Showing evolution of color despite COVID-19

From “Invisible Language,’’ by Suelllen Guerreiro, in the University of Massachusetts at Lowell’s (now online only) Spring BFA exhibition. titled “Resilience’’. Guerreiro’s work is a graphic-design project that explores the evolution of color and how our experience of it has changed over time.

”Resilience’’ displays artwork created by the school's BFA candidates and tells how they rose to the challenge of finishing their graduation projects in the midst of the pandemic.

Boat tour in the Lowell National Historic Park, dedicated to the rise of the city as a pioneer of the American Industrial Revolution.

Don Pesci: In the pandemic, separating science and political science

Treating a patient on a ventilator in a hospital’s intensive-care unit

VERNON, Conn.

How scientific is science in the matter of Coronavirus?

There’s science and there’s political science. The one thing we do not want in any confluence of the two is confusion and mass hysteria, which can best be avoided by observing this rule: Politicians should decide political matters and medical scientists should decide medical matters. Occasionally, politicians decide that mass fright can better able convince the general population than rational argument.

The answer to the above question is simple: In the case of new viruses, science, as defined above, must be silent. There can be no “scientific” view of Coronavirus because it is a new phenomenon, the recent arrival of a stranger on the medical block. Concerning Coronavirus, there are, properly speaking, multiple views of different scientists, many of whom will disagree with each other on important points.

Does Coronavirus remain on surfaces for long periods? A couple of months ago, we were told by politicians, relaying the news from “science”, that hard surfaces were repositories of Coronavirus, and that contamination from hard surfaces was as likely as person-to-person contamination. That notion has withered on the vine now that we know Coronavirus is most often spread person to person.

Do adults spread Coronavirus to children, or are children the Bloody Marys? This is an important datum because if children, who are much less likely than adults to die or be seriously ill from Coronavirus, spread the virus to adults, the wholesale closing of schools might be a protective measure.

But if adults pass the virus to children, the current view of many scientists, remediation efforts would be far different. We are told that love covers a multitude of sins including, Agatha Christie advises us, murder. The word “science” misapplied covers, we have seen, a multitude of political sins.If we can learn from our past mistakes, we need not carry our mistakes into the future.

If the question is, “Have politicians in the Northeast made a mistake in trusting to some scientists?” the question is wrongly put. It’s not quite as simple as that. It will always be better to take advice from the horse’s mouth rather than from the horse’s posterior. But in the process, politicians must not allow differing scientists to determine the political course of a state.

Politicians, in the face of a pandemic, should not stop being politicians. That is what we have seen in Northeast states, where Coronavirus has dug in its heels. Here legislative activity has been shut down, and Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont has been festooned with extraordinary – some would say unconstitutional -- powers.

Like his counterpart in New York, Andrew Cuomo, Lamont has resorted to state-wide business shutdowns and sequestration. But inducing a long-lived recession in Connecticut, sequestration and data collection are not curative, however “necessary” they seem to be to some politicians who are masters in the art of spreading fear.

A vaccine may cure Coronavirus. What is called herd-immunity may reduce infestation. Certain people, in many cases younger people, catch the virus and develop a natural immunity, foreshortening the mass of people fatally exposed to the virus. We know that Coronavirus has spread like a wildfire in nursing homes, because clients in nursing homes are older and subject to other infirmities that in their cases have dramatically increased the fatality rate in Connecticut and New York.

“Science” – real science – warned us of this at the very beginning of the infestation. We knew of a certainty that older people with compromised systems were especially vulnerable. So, knowing this, why did not the governors of Connecticut and New York direct more of their resources to nursing homes? That is a question that must be answered by our “savior politicians.”

Home sequestration, we have been told, helps to flatten the Coronavirus curve. What can this mean if not that sequestration prolongs the time during which the sequestered may in the future be exposed to the virus? Flattening the curve is not curative. Ask any scientist.

The Coronavirus pandemic has been Hell, but it is very important that we should not return from Hell with empty hands.

In Connecticut more than 60 percent of deaths “associated with” Coronavirus occurred in nursing homes; the figure is similar in New York. Cuomo recently acknowledged he was surprised to discover that a sizable majority of people in New York infected with Coronavirus had been sequestered at home. His surprise is surprising.

We are told that business re-opening will occur in Connecticut in three stages, somewhat like a rocket on its way to the moon. But surely business opening should be determined with reference to sections of Connecticut that have been severely or mildly affected by Coronavirus, and the distribution of Coronavirus throughout the state has been mapped by Johns Hopkins University ever since the virus penetrated the United States from its point of origin, Wuhan, China.

