Chris Powell: Another golden age coming for 'earmarks'

Huey P. Long (1893-1935), Louisiana governor and U.S. senator and famed demagogue. He died in an assassination. He would have liked “earmarks”.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Congratulations to one of Connecticut's forever members of Congress, U.S. Rep. Rosa DeLauro, Democrat of New Haven, for teaching the country a wonderful political-science lesson.

Having ascended to the chairmanship of the House Appropriations Committee, DeLauro has just revived the infamous practice of putting "earmarks" in the federal budget -- requirements that funds that ordinarily would be appropriated for general purposes be reserved for patronage projects desired by congressmen. Now DeLauro is forwarding her chief of staff, Leticia Mederos, to a national law and government relations firm, Clark Hill, whose office on Pennsylvania Avenue is within walking distance of the Capitol and the White House. Mederos will become a lobbyist, and her close connection to the House appropriations chairwoman will be a swell advantage to her clients.

This stuff is sometimes euphemized as public service. Where candor is permitted, it is called influence- peddling or even plunder.

The political-science lesson taught here by DeLauro and her outgoing chief of staff is like the one taught by Huey Long when he was governor of Louisiana in the 1930s. Gathering his closest supporters just after his election, Long is said to have told them:

“You guys who supported me before the primary will get commissionerships. You guys who supported me after the primary and before the election will get no-show jobs. You guys who donated at least $10,000 to my campaign will get road contracts. Everybody else will get goood gummint.”

Thanks to DeLauro and the rest of the new Democratic administration in Washington, $1.9 trillion in “goood gummint ‘‘ is on its way to the country in the name of virus epidemic relief.

DeLauro estimates that more than $4 billion of that money will be given to state and municipal government in Connecticut for purposes leaving wide discretion in its allocation. That $4 billion is equivalent to almost 20 percent of state government's annual spending and is $2 billion more than what state government estimates it has spent responding to the epidemic. That extra $2 billion will be a grand slush fund.

Gov. Ned Lamont and the General Assembly will decide just where to spend the money, and spending it carefully will be a huge challenge that is not likely to be met well.

Of course, much of the federal largesse will be spent in the name of education, but how exactly, and more importantly, why? After all, Connecticut has been increasing education spending for more than 40 years without improving student performance, just school-staff compensation. Even now half the state's high school graduates never master high school math or English and many take remedial high-school courses in public "colleges."

So the most promising educational use of the federal money might be to finance remedial summer school for Connecticut's many under-performing students over the next several years, since so many have missed most of their schooling during the last 12 months and were already far behind in education when the epidemic began. Using the education money for remedial summer school would minimize the problem school administrators fear. That is, if the emergency federal money is incorporated in recurring school operations, it will leave a disruptive gap when it runs out in a year or two.

xxx

As "earmarks" return to Congress, Connecticut's bonanza from Washington is sure to induce more earmark fever at the state Capitol, where it long has infected bonding legislation. Already Hartford Mayor Luke Bronin imagines spending billions for high-speed railroad service from the city to New York and Boston and development of the city's riverfront, as if the lack of those things is Hartford's big problem. At least the mayor is no longer boasting about defunding the city's police. In the 48-hour period that included his "State of the City" address this week, six people were shot in separate incidents in the city, one fatally. Maybe Hartford's most pressing need is for more police officers.

But if the governor can persuade the Democratic majority in the General Assembly not to spend the federal money too fast, enough will remain in the slush fund to get them past the 2022 state election without raising taxes, if also without making state government any more efficient and effective.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Big new industry

