Vox clamantis in deserto

Swampy sight

Skunk cabbages are among the first plants to show new life in New England swamps in late winter.

“A New Hampshire swamp is full of attractions at all seasons.’’

— Frank Bolles (1856-1894) in At the North of Bearcamp Water

Will in-person town meetings Zoom away?

Town meeting in Huntington. Vt.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

March is New England town meeting time, but this year many – most? -- such proceedings have been virtual, by Zoom, etc. I suppose that in some towns the in-person meeting may never come back. That’s in part because so many people have gotten so used to inter-acting most of the day on screens, and attending virtual meetings is easier for many people than going there physically. But easier doesn’t necessarily mean better. (Is the long lack of in-person encounters making some people more timid?)

I’ve attended town meetings over the years in various communities. It’s hard to beat the up-close-and-personal encounters and voting in person, if you’re looking for basic democracy. At many of them, votes are taken by voice or a show of hands. Seeing the body language, and hearing the informal chats before and after the meetings, the often entertaining free-form debates, the droll, sardonic remarks of the town moderators, and reading the paper documents explaining the proposals to be voted on – all good stuff.

And there’s something seasonally heartening about town meetings. They come as winter is losing its grip, there’s a smell of thawing earth in the air and the sunlight is brighter. They’re a marker of spring.

The Town House of Marlboro, Vt., was built in 1822 to be used for town meetings, which had previously been held in private homes. It is still in use today.

Frost in Bennington

“Apple Tree & Grindstone” (1923, wood engraving), by J.J. Lankes (1884-1960), in the Bennington (Vt.) Museum’s show “At Present in Vermont,’’ opening in April.

(Courtesy Rauner Special Collections Library, Dartmouth College.)

The museum says:

A century ago “Robert Frost arrived in Bennington County, where he lived from 1920 to 1938. Coming in April to Bennington Museum, a new major exhibit… explores Frost’s life and work as an artist and farmer and celebrates the New England legacy of America’s most beloved poet.’’

Ho-Jo fried clams were addictive too

Founded in Quincy, Mass., in 1925, this was by far the most famous restaurant chain to come out of New England.

Almost enough to make you forget

‘‘The first demure newcomer’’

The sun falls warm: the southern winds awake:

The air seethes upwards with a steamy shiver:

Each dip of the road is now a crystal lake,

And every rut a little dancing river.

Through great soft clouds that sunder overhead

The deep sky breaks as pearly blue as summer:

Out of a cleft beside the river's bed

Flaps the black crow, the first demure newcomer.

The last seared drifts are eating fast away

With glassy tinkle into glittering laces:

Dogs lie asleep, and little children play

With tops and marbles in the sun-bare places;

And I that stroll with many a thoughtful pause

Almost forget that winter ever was.

“In March, by Archibald Lampman (1861-1899), Canadian poet

Don Pesci: Time to pivot in Connecticut

The neo-classical City Hall in Bridgeport, like all Connecticut cities heavily Democratic

— Photo by Jerry Dougherty

The Connecticut state seal. The Latin motto means “He Who Transplanted Still Sustains"

VERNON, Conn.

Optimists who believe in free markets – the opposite of which are unfree, illiberal, highly regulated markets – knew, shortly after Coronavirus slammed into the United States from Wuhan, China, that the virus and the free market were inseparably connected. The more often autocratic governors restricted the public market, the more often jobs would be lost, and the loss of jobs and entrepreneurial capital everywhere would necessarily punch holes in state budgets. In many cases, the holes were prepunched by governors and legislators who, before the Coronavirus panic, had failed to understand the direct connection between high taxes, which depletes creative capital, and sluggish economies. For the last thirty years, it has taken Connecticut ten years to recover from national recessions.

The dialectic of getting and spending is a matter of simple observation and logic: the more governments get in taxes, the more they spend; the more they spend, the greater the need for taxation. Excessive spending – more properly, the indisposition to cut spending – takes a toll on capital formation and use, which leads to business flight and all its attendant evils, such as high unemployment, entrepreneurial stagnation and lingering recessions.

There would come a time, post-Coronavirus, free-market optimists thought, when states would begin to pivot from artificially constricting the economy by means of gubernatorial emergency power declarations to a much desired return to organic normalcy. That pivot already has been put in motion by governors in many conservative woke states.

The entire Northeast has for many years been the victim of the past successes of Democrat politics, which involves harvesting votes by buying them, usually by dispensing tax dollars and power-sharing to reliable political constituencies. Large cities in Connecticut – Hartford, Bridgeport, New Haven, have been held captive by Democrats for nearly a half century. During the last few elections – President Donald Trump’s 2016 election, disappointing to Clintonistas, being the most conspicuous exception to the rule – Democrats have been able to cobble together epicentric majorities in most power centers in the Northeast, relying upon large cities to carry them over the election goal line. This strategy has had, until now, little to do with political ideology and a great deal to do with campaign acumen and a leftward lurch on social issues long abandoned by Connecticut Republicans. Presence in politics has always been more important than little understood ideologies, and Connecticut Republicans have been absent without leave on social issues for decades.

