A temporary treatment for SAD

“Christmas Cactus, Winter Light” (oil on panel), by Yvonne Troxell Lamothe, in the show “Beyond the Curve,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, Dec. 3-Jan. 16

The gallery says:

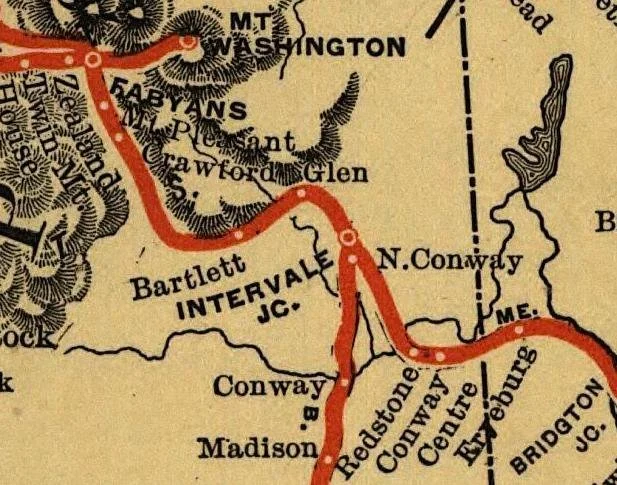

“{Ms. Lamothe} has been producing both oil paintings and watercolors mainly completed en plein air. Yvonne embraces her roots in New England. Finding intrigue with marshlands, woodlands and glorious vistas of Quincy, Mass., and Greater Boston’s South Shore, where she now lives and her cabin in Ossipee, N.H., and the White Mountains where she finds solitude gives her ample inspiration for painting. Trips to the Maine coast and Vermont offer great additional and endless places to stop and paint. It is no wonder that such a range of American painters have found their way here to New England. Among her favorites are Marsden Hartley, Lois Dodd and Milton Avery. Her paintings show close connections to the earth because of the unusual perspectives that she finds to insure a closeness to her subject. Color is of essence to Yvonne and this joy can be felt in her work. And, of course, as the earth becomes more threatened, she hopes her paintings will inspire others to take time to appreciate and celebrate our planet.’’

View of Marina Bay and Boston across Quincy Bay from Wollaston Beach, in Quincy

Center Ossipee in 1915

CVS wants stores with affluent customers — obviously; many others might be closed

In Coventry, Conn.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Woonsocket, R.I.-based CVS plans to close 10 percent of its stores. This may well be because of intensifying competition from Amazon, Walmart, etc., and the proliferation of cheap stores such as Dollar General that plan big expansions in offerings of health-related stuff. And the mail-order drug business will keep expanding.

Which stores will they close around here? I’ll bet they’ll be in poorer neighborhoods, with fewer well-insured people. CVS stores in affluent neighborhoods, such as Wayland Square, on Providence’s East Side, will survive.

Big and hugely profitable hospital chains such as Mass General Brigham are also acting to get more affluent, well-insured customer/patients by setting up mini hospitals in rich suburbs. That raises questions about what happens to the quality of care of patients in poor places as more resources are shifted to the suburban land of milk and honey.

‘Endless undulation’

“View Across Frenchman's Bay from Mount Desert Island After a Squall’’ by Thomas Cole (1845)

“There are times when a man wants solitude, and particularly this is so when he is watching the endless undulation of the sea.’’

— Dudley Cammett Lunt (1896-1981) lawyer and writer, in The Woods and the Sea: Wilderness and Seacoast Adventures in the State of Maine. He was born in Portland, Maine, but lived most of his life in Delaware while returning each year for summer vacations in The Pine Tree State.

Have a seat but bring your own cushions

“Bent Bench” (black locust, concrete and stainless steel), by Mitch Ryerson, at the Art Complex Museum, Duxbury, Mass.

The museum explains:

”As part of our 50th anniversary celebration {this year} we held a call for artists for outdoor seating. Mitch Ryerson was one of five artists we chose to create benches to be placed in our newly landscaped woodland path. Mitch is an artist, designer and craftsperson specializing in wood structures and furniture. He began his career building wooden boats in Maine.’’

Todd McLeish: Small rodents play important roles in maintaining woodland ecosystems in N.E.

Female White-Footed mouse on sumac bush.

— Photo by Peterwchen

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

When University of Rhode Island teaching professor Christian Floyd brought students in his mammalogy class to a nearby forest in September to set 50 box traps to capture mice and other small mammals, he was surprised the next morning when more than half of the traps contained a live white-footed mouse.

“I usually expect to catch three or four, and on a good year we’ll get about 12, but you never get 50 percent trap success,” URI’s rodent expert said. “White-Footed Mouse populations fluctuate in boom and bust years, and this year seems to be a boom year.”