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

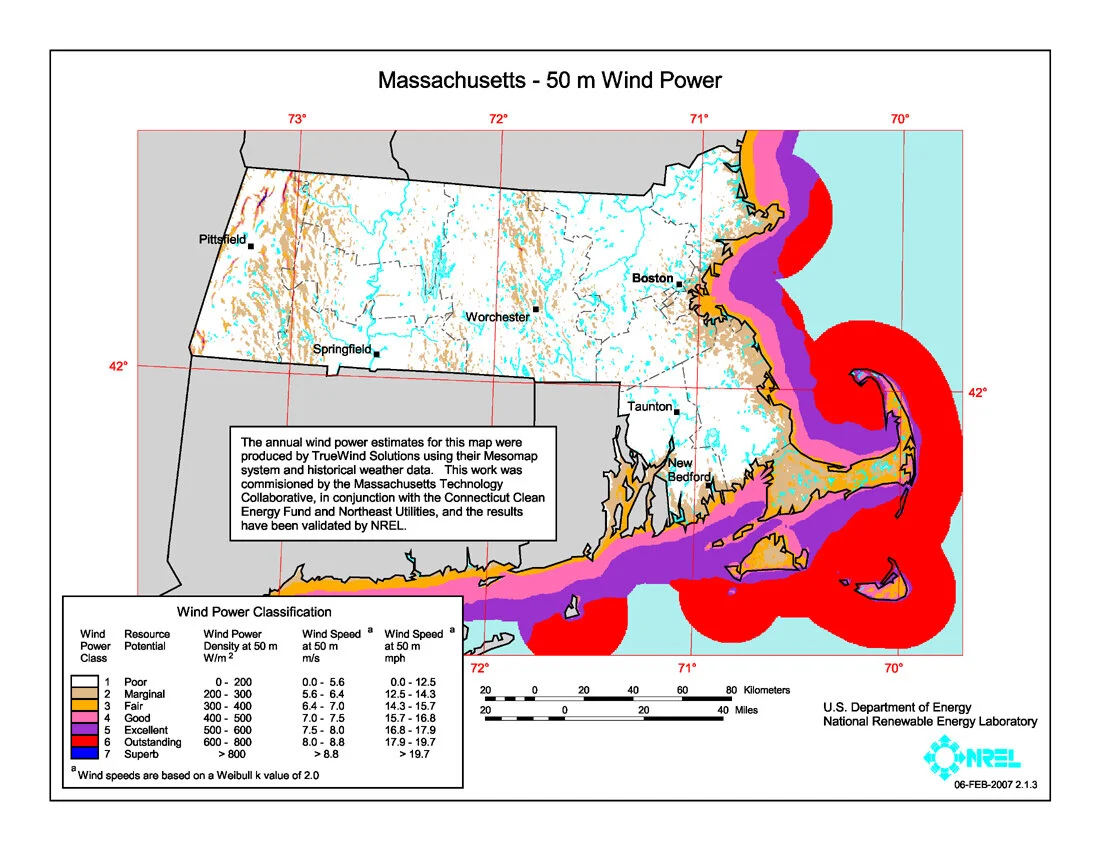

It looks as if the huge Vineyard Wind project will start operating about 15 miles south of Martha’s Vineyard by late 2023, now that the Biden administration is close to giving it the final thumbs up, though there still could be last-minute hitches. (The Trump regime much preferred power plants powered by fossil fuel and seemed to oppose the project.) All such big projects swim in politically tinged controversies and tangles of interest groups.

The wind farm would include 62 giant Boston-based General Electric turbines in the project’s first, 400-megawatt phase. The full project, at 800 megawatts, would be enough to provide the electricity for a total of 400,000 residential and business customers in Massachusetts. The turbines would be spaced more than a mile apart.

This project would mean much more local, and thus more secure, clean energy for New England, boosting its economy and health indices. There would be considerable economic development associated with building and maintaining this $2.8 billion project with, of course, southeastern New England reaping a lot of those benefits. Several thousand well-paying jobs, of varying periods, would be created.

Some have called offshore New England “the Saudi Arabia of wind.’’

Vineyard Wind has tried to address the issues raised by fishermen by putting more distance between the turbines than earlier proposed and deciding to use the GE turbines instead of the originally planned Vestas ones. The more powerful GE turbines mean that fewer would be needed to meet generation goals.

Fishing and big offshore wind farms seem to co-exist well in Europe, though there are bound to be disruptions, especially during construction. Vineyard Wind will attract fish once that’s over: The below-water parts of turbine towers act, as do reefs and shipwrecks, as habitats for the creatures.

Then there’s the bird issue. Some birds crash into turbine blades, as they do into buildings, cars, power-line towers and so forth. (Ban skyscrapers?) But the newer, bigger turbines, such as GE’s, are more widely spaced and spin more slowly than earlier ones, making them less perilous to birds and bats. And it seems that such measures as painting one of a turbine’s blades black help steer birds away, as does broadcasting certain sounds and using certain lights. The industry is still learning how to minimize impacts on wildlife.

Of course, burning fossil fuels pose far wider risks to birds and other wildlife via global warming, ocean acidification, pollution, oil spills, etc., than do wind turbines.

Problems will arise but, all in all, Vineyard Wind and other such projects would be a boon for our region.

Are we ready for such a major new local industry? Vineyard Wind would be the first such big wind farm off southern New England. But others will probably follow. Officials of another mega-project, Mayflower Wind, for example, for south of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket, hope to start generating electricity in 2025. (The up-and-running Block Island Wind Farm is tiny, with only five turbines, producing a total of 30 megawatts.)

For the foreseeable future, wind and solar power will remain the major non-fossil-fuel energy sources. But hydrogen in fuel cells could become a big deal, too. Meanwhile, of course, we’ll still have to depend on fossil fuels for much of our energy for the next couple of decades.

A bit of an irony: New Bedford would play a major role in the construction and maintenance of Vineyard Wind and other offshore wind projects. For decades in the 19th Century, the city was also an energy center, as the biggest port for bringing in whale oil, which was used for lighting. Getting it caused horrific losses of these marine mammals.

Some people would hate the look of these big wind farms; others would see them as (eerily?) beautiful. In any case, we’ll get used to them.

