'Black parabolas'

“When the mink ran across the meadow in bunched

black parabolas, I thought

sine and cosine, but no —

the movement never dips

below the line.’’

— From “The Mink,’’ by Rosanna Warren (born in 1953 in Fairfield, Conn.), the daughter of the late novelist, literary critic and U.S. poet laureate Robert Penn Warren and writer Eleanor Clark. She graduated from Yale University with a degree in painting.

Mink have staged a comeback in New England in recent decades.

Route 1, aka the Boston Post Road, in downtown Fairfield in 1953, when Ms. Warren was three. Route i was the main drag or the Northeast back then, before the Interstate Highway System.

.

Fidelity seeks to hire 500 new employees in N.H.

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

“Fidelity Investments has announced plans to hire 500 new employees for its Merrimack campus. The hiring is part of a company-wide initiative to add 4,000 new employees across the country.

“Fidelity has experienced a 24 percent increase in planning engagement activity as new investors open accounts, driving the need for more personnel at the company. Fidelity also plans to accept 1,000 college and university students into its 2021 internship program, as well as 500 graduates to participate in post-grad job training opportunities. Fidelity currently employs 5,300 in New Hampshire.

“‘We’re looking for financial advisers, licensed representatives, software engineers and customer service representatives to fill thousands of roles across the country over the next six months,’ said Kathleen Murphy, president of personal investing at Fidelity.’’

Read more from the New Hampshire Union Leader.

xxx

English colonists starting settling in Merrimack, named for a Native-American term for sturgeon, a once-plentiful fish in the area’s rivers, in the late 17th Century. For decades, the land was in dispute between the Province of New Hampshire and the Massachusetts Bay Colony. (Of course, both had seized the land from the Indians.)

The town had many farms into the 20th Century but has since become a place, with office parks, including for big corporations, and a bedroom community for commuters to Greater Boston and cities in southeastern New Hampshire.

The Souhegan River in Merrimack, also the name of the region’s biggest river.

The First Church of Christ in Merrimack.

Clamming in a golden place

Going clamming via the marshes of Barnstable,Mass.

— Photo by Elizabeth Whitcomb

— Elizabeth Whitcomb

— Photo by Justin Kaneps

That's that

“Fall Fell” (Sandwich, Mass.) (aluminarte print), by Bobby Baker. Copyright Bobby Baker Fine Art.

See:

https://bobbybaker.gallery/

Tough look at 1950s America

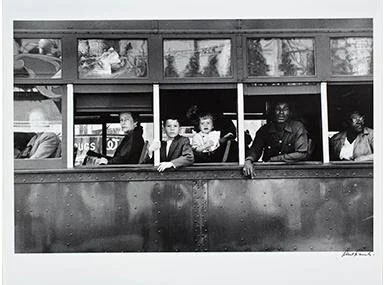

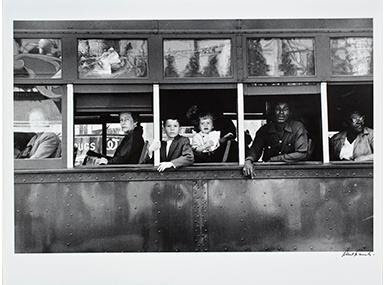

“Trolley—New Orleans ‘‘ (neg. 1955-1956, print 1989, gelatin silver print) , by the great Swiss-American photographer Robert Frank (1924-2019) as seen in his book The Americans.

A show — “Robert Frank: The Americans” — running until April 11 at the Addison Gallery of American Art, at Phillips Academy in Andover, Mass., displays a range of photographs from the famed book, providing an unflinching account of 1950s America. Note in this picture that the Blacks had to sit in the back in the still-segregated South.

The unusual Andover Town Hall.

A silvery lure

“An old silvery shed puzzles me with longing

And I free myself

By carefully slipping the reins from my shoulders

To follow:

But where? How can I move and keep the shed in view?’’

--From “The Shed,’’ by Henry Braun (1930-2014). After teaching literature and creative writing at Temple University, in Philadelphia, he retired to Weld, Maine, in interior western Maine, near the White Mountains, where he lived off the grid, as if in response to years of gritty city life.

Mt. Blue and Webb Lake, in Weld, Maine.

'Vast aspiration of man'

The spectacular main, Renaissance Revival facility of the Boston Public Library, on Copley Square, Boston. Designed by the famed architect Charles McKim, the building was opened in 1895. It faces another masterpiece: Henry Hobson Richardson’s Romanesque Trinity Church (see photo below), which was opened in 1877. The two help make Copley Square one of America’s most beautiful public places.

“For no matter how they might want to ignore it, there was an excellence about this city {Boston}, an air of reason, a feeling for beauty, a memory of something very good, and perhaps a reminiscence of the vast aspiration of man which could never entirely vanish.’’

