A seasonally drunken cow

Applecrest Farm Orchards, which started in 1913 and is open year round, is in Hampton Falls, N.H. It is considered the oldest and largest apple orchard in New Hampshire. Indeed, some assert that it’s the oldest continuously operated commercial apple orchard in the United States.

Something inspires the only cow of late

To make no more of a wall than an open gate,

And think no more of wall-builders than fools.

Her face is flecked with pomace and she drools

A cider syrup. Having tasted fruit,

She scorns a pasture withering to the root.

She runs from tree to tree where lie and sweeten

The windfalls spiked with stubble and worm-eaten.

She leaves them bitten when she has to fly.

She bellows on a knoll against the sky.

Her udder shrivels and the milk goes dry.

— “The Cow in Apple Time,’’ by Robert Frost (1878-1963)

A very orderly elegance

“Fifties Fashion for All’’ (encaustic painting with paper dress patterns), by Nancy Whitcomb. Fashion now seems focused on face masks.

The business of fending off controversy

Allie’s in the cool season

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Businesses, especially small ones, are usually better off avoiding politics. Allie’s, the well-known North Kingstown, R.I., donut shop, may have learned this in the past few months.

For a long time, it gave discounts to police officers (to be nice and presumably tending to ensure that it got better service if problems arose with nasty patrons, etc.) and military members. But when the Black Lives Matter campaign started to get massive attention with the police killing of George Floyd, the shop rescinded the discounts.

Then came the heavily televised demonstrations (a few of which became riots) in some cities against police violence on Black people that also drew in the vague leftist blob called “Antifa’’ and far-right folks in a few cities. This outraged some Allie’s customers, especially Trump backers, of whom there are plenty in parts of suburban and exurban Rhode Island. And so the shop has decided to hand out free donuts to customers who promised to hand them to police officers.

The shop’s actions show it with a finger in the air, trying to figure out what action will be the most popular or at least the least unpopular. I’m sympathetic! But they’ve now managed to alienate pretty much everyone with their gyrations. Still, the publicity has probably been good for business.

It’s all up to Allie’s, of course, but I think that the shop should treat the police like any other customers. We love them, of course, but officers don’t need the savings; they are well compensated and retire early with big pensions and benefits. They don’t need discounted or free donuts, a delicious food that’s not exactly healthy, especially for people with heart disease, obesity and diabetes – which is much of the population.

Iceland's 'light caresses the landscape'

"Fjord" (triptych), (fiber), by Agusta Agustsson, in her show “Northern Light,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, Nov. 6-29.

The Melrose, Mass.-based artist says:

“Beyond the Northern Lights the light in my native Iceland is special. Colors are brighter. Even on an overcast day (of which there are many) the light caresses the landscape. The landscape is like nowhere else on earth. Volcanic cliffs march into the sea. Great gouges appear out of nowhere. Glaciers grind the rock beneath their massive weight. Strange shapes hide in the lava fields. Gouts of steam and boiling water spout from fissures in the earth. The land is painfully new.’’

The Gazebo at Ell Pond Park, Melrose

Photo by Elizabeth B. Thomsen

David Warsh: Why Russia invaded our 2016 election, and they're at it again

Vladimir Putin pushing hard to keep Donald Trump in power.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The Russian government meddled in the 2016 U.S. presidential election in a variety of ways. Most consequential were the thefts of Democratic National Committee emails and their publication by WikiLeaks. Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation documented the interference. A bipartisan Senate Intelligence Committee report confirmed it. No serious person doubts that the Russian campaign occurred, though few believe it tipped the election. And no serious person, except Wall Street Journal columnist Holman Jenkins, Jr., has attempted to dismiss it as a trivial matter.

“I was not shocked and still am not,” Jenkins wrote last month. “Since Czarist times, the Russian government has played such games, and was hardly going to adopt a self-denying ordinance now that the Internet was making them costless and effortless.”

A more knowledgeable account of the background to the Russian monkey business is to be found in The Back Channel: A Memoir of American Diplomacy and the Case for Its Renewal (Random House, 2019), by William Burns, former ambassador to Russia (2005-08) and deputy secretary of state (2011-14). Burns is currently president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, and not to be confused with Nicholas Burns, a former ambassador to NATO (2001-05) and undersecretary of state for Political Affairs (2005-08), who is today a professor of practice at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government.