Over time, Democrats, by focusing on social issues, have managed to move what used to be called the “vital center” in national politics much further to the left. And this ideological shift has hurt 1) Republicans who seem unable or unwilling to gain a foothold on important social issues, 2) liberal “{John} Kennedy” Democrats now caught in political limbo following a recent neo-progressive upsurge, and 3) disadvantaged groups, once the mainstay of liberal politics in the ‘”Camelot” era of President Kennedy, now frozen politically and socially in empathy cement, finding no way forward into what once had been a robust middle class.

There is no question, even among progressives who wish to move money from privileged, disappointingly white millionaires to despairing non-white urban voters, that a vibrant economy lifts all the boats. The distribution of zero dollars is zero, and there simply is not enough money in the bulging bank accounts of Connecticut’s millionaires to finance the state’s welfare system for more than a few years – even if it were possible for eat-the-millionaires, white, privileged, neo-progressives to expropriate all the surplus riches of Connecticut’s “Gold Coast” millionaires and send the dispossessed to work in re-education farms in West Hartford. No middle class tide, no lift. Yesterday, today and tomorrow, it will be Connecticut’s dwindling middle class that will carry the “privileged” white man’s burden.

Like other governors in the Northeast, Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont, who stumbled into Nutmeg State politics without much political experience, has become, thanks to Coronavirus and the inveterate cowardice of legislators, a plenary governor the likes of which the Republic has not seen since American patriots – the word “patriot” was first used as a reproach against benighted revolutionaries by monarchists – chased agents of King George III out of their country.

Both Lamont and his friend New York Gov Andrew Cuomo have worn their plenary powers well, but the Coronavirus scourge is receding, and Cuomo has “slipped in blood.” Worst of all, representative government in some states appears to be making a comeback, and people are beginning to resent facemasks and gubernatorial edits as signs and symbols of their own powerless assent to a very un-republican subservience.

Politicians across the state and nation would be wise to step in front of a populist republican reformation before they are carted off in revolutionary tumbrils.

Pivot now. Later will be too late.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

David Warsh: Of Biden in '72, Trump now and economic engineering

Reading The Wealth of Nations was a revelation for David Warsh

Calibrate v, trans. to determine the caliber of; spec. to try the bore of a thermometer, or similar instrument, so as to allow in graduating it for any irregularities; to graduate a gauge of any kind with allowance for its irregularities.

Nearly fifty years ago, I showed up as a new employee at the Wilmington (Del.) News-Journal on election night, 1972, the evening that New Castle County Councilor Joe Biden was elected to the U.S. Senate. Biden was 29, I was 28. The second-floor newsroom bubbled with intoxicating excitement and indignation. (President Richard Nixon had carried 49 states). But when Biden was elected president last autumn, I felt as though I had somehow turned the page.

I don’t know whether it was four years of Donald Trump, twelve months of COVID-19, the passage of nearly twenty years since I last worked for a newspaper, or faint memories of New Castle County politics, but a week ago I found the column I was working on, about economics and engineering, more interesting than the prospects of Biden’s presidency. I recognized late in the day that I hadn’t found a way to make it interesting to readers of Economic Principals, my Web site. So I put the topic aside and took a bye. Walking home, I remembered the title of Albert Hirschman’s little book Shifting Involvements: Private Interests and Public Action.

On the other hand, as a copyboy at Chicago’s City News Bureau in 1963, my second assignment had been to cover a Walter Heller press conference at the Palmer House hotel. Heller was then chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers. My attendance at the session was perfunctory; the news desk didn’t want a story. But from the Palmer House on, I was looking someplace other than City Hall in which to invest my interests.

That was all the more so after I returned to college to read history of social thought. Just five authors were on the calendar of the sophomore tutorial that year: Alexis de Tocqueville, Karl Marx, Emile Durkheim, Max Weber and Sigmund Freud. That was the year they omitted Adam Smith altogether and his Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, perhaps because of the temper of the times (this was 1970-71). When a couple of years after that, in the course of another assignment, I went back to read Smith for myself, it was a revelation. I have been fundamentally interested ever since in the stories we tell (and don’t tell) about economics.

Take that column about economic engineering. I found myself thinking over the last few days not so much about the conclusion of an independent market monitor that the operator of Texas’s power-grid had overcharged residents as much $16 billion during a cold snap last month as about Gov. Greg Abbott’s decision to end the state’s mask mandate and permit businesses to reopen at 100 percent capacity.

The decision to permit the highest legal rates to apply for as much as 32 hours longer than warranted was been reviewed Friday by the Texas Electricity Reliability Council, which declined to reverse the charges, even though the principles would seem to be well-established among specialists. “It’s just nearly impossible to unscramble this sort of egg,” the new chair of the Public Utility Commission said during a commission meeting.

But principles for telling people when and where to wear masks are anything but well-understood and universally agreed-upon. They have something to do with what we call culture. As economist David Kreps said of his 2018 book, The Motivation Toolkit: How to Align Your Employees’ Interests with Your Own: “My colleagues here [at Stanford University and its Graduate School of Business] don’t think this is economics, but it is.” I cannot seem to put that book away.

