'Highest treason'

Looking toward Barnstable Harbor

— Photo by ToddC4176

“The highest treason in the USA is to say Americans are not loved, no matter where they are, no matter what they are doing there.’’

Kurt Vonnegut (1922-2007), American writer, probably best known for the novel Slaughterhouse-Five. He lived in 1951-1971 with his family in a house in the village of West Barnstable, part of the Town of Barnstable, that overlooked Barnstable Harbor. Some members of the family still live in the town.

Kurt Vonnegut in 1971, at the height of his fame

David Warsh: Economic models and engineering

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The best book about developments in the culture of professional economics to appear in the last quarter century is, in my opinion, The World in the Model: How Economists Work and Think (Cambridge, 2012), by Mary S. Morgan, of the London School of Economics and the University of Amsterdam. The best book of the quarter century before that is, again, according to me, An Engine, Not a Camera: How Models Shape Financial Markets (MIT, 1997), by Donald MacKenzie, of the University of Edinburgh.

Both books describe the introduction of mathematical models in the years beginning before World War II. Both consider how the subsequent use of those techniques has changed how economics is done by economists. Morgan’s book is about the kinds of models that economists devise experimentally, not those that interest MacKenzie most, models designed to be tested against the real world. A deft cover illustrates Morgan’s preoccupation, showing the interior of a closed room with only a high window. On the floor of the room are written graphic diagram of supply and demand. The window opens only to the sky outside, above the world itself, a world the model-builder cannot see. The introduction of statistical inference to economics she dealt with in The History of Econometric Ideas (Cambridge, 1990).

I remember the surprise I felt when I first read Morgan’s entry “Economics” in The Cambridge History of Science Volume 7: The Modern Social Sciences (Cambridge, 2003). She described two familiar wings of economics, often characterized in the 19th Century as “the science of political economy” and “the art of economic governance.” Gradually in that century they were relabeled “positive” economics (the way it is, given human nature) and “normative” economics (the way it ought to be).

Having practiced economics in strictly literary fashion during the modern subject’s first century, Morgan continued, economists in the second half of the 19th Century began adopting differential calculus as a language to describe their reasoning. In the 20th Century, particularly its second half, the two wings have been firmly “joined together” by their shared use of “a set of technologies,” consisting mainly of mathematics, statistics and models. Western technocratic economics, she wrote, had thereby become “an engineering science.”

I doubted at the time that it was especially helpful to think economics that way.

Having read Economics and Engineering: Institutions, Practices, and Cultures (2021, Duke), I still doubt it. That annual conference volume of the journal History of Political Economy appeared earlier this year, containing 10 essays by historians of thought, with a forward by engineering professor David Blockley, of the University of Bristol, and an afterword by Morgan herself. Three developments – the objectification of the economy as a system; the emergence of tools, technologies and expertise; and a sense of the profession’s public responsibility – had created something that might be understood as “an engineering approach” to the economy and in economics, writes Morgan. She goes on to distinguish between two modes of economic engineering, start-fresh design and fix-it-up problem-solving, noting that enthusiasm for the design or redesign of whole economies and/or vast sectors of them had diminished in the past thirty years.

It’s not that the 10 essays don’t make a strong case for Morgan’s insights about various borrowings from engineering that have occurred over the years: in particular, Judy Klein, of Mary Baldwin University, on control theory and engineering; Aurélien Saïdi, of the University of Paris Nanterre, and Beatrice Cherrier, of the University of Cergy Pontoise and the Ecole Polytechnique, on the tendencies of Stanford University to produce engineers; and William Thomas, of the American Institute of Physics, on the genesis at RAND Corp. of Kenneth Arrow’s views of the economic significance of information.

My doubts have to do with whether the “science” of economics and the practice of its application to social policy have indeed been in fact been “firmly joined” together by the fact that both wings now share a common language. I wonder whether more than a relatively small portion of what we consider to be the domain of economic science is sufficiently well understood and agreed-upon by economists themselves as to permit “engineering” applications.

Take physics. In the four hundred years since Newton many departments of engineering have been spawned: mechanical, civil, electrical, aeronautical, nuclear, geo-thermal. But has physics thereby become an engineering science? Did the emergence of chemical engineering in the 1920s change our sense of what constitutes chemistry? Is biology less a science for the explosion of biotech applications that has taken place since the structure of the DNA molecule was identified in 1953? Probably not.

Some provinces of economics can be considered to have reached the degree of durable consensus that permits experts to undertake engineering applications. I count a dozen Nobel prizes as having been shared for work that can be legitimately described as economic engineering: Harry Markowitz, Merton Miller and William Sharpe, in 1990, for “pioneering work in financial economics”; Robert Merton and Myron Scholes, in 1997, “for a new method to determine the value of derivatives”; Lloyd Shapley and Alvin Roth, in 2012, “for the theory of stable allocations and the practice of market design”: Abajit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer, in 2019, for “their experimental approach to alleviating global poverty”; and Paul Milgrom and Robert Wilson, in 2020, for “improvements to auction theory and inventions of new auction formats.”

This is where sociologist Donald McKenzie comes in. In An Engine Not a Camera, he describes the steps by which, in the course of embracing the techniques of mathematical modeling, finance theory had become “an active force transforming its environment, not a camera, passively recording it,” but an engine, remaking it. When market traders themselves adopted models from the literature, the new theories brought into existence the very transactions of which abstract theory had spoken – and then elaborated them. Markets for derivatives grew exponentially. Such was the “performativity” of the new understanding of finance. After all, writes Morgan in her afterword, hasn’t remaking the world been the goal of economic-engineering interventions all along?

Natural language has a knack for finding its way in these matters. We speak easily of “financial engineering” and “genetic engineering.” But “fine-tuning,” the ambition of macro-economists in the 1960s, is a dimly remembered joke. The 1942 photograph on the cover of Economics and Engineering – graduate students watching while a professor manipulates a powerful instrument laden with gauges and controls – seems like a nightmare version of the film Wizard of Oz.

John Maynard Keynes memorably longed for the day when economists would manage to get themselves thought of as “humble, competent people on a level with dentists.” Nobel laureate Duflo a few years ago compared economic fieldwork to the plumbers’ trade. “The scientist provides the general framework that guides the design…. The engineer takes these general principles into account, but applies them to a specific situation…. The plumber goes one step further than the engineer: she installs the machine in the real world, carefully watches what happens, and then tinkers as needed.”

The $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan Act that became law last week, with its myriad social programs, is not founded on what “the science” says. It is an intuition, an act of faith. Better to continue to refer to most economic programs as “strategies” and “policies” instead of “engineering,” and consider effective implementations to be artful work.

