Brian Wakamo: Get a lot of federal offices out of Washington

Downtown Milwaukee, a good place to add federal offices to serve the Midwest.

Via OtherWords.org

Americans of all political stripes distrust the federal government.

For years, the name of the nation’s capital has been used as shorthand for federal overreach and bloat. For most Americans, Washington, D.C. is hundreds of miles away — and a million ways disconnected — from them.

The Washington area is home to hundreds of thousands of federal jobs, and many unpopular agencies. But agencies that are more spread out, like the Postal Service, are significantly more popular.

So here’s a simple idea: Move more of the federal government to the rest of the country.

Studies show that once you get to know people different from you, your prejudice towards them drops. Could that same approach also bridge the deep disconnect between Americans and their national government?

One way to sweeten the pot would be the promise of tens of thousands of jobs to areas that need them.

A geographically diverse federal government would be bolstered by the Green New Deal program championed by progressives such as Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

Bringing back past agencies, like the Depression-era Works Progress Administration, to help build green infrastructure would help transition this country off fossil fuels and into a sustainable future. It would guarantee jobs, maybe good union jobs, for countless workers.

A new Works Progress Agency could establish offices in places like Milwaukee, where it could build a long-discussed high-speed rail line connecting the cities of the Midwest. Or in Phoenix, where it could construct more solar-power plants in the desert. It could set up in places like Jackson, Miss., helping to build sustainable co-op farms, or on the Gulf Coast, to fight climate change.

Similarly, a single-payer, Medicare for All health service would also need to have offices in communities. It would create health care jobs in places often abandoned by providers, boosting economies and bringing affordable care to millions.

Meanwhile, reintroducing postal banking would bolster Post Office finances and bring banking to millions of underbanked Americans.

There’s another benefit to all this: the revitalization of our heartland cities. Midwestern cities like Detroit, Cleveland and Milwaukee are full of classical architecture and cultural amenities, but have lost hundreds of thousands of jobs from the erosion of manufacturing. New federal jobs could reverse decades of decline in these grand cities.

Why stop there?

The National Weather Service could move to New Orleans or another area impacted by the climate change they study. The U.S. Geological Survey could move out to Sacramento, which knows something about earthquakes. Agencies that deal with farming and rural development could set up in Farm Belt areas like Kansas City, where they’d be more attuned to the people they serve.

Spreading out the federal government would help rebuild the trust that’s eroded in recent years and provide jobs that are unionized, well-paying, and accessible to people often excluded from the broader economy.

Decentralizing government is popular across the political spectrum, and the federal government is bogged down by its centralization in D.C. Why not put it more in line with its original mission — to be of the people, by the people — and bring it to the people that need it most?

Brian Wakamo is a research assistant at the Institute for Policy Studies.

Ocean pollution in black and white

“Closing the Sea 1’’ (black and white silver print), by Boston-basedO Patricia Kelliher, in her show “Closing the Sea,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, through Jan. 27. She highlights ocean pollution through semi-abstract black-and-white photos.

Mysterious NEPOOL; memories of the great blackout

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Rhode Island, reports GoLocalProv, has the third-highest overall utility costs in America. That’s not very surprising since it still depends on expensive, end-of-the-pipeline natural gas to generate much of its electricity and provide fuel for heat and cooking in many buildings. It also has very expensive, if fast and generally reliable, Internet service.

But there’s hope: Technology is gradually bringing down the cost of locally produced energy such as solar and wind, and there will probably be more competition entering the Internet sector because of technological advances and corporate shuffles.

To read the GoLocal piece, please hit this link.

One reason that electricity prices are so high in New England may be the New England Power Pool (“NEPOOL”). This trade group is dominated by big utilities and power-plant owners, reports New Hampshire Public Radio (NHPR), and its meetings aren’t open to the public.

Independent Service Operator of New England (ISO), created by the Feds to keep the region’s power on, is charged with overseeing the region’s grid. NEPOOL makes recommendations to ISO on rates and on whether and where new transmission lines should be strung, NHNPR reports. But NEPOOL can submit its own regulatory ideas to the government, which may contradict those of ISO.

Don Reis, New Hampshire’s utility ratepayer advocate, told NHPR: NEPOOL is “more powerful than the other stakeholder advisory boards at other regional transmission organizations around the country.’’

Red marks the area hit by the Great Northeast Blackout of 1965.

We need to know how much of New England’s high electric rates can be explained by the structure and power of NEPOOL.

To read the NHPR story, please hit this link.

The creation of ISO and NEPOOL can be traced back to federal regulators’ efforts to prevent a repeat of the huge blackout that darkened most of the Northeast on Nov. 9 and 10, 1965.

I remember it fondly, but then I wasn’t stuck in an elevator. I was in a classroom in a girls’ school in Waterbury, Conn., for a rather vague course called “Philosophy of Religion.’’ The class was one of the very few co-ed classes open for students at my boys boarding school, which was in another town about eight miles away.

At about 5:20 that dark day, the room went pitch dark and someone muttered: “The wrath of God!’’ Weirdly, a now-long-dead classmate (and terrific musician) called Al d’Ossche, from New Orleans, found a candle in the room and lit it using a cigarette lighter.

Chuckling nervously, the spinsterish teacher soon dismissed us, and we headed out the door to find the grumpy driver and his van that would take us back to our school. With most everything dark except for car headlights, we had an eerie, exciting trip up and down the hills. When we got to the school we carefully walked up to second-floor apartment of Mr. Dunlop (an English teacher) and his eventual ex-wife, off the dorm corridor where most of the seniors lived. Thank God there were no electric door locks at the school then.

There were a couple of flashlights and hurricane lamps lit, along with the glow of cigarettes; seniors were allowed to smoke in teachers’ apartments if the teachers (aka “masters’’ – sounds a little S&M) permitted. And in the background you’d hear on a transistor radio: “77 WABC – home of the All Americans!’’ from New York. The WABC DJs and news folks reveled in describing the drama of Manhattan gone dark.

It was a delightful evening, in part because it was impossible to do any “homework.’’ It was one of those gleeful, lovely inconveniences, like, for some, southern New England’s Great Blizzard of ’78 – that is gleeful, for a day or two….

