William Morgan: Looking lithographically at proud 19th Century Maine

As part of its celebration of the 200th anniversary of Maine statehood, the Bowdoin College Museum of Art last winter held an exhibition of lithographs of 19th-Century town views in the Pine Tree State. Since then, the college and Brandeis University Press have published a handsome oversize book, Maine's Lithographic Landscapes: Town and City Views, 1830-1870.

What it says above:

“View of Portland, Me./Taken from Cape Elizabeth before the great conflagration of July 4th 1866

“Tinted lithograph from a photograph taken by Edward F. Smith and published by B.B. Russell & Co., Boston. 1866. ‘‘

The author is Maine State Historian Earle G. Shettleworth Jr., who was the state's historic-preservation officer for nearly five decades. The modest and scholarly Shettleworth may well know more about the state's architecture and other art than anyone else. Devoting his life to documenting everything Maine, he has written and lectured prodigiously on every aspect of Maine's built environment, and also written studies of female fly fisherman, photographers, painters, and parks.

“Augusta, Me., 1854.

Drawn by Franklin B. Ladd. Tinted lithograph by F. Heppenheimer, New York.’’

In a bit of Maine understatement, the co-director of the Bowdoin Museum, Frank H. Goodyear Jr., writes, "In Nineteenth Century America, the printed city view enjoyed wide popularity." As Shettleworth notes, the prints helped "forge the young state's identity” and served as "expressions of pride of place’’. During the period under review many towns and cities across America were memorialized in printed images drawn by artists famous and unknown.

Still, Maine was still a small state in the back of beyond. (its population was under 300,000 at the time it separated from Massachusetts, in 1820.) Thus, what the book’s creators call the "first comprehensive record of urban prints during the first fifty years of statehood" is somewhat limited: There are a total of 26 views of 11 places. Those are augmented by a score or more images of the often somber Bowdoin campus, including a painting, old photos, and two Wedgwood plates. Groundbreaking as the book is, viewing the exhibition itself would probably be more satisfying.

That said, Maine's Lithographic Landscapes is a handsome production. The Bowdoin Museum has a history of elegant catalogs, and this co-operative venture with Brandeis demonstrates that press's growing role as a publisher of New England studies. I am not sure that anyone looks at colophons (publisher’s emblems) anymore, so it is worth noting that the book was designed by the eminent book designer, Sara Eisenman.

Earle G. Shettleworth, Jr., Maine's Lithographic Landscapes, Brandeis University Press, 2020, 144 pages, $50.

William Morgan is a Providence-based architectural historian, photographer and essayist. His latest book is Snowbound: Dwelling in Winter.

Seeing red in 2020

“The Red Road” (acrylic on canvas), by Mark Chadbourne, in the show “RED 2020,’’ in the Cambridge (Mass.) Art Association’s Kathryn Schultz Gallery, through Dec. 17. The gallery has an annual show that is always titled BLUE or RED. RED can evoke happiness (your “red letter day”) and passion but it can also summon up intensity, including violence and pain, of which we’ve had plenty this year.

Chris Powell: Deconstructing COVID-19 hysteria

“Hysteria Patient,’’ by Andre Brouillet (1857-1914)

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Amid the growing panic fanned by news organizations about the rebound in the virus epidemic, last week's telling details were largely overlooked.

First, most of the recent "virus-associated" deaths in Connecticut again have been those of frail elderly people in nursing homes.

Second, while dozens of students at the University of Connecticut at Storrs recently were been found infected, most showed no symptoms and none died or was even hospitalized. Instead all were waiting it out or recovering in their rooms or apartments.

And third, the serious-case rate -- new virus deaths and hospitalizations as a percentage of new cases -- was running at about 2 percent, a mere third of the recent typical "positivity" rate of new virus tests, the almost meaningless detail that still gets most publicity.

Recognizing that deaths, hospitalizations, and hospital capacity should be the greatest concerns, Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont last week recalled that at the outset of the epidemic he had the Connecticut National Guard erect field hospitals around the state and that 1,700 additional beds quickly became available but were never used. This option remains available.

The governor's insight should compel reflection about state government's policy on hospitals -- policy that for nearly 50 years has been, like the policy of most other states, to prevent their increase and expansion.

The premise has been the fear that, as was said in the old movie, "if you build it, they will come" -- more patients, that is. The demand for medical services, the policy presumes, is infinite, and since government pays most medical costs directly or indirectly, services must be discreetly rationed -- that is, without public understanding -- even if this prevents economic competition among medical providers.

So in Connecticut and most other states you can't just build and open a hospital; state government must approve and confer a "certificate of need." Who determines need? State government, not people seeking care.

Of course, this policy was not adopted with epidemics in mind. Indeed, in adopting this policy government seems to have thought that epidemics were vanquished forever by the polio vaccines in the 1960s.

Now it may be realized that, while epidemics can be exaggerated, as the current one is, they have not been vanquished and the current epidemic -- or, rather, government's response to it -- has crippled the economy, probably in the amount of billions of dollars in Connecticut alone.

That cost should be weighed against the cost of hospitals that were never built. Maybe they could have been built and maintained only for emergency use, and an auxiliary medical staff maintained too, just as the National Guard is an all-purpose auxiliary.

Also worth questioning is the growing clamor for virus testing. The heightened desire for testing in advance of holiday travel is natural, but testing is not so reliable, full of false positives and negatives. Someone can test negative on Monday and on Tuesday can start manifesting the virus or contract it and be without symptoms.

Testing may be of limited use for alerting people that they might well isolate themselves for a time even if they are without symptoms. But people without symptoms are far less likely to spread the virus than infected people who don't feel well.

Only daily testing of everyone might be reliable enough to be very effective, but government and medicine are not equipped for that and it would be impractical anyway. Weekly testing of all students and teachers in school might be practical and worthwhile but terribly expensive, and only a few wealthy private schools are attempting it.

Contact tracing policy needs revision. Nothing has been more damaging and ridiculous than the closing of whole schools for a week or more because one student or teacher got sick or tested positive. As the governor notes, because of their low susceptibility to the virus, children may be safer in school than anywhere else.

Risk for teachers is higher but they also are more likely to become infected outside of school. They might accept the risk in school out of duty to their students, whose interrupted education is the catastrophe of the epidemic.

Meanwhile the country needs two vaccines -- one against the virus itself and one against virus hysteria.=

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.

To the pie and pudding

Over the river, and through the wood,

To Grandfather's house we go;

the horse knows the way to carry the sleigh

through the white and drifted snow.

Over the river, and through the wood,

to Grandfather's house away!

We would not stop for doll or top,

for 'tis Thanksgiving Day.

