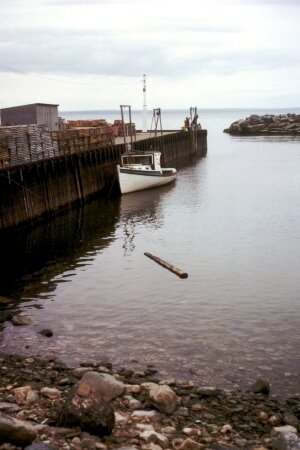

Then you're swallowed

— Photos by Samuel Wantman

“Maine is not a death cult. I mean, it is, but it’s a slow one. It creeps in like the tide, and without you even noticing, the ground around you is swallowed by water until it’s gone.’’

John Hodgman, in Vacationland: True Stories From Painful Beaches

Hospital efficiencies of scale and rich exiting execs

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The financial losses stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic will apparently speed up something that has often seemed inevitable over the past two decades, in fits and starts, for years: a merger of Rhode Island’s two big hospital groups – Lifespan and Care New England (CNE) – which include Brown University’s Warren Alpert Medical School teaching hospitals. The two groups have been swimming in deep red ink in recent years, which has only worsened in the pandemic, and so naturally they seek more efficiencies of scale, and to reduce wasteful redundancies, in Rhode Island’s health-care “system’’.

Such a merger, in creating a much more powerful entity, might keep the Ocean State’s health-care system out of the control of Boston-based hospital giants, particularly Mass General Brigham (formerly Partners HealthCare). But an unsettling question will be whether the new Rhode Island entity will use monopoly pricing power to jack up its prices, big time.

State regulators will have their hands full in dealing with such a behemoth. And it will be interesting to see the bright golden parachutes of hospital executives made redundant by the union of these “nonprofits’’ as the parachutes waft them down to the ground in, say, Palm Beach. Since Lifespan is bigger than CNE, and therefore would in effect be the purchaser, I assume that the execs of the latter would be more likely to go.

But then, there will probably be lots of layoffs of those with administrative jobs if the merger goes through, as seems very likely

On a happier side, a merger would probably strengthen Brown’s medical and public health schools, including their research capabilities, by uniting them with a stronger organization.

Still, given the size and fame of the medical center in Boston, only about 50 miles away, even the big new Rhode Island group will probably be hard-pressed to compete with “The Hub’’ in some specialties.

Mitchell Zimmerman: COVID crisis shows endless liar Trump only cares about Trump

Via OtherWords.org

“Captain,” said the first mate, “we just crashed into an iceberg — the hull’s been breached!”

“An iceberg. Deadly stuff,” said the captain. “Still, let’s play it down.”

“What are your orders? We must warn the passengers.”

“I’ll make an announcement… Attention all passengers, this is your captain speaking. We’ve encountered some ice, but we have it very well under control. We’re doing a great job. No need for you to change your routines. Over and out.”

“Should we ready the lifeboats?” asked the mate.

“Nah. Let’s just show confidence. I don’t want to create a panic.”

The deceiving and self-flattering captain of the scenario, leading his passengers into disaster, seems fictitious. But he’s all too real: except for the references to ice, everything the captain says above are things that President Trump has actually said about COVID-19.

Tragically, that’s America in the age of pandemic. Over 6.5 million cases of coronavirus. Around a thousand deaths per day. An economy in ruins.

But Captain Trump is still at the helm — and Americans are still needlessly dying — because he still prefers “playing it down” to uniting us behind the tough but necessary measures that are called for.

For months, Trump urged resistance to the precautions epidemiologists recommended, crusaded against the lockdown, and minimized the lethal threat, even claiming the coronavirus was “totally harmless” in 99 percent of cases.

He knew this was false: “This is deadly stuff,” he privately told journalist Bob Woodward in February.

Even as Trump publicly ridiculed the use of masks and encouraged followers to defy social distancing, he knew the virus was spread through the air. “It goes through air,” he told Woodward. “You just breathe the air and that’s how it’s passed.”

Trump claimed publicly that coronavirus was “like the regular flu,” but he told Woodward that he knew otherwise. It’s “more deadly than even your strenuous flu,” Trump told the journalist — more than five times as deadly.