The formal end of the Cold War was engineered mainly by Secretary of State James Baker, who, in less than a year after the fall of the Berlin Wall, negotiated Germany’s reunification as a member of NATO, in October 1990. He convinced Soviet leaders that they would be safer with Germany inside the alliance than outside of it, free to acquire nuclear weapon. In talks with Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze, Baker promised that NATO would not expand “one inch to the east” of Germany’s borders in the years ahead.

But Baker made the pledge before the breakup of the Soviet Union, in December 1991. Its leaders failed to get it in writing. Bill Clinton won the 1992 election and, at the urging of Poland, Hungary and what was then Czechoslovakia began NATO enlargement soon thereafter. Defense Secretary William Perry and strategist George Kennan warned of a fateful mistake in the offing; the Moscow embassy advised that “hostility to expansion is almost universally felt across the political spectrum.” Clinton waited until Russian President Boris Yeltsin and he had been re-elected, in 1996, then went ahead.

NATO’s intervention against Serbia in Kosovo, in 1999, left an especially bitter taste, with U.S. jets bombing Belgrade and a tense confrontation between Russian and NATO forces on the ground defused at the last moment. Putin was appointed president of Russia in 1999 and elected the next year. George W. Bush was elected in 2000, and, for a little while, the mood was optimistic. After 9/11, Putin’s hopes for a common front against terrorism, with Russian backing of the U.S. in Afghanistan and Washington supporting Moscow’s measures against Chechen rebels, were dashed (William Burns is especially good on why the U.S. declined), and Bush went ahead with plans to admit seven more Eastern European nations to NATO, including Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, former parts of the USSR. He barely mentions the second wave of expansion, which took place during NATO Ambassador Nicholas Burns’s watch.)

In 2003. Putin sought without success to persuade Bush not to invade Iraq, but it was the U.S. failure to share information about a pending Chechen hostage-taking at a Russia school, according to Burns, that was a turning point in Putin’s view of the possibilities,. The raid ended with 394 deaths and dramatically altered Russia’s internal politics. In a speech in Munich, in 2007, Putin denounced the United States for “having overstepped its national borders in every way.”

In 2008 Putin warned Bush, in no uncertain terms, via Ambassador Burns, against broaching NATO membership for Ukraine. “There could be no doubt that Putin would fight back hard against any steps in the direction of membership” for either Georgia or Ukraine, Burns writes. In August, Russia undertook a walkover war against a secessionist province of Georgia. In the shadow of a growing financial crisis in the West, it was barely noticed. In 2014. U.S,. support for a 2014 Ukraine uprising aimed at joining the European Union instead of a Russian-backed economic alliance proved the breaking point.

Burns sums up his view of the history this way:

The expansion of NATO membership stayed on autopilot as a matter of U.S. policy long after its fundamental assumptions should have been reassessed. Commitments originally meant to reflect interests morphed into interests themselves and the door cracked open to membership for Georgia and Ukraine – the latter a bright red line for any Russian leadership. A Putin regime pumped up by years of high energy prices pushed back hard And even after Putin’s ruthless annexation of Crimea [in 2014] it proved difficult to imagine that he would stretch his score-settling into a systematic assault in the 2016 presidential election.

(I wrote a small book about all this, Because They Could: The Harvard-Russia Scandal (and NATO Expansion) after Twenty-Five Years (KDP, 2017). In The Marshall Plan: Dawn of the Cold War (Simon & Schuster, 2018), Benn Steil explained Russian dismay as arising from history and geography, not ideology.)

Why did Putin authorize the campaign? In Alter Egos: Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama, and the Twilight Struggle over American Power (Random House, 2016), veteran New York Times correspondent Mark Landler documented the animosity between Hillary Clinton and the Russian leader. It grew after, as secretary of state, Clinton engineered NATO’s 2011 intervention in Libya; deepened considerably when Putin accused her of interfering in his 2012 campaign for re-election to a third presidential term; and achieved new heights after demonstrations caused Ukraine’s president, a loyal ally, (and hopeless crook, let it be said) to flee to Moscow. Clinton was running for president by then. Passing out cookies to demonstrators in Kiev’s central square (and phoning instructions to the American embassy) was Clinton’s former spokesperson, Victoria Nuland, by then serving as under secretary of state for European and Eurasian Affairs.