Over the river, and through the wood—

oh, how the wind does blow!

It stings the toes and bites the nose

as over the ground we go.

Over the river, and through the wood—

and straight through the barnyard gate,

We seem to go extremely slow,

it is so hard to wait!

Over the river, and through the wood—

When Grandmother sees us come,

She will say, "O, dear, the children are here,

bring a pie for everyone."

Over the river, and through the wood—

now Grandmother's cap I spy!

Hurrah for the fun! Is the pudding done?

Hurrah for the pumpkin pie!“The New-England Boy's Song about Thanksgiving Day” (1844), by Lydia Maria Child (1802-1880), writer, social reformer and human-rights promoter. She grew up in Medford, Mass., and the house referred to the grand one above, which had been souped up from the simpler structure she knew as a child. It’s now owned by Tufts University. The “river” is the Mystic River. Winter weather came earlier then.

The Mystic River around 1790.

Llewellyn King: Trust deficit endangers vaccine rollout

An anti-vaccination caricature by James Gillray, “The Cow-Pock—or—The Wonderful Effects of the New Inoculation!’’ (1802)

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

There is a trust deficit in this country, and it may kill a lot of us.

We haven’t been trusting for a long time, but distrust reached its zenith during and after the recent election. The election, still contested, brought with it a massive overhang of distrust. Indeed, the past four years have been marked by wide distrust.

Distrusting the election results isn’t fatal. But distrusting the experts on the need to get vaccinated for COVID-19 is. Yet there are reports that as many as 50 percent of Americans won’t get the vaccine when it is available. That is lethal and a true threat to national security, the economy, our way of life, everything.

If we don’t get our jabs, we will continue to die from coronavirus at an alarming rate. Over 258,000 Americans have perished and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention projects 298,000 deaths by mid-December.

As I recall, it was during the late 1960s that we began wide distrusting. By the end of the Vietnam War, we distrusted on a huge scale. We distrusted what we were told by the military, what we were told by President Lyndon Johnson and then by President Richard Nixon.

We also distrusted the experts. Just about all experts on all subjects, from nuclear-power safety to the environmental impact of the Concorde supersonic passenger jet.

Beyond Vietnam, distrust was fed by the unfolding evidence that we had been the victims of systemic lying. This led to big social realignments, as seen in the civil rights movement, the women’s movement, and the environmental movement. These betrayals exacerbated our natural American distrust of officialdom.

The establishment and its experts had been caught lying about the war and about other things. It was a decade that detonated trust, shredded belief in expertise, and left many of us feeling that we might as well make it up as we went along.

Now the trust deficit is back.

If LBJ and Nixon fueled distrust in the 1960s and early 1970s, the current breach of trust belongs to President Trump and his enablers scattered across the body politic, from presidential counselor Kellyanne Conway with her “alternative facts” to the Senate Republicans and their disinclination to check the president.

The trust deficit has divided us. Seventy-three million did vote for Trump and many of those believe what, most dangerously, he has said about the pandemic.

The result has been the growth of diabolical myths about COVID-19. Taking seriously some, or all, of Trump’s outpourings on the coronavirus -- from his advocacy of sunlight and his off-label drug recommendations, such as hydroxychloroquine, to putting the pandemic out of mind as a “hoax” -- fomented its spread.

We have been waiting for a medical breakthrough to repel and conquer COVID-19 and it looks as though that is at hand with the arrival of not one but three vaccines, the first of which should be available in about three weeks to the most vulnerable populations. The development of these vaccines represents a stupendous medical effort: the Manhattan Project of medicine.

But it will all be in vain if Americans don’t trust the authorities and don’t get vaccinated. It looks as though, according to surveys, 50 percent of the population will get vaccinated. The rest will choose to believe in such medical fictions as herd immunity — a pernicious idea that eventually we will all be immune by living with COVID-19. It should be noted that this didn’t happen with such other infectious diseases as bubonic plague, smallpox, polio, even the flu.

My informal survey of research doctors puts the odds on who will get vaccinated a little better than 50 percent. They conclude that one third will get vaccinated, one third will wait to see the results among those who got vaccinated early, and one third won’t get vaccinated, believing that the disease has been hyped and that it isn’t as serious as the often-castigated media says. Some of the “COVID-19 deniers” will be the permanent anti-vaxxers, people who think that vaccines have bad side effects; they believe, for example, that the MMR vaccine causes autism.

This medical heresy even as hospitals are filling to capacity, their staff are exhausted, and bodies are piling up in refrigerated trailers because there is nowhere to put them.

Without near-universal vaccination, the coronavirus will be around for years. The superhuman effort to get a vaccine will have been partially in vain. The silver bullet will be tarnished.

Get a grip, America. Get your jabs.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com. and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Before the anti-vaxxers: Administration of the polio inoculation, including by the first polio-vaccine developer, Jonas Salk, himself, in 1957 at the University of Pittsburgh, where his team had developed the vaccine.

In a postwar poster the Ministry of Health urged British residents to immunize children against diphtheria.

Karen Gross: Role-modeling by adults too often lacking in COVID-19 crisis

The Rev. John Jenkins, the president of the University of Notre Dame. Did he not wear a mask at a reception in order to suck up to Donald Trump?

BOSTON

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Sadly, the number of COVID-19 cases across the globe is rising. And while vaccines are in the offing, we may have many weeks between now and their availability, time in which more individuals can become infected and too many will die. In absolute terms, the numbers are staggering in the U.S. and around the world.

It is against this background that we should be concerned about super-spreader events. One category of such events includes college and high school students gathering and partying in ways that violate the COVID-19 protective measures (mask wearing, social distancing, avoiding large indoor get-togethers). Some of these problematic events occur off campus, others occur on campus. Wherever they happen, they have produced varying outcomes: quarantines; stoppage of athletic events; elimination of on-campus in-person learning (for a short or long period); changes in scheduling to eradicate vacations or campus departures; and students contracting COVID.

It is easy to blame students (whether in college or high school) and parents (in the context of high schoolers and even some college students who are now at home taking online classes). Can you hear adults within families and educational institutions saying: “How stupid can these young people be? They aren’t complying with the three simple rules.”

But the failure of compliance among young people must be contextualized. We are not living in “normal” times and behaviors need to be understood in light of the impact of the pandemic constraints as well as the age of students and their developmental stage.

Lack of physical connection, risk-taking, brain development

Start with this obvious observation: The wearing of masks, social distancing and school closures have left many young people without quality means of connecting. As much as they can use technology and we are certainly doing that (Zoom fatigue is a known phenomenon, as is online oversharing), there is something that youth are missing: real, hands-on human engagement. They are missing contact; they are missing touch. They are without smiles and hugs and physicality.

