Where abnormal is normal

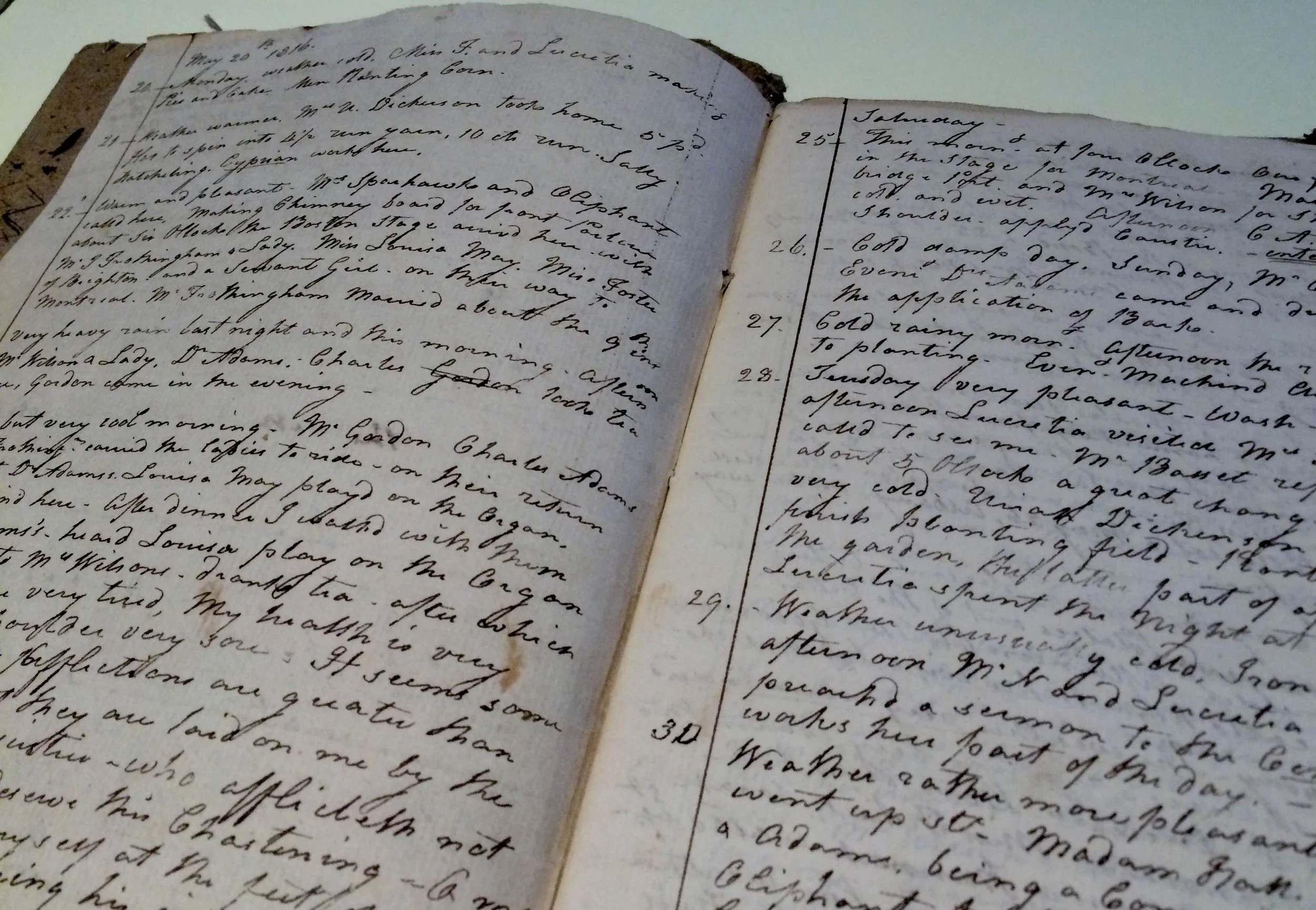

1816 was called “The Year Without a Summer” in New England because of the effects of a huge volcanic eruption in Indonesia, which blocked much of the sun’s heating power on Earth. Hannah Dawes Newcomb, of Keene, N.H., kept a diary (above) with short daily reports on her everyday life. Starting around May, her comments reflected the strange weather patterns of that year, which were disastrous for agriculture in North America, Europe and elsewhere.

“Freak weather conditions are standard in New England. In fact, The Old Farmer’s Almanac was vaulted on the road of success by predicting “snow and ice” for July 13, 1816. When it actually did snow on Boston that day, most of Robert B. Thomas’s 1,500 competitors faded into oblivion.’’

—Judson D. Hale, now former editor of Yankee magazine and The Old Farmer’s Almanac, writing in Arthur Griffin’s New England: The Four Seasons (1980).