Barely surviving the MIT miasma

Harvard Square offices of "Dewey, Cheetham and Howe", headquarters of Car Talk

— Photo by Patricia Drury

“Boy, I hated MIT. I worked my butt off for four long years. The only thing that saved my sanity was the 5:15 Club, named, I guess, for the guys who didn’t live on campus and took the 5:15 train back home. Yeah, right, 5:15, my tush! I never got home before midnight!

— Tom Magliozzi (1937-2014), co-host, with his brother and fellow mechanic Ray (born 1949), of the long-running (1987-2012) NPR series Car Talk. Some NPR stations continue to broadcast reruns of some episodes. The brothers grew up in East Cambridge, very close to MIT, from which they both graduated.

Tom Magliozzi

The glamour of gray

Chatham {Mass.} Mood (archival pigment print, by Bobby Baker.

© Bobby Baker Fine Art

She's on the grid

”Fulfilled” (mixed media), by Shelley Loheed, in her show “Getting Answers:

/order_behind,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, April 20-May 2.

The Massachusetts artist says:

"The painting and drawing in this series investigate geometric designs derived from traditional patterns. Grids are the substructure of geometric art.

“I have been working with these patterns for some time. Narrowing my focus in this body of work to just the underlying grid.

“The grid becomes the center from which the image emerges out of creating the drawing's subtle underpinning, which gets revealed and obscured by fluid gestural improvisations. The series combines two modes of working. The grid's underlying order and the spontaneous layers of washes, splashes, and strong brushwork allow for the chance interplay of wet media and drawing.

“The subgrids are rarely shown in traditional art. They are considered part of the underlying structure of reality, the substrate of the cosmos. The paintings and drawings capture an image of a fraction of a second caught in an imaginary universe."

MassMutual seeks to boost economy in poorer parts of state

The MassMutual Tower in Springfield

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

“Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Co. (MassMutual) (founded in 1851) recently launched the MM Catalyst Fund to invest $50 million in local businesses, targeting economic growth in underdeveloped areas of Massachusetts.

“The fund will be distributed evenly between two categories of capital: one half in community growth (“MMCF Growth”) through equity and debt investments in Black-owned businesses, and the other half in technology (“MMCF Tech”) through equity investments in technology companies based outside of Boston.

‘Rilwan Meeran, Impact Investment Portfolio Manager who oversees the MMCF commented, “Impact investing at MassMutual seeks to create a positive social and environmental impact that is measurable while also making market rate financial returns. Philanthropy alone cannot solve our society’s problems; institutional capital investment should also play a role.”

By the pre-Storrow Drive sepia stream

On the Boston side of the Charles River, in 1915, pre-Storrow Drive. Storrow Drive was built in 1950-1951. The parkway is named for James J. Storrow (1864-1926), an investment banker who led a campaign to create the Charles River Basin and preserve and improve the riverbanks as public parks. He had never advocated a parkway beside the river, and his widow strenuously opposed it

'Grave green dust'

“For two weeks or more the trees hesitated;

the little leaves waited,

carefully indicating their characteristics.

Finally a grave green dust

settled over your big and aimless hills.’’

— From “A Cold Spring,’’ by Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979), off and on a New Englander

'Highest treason'

Looking toward Barnstable Harbor

— Photo by ToddC4176

“The highest treason in the USA is to say Americans are not loved, no matter where they are, no matter what they are doing there.’’

Kurt Vonnegut (1922-2007), American writer, probably best known for the novel Slaughterhouse-Five. He lived in 1951-1971 with his family in a house in the village of West Barnstable, part of the Town of Barnstable, that overlooked Barnstable Harbor. Some members of the family still live in the town.

Kurt Vonnegut in 1971, at the height of his fame

David Warsh: Economic models and engineering

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The best book about developments in the culture of professional economics to appear in the last quarter century is, in my opinion, The World in the Model: How Economists Work and Think (Cambridge, 2012), by Mary S. Morgan, of the London School of Economics and the University of Amsterdam. The best book of the quarter century before that is, again, according to me, An Engine, Not a Camera: How Models Shape Financial Markets (MIT, 1997), by Donald MacKenzie, of the University of Edinburgh.

Both books describe the introduction of mathematical models in the years beginning before World War II. Both consider how the subsequent use of those techniques has changed how economics is done by economists. Morgan’s book is about the kinds of models that economists devise experimentally, not those that interest MacKenzie most, models designed to be tested against the real world. A deft cover illustrates Morgan’s preoccupation, showing the interior of a closed room with only a high window. On the floor of the room are written graphic diagram of supply and demand. The window opens only to the sky outside, above the world itself, a world the model-builder cannot see. The introduction of statistical inference to economics she dealt with in The History of Econometric Ideas (Cambridge, 1990).

I remember the surprise I felt when I first read Morgan’s entry “Economics” in The Cambridge History of Science Volume 7: The Modern Social Sciences (Cambridge, 2003). She described two familiar wings of economics, often characterized in the 19th Century as “the science of political economy” and “the art of economic governance.” Gradually in that century they were relabeled “positive” economics (the way it is, given human nature) and “normative” economics (the way it ought to be).

