About the way MBTA stations look now

“Interlude’’ (composite photograph on aluminum), by Steven Bennett, at Galatea Fine Art, Boston. The gallery will be closed through April 29 because of the pandemic.

Jill Richardson: Stay at home and stay angry

Via OtherWords.org

Social distancing is hard, and it’s not fun.

I don’t question that we are doing what is necessary. Until better testing, treatment, and prevention are available, it is. But quarantining us in our homes separates us at a time when we need connection.

And you know what? It’s okay to feel angry about that. It’s important to remember we’re doing this in part because the people at the top screwed up.

Trump fired the pandemic response team two years ago, even though Obama’s people warned them that we needed to work on preparedness for exactly this in 2016. Unsurprisingly, a government simulation exercise just last year found we were not prepared for a pandemic.

Later on, even after the disease had come to the U.S., infectious disease experts in Washington State had to fight the federal government for the right to test for the coronavirus.

It gets worse.

Now we know that North Carolina Sen. Richard Burr was taking the warnings seriously weeks before any real action was taken — and all he did was sell off a bunch of stock, while telling the public everything was fine. Meanwhile, Trump didn’t want a lot of testing, because he wanted to keep the number of confirmed cases low to aid his re-election.

The people we trusted to keep us safe didn’t do that. Now the entire economy’s turned upside down, people are dying, and we’re all cooped up at home.

It sucks. We should be angry.

I’m young enough that I probably don’t have to worry much about the likelihood of a serious case if I get sick. But I’m staying home, because I don’t want to get it and accidentally spread it to someone more vulnerable than myself.

I’m also aware of the sacrifice that many of us are making for the sake of others. Some lost their jobs, while others put themselves at risk working outside the home because they can’t afford not to — or, in the case of health care workers, because they’re badly needed.

Entire families are cooped up together and I’ve heard jokes that divorce lawyers will get plenty of business after this. Parents are posting memes about how much they appreciate teachers now that they are stuck with their kids all day. I’m entirely alone besides a cat.

I worry about the college seniors graduating this year and trying to find a job. What about people prone to anxiety and depression? How much will this exacerbate domestic abuse? What about people in jails, prisons, and detention centers?

Our society is deeply unequal. So while the virus itself doesn’t discriminate, this bigger crisis will hit people unequally. Some don’t have health insurance. Some are undocumented. Some are more susceptible to dying from the disease.

The people in power who screwed up are wealthy enough that they can work from home, maintain their income, and access affordable health care. Others will feel the full brunt of this, not them. It’s not fair.

I’m supportive of doing all we can to prevent the virus’s spread and to protect vulnerable people, but anger at the people whose incompetence put us in this position is justified. We deserve better.

Jill Richardson, a sociologist, is an OtherWords.org columnist.

(Mostly) nonelectronic home entertainment

Victorian pump organ

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

‘One of my innumerable regrets is not learning how to play a musical instrument. When I was growing up, many kids in our town took outside lessons, or were taught by their parents, to play the piano. Both my parents played, though my father was better. With a little more practice, perhaps in a crunch he could have played in a cocktail lounge. We had a borrowed baby grand for years. My father also had a ukulele, which he’d play on the weekends, often with a cigarette in his mouth. It’s a strong memory I have of that kindly but rather cryptic man.

We even had an old pump organ, bought in a sort of junk and antiques store in Marshfield, Mass., called Reed’s Ark. My father would play songs from the turn of the 20th Century on it.

Marshfield’s Wickedlocal noted of Reed’s Ark, a dusty firetrap in which you entered the 19th Century:

“Some 50 years ago, there was a fascinating store near the middle of Marshfield. You could prowl among antique junk or books or tools and occasionally find something worth actually buying.’’

Playing musical instruments and reading were primary middle-class home attractions, and, unlike with much of our electronic life now, active, not passive activities. (My God, we got a lot of magazines! Maybe eight a week, all jammed with ads.)

I’m thinking of this these days because we’re all spending a lot more time at home, whether we want to or not.

In the Brant Rock section of Marshfield.

The town is named for its many salt marshes. There are three rivers: the North, along the town’s northern border, the South, which branches off at the mouth of the North River and heads south through the town, and the Green Harbor River, which flows just west of Brant Rock and Green Harbor Point at the south end of town.

Marshfield is named for the many salt marshes which border the salt and brackish borders of the town. There are three rivers: the North (along the northern border of the town), South (which branches at the mouth of the North River and heads south through the town) and the Green Harbor River (which flows just west of Brant Rock and Green Harbor Point at the south of town).

Chris Powell: Yes, anti-COVID-19 campaign could do more damage than the virus

Plague doctor in 1656

As Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont and other governors curtail more commerce, industry, employment and ordinary life in the name of containing the new virus sweeping the world, people are starting to question whether the precautions are going too far. Is containing the virus worth crippling the economy, bankrupting so many businesses, throwing millions out of work and pushing their households into insolvency, destroying retirement savings, and exploding the national debt?

