'Youth Voices for the Ocean'

Artworks from “Youth Voices for the Ocean,’’ at The New Bedford Whaling Museum, through Aug. 19.

This is the first part of the museum’s new “Inside Out!” outdoor exhibition series, which promotes the works inside the museum, which is now open.

Each exhibition will last two weeks and feature photographs showing a sampling of the museum's collection.

“Youth Voices for the Ocean’’ is a guest exhibit by Bow Seat Ocean Awareness Programs. Its artwork comes from more than 13,000 students across 106 countries participating in Bow Seat's annual Ocean Awareness Contest. The students were asked to show how humans are damaging the oceans, and how we can start to solve the problems we’ve caused.

Daniel Regan: Reading for the sake of reading

At Northern Vermont University — Johnson, where the author served as dean of academic affairs.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

JOHNSON, VT.

Typical lists of core competencies for undergraduates feature written communication, critical thinking and information literacy, among others, but merely presume, leaving unstated, the bedrock importance of reading skills. Lifelong learning, a dedication to which is part of practically all mission or aspirational statements, includes the ongoing practice and continued appreciation of those core skills, including—presumably—reading.

What is rarely discussed, however, is why we continue to read. Yet to that seemingly simple question there can be several answers, which may differ for our varied student bodies: traditional-age students, say, compared to the adult learners that colleges and universities seek increasingly to attract. The answers may also change for individuals as they advance through the life cycle. These changes deserve greater awareness and more explicit attention. Specifically, why bother to read when you’re old?

I have always loved to read. But why? The answers are much different now than they were before. And what I get from my reading has changed, too. I have long considered reading the bottomless well to which I could turn as needed, a singularly empowering resource in my life. If I found myself in a pinch, I figured I could read my way out of it, by learning what I needed to know. Now though, if I am honest with myself, increasing my stock of deployable information and skills is not really why I read, even if one does amass a good bit of knowledge, some of it usable, along the way.

For the most part, however, I don’t read to learn, especially when it comes to reading more extended pieces. The exceptions, while significant, are either mundane (most recently, for instance, how to clean my coffeemaker) or quotidien (regular information and perspectives from newspapers and magazines). For more in-depth reading, staying au courant is clearly not my goal—since so much of what I read is not particularly current.

Nor do I read for purposes of explicit self-improvement, about which I generally care very little at this point in my life. Again, there are exceptions: for instance, of late, Ibram X. Kendi’s works on antiracism. But I’m not reading great novels or major works of non-fiction as a means of working through problems or applying insights gained to my own life. In fact, I am not really using what I read for any particular purpose—surely not to identify a salient reference or mark a potential quotation for a research paper.

It is also not to acquire bits and pieces of knowledge, Jeopardy-style, that I read. There’s scarcely room in my memory registers for that. In truth I can barely, without a jog, conjure up what I’ve read a relatively short time ago. The recent experience of reading Joyce Carol Oates’s and Christopher R. Beha’s (eds.) Anthology of Contemporary American Short Fiction, for instance, with its 48 selections over 760 pages, was brilliant but dizzying. I would stumble, if asked just days later, to pinpoint which stories I found most striking.

But luckily, instant recall doesn’t matter so much, because I’m no longer aiming to impart what I’ve read to others. I taught for a long time, and loved it, but do so no longer, except for some weekly tutoring at an adult basic-education center. Thus I am no longer an interpreter of or mediator between the works of a primary author and an audience of students or colleagues. Now what I read stays mostly inside, in intense but internal dialogue, except for occasional comments to college-age kids or my spouse. And I surely do not read just to pass the time. There are far easier ways of doing that.

So, why read (or re-read) Middlemarch? The Last Tsar? The Awakening? Simply Einstein?

The real reason I read, and derive so much pleasure from reading, is because of its intense present-ness. Reading provides an absorption in the moment that, for me, few other activities can match. This form of radical present-ness, an immersion in a different setting, group of people, sometimes another culture or society, is not a form of escape. I never forget who and where I am or my separation from what transpires on the pages I am reading or scrolling through. But the act of reading nevertheless lifts me, and elevates ordinary existence. .

That is why I, now into my 70s, continue reading. With luck I hope to continue well beyond. It won’t be because the works appear on some bucket list composed of the works on the Harvard Five-Foot Shelf or a list of 100 Best Novels, or even the collected works of a particular author. It is freeing to read without a central utilitarian purpose, however valid it might be. Until recently I don’t think I recognized sufficiently the possibility of—well—just reading.

Here are three suggestions by way of conclusion. First, I would encourage the explicit inclusion of reading as a core learning outcome, rather than merely as the assumed foundation for other competencies such as critical thinking, information literacy and written communication. Second, encourage students to consider the varied purposes for which they might read, and how these might change over time. For colleges and universities to truly commit to the lifelong development of our students, consideration ought to be paid to the changing import and meaning of intellectual activities, including reading. And finally, help students see that the pleasure of radical absorption awaits them—at any age.

Daniel Regan is a sociologist and the retired dean of academic affairs at Johnson State College, now Northern Vermont University-Johnson.

