Very fragile Burrillvilleans

The town offices of exurban/suburban Burrillville, R.I.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Gun-toting Burrillville, R.I., has become a sort of mini-Red State, in which science and public health take a back seat to libertarian obsessions. I’m referring to its Town Council’s 5-2 vote on June 24 to declare Burrillville a “First Amendment Sanctuary Town.”

This was part of the council’s denunciation of Gov. Gina Raimondo’s executive orders regarding social distancing, crowd size, face masks and other coronavirus-control measures as “unconstitutional’’ and, presumably, ignorable under the First Amendment. The council asserts that the measures have caused “substantial harm to the emotional, spiritual and financial well-being” of residents. Give me a break! Surely Burrillvilleans aren’t that sensitive and fragile!?

It’s nice to see, any event, Burrillville expressing interest in the First Amendment rather than just its version of the Second Amendment (making sure to leave out that inconvenient bit about “a well-regulated militia’’).

Of course living in a community where you’re more likely to get infected than in some nearby places because the usual public-health rules in a pandemic aren’t followed can also do “substantial harm’’ to your “well-being.’’ And being sick ain’t good for your freedom either.

Oh, well ….

In any case, Governor Raimondo and her team have done a good job in managing the pandemic through relentlessly promoting behavioral guidelines and tests, especially considering the state’s location between the two hot spots of metro New York and metro Boston and that it’s the second most densely populated state (after New Jersey). As of this typing, the Ocean State had reported a little over 900 deaths in a population of a bit over 1 million while Massachusetts has reported over 8,000 deaths in a population of about 6.9 million.

Leaders like Ms. Raimondo must battle the politically driven, or just crazy, misinformation about the pandemic on Facebook and other social media and the strong anti-science element in America now.

Of course, people generally don’t want to be told what to do…..

New Hampshire's lucrative fireworks exports menace neighbors

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

As it turns out, many perhaps most, of those fireworks that have ruined life recently for many people in Providence, Boston and other New England cities came from New Hampshire, that old “Live Free or Die” parasite/paradise (where I lived for four years). There, out-of-state noisemakers stock up and take the explosives back to Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut, where they ignite them all over the place, with the worst impact in cities. While the fireworks are illegal in densely populated southern New England, they’re legal in the Granite State.

New Hampshire has long made money off out-of-staters coming to buy cheap (because of the state’s very tax-averse policies) booze and cigarettes. The state also has loose gun laws. Fireworks are in this tradition.

That’s its right. But it could be a tad more humane toward people in adjacent states by making it clear to buyers at New Hampshire fireworks stores that the explosives they’re buying there are illegal in southern New England.

Because of our federal system, states that may want to control the use of dangerous products can be hard-pressed to do so because residents may find it easy to drive to a nearby state and get the stuff. Still, in compact and generally collaborative New England, it would be nice if New Hampshire, much of which is exurban and rural, would consider the challenges of heavily urbanized Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut as they seek to limit the use of fireworks, especially in cities. Granite Staters might remember that much of the state’s affluence stems from its proximity to that great wealth creator Greater Boston and show a little gratitude. (This reminds me of how Red States are heavily subsidized by Blue States, whose taxes fund much of the federal programs in the former.)

Ah, the federal system, one of whose flaws is painfully visible in the COVID-19 pandemic. Look at how the Red States, at the urging of the Oval Office Mobster, too quickly opened up, leading to an explosion of cases, which in turn hurts the states that had been much tougher and more responsible about imposing early controls. But yes, the federal system’s benign side includes that states can experiment with new programs and ways of governance, some of which may become national models, acting as Justice Louis Brandeis called “laboratories of democracy’’.

To read more about New Hampshire’s quirks, please hit this link.

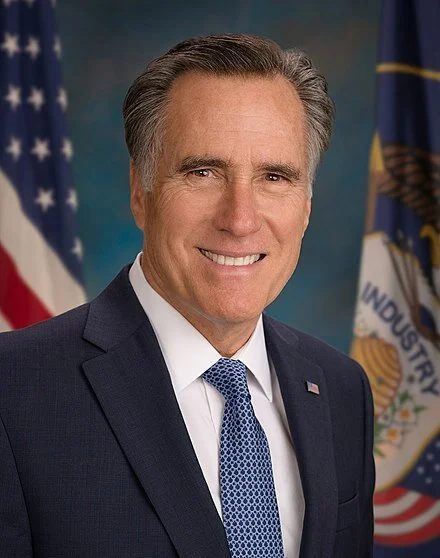

Romney on Mass. gun laws

Mitt Romney

“We do have tough gun laws in Massachusetts. I support them. I won't chip away at them. I believe they help protect us and provide for our safety.’’

Mitt Romney, Republican governor of Massachusetts, 2003-07, and now U.S. senator from Utah. When a Bay Stater, he lived in Belmont, a very affluent western suburb of Boston.

The grand Romanesque Belmont Town Hall.

'Regally abide'

Some flowers are withered and some joys have died;

The garden reeks with an East Indian scent

From beds where gillyflowers stand weak and spent;

The white heat pales the skies from side to side;

But in still lakes and rivers, cool, content,

Like starry blooms on a new firmament,

White lilies float and regally abide.

In vain the cruel skies their hot rays shed;

The lily does not feel their brazen glare.

In vain the pallid clouds refuse to share

Their dews, the lily feels no thirst, no dread.

Unharmed she lifts her queenly face and head;

She drinks of living waters and keeps fair.

“July,’’ Helen Hunt Jackson (1830-85) grew up in Amherst, Mass.

Safe from COVID until NASA arrives

Triptych, from left to right: “Canals of Mars, Martian Sky, Martian Water,’’ (all acrylic on wood), by Boston and Beverly painter Rose Olson, in her show “Rain and Sunshine,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, through July 26.

Her artist’s statement:

“Color has sharpening aspect affecting our senses and intellect simultaneously. These paintings reflect my passion for color and its interaction with the beauty of natural elements.

“Wood-grain patterns are exciting and varied since each is specific to what once was a living tree. Their patterns are as unique as our fingerprints, as important as the colors I use. Layers of color are applied one at a time enhancing each wood grain pattern as the painting builds in luminosity. Conscious of the interplay, colors often change as the viewer moves or the light shifts. Hard edges and added color bands enhance the color and spatial effects revealing another way of seeing the world.’’

