'Controlled panic'

Sandpiper

“The roaring alongside he takes for granted,

And that every so often the world is bound to shake.

He runs, he run to the south, finical, awkward,

In a state of controlled panic, a student of Blake….”

— From “The Sandpiper,’’ by Elizabeth Bishop (1911-79). A Worcester native, she travel widely, and lived abroad for stretches but always returned to New England.

'All that is good and noble'

The Rogers Building, in Boston’s Back Bay district, was opened in 1865 as MIT’s first building erected specifically for the institution. MIT, founded in 1861 and often called “Boston Tech’’ in its earlier years, was moved to Cambridge in 1916.

“I never fully realized how much a New England birth in itself was worth, but I am happy that that was my lot. I have felt it so keenly these last few days. Dear old New England, with all her sternness and uncompromising opinions; the home of all that is good and noble.”

― Matthew Pearl, in his novel The Technologists, set in the early years of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Perfectly clear

Here's one thing Trump has made perfectly clear:

Nixon was hardly this country's nadir.

— Felicia Nimue Ackerman

N.E. responds to pandemic: Spot the robot helps out; Vermont Teddy Bear switches to PPE's

Spot helping out at Brigham and Women’s Hospital

From our friends at The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

As our region and our nation continue to grapple with the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) pandemic, The New England Council is using our blog as a platform to highlight some of the incredible work our members have undertaken to respond to the outbreak. Each day, we’ll post a round-up of updates on some of the initiatives underway among Council members throughout the region. We are also sharing these updates via our social media, and encourage our members to share with us any information on their efforts so that we can be sure to include them in these daily round-ups.

You can find all the Council’s information and resources related to the crisis in the special COVID-19 section of our website. This includes our COVID-19 Virtual Events Calendar, which provides information on upcoming COVID-19 Congressional town halls and webinars presented by NEC members, as well as our newly-released Federal Agency COVID-19 Guidance for Businesses page.

Here is April 24 roundup:

Medical Response

UMass Memorial Receives $120,000 Grant for Telemedicine – UMass Memorial Health Center has received a $120,000 grant to implement and expand telemedicine technology during the pandemic. The hospital aims to specifically prioritize spending on pediatric and emergency units as well as on remote primary response areas. The Worcester Business Journal has more.

MIT, Beth Israel Collaborate to 3-D Print Testing Materials – Faced with a shortage of essential testing materials such as swabs, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) entered into a partnership to 3-D print the necessary materials. Four prototypes have since been clinically validated, and the hospital expects to soon be able to produce more than a million swabs per day Boston.com has more.

Economic/Business Continuity Response

Brigham and Women’s Hospital Using Robot to Reduce Staff Exposure – To reduce infections of COVID-19 among staff, Brigham and Women’s Hospital has begun using a four-legged robot (named Spot) from Boston Dynamics to allow providers to remotely video conference with patients in triage tents. The technology allows for reduced exposure between patients and providers and streamlines the testing process. Read more from Boston.com.

Vermont Teddy Bear Factory Producing Equipment for Essential Businesses and Healthcare Providers – With production halted, the Vermont Teddy Bear Factory, in Shelburne, has pivoted operations to produce face masks and other personal protective equipment (PPE) for both healthcare providers and essential workers. In addition, the company will make the masks from recycled materials to remain sustainable. More from WCBS

Community Response

Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts Pledges $107,000 for Community Relief – Health insurance provider Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts (BCBS) has announced more than $107,000 to support nonprofits in the Commonwealth, including the United Way of Massachusetts Bay and Merrimack Valley, that provide relief and aid. The additional support comes after BCBS had previously announced over $1.1 million in other relief measures. Read more in the Lynn Journal.

UnitedHealth Group Donates $5 Million for Treatment Development – UnitedHealth Group has pledged $5 million to support a federally-sponsored program that aims to develop a plasma treatment for the virus,. The effort is led by the Mayo Clinic and utilizes the plasma from recovered COVID-19 patients as a potential treatment. Read the release here.

Webster Bank Commits $100,000 to Support Efforts – Webster Bank has donated $100,000 to United Way to support efforts to aid communities affected by the pandemic. The funds will be used to provide food, childcare, and other services to organizations strained by revenue losses. The Hartford Business Journal reports.

Stay tuned for more updates each day, and follow us on Twitter for more frequent updates on how Council members are contributing to the response to this global health crisis.

'A certain coolness from him'

Panther Mountain in the Adirondacks

“Besides the wear of iron wagon wheels

The ledges show lines ruled southeast-northwest,

The chisel work of an enormous Glacier

That braced his feet against the Arctic Pole.

You must not mind a certain coolness from him

Still said to haunt this side of Panther Mountain.’’

— From “Directive,’’ by Robert Frost (1874-1963), who lived much of his last decades on the western slope of the Green Mountains; the Panther Mountain probably referred to here is in New York state.