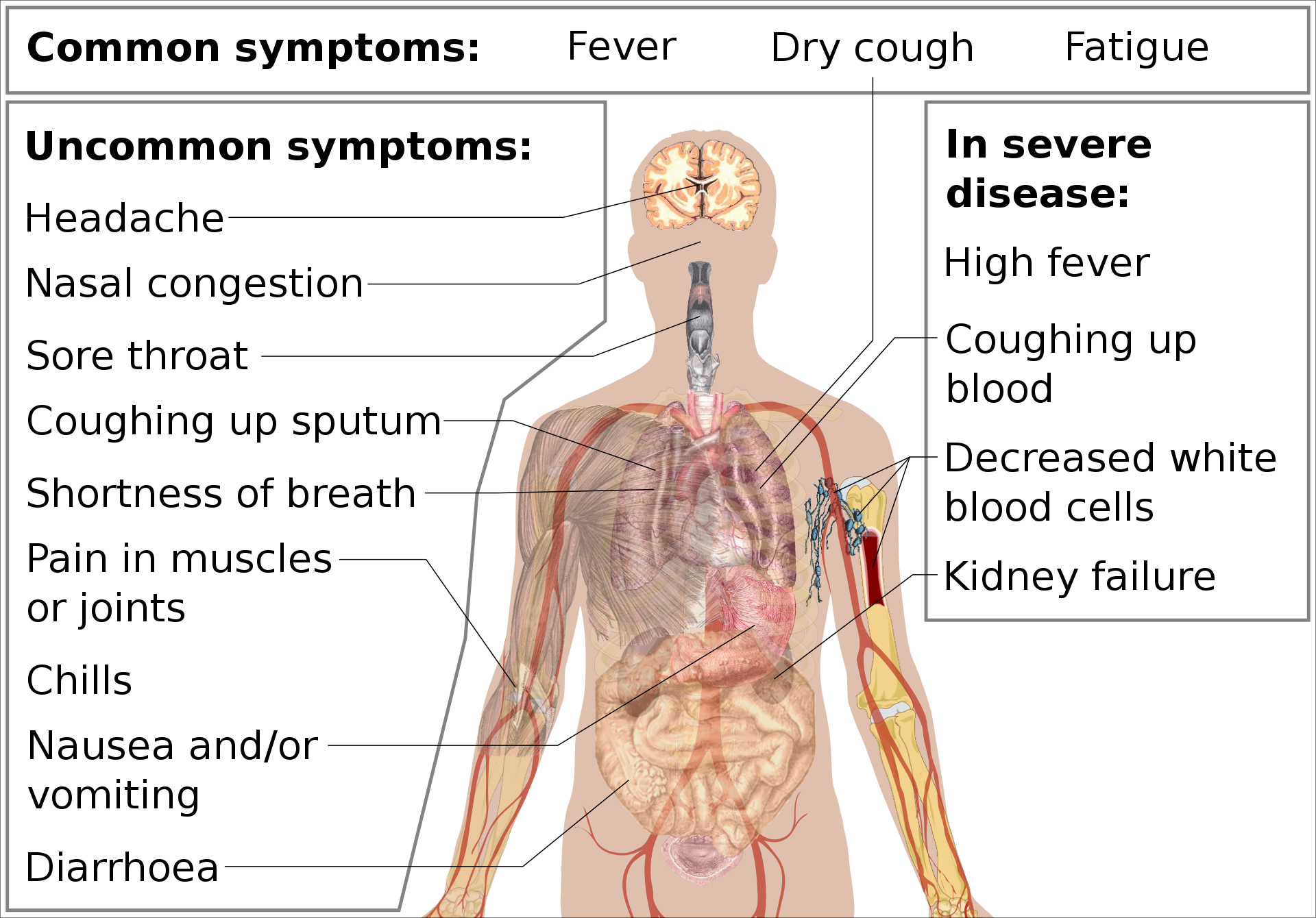

The official response is making the virus sound like the plague that killed half of Europe in the 1300s. But many people sense that it may not be that bad, may be no worse than ordinary influenza, which kills tens of thousands of people in the United States every year without setting off any alarm. Indeed, ordinary flu in Connecticut this year already had hospitalized more than 1,300 people and killed more than 60 before the new virus infected its first hundred people and killed anyone in the state. The state Department of Public Health noticed the flu's toll but only in a statistical sense. Except for the families of those who died, nobody else seems to have noticed, though "social distancing" a few months ago might have prevented many of those deaths.

Few notice how traffic fatalities add up either -- more than 35,000 every year in the United States, even as most could be prevented by "lockdowns" like those now being imposed because of the new virus.

Despite all the hysteria, financial loss and inconvenience generated by closing orders, most people diagnosed with the new virus find it anticlimactic. That is, for most a positive test for the virus prompts no hospitalization or special medical intervention at all. Instead most people are just told to go home, get well soon, and call back if they don't, just as they would be told upon diagnosis for the flu or a bad cold. Sure enough, they go home and most get well soon.

Doctors and governors warn that for every diagnosis with the new virus there may be a hundred undiagnosed people carrying it but not showing symptoms, and even the asymptomatic may infect others. Or the asymptomatic may not infect anyone and may never suffer any symptoms at all. Indeed, last week a Nobel prize-winning Israeli scientist speculated that half the population may be naturally immune to the new virus, and Chinese research has suggested that blood type may correlate with susceptibility. So while the mere number of infections may sound scary, it is not so important.

What may be most important is the percentage of people infected who die or require hospitalization. As of March 22 in Connecticut, the fatality rate from infections with the new virus was just 2½ percent and the hospitalization rate about 18 percent. Frail elderly people were most at risk of dying in Connecticut and most deaths elsewhere from the disease have involved either the frail elderly or those with already weakened immune systems. Hard-hit Italy reported last week that 99 percent of its fatalities were from these high-risk groups.

Of course, if infection spreads widely enough, even an 18 percent hospitalization rate would overwhelm the medical system. So widespread testing and quarantining as necessary, as South Korea has done, might be the best response. A government more devoted to public health generally than to fantastically expensive and stupid imperial wars might help too. But since, as flu and traffic fatalities show, life is always a judgment call about risk, and since it is known who is most vulnerable to the new virus, why not just isolate them rather than everyone else? For as the self-inflicted economic damage becomes catastrophic, the cure may be worse than the disease.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, vin Manchester, Conn.

N.E. Council asks for federal aid for colleges and universities

Thompson Hall, at the University of New Hampshire, in Durham

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

BOSTON

“The New England Council is calling on Congress to provide relief to colleges and universities in light of the COVID-19 public health crisis that has forced them to close their campuses to students. In a letter sent to each New England senator, as well as the Senate leadership, on March 20, the council stressed the important role our region’s higher-education institutions play in the region’s economy, and outlined the devastating impact the crisis is having on the schools themselves, as well as on their students directly.

The letter outlined several areas where the federal government could provide support to colleges and universities, including:

Financial support for students and institutions

Housing and meal assistance

Technology for remote learning

Title IV Relief’’

Do what you have to do

Cutler Harbor. The town, in extreme eastern Maine, is in a beautiful if harsh region. Fishing, mostly lobstering, is still very important. In recent years, a few people “from away” have built summer places along the shore. The water will quickly get your attention if you try to swim in. The Gulf of Maine is warming these days, but not so much you want to dive in on one of far Downeast Maine’s very few hot days.

“Do you know how I got through the change of life? I went out and built a camp from driftwood on the outer shores of Cutler (Maine}.