The absence of physical contact for an extended period (and what still seems like an indefinite period) is difficult and frustrating for young people. It makes them want to rebel against the constraints and ignore the accompanying risks that often are known to them. In short, students disobey COVID-19 rules because they have real needs for in-person connectivity that are unmet.

Brain science supports this conclusion: Most young people cannot fully control their behavior on their own and they discard the COVID-19 rules because of the stage of their brain development. Risk-taking is common among young people; it goes hand and hand with their psychosocial development. We know that young people underestimate risk: think about fast cars and drunk driving, texting while driving and physical challenges that seem likely to cause serious physical injury. Also, we know that quality judgment and decision-making do not occur until the mid to late 20s. (There are also upsides to this stage of development but that’s the subject of another article.)

Our expectation of strict compliance misses the biological reality of why students are disobeying. The parts of their brain that manage and measure risks are not fully developed. Youth are not trying to be disobedient (well, some are as a form of rebellion that is also age-appropriate). Many simply are not able to make quality decisions—at least not without adult intervention, and therein lie some answers as to what we can do to move toward greater compliance.

Two concrete examples

Before turning to solutions, let’s look at two actual scenarios that inform a pathway forward.

In late October, more than 20 high schoolers attended a party at a private home in Marblehead, Mass. Not only was there an absence of mask wearing, there was an absence of social distancing and there was shared drinking out of cups. The police were called. The students scattered. No one was prosecuted. The superintendent in a remarkably astute letter recognized student needs to connect, but then closed the high school as a precaution and decried that they can and must do better.

A few months earlier, Marist College, in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., suspended some students for participating in off-campus parties and later, when the non-compliance continued, had to shut down the campus physically. Before moving to online learning, the college president was quoted as saying: “Please don’t be a knucklehead who disregards the safety of others and puts our ability to remain on campus at risk.”

Pathways forward

We know that student risky behavior can be modified, and there are a variety of strategies that enable change. The problem is that we have not deployed them in the context of this pandemic for reasons that aren’t at all clear to me.

We would be wise to spend more time recognizing the psychological reasons for student behavior and, based on that science, create new strategies that mitigate the reasons noted above for non-compliance. And since the stage of student development also opens the door to creativity, why not use creativity as part of the solution?

Consider these approaches: Social-norming campaigns can show compliance or willingness to comply by many students to norms despite peer perceptions. Detailed discussions with students can lead to an understanding of the risks (based on science) to others and themselves with concrete examples and data points. Youth empathy engines can be activated such that students are engaged in doing activities that help others in their communities. These can be conducted by parents and educators alike. Consider a version of this “rock” project in Texas. Students could all get and paint rocks and then they and other students can place the rocks around school buildings or a college campus.

For the record, let’s eliminate one approach: student punishment and suspension as the first line of defense. We should be punishing when there is intent. Absent intent, we should not rush into suspending students. Yes, based on parties, we need to quarantine; yes, based on parties, we need to shut down campus residential life or in-person learning for a period of time. But calling people “knuckleheads” is not helpful.

Instead, let’s think about preemptive things that could be done to prevent the non-compliant risky behavior. We can do better, as the superintendent suggested, but we need to get ahead of the problem and not be reactive to it.

Role models

From my perspective, perhaps one of the best strategies for enabling students to shift behavioral patterns and avoid risky and unwise behavior is role modeling. We know that role modeling is critically important to youth. And role models can come from a variety of locations: family, older friends and peers, educators (including administrators and coaches), religious figures and community leaders. We also know that role models can be individuals whom students do not know personally: politicians, actors, athletes.

We know, too, that an antidote to trauma is a non-familial figure who knows you and genuinely cares about your well-being and believes in you. And we know that positive role models can and do counteract negative childhood and adult experiences. Our adults need to step it up—engage with one another and their children and peers in new ways.

Despite these truths, we aren’t doing a good job of role modeling locally or nationally. Consider the absence of good role modeling in the two concrete examples given earlier involving Marblehead and Marist and similar communities, schools and colleges.

With respect to Marblehead and similar communities where parties have occurred, I would ask (in a non-accusatory way): Where were the parents who lived in the home where the party was held? Were they home? Were they aware of the party in advance? Did they buy the items for the party? Where were the parents of the other students who attended the party? Did they know where their children were going that evening? What had the parents done in anticipation of the needs of their children to plan events that would be safe? What had the high school done in advance to recognize the need for students to engage but to construct initiatives that were safe for each student and the collective of students?

With respect to Marist and similar colleges, I would ask (again, in a non-accusatory way): Where were the student life personnel? Were they aware of particular off-campus sites that might present risks? What did they do in advance to provide for the engagement needs of students in safe ways? What messaging was coming from the administration in advance? And was the reference to the students as knuckleheads wise? By way of contrast, the superintendent in Marblehead overtly recognized the student need to engage in person in these difficult times, although for safety reasons, he closed in-person learning.

For me, Lesson One is that the institutions (both high school and postsecondary) and parents need to anticipate what activities could have meet student needs. And they should involve students in planning these events. There are a myriad of possibilities: art-installation projects; distant dancing; car get-togethers (remember “car hops?) with limited numbers in cars where students listen to live music or watch a movie together? What about wrapping all the trees in crepe paper to create a “Christo-esque” artwork and even, teaching about Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s amazing and startling work involving wrapping buildings and bridges and parks?

We can be creative in seeing what the needs are and then developing approaches that meet the needs.

Lesson Two is that the parents (of the party home) and the parents of other teenagers were not (it appears) actively aware of their own child’s behavior. Had they been, I think one can rightly ask whether they would have intervened. And we can rightly ask whether they themselves, in their engagement with others, were role modeling the needed protective behavior (masks, social distancing and outdoor events). Or perhaps they did not believe in the science and thus were noncompliant.

At the college level, I’d suggest there were staff who could have guessed where problems off-campus were likely, especially if they knew their students and had their ears to the ground. Even if this was not their role before and seems interventionist or paternalistic (maternalistic), that non-interference calculus has changed when there are abundant and growing health risks not just to students but to communities. Stated differently, why did staff not act on what they learned, knew and anticipated?

Both examples showcase the absence of role modeling by adults in terms of actual behavior and anticipatory thinking.

Negative role modeling is way too common right now

Apart from role modeling by parents and educators whom students know, we have had far too many examples of failed role modeling in ways that have received national attention. And, make no mistake about this, students are well aware when public figures fail to comply with the COVID mandates and rightly ask: If they can flaunt the rules, why can’t I?

