrat Raphael Warnock after he won a U.S. Senate seat

But why does such a large group of Americans feel so alienated that they abandon basic civilized values? One of the main reasons, I think, is a sense of powerlessness. They're stretched thin, due to economic forces beyond their control. They don't think their views matter, or that they can make a difference in, say, their schools or communities. They can't even be themselves. Spontaneity, which philosopher Hannah Arendt considered "the most elementary manifestation of human freedom," is fraught with legal peril: "Can I prove what I'm about to say or do is legally correct?"

The cure requires reviving human responsibility at all levels of authority. People need to feel free to roll up their sleeves and get things done. They need to feel free to be themselves in daily interactions, accountable for their overall character and competence. A functioning democracy requires officials to take responsibility for results, not mindless compliance. In an essay published in January by the Yale Law Journal, "From Progressivism to Paralysis’’, I describe how good government slowly evolved into a framework that disempowers everyone, even the President, from acting sensibly.

Problems with the rollout of COVID-19 vaccines is only the latest manifestation of a micro-management governing philosophy that suffocates leadership as well as disempowering citizens.

It's time to reboot the system, not to deregulate but re-regulate in a way that revives the American can-do spirit at all levels of society. This requires a new movement. If you agree, please contact phoward@commongood.org.

Philip K. Howard is chairman of Common Good (commongood.org), the legal- and regulatory-reform organization. He’s based in New York and is a lawyer, civic and cultural leader, photographer and author. His books include The Death of Common Sense, Try Common Sense , The Rule of Nobody and Life Without Lawyers.

Keep your virus off our island!

On Matinicus, 20 miles off Maine’s mainland

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The reaction of residents of islands off the New England coast, from big ones, such as Nantucket, to tiny Matinicus, off Maine, to the pandemic has, in a way, been paradoxical. These folks (more than a few of whom tend to be recluses) sometimes feel safer because they are separated by water from the worst COVID case densities, on the mainland, while fearful that a few cases will make their way onto their islands and explode.

There have been some ugly scenes, such as locals stretching chains across driveways of summer people “From Away’’ trying to shelter in place from COVID there and nasty notes.

xxx

Of course, New England’s islands are a big lure in the summer. I wonder how the vaccination surge will affect how many tourists and vacation-home residents visit them this summer as they play travel catch-up.

But still sort of alive

“Six Feet Under” (archival inkjet print), by Douglas Breault ,in his show “Sleepwalking’’ at the Rochester (N.H.) Museum of Art through April 2.

The gallery says the New Bedford-based artist’s still-life photographs “represent memories of his late father through objects he used to own, but also by utilizing elements like camera obscura projections, printed archival images and shadows to reflect the passage of time. He also incorporates images taken from the Internet, further building each piece's connection with narrative and memory. Mr. Breault's process results in artworks that drip with materiality and exude an undeniable physical presence.‘‘

The Cocheco River flows through central Rochester. The river once provided power for mills.

— Photo by AlexiusHoratius

Country and city

Postcard circa 1905

“I have lived more than half my life in the Connecticut countryside, all the time expecting to get some play or book finished so I can spend more time in the city, where everything is happening.’’

Arthur Miller, playwright (1915-2005), playwright, including Death of a Salesman, All My Sons and The Crucible. He was a longtime resident of Roxbury, Conn. The town has attracted a number of famous people as residents, including actors Dustin Hoffman and Richard Widmark, novelist William Styron and artist Alexander Calder. Roxbury is no longer in the country, but rather part of Greater New York City exurbia.

Roxbury, in the southern Litchfield Hills, in a modest way used to be a mining town. A silver mine was opened here and was later found to contain spathic iron, very useful in steel making, and a small smelting furnace was built. The granite found in many of Roxbury’s Mine Hill quarries provided building material for such world wonders as the Brooklyn Bridge and Grand Central Terminal, in New York City.