Mystical art

“Mystic River - Estuary Moon,’’ by Jen Fries at the Brickbottom Artists Association, Somerville, Mass.

View of the real Mystic River, in Medford, Mass.

— Photo by Daderot

'Beyond the call of duty'

Walter Camp as Yale's football captain in 1878

“There’s no substitute for hard work and effort beyond the call of duty.’’

— Walter Camp (1859-1925), often called “The Father of American football.’’ His first fame came as a player and later as the coach of Yale’s football team. He was in on the beginnings of what became the Ivy League (Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Dartmouth, Brown, the University of Pennsylvania, Cornell and Columbia).

There will be no Ivy League football this fall because of COVID-19.

We need even more this year

“Fifty Shades of Blue,’’ by Ponnapa Prakkamakul, in her show at Kingston Gallery, Boston, July 29-Aug. 23. A Thai-American, she’s a Boston-based painter and landscape architect.

See kingstongallery.com and https://pprakkamakul.wixsite.com/pnnp

Don Pesci: Things should have been opened three months ago with current rules

A waitress at a local eatery, closed for four months by Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont’s ever changing executive orders, pops the question.

Her eatery is partially opened, but forbidden to serve more than half its regular clientele, many of whom will disappear if the eatery is not permitted to make a sustainable profit to pay the business’s overhead and its dwindling staff.

“If this place can be opened now, why couldn’t it have been opened” under the same severe regimen “three months ago?” the befuddled waitress asks.

Good question, but the common sense answer to the waitress's question will not be forthcoming from Governor Lamont or its waylaid legislative leaders, all Democrats, in the state’s seriously suspended General Assembly. The common sense answer to the question is simple and unambiguous. There is no reason why restaurants in the state should not have remained open during the pandemic four months ago. If social distancing, face masks, frequent disinfections of eating areas, and reducing by 50 percent a restaurant’s usual clientele, work now to prevent the spread of Coronavirus, the same measures would have produced the same result four months earlier.

An elementary school teacher asks this question: Why were elementary schools closed during the politically caused crisis?

Good question. We know – and have always known – that lethality among school children 14 years old and younger infected with Coronavirus has been hovering near zero. Why then were elementary schools in Connecticut shut down? The most frequent answer to this question is highly problematic. Children who are asymptomatic and who very likely had developed herd immunity, the historic prophylactic in viral contagions, can infect older adults. And these older adults are much more likely to die from the infestation than young children. Elementary-school closures are, in fact, a “save the elders” project.

Very good, how has Connecticut gone about saving the elders? In Connecticut and New York about 60 percent of those who died with – not of – Coronavirus were sequestered in nursing homes. We were protecting these elders by forbidding their relatives from eyeballing their care while, at the same time, failing to provide protective gear to the staff, heroes all, of nursing homes. And politicians in Connecticut knew – right from the beginning of the Wuhan infestation – that elders of a certain age, many of whom had medical preconditions that lethalized Coronavirus, were most susceptible to the Coronavirus grim reaper.

Well now, there is a bill before the gubernatorially suspended General Assembly right now that removes partial immunity from police officers across the state, all of whom will be susceptible to asset-swallowing suits filed by “defund the police” political agitators. Will partial immunity be removed from those politicians who are principally responsible for the carnage in Connecticut's nursing homes?

Never mind the oversight, we are told, the problem has now been corrected by Lamont, his political cohorts, and Dr. Close-The-Barn-Door-After-The-Horse-Has-Left. Not to worry; elder habitués of nursing homes who survived the political inattention of preening politicians are now, at long last, safe.

People wonder why the death count in Connecticut and New York are down, a cousin unable to attend the funeral of his uncle remarks – they removed the deadwood and are now taking their bows for having solved problems they themselves had created. They’re like the firefighter-arsonist who sets fires so that he can put them out and read about his courageous exploits in the morning paper.

It is perhaps unpragmatic at this point to hope that businessman Lamont and the Democrat leaders in the General Assembly will realize that Connecticut’s economy, artificially sustained by President Trump’s military- hardware acquisitions and the Wall Street casino, is weak at it core and will be further weakened by unnecessary shutdowns. Businesses lost to the Lamont shutdowns are irrecoverable, and there is yet another ten year recession grinning evilly at the state from the political wings.

Connecticut, now a beggar state, will attempt to squeeze money from the Washington, D.C., larder. Even now, Sen. Richard Blumenthal is hoping to wrest billions of dollars from the impeachable Trump administration, and there is not a journalist in sight who will summon up courage enough to ask him whether he would favor yet another Connecticut tax bump so that Democrats in the General Assembly will be spared the indignity of cutting union-labor costs.

When Connecticut –which has much more in common with dispensable nursing home patients than the state’s sleepy media realizes – finally disappears beneath the waves, who will be permitted to attend its funeral?

Don Pesci is a Vernon, Conn.-based columnist.