Here are several well-known examples (and I am avoiding the obvious one of our current president) that demonstrate what students are seeing in the media day-in and day-out.

Start with the Dodgers Justin Turner’s behavior following his team winning the World Series. I get the excitement but having just tested positive, he went out onto the field maskless for at least some of the time. What message does that send to young people? When you win, the rules don’t apply even though the coach was among people who were immune-compromised? And then the player went unsanctioned by Major League Baseball as if the incident should just be forgotten as a lapse in a moment of glory and because the player issued an apology.

Turn then to Gavin Newsom, the governor of California, a state struggling with COVID outbreaks (among other disasters). It turns out that he attended a birthday party with more than 10 unrelated family members at an elite restaurant in Napa and wasn’t wearing a mask apparently. Top doctors attended, too. All of this was directly in contradiction to the mandates he was issuing to his constituencies.

But perhaps the most offensive examples come from college presidents. Think about it. If our educational leaders, who have a bully pulpit and are preaching compliance to their institutions, don’t comply, why would their students or students on other campuses? A prime example is Notre Dame’s president, the Rev. John Jenkins. He attended a ceremony in honor of the nomination of Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court. To be sure, for his institution, this was a big deal as the nominee was a professor at Notre Dame’s Law School. But please, no mask? No social distancing? Was he afraid that the president (of the U.S) would see a mask as a sign of disrespect? The photographs of the non-compliance are chilling.

Students were rightfully angry as were faculty. An apology isn’t enough in the context of the virus; words don’t stop disease spread, especially when you are so forcefully asking for campus compliance with COVID protections. And Father Jenkins got COVID.

Lesson Three is obvious: Hypocrisy doesn’t fly in the COVID-19 world. Public high-profile leaders need to role model compliance all the time; their messaging is seen and heard and it matters. Negative role modeling is catching.

Now what?

The contents of this article and the examples given and lessons proffered boil down to this: We need to ramp up positive role modeling. Role modeling isn’t a part-time activity. It is a full-time obligation.

To that end, parents and educators: 1) need to come up with strategies in advance that recognize that young people need ways to engage safely; 2) must involve students in the planning of these activities that are COVID-safe; 3) need to question where students are and anticipate their behavior by offering alternatives; 4) need to talk more to students about risks and about solutions and about feelings and double standards; and 5) shouldn’t make punishment the best solution as it doesn’t work; instead, provide alternatives.

These aren’t impossible solutions. They are doable if we focus on them. And we should, for the well-being of our young people, our families and our communities.

Karen Gross is former president of Southern Vermont College and a senior policy adviser to the U.S. Department of Education. She specializes in student success and trauma across the educational landscape. Her book, Trauma Doesn’t Stop at the School Door: Solutions and Strategies for Educators, PreK-College, was released in June 2020 by Columbia Teachers College Press.

Chris Powell: Beware 'regulatory capture' of appointees to Cabinet

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Many teachers around the country are cheering the forthcoming change in national administration because Betsy DeVos will be replaced as secretary of education. DeVos, an heiress and philanthropist, has been a fan of charter schools and a foe of political correctness. While not really expert in pedagogy, at least she has not been the usual tool of teacher unions.

But President-elect Joe Biden is encouraging teachers to expect Nirvana. Addressing them the other week, Biden noted that his wife, Jill, is a community college teacher, and so "you're going to have one of your own in the White House." Presumably that means that teachers will have "one of their own" at the Education Department as well.

Among those mentioned is U.S. Rep. Jahana Hayes, the former Waterbury teacher and 2016 national teacher of the year, a Democrat who was just elected to her second term in Connecticut's 5th Congressional District.

Apart from her classroom work, Hayes has no managerial experience and her first term in Congress was unremarkable. Her recent campaign's television commercials celebrated her merely for listening to her constituents. While she won comfortably enough in a competitive district in a Democratic year, her departure for the Cabinet would prompt a special election that the Democrats might lose even as they already are distressed by the unexpected shrinkage of their majority in the U.S. House.

But then the U.S. Education Department does little to improve education. Mainly it distributes federal money to state and municipal governments, which do the actual educating. No matter who becomes education secretary, money will still get distributed and education won't improve much if at all.

Quite apart from the personalities, the big issue about the appointment of an education secretary is the big issue with other federal department heads. Why should the public cheer the appointment of an education secretary who is part of the interest group he would be regulating, any more than the public should cheer another Treasury secretary coming from a Wall Street investment bank, another labor secretary coming from a labor union, another defense secretary coming from the military or a military contractor, another agriculture secretary coming from agribusiness, and so yforth?

This kind of thing is called "regulatory capture" and it operates under both parties, though some special interests do better under one party than the other, as the cheering from the teacher unions indicates.

xxx

The virus epidemic has invited a comprehensive reconsideration of education but no one in authority has noticed.

Every day brings a change of plan and schedule in Connecticut schools. One day they're open and the next day they are abruptly converted to "remote learning" for a few days, a week or two, or a whole semester because somebody came down with the flu.

Amid all this many students have simply disappeared. Additionally, since education includes not just book learning but the socialization of children, their learning how to behave with others, the education of all children is being badly compromised.

Gov. Ned Lamont wants to leave school scheduling to schools themselves. This lets him avoid responsibility for any school's policy. But local option isn't producing much education.

The hard choice everyone is trying to avoid is between keeping schools open as normal, taking the risk of more virus infections because children are less susceptible to serious cases, or converting entirely to internet schooling and thereby forfeiting education for the missing students and socialization for everyone else.

If social contact can be forfeited, the expense of education can be drastically reduced. The curriculum for each grade can be standardized, recorded, and placed on the internet, with students connecting from home at any time, not just during regular school hours. Tests to evaluate their learning can be standardized too and administered and graded by computer. A corps of teachers can operate a help desk via internet, telephone, or email.

Much would be lost but then much already had been lost even before the epidemic, since social promotion was already the state's main education policy. Maybe the results of completely remote schooling would not be so different from those of social promotion.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Those screaming invaders

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

“It’s time to ban leaf blowers. The decibel level is a health hazard. Raking works.’’

Bravo to Richard Goldberg for posting this observation on the Next Door site.

See:

https://nextdoor.com/news_feed/?

For weeks every fall, and then again in the spring, affluent homeowners hire yard crews with screaming, gasoline-powered leaf blowers to make life utterly miserable for their human neighbors, as well as other animal life in the area, for hours a day. These infernal devices also emit copious quantities of air pollution. They’re a menace to health and should have been banned long ago. With so many people now forced to work at home, they’re hurting the health of many more people than ever. (Electric leaf blowers are quieter and don’t emit pollution.)

