Everything will be....

“Ever Ok Ever’’ (acrylic over mixed media), by McKay Otto, in his show at Atelier Newport through Jan. 22.

The gallery says:

"McKay wants the viewer to have the feeling of not entering an artwork but a sanctum filled with ethereal light. McKay believes in the invisible , underlying reflections inherent in natural light like color and its reaction with light. McKay's work is abstract, drawn in part from the ordered universe and leaving any recognizable imagery - figures, landscapes, material world behind. Transparent-lucent acrylic canvas is his signature material, and painting and sculpture are his preferred gestures. McKay is as confident of his mastery of reflecting light to produce ethereal colors as he is his artistic vision and his ability to see the possibilities within light and beyond. McKay thinks of ways to work with the powerful forces waiting in the light just to be reflected. But the other side of this is the powerful ability to read the possibility inherent in the light and it's his intuitive sense to look at a material object and just know that there is an art work there ready to be transformed and transcend itself in his almost ephemeral state of mind necessary for achieving the unthinkable".

xxx

"Everyday I play with the light of the universe to find a way to a deeper dimension of reality in which all paths might ultimately converge."

- McKay Otto

Melissa Bailey: In Mass. and elsewhere, climate change hurts patients’ health

Mount Auburn Hospital's first building, the Parsons Building, built 1886. Patients had to be moved in the Cambridge hospital in 2019 because of a heat wave.

BOSTON

A 4-year-old girl was rushed to the emergency room three times in one week for asthma attacks.

An elderly man, who’d been holed up in a top-floor apartment with no air conditioning during a heat wave, showed up at a hospital with a temperature of 106 degrees.

A 27-year-old man arrived in the ER with trouble breathing ― and learned he had end-stage kidney disease, linked to his time as a sugar-cane farmer in the sweltering fields of El Salvador.

These patients, whose cases were recounted by doctors, all arrived at Boston-area hospitals in recent years. While the coronavirus pandemic is at the forefront of doctor-patient conversations these days, there’s another factor continuing to shape patients’ health: climate change.

Global warming is often associated with dramatic effects such as hurricanes, fires and floods, but patients’ health issues represent the subtler ways that climate change is showing up in the exam room, according to the physicians who treated them.

Dr. Renee Salas, an emergency physician at Massachusetts General Hospital, in Boston, said that she was working a night shift when the 4-year-old arrived the third time, struggling to breathe. The girl’s mother felt helpless that she couldn’t protect her daughter, whose condition was so severe that she had to be admitted to the hospital, Salas recalled.

She found time to talk with the patient’s mother about the larger factors at play: The girl’s asthma appeared to be triggered by a high pollen count that week. And pollen levels are rising in general because of higher levels of carbon dioxide, which she explained is linked to human-caused climate change.

Salas, a national expert on climate change and health, is a driving force behind an initiative to spur clinicians and hospitals to take a more active role in responding to climate change. The effort launched in Boston last February, and organizers aim to spread it to seven U.S. cities and Australia over the next year and a half.

Although there is scientific consensus on a mounting climate crisis, some people reject the idea that rising temperatures are linked to human activity. The controversy can make doctors hesitant to bring it up.

Even at the climate-change discussion in Boston, one panelist suggested the topic may be too political for the exam room. Dr. Nicholas Hill, head of the Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Division at Tufts Medical Center of Medicine, in Boston, recalled treating a “cute little old lady” in her 80s who likes Fox News, a favorite of climate-change doubters. With someone like her, talking about climate change may hurt the doctor-patient relationship, he suggested. “How far do you go in advocating with patients?”

Doctors and nurses are well suited to influence public opinion because the public considers them “trusted messengers,” said Dr. Aaron Bernstein, who co-organized the Boston event and co-directs the Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment at Harvard’s school of public health. People have confidence they will provide reliable information when they make highly personal and even life-or-death decisions.

Bernstein and others are urging clinicians to exert their influence by contacting elected officials, serving as expert witnesses, attending public protests and reducing their hospital’s carbon emissions. They’re also encouraging them to raise the topic with patients.

Dr. Mary Rice, a pulmonologist who researches air quality at Beth-Israel Deaconess Medical Center here, recognized that in a 20-minute clinic visit, doctors don’t have much time to spare.

But “I think we should be talking to our patients about this,” she said. “Just inserting that sentence, that one of the reasons your allergies are getting worse is that the allergy season is worse than it used to be, and that’s because of climate change.”