David Warsh, an economic historian and a veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first appeared

Copyright 2021 by David Warsh, proprietor

And waiting for you to leave

“Mighty Aphrodite” (mixed media), by Brookline, Mass., artist Martin R. Anderson, now at Bromfield Gallery, Boston

With a population of about 59,00, Brookline is the most populous municipality in Massachusetts to have a town (rather than city) form of government.

Niche, the ranking and review Web site, placed Brookline as the best place to live in Massachusetts and the 10th best in America.

Brookline was first settled in 1638 as a hamlet of Boston; it was incorporated as a separate town in 1705.

Blandly telling time

Tall-case striking clock made in Boston by Benjamin Bagnall Sr. between 1730 and 1745

— Photo by Daderot

“Back and forth, back and forth

goes the tock, tock, tock

of the orange, bland ambassadorial

face of the moon

on the grandfather clock.’’

— “Fall 1961,’’ by Robert Lowell (1917-1977), among New England’s most famous poets since Robert Frost.

And then back to a friend?

— Photo by Mstrsail

“What good is a friend if you can’t make an enemy of him?’’

— William Hooker Gillette (1853-1937) an innovative and once famous American actor-manager, playwright, and stage-manager, in the late best remembered for portraying Sherlock Holmes.

He is best known now for the bizarre and ingenious Gillette Castle in Lyme, Conn., part of Gillette Castle State Park, which straddles the towns of East Haddam and Lyme. The castle sits high above the Connecticut River. The castle was originally a private residence commissioned and designed by Gillette. It has many strange features and is well worth a visit.

Paul Armentano: Does it matter if pot is stronger these days?

Flowering cannabis (marijuana) plant

Via OtherWords.org

I’ve worked in marijuana policy reform for nearly 30 years. Throughout my career, opponents of legalization have alleged that “today’s” pot is far more potent — and therefore more dangerous — than the cannabis of prior generations.

For instance, former Drug Czar William Bennett claimed in 1990 that if people from the late 1960s “suck on one of today’s marijuana cigarettes, they’d fall down backwards.”

His successor, Lee Brown, claimed in 1995 that “marijuana is 40 times more potent today” than it was decades ago. Not to be outdone, then-Delaware Sen. Joe Biden opined in 1996: “It’s like comparing buckshot in a shotgun shell to a laser-guided missile.”

Taking their hyperbole at face value, the message is clear: Modern marijuana is exponentially stronger and more harmful than the weak, nearly impotent weed of yesteryear.

But that’s not what the drug warriors of yesteryear warned.

During the 1930s, Henry Anslinger, Commissioner of the Bureau of Narcotics, testified to Congress that cannabis is ”entirely the monster Hyde, the harmful effect of which cannot be measured.”

Decades later, in the 1960s and ‘70s, public officials argued that the pot of their era was even stronger. They claimed that smoking “Woodstock weed” would permanently damage brain cells — and that, therefore, possession needed to be heavily criminalized to protect public health.

By the late 1980s, former Los Angeles Police Chief Daryl F. Gates opined that advanced growing techniques had increased THC potency to the point that “those who blast some pot on a casual basis… should be taken out and shot.”

Now a new generation of prohibitionists are recycling the same old claims and scare tactics in a misguided effort to re-criminalize more potent cannabis products in states where their production and sale is legal.

Most recently, these calls have even come from the Senate, including from Senators Diane Feinstein (D-Calif.) and John Cornyn (R-Texas).

So, is there any truth to the claim that today’s weed is so much stronger?

According to marijuana potency data compiled annually by the University of Mississippi at Oxford since the 1970s, one thing is true: The average amount of THC in domestically produced marijuana has increased over time.

But does this elevated potency equate to an increased safety risk? Not necessarily.

Higher-potency cannabis products, such as hashish, have always existed. Marijuana is still the same plant it has always been — with most of the increase in strength akin to the difference between beer and wine, or between a cup of tea and an espresso.

Consuming too much THC at one time can be temporarily unpleasant. But studies have as of yet failed to identify any independent relationship between cannabis use and mental, physical, or psychiatric illnesses.

Furthermore, THC — regardless of potency or quantity — cannot cause death by lethal overdose. Alcohol, by contrast, is routinely sold in lethal dose quantities. Drinking a handle of vodka could easily kill a person, yet vodka is available in liquor stores throughout the country.

Just as alcohol is available in a variety of potencies, from light beer to hard liquor, so is cannabis. So most users regulate their intake accordingly.

Also like with alcohol, cannabis products of the highest potency comprise a far smaller share of the legal marketplace than do more moderately potent products, like flower. According to data published last year in the journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence, nearly eight in ten cannabis consumers prefer herbal cannabis over higher-potency infused concentrates.

Virtually no one thinks alcohol over a certain potency should be re-criminalized. The same should be true of cannabis.

Instead, we should simply make sure consumers know how much THC is in the products they consume and what the effects may be. And we need more diligence from regulators to ensure that legal products for adults don’t get diverted to the youth market.

In other words, let’s address public health concerns with facts, not hyperbole.

Paul Armentano is the deputy director of NORML, the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws. He’s the co-author, with Steve Fox and Mason Tvert, of Marijuana Is Safer: So Why Are We Driving People to Drink?

Anti-marijuana ad from 1935

To tide us over to May

“Vintage Bouquet (Blue Hydrangeas)’’ (mixed media on canvas), by Emily Filler, at Lanoue Gallery, Boston

Wood chips: Green energy?

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

"I should like to have that written over the portals of every church, every school, and every courthouse, and, may I say, of every legislative body in the United States. I should like to have every court begin, 'I beseech ye … think that we may be mistaken.'"

“In the beginning and at the ending let us be content with the Guess’’

- U.S. Appeals Court Judge Learned Hand (1872-1961), legendary federal appeals court judge and philosopher of the law.

I haven’t liked a plan to build a electricity-generating plant in Springfield, Mass., that would burn wood chips. I have feared that it would lead to cutting down a lot of trees, which absorb carbon dioxide. Maybe I was wrong.

The Palmer Renewable Energy Co., which would build the plant, has fired back at its critics. It says that the wood wouldn’t come from cutting down a lot of trees but from the limbs trimmed to protect the power lines, much of which in New England are run through woodlands to avoid residential and commercial areas. But would that provide enough fuel for the plant?