Grace Kelly: Warm-water fish have been moving into Narragansett Bay

Sea robins are one of the species that have been moving in as Narragansett Bay warms.

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

On a normal Monday morning, University of Rhode Island graduate student Nina Santos would head to the Wickford Shipyard, in North Kingstown, R.I., pull on some waterproof gear, and board the Cap’n Bert.

“My dad was a fisherman, so I grew up around fishing and boats but I had never been out on the water on a fishing boat before,” she said. “I had been on my dad’s fishing boat when it came to port but never out on the water, so now I feel like I’m getting to experience what he did for a living.”

Santos and the boat’s captain, Stephen Barber, would normally set sail around 8:15 a.m., measuring the water temperature, oxygen, and salinity levels, and then casting a net out at various checkpoints. They would pull up the net after 30 minutes of cruising at 2 knots, then identify, group, measure, and weigh the fish they caught before tossing them back. This would continue for about 4 hours, before Barber would turn the Cap’n Bert around at Whale Rock and slip back into the Wickford Shipyard around 12:15 p.m.

But the past month or so of Mondays have been anything but normal. The coronavirus hasn’t only shuttered universities around the world, it’s also shuttered much of researchers’ field work, and for Santos, that means a gap in URI fish-trawl records dating back to 1959.

“It’s kind of sad to have this big data gap in the trawl survey but it’s not the first time it’s happened,” Santos said. “So, I don’t think it will change too much, but it is a little bit sad because now is when we would actually see things moving back into the bay.”

Before the coronavirus derailed the weekly trawl, Santos was continuing a 61-year legacy of scooping fish out of Narragansett Bay to paint a picture of its inhabitants.

The story of the fish trawl starts, appropriately, with a couple by the name of Fish.

Charles Fish and his wife, Marie, were longtime members of the marine biology community with a long list of accomplishments: Marie collected and studied fish and marine sounds; Charles was a pioneer in the study of zooplankton. In 1925, the couple were a part of an expedition to study the Sargasso Sea led by naturalist and explorer William Beebe.

Charles and Marie Fish attending the dedication of the Narragansett Marine Laboratory in 1948. (URI)

But their lasting legacy lies in the creation of the Narragansett Marine Laboratory, which opened 72 years ago, as a part of the School of Arts and Sciences at Rhode Island State College — what would become URI — and in a fish trawl that has collected an astounding amount of data.

“The goal was to measure the seasonal occurrences and abundance of fish in the bay,” said Jeremy Collie, a professor of oceanography at URI who runs the program today. “Part of it was to catch the fish that were in the bay from week to week and actually be able to identify them, and perhaps link that with the soundscape that Marie Fish was hearing.”

Collie took the helm of the program in 1998, after H. Perry Jeffries retired. Jeffries was one of Fish’s original assistants, who took over the program in 1966 after Fish retired.

“Jeffries was one of the first assistants, and when he got the job here as a professor, he decided he would keep the program going. It was really Perry who started looking at the longer-term trends of the fish populations,” Collie said. “When he retired, I took over and the longer we keep going, the more interesting it becomes. It’s a very rich data center.”

While the program has noticed changes in local marine populations, including a shift from fin fish species to more invertebrates such as crabs and lobsters, one of the biggest differences over time has been the introduction of many more warm-water species.

“Since the year 2000, it’s become more and more obvious that it’s the changing climate that is affecting fish populations,” Collie said. “The community is shifting because the cold-water species are less abundant than the warm-water species, which are way more abundant. That’s the big signal that we are measuring.”

Santos has noticed this shift, especially during her wintertime trawls.

“We’re not really catching much right now; it’s surprising how little we do catch. There’s such a disparity between the winter catch and the summer catch, and I think that part of that is the shift that Narragansett Bay has had towards warm-water species,” she said. “There’s not really anything left once winter hits; all the species that would have been here in the winter in the cold waters are not around anymore. They’ve moved north.”

Some flashy examples of warm-water visitors include orange tilefish, sand tiger sharks, and an errant sailfish. There also are two warm-water residents of Narragansett Bay that are so common you might think they were native species: striped sea robin and scup.

“We’ve been studying the striped sea robin in particular because we’re interested in the impact they have on the fish community,” Collie said. “Sea robins kind of swim around on the bottom, vacuuming up everything that’s in their path, and so we’re trying to estimate their impact on the community, on the invertebrates and the fish they may be eating. So, it’s not only that these species are changing in abundance and increasing, they are also having an effect on the food web.”

As for scup, there is a healthy population of the fish also known as porgy in Rhode Island waters. In 2017, the state landed more than 6 million pounds of the bony fish.

For Collie, the reason for its abundance lies in the warming of Narragansett Bay.