What did Putin expect to happen in the unlikely event that Trump won? Clearly the former KGB officer, who served abroad only in Germany before the Soviet Union came apart, doesn’t understand American society or politics very well. In May 2017 he secretly proposed through embassy channels an elaborate reset of relations, including digital-warfare-limitations talks. John Hudson’s story of the overture didn’t receive the degree of attention and elaboration that it deserved, presumably because Hudson was working for BuzzFeed at the time. Today he covers national security and the State Department for The Washington Post.

Since its annexation of Crimea and subsequent support for low-level war in eastern Ukraine, Russia has seemed to revert to its old ways. An “imitation democracy” at home. Arrest or murder or attempted murder in Russia of Putin’s critics. State-sponsored assassinations of enemies abroad, in London, Berlin, Salisbury, England. Digital meddling in other nations’ affairs wherever it pleases, All of this blandly denied, and punctuated by regular claims of technological breakthroughs: hypersonic torpedoes and the first effective COVID-19 vaccine.

In Russia Without Putin: Money, Power, and the Myths of the New Cold War (Verso, 2018), journalist Tony Wood writes that such an account is unfair, ignoring the ways in which the West’s own actions have shaped Russia’s decisions. After 1991, Wood writes, the Russian elite tended to see the country’s future as lying “either alongside or within” the G-8. Pro-Western sentiment started with Gorbachev and Yeltsin, but continued with Putin and [one-term President Dimitry] Medvedev much longer than is assumed by most Western commentators. Only after Ukraine was it replaced by a more combative approach, a geopolitical watershed.

So what next? President Trump and his defenders at the editorial page of the WSJ have had almost nothing to say about any of this for four years. In Survival, a journal of global politics and strategy, Thomas Graham and Dimitri Trenin last month described a “New Model for U.S.- Russian Relations” that seemed likely to take hold if Joe Biden wins the presidency. Graham is a distinguished fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations; Trenin is director of the Carnegie Moscow Center (I saw their essay only because I continue to follow David Johnson’s indispensable survey of coverage of U.S.-Russia relations Johnson’s Russia List.) They write:

To date, Russian and American experts disturbed by the sorry state of U.S.-Russian relations have sought ways to repair them, embracing old and inadequate models of cooperation or balance. The task, however, is to rethink them. We need to move beyond the current adversarial relationship, which runs too great a risk of accidental collision escalating to nuclear catastrophe, to one that promotes global stability, restrains competition within safe parameters and encourages needed cooperation against transnational threats.

The hard truth is that the aspirations for partnership that the two sides harbored at the end of the Cold War have evaporated irretrievably. The future is going to feature a mixed relationship of competition and cooperation, with the balance heavily tilted towards competition and much of the cooperation aimed at managing it.

The challenge is to prevent the rivalry from devolving into acute confrontation with the associated risk of nuclear cataclysm. In other words, the United States and Russia need to cooperate not to become friends, but to make their competition safer: a compelling and realistic incentive. The methods of managing great-power rivalry in the past 200 years – through balance-of-power mechanisms and, for brief periods, détente – are inadequate for the complexity of today’s world and the reality of substantial asymmetry between the United States and Russia. What might work is what we could call responsible great-power rivalry, grounded in enlightened restraint, leavened with collaboration on a narrow range of issues, and moderated by trilateral and multilateral formats. That is the new model for U.S.-Russian relations.

Meanwhile, in 2020 the Russians are at it again, according to U.S. intelligence officials. State-backed actors are using a variety of measures, including recorded and leaked telephone calls, to denigrate former Vice President Joe Biden and a Washington elite it perceived as anti-Russian. That’s a job for the next secretary of state. Here’s hoping that it will be William Burns.

David Warsh is a veteran columnist and an economic historian. He’s proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

Lisa Prevost: European study finds wind turbines don't affect lobster harvest

European lobster

Via Energy News Network ( https://energynews.us/) and ecoRI News (ecori.org)

In New England, offshore wind developers and the fishing industry continue to grapple with questions over potential impacts on the region’s valuable fisheries.