Annie Sherman: Offshore wind turbines can benefit fishing

Wind turbines of Denmark

Since the Block Island Wind Farm, four years ago, pioneered U.S. offshore wind development, the United States has positioned itself to become a world producer of electricity in this renewable-energy sector. Turning the wind’s kinetic energy into electrical power is gaining popularity, so much so that 2,000 offshore wind turbines could be erected off the East Coast in the next 10 years.

But with growth comes questions and resistance, so scientists and environmental advocates across the country and in Rhode Island are seeking opportunities to expand offshore renewable energy while reducing environmental risks.

With world-class fisheries and wildlife in Ocean State waters, the potential for victory seems on par with ruin. So it’s vital to understand how the trifecta interacts symbiotically: offshore wind facilities, current recreational and commercial uses, and the existing ecosystem.

“As we experience this growth, we see that the state and local decision-makers, resource users, and other end users are struggling to keep up with the decisions they’re having to make and also understand the potential impact it may have on existing activities and natural wildlife,” said Jennifer McCann, director of U.S. coastal programs at the University of Rhode Island’s Coastal Resources Center. “While some places in Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Europe have been working in this game for many years, there are others who are just beginning to ask questions and get their bearings on this growth. Given this growth is likely, [we need to] better understand how can we minimize the effects on existing future uses and wildlife.”

The development of offshore renewable energy has already exploded in Europe. WindEurope estimates that it now has offshore wind capacity of 22.1 gigawatts from 5,047 grid-connected offshore wind turbines across 12 countries, with 502 turbines installed last year alone. Scientists and researchers there already are coming to terms with the risk and impacts, both positive and negative, of offshore wind turbines.

Sharing their knowledge about the U.S. market in a June webinar, moderated by McCann, with Rhode Island Sea Grant and URI’s Graduate School of Oceanography, two experts said the impacts on the environment are steep. They advocated for proper management and reduced activity to maintain a healthy marine environment.

Jan Vanaverbeke, a senior scientist at the Royal Belgian Institute for Natural Sciences, and Emma Sheehan, a senior research fellow at the University of Plymouth in the United Kingdom, presented more than a decade of research from investigating the change in biological diversity and ecological interactions resulting from offshore renewable-energy structures.

Their research began at the smallest scale, with tiny marine animals and microorganisms inhabiting a turbine when it’s first installed, Vanaverbeke said. Huge numbers of this diverse marine life make a home at the base of these 600-foot-high, 200-ton turbines affixed to the seabed. This area also attracts other animals such as fish and crustaceans. They noted how offshore aquaculture and offshore energy infrastructure can support each other and improve the diversity of marine ecosystems.

“Abiotic effects, like currents, vibration, noise, and electromagnetic fields, will have an affect on the biology,” Vanaverbeke said. “In this case, it would deliver food for society, because certain fish species, like cod and pouting, were attracted to turbines. … What we see in the scour protection layer [a layer of material to protect erosion around the turbine] shows increased diversity, giving additional complexity and shelter for species.”

He also saw evidence of this conflicted cause-and-effect relationship when additional marine animals were drawn to the turbines, as they affected sediment and water quality. Taking organic matter and food from the water, they also excrete matter, which sinks to the seabed and negatively alters the sedimentary environment.

“Offshore wind farms actually do change the habitat and the environment,” Vanaverbeke said. “Research will inform you of consequences of those changes, and how to understand what this change will mean for the larger marine ecosystem. We actually want to apply this knowledge for marine spatial planning. We can see where to put the wind farm, where is the best place from an ecosystem perspective. We have to know about carrying capacity for aquaculture activities. We can also use this knowledge for a better wind farm design, in such a way that they would contribute to nature restoration and conservation, or we can play around with the complexity of the scour protection layer and use it as a nature restoration tool.”

Sheehan expanded on their research with her analysis of ecological interactions between offshore installations and the potential benefits of ambitious management. Highlighting Marine Protected Areas (MPA), a fresh or saltwater zone that is restricted to human activity, Sheehan focused on ecosystem-based fisheries management and offshore installations that have the potential to be super MPAs, by excluding destructive fishing practices and adding habitat.

She noted the term “ocean sprawl,” similar to urban sprawl, which is becoming more widely known as pressure increases for offshore energy installations.

Sheehan said it’s important to consider the benthos and their associated fish communities, because they are the foundation for the entire marine ecosystem.

Reducing or eliminating bottom fishing, which she said is destructive of rocky reefs and sediment habitats, is one way to protect these important marine areas. In one MPA she has been studying for 13 years, scallop dredging was prohibited, which ultimately allowed reef-associated species to return.

Since the siting of most offshore wind facilities is on these habitats, Sheehan advocated for installations to be progressively managed like de facto MPAs, to support essential fish habitats and protect the seabed.