Floyd speculated that abundant acorns, recent mild winters and healthy growth of concealing vegetation were probably factors in the unusual numbers of mice captured this year. But whatever the reason for their abundance, healthy mouse populations are a good sign for local forests.

A new study by scientists at the University of New Hampshire concluded that small mammals such as mice, voles, shrews and chipmunks play a vital role in keeping forests healthy by eating and dispersing the spores of mushrooms, truffles, and other fungi to new areas.

According to Ryan Stephens, the post-doctoral researcher at UNH who led the study, all trees form a mutually beneficial relationship with fungi. Healthy forests are dependent on hundreds of thousands of miles of fungal threads called hyphae that gather water and nutrients and supply it to the trees’ roots. In return, the trees provide the fungi with sugars they produce in their leaves. Without this symbiotic relationship, called mycorrhizae, forests would cease to exist as we know them.

Different fungal species enhance plant growth and fitness during different seasons and under different environmental conditions, so maintaining diverse fungal communities is vital for forest composition and drought resistance, according to Stephens.

But fungal diversity declines when trees die because of insect infestations, fires and timber harvests. That is why the role of small mammals in dispersing mushroom spores is so critical to forest ecology.

To effectively support healthy forests, Stephens said these animals must scatter spores of the right kind of fungi in sufficient quantities and to appropriate locations where tree seedlings are growing. But not every kind of small mammal disperses all kinds of spores, so it’s imperative that forest managers support a diversity of mammal species in forest ecosystems.

“By using management strategies that retain downed woody material and existing patches of vegetation, which are important habitat for small mammals, forest managers can help maintain small mammals as important dispersers of mycorrhizal fungi following timber harvesting” and other disturbances, Stephens said. “Ultimately, such practices may help maintain healthy regenerating forests.”

Distributing mushroom spores isn’t the only important role played by mice and voles in the forest environment. They are also tree planters.

“Almost all rodents cache food — they have a cache of acorns, seeds, maybe truffles, little bits of mushrooms,” Floyd said. “Our oak forests are probably all planted by rodents. They scurry around and dig holes and bury things.”

White-Footed Mice, which Floyd said are the most abundant mammal in Rhode Island, are also voracious consumers of the pupae of gypsy moths.

“For a mouse, gypsy moth pupae are like little jelly donuts; they’re a delicacy,” he said. “The theory is that when mouse numbers are high, they can regulate gypsy moth populations.”

Mice, voles, shrews and chipmunks are also the primary prey of most of the carnivores in the forest, from hawks and owls to foxes, weasels, fishers, and coyotes. These small mammals are a vital link in the food chain between the plant matter they eat and the larger animals that eat them.

Are these small mammals the most important players in maintaining healthy forests? Probably not. Floyd believes that accolade probably goes to the numerous invertebrates in the soil. But this new research on the dispersal of mushroom spores by mice and voles may move them up a notch in importance.

Todd McLeish is an ecoRI News contributor.

David Warsh: When I started to swim into the history of inflation

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

A deft headline last week on a Businessweek cover-story about inflation – “the fear is real but maybe the monster isn’t” – reminded me of the recession winter of 1974-1975, when the editor of Forbes, Jim Michaels, asked me to write a story about whether the spiraling inflation of the 70s might someday suddenly stop. Michaels was well-known for doing things like that

I was new on the job, fresh out of college, acutely conscious of the fact that I hadn’t taken Economics 101 while studying all kinds of other social-science stuff. My thoughts turned at once to measurement.

I found what I was looking for downstairs in the library: a volume of essays from the journal of the Economic History Society, and, in it, an article by E.H. Phelps Brown and Sheila Hopkins – “Seven Centuries of the Prices of Consumables, Compared with Builders’ Wage-Rates.”

I can’t offer picture of the key graphic, “Price of a composite unit of consumables in Southern England 1264-1954,” unless you have access to it here on JSTOR. Happily, though, history professors at the University of Oregon have neatly abstracted the key information here. In the current circumstances, it is definitely worth a look.

A couple of sharp spikes in prices occurred in the 14th Century, each of them relatively quickly reversed. One was apparently associated, at least in time, with the great famine of 1315-1317; the other with the Black Death, a flea-borne plague that had originated in Asia. These short-lived price disturbances were followed by 150 years of relative stability, before at the 16th Century the price of the cost-of-living composite began a steady ascent.

This unprecedented period of rising prices ended two centuries later in southern England, around 1700, but the cost of living in the specified fashion never again return to anything like its former level. The 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries presented smaller puzzles of their own. But adding, roughly, the price increases of the twenty years since 1954, and assuming, for the sake of argument, that measured prices might not return to their pre-1914 level, the only experience in those 725 years of a magnitude similar to the years after World War II were those of the unreversed surge in the money cost of living in the 15th and 16th centuries.