See:

http://www.kingstongallery.com/

and:

roseolson.com

'Grit in the bones'

Stonington (Conn.) Harbor Light was built in 1840 and is a well-preserved example of a mid-19th Century stone lighthouse. The lighthouse was taken out of service in 1889 and is now a local history museum. Stonington once was an important fishing and whaling port but is now mostly known a summer place for affluent people, especially from New York City. Many writers (such as the late poet James Merrill) and painters have also had homes there.

“The shades of New England are here on my skin. Brine in the blood, grit in the bones, and sea air in the lungs.’’

— L.M. Browning, in Fleeting Moments of Fierce Clarity: Journal of a New England Poet. She grew up in Stonington, Conn.

A WPA for transportation?

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Traffic is starting to back up again in southern New England roads as the economy opens up in fits and starts. I found it bumper to bumper for a while the other week on Route 128 west of Boston. The roads are crumbling and the environmental effects of our extreme car-dependence are obvious. We need to expand mass transit. Yes, fear of COVID-19 has taken a toll on transit ridership but the frustrations and dangers of car travel (far more dangerous than travel on trains and buses) will soon enough send many people back to the likes of the MBTA.

Meanwhile, gasoline prices are very low and will likely continue so for some time to come. So when this depression ends, gasoline taxes should be raised to make the long-delayed improvements in transportation that will be good for the environment and for the economy. Maybe some people left permanently jobless by the pandemic depression can be employed in (Great Depression-era) WPA-style work to help fix the region’s worst transportation problems.

A WPA road project, in the Great Depression

Robin DeRosa: An urgent call for more equity in higher education

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

PLYMOUTH, N.H.

About a year ago, I attended a meeting at the New England Board of Higher Education (NEBHE) focused on reducing the cost of learning materials for college students in our region. I have been pleased since then to work with colleagues across the New England states on NEBHE’s Open Education Advisory Committee that is looking into how best to support institutions and faculty as they replace high-cost commercial textbooks with free, openly licensed resources that can make college more accessible for learners and improve student engagement and success. This work is well underway, but the world seems vastly different than it did last year, and I have been thinking about how our current reality impacts and benefits from our ongoing work in open education.

When COVID-19 shut down the college campus where I work, faculty and staff knew that many of our students would be challenged by the quick transition to emergency remote learning. Learning online can feel alien to some students, and many of our faculty had only days to transition their courses into the new modality. What may have surprised many faculty, though, was the impact that COVID-19 had on our students’ basic needs and how that impact so thoroughly halted their ability to continue their learning.

While pre-COVID surveys tell us, for example, that almost half of American college students experienced food insecurity in the month prior to being surveyed, COVID thrust many of these students from chronic precarity to immediate emergency. As work-study jobs closed, and local businesses that employed students shut down, meager incomes shriveled and affording food, housing, car payments, internet and phone service and healthcare became impossible for many.

Faculty might have worried about how students would fare with complicated content delivered over Zoom, but students were worried that they would starve, become homeless or have to witness their families fall into even more dire poverty. Students became frontline workers, increasing hours at grocery stores and gas stations even though they couldn’t afford that time away from their studies, the personal protective equipment they needed to stay safe, nor the health-care costs they’d face if they got sick. As I worked with more and more students who were trying to survive through COVID, I wondered if “open education” was really enough of an answer to this scale of crisis.

On its surface, the resurgence of Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests in the wake of the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor by police officers may seem to have little to do with COVID-19. But BLM and related movements to “defund the police” are deeply entwined with critiques that highlight how systemic racism pitches the playing field against Black, Indigenous and people of color (BIPOC).

BLM doesn’t just call out specific cases of police brutality; it asks us to look at how policing, surveillance and the justice system ironically and brutally create unfair and unsafe living conditions for some Americans. “Defunding the police” isn’t just about taking military weapons and excess funding away from departments poisoned by bad apples; it’s about reinvesting in under-resourced neighborhoods and redistributing funding for social supports in underserved areas to create healthier communities from the inside out. It’s easy to see the effects that decades of redlining and a centuries-long history of American racism have had on our students. There are thousands of data points we could examine, but stick with with food insecurity for a moment (with more stats from a recent Hope Center report): the overall rate of food insecurity among students identifying as African-American or Black is 58%, which is 19 percentage points higher than the overall rate for students identifying as white or Caucasian. When COVID ravaged our precarious students, Black students were hit especially hard. Another demographic that deals most frequently with food insecurity is students who have formerly been convicted of a crime. Think about that today, more than three months after the murder of Breonna Taylor; only her boyfriend,who was defending his home against the surprise police invasion, has been arrested in that incident.

For some students (and even contingent faculty and staff in our universities) COVID has augmented inequities that were already baked into their lives. Our continuing institutional failures to ameliorate or address these inequities can no longer be tolerated, both because the vulnerable in our colleges are at a breaking point from a global pandemic and because we have been called out by a national social justice movement that is demanding that we make real change at last. Is open education a way to answer this call?

I want to cautiously explain why I think the answer is yes. The high cost of commercial textbooks has a much larger impact on student success than most people imagine, and the benefits of switching to OER are well-documented, especially for poor students and students of color. When we imagine the reasons for these improvements in “student success,” we generally chalk it up to cost savings; after all, students can’t learn from a book they can’t afford. I don’t mean to minimize the absolutely crucial impact of cost savings on learning, but what might be even more helpful about OER is the way it asks us to rethink the kind of architecture we want to shape our education system.

Many of us are familiar with the idea of the “College Earnings Premium,” which calculates that people with college degrees on average earn much more (recently estimated at 114% more) than those who don’t have degrees. Philip Trostel, a University of Maine economist who tracks the value of public higher education, takes the story of the earnings premium much further, explaining that many market benefits extend past individuals who go to college into the community at large (for example, if more people in a region go to college, tax revenues in the region also increase and the need for public assistance goes down). Even beyond this, public benefits extend past individuals and past economics, positively affecting health, disability rates, crime rates, longevity, marital stability, happiness and more. These benefits can be passed to children (whether or not they go to college) and in some cases even to whole regions. Similarly, as OER shows such benefit to individual students, we may overlook the more public benefits of making broader policy and practical changes that would expand OER (or college access) to all students.

I don’t just want to eliminate the profit motive in the “production” and “distribution” of learning and learning materials. I also want to embed learning in a structure that is fully aware of the social, public and communal value of higher education. When a global pandemic hits, I want colleges to open their gyms as overflow hospitals, work with local food pantries to ensure access to meals for everyone in the area and develop and openly share research to aid in finding treatments and cures. This is open education. When activists raise the alarm on systemic racism in policing, I want colleges to reject plagiarism software, disarm their campus police departments, increase the number of faculty of color in their ranks, and commit resources to antiracist research and initiatives. This is open education. When we work to shift from commercial textbooks to OER, we are not just saving students money; we are centering equity in education, and we shouldn’t undersell our vision. In fact, we shouldn’t sell this vision at all.