Having practiced economics in strictly literary fashion during the modern subject’s first century, Morgan continued, economists in the second half of the 19th Century began adopting differential calculus as a language to describe their reasoning. In the 20th Century, particularly its second half, the two wings have been firmly “joined together” by their shared use of “a set of technologies,” consisting mainly of mathematics, statistics and models. Western technocratic economics, she wrote, had thereby become “an engineering science.”

I doubted at the time that it was especially helpful to think economics that way.

Having read Economics and Engineering: Institutions, Practices, and Cultures (2021, Duke), I still doubt it. That annual conference volume of the journal History of Political Economy appeared earlier this year, containing 10 essays by historians of thought, with a forward by engineering professor David Blockley, of the University of Bristol, and an afterword by Morgan herself. Three developments – the objectification of the economy as a system; the emergence of tools, technologies and expertise; and a sense of the profession’s public responsibility – had created something that might be understood as “an engineering approach” to the economy and in economics, writes Morgan. She goes on to distinguish between two modes of economic engineering, start-fresh design and fix-it-up problem-solving, noting that enthusiasm for the design or redesign of whole economies and/or vast sectors of them had diminished in the past thirty years.

It’s not that the 10 essays don’t make a strong case for Morgan’s insights about various borrowings from engineering that have occurred over the years: in particular, Judy Klein, of Mary Baldwin University, on control theory and engineering; Aurélien Saïdi, of the University of Paris Nanterre, and Beatrice Cherrier, of the University of Cergy Pontoise and the Ecole Polytechnique, on the tendencies of Stanford University to produce engineers; and William Thomas, of the American Institute of Physics, on the genesis at RAND Corp. of Kenneth Arrow’s views of the economic significance of information.

My doubts have to do with whether the “science” of economics and the practice of its application to social policy have indeed been in fact been “firmly joined” together by the fact that both wings now share a common language. I wonder whether more than a relatively small portion of what we consider to be the domain of economic science is sufficiently well understood and agreed-upon by economists themselves as to permit “engineering” applications.

Take physics. In the four hundred years since Newton many departments of engineering have been spawned: mechanical, civil, electrical, aeronautical, nuclear, geo-thermal. But has physics thereby become an engineering science? Did the emergence of chemical engineering in the 1920s change our sense of what constitutes chemistry? Is biology less a science for the explosion of biotech applications that has taken place since the structure of the DNA molecule was identified in 1953? Probably not.

Some provinces of economics can be considered to have reached the degree of durable consensus that permits experts to undertake engineering applications. I count a dozen Nobel prizes as having been shared for work that can be legitimately described as economic engineering: Harry Markowitz, Merton Miller and William Sharpe, in 1990, for “pioneering work in financial economics”; Robert Merton and Myron Scholes, in 1997, “for a new method to determine the value of derivatives”; Lloyd Shapley and Alvin Roth, in 2012, “for the theory of stable allocations and the practice of market design”: Abajit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer, in 2019, for “their experimental approach to alleviating global poverty”; and Paul Milgrom and Robert Wilson, in 2020, for “improvements to auction theory and inventions of new auction formats.”

This is where sociologist Donald McKenzie comes in. In An Engine Not a Camera, he describes the steps by which, in the course of embracing the techniques of mathematical modeling, finance theory had become “an active force transforming its environment, not a camera, passively recording it,” but an engine, remaking it. When market traders themselves adopted models from the literature, the new theories brought into existence the very transactions of which abstract theory had spoken – and then elaborated them. Markets for derivatives grew exponentially. Such was the “performativity” of the new understanding of finance. After all, writes Morgan in her afterword, hasn’t remaking the world been the goal of economic-engineering interventions all along?

Natural language has a knack for finding its way in these matters. We speak easily of “financial engineering” and “genetic engineering.” But “fine-tuning,” the ambition of macro-economists in the 1960s, is a dimly remembered joke. The 1942 photograph on the cover of Economics and Engineering – graduate students watching while a professor manipulates a powerful instrument laden with gauges and controls – seems like a nightmare version of the film Wizard of Oz.

John Maynard Keynes memorably longed for the day when economists would manage to get themselves thought of as “humble, competent people on a level with dentists.” Nobel laureate Duflo a few years ago compared economic fieldwork to the plumbers’ trade. “The scientist provides the general framework that guides the design…. The engineer takes these general principles into account, but applies them to a specific situation…. The plumber goes one step further than the engineer: she installs the machine in the real world, carefully watches what happens, and then tinkers as needed.”

The $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan Act that became law last week, with its myriad social programs, is not founded on what “the science” says. It is an intuition, an act of faith. Better to continue to refer to most economic programs as “strategies” and “policies” instead of “engineering,” and consider effective implementations to be artful work.

David Warsh, an economic historian and a veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first appeared

Copyright 2021 by David Warsh, proprietor

And waiting for you to leave

“Mighty Aphrodite” (mixed media), by Brookline, Mass., artist Martin R. Anderson, now at Bromfield Gallery, Boston

With a population of about 59,00, Brookline is the most populous municipality in Massachusetts to have a town (rather than city) form of government.