A recent European study not only offers good news on that front, it also provides a template for how the two industries can work together.

Research conducted over a six-year period concluded that the 35 turbines that form the Westermost Rough offshore wind facility, about 5 miles off England’s Holderness coast, have had no discernible impact on the area’s highly productive lobster fishing grounds.

The overall catch rate for fishermen and the economic return from those lobsters remained steady from the study’s start in 2013, before the facility’s construction, to its conclusion last year, according to the lead researcher, Mike Roach, a fishery scientist for the Holderness Fishing Industry Group, which represents commercial fishermen in the port town of Bridlington, England.

“It was quite a boring result,” Roach said. “All my lines are flat.”

Ørsted, the Danish energy giant and developer of the offshore wind facility, contracted with Holderness’s research arm to carry out the study, as the group has its own research vessel. The collaborative approach, Roach said, has made the findings all the more credible to local fishermen, who were initially certain that the energy project would destroy the lobster stocks.

“We did the research the same way a fisherman would fish — the same gear types, same bait, deploying in the same way,” Roach said. “We were basically mirroring the commercial fishing method in the area. And that has allowed the fishermen to relate directly to the fieldwork.”

Hywel Roberts, a senior lead strategic specialist for Ørsted and a liaison with the researchers, called the collaboration “a leap of faith on both sides to join together and agree at the outset to live and die by the results.” He noted that the level of research also went well beyond what was required for government permitting.

Ørsted announced the study’s results last month in a press release, even as Roach is still in the process of getting the research approved for publication in a peer-reviewed journal.

It’s no wonder the European-based wind developer was eager to share the news more widely, as the fishing industry has proven to be a powerful force in slowing the progress of offshore wind development off the Northeast coast, such as the Vineyard Wind 1 project.

Last year, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management announced it was pausing the approval process for Vineyard Wind 1, a joint venture between Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners and Avangrid, to be constructed off Martha’s Vineyard. The agency said it wanted to devote more study to the cumulative environmental effects of the many offshore wind projects lining up for approval.

In June, the agency issued a supplemental environmental impact statement that concluded that the cumulative impacts on fisheries could potentially be “major,” depending on various factors. The federal agency is considering requiring transit lanes between turbines to better accommodate fishing trawlers, a design change Vineyard Wind argues is unnecessary and could threaten the project’s viability.

The developer has proposed separating each turbine by a nautical mile. The transit lanes would require additional spacing.

A final report is expected in December.

The outcome of the Holderness study has “very important” implications for wind projects all over, Roberts said.

“The lobster fishery there is one of the most productive in Europe, and we were tasked with building a wind farm right in the middle of it,” Roberts said. “If it can work in this location, we think it can work in most places around the world.”

Ørsted even brought Roach and one of the Holderness fishermen to Massachusetts last year to spread the word to worried lobstermen about the minimal impact of Westermost Rough.

Roach said he’d like to think his findings “eased some concerns” in New England. However, he said he disagrees with Ørsted that the outcome in the North Sea is applicable to other areas of the world, where habitats and the ecology of the species could be very different.

“There are lessons to be learned and guided by, but I can’t say it’s directly transferable,” he said.

Lisa Prevost is a journalist with Energy News Network, an Institute of Nonprofit News (INN) member that has a content-sharing agreement with ecoRI News.

'Our world may be a little narrow'

“Hunter in the Meadows of Old Newburyport, Massachusetts, c. 1873, by Alfred Thompson Bricher. Cattle have been turned into the marsh for pasture, a practice still allowed on some marsh farms of the area.

“The mood is on me to-night only becuase I have listened to several hours of intelligent conversation and I am not a very brilliant person. Sometimes here on Pequod Island and back again on Beacon Street, I have the most curious delusion that our world may be a little narrow. I cannot avoid the impression that something has gone out of it (what, I do not know), and that our little world moves in an orbit of its own, a gain one of those confounded circles, or possibly an ellipse. Do you suppose that it moves without any relation to anything else? That it is broken off from some greater planet like the moon? We talk of life, we talk of art, but do we actually know anything about either? Have any of us really lived? ‘‘

― John P. Marquand (1893-1960), in The Late George Apley (1937), a partly satiric novel about Boston Brahmins. Pequod Island is partly based on a country place in Marquand’s family in Newburyport, on the Merrimack River.