Expand and contract

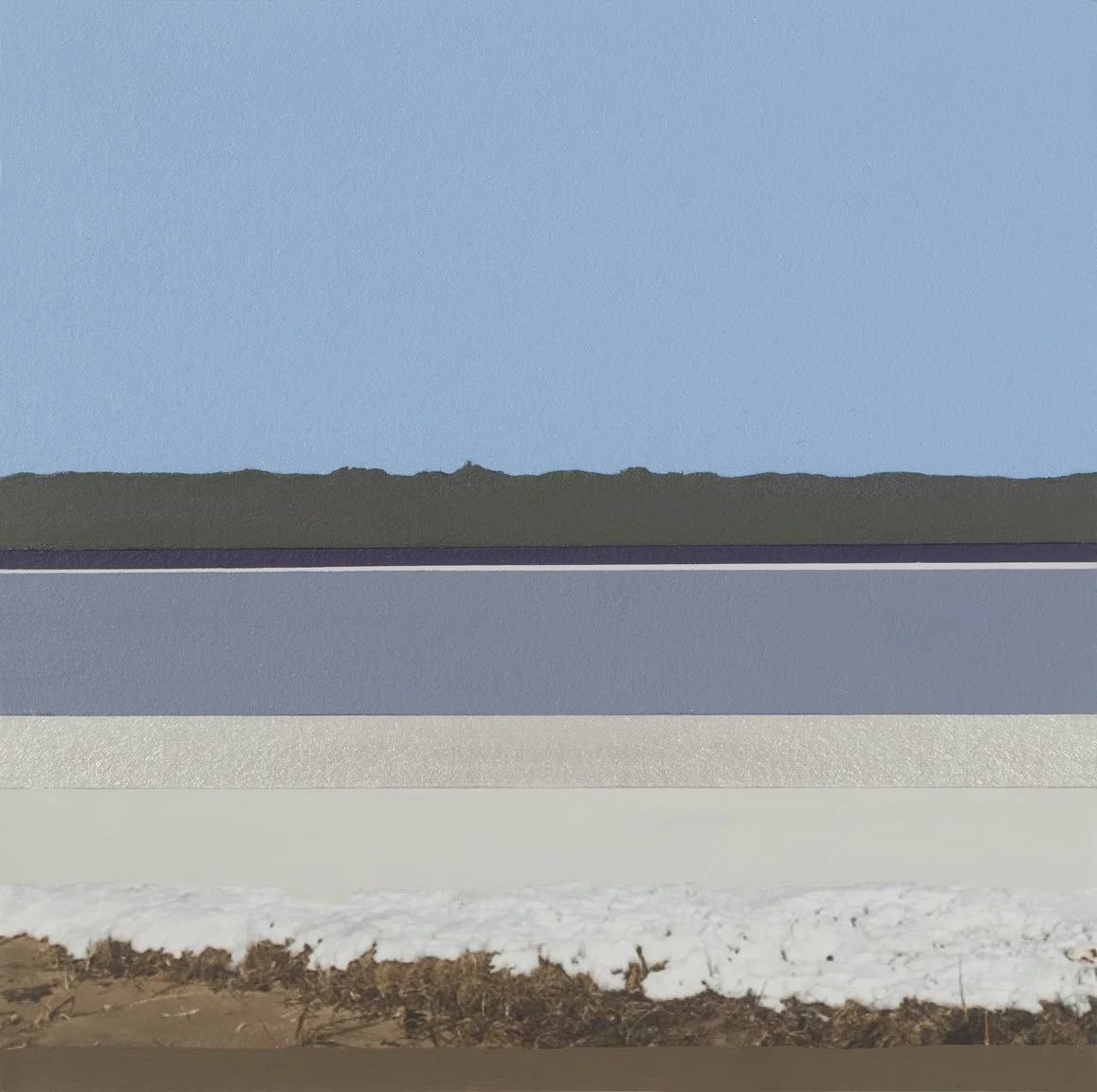

“Edge of Snow” (acrylic and photo on paper), by Cape Cod-based Jane Lincoln, at Kingston Gallery, Boston.

A baby Hercules of a college

Fayerweather Hall at Amherst College. Founded in 1821, the college, in Amherst, Mass., developed from Amherst Academy, first established as a secondary school. The college was originally suggested as an institution to succeed Williams College (founded in 1793), in Williamstown, Mass., which was struggling to stay open but later thrived. The two rather similar elite colleges remain friendly rivals.

“The infant {Amherst} college is an Infant Hercules. Never was so much striving, outstretching, & advancing in a literary cause as is exhibited here.’’

— Ralph Waldo Emerson (1823)

Founded in 1821, Amherst College, in Amherst, Mass., developed from Amherst Academy, first established as a secondary school. The college was originally suggested to succeedWilliams College, in Williamstown, Mass., which was struggling to stay open but later thrived.

xxx

“You can always tell a Harvard man, but you can’t tell him much.’’

— Anonymous

The joy and pain of shrinkage

Big enough

— Photo by Cavajunky

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Many people at the end of the year reflect on whether they should make a major life change. This might include simplifying by downsizing where they live.

So I recommend Dr. Edward Iannuccilli’s latest book of essays, Essays on the Art and Pain of Downsizing. (He’s a friend, but no, I get no kickbacks for this plug.)

Of course, many older people, such as Dr. Iannuccilli, who lives in beautiful Bristol, R.I., downsize in part because of their stage of life. But there are good reasons for others to do so. You save on fuel, electricity, taxes and insurance and you’re disciplined to get rid of stuff, which can feel liberating. (Do some people have so much stuff that it acts as insulation, saving fuel in the winter?)

In 1980, the median size of a new house in the U.S. was 1,595 square feet. That ballooned to 2,386 square feet by 2018, with fewer people living in these houses. Obviously, the bigger the house, the bigger the purchase price and maintenance costs; the latter tend to be alarmingly unpredictable.

Town hall and Civil War memorial in Bristol, R.I.

Individual terror

“Brake Run Helix,’’ by EJ Hill, at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MassMOCA), North Adams., Mass., through January 2024.

The museum explains:

“In ‘Brake Run Helix,’ Hill inverts the experience of riding a roller coaster, transforming it from a shared ritual of joy and terror to an individual performance: only one person may ride the roller coaster, Brava!, at a time. Brava!’s single cart emerges from behind a two-story velvet stage curtain, moves across the coaster’s pink tracks, and ultimately comes to rest on the wooden stage, while onlookers observe from below. Visitors can see the roller coaster activated by riders throughout the day. Are you interested in riding? The line starts here.’’

French-Canadians at New Year's

L'Église du Précieux Sang (also known as The Church of the Precious Blood) has served the large French-Canadian population of Woonsocket, R.I., area since the 1870’s.

The Fleur de Lis, the symbol of French Canada.

From a New England Historical Society article on French Canadians in New England:

“The reveillon is a long, late dinner preceding a holiday. Tourtiere is central to the meal. The celebrated meat pie, cooked and eaten during the shortest days of winter, often accompanies traditional Franco-American foods such as peas or pea soup, head cheese, croquignoles and ragout.