Niche, the ranking and review Web site, placed Brookline as the best place to live in Massachusetts and the 10th best in America.

Brookline was first settled in 1638 as a hamlet of Boston; it was incorporated as a separate town in 1705.

Blandly telling time

Tall-case striking clock made in Boston by Benjamin Bagnall Sr. between 1730 and 1745

— Photo by Daderot

“Back and forth, back and forth

goes the tock, tock, tock

of the orange, bland ambassadorial

face of the moon

on the grandfather clock.’’

— “Fall 1961,’’ by Robert Lowell (1917-1977), among New England’s most famous poets since Robert Frost.

And then back to a friend?

— Photo by Mstrsail

“What good is a friend if you can’t make an enemy of him?’’

— William Hooker Gillette (1853-1937) an innovative and once famous American actor-manager, playwright, and stage-manager, in the late best remembered for portraying Sherlock Holmes.

He is best known now for the bizarre and ingenious Gillette Castle in Lyme, Conn., part of Gillette Castle State Park, which straddles the towns of East Haddam and Lyme. The castle sits high above the Connecticut River. The castle was originally a private residence commissioned and designed by Gillette. It has many strange features and is well worth a visit.

Paul Armentano: Does it matter if pot is stronger these days?

Flowering cannabis (marijuana) plant

Via OtherWords.org

I’ve worked in marijuana policy reform for nearly 30 years. Throughout my career, opponents of legalization have alleged that “today’s” pot is far more potent — and therefore more dangerous — than the cannabis of prior generations.

For instance, former Drug Czar William Bennett claimed in 1990 that if people from the late 1960s “suck on one of today’s marijuana cigarettes, they’d fall down backwards.”

His successor, Lee Brown, claimed in 1995 that “marijuana is 40 times more potent today” than it was decades ago. Not to be outdone, then-Delaware Sen. Joe Biden opined in 1996: “It’s like comparing buckshot in a shotgun shell to a laser-guided missile.”

Taking their hyperbole at face value, the message is clear: Modern marijuana is exponentially stronger and more harmful than the weak, nearly impotent weed of yesteryear.

But that’s not what the drug warriors of yesteryear warned.

During the 1930s, Henry Anslinger, Commissioner of the Bureau of Narcotics, testified to Congress that cannabis is ”entirely the monster Hyde, the harmful effect of which cannot be measured.”

Decades later, in the 1960s and ‘70s, public officials argued that the pot of their era was even stronger. They claimed that smoking “Woodstock weed” would permanently damage brain cells — and that, therefore, possession needed to be heavily criminalized to protect public health.

By the late 1980s, former Los Angeles Police Chief Daryl F. Gates opined that advanced growing techniques had increased THC potency to the point that “those who blast some pot on a casual basis… should be taken out and shot.”

Now a new generation of prohibitionists are recycling the same old claims and scare tactics in a misguided effort to re-criminalize more potent cannabis products in states where their production and sale is legal.

Most recently, these calls have even come from the Senate, including from Senators Diane Feinstein (D-Calif.) and John Cornyn (R-Texas).

So, is there any truth to the claim that today’s weed is so much stronger?

According to marijuana potency data compiled annually by the University of Mississippi at Oxford since the 1970s, one thing is true: The average amount of THC in domestically produced marijuana has increased over time.

But does this elevated potency equate to an increased safety risk? Not necessarily.

Higher-potency cannabis products, such as hashish, have always existed. Marijuana is still the same plant it has always been — with most of the increase in strength akin to the difference between beer and wine, or between a cup of tea and an espresso.

Consuming too much THC at one time can be temporarily unpleasant. But studies have as of yet failed to identify any independent relationship between cannabis use and mental, physical, or psychiatric illnesses.

Furthermore, THC — regardless of potency or quantity — cannot cause death by lethal overdose. Alcohol, by contrast, is routinely sold in lethal dose quantities. Drinking a handle of vodka could easily kill a person, yet vodka is available in liquor stores throughout the country.

Just as alcohol is available in a variety of potencies, from light beer to hard liquor, so is cannabis. So most users regulate their intake accordingly.

Also like with alcohol, cannabis products of the highest potency comprise a far smaller share of the legal marketplace than do more moderately potent products, like flower. According to data published last year in the journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence, nearly eight in ten cannabis consumers prefer herbal cannabis over higher-potency infused concentrates.

Virtually no one thinks alcohol over a certain potency should be re-criminalized. The same should be true of cannabis.

Instead, we should simply make sure consumers know how much THC is in the products they consume and what the effects may be. And we need more diligence from regulators to ensure that legal products for adults don’t get diverted to the youth market.

In other words, let’s address public health concerns with facts, not hyperbole.

Paul Armentano is the deputy director of NORML, the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws. He’s the co-author, with Steve Fox and Mason Tvert, of Marijuana Is Safer: So Why Are We Driving People to Drink?