Annie Sherman: R.I. coastal properties at risk as waters rise

Historic house in Newport’s flood-threatened Point neighborhood

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

NEWPORT, R.I.

On her first day of work at the Newport Restoration Foundation, in 2015, Kelsey Mullen arrived late. The house in which she was living had flooded again, and water on the street rimmed her car’s tires.

The Bridge Street home in the city’s historic Point neighborhood is at a confluence of water sources near city storm drains and Newport Harbor, so its stone foundation provides little barrier to storms or high tides. The ground is often saturated and slopes gently toward the house, so water has nowhere to go but inside and all around. The basement perpetually smelled like the sea, Mullen said, while sump pumps and dehumidifiers kept busy.

Built in 1725 by famed furniture maker Christopher Townsend, 74 Bridge St. sits just 4 feet above sea level. Luckily, it hasn’t sustained permanent damage, but the home is a stunning reminder of what could happen to entire neighborhoods if action isn’t taken to protect them from the damaging effects of increased water.

The Environmental Protection Agency reports seas have risen 10 inches since 1880, and they are projected to swell as much as 3 feet during the next 50 years. Coupled with flooding from chronic rain events, coastal houses like this little red Colonial and historic business districts from Narragansett to Westerly and Warwick to Bristol will be underwater.

“This is the canary in the coal mine, where rising water is impacting this house and we will see impacts in other houses,” said Mullen, now the director of education at the Providence Preservation Society. “With this issue, there are no experts, there is no benchmark. If you’re waiting for an official sanctioned recommendation, it’ll be too late, and there will be loss along the way.”

Since seaports and coastal communities were settled first historically, there are billions of dollars of valuable resources in harm’s way statewide.

“Back in 2007, there was the feeling that, ‘Let’s not worry about it,’” said Wakefield-based historic-preservation expert and community planner Richard Youngken. “Now everyone is concerned because it’s getting worse.”

Guidance from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the National Park Service provides approximate courses of action, while urgent pressure to find a solution forces cities and towns, preservationists and engineers, individual organizations, and homeowners to assess risk, then develop and execute a specialized strategy on their own.

This triggers inconsistent approaches, because what works for one house or municipality, might not work for another, said Arnold Robinson, historic preservationist and regional planning director for Fuss & O’Neill engineers in Providence.

“Flooding varies in different hydrologies and geographies, so what happens in Louisiana is different than Vermont, and how they deal with it is different. So that leaves us preservationists to figure it out, and share solutions with each other,” Robinson said. “There is a lack of funding for this adaptation, too. We are not investing in making historic resources more resilient. And if you look at the economy of New England states, history is our economic engine.”

A ‘future archipelago’

Initiatives in Newport and North Kingstown, most notably in its village of Wickford, which are at the Ocean State’s risk epicenters among its 21 coastal municipalities, show progress. These two coastal communities alone boast 842 historic structures of 1,971 statewide, wrote Youngken in his 2015 report Historic Coastal Communities and Flood Hazard: A Preliminary Evaluation of Impacts to Historic Properties.

The number of National Register‐listed or eligible resources in Rhode Island’s coastal and estuarine flood zones, as mapped by FEMA. (Youngken Associates)

With more than $432 million of historic properties within FEMA flood zones, he reported, Newport has the most to lose. A lion’s share of the City by the Sea’s historic district and tourism cash cow could be swallowed by water, including original Colonial buildings on Bowen’s Wharf, Market Square, the historic Brick Market and lower Washington Square, Long Wharf, and The Point, and most of the Fifth Ward and Ocean Drive, according to Youngken.

“Imagine flooding all along Thames Street and everything west of Queen Anne’s Square,” Youngken said. “With sea-level rise, all of that comes into jeopardy, so you lose a big portion of the city. The same is true of Wickford. Rhode Island would become a series of islands — our future archipelago.”

Hoping to stem the deeper existential forces of climate change-induced flooding and sea-level rise, Newport this year issued the state’s first guidance plan for residents to elevate their historic properties. These voluntary guidelines clarify what the city will examine with homeowners’ elevation requests, as well as provide additional advice for materials, siting, options for building accessibility, decreasing hardscapes, and increasing green space and drainage to eliminate excess water in overburdened municipal systems.

“Resiliency to climate change, and specifically the threat posed by rising sea levels, is a fundamental component to the city’s long-term historic-preservation goals, and these guidelines speak to that,” said Newport’s historic-preservation planner Helen Johnson. “For several years, we’ve been exploring how rising sea levels are projected to impact some of our most historically significant and environmentally sensitive neighborhoods. And while we can’t control the tides, we can influence how we respond as a community.”

In some cases, elevation may not be ideal. It’s expensive, costing between $40,000 to $250,000, and myriad limitations could stymie the most steadfast preservationist. Many houses on The Point, for instance, are situated on the front property line, with their front steps on the sidewalk, so building access is essential to consider, Johnson said, as is drainage and so much else.

“Some homeowners can move the house back, others cannot, so you have to get creative,” she said. “It also impacts the historic streetscape. Some preservationists argue that this approach defeats the purpose, as does relocating the house to drier ground.”