— Arona McHugh (1924-1996), author of two novels set in Boston — The Seacoast of Bohemia and A Banner with a Strange Device.

Philip K. Howard: Principles to unify America

The Great Seal of the United States. The Latin means “Out of Many, One’’

“America is deeply divided”: That’s the post-mortem wisdom from this year’s election.

Surveys repeatedly show, however, that most Americans share the same core values and goals, such as responsibility, accountability and fairness. One issue that enjoys overwhelming popular support is the need to fix broken government. Two-thirds of Americans in a 2019 University of Chicago/AP poll agreed that government requires “major structural changes.”

President-elect Biden has a unique opportunity to bring Americans together by focusing on making government work better. Extremism is an understandable response to the almost perfect record of public failures in recent years. The botched response to COVID-19, and continued confusion over imposing a mask mandate, are just the latest symptoms of a bureaucratic megalith that can’t get out of its own way. Almost a third of the health-care dollar goes to red tape. The United States is 55th in World Bank rankings for ease of starting a business. The human toll of all this red tape is reflected in the epidemic of burnout in hospitals, schools, and government itself.

More than anything, Washington needs a spring cleaning. Officials and citizens must have room to ask: “What’s the right thing to do here?” If we want schools and hospitals to work, and for permits to be given in months instead of years, Americans at every level of responsibility must be liberated to use their common sense. Accountability, not suffocating legal dictates, should be our protection against bad choices.

But there’s a reason why neither party presented a reform vision: It can’t be done without cleaning out codes that are clogged with interest-group favors. Changing how government works is literally inconceivable to most political insiders. I remember the knowing smile of then-House Speaker John Boehner’s (R.-Ohio) when I suggested a special commission to clean out obsolete laws, such as the 1920 Jones Act, which, by forbidding foreign-flag ships from transporting goods between domestic ports, can double the cost of shipping. I also remember the matter-of-fact rejection by then-Rep. Rahm Emanuel (D.-Ill.) of pilot projects for expert health courts — supported by every legitimate health-care constituency, including AARP and patient groups — when he heard that the National Trial Lawyers opposed it: “But that’s where we get our funding.”

Cleaning the stables would help everyone, but the politics of incremental reform are insurmountable. That’s why, as with closing unnecessary defense bases, the only path to success is to appoint independent commissions to propose simplified structures. Then interest groups and the public at large can evaluate the overall benefits of the new frameworks.

Over the summer, 100 leading experts and citizens, including former governors and senators from both parties, launched a Campaign for Common Good calling for spring cleaning commissions. Instead of thousand-page rulebooks, the Campaign proposed that new codes abide by core governing principles, more like the Constitution, that honor the freedom of citizens and officials alike to use their common sense:

Six Principles to Make Government Work Again

Govern for Goals. Government must focus on results, not red tape. Simplify most law into legal principles that give officials and citizens the duty of meeting goals, and the flexibility to allow them to use their common sense.

Honor Human Responsibility. Nothing works unless a person makes it work. Bureaucracy fails because it suffocates human initiative with central dictates. Give us back the freedom to make a difference.

Everyone is Accountable. Accountability is the currency of a free society. Officials must be accountable for results. Unless there’s accountability all around, everyone will soon find themselves tangled in red tape.

Reboot Regulation. Too few government programs work as intended. Many are obsolete. Most squander public and private resources with bureaucratic micromanagement. Rebooting old programs will release vast resources for current needs such as the pandemic, infrastructure, climate change, and income stagnation.

Return Government to the People. Responsibility works for communities as well as individuals. Give localities and local organizations more ownership and control of social services, including, especially, for schools and issues such as homelessness.

Restore the Moral Basis of Public Choices. Public trust is essential to a healthy culture. This requires officials to adhere to basic moral values — especially truthfulness, the golden rule, and stewardship for the future. All laws, programs and rights mist be justified for the common good. No one should have rights superior to anyone else.

Is America divided? Many of the problems that caused people to take to the streets this year reflect the inability of officials to act on these principles. The cop involved in the killing of George Floyd should have been taken off the streets years ago — but union rules made accountability impossible. The delay in responding to COVID was caused in part by ridiculous red tape. The inability to build fire breaks on the west coast was caused by procedures that disempowered forestry officials.

The enemy is not each other, as President-elect Biden has repeatedly said. The enemy is the Washington status quo — a ruinously expensive and paralytic bureaucratic quicksand. Change is in the air. But the politics are impossible. That’s why one of first acts of President Biden should be to appoint spring cleaning commissions to propose new frameworks that will liberate Americans at all levels of responsibility to roll up their sleeves and make America work again.

American government needs big change, but the changes could hardly be less revolutionary. Instead of attacking each other, Americans need to unite around core values of responsibility and good sense.