Salas, who has been a doctor for seven years, said she had little awareness of the topic until she heard climate change described as the “greatest public health emergency of our time” during a 2013 conference.

“I was dumbfounded about why I hadn’t heard of this, climate change harming health,” she said. “I clearly saw this is going to make my job harder” in emergency medicine.

Now, Salas said, she sees ample evidence of climate change in the exam room. After Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico, for instance, a woman seeking refuge in Boston showed up with a bag of empty pill bottles and thrust it at Salas, asking for refills, she recalled. The patient hadn’t had her medications replenished for weeks because of the storm, whose destructive power was likely intensified by climate change, according to scientists.

Climate change presents many threats across the country, Salas noted: Heat stress can exacerbate mental illness, prompt more aggression and violence, and hurt pregnancy outcomes. Air pollution worsens respiratory problems. High temperatures can weaken the effectiveness of medications such as albuterol inhalers and EpiPens.

The delivery of health care is also being disrupted. Disasters like Hurricane Maria have caused shortages in basic medical supplies. Last November, nearly 250 California hospitals lost power in planned outages to prevent wildfires. Natural disasters can interrupt the treatment of cancer, leading to earlier death.

Even a short heat wave can upend routine care: On a hot day in 2019, for instance, power failed at Mount Auburn Hospital, in Cambridge, Mass., and firefighters had to move patients down from the top floor because it was too hot, Salas said.

Other effects of climate change vary by region. Salas and others urged clinicians to look out for unexpected conditions, such as Lyme disease and West Nile virus, that are spreading to new territory as temperatures rise.

In California, where wildfires have become a fact of life, researchers are scrambling to document the ways smoke inhalation is affecting patients’ health, including higher rates of acute bronchitis, pneumonia, heart attacks, strokes, irregular heartbeats and premature births.

Researchers have shown that heavy exposure to wildfire smoke can change the DNA of immune cells, but they’re uncertain whether that will have a long-term impact, said Dr. Mary Prunicki, director of air pollution and health research at Stanford University’s center for allergy and asthma research.

“It causes a lot of anxiety,” Prunicki said. “Everyone feels helpless because we simply don’t know — we’re not able to give concrete facts back to the patient.”

In Denver, Dr. Jay Lemery, a professor of emergency medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, said he’s seeing how people with chronic illnesses like diabetes and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease suffer more with extreme heat.

There’s no medical code for “hottest day of the year,” Lemery said, “but we see it; it’s real. Those people are struggling in a way that they wouldn’t” because of climbing temperatures, he said. “Climate change right now is a threat multiplier — it makes bad things worse.”

Lemery and Prunicki are among the doctors planning to organize events in their respective regions to educate peers about climate-related threats to patients’ health, through the Climate Crisis and Clinical Practice Initiative, the effort launched in Boston in February.

“There are so many really brilliant, smart clinicians who have no clue” about the link between climate change and human health, said Lemery, who has also written a textbook and started a fellowship on the topic.

Salas said she sometimes hears pushback that climate change is too political for the exam room. But despite misleading information from the fossil fuel industry, she said, the science is clear. Based on the evidence, 97 percent of climate scientists agree that humans are causing global warming.

Salas said that, as she sat with the distraught mother of the 4-year-old girl with asthma in Boston, her decision to broach the topic was easy.

“Of course I have to talk to her about climate change,” Salas said, “because it’s impairing her ability to care for her daughter.”

Melissa Bailey is a reporter for Kaiser Health News.

Melissa Bailey: @mmbaily

All business in Brooklin

The moose, the state mammal, at the Maine State Museum, in Augusta

— Photo by Billy Hathorn

“There has been more talk about the weather around here this year than common, but there has been more weather to talk about. For about a month now we have had solid cold — firm, business-like cold that stalked in and took charge of the countryside as a brisk housewife might take charge of someone else’s kitchen in an emergency. Clean, hard, purposeful cold, unyielding and unremitting. Some days have been clear and cold, others have been stormy and cold. We have had cold with snow and cold without snow, windy cold and quiet cold, rough cold and indulgent peace-loving cold. But always cold.”

— E.B. White on his first full year at a his farm in Brooklin, on the Blue Hill Peninsula, on the Maine Coast. This essay appeared in his collection One Man’s Meat (1944). Winters tend to be milder and shorter now.