— From Ruth Farris’s weekly column in the Machias Valley (Maine) News Observer in 1994.

— Photo by Walter Siegmund

'If design govern...'

I found a dimpled spider, fat and white,

On a white heal-all, holding up a moth

Like a white piece of rigid satin cloth--

Assorted characters of death and blight

Mixed ready to begin the morning right,

Like the ingredients of a witches' broth--

A snow-drop spider, a flower like a froth,

And dead wings carried like a paper kite.

What had that flower to do with being white,

The wayside blue and innocent heal-all?

What brought the kindred spider to that height,

Then steered the white moth thither in the night?

What but design of darkness to appall?--

If design govern in a thing so small.

“Design,’’ by Robert Frost (1874-1963)

David Warsh: With economic depression coming on, 'I believe in news'

Police attack demonstrating unemployed workers in Tompkins Park, in New York, in 1874, during the deep depression then.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The European and North American economies are entering a period of depression that already resembles the Great Depression more than any other experience in living memory.

This depression won’t last a decade; perhaps it will last no more than six or nine months. It will not end in a global war, though it certainly has exacerbated international relations. But lock-down policies to cope with the coronavirus pandemic already in place probably insure a couple of quarters that will set records for unemployment, bankruptcies and many more painful deprivations.

Now these policies are about to become the center of a political argument, the most consequential of the Trump presidency — 21st Century equivalent of the Battle of Gettysburg. That’s a strong analogy, I know. But compared to the earlier clashes of the Trump presidency – the Russia investigation, the impeachment trial – the continuing engagement over his handling of the pandemic will eventually deliver a climax worthy of the comparison. It will be radical opportunism vs. the pursuit of knowledge: Between now and Nov. 3, Trump will try to permanently divide the nation. It is not clear which side will win.

First things first. What happened in money markets over the course of the last few days bore little resemblance to the desperate events of September 2008. The coronavirus crisis hasn’t produced a systemic banking panic like the worldwide financial meltdown that threatened then. This time the Federal Reserve System has addressed only a series of alarms in various debt markets in which the underlying concern was about impending business losses. Former Federal Reserve Chairs Janet Yellen and Ben Bernanke described the Fed’s actions and their limits in a bracing article March 19 in the Financial Times.

However, the Fed and other policymakers face an even bigger challenge. They must ensure that the economic damage from the pandemic is not long-lasting. Ideally, when the effects of the virus pass, people will go back to work, to school, to the shops, and the economy will return to normal. In that scenario, the recession may be deep, but at least it will have been short.

But that isn’t the only possible scenario: if critical economic relationships are disrupted by months of low activity, the economy may take a very long time to recover. Otherwise healthy businesses might have to shut down due to several months of low revenues. Once they have declared bankruptcy, re-establishing credit and returning to normal operations may not be easy. If a financially strapped firm lays off — or declines to hire — workers, it will lose the experienced employees needed to resume normal business. Or a family temporarily without income might default on its mortgage, losing its home.

On March 16, former Fed Governor Kevin Warsh (no relation of mine) criticized the “2008-style barrages” of Fed measures the day before, including cutting its short-term policy interest rate to near zero. He called for the creation of a Government Backed Credit Facility (GBCF), a huge loan facility, to be administered by 12 regional Federal Reserve banks, backstopped by the Treasury, to lend to companies in danger of going broke who are willing to pledge assets in return for the money.

Meanwhile, Congress publicly debated Sen. Mitt Romney (R-Utah) and Treasury Secretary Steven Munchin’s plan to write checks to help individuals get through their hard times. Behind the scenes, the rest of Munchin’s plan: $50 billion for the airlines, $150 billion more for other troubled businesses, and $300 billion for small- business loans.

That was before governors began shutting down their states’ economies with orders of various degrees of severity – Ohio, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Texas, California, Illinois and New York.

The backlash began on March 17, when Stat, a widely respected, Boston-based online news organization, published “A Fiasco in the Making?’’, by John P.A. Ioannides, a professor of statistics and epidemiology at Stanford University. As a top expert on statistical sampling, Ioannides complained of the dearth of broad samples of the rate of infection and death. But based on the limited evidence from the one thoroughly studied sample – the 700 passengers of the Diamond Princess cruise ship, of whom seven persons have died – the “kill rate” of Covid-19 might be somewhere between 0.05 percent and 1 percent of those infected, or about the same as regular flu.

If that were determined by better sampling to be the case generally, Ioannides argued, then extreme measures taken could have perverse effects. Or as my friend Lou Fedorkow put it in calling the article to my attention, the United States, having reacted to the 9/11 attacks by going to war in Afghanistan and Iraq, today may be responding to the COVID-19 virus pandemic by going to war with itself.

Also on March 17, the editorial board of The Wall Street Journal, confusing financial-market distress with panic about the economy itself, began a series of editorials, which, in the course of the week, worked their way through to the conviction that the lock-downs were disastrous and needed to be undone. In “Financing an Economic Shutdown, ‘‘ they complained that “Some state and federal leaders [were] shutting down the economy without a plan to finance it while everyone stays home.” They lauded former Governor Warsh’s plan.

The next day, “The Fiscal Stimulus Panic’’ advocated Food Stamps and expanded jobless insurance instead of those checks, which were said to be motivated by a “Keynesian illusion.” On March 19 came “Economic Rout Accelerates’’:

You don’t calm a panic by floating ill-considered trial balloons or chanting “go big” as an illusion of proper and thoughtful action. Markets are panicked in part because they sense that our political leaders are more panicked than the public is.

You calm a panic first by looking like you know what you’re doing. You explain that this is a liquidity problem caused by an extraordinary precaution against a virus that is closing down businesses. The government needs to act to prevent the liquidity panic from becoming a solvency rout that becomes a banking crisis. And it needs to act fast.

By March 20, the editorialists had recognized the likelihood of depression and were “Rethinking the Coronavirus Shutdown’’.

If this government-ordered shutdown continues for much more than another week or two, the human cost of job losses and bankruptcies will exceed what most Americans imagine. This won’t be popular to read in some quarters, but federal and state officials need to start adjusting their anti-virus strategy now to avoid an economic recession that will dwarf the harm from 2008-2009.

