Dissatisfied religionists

— Photo by Tim Valentine

The Old Ship Church (also called the Old Ship Meetinghouse) is a Puritan church built in 1681 in Hingham, Mass. It is the only surviving 17th-Century Puritan meetinghouse in America. Its congregation, gathered in 1635 and officially the First Parish in Hingham, occupies the oldest church building in continuous religious use in the United States.

The New York Times called it "the oldest continuously worshiped-in church in North America and the only surviving example in this country of the English Gothic style of the 17th Century. The more familiar delicately spired white Colonial churches of New England would not be built for more than half a century."

Within the church, the ceiling, made of great oak beams, looks like the inverted frame of a ship — thus the church’s name.

From the Unitarian-Universalist World:

“The people who colonized Hingham were eager to get as far away from the influence of the Puritans in the Massachusetts Bay Colony as they could, so they settled in Hingham, twenty miles south of Boston. Ebenezer Gay, who served as the congregation's pastor from 1718 to 1787, rejected Calvinism in favor of Arminianism, the precursor of American Unitarianism. By the end of the eighteenth century, the congregation was essentially Unitarian, according to the Rev. Ken Read–Brown, the church's minister for the last twenty years.’’

New England has a great many houses of worship, at least in part because it was settled by people who were unhappy with the Church of England, or with Rome, or with Martin Luther; or who simply had a scheme of their own they wanted to try out — usually having to do with wearing black clothes and making sure everyone behaved.

From Contemporary New England Stories (1992), by C. Michael Curtis

David Warsh: The 2016 election and the Framers’ plan

“Scene at the Signing of the Constitution of the United States,’’ on Sept. 17, 1787, by Howard Chandler Christy (1940)

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

In the autumn of 1787, citizens of the 13 American states operating under the Articles of Confederation began discussing ratification of the Constitution drafted over the summer in Philadelphia by their representatives. They debated, among other things, whether so large a country as envisaged by the framers could be expected to hold together.

Almost immediately, Anti-Federalist opponents of ratification launched attacks on various aspects of the agreement. Alexander Hamilton recruited James Madison and John Jay to write with him a series of essays in support. The “Federalist No. 1’’ appeared in the Independent Journal, in New York, on October 27, followed by 76 more, to be published the next spring with eight other essays as The Federalist: A Commentary on the Constitution of the United States.

A week before, the New-York Journal carried what we would now call an op-ed signed by an Anti-Federalist under the pen name Brutus. He wrote:

The different parts of so extensive a country could not possibly be made acquainted with the conduct of their representatives, nor be informed of the reasons on which measures were founded. The consequence will be, they will have no confidence in their legislature, suspect them of ambitious views, be jealous of every measure they adopt, and will not support the laws they pass.

In November, Madison took to the pages of the New York Packet to rebut Brutus. The “mischiefs of factions,” meaning groups of citizens united by some passion or interest adverse to the rights of others, couldn’t be eliminated without destroying liberty. Madison wrote. After all, different opinions were in the nature of humankind – about religion and government, wealth and power, banking and commerce, agriculture and manufacturing. If factions couldn’t be eliminated, you could at least hope to curb their violence.

How? By reducing both the impulse to do mischief and the opportunity to misbehave. Republican government, small numbers of citizens elected by the rest to serve as legislators, could raise the tone above that of the appeal to mob emotion to be expected of pure democracy.

A larger country, with more people choosing each representative, could do the rest. “Extend the sphere and you take in a greater variety of parties and interests,” he wrote. Great issues would ascend to the national stage; local issues would remain the business of the states. Factions would oppose factions, and the more extensive of whatever unjust majorities might arise, the greater would be the likelihood that the thieves among them would fall out.

Madison continued: “A rage for paper money, for an abolition of debts, for an equal division of property, or for any other improper or wicked project, will be less apt to pervade the whole body of the Union than a particular member of it; in the same proportion as such a malady is more likely to taint a particular county or district than an entire State.”

Madison’s essay, “The Federalist No 10,’’ is famous today as among the most influential of the collection. In “The Federalist No. 39,’’ he went on to elaborate his view that the Constitution would assure both a democracy in which all citizens had a voice and a republic in which a complicated system of checks and balances obtained between the states and the national government – “a federal, not a national, Constitution.”

All this is fresh in mind because I read recently about Brutus’s essay in The Decline and Rise of Democracy: A Global History from Antiquity to Today, (Princeton, 2020), by David Stasavage, of New York University. “What if Madison was wrong about large Republics,” Stasavage asks. What about the problem of mistrust of a distant state? What if the nation’s factions become so various and mutually antagonistic as to prove ungovernable?

Madison himself quickly came to recognize that there would have to be continuing investments to insure that citizens would continue to trust their government. By 1791, he was pursuing measures to support newspapers and subsidize their circulation. Reformers who came later proposed state-funded public education.

But public education is under fire today, and the tiered structure of the newspaper industry has suffered greatly since the proliferation of digital media and the invention of search advertising. National newspapers – The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, USA Today and Financial Times – continue to grow in influence and circulation. They have been joined by digital media – Bloomberg, Reuters, Axios and Quartz.

But the fortunes of once-important metropolitan newspapers have declined precipitously, among them Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, Boston Globe, Philadelphia Inquirer, Denver Post, Atlanta Constitution, San Jose Mercury-News and Providence Journal. Just last week, a New Jersey hedge-fund acquired at a bankruptcy auction the 163-year-old McClatchy Co., publisher of the Miami Herald, the Kansas City Star, the Charlotte Observer, and its flagship Sacramento Bee.