“There is lots of potential for environmental benefit of co-locating offshore aquaculture with offshore renewables from an environmental point of view, but also from an economic point of view, because sharing space is going to be the only way we can move forward for this industry,” Sheehan said. “If bottom-towed fishing is excluded from the whole site, offshore developments can have positive effects on the ecosystem, increase ecosystem services, support other fisheries, and help us move toward a carbon-neutral society.”

Annie Sherman is a freelance journalist based in Newport, R.I., covering the environment, food, local business, and travel in the Ocean State and New England. She is the former editor of Newport Life magazine, and author of Legendary Locals of Newport.

Phil Galewitz: Long, long delays in getting COVID-19 test results from CVS, etc.

Elliot Truslow went to a CVS drugstore on June 15 in Tucson, Arizona, to get tested for the coronavirus. The drive-thru nasal swab test took less than 15 minutes. (CVS is based in Woonsocket, R.I.)

More than 22 days later, the University of Arizona graduate student was still waiting for results.

Elliot Truslow had a drive-thru COVID test at a CVS in Tucson, Arizona, on June 15. CVS told Truslow to expect results in two to four days, but 22 days later, still nothing.

Truslow was initially told it would take two to four days. Then CVS said five or six days. On the sixth day, the pharmacy estimated it would take 10 days.

“This is outrageous,” said Truslow, 30, who has been quarantining at home since attending a large rally at the school to demonstrate support of Black Lives Matter. Truslow has never had any symptoms. At this point, the test findings hardly matter anymore.

Truslow’s experience is an extreme example of the growing and often excruciating waits for COVID-19 test results in the United States.

While hospital patients can get the findings back within a day, people getting tested at urgent care centers, community health centers, pharmacies and government-run drive-thru or walk-up sites are often waiting a week or more. In the spring, it was generally three or four days.

The problems mean patients and their physicians don’t have information necessary to know whether to change their behavior. Health experts advise people to act as if they have COVID-19 while waiting — meaning to self-quarantine and limit exposure to others. But they acknowledge that’s not realistic if people have to wait a week or more.

Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms, who announced Monday that she had tested positive for the virus, complained she waited eight days for her results in an interview on MSNBC Wednesday. During that time, she held a number of meetings with city officials and constituents — “things that I personally would have done differently had I known there was a positive test result in my house,” she said on “Morning Joe.”

“We’ve been testing for months now in America,” she added. “The fact that we can’t quickly get results back so that other people are not unintentionally exposed is the reason we are continuing in this spiral with COVID-19.”

The slow turnaround for results could also delay students’ return to school campuses this fall. It’s already keeping some professional baseball teams from training for a late July start of the season. The lag times could even foil Hawaii’s plan to welcome more tourists. The state had been requiring visitors to quarantine for 14 days, but it announced last month that starting Aug. 1 that mandate would be lifted for people who could show they tested negative within three days before arriving in the islands.

In California, Gov. Gavin Newsom noted the problem when addressing reporters Wednesday. “We were really making progress as a nation, not just as a state, and now you’re starting to see, because of backlogs with [the lab company] Quest and others, that we’re experiencing multiday delays,” he said.

The delays even apply to people in high-risk, vulnerable populations, he said, citing a massive outbreak at San Quentin State Prison, which has been sending its tests to Quest. The state is now looking at partnering with local labs, hoping they can provide faster turnaround.

Dr. Amesh Adalja, an infectious disease expert at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore, said the long waits spell trouble for individuals and complicate the national response to the pandemic.

“It defeats the usefulness of the test,” he said. “We need to find a way to make testing more robust so people can function and know if they can resume normal activities or go back to work.”

The problem is that labs running the tests are overwhelmed as demand has soared in the past month.

Azza Altiraifi of Vienna, Virginia, got her COVID test at CVS on July 1. She still has symptoms, including fatigue — but as of July 7, she was still awaiting the result.

“We recognize that these test results contain actionable information necessary to guide treatment and inform public health efforts,” said Julie Khani, president of the American Clinical Laboratory Association, a trade group. “As laboratories respond to unprecedented spikes in demand for testing, we recognize our continued responsibility to deliver accurate and reliable results as quickly as possible.”

Dr. Temple Robinson, CEO of Bond Community Health Center in Tallahassee, Florida, said test results have gone from a three-day turnaround to 10 days in the past several weeks. Many poor patients don’t have the ability to easily isolate from others because they live in smaller homes with other people. “People are trying to play by the rules, but you are not giving them the tools to help them if they do not know if they tested positive or negative,” she said.

“If we are not getting people results for at least seven or eight days, it’s an exercise in futility because either people are much worse or they are better” by then, she said.

Given the lag in testing results from big lab companies, Robinson said her health center this month bought a rapid test machine. She held off buying the machine due to concerns the tests produced a high number of false-negative results but went ahead earlier this month in order to curtail the long waits, she said.

Robinson doesn’t blame the large labs and points instead to the surge in testing. “We are all drinking through a firehose, and none of the labs was prepared for this volume of testing,” she said. “It’s a very scary time.”

