Some are very nice

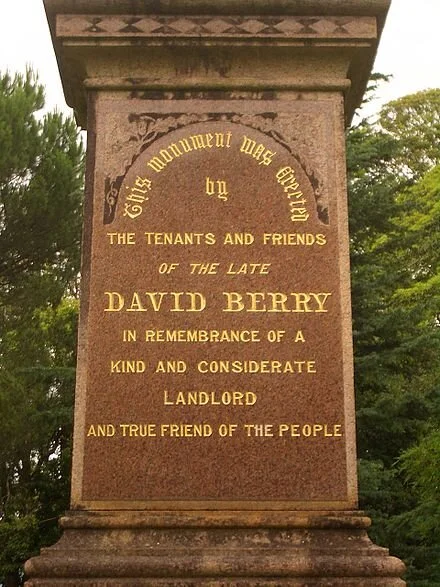

David Berry (1795-1889) was a Scottish-born horse and cattle breeder, landowner and benefactor in colonial Australia.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Being threatened with eviction from your home because you’ve lost job, as has happened to so many people in the COVID crisis, can obviously be traumatic. But the denunciations of landlords as a class can be very unfair, and the eviction suspensions that some politicians promise are dangerously simplistic.

Many landlords are small-business people, for whom the loss of rent can be devastating, enough to drive many of them out of business. When that happens, the effect may be to decrease the available housing and drive up rental prices.

And while the image of landlords, at least to many people, may be negative, most are honest people trying to balance making a profit and being responsive to their tenants.

Being a landlord can be pretty unpleasant. Some tenants are irresponsible or worse, blithely damaging property, delaying their rent payments even if they have the income to pay, having loud parties and otherwise being a pain in the neck.

After my wife and I moved out of our old (built 1835) two-family house in a then rather marginal part of Providence to work abroad, we rented out the place for a few years. In that time, we saw a pretty wide range of tenant behavior, from highly responsible custodians to deeply irresponsible and selfish ones, including somebody who sawed through an antique door to create a cat entrance. We eventually moved back to the house, taking all of it over, but then, after a couple of years, moved a dozen blocks away to a single-family house because there was too much drug-related crime in the neighborhood at the time. (It’s much better now.)

Anyway, in the current public-health and economic anxiety, let’s not demonize whole economic classes, though I might make an exception when it comes to private-equity billionaires….

A better networking app than Zoom?

“The Conversation” (circa 1935), by Arnold Lakhovsky

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

Northeastern University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have developed an app to allow for causal networking. Minglr, a video conferencing app, seeks to replicate the experience of conference attendees bouncing ideas off each other in the real world.

Thomas Malone, founding director of the MIT Center for Collective Intelligence, worked with MIT Sloan doctoral student Jaeyoon Song and Chris Riedl, an associate professor at Northeastern’s D’Amore McKim School of Business, to create the app. Currently, the Minglr is a fairly simple program, with users inputting their primary interests and selecting individuals to talk to. If the selection is mutual, a chat window will be opened. The team hopes that Minglr will allow conference goers to participate in the informal flow of ideas characteristic of conferences and innovation.

“It was so much better than being in just one giant Zoom meeting,” said Malone, who tried out the system at MIT’s Collective Intelligence 2020 virtual conference in June. “I had all the kinds of conversations you’d have in the lobby of a conference.” A survey of attendees who tested Minglr found that 86 percent liked the system and wanted it made available for future conferences, he said.

The New England Council congratulates MIT and Northeastern on their innovative work to tackle one of the many unique challenges created by the COVID-19 pandemic. Read more from the Boston Globe.

Porches and morale

Old farmhouse in Windham, Maine

“Yankees traditionally build porches that will sag after a decade, and tack them on houses built to stand a century. I think it is a custom smiled upon by church fathers, because it ensures that the porch will be a barometer of the morale of whatever occupants may be therein….New England is a harsh climate not only for crops but for neighbors and porches as well. Any flagging of morale – any passing of days skulking indoors in a state of depression …any slacking of righteousness – and down goes the porch.’’

-- Mark Kramer, in Three Farms (1980)

We know who pulled off the Gardner heist

Joe Gibbons

The famous courtyard of the Isabella Steward Gardner Museum

In 2015, my partner, Pam Wall, and I became convinced about who had robbed Boston's Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in 1990, in what remains the greatest art theft in history. Thirteen works of art were stolen, including paintings by Vermeer, Rembrandt, Degas and Manet.