“During the first half of the 19th century, when the first wave of immigrants arrived, New Year’s Day exceeded Christmas in importance. On January 1, Franco-Americans exchanged small gifts, and children found presents under the tree or near the manger in the parlor. Sometimes their parents told them the presents came from le Pere Noel (a skinny version of Santa Claus) or l’Enfant Jesus.’’

Chris Powell: Housing with steeples; report on where you are

— Photo by Andrea Farias

MANCHESTER, Conn.

With an extension of one of his epidemic-related emergency orders, Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont has saved for another six months the Pacific House homeless shelter in Danbury, just days before it would have had to close because of the expiration of his previous order and the city zoning board's disgraceful refusal to approve the facility.

Thus Connecticut has just barely avoided being shamed by the expulsion of dozens of people into the dead of winter during Christmas week, what would have been a grotesque re-enactment of there being “no room at the inn” as there famously was no room two millennia ago.

But of course the shame may be only postponed. While in the last few years state government sharply reduced homelessness, in recent months it has been rising again as the economy has weakened, inflation has soared, and the poorest and most troubled and demoralized have been most battered.

Getting them out of the cold and into a safe, secure and warm environment with access to medical care and encouragement is again an urgent obligation for state government, even as practically every day state government touts its comfortable financial condition and bestows money on far less compelling projects.

With the new session of the General Assembly convening in a few days, the governor's extended order preserving the Danbury shelter should be only the start of an emergency program to establish more shelters and supportive housing facilities throughout the state and to exempt them from municipal zoning regulations.

With organized religion declining, Connecticut abounds in empty church buildings, some of which are being offered for sale and repurposing, even if repurposing a building with a steeple may create a permanent incongruity for the new occupants.

Organized religion's decline is not just a decline in theology and doctrine but also a decline in community, which can be seen in the worsening social disintegration generally. While in the old days religion could be politically divisive, in recent years in Connecticut it has stressed decency more than doctrine and so should be much missed.

In pursuit of that decency maybe state government should lease some of those former churches for use as shelters and supportive housing, and maybe the neighbors, in danger of being rebuked by the antique architecture for any lack of hospitality, would'’t object.

xxx

A congressional district on Long Island that includes parts of the New York City borough of Queens and neighboring Nassau County on Nov. 8 elected Republican George Santos to Congress. His resume, the New York Times reported last week, is completely phony.

The representative-elect turns out not to be what he claimed during his campaign -- a great scholar with a brilliant record in the financial industry -- but a grifter who fled criminal prosecution in Brazil and has been evicted from apartments in New York for not paying rent.

Of course he should resign his office, and if he refuses, the House of Representatives should expel him. There should be a new election in his district. But even then the country should expect a lot more of this fraud, for it is the consequence of the decline of journalism, which in turn is a consequence of the decline of literacy and civic engagement throughout the country.

After all, creditable as the Times' exposure of the grifter is, where were the newspaper and other news organizations purporting to serve Queens and Nassau County before his election?

Of course The Times was tediously savaging Donald Trump long after his presidential term had ended, just as most major news organizations were doing. But The Times declines to cover its own neighborhood seriously.

Connecticut has no cause to snicker here. While all the members of the state's congressional delegation who were just re-elected have had long careers in public life and have been fully vetted, as Governor Lamont, also just re-elected, has been, the three new state constitutional officers remain almost completely unknown, and the backgrounds of many new state legislators just elected have not been scrutinized independently by vigorous journalism. For there isn't much left.

The new constitutional officers and state legislators may turn out all right. But there is no longer much insurance anywhere against disasters like the one in New York.

Chris Powell (CPowell@JournalInquirer.com) is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Blue: ‘Strength and calm’

“Blue Silence” (acrylic on canvas), by Reading, Mass.-based painter Jo-Anne Boback, in the group show “Looking Forward,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, Jan. 13-29.

She explains:

"I did this piece after I lost my dad, who had the deepest blue eyes! As it is with most of us, the color blue represents calm while evoking strength, stability and security; think of the ocean and the sky."

Downtown Reading.

The Parker Tavern, built in 1694, is the oldest surviving building in Reading. It was owned and operated by Ephraim Parker, who was the great-grandson of Thomas Parker, who was one of Reading’s founders and probably named the town, after Reading, England. The tavern is now a museum.

Samantha Young: Poorly trained, politically connected coroners

“Autopsy” (1890), by Enrique Simonet

“There are some really egregious conflicts of interest that can arise with coroners.’’

— Justin Feldman, a visiting professor at Harvard University’s FXB Center for Health and Human Rights

When a group of physicians gathered in Washington state for an annual meeting, one made a startling revelation: If you ever want to know when, how — and where — to kill someone, I can tell you, and you’ll get away with it. No problem.

That’s because the expertise and availability of coroners, who determine cause of death in criminal and unexplained cases, vary widely across Washington, as they do in many other parts of the country.

“A coroner doesn’t have to ever have taken a science class in their life,” said Nancy Belcher, chief executive officer of the King County Medical Society, the group that met that day.

Her colleague’s startling comment launched her on a four-year journey to improve the state’s archaic death-investigation system, she said. “These are the people that go in, look at a homicide scene or death, and say whether there needs to be an autopsy. They’re the ultimate decision-maker,” Belcher added.

Each state has its own laws governing the investigation of violent and unexplained deaths, and most delegate the task to cities, counties, and regional districts. The job can be held by an elected coroner as young as 18 or a highly trained physician appointed as medical examiner. Some death investigators work for elected sheriffs who try to avoid controversy or owe political favors. Others own funeral homes and direct bodies to their private businesses.

Overall, it’s a disjointed and chronically underfunded system — with more than 2,000 offices across the country that determine the cause of death in about 600,000 cases a year.

“There are some really egregious conflicts of interest that can arise with coroners,” said Justin Feldman, a visiting professor at Harvard University’s FXB Center for Health and Human Rights.

Belcher’s crusade succeeded in changing some aspects of Washington’s coroner system when state lawmakers approved a new law last year, but efforts to reform death investigations in California, Georgia and Illinois have recently failed.