Azza Altiraifi, 26, of Vienna, Virginia, knows that all too well. She started feeling sick with respiratory symptoms and had trouble breathing on June 28. Within a few days she had chills, aches and joint pain and then a needling sensation in her feet. She went to her local CVS to get tested on July 1. She was still awaiting the result July 8.

What is most frustrating about her situation is that her husband is a paramedic, and his employer won’t let him work because he may have been exposed to the virus. He was tested July 6 and is still awaiting news.

“This is completely absurd,” Altiraifi said. She also worries that her husband may have unknowingly passed on the virus on one of his ambulance calls to nursing homes and other care facilities before he began isolating at home. He has not shown any symptoms.

Altiraifi, who still has symptoms including fatigue, said she was initially told she would have results in two to four days, but she was suspicious because after using a nasal swab to give herself the test, the box to put it in was so full it was hard to close.

Charlie Rice-Minoso, a spokesperson for CVS Health, said patients are waiting five to seven days on average for test results. “As demand for tests has increased, we’ve seen test result turnaround times vary due to temporary processing capacity limitations with our lab partners, which they are working to address,” he said.

In South Florida, the Health Care District of Palm Beach County, which has tested tens of thousands of patients since March, said findings are taking seven to nine days, several days longer than in the spring.

CityMD, a large urgent care chain in the New York City area, said it now tells patients they will likely wait at least seven days for results because of delays at Quest Diagnostics.

Quest Diagnostics, one of the largest lab companies in the United States, said average turnaround time has increased from three to five days to four to six days in the past two weeks. The company has performed nearly 7 million COVID tests this year.

“Quest is doing everything it can to add testing capacity to reduce turnaround times for patients and providers amid this crisis and the unprecedented demands it places on lab providers,” said spokesperson Kimberly Gorode.

At Treasure Coast Community Health in Vero Beach, Florida, officials are advising patients of a 10- to 12-day wait for results.

CEO Vicki Soule said Treasure Coast is deluged with calls every day from patients wanting to know where their test results are.

“The anxiety on the calls is way up,” she said.

Julie Hall, 48, of Chantilly, Virginia, got tested June 27 at an urgent care center after learning that her husband had tested positive for COVID-19 as he prepared for hip replacement surgery. She was dismayed to have to wait until July 3 to get an answer.

“I was thrilled to be negative, but by that point it likely did not matter,” she said, noting that neither she nor her husband, Chris, showed any symptoms.

“It was awful and terrible because of the unknowns and not knowing if you exposed someone else,” she said of being quarantined at home awaiting results. “Whenever you would sneeze, someone would say ‘COVID’ even though you feel completely fine.”

Senior correspondent Anna Maria Barry-Jester in California contributed to this article.

Phil Galewitz is a reporter for Kaiser Health News.

Phil Galewitz: pgalewitz@kff.org, @philgalewitz

They're run from Greenwich

Indian Harbor Yacht Club, in Greenwich

— Cliff Asness, financier

'They would believe the lie'

The Myles Standish Burial Ground, in Duxbury, Mass. It’s the final resting place (between the cannons) of several well-known Pilgrims who arrived on the Mayflower in 1620, including Captain Myles Standish, and was the location of Duxbury's first meeting house. It was in use from about 1638 until 1789, at which point the cemetery was abandoned. It was reclaimed in 1887 by the Duxbury Rural Society.

Colonial-era graves in Pemaquid Cemetery, Maine.

Photo by DrStew82

The living come with grassy tread

To read the gravestones on the hill;

The graveyard draws the living still,

But never anymore the dead.

The verses in it say and say:

“The ones who living come today

To read the stones and go away

Tomorrow dead will come to stay.”

So sure of death the marbles rhyme,

Yet can’t help marking all the time

How no one dead will seem to come.

What is it men are shrinking from?

It would be easy to be clever

And tell the stones: Men hate to die

And have stopped dying now forever.

I think they would believe the lie.

“In a Disused Graveyard, by Robert Frost

An ‘eerily prescient’ show

“Deeper Than You Imagined” (wood and paint), by Sachiko Akiyama, in the group show “Being and Feeling (Alone, Together),’’ on view online at Phillips Exeter (N.H.) Academy’s Lamont Gallery through July 31.

Lamont Gallery Director and Curator Lauren O'Neal said: "It was impossible to know that when this exhibition was finally realized, that it would become eerily prescient, that it would forecast a felt and lived experience, rather than merely a curatorial one."

The artwork on view encompasses a wide variety of media, including painting, sculpture, photography, visual and audio performances.

The gallery says: “While we all hope to soon be physically together with others without fear, ‘Being & Feeling (Alone, Together)’ provides us with cathartic emotional release, instilling hope and appreciation for our humanity even at the worst of times. To check out “Being & Feeling (Alone, Together),’’ visit exeter.edu/lamont-gallery/being-feeling-alone-together.