Philip K. Howard is founder of Campaign for Common Good. His latest book is Try Common Sense. Follow him on Twitter: @PhilipKHoward.

Mr. Howard, a lawyer, is the founder and chairman of the nonprofit legal- and regulatory-reform organization Common Good (commongood.org), a New York City-based civic and cultural leader and a photographer. This piece first ran in The Hill.

What goes up....

“On The Rise” (oil), by Judith Brassard Brown, in her show “On the Rise and Fall,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, Dec. 90- Jan. 17. She teaches at the Montserrat College of Art, in Beverly, Mass.

See:

http://www.judithbrassardbrown.com/

and:

www.kingstongallery.com

'Winter is summer'

Headquarters of The Providence Journal, which is controlled by cost-slashing private-equity investors.

“There are ways to get rich: Find an old corporation,

self-insured, with capital reserves. Borrow

to buy: Then dehire managers; yellow-slip maintenance;

pay public relations to explain how winter is summer….’’

-- From “The One Day,’’ by New Hampshire poet Donald Hall (1928-2018)

'Silly waste of time'

Skiers practicing the “Christiania turn” (aka stem christie).

“By 1920, we had begun to use skis fairly consistently instead of snowshoes at Tolman Pond {in Nelson, N.H.}. A Norwegian family who visited at the farm introduced us to bindings that stayed put reasonably well, and to ski wax and proper poles, and soon we were exploring the magical mysteries of the Christiania turn…. But it was all strictly for fun and nobody dreamed a business might be made out of it. In fact the older generation did its best to discourage us from such a dangerous and silly waste of time.’’

-- Newton F. Tolman, in North of Monadnock (1957)

The Nelson Community Church, with the town’s famous mailbox shelter in front.

Nelson, founded in 1774, was originally named Packersfield, after a founder, Thomas Packer, the sheriff at Portsmouth. But the name was changed in 1814 to honor Viscount Horatio Nelson, British admiral and naval hero. This may seem strange, especially considering that the War of 12812 was underway. But many New Englanders opposed the war and Southern domination of the U.S. government and would have willingly accept a return to British rule.

Nelson, with four streams to provide power, developed into a prosperous small manufacturing town in the 19th Century, making cotton cloth and wooden chairs. That’s long gone and Nelson for many years has been a summer and weekend place. It has long lured writers, such as poet and memoirist May Sarton, and professional and amateur painters.

Sawmill in Nelson, 1914

William Morgan: Looking lithographically at proud 19th Century Maine

As part of its celebration of the 200th anniversary of Maine statehood, the Bowdoin College Museum of Art last winter held an exhibition of lithographs of 19th-Century town views in the Pine Tree State. Since then, the college and Brandeis University Press have published a handsome oversize book, Maine's Lithographic Landscapes: Town and City Views, 1830-1870.

What it says above:

“View of Portland, Me./Taken from Cape Elizabeth before the great conflagration of July 4th 1866

“Tinted lithograph from a photograph taken by Edward F. Smith and published by B.B. Russell & Co., Boston. 1866. ‘‘

The author is Maine State Historian Earle G. Shettleworth Jr., who was the state's historic-preservation officer for nearly five decades. The modest and scholarly Shettleworth may well know more about the state's architecture and other art than anyone else. Devoting his life to documenting everything Maine, he has written and lectured prodigiously on every aspect of Maine's built environment, and also written studies of female fly fisherman, photographers, painters, and parks.

“Augusta, Me., 1854.

Drawn by Franklin B. Ladd. Tinted lithograph by F. Heppenheimer, New York.’’

In a bit of Maine understatement, the co-director of the Bowdoin Museum, Frank H. Goodyear Jr., writes, "In Nineteenth Century America, the printed city view enjoyed wide popularity." As Shettleworth notes, the prints helped "forge the young state's identity” and served as "expressions of pride of place’’. During the period under review many towns and cities across America were memorialized in printed images drawn by artists famous and unknown.

Still, Maine was still a small state in the back of beyond. (its population was under 300,000 at the time it separated from Massachusetts, in 1820.) Thus, what the book’s creators call the "first comprehensive record of urban prints during the first fifty years of statehood" is somewhat limited: There are a total of 26 views of 11 places. Those are augmented by a score or more images of the often somber Bowdoin campus, including a painting, old photos, and two Wedgwood plates. Groundbreaking as the book is, viewing the exhibition itself would probably be more satisfying.

That said, Maine's Lithographic Landscapes is a handsome production. The Bowdoin Museum has a history of elegant catalogs, and this co-operative venture with Brandeis demonstrates that press's growing role as a publisher of New England studies. I am not sure that anyone looks at colophons (publisher’s emblems) anymore, so it is worth noting that the book was designed by the eminent book designer, Sara Eisenman.