These are political decisions that should have been codified in law by a quiescent General Assembly. Political science – yes, there is such a thing – would tell us that we no longer enjoy in Connecticut a republican, small “r”, constitutional government. Instead, Governor Lamont has become our homegrown Xi Jinping, China’s communist tyrant who has now provided Connecticut both with a deadly virus and PPEs, the means of thwarting some of its effects.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

Granite State an outlier

“There’s little question that Vermont (particularly Vermont), Maine, Boston, and Cape Cod, are, together, responsible for the New England image. New Hampshire just doesn’t fit in.’’

— Judson D. Hale Sr. , of Yankee Magazine, in “Vermont vs. New Hampshire, in the April 1992 American Heritage magazine

Shailly Gupta Barnes: In crisis, pols focus on helping the rich

Via OtherWords.org

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed fundamental inequalities in this country.

With millions of us hurting — especially the poor and people of color — there’s been widespread public support for bold government action to address long-standing social problems. Unfortunately, our lawmakers haven’t met the overwhelming need to focus on the poor and frontline workers.

Instead, trillions of dollars have been released to financial institutions, corporations, and the wealthy through low-interest loans, federal grants, and tax cuts — all without securing health care, wages, or meaningful income support for the unemployed. This is all unfolding as we enter the worst recession since the Great Depression.

As Callie Greer from the Alabama Poor People’s Campaign reminds us, “This system is not broken. It was never intended to work for us.”

This system treats injuries to the rich as emergencies requiring massive government action, but injuries to the rest of us as bad luck or personal failures. It reflects the belief that an economy that benefits the rich will benefit the rest of us, because it is the rich who run the economy.

It is easy to see how this plays out in policies that directly favor Wall Street, corporations, and the wealthy. But we see it even in policies that appear to be more liberal and equitable.

The CARES Act, for example, provided free testing for coronavirus, but not treatment. It offered unemployment insurance for some who’ve lost their jobs, but not living wages for those still working. It identified essential workers, but didn’t secure them essential protections.

The failure to fully care for workers and the poor is the flip side of the belief that the rich will construct a healthy economy out of this crisis. We see it directly as politicians slash money from public programs during this crisis while refusing to touch the accumulated wealth of the few.

In New York state, Gov. Andrew Cuomo passed an austerity budget that will cut $400 million from the state’s hospitals. In Philadelphia, Mayor Jim Kenney revised the city’s five-year budget to include government layoffs, salary cuts, and cuts to public services. Neither Cuomo’s nor Kenney’s budget made the proactive decision to tax the wealthy.

The same is true in Washington state, where Gov. Jay Inslee has been cutting hundreds of millions from state programs, anticipating major declines in tax revenue. This in a state that’s home to two of the wealthiest people in the world, Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates.

Of course, the rich are not the driving economic force in the country. It has become crystal clear during this pandemic that poor people, including frontline workers, actually fuel this economy. “We may not run this country,” said Rev. Claudia de la Cruz back in 2018, “but we make it run.”

But now we see the early rumblings of people coming together to assert this reality and challenge our faith in the rich.

Health-care workers, students, child-care givers, food-service workers, big-box-store employees, delivery drivers, mail carriers, and others are taking action to call out gross inequities and organize our society differently. Demands to cancel rent and to secure housing for all, universal health care, living wages, guaranteed incomes, and the right to unions are being heard all across the country.

Meeting these demands would not only secure the lives and livelihoods of millions of people — it would begin to release our economy from the suffocating grasp of the wealthy and powerful. Instead of waiting for wealth to trickle down, we would revive our economy by raising up the poor.

When you lift from the bottom, everybody rises.

Shailly Gupta Barnes is the policy director for the Kairos Center and the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival.

Inn a 'dreamlike atmosphere'

“Inn on the Harbor’’ (oil painting), by Niva Shrestha, of Arlington, Mass., as seen at Galatea Fine Art’s (Boston) online gallery. Galatea says the painting “has a humorous, almost carnival-like quality to it. The buildings seem to stand alone in a sun-washed, dream-like atmosphere. The artist plays with shadows and light; the buildings are treated as if they were pure form, and the deliberate juxtaposition of these angular forms create a Mondrian-like sensibility.’’

See:

and:

galateafineart.com

'And in the end defeat -- '

The waist is larger than the belt --

For put them side by side --

The one the other will exceed

With ease -- it cannot hide --

The foot is wider than the shoe --

For try them inch by inch --

The one the other won’t fit in --

Without a mighty pinch --

The mouth is greater than the will --

For show them something sweet --

The one the other will defy --

And in the end defeat—

—”The Waist Is Larger Than the Belt,’’ by Felicia Nimue Ackerman, a Providence poet and philosophy professor

Dooley a great URI president

The Chester H. Kirk Center for Advanced Technology at the University of Rhode Island main campus, in Kingston

— Photo by Kenneth C. Zirkel

David Dooley has been a great president of the University of Rhode Island. He’ll retire in June 2021.