Rulings on causes of death are often not cut-and-dried and can be controversial, especially in police-involved deaths such as the 2020 killing of George Floyd. In that case, Minnesota’s Hennepin County medical examiner ruled Floyd’s death a homicide but indicated a heart condition and the presence of fentanyl in his system may have been factors. Pathologists hired by Floyd’s family said he died from lack of oxygen when a police officer kneeled on his neck and back.

In a recent California case, the Sacramento County coroner’s office ruled that Lori McClintock, the wife of Congressman Tom McClintock, died from dehydration and gastroenteritis in December 2021 after ingesting white mulberry leaf, a plant not considered toxic to humans. The ruling triggered questions by scientists, doctors and pathologists about the decision to link the plant to her cause of death. When asked to explain how he made the connection, Dr. Jason Tovar, the chief forensic pathologist who reports to the coroner, said he reviewed literature about the plant online using WebMD and Verywell Health.

The plant is generally considered safe and is used as an herbal remedy for a variety of ailments. Her death highlights the potential dangers of dietary supplements.

The various titles used by death investigators don’t distinguish the discrepancies in their credentials. Some communities rely on coroners, who may be elected or appointed to their offices, and may — or may not — have medical training. Medical examiners, on the other hand, are typically doctors who have completed residencies in forensic pathology.

In 2009, the National Research Council recommended that states replace coroners with medical examiners, describing a system “in need of significant improvement.”

Massachusetts was the first state to replace coroners with medical examiners statewide, in 1877. As of 2019, 22 states and the District of Columbia had only medical examiners, 14 states had only coroners, and 14 had a mix, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The movement to convert the rest of the country’s death investigators from coroners to medical examiners is waning, a casualty of coroners’ political might in their communities and the additional costs needed to pay for medical examiners’ expertise.

The push is now to better train coroners and give them greater independence from other government agencies.

“When you try to remove them, you run into a political wall,” said Dr. Jeffrey Jentzen, a former medical examiner for the city of Milwaukee and the author of “Death Investigation in America: Coroners, Medical Examiners, and the Pursuit of Medical Certainty.”

“You can’t kill them, so you have to help train them,” he added.

There wouldn’t be enough medical examiners to meet demand anyway, in part because of the time and expense it takes to become trained after medical school, said Dr. Kathryn Pinneri, president of the National Association of Medical Examiners. She estimates there are about 750 full-time pathologists nationwide and about 80 job openings. About 40 forensic pathologists are certified in an average year, she said.

“There’s a huge shortage,” Pinneri said. “People talk about abolishing the coroner system, but it’s really not feasible. I think we need to train coroners. That’s what will improve the system.”

Her association has called for coroners and medical examiners to function independently, without ties to other government or law enforcement agencies. A 2011 survey by the group found that 82 percent of the forensic pathologists who responded had faced pressure from politicians or the deceased person’s relatives to change the reported cause or manner of death in a case.

Dr. Bennet Omalu, a former chief forensic pathologist in California, resigned five years ago over what he described as interference by the San Joaquin County sheriff to protect law enforcement officers.

“California has the most backward system in death investigation, is the most backward in forensic science and in forensic medicine,” Omalu testified before the state Senate Governance and Finance Committee in 2018.

San Joaquin County has since separated its coroner duties from the sheriff’s office.

The Golden State is one of three states that allow sheriffs to also serve as coroners, and all but 10 of California’s 58 counties combine the offices. Legislative efforts to separate them have failed at least twice, most recently this year.

AB 1608, spearheaded by state Assembly member Mike Gipson (D-Carson), cleared that chamber but failed to get enough votes in the Senate.

“We thought we had a modest proposal. That it was a first step,” said Robert Collins, who advocated for the bill and whose 30-year-old stepson, Angelo Quinto, died after being restrained by Antioch police in December 2020.

The Contra Costa County coroner’s office, part of the sheriff’s department, blamed Quinto’s death on “excited delirium,” a controversial finding sometimes used to explain deaths in police custody. The finding has been rejected by the American Medical Association and the World Health Organization.

Lawmakers “didn’t want their names behind something that will get the sheriffs against them,” Collins said. “Just having that opposition is enough to scare a lot of politicians.”

The influential California State Sheriffs’ Association and the California State Coroners Association opposed the bill, describing the “massive costs” to set up stand-alone coroner offices.

Many Illinois counties also said they would shoulder a financial burden under similar legislation introduced last year by state Rep. Maurice West, a Democrat. His more sweeping bill would have replaced coroners with medical examiners.

Rural counties, in particular, complained about their tight budgets and killed his bill before it got a committee hearing, he said.

“When something like this affects rural areas, if they push back a little bit, we just stop,” West said.

Proponents of overhauling the system in Washington state — where in small, rural counties, the local prosecutor doubles as the coroner — faced similar hurdles.

The King County Medical Society, which wrote the legislation to divorce the two, said the system created a conflict of interest. But small counties worried they didn’t have the money to hire a coroner.

So, lawmakers struck a deal with the counties to allow them to pool their resources and hire shared contract coroners in exchange for ending the dual role for prosecutors by 2025. The bill, HB 1326, signed last year by Democratic Gov. Jay Inslee, also requires more rigorous training for coroners and medical examiners.

“We had some hostile people that we talked to that really just felt that we were gunning for them, and we absolutely were not,” Belcher said. “We were just trying to figure out a system that I think anybody would agree needed to be overhauled.”

Samantha Young is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Samantha Young: syoung@kff.org, @youngsamantha

Visit in a storm

At the Cape Cod National Seashore.

“What are springs and waterfalls? Here is the spring of springs, the waterfall of waterfalls. A storm in the fall or winter is the time to visit it; a light-house or a fisherman's hut the true hotel. A man may stand there and put all America behind him.’’

— Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862), in Cape Cod

Provincetown in Thoreau’s lifetime.

Don Pesci: What is a woman?