Tim Faulkner: Fossil-fuel groups try to drown out global-warming science

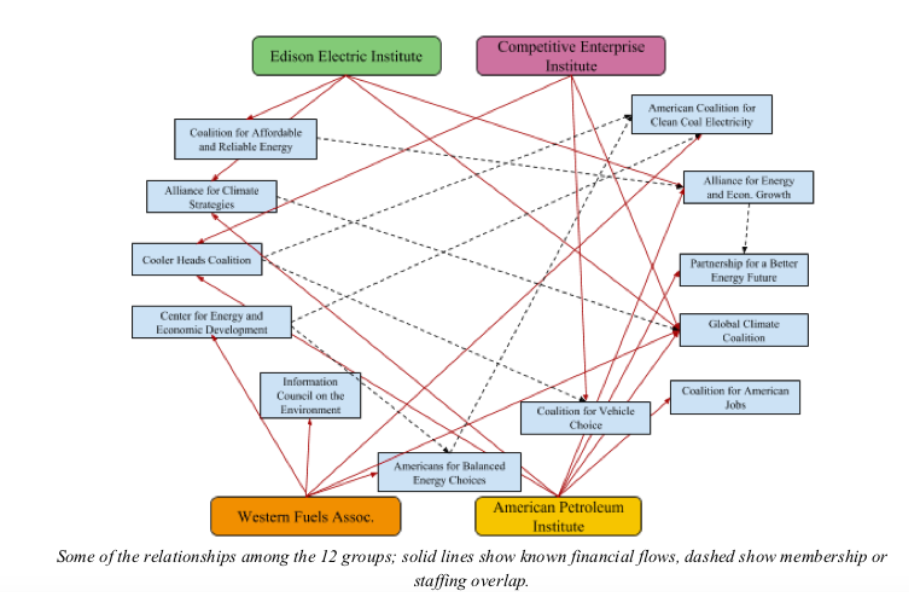

This chart shows the web of groups that share money and staff to spread misinformation about climate change. (Brown University Climate and Development Lab)

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

TV ads spinning a positive message about fossil-fuel companies are running more frequently as climate change is poised to move into the legislative spotlight now that Democrats have taken control of the U.S. House.

Recent commercials by the ExxonMobil Corp. show millennials in lab coats, waiting tables, and welding pipeline tubes: jobs that are ostensibly created by the fossil fuel-extraction industry. Missing are the health and environmental impacts of oil spills and natural-gas leaks, acidifying oceans and displacement and destruction caused by powerful storms — all of which are the result of drilling, shipping, processing, and the burning of fossil fuels. This new PR blitz is the latest action in a decades-long offensive to counter the science proving that fossil fuels are destroying the planet.

A project led by the Climate and Development Lab at Brown University intends to expose and delegitimize this feel-good narrative by revealing the people and money behind climate-opposition efforts. It also aims to remind the public of what ExxonMobil and other energy companies have known for decades: that fossil-fuel emissions are destructive.

“This really is a failure to warn us that (fossil-fuel companies) know their products are going to cause all of these problems but they are not warning the public about it,” said Robert Brulle, a visiting professor at Brown University and one the leading national researchers on climate-change denialism.

One of the goals of the investigation is to bring to the fore the campaign of denialism and the accompanying disinformation funded by fossil-fuel corporations, utility companies, and right-wing policy groups.

“They are selling us the idea of oil, prosperity, and fossil fuels are all the same thing,” Brulle said. It’s “a very, very subtle manipulation that runs into the billions of dollars over decades.”

Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, D- R.I., has been broadcasting the issue from the Senate floor since 2012 with his Time To Wake Up speeches. But without hearings or other public debate led by Congress, clime-change legislation has been suppressed by intimidation, political contributions, and a mass media-marketing campaign to discredit the science.

“The biggest gap that we have on a pathway to success on climate is our failure to have shown the public who’s behind the curtain on so much of the nonsense that gets propagated as climate denial,” Whitehouse said.

Whitehouse is part of the multifaceted effort to out the climate-denial network and its funders. This includes a forthcoming book, new research, and legislation.

In Washington, D.C., Whitehouse and Rep. David Ciciliine, D-R.I., have introduced an updated version of the proposed Disclose Act, which prevents corporate donors from hiding their campaign donations in shell corporations. Whitehouse said making public such donations will cause the collapse of “the special interest hiding systems” and “laundering systems.”

“The dark money disappears when it’s required to become transparent,” he said. “It’s like when you flip on the light and the cockroaches scuttle for the shadows.”

At Brown University, Caroline Jones, a third-year student, wrote a 37-page report on the fossil-fuel spin apparatus with a team of classmates, Brulle, and professor J. Timmons Roberts. Jones delivered her findings to the Climate Action Task Force in the U.S. Senate.

“A lot of these groups engage in pretty blatant pubic misinformation campaigns,” Jones said. “They run targeted strategies to specific demographics, to people who they think are vulnerable to misinformation.”

During a recent meeting with members of the media, Jones, Roberts, and Brulle presented slides showing the complex network of companies, public-relations firms, lobbyists, and bogus environmental groups that spread climate disinformation. Brulle’s research dates back until 1967 and his current work focuses on the years 2010 to 2015.

The spider web of money comes from oil and gas companies such as Shell, Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Texaco; from automakers such as Ford and General Motors; and from utilities and chambers of commerce. They fund groups such as the National Coal Association and the American Petroleum Institute (API), and “astroturf” denialist groups with ambiguous names such as Global Climate Coalition and the Cooler Heads Coalition.

The report Countermovement Coalitions profiles these groups and explains how they create the appearance of public support for deregulation, while also reminding politicians that they may lose election/re-election by opposing corporate priorities.

In Rhode Island, the report looks at the institutions that have resisted climate and renewable-energy legislation. National Grid has been one of the top opponents to legislation endorsed by the Environmental Council of Rhode Island, a coalition of 60-plus environmental groups. National Grid opposed seven bills that supported renewable energy and action on climate change in the General Assembly between 2012 and 2017, according to the Climate and Development Lab.

The state’s primary electric and natural-gas utility also donates to the national anti-climate group Edison Electric Institute (EEI). The organization has opposed — or funded groups that oppose — net metering, one of the core renewable-energy policies that allow homes and businesses to sell excess solar energy to the power grid. EEI officials also question whether climate change is manmade.

The trade association of U.S. electric utilities works closely with the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), the conservative policy group with massive influence in state legislatures. ALEC is funded by climate deniers like the Koch brothers and Koch Industries. Among its initiatives, ALEC has pushed President Trump to rollback climate regulations and open public land to fossil-fuel and mineral extraction.