Economic Principals, says in its flag, “Economic Principals: a weekly column about economics and politics, formerly of The Boston Globe, independent since 2002.” Economic Principals has written frequently about politics for the last five years. Going forward, I hope put the subject mostly on autopilot.

The Trump presidency was accidental. It happened only because so many voters deemed inappropriate a Hillary Rodham Clinton presidency. Trump’s tenure proved to be a turning point, a climax, a crisis that slowly will resolve.

How close he came to re-election! How desperately he fought to hold on to office, even after he lost! The sharpest student of Trump’s career I know, who follows the literature much more widely than I do, believes it was because the now-former president understands that he is facing ruin. Suspicion of money laundering for Russian purchasers of apartments is at the heart of the case.

What I expect to happen is this: the Republican Party will gradually rebuild itself, election by election, as new generations – Gen X (b. 1961-1981) and the Millennials (b. 1982– 2004) take over from the Boomers (b. 1943-1960). The Democratic Party will take advantage of a strong economy and threats posed by the rising great-power competitor that is China to deliver the country into a new era. Congressional elections will be closely fought every two years, but I am guessing that the Democrats may remain in the White House until 2032, though only the Republicans have won the presidency three straight times since Harry Truman.

Meanwhile, I’ll return to engineering and economics next week, and try again to find something interesting to say about blueprints, instruments, and toolkits. Plenty of other columns are already in line. Re-calibration complete!

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville, Mass.-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran.

MBTA revisioning its trains

MBTA commuter train at South Station, Boston

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The MBTA will soon be changing its commuter-train and subway and bus schedules to not only save money but also to reflect how the lives of so many of us have been permanently changed by the pandemic.

Rush-hour commuting has much diminished in the pandemic and won’t return to its pre-COVID levels. That’s because many people will continue to work at home post-pandemic. Employers have found that they can get at least as much productivity out of their people working remotely as they could in company offices, while saving a lot in office costs. (Unfortunately, some of those costs are thrown onto the employees.) Further, many, maybe most, employees dislike commuting, which has been infamously unpleasant in Greater Boston. But some folks like commuting, for the solitude and thinking time it can give them.

Laboring at home has eroded the old 9-5 job routines, meaning for many longer but more fragmented working hours – and making many homes less of a psychological refuge.

In any event, train and subway travel will be more spread out during the day, and more of it will be non-work-related.

Commonwealth Magazine reports that the plan is to spread MBTA service out across the day at “regular, often hourly intervals rather than concentrating it at morning and evening peak periods.’’ Say hourly or half-hourly rail service between Providence and Boston and hourly service between Worcester and Boston. And some have suggested extending commuter-rail lines from Boston, say all the way out to Pittsfield and Springfield, or to Bourne, on the edge of Cape Cod.

Happily, the agency is dropping a plan to cut off commuter rail service at 9 p.m. weekdays, instead it will continue service until 11 p.m., important to, for example, many people attending a game or other evening event in Boston.

Whatever, as travel opens up with fading of the pandemic, let’s hope that the public-transit cutbacks that it has caused can be mostly reversed, to avoid a massive increase in automobile traffic, much of it with one person per car.

To read more about the MBTA changes, please hit this link.

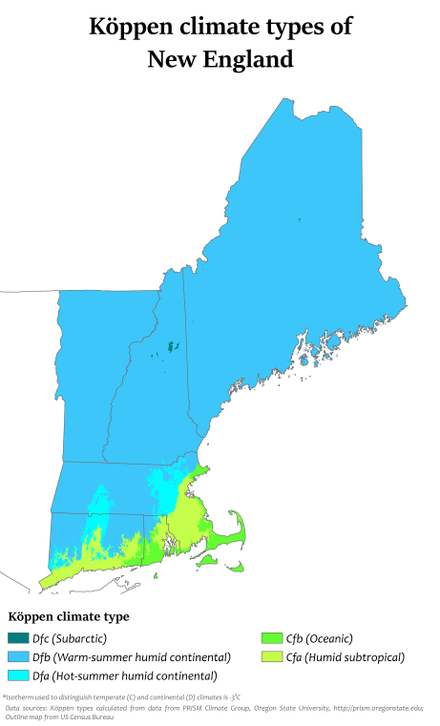

'Sharp differentiation'

“In New England we have but to step across the border of the adjoining state to feel at once the sharp differentiation, the geological cut-off which expresses itself in the general aspect of the land and in the thousand and one simple facts of its topography, its flora, its fauna, its people, its customs, its coast, its climate, and its industries.’’

— Helen Henderson, in A Loiterer in New England (published in 1919)

Aboriginal art

“Tjapaltjarri” (c. 1935/40-2002) “Men's Maliyarre (Initiation) Ceremony’’ (acrylic on linen), by Clfford Possum, at LaiSun Keane gallery, Boston, through March 28, in the group show “Kinship: Art of Australia.’’