Looking at light in 'the city that lit the world' by killing whales

Photo kinetic grid by Soo Sunny Park at the Massachusetts Design Art and Technology Institute ( DATMA ) , at the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth Star Store Campus, in downtown New Bedford

This is part of an examination of New Bedford’s legacy as the “city that lit the world” with oil from the whales its whalers killed, in a brutal business.

DATMA says: The Park exhibit is a “site-specific light installation with reflective silver mirrors embedded in welded chain link fencing emitting light and colorful rainbows generated by camera-projector cycles. This project is visible from the street and sidewalks through the building’s floor to ceiling glass gallery windows.’’

David Warsh: 'Charlie Wilson's War' and the 'bounties' on our troops now

Mujahideen fighters in Afghanistan in 1987

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

So rollicking was the back-story of the end of the Soviet Union’s ten-year war in Afghanistan that Hollywood made a movie about it. Charlie Wilson’s War (2003) starred Tom Hanks as a raffish, bibulous Texas congressman in need of an issue in 1980, after a narrow escape from a Rudy Giuliani-led investigation of reported cocaine use. Julia Roberts played the Houston socialite turned talk-show host and world-traveler, who, on behalf of her friend and admirer Pakistani President Zia-ul-Haq, interested Wilson in the cause of mujahidin in Afghanistan.

Wilson had graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1956, and had served in Congress since 1972. He shared with the Islamic fundamentalists a deep faith in God, if not their aversion to distilled spirits.

Encouraged by a CIA maverick (played in the film by Philip Seymour Hoffman), he drummed up support for the Islamic rebellion among his colleagues, eventually supplying the Mujahideen fighters battling the Soviets with shoulder-fired heat-seeking Stinger missiles needed to blow Soviet helicopters out of the sky. After ten bitter years, the Soviets withdrew. The film is based on a 2003 book by George Crile III, a veteran CBS newsman. And, as far as it goes, much of this is true.

Fortunately, another book goes further – much further. Afgantsy: The Russians in Afghanistan 1979-1989 (Oxford, 2011), by Rodric Braithwaite, a diplomat who served as Britain’s Ambassador to the Soviet Union and then to the Russian Federation, 1988-1992. “Afgantsy” is slang for the soldiers who fought in that ill-fated ill-regarded war. Braithwaite begins with an epigraph he found in the diary of Private William Olney, who fought for the Union Army in the Battle of Shiloh in 1862, that reflects what Braithwaite learned as a witness to the war in Afghanistan:

Of course, the private soldier’s field of vision is much more limited than that of his general. On the other hand, it is of vital importance to the latter to gloss over his mistakes, and draw attention only to those things that will add to his reputation. The private soldier has no such feeling. It is only to officers of high rank engaged that a battle can bring glory and renown. To the army of common soldiers, who do the actual fighting, and risk mutilation and death, there is no reward except the consciousness of duty bravely performed.

It was an uprising in Herat by Muslim fighters against the Afghan Communist government that had seized power a year before that triggered a Soviet occupation in 1979. A new agglomeration, the Fortieth Army, was cobbled together from Army and KGB units. American diplomats, aware of the build-up from satellite images, cautioned the Soviets privately but said little more. Years later, Russian generals blamed the Americans for luring them into a quagmire. It was not much of an excuse, says Braithwaite. Even if it were an American trap, “the Russians should have had more sense than to fall into it.”

The Soviets rolled into Kabul in December 1979 and stormed the palace, killing the Afghan Communist president and replacing him with one of their own. President Jimmy Carter, on the ropes from the hostage situation in Teheran and facing an election, asserted that the occupation threatened the Persian Gulf and told his cabinet that the Soviet invasion was “the greatest threat to world peace since World War II.” He secretly authorized the CIA to spend a piddling $500,000 on aid to the rebels and called for a boycott of the forthcoming Olympics in Moscow. British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher backed him up.

Then began the slog. Soviet allies sought to govern the country in a secular manner, sending its daughters to school. Peasants, mostly faithful to Islam, dug in. Ronald Reagan was elected, the American objective changed. CIA Director William Casey believed that the Muslim Mujahideen might not just make the Soviets bleed but could now drive them out of the country altogether. Congressional leaders of both parties supported increasing aid, tenfold in Reagan’s second term. By 1991, the Americans has spent some $9 billion supporting the Mujahideen with almost as much contributed by the Saudis.

And those Stinger missiles? Effective though they were in denying the Soviets easy air superiority, President Mikhail Gorbachev had decided to withdraw a year before the first one was fired, in September 1986. It took more than two years for the last Soviet troops to leave, in February 1989, after a substantial number of deaths caused by those missiles. Making political hay out of the deaths of the last soldiers to perish in retreat from a lost war, as in the “bounties” business is shameful. Recipients of our aid killed more Russian soldiers after the towel was thrown in than theirs have ours.