The Energy Council of Rhode Island (TEC-RI) also opposed seven climate and renewable-energy bills proposed at the Statehouse between 2012 and 2017. TEC-RI lobbies on behalf of the state’s largest electricity users and manufacturers. Other opponents of climate and energy legislation include the Greater Providence Chamber of Commerce, the Rhode Island Pubic Expenditures Council (RIPEC), and the Rhode Island Building and Construction Trades Council.

National Grid confirmed that it continues to be a member of EEI. In response to the groups connection to ALEC and its front groups and opposition to climate legislation, National Grid said, “We as a company support the science of climate change.”

Spokesman Kevin O’Shea noted National Grid’s backs the nine-state Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, the nation’s first cap-and-trade program. He said National Grid also endorses the Paris Climate Accord’s Clean Power Plan. O’Shea also cited National Grid’s involvement with the Block Island Wind Farm and touted a corporation plan to cut greenhouse-gas emissions 80 percent by 2050.

EEI also has financial ties to groups fighting climate-change regulations, such as the Coalition for Affordable and Reliable Energy, the Global Climate Coalition, Alliance for Climate Strategies, and the Alliance for Energy and Economic Growth.

According to research by Brulle and Jones, most of these denial group share staff. They lobby Congress to oppose climate legislation, spread false information about climate science, and run public-relations and advertising campaigns that boost the image of fossil fuels.

Jones studied 12 front groups that spread climate denialism, four of which received money from EEI.

“The leaders in many of these denial coalitions have held highly influential positions in the Republican party and some are now in positions in the Trump administration with direct control over the future of U.S. climate and environmental policy,” according to their research.

EEI has contributed to the Global Climate Coalition (GCC) and the Competitive Enterprise Institute (CEI). In 2016, a CEI official managed Trump’s transition at the Environmental Protection Agency. The GCC was a key player in rejecting the Kyoto Protocol and spread false narratives about the effects of carbon dioxide.

Jones’ research paints an unflattering history of the astroturf groups, showing how they disbanded after bad publicity only to reform under new names.

“They are all funded by the same people, a lot of them have the same leadership and membership,” Jones said. “They’re run out of the same offices, often times. And they engage in really slimy tactics to get their message across and to manipulate pubic opinion.”

Groups such as the Information Council on the Environment (ICE) received funding from EEI to support one of the first multi-media efforts to cast doubt on climate change. The effort relied on dubious climate experts to sow doubt about global warming through TV appearances and opinion pieces in newspapers in select cities and towns. Although ICE had a brief existence, it created a model that is used by many anti-climate networks today.

The denial groups use these tactics to turn their economic capital into cultural and political capital. Anti-climate corporations outspend environmental groups 20 to 1.

“When you have multiple voices and multiple media outlets, if you can come in there with a big swath of money and push it across all of these outlets all the time that gives you an enormous advantage,” Brulle said. “If you’ve got a megaphone that can just drown people out, what does that say about democracy?”

Tim Faulkner is a journalist with ecoRI news.

When near our journey's end

When all the fiercer passions cease

(The glory and disgrace of youth):

When the deluded soul in peace,

Can listen to the voice of truth:

When we are taught in whom to trust,

And how to spare, to spend, to give,

(Our prudence kind, our pity just),

'Tis then we rightly learn to live.

Its weakness when the body feels,

Nor danger in contempt defies:

To reason when desire appeals,

When, on experience, hope relies:

When every passing hour we prize,

Nor rashly on our follies spend:

But use it, as it quickly flies,

With sober aim to serious end:

When prudence bounds our utmost views,

And bids us wrath and wrong forgive:

When we can calmly gain or lose, -

'Tis then we rightly learn to live.

Yet thus, when we our way discern,

And can upon our care depend,

To travel safely, when we learn,

Behold? we're near our journey's end.

We've trod the maze of error round,

Long wand'ring in the winding glade:

And, now the torch of truth is found,

It only shows us where we stray'd:

Light for ourselves, what is it worth,

When we no more our way can choose?

For others, when we hold it forth,

They, in their pride, the boon refuse.

By long experience taught, we now

Can rightly judge of friends and foes,

Can all the worth of these allow,

And all their faults discern in those;

Relentless hatred, erring love,

We can for sacred truth forego;

We can the warmest friend reprove,

And bear to praise the fiercest foe:

To what effect? Our friends are gone

Beyond reproof, regard, or care;

And of our foes remains there one,

The mild relenting thought to share?

Now 'tis our boast that we can quell

The wildest passions in their rage;

Can their destructive force repel,

And their impetuous wrath assuage:

Ah! Virtue, dost thou arm, when now

This bold rebellious race are fled;

When all these tyrants rest and thou

Art warring with the mighty dead?

Revenge, ambition, scorn, and pride,

And strong desire, and fierce disdain,

The giant-brood by thee defied,

Lo! Time's resistless strokes have slain.

Yet Time, who could that race subdue,

(O'erpowering strength, appeasing rage,)

Leaves yet a persevering crew,

To try the failing powers of age.

Vex'd by the constant call of these,

Virtue a while for conquest tries:

But weary grown and fond of ease,

She makes with them a compromise:

Av'rice himself she gives to rest,

But rules him with her strict commands;

Bids Pity touch his torpid breast,

And Justice hold his eager hands.

Yet is their nothing men can do,

When chilling age comes creeping on?

Cannot we yet some good pursue?

Are talents buried? genius gone?

If passions slumber in the breast,

If follies from the heart be fled;

Of laurels let us go in quest,

And place them on the poet's head.

Yes, we'll redeem the wasted time,

And to neglected studies flee;

We'll build again the lofty rhyme,

Or live, Philosophy, with thee:

For reasoning clear, for flight sublime,

Eternal fame reward shall be;

And to what glorious heights we'll climb,

The admiring crowd shall envying see.

Begin the song! begin the theme! -

Alas! and is Invention dead?

Dream we no more the golden dream?

Is Mem'ry with her treasures fled?

Yes, 'tis too late,--now Reason guides

The mind, sole judge in all debate;

And thus the important point decides,

For laurels, 'tis, alas! too late.

What is possess'd we may retain,

But for new conquests strive in vain.

Beware then, Age, that what was won,

If life's past labours, studies, views,

Be lost not, now the labour's done,

When all thy part is,--not to lose:

When thou canst toil or gain no more,

Destroy not what was gain'd before.