Detail from Johannes Vermeer’s (1632-1675) “Portrait of a Woman With a Pearl Earring’’

VERNON

The absurdities of post-modern life press upon us like some finely tuned, automatically updated incubus.

Awaiting approval for her nomination to be on the U.S. Supreme Court, current Associate Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson was asked, by a woman legislator, as it happened, to “define a woman.”

She demurred, modestly pleading that she was no biological scientist.

But the question, not entirely innocently presented, begs to be answered. When I put the question to two politically unbiased women, both agreed that a “woman” may be defined as one who receives flowers from a male admirer.

I cannot remember ever having received a bouquet of flowers from a woman. I have given out a few bouquets of flowers to women I admire and cannot recall ever having sent a bouquet to a man.

So far, so good.

Naturally, there are exceptions, but exceptions generally prove the rule, except in rare cases when it becomes politically expedient to make a rule of an exception. This nearly always ends in disaster. Both rules and definitions should be generally accepted by what the ordinary run of humanity would regard as objective and dispassionate observers.

My grandfather – Carlo “The Fox” – stands out as an exception … sort of.

One day, when I was storming through my reckless teens, “The Old Man,” as everyone affectionately called Grandfather Carlo, showed up at the Pesci homestead clutching a fist full of Bennies, which he pressed upon his daughter Rose, my mother.

This took her, the immediate family, the extended family and, for all I know, any relatives in Italy who knew Carlo well, by surprise. Carlo The Fox was abstemious when it came to money, not exactly a Scrooge, but close.

“What’s this for?” my mother asked.

Sitting by the kitchen window, the early morning sun bathing his weather ravaged face, he explain that he was old.

My mother nodded assent, a question mark mysteriously appearing on her forehead.

He sipped his “coffee royal” -- steaming hot black coffee, just short of an espresso, never to be diluted with anisette -- while his daughter waited patiently for him to explain why on this day he had abandoned a lifetime of penny-pinching. To be sure, he had in the past made rare exceptions to his inflexible habit, most often when he was engaged in card games for money, not sport. In one game, he had won, and then lost a portion of Elm Street in Windsor Locks, Conn.

My mother groaned when she discovered this. “We could have been rich,” she observed.

Rose waited him out. And, sipping his coffee, to which was added a knuckle of Jack Daniels, it came bubbling out of him like a freshet of living water.

He did not expect to live too many years longer, most of his friends were dead, he could not – dare not! – trust anyone with the mission he assigned my mother. When he died – unfortunately the fate of all men, rich, poor and moderately well-off – she was to take the money and with it buy flowers for his wake and funeral. He did not want to go out un-flowered or unrespected by the few of his friends who might survive him.

My mother, who had gotten used to her father’s abstemiousness -- though he had made an exception in the case of coffee-royals and Italico Classico Ammezzato cigars, a refined blend of Italian and Kentucky, he was pleased to note -- was touched and instantly accepted the commission. When Carlo The Fox died, his body was smothered in flowers.

So here was a woman buying flowers for a man – to be sure, with the man’s money – an exception that proves the rule.

Few of us are linguistic scientists or professors of grammar, morphology, syntax, phonology, phonetics, and semantics. We are not Noam Chomsky, a reliable guide when he does not meander outside his discipline. The definition of a woman as “one who receives flowers from an admiring gentleman” is serviceable and practical, allowing for arcane exceptions that, given the postmodern bad habit of redefining foundational characteristics, does not touch embarrassing and painful questions such as “Should elementary school libraries stock Gender Queer and Lawn Boy?”

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

Toll bridge over the Connecticut River, c. 1910.

Light and ‘the spirit of place’

“Marsh River Reflections” (oil on braced panel), by Janis Sanders, at Alpers Fine Art, Rockport, Mass.

Mr. Sanders’s Web site says:

“Janis Sanders is an accomplished oil painter, who has won awards for his unique painting style. His work is done with a palette knife, often en plein air. He melds elements of American Realism with Modernism/Impressionism for a dramatically contemporary visual result. He works to convey light glancing on a surface to communicate the spirit of place of each singular American setting. He paints muscularly, enthusiastically, vigorously outdoors throughout the year, from the rugged coast of Maine to the verdant marshes of the Massachusetts North Shore, to the quiet sand dunes of the Outer Cape. Janis is represented in galleries throughout New England as well as Sante Fe.’’

Just a few months

“Winter Landscape,’’ by Caspar David Friedrich

“When the cold comes to New England it arrives in sheets of sleet and ice. In December, the wind wraps itself around bare trees and twists in between husbands and wives asleep in their beds. It shakes the shingles from the roofs and sifts through cracks in the plaster. The only green things left are the holly bushes and the old boxwood hedges in the village, and these are often painted white with snow. Chipmunks and weasels come to nest in basements and barns; owls find their way into attics. At night, the dark is blue and bluer still, as sapphire of night.’’

― Alice Hoffman (born 1952), novelist, in Here on Earth. She lives in Boston.

Boston area’s ‘Golden Semicircle’

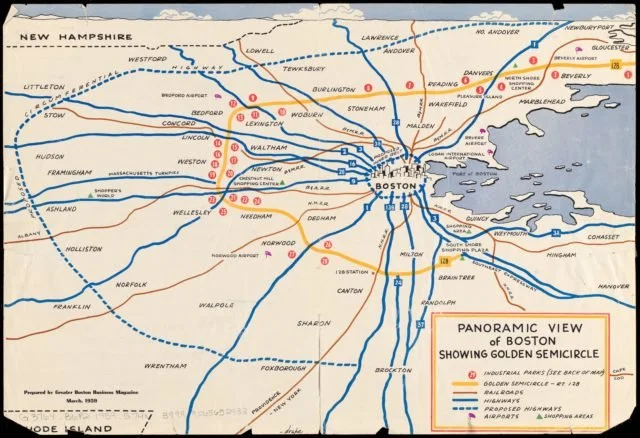

A 1959 issue of Greater Boston Business Magazine contained a two-page map of the region’s “Golden Circle” showing industrial parks and shopping centers springing up along Route 128, which was being completed.