That was my introduction to the “price revolution” of the 17th Century, or “the Tudor inflation,” as Phelps Brown and Hopkins had called it.

Those articles led me on a merry chase, first to two scholars of the period of interest, both at the University of Chicago. It turned out that the facts of the price revolution were well-established, and had been understood in a certain way since Jean Bodin, in 1556, first pointed to the influx of New World gold and silver.

In 1934, Earl J. Hamilton published American Treasure and the Price Revolution in Spain, 1501-1650; in 1940, John Nef had produced Industry and Government in France and England 1540-1640, followed ten years later by War and human progress: an essay on the rise of industrial civilization.

I called and found Hamilton at work at his desk, In the course of a lengthy conversation about various differences of opinion about the cause of changes in money prices, he pointed me toward Joseph Schumpeter’s posthumously published History of Economic Analysis (1954). I bought a copy in a shop around the corner for what then seemed like an extravagant price, $10.

I didn’t phone Nef, who was retired and living in Washington, D.C. I had learned from his autobiography, Search for Meaning; the autobiography of a nonconformist (1973), that he had engaged in a disagreement with Frederick Hayek, his colleague on Chicago’s Committee on Social Thought, as to whether, in Nef’s opinion, economic doctrines posed a greater threat to Christianity, than, in Hayek’s view, “scientism” posed to economics. That seemed too rich for me.

I learned from Schumpeter that economists for centuries had differed among themselves about the virtues of “real” vs. “monetary” analysis. Real analysis, he wrote, maintains that all the essential phenomena of economic life “are capable of being describe in terms of goods and services.…” In this view, he continued, money is considered simply a “veil,” a technical device adopted to facilitate transactions. Monetary analysis, on the other hand, denies that money is of secondary importance in understanding economic processes.

We need only observe the course of events during and after the California gold discoveries to satisfy ourselves that these discoveries were responsible for a great deal more than a change in the unit of account in which values are expressed. Nor have we any difficulty in realizing – as did A. {Adam}Smith – that the development of an efficient banking system may make a lot of difference to the development of a nation’s wealth.

Thus did the price revolution and Schumpeter lead me to Adam Smith, and I have been reading him on these topics, on and off, ever since.

As it happened, Andrew Skinner, of the University of Glasgow, was in Manhattan the next year, promoting the six-volume Oxford commemorative edition of Smith’s works that he had co-edited. With a wink and nudge, Skinner also suggested I buy the two-volume edition of Sir James Steuart’s An Inquiry into the Principles of Political Economy that he had prepared for the Sottish Economic Society. I’ve always been glad that I did.

It was about then, too, that I read Douglas Vickers article on “Adam Smith on the Status of the Theory of Money” in the Skinner-edited volume, Essays on Adam Smith, with its discussion of “the enigma of Smith’s view of the relative unimportance of money in the explanation of the monetary economy….” And the year I began reading Milton Friedman.

Three years after that, Paul Volcker, as chairman of the Federal Reserve Board engineered an experiment in the role of money in monetary economies whose implications continue to be widely explored.

Ever since then, I have been deeply interested in central bankers and what they do. Not long after Volcker left office, An economist friend casually remarked that people who come to economics from the outside (he meant people like me) are either drawn into its orbit or go flying off on their tangent, never to return. I had been drawn in.

I have also come to believe that macroeconomists and central bankers themselves don’t completely understand the science behind what they do well enough to explain it to themselves, much less to the rest of us, though they clearly possess much technological knowledge. If that is the cases, great opportunities await theorists an applied economists alike. Central bankers, meanwhile, are left having to continue to muddle through.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

Chris Powell: Scenes from Weimar America; how about neither senile nor crazy, neither far left nor far right?

Adolf Hitler and his followers in 1932, the final year of the Weimar Republic (1919-1933). Genocide and world war followed.

Right-wing vigilante Kyle Rittenhouse shows his stuff.

Car lot destroyed by Kenosha rioters.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

With proto-Nazis and proto-Commies brawling in the streets across Weimar America, it may be more important than ever to recall Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter's wry observation that "the safeguards of liberty have been forged in controversies involving not very nice people."

At best Kyle Rittenhouse is a stupid and reckless kid and a gun nut who enlisted in a search for trouble and found it in Kenosha, Wis., among rioters, some of them armed, who purported to be enraged by the shooting of a Black man by local police.

Carrying a military-style rifle, Rittenhouse went to Kenosha in the name of protecting property against rioters and ended up killing two of them and maiming a third, all of them white, as Rittenhouse himself is.