And we notice that the ears and lungs of many of the workers wielding these monsters aren’t protected. More than a few seem to be illegal aliens, who lack workplace protections. They don’t dare complain.

Hit this link to read a discussion in Newton, Mass., on the general public-health awfulness of gasoline-powered leaf blowers.

Yes, indeed, it’s time to ban gasoline-powered leaf blowers, at least in residential neighborhoods.

Charlotte Huff: In COVID crisis, 'unattended moral injury' to health-care workers

St. Vincent Hospital in Worcester

For Christina Nester, the pandemic lull in Massachusetts lasted about three months through summer into early fall. In late June, St. Vincent Hospital had resumed elective surgeries, and the unit the 48-year-old nurse works on switched back from taking care of only COVID-19 patients to its pre-pandemic roster of patients recovering from gallbladder operations, mastectomies and other surgeries.

That is, until October, when patients with coronavirus infections began to reappear on the unit and, with them, the fear of many more to come. “It’s paralyzing, I’m not going to lie,” said Nester, who’s worked at the Worcester hospital for nearly two decades. “My little clan of nurses that I work with, we panicked when it started to uptick here.”

Adding to that stress is that nurses are caught betwixt caring for the bedside needs of their patients and implementing policies set by others, such as physician-ordered treatment plans and strict hospital rules to ward off the coronavirus. The push-pull of those forces, amid a fight against a deadly disease, is straining this vital backbone of health providers nationwide, and that could accumulate to unsustainable levels if the virus’s surge is not contained this winter, advocates and researchers warn.

Nurses spend the most sustained time with a patient of any clinician, and these days patients are often very fearful and isolated, said Cynda Rushton, a registered nurse and bioethicist at Johns Hopkins University, in Baltimore.

“They have become, in some ways, a kind of emotional surrogate for family members who can’t be there, to support and advise and offer a human touch,” Rushton said. “They have witnessed incredible amounts of suffering and death. That, I think, also weighs really heavily on nurses.”

A study published this fall in the journal General Hospital Psychiatry found that 64 percent of clinicians working as nurses, nurse practitioners or physician assistants at a New York City hospital screened positively for acute distress, 53 percent for depressive symptoms and 40 percent for anxiety — all higher rates than found among physicians screened.

Researchers are concerned that nurses working in a rapidly changing crisis like the pandemic — with problems ranging from staff shortages that curtail their time with patients to enforcing visitation policies that upset families — can develop a psychological response called “moral injury.” That injury occurs, they say, when nurses feel stymied by their inability to provide the level of care they believe patients require.

Dr. Wendy Dean, co-founder of Moral Injury of Healthcare, a nonprofit organization based in Carlisle, Pa., said, “Probably the biggest driver of burnout is unrecognized unattended moral injury.”

In parts of the country over the summer, nurses got some mental-health respite when cases declined, Dean said.

“Not enough to really process it all,” she said. “I think that’s a process that will take several years. And it’s probably going to be extended because the pandemic itself is extended.”

Before the pandemic hit her Massachusetts hospital “like a forest fire” in March, Nester had rarely seen a patient die, other than someone in the final days of a disease like cancer.

Suddenly she was involved with frequent transfers of patients to the intensive-care unit when they couldn’t breathe. She recounts stories, imprinted on her memory: The woman in her 80s who didn’t even seem ill on the day she was hospitalized, who Nester helped transport to the morgue less than a week later. The husband and wife who were sick in the intensive care unit, while the adult daughter fought the virus on Nester’s unit.

“Then both parents died, and the daughter died,” Nester said. “There’s not really words for it.”

During these gut-wrenching shifts, nurses can sometimes become separated from their emotional support system — one another, said Rushton, who has written a book about preventing moral injury among health- care providers. To better handle the influx, some nurses who typically work in noncritical care areas have been moved to care for seriously ill patients. That forces them to not only adjust to a new type of nursing, but also disrupts an often-well-honed working rhythm and camaraderie with their regular nursing co-workers, she said.

At St. Vincent Hospital, the nurses on Nester’s unit were told one March day that the primarily post-surgical unit was being converted to a COVID unit. Nester tried to squelch fears for her own safety while comforting her COVID-19 patients, who were often elderly, terrified and sometimes hard of hearing, making it difficult to communicate through layers of masks.

“You’re trying to yell through all of these barriers and try to show them with your eyes that you’re here and you’re not going to leave them and will take care of them,” she said. “But yet you’re panicking inside completely that you’re going to get this disease and you’re going to be the one in the bed or a family member that you love, take it home to them.”

When asked if hospital leaders had seen signs of strain among the nursing staff or were concerned about their resilience headed into the winter months, a St. Vincent spokesperson wrote in a brief statement that during the pandemic “we have prioritized the safety and well-being of our staff, and we remain focused on that.”

Nationally, the viral risk to clinicians has been well documented. From March 1 through May 31, 6 percent of adults hospitalized were health-care workers, one-third of them in nursing-related occupations, according to data published last month by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

As cases mount in the winter months, moral injury researcher Dean said, “nurses are going to do the calculation and say, ‘This risk isn’t worth it.’”

Juliano Innocenti, a traveling nurse working in the San Francisco area, decided to take off for a few months and will focus on wrapping up his nurse practitioner degree instead. Since April, he’s been seeing a therapist “to navigate my powerlessness in all of this.”

Innocenti, 41, has not been on the front lines in a hospital battling COVID-19, but he still feels the stress because he has been treating the public at an outpatient dialysis clinic and a psychiatric hospital and seen administrative problems generated by the crisis. He pointed to issues such as inadequate personal protective equipment.

Innocenti said he was concerned about “the lack of planning and just blatant disregard for the basic safety of patients and staff.” Profit motives too often drive decisions, he suggested. “That’s what I’m taking a break from.”

Building Resiliency

As cases surge again, hospital leaders need to think bigger than employee-assistance programs to backstop their already depleted ranks of nurses, Dean said. Along with plenty of protective equipment, that includes helping them with everything from groceries to transportation, she said. Overstaff a bit, she suggested, so nurses can take a day off when they hit an emotional cliff.

The American Nurses Association, the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN) and several other nursing groups have compiled online resources with links to mental health programs as well as tips for getting through each pandemic workday.

Kiersten Henry, an AACN board member and nurse practitioner in the intensive care unit at MedStar Montgomery Medical Center, in Olney, Md., said that the nurses and other clinicians there have started to gather for a quick huddle at the end of difficult shifts. Along with talking about what happened, they share several good things that also occurred that day.

“It doesn’t mean that you’re not taking it home with you,” Henry said, “but you’re actually verbally processing it to your peers.”