He’s helped bring in the strongest and most diverse student body and faculty the university has ever had, who have done widely recognized research in URI’s nationally, and in some cases internationally, known centers of excellence. He’s overseen construction of functionally superb and architecturally important new buildings while improving the aesthetics of the already bucolic campus. He’s been very adept at raising money to steadily raise the university’s stature.

What makes the achievements of Mr. Dooley, a chemist by training, all the more impressive is that his tenure started in July 2009, a very difficult time because of the Great Recession. He’ll face new and familiar issues as he helps guide the university and his anointed successor through the next year, which is bound to be very difficult one for American academia. The university is lucky that he’ll be in charge as this crisis rolls on

Todd McLeish: Threats to Rhode Island's rare plants

Salt-marsh pink

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Only two populations of salt-marsh pink are left in Rhode Island, and they are at risk from sea-level rise.

David Gregg worries that not enough is being done to protect Rhode Island’s rare plants.

“There are a lot of plant species that we’re monitoring out of existence,” said Gregg, the executive director of the Rhode Island Natural History Survey. “We check them every year, and there are often fewer of them each year. The best-case scenario is that they stay the same, but many populations are getting smaller and smaller.”

He believes that conservationists must be bolder during the climate crisis if native wild plants are going to survive in the coming decades. Rather than simply monitoring the status of rare plants in Rhode Island, he is advocating for the use of more active strategies to boost plant populations.

“There’s been a big debate among biologists about how active we should be in trying to save rare species,” Gregg said. “Are we going to end up gardening nature? Aren’t we bound to make faulty decisions? If we get involved in active management of rare species, aren’t we doomed to screw it up?”

With little left to lose in some cases, the Natural History Survey has chosen to partner with the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management and the Native Plant Trust — formerly the New England Wild Flower Society — on an effort to propagate select species of rare plants and transplant them into the wild to augment existing wild populations and establish new populations.

The “Rhode Island At-risk Plant Propagation Project” is an outgrowth of the Rhody Native program, which was established a decade ago to help commercial plant growers propagate native plants for retail sale. At its peak, the program was growing 50 different species, but eventually just one species became dominant, a salt marsh grass used in restoration projects.

“Rhody Native became a commodity growing project, and that’s not our business,” Gregg said. “Our strength is in rare species — learning to propagate them and experimenting with them.”

The Natural History Survey’s “Propagation Project” began last year with the selection of four plants to propagate to test the concept: salt-marsh pink; wild indigo; wild lupine; and several varieties of native milkweed. The lupine and indigo were selected in part because they are the food plant for a rare butterfly, the frosted elfin. Just two populations of salt-marsh pink are left in Rhode Island, and they are at risk from sea-level rise.

“Our populations of marsh pink have very few plants, and we’re worried about inbreeding,” Gregg said. “The idea is to take plants from a Connecticut restoration site, cross pollinate them with plants from Rhode Island to reduce inbreeding, and then return some to Connecticut and use the others to reinforce the Rhode Island populations.”

The big challenge with this kind of project is learning how to propagate the plants in a greenhouse setting.

“These aren’t domesticated plants we’re working with,” said Hope Leeson, a botanist for the Natural History Survey who led the Rhody Native program. “We have to imitate the environmental conditions the plants are adapted to — the temperature, humidity, soil, water, and other factors.”

Salt-marsh pink is a particularly challenging example. It’s an annual species that produces a large quantity of seeds in a good year, but the seeds are extremely small — Leeson described them as “dust-like” — and they don’t tolerate drying, so they can’t be stored over the winter.

“We collected seeds in October and had to sow them immediately,” she said. “In the wild, they grow in a band of vegetation along the top of a salt marsh, where it’s a moist sandy soil mixed with peat. Periodically it floods as the tide comes in and then drains. I’ve got to come up with a soil mixture that’s like the natural conditions to make the plant happy.”

Wild indigo, on the other hand, is very drought tolerant and doesn’t grow well in moist or humid conditions. Its seeds, like those of wild lupine, must be scarified before they will germinate.

“A lot of species in the pea family have a hard seed coat that keeps them from taking in water until conditions are right for germinating,” Leeson said. “In the wild, lupine grows in sandy, gravely soil, so the seeds are likely to get abraded by the sand over the winter, allowing it to take in water to trigger the process of coming out of dormancy.”

To get lupine and indigo seeds to germinate, Leeson must first scratch them with sandpaper to simulate the natural scarification process.

Leeson and volunteers from the Rhode Island Wild Plant Society are raising many of the target plants in greenhouses at the University of Rhode Island’s East Farm and at a private site in Portsmouth.