College is not only a way to make individual students richer. OER is not only a way to save individual students money. We have a chance to rebuild a post-COVID university that sees basic needs as integral to any learner’s academic success and actively develops ways to integrate basic needs with the missions of our institutions. We have a chance to redistribute our resources away from surveillant educational technology and corporations that mine student data for profit and think more about the value of education in terms of how healthy and safe and sustainable it can make the publics outside the walls of the academy. And how the academy can be more symbiotic with those publics.

When I work on OER initiatives, especially in larger collaborations across systems and states like our NEBHE team does, I am working on a vision for the future of higher education that is deeply responsive to the inequities that are threatening the heart of our country and threatening the lives of so many Americans who are fighting for survival at the very moment I am writing this. Our colleges and universities need to step up, and open education is a framework—perhaps one of many—that can help us center equity as we go forward at a pivotal moment in time.

Robin DeRosa is the director of the Open Learning & Teaching Collaborative at Plymouth State University in New Hampshire, at the approach to the White Mountains. Check out the Museum of the White Mountains there. Hit this link:

https://www.plymouth.edu/mwm/

and:

http://digitalcollections.plymouth.edu/digital/collection/p15828coll7

Ellen Reed House, home of the English Department, at Plymouth State University

Walmart and ridgeline wind turbines in Plymouth

Photo by Atlawrence881

Victoria Knight: Inadequate data on efficacy of face masks

“We simply don’t have data to say this,” Andrew Lover, an assistant professor of epidemiology at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

A popular social media post that’s been circulating on Instagram and Facebook since April depicts the degree to which mask-wearing interferes with the transmission of the novel coronavirus. It gives its highest “contagion probability” — a very precise 70% — to a person who has COVID-19 but interacts with others without wearing a mask. The lowest probability, 1.5%, is when masks are worn by all.

The exact percentages assigned to each scenario had no attribution or mention of a source. So we wanted to know if there is any science backing up the message and the numbers — especially as mayors, governors and members of Congress increasingly point to mask-wearing as a means to address the surges in coronavirus cases across the country.

Doubts About The Percentages

As with so many things on social media, it’s not clear who made this graphic or where they got their information. Since we couldn’t start with the source, we reached out to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to ask if the agency could point to research that would support the graphic’s “contagion probability” percentages.

“We have not seen or compiled data that looks at probabilities like the ones represented in the visual you sent,” Jason McDonald, a member of CDC’s media team, wrote in an email. “Data are limited on the effectiveness of cloth face coverings in this respect and come primarily from laboratory studies.”

McDonald added that studies are needed to measure how much face coverings reduce transmission of COVID-19, especially from those who have the disease but are asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic.

Other public health experts we consulted agreed: They were not aware of any science that confirmed the numbers in the image.

“The data presented is bonkers and does not reflect actual human transmissions that occurred in real life with real people,” Peter Chin-Hong, a professor of medicine at the University of California-San Francisco, wrote in an email. It also does not reflect anything simulated in a lab, he added.

Andrew Lover, an assistant professor of epidemiology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, agreed. He had seen a similar graphic on Facebook before we interviewed him and done some fact-checking on his own.

“We simply don’t have data to say this,” he wrote in an email. “It would require transmission models in animals or very detailed movement tracking with documented mask use (in large populations).”

Because COVID-19 is a relatively new disease, there have been only limited observational studies on mask use, said Lover. The studies were conducted in China and Taiwan, he added, and mostly looked at self-reported mask use.

Research regarding other viral diseases, though, indicates masks are effective at reducing the number of viral particles a sick person releases. Inhaling viral particles is often how respiratory diseases are spread.

SOURCES:

ACS Nano, “Aerosol Filtration Efficiency of Common Fabrics Used in Respiratory Cloth Masks,” May 26, 2020

Associated Press, “Graphic Touts Unconfirmed Details About Masks and Coronavirus,” April 28, 2020

BMJ Global Health, “Reduction of Secondary Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in Households by Face Mask Use, Disinfection and Social Distancing: A Cohort Study in Beijing, China,” May 2020

Email interview with Andrew Noymer, associate professor of population health and disease prevention, University of California-Irvine, June 29, 2020

Email interview with Jeffrey Shaman, professor of environmental health sciences and infectious diseases, Columbia University, June 29, 2020

Email interview with Linsey Marr, Charles P. Lunsford professor of civil and environmental engineering, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, June 29, 2020

Email interview with Peter Chin-Hong, professor of medicine, and George Rutherford, professor of epidemiology and biostatistics, University of California-San Francisco, June 29, 2020

Email interview with Werner Bischoff, medical director of infection prevention and health system epidemiology, Wake Forest Baptist Health, June 30, 2020

Email statement from Jason McDonald, member of the media team, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, June 29, 2020

The Lancet, “Physical Distancing, Face Masks, and Eye Protection to Prevent Person-to-Person Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” June 1, 2020

Nature Medicine, “Respiratory Virus Shedding in Exhaled Breath and Efficacy of Face Masks,” April 3, 2020

Phone and email interview with Andrew Lover, assistant professor of epidemiology, University of Massachusetts Amherst, June 29, 2020

Reuters, “Partly False Claim: Wear a Face Mask; COVID-19 Risk Reduced by Up to 98.5%,” April 23, 2020

The Washington Post, “Spate of New Research Supports Wearing Masks to Control Coronavirus Spread,” June 13, 2020

One recent study found that people who had different coronaviruses (not COVID-19) and wore a surgical mask breathed fewer viral particles into their environment, meaning there was less risk of transmitting the disease. And a recent meta-analysis study funded by the World Health Organization found that, for the general public, the risk of infection is reduced if face masks are worn, even if the masks are disposable surgical masks or cotton masks.

The Sentiment Is On Target

Though the experts said it’s clear the percentages presented in this social media image don’t hold up to scrutiny, they agreed that the general idea is right.

“We get the most protection if both parties wear masks,” Linsey Marr, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Virginia Tech who studies viral air droplet transmission, wrote in an email. She was speaking about transmission of COVID-19 as well as other respiratory illnesses.

Chin-Hong went even further. “Bottom line,” he wrote in his email, “everyone should wear a mask and stop debating who might have [the virus] and who doesn’t.”