City officials, including the Historic District Commission that drafted the guidelines and will review all future elevation applications, said they recognize that for homes in some of Newport’s more vulnerable areas, elevation is the best route to preservation. The Point has set the elevation precedent during the past century, with many houses already raised since the hurricane of 1938, Johnson said.

The new guidelines complement a series of flood gates buried at vulnerable spots in the city, including the Wellington Avenue and The Point neighborhoods. Another is planned for King Park. The gates act as tourniquets to stop salt water from rushing in from the harbor and to allow stormwater to drain from higher areas.

Though flooding still occurs, especially at high and king tides, Johnson noted that they quickly proved to be a viable option to mitigate flooding.

“But these types of infrastructures can only get us so far,” she said. “The other side is elevating buildings and preparing our aboveground infrastructure as well. But depending on a house’s location in the flood zone, it might have to go up really high. So, when is it not feasible to elevate it, and if you move it, where does it go and does it lose its historic significance? We don’t have those answers, and don’t touch on that in these guidelines, because we wanted to focus on what was achievable.”

On ‘verge of disasters’

Nonprofits like the Preservation Society of Newport County (PSNC) and the Newport Restoration Foundation (NRF) are paying attention to those unanswered questions.

PSNC’s 266-year-old Hunter House is perched a few meters from Newport Harbor, its basement floods regularly, and its Bannister’s Wharf store frequently sees water just inches from its front door, according to the organization’s executive director, Trudy Coxe. It hasn’t lost anything yet, she said, but its staff has become adept at relocating both buildings’ contents while they consider contingency solutions, including elevation and amphibious technology.

“Hunter House was even built to endure flooding, so it’s set back slightly and has a small plot of land. But that house is at risk, which is true for a lot of houses along Washington Street,” Coxe said. “I don’t think any state in America is doing enough. One of the things that gets in the way of doing more is that we don’t know what we should be doing. The solutions are incredibly expensive. Plus, people think they can pass it to the next generation, or that someone will come along and wave a magic wand and it will all go away.

“But predictions are pointing to it getting rougher out there. We are on the verge of disasters.”

The NRF is equally concerned. It has preserved and restored more than 80 homes from the 18th and early 19th centuries, 25 of which are in The Point, including 74 Bridge St. Though it hasn’t adapted or elevated its houses to accommodate excessive water, that’s not to say the organization won’t, according to executive director Mark Thompson.

Though the NRF sold 74 Bridge St. in early July, Thompson said he suspects that it’s a candidate for elevation with its new owners’ rejuvenation plan.

“A lot of people think that The Point is the focal point of the climate-change issue in Newport, but we are not just interested in our houses, we are interested in Newport, because if we save 25 houses, and nobody else is able to do that, then there is no point in it,” Thompson said. “Cities around the world say infrastructure should be erected, like gating systems, and elevating or relocating houses to preserve the integrity, but how high do you raise it to be effective? Our goal is to save the houses where they are, and that we save them the right way.”

NRF’s interest in that signature property inspired it to launch a national conference where experts discussed these issues and possible solutions. Its inaugural Keeping History Above Water event in Newport in 2016 became a huge success, said Mullen, who was then NRF’s public-program manager. Since then, it has spread to other coastal communities, including St. Augustine, Fla., Annapolis, Md., and Palo Alto, Calif. The conference is scheduled to be held in Charleston, S.C., next year.

J. Paul Loether, executive director of Rhode Island’s Historical Preservation & Heritage Commission, also is trying to create an intelligence clearinghouse to help municipalities, homeowners, and nonprofits streamline strategies. As experts in knowing what properties are significant across the state, the Providence-based commission wants to secure funding and political influence to amplify preservation and to identify the highest risk areas and better equip municipal planners.

“Newport’s solution will work for them as a city, but we need to be more strategic as a state,” Loether said. “It doesn’t take much to visualize Main Street in Wickford being underwater. So, we want to give them the best information we can. But there is no easy answer. It raises philosophical issues, financial issues; where is the tipping point? I have seen houses in Connecticut raised 12 feet and it looks like Orson Welles’ ‘War of the Worlds.’ But others you can’t even tell.

“It’s not driven by preservation in many cases, it’s driven by the rising cost of FEMA flood insurance. If you’re dealing with a single structure, it’s one thing, but the whole neighborhood? Are you going to raise the street? Then you have to wonder, are we preserving history or preserving the property? Then the bigger issue is, do you really have a historic district?”

From the Ocean State to the Golden State, there are more questions than answers, which is precisely why the approach is scattershot. But as storms become more frequent and intense and nuisance flooding becomes more routine necessity will drive activity. Though no residents in Newport have received elevation approval yet, Johnson, the city’s historic preservation planner, remains optimistic that this is the way forward.

“We want to get these communities together to learn from what we’re doing here in Newport and see if we can help other municipalities develop their own guidelines,” she said. “We are such a small state but we are so diverse in our building stock and municipal resources, so we need to discuss the impacts and things we can do to tackle sea-level rise and floodwater.”

In the meantime, there are tough truths we must face, Mullen said.