David Warsh is an economic historian and veteran columnist. He is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran.

Unknown friends

“I take a seat in the third row

and catch the eulogies. It’s sweet

to see old friends, some I don’t know.’’

— From “At My Funeral,’’ by Willis Barnstone, a native of Lewiston, Maine, now living in California

Lewiston mills on the Androscoggin River circa 1910 during the city’s mill town heyday.

In Lewiston, view from the steps of Bates College’s Hathorn Hall looking toward quad and Lindholm House, the admissions office

Chris Powell: Police are forced to deal with cities’ social disintegration

Main Street in Hartford

Responding to complaints about a fireworks party in Hartford on the evening of July 4, three city police officers were pelted with explosives, one device going off just as it struck an officer in the chest. Their injuries were not serious but easily could have been, even fatal.

While the horrifying incident may be dismissed as part of the worsening social disintegration afflicting Connecticut's cities, disintegration that also is reflected lately by the cities' appallingly small response to the U.S. Census work now underway, one can't help but wonder. Was the attack on the Hartford officers inspired or encouraged by the "defund the police" demagoguery raging here and throughout the country?

Of course, the Black Lives Matter movement has a peaceful component, with compelling objectives that most of the country endorses. But even in Connecticut a big part of the movement is not peaceful. It often blocks traffic, even on superhighways, and shouts people down, and its ridiculous demand to reduce or even eliminate policing just where it is most needed harmonizes with the simultaneous demands to release all criminals from prisons, even the murderers, as well as with the general lawlessness, vandalism, and anarchy breaking out in many places.

In the face of the July 4 incident in Hartford and worse incidents around the country, police officers may be feeling like the small-town southwestern sheriff played by Gary Cooper in Stanley Kramer's 1952 Academy Award-winning movie High Noon.

With a vicious criminal gang on its way to take revenge on his town, the sheriff appeals to the townspeople to mobilize to help him but all the able-bodied men refuse. Many urge him to flee. But he holds fast to what he understands as his duty and instead awaits the gang alone.

Their confrontation produces an extended gunfight in which the sheriff takes the gangsters down one by one with some crucial support from his new wife. Then, as the cowardly townspeople gather in the street to marvel at the sheriff's triumph, he tosses his badge into the dust with contempt and rides off in a carriage with his wife.

Like everyone else, police officers may make mistakes, especially in the heat of the moment. As with many other people, some police officers can be cruel, malicious or corrupted by power, and they must be held accountable. That they often have not been is the fault of cowardly elected officials.

Far more often, of course, police officers are brave and heroic even as this is seldom noted — and they are all we've got against the social disintegration that our elected officials have caused, pretend not to see, and do nothing about.

So it was disgraceful that among Connecticut's elected officials only Mayor Luke Bronin and City Council President Maly D. Rosado said something about the July 4 incident in Hartford. Elected officials throughout the state should stop being intimidated by the lawlessness and start demanding better from their constituents.

Indeed, the state's elected officials should find the courage to acknowledge the social disintegration all around them and confront those who claim the right to bypass democracy and disrupt and destroy. For the calls to defund the police and empty the prisons are essentially claims that there is no way of getting the underclass to behave decently, no way of elevating the underclass and stopping the disintegration.

Any jurisdiction that yields to such madness won't deserve police officers any more than the town in High Noon did.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.