Anti-marijuana ad from 1935

To tide us over to May

“Vintage Bouquet (Blue Hydrangeas)’’ (mixed media on canvas), by Emily Filler, at Lanoue Gallery, Boston

Wood chips: Green energy?

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

"I should like to have that written over the portals of every church, every school, and every courthouse, and, may I say, of every legislative body in the United States. I should like to have every court begin, 'I beseech ye … think that we may be mistaken.'"

“In the beginning and at the ending let us be content with the Guess’’

- U.S. Appeals Court Judge Learned Hand (1872-1961), legendary federal appeals court judge and philosopher of the law.

I haven’t liked a plan to build a electricity-generating plant in Springfield, Mass., that would burn wood chips. I have feared that it would lead to cutting down a lot of trees, which absorb carbon dioxide. Maybe I was wrong.

The Palmer Renewable Energy Co., which would build the plant, has fired back at its critics. It says that the wood wouldn’t come from cutting down a lot of trees but from the limbs trimmed to protect the power lines, much of which in New England are run through woodlands to avoid residential and commercial areas. But would that provide enough fuel for the plant?

The company notes that the linemen grind these limbs into wood chips that they spray into the woods, where they decompose, releasing the greenhouse-gas methane. The company asserts that methane is “25 times more destructive to our atmosphere than carbon dioxide.’’

Anyway, burning wood chips would be more environmentally sound than generating electricity with fossil fuels, which, unlike wood, has to be bought from outside New England.

I’m sure that the debate over the plant will grind on for a while but the company makes a plausible argument.

'Go home! People are dying!'

“Orthodox Jewish wedding party broken up by NYPD, Lower East Side, NYC, April 20, 2020, 10:30 p.m., 2020” (ink and watercolor on paper), by Steve Mumford, in his show through May 14 at the Hampden Gallery at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

The gallery says:

“The work evokes a sense of chaos unique to New York City and there is a sense of muted drama in the way the figures stand on the crowded sidewalk. In the background people peer from their apartment windows; in the lower right-hand corner a caption reads, ‘Someone shouts from window: Go home! People are dying!!’ {in the COVID pandemic} The sense of urgency is potent. Mumford is not a journalist…but instead allows for the complexities and tensions of the event at hand to emerge."

The dramatic Fine Arts Center at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, where’s you’ll find the Hampden Gallery

Christina Jewett: Did misguided mask advice for hospitals drive up COVID-19 death toll?