The Somerset Club, a center of old Boston Brahmin society, 42–43 Beacon Street, Boston

William Morgan: When so many deaths were early

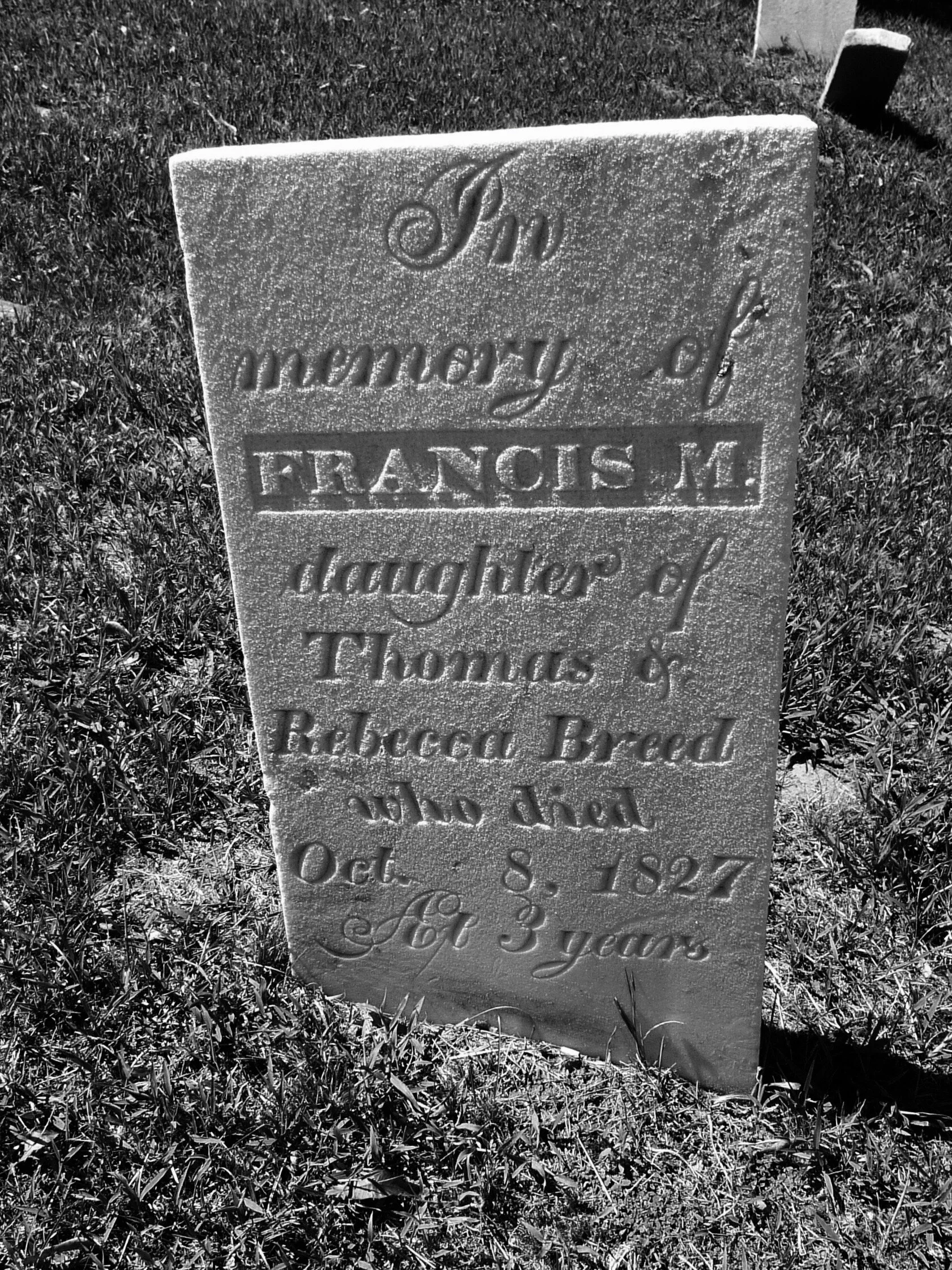

The Stonington Cemetery, in Stonington, Conn. The first burial in it was in 1754, with the interment of Thomas Cheseborough.