Marr also explained that cloth masks are better at outward protection — blocking droplets released by the wearer — than inward protection — blocking the wearer from breathing in others’ exhaled droplets.

“The main reason that the masks do better in the outward direction is that the droplets/aerosols released from the wearer’s nose and mouth haven’t had a chance to undergo evaporation and shrinkage before they hit the mask,” wrote Marr. “It’s easier for the fabric to block the droplets/aerosols when they’re larger rather than after they have had a chance to shrink while they’re traveling through the air.”

So, the image is also right when it implies there is less risk of transmission of the disease if a COVID-positive person wears a mask.

“In terms of public health messaging, it’s giving the right message. It just might be overly exact in terms of the relative risk,” said Lover. “As a rule of thumb, the more people wearing masks, the better it is for population health.”

Public health experts urge widespread use of masks because those with COVID-19 can often be asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic — meaning they may be unaware they have the disease, but could still spread it. Wearing a mask could interfere with that spread.

Our Ruling

A viral social media image claims to show “contagion probabilities” in different scenarios depending on whether masks are worn.

Experts agreed the image does convey an idea that is right: Wearing a mask is likely to interfere with the spread of COVID-19.

But, although this message has a hint of accuracy, the image leaves out important details and context, namely the source for the contagion probabilities it seeks to illustrate. Experts said evidence for the specific probabilities doesn’t exist.

We rate it Mostly False.

Victoria Knight is a journalist at Kaiser Health News.

With hidden faces

"Abstract Reflections," by Marcia Wise, at Fountain Street Gallery, Boston, through July 19.

See:

https://www.marciarwise.com/

and:

https://www.fsfaboston.com/

Don Pesci: Taking down Columbus and a mau-mauing in New Haven

Bronze statue of Christopher Columbus, formerly situated at Wooster Square, in New Haven. The statue was removed by the city Parks Commission on June 24, 2020.

A video published by the New Haven Independent showing New Haven Mayor Justin Elicker being mau-maued by Los Fidel, not his birth name, the day after a Columbus statue had been booted from Wooster Square Park may not be a vote-getter for Elicker during his next campaign.

Two days after the removal of the statue by the Park Commission, not the city’s elected Board of Alderman, tempers were still sparking.

“You should have been here,” Fidel told Elicker.

“Everyone makes mistakes, and I make mistakes,” Elicker responded. In retrospect, Elicker confessed, “he should have been in Wooster Square rather than in his office at City Hall on Wednesday.”

On the day of removal, Elicker had been at a safe distance from the park in his office attending to business. Two days later, he ventured out and met with about 30 protesters who had cheered as the offending statue had been carted off.

“Sitting on the grass in a circle with the group,” The New Haven Independent reported, “Elicker spent most of the first hour listening to Fidel tell his story, interspersed with critiques of the mayor. (Watch the full conversation in the video above.)”

The video captures Fidel hurling imprecations at the mayor. “F**k you!” critiqued Fidel at one point.

His manners exquisitely intact, Elicker responded, “That’s not respectful.”

Fidel’s story was poignant:

“I’m looking at the f**king white devil," Fidel said at another point. He then apologized for his manner, and wiped away tears as he recounted getting punched in the back of the head and having slurs shouted at him Wednesday.

Fidel spoke of the many times he has been arrested over the years, for charges including felony possession of a deadly weapon and driving under the influence. He said his first arrest came at 13, and that the deadly weapon charge had to do with fishing equipment and was exaggerated by police.

He expressed how he has felt traumatized by law enforcement growing up in Bridgeport and living in New Haven for over 15 years.

"I’m a felon. I’ve been arrested for things I didn’t do my whole life," Fidel said. He said law enforcement has falsely targeted him. "I stabbed somebody in self-defense." He said he was charged with operating a "drug factory," when in fact, he said, he had less than an ounce of marijuana at his place. (According to court records, he has been found guilty of second-degree assault, probation violation, larceny, and reckless endangerment, among other offenses.)

To be sure, life in the city under the glare of the hypercritical police is no walk in the park. But Elicker’s problem, purely political, is a bit different than Fidel’s. Will the whole affair surrounding the removal of a mute statue help or hurt Elicker politically? It may seem obscene to people who are not professional politicians, but politicians, as a general rule, have an eye cocked on political loss or gain when they engage in politics. And politicians are always on the job, so to speak, always politicking, whether they are hugging babies or, in the midst of a Coronavirus outbreak, not hugging babies.

Other protesters joined in the conversation after Fidel had recovered his manners. “Disband police officers that have lost their legitimacy because they are working as an occupying force and stealing wealth from African-American communities,” one recommended.

Elicker responded that he was “prioritizing moving along appointments and seating the police Civilian Review Board… ‘I think there are opportunities to civilianize the police force,’ Elicker said. He said he sees opportunities to have police officers show up to fewer calls, which can be diverted to other responders,” the cri de coeur of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement.

So it goes in New Haven, and much of this is “deja vu all over again,” in Yogi Bera’s memorable phrase, for people familiar withThomas Wolfe’s still readable essays published in a book titled Radical Chic & Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers.

Here is Wolfe carefully probing the difference between a confrontation and a demonstration in Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers:

A demonstration, like the civil-rights march on Washington in 1963, could frighten the white leadership, but it was a general fear, an external fear, like being afraid of a hurricane. But in a confrontation, in mau-mauing, the idea was to frighten white men personally, face to face. The idea was to separate the man from all the power and props of his office. Either he had enough heart to deal with the situation or he didn't. It was like to saying, "You--yes, you right there on the platform--we're not talking about the government, we're not talking about the Office of Economic Opportunity--we're talking about you, you up there with your hands shaking in your pile of papers ..."

Intimidation of this kind may not be “respectful” – but it works well enough in New Haven.

D0n Pesci is a columnist based in Vernon, Conn.

'Appearance/disappearance'

“Beach Path 1’’ (oil paint monotype), by Carolyn Letvin, at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, online gallery.

She writes:

“The light in this image creates the passageway to a distant horizon. The positive and negative space are in communion, and give definition to each other. This image reveals the nature of duality in the forms of appearance/disappearance, past/future, heaven/earth.’’

See:

www.carolynletvin.com

galateafinert.com

Better than Nature

“They have been with us a long time.

They will outlast the elms…

The Nature of our construction is in every way

A better fit than the Nature it displaces.’’