And on March 21, in “Leaderless on the Economy,’’ repeating its mantra, “Government needs to address the liquidity crisis it has created for private business, or this will soon become a solvency panic as companies default on debt and fail, which will turn into a banking crisis.” Criticizing “The Extreme State Lockdowns’’ in New York and California as “unsustainable,” they concluded,

Americans may simply decide to ignore the orders after a time. Absent a more thorough explanation of costs and benefits, we doubt these extreme measures will be sustainable for long as the public begins to chafe at the limits and sees the economic consequences.

As usual, it was left to WSJ columnist Holman Jenkins Jr., the sharpest member of the Editorial Board, to draw out the implications. On March 21, in “What Victory Looks Like in the Coronavirus War,’’ he argued for taking what had been the British approach: isolate those who test positive for the disease and encourage everybody else to take care with their sneezes, hand-washing, etc. He continued,

Inconveniently for my argument, the U.K., a pioneer of such thinking, is now shifting to an accept-a-depression-and-wait-for-a-vaccine approach. The medical experts and their priorities are hard to resist. Resisting their wisdom doesn’t come naturally in such a situation.

Happily, I have confidence in the American people to let their leaders know when the mandatory shutdowns no longer are doing it for them. Strange to say, I have confidence in our political class to sense where the social fulcrum lies. A reader emails that Donald Trump could declare victory at the end of 15 days, claim the blow on the health-care system has been cushioned, and urge Americans, super-cautiously, to resume normal life. This idea sounds better than waiting for spontaneous mass defections from the ambitions of the epidemiologists to undermine the authority of the government.

Meanwhile, Bret Stephens, who left the WSJ Editorial Board in 2017 for a column in The New York Times because he so objected to the former’s embrace of Trump, made a similar point March 22 in “It’s Dangerous to be Ruled by Fear’’:

Sooner or later, people will figure out that it is not sustainable to keep tens of millions of people in lockdown; or use population-wide edicts rather than measures designed to protect the most vulnerable; or expect the federal government to keep a $21 trillion economy afloat; or throw millions of people out of work and ask them to subsist on a $1,200 check.

And as if to put a human face on the opposition to current policy, the news pages of the WSJ, a preserve of traditional news values, discovered and described entrepreneur Elon Musk’s holdout for days against suspending car production in his Fremont, Calif., “The coronavirus panic is dumb,” Musk argues.

How do these policy decisions get made? I don’t know a better answer – a glimpse of an answer – than “The Humanitarian Revolution” chapter in Steven Pinker’s The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (Viking Penguin, 2012). The origins of today’s policy of lockdown is more a question of culture evolving than the existence of an epidemiological “deep state.” Obviously the costs and benefits of various approaches to managing the epidemic should be regularly examined, Bayesian-fashion – without ridicule. As for the covid-19 pandemic, I come down on the side of the Rev. Thomas Bayes (1701-1761), who argued more than 250 years ago that, statistically, we learn from experience; specifically, that by updating our initial beliefs with carefully obtained new information, we improve our beliefs about the prospects of whatever we undertake to know. In other words, I believe in news.

So get ready for a ferocious debate about the measures adopted. It seems certain to grow in bitterness and carry on down to Election Day. The situation is encapsulated in this 40-second viral clip from a presidential news conference. Watch it twice, the first time for epidemiologist Anthony Fauci’s reaction to what the president is saying, the second time to see the look Fauci eventually receives from Trump. That was the moment in which the climactic battle of Trump’s presidency began.

David Warsh, an economic historian and veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran.

After it hits us

“Planet III version 1)” (mixed media on paper with soil from San Pedro de Atacama River and charcoal from the community of Coyo), by Ponnapa Prakkamakul, in a show opening April 6 at the Augusta Savage Gallery, Amherst, Mass., pandemic permitting. In this show the painter and landscape architect explores sites and environments as an immigrant.

The rather ugly but well-stocked Robert Frost Library at Amherst College. The great poet (1874-1963) taught at the elite college off and on for 40 years. Sometimes he was just present and available to talk.

‘How do you know?’

Astronomical vernal equinox seen from the site of Pizzo Vento at Fondachelli Fantina, Sicily

How do you know that the pilgrim track

Along the belting zodiac

Swept by the sun in his seeming rounds

Is traced by now to the Fishes’ bounds

And into the Ram, when weeks of cloud

Have wrapt the sky in a clammy shroud,

And never as yet a tinct of spring

Has shown in the Earth’s apparelling;

O vespering bird, how do you know,

How do you know?

How do you know, deep underground,

Hid in your bed from sight and sound,

Without a turn in temperature,

With weather life can scarce endure,

That light has won a fraction’s strength,

And day put on some moments’ length,

Whereof in merest rote will come,

Weeks hence, mild airs that do not numb;

O crocus root, how do you know,

How do you know?

“The Year’s Awakening,’’ by Thomas Hardy (1840-1928)

Grace Kelly: Get outdoors as much as possible in these fraught times

Via ecoRI News (ecori.org)

WRENTHAM, Mass.

The local wildlife hosted an opera March 14 as we scaled “Joe’s Rock here.”

{For information on the Joe’s Rock Trail in Wrentham, please hit this link. }

As my boyfriend and his friend climbed the rock face — our local climbing gym was closed because of the coronavirus — I traipsed through the underbrush to get a closer listen to the wildlife singing their songs, and to take my mind off the pandemic that is gripping world.

We’re not the only ones turning to nature and the outdoors for a respite from the news.

“I walk a lot and I’ve noticed the places I walk have a lot more people and the parking lots are full,” said Rupert Friday, executive director of the Rhode Island Land Trust Council. “And I was talking to our board president, Barbara Rich, and she said all the places she normally walks, she drives by the parking lots and they are totally full, and I heard the same thing from a former board member who lives in Little Compton who said the places she normally walks are so busy that she is going to new places that are less well known.”

It’s not really a surprise. Social distancing and working from home, along with shuttered gathering spaces such as libraries, cafés, movie theaters, and restaurants, create loneliness and cabin fever. When there’s a virtual lockdown, the great outdoors beckons.

That’s a good thing, too. According to a 2011 study by Japanese researchers, participants who spent more time in natural settings exhibited lower levels of stress hormones than those in the urban control group.