For, all that's gain'd of all that's good,

When time shall his weak frame destroy

(Their use then rightly understood),

Shall man, in happier state, enjoy.

Oh! argument for truth divine,

For study's cares, for virtue's strife;

To know the enjoyment will be thine,

In that renew'd, that endless life!

— “Reflections,’’ by George Crabbe (1754-1832)

Always leaving the Northeast

An unofficial flag of New England.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Every once and while a story comes out about people leaving the Northeast, especially to move south, for jobs, lower taxes, cheaper housing, less winter and so on. These stories have been a staple of journalism since the invention of air-conditioning, which made manufacturing and its jobs more attractive in the South. And yet the Northeast remains the richest part of the country. That’s because it has the academic institutions, dense centers of skilled workers and several “world cities’ that are so closely associated with wealth creation and preservation. And it’s on the coast.

The large number of affluent people in the Northeast helps explain why property prices and taxes are so high here: They can bid up prices.

As for Northeast’s weather: Yes winter in the region can be tedious, but most of the year is fairly mild and the region rarely suffers the floods and droughts so frequent in much of the rest of the country. And we have plenty of fresh water. It’s interesting, by the way, that the happiest place in the world appears to be cold, dark Scandinavia, at least in part because of its public services. (Still, I think I’ll nip down to Florida for a week soon to break up the winter.…)

And there’s what should be an obvious reason why population growth in the Northeast is so slow – the region has long been densely populated and urbanized; it’s much further along in development than most of the Sunbelt. Consider that the seven most densely populated states are, in order of density: New Jersey, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Maryland, Delaware and New York (even with the vast Adirondack wilderness). They aren’t going to empty out as people move to Florida and Texas subdivisions.

The most serious demographic challenge facing the Northeast is its aging population. This is an especially serious problem for Rhode Island, exacerbated by its deeply entrenched cynicism and parochialism; someone once called it an “urban backwater.’’ It needs a higher percentage of younger adults to start and grow businesses and to help pay the soaring social costs of the elderly. More on that to come in future columns.

I’m sure that cheaper land and lower taxes (except for regressive sales taxes, which tend to be highest in the Sunbelt) will continue to draw many from the Northeast for some years to come. But I’m just as sure that the Northeast will remain the richest part of the country. And many of those who stay will appreciate its slow population growth, which means less sprawling development, and a healthier natural environment, than in much of the country. And eventually, growing populations and other demographic change will lead to political pressures for more and better public services, more controls on land development and higher taxes in the Sunbelt – even as the effects of global warming make them more problematic.

David Warsh: Americans should expect to have to talk it out

“The Conversation” (1935), by Arnold Lakhovsky.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It’s a commonplace that economics in the industrial democracies in the years after World War II took on many outward aspects of an engineering discipline. A “new welfare economics,” pioneered in Britain by A.C. Pigou, Nicholas Kaldor, John Hicks and others, led in the next generation in the U.S. by Paul Samuelson, supported the privilege of economists to give advice as experts on a wide variety of topics. Free trade might help some people and hurt others, for instance, but overall gains would be more than sufficient for the winners to compensate the losers. Thus government engineering could increase welfare across the board.

Two subfields of economics emerged in the 1950s which at first seemed to be at cross purposes, except that both had trouble with the newly dominant welfare economics. Social choice, from Kenneth Arrow, concerned itself with voting systems. Public choice, from James Buchanan and Gordon Tullock described itself as “the economics of politics”: legislative log-rolling, lobbying, pandering to the electorate and all that. Buchanan’s “politics without romance” seemed to exhibit a strong bias in his further explication of its underlying principle: “government is something to seek protection from, not to exploit.” But in fact his concern was simply that the motivations of policy-makers be examined as carefully as those of everyone else.

In her prize-winning article on the evolution of the system economists use to classify the literature of their profession, historian Beatrice Cherrier told how by the 1980s the two subfields had grown closer to one another and somehow seemed to be on the brink of becoming a major new field. Indeed, 5 percent of the profession was then described as working on problems of public choice. So editors of the Journal of Economic Literature came up with a new name to encapsulate both fields, as well as some related studies: “collective decision-making.” It turns out that the collision of collective decision-making with welfare economics conceals a pretty interesting story.

It had been Kaldor who first formulated the principle of compensation. Following the argument that John Stuart Mill had made a century before against Britain’s Corn Law program of price supports, Kaldor asked why not simply compensate those who suffered from a given policy adoption if everyone would gain something over all? There would be no need for the economist to prove that no one would suffer as a result of the adoption of the plan. A few years later, in The Foundations of Welfare Economics, John Hicks introduced production possibility frontier diagrams as “a perfectly objective test” of the efficiency of improvement plans – or their lack thereof. This would become the basis of the “scientific analysis” of welfare.

A few years after that, the young American economist Arrow asked if the same thing could be said of majority voting, where many voters of different views were involved. To make his model work, he made a key assumption: that individual preferences were given and couldn’t be changed by the decision process. Arrow concluded, to general surprise, that no system of voting would produce an ordering that was consistent with individuals’ underlying preferences. Bad enough that this seemed to undercut the new welfare analysis. What if the preferences were to change as a result of the process? Then new welfare economics would make no sense at all.

Three years later, in “Individual Choice in Voting and the Market,” Buchanan, then a professor at the University of Virginia, made precisely the counter-argument; that individual preferences can and do change in the process of decision-making; that this was the whole point of adducing evidence and learning from debate. Over time, Buchanan’s argument has carried the day. Forty years later, Amartya Sen, of Harvard University, wrote “[I]t is only through Buchanan’s expansion of Arrow’s departures that we can do justice to the Enlightenment enterprise of advancing rational decision-making in societies, which lies at the foundation of democratic modernity.”

I know all this (and have paraphrased much) from having read Escape from Democracy: The Role of Experts and the Public in Economic Policy (Cambridge, 2017), by David Levy, of George Mason University, and Sandra Peart, of the University of Richmond. Levy and Peart were interested in calling attention to the views of Buchanan’s teacher, Frank Knight, of the University of Chicago, who sank into relative obscurity after retiring from Chicago in 1955 – except for the half-year he spent lecturing at the University of Virginia, enough to become a founding member of the Virginia school of political economics. The two are at work now on a larger book about just what that Virginia school represented – as distinct from the Chicago school. You can expect to hear much more about it in a year or three.