“In Deep Winter,’’ by Richard von Drasche-Wartinberg

‘Weather’s glamorous deceits’

“Wheat Stacks, Snow Effect,’’ by Claude Monet

“doesn’t need us, wants to be still…

not hurried into life

by the glamorous deceits

of a sudden thaw….’’

From “The Garden in Winter,’’ by Lawrence Raab (born 1946). He lives in Williamstown, Mass., in The Berkshires.

N.E. COVID update: Eli Lilly partners with UnitedHealth; ER visits in early pandemic

Encaustic painting by Nancy Whitcomb

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

BOSTON

”Eli Lilly & Company has partnered with UnitedHealth Group to develop promising new treatments for COVID-19. Researchers will study Eli Lilly’s new monoclonal antibody treatment for non-hospitalized patients who have recently contracted COVID-19. Read more here.

“Researchers at Harvard Medical School have published a study on the decline of emergency room visits in the early days of the pandemic. The investigators, working at Massachusetts General Hospital, raised raised concerns that critically ill patients were not seeking care because of fear of COVID-19 infection. Read more here.’’

Maternal mysteries

“Mother Courage” (onion skins, mixed media), by Marsha Nouritza Odabashian, at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, Jan. 8-31, in the “Heroes and Villains” show.

Manfred Wekwerth and Gisela May during rehearsals of Mother Courage and Her Children (1978). The play was written by the German playwright Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956), a Communist.

'Lost in fleeces'

—- Photo by Sean the Spook

It sifts from leaden sieves,

It powders all the wood,

It fills with alabaster wool

The wrinkles of the road.

It makes an even face

Of mountain and of plain, —

Unbroken forehead from the east

Unto the east again.

It reaches to the fence,

It wraps it, rail by rail,

Till it is lost in fleeces;

It flings a crystal veil

On stump and stack and stem, —

The summer’s empty room,

Acres of seams where harvests were,

Recordless, but for them.

It ruffles wrists of posts,

As ankles of a queen, —

Then stills its artisans like ghosts,

Denying they have been.

— By Emily Dickinson (1830-1886), of Amherst, Mass.

It might go up after all

The controversial Hope Point Tower

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I’m surprised to be saying this, but at this writing, it looks likely that a development group run by Jason Fane will build a $300 million, 46-story luxury residential lower, to be named Hope Point Tower, in Providence’s Route 195 relocation district. I’m surprised because I didn’t think that Mr. Fane would get the financing, especially when the pandemic makes downtown developments look like bad bets and Mr. Fane continues to face loud and well-organized opposition from some establishment groups.

Rhode Island Superior Court Judge Brian Stern recently okayed the project, ruling that the City Council was within its rights in approving it. Foes, including Mayor Jorge Elorza, will appeal to the state Supreme Court, but that seems very unlikely to succeed.

So what’s the economic rationale for continuing with this project in a time of pandemic and the deep recession it’s causing? I think it’s that even now, mid-size cities such as Providence with prestigious colleges and rich cities nearby -- in Providence’s case New York and Boston -- and in scenic areas, can look alluring. There would be stirring views from the upper stories of the Fane Tower, though, of course, its great height is what its foes would most hate about it – until, that is, they got used to it, if they ever do….

And COVID-19 has made big cities scary for many people, leading many affluent folks to seek to set up homes in less crowded places, even if they, too, are cities and even if some, like Providence, now have high COVID rates, too. And some of the units in the Fane tower would be bought or rented by the many very rich parents of students at Brown University and the Rhode Island School of Design. And the pandemic will end, sometime in 2021.

Then there’s the prospect of hundreds of construction jobs at the Fane Tower – a great allure for the state’s politically powerful construction unions.

So this huge project remains very much alive, as Mr. Fane looks to what Providence might look like after the pandemic.

Perhaps not a bad thing

Laffoley in his studio

“Boston is not an avant-garde place. It stays literally 15 to 20 years behind New York at all times.’’

— Paul Laffoley (1935- 2015), Boston architect and visionary artist

Work goes on after the storm

Southeastern New England’s first snowstorm of the month ended late in the day on Dec. 17, when the dramatic skies – looking like a 19th-Century Romantic landscape painting –announced a change in the weather. Life went on, as it always has during a New England winter. Two large ships were in Providence’s harbor: a tanker unloading oil to East Providence and the cranes on the other vessel being used to load something, perhaps scrap metal.

Photo and caption by William Morgan, a Providence-based writer and photographer. His latest book is Snowbound: Dwelling in Winter.