“The easy answer to why there are so many is that they’re a warm-water species, and the water is getting warmer so there are more of them,” he said. “The scup population as a whole, coast-wide, is in good shape. There’s a healthy scup population out there.”

As the bay has warmed, with the surface temperature on Jan. 25, 1959 registering 33 degrees Fahrenheit and on the same day in 2017 registering 40 degrees Fahrenheit, the URI trawlers have been there to document it, and they will continue to do so — once the pandemic is squashed.

Grace Kelly is a journalist with ecoRI News.

A Cadillac of a view

“The Holy Family of Cadillac Mountain,’’ by Eleanor Steinadler (Lambda print), at Galatea Fine Art, Boston. The mountain, 1,530 feet high, and in Acadia National Park, Maine, is the highest point within 25 miles of the Atlantic shoreline of North America between Cape Breton Highlands, Nova Scotia, and peaks in Mexico. During part of the year, it’s the first place in the U.S. from which you can see the sunrise.

Don Pesci: Those gubernatorial Caligulas

Decisive executive: A marble bust of Caligula restored to its original colors, identified from particles trapped in the marble

VERNON, Conn.

Gore Vidal – deceased, but not from Coronavirus complications – was once asked whether he thought the Kennedy brood had exercised extraordinary sway over Massachusetts. He did. And what did he think of the seemingly unending reign of “Lion of the Senate” Edward Kennedy, who had spent almost 43 years in office?

Vidal said he didn’t mind, because every state should have in it at least one Caligula.

The half-mad Roman emperor Caligula, who reigned in 37-41 A.D., considered himself a god, and the senators of Rome generally deferred, on pain of displeasure, to His Royal Deity. Caligula certainly acted like a god. The tribunes of the people deferred to his borderless power, which he wielded like a whip. They deferred, and deferred, and deferred… .Over time, their republic slipped through their fingers like water. Scholars think Caligula may have been murdered by a palace guard he had insulted.

Here in the United States, we do not dispose of our godlike saviors in a like manner. At worse, we may promote them to a judgeship, or they may be recruited after public service by deep-pocket lobbyists or legal firms, or they may remain in office until, as in Edward Kennedy’s case, they have shucked off their mortal coil and trouble us no longer

.Coronavirus has produced a slew of Vidal Caligulas, all of them governors. In emergencies, when chief executives are festooned with extraordinary powers, the legislature is expected to defer to the executive, and the judiciary remains quiescent.

This deference to an all-powerful executive department is not uncommon in war, but even in war, the legislative and judiciary departments remain active and viral concerning their oversight constitutional responsibilities.The war on Coronavirus, however, is a war like no other. Here in Connecticut, the General Assembly remains in a state of suspended animation. Every so often, an annoying constitutional Cassandra will pop up to remind us that we are a constitutional republic, but constitutional antibodies in Connecticut are lacking. Our constitutions, federal and state, are still the law of the land, and even our homegrown Caligulas are not “above the law,” because we are “a nation of laws, not of men.”

These expressions are more than antiquated apothegms; they are flags of liberty that, most recently, have been waved under President Trump’s nose. However, in our present Coronavirus circumstances, no one pays much attention to constitutional Cassandras because --- do you want to die? Really, DO YOU WANT TO DIE?Every soldier who has ever entered the service of his country in a war has asked himself the very same question. And we are in a Coronavirus War, are we not? Pray it may not last as long as “The War on Drugs.” Drug dealers won that one, and Connecticut has long since entered into the gambling racket; the marijuana racket looms in our future.

Then too, in the long run, we are all dead. Even “lions of the Senate” die. The whole point of life is to live honorably. And this rather high-falutin notion of honor means what your mama said it meant: don’t cheat; don’t lie; treat others as you expect them to treat you. Bathe every day and night in modesty, and remember – as astonishing as it may seem -- sometimes your moral enemy may be right. Put on your best manners in company. “The problem with bad manners,” William F. Buckley Jr. once said, “is that they sometimes lead to murder.” Caligula forgot that admonition.

Once Coronavirus has passed, we will be able honestly and forthrightly to examine closely the following propositions, many of which seem to be supported by what little, obscure data we now have at our disposal: that death projections have been wildly exaggerated; that reports of overwhelmed hospitals were exaggerated; that death counts were likely inflated; that the real death rate is magnitudes lower than it appears; that there have been under-serviced at-risk groups affected by Coronavirus; that it is not entirely clear how well isolation works; that ventilators in some cases could be causing deaths. These are open questions because insufficient data at our disposal at the moment does not permit a “scientific” answer to the questions that torment all of us.