Here we are, some 235 years since Madison wrote “The Federalist 10,’’ the 13 states having grown to 50 states, with the District of Columbia petitioning to be declared a state. What is holding the country together? Tradition. of course, and culture: but institutionally, the answer seems to me to be the Electoral College – an ill-understood and frequently maligned invention of the framers. As Madison described it in “The Federalist 39,’’ “The executive power will be derived from a very compound source.”

The Electoral College emerged from the Connecticut Compromise, sometimes called the Great Compromise of 1787, which produced the bicameral Congress of the United States: proportional representation of the states by population in the House of Representatives, equal representation among the states in the Senate (two senators apiece), with the power to initiate taxing and spending measures reserved to the House. The election of the president follows the combination of state-based and population-based decision-making. Electoral votes are allocated to the states by the most recent census; but in almost all states, the winner of the popular votes takes the electoral votes.

Three elections in 25 years have demonstrated the significance of the Electoral College. In the 1992 election, H. Ross Perot received 19 percent of the popular vote, but didn’t win a single state and thus earned no electoral votes. In the 2000 election, litigation before the Supreme Court tipped the election to George W Bush, after the court decided that he had won a hair’s-breadth majority in Florida. His margin in the Electoral College was thus 271 to 266, though his Democratic rival Al Gore edged him in the popular vote by around half a million of more than 100 million votes cast.

In the 2016 election, Donald Trump won precisely because of the Electoral College. With more than 120 million votes cast, some 107,000 votes in three “battleground” states — Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin – provided his margin of victory — 306-232 — in the Electoral College. Had those states swung the other way, Clinton would have won, 278-260. She won the popular vote by nearly 3 million votes, 65.9 million to 63 million.

The Framers conceived of the Electoral College as essential to the federal structure of government. It forces candidates to campaign outside the states with the biggest cities, increases the political influence of small and sparsely-populated states and strengthens the two-party system, and generally binds the country together. Present-day critics, of whom there are many, assert that it sabotages the principle of majority rule by modifying the principle of one-person-one-vote. “It is rotting American democracy from the inside out,” Editorial Board member and author Jesse Wegman wrote in The New York Times the other day.

But a look at the poll projection summarized on the Web site 270towin shows just how dramatically fortunes can change based on voters’ assessment of a president’s performance in office. We won’t know how the election turns out until November. But it is significant that expectations are already leading candidate Joe Biden to extend his campaign (at least campaign expenditures in this virus-plagued year – to traditional “fly-over” states for Democratic candidates.

Disastrous as may have been the results of the 2016 election, Donald Trump’s victory must be counted as something of a success for democracy in America. In casting their votes for a reality-television star of deplorable moral character, an enormous proportion of Americans, if not a majority of voters, delivered a somber vote of no-confidence in their government in Washington – a message that would have been ignored with a popular vote determining the outcome.

Whether the sentiments of the disenchanted will wax or wane over the next few presidential cycles remains to be seen. But elections happen every four years. Disabling or eliminating the Electoral College altogether in favor of presidential election via the popular vote is a bad idea. It would disconnect the feedback system, with its shifting “battleground states,” that may equilibrate levels of trust among voters across a large and diverse nation and its national government. The Framers knew what they were doing.

. xxx

Expect two more “What Happened in 2016?” weeklies between now and the election: II, Russia; and III, the FBI.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist, book author and economic historian, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

'External spaces, interior imaginings'

"Ley Line," by Kathline Carr, at Fountain Street Fine Art, Boston, through Aug. 2. Ley lines are lines that crisscross around the globe, like latitudinal and longitudinal lines.

Ms. Carr, who lives in the Berkshires, writes:

“My process of making is one of construction and reiteration: I render abstractions of real and imagined space, while imposing diagrammic marks through those planes. My work seeks to fuse mappings of external spaces with interior imaginings and associations. I utilize materials that are meaningful to me, often employing fabrics, collage, or found objects to hone in on a particular locale or experience. The landscape interests me as a point of entry to explore isolated forms, light, and implications of human interference.’’

See:

kathlinecarr.com

and:

https://www.fsfaboston.com/

Llewellyn King: Is China slipping in hardware that could jeopardize our electric grid?

The Manchurian Candidate was released in October 1962, during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

There are new worries afoot in the electric-utility world.

The issue is the integrity of the grid and the possibility that foreign suppliers of bulk power equipment (BPE) may have introduced the technical equivalent of Manchurian candidates into the hardware that manages the system.

This represents a departure from previous concerns that have emphasized software and paid more attention to attacks aimed at the computer systems of electric utilities than to their hardware. They get millions of these attacks every day and have worked relentlessly to protect against them.

Now a new front has opened.

The battle has moved from the world of Internet technology to the hardware itself, to BPE. Leading the charge to draw attention to systems whose vulnerability may have been overlooked is Joe Weiss, a professional engineer, a veteran of the Electric Power Research Institute in Palo Alto, California, and now an independent consultant.

Weiss said in a blog, which went viral in the world of utility engineers last week, “Why would attackers hit defenses head-on when they can simply bypass them?” And that is exactly what they’re doing, he believes.

On May 1, President Trump issued the far-reaching Executive Order 13920, which prohibits the purchase of major BPE from potential adversaries, later named by the Department of Energy as China and Russia, among others.

China is the primary supplier of BPE to American utilities.

Then, on July 8, the department issued a request for information about what the electric utilities purchase and from where. It appears the government is attempting to scope the problem.

Initially, many in the industry thought the executive order was just another shot in the Trump administration’s trade war with China. But not so. It signaled what may be a big vulnerability not only in installed equipment but also equipment that is on order.

China has become the primary supplier of heavy equipment for utilities, particularly big transformers. While these have no moving parts, Weiss believes that they can have “backdoors” through which an adversary could catastrophically alter their operation.

The key, he says, may be the censors that can send false readings and bring about major disruption, and send parts of the grid haywire.