When cases reached their highest point of the spring in Massachusetts, Nester said there were some days she didn’t want to return.

“But you know that your friends are there,” she said. “And the only ones that really truly understand what’s going on are your co-workers. How can you leave them?”

Charlotte Huff is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Socially distanced sculpture

“Big C” (aluminum bar 0.5" x 2", Ultrex fibers (polythylene), by Robert Osborne, in the “11th Annual Flying Horse Outdoor Sculpture Exhibit: Art at a (Social Distance)”, at the Pingree School, South Hamilton, Mass, through Nov. 29.

This exhibit takes place across the school’s 100-acre campus every fall, and this year is no exception, despite COVID-19. The 50 sculptures in the show are spread throughout the campus at least 10 feet apart from one another to ensure visitor safety.

The Pingree School, in South Hamilton, Mass., on the North Shore of Greater Boston. In 1961, the private co-ed high school was founded by Sumner Pingree and his wife, Mary Pingree, in this mansion on the estate where they had raised their three sons. A lot of their money came from agricultural and other investments in Cuba. But the Cuban government seized their land holdings after Fidel Castro’s Communists took over.

Roger Warburton: Ocean damage increases in CO2 buildup as climate warms

January sea surface temperatures off southern New England have risen significantly since 1980.

— Roger Warburton/ecoRI News

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Living in Rhode Island, we are aware how the ocean rules our weather. What is less well known is that climate change is fundamentally altering the waters off our coast.

The image above shows how the January temperature of the ocean off New England has changed since 1980. For example, vast areas of dark blue — representing temperatures around 41-43 degrees Fahrenheit — have shrunk and are now a lighter blue, representing temperatures around 43-45 degrees.

The effects of a temperature rise in the ocean are significantly different from a temperature rise over land. We experience this difference when we walk across a sandy beach on a hot day. Exposed to the same sunlight, the sand burns our feet while the ocean warms gradually to the perfect temperature for a summer swim.

Rhode Island’s climate is moderated because the ocean takes longer than the land to heat up over the summer and longer to cool down during the fall.

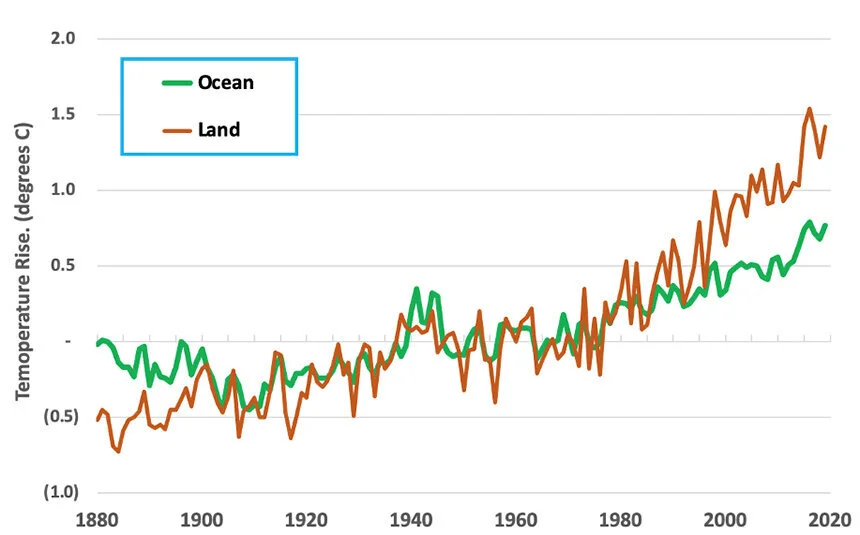

The global impact of this effect is shown in the image below, which shows that, over recent decades, the continents have warmed much more rapidly than the oceans. The Earth’s land areas were 1.4 degrees Celsius (2.5 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than the 20th-Century average, while the oceans were 0.8 degrees Celsius (1.4 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer.

Since 1880, the Earth’s land temperature has risen faster than the ocean temperature. “

— Roger Warburton/ecoRI News

Unfortunately, the ocean’s smaller temperature rise isn’t good news, because the oceans can store more than four times as much heat as the land.

Even though ocean temperatures have risen less than the land’s, it’s becoming clear that the impacts of climate change depend on a complex interaction between dry land and the warming ocean.

Ships and buoys have been recording sea surface temperatures for more than a century. International cooperation and sharing of data between nations has created a global database of sea surface temperatures going back to the middle of the 19th century.

In addition, modern satellites remotely measure many ocean characteristics over the entire extent of the Earth’s oceans. The data are now so accurate that it’s possible to detect the small temperature rise from ships’ propellers as they traverse the oceans.

The warming of both the land and the oceans is caused by rising levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide. When CO2 dissolves in the ocean, it forms carbonic acid, which in turn, breaks into hydrogen and bicarbonate ions. Clams, mussels, crabs, corals and other sea life rely on those carbonate ions to grow their shells.

In 2015, Mark Gibson, deputy chief of marine fisheries at the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management, noted that ocean acidification is a “significant threat” to local fisheries.

In fact, a study published in 2015 found that the Ocean State’s shellfish populations are among the most vulnerable in the United States to the impacts of acidification.

In polar regions such as Alaska, the ocean water is relatively cold and can take up more CO2 than warmer tropical waters. As a result, polar waters are generally acidifying faster than those in other latitudes.

The water in warmer regions can’t hold as much CO2 and are releasing it into the atmosphere. Therefore, the acidification from carbon dioxide is damaging the oceans in both polar and equatorial regions.

Warming oceans are also changing the winds that whip up the ocean, resulting in upwells from deep waters that are nutrient-rich but also more acidic.

Normally, this infusion of nutrient-rich, cool, and acidic waters into the upper layers is beneficial to coastal ecosystems. But in regions with acidifying waters, the infusion of cooler deep waters amplifies the existing acidification.

In the tropics, rising temperatures are slowing down winds and reducing the exchange of carbon between deep waters and surface waters. As a result, tropical waters are becoming increasingly stratified and more saturated with carbon dioxide. Lower layers then have less oxygen, a process known as deoxygenation.

Warming ocean temperatures have also caused a rapid increase of toxic algal blooms. Toxic algae produce domoic acid, a dangerous neurotoxin, that builds up in the bodies of shellfish and poses a risk to human health.

In coastal areas, such as Rhode Island, temperature changes can favor one organism over another, causing populations of one species of bacteria, algae, or fish to thrive and others to decline.

The sum of all these impacts is damaging to the Rhode Island economy. The state’s shellfish populations are already among the most vulnerable in the United States to the impacts of a warmer ocean.