For Margie Butler, a Providence resident, going outside has been a huge source of relief and calm during these troubled times

“I’ve been walking morning and evening now for well over a week during our COVID-19 times,” the resident of the Fox Point neighborhood said. “I admit to being a walker even in normal times, but something feels different now. When all else in our lives is becoming scarce and cumbersome — provisions, going into stores, travel, seeing family in person, and work — stepping outside for a walk is still available for us. It’s both a privilege and a responsibility.”

Butler noted that social distancing has still applied to her experience outside, as if walking everyone is zorbing along the beaten path rather than walking it.

“As I walk, I am keeping distance, unfortunately not going into any stores, and being very highly aware,” she said. “My COVID-19 day walks are this odd mix of joyful and somber. I greet each person I see with a wave or a hello. I have only run into one pal during a walk and we hung out on a fence six feet from each other and talked for a long time.”

The Woonasquatucket River Watershed Council has advised users of parks and paths to maintain distance and not to congregate.

“While nature, fresh air, and sunshine can be a tremendous help during trying times, we are all currently strongly encouraged to practice social distancing to slow the spread of COVID-19. This guidance applies when we enjoy the Greenway and other public spaces. If you arrive somewhere like the Greenway, and there are large crowds, turn around and come back another time,” the Woonasquatucket River Watershed Council suggested in a recent email.

But, as Friday noted, for many people the solitude of taking a walk or going for a hike is the best part.

“We did some focus groups around our new RI Walks website, and I expected people to want to have organized walks and join a group, but we had more people say that they prefer to go out for solitude, to enjoy the peace and quiet,” Friday said.

He also noted that this recent explosion in outdoor activity could lead to a greater appreciation for enjoying the trails, hikes, and outdoors beyond this crisis.

“I think when people get out there and see how much better they feel or see how nice it is and how it helps them relax, it will catch on, and they will remember that it’s something that makes them feel better,” he said.

Grace Kelly is a reporter for ecoRI News.

Arthur Waldron: COVID-19 probably originated in a Wuhan lab

Part of the vast city of Wuhan

PHILADELPHIA

Early this just-finished winter, physicians in Wuhan, China, became aware of cases of a new flu-like illness. It was related, as a so-called coronavirus, to the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome virus (SARS). SARS wrought havoc in China in 2003, causing some 8,000 infections, along with a mortality rate of at least 10 percent. It brought martial law to Beijing and elsewhere in China.

The new pathogen, which we’re now getting used to calling COVID-19, is also a coronavirus, thought to be endemic in bats, and transmitted to humans by an as yet unknown pathway (possibly the pangolin, a lovable denizen of the tropics).

The holocaust in China since December has now done previously unimaginable harm, with tens of thousands or more infected in the nation and a death rate comparable to SARS, bringing much of China to a panicky halt. And now there are hundreds of thousands – or more – cases in the world, and many thousands of deaths as the pandemic rolls on.

All of the noble doctors and other health providers who perished, such as Dr. Li Wenliang, who left a child and an infected pregnant wife -- and there were many more -- fearlessly confronted COVID-19, but without one crucial piece of information: namely, how it spread. It was known that the virus could jump from some animals to other animals, and from one person to another, but how exactly did it get from other animals to humans?

Throughout southern China exist hundreds of technically illegal markets, often huge, such as the one in Wuhan, holding wild species, some endangered, that are not legal to sell or eat. But they are consumed anyway. Bats are sold there, and bats are known to harbor the new coronavirus, as do many other unfortunate creatures. A mainstream story developed saying that the viruses jumped from the bats to another species, and thence to people.

The search is on for this creature. However, it probably does not exist and the whole theory about the virus is probably wrong. The simplest explanation for the epidemic is that somehow a form of the new coronavirus, which normally cannot infect human beings, either appeared through natural mutation and spread, or was engineered in a specially protected research facility for just such perilous work.

The epicenter of the infection is in Wuhan, Hubei, China’s great riverine transportation hub, with a population of 11 million — much bigger than New York. A vast wild animal market has long been there. But no way exists to demonstrate that this “wet market” is point zero. Quite the opposite, for a significant number of infections cannot be traced to the animals there.

Also in Wuhan is the Wuhan Institute of Virology and another laboratory configured specifically for such highly dangerous experiments as modifying bacteria and viruses so that they can yield vaccine or be used as biological weapons. These were built over 10 years with French assistance. That French plan for a research partnership fell through but the state-of-the art, level 4 (the highest-security) laboratory remained, and was put to use.

Now we approach the crux of the matter.

The findings of a long-term study, sponsored by the University of North Carolina, were published in Nature in August 2015. Nature is the most authoritative and trusted regular journal publishing new scientific results. Sixteen international experts participated in the study, including Dr. Zheng-li Shi and Dr. Xing-yi Ge, both of the level four laboratory in Wuhan. Here, with some explanation is what they reported:

“. . . We generated and characterized a chimeric virus expressing the spike of bat coronavirus in a mouse-adapted SARS-CoV [coronavirus] backbone. The [result] could] efficiently use multiple orthologs [genetically unrelated variants] of the human SARS receptor, angiotensin converting enzyme II (ACE ) to enter, reproduce efficiently in primary human airways cells, and achieve in vitro titers [sufficiently lethal concentrates] equivalent to epidemic strains of SARS-CoV.”

In other words, using one component of the new coronavirus and another one of SARS, one could create a new virus having a deadliness close to that of SARS and able to cross the species barrier, be fruitful and multiply, killing large numbers of victims, particularly elderly people.

From a virological standpoint this was an important breakthrough in understanding how viruses can propagate into new species. The doctors in the experiments, however, were shocked by its medical implications: Neither monoclonal antibodies nor vaccines killed it. The new virus, which was replicated and christened SHC104, [demonstrated] “robust viral replication, in vitro [lab-ware] and in vivo” [living creatures].

“Our work” the authors noted fearfully, “suggests a potential risk of SARS-CoV emergence from viruses now circulating in bat populations.” It seems likely to me that the new coronavirus did emerge in some such way, as a result of error at the Chinese P4 laboratory. Perhaps the search was for a vaccine. Less likely is that it was the result of research to create a biological weapon, for though such research is widespread worldwide (restarted in 1969 in the United States), the coronavirus is, in one sense, mild: Some people die, but most recover. It is not anthrax.