Knight liked to quote James Bryce, Britain’s ambassador to the Unites States from 1907 until 1913, and author of The American Commonwealth: “Democracy is government by discussion.” Knight himself put it this way:

In contrast to natural objects – even with the higher animals – man is unique in that he is dissatisfied with himself; he is the discontented animal, the romantic, argumentative, aspiring animal. Consequently, his behavior can only in part be described by scientific principles or laws.

The new welfare economics is by now pretty well discredited, and not only by the widespread failure to compensate the losers. But the instinct of deference to experts is still pretty well embedded in our political culture. Perhaps it needs to be checked a little in favor of the virtues of democratic debate. George Stigler, who also had been Knight’s student, objected to the supposed expertise of the new welfare economics with respect to policies by invoking goals: “The primary requisite for a working social system is a consensus on ends. The individual members of the society must agree upon the major ends that society is to seek.”

One of the perils of being a solo practitioner is the news business is that once you start thinking about something, there’s no one there to make you stop. This topic is indeed the topic I cut short last week. The moral this week is pretty much the same. The rest of us, not the experts, are the jury.

Whether you are worried about the future of a divided country, impatient about the debate about the policies of President Trump, or eager to decide the appropriate policy against global warming, it helps to think of the question as akin to the process of jury deliberation, twelve persons making decisions together around a table in a room. Granted, 330 million souls, inhabiting 4.5 million square miles, is some As-if. But the basic principles are the same. Accept that opinions will be drawn from all walks of life, without regard to income or education. Expect to have to talk it out. Listen to the experts and the commentators. Consider the evidence that they (and nature) present. Cross-examine them as best you can. Talk some more. Strive for consensus, and be patient. Expect a verdict to be reached only when consensus is in sight.

David Warsh, an economic historian and veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran.

Norah Lawter: Time for a Green New Deal

Via OtherWords.org

Lately there’s been a lot of bad news about climate change and the future of humanity.

In October, the United Nations issued a major report warning of a climate crisis as soon as 2040. The day after Thanksgiving, the Trump administration tried to bury the release of its own report on the dire effects of climate change already occurring in the United States, which included dark predictions for the future.

In December alone, we learned that 2018’s global carbon emissions set a record high. NASA detected new glacier melts in Antarctica. There were wildfires. Coral reef bleaching. Ecosystem upheaval in Alaska as the arctic ice melts.

Meanwhile the Trump administration sent an adviser to the U.N. climate summit to promote coal and warn against climate “alarmism.”

So this all sucks. But here’s the thing about climate change: You can either ignore it, get depressed about doomsday scenarios, or believe that no matter how badly we’ve screwed up as a species, we’re also smart and creative enough to fix this.

If the alternatives are ignorance and despair, I’ll choose hope. Every single time.

So where can we focus our hope? What can we actually do about climate change?

I’m excited about the Green New Deal, an idea that’s been kicking around since 2007 but was popularized this fall by Representative-elect Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D.-N.Y.) and the youth-led Sunrise Movement. At least 37 members of Congress have signed on, along with dozens of activist organizations.

Not only a plan to shake up environmental policies, it’s also a massive jobs program, named after the Depression-era New Deal. The basic idea is to get us to 100 percent renewable energy by 2035, by putting Americans to work building a new energy infrastructure.

It merges the immediate concerns of working Americans — jobs and the economy — with the long-term concerns of climate change. We don’t have to choose between economic sustainability and environmental sustainability.

“This is going to be the Great Society, the moonshot, the civil rights movement of our generation. That is the scale of the ambition that this movement is going to require,” said Ocasio-Cortez during a town hall meeting with Bernie Sanders.

The ambitious plan touches on a “smart” grid; energy-efficient buildings; sustainable agriculture, manufacturing, transportation, and infrastructure; and exporting green technology to make the U.S. “the undisputed international leader in helping other countries transition to completely carbon neutral economies.” Think of the scale of this program, and then think of all the jobs that would be created. This could be huge for rural America in particular.

Will the Green New Deal be expensive? Probably. But that doesn’t mean it will be a drag on our economy.

A recent study by the Global Commission on the Economy and Climate revealed that we could save $26 trillion, worldwide, if we shifted to sustainable development. Another new study shows wind and solar power to be the cheapest sources for electricity around the world. Last year, the Republican mayor of Georgetown, Texas switched his city to 100 percent renewable energybecause of the low costs in the long-term.

On the other hand, at the UN climate summit in Poland, some of the world’s most powerful investors warned of a major financial crash if we don’t solve the climate crisis.

Is the Green New Deal too ambitious? No. We need ambition. The impending climate crisis is the biggest problem the human race has ever faced, and we can’t think small.

So let’s get visionary. Let’s dream big. Let’s fight for our children, and let’s invest in their future.

Norah Vawter is a freelance writer living in Northern Virginia.

Pay attention!

“Self Portrait as a Beautiful Lady’’ (detail), by Arhia Kohlmoos, in the show “Depth of Perception,’’ at Fountain Street Fine Art, Jan. 2-27.

The gallery says the show:

“{E}xplores the concept of taking notice. For many people this action represents a single moment in time that encourages reflection and to focus one’s attention on the present. It can be viewed as the link between human and spirit; darkness and light; scarcity and abundance. ‘‘

'Familiar as an old mistake'

The Worship of Mammon, by Evelyn De Morgan.

Time was when his half million drew

The breath of six per cent;

But soon the worm of what-was-not

Fed hard on his content;

And something crumbled in his brain

When his half million went.

Time passed, and filled along with his

The place of many more;

Time came, and hardly one of us

Had credence to restore,

From what appeared one day, the man

Whom we had known before.

The broken voice, the withered neck,

The coat worn out with care,

The cleanliness of indigence,

The brilliance of despair,

The fond imponderable dreams

Of affluence,—all were there.

Poor Finzer, with his dreams and schemes,

Fares hard now in the race,

With heart and eye that have a task

When he looks in the face

Of one who might so easily

Have been in Finzer's place.

He comes unfailing for the loan

We give and then forget;

He comes, and probably for years

Will he be coming yet,—

Familiar as an old mistake,

And futile as regret.

— “Bewick Finzer,’’ by Edward Arlington Robinson (1869-1935), a native of the Maine Coast

Relationship studies

“Small Blue Thing’’ (oil on canvas), by Christopher Sullivan, in his show “Between the Lines,’’ at the Bromfield Gallery, Boston, Jan.2-27. He paints to probe relationships.

