Those screaming invaders

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

“It’s time to ban leaf blowers. The decibel level is a health hazard. Raking works.’’

Bravo to Richard Goldberg for posting this observation on the Next Door site.

See:

https://nextdoor.com/news_feed/?

For weeks every fall, and then again in the spring, affluent homeowners hire yard crews with screaming, gasoline-powered leaf blowers to make life utterly miserable for their human neighbors, as well as other animal life in the area, for hours a day. These infernal devices also emit copious quantities of air pollution. They’re a menace to health and should have been banned long ago. With so many people now forced to work at home, they’re hurting the health of many more people than ever. (Electric leaf blowers are quieter and don’t emit pollution.)

And we notice that the ears and lungs of many of the workers wielding these monsters aren’t protected. More than a few seem to be illegal aliens, who lack workplace protections. They don’t dare complain.

Hit this link to read a discussion in Newton, Mass., on the general public-health awfulness of gasoline-powered leaf blowers.

Yes, indeed, it’s time to ban gasoline-powered leaf blowers, at least in residential neighborhoods.

Charlotte Huff: In COVID crisis, 'unattended moral injury' to health-care workers

St. Vincent Hospital in Worcester

For Christina Nester, the pandemic lull in Massachusetts lasted about three months through summer into early fall. In late June, St. Vincent Hospital had resumed elective surgeries, and the unit the 48-year-old nurse works on switched back from taking care of only COVID-19 patients to its pre-pandemic roster of patients recovering from gallbladder operations, mastectomies and other surgeries.

That is, until October, when patients with coronavirus infections began to reappear on the unit and, with them, the fear of many more to come. “It’s paralyzing, I’m not going to lie,” said Nester, who’s worked at the Worcester hospital for nearly two decades. “My little clan of nurses that I work with, we panicked when it started to uptick here.”

Adding to that stress is that nurses are caught betwixt caring for the bedside needs of their patients and implementing policies set by others, such as physician-ordered treatment plans and strict hospital rules to ward off the coronavirus. The push-pull of those forces, amid a fight against a deadly disease, is straining this vital backbone of health providers nationwide, and that could accumulate to unsustainable levels if the virus’s surge is not contained this winter, advocates and researchers warn.

Nurses spend the most sustained time with a patient of any clinician, and these days patients are often very fearful and isolated, said Cynda Rushton, a registered nurse and bioethicist at Johns Hopkins University, in Baltimore.

“They have become, in some ways, a kind of emotional surrogate for family members who can’t be there, to support and advise and offer a human touch,” Rushton said. “They have witnessed incredible amounts of suffering and death. That, I think, also weighs really heavily on nurses.”

A study published this fall in the journal General Hospital Psychiatry found that 64 percent of clinicians working as nurses, nurse practitioners or physician assistants at a New York City hospital screened positively for acute distress, 53 percent for depressive symptoms and 40 percent for anxiety — all higher rates than found among physicians screened.

Researchers are concerned that nurses working in a rapidly changing crisis like the pandemic — with problems ranging from staff shortages that curtail their time with patients to enforcing visitation policies that upset families — can develop a psychological response called “moral injury.” That injury occurs, they say, when nurses feel stymied by their inability to provide the level of care they believe patients require.

Dr. Wendy Dean, co-founder of Moral Injury of Healthcare, a nonprofit organization based in Carlisle, Pa., said, “Probably the biggest driver of burnout is unrecognized unattended moral injury.”

In parts of the country over the summer, nurses got some mental-health respite when cases declined, Dean said.

“Not enough to really process it all,” she said. “I think that’s a process that will take several years. And it’s probably going to be extended because the pandemic itself is extended.”

Before the pandemic hit her Massachusetts hospital “like a forest fire” in March, Nester had rarely seen a patient die, other than someone in the final days of a disease like cancer.

Suddenly she was involved with frequent transfers of patients to the intensive-care unit when they couldn’t breathe. She recounts stories, imprinted on her memory: The woman in her 80s who didn’t even seem ill on the day she was hospitalized, who Nester helped transport to the morgue less than a week later. The husband and wife who were sick in the intensive care unit, while the adult daughter fought the virus on Nester’s unit.

“Then both parents died, and the daughter died,” Nester said. “There’s not really words for it.”

During these gut-wrenching shifts, nurses can sometimes become separated from their emotional support system — one another, said Rushton, who has written a book about preventing moral injury among health- care providers. To better handle the influx, some nurses who typically work in noncritical care areas have been moved to care for seriously ill patients. That forces them to not only adjust to a new type of nursing, but also disrupts an often-well-honed working rhythm and camaraderie with their regular nursing co-workers, she said.