— From “Telephone Poles,’’ by John Updike (1932-2009), for decades America’s leading man of letters. He spent most of his adult life on Massachusetts’s North Shore.

h

Waiting for the ‘salt wash’

Bass Harbor (Maine) Lighthouse

— Photo by Chandra Hari

“Where shell and weed

Wait upon the salt wash of the sea,

And the clear nights of stars

Swing their lights westward

To set behind the land…’’

From “Night,’’ by Louise Bogan (1897-1970), a native of Livermore Falls, Maine.

Downtown Livermore Falls, Maine, in 1909.

An edited version of a paragraph from Wikipedia:

“In the early 19th Century, the town’s region was predominantly farmland, with apple orchards and dairies supplying markets at Boston and Portland, and it was noted for fine cattle. As the century progressed, gristmills, sawmills, logging and lumber became important industries, operated by water power from falls that drop 14 feet. With the arrival of the Androscoggin Railroad, in 1852, Livermore Falls developed as a small mill town. Shoe factories and paper mills were established. . In 1897, the Third Bridge was built across the Androscoggin River. It measured 800 feet in length, at that time the longest single-span bridge in New England.’’

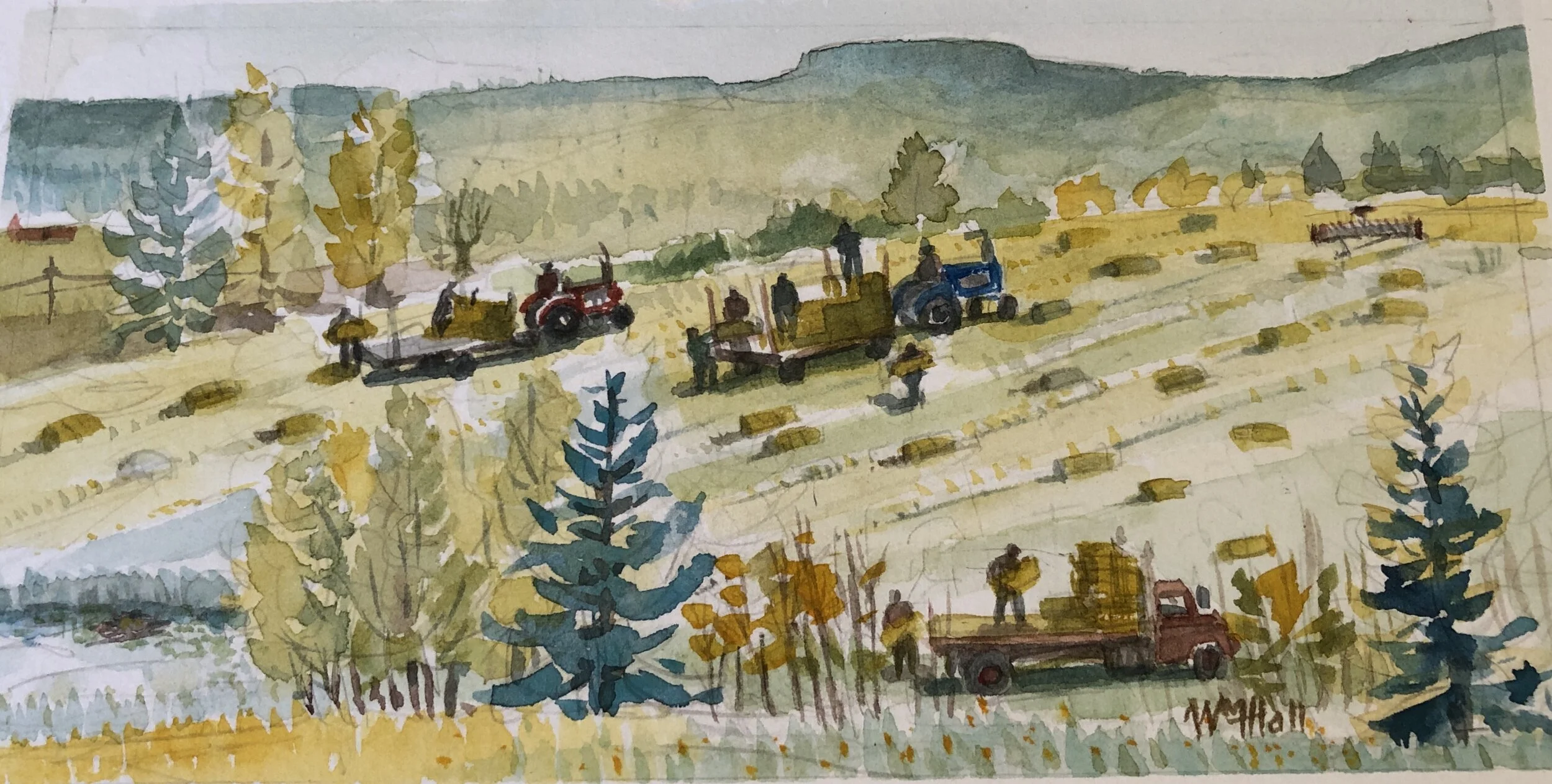

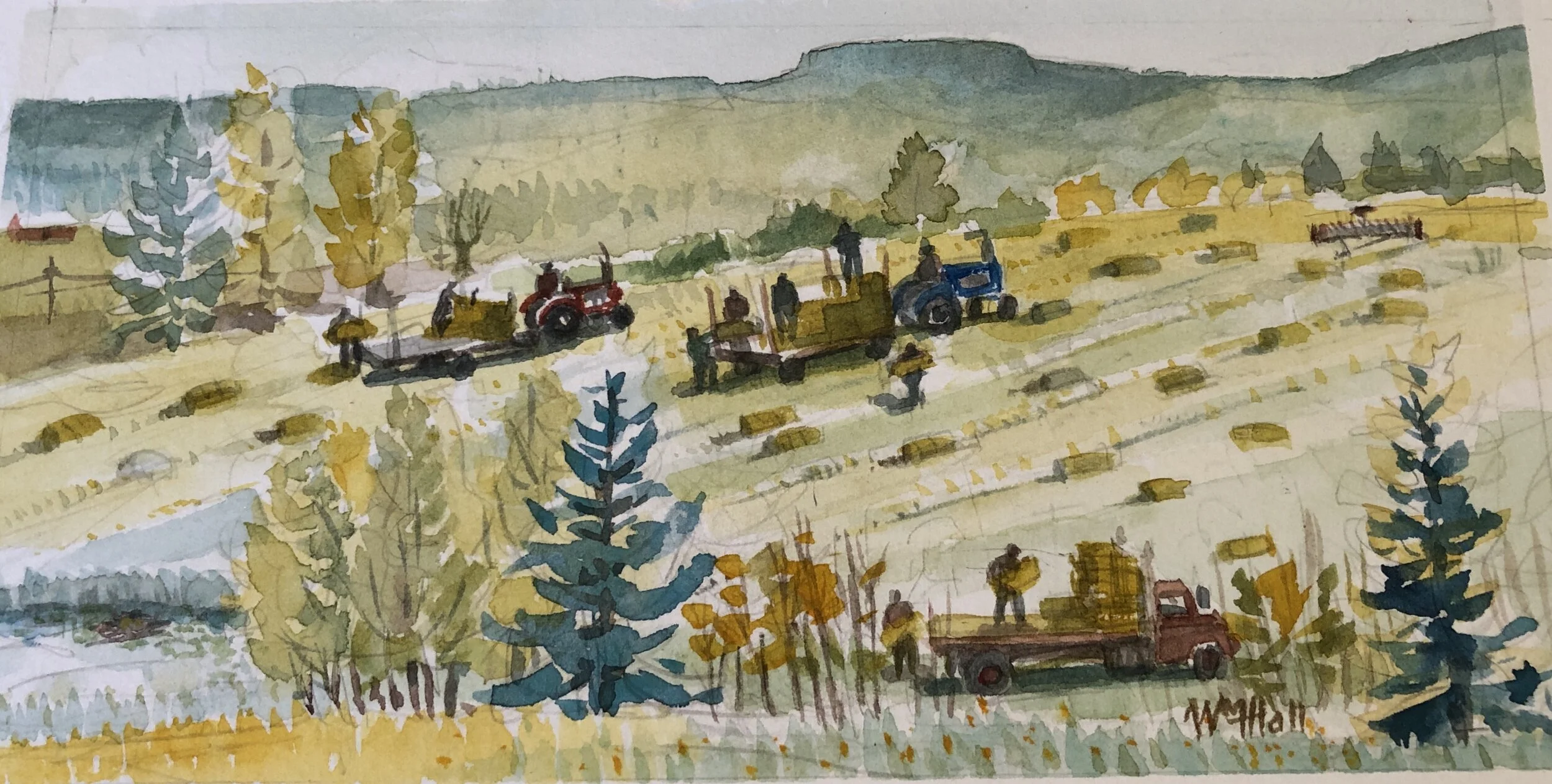

Bill Hall: The big gamble of 'early haying' in Vermont

“Harvesting the Hay Crop on Deadline’’

— Watercolor by Bill Hall

In late May it could get hot in Vermont’s Connecticut River “Upper Valley’’. You shifted slowly from here to there, but you had to move. If you didn’t you’d swear you would suffocate. You weren’t avoiding the oppressive heat as much as you were looking for some air to breath. Shade didn’t help much; it only served to dull the searing brightness. The heat was just there. If you were a farmer you had to get used to it, and get things done anyway. One of those things might have been to get in the early (season’s first) crop of hay: “early hay”.

In that sudden sweltering heat, you had to decide:

“Hay or no hay”?

Once you decided to hay, you had to do it fast. After the brutality of winter and the torrents of “mud season,” after the financial reality of dairy farming sank in once again, you had to get moving. You might put off the question of buying new equipment by fixing the old. Or should you pay down your loan?

Farmers in the Connecticut River Valley had to weigh the costs and rewards of throwing the dice once again. Would they risk an early haying or would they fold and walk away? That was the big gamble.

Early hay or “spring mow” sounds simple enough to a non-farmer. The common question asked, “Is it possible?” The correct answer is, “No, in most cases,” due to weather, which is always uncertain in northern New England. “Then, is it necessary,” you might ask?