Earle G. Shettleworth, Jr., Maine's Lithographic Landscapes, Brandeis University Press, 2020, 144 pages, $50.

William Morgan is a Providence-based architectural historian, photographer and essayist. His latest book is Snowbound: Dwelling in Winter.

Seeing red in 2020

“The Red Road” (acrylic on canvas), by Mark Chadbourne, in the show “RED 2020,’’ in the Cambridge (Mass.) Art Association’s Kathryn Schultz Gallery, through Dec. 17. The gallery has an annual show that is always titled BLUE or RED. RED can evoke happiness (your “red letter day”) and passion but it can also summon up intensity, including violence and pain, of which we’ve had plenty this year.

Chris Powell: Deconstructing COVID-19 hysteria

“Hysteria Patient,’’ by Andre Brouillet (1857-1914)

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Amid the growing panic fanned by news organizations about the rebound in the virus epidemic, last week's telling details were largely overlooked.

First, most of the recent "virus-associated" deaths in Connecticut again have been those of frail elderly people in nursing homes.

Second, while dozens of students at the University of Connecticut at Storrs recently were been found infected, most showed no symptoms and none died or was even hospitalized. Instead all were waiting it out or recovering in their rooms or apartments.

And third, the serious-case rate -- new virus deaths and hospitalizations as a percentage of new cases -- was running at about 2 percent, a mere third of the recent typical "positivity" rate of new virus tests, the almost meaningless detail that still gets most publicity.

Recognizing that deaths, hospitalizations, and hospital capacity should be the greatest concerns, Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont last week recalled that at the outset of the epidemic he had the Connecticut National Guard erect field hospitals around the state and that 1,700 additional beds quickly became available but were never used. This option remains available.

The governor's insight should compel reflection about state government's policy on hospitals -- policy that for nearly 50 years has been, like the policy of most other states, to prevent their increase and expansion.

The premise has been the fear that, as was said in the old movie, "if you build it, they will come" -- more patients, that is. The demand for medical services, the policy presumes, is infinite, and since government pays most medical costs directly or indirectly, services must be discreetly rationed -- that is, without public understanding -- even if this prevents economic competition among medical providers.

So in Connecticut and most other states you can't just build and open a hospital; state government must approve and confer a "certificate of need." Who determines need? State government, not people seeking care.

Of course, this policy was not adopted with epidemics in mind. Indeed, in adopting this policy government seems to have thought that epidemics were vanquished forever by the polio vaccines in the 1960s.

Now it may be realized that, while epidemics can be exaggerated, as the current one is, they have not been vanquished and the current epidemic -- or, rather, government's response to it -- has crippled the economy, probably in the amount of billions of dollars in Connecticut alone.

That cost should be weighed against the cost of hospitals that were never built. Maybe they could have been built and maintained only for emergency use, and an auxiliary medical staff maintained too, just as the National Guard is an all-purpose auxiliary.

Also worth questioning is the growing clamor for virus testing. The heightened desire for testing in advance of holiday travel is natural, but testing is not so reliable, full of false positives and negatives. Someone can test negative on Monday and on Tuesday can start manifesting the virus or contract it and be without symptoms.

Testing may be of limited use for alerting people that they might well isolate themselves for a time even if they are without symptoms. But people without symptoms are far less likely to spread the virus than infected people who don't feel well.

Only daily testing of everyone might be reliable enough to be very effective, but government and medicine are not equipped for that and it would be impractical anyway. Weekly testing of all students and teachers in school might be practical and worthwhile but terribly expensive, and only a few wealthy private schools are attempting it.

Contact tracing policy needs revision. Nothing has been more damaging and ridiculous than the closing of whole schools for a week or more because one student or teacher got sick or tested positive. As the governor notes, because of their low susceptibility to the virus, children may be safer in school than anywhere else.

Risk for teachers is higher but they also are more likely to become infected outside of school. They might accept the risk in school out of duty to their students, whose interrupted education is the catastrophe of the epidemic.

Meanwhile the country needs two vaccines -- one against the virus itself and one against virus hysteria.=

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.

To the pie and pudding

Over the river, and through the wood,

To Grandfather's house we go;

the horse knows the way to carry the sleigh

through the white and drifted snow.

Over the river, and through the wood,

to Grandfather's house away!

We would not stop for doll or top,

for 'tis Thanksgiving Day.

Over the river, and through the wood—

oh, how the wind does blow!

It stings the toes and bites the nose

as over the ground we go.

Over the river, and through the wood—

and straight through the barnyard gate,

We seem to go extremely slow,

it is so hard to wait!

Over the river, and through the wood—

When Grandmother sees us come,

She will say, "O, dear, the children are here,

bring a pie for everyone."