Chris Powell: America’s vacuous higher-ed credentialism steams on as we neglect lower ed

The main quad on the flagship campus of the University of Connecticut, in Storrs

MANCHESTER, Conn.

As was inscribed on the pedestal of the statue of college founder Emil Faber in the movie Animal House, "Knowledge is good." But knowledge can be overpriced, as the growing clamor about college student loan forgiveness soon may demonstrate.

President-elect Joe Biden and Democrats in the new Congress will propose various forms of forgiveness, and this will have the support of Connecticut's congressional delegation, all of whose members are Democrats.

Student-loan debt is huge, estimated at $1.6 trillion, and five Connecticut colleges were cited last week by the U.S. Education Department for leaving the parents of their students with especially high debt. There are many horror stories about borrowers who will never be able to pay what they owe.

But those horror stories are not typical. Most student-loan debt is owed by people who can afford to pay and are from families with higher incomes. Relief for certain debtors may be in order, but then what of the students who sacrificed along with their parents to pay their own way through college? What will they get for their conscientiousness? Only higher taxes and a devaluing currency.

Student-loan debt relief should not be resolved without an investigation of what the country has gotten for its explosion of spending on higher education. Has all the expense been worthwhile?

Probably not even close. A 2014 study by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York found that many college graduates end up in jobs that don't require college education. A similar study a year earlier by the Center for College Affordability and Productivity reported that there were 46 percent more college graduates in the U.S. workforce than there were jobs requiring a college degree and that degrees were held by 25 percent of sales clerks, 22 percent of customer-service representatives, 16 percent of telemarketers, 15 percent of taxi drivers and 14 percent of mail carriers.

Of course, that doesn't mean that college grads who went into less sophisticated jobs didn't enjoy college, learn useful things and increase their appreciation of life. But those who accrued burdensome debt only to find themselves in jobs that can't easily carry it may feel cheated.

Some consolation is that college grads tend to earn more over their lifetimes than other people. But is this because of increased knowledge and skills, or because of the credentialism that higher education has infected society with? If it is mere credentialism, college is a heavy tax on society.

Public education in Connecticut may be more credentialism than learning, since, on account of social promotion, one can get a high-school diploma here without having learned anything since kindergarten and can earn a degree from a public college without having learned much more, public college being to a great extent just remedial high school.

Some people in Connecticut advocate making public-college attendance free, at least for students from poor families. But even for those students would free public college be an incentive to perform well in high school once they discover that they need no academic qualification to get into a public college and that they can take remedial high-school courses there?

Even the student loans and government grants to higher education that underwrite important research and learning are largely subsidies to college educators and administrators, whose salary growth correlates closely with those loans and grants. Many college educators show their appreciation by resenting having to teach mere undergraduates instead of being left alone to do obscure research that has no relevance to curing cancer or averting the next asteroid strike. They prefer to strut around calling each other "Doctor" and "Professor" until the cows come home reciting Shakespeare.

Connecticut's critical neglect, and the country's, is lower education, not higher education, especially now that government is abdicating to the ever-grasping teacher unions by closing schools, where the threat of the virus epidemic is small. This suspends education, socialization, exercise and general growth for the young without protecting those most vulnerable to the virus, the frail elderly. Forgiving college loans won't be much more relevant to education than that crazy policy.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Llewellyn King: Electric cars would be a very minor matter for secretary running ‘the Little Pentagon’

The Brutalist Forrestal Building, headquarters of the U.S. Department of Energy, which has a very heavy portfolio of functions.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

President-elect Joe Biden’s decision to nominate Jennifer Granholm, former governor of Michigan, lawyer, politician and television host, to be the next secretary of energy is curious.

The idea circulating is that her primary assignment, in Biden’s mind, will be to speed Detroit’s development of electric vehicles.

That is hardly the job that Granholm will find confronting her when she heads to the 7th floor of the Forrestal Building, a bare-and-square, concrete structure across from the romantic Smithsonian Castle on Independence Avenue in Washington.

Secretary of energy is one of the most demanding assignments in the government. The Department of Energy is a vast archipelago of scientific, defense, diplomatic and cybersecurity responsibilities. Granholm’s biggest concern, in fact, won’t be energy but defense.

The DOE, nicknamed the Little Pentagon, is responsible for maintaining, upgrading and ensuring the working order of the nation’s nuclear weapons. A critical launch telephone will go with her everywhere. That is where much of the department’s $30 billion or so budget goes.