In some professions, such as insurance, determining possibilities is a scientific matter, but in farming it’s just called “gambling”. My street-smart father called it “ The Farmers’ Hat-Trick”. He explained it to my brother and me as he shifted three dried butternut half-shells around on the kitchen table in short quick movements, one shell concealing a dried pea seed. You know this game. Which shell hides the pea? This was to demonstrate how, by a game he called “slight-of-hand,” farmers plotted to sneak a full barn of early hay right out from under the nose of a vengeful God.

My brother and I did not realize we were also getting a lesson about my father’s religious beliefs, seasoned by his ironic sense of humor. He was a traveling farm-equipment salesman who served a big territory. He understood farming, but elected to travel in a wider circle of go-getter types. He was also kind and sympathetic. By the end of the lesson he had impressed upon us how daring farmers were for trying to beat the heavy odds against succeeding at a harvest of early hay while it was still mud season. Dad called a career that required dealing with weather “a fool’s guess”. We also learned why we were lucky to be able to watch and understand this unfolding lesson where we could see it, in our own pastures. But we were safe from the financial challenges. My father traded the hay to our neighbors, the Vaughans, just to get our fields hayed, addressing the need to keep out brambles and weeds that cows shouldn’t eat, and to provide us with enough hay for our modest needs, which were for bedding, fodder and scratch hay for my grandfather’s turkeys and chickens (and their eggs)

Quirky local weather is king

Vermont has many microclimates, in part because of its geological history. Small farmers work every inch of that glorious land from the highest pastures of the Green Mountains to the floor of the Connecticut River Valley. Our 50-acre farm lay like a door-mat on the fertile plain of that valley, but the rush to harvest an early hay, or the decision not to attempt it, was happening everywhere in our little state, and all at once.

We would get news from Father’s weekly travels about the haying elsewhere. “They’re still not mowing in the Champlain Valley” maybe he’d report. He had seen bales in a high pasture over in the Vershire Hills, just west of us, but they were covered with snow and so on. Our total focus was on our two flat 25-acre fields, one on each side of our farm house. We knew from the farm kids at school that other farmers were ramping up to mow, rake, flip, dry and bale new hay everywhere around us, as soon as the weather permitted.

My father joked that if God controlled the weather then he was the one who needed to be appeased, fooled, dazzled or distracted. “He can be a practical joker at times,” he said, winking. The question was, if a farmer was going to sneak in such a neat stunt as an early hay harvest shouldn’t the farmer be very careful? If God knew, might he put obstacles in the farmers’ way? As our minister said, “To test him, to test his devotion”? It seemed like there was a, “side bet” between our dad and “Our Father”.

The tension was growing.