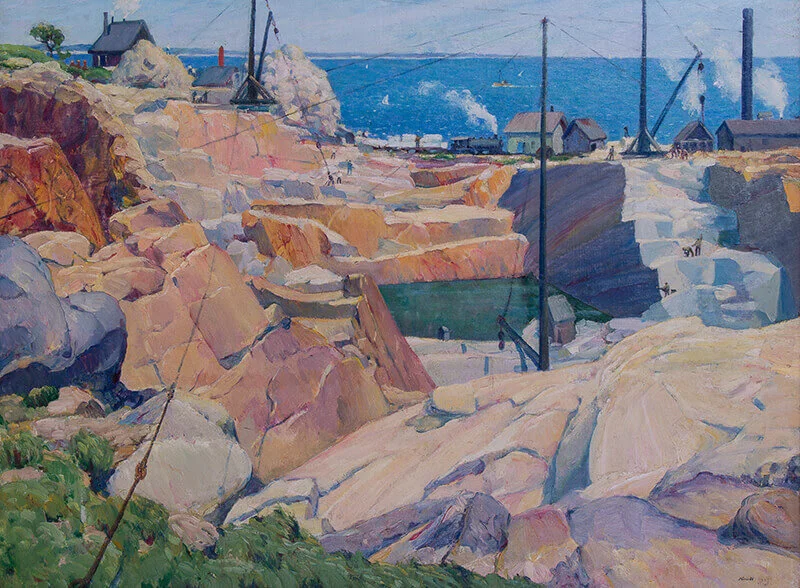

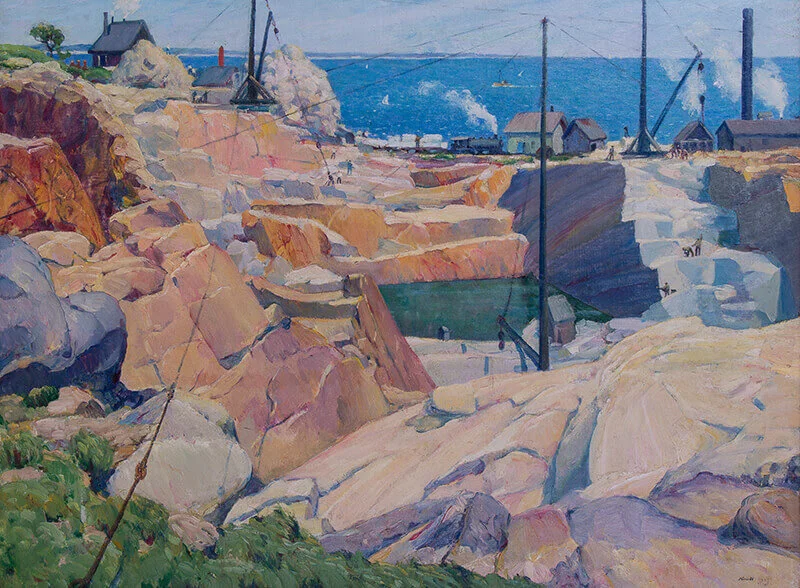

New England’s granite industry

“Babson Farm Quarry, Halibut Point” (Rockport), (1913), (oil on canvas), by Leon Kroll (1884-1974), in the James Collection, Promised Gift of Janet & William Ellery James to the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester.

The museum commented:

“For 100 years, from the early 1830s through 1930, the granite-quarrying industry was a crucial part of Cape Ann’s economy. First undertaken on a small scale with individuals opening up ‘motions’ to harvest stone for their own projects, by the end of the 19th Century, quarrying had grown into a big business, employing hundreds of men and boys (many of them immigrants from around the world), and keeping a fleet of vessels busy transporting stone up and down the Atlantic Seaboard. While granite was taken from the earth in all different sizes and shapes, Cape Ann specialized in the conversion of that granite into paving blocks that were used to finish roads and streets.’’

Editor’s note: New England had granite quarries in all six states. After they were abandoned and water rose in them, many became popular swimming holes. Sadly more than a few people, especially teens, died in them by drowning or hitting their heads on the rocks. And some can have toxic materials in them.

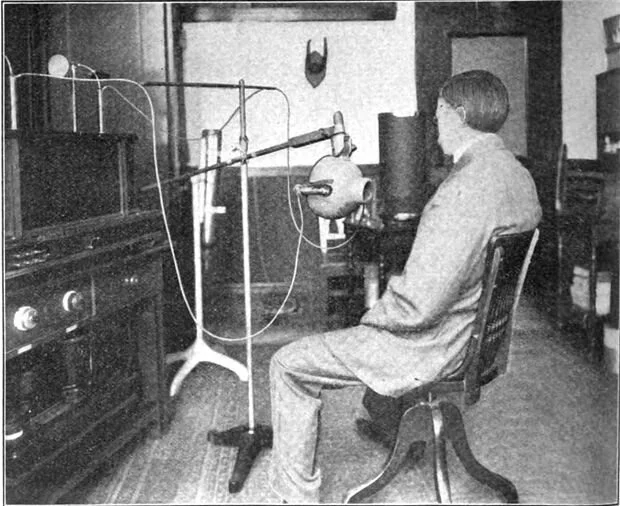

Llewellyn King: Using exaptation, including radiation, to treat COVID-19

X-ray treatment of tuberculosis in 1910

The good news is that if you get COVID-19, you stand a better chance of getting better sooner, without having a long, if any, stay in the ICU, and you may not have to suffer on a ventilator.

The bad news is there may be no silver bullet of a vaccine by the end of the year, and if one is approved, there may be a free-for-all among vaccine developers, countries, and special interests.

For the improvement in treatment outlook, thank a process called exaptation. The term has been appropriated from evolutionary biology and means essentially work with what you have, adapt and deploy. The most quoted example is how birds developed wings for warmth and found they could be used for flying.

One of the great exponents of exaptation, Omar Hatamleh, chief innovation officer, engineering, at NASA, says, “There is an abundance of intellectual property that can be repurposed or used in areas and functions outside of their original intended application.”

There are hundreds of thousands, maybe millions, of medicines – generally referred to as “compounds” in the pharmaceutical world – that have been developed for specific purposes but which may be useful in some other disease, “off label” in the pharmacologists’ vernacular. An example of this off-label use is the steroid Dexamethasone. It has been found to reduce death among critically ill COVID-19 patients.

It is a good idea to look outside the box, as we are constantly advised. But it is also a good idea to look inside the box as well.