At some point, a vaccine will be produced that will help to quiet our sometimes irrational fears, but vaccine production lies months ahead. The question before us now is: what is more dangerous, the wolf or the lion? New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, and allied governors in his Northeast compact, cannot pinpoint a date to end their destructive business shutdown because of insufficient data. According to some reports, Cuomo has hired China-connected McKinsey & Company to produce “models on testing, infections and other key data points that will underpin decisions on how and when to reopen the region’s economy.”

If the economy in Connecticut collapses because Gov. Ned Lamont accedes to the demands of those in his newly formed consortium of Northeast governors that business destroying restrictions should remain in place for months until a vaccine is widely distributed, the effects of the resulting economic implosion will certainly be more severe than a waning Coronavirus infestation. After Connecticut has reached the apex of the Coronavirus bell curve, it is altogether possible that a continuation of the cure – a severe business shutdown occasioned by policies rooted in insufficient data – will be far worse than the disease it purports to cure.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

Hat trick

“That morning, needing a nap,

he had thrown, from the third-story balcony

of Miller's Cafe and Bakery, into the whistling

rapids and shallows

of the Ammonoosuc River, with its arrowheads and caravans of stones,

his Red Sox cap.’’

— From “A Covered Bridge in Littleton, N.,H.,’’ by Stephanie Burt, a poet and professor at Harvard

What a town is

The town hall in tiny Conway, Mass., a “Hill Town’’ that was home base for Archibald MacLeish for much of his adult life

“A town is not land, nor even landscape. A town is people living on the land. And whether it will survive or perish depends not on the land but on the people; it depends on what the people think they are….If they think of themselves as living a good and useful and satisfying life, if they put their lives first and the real estate business after, then there is nothing inevitable about the spreading ruin of the countryside.’’

— Archibald MacLeish (1892-1982), in “A Lay Sermon on {western Massachusetts) Hill Towns’’. MacLeish was a playwright, poet, government official and lawyer.

You just didn't notice it

“Viral Dance” (oil on canvas), by Gretchen Dow Simpson, Providence-based painter and photographer and long-time contributor to The New Yorker and other publications

It's safer there

“Cloud Storage” (site specific orb installation), by Sarah Bouchard, at Corey Daniels Gallery, Wells, Maine

Wells, the third-oldest town in Maine, is well known for its beaches and since the late 19th Century has been a favored summer place for people from Greater Boston and beyond. Like much of the Maine Coast, it has long attracted artists. This postcard is from 1908.

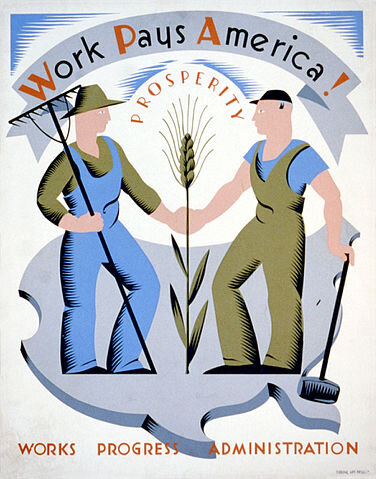

Llewellyn King: To revive America, fix the gig economy and bring back the WPA

McCoy Stadium, in Pawtucket, R.I., was a WPA project….

…and so was this field House and pump station in Scituate, Mass.

The assumption is that we’ll return to work when COVID-19 is contained, or we have adequate vaccines to deal with it.

That assumption is wrong. For many millions, maybe tens of millions, there will be no work to return to.

At root is a belief that the United States -- and much of the world -- will spring back as it did after the 2008 recession: battered but intact.

Fact is, we won’t. Many of today’s jobs won’t exist anymore. Many small businesses will simply, as the old phrase says, go to the wall. And large ones will be forced to downsize, abandoning marginal endeavors.

When we think of small businesses, we think of franchised shops or restaurants and manufacturers that sell through giants like Amazon and Walmart. But the shrinkage certainly goes further and deeper.

Retailing across the board is in trouble, from the big-box chains to the mom-and-pop clothing stores. The big retailers were reeling well before the coronavirus crisis. Neiman Marcus, an iconic luxury retailer, has filed for bankruptcy. All are hurt, some so much so – especially malls -- that they may be looking to a bleak future.

The supply chain will drive some companies out of business. Small manufacturers may find that their raw material suppliers are no longer there or that the supply chain has collapsed – for example, the clothing manufacturer who can’t get cloth from Italy, dye from Japan or fastenings from China. Over the years, supply chains have become notoriously tight as efficiency has become a business byword.

Some will adapt, some won’t be able to do so. A record 26.5 million Americans have sought unemployment benefits over the past five weeks. Official unemployment numbers have always been on the low side as there’s no way of counting those who’ve given up, those who work in the gray economy, and those who for other reasons, like fear of officialdom or lack of computer skills, haven’t applied for unemployment benefits.

To deal with this situation the government will have to be nimble and imaginative. The idea that the economy will bounce back in a classic V-shape is likely to prove illusory.