It was pre-spring. The days alternated between snow and mud. Most farmers were gun-shy and dazed by the deep dark winter they had just endured. Already skeptical about the benevolence of their God, a farmer could get discouraged from being house-bound and barricaded in their dark barns all winter dealing with rodents, frozen pipes and coughing cows. When the farmers returned to their kitchens, wives were waiting with “payable notices” illustrating the folly of a farming life. They felt vulnerable. The prospect of an early haying seemed further away than ever, but then it did every year.

Mud season was next. It held hands with winter. Those two soulless bullies worked together to test farmers’ resolve. Farmers felt helpless in their grip, and the sun seemed in cahoots with those darker elements of life because it offered only a few short winks in early May. “Was this spring”, they asked? It sleeted in April and froze tight every night for days sometimes, and maybe served up a blizzard for breakfast. Levity and faith were long gone by the time that the spring mud started to shift consistency from stinking brown glue in the barnyard to something more solid. But the fields were still soaking wet.

Wet fields? Were they the death warrant for early hay crops? A wet field normally meant one inaccessible to heavy farm equipment, and therefore useless until dry, but with a little luck and intense sunshine the ground might give rise to the green gold of the grass seeds within. If they could just get enough sunshine those seeds would explode to become a free bonanza of green early hay, but only in a field dry enough to work in. A windfall crop of sweet green hay would feed a farmer’s cows until the second haying season, in July, and would ensure that no hay need be purchased in the upcoming calendar year.

In Vermont the “early hay’’ was originally called “early mow’’. It was not baled. Teams of as few as two and sometimes as many as six work horses or mules hauled a man around who worked with horses, a “teamster,” upon a wood-frame contraption that combined pre- and post-industrial wood and metal embellishments. The wooden frame was as elegant as any stage coach and the iron parts included shiny as well as rusty parts, such as shearing bars, worm gears and iron seats.

The early mowers worked mechanically like a thousand men with sickles to lay the new grass low. Horse-drawn mechanical flippers or men with wooden rakes turned the grass over, on the same day it was mowed. This, done properly, dried out the hay enough to be “put-away”. Horse-drawn wagons were filled to the tops with loosely piled hay, which was lifted up using mechanical pulleys to be placed drooping over drying beams in the tops of barns, where the hay’s sweet perfume cleansed the stale air from the winter just passed. It was said such a barn was made “happy” by new hay. Cows’ eyes bulged upward as they bellowed in the milking level below as if trying to see through the floor above to the new hay they longed for.

This horse-powered equipment provided an advantage in its day. It could be operated in soaked fields before mud season had subsided, allowing access to wet fields without damaging them, as the weight of modern tractors, balers and trucks would have. Waiting for the proper surface conditions in those fields is what made the modern early hay process such a crap shoot .

Hay could be harvested when it was ready without farmers having to wait for equipment and manpower to converge on a field en masse. It could be gradually harvested more times during the season as it grew. The process was more controllable and flexible.

Above all it was a soulful process for both man and beast. There are still a few Vermont farmers who maintain horse and mule teams and the revered equipment that goes with farms with horses. Admiring them are amateur teamsters, purists, history buffs and people who still prefer the music of men’s voices coaxing animals forward to the sound of diesel tractors and metal balers. In some areas, drivers still park their cars along dirt roads in silent observance of this sacred event. But farming with horses has come to be seen as too slow and out of step with the times.

For the modern farmer and his quest for that early hay, he could only hope that his organizational skills and gambling spirit would see him through. These days, there are detailed weather predictions, radar and and satellite maps to show the regional picture, but it’s his personal experience and knowledge of his region that best tell him when to cut his hay. In our case in Thetford everything was temporary and nothing was as it seemed. It’s complicated. It tests your commitment. It leads you on. It dares you.

Is there enough time?

The fog over the valley floor and the heavy moisture it brings almost every day will dissipate by 9 a.m. if the sun is shining. Then will come a breeze. The heat of the sun on the valley floor will cause up-drafts, which will flow west through the hills of Vermont or east toward the hills on the New Hampshire side. In between is some of the most fertile soil in New England. The question is, can you wait for the sun to do its work and can you commit manpower and other resources enough to get the job done in time? If the farmer has his own hay-processing equipment, no matter how advanced, from cutting to storage, he’s in a stronger position; no one can let him down if he does it himself.

When it came to our two fields we aced it, but it was close. When the weather report said “no way” we had it hayed anyway. The Vaughan family, our aforementioned neighbors, made it happen. They arrived en masse when they saw that the rain that had been predicted for that morning did not fall. Sunny skies were forecast. The Vaughans made a commitment to cut both of our fields that day. They’d flip and rake them alternately and move from one field to another with Big-Red, the baler. We could see that there was still standing water near the fire pond (a source of water to put out barn fires) behind the barn. That area would be dry by midsummer and would have to wait.

The intense ‘baling day’

The Vaughans used two cutting tractors to get the hay down fast; both were working simultaneously. The flipper and rake alternated between the two fields.

Then came “baling day”. One year, the sky was overcast and the forecast was for rain by noon. As we had to wait for the morning dew to dry off, we were worried, but committed. The Vaughan family patriarch was unconcerned. Robert Vaughan Sr., who looked like someone in a Vermeer painting, decided that the hay would get baled and then stacked in his big barn by the end of that day, and that was that. Even if some of the last bales got a little wet, “We’re doing it”.

Just in case, he directed a couple of his five sons to go to the Vaughans’ barn and set up drying racks, where they’d be exposed to wind from the two enormous fans they had just installed. These fans were six feet wide and made the ends of the barn resemble an aircraft-test wind tunnel. This flow would ensure that our hay would retain its dryness in case the rain fell on the last day before we got the hay stacked. Mr. Vaughan wanted the new hay treated gingerly because it had a high alfalfa content and a limited tolerance to too much jostling.

Unlike with August haying, the alfalfa would stay in this new hay. When dry that early alfalfa would resemble flaked butterfly wings and if handled roughly would flutter down from the bottoms of the bales. This essence of the “first cut” must be maintained, otherwise why bother? Dryness was dicey for other reasons. The “good moisture” content was tricky to maintain, and “bad or deep moisture” would cause rot that would spread to hay around it.

Every bale in that bountiful harvest was loaded and trucked to the barn. The last three truckloads were stacked with the help of headlights of the other trucks and tractor. If we were lucky, the rain that might have been predicted held off until the last truck was mostly filled. A large tarp was fixed over the top and flapped wildly as we drove to the barn, where it was unloaded in the big alley in the center. Everyone helped and so it took only a few minutes. Then the big fans were turned on for the night. The sound that followed the throwing of the main switch gave the event a science-fiction feel. The fans chilled us as the breeze dried our sweaty, itchy backs. We would all seek relief lying in front of those fans in the sweltering days to come.