Another New England college going under

Newbury College’s motto, translated from Latin, is, ironically, “Let It Flourish’’.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

‘So another in the surplus of small private New England colleges will die. Newbury College, in Brookline, will shut down at the end of the spring semester because it can’t rope in enough tuition money to keep going. There will be more. I wonder how many of these usually attractive, bucolic campuses can be reused as corporate campuses, retirement communities, affordable housing or even outpatient health centers.

Chris Powell: Connecticut should put casino rights out to bid

The Mohegan Sun casino, in Uncasville, Conn.

No government pursuing the public interest sells something without first putting it to bid. But for almost three decades Connecticut has given casino exclusivity to a couple of reconstituted Indian tribes out in the woods in the eastern part of the state and has never ascertained what anyone else might pay to operate a casino here.

The tribal casinos have been paying state government for this exclusivity -- a quarter of their slot-machine revenue, which over the years has amounted to hundreds of millions of dollars. But these royalties have been declining steadily as casinos open in neighboring states.

Meanwhile MGM, having recently opened one of those casinos just over the Massachusetts line, in Springfield, is arguing that Connecticut might do better by authorizing it to open a casino in Bridgeport. This would draw gamblers from heavily populated New York and Fairfield County, many of whom now journey to the tribal casinos two hours deeper into the countryside. These gamblers might be glad to lose their money closer to home.

Under federal law the two tribes have the right to run casinos on their reservations, and Connecticut can't change that. But the tribes do not have the right to exclusivity in the casino business in the state. Nor is the 25-percent tribute from their slot-machine revenue fixed permanently; it could be renegotiated. So now that state government is permanently broke and unable to economize, it should ask whether the tribes might be induced to pay more for their casino exclusivity or whether a different entity operating another casino or two might pay more tribute than the tribes pay.

It's telling that the supporters of the tribal casinos don't want to find out. Their argument for preserving the exclusivity of the tribes is only that the tribes have been "good partners" for state government and employ thousands of people in eastern Connecticut. But another casino operator might be just as good a partner, employ just as many people, if elsewhere in the state, and might pay more tribute.

As industrial-strength gambling, casinos are a nasty business. They pander to the worst instincts, exploit the worst weaknesses, and create terrible social problems as the price of the tribute they pay state government. They redistribute wealth from the many to the few and shift commerce from small businesses to big business. They create nothing of value. They are profitable to state government only insofar as they draw gamblers from other states, and as casinos proliferate, states increasingly will prey on their own people.

But Connecticut already has made its big policy decision by opting for casinos. This is bad enough and it should not be allowed to cancel ordinary good practice, competitive bidding for government-issued privilege.

The tribal casinos are warning state government against pursuing competition but the slot-machine tribute they pay actually gives them little leverage. For state government could cut off their traffic any time by surrounding them with casinos in, say, Bridgeport, Hartford, Torrington, Putnam and New London. A casino in Bridgeport alone might devastate them. Faced with that prospect, the tribal casinos might be willing to pay a lot more for their exclusivity, just as the state might profit more by ending their exclusivity. It's time to find out.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.

'Among those dark trees'

The Robert Frost Farm in Derry, N.H., where he wrote many of his poems, including "Tree at My Window" and "Mending Wall."

“Once, walking in Vermont, In the snow,

I followed a set of footprints

That aimed for the woods. At the verge

I could make out, ‘far in the pillared dark,’

An old creature in a huge clumsy overcoat,

Lifting his great boots through the drifts,

Going as if to die among ‘those dark trees’

Of his own country….’’

-- From “For Robert Frost,’’ by Galway Kinnell

Holiday traditions around the world

Uri Shulevitz, “Lights..., ‘‘ 2013, illustration for Dusk by Uri Shulevitz, (Margaret Ferguson Books, Farrar Straus Giroux 2013], ink and watercolor on paper, ©2013 by Uri Shulevitz. All rights reserved. ) This is in the show “Cultural Traditions: A Holiday Celebration,’’ at the Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, Mass., through Feb. 10

The museum says:

“This exhibition uses the art and stories in children's picture books to explore the similarities and differences of holiday traditions throughout the world. Cultural Traditions features over 40 original illustration works of art by six award-winning children's book illustrators. The colorful images brilliantly show the customs and traditions celebrated during Hanukkah, Christmas, Kwanzaa and the Chinese New Year.’’

Llewellyn King: The 4IR and glittery Davos

Davos conference logo.

On Jan. 22-25, 2019 in Davos-Klosters, a Swiss resort, the World Economic Forum meets. It is the glitteriest of conferences. The great and the good, the rich industrialists and the glamorous public intellectuals get together to sort out where humanity is headed.

Just to be invited is a kind of credential, a sort of honorary degree, a statement that you are world-class important.

There are politicians, CEOs, so-called thought leaders and the top non-governmental organizations, environmentalists and academics.

The world’s most important international conference it is, but does it work? At some level, yes. At others, no.

It stimulates thinking, but does it change anything? Reading the news coverage year after year you are inclined to think that a lot of the participants come to rehash things they have said before or ideas that have been with them for a long time. Others are stuck in ideological dogma and try to bend the facts to fit the dogma. Think socialist; think Republican.

Yet it has no competition. It is the place to float an idea. Probably no one floats more ideas than the man who founded the forum in 1971 and serves as its executive chairman, Klaus Schwab. He is a visionary German, who holds doctorates in economics and engineering from universities in Germany and Switzerland and a Master of Public Administration from the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard.

It was Schwab who, in 2016, launched the idea of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) by making it the subject of the forum that year and writing a book on it.

The 4IR is the concept that all of science and technology -- from biology to nanotechnology, from quantum computing to artificial intelligence -- are coming together with stunning and, at times, frightening visions of the future. A 3D printer may be making a body part while a robot is helping treat Ebola in Africa. New metals are being formulated for specific needs without human input and farms are operating with few farmers.

In that way, with all science melding and communicating, 4IR may have consequences far beyond the previous three: first, mechanical power from water and steam; then electrical power for manufacturing; and followed by computing power and communications. Now, in the age of the Internet of Things, unity of things from artificial intelligence (AI) to advanced medicine.