In any event, I think that an innocent but catastrophic mistake at the Wuhan P4 lab is now bringing something like Götterdämmerung to China.

If components of the new bat virus were connected in the laboratory to those of the known SARS virus, the result was a “virus that could attach functionally to the human SARS receptor, angiotensin converter enzyme II, with which it had similarities but no kinship (“orthologs”). The species barrier was thus crossed with a laboratory-created virus that could copy itself, reproduce in human airways, e.g., the lungs, and produce in glass laboratory equipment the equivalent of titers (amounts of liquid sufficiently concentrated) to achieve the strength of epidemic strains of SARS.

One intriguing piece of evidence appeared very briefly in the Chinese press.

A Southeast Asian editor wrote me:

“I also found this Caixin {Chinese media company} piece interesting. Especially the following paragraph:

{Prof. Richard Ebright, the laboratory director at the Waksman Institute of Microbiology and a professor of chemistry and chemical biology at Rutgers University} “cited the example of the SARS coronavirus, which first entered the human population as a natural incident in 2002, before spiking for a second, third, and fourth time in 2003 as a result of laboratory accidents.”

This article disappeared almost instantly but its contents have been circulating in Southeast Asia.

It indicates that laboratory mishaps were involved in SARS. So the same possibility cannot be ruled out now. The original article has been expunged in China, including from the Caixin archives.

Since then no more technical or scientific evidence has appeared. So we wait for an explanation from the Chinese government.

In China, the fabric of the society is tearing; its foundations and structures are bending and stooping under the lash of a deathly microorganism, apparently made by humans and somehow released, the effects of which few conceived or expected. Now populations of tens of millions around the world face and may well pay the ultimate price. The all-knowing Chinese Communist Party looks absurd and corrupt. In Wuhan supplies are scarce and crematories have worked 24/7 to dispose of the dead. The self-sacrificing medical profession, however, has little idea of where to turn for a cure.

We are in the midst of a global tragedy. Officials of the despotic Chinese government, which designed and built the Wuhan facility, seem ignorant about what they set in motion, while the biologists, with perhaps some exceptions, will recoil, as will subsequent generations, with what they have wrought.

Arthur Waldron is Lauder Professor of International Relations at the University of Pennsylvania and an historian of China. He’s also a longtime friend and colleague of Robert Whitcomb, New England Diary’s editor.

Affleck had to get out of Boston, but Charlie couldn't

“I knew I had to get out of Boston and stop making movies there, at least for one movie, otherwise no one would ever consider me for a movie that took place south of Providence.’’

—Ben Affleck, film actor, director and screenwriter

“Did he ever return?

No he never returned

And his fate is still unlearn'd.

He may ride forever

'neath the streets of Boston

He's the man who never returned.’’

— From the song “Charlie on the MTA’’. The song was written in 1949 and became a national hit when recorded by The Kingston Trio, in 1959.

The lyrics tell of a man named Charlie trapped on Boston's subway system, once known as the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA, which also included buses), now the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (which also includes commuter trains). The MBTA eventually named its electronic card-based fare- collection system the "CharlieCard" as a tribute to this song.

Music into paintings

Translation of "Firebird" II (Igor Stravinsky) (acrylic, ink, graphite on canvas), by Shany Porras, in her show at Fountain Street Fine Art, Boston, by appointment through April 26.

She told the gallery:

“My current paintings are translations of music into abstract paintings. These translations came about as I was looking inside myself for what to paint. What would be my muse? And how would I paint it? I remember a wise college professor who advised me to “paint what you know” while I was pursuing my B.F.A. at Rice University. At the time, I thought I didn’t know anything, really, so my paintings were disjointed. I was young and inexperienced. Now, well into adulthood, I finally see the connection of my love for music and abstract art. I also know that I have played the role of translator throughout my life. Early on I translated English to Spanish for my Mom when we first moved to the USA {from Venezuela}. Then, professionally, I took on roles that benefited from my ability to translate technology into regular business terms. Now as an artist I choose to translate music, which is inherently abstract, into paintings.’’

Annie's better than Ambien

Annie's always calm and cheerful,

Speaks no ill of friend or foe,

Always prudent and productive,

Meets temptation with a no.

Never gossips, never grumbles,

Eats fresh fruit instead of cake.

Spend an afternoon with Annie —

See how long you stay awake.

— “An Afternoon With Annie,’’ by Felicia Nimue Ackerman

'(Re)Generation' sounds good these days

Work by Ellen Schön in her current solo exhibition “(Re)Generation” at Boston Sculptors Gallery, by appointment only because of the COVID-19 emergency. The show features a new series of ceramic totems.

The gallery explains:

“Originally inspired by her daughter's pregnancy, the series evolved during the artist's residency at the Guldagergaard International Ceramics Research Center, in Skaelskor, Denmark.

“Schön's practice has embraced the capacity of ceramic vessels to evoke the gesture and stance of the human figure. Now departing from the vessel tradition (though indebted to it), these totems simultaneously explore the limits of abstraction, express contemporary feminist sensibilities, and reference archaic fertility figures such as Cycladic idols and the Venus of Willendorf. ‘The idea of regeneration affirms our connection to the past, while discovering what we carry forward,’ Schön explains.

”Harbingers of an unknown future, the totems simultaneously sing out and quietly listen, beseeching each other and us. Only the next generation will know whether their message is hopeful or dystopian.’’

Stick with stasis

“How many Vermonters does it take to change a lightbulb?

Three. One to change it and two to argue over why the old one was better.’’

—Old Vermont joke

“An old man is sitting on the steps of the general store on a fine spring day. A stranger comes along and tips his hat and comments on the beauty of the day. He pauses, searching for something more to say, and finally he says, “Bet you’ve seen a lot of changes around here.’’ To which the old man replies, ‘Ayup. And I’ve been against every one of them.’’’

— From “Pure Vermont,’’ by Edie Clark, in the October 1996 Yankee Magazine.

Open-heart surgery made easy

“Verily I Say Unto Thee’’ (oil on panel), by Procheta Mukherjee Olson, in her show of miniature paintings at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst Museum of Contemporary Art, March 26-April 26 — or not, depending on COVID-19.

James P. Freeman: Negative interest rates? Be careful what you wish for

“You OK?” -- Clay Easton, from the film Less Than Zero (1987)

BRAINTREE, Mass.