The building of Route 128 created was the nation’s first great high-technology region, fueled by the university complex in and around Boston. It was something of a model for North Carolina’s Research Triangle and what came to be called Silicon Valley in the San Francisco-San Jose area in California.

—Image courtesy of the Boston Public Library/Digital Commonwealth |

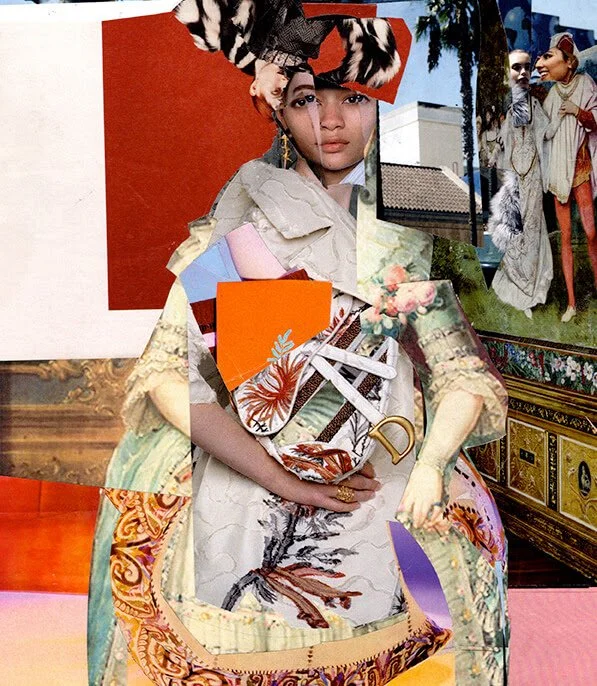

Reinterpreting portraiture

“Doña-Maria” (collage on archival paper), by Rodriguez Calero, in the show “Self, assembled,’’ at the Flinn Gallery, Greenwich, Conn., through Feb. 1.

— Photo courtesy of Flinn Gallery.

The gallery explains that the show is a collection of collages that "probe the nature of identity" by "appropriating, fragmenting, layering, and unexpectedly juxtaposing images derived from personal and collective histories." Rodriguez Calero, Kevin Hetzel and Jason Noushin use diverse skills and experiences to create artwork that asks us to rethink how we interpret portraiture.

Finally, no climbing

Enthusiasm for skiing spread rapidly in New England in the years before America’s entry in World War II. The arrival of rope tows, usually connected to truck engines, was one reason, as at this farm in Lisbon, N.H. , in 1936. Farm Security Administration photographer Marion Post Wolcott took pictures of local teenagers skiing on Dickinson’s farm in March 1939. She explained:

“On Saturday afternoon many high school students come to Dickinson’s farm to ski. Mr Dickinson built a ski tow on his farm three years ago at a cost of one thousand dollars. This is the first year he had made any money {from the ski business} although business is increasing rapidly now. He has a small dairy farm and until the hurricane last year destroyed his entire grove of maple trees, he made and sold maple syrup.”