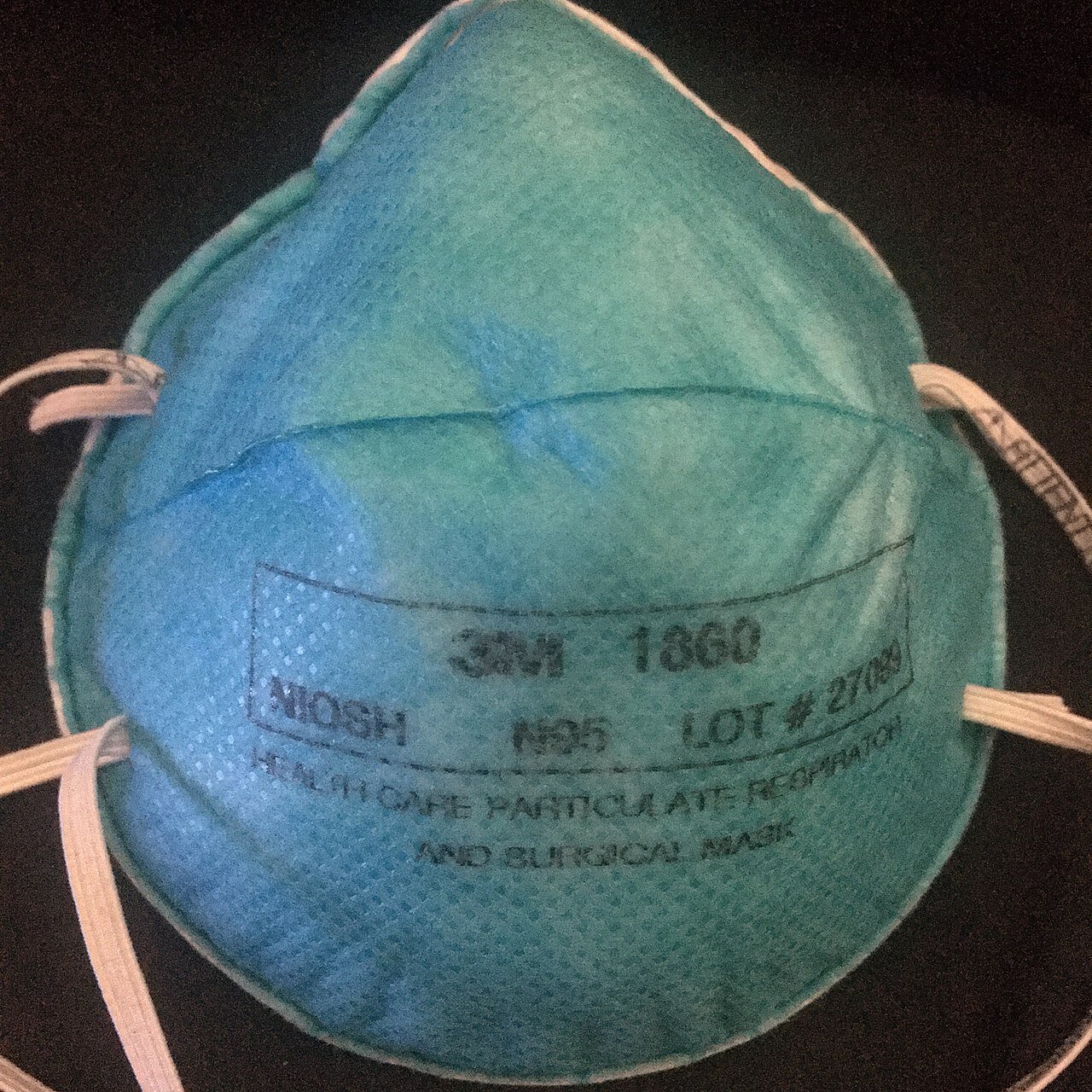

A N95 mask — the safest kind to wear while treating COVID-19 patients

“The whole thing is upside down the way it is currently framed. It’s a huge mistake.’’

— Dr. Michael Klompas, associate professor at the Harvard Medical School, in Boston

Since the start of the pandemic, the most terrifying task in health care was thought to be when a doctor put a breathing tube down the trachea of a critically ill covid patient.

Those performing such “aerosol-generating” procedures, often in an intensive-care unit, got the best protective gear even if there wasn’t enough to go around, per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines. And for anyone else working with covid patients, until a month ago, a surgical mask was considered sufficient.

A new wave of research now shows that several of those procedures were not the most hazardous. Recent studies have determined that a basic cough produces about 20 times more particles than intubation, a procedure one doctor likened to the risk of being next to a nuclear reactor.

Other new studies show that patients with COVID simply talking or breathing, even in a well-ventilated room, could make workers sick in the CDC-sanctioned surgical masks. The studies suggest that the highest overall risk of infection was among the front-line workers — many of them workers of color — who spent the most time with patients earlier in their illness and in sub-par protective gear, not those working in the ICU.

“The whole thing is upside down the way it is currently framed,” said Dr. Michael Klompas, a Harvard Medical School associate professor who called aerosol-generating procedures a “misnomer” in a recent paper in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

“It’s a huge mistake,” he said.

The growing body of studies showing aerosol spread of COVID-19 during choir practice, on a bus, in a restaurant and at gyms have caught the eye of the public and led to widespread interest in better masks and ventilation.

Yet the topic has been highly controversial within the health-care industry. For over a year, international and U.S. nurse union leaders have called for health workers caring for possible or confirmed COVID patients to have the highest level of protection, including N95 masks.

But a widespread group of experts have long insisted that N95s be reserved for those performing aerosol-generating procedures and that it’s safe for front-line workers to care for COVID patients wearing less-protective surgical masks.

Such skepticism about general aerosol exposure within the health-care setting have driven CDC guidelines, supported by national and California hospital associations.

The guidelines still say a worker would not be considered “exposed” to COVID-19 after caring for a sick COVID patient while wearing a surgical mask. Yet in recent months, Klompas and researchers in Israel have documented that workers using a surgical mask and face shield have caught COVID during routine patient care.

The CDC said in an email that N95 “respirators have remained preferred over facemasks when caring for patients or residents with suspected or confirmed” covid, “but unfortunately, respirators have not always been available to health-care personnel due to supply shortages.”

New research by Harvard and Tulane scientists found that people who tend to be super-spreaders of COVID — the 20% of people who emit 80% of the tiny particles — tend to be obese and/or older, a population more likely to live in elder care or be hospitalized.

When highly infectious, such patients emit three times more tiny aerosol particles (about a billion a day) than younger people. A sick super-spreader who is simply breathing can pose as much or more risk to health workers as a coughing patient, said David Edwards, a Harvard faculty associate in bioengineering and an author of the study.

Chad Roy, a co-author who studied other primates with COVID, said the emitted aerosols shrink in size when the monkeys are most contagious at about Day Six of infection. Those particles are more likely to hang in the air longer and are easier to inhale deep into the lungs, said Roy, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Tulane University School of Medicine, in New Orleans.

The study clarifies the grave risks faced by nursing-home workers, of whom more than 546,000 have gotten COVID and 1,590 have died, per reports nursing homes filed to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid since mid-May.

Taken together, the research suggests that health-care workplace exposure was “much bigger” than what the CDC defined when it prioritized protecting those doing “aerosol-generating” procedures, said Dr. Donald Milton, who reviewed the studies but was not involved in any of them.