“In terms of cultural heritage, there are only a few possible reactions: you either raise up structures; you relocate structures; or you retreat,” she said. “And ultimately, maybe 100 years, retreat is the only predictable outcome. We’re not seeing reversal in climate trends, and climate scientists say the projections are too conservative. So, if we know the conditions are unlikely to change, we have to change the way we live, and make proactive decisions now about what we’re willing to lose and what we’d like to keep.”

Annie Sherman is a freelance journalist based in Newport covering the environment, food, local business, and travel in the Ocean State and the rest of New England. She is the former editor of Newport Life magazine, and author of Legendary Locals of Newport.

A healthy pain

Cannon Mountain ski area, in New Hampshire

—Photo by Fredlyfish4

“My thighs don't hurt, no, it's all in my calves,

different muscles from a normal trail hike,

I've drank too much water, but I make it,

cooler air of altitude braces me,

green New England rolls out before my eyes…’’

From “Hiking Up a Ski Trail in Summer,’’ by David Welch

Faith vs. intellect

Exeter’s Squamscott Falls in 1907

“Never confuse faith, or belief — of any kind — with something even remotely intellectual.’’

From A Prayer for Owen Meany, a novel by John Irving about two boys growing up in the fictional small New Hampshire town of Gravesend in the 1950s and ‘60s. The town is based on Exeter, N.H., where Mr. Irving grew up. He now lives mostly in Canada but has a home in Vermont, too.

David Warsh: What went wrong in Epidemiologists’ War

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It is clear now that United States has let the coronavirus get away to a far greater extent than any other industrial democracy. There are many different stories about what other countries did right. What did the U.S. do wrong?

When the worst of it is finally over, it will be worth looking into the simplest technology of all, the wearing of masks.

What might have been different if, from the very beginning, public health officials had emphasized physical distancing rather than social distancing, and, especially, the wearing of masks indoors, everywhere and always?

Even today, remarkably little research is done into where and how transmission of the COVID-19 virus actually occurs – at least to judge from newspaper reports. Typical was a lengthy and thorough account last week by David Leonhardt, of The New York Times, and several other staffers.

Acknowledging that previous success at containing viruses has led to a measure of overconfidence that a serious global pandemic was unlikely, Leonhardt supposed that an initial surge may have been unavoidable. What came next he divided into four kinds of failures: travel policies that fell short; a “double testing failure”; a “double mask failure”; and, of course, a failure of leadership.

The American test, developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which worked by amplifying the virus’s genetic material, required more than a month longer to be declared effective, compared to a less elaborate version developed in Germany. The U.S. test was relatively expensive, and often slow to process. The virus spread faster than tests were available to screen for it.

As for masks, Leonhardt reported, experts couldn’t agree on their merits for the first few months of the pandemic. Manufactured masks were said to be scarce in March and April. Their benefits were said to be modest.

From the outset it was understood that most transmission depended on talking, coughing, sneezing, singing, and cheering. Evidence gradually accumulated that the virus could be transmitted by droplets that hung in the air in closed spaces – in restaurants, and bars, for example, on cruise ships, or in raucous crowds. By May, it became more common for official to urge the wearing of masks.

But Leonhardt cited no evidence of the rate at which outdoor transmission occurred among pedestrians, runners or participants in non-contact sports. Nor did he take account of wide disparities of distance across America among people in cities, suburbs, and country towns. In many areas, most people used common sense, which turned out to be pretty much the same as medical advice.

Instead of becoming ubiquitous indoors and out, as in Asia, or matters of fashion, as in Europe, Leonhardt wrote, masks in the United States became political symbols, “another partisan divide in a highly polarized country,” unwittingly exhibiting the divide himself.

Whether things would have turned out differently had face-coverings been confidently mandated everywhere indoors from the very beginning, and recommended wherever where crowds were unavoidable, is a matter for further research and debate. Not much is known yet about the efficacy of various forms of “lock-down” – office buildings, public-transit, schools, college dormitories.

This much, however, is already clear: very little effort has been spent on discovering what was genuinely dangerous and what was not; still less on communicating to citizens what has been learned. Epidemiologists live to forecast. Economists conduct experiments. Expect the “light touch” policies of the Swedish government to attract increasing attention.

About the failure of leadership in the U.S., Leonhardt is unremitting: in no other high-income country have messages from political leaders been “so mixed and confusing.” Decisive leadership from the White House might have made a decisive difference, but the day after the first American case was diagnosed, President Trump told reporters, “We have it under control.” Since then consensus has only grown more elusive, at least until recently.

Word War I was sometimes called the Chemists’ War, because of the industrially manufactured poison gas employed by both sides, The German General Staff looked after their war production. World War II was the Physicists’ War,” thanks to the advent of radar and, in the end, the atomic bomb. It was equally said to be the Economists’ War, chiefly because of the contribution of the newly developed U.S. National Income and Product Accounts to war materiel planning.

The Covid-19 pandemic has been the Epidemiologists’ War. Next time look for economists to make more of a contribution. And hope for a more prescient and decisive president.

. xxx

The New York Times reported last week it had added 669,000 net new digital subscriptions in the second quarter, bringing total print and digital subscriptions to 6.5 million. Advertising revenues declined 44 percent. Earnings were $23.7 million, or 14 cents a share, down 6 percent from $25.2 million, or 15 cents a share, a year earlier.The news made the pending departure of chief executive Mark Thompson, 63, still more perplexing.