Transformers are critical to the distribution of current. They boost voltage to compensate for line losses and ultimately step down the voltage for local distribution.

This vulnerability story began after the terrorist attacks of 9/11, when a trend to look at the security of the electric grid turned to a greater concentration on IT and, some argue, away from the old regime of operational technology, where engineers took responsibility for the security of their equipment.

A cultural division opened, as I was told by the one of the nation’s top computer experts in academia.

Underlying this shift in responsibility are the workhorses of modern industry, programmable controllers, part of the larger Industrial Control Systems. These are the automated systems that do the work of managing operations in modern industry, including utilities.

The worry for the electric-utility industry is that these devices that manage the grid could be manipulated without showing up as an attack.

There is precedent for this kind of attack: The Stuxnet virus that disabled centrifuges at Iran’s Natanz nuclear facility in 2010. The United States and Israel didn’t go after the facility’s computer system — an attack that would’ve been detected — but rather after the controllers governing the centrifuges.

Last year, something big was discovered, and details are sketchy: A Chinese-made transformer at a large investor-owned utility was found to have counterfeit parts and, perhaps, backdoors through which the integrity of the grid could’ve been compromised.

Alarm bells rang at the departments of Homeland Security and Energy.

A similar or identical transformer made by JiangSu HuaPeng Transformer Company Ltd., a family owned company with a small office in San Jose, California, was seized by agents of the DHS and DOE and hustled straight to Sandia National Laboratory in Albuquerque, New Mexico, upon its arrival at the Port of Houston.

This transformer had been destined for the Western Area Power Administration’s Aluit Station, near Denver. WAPA is one of the power distribution systems owned by the government through the Department of Energy.

What, if anything, has been discovered in the transformer hasn’t been disclosed.

Everything is cloaked in secrecy, my sources tell me.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Control room in electric power plant

She's heard it before

—- Photo by Mathias Krumbholz

“An old woman by a window watching the storm —

Dark River and dark sky and furious wind

Full of green flying leaves, gray flying rain….

Daughters and grandchildren in a darkened room….

Call to her to come, to come away….

Above the wind and the crash of a porch chair

And now the thunder, she does not seem to hear

Or if she hears, she does not answer them….’’

— From “The Reading of the Psalm,’’ by Robert Francis (1901-87). He lived in Cushman Village, part of Amherst, Mass. Robert Frost much admired him.

Keet House, one of many old houses in the Cushman Village Historic District

Using saliva for COVID-19 testing

UMass Memorial Medical Center, In Worcester

— Photo by Cxw1044

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com

“The University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center, in Worcester, has begun testing on a new form of test for COVID-19, using saliva instead of a nasal swab. The pilot program will be in use for testing units on UMass Memorial’s University Campus and Memorial Campus while other locations will continue to use nasal swabs. UMass Memorial has also started to shift care back towards a more normal operations, after dedicating numerous beds and personnel to coronavirus over the last several months. Read more here. ‘‘

And these days that’s enough

“YOLO” {“You Only Live Once”?} (hand punched paint chips on board), by Peter Combe, at Lanoue Gallery, Boston

See:

https://petercom.be/press

and:

Lanouegallery.com

William Morgan: My statuary saga in tense times

Roger Williams Memorial, Prospect Terrace, Providence

— Photo by William Morgan

In Rhode Island, we might soon exorcise half of the official name of our state as a symbol of solidarity with Black Lives Matter. The state’s official name is State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. As we are removing statues that some find offensive, maybe we should take a look at some of our sculptural monuments here in Providence.

Providence Plantations was the name of Roger Williams’s colony, founded in 1636. He was one the most inclusive of all of America’s founding fathers. But the word “Plantations’’ holds unwholesome associations with the Antebellum South, echoes of Gone with the Wind and of America’s original sin of slavery.

Despite being beloved by many Native Americans and having translated the Bible into Narragansett, Williams made an unfortunate choice of nomenclature almost 400 years ago. Do we need to consider taking down images of Williams?

The statue (above) of Roger Williams overlooking the city from Prospect Terrace was the result of a competition during the 1930s, won by architect Ralph Walker and sculptor Leo Friedlander. In the spirit of those times, the composition looks like something that Mussolini ordered over the telephone.

Frédéric Bartholdi’s handsome rendition of Columbus is a version of the eponymous statue exhibited at the World Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893.

— CareerShift.com

Already gone from its South Providence neighborhood, the Christopher Columbus statue above has met the fate of many monuments to the Genoese explorer in the employ of the Kingdom of Spain. A brave sailor, Columbus opened the Western Hemisphere to development, and thus to the exploitation of native peoples.

For generations, Columbus Day was the celebration day for Italian-Americans, a long-vilified immigrant group. But today do we need to consider changing the names of Columbia University, Columbus, Ohio, and the South American country of Colombia, not to mention Venezuela, which the intrepid navigator named?

And what might we do with the Providence statues of Dante, Garibaldi and Marconi? Statues put up to honor the great Florentine poet, the George Washington of Italy and the inventor of the radio would seem fairly uncontroversial, but you never know what you might in their histories….

And not just Italians. Are there any statues of Portuguese explorers in Rhode Island? Like the retired Mississippi flag, the Portuguese banner is surely a symbol of brutal colonialism in Latin America, Asia and Africa. Right?

As for Rhode Island’s outsized role in the Civil War, our monuments honoring Union leaders should be above reproach.