The energy secretary is responsible for the largest scientific organization on Earth: the 17 national laboratories operated by the department. They aren’t only responsible for the nuclear-weapons program, but also for a huge, disparate portfolio of scientific inquiry, from better materials to fill potholes to carbon capture, storage and utilization; and from small modular reactors for electricity to nuclear power for space exploration.

The national labs are vital in cybersecurity, particularly to assure the integrity of the electric grid and the security of things like Chinese-made transformers and other heavy equipment.

The DOE has the responsibility for detecting nuclear explosions abroad, measuring carbon in the atmosphere, making wind turbines more efficient, and developing the nuclear power plants that drive aircraft carriers and submarines. The department makes weapons materials, like tritium, and supervises the enrichment of uranium.

DOE scientists are looking into very nature of physical matter. They have worked on mapping the human genome and aided nano-engineering development.

Wise secretaries of energy have realized that not only are the national laboratories a tremendous national asset, but they can also be the secretary’s shock troops, ready to do what they are asked -- not always the way with career bureaucrats. Their directors are wired into congressional delegations, including California with Lawrence Livermore, Illinois with Argonne, New Mexico with Los Alamos and Sandia, Tennessee with Oak Ridge, South Carolina with Savannah River.

Verifying compliance with the START nuclear-weapons treaty with Russia falls to the DOE as will, possibly, renegotiating it. Another job would be being part of any future negotiations with Iran over their nuclear materials. Likewise, the energy secretary would be involved if serious negotiations are started with North Korea.

An ever-present headache for Granholm will be the long-term management of nuclear waste from the civilian program as public opposition to the Yucca Mountain site in Nevada is adamant. Also, she will be responsible for vast quantities of weapons-grade plutonium in various sites, but notably at the Pantex site, in Texas, and the Savannah River site in, South Carolina, before it is mixed with an inert substance for burial in Carlsbad, N.M.

Then there are such little things as the strategic petroleum reserve, the future of fracking, reducing methane emissions throughout the natural-gas system, and bringing on hydrogen as a utility and transportation fuel.

DOE has been charged with facilitating natural-gas and oil exports. Now those are subject to the objections of environmentalists.

Smart secretaries have built good relationships early with various Senate and House committees which have oversight of DOE.

James Schlesinger, the first secretary of energy, led the new department with a knowledge of energy from his time as chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, a knowledge of diplomatic nuclear strategy from his time as director of the CIA, and a knowledge of defense from his time as secretary of defense.

The only other star that has shone as brightly from the 7th floor of the Forrestal Building was President Obama’s energy secretary, Ernie Moniz, a nuclear scientist from MIT who essentially took over the nuclear negotiations with Iran: He and Iranian negotiator Ali Akbar Salehi, a fellow MIT graduate, hammered out the agreement, which was a work of art, a pas de deux, by two truly informed nuclear aficionados.

Compared to the awesome reach of the DOE in other vital areas, electric cars seem of little consequence, especially as Elon Musk with Tesla already has scaled that mountain, and all the car companies are scrambling up behind him.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Web site: whchronicle.com

'I'm a g-nu, how d'you do?'

“The Trojan Gnu” (steel, wood, acrylic paint and classical myth, reinterpreted), by Charles Gibbs at Alpers Fine Art, Andover, Mass.

“I'm a g-nu, I'm a g-nu,

The g-nicest work of g-nature in the zoo.

I'm a g-nu, how d'you do?

You really ought to k-now W-ho's W-ho!’’

— From “The Gnu Song,’’ by Flanders and Swann.

Maine mazes

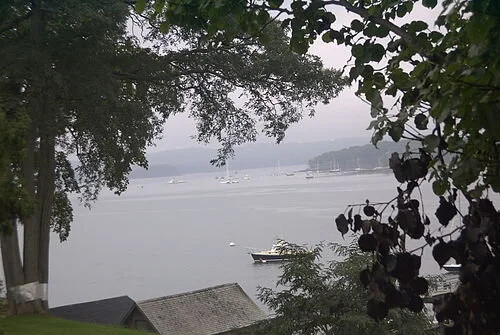

— Picture by Gossman75

View of the harbor in Castine, Maine, where Robert Lowell spent much time in the summer

“It was a Maine lobster town….

and below us the sea lapped

the raw little match-stick

mazes of a weir…

— From “Water,’’ by Robert Lowell (1917-1977)

Beware adulation of wealth

Portrait of John Hancock by the famed painter John Singleton Copley, c. 1770–1772

“Despise the glare of wealth. {P}eople who pay greater respect to a wealthy villain than to an honest, upright man in poverty almost deserve to be enslaved; they plainly show that wealth, however it may be acquired, is, in their esteem, to be preferred to virtue.’’