“We’ve proven that it’s possible to create a virtuous circle in which wholehearted investment in high-quality journalism drives deep audience engagement, which in turn drives revenue growth and further investment capacity,” Thompson said. His deputy, Meredith Kopit Levien, 49, will succeed him on Sept. 8, the company announced last month. Kopit Levien told analysts last week that the company believed the overall market for possible subscribers globally was “as large as 100 million.”

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first appeared.

Just one face

When all the world is young, lad,

And all the trees are green ;

And every goose a swan, lad,

And every lass a queen ;

Then hey for boot and horse, lad,

And round the world away ;

Young blood must have its course, lad,

And every dog his day.

When all the world is old, lad,

And all the trees are brown ;

And all the sport is stale, lad,

And all the wheels run down ;

Creep home, and take your place there,

The spent and maimed among :

God grant you find one face there,

You loved when all was young.

— “Young and Old,’’ by Charles Kingsley (1819-75)

Ambiguities of a mega-ailment

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The big – and controversy-rich -- pandemic issue now seems to be how much to reopen the public schools in a few weeks. But there can be no simple answer, especially because the disease data change daily. How to reopen – all in-person or all-remote or a hybrid -- should depend mostly on each district’s COVID-19 positivity rate and on how state policies are crafted, which can vary widely depending on demographic and political factors. And since in America local property taxes pay for much of schools’ budgets, the ability to open in various ways will also depend on local districts’ taxing and funding capacity as they try to make the expensive interior-design and other adjustments needed for reasonable safety.

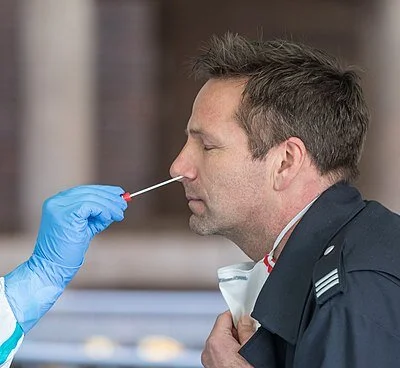

I think that there’s been too much fear that schools would be giant COVID spreaders. Might schools, at least well-run ones, be safer places for the students and those they might infect than home, where the kids could mingle with their friends and others much of the day without the mask-wearing and social-distancing supervision of teachers and other school staff? And why aren’t teachers considered “essential workers”? In any event, teachers should be among those who get regular COVID-19 testing.

As I’ve said perhaps too many times, trying to teach all classes this fall entirely on computer screens would be an intellectual, socio-economic and psychological disaster and might even jeopardize physical health more than in-person teaching, at least in some districts. Such classes cannot compare in quality with in-person learning in comprehension and retention, and some families don’t have the computers, reliable Internet connections, tech know-how or other resources to get what full benefits can be had from remote learning. Many kids have already fallen way behind in their learning since the schools were closed in March and superseded by screens, and parents’ attempts to home school, as COVID-19 spread rapidly. A lot of students have lost precious learning time, particularly those from underprivileged backgrounds.

And let’s face it: Schools also function as day-care institutions, which lets parents go to work to support their families without undue worry. And for families where parents can mostly or entirely work at home, having their children there all the time can make it very difficult to do their jobs. It packs a lot of stress.

Most parents cannot afford to send their kids to private schools, with their usually smaller classes, or hire private tutors and engage in other end runs around the public schools. Some politicians and others will use the pandemic crisis to try to further undermine public schools in favor of private ones that cater to affluent people by means of vouchers, etc. I hope there’s pushback.

Please read this editorial from The New England Journal of Medicine on why fully reopening schools in a few weeks should be a national priority:

xxx

Organizations have made a big show of “deep cleaning” surfaces to, it is hoped, kill the virus. But in fact surfaces are a minuscule threat, and much of the time and money being spent on dramatic “deep cleaning’’ would be better spent on making sure that everyone wears a mask (always have extras available to hand out), closely monitoring social distancing and adjusting, or replacing, ventilation systems so they don’t recirculate the virus through the air. The disease is overwhelmingly airborne.

But wait! Perhaps “demons” are causing COVID-19. Please hit this link.

Hello, World!

Landscape in art

“Sunset/Change (Autumn Section)’’ (1861, oil on canvas), by George Inness, in the show “Complex Terrrain(s),’’ at the Newport Art Museum, through Sept. 27.

The show examines landscape in art and how the genre has evolved over the years.

WHOI gets grant to study ocean's microbial food web

View of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and Marine Biological Laboratory buildings in the Woods Hole village of Falmouth, on Cape Cod

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

Researchers at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute (WHOI) recently received funding to study vital processes that help maintain the health of the ocean and the planet. Scientists Dan Repeta and Benjamin Van Mooy received two grants totaling $2.7 million from the Simons Foundation.