Trump and his falsehoods are responsible for most of America’s 200,000 coronavirus deaths to date. How could it be otherwise? How could anyone think thwarting the epidemic response prescribed by doctors, scientists, and public health leaders would not have deadly consequences?

Turn back to January.

A dozen presidential briefings warned Trump of the coming pandemic. The Health and Human Services Department secretary twice told Trump the contagion was looming. Trump’s trade adviser wrote a memo in January warning of a “full-blown pandemic, imperiling the lives of millions of Americans.”

Trump claims he refused to act because he feared panic.

Avoiding panic is all very well. But if you’re telling passengers they don’t need to get in the lifeboats, you’re responsible when they start drowning. In reality, Trump cared more about not “panicking [the stock] market” — which he saw as key to his re-election — than about the lives that would be lost.

By late February a White House task force recommended aggressive steps, including stay-at-home orders. But when a Centers for Disease Control leader warned the public that a pandemic was imminent and “disruption to everyday life might be severe,” Trump threatened to fire her.

“The risk to the American people remains very low,” Trump proclaimed instead.

It was mid-March before Trump yielded to reality.

The cost of Trump’s delay? Columbia University epidemiologists concluded in May that had the lockdowns begun just two weeks earlier, “the vast majority of the nation’s deaths — about 83 percent — would have been avoided.”

But they weren’t. And the 1 million people who were needlessly infected, thanks to Trump’s indifference, then went on to infect others, and those in turn still others. Meanwhile the president kept up his campaign against the steps needed to bring the pandemic under control.

No precise reckoning is possible, but there’s no doubt a majority of our cases and deaths might have been avoided but for Trump’s lies, neglect, and sabotage.

Mitchell Zimmerman is an attorney, longtime social activist, and author of the anti-racism thriller Mississippi Reckoning.

Colors of summer and fall, too

"Thermos Cluster," by Jill Pottle, in the group show “Colors of Summer Memories,’’ at Fountain Street Fine Art, Boston, and curated by Marygrace Gladden

The gallery says the show “encourages the viewer to recall the emotions and feelings of summer. The season is often associated with warm colors as the temperatures rise and the sun shines differently than any other time of year. Summer of 2020 has led to a halt in normality as the pandemic stopped many seasonal activities that would have been taking place. COVID-19 has society spending their summers in new ways with many people spending more time at home, in their personal spaces. For some, being confined to their home led to renovations as well as new discoveries within the interior spaces in which they inhabit. The warm summer colors, along with the unique familiarity of our homes at this time have created summer memories that will remain at arm's length as the winter months draw near.’’

See:

https://www.fsfaboston.com/

Chris Powell: Postal Service realities; bring back postal banking?

The Littleton (N.H.) Main Post office, opened in 1933. It’s surprisingly grand for a town with only about 6,000 residents. It’s on the National Registry of Historic Places.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Maybe someday when the United States has a president who is not crazy or senile, a Senate majority leader who isn't his tool, and a House speaker who doesn't think that those who disagree with her are enemies of the state, the country can have a serious discussion about fixing the U.S. Postal Service.

President Trump recently suggested that he wanted to cut off money for the Postal Service to hamper the voting by mail desired by Democratic leaders. The postmaster general, a big donor to the president's campaign who is invested in companies that compete with the USPS, had ordered economy measures that raised suspicion about his motives. But he has postponed those measures until after the election.

Since throwing fantastic amounts of money at everything has become national policy, the other day the Democratic majority in the House passed an emergency appropriation of $25 billion for the Postal Service with barely a thought about the service's inefficiencies and potential.

Just as the president seems to want to weaken the USPS for partisan reasons, the Democrats seem to want to keep it operating just as it is because it employs about 600,000 people, most of them belonging to a union that supports Democrats. In the Democratic view, delivering the mail efficiently seems to be secondary.

The Postal Service long has been losing big money. It has not come close to covering its costs for the last 13 years, during which its losses have totaled $78 billion. Its unfunded pension and retirement medical insurance liabilities are worse.

In 1971 the USPS was taken out of the regular government and made a supposedly independent agency in the hope that regular business practices would be applied and improve efficiency. But this didn't accomplish much. Mainly postage prices rose as government's direct subsidies were withdrawn, and the Postal Service's financial position worsened.