Enter governments. Schwab sounds a note of warning: Will they grasp and facilitate, or will they frustrate what is happening? Will they regulate when regulation is needed? In short, will the global political class comprehend that it is in the throes of something big -- bigger than it can imagine? Will it allow it to flourish while checking its Frankenstein tendencies (as with the social media companies), or will it try and subdue it or let it run to excess?

If the Davos forum has a structural weakness, it seems to me, it is that executives who are mostly middle-aged and older are dealing with ideas that have been generated by young scientists, researchers and thinkers. The average age of the people in the control room for the first manned moon launch, Apollo 11, was 28. By the time NASA had become more grown-up, the average age of the control-room operators for the first space shuttle launch was 47.

Call it the sclerosis problem. I have often wondered, as civilian, large airframe design is dominated by two companies, Boeing and Airbus, whether a young engineer with a better idea would get a hearing.

It takes new companies to pursue new ideas. Those that do not grasp the speed of change fall by the way, or are just reduced in size. Half the companies of the Dow in 2000 are not there now.

The 4IR is underway here and now -- it is not something in the out-years. A microcosm of 4IR is in the emergence of smart cities where telephones, computers, electricity and social welfare are fusing.

All of this raises the two great questions of our time: What is the future of work and can we save the environment in time? You will hear on these from Davos, no doubt.

A contradicting footnote to the idea that the young are the only big idea merchants: Klaus Schwab is 8o.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com.

At The Breakers, more revenue, no more porta potties

The Great Hall of The Breakers.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The Preservation Society of Newport County has told me that for the six months July to December (month-to-date) this year the new Welcome Center at The Breakers mansion has brought the society $350,000 more than it got in the year-earlier period at The Breakers. Back then, the center hadn’t yet opened and only memberships and tickets were for sale. The Welcome Center sells beverages and light meals. The society said that was a 10 percent increase in revenue for the society at The Breakers.

Of course, the Welcome Center aroused much neighborhood opposition, which delayed it for years. Foes were divided between those who didn’t want the new facility at all and those who wanted it, if it had to be built, across the street from The Breakers, the most famous Newport mansion.

In any case, good riddance to the port-a-potties that had served as the rest rooms for the public at The Breakers!

Refund for Vt. woman shows how 'really arbitrary' medical insurance is

Sarah Witter had to pay for a second surgery to repair her broken leg after a metal plate installed during the first surgery broke. On Friday, she got a more welcome break — a $6,358.26 refund from the hospital and her insurer.

Witter’s experience was the subject of December’s KHN-NPR “Bill of the Month” feature. She and her insurer, Aetna, had racked up $99,159 in bills from a Rutland, Vt., hospital and various medical providers after she fractured her leg in a skiing accident last February.

A surgeon at Rutland Regional Medical Center implanted two metal plates, attached to her leg bones to help them heal. Less than four months later, one of these plates broke, requiring her to have a second surgery to replace the plate. Witter, who is 63, ended up paying $18,442, mostly to the hospital, for her portion of the total cost for all her care from the hospital, doctors, emergency services and physical therapists.

After KHN contacted Aetna about these costs, the insurer noticed that Rutland Regional had billed Witter for the difference between what it charged for its services and what Aetna considered an appropriate price for the first surgery. Those additional charges are known as “balance bills” and occur when a medical provider is not in the insurer’s network and has no contract with the insurer. Rutland Regional is not in Aetna’s network. In our original story, KHN had calculated $7,410 in balance bills.

Aetna said it contacted the hospital and negotiated a compromise in which the insurer paid the hospital nearly $3,800 and the hospital waived the remainder of the charges to Witter that Aetna considered unreasonably high.

“As part of her benefits plan, Sarah’s claims in question went through a patient advocacy process that allows us to negotiate with the provider on the member’s behalf to resolve any balance billing issues,” a spokesman wrote.

Aetna said it will negotiate disputed bills for any of its customers who request assistance, and also help schedule appointments, get services authorized and deal with other non-medical complications. However, an Aetna spokesman wrote, “we weren’t fully aware of all of the bills that Sarah had received before we received them from you/her.”

Last week, Rutland Regional again declined to discuss Witter’s account. Witter said she learned of the refund during a meeting, at Rutland Regional’s invitation, with a hospital financial administrator.

“They went through all the costs and I guess treated it [the first surgery] more like it was a hospital service that was within my contract,” she said. The administrator told her they had “reprocessed” the charges from her second surgery, but that her portion of the bill did not change, she said.

“It’s good news — who doesn’t like getting money back? But I don’t quite understand,” she said. “If it’s that easy for them to reprocess this billing to get me this, then it’s obvious that everything is really arbitrary.”

One difference between the two surgeries was the first one was conducted during a crisis after Witter was admitted to the hospital through the emergency room. Balance bills in those circumstances are the most difficult to justify because patients with injuries that require immediate care, such as a heart attack or car accident, are usually taken to the closest medical facility. Patients are not in a position to figure out where the closest in-network alternative is.

Neither Witter’s hospital nor her insurer budged on her underlying complaint: that she shouldn’t have had to pay for second surgery, which cost $43,208, because one of the plates — known as a bone fixation device and manufactured by Johnson & Johnson’s DePuy Synthes — broke.

Device manufacturers generally do not offer warranties for hardware devices once they have been implanted, saying that device failure can be due to a variety of factors beyond the company’s control. Those include poor implantation by the surgeon; bones that fail to heal and subject the device to unremitting strain, causing metal fatigue; or patients who apply too much weight or movement on the bone despite instructions not to.

DePuy, which declined to comment for this story, earlier said that device failures occur in “rare circumstances.” In its instructions for surgeons, DePuy noted: “It is important to note that these implants may break at any time if they are subjected to sufficient stresses.”

Witter said her surgeon was present at her meeting at Rutland Regional and told her that “the fact the bone hadn’t completely healed yet was part of the problem.” She said she has not been able to find a contact for the device manufacturer so she can complain about it breaking.

Even after she receives her refund, Witter still will have paid $12,084 for her broken limb. Asked her advice for other patients dealing with bills they consider excessive, she said: “Don’t break your leg!’’

Chris Powell: Malloy leaves feeling the ingratitude of the great unwashed

Gov. Dannel Malloy in 2016,

From the many valedictory interviews he gave to journalists last week, Connecticut Gov. Dannel Malloy seems to be departing as bitter as Connecticut is about his eight years in office.