“The upshot is that it’s inhalation” of tiny airborne particles that leads to infection, said Milton, a professor at the University of Maryland School of Public Health who studies how respiratory viruses are spread, “which means loose-fitting surgical masks are not sufficient.”

On Feb. 10, the CDC updated its guidance to health-care workers, deleting a suggestion that wearing a surgical mask while caring for covid patients was acceptable and urging workers to wear an N95 or a “well-fitting face mask,” which could include a snug cloth mask over a looser surgical mask.

Yet the update came after most of at least 3,500 U.S. health-care workers had already died of COVID, as documented by KHN and The Guardian in the Lost on the Frontline project.

The project is more comprehensive than any U.S. government tally of health-worker fatalities. Current CDC data shows 1,391 health-care worker deaths, which is 200 fewer than the total staff COVID deaths nursing homes report to Medicare.

More than half of the deceased workers whose occupation was known were nurses or in health-care support roles. Such staffers often have the most extensive patient contact, tending to their IVs and turning them in hospital beds; brushing their hair and sponge-bathing them in nursing homes. Many of them — 2 in 3 — were workers of color.

Two anesthetists in the United Kingdom — doctors who perform intubations in the ICU — saw data showing that non-ICU workers were dying at outsize rates and began to question the notion that “aerosol-generating” procedures were the riskiest.

Dr. Tim Cook, an anesthetist with the Royal United Hospitals Bath, said the guidelines singling out those procedures were based on research from the first SARS outbreak in 2003. That framework includes a widely cited 2012 study that warned that those earlier studies were “very low” quality and said there was a “significant research gap” that needed to be filled.

But the research never took place before COVID-19 emerged, Cook said, and key differences emerged between SARS and COVID-19. In the first SARS outbreak, patients were most contagious at the moment they arrived at a hospital needing intubation. Yet for this pandemic, he said, studies in early summer began to show that peak contagion occurred days earlier.

Cook and his colleagues dove in and discovered in October that the dreaded practice of intubation emitted about 20 times fewer aerosols than a cough, said Dr. Jules Brown, a U.K. anesthetist and another author of the study. Extubation, also considered an “aerosol-generating” procedure, generated slightly more aerosols but only because patients sometimes cough when the tube is removed.

Since then, researchers in Scotland and Australia have validated those findings in a paper pre-published on Feb. 10, showing that two other aerosol-generating procedures were not as hazardous as talking, heavy breathing or coughing.

Brown said initial supply shortages of PPE led to rationing and steered the best respiratory protection to anesthetists and intensivists like himself. Now that it is known emergency room and nursing home workers are also at extreme risk, he said, he can’t understand why the old guidelines largely stand.

“It was all a big house of cards,” he said. “The foundation was shaky and in my mind it’s all fallen down.”

Asked about the research, a CDC spokesperson said via email: “We are encouraged by the publication of new studies aiming to address this issue and better identify which procedures in healthcare settings may be aerosol generating. As studies accumulate and findings are replicated, CDC will update its list of which procedures are considered [aerosol-generating procedures].”

Cook also found that doctors who perform intubations and work in the ICU were at lower risk than those who worked on general medical floors and encountered patients at earlier stages of the disease.

In Israel, doctors at a children’s hospital documented viral spread from the mother of a 3-year-old patient to six staff members, although everyone was masked and distanced. The mother was pre-symptomatic and the authors said in the Jan. 27 study that the case is possible “evidence of airborne transmission.”

Klompas, of Harvard, made a similar finding after he led an in-depth investigation into a September outbreak among patients and staff at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, in Boston.

There, a patient who was tested for covid two days in a row — with negative results — wound up developing the virus and infecting numerous staff members and patients. Among them were two patient care technicians who treated the patient while wearing surgical masks and face shields. Klompas and his team used genome sequencing to connect the sick workers and patients to the same outbreak.

CDC guidelines don’t consider caring for a covid patient in a surgical mask to be a source of “exposure,” so the technicians’ cases and others might have been dismissed as not work-related.

The guidelines’ heavy focus on the hazards of “aerosol-generating” procedures has meant that hospital administrators assumed that those in the ICU got sick at work and those working elsewhere were exposed in the community, said Tyler Kissinger, an organizer with the National Union of Healthcare Workers in Northern California.

“What plays out there is there is this disparity in whose exposures get taken seriously,” he said. “A phlebotomist or environmental-services worker or nursing assistant who had patient contact — just wearing a surgical mask and not an N95 — weren’t being treated as having been exposed. They had to keep coming to work.”

Dr. Claire Rezba, an anesthesiologist, has scoured the Web and tweeted out the accounts of health-care workers who’ve died of COVID for nearly a year. Many were workers of color. And fortunately, she said, she’s finding far fewer cases now that many workers have gotten the vaccine.

“I think it’s pretty obvious that we did a very poor job of recommending adequate PPE standards for all health-care workers,” she said. “I think we missed the boat.”

Christina Jewett is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

California Healthline politics correspondent Samantha Young contributed to this report.

Christina Jewett: ChristinaJ@kff.org, @by_cjewett