{Editor’s note. Much of the Postal Service’s financial woes stem from a 2006 law passed by the Republican-run Congress in a lame-duck session that mandated that the USPS pre-fund its employee-pension and retirement costs, including health care, not just for one year but for the next 75 years—a crippling requirement not imposed any other enterprise. The year that mandate passed, the Postal Service had a $900 million profit.}

Customer services have been expanded but mail volume has fallen sharply, first because of the Internet and lately because of the virus epidemic, so the Postal Service doesn't make full use of its vast infrastructure.

Its defenders, mainly Democrats, note that the USPS was never supposed to earn a profit but to knit the country together. It has done that well. But some of its defenders imply that because it wasn't meant to make money, it's all right for it to lose any amount of money -- that its primary purpose now is not delivering the mail but employment and that postal employment is the best use of the money being spent to cover losses.

Republicans are suspected of wanting to privatize the Postal Service or cripple it by repealing its monopoly on delivery of first-class mail. Certainly private companies might do better with such mail in some respects, but the law requires the USPS to serve all people in the country at the same rates -- to make not just the less expensive deliveries of densely populated areas but the more expensive deliveries in the remote countryside. The Postal Service is a great gift to rural areas, the country's breadbasket.

Urban areas also might find the USPS more of a gift if postal banking was restored. From 1911 to 1967 the Postal Service office offered modest savings accounts. While their appeal diminished with federal bank deposit insurance, which came because of the Great Depression, the Postal Service still sells money orders and might offer not just savings accounts again but also basic banking services to poor people whose patronage commercial banks find unprofitable and who use expensive payday lenders and check-cashing services.

Of course, the Postal Service probably would not break even in the banking business either, but helping the poor save and learn banking would elevate them and give commercial banks some much-needed competition.

In any case the USPS has a big underused infrastructure even as it still knits the country together. But like nearly everything else in government, its employment costs are excessive. If actual governing ever resumes in Washington, improving the Postal Service while making it break even should be high on the agenda.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.

Breakthrough on Nantucket

Post office in the Nantucket village of Siasconset, on the eastern end of the town/island. Nicknamed “Sconset,’’ it’s where Alice Killer spent a few cold-weather months in 1962-63 as she sought to better understand herself and change her life.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Philosopher, with a PhD, and writer (mostly as a kind of memoirist) Alice Koller, who died July 21 at 94, was the author of two books that continue to have a following. These are An Unknown Woman and The Stations of Solitude. Parts of them recall, slightly, Thoreau’s Walden.

Ms. Koller may have often been an impossible person to be around for long. And so her painfully reached decision, in lieu of the suicide she considered, to hereafter live, but alone, and stop wasting time and energy trying to meet her own outdated or false expectations, and those of others, was good for all concerned. She came to the decision in winter of 1962-63 while living alone, except for her German Shepherd puppy, on the easternmost shore of Nantucket, an experience that’s the core of An Unknown Woman. That dog, Logos, and her two other dogs that followed played key roles in her life, becoming her family.

Her rigorous self-analysis as she explored the sources of her misery has lessons for everybody seeking to live with more integrity, independence and creativity, though few will want to emulate her life, which had much poverty and other challenges, some caused by things out of her control and some by her own eccentricity and willfulness. Oddly, her self-involvement doesn’t come across as narcissism but rather as honest, hard-working attempts, informed by curiosity, to come to terms with the reality of her past and present.

Ms. Koller was also a fine writer about nature – the landscapes, creatures and weather -- in the various places she lived, from the moors and beaches of Nantucket to the woodsy exurban towns where she mostly lived afterwards.

One of “Sconset’s’’ old cottages. At least one of them dates back to the late 17th Century.

Liminality and simultaneity

“Consumed Structure With Road III,’’ by Denny Moers, in his monoprint show “Within a Liminal Space,’’ at Periphery Space @ Paper Nautilus, Providence, through Nov. 1.

The gallery says:

“‘Within a Liminal Space’ explores the tension between the known and the unknown. From the Latin root limen, meaning threshold, liminal is a transitional place separating the familiar from the unrecognizable. This area can be uncomfortable for many, but it is an area that artists know intimately. Whereas some photographers might anxiously move the paper in the chemical bath, anticipating the images they think will appear, Moers thrives in this space, embracing the process, accepting the uncertainty.