Gregg said the project is being undertaken on a shoestring budget to demonstrate it’s potential.

“We hope someone will realize that we have this unique capacity to do research propagation of rare plants, and maybe that will help us find some funders to support the project,” he said.

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish runs a wildlife blog.

'Disguished as stones'

‘‘Watching the Breakers” (1891), by Winslow Homer

“In the beginning were the Words of God, disguised as stones:

like hard, black pupils dropped into the faithful’s eyes, these stones.

Waves hunched in worship shake the granite shore beneath my feet

as once it shuddered under the soles that colonized these stones.’’

— From “New England Ghazal,’’ by John Canaday, a poet and teacher who lives in Arlington, Mass.

Arlington’s famous municipal water tower was built by the Metropolitan Water Works between 1921 and 1924 in the Classical Revival style, to provide water storage for Northern Extra-High Service area, consisting of Lexington and the higher elevations of Belmont and Arlington. The design is said to have been inspired by the rotunda from the Samothrace temple complex, in Greece.

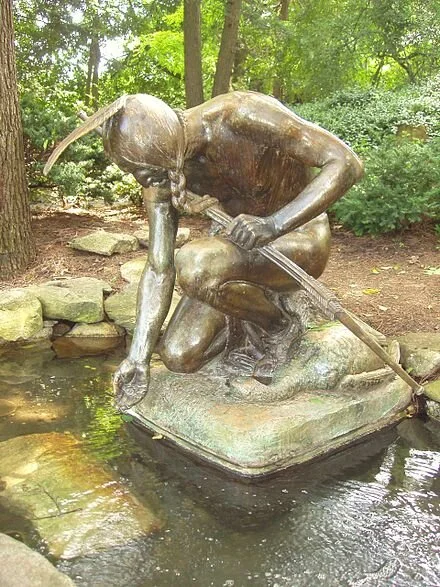

Menotomy Indian Hunter in Arlington Center, by resident Cyrus E. Dallin (1911)

Patriots' Grave in the Old Burying Ground in Arlington

Through the foliage

“Looking Up” (gouache on panel), by Vicki Kocher Paret (of Cambridge, Mass.), at the online gallery of Galatea Fine Art, in Boston.

Galatea’s text goes: “.A forest clearing can be detected somewhere in this mass of growth. The viewer is invited to find it. This painting by Vicki Kocher Paret beckons discovery as the eye is drawn to the horizon of the treetops. The sun chooses its illumination among the texture cast by leaves and branches.’’

See:

vickikocherparet.com

and:

galateafineart.com

David Warsh: ‘Helicopter money’ and other weapons to try to stem a depression

An HH-65 Dolphin demonstrating hoist rescue capability

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

In the early stages of the 2016 presidential campaign, Ben Bernanke undertook a three-part essay, “What Tools Does the Fed Have Left?” It appeared on the Brookings Institution site. The economy was growing and creating jobs, the former Federal Reserve chair explained. The recovery, he thought, would surely continue. But at some point “in the next few years,” the economy might slow, he wrote – “perhaps significantly.”

He asked, “How would the Federal Reserve respond in that case?”

The first little essay discussed offering negative interest rates on government bonds. That means the purchaser would be paying for the privilege of lending the government money to be paid back in due course as only slightly less than the sum that was lent. Japan pioneered the practice, only to be back-footed by the virus pandemic. The British government last week sold its first bonds with a negative yield. But under chair Jerome Powell the Fed has already ruled that out as too rough on the banking system.

Bernanke’s second article examined the possibility of targeting long-term interest rates instead of the very short-term ones with which the Fed ordinarily conducts monetary policy. Under depression-style conditions, with short rates so low that there was no room to cut them, the Fed might seek to create a peg – that is, place limits – on two-year. three-year or five-year government bonds, by offering to buy them back at a certain fixed rate, paying more than what otherwise would be their market value, placing a ceiling on their price and yield.

The third essay was about “helicopter money” – that is, a last-ditch policy against stubborn high unemployment that, in its strict form, has never been tried. That essay seemed to me the one especially worth reading, connected, as it is, with the enormous deficits occasioned by the pandemic.

Helicopters have nothing to do with it, of course. Instead money-financed public spending involves balance sheet jiggery-pokery. Suppose the economy is deeply, truly stuck. Congress approves a few trillion dollars – half for public works, half for tax rebates. The budget deficit soars. But the government doesn’t borrow to finance its spending. Instead it prints money. The Fed credits the Treasury’s central bank checking account and the Treasury spends the money to pay for the agreed-upon public works and tax rebates. Jobs are created, household incomes rise, prices climb thanks to the new money in circulation (a one-time surge in inflation, as sophisticated investors believe it will only happen once).