Repeta’s research will focus on phosphorus, iron and nitrogen, the nutrients that fuel microbial cycles in the ocean. Van Mooy’s research will focus on understanding the carbon and energy flow through the microbial food web. Both projects will use samples and data collected from Station ALOHA, a six-mile circle north of Hawaii, an important hub for oceanographic study. The Simons Foundation funding will also support further research into the mesopelagic zone, which plays a major role in sequestering the oceans carbon.

“We are grateful for the generous support of the Simons Foundation for basic research that is the fundamental underpinning of our knowledge of the ocean,’’ said Richard Murray, WHOI deputy director and vice president for Research. “Understanding elemental ocean processes is the equivalent of understanding the human body’s basic workings. Without this information, we cannot understand, or protect, our ocean’s and planet’s health.”

The New England Council commends the WHOI for its advances in the world of oceanographic studies and congratulates Dan Repeta and Benjamin Van Mooy on this award. Read more at News from WHOI.

Philip K. Howard: America needs a social contract to address COVID-19

The original cover of Thomas Hobbes's work Leviathan (1651), in which he discusses the concept of the social contract theory

America can’t stay closed indefinitely. But reopening America’s shops, schools and other public places is fraught with uncertainties and risks. In some jobs and settings the precautions may not be possible.

These risks and social controls conflict sharply with an American legal system that is built upon principles of uniform treatment, avoidance of risk, privacy, and, especially, free choice. Who makes these decisions? Is anyone liable when, inevitably, some people get infected?

Reopening society requires a new pandemic social contract, with new benefits and liability framework. Instead of avoiding risk, the guiding principle, as in wartime, should be to confront the risks of this common enemy and not to surrender our vibrant society in the vane hope that the virus will go away

Many institutions, retail establishments and employers will be reluctant to reopen because of fear of legal exposure. For some, the contingent liability risk may tip the balance against reopening. While it is impossible to know for certain where someone contracted the virus, it is quite easy to identify “hot spots” such as bars or meat-packing plants. Whether those businesses should reopen, and with what precautions, are decisions to be made by government, not by individual plaintiffs or their lawyers.

Trust in the new rules is essential for Americans to brave the risks and to adhere to the guidelines. A new pandemic social contract is needed that reassures Americans that they will not be left to fend for themselves if they get sick. Because the overhang of potential risk to individuals and liability to employers could significantly impact the national economy, this new social contract should be made as matter of federal law.

The best model for a reliable pandemic social contract is the workers’ compensation system, a no-fault program in which injured workers relinquish any right to sue in exchange for the employer’s agreement to fund health-care costs and wages. Because COVID-19 does not originate in unsafe workplace conditions, however, the new program should be funded predominantly by the federal government.

The new pandemic social contract could look like this:

America’s health-care patchwork is not well-suited to a pandemic. To avoid the inequities and inefficiencies of reimbursing health-care providers through thousands of different plans, the federal government should pay providers directly for all COVID treatments. The complexities of Medicare and Medicaid enrollment make them unsuitable as a conduit. A separate branch of theCenters for Medicare and Medicaid Services could be established to fund and audit COVID health-care costs, based on one guiding mandate.

Going forward, the federal government should fund COVID treatments.

Going back to work involves risks for each worker. Some will decide that it’s not worth the risk of exposure, and try to find jobs that allow them to work remotely. That will their choice. But Americans who choose to return to work should not bear the economic costs when they get ill.

Infected Americans with few symptoms should also be encouraged to quarantine so that they don’t infect co-workers. Sick employees should receive salaries as provided in state workers’ compensation schemes, except that, because the disease was not a workplace accident, the federal government should fund the vast majority of this, perhaps 90 percent. Leaving the employers with a small portion of the exposure will provide incentives to maintain safe workplace protocols, and also to oversee the validity of claims.

As part of the pandemic social contract, Congress should preempt liability except for cases of intentional misconduct—such as flouting safety guidelines. No one in America created COVID-19, and no one should be liable unless they deliberately misbehave.

Clarity in these lawsuit limitations is vital to give employers confidence that if they do not act irresponsibly, they will not be liable. No matter what the standard of liability, however, lawyers can be expected to push the envelope.

Intentional misconduct requires hard proof, but setting soft standards such as “gross negligence,” as some have proposed, can be easily circumvented by legal rhetoric. Perfect adherence to protocols is also unrealistic; sometimes the tables will end up 5 ½ feet apart instead of 6 feet. To reliably apply the liability limitations, Congress should create a special pandemic court to handle all pandemic injury claims, along the lines of the special vaccine court it created when concerns about liability basically shut down vaccine production.

Just as the federal government organizes and funds national defense, so too should it organize a comprehensive social contract for pandemics. Americans need a simple, fair framework they can rely upon to give them the confidence to go back to work

Philip K. Howard is a New York-based lawyer, author and chairman of the nonpartisan legal- and government-reform organization Common Good (and an old friend of the editor of New England Diary, Robert Whitcomb). He’s founder of the Campaign for Common Good. This essay first ran in The Hill.

Things that evoke COVID themes at Fuller Craft Museum

“Double Rocker, Back to Back” (cherry, maple and milk paint), by Tom Loeser, in the Fuller Craft Museum’s (Brockton, Mass.) group show “Shelter, Place, Social, Distance: Contemporary Dialogues From the Permanent Collection’’ through Nov. 22.