The company notes that the linemen grind these limbs into wood chips that they spray into the woods, where they decompose, releasing the greenhouse-gas methane. The company asserts that methane is “25 times more destructive to our atmosphere than carbon dioxide.’’

Anyway, burning wood chips would be more environmentally sound than generating electricity with fossil fuels, which, unlike wood, has to be bought from outside New England.

I’m sure that the debate over the plant will grind on for a while but the company makes a plausible argument.

'Go home! People are dying!'

“Orthodox Jewish wedding party broken up by NYPD, Lower East Side, NYC, April 20, 2020, 10:30 p.m., 2020” (ink and watercolor on paper), by Steve Mumford, in his show through May 14 at the Hampden Gallery at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

The gallery says:

“The work evokes a sense of chaos unique to New York City and there is a sense of muted drama in the way the figures stand on the crowded sidewalk. In the background people peer from their apartment windows; in the lower right-hand corner a caption reads, ‘Someone shouts from window: Go home! People are dying!!’ {in the COVID pandemic} The sense of urgency is potent. Mumford is not a journalist…but instead allows for the complexities and tensions of the event at hand to emerge."

The dramatic Fine Arts Center at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, where’s you’ll find the Hampden Gallery

Christina Jewett: Did misguided mask advice for hospitals drive up COVID-19 death toll?

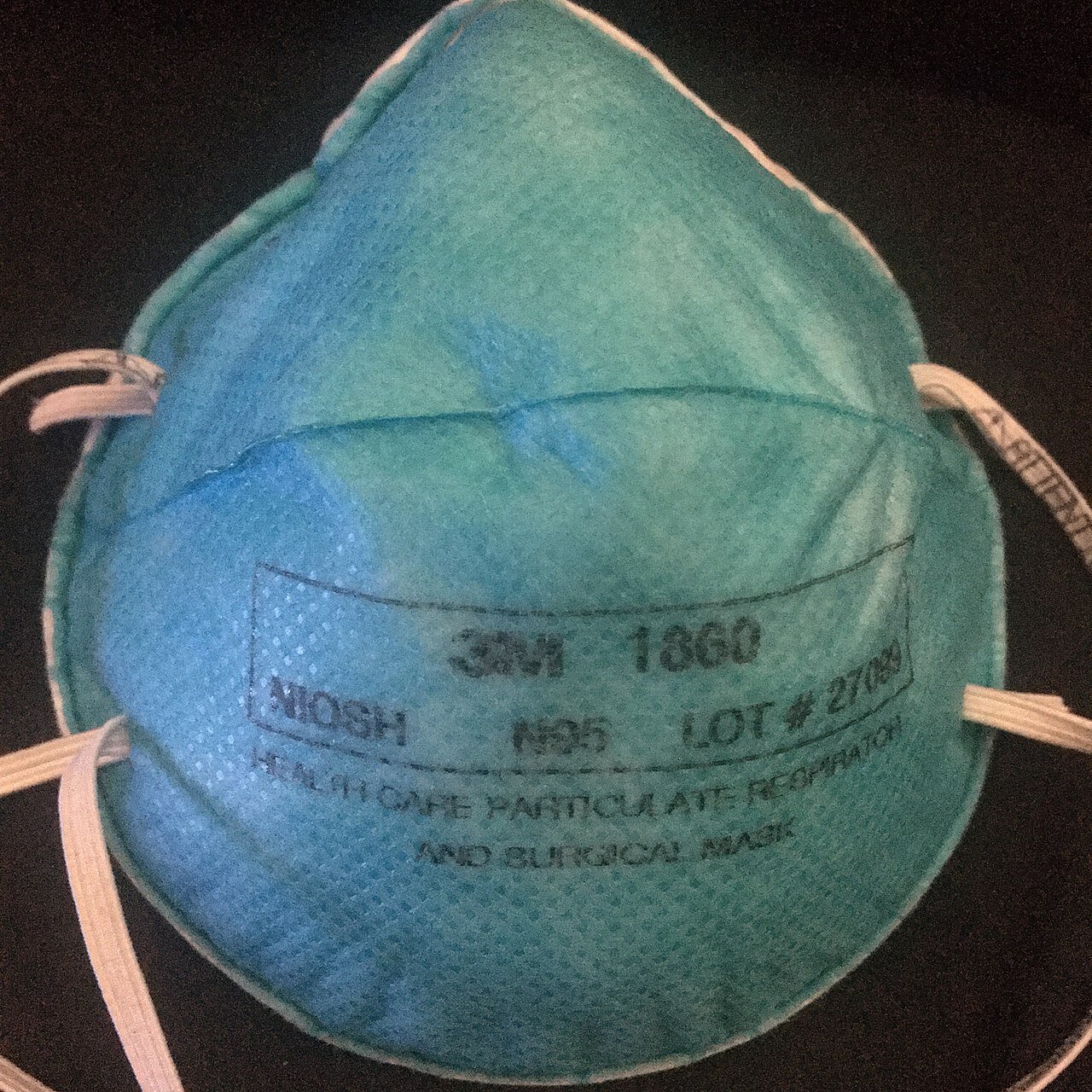

A N95 mask — the safest kind to wear while treating COVID-19 patients

“The whole thing is upside down the way it is currently framed. It’s a huge mistake.’’

— Dr. Michael Klompas, associate professor at the Harvard Medical School, in Boston

Since the start of the pandemic, the most terrifying task in health care was thought to be when a doctor put a breathing tube down the trachea of a critically ill covid patient.

Those performing such “aerosol-generating” procedures, often in an intensive-care unit, got the best protective gear even if there wasn’t enough to go around, per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines. And for anyone else working with covid patients, until a month ago, a surgical mask was considered sufficient.

A new wave of research now shows that several of those procedures were not the most hazardous. Recent studies have determined that a basic cough produces about 20 times more particles than intubation, a procedure one doctor likened to the risk of being next to a nuclear reactor.

Other new studies show that patients with COVID simply talking or breathing, even in a well-ventilated room, could make workers sick in the CDC-sanctioned surgical masks. The studies suggest that the highest overall risk of infection was among the front-line workers — many of them workers of color — who spent the most time with patients earlier in their illness and in sub-par protective gear, not those working in the ICU.

“The whole thing is upside down the way it is currently framed,” said Dr. Michael Klompas, a Harvard Medical School associate professor who called aerosol-generating procedures a “misnomer” in a recent paper in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

“It’s a huge mistake,” he said.

The growing body of studies showing aerosol spread of COVID-19 during choir practice, on a bus, in a restaurant and at gyms have caught the eye of the public and led to widespread interest in better masks and ventilation.