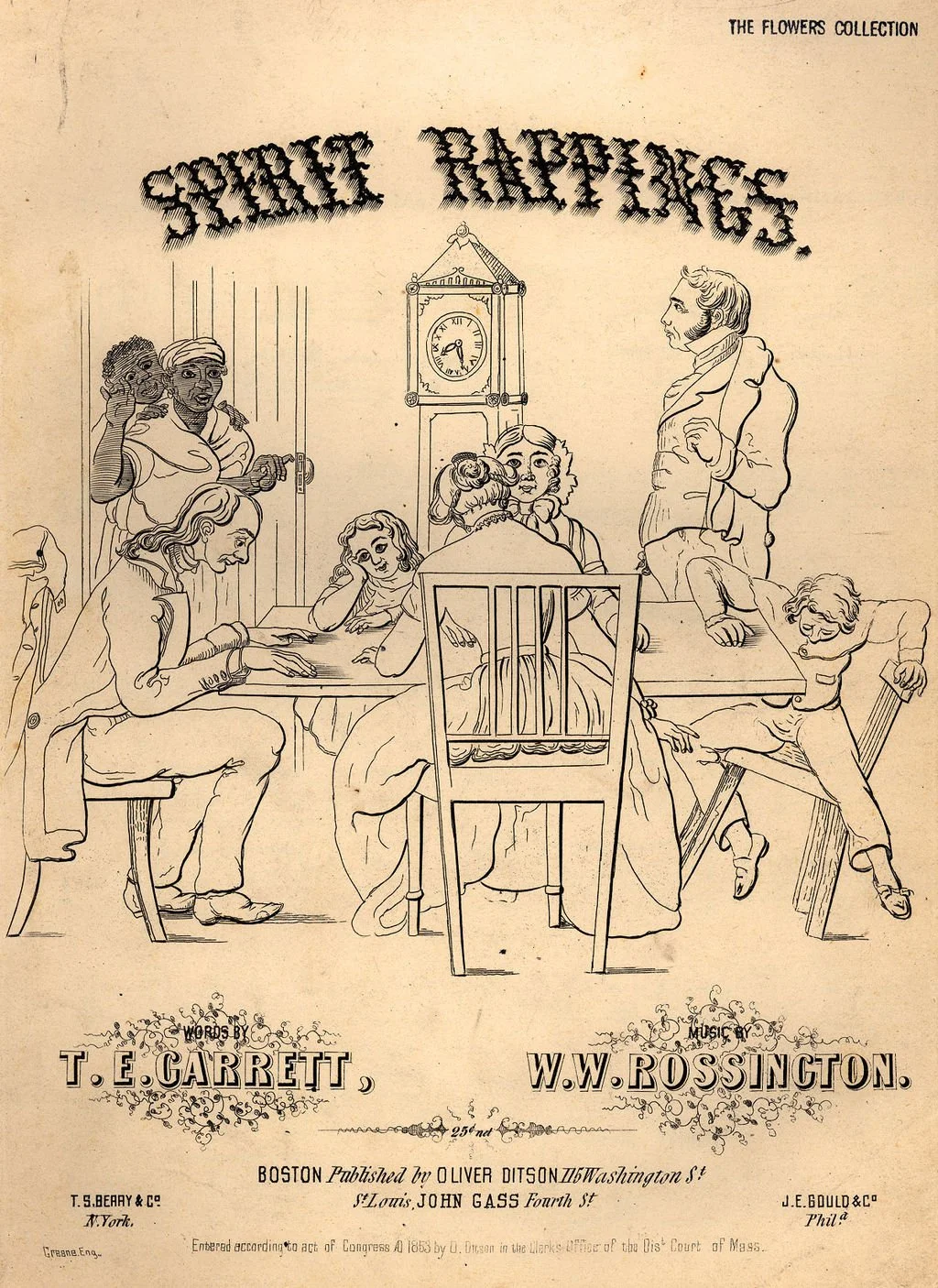

Calling in company

By 1853, when the popular song “Spirit Rappings” was published, Spiritualism was an object of intense curiosity in New England.

“For a night when sleep eludes you, I have,

At last, found the formula. Try to summon

All those ever known who are dead now, and soon

It will seem they are there in your room, not chairs enough

For the party, or standing space even….’’

From “Better Than Counting Sheep,’’ by Robert Penn Warren (1905-1989), celebrated poet, novelist and critic, a Kentucky native, he lived the latter part of his life in Connecticut and Vermont

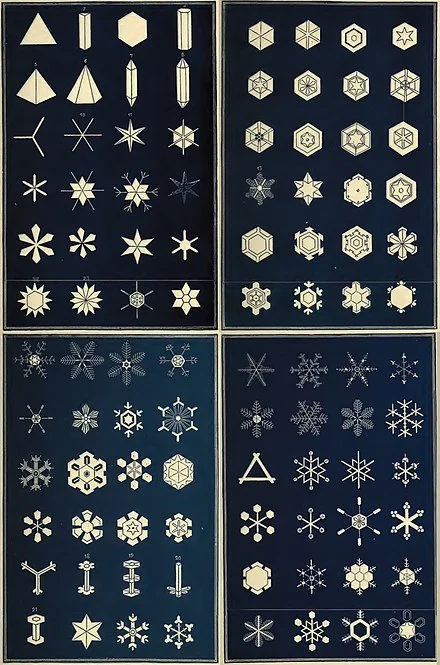

‘Creative genius in the air’

Early classification of snow crystals by Israel Perkins Warren (1814-1892), New England author, journalist and Congregational minister.

Louis Prang may have introduced the first American Christmas cards, such as this one. He fled German disorder in 1848 and came to Boston. Prang went to work for an engraver, eventually setting up his own lithography shop. He started producing Christmas cards in New England in the 1870s.

“All praise to winter, then, was Henry's feeling. Let others have their sultry luxuries. How full of creative genius was the air in which these snow-crystals were generated. He could hardly have marveled more if real stars had fallen and lodged on his coat. What a world to live in, where myriads of these little discs, so beautiful to the most prying eye, were whirled down on every traveler's coat, on the restless squirrel's fur and on the far-stretching fields and forests, the wooded dells and mountain-tops -- these glorious spangles, the sweepings of heaven's floor.”

― Van Wyck Brooks (1886-1963), literary critic and historian, in his book The Flowering of New England, 1815-1865. The “Henry’’ refers to Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862).

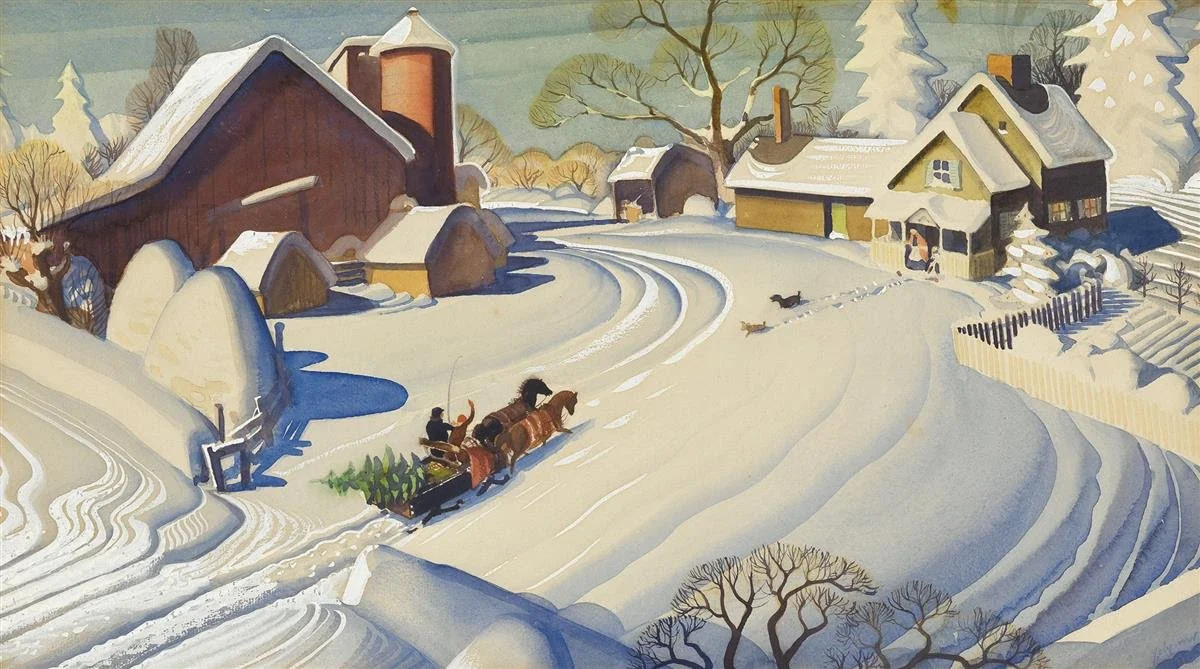

Unless you can’t find an aluminum one

”The Perfect Christmas Tree” (1930 watercolor and gouache on paper), by John Clymer (1907-1989), in This Week magazine, Dec. 24, 1939. at the National Museum of American Illustration, Newport, R.I.