Francis Breed was three when she died, in 1827. The stone carver had a penmanship flourish.

Stand in any old New England cemetery and you’re surrounded by premature death. Living along New England's rocky shores in the 18th and 19th centuries meant a constant range of childhood diseases, some spread in pandemics, such as measles, diphtheria and smallpox, if mother and infant survived childbirth, and the other maladies and dangers that often made life brutal and short.

Within a radius of a dozen feet in this handsome necropolis just north of Stonington Borough, there are several reminders of loss in a pre-vaccine world.

Samuel and Alzayda Robinson's son William left this life at 18 months, but with no fancy inscription, just simply: “DIED’’.

Charlotte Augusta Staples, aged one year and seven days, had the same carver as William Robinson nearby, but here with this inscription:

“Happy infant early blest/

Rest in peaceful slumber rest’’

Captain Joseph Eells, born in 1768, got a 19th-Century stone. Perhaps Eells was lost at sea.

Saddest of all, Lydia Palmer was a young wife when she she died (giving birth?) at only 18. Her weeping willow, carved in porous sandstone, is eroding. The inscription here reads:

“Behold & see as you pass by,

As you are now so once was I,

As I am now so you must be,

Prepare for death & follow me.’’

William Morgan is a Providence-based architectural historian and essayist. His latest book, Snowbound: Dwelling in Winter, will be published next month.

City planning

“space created by things” (gouache on paper), by Jessica Poser, in her show “Available Distances,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston for September. The gallery describes the show as “interactions with paint and paper, near and far, the living and the dead.’’

See:

bromfieldgallery.com

Chris Powell: Phony outrage against utilities; legislators: do some work

A Connecticut law requires Eversource to buy electricity from the Millstone nuclear-power plant, above, on the site of an old quarry in Waterford, on Long Island Sound, to keep the facility going.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Last week's hearings of the Connecticut Public Utilities Regulatory Authority and the General Assembly gave many elected officials their chance to denounce the state’s two major electric companies, Eversource Energy and United Illuminating, over rising electric bills and the long and widespread outages caused by Tropical Storm Isaias.

But the hearings didn't vindicate the piling on done by the politicians.

For it turned out that power had been restored well within the time requirements already set by the utility authority. Additionally, news reports tended to support Eversource's contention that most of the recent increase in electric bills has resulted, first, from greatly increased customer use of electricity as people stay home because of the virus epidemic and run much more air-conditioning during hot weather, and, second, from the state law that recently took effect requiring Eversource to buy power from the Millstone nuclear plant, in Waterford, to keep the plant going.

In effect that law hid another tax in electricity bills, and as usual and as anticipated, the people, uninformed, blamed the electric company instead of their state legislators and the governor.

On top of that, the Connecticut Mirror's Mark Pazniokas reported that only 34 percent of charges on Eversource electric bills is attributable to the utility itself. The remaining two-thirds of charges come from the cost of electricity, which Eversource does not produce but buys from generators chosen by its customers; from state and federal government assessments on electricity transmission; and from state government-required subsidies for renewable energy, energy-efficiency programs and the poor.

Eversource representatives at the hearings had the political sense to take their beating calmly and not challenge elected officials over their responsibility for the high cost of electricity in the state. Of course the elected officials did not volunteer to accept their responsibility. They just wanted to strike indignant poses for the television cameras.

But at least Sen. Matt Lesser, D-Middletown, urged the utility authority to declare "force majeure" and nullify Eversource's power-purchase arrangement with Millstone, in effect canceling the new law.

Given the disproportion in responsibility here -- two-thirds for government and non-utility electricity costs and only one third for the utility stuck with collecting the money for others -- the electricity issue may fade quickly since the elected officials have already achieved so much television time for chest thumping.

xxx

END RULE BY DECREE: With the six-month term of his emergency powers to govern by decree expiring on Sept. 9, Gov. Ned Lamont is likely to ask the leaders of the General Assembly to extend them for another few months. While the virus epidemic has sharply subsided in Connecticut, recent flare-ups like the ones in Danbury and at the Storrs campus of the University of Connecticut could lead to a second wave, especially since many people have begun partying as if there is no longer any risk.