With the COVID-19 pandemic, the museum has pulled from its permanent collection items that speak to themes of home, community, isolation and other ideas /topics that the current crisis evokes.

Chris Powell: Kids learned better before Internet and education decline reflects family decline

No screen in sight

Congratulations to Connecticut billionaires Ray and Barbara Dalio for discovering at last a way to try to improve the education of poor children in the state without destroying its freedom-of-information law.

Their previous idea was for state government to create a commission of Dalio and government representatives to distribute $100 million from the Dalios and $100 million from the state while exempting the commission from the usual rules for accountability. No good explanation for that exemption was provided, so the purpose seemed to be to help both sides maneuver the money for patronage.

Fortunately the commission imploded in incompetence as it moved to fire its executive director in secret just weeks after hiring her. This embarrassment, piled on top of the unaccountability, caused the Dalios to withdraw petulantly, blaming the enterprise's incompetence on those who resented the Dalios' buying their way above the law.

But last week the Dalios and the Connecticut Conference of Municipalities announced that they will work together to provide laptop computers and internet access to the state's neediest students. Since government money won't be involved, the accountability law won't apply directly, though it will apply to municipal governments that work with the new consortium to determine who gets what.

Of course such ordinary philanthropy would have been possible in the first place without any exemption from the accountability law. Though no state appropriation appears necessary for the new plan, any appropriation will be subject to the law this time.

How much money the Dalios are prepared to give away in the new undertaking isn't determined yet. Unlike their first attempt, there won't be state matching funds. But state government was insolvent when the first undertaking was announced and now, because of the virus epidemic, its finances are even more precarious and Connecticut has needs far greater than internet connectivity.

Besides, while the Internet provides access to nearly all knowledge, it also provides access to infinite amusement, distraction and misinformation. Further, does anyone really think that the failure of poor kids in school is caused by a lack of Internet access and computers?

How did students manage to learn before those inventions, and, indeed, judging from test scores, to learn better than they do now? Who can guarantee that poor kids given laptops and Internet access at home will use them to study rather than just socialize, play games, and watch movies and cartoons?

Free laptops and Internet access may help those who are already inspired or compelled to learn, but performance in school is mainly a matter of parenting, and most poor kids are fatherless and, if their mother works, not much supervised and mentored at home by anybody. Many kids today can't even get fed at home, which is why schools now provide not only free lunches but also breakfasts and dinners, even throughout summer vacation.

Of course there are exceptions. Some kids get inspired despite all hardships. But for many kids their most important mentors are teachers, not parents, another urgent reason to get schools operating normally again. Connections between teachers and students are so much harder to build through "distance learning," which, however bravely attempted, failed this year precisely because too many parents, especially poor ones, failed to make their kids participate.

The decline of education is the decline of the family. Welfare policy may solve that problem someday but mere technology won't, at least not until somebody invents robots that make good parents.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.

Don't go out there

Horizon #34, (C-print mounted to dibond), by Jonathan Smith, at Lanoue Gallery, Boston. The gallery says:

“Smith's work consists of large scale, highly nuanced, color photographs of the stark natural beauty and inherent impermanence of landscapes.’’

Dining in the field

McCoy Stadium when they still played baseball there

— Photo by Meegs

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

On July 24, a bunch of us celebrated a friend’s birthday with dinner at a table in the middle of the field at McCoy Stadium, home of the Pawtucket Red Sox, which of course is decamping for Worcester. The stands have been eerily empty in this COVID-closed season but there were lots of widely separated but fully occupied tables at what has been turned into a very nice reservation-only, open-air restaurant this crazy summer. Luscious lobster- salad sandwiches, by the way. And the birthday girl was honored on the giant screen. I’ve been to McCoy many times but was again surprised by how big it seems for a Minor League team.

It had been a hot day, but a nice breeze over the grass kept us comfortable and then we enjoyed a gorgeous sunset. For some reason, McCoy has superb sunsets.

I felt a pang knowing that professional baseball will probably never again be played at McCoy, which more likely than not will be torn down. We always found a PawSox home game a very nice outing for out-of-towners; foreigners seemed to especially enjoy it.

I’m getting a tour soon of the “WooSox” site, where the Polar Park stadium (named after the Worcester-based seltzer company), is going up; I’ll report back. Will pandemic problems prevent it from opening on schedule next spring?

Maybe some day professional baseball will return to Rhode Island; it certainly has the population density and location to be attractive for a sports team. (I have always thought that the most interesting and dramatic place for a Rhode Island baseball stadium would have been on Bold Point, in East Providence.)

The biggest question may be: How popular will baseball be in coming years compared to other sports? Is it too late to turn McCoy into a soccer stadium?

xxx

The death on July 29 of Lou Schwechheimer from COVID-19 has saddened many people. Lou was the longtime vice president and general manager of the PawSox during the club’s heyday under the ownership of the late Ben Mondor. Lou, working with Mr. Mondor and Mike Tamburro, then the club’s president and now vice chairman, turned the organization into one of the most successful teams in Minor League Baseball.