At St. Vincent Hospital, the nurses on Nester’s unit were told one March day that the primarily post-surgical unit was being converted to a COVID unit. Nester tried to squelch fears for her own safety while comforting her COVID-19 patients, who were often elderly, terrified and sometimes hard of hearing, making it difficult to communicate through layers of masks.

“You’re trying to yell through all of these barriers and try to show them with your eyes that you’re here and you’re not going to leave them and will take care of them,” she said. “But yet you’re panicking inside completely that you’re going to get this disease and you’re going to be the one in the bed or a family member that you love, take it home to them.”

When asked if hospital leaders had seen signs of strain among the nursing staff or were concerned about their resilience headed into the winter months, a St. Vincent spokesperson wrote in a brief statement that during the pandemic “we have prioritized the safety and well-being of our staff, and we remain focused on that.”

Nationally, the viral risk to clinicians has been well documented. From March 1 through May 31, 6 percent of adults hospitalized were health-care workers, one-third of them in nursing-related occupations, according to data published last month by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

As cases mount in the winter months, moral injury researcher Dean said, “nurses are going to do the calculation and say, ‘This risk isn’t worth it.’”

Juliano Innocenti, a traveling nurse working in the San Francisco area, decided to take off for a few months and will focus on wrapping up his nurse practitioner degree instead. Since April, he’s been seeing a therapist “to navigate my powerlessness in all of this.”

Innocenti, 41, has not been on the front lines in a hospital battling COVID-19, but he still feels the stress because he has been treating the public at an outpatient dialysis clinic and a psychiatric hospital and seen administrative problems generated by the crisis. He pointed to issues such as inadequate personal protective equipment.

Innocenti said he was concerned about “the lack of planning and just blatant disregard for the basic safety of patients and staff.” Profit motives too often drive decisions, he suggested. “That’s what I’m taking a break from.”

Building Resiliency

As cases surge again, hospital leaders need to think bigger than employee-assistance programs to backstop their already depleted ranks of nurses, Dean said. Along with plenty of protective equipment, that includes helping them with everything from groceries to transportation, she said. Overstaff a bit, she suggested, so nurses can take a day off when they hit an emotional cliff.

The American Nurses Association, the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN) and several other nursing groups have compiled online resources with links to mental health programs as well as tips for getting through each pandemic workday.

Kiersten Henry, an AACN board member and nurse practitioner in the intensive care unit at MedStar Montgomery Medical Center, in Olney, Md., said that the nurses and other clinicians there have started to gather for a quick huddle at the end of difficult shifts. Along with talking about what happened, they share several good things that also occurred that day.

“It doesn’t mean that you’re not taking it home with you,” Henry said, “but you’re actually verbally processing it to your peers.”

When cases reached their highest point of the spring in Massachusetts, Nester said there were some days she didn’t want to return.

“But you know that your friends are there,” she said. “And the only ones that really truly understand what’s going on are your co-workers. How can you leave them?”

Charlotte Huff is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Socially distanced sculpture

“Big C” (aluminum bar 0.5" x 2", Ultrex fibers (polythylene), by Robert Osborne, in the “11th Annual Flying Horse Outdoor Sculpture Exhibit: Art at a (Social Distance)”, at the Pingree School, South Hamilton, Mass, through Nov. 29.

This exhibit takes place across the school’s 100-acre campus every fall, and this year is no exception, despite COVID-19. The 50 sculptures in the show are spread throughout the campus at least 10 feet apart from one another to ensure visitor safety.

The Pingree School, in South Hamilton, Mass., on the North Shore of Greater Boston. In 1961, the private co-ed high school was founded by Sumner Pingree and his wife, Mary Pingree, in this mansion on the estate where they had raised their three sons. A lot of their money came from agricultural and other investments in Cuba. But the Cuban government seized their land holdings after Fidel Castro’s Communists took over.

Roger Warburton: Ocean damage increases in CO2 buildup as climate warms

January sea surface temperatures off southern New England have risen significantly since 1980.

— Roger Warburton/ecoRI News

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Living in Rhode Island, we are aware how the ocean rules our weather. What is less well known is that climate change is fundamentally altering the waters off our coast.

The image above shows how the January temperature of the ocean off New England has changed since 1980. For example, vast areas of dark blue — representing temperatures around 41-43 degrees Fahrenheit — have shrunk and are now a lighter blue, representing temperatures around 43-45 degrees.

The effects of a temperature rise in the ocean are significantly different from a temperature rise over land. We experience this difference when we walk across a sandy beach on a hot day. Exposed to the same sunlight, the sand burns our feet while the ocean warms gradually to the perfect temperature for a summer swim.