Yet the topic has been highly controversial within the health-care industry. For over a year, international and U.S. nurse union leaders have called for health workers caring for possible or confirmed COVID patients to have the highest level of protection, including N95 masks.

But a widespread group of experts have long insisted that N95s be reserved for those performing aerosol-generating procedures and that it’s safe for front-line workers to care for COVID patients wearing less-protective surgical masks.

Such skepticism about general aerosol exposure within the health-care setting have driven CDC guidelines, supported by national and California hospital associations.

The guidelines still say a worker would not be considered “exposed” to COVID-19 after caring for a sick COVID patient while wearing a surgical mask. Yet in recent months, Klompas and researchers in Israel have documented that workers using a surgical mask and face shield have caught COVID during routine patient care.

The CDC said in an email that N95 “respirators have remained preferred over facemasks when caring for patients or residents with suspected or confirmed” covid, “but unfortunately, respirators have not always been available to health-care personnel due to supply shortages.”

New research by Harvard and Tulane scientists found that people who tend to be super-spreaders of COVID — the 20% of people who emit 80% of the tiny particles — tend to be obese and/or older, a population more likely to live in elder care or be hospitalized.

When highly infectious, such patients emit three times more tiny aerosol particles (about a billion a day) than younger people. A sick super-spreader who is simply breathing can pose as much or more risk to health workers as a coughing patient, said David Edwards, a Harvard faculty associate in bioengineering and an author of the study.

Chad Roy, a co-author who studied other primates with COVID, said the emitted aerosols shrink in size when the monkeys are most contagious at about Day Six of infection. Those particles are more likely to hang in the air longer and are easier to inhale deep into the lungs, said Roy, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Tulane University School of Medicine, in New Orleans.

The study clarifies the grave risks faced by nursing-home workers, of whom more than 546,000 have gotten COVID and 1,590 have died, per reports nursing homes filed to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid since mid-May.

Taken together, the research suggests that health-care workplace exposure was “much bigger” than what the CDC defined when it prioritized protecting those doing “aerosol-generating” procedures, said Dr. Donald Milton, who reviewed the studies but was not involved in any of them.

“The upshot is that it’s inhalation” of tiny airborne particles that leads to infection, said Milton, a professor at the University of Maryland School of Public Health who studies how respiratory viruses are spread, “which means loose-fitting surgical masks are not sufficient.”

On Feb. 10, the CDC updated its guidance to health-care workers, deleting a suggestion that wearing a surgical mask while caring for covid patients was acceptable and urging workers to wear an N95 or a “well-fitting face mask,” which could include a snug cloth mask over a looser surgical mask.

Yet the update came after most of at least 3,500 U.S. health-care workers had already died of COVID, as documented by KHN and The Guardian in the Lost on the Frontline project.

The project is more comprehensive than any U.S. government tally of health-worker fatalities. Current CDC data shows 1,391 health-care worker deaths, which is 200 fewer than the total staff COVID deaths nursing homes report to Medicare.

More than half of the deceased workers whose occupation was known were nurses or in health-care support roles. Such staffers often have the most extensive patient contact, tending to their IVs and turning them in hospital beds; brushing their hair and sponge-bathing them in nursing homes. Many of them — 2 in 3 — were workers of color.

Two anesthetists in the United Kingdom — doctors who perform intubations in the ICU — saw data showing that non-ICU workers were dying at outsize rates and began to question the notion that “aerosol-generating” procedures were the riskiest.

Dr. Tim Cook, an anesthetist with the Royal United Hospitals Bath, said the guidelines singling out those procedures were based on research from the first SARS outbreak in 2003. That framework includes a widely cited 2012 study that warned that those earlier studies were “very low” quality and said there was a “significant research gap” that needed to be filled.

But the research never took place before COVID-19 emerged, Cook said, and key differences emerged between SARS and COVID-19. In the first SARS outbreak, patients were most contagious at the moment they arrived at a hospital needing intubation. Yet for this pandemic, he said, studies in early summer began to show that peak contagion occurred days earlier.

Cook and his colleagues dove in and discovered in October that the dreaded practice of intubation emitted about 20 times fewer aerosols than a cough, said Dr. Jules Brown, a U.K. anesthetist and another author of the study. Extubation, also considered an “aerosol-generating” procedure, generated slightly more aerosols but only because patients sometimes cough when the tube is removed.

Since then, researchers in Scotland and Australia have validated those findings in a paper pre-published on Feb. 10, showing that two other aerosol-generating procedures were not as hazardous as talking, heavy breathing or coughing.

Brown said initial supply shortages of PPE led to rationing and steered the best respiratory protection to anesthetists and intensivists like himself. Now that it is known emergency room and nursing home workers are also at extreme risk, he said, he can’t understand why the old guidelines largely stand.

“It was all a big house of cards,” he said. “The foundation was shaky and in my mind it’s all fallen down.”

Asked about the research, a CDC spokesperson said via email: “We are encouraged by the publication of new studies aiming to address this issue and better identify which procedures in healthcare settings may be aerosol generating. As studies accumulate and findings are replicated, CDC will update its list of which procedures are considered [aerosol-generating procedures].”

Cook also found that doctors who perform intubations and work in the ICU were at lower risk than those who worked on general medical floors and encountered patients at earlier stages of the disease.

In Israel, doctors at a children’s hospital documented viral spread from the mother of a 3-year-old patient to six staff members, although everyone was masked and distanced. The mother was pre-symptomatic and the authors said in the Jan. 27 study that the case is possible “evidence of airborne transmission.”

Klompas, of Harvard, made a similar finding after he led an in-depth investigation into a September outbreak among patients and staff at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, in Boston.

There, a patient who was tested for covid two days in a row — with negative results — wound up developing the virus and infecting numerous staff members and patients. Among them were two patient care technicians who treated the patient while wearing surgical masks and face shields. Klompas and his team used genome sequencing to connect the sick workers and patients to the same outbreak.

CDC guidelines don’t consider caring for a covid patient in a surgical mask to be a source of “exposure,” so the technicians’ cases and others might have been dismissed as not work-related.

The guidelines’ heavy focus on the hazards of “aerosol-generating” procedures has meant that hospital administrators assumed that those in the ICU got sick at work and those working elsewhere were exposed in the community, said Tyler Kissinger, an organizer with the National Union of Healthcare Workers in Northern California.

“What plays out there is there is this disparity in whose exposures get taken seriously,” he said. “A phlebotomist or environmental-services worker or nursing assistant who had patient contact — just wearing a surgical mask and not an N95 — weren’t being treated as having been exposed. They had to keep coming to work.”