I'd used the Gardner theft as the backdrop for my 2013 novel, Irreplaceable, in which I made the thieves art students. Given the facts of the theft (81 minutes in the museum, thieves not armed, every painting removed from its frame, jimmying a candy machine) art students seemed far more plausible than the mobsters whom law-enforcement claimed were responsible.

After difficult experiences with law enforcement and the museum itself, we've realized that the only way to close out the theft and see the art recovered is to go public with our story.

Please see/listen to the videos linked below, on which Pam and I were guests. And read the article in the Providence Daily Dose.

In any event, far more people know about the museum and the art that was stolen than ever would have had the theft not occurred.

The shows:

Episode One (7/28/2020)

Episode Two (8/11/2020)

Spalding Gray interview with Joe Gibbons in 1985. Hit this link to see/hear it:

New life to found objects

“Abstract Boy” ( painted wood and found material); “Musician II” (painted wood and found material); “Troubled Mind” (painted wood and found material), in Shawn Farley’s show “Chance Encounters: Mixed Media Constructions,’’ at the Michele and Donald D’Amour Museum of Fine Arts, Springfield, Mass., through March 7.

The museum says Farley “endeavors to give new life to found objects such as old foundry molds. Each work seem to have its own personality in its construction, as the obsolete objects that make them up meld together to create a new identity.’’

National Grid's incentives for installing electric-vehicle charging stations

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

National Grid has launched the Take Charge program, which provides incentives for businesses, families, and properties to build electric-vehicle-charging stations. The stations will provide easy access to power for electric vehicles and allow customers to embrace eco-friendly transportation.

The Take Charge program will completely fund all of the electrical infrastructure for approved charging- station installations. National Gird will also help customers select whatever station equipment is right for their home and business, and will provide rebates for the charging-station equipment costs.

The New England Council applauds National Grid for helping New Englanders move away from fossil fuels and increasing access to sustainable transportation. Read more from the National Grid brochure and fact sheet.

Winding and funky

Acorn Street in Beacon Hill, Boston

“It’s {Boston} such a great city, visually. You can’t get that kind of look in Canada that you can get in Boston: the old brick historical buildings, the winding streets, the old but funky neighborhoods like Southie and Somerville {actually a separate city}. You can’t get that elsewhere. It’s a very unique place in that way.’’

-- Brad Anderson, film director

In Somerville, which has rapidly gentrified the past two decades.

'Police beat my mother'

“When I looked out the window, I saw my mother in an angry confrontation with the police. One of the officers lifted his billy club and hit her in the face with it. He busted her eye and she staggered back…I was deeply upset by what I had witnessed. I mean, I was only ten and I had just seen the police beat my mother in the face.’’

Robert Barisford Brown, aka Bobby Brown (born Feb. 5, 1969), singer, songwriter, rapper, dancer and actor. He grew up in Boston’s predominately African-American Roxbury neighborhood.

Mosque in Roxbury

Community garden in Roxbury

— Photo by Wilber Reyes01

Dangling but delightful

“Grotesque: A Different Kind of Beauty” (detail, felt installation, by Carolann Tebbetts, in the group show “8 Visions’’, at the Attleboro (Mass.) Arts Museum, through Aug. 28.

See:

https://attleboroartsmuseum.org/

'Echo from the past'

“A word, a tune, a known familiar scent

An echo from the past when, innocent

We looked upon the present with delight

And doubted not the future would be kinder

And never knew the loneliness of night.’’

— From “Nothing Is Lost,’’ by Noel Coward (1899-1973)

The urgent need for in-person instruction at N.E. colleges

St. Michael’s College, in mostly bucolic Colchester, Vt.

BOSTON

This essay is from The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org). It was written by NEBHE President and CEO Michael K. Thomas in conjunction with leaders and representatives of public and private institutions in all six New England states, including: Mark E. Ojakian, president of the Connecticut State Colleges and Universities; Jennifer Widness, president of the Connecticut Conference of Independent Colleges; Dannel P. Malloy, chancellor of the University of Maine System; Daniel Walker of the Maine Independent Colleges Association; Richard Doherty, president of the Association of Independent Colleges and Universities in Massachusetts; Debby Scire, president of the New Hampshire College and University Council; Daniel P. Egan, president of the Association of Independent Colleges and Universities of Rhode Island; Suresh Garimella, president of the University of Vermont, and Susan Stitely, president of the Association of Vermont Independent Colleges. This essay first appeared in The Boston Globe.

New England colleges and universities are admired for their ability to marshal smart minds to tackle complex problems. This capacity has been evident throughout the pandemic, as their research, teaching and commitment to public service have demonstrated what they do best—chart new paths in the face of uncertainty.