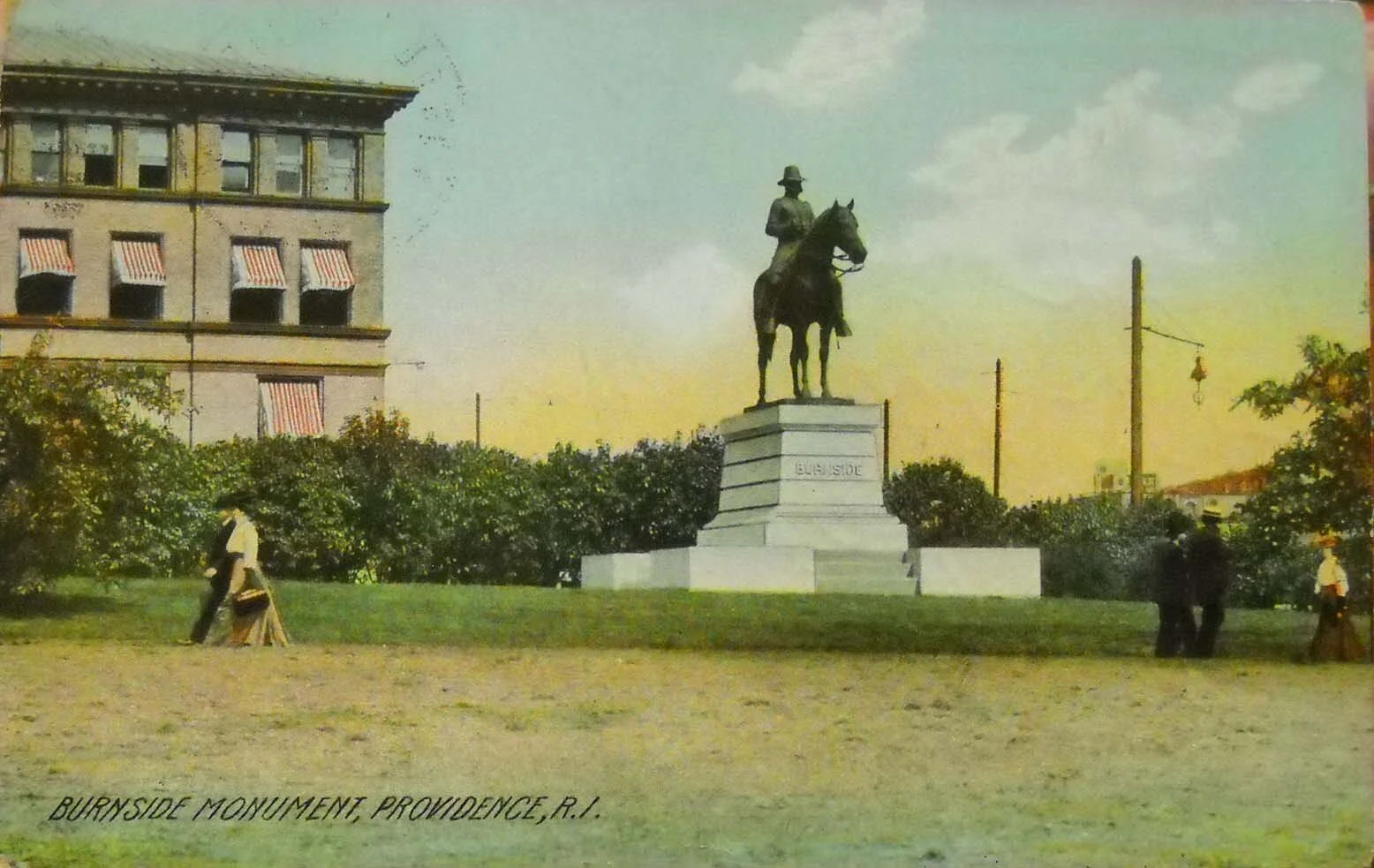

Nationally famous sculptors Randolph Rogers and Launt Thompson fashioned the Soldiers and Sailors Monument in front of Providence City Hall and the Burnside equestrian statue, respectively.

Ambrose Burnside statue, Kennedy Plaza, 1887.

Now that Theodore Roosevelt is being literally knocked from his pedestal, Spanish-American War monuments will probably soon follow. After all, the war with Spain brought American into its first big imperialist venture, after our seizure of much of Mexico in the 1840’s, as “liberators’’ of Cuba and the Philippines.

“The Hiker,’’ in Kennedy Plaza, was put up by the National Association of Spanish War Veterans, and therefore probably should go – except that its creator was a pioneering woman sculptor, Theodora Kitson. Score one for women’s rights.

“The Hiker, ‘‘ in Kennedy Plaza, Providence, by Theodora Kitson

— Photo by William Morgan

The less-than-ramrod-straight trooper in Providence’s North Burial Ground, commemorating “Citizens who served in the War with Spain, the Philippine Insurrection and the China Relief Expedition,’’ should also remain unmolested. While this soldier’s fey demeanor was probably unremarked upon in 1904, it deserves special protection.

Spanish-American War soldier, by Allen Newman, North Burial Ground, Providence

— Photo by William Morgan

Arguably, the most artistically significant sculpture in Providence adorns the entrance to the Union Trust Building, on Dorrance Street. “The Puritan and the Indian’’ is the work of America’s second-greatest sculptor (Augustus Saint-Gaudens was the greatest), Daniel Chester French, whose best-known work is the statue of Lincoln in the Lincoln Memorial in Washington.

“The Indian and the Puritan,” by Daniel Chester French

— Photo by William Morgan

French was clearly inspired by Michelangelo’s tomb figures in the Medici Chapel, in Florence. Yet “The Indian and the Puritan,” despite their beautifully idealized physiques, represent stereotypes that might be offensive. In an unequal competition of assets, the Puritan rests on a library of scholarly tomes, while the “noble savage’’ has snowshoes and a pipe.

Brown University offers the city’s richest concentration of public sculpture, ranging from the naturalism of its recent life-size (yet curiously genital-less) Kodiak bear, by British artist Nick Bibby, to the rather traditional academic copies of the über-imperialist Roman Emperors Julius Caesar and Marcus Aurelius.