The economy begins to climb out of its desperate straits, with no increase in future tax burdens. When he wrote, Bernanke judged it highly unlikely that the measure would be used. With the need to restore confidence in the wake of the shutdown, it seems somewhat more plausible – a little like shooting sulfur particles into the upper atmosphere in hopes of controlling climate warming.

I am in no mood today to write about Big Bazookas, much less TLTROs (targeted long-term refinancing operations) or MFFPs (money financed fiscal programs). I continue to be preoccupied with psychological aspects of the response to COVID-19. Having no fact-based expectation of when it might end is what makes it depressing.

But if you want to read about what helicopter money could mean – and why its distant cousin modern monetary theory is bunk – you can’t do better than to start with Bernanke.

When he first introduced the topic of a helicopter-drop in, 2002, in “Making Sure ‘It’ Doesn’t Happen Here,” the Fed’s press-relations officer advised him to leave metaphor out of his speech. “It’s just not the sort of thing a central banker says,” he was told. Bernanke went ahead, and a good thing too. That was then, when he was one of seven governors, four years before President George W. Bush named him chairman.

They say it now. They just need a better metaphor.

xxx

In a report to bulldog subscribers, I wrote a careless sentence the other day. about The National Bureau of Economic Research. The NBER, like Harvard and MIT, I lamented, was shut down. The universities had sent their students home and closed their libraries. But the 1,300 or so research associates of the NBER were already home. That was the point of the 1970s restructuring that turned a productive but slow-moving little research institute in Manhattan into a world-girdling network of university researchers energetically comparing notes with oneanother.

I asked NBER President James Poterba, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, how the pandemic has affected operations at “the Bureau” – its Summer Institute, in particular, which ordinarily brings nearly 3,000 economists to Cambridge over a three-week period in July. It was true, he replied, that the NBER had no immediate plan to return to its Putnam Square headquarters, in Cambridge. Otherwise, “shut down” couldn’t be further from the truth. Keeping up in its customary manner of doing business with the changes wrought by the virus had, he said, made the operation feel “on many dimensions, like a fast-growth startup.”

He continued:

The outpouring of research related to COVID-19 is the most visible change. Including the 21 new papers that will be released early this week, there are now 115 papers in the NBER working paper series that are related to COVID-19. The production of these papers does not seem to have come at the expense of other research. During the last eight weeks, 310 new working papers have been distributed. The same eight-week periods in 2019 and 2018 saw 171 and 188 papers, respectively. Our working paper team is working harder than ever to keep up with this burst of new research activity. Next week we will be releasing 57 new working papers; in a typical week in the last few years, we would release about 23. The economics profession’s pivot to studying many aspects of the pandemic is just remarkable.

“The other visible change in NBER activity is with regard to conferences. Our last in-person meeting was on Friday March 6. Spring is a busy time for research meetings, and we had 39 conferences of various types scheduled between March 6 and June 30. Twenty-five have been postponed or cancelled, but 14 have gone virtual. We’ve held 8 on-line meetings so far, with six more scheduled in the next five weeks. The NBER conference team has learned a lot about managing a virtual event, and meeting organizers, presenters, and participants have all shown great flexibility and resilience when an unexpected software glitch or a breakdown in internet connectivity results in an unscheduled conference interruption. This year’s Summer Institute will be virtual. The meetings will typically be shorter than their in-person counterparts, and scheduled to try to accommodate participants from many time zones. We are also hoping to live-stream many of the meetings to make them broadly accessible.

My assessment – and others might disagree – is that on-line presentations have worked quite well for summarizing the findings of completed papers. The comments from assigned discussants also work well. The greatest differences between the in-person and the on-line experience seem to be in the dynamic of question-and-answer and (not surprisingly) in the opportunity for informal interaction away from the presentation. I have seen some Q&A periods work well, most often when the organizer takes the initiative to encourage some participants to ask questions or when one member of a co-author team is presenting the paper, while another member is active in chat channel answering or clarifying questions as they arise. Collectively, economics – and, I am sure, all other disciplines – are working to find good ways to foster interaction in the virtual setting.

This is likely to be particularly important for early-career scholars, who do not have established networks and who have traditionally depended on conversations at professional meetings, often at lunch or dinner or over coffee outside the formal presentations, to meet other researchers and to begin collaborations. Although virtual meetings struggle with regard to networking, they excel with regard to convenience. Some on-line NBER meetings in the last two months have attracted audiences that are more than twice as large as their usual in-person analogues. NBER is hardly alone, and is not in the vanguard, in discovering this. There are a number of weekly, virtual, seminar series that have been organized by various economic researchers; some have attracted many hundreds of participants. It’s still a bit early to judge the impact of virtual meetings on the long-term evolution of intellectual exchange within economics, but my best guess is that there will be substantially greater demand for virtual meetings in the future.