Over the river, and through the wood—

now Grandmother's cap I spy!

Hurrah for the fun! Is the pudding done?

Hurrah for the pumpkin pie!“The New-England Boy's Song about Thanksgiving Day” (1844), by Lydia Maria Child (1802-1880), writer, social reformer and human-rights promoter. She grew up in Medford, Mass., and the house referred to the grand one above, which had been souped up from the simpler structure she knew as a child. It’s now owned by Tufts University. The “river” is the Mystic River. Winter weather came earlier then.

The Mystic River around 1790.

Llewellyn King: Trust deficit endangers vaccine rollout

An anti-vaccination caricature by James Gillray, “The Cow-Pock—or—The Wonderful Effects of the New Inoculation!’’ (1802)

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

There is a trust deficit in this country, and it may kill a lot of us.

We haven’t been trusting for a long time, but distrust reached its zenith during and after the recent election. The election, still contested, brought with it a massive overhang of distrust. Indeed, the past four years have been marked by wide distrust.

Distrusting the election results isn’t fatal. But distrusting the experts on the need to get vaccinated for COVID-19 is. Yet there are reports that as many as 50 percent of Americans won’t get the vaccine when it is available. That is lethal and a true threat to national security, the economy, our way of life, everything.

If we don’t get our jabs, we will continue to die from coronavirus at an alarming rate. Over 258,000 Americans have perished and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention projects 298,000 deaths by mid-December.

As I recall, it was during the late 1960s that we began wide distrusting. By the end of the Vietnam War, we distrusted on a huge scale. We distrusted what we were told by the military, what we were told by President Lyndon Johnson and then by President Richard Nixon.

We also distrusted the experts. Just about all experts on all subjects, from nuclear-power safety to the environmental impact of the Concorde supersonic passenger jet.

Beyond Vietnam, distrust was fed by the unfolding evidence that we had been the victims of systemic lying. This led to big social realignments, as seen in the civil rights movement, the women’s movement, and the environmental movement. These betrayals exacerbated our natural American distrust of officialdom.

The establishment and its experts had been caught lying about the war and about other things. It was a decade that detonated trust, shredded belief in expertise, and left many of us feeling that we might as well make it up as we went along.

Now the trust deficit is back.

If LBJ and Nixon fueled distrust in the 1960s and early 1970s, the current breach of trust belongs to President Trump and his enablers scattered across the body politic, from presidential counselor Kellyanne Conway with her “alternative facts” to the Senate Republicans and their disinclination to check the president.

The trust deficit has divided us. Seventy-three million did vote for Trump and many of those believe what, most dangerously, he has said about the pandemic.

The result has been the growth of diabolical myths about COVID-19. Taking seriously some, or all, of Trump’s outpourings on the coronavirus -- from his advocacy of sunlight and his off-label drug recommendations, such as hydroxychloroquine, to putting the pandemic out of mind as a “hoax” -- fomented its spread.

We have been waiting for a medical breakthrough to repel and conquer COVID-19 and it looks as though that is at hand with the arrival of not one but three vaccines, the first of which should be available in about three weeks to the most vulnerable populations. The development of these vaccines represents a stupendous medical effort: the Manhattan Project of medicine.

But it will all be in vain if Americans don’t trust the authorities and don’t get vaccinated. It looks as though, according to surveys, 50 percent of the population will get vaccinated. The rest will choose to believe in such medical fictions as herd immunity — a pernicious idea that eventually we will all be immune by living with COVID-19. It should be noted that this didn’t happen with such other infectious diseases as bubonic plague, smallpox, polio, even the flu.

My informal survey of research doctors puts the odds on who will get vaccinated a little better than 50 percent. They conclude that one third will get vaccinated, one third will wait to see the results among those who got vaccinated early, and one third won’t get vaccinated, believing that the disease has been hyped and that it isn’t as serious as the often-castigated media says. Some of the “COVID-19 deniers” will be the permanent anti-vaxxers, people who think that vaccines have bad side effects; they believe, for example, that the MMR vaccine causes autism.

This medical heresy even as hospitals are filling to capacity, their staff are exhausted, and bodies are piling up in refrigerated trailers because there is nowhere to put them.

Without near-universal vaccination, the coronavirus will be around for years. The superhuman effort to get a vaccine will have been partially in vain. The silver bullet will be tarnished.

Get a grip, America. Get your jabs.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com. and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Before the anti-vaxxers: Administration of the polio inoculation, including by the first polio-vaccine developer, Jonas Salk, himself, in 1957 at the University of Pittsburgh, where his team had developed the vaccine.

In a postwar poster the Ministry of Health urged British residents to immunize children against diphtheria.