Dr. Claire Rezba, an anesthesiologist, has scoured the Web and tweeted out the accounts of health-care workers who’ve died of COVID for nearly a year. Many were workers of color. And fortunately, she said, she’s finding far fewer cases now that many workers have gotten the vaccine.

“I think it’s pretty obvious that we did a very poor job of recommending adequate PPE standards for all health-care workers,” she said. “I think we missed the boat.”

Christina Jewett is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

California Healthline politics correspondent Samantha Young contributed to this report.

Christina Jewett: ChristinaJ@kff.org, @by_cjewett

Todd McLeish: Frozen frogs are thawing out for spring but face death on the roads

Wood frog

— Photo by Brian Gratwicke

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

The onset of the coronavirus pandemic a yer ago coincided with the annual migration of frogs and salamanders to their breeding ponds, a trek that often results in mass mortalities as they cross roads trying to reach their preferred waterbody. The lockdown during the early stages of the pandemic last year gave a significant reprieve to amphibian populations, reducing roadway mortalities by as much as half, according to a New England researcher.

But this year, with traffic back to near normal levels, frogs and salamanders aren’t likely to fare as well. And wood frogs will likely be at the top of the list of roadkill victims.

In southern New England, wood frogs are one of the first signs of spring, according to herpetologist Mike Cavaliere, the Audubon Society of Rhode Island’s stewardship specialist. They are the first species to emerge from their winter hibernation, typically in mid to late March. And as soon as they awaken, he said, they hop to their breeding pools to seek a mate on the first night it rains.

“What’s particularly amazing about wood frogs is that they can produce a natural antifreeze that allows them to almost freeze completely solid in winter,” Cavaliere said. “This antifreeze is produced when the frogs start to feel ice crystals begin to form in late fall.”

Unique among frogs in the Northeast, the wood frog’s antifreeze is a chemical reaction between stored urine and glucose, which protects a frog’s cells and organs from freezing while allowing the rest of its body to freeze.

“Its brain shuts down, its heart stops, its lungs stop, everything stops for months. It’s like they’re in suspended animation,” Cavaliere said. “And once spring comes, they thaw out and the heart starts beating again. After about a day, they start hopping around, eating and mating right away. It’s an amazing feat of evolution that they’ve developed.”

Wood frogs are often joined by spring peepers and spotted salamanders in migrating to their breeding pools during rainy nights in March, but it’s the frogs that are killed in the greatest numbers.

“Road mortality is one of the great seemingly unassessed sources of pressure for amphibians,” said Greg LeClair, a graduate student at the University of Maine who coordinates The Big Night, an amphibian monitoring project to quantify the roadkill of frogs and salamanders during their spring migration. “We know that disease and climate are affecting amphibians, but road mortality has long been suspected to be a serious problem, though there is no data to quantify population declines.”

LeClair said that road mortality can be as high as 100 percent in some areas when traffic is high during the one night of the season that most migration takes place.

“The average is 20 percent of amphibians at any road crossing will get nailed by a car in a given year,” he said. “That’s devastating for some species.”

During The Big Night, volunteers at 300 sites around Maine typically find two living amphibians crossing the road for every one dead one. But last year, with far fewer vehicles on the road because of the pandemic, twice as many frogs and salamanders survived the journey. In fact, a study by the Road Ecology Center found that pandemic lockdowns last year spared millions of animals from roadway deaths.

“We had record survival, but we’ll never be able to replicate that data again,” said LeClair, noting the impossibility of experimentally reducing region-wide traffic levels like happened with the pandemic.

While last year’s reduction in road mortality probably resulted in a short-term increase in amphibian populations, LeClair said that doesn’t mean there will be more breeding activity this year, since it takes several years for amphibians to grow to adulthood and begin breeding.

“It will take a couple years to determine if amphibian populations benefitted from the pandemic. My suspicion is leaning toward no benefit,” he said. “Most amphibian populations are driven by juvenile survival more than adult survival, so impacts to juveniles have stronger impacts than impacts to adults. Dispersing juveniles last summer likely encountered normal-level traffic as they left the pool to find a territory.”

Whether wood frogs and other amphibians benefitted from the pandemic shutdowns, their increased survival rate last spring almost certainly benefitted other wildlife.

“Their eggs and tadpoles are a major food source for other animals in spring,” Cavaliere said. “It’s one of the first sources of protein available, so spotted turtles and other reptiles and amphibians will eat them, as will any other scavenger who’s hungry in spring and looking for protein.”

Those interested in helping scientists gather data about frog populations in Rhode Island should sign up to participate in FrogWatch through the Roger Williams Park Zoo. Online training for the program is available through March 31.

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish, an ecoRI News contributor, runs a wildlife blog.

'Shape-shifting magic'

“Lock” (photo), by Ayşe Goloğlu Soyer, M.D., in her show Korondaşlar, at Kingston Gallery, Boston, May 5-30.

Dr. Soyer is a retired neurologist who has never exhibited before.

The gallery says of her:

“Because she grew up immersed in the art world in Turkey, one wouldn’t label her work outsider art, yet she works with a fresh, unselfconscious inventiveness. Her artist statement is a fanciful imagined conversation between the creator and her creations, her Korondaşlar, laden with memories of her WWII childhood in Istanbul. ‘That’s how it was. The war crept on. There were days we went without electricity, water, sometimes food. Not saying I miss that part. What I’m saying is that it led me to the great discovery that not having toys didn’t mean not having anything to play with, why I have no memories of being idle or bored. We had our shapeshifting folded paper boats, our origami salt shakers, cups, magical boxes in different sizes that, when need be, changed into dollhouses and cars, those cast-off buttons that when threaded on string became bracelets, when put against metal became musical instruments. And if our old torn socks were too worn to be unraveled and re-knitted, they were dolls ready to be stuffed and stuffed animals to be made. And we, gathering them up and placing them on the blue plastic muşamba were able to sail them on a baby blanket from the Marmara to the North Sea. The creativity that sprouted within us from the seed of paucity grew into abundance. It didn’t leave time for boredom.’

“The expressive figures populating the center gallery, fashioned during the isolation of the pandemic from cast-off materials scavenged from the streets and her household, and represented in large photographs on the walls of the gallery, share that same shape-shifting magic.’’’

Alternate ways of seeing

Movie poster for Timothy Leary's Dead

“Women who seek equality with men lack ambition.’’

— Timothy Leary (1920-1996, the Springfield, Mass.-born American psychologist and writer known for his strong advocacy of psychedelic drugs.