Finally, a less visible but no less consequential development over the last ten weeks, has been the sharp acceleration of grant application activity by economists. Fuing agencies like the NSF and the NIH as well as large private foundations have announced rapid-turnaround grant programs to support researchers who are studying various aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic. The research community has responded to these funding opportunities with great enthusiasm. The NBER serves as the administrative home for a wide range of research grants, and our grant administration team has seen a sharp uptick in the number of proposals that researchers are submitting to various funding organizations. As the research community begins to get access to new data sets, to surveys, and to other information on both the health and the economic developments of the last few months, I expect that we will learn an extraordinary amount about the nature and impact of the pandemic and the counter-measures that were deployed to fight it.”

David Warsh, an economic historian and veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated. Copyright 2020 by David Warsh

A new crop

Giant kelp before harvesting

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

We New Englanders think more about lobsters as we head into summer. But they’re disappearing from much of the southern New England coast, apparently mostly because of warming waters. Waters are warming in the lobster heartland of the Maine Coast, too, but not too much yet to slash harvests. At the same time, key finfish species are declining. So to find other ways of continuing to work on that storied coast, some former and current lobstermen and other fishermen are getting into oyster and other shellfish aquaculture, and now kelp, which is sold as a very healthy food.

The kelp farms have another attribute:

Our fossil-fuel burning is loading carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, much of which of it then goes into the oceans, where it makes the water more acidic. Among other damage, this harms the development of the shells of oysters, and hurts lobsters, too. But kelp farms reduce the acidity of the water around them, creating sites not only better for shellfish but also for other creatures.

Forgotten but familiar

“It is easily forgotten, year to

year, exactly where the plot is,

though the place is entirely familiar—

a willow tree by a curving roadway

sweeping black asphalt with tender leaves….’’

— From “Memorial Day,’’ by Michael Anania

The worst fear

H.P. Lovecraft’s grave in Providence’s famous Swan Point Cemetery

“The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown.’’

— H.P. Lovecraft, Providence-based writer of science fiction and horror stories.

Llewellyn King: Lessons and unknowns in the COVID-19 crisis so far

— Photo by Thomas Jantzen/SPÖ

Snapshots. That’s what we have of the United States as we emerge tentative and fraught from lockdown.

We don’t have the whole picture, just snapshots of this and that.

Some of the snapshots are encouraging: The air is clearer, crime is down and a collective spirit is apparent in many places.

Others are more disturbing: The pandemic has become politicized.

Those to the right are demanding a total reopening of the economy; they’re abandoning masks and social distancing. And they’re using fragments of information to justify their cavalier attitude toward the great human catastrophe: They insist the government can’t tell them what to do, even if it endangers countless others.

The mainstream, meanwhile, reflects a cautious approach of phased-in reopening of the economy, masks, social distancing and sanitization.

Snapshot: People of middle age and older are conspicuously more cautious than the young.

Snapshot: Caution has no coherent spokesperson, unless you count New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo.

Where, one wonders, is Joe Biden, the presumptive Democratic nominee to challenge President Trump in the 2020 race? He has, one reads, held dozens of election events, but his voice hasn’t been heard. (Can the liberal press be held accountable? Hardly.) Biden snapshot: a distant figure, out-of-focus.

Every time I catch a Biden speech, he’s talking about his family, his Pennsylvania roots, or the tragic loss of his son Beau to cancer. He hasn’t found the words that give strength to a distraught and suffering people.

If Biden has great ideas about the future, about how we will emerge from this terrible time, they haven’t been heard. Maybe he should hire a speechwriter; plenty of good newspaper people out of work.

Snapshot: A new federalism, as espoused by Trump: If it goes right, it’s my achievement. If it goes wrong, the governors are to blame: The buck never stops here.

More Trump snapshots: Obama is to blame; Mueller is to blame; China is to blame; inspectors general are to blame; villains at every turn.

Snapshot: Immigrants are heroes at the top and the bottom.

Every other doctor interviewed on television for their expertise about the pandemic, it seems, has an accent: That shows the power of immigrants in science. Immigrants also carry the load in the most dangerous job in the United States: meat processing and packing. It is high-risk, low-pay work.

The immigrant effect is encompassing and a source of value to all Americans.

Snapshot of health care: A system unequal to the job.

There are overworked and under-supplied healthcare workers, plus many patients who won’t be able to pay their hospital bills. Wait until the invoices start arriving across the country, spreading destitution. If the Supreme Court rules against Obamacare, the destitution will be complete: a black, financial hole swallowing millions of Americans.