Marcus Aurelius, on the Brown University campus

— Photo by William Morgan

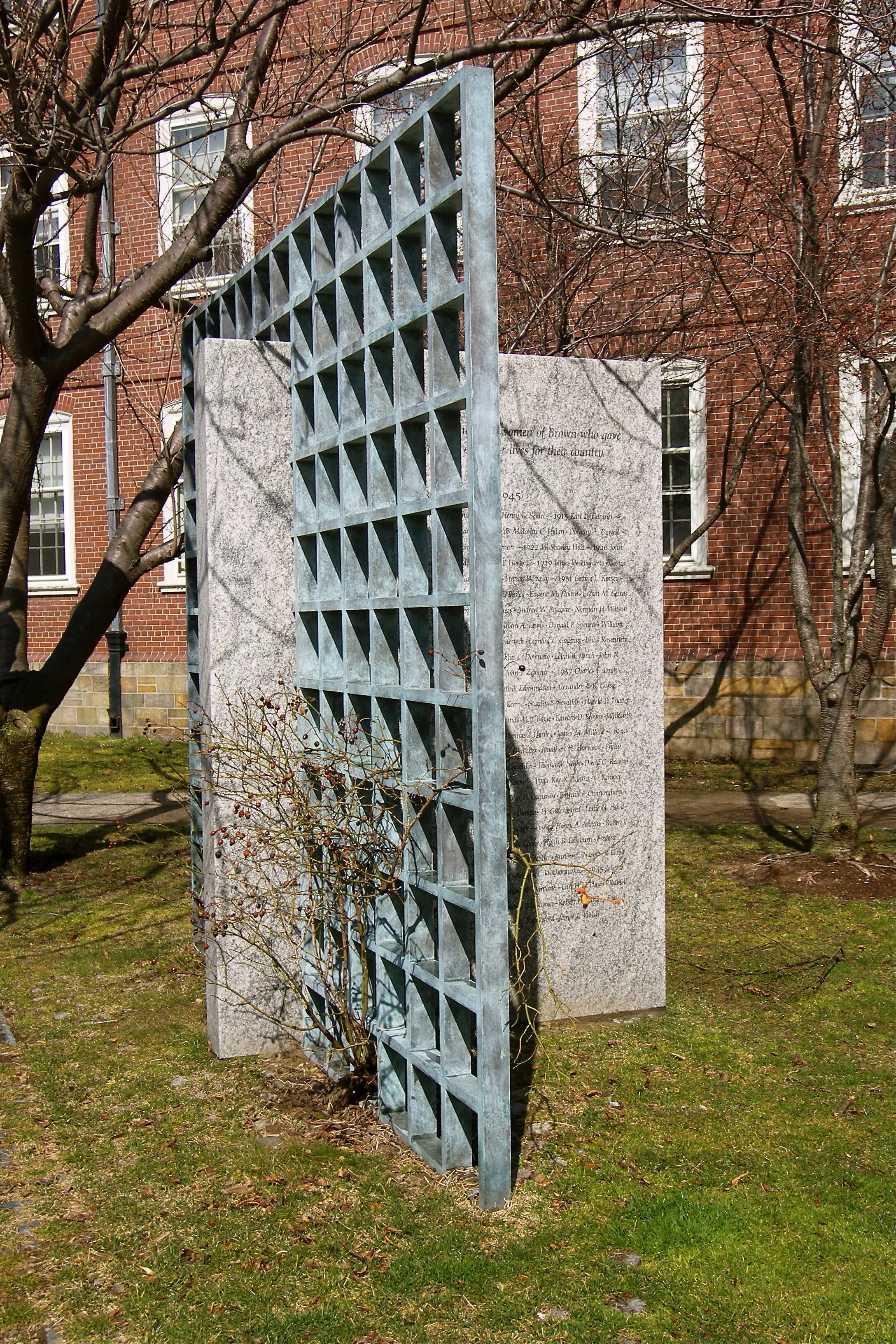

Not far from Marcus Aurelius is the Brown memorial to university alumni who died in World War II, Korea and Vietnam. After the bombast of the Civil War memorials, Richard Fleishner’s modest granite slab and bronze lattice is elegiac and refreshingly timeless.

Brown war memorial by Providence artist Richard Fleishner

— Photo by William Morgan

As with its new architecture, Brown seems to hire important designers and then is not quite sure what to do with them. We can say the same of the placement of some of the three-dimensional artwork they acquire.

Brown commissioned Maya Lin, creator of the hugely influential Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, to do a piece for the university. Instead of one of Lin’s adventurous land sculptures, Brown preferred something less bold and controversial. Lin’s slab, inscribed with a map of Narragansett Bay, is disappointing and poorly placed.

“Under the Laurentide,’’ by Maya Lin, on the Brown campus

— Photo by William Morgan

The thoroughly inappropriate placement on Brown’s College Green also lessens the impact of Brown’s real sculptural prize, “Three-Piece Reclining Figure Number Two,’’ by the great English artist Henry Moore. This is one of six castings of this piece. Moore’s bronze figures were status symbols in the 1970s – it seemed that curators of every museum or university felt they had to have one.

“Three-Piece Reclining Figure,’’ by Henry Moore, at Brown

— Photo by William Morgan

But any Henry Moore, however displayed, is always a welcome treasure. And the Brown gem demonstrates that an abstract piece with a vague-sounding and totally apolitical name can survive decades of cultural storms.

Public art is necessary to defining who we are, and can also be the focus of protest. Revolution is a hallowed Rhode Island tradition, but let us try to maintain our tradition of tolerance as we embrace new visual expressions.