These canvas paintings , all by Australian Aborginal artists, depict the culture, history and customs of that group ,whose ancestors lived for 50,000 years on the continent before the arrival of English colonizers, in 1788. The gallery says that these paintings “contain important narratives passed down through generations, yet these are disguised in abstract patterns to protect their cultural secrets and keep them sacred.’’

A kid Zombie goes to Witch Town

This was printed as a result of the Salem Witch Trials of 1692-1693

“Without really analyzing it, I grew up in Massachusetts, so the Salem Witch Trials were always something that I was around. The average kindergartner probably doesn't know about it, except that in Massachusetts, you do, because they'll take you on field trips to see reenactments and stuff.’’

— Robert Bartleh Cummings (born 1965), known professionally as Rob Zombie, an American singer, songwriter, filmmaker and voice actor. He was born and raised in Haverhill, Mass.

“The Worshipping Tree,” in Haverhill, in 2012. It’s where 17th Century English colonists are said to have conducted their Calvinist ceremonies.

A waffle or the Texas electrical grid?

”Slanting Grid” (acrylic and beeswax on muslin with canvas, polyester fiber and thread), by Meg Lipke, in her show “In the Making,’’ at Burlington City Arts, Burlington, Vt,. through May 15.

The gallery says that Ms. Lipke seeks to challenge conventional notions of painting by drawing on “20th Century modernism, past craft traditions and memories of her mother and grandmother's creative practices to create soft paintings and totemic sculptures of canvas and cloth. She works with her chosen materials to create forms that resemble long, disembodied limbs, pushing the limits of contemporary abstraction.’’

Part of her upbringing was in Burlington but she now lives and works in Brooklyn.

The Church Street Marketplace in Burlington

Mass. bill would mandate solar panels on new buildings

Installing solar panels on a house

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Massachusetts legislators have filed two bills that would require rooftop solar panels to be installed on new residential and commercial buildings.

The Solar Neighborhoods Act, filed by Rep. Mike Connolly (D.-Cambridge) and Rep. Jack Lewis (D.-Framingham), would require solar panels to be installed on the roofs of newly built homes, apartments, and office buildings. The bill allows for exemptions if a roof is too shaded for solar panels to be effective. A similar bill was filed by Sen. Jamie Eldridge (D.-Acton).

Connolly said the legislation is a necessary step in a transition away from fossil fuels to renewable energy.

“Combating climate change will require robust solutions, and the mobilization of all of our resources, so I’m excited to reintroduce this legislation and continue working with my colleagues and stakeholders in taking this bold step forward,” he said.

A 2018 report from the Environment America Research & Policy Center found that requiring rooftop solar panels on all new homes built in Massachusetts would add more than 2,300 megawatts of solar capacity by 2045, nearly doubling the solar capacity that has been installed in Massachusetts to date.

The amount of installed solar-energy capacity has increased more than 70-fold in Massachusetts during the past decade, according to Environment America. In recent years, the growth of solar has been held back by arbitrary caps on the state’s most important solar energy policy, net metering, as well as uncertainty over solar incentive programs, according to Ben Hellerstein, state director for Environment Massachusetts.

Massachusetts could generate up to 47 percent of its electricity from rooftop solar panels, according to a 2016 study from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

During the last legislative session, the Joint Committee on Telecommunications, Utilties and Energy gave a favorable report to similar legislation, but it didn’t advance to a vote on the floor of either chamber.

“Every day, a clean, renewable, limitless source of energy is shining down on the roofs of our homes and businesses,” Hellerstein said. “With this bill, we can tap into our potential for rooftop solar energy and take a big step toward a healthier, safer future.

‘Wearable art,’ up to a point

“Are You Thirsty?’’ (plastic bottles and cotton cloth), by Antonaeta Tica, a Romanian artist, in Arts Center East’s (Vernon, Conn.) “2nd Annual Wearable Art Exhibit,’’ an international show, through March 13.

The center says:

“The art pieces featured in the exhibit are as diverse as the locations of their artists. While there are plenty of textiles, hats and other expected wearable mediums, the exhibit also features hair art, fashion photography, repurposed trash fashion and other unconventional forms of wearable art”.

The Memorial Tower on Fox Hill, in Vernon, was completed in 1939 as a collaborative WPA project to hire workers during the Great Depression and invest in projects to benefit local cities. It is dedicated to the veterans of all wars from Vernon.

Regions in search of a country

See “The Nine Nations of North America,’’ by Joel Garreau

— Map by A Max J -

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Colin Woodard’s book Union: The Struggle to Forge the Story of United States Nationhood is at its core a narrative of how wishful thinking, racism and willful ignorance led historians to promote pictures of America that ignored the huge impact of slavery/Jim Crow and regionalism. (Note that a previous Woodard book was entitled American Nations.)

He sees the United States as having developed mostly region by region -- politically, economically and culturally -- and not in a unitary way. Consider “Greater New England’’; the Planter Class of Tidewater Virginia and Maryland down to Georgia, and the tough Scots-Irish in the Border States and interior South. The caste system that developed with slavery had a great deal to do with how the last two groups turned out.