I encountered Lou many times, and his presence was a tonic. He seemed to have endless supplies of energy, enthusiasm, ingenuity and good humor. He had a memorable capacity for making and keeping friends and boosting the community that the PawSox entertained for so many years.

Llewellyn King: America’s hyper-individualism is killing it

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

To compound the COVID-19 crisis, we have a cultural crisis. It is a crisis of our individualism.

That cultural element, precious and special, of the individual against adversity, the individual against authority, the individual against any limits imposed on free action, is at odds with the need to behave. Worse, our individualistic trait has been politicized, dragged to the right.

This aspect of American exceptionalism is now killing us, on a per-capita basis, faster than people in any other country. We are in a health crisis that demands collective action from people who revere individual freedom over the dictates of the many, as expressed by the government.

Simply, we must wear masks and stay away from groups. It works; it is onerous but not intolerable.

There is a hope, almost a belief, afoot that by the end of the year there will be a vaccine, and that the existence of a vaccine will itself signal an end to the crisis.

A reality check: No proven vaccine yet exists. Although all the experts I’ve contacted believe one will work and several might.

Another reality check: It may take up to five years to vaccinate enough people to make America safe. My informal survey of doctors finds they expect one-third of us will be keen to be vaccinated, one-third will hold back to see how it goes, and one third may resist vaccination because they’re either opposed in principle or consider it to be a government intrusion on their liberty.

If their expectation holds true, COVID-19 is going to be with us for years.

No doubt there are better therapies in the pipeline to deal with COVID-19 once the patient has reached the hospital. But that won’t affect the rate of infection. The assault on our way of life and the economy will continue; the price our children are paying now will escalate.

If you’re pinning your hopes on a vaccine, several may come along at the same time and jostle for market share. That happened with poliomyelitis: Three vaccines were available, but one failed because of alleged poor quality control in manufacture. If there is a scramble among vaccines, look out for financial muscle, politics, and nationalism to join the fray. None of these will be helpful.

So far, there has been a catastrophic failure of leadership at the White House and in many statehouses. “Say it isn’t so” is not a policy. That is what President Trump and Republican governors Ron DeSantis, of Florida, and Brian Kemp, of Georgia, have, in essence, said, resulting in climbing infections and deaths.

Americans sacrificed on a politicized cultural altar.

We know what to do: A hard lockdown for a couple of weeks would stop the virus in its tracks. It worked in New York.

We are in a war without leadership. We have governors forced to act as guerrilla chiefs rather than generals of a national army under unified leadership with common purpose.

Right now, we should hear from the political leadership about what they plan to do to slow the spread of COVID-19 and how, when this is over, they plan to rebuild: What will they do to help the 20 million to 30 million people in hospitality and retail whose jobs have gone, evaporated?

Refusing to wear a mask may have deep cultural significance for some, particularly in the West, but for all of us, restaurants are part of the fabric of our living. For most us, the happiest moments of lives have been in a restaurant, celebrating things that are precious milestones in life, such as birthdays, engagements and anniversaries.

We can’t give one cultural totem precedence over another.

More than half the nation’s restaurants may never reopen -- employing 10 percent of the nation’s workforce and accounting for 4 percent of GDP -- and the biggest helping hand to them would be to throw the Defense Production Act at manufacturing millions of indoor air scrubbers. It would increase livability for all, ending our isolation from each other.

Wash your hands, America. Don’t wring them. We can beat the virus when we fight on the same side with science and respect the commonweal.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His e-mail is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Website: whchronicle.com

Character and civilization

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882), famed essayist and a personification of the New England character

“New England likes to think it has a civilization based on character. The South likes to think it has a character based on civilization. A big difference.”

— Henry Allen, in “The Character of Summer,’’ in the July 14, 1991 Washington Post

Maine event

Bad Little Falls on the Machias River in Machias

“As if the banks were lined by spiders

tossing long, shimmering filaments

the river crawls along like prey.”

….Some have caught a fish. Four crescent tails

are nailed to my woodshed door.

For summers to come

they will draw the iridescent flies.’’

— From “Bluefish run, Machias, Maine,’’ by Paul Nelson

'Fragmented realism'

Collage made entirely of paper cut from recycled magazines, by Betsy Silverman, in her show “Cut It Out,’’ at Edgewater Gallery at Middlebury Falls, Middlebury, Vt. The Boston-based artist calls her work “fragmented realism,’’ depicting classic New England scenes in a new way.

See:

http://www.betsysilverman.com/

and:

https://edgewatergallery.co/

Rude, or just direct?

Elizabeth Bishop in 1964

“I think almost the last straw here though is the hairdresser, a nice big hearty Maine girl who asks me questions I don’t even know the answers to. She told me: 1, that my hair ‘don’t feel like hair at all.’ 2, I was turning gray practically ‘under her eyes.’ And when I’d said yes, I was an orphan, she said ‘Kind of awful, ain’t it, ploughing through life alone.’ So now I can’t walk downstairs in the morning or upstairs at night without feeling like I’m ploughing. There’s no place like New England.”

— Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979, famed poet), in Words in Air: The Complete Correspondence Between Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell (another famed poet)