My brother and I always remember those times when the early hay was brought in.

Bill Hall is an artist based in Florida and Rhode Island. Hit this link.

Thetford, Vt. in 1912

— Photo by Mike Kirby

Linda Gasparello: Ice cream anti-socials in America's angry COVID-19 summer

— Photo by Xnatedawgx

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

You’ve heard of an ice cream social — an event in a home or elsewhere, using ice cream as its central theme, dating back to the 18th Century in America.

Thomas Jefferson became the first president to serve ice cream at the White House, in 1802. An epicure, Jefferson had his own personal recipe for vanilla ice cream.

Now, in the time of COVID-19 and President Trump, there are ice cream anti-socials.

These events feature meltdowns by customers in ice cream shops over having to wear face masks, having to stand six feet apart waiting in line — or even having fewer flavor choices on the menu. No Peanut Butter Caramel Cookie Dough? What’s America coming to? As Trump might tweet, “So terrible!”

The latest reported ice cream anti-socials in New England happened at Brickley’s, an ice cream shop with locations in Narragansett and Wakefield, R.I. In early May, one at Polar Cave Ice Cream Parlour in Mashpee, Mass., described by its owner as “insane,” made national news.

The Brickley’s events mirrored the one in Cape Cod in the rude, crude and socially unacceptable behavior of some customers.

Steve Brophy, who owns and operates Brickley’s with his wife, said in a June 22 Facebook post, “Over the last two weeks at both our locations, we have experienced on multiple occasions customers who will not wear their mask (asking us to show them the law) or are angry they can’t get exactly what they want due to the reduced menu. I, personally, had one man yell at me, ‘What’s your f—ing problem?’ because I had told him he needed to move his car which was blocking traffic. A few more expletives hurled toward me and I (for the first time in 26 years) told him to take his business elsewhere.

“Some of these customers are being verbally abusive to our young staff. That is unacceptable and will not be tolerated. I cannot ask our high school and college (age) staff to police the behavior of some who choose to ignore our rules.”

As if what these boors said wasn’t enough, Brophy also said in the post: “Another customer, who could not get exactly what he wanted, told our staff member, ‘You are babies. Are you going to let Gina hold your hand all summer?’ and ‘I hope you go out of f—ing business.’ ”

By “Gina,” the customer was referring to Gina Raimondo, Rhode Island’s Democratic governor, who issued an order on May 8 requiring all residents over the age of two to wear face coverings or masks while in public settings, whether indoors or outdoors. It’s the law.

The simple pleasure of going out for an ice cream, an all-American summer activity, is being taken away from adults and children, who’ve been holed up during the pandemic, by foul-mouthed people, partisan or not.

If they want to signal their vileness, maybe an enterprising one of their lot should open an ice cream shop: no masks, flavors like COVID-19 Cookies and Cream, and all abuse-spewing patrons welcome.

These ice cream anti-social events are likely to happen all over the country, especially as the summer and the 2020 presidential campaigns heat up.

July is National Ice Cream Month. I propose, a chilling out, a time for Americans to reflect on the nice tradition of ice cream socials and going out for an ice cream.

Don’t be a jerk. Stop hurling expletives and politics at shop owners and staff, the latter who include high school and college students who are trying to make a buck by scooping your ice cream, making your life a little sweeter.

Linda Gasparello is co-host and producer of White House Chronicle, on PBS. Her e-mail is lgasparello@kingpublishing.com.

Copyright © 2020 White House Chronicle, All rights reserved.

Keep updated on the White House Chronicle's latest hot-button issues at whchronicle.com

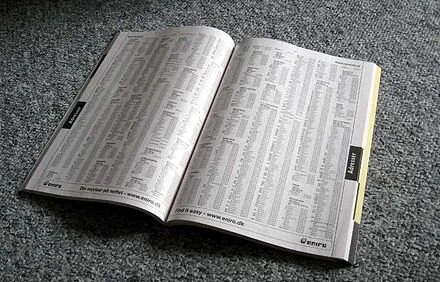

Better class of people

“I am obliged to confess I should sooner live in a society governed by the first 2,000 names in the Boston telephone directory than in a society governed by the 2,000 faculty members of Harvard University.

— William F. Buckley Jr. (1925-2008), writer, TV personality and conservative public intellectual.

The first telephone directory, printed in New Haven in November 1878

'I can't go on:' I'll go on'

“Beckett's Maze,’’ by Robin Crocker, at the Jamestown (R.I.) Arts Center. This is an in-progress photo.

The center’s parking lot is the site of this installation by Rhode Island-based artist Crocker, who has modeled the maze after the ancient labyrinth found in Chartres Cathedral, circa 1200 CE. She says she was influenced by Samuel Beckett's novel The Unnameable, quoted throughout the installation. Viewers will find Beckett’s words "You must go on" at the entrance of the maze, and his "I can't go on" and "I'll go on" stenciled on gold medallions alternating every six feet (social distancing!).

"In the midst of this global pandemic, faced with deeply rooted social injustice and political divide, now is a crucial time to contemplate our role, our impact, as part of this whole," she said. "A journey through Beckett's Maze offers an opportunity for this much needed introspection."

The arts center says she “drew on musings on consciousness to create an experience that mimics the journey through life, marked in equal parts by suffering (‘I can't go on’) and joy (‘I'll go on’).’’ The installation will end once the paint fades; it won't be repainted.

Secret anguish

Gardiner, Maine’s long-gone R. P. Hazzard Co. shoe factory in 1915

Whenever Richard Cory went down town,

We people on the pavement looked at him:

He was a gentleman from sole to crown,

Clean favored, and imperially slim.

And he was always quietly arrayed,

And he was always human when he talked;

But still he fluttered pulses when he said,

"Good-morning," and he glittered when he walked.

And he was rich—yes, richer than a king—

And admirably schooled in every grace:

In fine, we thought that he was everything

To make us wish that we were in his place.

So on we worked, and waited for the light,

And went without the meat, and cursed the bread;

And Richard Cory, one calm summer night,

Went home and put a bullet through his head.

— “Richard Cory,’’ by Edwin Arlington Robinson (1869-1935), who set many of his poems in the fictional community of Tilbury Town, modeled after Gardiner, Maine, where Robinson grew up.

In sleepy downtown Gardiner now