Mr. Woodard mostly tells his tale through biographies of five people: New England’s George Bancroft (1800-1891), a very intellectually dishonest but popular historian; South Carolina writer and politician William Gilmore Simms (1806-1870), a romanticist of the slave-owning South, especially its “aristocratic’’ coastal Planter Class; Frederick Douglass (1818-1895) the great abolitionist, orator and writer; historian Frederick Jackson Turner (1861-1932), whose theories about sectionalism and the role of the frontier revolutionized the teaching of American history, and Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924), the deeply racist president, political scientist and popular historian.

After reading this book I was again reminded of how it still sometimes seems more a collection of quasi-countries than a unified country. Just look at our national elections up to last November!

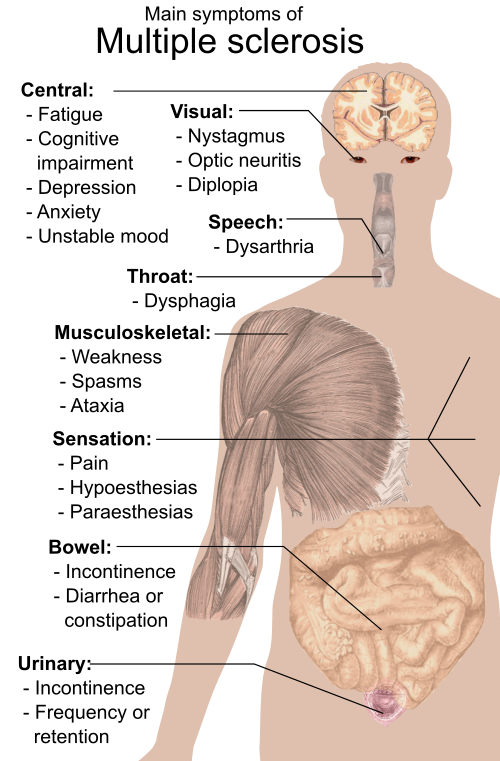

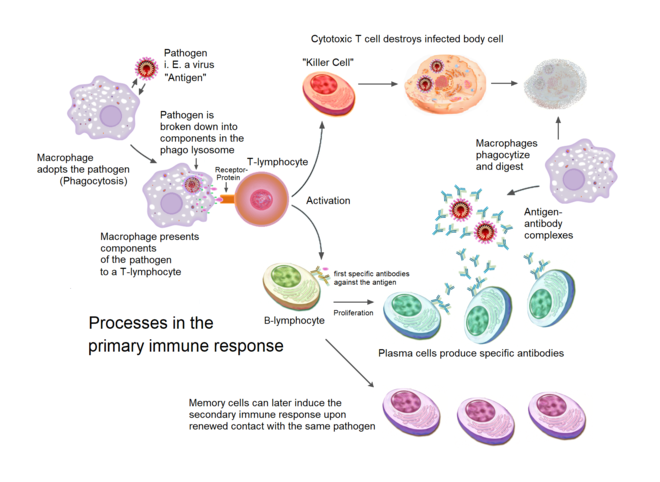

Liz Szabo: COVID-19 can disrupt the immune system in very dangerous ways

-Graphic by Sciencia58

“These are the air traffic controllers,” If these proteins are disrupted, “your immune system doesn’t work properly.”

— Aaron Ring, M.D., assistant professor of immunology at the Yale School of Medicine

There’s a reason soldiers go through basic training before heading into combat: Without careful instruction, green recruits armed with powerful weapons could be as dangerous to one another as to the enemy.

The immune system works much the same way. Immune cells, which protect the body from infections, need to be “educated” to recognize bad guys — and to hold their fire around civilians.

In some C0VID patients, this education may be cut short. Scientists say unprepared immune cells appear to be responding to the coronavirus with a devastating release of chemicals, inflicting damage that may endure long after the threat has been eliminated.

“If you have a brand-new virus and the virus is winning, the immune system may go into an ‘all hands on deck’ response,” said Dr. Nina Luning Prak, co-author of a January study on covid and the immune system. “Things that are normally kept in close check are relaxed. The body may say, ‘Who cares? Give me all you’ve got.’”

While all viruses find ways to evade the body’s defenses, a growing field of research suggests that the coronavirus unhinges the immune system more profoundly than previously realized.

Some covid survivors have developed serious autoimmune diseases, which occur when an overactive immune system attacks the patient, rather than the virus. Doctors in Italy first noticed a pattern in March 2020, when several covid patients developed Guillain-Barré syndrome, in which the immune systems attacks nerves throughout the body, causing muscle weakness or paralysis. As the pandemic has surged around the world, doctors have diagnosed patients with rare, immune-related bleeding disorders. Other patients have developed the opposite problem, suffering blood clots that can lead to stroke.

All these conditions can be triggered by “autoantibodies” — rogue antibodies that target the patient’s own proteins and cells.

In a report published in October, researchers even labeled the coronavirus “the autoimmune virus.”