Karen Gross: Role-modeling by adults too often lacking in COVID-19 crisis

The Rev. John Jenkins, the president of the University of Notre Dame. Did he not wear a mask at a reception in order to suck up to Donald Trump?

BOSTON

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Sadly, the number of COVID-19 cases across the globe is rising. And while vaccines are in the offing, we may have many weeks between now and their availability, time in which more individuals can become infected and too many will die. In absolute terms, the numbers are staggering in the U.S. and around the world.

It is against this background that we should be concerned about super-spreader events. One category of such events includes college and high school students gathering and partying in ways that violate the COVID-19 protective measures (mask wearing, social distancing, avoiding large indoor get-togethers). Some of these problematic events occur off campus, others occur on campus. Wherever they happen, they have produced varying outcomes: quarantines; stoppage of athletic events; elimination of on-campus in-person learning (for a short or long period); changes in scheduling to eradicate vacations or campus departures; and students contracting COVID.

It is easy to blame students (whether in college or high school) and parents (in the context of high schoolers and even some college students who are now at home taking online classes). Can you hear adults within families and educational institutions saying: “How stupid can these young people be? They aren’t complying with the three simple rules.”

But the failure of compliance among young people must be contextualized. We are not living in “normal” times and behaviors need to be understood in light of the impact of the pandemic constraints as well as the age of students and their developmental stage.

Lack of physical connection, risk-taking, brain development

Start with this obvious observation: The wearing of masks, social distancing and school closures have left many young people without quality means of connecting. As much as they can use technology and we are certainly doing that (Zoom fatigue is a known phenomenon, as is online oversharing), there is something that youth are missing: real, hands-on human engagement. They are missing contact; they are missing touch. They are without smiles and hugs and physicality.

The absence of physical contact for an extended period (and what still seems like an indefinite period) is difficult and frustrating for young people. It makes them want to rebel against the constraints and ignore the accompanying risks that often are known to them. In short, students disobey COVID-19 rules because they have real needs for in-person connectivity that are unmet.

Brain science supports this conclusion: Most young people cannot fully control their behavior on their own and they discard the COVID-19 rules because of the stage of their brain development. Risk-taking is common among young people; it goes hand and hand with their psychosocial development. We know that young people underestimate risk: think about fast cars and drunk driving, texting while driving and physical challenges that seem likely to cause serious physical injury. Also, we know that quality judgment and decision-making do not occur until the mid to late 20s. (There are also upsides to this stage of development but that’s the subject of another article.)

Our expectation of strict compliance misses the biological reality of why students are disobeying. The parts of their brain that manage and measure risks are not fully developed. Youth are not trying to be disobedient (well, some are as a form of rebellion that is also age-appropriate). Many simply are not able to make quality decisions—at least not without adult intervention, and therein lie some answers as to what we can do to move toward greater compliance.

Two concrete examples

Before turning to solutions, let’s look at two actual scenarios that inform a pathway forward.

In late October, more than 20 high schoolers attended a party at a private home in Marblehead, Mass. Not only was there an absence of mask wearing, there was an absence of social distancing and there was shared drinking out of cups. The police were called. The students scattered. No one was prosecuted. The superintendent in a remarkably astute letter recognized student needs to connect, but then closed the high school as a precaution and decried that they can and must do better.

A few months earlier, Marist College, in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., suspended some students for participating in off-campus parties and later, when the non-compliance continued, had to shut down the campus physically. Before moving to online learning, the college president was quoted as saying: “Please don’t be a knucklehead who disregards the safety of others and puts our ability to remain on campus at risk.”

Pathways forward

We know that student risky behavior can be modified, and there are a variety of strategies that enable change. The problem is that we have not deployed them in the context of this pandemic for reasons that aren’t at all clear to me.

We would be wise to spend more time recognizing the psychological reasons for student behavior and, based on that science, create new strategies that mitigate the reasons noted above for non-compliance. And since the stage of student development also opens the door to creativity, why not use creativity as part of the solution?

Consider these approaches: Social-norming campaigns can show compliance or willingness to comply by many students to norms despite peer perceptions. Detailed discussions with students can lead to an understanding of the risks (based on science) to others and themselves with concrete examples and data points. Youth empathy engines can be activated such that students are engaged in doing activities that help others in their communities. These can be conducted by parents and educators alike. Consider a version of this “rock” project in Texas. Students could all get and paint rocks and then they and other students can place the rocks around school buildings or a college campus.

For the record, let’s eliminate one approach: student punishment and suspension as the first line of defense. We should be punishing when there is intent. Absent intent, we should not rush into suspending students. Yes, based on parties, we need to quarantine; yes, based on parties, we need to shut down campus residential life or in-person learning for a period of time. But calling people “knuckleheads” is not helpful.