Rhode Island’s climate is moderated because the ocean takes longer than the land to heat up over the summer and longer to cool down during the fall.

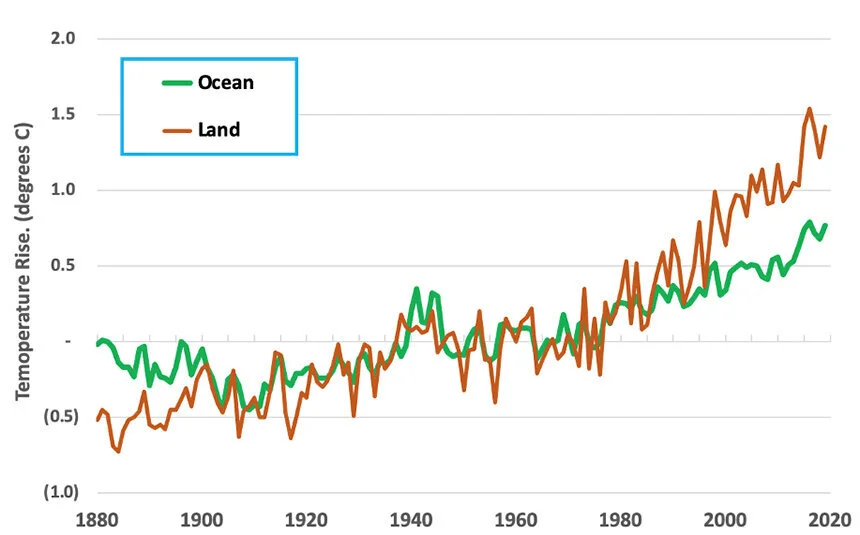

The global impact of this effect is shown in the image below, which shows that, over recent decades, the continents have warmed much more rapidly than the oceans. The Earth’s land areas were 1.4 degrees Celsius (2.5 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than the 20th-Century average, while the oceans were 0.8 degrees Celsius (1.4 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer.

Since 1880, the Earth’s land temperature has risen faster than the ocean temperature. “

— Roger Warburton/ecoRI News

Unfortunately, the ocean’s smaller temperature rise isn’t good news, because the oceans can store more than four times as much heat as the land.

Even though ocean temperatures have risen less than the land’s, it’s becoming clear that the impacts of climate change depend on a complex interaction between dry land and the warming ocean.

Ships and buoys have been recording sea surface temperatures for more than a century. International cooperation and sharing of data between nations has created a global database of sea surface temperatures going back to the middle of the 19th century.

In addition, modern satellites remotely measure many ocean characteristics over the entire extent of the Earth’s oceans. The data are now so accurate that it’s possible to detect the small temperature rise from ships’ propellers as they traverse the oceans.

The warming of both the land and the oceans is caused by rising levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide. When CO2 dissolves in the ocean, it forms carbonic acid, which in turn, breaks into hydrogen and bicarbonate ions. Clams, mussels, crabs, corals and other sea life rely on those carbonate ions to grow their shells.

In 2015, Mark Gibson, deputy chief of marine fisheries at the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management, noted that ocean acidification is a “significant threat” to local fisheries.

In fact, a study published in 2015 found that the Ocean State’s shellfish populations are among the most vulnerable in the United States to the impacts of acidification.

In polar regions such as Alaska, the ocean water is relatively cold and can take up more CO2 than warmer tropical waters. As a result, polar waters are generally acidifying faster than those in other latitudes.

The water in warmer regions can’t hold as much CO2 and are releasing it into the atmosphere. Therefore, the acidification from carbon dioxide is damaging the oceans in both polar and equatorial regions.

Warming oceans are also changing the winds that whip up the ocean, resulting in upwells from deep waters that are nutrient-rich but also more acidic.

Normally, this infusion of nutrient-rich, cool, and acidic waters into the upper layers is beneficial to coastal ecosystems. But in regions with acidifying waters, the infusion of cooler deep waters amplifies the existing acidification.

In the tropics, rising temperatures are slowing down winds and reducing the exchange of carbon between deep waters and surface waters. As a result, tropical waters are becoming increasingly stratified and more saturated with carbon dioxide. Lower layers then have less oxygen, a process known as deoxygenation.

Warming ocean temperatures have also caused a rapid increase of toxic algal blooms. Toxic algae produce domoic acid, a dangerous neurotoxin, that builds up in the bodies of shellfish and poses a risk to human health.

In coastal areas, such as Rhode Island, temperature changes can favor one organism over another, causing populations of one species of bacteria, algae, or fish to thrive and others to decline.