William Morgan, the author of many books, is a Providence-based architectural historian and essayist.

Abortion and ancient vs. modern rights; racism in public health?

Interior of the U.S. Supreme Court

MANCHESTER, Conn.

For years the political left has argued that medical insurance should be disconnected from employment. The national medical insurance law known as Obamacare began the disconnection, establishing government-subsidized insurance for private-sector workers and granting employers religious exemptions from providing insurance for contraception and abortion.

Nevertheless, last week the left exploded in rage when the U.S. Supreme Court, with two of its four liberal justices joining the five conservatives, upheld exemptions granted by the Trump administration to religious employers, thereby disconnecting contraceptive and abortion insurance from certain forms of employment.

Connecticut Sen. Richard Blumenthal declared indignantly: "To the women of America, the message of today should be: You have a right to control your future. You have a right to control your body and your family and your health care, and we are going to fight as long and hard as necessary to make sure that right is protected."

But neither the Supreme Court nor the Trump administration has taken those rights away from anyone. The issue of the case was only who should have to pay for the insurance coverage in question -- and cost here isn't such a big deal, since most people can obtain contraceptives and even abortions for little or no cost from Planned Parenthood or similar organizations. Meanwhile government Medicaid pays for contraception and abortion for the poorest.

Besides, as Justices Samuel A. Alito Jr. and Neil M. Gorsuch wrote, if insurance for contraceptives and abortion is such an important right, the government itself could provide the insurance to everyone, not just the poorest.

The political left isn't pressing this issue out of medical necessity but rather to bludgeon people whose religious convictions the left considers backward. But the right to religious convictions, however backward they seem, is ancient and was placed in the Constitution more than two centuries ago, while the right to make someone else pay for your contraception and abortion is a very recent concept.

xxx

Now that local governments in New Haven, Windsor and Manchester, Conn., and other places have declared racism to be a "public-health crisis," what exactly is to be done about it -- and not just the supposed crisis but also the supposed racism?

Where exactly is the racism in public health? Who are the racists?

The examples offered are few and weak. Yes, the poor tend to live closer to pollution sources than the rich do, and poverty correlates with race, but housing always will be cheaper near pollution and someone always will be living closer to it than someone else.

Besides, pollution is not why the recent virus epidemic has afflicted people of color more than whites. The disparity in affliction also correlates heavily with poverty, and perhaps with biology as well, since medical authorities increasingly believe that darker skin pigment weakens immune systems by reducing the body's ability to produce Vitamin D from sunlight. (Maybe government should distribute Vitamin D pills without charge. At least that would be something.)

No, these public-health crises are being declared because cries of "Racism!" are more magical than "Open sesame!" Nobody in authority dares to talk back to such cries and attempt rational discussion, and why bother when they can be deflected with empty gestures? These days if racism is invoked as the cause of a problem, any local government might be glad to declare a crisis in flat tires, paper cuts or burnt toast.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.

Stare at it while you can

“Summer Reflection’’ (pastel), by Ann Coleman, at Ann Coleman Gallery, Wilmington. Vt. See:

Asking Siri

Screen shot from video “Hey Siri, I’m Alone,’’ by Avery Forbes, at the Hampden Gallery of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst; the gallery remains closed for in-person viewing because of the pandemic.

In this short video, Ms. Forbes calls on Siri to talk about loneliness and related questions in a series of conversations. More and more screens appear as the conversations multiply, until connectivity problems close down Siri and the artist and the viewers are left without closure.

'Bloodless absolutes'

James Buchanan (1791-1868)

“There is no pleasing New Englanders, my dear, their soil is all rocks and their hearts are bloodless absolutes.’’

— From the 1974 John Updike play {James} Buchanan Dying, about the U.S. president who preceded Abraham Lincoln in office

Disease threatens beech trees

North American beech tree in the fall

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

The Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM) is asking residents to monitor beech trees for signs of leaf damage from beech leaf disease (BLD). Early symptoms include dark striping on a tree’s leaves parallel to the leaf veins and are best seen by looking upward into a backlit canopy.

The dark striping is caused by thickening of the leaf. Lighter, chlorotic striping may also occur. Both fully mature and young, emerging leaves show symptoms. Eventually, the affected foliage withers, dries, and yellows. Drastic leaf loss occurs for heavily symptomatic leaves during the growing season and may appear as early as June, while asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic leaves show no or minimal leaf loss. Bud and leaf production also are impacted.

BLD was detected in the Ashaway area of Hopkinton and in coastal Massachusetts this year, according to DEM. Before these findings, the disease was only known to be in Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, and Connecticut. The disease is caused by a kind of nematode, microscopic worms that are the most numerically abundant animals on the planet.

While there are good species of nematodes, the BLD nematodes cause leaf damage that leads to tree decline and death. At this time, they are known to only affect American, European, and Oriental beech species. Currently, there is no defined treatment, as nematodes are difficult to control in the forest environment. Research is underway to identify possible treatments for landscape trees.

All ages and size of beech are affected, although the rate of decline can vary based on tree size. In larger trees, disease progression is slower, beginning in the lower branches of the tree and moving upward. The disease also appears to spread faster between beech trees that are growing in clone clusters, as it can spread through their connected root systems. Most mortality occurs in saplings within two to five years. Where established, BLD mortality of sapling-sized trees can reach more than 90 percent, according to DEM.

The state agency encourages homeowners and forest landowners to monitor their beech trees and report any suspected cases of BLD to DEM’s Invasive Species Sighting Report.