Instead, let’s think about preemptive things that could be done to prevent the non-compliant risky behavior. We can do better, as the superintendent suggested, but we need to get ahead of the problem and not be reactive to it.

Role models

From my perspective, perhaps one of the best strategies for enabling students to shift behavioral patterns and avoid risky and unwise behavior is role modeling. We know that role modeling is critically important to youth. And role models can come from a variety of locations: family, older friends and peers, educators (including administrators and coaches), religious figures and community leaders. We also know that role models can be individuals whom students do not know personally: politicians, actors, athletes.

We know, too, that an antidote to trauma is a non-familial figure who knows you and genuinely cares about your well-being and believes in you. And we know that positive role models can and do counteract negative childhood and adult experiences. Our adults need to step it up—engage with one another and their children and peers in new ways.

Despite these truths, we aren’t doing a good job of role modeling locally or nationally. Consider the absence of good role modeling in the two concrete examples given earlier involving Marblehead and Marist and similar communities, schools and colleges.

With respect to Marblehead and similar communities where parties have occurred, I would ask (in a non-accusatory way): Where were the parents who lived in the home where the party was held? Were they home? Were they aware of the party in advance? Did they buy the items for the party? Where were the parents of the other students who attended the party? Did they know where their children were going that evening? What had the parents done in anticipation of the needs of their children to plan events that would be safe? What had the high school done in advance to recognize the need for students to engage but to construct initiatives that were safe for each student and the collective of students?

With respect to Marist and similar colleges, I would ask (again, in a non-accusatory way): Where were the student life personnel? Were they aware of particular off-campus sites that might present risks? What did they do in advance to provide for the engagement needs of students in safe ways? What messaging was coming from the administration in advance? And was the reference to the students as knuckleheads wise? By way of contrast, the superintendent in Marblehead overtly recognized the student need to engage in person in these difficult times, although for safety reasons, he closed in-person learning.

For me, Lesson One is that the institutions (both high school and postsecondary) and parents need to anticipate what activities could have meet student needs. And they should involve students in planning these events. There are a myriad of possibilities: art-installation projects; distant dancing; car get-togethers (remember “car hops?) with limited numbers in cars where students listen to live music or watch a movie together? What about wrapping all the trees in crepe paper to create a “Christo-esque” artwork and even, teaching about Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s amazing and startling work involving wrapping buildings and bridges and parks?

We can be creative in seeing what the needs are and then developing approaches that meet the needs.

Lesson Two is that the parents (of the party home) and the parents of other teenagers were not (it appears) actively aware of their own child’s behavior. Had they been, I think one can rightly ask whether they would have intervened. And we can rightly ask whether they themselves, in their engagement with others, were role modeling the needed protective behavior (masks, social distancing and outdoor events). Or perhaps they did not believe in the science and thus were noncompliant.

At the college level, I’d suggest there were staff who could have guessed where problems off-campus were likely, especially if they knew their students and had their ears to the ground. Even if this was not their role before and seems interventionist or paternalistic (maternalistic), that non-interference calculus has changed when there are abundant and growing health risks not just to students but to communities. Stated differently, why did staff not act on what they learned, knew and anticipated?

Both examples showcase the absence of role modeling by adults in terms of actual behavior and anticipatory thinking.

Negative role modeling is way too common right now

Apart from role modeling by parents and educators whom students know, we have had far too many examples of failed role modeling in ways that have received national attention. And, make no mistake about this, students are well aware when public figures fail to comply with the COVID mandates and rightly ask: If they can flaunt the rules, why can’t I?

Here are several well-known examples (and I am avoiding the obvious one of our current president) that demonstrate what students are seeing in the media day-in and day-out.

Start with the Dodgers Justin Turner’s behavior following his team winning the World Series. I get the excitement but having just tested positive, he went out onto the field maskless for at least some of the time. What message does that send to young people? When you win, the rules don’t apply even though the coach was among people who were immune-compromised? And then the player went unsanctioned by Major League Baseball as if the incident should just be forgotten as a lapse in a moment of glory and because the player issued an apology.

Turn then to Gavin Newsom, the governor of California, a state struggling with COVID outbreaks (among other disasters). It turns out that he attended a birthday party with more than 10 unrelated family members at an elite restaurant in Napa and wasn’t wearing a mask apparently. Top doctors attended, too. All of this was directly in contradiction to the mandates he was issuing to his constituencies.

But perhaps the most offensive examples come from college presidents. Think about it. If our educational leaders, who have a bully pulpit and are preaching compliance to their institutions, don’t comply, why would their students or students on other campuses? A prime example is Notre Dame’s president, the Rev. John Jenkins. He attended a ceremony in honor of the nomination of Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court. To be sure, for his institution, this was a big deal as the nominee was a professor at Notre Dame’s Law School. But please, no mask? No social distancing? Was he afraid that the president (of the U.S) would see a mask as a sign of disrespect? The photographs of the non-compliance are chilling.