Snapshot: The poor are poorly. Hispanics and African Americans are bearing the brunt of the financial pain, and a disproportionate number of infections. Because so many are on the lower rungs of the employment ladder, they’re completely out of money now, and may find they have no jobs to return to as restrictions lift. This may be the ugliest snapshot in the gallery.

Saddest snapshot: Americans lined up in the tens of thousands to get a handout from the food banks. Mostly, one sees long lines of cars waiting for bags of food. Those are the lucky ones: They have cars. The needy must walk.

Happiest snapshot: Science is back, despite the Trump administration’s attempts to hobble it.

The public wants medicines for many conditions, and the rush to find answers for COVID-19 will lead to many discoveries that will benefit other sufferers with other diseases. War spurs innovation, and that’s what we’re getting.

Hard-to-read snapshot: How many companies will survive? Will we have just one national airline? Fewer utility companies? Will retail and office space be on the market for decades? How many people will work from home full time going forward? A boom in self-employment, leading to many startups and innovations galore?

Interesting snapshot: Will the impressive governors and mayors who have emerged during the pandemic save us from the political mediocrity that characterizes the national scene? Check out Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan (R) and Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms (D).

Keep snapping and wearing a mask, things will come into focus: good and bad.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Global ambitions

“June Graduate” (1920, oil on canvas), by J.C. Leyendecker (1874-1951), Saturday Evening Post’s June 5, 1920 cover, at the National Museum of American Illustration, Newport, used with museum’s permission.

Before social distancing

“Dancing on Air” (acrylic), by Matthew Peake, in Galatea Fine Art’s online (pandemic) gallery. The explanatory text with this: “A bird's eye view of a stunning moment; this is an unusual view of a lively wedding dance. The energy is dizzying when looked upon from this point of view, but the joyous place in time is forever captured.’’

Matthew Peake, M.D., who lives in Rockingham, Vt., which is on the Connecticut River, was a primary-care physician in the Brattleboro, Vt., area for many years before becoming a full-time artist in 2006.

See:

and:

galateafineart.com

Pleasant Valley Grange Hall, next to the Rockingham Meeting House, in Rockingham, Vt.

Q&A on saving students money via OER

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (NEBHE)

BOSTON

In the following Q&A, NEBHE Fellow for Open Education Lindsey Gumb asks Thomas College Provost Thomas Edwards about the Waterville, Maine, college’s plans to use a new grant from the Davis Education Foundation. The college’s focus on melding access and affordability through OER (Open Educational Resources) is especially relevant in the current shift to online learning at many campuses.

Founded in 1894, Thomas College offers undergraduate and graduate degrees in programs ranging from business, entrepreneurship and technology, to education, criminal justice and psychology.

Six in 10 students at the Waterville, Maine-based institution are “first-generation” college-goers who come from modest means. Thomas is a pioneer in so-called “job guarantees,” in which the college will make payments on federally subsidized student loans or provide tuition-free evening graduate courses for students who are unemployed at six months after graduation. Recently, Thomas added to its “employability” menu a master’s degree in cybersecurity, a co-curricular transcript that allows students to flaunt their leadership development, community service, internship and job shadow experience, and even a golf-readiness program given the student body’s relatively humble roots and how much career networking occurs on the links. Thomas President Laurie Lachance served as a member of NEBHE’s Commission on Higher Education & Employability and as a panelist on NEBHE’s 2019 roundtable on “The Future of Higher Education and the Economy: Lessons Learned from the Last Recession.”

In January 2018, Thomas College received a grant from the Davis Educational Foundation to redesign 30 courses over three years to help save students money on textbook costs—a well-documented and significant barrier to student success. To illustrate, a 2018 survey of Florida’s higher education institutions shows that 64% of students aren’t purchasing the required textbook for their courses because of the high cost, 43% are taking fewer courses, and 36% are earning a poor grade just because they were unable to afford the book. A 2018 study out of the University of Georgia by Colvard, Watson & Park additionally shows that OER goes beyond addressing affordability: OER enables increased learning and completion rates, while also addressing achievement gap concerns for historically underserved groups of students.

Here, Thomas Edwards, provost at Thomas College and member of NEBHE’s Open Education Advisory Committee, shares some insight into his institution’s progress with its Davis grant and how the results are increasing equitable attainment of a postsecondary education for Thomas students.

Gumb: The grant you received from the Davis Educational Foundation is helping Thomas College faculty convert 30 courses over three years using OER. What disciplines are represented in this mix? What does progress look like two years in?

Edwards: From the beginning, we recognized that there were two key goals of the Davis Educational Foundation grant. The first was student success, especially as it is tied to finances. We’ve been able to bring costs down dramatically for students—we had one course that went from a $253 textbook to no cost for students using OER. That’s a real savings for our students.