“Covid is deranging the immune system,” said John Wherry, director of the Penn Medicine Immune Health Institute and another co-author of the January study. “Some patients, from their very first visit, seem to have an immune system in hyperdrive.”

Although doctors are researching ways to overcome immune disorders in covid patients, new treatments will take time to develop. Scientists are still trying to understand why some immune cells become hyperactive — and why some refuse to stand down when the battle is over.

Key immune players called “helper T cells” typically help antibodies mature. If the body is invaded by a pathogen, however, these T cells can switch jobs to hunt down viruses, acting more like “killer T cells,” which destroy infected cells. When an infection is over, helper T cells usually go back to their old jobs.

In some people with severe covid, however, helper T cells don’t stand down when the infection is over, said James Heath, a professor and president of Seattle’s Institute for Systems Biology.

About 10% to 15% of hospitalized COVID patients Heath studied had high levels of these cells even after clearing the infection. By comparison, Heath found lingering helper T cells in fewer than 5% of covid patients with less serious infections.

In affected patients, helper T cells were still looking for the enemy long after it had been eliminated. Heath is now studying whether these overzealous T cells might inflict damage that leads to chronic illness or symptoms of autoimmune disease.

“These T cells are still there months later and they’re aggressive,” Heath said. “They’re on the hunt.”

COVID appears to confuse multiple parts of the immune system.

In some patients, covid triggers autoantibodies that target the immune system itself, leaving patients without a key defense against the coronavirus.

In October, a study published in Science led by Rockefeller University’s Jean-Laurent Casanova showed that about 10% of covid patients become severely ill because they have antibodies against an immune system protein called interferon.

Disabling interferon is like knocking down a castle’s gate. Without these essential proteins, invading viruses can overwhelm the body and multiply wildly.

New research shows that the coronavirus may activate preexisting autoantibodies, as well as prompt the body to make new ones.

In the January study, half of the hospitalized covid patients had autoantibodies, compared with fewer than 15% of healthy people. While some of the autoantibodies were present before patients were infected with SARS-CoV-2, others developed over the course of the illness.

Other research has produced similar findings. In a study out in December, researchers found that hospitalized covid patients harbored a diverse array of autoantibodies.

While some patients studied had antibodies against virus-fighting interferons, others had antibodies that targeted the brain, thyroid, blood vessels, central nervous system, platelets, kidneys, heart and liver, said Dr. Aaron Ring, assistant professor of immunology at Yale School of Medicine and lead author of the December study, published online without peer review. Some patients had antibodies associated with lupus, a chronic autoimmune disorder that can cause pain and inflammation in any part of the body.

In his study, Ring and his colleagues found autoantibodies against proteins that help coordinate the immune system response. “These are the air traffic controllers,” Ring said. If these proteins are disrupted, “your immune system doesn’t work properly.”

COVID patients rife with autoantibodies tended to have the severest disease, said Ring, who said he was surprised at the level of autoantibodies in some patients. “They were comparable or even worse than lupus,” Ring said.

Although the studies are intriguing, they don’t prove that autoantibodies made people sicker, said Dr. Angela Rasmussen, a virologist affiliated with Georgetown’s Center for Global Health Science and Security. It’s possible that the autoantibodies are simply markers of serious disease.

“It’s not clear that this is linked to disease severity,” Rasmussen said.

The studies’ authors acknowledge they have many unanswered questions.

“We don’t yet know what these autoantibodies do and we don’t know if [patients] will go on to develop autoimmune disease,” said Dr. PJ Utz, a professor of immunology and rheumatology at Stanford University School of Medicine and a co-author of Luning Prak’s paper.

But recent discoveries about autoantibodies have excited the scientific community, who now wonder if rogue antibodies could explain patients’ differing responses to many other viruses. Scientists also want to know precisely how the coronavirus turns the body against itself — and how long autoantibodies remain in the blood.

‘An Unfortunate Legacy’

Scientists working round-the-clock are already beginning to unravel these mysteries.

A study published online in January, for example, found rogue antibodies in patients’ blood up to seven months after infection.

Ring said researchers would like to know if lingering autoantibodies contribute to the symptoms of “long COVID,” which afflicts one-third of covid survivors up to nine months after infection, according to a new study in JAMA Network Open.

“Long haulers” suffer from a wide range of symptoms, including debilitating fatigue, shortness of breath, cough, chest pain and joint pain, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Other patients experience depression, muscle pain, headaches, intermittent fevers, heart palpitations and problems with concentration and memory, known as brain fog.

Less commonly, some patients develop an inflammation of the heart muscle, abnormalities in their lung function, kidney issues, rashes, hair loss, smell and taste problems, sleep issues and anxiety.

The National Institutes of Health has announced a four-year initiative to better understand long covid, using $1.15 billion allocated by Congress.

Ring said he’d like to study patients over time to see if specific symptoms might be explained by lingering autoantibodies.

“We need to look at the same patients a half-year later and see which antibodies they do or don’t have,” he said. If autoantibodies are to blame for long covid, they could “represent an unfortunate legacy after the virus is gone.”