Last fall, as markets were reaching Everest heights, President Trump began calling for below-zero interest rates in the United States, a phenomenon that has beset many European countries and Japan, to little positive effect. While appealing on the surface, supporters of such an interest-rate environment should temper their enthusiasm and take caution: Be careful what you ask for.

On Sept. 11, 2019, President Trump tweeted, “The Federal Reserve should get our interest rates down to ZERO, or less, and we should then start to refinance our debt.” The president renewed such calls last November, during a speech at the Economic Club of New York. He claimed that comparatively higher interest rates in the United States “puts us at a competitive disadvantage to other countries.” And, more recently, at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, in January, he echoed similar sentiments. Other nations, Trump said, “get paid to borrow money, something I could get used to very quickly. Love that.”

Negative interest rates are not normal, and they have never occurred in America.

So, what exactly is going on here?

Typically, in any given lending arrangement, the borrower pays back principal and compensates the lender with interest for use of the money. A loan with a longer duration usually fetches higher rates; a loan with a shorter duration usually fetches lower ones.

But in some sectors of the global credit markets something strange has happened -- the underlying mechanics of that understandable and long-held lending model have changed. It is the borrower who is compensated, not the lender. In other words, a lender who lent $100 with a 3 percent interest rate received a $103 return. Now, that same lender may be receiving -- theoretically, in a market with negative rates -- only $97, not $103.

For nearly 40 years interest rates in the United States and around the world have dropped dramatically (in 1980 the U.S. Prime Rate peaked at 21.50 percent; today it stands at 4.25 percent, according to “FRED,” the economic research arm of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis). Both consumers and corporations have been the beneficiaries of the low cost of borrowing money. It fueled what some see as the greatest period of prosperity in America history. Causally and conversely, however, it acted as the catalyst for massive levels of borrowing, as the government for decades has spent more than it received. In addition, government -- at all public-sector levels, federal, state and local -- likewise has been a beneficiary, financing massive levels of debt at low cost. But the federal government is different.

The federal government is granted the authority to control both monetary policy (interest rates and money supply) as well as fiscal policy (taxes and spending). Created in 1913, the Federal Reserve (the “Fed”) is the country’s quasi-independent central bank, and responsible for supervising the nation’s banks, overseeing the stability of the financial system, conducting monetary policy and, perhaps most importantly, maintaining the dollar as a store of value. On the other hand, fiscal policy is determined mostly by Congress with input from the president. For decades, both the legislative and executive branches have agreed to increase the size and scope of government without paying for it (deficits and debts). And tax rates have trended downwards for decades too (most recently with the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017).

Ostensibly economic tools, fiscal and monetary policies are nevertheless dictated by political actors, and prone to political motivations. Nevertheless, such polices, when effected sensibly and even harmoniously, can promote economic growth and stability. Of course, global disruptions and market imbalances coupled with bad decisions have, at times, wrought havoc. Such events are mostly garden-variety downturns while others are more severe, like The Great Depression, which started in 1929, and The Great Recession of 2008-2009.

Policymakers took extraordinary measures in 2008-2009 to stave off a total collapse of the financial system and a real depression. Of particular import was unprecedented monetary policy. The Fed brought short-term rates close to zero and greatly expanded the money supply by injecting trillions of dollars into the financial system. As a result, markets recovered, and the U.S. economy went on to the greatest bull run in history. Notably, though, the Fed largely kept these extraordinary polices intact, even as the stock market rose to record highs and unemployment fell to near-record lows.

Therein lie the problems.

Some market observers have opined that the market rally in 2019 and early 2020 was a perversion precisely because of constant Fed intervention. They argue that this was a Fed-induced asset bubble. These same observers cite the central bank’s maintenance of artificially low interest rates (three reductions in the Federal Funds Rate in 2019), flooding the market with trillions of dollars in cash or liquidity (by buying U.S. Treasury securities, known as Quantitative Easing, “QE”), and what is called “Repo” (supporting overnight lending among big banks, a form of money flow or plumbing for Wall Street) -- all during a roaring market and booming economy. It was reasonable to ask, observers wondered, why the Fed was doing all this during good times. Such actions were historically reserved only for extreme market disruptions that threatened the American economy.

The Fed was not alone in its actions.

Most European countries did not see economic expansion of the size of the American one in the 2010s. Their recovery was much more muted. As a result, in order to spur economic activity, European interest rates were set even below American rates. In June of 2014, a stunning event occurred. The European Central Bank (ECB) introduced negative rates by lowering its deposit rate to minus 0.1 percent to stimulate the economy. It proved to be overall futile. Eurozone countries (and Japan) never fully recovered and economic growth remained anemic at best.

By 2019, 14 countries had sovereign debt with negative yield as markets and governments drove down rates. Today, the global pool of such securities is about $12 trillion, and includes some corporate debt. Last September, the ECB cut its already negative deposit rate to minus 0.5 percent. In fact, 56 central banks cut rates 129 times last year, according to data from CBRates, a central bank tracking service. Some market participants have questioned the efficacy of such monetary policy, given little to no economic growth as a result. And policy makers are perhaps finally realizing that monetary policy alone has its limits.

There’s a growing negative perception of negative rates reflecting the negative impact.

Still, there are other reasons why yields have plunged. Think of the basic supply-demand equation. While governments have been issuing an enormous supply of low-yielding debt there has also been an enormous demand for government securities. Most government bonds are known to be a safe harbor for investors in times of turbulence, as they can be used to hedge against all sorts of risk (market, political, etc.). Of course, the safest of safe harbors has been and continues to be the United States.

In times of crisis, global investors have always sought protection by buying U.S. Treasury securities, as these securities offered a reasonable rate of return and penultimate safety. But even in times of relative tranquillity these securities have been attractive for domestic investors, particularly pension plans, senior citizens, and financial institutions. Over time and into early 2020, a convergence of market dynamics -- heavy demand, along with heavy Fed buying and issuing of large quantities of Treasuries (supply) -- have brought yields down substantially and have made government securities very expensive. Even before the novel Coronavirus called COVID-19.

The long-term average yield of the U.S. 10-Year Treasury Note, the American bellwether security, is 4.49 percent. A year ago, the 10-Year yielded 2.64 percent. It has fallen steadily since (ycharts.com and FRED). Now, with the global pandemic, the yield recently hit an intra-day record low of 0.31 percent.