The sum of all these impacts is damaging to the Rhode Island economy. The state’s shellfish populations are already among the most vulnerable in the United States to the impacts of a warmer ocean.

Roger Warburton, Ph.D., is an ecoRI News contributor and a Newport resident. He can be reached at rdh.warburton@gmail.com.

Figure 1 was generated using data from the Copernicus Climate Change and Atmosphere Monitoring Services (2020). The ERA5 dataset is produced by the European Space Agency SST Climate Change Initiative based on global daily sea surface temperature data from the Group for High Resolution Sea Surface Temperature and made available by the Copernicus Climate Data Store.

Figure 2 was generated using data from NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental information, Climate at a Glance: Global Time Series.

A loving meal

Emeril Lagasse

“Anything made with love, bam! It’s a beautiful meal.’’

—Emeril Lagasse (born 1959), internationally known chef, TV host and restaurant entrepreneur. Born and raised in Fall River, his first big job was as executive chef of Dunfey’s Hyannis (Mass.) Resort, on Cape Cod.

David Warsh: Digital regulation is coming, sooner or later

Visualization of Internet routing paths.

—Graphic by The Opte Project

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

There are two ways of thinking about political prospects for the years ahead. One is to dwell on the relatively narrow margins of the recent presidential election – 80 million vs. 74 million votes cast, 306-232 in the Electoral College – and fear gridlock. The other is to look at America’s history of dealing with its problems and expect a series of further adjustments to be made, patterned on what’s been done before.

Take the problem of industrial concentration.

The government’s last big antitrust action came at the very dawn of the digital age: an unlawful monopolization charge under the Sherman Antitrust Act in the aftermath of the browser wars for having “smothered” a rival start-up, Netscape. The government won the case; and federal Judge Thomas Penfield Jackson ordered that Microsoft be split in two, one company selling operating systems, the other applications. The D.C. Court of Appeals overturned Jackson’s rulings and accused him of unethical conduct. The George W. Bush administration’s Justice Department announced that it would no longer seek to break up the company.

What has changed since then? Plenty. The shares of five large companies – Apple, Google, Microsoft, Facebook and Amazon make up nearly a quarter of the S&P 500 index, as EconoFact noted last week, in the course of surveying the legal landscape. The Justice Department and 11 states have sued Google, charging the company with abuse of its power.

The belief is growing that, whatever the conveniences of the Internet giants, there’s something about the structure of digital markets that means that they cannot be expected to self-correct. The most thoughtful proposal for government intervention I’ve seen is one prepared for a Report on Digital Platforms, commissioned by the Stigler Center for the Study of the Economy and the State at the University of Chicago’s Graduate School of Business.

There’s justice in this, it should be said. George Stigler was a pillar of the third Chicago School (1945–2014), a Nobel laureate, known for his decades-long rear-guard action against 20th Century ideas about market power. “It is virtually impossible to eliminate competition in economic life,” he wrote in his autobiography. Stigler died in 1991, the same year that the Internet was commercialized.

Fiona Scott Morton, of Yale University, chaired the study’s antitrust subcommittee. She served as Deputy Assistant Secretary for Economics in the Antitrust Division of the Justice Department in the Obama Administration.

At a conference in Chicago last year, Scott Morton presented the subcommittee’s 90-page findings in short, to-the-point remarks. Digital markets are quite different from most goods markets, she said. They are two-sided markets, serving at least two distinct user groups (readers or listeners and advertisers, for example), providing network effects to each. Economies of scale, of scope, and increasing returns to the possession of user data mean that such markets often “tip” at a certain point. The less successful drop out or are acquired and the winner takes all. Competition thus is often only for the market, not in it, Scott Morton said.

Three panelists discussed the report. Activist Matt Stoller, proprietor of the antitrust Web site Big, described a “world on fire,” and complained the recommendations lacked urgency. Ariel Eztrachi, of Oxford University, a member of the subcommittee, agreed. “No action is no longer an option. If we play for too long, we might find ourselves in a very different reality.” But Randal Picker, of the University of Chicago Law School, offered a jolt of the old-time religion.

When I took price theory from Gary Becker many years ago, Gary made clear that I needed to know two things to do economics. People optimize subject to constraints, and markets clear. That was all I really needed to know, and if I confronted a problem and thought I needed something more than that, I probably wasn’t thinking hard enough.

The subcommittee proposed two policy measures. A specialist competition court should be established to hear all private and public antitrust cases. That would allow judges to develop expertise in an area in which both behavioral and organizational economics have changed a great deal in the last 30 years.

A regulatory agency, a digital authority, should be created as well. Antitrust works well when agencies are quick to act and courts enforce the law well, said Scott Morton. “But even in the best world that’s not a complete solution. You need a partner to create a competitive environment.”