Analysis by the New England Board of Higher Education, an organization supporting students and institutions in the region, indicates that 65 of New England’s colleges and universities plan to provide on-campus and in-person instruction this fall. Ninety-eight will provide a hybrid of in-person and virtual learning, while 35 will support students all virtually. Each institution’s decision was made in response to the risk factors it faces as leaders do their best to respond to the unprecedented health emergency.

We recognize the importance of colleges and universities, both public and private, in the region that will reopen campuses in the coming weeks. These institutions have thoughtfully crafted plans for reopening that, while subject to some risks, will allow them to provide significant benefits to students, institutions, communities and economies. Are there COVID-related risks to reopening? Yes. While such risks cannot be completely eliminated, they can be intelligently managed in a science-supported way.

Leaders of New England colleges and universities have done their COVID homework. They are well prepared to advance their missions of educating students and conducting research and to lead in demonstrating how institutions can begin to carefully move forward in a new environment.

Since March, higher education leaders in all six states have put the full weight of their institutions behind planning, preparation and investment in reopening. This includes plans for robust virus testing, securing adequate personal protective equipment, obligatory mask-wearing, regular health monitoring, contact tracing, quarantine and isolation capacity, regular disinfection, changes to dorms and other campus facilities, limits on group gatherings, training for faculty, students and staff, signed conduct codes, accommodations for those at risk, contingencies for closing campuses or increasing virtual learning—and much more.

These plans have been developed in close collaboration with state government and public health leaders based on science, expert-vetted guidelines and best practices. Many institutions remained open since the start of the pandemic to house and feed students unable to return home or without a safe place to call home. This experience, as well as lessons learned from phased summer re-openings that provided safe access to labs, equipment and clinical experiences will guide the further repopulating of campuses in the coming weeks.

We also support New England institutions that have chosen to offer fully virtual programs this fall. And we support parents and students opting to not return to campus. No single answer is right for all and no option is risk-free. Pursuing a variety of institutional responses in New England can pay important dividends for the region and nation—providing valuable lessons to other institutions and as we reopen other parts of the economy.

The decision to reopen with only remote learning may mitigate some risks, but not all, including possible adverse impacts on individuals, local communities and economies that higher education seeks to serve. We cannot afford a “lost generation” of learners, particularly underrepresented, low-income and minority students—some of whom may not enroll or are at risk of dropping out if on-campus opportunities are reduced. For some such students, the campus provides the only food and housing security they know and staying home may both limit opportunity and increase risk of exposure to the virus.

Delaying or discouraging students’ educations could lead to clogs in the talent pipelines that drive growth for the region’s employers and our innovation-dependent economies. Finally, local communities, already beset by the pandemic’s disruption, will be further deprived of the economic benefits of open institutions and their students. Each of these will have long-term economic and social effects.

We look forward to the time when life on and off campus returns to normal. To do all that is possible to move closer to that goal, we must support colleges and universities in doing what they do best: tackling complex problems with brainpower, innovation and the application of science-based solutions to real-world challenges. Our colleges and universities are engines of innovation because of their ability to explore boundaries. New England institutions are prepared to lead in this time of significant challenge.

Sarah Anderson: The fox is still in the Postal Service henhouse

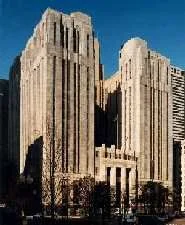

The John W. McCormack Post Office and Courthouse, an historic building at 5 Post Office Square, in downtown Boston. The 22-story skyscraper was built in 1931-1933 with an Art Deco and Moderne structure. The building was renamed for the late Mr. McCormack, a long-time Massachusetts congressman who was U.S. House speaker in 1962-71. Its original name was the United States Post Office, Courthouse, and Federal Building.

Via OtherWords.org

Skyleigh Heinen, a U.S. Army veteran who suffers from rheumatoid arthritis and anxiety, relies on the U.S. Postal Service for timely delivery of her meds to be able to function. She was one of thousands of Americans from all walks of life who spoke out recently to demand an end to a forced slowdown in mail delivery.

The level of public outcry in defense of the public Postal Service is historic — and it’s having an impact.

Shortly after Postmaster General Louis DeJoy took the helm in June, it became clear that the fox had entered the henhouse. President Trump had gained a powerful ally in his efforts to decimate the public Postal Service.

Instead of supporting his frontline workforce, DeJoy has made it harder for them to do their job.

For example, he banned overtime, ordering employees to leave mail and packages behind if they could not deliver it during their regular schedule. Until this point, postal workers had been putting in extra hours to fill in for sick colleagues and handle a dramatic increase in package shipments.