But the governor and legislative leaders should let the emergency powers lapse. The epidemic never was severe enough to justify suspending democratic government, and now that the epidemic has largely lifted, it is time for the General Assembly to get back to work, which it abandoned in cowardly panic in March midway through its regular session.

Legislators are far too content to leave potentially controversial policy decisions to the governor as their campaigns for re-election begin. Though the governor has ruled benignly, these decisions have been made without ordinary public discussion and without putting legislators on the record. Important issues having nothing to do with the epidemic have been neglected entirely. Even if legislators face up to their responsibility for Connecticut's high electricity costs, which is unlikely, another few months of gubernatorial rule will delay action until next year.

Ordinary legislative operations can resume safely with mask wearing and Internet proceedings. After all, isn't it ridiculous to classify supermarket employees, trash collectors and mail carriers as essential workers but not the people chosen to make the laws and evaluate government operations? Their salaries are not large but legislators should start earning them again.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

'Depth seizes everything'

Stereoscopic image of visitors to Mount Monadnock in the 19th Century

“It is New Hampshire out here,

It is nearly the dawn.

The song of the whippoorwill stops

And the dimension of depth seizes everything.’’

From “Flower Herding on Mount Monadnock,’’ by Galway Kinnell (1927-2014). He spent his later years in Vermont.

Mr. Kinnell reading a poem at the Grindstone Cafe, in Lyndonville, Vt., on March 16, 2013.

A male Eastern Whippoorwill

Thick nature and history in tiny 'Scratch Flat'

“The place is infused with time; everywhere you look, east or west, north or south, there is history; there are stories, and ghosts, and bear spirits.’’

— From Ceremonial Time, Fifteen Thousand Years on One Square Mile, by John Hanson Mitchell.

In it, he explores a single square mile in a section of Littleton, Mass., nicknamed “Scratch Flat’’ in the 19th Century, looking at history from the last Ice Age and the years of human settlement since then, including Native Americans and their bear shamans, early and later white colonists, witches, farmers (it’s a famous apple country) and later industrial “parks’’ The idea is to perceive past, present and future simultaneously.

Brian Wakamo: Sports walkouts: Imagine what an Amazon strike could do

Via OtherWords.org

First, the Milwaukee Bucks refused to take the court in their playoff game against the Orlando Magic. Then other teams followed suit, leading to a three-day wildcat strike in the National Basketball Association.

The Bucks were protesting the police shooting of Jacob Blake in nearby Kenosha, Wis., but they helped ignite a wave of athletic activism for racial justice. Other leagues followed suit.

Players in the women’s NBA, who often lead athlete protests, joined the strike. Some Major League Baseball teams — including the Milwaukee Brewers — refused to play multiple games as well. So did Major League Soccer players.

And Naomi Osaka, two-time tennis Grand Slam winner, announced she would not play her semi-final match as a protest. She next appeared wearing a face mask with Breonna Taylor’s name on it.

It was a seismic moment in the history of sports.

We’ve seen players use their platform to advocate for social justice, going all the way back to Jackie Robinson, Muhammad Ali and Billie Jean King. And we’ve seen players strike for better collective bargaining agreements.

What’s new are these labor actions for social justice — especially across multiple sports and leagues. It’s unprecedented.

These shows of strength and solidarity had immediate consequences, including at the NBA offices, where around 100 employees struck in solidarity. Within a few days, NBA owners and players announced a raft of initiatives to improve voter access in NBA arenas and to invest in a joint social justice coalition among coaches, players, and owners.

As these athletes have shown, striking does not need to be reserved exclusively for higher wages or a better contract. NBA players have a strong players union and an incredibly well negotiated collective bargaining agreement, but they knew they had the power to amplify a national conversation about police violence. It’s inspiring that they chose to use it.

It’s also an inspiring story about the power of all workers.

Few workers are as well paid as professional athletes, and most have more to lose from running afoul of their employers. But there’s a lesson here for them, too: Workers make the company run, not the CEOs and owners. Withholding that work can force immense changes.