“Looking at Moers's photographs as liminality, another word comes to mind – simultaneity. The hazy, mirage-like images in contrast with a hard edge of color remind me of a past I can't quite bring into focus and a future that is sharply taking shape. He shows us a road that shines slick with color in the foreground while the trees and barn in the background are seen in black and white as nature envelopes them. These images are intriguing and mysterious, full of meaning, waiting to be understood.’’

David Warsh: Time to build new public data infrastructure

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

“Philosophy? Philosophy? I’m a Christian and Democrat — that’s all.’’ Franklin D. Roosevelt responding to the question “What is your philosophy?” as quoted in Freedom From Fear: The American People in Depression and War 1929-1945, by David Kennedy.

It’s a commonplace that every new presidential administration arrives as a policy omnibus, with all kinds of venturesome policy entrepreneurs aboard. Campaign managers, financial backers, friends of the president and vice president, Cabinet members, Congressional committee chairpersons and their staffers, lobbyists, opinion shapers in the media – all bring agendas and, in the pell-mell of the first hundred days, seek to put them in motion.

It will be decades before we know what the Trump presidency was all about. But Biden, if he wins, will take office, with only one certainty. The Democrats will once again be the party of Innovation. Starting with candidate Barry Goldwater in 1964, the Republican Party managed to wrest away the mantle of change: deregulation, globalization, supply-side economics, all that. But after the monumental stumble that has been the Trump presidency, the GOP must rebuild itself as the party of conservatism or go out of business.

Trump himself may have arrived with a headful of ideas, but in the event he is defeated after a single term he is headed for obloquy greater than that of Herbert Hoover as a president who didn’t show up. Should Trump win a second term, of course, that’s another story.

Green New Deal? Tax restructuring? Pandemic crisis management? Health care and Social Security repair? Immigration status reform? Supreme Court appointments? Which of a thousand possibilities will blossom into fact? There is no way of knowing today. As a gauge of the Biden administration’s long-term success, however, consider a modest suggestion. What about commissioning a National Data Service to stand with the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Air Force, Coast Guard, Space Force, Public Health Service and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, as the nation’s ninth uniformed officer corps?

The pre-history of the Space Force is instructive. As far back as 1961, then Defense Secretary Robert McNamara designated the Air Force as the lead military service for space. But not until 1982 was an Air Force Space Command created, in connection with the Reagan administration’s Strategic Defense Initiative, a satellite-based laser weapons system abandoned after some testing. Satellite reconnaissance became part of the War on Terror after 9/11. And in March 2018, President Trump embraced the independent Space Corps idea in a public speech. He signed a statute in December 2019 establishing it. Around 16,000 active-duty Air Force personnel and civilians are assigned to it.

Public data collection in the United States is a much older service. Article I, Section 2 of the Constitution requires the enumeration of the nation’s population for purposes of establishing representation in Congress. The first Census was conducted in 1790, and at ten-year intervals ever since. New statistical agencies were added as needs arose, for banking, agriculture, labor, safety, manufacturing, transportation, health, medicine, and so on. When the War Department (as what is now the Defense Department was previously called) needed planning data for World War II, the Commerce Department turned to the National Bureau for Economic Research, where Simon Kuznets was developing National Income Accounts. Most countries have a single statistical agency; the U.S. has 13 major agencies and hundreds of smaller programs.

The current system has needed an overhaul since the mid-1990s, when Janet Norwood, then Commissioner of the Bureau of Labor Statistics, wrote Organizing to Count: Change in the Federal Statistical System. Today it is judged to be broken. Old-fashioned survey techniques are outdated in the age of the Internet. Concerns for privacy and confidentiality have sent costs soaring. The 2020 Census is expected to cost $48 a head to collect in constant dollars, as opposed to $5.50 in 1960. And political meddling has become a problem in the last four years. Manipulation of pandemic statistics has made headlines in recent months. And, having failed to exclude non-citizens by requiring them to identify themselves as such, the Trump administration decided to end the Census four weeks early, in August.