Roger Warburton, Ph.D., is an ecoRI News contributor and a Newport resident. He can be reached at rdh.warburton@gmail.com.

Figure 1 was generated using data from the Copernicus Climate Change and Atmosphere Monitoring Services (2020). The ERA5 dataset is produced by the European Space Agency SST Climate Change Initiative based on global daily sea surface temperature data from the Group for High Resolution Sea Surface Temperature and made available by the Copernicus Climate Data Store.

Figure 2 was generated using data from NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental information, Climate at a Glance: Global Time Series.

A loving meal

Emeril Lagasse

“Anything made with love, bam! It’s a beautiful meal.’’

—Emeril Lagasse (born 1959), internationally known chef, TV host and restaurant entrepreneur. Born and raised in Fall River, his first big job was as executive chef of Dunfey’s Hyannis (Mass.) Resort, on Cape Cod.

David Warsh: Digital regulation is coming, sooner or later

Visualization of Internet routing paths.

—Graphic by The Opte Project

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

There are two ways of thinking about political prospects for the years ahead. One is to dwell on the relatively narrow margins of the recent presidential election – 80 million vs. 74 million votes cast, 306-232 in the Electoral College – and fear gridlock. The other is to look at America’s history of dealing with its problems and expect a series of further adjustments to be made, patterned on what’s been done before.

Take the problem of industrial concentration.

The government’s last big antitrust action came at the very dawn of the digital age: an unlawful monopolization charge under the Sherman Antitrust Act in the aftermath of the browser wars for having “smothered” a rival start-up, Netscape. The government won the case; and federal Judge Thomas Penfield Jackson ordered that Microsoft be split in two, one company selling operating systems, the other applications. The D.C. Court of Appeals overturned Jackson’s rulings and accused him of unethical conduct. The George W. Bush administration’s Justice Department announced that it would no longer seek to break up the company.

What has changed since then? Plenty. The shares of five large companies – Apple, Google, Microsoft, Facebook and Amazon make up nearly a quarter of the S&P 500 index, as EconoFact noted last week, in the course of surveying the legal landscape. The Justice Department and 11 states have sued Google, charging the company with abuse of its power.

The belief is growing that, whatever the conveniences of the Internet giants, there’s something about the structure of digital markets that means that they cannot be expected to self-correct. The most thoughtful proposal for government intervention I’ve seen is one prepared for a Report on Digital Platforms, commissioned by the Stigler Center for the Study of the Economy and the State at the University of Chicago’s Graduate School of Business.

There’s justice in this, it should be said. George Stigler was a pillar of the third Chicago School (1945–2014), a Nobel laureate, known for his decades-long rear-guard action against 20th Century ideas about market power. “It is virtually impossible to eliminate competition in economic life,” he wrote in his autobiography. Stigler died in 1991, the same year that the Internet was commercialized.

Fiona Scott Morton, of Yale University, chaired the study’s antitrust subcommittee. She served as Deputy Assistant Secretary for Economics in the Antitrust Division of the Justice Department in the Obama Administration.

At a conference in Chicago last year, Scott Morton presented the subcommittee’s 90-page findings in short, to-the-point remarks. Digital markets are quite different from most goods markets, she said. They are two-sided markets, serving at least two distinct user groups (readers or listeners and advertisers, for example), providing network effects to each. Economies of scale, of scope, and increasing returns to the possession of user data mean that such markets often “tip” at a certain point. The less successful drop out or are acquired and the winner takes all. Competition thus is often only for the market, not in it, Scott Morton said.

Three panelists discussed the report. Activist Matt Stoller, proprietor of the antitrust Web site Big, described a “world on fire,” and complained the recommendations lacked urgency. Ariel Eztrachi, of Oxford University, a member of the subcommittee, agreed. “No action is no longer an option. If we play for too long, we might find ourselves in a very different reality.” But Randal Picker, of the University of Chicago Law School, offered a jolt of the old-time religion.

When I took price theory from Gary Becker many years ago, Gary made clear that I needed to know two things to do economics. People optimize subject to constraints, and markets clear. That was all I really needed to know, and if I confronted a problem and thought I needed something more than that, I probably wasn’t thinking hard enough.

The subcommittee proposed two policy measures. A specialist competition court should be established to hear all private and public antitrust cases. That would allow judges to develop expertise in an area in which both behavioral and organizational economics have changed a great deal in the last 30 years.

A regulatory agency, a digital authority, should be created as well. Antitrust works well when agencies are quick to act and courts enforce the law well, said Scott Morton. “But even in the best world that’s not a complete solution. You need a partner to create a competitive environment.”

New technologies have traditionally brought into existence new regulatory agencies to help structure the new markets they created. The Interstate Commerce Commission was established to deal with the railroads (and later trucking). The Federal Communications Commission followed the radio industry into existence, and later came to oversee all kinds of communication. The Securities and Exchange Commission arrived not long after chicanery in the 1920s marred the beginnings of the democratization of finance.

Why not, then, enact a Digital Competition Commission, to provide a foil to the still-robust Sherman Antitrust Act? A new era of trust-busting may be in the offing. Digital regulation is coming, sooner or later, the subcommittee was saying. Why not start now?

David Warsh, an economic historian and a veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first appeared.

An all-accepting friend

—Photo by Lisa Sympson

A fluffy fellow in my lap

Continually purrs --

You may have heard him -- did you not

His purring joyful is --

He cares not if I'm rich or poor --

Or if I'm fat or slim --

Or if I’m tidy or unkempt --

Why can’t you be like him?

— Felicia Nimue Ackerman

This poem first appeared in The Emily Dickinson International Society Bulletin and is reprinted with permission.

“The Cat's Lunch ‘‘ (oil on canvas), by Marguerite Gérard (19th Century)

Ah, that skin-soothing lobster ‘blood’

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

“Two graduates of the University of Maine (UMaine) have developed a skin cream derived from lobster hemolymph, which functions within the lobster similarly to blood. The product can sooth such ailments as psoriasis and eczema.

“The product is the latest addition to items that can be traced back to efforts by the University of Maine (UMaine) to find commercial applications for byproducts of the commercial lobster industry. UMaine has worked for years to find additional uses for shells and other byproducts. Marin Skincare was founded by CEO Patrick Breeding and co-founder Amber Boutiette, who learned about the potential for lobster by-products while earning their master’s degrees at UMaine.

“Breeding and Boutiette are currently working with Luke’s Lobster in Saco, Maine, to collect hemolymph. The product has been available to consumers for over a month.

“The New England Council applauds UMaine for providing an innovative course of study encourage such scientific discoveries. Read more from the Bangor Daily News.’’