As the mail delays worsened, more than 600 high-volume mail sorting machines disappeared from postal facilities. Blue collection boxes vanished from neighborhoods across the country. Postal managers faced a hiring freeze.

President Trump threw gas on the fire by gloating that without the emergency relief he opposes, USPS couldn’t handle the crisis-level demand for mail-in voting.

Outraged protestors converged outside DeJoy’s ornate Washington, D.C., condo building and North Carolina mansion, and they flooded congressional phone lines and social media. Political candidates held pop-up press conferences outside post offices.

At least 21 states filed lawsuits to block DeJoy’s actions, while Taylor Swift charged that Trump has “chosen to blatantly cheat and put millions of Americans’ lives at risk in an effort to hold on to power.”

After all this, DeJoy announced he’s suspending his “initiatives” until after the election.

This is a victory. But it’s not enough.

DeJoy’s temporary move does not address concerns about the threats to the essential, affordable delivery services that USPS provides to every U.S. home and business, or the decent postal jobs that support families in every U.S. community. These needs will continue long past November 3.

Second, DeJoy has made no commitment to undo the damage he’s already done. And he promised only to restore overtime “as needed.” Will he replace all the missing mail-sorting machines and blue boxes? Will he expand staff capacity to handle the backlog he’s created and restore delivery standards?

Third, DeJoy makes no mention of the need for pandemic-related financial relief. USPS has not received one dime of the type of emergency cash assistance that Congress has awarded the airlines, Amtrak, and thousands of other private corporations.

While the pandemic has been a temporary boon to USPS package business, the recession has caused a serious drop in first-class mail, their most profitable product. Postal economic forecasters predict that COVID-related losses could amount to $50 billion over the next decade.

DeJoy has proved he cannot be trusted to do the right thing on his own. Congress must step in and approve at least $25 billion in postal relief — and legally block actions that undercut the ability of the Postal Service to serve all Americans, both today and beyond the election.

For the American people, this is not a partisan fight. We will all be stronger if we can continue to rely on our public Postal Service for essential services, family-supporting jobs, and a fair and safe election.

Sarah Anderson directs the Global Economy Project at the Institute for Policy Studies. More research on the Postal Service can be found on IPS site Inequality.org.

They stay anyway

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

“Many are saying that remote working is making people reprioritize where they choose to live and work. It’s too early to say if we’re seeing a trend of people flocking to Rhode Island because it’s less expensive, more rural, has great amenities or a combination of all three, but it’s definitely something we’re studying. Rhode Island has always been a well-kept secret in terms of value, now perhaps, it’s not as much of a secret anymore.’’

-- Shannon Buss, president of the Rhode Island Association of Realtors, in GoLocalProv.com on people moving to Rhode Island since the pandemic began.

Hit this link:

I have always thought that the assertions that Rhode Island state and local government retirees flee in large numbers to lower-tax states were grossly exaggerated. People decide to move to, or stay in, places for many reasons, such as job options and weather, but most importantly because of their family and friends connections, and those are tight in the old and compact Ocean State. Now, The Boston Globe reports, Watchdog RI, a nonprofit founded by former Moderate and Republican Party candidate gubernatorial candidate Ken Block, who has often complained about public pensions and other things about this liberal state, has found that of 31,762 retired state and municipal retirees studied by the group, 80.3 percent retired in Rhode Island.

Mr. Block, a wizard at numbers, told the paper that he had expected twice as many of these public-sector retirees to be living out of state. “Certainly, the myth is that a lot of government employees retire and get out of Dodge,” he said. “That is clearly not the case.”

Even so, he told The Globe, $222 million in pension payments is being shipped out of state to these retirees each year, and he said, “That’s money that would be really nice to keep in state, if we could.” (It would be useful to get the numbers on what percentage of public-sector retirees leave other New England states.)

The list of the states where the largest numbers of the aforementioned Rhode Island retirees move to, as reported by Watchdog RI, are:

· Florida: 3,017

· Massachusetts: 1,195

· Connecticut: 237

· New Hampshire: 226

· South Carolina: 198

· North Carolina: 167

· Maine: 136

· Arizona: 118

· Texas: 88

· Georgia, Virginia (tied): 84

Interestingly, two of those states are, by national standards, high-tax when you combine state and local taxes – Connecticut and Maine; Massachusetts is in the middle, with New Hampshire a tad under the median. Generally, higher state and local taxes mean more, if not always better, public services, especially for that high-voting cohort called old people. State-by-state tax-burden comparisons are difficult because state and local tax systems vary widely, especially when you consider business taxes and what sort of purchases are covered by sales taxes.