As a clinical psychologist at Harvard University, Leary worked on LSD and mushroom studies, resulting in the Concord Prison Experiment and the Marsh Chapel Experiment. The scientific legitimacy and ethics of his research were questioned by other Harvard faculty because he took psychedelics along with research subjects and pressured students to join in. Harvard fired him in 1963.

After that, he continued to publicly promote the use of psychedelic drugs and became a famous figure of the counterculture of the 1960s and after. He popularized such catchphrases as "turn on, tune in, drop out", "set and setting” and "think for yourself and question authority".

He spent much time in jail and on the lecture circuit before dying of prostate cancer in California.

Llewellyn King: In the post-talking-on-phone era, cell phones get ever snazzier

Still triumphant iPhones

Scrapped, superseded mobile phones

— Photo by MikroLogika

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Delve into your bank account or find a credit card that isn’t maxed out and do it. You know you want to. You know you must. You know you can’t resist. You want, must have, to hell with the expense, the latest cell phone.

Of course, the cell phone you have is perfectly good and does everything you want. That isn’t the point. When you are in need of a technology fix, utility isn’t a consideration.

Your old cell phone, truth be told, was such a whizzy little computer that you could ask it to read your e-mail aloud or you could surreptitiously enjoy watching old television shows such as Mister Ed. Now it must be cast out. You have read the CNET review that details pixel counts, camera capacity and battery longevity. The new phone, the one that you may have to raid your child’s college fund to acquire, is a must-have.

Here is a tip: Google until you are bug-eyed. It is lazy just to buy the top Android from Samsung or the latest iPhone from Apple. There are about 120 companies making cell phones. There are a dozen you can buy without going to China.

Imagine that if you have a phone that is unique, the opportunity for one-upping your pals is limitless. Think of these conversations just waiting:

“Bill, is that a new iPhone? I just bought a Blankety Blank. Actually, it is superior. You should see how I mapped a trajectory for a Mars flight on it.”

Or “Susan, you got the latest from Samsung? I guess it is great, but I really need extra functions. I can shoot and edit a feature film on this little beauty from Blankety Blank. It writes the script, too.”

Warning: When you have made one of these asinine comments, move away.

You can spend more than $3 million on a cell phone. An Australian businessman commissioned such a phone. It was replete with a 22-carat gold case, rubies and diamonds. I wonder what it weighed. More, I wonder if it worked. I don’t expect to find that model at Walmart. But don’t be downcast, if you have just $2.5 million to blow on a phone, there are several in your price range. Of course, these have nothing to do with telephony, they are pure fashion -- like those watches that cost millions and are made in Switzerland, the home of great watches, with humble, Chinese-made moving parts.

Even if you hold onto your old instrument or buy the latest, it seems the one thing you won’t be doing is making phone calls.

We are living in the post-phone age. If, God forbid, we are to speak to someone on the phone, an appointment has to be set up by email or text (a cell phone capacity actually used). So a simple phone call becomes work, something to cause tension, apprehension, dread. I don’t think anyone ever made an appointment to call you to tell you that you are coming into money or to tell you they have accepted your marriage proposal.

I have lived through the ages of the telephone, as defined by an instrument connected to similar that enables you to talk to someone else.

The first age was the party line. I call it the public line because you could listen to anyone on the same line.

Then there was the age of the rotary. Dial, dial, dial. If, like me, you had to make a lot of phone calls, it was hell. We had pencils with rubber-blob ends to insert into the dial to ease the finger labor. The pushbutton was nirvana. A huge advance in user-friendliness.

Then came the age of the answering machine. It was the thin end of the wedge which subtracted years from lives because it led inexorably to those automatic phone systems that won’t let you speak to a human being, whether it is a doctor or a manager about your, yes, telephone account.

No doubt there will be sociologists writing about the death of talking on the telephone. I, for one, always loved a ringing telephone, before robocalls, of course, because that call might be something that, as Omar Khayyam said, transmutes “life’s leaden metal into gold.”

Sometimes phone calls (RIP) did that.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, PBS. His e-mail address is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

'Cynicism is fear'

Ken Burns

“I think we too often make choices based on the safety of cynicism, and what we’re led to is a life not fully lived. Cynicism is fear, and it’s worse than fear; it’s active disengagement.’’

—Ken Burns (born 1953) celebrated maker of documentary films on topics in American history. His production company is Florentine Films, based in Walpole, N.H. The company’s name came from co-founder Elaine Mayes’s hometown of Florence, Mass. Burns attended Hampshire College, in nearby Amherst, Mass.

The Walpole, N.H. Town Hall

Before Spring's color explosion

“Hiatus No. 2" (encaustic & mixed media on 30" panels), by Robin Luciano Beaty, at Lanoue Gallery, Boston

The Boston-based artist writes:

“My work is driven by the intuitive journey of discovering the reminiscent through process rather than rendering an explicit space. My intention is to spark personal recollections in the viewer from an unconventional perspective using unexpected materials. I’m communicating more of a memory than a representation with the use of texture, neglected everyday objects and forgotten mementos of the past. Though the fluvial and sculptural qualities of wax , I navigate memory. Scraping, tearing, building up and burning down multiple layers to reveal internal compositions brought out only by this tactile and physical experience.

“In my most recent work, I strive to capture the universal and emotional connection to water embedded within our life memories. Oceans, rivers and lakes are instilled in our subconscious scrapbook, creating an undeniable feeling of nostalgia and escape. I am able to reclaim these memories in a significantly more personal way by incorporating vintage photographs, letters, textiles and found objects. By repurposing forgotten objects within my own private retrospective process, I bring back to life the very intimate recollections of another, along with igniting the viewers’ own.”

John O. Harney: New England and other experts address racial and economic reckoning'

Logo of the Color of Change reform group

BOSTON

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Even in this time when people presume to be having a “racial reckoning,” signs of enduring racial inequity pop up everywhere. From nagging disparities in health—Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) die at higher rates than other groups from COVID-19 and are underrepresented in medical research (except in vile experiments such as in the Tuskegee study) … to the steep declines in Black and Latino students submitting the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) … to Black food-service workers experiencing disproportionate short-tipping for enforcing social-distancing rules … inequality reigns. These persistent forces should be a big deal for New England’s Historically White Colleges and Universities, which are rarely called out as HWCUs.

Some help is on the way. Beside targeting $128.6 billion for the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund, $39.6 billion to the Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund, $39 billion for child care and $1 billion for Head Start, the new $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief plan does other less visible things to begin to address structural racism. For example, the package provides Black farmers with debt relief and help acquiring land. Black farmers lost more than 12 million acres of farmland over the past century, attributed to systemic racism and inequitable access to markets.