Jim Hightower: Turkey and Thanksgiving confusions

“The First Thanksgiving at Plymouth “ (1914), by Jennie Augusta Brownscombe, at the Pilgrim Hall Museum, Plymouth, Mass. If they ate turkeys, they would have been members of the Eastern Wild Turkey subspecies seen below.

Via OtherWords.org

Let’s talk about turkey!

No, not the Butterball now pouting in the Oval Office. I’m talking about the real thing — the big bird, 46 million of which Americans will devour on Thanksgiving.

It was the Aztecs who first domesticated the gallopavo, but leave it to the Spanish conquistadores to “foul-up” the bird’s origins.

The Spanish declared the turkey to be related to the peacock — wrong! They also thought that the peacock originated in Turkey – wrong again! And they thought that Turkey was in Africa. You can see the Spanish colonists were pretty confused.

Actually, the origin of Thanksgiving itself is similarly confused.

The popular assumption is that it was first celebrated by the Mayflower immigrants and the Wampanoag natives at Plymouth in what is now called Massachusetts, 1621. They feasted on venison, neyhom (Wampanoag for gobblers), eels, mussels, corn and beer.

But wait, say Virginians, the first precursor to our annual November food-a-palooza was not in Massachusetts — the Thanksgiving feast originated down in Jamestown colony, back in 1608.

Whoa, there, hold your horses, pilgrims. Folks in El Paso, Texas, say that it all began way out there in 1598, when Spanish settlers sat down with people of the Piro and Manso tribes, gave thanks, then feasted on roasted duck, geese and fish.

“Ha!” says a Florida group, asserting the very, very first Thanksgiving happened in 1565, when the Spanish settlers of St. Augustine and friends from the Timucuan tribe chowed down on cocido — a stew of salt pork, garbanzo beans, and garlic — washing it all down with red wine.

Wherever it began, and whatever the purists claim is “official,” Thanksgiving today is as multicultural as America. So let’s enjoy — even if we’re in smaller groups or observing virtually this year.

Kick back, give thanks we’re in a country with such ethnic richness, and dive into your turkey rellenos, moo-shu turkey, turkey falafel, barbecued turkey.

Jim Hightower is a columnist and public speaker.

Kindly light

“Eastern Point Light, 1940s’’ (watercolor on paper), by Alfred Levitt (1894-2000) at the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass.

Fresnel Lens for lighthouses originally designed by Augustine Jean Fresnel and displayed at the Cape Ann Museum.

Don Pesci: Biden and the pride of post-modern cultural Roman Catholics

VERNON, Conn.

Presumptive President-elect Joe Biden has let it be known throughout his half-century-long political career that he is a Kennedy Roman Catholic; in some quarters, Kennedy Catholicism is called cultural Catholicism.

Biden helpfully explained cultural Catholicism to Jack Jenkins, a reporter for Religion News Service (RNS). Hit this link to read it.

In it, Mr. Jenkins writes that “Joe Biden….was shaped by a very American Catholic faith: The way he manages his allegiance to Catholicism gives a glimpse of how Biden will govern as he takes hold of an office he has sought since 1988.’’

The piece lifts several quotes from Biden’s book Promises to Keep: On Life in Politics.

“I’m as much a cultural Catholic as I am a theological Catholic,” Biden wrote. “My idea of self, of family, of community, of the wider world comes straight from my religion. It’s not so much the Bible, the beatitudes, the Ten Commandments, the sacraments, or the prayers I learned. It’s the culture.”

Jenkins offers the following gloss: Cultural Catholicism is “a form of faith that experts," many of them cultural Catholics, "describe as profoundly Catholic in ways that resonate with millions of American believers: It offers solace in moments of anxiety or grief, can be rocked by long periods of spiritual wrestling and is more likely to be influenced by the quiet counsel of women in habits or one’s own conscience than the edicts of men in miters.”

One of the “men in miters” is, of course, the Pope.

John F. Kennedy, a Catholic running for president at a time when anti-Catholicism was still very much a force to be reckoned with – historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr., Kennedy’s chief biographer, characterized anti-Catholicism as the oldest prejudice in the United States – easily disposed of the notion that he would be the Pope’s cat’s-paw.

A month after Kennedy had met with a group of Protestant pastors, he traveled to Houston and there delivered a speech to a second group of pastors in which he said, “I believe in an America that is officially neither Catholic, Protestant nor Jewish; where no public official either requests or accepts instructions on public policy from the Pope.”

That distinction pretty much doused irrational fears that Kennedy as president would simply be an agent of the Vatican.

Since Kennedy’s day, many Catholics have served their country in various positions with distinction and fidelity both to their church and to the Constitution that they promised on oath to uphold. Catholicism, even the Catholicism of Popes, is not incompatible with patriotism.

Biden, Jenkins makes clear, likes the “culture” of Catholics, nuns and rosary beads, which he carries with him in his pocket. Cultural Catholicism, we are given to understand, is balanced in his thought processes with the theology of his church. The difficulty here is that there are among us cultural Catholics in open warfare against Catholic theology as explicated by the historic Roman Catholic Church, the Popes down through the ages, and leading Catholic clerics.

“Biden’s personal connection to the faith,” Jenkins notes, “remains a highly visible part of his political persona. He carries Rosary beads at all times, fingering it during moments of anxiety or crisis. When facing brain surgery after his short-lived presidential campaign in 1988, he reportedly asked his doctors if he could keep the beads under his pillow. Earlier this year, rival Pete Buttigieg noticed Biden holding Rosary beads backstage before a primary debate.”

Hilaire Belloc – author of the Road to Rome, a close friend of G.K. Chesterton and an unapologetic Catholic – also carried Rosary beads with him. One day, while campaigning for a seat in the British House of Commons, , he was accosted by a lady who shouted out to him from the crowd surrounding his campaign stump that he was a “papist.”

Belloc drew his Rosary beads from his pocket and said to the lady, “Madam, do you see these beads. I pray on them every night before I go to sleep, and every morning when I awake. And, if that offends you, madam, I pray God he will spare me the ignominy of representing you in Parliament.”

Unlike Biden, Belloc's rosary was more than a totem for him; it was the copula that linked him, both theologically and culturally, to the Catholic Church, ancient and modern, rolling through the years from Peter, the Rock against which the gates of Hell shall not prevail, to the sometimes twisted post-paganism of the post-modern 21st Century..

Kennedy’s sword of sundering has two cutting edges. The post-modern cultural Catholic suffers from inordinate pride; he really does think himself not only politically superior to popes, doubtful, but also superior to his church in matters of theology, faith and morals.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.