— Copyright 2022, the National Museum of American Illustration

Mr. Clymer established his career in the artists center of Westport, Conn., whose Campo Beach is seen here.

Llewellyn King: 2022’s biggest crises will be 2023’s, too

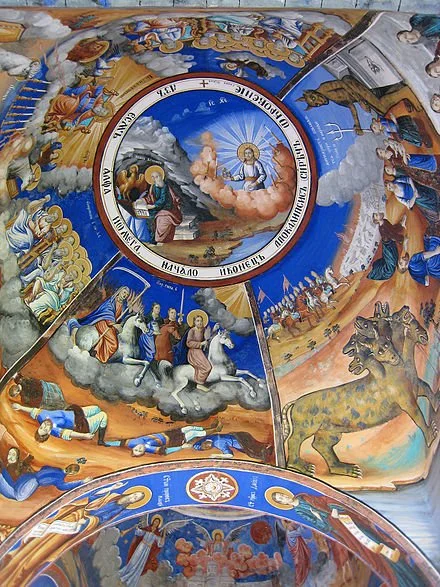

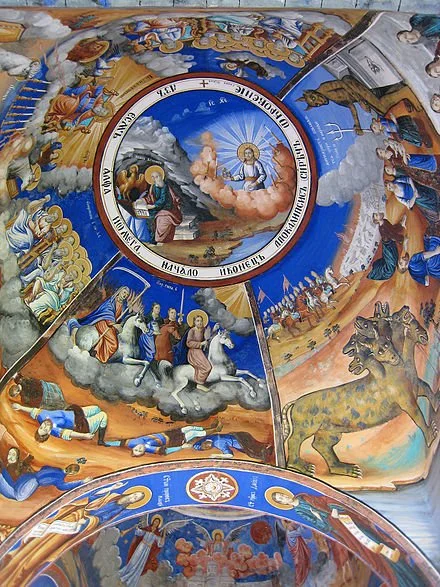

The Apocalypse, depicted in Orthodox Christian traditional fresco scenes in Osogovo Monastery, North Macedonia.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

There are no new years, just new dates.

As the old year flees, I always have the feeling that it is doing so too fast; that I haven’t finished with it, even though the same troubles are in store on the first day of the new year.

Many things are hanging over the world this transition. None is subject to quick fixes.

Here are the three leading, intractable mega-issues:

First, the war in Ukraine. There is no resolution in sight as Ukrainians survive as best they can in the rubble of their country, subject to endless pounding by Russian President Vladimir Putin. It is as ugly and flagrant an aggression as Europe has seen since days of Hitler and Stalin.

Eventually, there will be a political solution or a Russian victory. Ukraine can’t go on for very long, despite its awesome gallantry, without the full engagement of NATO as a combatant. It isn’t possible that it can wear down Russia with the latter’s huge human advantage and Putin’s dodgy friends in Iran and China.

One scenario is that after winter has taken its toll on Ukraine, and the invading forces, a ceasefire-in-place is declared, costing Ukraine territory already held by Russia. This will be hard for Kyiv to accept -- huge losses and nothing won.

Kyiv’s position is that the only acceptable borders are those that were in place before the Russian invasion of Crimea in 2014. That almost certainly would be too high a price for Russia.

Henry Kissinger, writing in the British magazine “The Spectator,” has proposed a ceasefire along the borders that existed before the invasion of last February. Not ideal but perhaps acceptable in Moscow, especially if Putin falls. Otherwise, the war drags on, as does the suffering, and allies begin to distance themselves from Ukraine.

A second huge, continuing crisis is immigration. In the United States, we tend to think that this is unique to us. It isn’t. It is global.

Every country of relative peace and stability is facing surging, uncontrolled immigration. Britain pulled out of the European Union partly because of immigration. Nothing has helped.

This year 504,000 immigrants are reported to have made it to Britain. People crossing the English Channel in small boats, with periodic drownings, has worsened the problem.

All of Europe is awash with people on the move. This year tens of thousands have crossed the Mediterranean from North Africa and landed in Malta, Spain, Greece and Italy. It is changing the politics of Europe: Witness the new right-wing government in Italy.

Other migrant masses are fleeing eastern Europe for western Europe. Ukraine has a migrant population in the millions seeking peace and survival in Poland and other nearby countries.

The Middle East is inundated with refugees from Syria and Yemen. These millions follow a pattern of desperate people wanting shelter and services, but eventually destabilizing their host lands.

Much of Africa is on the move. South Africa has millions of migrants, many from Zimbabwe, where drought has worsened chaotic government, and economic activity has come to a halt because of electricity shortages.

Venezuelans are flooding into neighboring Latin American countries, and many are journeying on to the southern border of the United States.

The enormous movement of people worldwide in this decade will have long-lasting effects on politics and cultures. Conquest by immigration is a fear in many places.

My final mega-issue is energy. Just when we thought the energy crisis that shaped the 1970s and 1980s was firmly behind us, it is back -- and is as meddlesome as ever.

Much of what will happen in Ukraine depends on energy. Will NATO hold together or be seduced by Russian gas? Will Ukrainians survive the frigid winter without gas and often without electricity? Will the United States become a dependable global supplier of oil and gas, or will domestic climate concerns curb oil and gas exports? Will small modular reactors begin to meet their promise? Ditto new storage technologies for electricity and green hydrogen?

Energy will still be a driver of inflation, a driver of geopolitical realignments, and a driver of instability in 2023.

Add to worsening weather and the need to curb carbon emissions, and energy is as volatile, political, and controversial as it has ever been. And that may have started when English King Edward I banned the burning of coal in 1304 to curb air pollution in the cities.

Happy New Year, anyway.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.