A high-level blueprint for building a new public data infrastructure appeared over the summer. Democratizing Our Data: A Manifesto (MIT Press), by Julia Lane, of New York University. A native New Zealander, now a U.S. and U.K. citizen as well, Lane earned a PhD from the University of Missouri in the 1980s, taught, worked for the World Bank for a decade, taught again for another 10 years at American University, managed the economics department at the University of Chicago’s National Opinion Research Center, and rotated through four years at the National Science Foundation as a senior program director. She subsequently founded a series of programs for the American Institutes for Research, and eventually the Coleridge Initiative, a rapidly growing research and training collaborative, before settling down as a high-end professor at New York University’s Wagner School of Public Policy. “It’s a golden moment,” she writes, to rethink the system, retaining its best aspects – trust, professionalization, continuity – while designing new systems of measurement, putting them to work, and making them widely available

Will it happen? It’s a long road, a matter for experts backed by diverse constituencies in government and private enterprise. But if ever a highly technical program was worth setting out, manifesto-fashion, in a short and readable book, it is this one. An age of Big Data is upon us. Shouldn’t a government run by a Party of Innovation bend to the task of creating a National Data Service?

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

More than basic black

“After the Storm” (acrylic on canvas), by Tim Forbes, in his show “NOIR: Works on Canvas & Paper,’’ at Lanoue Gallery, Boston, through Oct. 11. He’s based in Blue Rocks, Nova Scotia. (See below.) Hit these links:

lanouegallery.com

and

https://lanouegallery.com/artist/Tim_Forbes/biography/

Suresh Garimella: UVM's role in helping Vermont recover from COVID crisis

Named for U.S. Sen. Justin Smith Morrill, Morrill Hall at the University of Vermont was built in 1906-07 as the home of the UVM Agriculture Department and Agricultural Experiment Station.

Via The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BURL.INGTON, Vt.

Gracing the back wall of my office at the University of Vermont is an antique wooden desk that’s more than 150 years old. While it’s an undeniably handsome piece of 19th Century craftmanship, it serves much more than a decorative purpose.

As the desk of Vermont Sen. Justin Smith Morrill, the author of the Morrill Act of 1862, which established the country’s first land-grant universities, it is my lodestar, a vivid reminder of UVM’s status as one of the nation’s earliest land grants and of the solemn responsibilities that come with that designation.

Count me as a true believer in the land-grant mission and among its greatest fans. The first land grants, so called because the U.S. government donated federal land to each state to establish a university, were a brand new idea: higher education for everyday people focused on the practical subjects of agriculture and the mechanical arts, whose purpose was to improve the economic and cultural well being of the people in their state.

Why am I so passionate about UVM’s land-grant mission? Because Vermont, as much as any state in the nation, faces a series of daunting challenges—from population decline to stagnant economic growth—that a land-grant university like UVM is powerfully equipped to address.

In the middle of a pandemic that has rendered these challenges even more acute, there is another reason to believe in the land-grant mission. Land grants like UVM have a key role to play in helping their states recover economically from the ravages of COVID-19.

The economic impacts of the pandemic are indeed unprecedented. In the second quarter of 2020, the national economy shrank at an annualized rate of nearly one-third. Millions of jobs were lost in New England. And in Vermont, despite the state’s lowest-in-the-nation infection rate, unemployment in July was 8.3 percent, and the state has the highest budget deficit in its history.

How can land-grant universities help spur economic recovery in their states? In Vermont, we’re looking at bringing the power of the university to bear on these challenges in a number of ways.

We’ll take full advantage of one of UVM’s most important resources: our bright and capable students. In a post-COVID economy, employers—from tech firms to media companies to nonprofits—will be in dire need of eager-to-learn, dependable, qualified employees. To meet this need, we’ll significantly enhance our internship programs, so more students, beginning in their first year, can be exposed to career options in the state by interning with a Vermont employer. Just as important, we plan an active outreach and education campaign to employers, so they know how to connect with and engage our talented students.

We’ll harness the strength of another great university resource: the talents of our faculty, who last year brought over $180 million in research funding to the university. In the coming months, with support from our faculty, we will help businesses around the state apply for federal Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) grants, proven ways to help businesses grow.

We plan a concerted and sustained effort to attract our out-of-state alumni, a high percentage of whom are entrepreneurs, back to Vermont, a state they love, providing them with technical assistance so they can relocate their companies, envision new ways of working from home or start new businesses here.