Colder, bluer and safer

All six New England states are in WalletHub’s top 10 safest states.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ on GoLocal2.com

Another study indicates that Blue States are generally much better places to live than Sunbelt Red States (unless you really hate winter). Consider WalletHub’s most recent ranking of the 10 safest and 10 least safe states in America as measured by 53 indicators. The 10 safest, in order of safety, are: Maine, Vermont, Minnesota, Utah (Red State but with all those civic-minded, charitable and clean-living Mormons), Wyoming (Red State with very low population density), Iowa (Purple State), Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Connecticut and Rhode Island.

The 10 most dangerous , from worst to less worse: Mississippi, Louisiana, Florida (Purple State) Arkansas, Texas, Oklahoma, Missouri, Alabama, Georgia and South Carolina.

The most dangerous states have high poverty levels, generally poor public education and very loose guns laws. But the political leaders of these states have tended to be adept at using social issues, including racial tensions, gun rights and abortion, to distract much of the population from policies that hurt them.

This reminds me that in 2004, historian and journalist Tom Frank published an entertaining book called What’s the Matter With Kansas about the art of getting people to vote against their own economic self-interest through promotion of “populist,’’ “anti-elitist’’ conservatism. This has served to benefit the real American “elite’’: the plutocracy, such as the Kochs, whose leaders are adept at suckering Americans to give the plutos big tax cuts and environmental and other deregulation. Unfortunately, few suckers read the book: They were too busy watching Fox “News’’ or listening to Limbaugh.

To read the WalletHub story, please hit this link.

Drive-by whimsy on the Cape

Section of the “Garden Grove’’ installation by Alfred Glover, at the Cahoon Museum of American Art, in Cotuit, Mass. (on Cape Cod), through the end of the year.

The museum, which is still closed for in-person tours because of COVID-19,

explains that “Garden Grove,’’ part of the museum’s Streetside series, is a drive-by exhibition visible from the street along Route 28. It consists of “whimsical tree sculptures made of metal and wood, marked by giant ginkgo and philodendron leaves, beautiful flowers and strange yet endearing animals like nesting birds and spotted dogs.’’

Keolis gets 4-year extension to run MBTA commuter rail

MBTA F40 locomotive idling on Track 1 at Route 128 station, in Westwood, Mass.

—Photo by MBTafan2011

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

“In mid-June, New England Council Member Keolis Commuter Services secured a four-year extension of its contract to operate the MBTA’s Commuter Rail service. This contract aims to provide cost certainty and create incentives for improving commuter rail service for the MBTA.

“As the MBTA’s Commuter Rail operating partner, Keolis has provided all mechanical, transportation, and engineering services since 2014. Keolis has since added 10,000 more trains per year, piloted a new weekend train service, and implemented various customer improvements. Keolis has also updated and expanded safety protocols, as well as provided more resources for the MBTA Safety Department. Under the new four-year extension, Keolis seeks to invest in the MBTA’s infrastructure, address fare-evasion and non-collection issues, and provide incentives for immediate improvements in Commuter Rail service through performance payments.

“Keolis CEO and General Manager David Scorey said, “This extension balances taxpayer and passenger needs as it keeps costs low while also enhancing the passenger experience, including a focus on providing more capacity, further increasing on-time performance and accelerating capital delivery. On behalf of our Keolis Boston team, we look forward to continuing our collaborative work with the MBTA and building upon the successful initiatives we’ve delivered together for the Commonwealth and our Commuter Rail passengers.”

Read more in the MBTA’s press release or in The Boston Globe.

New England a biotech power against COVID-19

Kendall Square in Cambridge, as seen from across the Charles River in Boston. It’s the epicenter of the New England biotech sector.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The economy may or may not recover soon from the pandemic, but in any case New England’s role as a world center for health-related science will probably continue to grow. Indeed, the search for a vaccine for COVID-19 and new treatments for that and other illnesses, old and new, will tend to accelerate this growth. It’s a bit macabre to say so, but New England’s economy could benefit from COVID-19. Researchers in the region are hard at work trying to develop vaccines and treatments against the disease.

That’s not to minimize the damage done to other important regional sectors, especially higher education, and of course the region’s universities do a great deal of life-sciences research. It’s complicated.

Just look at the plan by life-sciences company IQHQ to buy the 26-acre headquarters and campus of GCP Applied Technologies, in North Cambridge, Mass., for $125 million. GCP makes chemicals and construction materials.

The Boston Globe reports that the “once light-industrial area is rapidly transforming into a hub for labs and housing. It’s one of several areas around the region that are drawing tech and life science companies looking for cheaper or roomier alternatives to {Cambridge’s} Kendall Square.’’

To read The Globe’s story, please hit this link.

This is, of course, the sort of business that Rhode Island is trying to get, especially for the land freed up in downtown Providence by the moving of Route 195.

Elizabeth Markovits/Amber Douglas: Pandemic innovation at Mount Holyoke College

The main gate of Mount Holyoke College, in the college-rich Connecticut River Valley.

From The New England Board of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Students choose small liberal arts colleges for the learning that unfolds when they are deeply immersed in intellectual collaboration with faculty and with one another. The photos that festoon our promotional materials aren’t mere marketing—we spend a lot of time with one another in close quarters. Faculty and staff are truly invested in student success, working creatively to develop exceptional experiences for our students.

Students themselves collaborate deeply both inside and outside classroom environments, facilitated by a high-density, residential campus. We do this work with the goal of helping the next generation develop the critical thinking and communication skills they need to excel for the rest of their lives—skills that seem more important with each passing day.

So how is that model going to work now when the name of the game is social distancing?

While at times, the challenge of delivering the educational experience for which we are known has seemed insurmountable, on our campus, a practical, flexible new model has begun to emerge—one built around a clear understanding of exactly who our students are, the issues they’ll face this fall, and the near certainty that the college will need to meet a wide range of different learning contexts. We call it flexible immersive teaching—FIT.