The natural response will be for more government handouts. But that won’t solve the systemic problem and will introduce a problem of its own: The dole will build up dependence.

I see two solutions, both of which will require political imagination and fortitude. First, boost the gig economy (contract and casual work) and provide gig workers with the basic structure that formal workers enjoy: Social Security, collective health insurance, unemployment insurance and workers’ compensation. The gig worker, whether cutting lawns, creating Web sites, or driving for a ride-sharing company, should be brought into the established employment fold; they’re employed but differently.

Second, a new Works Progress Administration (WPA) should be created using government and private funding and concentrating on the infrastructure. The WPA, created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1935, ended up employing 8.5 million Americans, out of a total population of 127.3 million, in projects ranging from mural painting to bridge building. Its impact for good was enormous. It fed the hungry with dignity, not the soup kitchen and bread line, and gave America a gift that has kept on giving to this day.

Jarrod Hazelton, a Rhode Island-based economist who’s researched the WPA, says the agency gave us 280,000 miles of repaired roads, almost 30,000 new and repaired bridges, 600 new airports, thousands of new schools, innumerable arts programs, and 24 million planted trees. It also enabled workers to acquire skills and escape the dead-end jobs they’d lost. It was one of the most successful public-private programs in all of history.

As the sea levels rise and the climate deteriorates, we’ll need a WPA, tied in with the Army Corps of Engineers, to help the nation flourish in the decades of challenge ahead. The original was created by FDR with a simple executive order.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His e-mail address is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

John O. Harney: 'Emergency remote'; a WPA for humanists?; defense workers kept on job

From The New England Journal of Higher Education (NEJHE), a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org):

A few items from the quarantine …

Wisdom from Zoom. COVID-19 has been a boon for Zoom and Slack (for people panicked by too many and too-slow emails). Last week, I zoomed into the Harvard Graduate School of Education (HGSE) Leadership Series conversation with Southern New Hampshire University (SNHU) President Paul LeBlanc and HGSE Dean Bridget Long. LeBlanc notes that the online programs adopted by colleges and universities everywhere in the age of COVID-19 are very different from SNHU’s renowned online platform. Unlike SNHU, most institutions have launched “emergency remote” work to help students stay on track. Despite worries in some quarters about academic quality, LeBlanc says the quick transition online is not about relaxing standards, but ratcheting up care and compassion for suddenly dislocated students. The visionary president notes that just as telemedicine is boosting access to healthcare during the pandemic, online learning could boost access to education.

Among other observations, LeBlanc explains that “time” is the enemy for traditional students who have to pause classes when, for example, their child gets sick. If they are students in a well-designed online program, they can avoid delays in their education despite personal disruptions. He also believes students will want to come rushing back to campuses after COVID-19 dissipates, but with the recession, he wonders if they’ll be able to afford it. Oh and, by the way, LeBlanc ventures that it’s unlikely campuses will open in the fall without a lot more coronavirus testing.

Summer learning loss becomes COVID learning loss. That’s the concern of people like Chris Minnich, CEO of the nonprofit assessment and research organization NWEA, founded in Oregon as the Northwest Evaluation Association. The group predicts that when students finally head back to school next fall (presumably), they are likely to retain about 70% of this year’s gains in reading, compared with a typical school year, and less than 50% in math. The concern over achievement milestones reminds me of the fretting over SATs and ACTs as well as high-stakes high school tests, being postponed. Merrie Najimy, president of the Massachusetts Teachers Association, notes that the pause “provides all of us with an opportunity to rethink the testing requirements.”

Another WPA for Humanists? Modern Language Association Executive Director Paula M. Krebs recently reminded readers that during the Great Depression, the Works Progress Administration, though commonly associated with building roads and bridges, also employed writers, researchers, historians, artists, musicians, actors and other cultural figures. Given COVID-19, “this moment calls for a new WPA that employs those with humanities expertise in partnership with scientists, health-care practitioners, social scientists, and business, to help shape the public understanding of the changes our collective culture is undergoing,” writes Krebs.

Research could help right now. News of the University of New Hampshire garnering $6 million from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to build and test an instrument to monitor space weather reminded me of when research prowess was recognized as a salient feature of New England’s higher education leadership. That was mostly before jabs like the “wastebook” from then-U.S. Sen. Jeff Flake (R-Ariz.) ridiculed any spending on research that didn’t translate directly to commercial use. But R&D work can go from suspect to practical very quickly. For example, consider research at the University of Maine’s Lobster Institute trying to see if an extract from lobsters might work to treat COVID-19. Or consider that 15 years ago, the Summer 2004 edition of Connection (now NEJHE) ran a short piece on an unpopular research lab being built by Boston University and the federal government in Boston’s densely settled South End to study dangerous germs like Ebola. The region was also a pioneer in community relations, and the neighborhood was tense about the dangers in its midst to say the least. But today, that lab’s role in the search for a coronavirus vaccine is much less controversial.