New technologies have traditionally brought into existence new regulatory agencies to help structure the new markets they created. The Interstate Commerce Commission was established to deal with the railroads (and later trucking). The Federal Communications Commission followed the radio industry into existence, and later came to oversee all kinds of communication. The Securities and Exchange Commission arrived not long after chicanery in the 1920s marred the beginnings of the democratization of finance.

Why not, then, enact a Digital Competition Commission, to provide a foil to the still-robust Sherman Antitrust Act? A new era of trust-busting may be in the offing. Digital regulation is coming, sooner or later, the subcommittee was saying. Why not start now?

David Warsh, an economic historian and a veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first appeared.

An all-accepting friend

—Photo by Lisa Sympson

A fluffy fellow in my lap

Continually purrs --

You may have heard him -- did you not

His purring joyful is --

He cares not if I'm rich or poor --

Or if I'm fat or slim --

Or if I’m tidy or unkempt --

Why can’t you be like him?

— Felicia Nimue Ackerman

This poem first appeared in The Emily Dickinson International Society Bulletin and is reprinted with permission.

“The Cat's Lunch ‘‘ (oil on canvas), by Marguerite Gérard (19th Century)

Ah, that skin-soothing lobster ‘blood’

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

“Two graduates of the University of Maine (UMaine) have developed a skin cream derived from lobster hemolymph, which functions within the lobster similarly to blood. The product can sooth such ailments as psoriasis and eczema.

“The product is the latest addition to items that can be traced back to efforts by the University of Maine (UMaine) to find commercial applications for byproducts of the commercial lobster industry. UMaine has worked for years to find additional uses for shells and other byproducts. Marin Skincare was founded by CEO Patrick Breeding and co-founder Amber Boutiette, who learned about the potential for lobster by-products while earning their master’s degrees at UMaine.

“Breeding and Boutiette are currently working with Luke’s Lobster in Saco, Maine, to collect hemolymph. The product has been available to consumers for over a month.

“The New England Council applauds UMaine for providing an innovative course of study encourage such scientific discoveries. Read more from the Bangor Daily News.’’

Jim Hightower: Turkey and Thanksgiving confusions

“The First Thanksgiving at Plymouth “ (1914), by Jennie Augusta Brownscombe, at the Pilgrim Hall Museum, Plymouth, Mass. If they ate turkeys, they would have been members of the Eastern Wild Turkey subspecies seen below.

Via OtherWords.org

Let’s talk about turkey!

No, not the Butterball now pouting in the Oval Office. I’m talking about the real thing — the big bird, 46 million of which Americans will devour on Thanksgiving.

It was the Aztecs who first domesticated the gallopavo, but leave it to the Spanish conquistadores to “foul-up” the bird’s origins.

The Spanish declared the turkey to be related to the peacock — wrong! They also thought that the peacock originated in Turkey – wrong again! And they thought that Turkey was in Africa. You can see the Spanish colonists were pretty confused.

Actually, the origin of Thanksgiving itself is similarly confused.

The popular assumption is that it was first celebrated by the Mayflower immigrants and the Wampanoag natives at Plymouth in what is now called Massachusetts, 1621. They feasted on venison, neyhom (Wampanoag for gobblers), eels, mussels, corn and beer.

But wait, say Virginians, the first precursor to our annual November food-a-palooza was not in Massachusetts — the Thanksgiving feast originated down in Jamestown colony, back in 1608.

Whoa, there, hold your horses, pilgrims. Folks in El Paso, Texas, say that it all began way out there in 1598, when Spanish settlers sat down with people of the Piro and Manso tribes, gave thanks, then feasted on roasted duck, geese and fish.

“Ha!” says a Florida group, asserting the very, very first Thanksgiving happened in 1565, when the Spanish settlers of St. Augustine and friends from the Timucuan tribe chowed down on cocido — a stew of salt pork, garbanzo beans, and garlic — washing it all down with red wine.

Wherever it began, and whatever the purists claim is “official,” Thanksgiving today is as multicultural as America. So let’s enjoy — even if we’re in smaller groups or observing virtually this year.

Kick back, give thanks we’re in a country with such ethnic richness, and dive into your turkey rellenos, moo-shu turkey, turkey falafel, barbecued turkey.

Jim Hightower is a columnist and public speaker.

Kindly light

“Eastern Point Light, 1940s’’ (watercolor on paper), by Alfred Levitt (1894-2000) at the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass.

Fresnel Lens for lighthouses originally designed by Augustine Jean Fresnel and displayed at the Cape Ann Museum.