Inside every hospital, for example, is a radiation department. Radiation is a medical tool universally used in cancer treatments.

Now comes word that radiation can save lives and cut hospital stays for COVID-19 patients. James Conca, a Tri-Cities, Wash.- based nuclear scientist, explains to me, “This treatment is critical because severe cases cause cytokine release syndrome, also known as a cytokine storm, causing acute respiratory arrest syndrome, which is what kills.”

Dr. Mohammad Khan, associate professor of radiation oncology at Emory University School of Medicine, in Atlanta, gave patients at the university’s Winship Cancer Institute a single, very low dose of radiation (about one hundredth of the dose given cancer patients) and they began to show almost immediate improvement. The radiation reduced the inflammation -- and in COVID-19, as in many other diseases, it is inflammation that kills.

The use of radiation in this way opens the door to the treatment of many diseases where inflammation is the killer.

The Emory experience fits with a burgeoning field of study where sophisticated physical and engineering techniques intersect with medicine.

Dr. James Welsh of Loyola University Medical Center, in Chicago, and a consortium of doctors and hospitals are hoping to launch nationwide clinical trials on the use of radiation in combating killer inflammation.

The sad thing, Conca says, is that the benefits of radiation in treating pulmonary disease, especially viral pneumonia, were known 70 years ago. In treating the pneumonia, he said, success rates were 80 percent, but the rise of antibiotics and antiviral drugs, combined with public concern about radiation, led to its being confined to the treatment of cancer.

Generally nuclear medicine tends to mean cancer treatment, but nuclear scientists have chafed at this.

While the outlook for therapies -- for things will save your life in hospital -- is bright, the outlook for a vaccine, so hoped for, is confused. Assuming that a vaccine is perfected, that it works on most people and across a range of mutations, the stage is set for chaotic distribution.

One man and his company, Adar Poonawalla, CEO of Serum Institute of India, may hold the key to who gets the vaccine first. He has signed pacts with four vaccine hopefuls, including the one from Oxford University, considered by many to be the frontrunner.

Serum Institute is partnering with the British-Swedish drugmaker AstraZeneca to manufacture and supply 1 billion doses of the Oxford vaccine in India and less-developed countries. AstraZeneca says it is working on equitable distribution. British Prime Minister Boris Johnson has said Britain should have first dibs on British-developed vaccines.

The World Health Organization is the only international organization that might be able to orchestrate distribution, and the United States is withdrawing from that body.

Science may be forging ahead – exaptation at work -- but human folly is as virulent a strain as ever.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

See whchronicle.com

Savoring daily variations

Panoramic view of Willoughby Notch and Mount Pisgah, in Vermont’s “Northeast Kingdom.’’

— Photo by Patmac13

“Country people do not behave as if they think life is short; they live on the principle that it is long, and savor variations of the kind best appreciated if most days are the same.’’

“True solitude is a din of birdsong, seething leaves, whirling colors, or a clamor of tracks in the snow.’’

— Edward Hoagland, essayist, nature and travel writer and novelist. He lives in Barton, Vt., in the “Northeast Kingdom’’ in the summer and relatively mild Martha’s Vineyard in the winter.

‘Healing power of nature’

“June, 2020”(oil on linen), by David Curtis, in the Guild of Boston Artists’ show “Nature’s Refrain,’’ through July 31

The guild says that the show “is a reflection and celebration of the restorative power of nature,’’ especially as we go through this pandemic.

“Throughout history, artists have been inspired by nature during times of stress, just as the members of The Guild of Boston Artists have during this pandemic. Although the country is slowly reopening, many are still self-isolating and staying away from parks and other outdoor places. ‘Nature's Refrain’ offers a way for viewers to get the healing power of nature in their own homes. The wide variety of artworks, from depictions of neat potted plants to wild landscapes, emphasize resiliency and regrowth. By now, these ideas are familiar to us as we persevere through this pandemic. ‘Nature's Refrain’ reflects them back to us and offers comfort and calm through the beauty of the natural world. ‘‘

See guildofbostonartists.org

and:

https://www.davidpcurtis.com/bio

McDonald’s hiring 7,800 restaurant workers in New England this summer

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

“As New England businesses continues to reopen, McDonald’s restaurants are expecting to hire approximately 7,800 restaurant employees in New England this summer.

“The hiring news comes as McDonald’s restaurants begin to welcome customers back into dining rooms with extra precautions in place, including nearly 50 new safety procedures to protect crew and customers. These include wellness and temperature checks, social distancing floor stickers, protective barriers at order points, masks and gloves for employees with the addition of new procedures, and training for the opening of dining rooms.’’

New England Diary on radio

— By Burgundavia (PNG); Ysangkok (SVG)

On most Fridays at 9:30 a.m., New England Diary joins Bruce Newbury in his Talk of the Town show on WADK (1540 AM) and online at wadk.com