The second goal is pedagogical. Reworking a course to rely on OER is time-consuming but rewarding. It allows a faculty member to incorporate current materials and to design a course that mirrors the real-world environment: locating sources, analyzing data, communicating and working with real-time information.

To date, we’ve had faculty from across the disciplines participate: science, criminal justice, political science, education, economics, history, psychology, marketing, business finance and philosophy. We have been able to document thousands of dollars in savings to students. Students also report high satisfaction rates—91% indicate that they positively benefited from OER. Student performance as measured by grade distribution shows no statistically significant difference between OER and non-OER versions of the same course. It’s been a win-win across the board for students, faculty and the teaching and learning environment.

Gumb: Thomas College is regionally ranked #8 for social mobility by U.S News & World Report. How has OER played a role in positioning your institution for this achievement?

Edwards: We wanted to use OER to address both access and affordability. If a student can’t afford a book, if they add a course late, or if they have to wait until their financial aid comes in before they can purchase a text, they are already disadvantaged and potentially disengaged from a course. We don’t want them to fall behind.

We very intentionally focused the first courses that we redesigned on those entry-level courses that enroll higher numbers of students. We wanted to have an impact on student engagement and retention. Our success in social mobility is tied to our ability to help students make progress to their degrees.

We want students to be positioned for success. We want students and faculty to have the tools they need at their disposal from day one. That’s simply not the case when dealing with traditional texts. More than half of our students have reported that there have been times when they couldn’t afford the text. They also report that OER materials are more engaging than traditional textbooks. OER eliminates those barriers—motivational and financial. Students can focus on learning, faculty can focus on teaching … and the materials they need are right there for everyone to access.

Gumb: What kind of feedback have you received from your students?

Edwards: Students have embraced OER. Finances are one of the first things they notice. One student commented that “OER benefited my wallet.” But students also notice other aspects of course design. They comment that OER courses seem timelier and more relevant. They find OER courses to be more creative in presenting information. And here’s an interesting perspective: Students observe that because OER materials come from a variety of sources, they find less bias and subjectivity because the materials are more current and are updated more frequently. If we want our students to be information-literate, OER-based courses are one important way to get there.

Gumb: What has the faculty response looked like? Is participation mandatory, and if not, how are you incentivizing participation?

Edwards: Faculty response has also been very positive. Because we are talking about course redesign, we identified participation we wanted to encourage, but not mandate. We wanted to use the grant to demonstrate the benefits to both students and faculty and to encourage progress on both the financial and pedagogical fronts. The Davis Educational Foundation allowed us to provide an incentive through a stipend or a course release for faculty to work together on their redesign. Each semester, we have five slots open for faculty to propose a course. They work together as a cohort, sharing what works and what issues they are encountering.

Many people think that OER is about finding the right online version of a textbook, but it’s much more complex than that. The faculty workgroups spend their time discussing pedagogy and course design.

How do we encourage students to read critically? To engage? To interact? How do we structure assessment? What kinds of activities help build real learning? These are the conversations that bring other faculty into the mix, to encourage them to consider their own courses and how they might adapt. Our faculty report feeling more energized about their course revisions. They value the opportunity to work across disciplines and departments. And in the process, information and library services are integrated in more direct and meaningful ways with course design and delivery.

Gumb: OER are free for students, but they’re not free to create and maintain. How do you intend to address issues of sustainability when the grant money runs out?

Edwards: Sustainability is always a great question. We have engaged our librarian and Information Technology staff from the very beginning to work with the faculty, and they have now built up a great set of reference tools for anyone interested in adopting OER tools in their course design. We’ve involved our Faculty Development committee as well and highlighted at Faculty Senate meetings how OER can be effective for teaching and learning. We make the courses that have been redesigned available for others to adapt or adopt.

It’s ultimately about building into the campus culture a recognition that we need to continue to be conscious about the choices we make as a faculty and how those choices can impact student learning and student success.

Gumb: What advice do you have for senior leaders at independent institutions who might be just starting out with OER initiatives?

Edwards: Our focus from the very beginning was to be explicit about our goals: We wanted to define this opportunity as pedagogical as well as financial. We wanted to be clear that these concepts can and should go hand in hand.

Everyone across the campus can agree on the centrality of student success. Focus on success and focus on student learning. Use data effectively and make sure you can measure your success. We have had faculty at the front and center of the project design and it has worked extremely well. Faculty want their students to learn. OER can help.

In New England's greatest valley

Connecticut River Valley c. 1907, looking toward Orford, N.H. from Fairlee, Vt. Note the capacious open land, some of which was used by sheep farmers supplying the wool for textile mills in southern New England.