You’d expect Florida, with its warm winter weather and generally low taxes, to lead in grabbing emigres from other states. (I wonder if that will continue after the COVID crisis there.)

Hit this link to read The Globe story:

Hit this link for some national tax comparisons:

https://wallethub.com/edu/best-worst-states-to-be-a-taxpayer/2416/

Hit this link for the Watchdog RI site:

Besides their human connections, many retirees stay in Rhode Island because much of it is beautiful and there are lots of services within short distances. Not much driving required.

They only look dangerous

“Long Lines” (ceramic and twine), by Annette Bellamy, in the show “Volume 50: Chronicling Fiber Art for Three Decades,’’ at browngrotta arts, Wilton, Conn. The show, starting Sept. 12, will highlight works by 50 leading artists in fiber art.

See:

browngrotta.com

and:

annettebellamy.com

At Weir Farm National Historic Site, in Ridgefield and Wilton, Conn. It commemorates the life and work of American impressionist painter J. Alden Weir and other artists who stayed at the site, including Childe Hassam, Albert Pinkham Ryder, John Singer Sargent and John Twachtman.

Llewellyn King: Save disgusting social media from censorship

— Photo by Johnscotaus

WEST WARWICK

I don’t know a lot about social media. I don’t know how it works technically. I don’t know why it is such a force in society. I don’t know why very prominent people, such as comedian Steve Martin, prognosticator Nate Silver and New York Times columnist Tom Friedman, who have plenty of outlets, tweet.

I don’t know why people who are great company, need to post on Facebook tedious photos of a. their cats, b. their grandchildren, c. their hobbies, and d. their vacations (“That’s Ann and myself in a Costa Rican rainforest.’’).

Because of this personal bric-a-brac, I tend to avoid Facebook and solicitations to befriend people there. I fear those children, that cat, those hobbies, and snaps of my friends despoiling places of natural beauty.

What I do know is that we face a clear-and-present danger of social media censorship.

What makes it worse is those calling for censorship should know better. They are, many of them, of the progressive left. It seems they hate “hate speech” more than they hate anything else, including censorship by machine or, worse, censorship deep in Twitter or Facebook by committees of the nameless wonks.

Now social media is full of remarkably ugly, vicious, deranged and fabricated things. The truth isn’t safe with social media. The truth is scarcely an ingredient. But that isn’t reason enough to introduce censorship, whether self-censorship or some other adjudication of what we see and hear.

Google, Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat, et alia, aren’t publishers. They are common carriers, like the post office, the railroads and the telephone companies. Certainly, they aren’t publishers or broadcasters in the traditional sense.

The remedy for the excess on social media – conspiracies, homophobia, Islamophobia, and even my phobia about cat photos – won’t be cured by getting the companies that carry them to introduce censorship, however well-intentioned and noble in purpose.

The right to free speech is ineradicable, absolute and cardinal. Without it we start sliding down the slippery slope – except the internet slope is steeper, greasier, and globe-circling.

So, I defend President \Trump, Rep. Ilhan Omar (D.-Minn.), Sean Hannity and Rachel Maddow as having a right not to be censored. That is all I’m defending: only their right not to be censored, not their speech or even the ideas behind it.

There was a time, before former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher cracked down on unions, when the printers of British national newspapers set themselves up as de facto censors. Not the editors or owners, but the press operators: They wouldn’t print stories that they disapproved of. The newspapers were forever making statements like this, “One third of last night’s print run was lost due to industrial action.” That meant a shop steward didn’t like the content.

The issue now revolves around hate speech, a social construct. It is, as U.S. Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart said about pornography, “I know it when I see it.” That means that there can be no standard when the offense is so subjective that it is in the eye of the beholder.

The blanket indictment of hate speech, if applied to any discourse – for example, political, literary or sports -- is that it can’t be conducted without the honorable traditions of wit, invective, ridicule, scorn, and satire. If a sports columnist berates a fumbling NFL quarterback, is that hate speech?

Until now the laws of libel and slander have worked imperfectly, but they have done their bit to protect reputations, to halt dishonest and malicious allegations, and to give a kind of discipline, sometimes lax, to journalism.

These laws aren’t adequate for the Internet, but they hint at future concepts that might endeavor to quiet the internet and its social media sewers. Censorship won’t do it with perpetrating a greater evil.

When you’ve read this, you may want to hurl used cat litter at me in the street. Your right to want to do that should be unassailable, but if you do it, you should be prosecuted for assault.

Hate is a human emotion, and emotions aren’t criminal until they’re acted on.