We’ll mobilize the intellectual firepower of our faculty to help policymakers craft local and state programs that address socioeconomic challenges the state is facing, which hold back wellbeing and prosperity. In a survey of food insecurity in the state, for instance, faculty learned that some Vermont residents were stockpiling food and depriving those in need—a problem that informed policy can alleviate.

We’ll deploy the pedagogical and human development expertise of faculty in our College of Education and Social Services to help Vermont’s K-12 teachers better engage primary school students as they emerge from a remote learning environment and better understand how distance learning, enhanced internship and place-based learning opportunities can help keep college-bound high school students on track.

For many of these efforts, we’ll coordinate with UVM Extension. In an expansion of their traditional role, Extension faculty and staff will act as our on-the-ground implementation agents for community economic development.

As important as these programs are in spurring economic recovery, their impact would be muted without another initiative just funded by the state: UVM’s new Office of Engagement.

The office will function as the front door to the university, with staff who field inquiries from businesses and residents across the state, connecting them with appropriate resources and expertise at UVM.

While the university has a critical role to play in Vermont’s post-COVID recovery, its role in promoting the state’s well being stretches far beyond the current crisis.

Boosting the health, quality of life and prosperity of Vermont and Vermonters is one of the three core imperatives in the university’s recently released strategic vision, Amplifying Our Impact.

The strategic vision continues UVM’s long tradition of engagement with the state. During my tenure, we will become even more deeply engaged with issues of concern throughout Vermont.

The historic wooden desk I keep close by will continue to inspire me. With the help of this daily reminder, I will ensure that UVM’s land-grant mission—to help the state confront both our current challenges and those to come, shaping a bright future for all Vermonters—remains a top priority for Vermont’s university.

Suresh Garimella is president of the University of Vermont.

UVM seal

'Meant to be'

“When fall comes to New England

And the wind blows off the sea

Swallows fly in a perfect sky

And the world was meant to be.’’

— From song “When Fall Comes to New England,’’ by Cheryl Wheeler

'Summer people and lobsters'

Old Orchard Beach, Maine, long a favorite resort area for French Canadians, but not this year.

“As a child of Maine, he knew better than to learn to swim; the Maine water, in Wilbur Larch’s opinion, was for summer people and lobsters.’’

From John Irving’s Cider House Rules (1985)

Finally out of the house

“September smiled at her wonderful friends in all their colors and bright eyes and gentle ways. “You know, in Fairyland-Above they said that the underworld was full of devils and dragons. But it isn’t so at all! Folk are just folk, wherever you go, and it’s only a nasty sort of person who thinks a body’s a devil just because they come from another country and have different notions.”

― Catherynne M. Valente

Photo by Fiona Gerety, Wickenden Street, Providence, RI.

September 13, 2020

'The world itself'

“The most beautiful thing in the world is, of course, the world itself.’’

— Wallace Stevens (1879-1955), Hartford-based poet, lawyer and insurance executive

Mr. Stevens enjoyed wandering in Elizabeth Park. With more than a hundred acres of gardens, lawns, greenhouses and a pond, the park often appeared in his poems, including "The Plain Sense of Things," which includes the lines:

“Yet the absence of the imagination had

Itself to be imagined. The great pond,

The plain sense of it, without reflection, leaves,

mud, water like dirty glass, expressing silence…’’

— Photo by Ragesoss

The Rose Garden at Elizabeth Park in West Hartford, Conn., with a greenhouse in the background on the left. Part of the park is in Hartford.

Shall not perish from the Earth

New England clam chowder

“Alas, what crimes have been committed in the name of chowder! Dainty chintz-draped tea rooms, charity bazaars, church suppers, summer hotels, canning factories — all have shamelessly travestied one of America’s noblest institutions, yet while clams and onions last, the chowder shall not die.’’

— Louis P. Gouy, in The Gold Cook Book (1970)

Roll with the chaos

“What you find coming through” (gouache, India ink, walnut ink, soft pastel, coffee, colored pencil, graphite, watercolor, Rives BFK paper, acrylic ink and paint), by Max Van Pelt, in his show “Tendency,’’ at Cade Tompkins Projects, Providence, through Nov. 14.

'Dry shake of our steps'

“The Starry Night’’ (1889), by Vincent Van Gogh

“We walk tonight

in the valley of our bones.