Advice for grads in a difficult year. This journal is inviting economists and other experts on “employability” to weigh in on how COVID-19 will affect 2020’s college grads in New England. What does it mean for the college-educated labor market that has been another New England economic advantage historically?

Bath Iron Works will keep its employees at work.

Defense rests? One New England industry that is not shutting down due to COVID-19 is the defense industry. In Maine, General Dynamics Bath Iron Works ordered face masks for employees and expanded its sick time policy, but union leaders say the company isn’t doing enough to address coronavirus. More than 70 Maine lawmakers recently asked the company to consider closing temporarily to protect workers from the spread of the virus. But the Defense Department would have to instruct the shipyard to close, and Pentagon officials say it is a “Critical Infrastructure Industry.” About 17,000 people who work at the General Dynamics Electric Boat’s shipyards in Quonset Point, R.I., and Groton, Conn., are in the same boat, so to speak. They too have been told to keep reporting to work. In New London, a letter in The Day pleaded with Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont to shut down Electric Boat. Critical Infrastructure Industry. If only attack subs on schedule could help beat an “invisible enemy.”

John O. Harney is executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

Below, “Wong’s Pot with Old Flowers,” by Montserrat College Prof. Timothy Harney.

'Called out the best energies'

“Landing of the Pilgrims,’’ by Michele Felice Cornè, circa 1805, displayed in the White House

Lowell, Mass., textile mills in 1850.

“{The Pilgrim Fathers} fell upon an ungenial climate, where there were nine months of winter and three months of cold weather, and that called out the best energies of the men, and of the women too, to get a mere subsistence out of the soil, with such a climate. In their efforts to do that they cultivated industry and frugality at the same time which is the real foundation of the greatness of the Pilgrims.’’

— Ulysses S. Grant, in a speech at a New England Society dinner in 1880

Getting away before the summer people arrive, if they do this year

“Leaving the Tide” (oil on canvas), by C.J. Lori, at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, via its online gallery

N.E. virus response: Beth Israel making swabs; Home Base director takes role; Dartmouth working on better test

— Photo by Raimond Spekking

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

As our region and our nation continue to grapple with the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) pandemic, The New England Council is using our blog as a platform to highlight some of the incredible work our members have undertaken to respond to the outbreak. Each day, we’ll post a round-up of updates on some of the initiatives underway among Council members throughout the region. We are also sharing these updates via our social media, and encourage our members to share with us any information on their efforts so that we can be sure to include them in these daily round-ups.

You can find all the Council’s information and resources related to the crisis in the special COVID-19 section of our website. This includes our COVID-19 Virtual Events Calendar, which provides information on upcoming COVID-19 Congressional town halls and webinars presented by NEC members, as well as our newly-released Federal Agency COVID-19 Guidance for Businesses page.

Here is the April 21 roundup:

Medical Response

Beth Israel Producing Testing Swabs to Combat Shortage – Faced with a dwindling supply of testing materials, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) has begun producing their own testing swabs in collaboration with local academics and manufacturers. The new swabs are already being used to test potential COVID-19 patients and will begin production on a larger scale soon. Read more from WBUR.

Home Base’s Gen. Jack Hammond Tapped to Lead Boston Hope Medical Center – General Jack Hammond, director of the Massachusetts General Hospital and Boston Red Sox Home Base Program, has been chosen by Gov. Charlie Baker (R-MA) to serve as co-medical and operations director at Boston Hope Medical Center. Gen. Hammond will draw on both his personal experience serving in the military and in his role at Home Base to work with state and local officials to coordinate care for the unsheltered and those in post-acute care. Read more in The Boston Globe and the press release.

Dartmouth College Researchers Developing Improved Test – Researchers at Dartmouth College are working to create a new, improved test for COVID-19. The lab has partnered with a California biotech company to make the test more reliable and quicker to produce results. The test awaits FDA approval as it is being compared to the test currently being used in the United States. Read more from The New Hampshire Business Review

Economic/Business Continuity Response

Worcester State University Receives $484,000 Grant to Improve Remote Learning – To support its transition to remote learning, Worcester State University (WSU) has received over $484,000 in grants from a Boston venture philanthropy firm. The funds will be used to cover a variety of expenses, such as laptops and a university-wide texting system to remind students of upcoming deadlines. The measures are designed to especially help first-generation students, a demographic already more likely to drop out of school. The Worcester Business Journal has more.

Community Response

City of Providence Buys 34,000 Masks for Frontline Workers – The City of Providence has partnered with its firefighters union to purchase 34,000 N95 masks for first responders directly exposed to the virus. Masks, along with other protective equipment such as gloves, will be distributed to responders and other essential personnel who require them. Read more from WPRI.