If you censor the Internet, as many would like, the workaround will come in seconds. Social media and its sewer of disgusting, repugnant and vile assertions won’t be silenced, but honest disputation may be banned.

Actually, I love cats

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Website: whchronicle.com

Philip K. Howard: Let COVID crisis cut the bureaucracy that strangles education

How to bring them back?

The COVID-19 crisis could be the impetus that finally pushes the broken machinery of America’s schools over the cliff. Everyone is scrambling to figure out how to educate in a pandemic, and the answers will differ depending on the infection rates in particular communities and many other variables. Work rules, legal entitlements and one-size-fits-all bureaucracy are impossible to comply with.

Who decides? This is where the centralized education apparatus collapses of its own weight. Teachers unions want to control when and on what terms teachers return to work. Education regulators in Washington, D.C., and state capitals want to dictate answers with a new set of rules. They expect the COVID-19 education framework to come out of negotiations with unions, who have already threatened to strike if teachers must go back to the classroom.

The stranglehold by central bureaucrats and union officials over how schools work is why they fail so badly. Public schools are a giant assembly line of rigid work rules, legal entitlements, course plans, metrics, granular documentation, and legal proceedings for almost any disagreement, including classroom discipline and comments in a personnel file. Day after day, teachers and principals grind through the dictates of this legal assembly line. There’s little room for innovation or creativity, and not even the authority to maintain order. The only certainty is no accountability. No matter how much or how little someone tries, no matter how badly a school performs, there will be no effective accountability.

While teacher pay has stagnated over the past two decades, the percentage of school budgets going to administrators has skyrocketed. Half the states now have more noninstructional personnel than teachers. The Charleston County, S.C., school system had 30 administrators each earning over $100,000 in 2013. Last year it had 133 administrators earning more than $100,000. Union officials and central bureaucrats owe their careers to the bureaucratic labyrinth they create and oversee.

Now the unions want to devise a pandemic school assembly line. In addition to not returning to the classroom, ideas floated so far include a limit of three hours of online instruction, a preference for older teachers to teach online courses instead of teachers with demonstrated skills, and a refusal to allow classes to be recorded and accessed anytime because of privacy concerns.

Top-down dictates don’t work well in any setting, and particularly not in the pandemic. Some teachers want schools to reopen in their communities, but others will not want to take the risks of infection. Distance learning is an experiment just beginning; some teachers will be effective at distance learning, and others not. It may be better to record remote lessons by superstar teachers, and to supplement this with online tutoring. A hybrid model of distance learning with staggered attendance is also a possibility. Tailoring these techniques to particular populations and students holds the promise of effective education. But these experiments will surely fail if rigidly constrained by rules in advance.

A further complication is that parents need to get back to work. But they will also have different tolerances for exposure to risk. They will need not one mandated solution, but different alternatives. How about small learning pods, organized by neighborhoods, and overseen by teachers? This will require teachers to supervise and teach students of different ages. Different communities will require different approaches, taking into account the needs of the students and parents, the local infection rates, and other factors.

The urgency here could lead to innovations that are unimaginable to stakeholders stuck in current bureaucratic machinery. This disruption is also an opportunity to finally abandon the system and replace it with a set of core principles that restore ownership to educators and parents on the ground. These seem to me the core principles:

· Replace bureaucracy with periodic evaluations. Replace most mandates and reports with general goals and principles. Replace red tape with periodic evaluations by independent observers who judge a school by a number of criteria, including academic achievement and school culture.

· A new deal for teachers. Give teachers much more autonomy to run classrooms in their own ways. Remove most paperwork burdens, especially in special education. Use the funds now spent on excess administrators to pay teachers more, and to provide alternative education settings for disruptive students.

· Restore management authority. Restore the authority of principals (or other designated school leaders) to run a school, including allocating budgets. Because accountability is vital to an energetic school culture, principals or governing committees must be able to terminate teachers who are less effective. Instead of legal proceedings, safeguard against unfair personnel decisions by giving veto power to a site-based parent-teacher committee.

· Revive local autonomy. All stakeholders must have a sense of ownership of their schools. Within broad boundaries, communities should be free to set priorities and manage schools as they believe effective.

For several decades, public-school reforms have focused on measuring and rewarding specific output measures, notably test scores, or improving inputs, such as training programs and new technology. But the best measure of a school is its culture—with shared values, goals, energy and mutual commitment. That’s what good schools all share. It is impossible to have a good culture unless the teachers, administrators and many parents all feel a sense of ownership. That’s why top-down reform ideas have little impact, and why the accumulated red tape is counterproductive. Educators need to focus on their mission, not filling out bureaucratic boxes.