I’ve been trying to monitor the racial-equity conversation mostly via Zoom since the pandemic began. This mention of aid to Black farmers reminded me of something I heard Chuck Collins say at a webinar convened last month by MIT’s Sloan School of Management via Zoom titled “The Inclusive Innovation Economy: Amplifying Our Voices Through Public Policy’’.

Collins is the director of inequality and the common good at the Institute for Policy Studies and a white man. He told of his uncle getting a 1 percent fixed-rate mortgage in 1949 to buy an Ohio farm—a public investment that led his cousins to get on “America’s wealth-building train.” Black and Brown people did not get the same benefits. Collins suggested that systems such as CARES relief should be examined with a racial-equity lens, as should policies such as raising the minimum wage or forgiving student loans. Unquestionably, Black students struggle more than whites with student debt. But with Capitol Hill debating the right amount of debt to forgive, Collins suggested we need to test how well these changes would affect racial inequity.

Dynastic wealth

Noting that we’re living through an updraft of “dynastic wealth,” Collins asked why the U.S. taxes work income higher than income from investments. He pointed out that “50 families in the U.S. that are now in their third generation of billionaires coming online and that represents a sort of Democracy-distorting and market-distorting concentration of wealth and power.”

That distortion could be partly cushioned with a “dignity floor,” said Collins. “It’s not a coincidence that a society like Denmark has much higher rates of entrepreneurship than the U.S. per capita because they have a social-safety net and because they have social investments that create a decency floor through which people cannot all. So if you want to start a business, you know you can take that leap and not end up living in your car.”

We need to disrupt the narrative of “everyone is where they deserve to be,” said Collins. So many entrepreneurs tell their story from the standpoint of I did this. We need to talk about the web of supports and multigenerational advantages behind their ability to take the step they took.

Color-coded

An audience member asked if a bridge could be built to connect the rich and poor. To this, one of the conversation moderators, Sloan School lecturer and former chief experience and culture officer at Berkshire Bank Malia Lazu, quipped that in the U.S., there’s another dimension: The sides of the bridge are “color-coded.”

Lazu and co-moderator Fiona Murray, associate dean for innovation and inclusion at Sloan, agreed that ironically this is how the policies were designed to work. That’s why we need to change how the systems are wired.

It’s not that Black people are less likely to get loans from banks, but that banks are less likely to give loans to Black people, explained Color of Change President Rashad Robinson. Shifting the subject that way, he said, has led to remedies like financial literacy programs for Black people, rather than changes in the policies of big banks.

Color of Change was formed in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, which, like COVID-19, disproportionately hurt Black and Brown people. Narrative is not static, Robinson said, reminding the audience of what people might have unabashedly said in the workplace about LGBT people just 15 years ago.

Moreover, budgets are “moral documents,” Robinson pointed out. So if you say you’re going to prosecute more corruption crimes than street crime, that has to be reflected in budgets. People of color are not vulnerable, they’ve been targeted, added Robinson, who is working on a report that will look at not only Black pain, but also Black joy and how BIPOC are portrayed in stories on TV.

An audience questioner asked which policies actually embed structural racism. Lazu pointed to the U.S. Constitution’s original clause declaring that any person who was not free would be counted as three-fifths of a free individual. For a more modern example, Robinson noted minimum-wage laws that exclude certain kinds of work, originally farm workers and domestic workers, now work usually done by people of color and women. Structural racism is rooted in how our economy is designed, said Robinson. “An equity focus means we’re not just trying to undo harm but we’re trying to create systems and structures that actually move us forward.”

Afraid to bring children into the world

Also last month, the Boston Social Venture Partners convened a Zoom webinar with affiliates in San Antonio and Denver to discuss how nonprofit leaders have struggled to implement strategies that funders require for diversity, equity and inclusion.

The conversation was moderated by Michael Smith, executive director of the Obama Foundation’s My Brother’s Keeper Alliance, based in Washington, D.C. The alliance was created in 2014 in the aftermath of the killing of Trayvon Martin and aimed at addressing opportunity gaps. It works today against the backdrop of the COVID pandemic and resulting school closures, an economic downturn and police violence in communities of color.

Another Obama fellow, Charles Daniels, the executive director of Boston-based Father’s Uplift, explained: “We have a shortage of clinicians of color in this country—sound, qualified therapists who are able to provide that necessary guidance,” he said. “One of the main requests of single mothers bringing their children to us or fathers entering our agency is that they want a clinician of color, someone who looks like them,” he said. “There are conversations they don’t know necessarily how to have with their loved ones about racism, about oppression, about maintaining their dignity and self-respect.”

Daniels noted that constituents are grappling with what to tell sons about getting pulled over by the police and daughters about what their school may say about hairstyles. “These are conversations that people of color dread this day and age. They wake up trying to parent their inner child and also parent the child who they brought into this world.” He notes that some constituents are actually afraid of having children for these reasons.

A young Black man told Daniels that if he had a choice to be white, he would take it: “I wouldn’t have to worry about my life every time I go to school,” the child suggested, or “an administrator being on my back in school because she’s assuming I’m not doing my work because I don’t care as opposed to me not being able to feed my stomach because I’m hungry.” Daniels said these are real-life situations that young men and single mothers struggle with on a daily basis.

When the federal government recently sent relief stipends, many men of color were left out for not paying child support as if they just didn’t want to pay, when the real reason was they couldn’t afford it.

Growing up as a person of color, you’re taught that you have to be near perfect. You can’t get away with things other populations can, said Daniels. He added: “If someone of color who you’re vetting sends an email with an error, it doesn’t mean they’re incompetent; it probably means they’re doing more than one thing or wearing two hats.” He said he likes funders who offer technical support, as well as authentic conversation, and who don’t avoid the word “racism.”

Giant triplets

Meanwhile, the Quincy Institute, led by retired U.S. Army colonel and noted critic of the Iraq War-turned Boston University professor Andrew Bacevich, held a virtual “Emergency Summit” of public intellectuals to reflect on America Besieged by Racism, Materialism and Militarism—the “giant triplets” identified by Martin Luther King, Jr. in his 1967 speech “Beyond Vietnam.”

Against the backdrop of the Jan. 6 Capitol insurrection, Bacevich began by asking the panelists how those triplets continue to threaten democracy.