Here no skin is stretched

on hollow wood,

no song except

the dry shake of our steps.’’

— From “The People Cannot Speak,’’ by T. Alan Broughton (1936-2013), American poet and pianist. He taught writing at the University of Vermont in 1966-2001.

The Devil's 'restraining machine'

“One of the earliest institutions in every New England community was a pair of stocks. The first public building was a meeting-house, but often before any house of God was builded, the Devil got his restraining machine.’’

— Alice Morse Earle (1851-1911), historian. Her writing focused on small sociological details and became invaluable for some 20th Century social historians. She wrote books on Colonial America (and especially New England ), such as Curious Punishments of Bygone Days.

Only by invitation

“House Party” (collage), by Betsy Silverman, at Edgewater Gallery, Middlebury, Vt.

Llewellyn King: 'Job retraining' can be an empty slogan without aptitude

Computer skills training

WEST WARWICK ,R.I.

When a vaccine for COVID-19 is as easily available as a flu shot, and when the public is comfortable getting it, it will be a time of victory -- Victory Virus. And it will be a time to begin building the new America.

Things will have changed. We won’t be going back to the future. Most visible will be the disappearance of a huge number of low-end jobs. No one knows how many but, sadly, we have a good idea where it will hurt most: among semi-skilled and unskilled workers.

They are those who don’t have college degrees and those who wouldn’t have qualified to enter college. Higher education isn’t for everyone, even if money wasn’t an issue. College is for those who can handle it, therefore benefiting.

It isn’t only the virus that is changing the employment picture but also the continuing technology revolution. Data is going to be king, according to Andres Carvallo, founder of CMG, the Austin-based technology consulting company, and a professor at Texas State University. Data, he argues, linked with the spreading fifth-generation telephone networks (5G) will delineate the future. Carvallo has pointed out that data from all sources have value, “even the homeless.”

Carvallo’s colleague on a weekly video broadcast about the digital future, entrepreneur John Butler, a University of Texas at Austin professor, believes that data and 5G will start to affect American business in a big way and new business plans will emerge, taking into account the increasing deployment of sensors and the ability of 5G to move huge quantities of data at the speed of light.

Carvallo explains, “If you’re moving data at the rate of 40 megabytes per second now, with 5G you’ll be able to move it at 1,000 megabytes per second.”

The technology revolution will continue apace, but will there be a place for those who aren’t embraced by it, like those who serve, clean, pack, unpack, and have been doing society’s housekeeping at the minimum wage or just above it?

Evidence is that they are already in sorry shape with a much higher rate of COVID-19 infections than the general population, and even in the best of times they have poorer health — an indictment of our health system.

The future of the neediest workers is imperiled, in the short term, because the jobs they have had and the jobs that have always been there for those on the lower ladders of employment are disappearing. A goodly chunk of these workers will be out of work for a long time.

Retraining is the solution that is advocated by those who aren’t caught in this low-level work vise. Retraining for most people is, to my mind, just a crock. It is a bromide handed down by the middle class to those below; a callow concept that doesn’t fit the bill. It soothes the well-heeled conscience.

First, some people can’t grasp new concepts, particularly as they age. Are you really going to teach a middle-aged, short-order cook to navigate computer repair? That is not only impractical, it is cruel.

A further disadvantage is that the affected workers not only are going to be shut out of their traditional lines of employment, but they also carry an additional burden, another barrier to retraining: They almost exclusively are the products of shoddy public education, so there is very little to build on if you’re going to retrain. If you have marginal English most information technology work is going to be inaccessible; rudimentary math is another stumbling block.

Very smart people are candidates for retraining. The graduate schools see plenty of students who get multiple, disassociated degrees, like lawyers who have nuclear engineering degrees. I know a prominent head of surgery at a Boston hospital who has a degree in chemical engineering.

They are the polymaths, but they aren’t laboring for the minimum wage.

The loss of jobs due to COVID-19 comes at a time when technology, for the first time since the Newcomen engine kickstarted the Industrial Revolution in 1712, might be a job subtractor, not the multiplier it has been down through the ages.

Unemployment insurance is a stopgap but it also obscures the full extent of the skill void, the aptitude hurdle.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His e-mail address is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Website: whchronicle.com