After all, if a handful of athletes refusing to play can yield such immediate results, imagine what would happen if long-suffering, underpaid Amazon or Wal-Mart workers — or both — pulled off a national strike. They could virtually shut down the economy and win the fair treatment they’ve been demanding for years.

That’s what postal workers did in a 1970 postal strike, which completely halted all mail deliveries, even as President Nixon attempted to use the National Guard to deliver the mail. Nixon failed miserably, and postal workers won collective-bargaining rights, higher wages and the four postal unions we have today.

As for those well-paid athletes? I hope they’ll force their employers to take tangible steps in other fights — like for racial justice, a fairer immigration system, and action on climate change.

These athletes just showed us all a path forward. I hope more workers are inspired by their example.

Brian Wakamo is an inequality researcher at the Institute for Policy Studies.

The wet look

Watercolor by Megan Hinton in the program "Plein Air: Watercolor Revisited," at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum Sept. 10-Oct. 1. This is an in-person workshop to be held once a week from Sept. 10–Oct. 1 by Megan Hinton, an artist, art writer, educator and lecturer. The association says that "Plein Air aims to demystify watercolor, a medium often characterized as ‘unforgiving’ and requiring extreme precision to get right.

See:

To the rhythm of the crops

Children gathering potatoes on a large farm in Aroostook County in 1940. Back then, schools in what Mainers simply call “The County’’ did not open until the potatoes were harvested.

— Photo by Jack Delano

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Back when many Americans worked on farms (my maternal grandfather grew up on one) school calendars were adjusted to agricultural needs, especially to harvests. Thus in many school districts, young people didn’t go back to school until weeks later than they do now.

In a few places where agriculture is still paramount, special adjustments are still made. Consider Aroostook County, in northern Maine Trump Country, where (in-person!) schools open early to accommodate a break coming in late September so that the kids and teachers can help bring in the potato harvest.

I think that in general kids are now forced back to school too early, in the best part of summer – late August and early September.

Boston and the rest

Boston from the west

— Photo by Rebecca Kennison

“Reduced to simplest terms, New England consists of two regions: Boston and not Boston.

— Travel writer Wayne Curtis in Frommer’s 2001 New England

“{In} New York, the women walk as though in the rain; in Boston, many women stroll.’’

— Andre Dubus (1936-99), in Broken Vessels: Essays. The Louisiana-born writer ended up living in Haverhill, Mass., where he taught at Bradford College, a small private institution that closed in 2000, after a 197-year run, mostly as a women’s school. It’s now now the site of Northpoint Bible College.

Ignoring Vermont

“Vermont was like a wooer

whose attraction

you shut out, preoccupied

with a lifelong crush….’’

— From “Vermont Aisling,’’ by Greg Delanty, an Irish-American poet who teaches at St. Michael’s College, in Colchester, Vt.

A proposed community arts center for Worcester

The Worcester Art Museum from the Salisbury Street side. The distinguished museum has 38,000 art objects. It was built in 1898, in the heyday of Worcester’s industrial prosperity, which created some big fortunes and art patrons.

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

The University of Massachusetts Memorial Health Center recently announced a $500,000 contribution to Creative Hub Worcester, a proposed community arts center. UMass Memorial stated that the investment in the project is to help improve the mental and emotional health of the Worcester community through creative expression.

The Creative Hub was founded by artists Stacy Lord and Lauren Marotta, who were $850,000 short of their fundraising goal, but have now been able to begin construction thanks to a flurry of recent contributions to the project. The Worcester Creative Hub will transform a former Boys and Girls Club into an event center, art studios, and child-care spaces. The goal of the center is to create a space for artistic expression and community well being.

“This project, this is health to me,” UMass Memorial Health Care President and CEO Dr. Eric Dickson said. “When I see the beautiful place that people are going to be able to come to, the events that will be occurring here in a part of the city that really needs some help, this is what we are committed to doing in addition to providing the great care to the patients we serve.”

The New England Council applauds UMass Memorial Health Center for this investment into the social, emotional and creative wellbeing of the Worcester community. Read more from MassLive and the Worcester Business Journal.

Out from our caves

“Contagion” (mixed media and collage), by Carolyn Newberger, in the group show “Light From Above: Emerging Out of Isolation,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, through Oct. 31.

See:

galateafineart.com