One panelist, New York Times contributing writer Peter Beinart, noted that one of the triplets, materialism, while an enormous cultural problem, might not rank as one of the three main ones today because, unlike in the 1960s when people assumed that American living standards would be going up, many today suffer from a lack of materialism and hold very little hope that their situations will improve.

Militarism and racism, however, do persist. As a foreign-policy term, however, “militarist” has been replaced by euphemisms such as “muscular” or “tough-minded.” But militarism is plain to see in the degree to which domestic policing has been affected by military equipment, and veterans return home without decent healthcare. (As an aside, the military has been lauded for well-run coronavirus vaccine sites while the civilian counterparts are often cast as failures. Asked why this is on a recent television news show, Alex Pareene, a staff writer for The New Republic, offered a simple explanation: The U.S. has never disinvested in the military.)

One panelist, the Rev. Liz Theoharis, who is co-chair with Rev. William Barber, of the Poor People’s Campaign, said she would add to King’s triplets, two more demons: ecological devastation and emboldened religious nationalism evidenced on Jan. 6.

Regarding militarism, Theoharis noted that while there’s no military draft per se, there is a “poverty draft” because for many young people, it’s the only way to put food on their table and get an education. Yet, they come home to a lack of opportunity. The majority of single male adults that are homeless in our society are veterans. The military system is “not about the ideals of a democracy and opportunity and possibility and freedom for all, it’s sending poor people, Black people and Latino people to go and fight and kill poor people in other parts of the world,” she said, noting that the U.S. has military bases in more than 800 places. The coronavirus threat has spread in the fissures that we faced before in terms of racism and inequality, which were already claiming lives before the pandemic.

Neta C. Crawford, a professor and chair of political science at Boston University, said democracy is the antidote to militarism, extreme materialism and racism. Members of Congress are tightly connected to military bases and defense contractors in their districts based on the belief that the military-industrial complex creates good jobs. Crawford said we need break this misconception with solid analysis that shows military spending actually produces fewer jobs and what we could be doing instead.

Daniel McCarthy, editor of Modern Age: A Conservative Review and editor-at-large of The American Conservative, noted the irony that U.S. military adventures abroad are framed as antiracist. When he opposed the Iraq War, he was accused of being against Arab democracy and therefore racist. He lamented that we need to find something for the part of industrial America that has been declining, not necessarily related to militarism but to make things that people want to buy.

Justice and belonging in New England

This webinar surfing spree came as NEBHE renewed its focus on diversity, equity and inclusion. The terms “justice” and “belonging” are sometimes also added to the collection of values that used to be disparaged as so much p.c. Moreover, “diversity” is not enough on its own because, as one New England college president recently told his colleagues, people can feel welcomed but also disadvantaged. NEBHE has also looked at the concept of “reparative” justice as a way to recognize that fighting racial oppression should not be responsive to specific past wrongs, but rather, driven by the understanding that the past, present and future exist together.

To be sure, New England will thrive only if its education systems promote inclusion and excellence for learners of all backgrounds, cultures, age groups, lifestyles and learning styles in an environment that promotes justice and equity in a diverse, multicultural world.

John O. Harney is executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

Chris Powell: A corrupt and ridiculous tribal casino duopoly

— Photo by Ralf Roletschek

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Gambling and intoxicating drugs mainly transfer wealth from the many to the few and the poor to the rich, so it is sad that state government is striving to get into the business of sports betting, internet gambling, and marijuana dealing. That's how hungry state government always is for more money.

Even so, Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont may deserve some credit for the deal he seems about to achieve with Connecticut's two casino Indian tribes. The tribes long have claimed that the casino gambling duopoly state government conferred on them in the 1990s also gives them exclusivity on sports betting and internet gambling in the state.

Under the governor's plan the tribes drop their claim to exclusivity and share the sports betting and internet gambling business with state government via the Connecticut Lottery. The Mohegan tribe has fully accepted the plan while the Mashantucket Pequot tribe appears to have yielded on exclusivity and to be quibbling only about a percentage point or two in taxes.

So Connecticut may be glad that this much of its sovereignty would be recognized and that the governor didn't give the store away.

But just as this outcome could be worse, it could be better too. For state government has shown no interest in inquiring whether it really needs the Indian tribal duopoly to run casinos -- inquiring whether the casino exclusivity the state has conferred on the tribes in exchange for 25 percent of their slot machine revenue reflects the full value of the state's grant of duopoly.

After all, the duopoly has never been put out to bid. Would other enterprises pay the state more for the privilege of operating casinos and sports betting parlors in, say, Bridgeport, New Haven, and Hartford, locations far closer to heavily populated areas than the Indian properties in southeastern Connecticut's woods? Casino operators in those cities, much closer to more gamblers, might gladly pay state government more than 25 percent of their slot machine take, or their 25 percent tribute might produce more money because they had more customers.

This potential for greater revenue is implied by the complaint of Sportstech, operator of the state-licensed horse and greyhound racing and jai alai betting parlors throughout Connecticut. The company is threatening to sue the state because it hasn't been invited into the gambling expansion plan with the casino Indians. No other potential operators seem to have been solicited either.

So the governor's plan will preserve gambling in Connecticut as a business for privileged insiders -- the two tribes, which have come to control enough legislators in their part of the state to block state government from following the ordinary good business practice of soliciting bids.

The gambling situation in Connecticut is not just essentially corrupt but ridiculous as well, as indicated by the crack taken last week at the Mohegans by the chairman of the Mashantucket Pequots, Rodney Butler, who was sore that the Mohegans didn't wait for the Pequots before agreeing to the governor's plan. "It opened up wounds between our tribal nations that go back centuries," Butler said, referring to the alliance of the Mohegans with the English colonists in the war with the Pequots nearly 400 years ago.

Can ethnic hatreds really endure that long when the ethnicities have been so absorbed by the larger culture? Can a distant descendant of Chief Sassacus and a distant descendant of Chief Uncas really resent each other after their intermediary generations have lived in raised ranches and worked at Electric Boat like nearly everyone else where the tribes of old lived? Aren't these people with tiny fractions of Indian descent more likely to dispute each other over the Yankees and the Red Sox or Biden and Trump?

Or is the revival of the Pequot War just a pathetically opportunistic defense of lucrative privilege?

Connecticut is full of people who are suffering serious disadvantages arising from all sorts of things that were not their fault, disadvantages far greater than a tiny bit of relation to the tribes of old. Indeed, for decades that relation has been no disadvantage to anyone. State government offers these truly disadvantaged people nothing special.

While some of them soon may be given marijuana-dealing licenses, if Connecticut were to be run on ethnicity, they would deserve casinos far more than the people who have them now.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.