America ranks poorly in international student-achievement results despite spending more per-capita than all but a handful of countries. Teacher attrition is at 8 percent a year, with the best teachers burning out or quitting because of frustration with suffocating bureaucracy. Principals too are leaving, with one out of three saying that they plan to pursue different careers within five years.

No one likes the system. Over the years, I have worked with leaders of school systems across America, such as in New York City and Denver, with teachers unions, and with research firms such as Public Agenda. Everyone feels disempowered from doing what they think makes sense. But the key stakeholders are stuck in a kind of trench warfare, firing bureaucratic rules at each other. Union operatives and public administrators control compliance with, literally, thousands of pages of detailed requirements. Schools are stuck in the muddy no-man’s-land of legal mandates and people demanding their legal entitlements.

The only cure to what ails America’s schools is to abandon the massive bureaucratic machinery aimed at forcing everyone to make it work. The accumulated education bureaucracy crushes the human spirit and any chance of fostering energetic school cultures. The COVID crisis could be the impetus for a mutual disarmament. School bureaucracy should not be reformed but abandoned. It fails every constituency that matters—students, teachers, principals, parents, and the broader society—and it prevents the adaptability needed to cope with COVID-19.

Philip K. Howard is a lawyer, legal-system and regulatory reformer, New York City civic and cultural leader, author and photographer. He’s chairman and founder of Common Good (commongood.org). His latest book is Try Common Sense. Follow him on Twitter: @PhilipKHoward. This piece was first published by Education Next.

Rearranging Boston

Bluebikes in Boston. Originally Hubway, Bluebikes is a bicycle sharing system in the Boston metropolitan area. The system is owned by the municipalities of Boston, Cambridge, Everett, Somerville and Brookline, and is operated by Motivate.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Boston is starting to implement new street-narrowing, traffic-calming, bike-lane creation and sidewalk-widening plans that will make parts of the city’s very dense urban core more pleasant.

Mass.streets.blog.org summarized the program in May, when it reported:

“The initial plans include a network of new protected bike lanes across downtown Boston and around the Public Garden, expanded bus stop waiting areas, and processes to let restaurants expand their outdoor seating areas on sidewalks and on-street parking lanes.’’

The new bike lanes are already being set up, albeit not yet permanently; cones are being used, not concrete or metal barriers.

Some of these plans were in the works before COVID-19, but the pandemic has jump- started some of them to encourage social distancing and boost walking and bike riding by COVID-cautious people worried about taking public transportation (though those concerns have been found to be exaggerated).

Sidewalks in most American cities are too narrow. Widening them for restaurants, outdoor retail stores and other functions will add to cities’ liveability.

Anything that discourages car traffic and encourages walking and bike riding and, yes, a return to public transportation in center cities, will improve their quality of life and help lure back residents, businesses and tourists who fled because of the virus.

It should be said, by the way, that density per se does not present a COVID-19 peril. Consider how well Hong Kong, Singapore and Taipei have kept virus cases down to a handful. That’s probably in part because of lessons from the East Asian-based SARS epidemic, in 2002-04

And note that virus cases are much lower in densely populated and affluent downtown Boston than in neighborhoods a little further out with more poor people. To reduce your chances of getting sick with COVID, live in a rich, orderly neighborhood where people follow mask and social-distancing guidelines and lose weight while you’re at it. But back to reality….

Of course it’s easier for rich folks to leave town in pandemics and to avoid crowded places.

To read more, please hit this link.

'Selling out'

“Our neighbors have concentrated on trading up, selling out

to the enticements of Real Estate

and their intensifying need for

quick-acting contraptions….’’

— From “Farmer and Wife,’’ by Peter Davison (1928-2004), a Boston-based poet, editor, memoirist and literary historian, especially of New England poets

Chris Powell: Better journalism needs a better public

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Hartford's City Council is worried about the future of the city's newspaper, The Hartford Courant, whose management and ownership have been in turmoil on top of the stresses imperiling the newspaper industry generally.

Like most regional and local papers, The Courant today has much less staff, content and reach than it had a decade ago, and there are fears that its owner, Tribune Publishing, which is offering all its properties for sale, will relinquish the paper to the chain's largest shareholder, hedge fund Alden Global Capital, which shows little interest in journalism and civic life.

So the City Council is preparing a resolution urging Tribune and Alden to stop diminishing The Courant. "This is our paper," City Council member Marilyn E. Rossetti says, and its decline is "a travesty."