Don Pesci: Biden and the pride of post-modern cultural Roman Catholics

VERNON, Conn.

Presumptive President-elect Joe Biden has let it be known throughout his half-century-long political career that he is a Kennedy Roman Catholic; in some quarters, Kennedy Catholicism is called cultural Catholicism.

Biden helpfully explained cultural Catholicism to Jack Jenkins, a reporter for Religion News Service (RNS). Hit this link to read it.

In it, Mr. Jenkins writes that “Joe Biden….was shaped by a very American Catholic faith: The way he manages his allegiance to Catholicism gives a glimpse of how Biden will govern as he takes hold of an office he has sought since 1988.’’

The piece lifts several quotes from Biden’s book Promises to Keep: On Life in Politics.

“I’m as much a cultural Catholic as I am a theological Catholic,” Biden wrote. “My idea of self, of family, of community, of the wider world comes straight from my religion. It’s not so much the Bible, the beatitudes, the Ten Commandments, the sacraments, or the prayers I learned. It’s the culture.”

Jenkins offers the following gloss: Cultural Catholicism is “a form of faith that experts," many of them cultural Catholics, "describe as profoundly Catholic in ways that resonate with millions of American believers: It offers solace in moments of anxiety or grief, can be rocked by long periods of spiritual wrestling and is more likely to be influenced by the quiet counsel of women in habits or one’s own conscience than the edicts of men in miters.”

One of the “men in miters” is, of course, the Pope.

John F. Kennedy, a Catholic running for president at a time when anti-Catholicism was still very much a force to be reckoned with – historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr., Kennedy’s chief biographer, characterized anti-Catholicism as the oldest prejudice in the United States – easily disposed of the notion that he would be the Pope’s cat’s-paw.

A month after Kennedy had met with a group of Protestant pastors, he traveled to Houston and there delivered a speech to a second group of pastors in which he said, “I believe in an America that is officially neither Catholic, Protestant nor Jewish; where no public official either requests or accepts instructions on public policy from the Pope.”

That distinction pretty much doused irrational fears that Kennedy as president would simply be an agent of the Vatican.

Since Kennedy’s day, many Catholics have served their country in various positions with distinction and fidelity both to their church and to the Constitution that they promised on oath to uphold. Catholicism, even the Catholicism of Popes, is not incompatible with patriotism.

Biden, Jenkins makes clear, likes the “culture” of Catholics, nuns and rosary beads, which he carries with him in his pocket. Cultural Catholicism, we are given to understand, is balanced in his thought processes with the theology of his church. The difficulty here is that there are among us cultural Catholics in open warfare against Catholic theology as explicated by the historic Roman Catholic Church, the Popes down through the ages, and leading Catholic clerics.

“Biden’s personal connection to the faith,” Jenkins notes, “remains a highly visible part of his political persona. He carries Rosary beads at all times, fingering it during moments of anxiety or crisis. When facing brain surgery after his short-lived presidential campaign in 1988, he reportedly asked his doctors if he could keep the beads under his pillow. Earlier this year, rival Pete Buttigieg noticed Biden holding Rosary beads backstage before a primary debate.”

Hilaire Belloc – author of the Road to Rome, a close friend of G.K. Chesterton and an unapologetic Catholic – also carried Rosary beads with him. One day, while campaigning for a seat in the British House of Commons, , he was accosted by a lady who shouted out to him from the crowd surrounding his campaign stump that he was a “papist.”

Belloc drew his Rosary beads from his pocket and said to the lady, “Madam, do you see these beads. I pray on them every night before I go to sleep, and every morning when I awake. And, if that offends you, madam, I pray God he will spare me the ignominy of representing you in Parliament.”

Unlike Biden, Belloc's rosary was more than a totem for him; it was the copula that linked him, both theologically and culturally, to the Catholic Church, ancient and modern, rolling through the years from Peter, the Rock against which the gates of Hell shall not prevail, to the sometimes twisted post-paganism of the post-modern 21st Century..

Kennedy’s sword of sundering has two cutting edges. The post-modern cultural Catholic suffers from inordinate pride; he really does think himself not only politically superior to popes, doubtful, but also superior to his church in matters of theology, faith and morals.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

In Vermont, fighting the virus and killing the game dinner

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary’’ in GoLocal24.com

Vermont, under the firm leadership of old-fashioned moderate (and anti-Trump) Republican Gov. Phil Scott, has been a leader in controlling COVID-19 through tight travel/quarantine rules, adherence to face-mask rules and, probably most important, the Green Mountain State’s traditionally strong, unselfish civic sensibility. Now, as the virus explodes around America, it faces new challenges. States can’t post the National Guard at all roads leading into their states to check for possibly infected travelers from high-risk places! But I’m pretty sure that Vermont will face its COVID challenges decisively and effectively.

xxx

Of course, some would say that the fact that Vermont is a largely rural state makes it easier to control the spread of COVID-19. But look at how terrible the rural Red States, such as in the Great Plains, are doing with it! And consider that Vermont is in the Northeast, the nation’s most densely populated region.