UnitedHealth Announces $5 Million to Support Healthcare Workers – UnitedHealth Group, as part of its initial $60 million commitment to combating the coronavirus pandemic, has announced a $5 million initiative to support the healthcare workforce. Specifically, the funds will be directed toward efforts to procure more personal protective equipment (PPE) and to provide mental health support to those working directly with COVID-19 patients. Read the press release here.

Stay tuned for more updates each day, and follow us on Twitter for more frequent updates on how Council members are contributing to the response to this global health crisis.

Proudly sing of the 'Willimantick'

The Willimantic River flows past the site of the old American Thread Company mill, in Willimantic, Conn.

“We dare not be original; our American Pine must be cut to the trim pattern of the English Yew, though the Pine bleed at every clip. This poet tunes his lyre at the harp of Goethe, Milton, Pope, or Tennyson. His songs might better be sung on the Rhine than the Kennebec. They are not American in form or feeling; they have not the breath of our air; the smell of our ground is not in them. Hence our poet seems cold and poor. He loves the old mythology; talks about Pluto—the Greek devil,—— the Fates and Furies—witches of old time in Greece,—-but would blush to use our mythology, or breathe the name in verse of our Devil, or our own Witches, lest he should be thought to believe what he wrote. The mother and sisters, who with many a pinch and pain sent the hopeful boy to college, must turn over the Classical Dictionary before they can find out what the youth would be at in his rhymes. Our Poet is not deep enough to see that Aphrodite came from the ordinary waters, that Homer only hitched into rhythm and furnished the accomplishment of verse to street talk, nursery tales, and old men’s gossip, in the Ionian towns; he thinks what is common is unclean. So he sings of Corinth and Athens, which he never saw, but has not a word to say of Boston, and Fall River, and Baltimore, and New York, which are just as meet for song. He raves of Thermopylae and

Marathon, with never a word for Lexington and Bunker Hill, for Cowpens, and Lundy’s Lane, and Bemis’s Heights. He loves to tell of “smooth sliding Mincius, crowned with vocal reeds,” yet sings not of the Petapsco, the Susquehannah, the Aroostook, and the Willimantick. He prates of the narcissus, and the daisy, never of American dandelions and bue-eyed grass; he dwells on the lark and the nightingale, but has not a thought for the brown thrasher and the bobolink, who every morning in June rain down such showers of melody on his affected head. What a lesson Burns teaches us addressing his “rough bur thistle,” his daisy, “wee crimson tippit thing,” and finding marvellous poetry in the mouse whose nest his plough turned over! Nay, how beautifully has even our sweet Poet sung of our own Green river, our waterfowl, of the blue and fringed gentian, the glory of autumnal days.”

― Massachusetts Quarterly Review, 1849

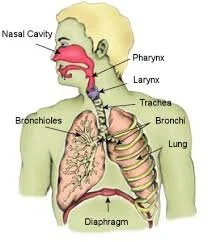

Melissa Bailey: Even in New England, global warming putting physicians in hot seat

Person being cooled with water spray, one of the treatments of heat stroke in Iraq in 1943

BOSTON

A 4-year-old girl was rushed to the emergency room three times in one week for asthma attacks.

An elderly man, who’d been holed up in a top-floor apartment with no air conditioning during a heat wave, showed up at a hospital with a temperature of 106 degrees.

A 27-year-old man arrived in the ER with trouble breathing ― and learned he had end-stage kidney disease, linked to his time as a sugar cane farmer in the sweltering fields of El Salvador.

These patients, whose cases were recounted by doctors, all arrived at Boston-area hospitals in recent years. While the coronavirus pandemic is at the forefront of doctor-patient conversations these days, there’s another factor continuing to shape patients’ health: climate change.

Global warming is often associated with dramatic effects such as hurricanes, fires and floods, but patients’ health issues represent the subtler ways that climate change is showing up in the exam room, according to the physicians who treated them.

Dr. Renee Salas, an emergency physician at Massachusetts General Hospital, said she was working a night shift when the 4-year-old arrived the third time, struggling to breathe. The girl’s mother felt helpless that she couldn’t protect her daughter, whose condition was so severe that she had to be admitted to the hospital, Salas recalled.

She found time to talk with the patient’s mother about the larger factors at play: The girl’s asthma appeared to be triggered by a high pollen count that week. And pollen levels are rising in general because of higher levels of carbon dioxide, which she explained is linked to human-caused climate change.

Salas, a national expert on climate change and health, is a driving force behind an initiative to spur clinicians and hospitals to take a more active role in responding to climate change. The effort launched in Boston in February, and organizers aim to spread it to seven U.S. cities and Australia over the next year and a half.

Although there is scientific consensus on a mounting climate crisis, some people reject the idea that rising temperatures are linked to human activity. The controversy can make doctors hesitant to bring it up.