But then Hartford is Connecticut's capital city and has been declining for decades longer than The Courant has. Indeed, as a business matter The Courant long has done better by Hartford than the city has deserved.

It's simply a matter of demographics. Hartford's population is about 122,000, a third smaller than in the 1950s. Thirty percent of its residents are impoverished and almost 22 percent foreign-born and thus less likely to be fluent in English and attuned to civic affairs.

While West Hartford next door has only about half Hartford's population, only 7½ percent of the suburb's residents are poor and only 17 percent are foreign-born. As a result The Courant long has had far more subscribers in West Hartford than in Hartford, subscribers in West Hartford are far more valuable to advertisers than subscribers in Hartford, and downtown West Hartford has supplanted downtown Hartford in important respects.

Being so poor, having a political class dominated by government employees and others drawing their livelihood from government, and lacking a strong middle class independent of government, Hartford is far more vulnerable to political corruption and so needs journalism more. But journalism isn't free, and with its awful demographics the city can't afford it. Serious journalism can't make money in the city.

Even if Hartford got all the journalism it needed, would it make much difference when so many city residents are stressed by poverty, can't read English, can't afford to subscribe, and lack the education necessary to understand and care about public life?

To acknowledge Hartford's awful demographics and their impact on business conditions is not to disparage its residents. For like Connecticut's other troubled cities, Hartford is only what all of Connecticut makes it, and impoverished and dysfunctional cities are actually part of the state's longstanding policy and social contract.

Connecticut's poverty and education policies fail chronically but their primary objective long ago ceased to be to elevate and educate the poor but rather to sustain the government class ministering to them. This supports the state's political regime, and those not directly dependent on the regime tolerate this policy failure as long as they can escape its pernicious consequences -- crime, bad schools, and political correctness -- by moving to the suburbs.

Amid the failure of poverty and education policy, the best that Connecticut's intelligentsia can propose is just to spread the dysfunctionality around, to prevent any escape from it as it grows.

In this sense the suburbs may need journalism more than Hartford and the other troubled cities do, since the suburbs are home to the people with the capacity to understand policy failure and to support change -- middle-class people employed outside government, people who pay more in taxes than they get from government in income.

Why do these people accept the failure of government to reverse the decline of the cities? Maybe it's because their journalism is just as content with the awful social contract as the government class is. Or maybe they are just as demoralized by policy failure as city residents have been.

In any case, there may be a chicken-and-egg situation here. There won't be a better press without a better public, a public willing and able to pay for it, nor a better public without a better press. But how can Connecticut achieve either when most students now graduate from its high schools without ever mastering high school work and are not prepared to be citizens, much less newspaper readers?

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Leave wildlife alone

Piping Plover chick

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

An endangered Piping Plover chick was illegally removed from a Westerly, R.I., beach last week by vacationers who brought it home with them to Massachusetts, according to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

The chick was eventually brought to a Massachusetts wildlife rehabilitator when it began to show signs of poor health. Given its rapidly declining condition, it was transferred to Tufts Wildlife Clinic and then to Cape Wildlife in Barnstable. Despite the best efforts of veterinarians, the chick had become too weak from the ordeal and died.

The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service asks that people don’t disturb or interfere with plovers or other wildlife. While wild animals may appear to be “orphaned,” they usually aren’t; parents are often waiting nearby for humans to leave. Plover chicks are able to run and feed themselves, and even if they appear to be alone, their parents are usually in the vicinity.

“With such a small population, each individual bird makes a difference,” said Maureen Durkin, the agency’s plover coordinator for Rhode Island. “By sharing our beaches and leaving the birds undisturbed, we give plovers the best chance to successfully raise chicks each year.”

About 85 pairs of Piping Plovers breed in the Ocean State under the close watch of several agencies, including the Fish & Wildlife Service and the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management.

The Piping Plover is a protected species, although its population on the East Coast is slowly making a comeback. The number of Piping Plover breeding pairs has increased from 1,879 in 2018 to 2,008 pairs last summer.

Baby songbirds, seal pups and fawns are also at risk from being removed from the wild unnecessarily by people mistaking them for orphans. If a young animal is encountered alone in the wild, the best course of action is typically to leave the area. In most cases the parents will return without human intervention, according to Fish & Wildlife Service officials.

In rare instances where a young animal is truly in need of assistance, people should contact the appropriate state or federal wildlife agency, whose staff is trained to handle these types of situations. Members of the public should never handle wildlife or remove it from the area before contacting authorities. In addition to the likelihood of causing more harm than good, regardless of intentions, it’s illegal to possess or handle most wildlife, especially threatened and endangered species such as Piping Plovers.