— John Hancock (1737-1793) was a very wealthy Boston merchant (mostly from maritime trade) and prominent patriot before, during and after the American Revolution. He was president of the Second Continental Congress and was the first and third governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. He is remembered for his large and stylish signature on the United States Declaration of Independence, so much so that the term "John Hancock" has become a synonym in the United States for one's signature.

Hancock's signature as it appears on the final copy of the Declaration of Independence

Hancock's memorial in Boston's Granary Burying Ground, dedicated in 1896.

URI creating computer models to assess how environmental change affects the ecosystem of Narragansett Bay

The Charles Blaskowitz Chart of Narragansett Bay published July 22, 1777 at Charing Cross, London

From ecoRI News

A team of scientists at the University of Rhode Island is creating a series of computer models of the food web of Narragansett Bay to simulate how the ecosystem will respond to changes in environmental conditions and human uses. The models will be used to predict how fish abundance will change as water temperatures rise, nutrient inputs vary, and fishing pressure fluctuates.

“A model like this allows you to test things and anticipate changes before they happen in the real ecosystem,” said Maggie Heinichen, a graduate student at the URI Graduate School of Oceanography. “You want to be able to prepare for changes that are likely to happen, so the model provides a starting point to ask questions and see what might happen if different actions are taken.”

Heinichen and fellow graduate student Annie Innes-Gold collaborated on the project with Jeremy Collie, a professor of oceanography, and Austin Humphries, an associate professor of fisheries. They used a wide variety of data collected about the abundance of marine organisms in Narragansett Bay, including life history information on nearly every species of fish that visits the area, and data about environmental conditions.

Their research was published in November in the journal Marine Ecology Progress Series. Additional co-authors on the paper are Corinne Truesdale at the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM) and former URI postdoctoral researcher Kelvin Gorospe.

“We built one model to represent the bay in the mid-1990s, the beginning point of the project,” Innes-Gold said, “and another one that represents the current state of the bay. That allowed us to predict how the biomass of fish in the bay would change from a historical point to the present day and see how accurate the model was in its predictions.”

The model correctly predicted whether each group of fish or fished invertebrates would increase or decrease.

The students are now expanding the model using various fishery management scenarios and expected temperature changes to assess its outcomes.

“What if there was no more fishing of a particular species, for instance, or double the fishing? How would that affect the rest of the ecosystem?” Innes-Gold asked. “I’m also incorporating a human behavior model to represent the recreational fishery in Narragansett Bay. I’ve run trials on whether unsuccessful fishing trips affect whether fishermen will come back to fish later, and how that affects the biomass of fish in the bay.”

Heinichen is incorporating the temperature tolerance of various fish species into the model, as well as other data related to how fish behave in warmer water.

“Metabolism rates and consumption rates increase as temperatures go up, and this affects the efficiency of energy transfer through the food web,” she said. “If a fish eats more because it’s warmer, that affects the total predation that another species is subjected to. And if metabolism increases as waters warm, more energy is used by the fish just existing rather than being available to turn it into growth or reproduction.”

In addition, an undergraduate at Brown University, Orly Mansbach, is using the model to see how fish biomass changes as aquaculture activity varies. If twice as many oysters are farmed, for example, how might that impact the rest of the ecosystem?

The URI graduate students said that the models are designed so they can be tweaked slightly with the addition of new data to enable users to answer almost any question posed about the Narragansett Bay food web. They have already met with DEM fisheries managers to discuss how the state agency might apply the model to questions it is investigating.

“We’re making the model open access, so if someone wants to use it for some question yet to be determined, they will have the model framework to use in their own way,” Heinichen said. “We don’t know all the questions everyone has, so we’ve made sure anyone who comes across the model can apply it to their own questions.”

The Narragansett Bay food web model is a project of the Rhode Island Consortium for Coastal Ecology, Assessment, Innovation and Modeling, which is funded by the National Science Foundation.

Thom Hartmann: Mitch McConnell wants to let companies kill you

Meat packing plants have had among the highest workplace infections from COVID-19.