Widening the Investigation

Scientists say the coronavirus could undermine the immune system in several ways.

For example, it’s possible that immune cells become confused because some viral proteins resemble proteins found on human cells, Luning Prak said. It’s also possible that the coronavirus lurks in the body at very low levels even after patients recover from their initial infection.

“We’re still at the very beginning stages of this,” said Luning Prak, director of Penn Medicine’s Human Immunology Core Facility.

Dr. Shiv Pillai, a Harvard Medical School professor, notes that autoantibodies aren’t uncommon. Many healthy people walk around with dormant autoantibodies that never cause harm.

For reasons scientists don’t completely understand, viral infections appear able to tip the scales, triggering autoantibodies to attack, said Dr. Judith James, vice president of clinical affairs at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation and a co-author of Luning Prak’s study.

For example, the Epstein-Barr virus, best known for causing mononucleosis, has been linked to lupus and other autoimmune diseases. The bacteria that cause strep throat can lead to rheumatic fever, an inflammatory disease that can cause permanent heart damage. Doctors also know that influenza can trigger an autoimmune blood-clotting disorder, called thrombocytopenia.

Researchers are now investigating whether autoantibodies are involved in other illnesses — a possibility scientists rarely considered in the past.

Doctors have long wondered, for example, why a small number of people — mostly older adults — develop serious, even life-threatening reactions to the yellow fever vaccine. Three or four out of every 1 million people who receive this vaccine — made with a live, weakened virus — develop yellow fever because their immune systems don’t respond as expected, and the weakened virus multiplies and causes disease.

In a new paper in the Journal of Experimental Medicine, Rockefeller University’s Casanova has found that autoantibodies to interferon are once again to blame.

Casanova led a team that found three of the eight patients studied who experienced a dangerous vaccine reaction had autoantibodies that disabled interferon. Two other patients in the study had genes that disabled interferon.

“If you have these autoantibodies and you are vaccinated against yellow fever, you may end up in the ICU,” Casanova said.

Casanova’s lab is now investigating whether autoantibodies cause critical illness from influenza or herpes simplex virus, which can cause a rare brain inflammation called encephalitis.

Calming the Autoimmune Storm

Researchers are looking for ways to treat patients who have interferon deficiencies — a group at risk for severe covid complications.

In a small study published in February in the Lancet Respiratory Medicine, doctors tested an injectable type of interferon — called peginterferon-lambda — in patients with early covid infections.

People randomly assigned to receive an interferon injection were four times more likely to have cleared their infections within seven days than the placebo group. The treatment, which used a type of interferon not targeted by the autoantibodies Casanova discovered, had the most dramatic benefits in patients with the highest viral loads.

Lowering the amount of virus in a patient may help them avoid becoming seriously ill, said Dr. Jordan Feld, lead author of the 60-person study and research director at the Toronto Centre for Liver Disease in Canada. In his study, four of the placebo patients went to the emergency room because of breathing issues, compared with only one who received interferon.

“If we can bring the viral levels down quickly, they might be less infectious,” Feld said.

Feld, a liver specialist, notes that doctors have long studied this type of interferon to treat other viral infections, such as hepatitis. This type of interferon causes fewer side effects than other varieties. In the trial, those treated with interferon had similar side effects to those who received a placebo.

Doctors could potentially treat patients with a single injection with a small needle — like those used to administer insulin — in outpatient clinics, Feld said. That would make treatment much easier to administer than other therapies for covid, which require patients to receive lengthy infusions in specialized settings.

Many questions remain. Dr. Nathan Peiffer-Smadja, a researcher at the Imperial College London, said it’s unclear whether this type of interferon does improve symptoms.

Similar studies have failed to show any benefit to treating patients with interferon, and Feld acknowledged that his results need to be confirmed in a larger study. Ideally, Feld said, he would like to test interferon in older patients to see whether it can reduce hospitalizations.

“We’d like to look at long haulers, to see if clearing the virus quickly could lead to less immune dysregulation,” Feld said. “People have said to me, ‘Do we really need new treatments now that vaccines are rolling out?’ Unfortunately, we do.”

Liz Szabo is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Liz Szabo: lszabo@kff.o

Early spring

Black boughs against a pale, clear sky,

Slight mists of cloud-wreaths floating by;

Soft sunlight, gray-blue smoky air,

Wet thawing snows on hillsides bare.

–Emma Lazarus (1849–87)

Llewellyn King: Ireland -- an island of glorious contradictions that charms the world, especially on March 17

The Humbert Monument on Humbert Street in Ballina, County Mayo, Ireland. It honors Jean Joseph Amable Humbert, who was sent by Napoleon to assist the Irish with the uprising against the English in 1798.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Where I live things are beginning to turn green with a hint of spring. But it isn’t just the flora here that has an intimation of green. The whole country, indeed, the whole world, is greening for St. Patrick’s Day.

The most extraordinary thing happens on that day: People around the world shed their ethnic identities to take on an Irish one. On March 17, the world decides that it is Irish and that it must, as the Irish do, take a drink.