A kitchen interior with a maid and a lady preparing game, c. 1600.

\

I try to avoid eating animals, especially my fellow mammals, but I’ll miss (well, in a way) the annual game dinner at the Congregational church in Bradford, Vt., which has been cancelled, perhaps permanently, after 64 years. I had attended, off and on, with a bunch of friends since 1989. I went after friends’ annual relentless urgings that I join them.

The proximate cause of the cancellation, of course, was the pandemic. Couldn’t have all those folks sitting shoulder to shoulder at those long, communal tables. But before COVID, the church had had increasing difficulty in getting people to work at the event, the church’s biggest annual fundraiser.

Another little piece of Americana goes down.

In Bradford, once a thriving small manufacturing town, originally because of water power: Woods Library and Hotel Low, c. 1915 postcard view.

Parks as places for ‘relief from ordinary cares’

Walnut Hill Park is a large public park west of the downtown of the old manufacturing city of New Britain, Conn. Developed beginning in the 1860s, it is an early work of Frederick Law Olmsted, with winding lanes, a band shell and the city's monument to its World War I soldiers.

“It is a scientific fact that the occasional contemplation of natural scenes of an impressive character, particularly if this contemplation occurs in connection with relief from ordinary cares, change of air and change of habits, is favorable to the health and vigor of men and especially to the health and vigor of their intellect beyond any other conditions which can be offered them, that it not only gives pleasure for the time being but increases the subsequent capacity for happiness and the means of securing happiness.”

— Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903), the father of American landscape architecture and most famous as the designer of New York’s Central Park. He was born in Hartford and died in Belmont, Mass.

In the “Emerald Necklace’’ parkland of Boston and Brookline, designed by Olmsted and established starting in 1878.

“Frederick Law Olmsted” (oil), by John Singer Sargent, 1895, at the Biltmore Estate, Asheville, N.C.

Llewellyn King: Rigidity can be deadly to wonderful innovation

Magazine cover in 1928, when radio was becoming very big but inventors were already thinking ahout television.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Simple advice to innovators and policymakers: Don’t worry about collateral needs or they will distort your good growth and policy efforts.

If we look back, the development of the automobile had collateral effects beyond the ability of the auto pioneers to conceive. Yet there were those who would have restricted automobile development because they worried about the collateral effects, including that there wouldn’t be enough gasoline, oil would run out, cars were dangerous and fueling stations would explode.

The lesson wasn’t that those were minor concerns, but that they were giant and reasonable concerns that didn’t take into account that there would be as much creativity in solving those problems as there was in creating the primary product in the first place.

If the Wright brothers had worried about how we would keep aircraft from colliding with each other, well, we would have more trains and passenger ships.

The message is that innovation begets innovation. Invent one thing and then invest in something else to support it.

Yet there are reactionary forces at work in the creative arena all the time.

To continue with the automobile example, there are naysayers to the electric car everywhere. Sometimes they are driven by economics, but often they are just worried about great change. I can hardly pass a day without reading alarmist pieces about the disposal of batteries, a possible shortage of lithium from friendly suppliers, or that there won’t be enough charging points.

To all that, I say piffle.

History tells us that these seeming problems will be solved by the same inventiveness that has brought us to this time, when we are seeing a switch from the internal combustion engine -- faithful servant though it has been -- to electricity.

The danger is rigidity.

Rigidity is the seldom-diagnosed inhibitor of good science, good engineering and good policy. Rigidity in policy, or even just in belief, restricts and distorts.

A rigid belief is that nuclear waste is a huge problem. I would submit that it is less of a problem than many other wastes we are leaving to future generations. Rigid concerns and rigidly wrong radiation standards led the electric utilities to turn to coal, and now to wind and solar to move away from coal and its successor, natural gas.

Medicine is beset by rigidities and it always has been, from excessive use of bleeding therapy to surgeons who believed it was ungentlemanly to wash their hands. Those who suffer from less common diseases -- Myalgic Encephalomyelitis, also known as Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, is one -- are hurt by medical profession rigidities. The doctors try to fit disease into what they know and treat patients with known but inappropriate therapies.

Even such great innovators as Henry Ford weren’t without their crippling rigidities. Henry Ford was opposed to 6-cylinder engines and wanted all cars to be black.