Even at the climate change discussion in Boston, one panelist suggested the topic may be too political for the exam room. Dr. Nicholas Hill, head of the Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Division at Tufts Medical Center of Medicine, recalled treating a “cute little old lady” in her 80s who likes Fox News, a favorite of climate change doubters. With someone like her, talking about climate change may hurt the doctor-patient relationship, he suggested. “How far do you go in advocating with patients?”

Doctors and nurses are well suited to influence public opinion because the public considers them “trusted messengers,” said Dr. Aaron Bernstein, who co-organized the Boston event and co-directs the Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment at Harvard’s school of public health. People have confidence they will provide reliable information when they make highly personal and even life-or-death decisions.

Bernstein and others are urging clinicians to exert their influence by contacting elected officials, serving as expert witnesses, attending public protests and reducing their hospital’s carbon emissions. They’re also encouraging them to raise the topic with patients.

Dr. Mary Rice, a pulmonologist who researches air quality at Beth-Israel Deaconess Medical Center here, recognized that in a 20-minute clinic visit, doctors don’t have much time to spare.

But “I think we should be talking to our patients about this,” she said. “Just inserting that sentence, that one of the reasons your allergies are getting worse is that the allergy season is worse than it used to be, and that’s because of climate change.”

Salas, who has been a doctor for seven years, said she had little awareness of the topic until she heard climate change described as the “greatest public health emergency of our time” during a 2013 conference.

“I was dumbfounded about why I hadn’t heard of this, climate change harming health,” she said. “I clearly saw this is going to make my job harder” in emergency medicine.

Now, Salas said, she sees ample evidence of climate change in the exam room. After Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico, for instance, a woman seeking refuge in Boston showed up with a bag of empty pill bottles and thrust it at Salas, asking for refills, she recalled. The patient hadn’t had her medications replenished for weeks because of the storm, whose destructive power was likely intensified by climate change, according to scientists.

Climate change presents many threats across the country, Salas noted: Heat stress can exacerbate mental illness, prompt more aggression and violence, and hurt pregnancy outcomes. Air pollution worsens respiratory problems. High temperatures can weaken the effectiveness of medications such as albuterol inhalers and EpiPens.

The delivery of health care is also being disrupted. Disasters like Hurricane Maria have caused shortages in basic medical supplies. Last November, nearly 250 California hospitals lost power in planned outages to prevent wildfires. Natural disasters can interrupt the treatment of cancer, leading to earlier death.

Even a short heat wave can upend routine care: On a hot day last summer, for instance, power failed at Mount Auburn Hospital in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and firefighters had to move patients down from the top floor because it was too hot, Salas said.

Other effects of climate change vary by region. Salas and others urged clinicians to look out for unexpected conditions, such as Lyme disease and West Nile virus, that are spreading to new territory as temperatures rise.

In California, where wildfires have become a fact of life, researchers are scrambling to document the ways smoke inhalation is affecting patients’ health, including higher rates of acute bronchitis, pneumonia, heart attacks, strokes, irregular heartbeats and premature births.

Researchers have shown that heavy exposure to wildfire smoke can change the DNA of immune cells, but they’re uncertain whether that will have a long-term impact, said Dr. Mary Prunicki, director of air pollution and health research at Stanford University’s center for allergy and asthma research.

“It causes a lot of anxiety,” Prunicki said. “Everyone feels helpless because we simply don’t know — we’re not able to give concrete facts back to the patient.”

In Denver, Dr. Jay Lemery, a professor of emergency medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, said he’s seeing how people with chronic illnesses like diabetes and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease suffer more with extreme heat.

There’s no medical code for “hottest day of the year,” Lemery said, “but we see it; it’s real. Those people are struggling in a way that they wouldn’t” because of climbing temperatures, he said. “Climate change right now is a threat multiplier — it makes bad things worse.”

Lemery and Prunicki are among the doctors planning to organize events in their respective regions to educate peers about climate-related threats to patients’ health, through the Climate Crisis and Clinical Practice Initiative, the effort launched in Boston in February.

“There are so many really brilliant, smart clinicians who have no clue” about the link between climate change and human health, said Lemery, who has also written a textbook and started a fellowship on the topic.

Salas said she sometimes hears pushback that climate change is too political for the exam room. But despite misleading information from the fossil fuel industry, she said, the science is clear. Based on the evidence, 97% of climate scientists agree that humans are causing global warming.

Salas said that, as she sat with the distraught mother of the 4-year-old girl with asthma in Boston, her decision to broach the topic was easy.

“Of course I have to talk to her about climate change,” Salas said, “because it’s impairing her ability to care for her daughter.”

Melissa Bailey is a Kaiser Health News journalist.

Melissa Bailey: @mmbaily