Students were rightfully angry as were faculty. An apology isn’t enough in the context of the virus; words don’t stop disease spread, especially when you are so forcefully asking for campus compliance with COVID protections. And Father Jenkins got COVID.

Lesson Three is obvious: Hypocrisy doesn’t fly in the COVID-19 world. Public high-profile leaders need to role model compliance all the time; their messaging is seen and heard and it matters. Negative role modeling is catching.

Now what?

The contents of this article and the examples given and lessons proffered boil down to this: We need to ramp up positive role modeling. Role modeling isn’t a part-time activity. It is a full-time obligation.

To that end, parents and educators: 1) need to come up with strategies in advance that recognize that young people need ways to engage safely; 2) must involve students in the planning of these activities that are COVID-safe; 3) need to question where students are and anticipate their behavior by offering alternatives; 4) need to talk more to students about risks and about solutions and about feelings and double standards; and 5) shouldn’t make punishment the best solution as it doesn’t work; instead, provide alternatives.

These aren’t impossible solutions. They are doable if we focus on them. And we should, for the well-being of our young people, our families and our communities.

Karen Gross is former president of Southern Vermont College and a senior policy adviser to the U.S. Department of Education. She specializes in student success and trauma across the educational landscape. Her book, Trauma Doesn’t Stop at the School Door: Solutions and Strategies for Educators, PreK-College, was released in June 2020 by Columbia Teachers College Press.

Chris Powell: Beware 'regulatory capture' of appointees to Cabinet

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Many teachers around the country are cheering the forthcoming change in national administration because Betsy DeVos will be replaced as secretary of education. DeVos, an heiress and philanthropist, has been a fan of charter schools and a foe of political correctness. While not really expert in pedagogy, at least she has not been the usual tool of teacher unions.

But President-elect Joe Biden is encouraging teachers to expect Nirvana. Addressing them the other week, Biden noted that his wife, Jill, is a community college teacher, and so "you're going to have one of your own in the White House." Presumably that means that teachers will have "one of their own" at the Education Department as well.

Among those mentioned is U.S. Rep. Jahana Hayes, the former Waterbury teacher and 2016 national teacher of the year, a Democrat who was just elected to her second term in Connecticut's 5th Congressional District.

Apart from her classroom work, Hayes has no managerial experience and her first term in Congress was unremarkable. Her recent campaign's television commercials celebrated her merely for listening to her constituents. While she won comfortably enough in a competitive district in a Democratic year, her departure for the Cabinet would prompt a special election that the Democrats might lose even as they already are distressed by the unexpected shrinkage of their majority in the U.S. House.

But then the U.S. Education Department does little to improve education. Mainly it distributes federal money to state and municipal governments, which do the actual educating. No matter who becomes education secretary, money will still get distributed and education won't improve much if at all.

Quite apart from the personalities, the big issue about the appointment of an education secretary is the big issue with other federal department heads. Why should the public cheer the appointment of an education secretary who is part of the interest group he would be regulating, any more than the public should cheer another Treasury secretary coming from a Wall Street investment bank, another labor secretary coming from a labor union, another defense secretary coming from the military or a military contractor, another agriculture secretary coming from agribusiness, and so yforth?

This kind of thing is called "regulatory capture" and it operates under both parties, though some special interests do better under one party than the other, as the cheering from the teacher unions indicates.

xxx

The virus epidemic has invited a comprehensive reconsideration of education but no one in authority has noticed.

Every day brings a change of plan and schedule in Connecticut schools. One day they're open and the next day they are abruptly converted to "remote learning" for a few days, a week or two, or a whole semester because somebody came down with the flu.

Amid all this many students have simply disappeared. Additionally, since education includes not just book learning but the socialization of children, their learning how to behave with others, the education of all children is being badly compromised.

Gov. Ned Lamont wants to leave school scheduling to schools themselves. This lets him avoid responsibility for any school's policy. But local option isn't producing much education.

The hard choice everyone is trying to avoid is between keeping schools open as normal, taking the risk of more virus infections because children are less susceptible to serious cases, or converting entirely to internet schooling and thereby forfeiting education for the missing students and socialization for everyone else.

If social contact can be forfeited, the expense of education can be drastically reduced. The curriculum for each grade can be standardized, recorded, and placed on the internet, with students connecting from home at any time, not just during regular school hours. Tests to evaluate their learning can be standardized too and administered and graded by computer. A corps of teachers can operate a help desk via internet, telephone, or email.

Much would be lost but then much already had been lost even before the epidemic, since social promotion was already the state's main education policy. Maybe the results of completely remote schooling would not be so different from those of social promotion.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.