Political rigidities are perhaps the most pernicious. I would suggest that the fear of the bogeyman of socialism has prevented America from developing a sensible health-care system — one that is less expensive and has better results. It doesn’t have to be modeled on Britain’s National Health Service, but it could borrow from Germany or The Netherlands, where the health system is universal but provided by private insurance. Ditch the rigidity and start fixing the patient -- in this case, the whole system.

Our educational system is plagued with rigidities. At the lower end, the public schools, children aren’t getting the basics they need to function in our society. At the high end, the universities, there is a new kind of aristocracy where the favored faculty are coddled, shielded and underproductive, while the cost for students is prohibitive.

Our most productive, most gifted graduates are compelled to align their careers with jobs that will pay enough to free them from the debt burden we start them in life with. This might cause a bright student to go into computer science when he or she longed to study astronomy, certainly a less well-paid future.

Rigidities kept women from seeking new roles and responsibilities, and from seeking their own personal and professional identities rather than have them defined by the outside, male-dominated society. Homemaking, yes; corporate management, no.

Rigid doctrine is always at work and is an unseen impediment to future innovation in science, social structure and, above all, in politics Watch for it.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Web site: whchronicle.com

There’s long been pushback against the world-changing innovation of electric cars.

‘Find a route’

“Dust to Dust” (alcohol Inks and Ink on Yupo) by James C. Varnum, in his show “Worlds Apart,’’ at at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, in December.

He writes:

"Come explore ‘Worlds Apart,’’ where there are relationships and connections among and within the paintings. Explore the terrain created by the textures and mark making. The lines on the painted work emphasize a topography that I’ve imposed. These patterns, symbols and maps will be discovered as you embark on a journey into the paintings. Stay awhile. Travel around. Flow through. Find a route that takes you where you want to go."

See:

galateafineart.com

Mr. Varnum grew up in southern New Hampshire and his gallery is in Arlington, Mass.

UMass Memorial plans Worcester field hospital for COVID-19 patients

The DCU Center (originally Centrum) is an indoor arena and convention center complex in downtown Worcester.

Here’s The New England Council’s (newenglandcouncil.com) latest roundup of COVID-19 news in our region:

* ‘‘UMass Memorial Health Care has laid plans for a field hospital in the DCU Center in Worcester. (DCU stands for Digital Federal Credit Union.) The field hospital was decommissioned last spring; however, UMass Memorial has since been preparing to open the site once again in anticipation of another surge in COVID-19 related hospitalizations. Read more here.’’

* ‘‘ Mass General Brigham and Beth Israel Lahey Health are reporting that their hospitals are better prepared for a second COVID-19 wave. Hospital officials are in communication to balance COVID-19 patients across multiple sites in the Greater Boston area if the need arises. Read more here. ‘‘

* ”The American Hospital Association has produced a podcast providing useful information on patient wellness, preventing chronic diseases, and prioritizing quality and patient safety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Read more here. ‘‘

* ’’ (Boston-based) Harbor Health Services has partnered with instaED Paramedics to provide elders who participate in their Elder Service Plan (ESP) with at-home urgent care. The program will allow participants to receive treatments normally provided in the emergency room while safe at home. Read more here.’’

NED chats weekly on WADK's 'Talk of the Town'

On most Thursdays at 9:30 a.m., Robert Whitcomb from New England Diary and GoLocal24.com will chat with Bruce Newbury on Mr. Newbury’s Talk of the Town show on WADK-A.M. (Newport).

Listen to it via broadcast or wadk.com

“The Fireside Chat,’’ bronze sculpture by George Segal in Room Two of the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial, Washington, D.C.. FDR ‘s fireside chats via radio were very popular among millions of Americans.

Glorious radio from 1941.

Growing up 'underexposed'

“My parents were both from Vermont, very old-fashioned New England. We heated our house with wood my father chopped. My mom grew all of our food. We were very underexposed to everything.’’

— Geena Davis (born 1956), actress. Though her parents were native Vermonters, Ms. Davis grew up in Wareham, Mass., at the northern end of Buzzards Bay. So she may be exaggerating a tad.

Entering Wareham, Mass., “The Gateway to Cape Cod.’’

The tie-loving ghost

“Last night my color-blind chain-smoking father

who has been dead for fourteen years

stepped up out of a basement tie shop

downtown and did not recognize me.’’

— From “My Father’s Neckties,’’ by Maxine Kumin (1925-2014), a U.S. poet laureate and Pulitzer Prize-winner and a Warner, N.H., horse farmer.

Statue of New Hampshire Gov. Walter Harriman in Ms. Kumin’s town of Warner, N.H.