Like other institutions, we hope to return to campus this fall with students in residence. But we already know that not every student will be able to join us in person, whether because of immigration and travel issues or because of health and safety considerations. Like many of our colleagues at other liberal arts colleges, we’ve never been comfortable with the models known as “hybrid” or “hy-flex” learning, and the plans to offer a mixture of in-person and online course options are problematic for us.

Creating distinct paths through the curriculum raises significant concerns around diversity and inclusion. Depending on how students are selected or elect to return to campus in the fall, Hy-Flex models, characterized by offering the students a choice of asynchronous, online learning or real-time synchronous sessions, may reify pathways that fall along social classifications like race and class, exacerbating divisions already deepened by current health and political crises.

Offering a subset of online courses to remote students may mean institutions lose one of their greatest strengths: offering community members the opportunity to learn from one another across difference. Diverse perspectives are essential to learning, now more than ever. We fear that distinct communities, now separated by the pandemic, will result in differentiated learning experiences that undermine the sense of community that so many of us strive to create on campus. We must meet students where they are, in flexible modes, in order to stay true to our mission of inclusive excellence.

On our campus, as we worked through these issues, we listened deeply to faculty, staff and student concerns, including representatives from each of these constituencies in our planning groups. Rather than forging ahead to get back to normal as soon as possible, we listened first. We heard a yearning to return to the sense of intellectual excitement that marks the liberal arts experience—the shared discovery of new authors and conceptual frameworks to help make sense of the world around us as it changes as breakneck speed, the close collaboration between students on an art exhibit for a class, performing choral music for the community, introducing students to robotics workshops in our MakerSpace—but also a concern that workloads were doubling and tripling at a time when faculty had lost childcare, research opportunities and a sense of physical safety in the world.

We heard the need to come up with a model that will allow us to get as many students as possible back on campus—offering students more equal learning contexts and preserving staff jobs—but also a need to protect the health and safety of our community. We also heard from our students that there was significant cognitive drain when they had to switch between so many courses and tools in the emergency remote period.

As we looked at our options, FIT emerged as the best model. We are working to get as many students back into residence as health guidelines and immigration controls will allow. Meanwhile, our curriculum will be designed to work fully in digital formats, accessible to students residing on campus and around the world. However, this is not traditional online teaching, which was designed for working adults to access on their own time and own pace. Instead, we want students to come together in real time to collaborate with one another and faculty, using technology in smart ways to close the distance required by the pandemic.

Our curriculum centers on accessible, robust, active learning to recreate the immersive experience. With the FIT model, we can offer students a rigorous program of intellectually engaged work, collaboration with one another, and direct access to a faculty deeply invested in their success, no matter where they are. As we construct something entirely new, student success and faculty development must be more tightly intertwined than ever.

Mount Holyoke’s FIT model at a glance:

Delivered online to maximize student and faculty accessibility

Emphasis on real-time interaction to ensure immersive experience and inclusion for all students Modular semester: two 7.5-week modules to allow students and faculty to focus more deeply on each course

Classes take place between 8 a.m. and 10:30 p.m. to accommodate students abroad.

This is a radical change—and it’s not easy. In our case, we have already upended a great deal of how we normally operate.

In May, our faculty voted to adopt a modular system of two 7.5-week modules per semester. Taking the traditional 4-5 courses at the same time in these new formats, in environments marked by home distractions or 12-hour time differences, represents a huge additional cognitive load for students and we are too committed to their success to set them up for an unnecessary additional burden.

We’re using a broader expanse of hours in a day—from 8 a.m. to 10:30 p.m.—to ensure that students who live abroad can access our curriculum and to improve social distancing on campus. The modular semester with a reimagined daily schedule allows for students to elect individualized pathways in concert with their learning environments, but always in community with their fellow students.

Within the FIT model, these structural changes are married with innovative pedagogical practices that will enable faculty to respond to the emergent changes and events that affect student learning, fostering resiliency and continued growth and learning in our students. The adaptability of this approach allows us to be responsive to the uncertainty to come, whether in response to COVID, the upcoming national election or whatever else comes our way. The fall, indeed the coming academic year, cannot be business as usual. To act as if things have not changed sets students and faculty alike for disappointment and frustration.

We are also making significant investments in educational technology and asking everyone on campus to learn new tools and work with new materials. Reimagining classes in digital formats means re-designing from the ground up in many cases, putting the learning goals at the center, rather than a demand to be in-person. For example, if we can’t all be together in person or work together without masks and physical distance, what does it mean to grow as a lab scientist? As a violist in an orchestra? As an actor in a theater program? As a new student learning a language for the first time? We have been inspired and encouraged by our faculty when listening to their ideas and have made investments in the technology tools to facilitate these innovations. These changes require significant commitments from faculty and staff, who are postponing other plans and working through nights and weekends to redesign courses. But we view this level of radical change as absolutely necessary in order to preserve our commitment to the success of each and every student who has chosen Mount Holyoke.

In higher education, we’ve all known that disruptive change is ongoing and inevitable, even if only a year ago, few of us would have anticipated that a global pandemic would be the catalyst. Some colleges and universities will not survive this crisis. Among those that do survive, how will their core principles be affected? Which will endure, which will change and which will be jettisoned entirely?

We believe those that emerge with their principles intact are best prepared to lead in the future. At Mount Holyoke, we know exactly what makes our model special, and we’re undertaking the hard, sometimes painful, work of preserving it, even as the modes of delivery have changed dramatically.

Ultimately, we’re doing exactly what we work so hard to prepare students to do in the world long after they graduate: Be flexible, be resilient and stay true to their principles.

Elizabeth Markovits is director of the Teaching & Learning Initiative and a professor of politics at Mount Holyoke College, in South Hadley, Mass. Amber Douglas is dean of studies and associate professor of psychology at Mount Holyoke.