The Coronavirus has, if anything, exposed the fragility of current markets. In classic crisis mode, investors have been fleeing global stock markets and stampeding the U.S. government bond market. Yields across the spectrum of treasury maturities (3-month to 30-year) have set record lows, driven by record demand and Fed intervention with barrels of liquidity.

Just over a week into a global stock sell off, on March 3, the Fed cut the Federal Funds Rate by half a percentage point (for a targeted range of 1.0 percent to 1.25 percent) in response to the threat posed to the economy by the Coronavirus. This emergency action was the first time that the Fed cut rates for a public-health challenge, not a financial one.

And in another emergency move on Sunday, March 15, following two weeks of market carnage, the central bank set this rate to effectively zero as markets continue to roil -- matching similar action taken during the financial crisis in 2009, along with more massive QE. It is now entirely possible that the Fed Funds Rate may be set in a negative range and U.S. Treasury yields could turn negative for the first time as well. Even despite the slow lurch to negative yield, on a conference call on the same day of the latest action, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell dismissed the likelihood of using such a tool.

“We do not see negative policy rates as likely to be an appropriate policy response here in the United States,” Powell told reporters.=

Well.

As the robot in Lost in Space warned: “Danger Will Robinson! Danger!”=

No one in America quite knows how to navigate the unchartered frontier of negative yields. There is no play book or history book. Or Book of Revelation.

Some of the consequences of rates marching to zero are already apparent. One is that the government via the Fed (monetary policy) has incentivized undue risk-taking. Lower government bond yields have forced otherwise conservative investors to chase higher returns in stocks and corporate bonds, creating unmanageable asset bubbles. (Will Treasuries in 2020 become the tulips of 1637?)

Congress and the president (fiscal policy) have been incentivized to borrow even more money (under the absurd assertion that the country can “grow” its way out of debt; during the bull run debt grew significantly). Remember, candidate Trump in 2016 promised to not only reduce the national debt, but actually eliminate it. At over $23 trillion today (CNBC reported last February), the debt has grown by $2 trillion under President Trump.

Arguably, disastrous monetary policy has financed even more dreadful fiscal policy.

America used to borrow for the future. We now borrow from the future. Record low yields have fueled record amounts of debt. One unintended consequence of this predicament is that it unwittingly gives legitimacy to the absolutely ludicrous idea of “Modern Monetary Theory” (MMT). Properly understood, the theory allows that government can and should print as much money as it needs to spend because it can not become insolvent, unless there is a political reason to do so. MMT treats debt simply as money that the government has placed into the economy and did not tax back. Furthermore, and rather dangerously, MMT advocates believe that there are no consequences to staggering levels of debt. They simply ignore abundant evidence to the contrary (history is littered with examples of sovereign default).

There are more tangible and immediate consequences to consider as well. In a simpler time, the bond market was known as the “fixed-income” market. For a good reason. Most bonds paid a fixed amount of interest, usually every six months. A steady stream of interest provided investors with income. Negative yield penalizes savers who have relied upon Treasury securities for safety and some rate of return. Why would seniors want to pay borrowers for the use of their money?

Negative yield also affects banks and other financial institutions, such as insurance companies. These entities rely upon yield to fund operations. Annuities, for instance, are financial contracts whose rates of return depend on market instruments, such as fixed-income securities. And pension plans assume a certain future return for actuarial purposes.

JPMorganChase Chairman and CEO Jamie Dimon has expressed concern. At the same Davos event that the president spoke at in January, the head of America’s biggest bank expressed “trepidation” about “negative interest rates.” He added that, “It’s kind of one of the great experiments of all time, and we still don’t know what the ultimate outcome is.” Last October he told a group attending the Institute of International Finance he would “not buy debt at below zero.” And with a sense of gravitas, Dimon concluded, “There is something irrational about it.”

If the government started issuing negative-yielding debt, banks would need “to find other ways to replace the income they need to generate from their deposits at the Fed,” believes Michael Hennessy, chief executive of Harbor Crest Wealth Advisors. One way to do that would be to raise fees on consumers. Another option -- a nuclear option? -- would be for banks to offer negative deposit rates to the average saver and consumer. That outcome is nearly unimaginable.

Then there is the tax code. Writing for The Wall Street Journal last November, Paul H. Kupiec said he believed that the tax code can’t handle negative rates. “Should negative interest rates one day become reality,” he writes, “the tax code will need to be amended.” Kupiec also says that negative rates would effectively be a “new federal tax levied by the Fed on banks.” Negative interest rates are treated as a consumer expense, and right now current law doesn’t allow such an expense to be deducted when calculating taxable income.

Finally, there is the general perception that negative yield carries: People feel poorer. They would be drained of income. They would not be paid for the use of their money. On the contrary, they may be paying people for the use of their money. Marked deflation is just as bad as marked inflation. Besides, such a precipitous drop in Treasury yields and the corresponding inversion of the yield curve (when yields in longer maturities are lower than yields in shorter maturities) portend recession. Recessions are normal and natural. Yet, with twisted irony, the federal government -- with all its extravagant intervention -- has exacerbated not only the likelihood of a recession but perhaps its severity, too.

Joseph Brusuelas, RSM chief economist and a member of The Wall Street Journal’s forecasting panel, strikes a cautionary tone. He reasons: “Because the U.S. economy is so highly ‘financialized’ [meaning it is reliant on big banks to provide liquidity], negative rates wouldn’t yield a good outcome in the long-term.”

James P. Freeman is the director of client relations at Kelly Financial Services LLC, based in Greater Boston. This content is for informational purposes only and does not constitute an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to purchase any interest in any investment vehicles managed by Kelly Financial Services, LLC, its subsidiaries and affiliates. Kelly Financial Services, LLC does not accept any responsibility or liability arising from the use of this communication. No representation is being made that the information presented is accurate, current or complete, and such information is at all times subject to change without notice. The opinions expressed in this content and or any attachments are those of the author and not necessarily those of Kelly Financial Services, LLC. Kelly Financial Services, LLC does not provide legal, accounting or tax advice and each person should seek independent legal, accounting and tax advice regarding the matters discussed in this article.