Via OtherWords. org

Probably the most under-reported story of the year has been how Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R.-Ky.) is holding Americans hostage in exchange for letting big corporations kill Americans without any consequence.

Mitch took you and me hostage back in May, when the House passed the HEROES act that would have funded state and local governments and provided unemployed workers with an ongoing weekly payment.

Mitch refused to even allow the Senate to discuss the HEROES Act until or unless the legislation also legalized corporations killing their workers and customers. That is, McConnell wants to make it impossible to hold corporations legally accountable for COVID-19 infections caused by poor safety practices.

To this day, McConnell refuses to let the HEROES Act even be discussed in the Senate.

Meanwhile we’ve seen companies firing people for refusing to take their lives in their hands, executives organizing real-life betting pools on which employees are going to die first, and companies lying openly to their workers and customers about the dangers of COVID-19.

Mitch McConnell wants to protect them all. Even worse, his immunity can extend well beyond the pandemic and sets up a process that could put corporations above the law permanently, across every community in America, in ways that state and local governments can never defy.

While Republicans have fought against raising the minimum wage or letting workers unionize for over 100 years, what McConnell is doing now is giving corporations the ultimate right: the right to kill their employees and customers with impunity.

And McConnell’s holding your local police and fire departments, public schoolsand state health-care programs hostage in exchange for his corporate immunity.

This is beyond immoral. This is ghastly, and should have been at the top of every news story in America for the past six months. But many of the corporations that are looking forward to complete supremacy over their workers include the giant corporations that own our media.

America has suffered for over 40 years under Reaganism’s mantra, picked up from Milton Friedman, that when corporations focus exclusively on profit an “invisible hand” will guide them to do what’s best for people and communities. It’s a lie.

This is an assault on workers’ rights. But even greater, it’s a corporate assault on human rights. McConnell is saying that a corporation’s right to kill its workers and customers is more important than the lives of human beings.

As unemployment benefits are running out, evictions loom, small businesses are dying left and right, millions of families have been thrown into crisis, and more than 10 million Americans have lost their health insurance, McConnell continues to hold us all hostage.

It’s time to fight back. If corporate media continues to refuse to discuss McConnell’s blackmail, we must individually speak up among friends and communities, and also let our lawmakers know what we think. It’s time to raise some hell.

Thom Hartmann is a talk-show host and the author of The Hidden History of Monopolies: How Big Business Destroyed the American Dream. This op-ed was adapted from CommonDreams.org. He and his wife founded the New England Salem Children’s Village for abused children, in Rumney, N.H.

Related Posts:

OtherWords commentaries are free to re-publish in print and online — all it takes is a simple attribution to OtherWords.org. To get a roundup of our work each Wednesday, sign up for our free weekly newsletter here.

Thom Hartmann is a talk-show host and the author of The Hidden History of Monopolies: How Big Business Destroyed the American Dream. This op-ed was adapted from CommonDreams.org and distributed by OtherWords.org.

Except where otherwise noted, content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative 3.0 License.

Using waste to warn of waste

In Danielle O’Malley’s show “Sink or Swim,’’ at Boston Sculptors Gallery through Jan. 10.

The gallery says (here in slightly edited form) that the show “addresses the role of humans in the environmental crisis through a installation composed of hand-built earthenware and up-cycled waste materials collected throughout New England. Nautical buoys, traditionally used as warning beacons or navigational tools, become anthropomorphized industrial objects, warning the viewer about the perils of abuse of the natural world, as well as forcing awareness of their movements as they navigate through the installation. The marriage of these materials is a metaphor for the complexity of humanity’s role in the climate emergency, as well as the potential for society and nature to successfully collaborate and cohabitate. While acknowledging the gravity of the current situation, ‘Sink or Swim’ also offers hope. It is not too late for us to turn to sustainable lifestyles and let the earth to regain its health.’’

We can't to seem to find her balance

“I Live in a Balance of Hope & Fear,’’ by Pauline Lim, at the Brickbottom Artists Association, Somerville, Mass., through Jan. 16. She’s a painter and musician who lives in the Brickbottom facility.

The organization, named after the Somerville section whose clay deposits were used for brick making in the 19th Century, has become a well-known model for other artists' live/work developments around America.

‘‘I Live in a Balance of Hope & Fear,’’ by Pauline Lim, at the Brickbottom Art Association, Somerville, Mass.