Malloy says he meant all along to be unpopular by always doing the right thing, apparently presuming that the public always perceives the right thing as the wrong thing. While civic engagement and literacy indeed have continued their collapse during Malloy's administration, people remain entitled to their opinion, and the governor isn't leaving them persuaded. But even as he retires as Connecticut's most disliked governor in modern times, he should be enjoying the last laugh, since he did persuade enough people when it counted, twice getting the most votes for governor.

Malloy can't acknowledge it, but there are reasons for being unhappy with him quite apart from his supposedly always doing the right thing for the ungrateful great unwashed.

During his re-election campaign he said he wouldn't raise taxes, but, returned to office, he raised them hugely. (Was lying doing the right thing?) While portraying himself as a hands-on administrator, he was brazenly indifferent to misconduct and incompetence in state government and sometimes sought to conceal it. He pandered to political correctness and proclaimed it as sound policy. A Democrat, he candidly told the government employee unions, his party's base, "I am your servant," and in this he kept his word, making his highest priority the preservation of government employee compensation.

In one interview last week the governor even attributed the defeat of some Republican state senators to their supposed bigotry against homosexuals. The senators, Malloy charged again, had voted against his nominee for chief justice of the state Supreme Court because he is gay, not for his having been part of the court's majority that presumed to erase capital punishment from the state constitution. Yet the nomination was hardly mentioned in the recent state legislative campaigns. Mostly the Democrats hung President Trump around the Republicans' necks. Malloy's charge is still hard to believe, but thank God if something in the election had nothing to do with Trump.

As with any administration, Malloy's did some good things, and his office last week issued a lovely report enumerating what he thinks they are. For example, he hastened Connecticut's move away from drug criminalization; increased medical insurance for the poor and resisted the Trump administration's malicious sabotaging of universal coverage; nearly eliminated homelessness among military veterans, and improved Bradley International Airport.

But state government remains grossly insolvent and overextended and all that good stuff was peanuts against the failures Malloy never confronted: the failure of social promotion to educate, the failure of unconditional welfare to lift people to self-sufficiency, the failure of the contentment of the government class to trickle down to taxpayers, and the failure of ever-increasing taxes and regulation to grow the private sector, which finances everything.

The better high school graduation rate Malloy often touted is deceitful when most graduates learn little and need remediation. No matter how much is spent in their name, Connecticut's cities grow poorer and more demoralized and depraved. And, perhaps the key measures, under Malloy the state's population declined relative to the rest of the country and its economy shrank.

Malloy was left a disgraceful mess and is bequeathing one to his successor. But then of course everything always could be worse.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.

Study says oyster aquaculture is good for wild oysters too

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

KINGSTON, R.I.

A fisheries researcher at the University of Rhode Island has found that oyster aquaculture operations can limit the spread of disease among wild populations. The findings are contrary to long-held beliefs that diseases are often spread from farmed populations to wild populations.

“The very act of aquaculture has positive effects on wild populations of oysters,” said Tal Ben-Horin, a postdoctoral fellow at the URI Department of Fisheries, Animal and Veterinary Sciences. “The established way of thinking is that disease spreads from aquaculture, but in fact aquaculture may limit disease in nearby wild populations.”

Working with colleagues at the University of Maryland Baltimore County, Rutgers University, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, Ben-Horin integrated data from previous studies into mathematical models to examine the interactions between farmed oysters, wild oysters, and the common oyster disease Dermo.

Their research, part of a synthesis project at the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis, was recently published in the journal Aquaculture Environment Interactions.

According to Ben-Horin, diseases are among the primary limiting factors in wild oyster populations. There are few wild populations of oysters in New England because of Dermo and other diseases, and in the Chesapeake Bay and Delaware Bay, wild oysters are managed with the understanding that most will die from disease.

Dermo is caused by a single-celled parasite that occurs naturally in the environment and proliferates in the tissue of host oysters, which spread the parasite to other oysters when they die and their parasite-infected tissues decay in the water column. But it takes two to three years for the parasite to kill the oysters. As long as the oysters are held on farms long enough to filter disease-causing parasites from the water, but not so long that parasites develop and proliferate and spread to wild oysters nearby, aquaculture operations can reduce disease in wild populations.

The disease doesn’t cause illness in humans.

“As long as aquaculture farmers harvest their product before the disease peaks, then they have a positive effect on wild populations,” Ben-Horin said. “But if they’re left in the water too long, the positive effect turns negative.”

He said that several factors can confound the positive effect of oyster aquaculture. Oyster farms that grow their product on the bottom instead of in raised cages or bags, for instance, are unlikely to recover all of their oysters, resulting in some oysters remaining on the bottom longer. This would increase rather than reduce the spread of the disease.

“But when it’s done right, aquaculture can be a good thing for wild oyster populations,” Ben-Horin said. “Intensive oyster aquaculture, where oysters are grown in cages and growers can account for their product and remove it on schedule, is not a bad thing for wild populations.”

The study’s findings have several implications for the management of wild and farmed oysters. Ben-Horin recommends establishing best management practices for the amount of time oysters remain on farms before harvest. He also suggests that aquaculture managers consider the type of gear — whether farmers hold oysters in cages and bags or directly on the seabed — when siting new oyster aquaculture operations near wild oyster populations.

The next step in Ben-Horin’s research is to gain a better understanding of how far the Dermo parasite can spread by linking disease models with ocean circulation models.

“Everything that happens in the water is connected,” he said. “There’s a close relationship between the wild and farmed oyster populations and their shared parasites. Sometimes ecosystem level effects are overlooked, but in this case they’re front and center.”

Study co-author Ryan Carnegie, of the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, said this research is an important contribution to the dialogue about the interactions between shellfish aquaculture and the environment.

“It’s critical that we fully appreciate how aquaculture fits in the ecology of marine systems, and this study provides new perspective on this,” he said. “It highlights an important ecological benefit that intensive shellfish aquaculture may provide. This should help bolster the well-justified public perception of shellfish aquaculture as a green industry worthy of their support, which this industry must have if it is to grow.”

![Uri Shulevitz, “Lights..., ‘‘ 2013, illustration for Dusk by Uri Shulevitz, (Margaret Ferguson Books, Farrar Straus Giroux 2013], ink and watercolor on paper, ©2013 by Uri Shulevitz. All rights reserved. ) This is in the show “Cultural Traditions: A…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/561446cce4b094b629347f8d/1546012153195-61SCLZ7RYMS201I389FQ/lights.jpg)