No other country commandeers the world as does that small island nation set in the North Atlantic. On the day when an otherwise obscure saint is celebrated, the world wears some item of green and quaffs something fermented or distilled.

For me, Ireland has always been a place of glorious contradictions and great writers – Joyce, Yeats, Shaw, Wilde, Swift, O’Brien, Beckett and Lewis, come to mind in no order, and there are hundreds more.

It isn’t just that its writers are among the greatest, but also that the Irish speak poetically, eschewing the simple answer, embroidering the boring cloth of fact, and sometimes confusing those who don’t have the gift of deciphering eloquence.

An Irish friend, John McCaughey, and I were walking with our wives in Kinsale, on the southwest coast of Ireland, when we came upon a tempting pub and were tempted. It wasn’t open, but an old man – and the old men of Ireland are a breed apart -- was patiently waiting.

“When will he be open?” John asked.

“He’d hardly be open now,” said the old man.

“Well, when will he be open?”

“Oh, he’ll be open in good time.”

I asked John what he meant by “in good time.”

It means, said John, that he didn’t have a clue, but he wouldn’t like to say something so bald and down-letting.

In Ireland, the facts are often delivered in fine gift-wrapping.

In a restaurant, my wife asked whether the fish was fresh. The waiter replied, “If it were any fresher, it would be swimming, and you wouldn’t want that now, would you?”

I spent two decades visiting Ireland as the American organizer of the Humbert Summer School in Ballina, County Mayo. Summer schools in Ireland are study groups that meet once a year and can focus on literature, like the Yeats school, or politics like the Parnell school. They are akin to Bill Clinton’s Renaissance weekends.

The Humbert Summer School, created by John Cooney, the eminent historian and journalist, and sadly no longer operating, was named for Gen. Jean Joseph Amable Humbert, who was sent by Napoleon to assist the Irish with the uprising against the English in 1798, remembered in The Year of the French, by Thomas Flanagan. The uprising failed, but Humbert became an Irish hero. (He fought gallantly in the Battle of New Orleans and ended his days in the city as French teacher.)

Our summer school examined the position of Ireland in the world, especially its role in Europe. Every year I would try and bring a few Americans to the northwest of Ireland to enjoy the discussions, the great lamb, salmon and potatoes, and, of course, the free flow of Guinness, Murphy’s (another stout), Smithwick’s (the dominant beer), and Bushmills and Jameson whiskeys, refreshments we found conducive to good talk.

That part of Ireland historically had been hard used by the English, from the time of William of Orange in the 17th Century to the Black and Tans in 1920, who were ill-trained and equipped English policemen, many teenagers, raised in England and inserted into the Royal Irish Constabulary, to oppose the Irish fight to overthrow English rule. They wore surplus green tunics and khaki trousers. Their conduct was brutal and thuggish.

I had told this dreadful history of English oppression in some detail to one of my American guests, Ray Connolly, who was from Boston. Driving back to Dublin, after the summer school session, we stopped at a pub. When the publican heard my English accent, he asked me about the weather “over there.” I knew that he meant England. I told him that I used to live in England, but I had lived in the United States for many years and had become an American citizen. Rather than curling his lip at me, he threw his arms around my neck and said, “God bless you. You haven’t lost your accent.”

My friend looked surprised. I explained to Ray that the Irish love to denounce the English, but they are especially proud when their children have homes and careers in London.

In Ireland, your enemy can also be your friend. That is why I shall wear the green on the great day and sip something stronger than usual and celebrate a Frenchman who fought with the Irish against my ancestors. Slainte!

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Boston negativity 'sucks'

Rick Pitino in a press conference for the 2013 Final Four when he was head coach at the University of Louisville

“The only thing we can do is work hard, and all the negativity that’s in this town {Boston) sucks.’’

— Rick Pitino (born 1952), basketball coach at colleges (including Providence College) and the NBA (including the New York Knicks and the Boston Celtics.

The Celtics hired him as head coach in 1997. He resigned in 2001, after a 102-146 record.

Contemplating climate change on Peaks Island

“Taking a Break” (video still), by Krystal Brown, in her show “15,000 Days’,’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, through March 28.

The gallery says Ms. Brown “contemplates climate change through the context of suspended time and death as a question rather than a finality. In this three-channel video installation, filmed November 2020 at Peaks Island, Maine, Brown utilizes conceptual motifs such as grave digging and specific costuming to speak to working-class labor, mostly the unseen work. Sound is an equally important component to the visuals of shoveled earth and a churning sea. The original poem, written by Brown, also titled “15,000 Days,’’ is performed by local Boston artist Kimberly Barnes. Experimental sound artist Adam Giangregorio provides minimalist drone music, recorded on-site at Battery Steele at Peaks Island. Through the lens of hauntology, Brown both pushes back against and concedes to an undetermined future.’’

Postcard from around 1900 showing the long-gone Gem Theater and the Peaks Island House hotel. Peaks Island is part of Portland. Its population rises from around 900 in the winter to several thousand in the summer because of people “from away” with summer houses there.