Rittenhouse was vigorously prosecuted but, supported by video evidence and even the testimony of a prosecution witness, he maintained that the three men he shot were attacking him, and the jury acquitted him.

Now, because the rioters Rittenhouse shot were rioting in the name of a Black man, the political left is portraying them as martyrs and Rittenhouse as a white supremacist, though there is no evidence that racial oppression was or has ever been his objective. This unfairness to Rittenhouse has prompted the political right to declare him a hero of the right of self-defense and the Second Amendment.

But there were no martyrs or heroes in the brawling in Kenosha, just idiots. When politics is stripped away, Rittenhouse's acquittal fits the facts as the jury could have found them, and if the political left and right were not so crazed and hateful they would be looking for heroes elsewhere.

Of course that's not likely to happen. Instead the Rittenhouse case is inspiring protests and confrontations throughout the country, including Connecticut, where a week ago a group that had been threatening to level the Amazon warehouse in Windsor because ropes resembling nooses had been found there began blocking traffic in the center of Manchester.

Blocking traffic is a good way of looking for trouble too, especially when so many people are stressed and on edge because of the lengthy virus epidemic. People protesting in the name of environmental protection lately have been blocking traffic in the United Kingdom and getting attacked by people trying to get to work.

So as the Rittenhouse verdict protesters were blocking traffic in Manchester, a car stopped in front of them and then slowly pushed through them before driving off. The protesters were able to get out of the way and no one was really hurt, but they all were indignant that their lawbreaking wasn't appreciated but instead was resented as a provocation.

Indeed, some of them are gun nuts just like Rittenhouse and have carried and displayed guns at their previous protests, though no one has been threatening them. In Manchester last weekend they claimed to be armed as well and seemed to want to be considered heroes for not shooting at the car that had nudged them out of the way.

There is good identification of the car and if the police locate and arrest the driver maybe Manchester will be the scene of another trial to which racial implications will be falsely and opportunistically attached. As in Kenosha, MSNBC and Fox News could cover it and designate new heroes and villains, and the verdict could set off its own protests and riots.

Or maybe, realizing that there are still many more civilized ways to make a point, people could resolve to make their points without getting into each other's faces, even if that is less dramatic and satisfying to the ego.

xxx

A national poll three years ago found that nearly half the country questioned President Trump's mental stability and intelligence. Now another national poll has found that about half the country questions President Biden's mental fitness for his office and believes that his health is deteriorating.

Unfortunately, other polls say Vice President Kamala Harris's standing with public opinion is even worse.

So the next act of politics in Weimar America may be the restoration of Trump, unless someone soon can start a sensible third party whose platform might be simple:

Neither crazy nor senile, neither far left nor far right.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Post-season

"Work Horse" (acrylic on birch panel), by Alan Bull, a Newburyport, Mass.-based artist. Now on view at Battle Grounds Coffee Co., Newburyport. See The Art of Alan Bull.

Grave matters

Part of the Ancient Burying Ground in Hartford, with the First Church of Christ (aka Congregational), the congregation's fourth church, built in 1807, next to it. The cemetery, which dates back to 1636, was the city's sole cemetery until 1803.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24

New England Cemeteries: A Collector’s Guide, by Andrew Kull, is extensive (260 places!) and honest. He describes ugly and badly maintained and even abandoned graveyards as well as such grand, gorgeous 19th Century “garden cemeteries’’ as Providence’s Swan Point Cemetery and Mt. Auburn Cemetery, on the Cambridge-Watertown line, just outside of Boston.

Some are ancient, by American standards, with the oldest probably at Cole’s Hill, in Plymouth, Mass. (1620), and King’s Chapel Burying Ground, in Boston, dating to 1630.

Mr. Kull notes:

“People who have never paid much attention to the subject tend to think that one graveyard is much like another. In some parts of the country this is undoubtedly the case. In New England, a longer history has included changing attitudes toward death and its proper commemoration.’’

I love some of the gravestone inscriptions Mr. Kull quotes, such as this on the grave of Samuel Stone (who died in 1663) in Hartford’s Ancient Burying Ground (1636):

“Errors corrupt by sinnewous dispute

He did oppugne, and clearly them confute:

Above all things, he Christ his Lord prefer’d

Hartford! Thy richest jewel’s here interd.’’

This book was published way back in 1975 but I think it still holds up as a guide to many places, lovely or not, that inspire reflection about transitory lives and the sweep of history. Vermont native Mr. Kull (also a distinguished legal scholar) was born in 1947. But he isn’t yet a resident of a cemetery.

In Mt. Auburn Cemetery

‘Playground’

From Jennifer Moses’s show “Rock, Paper, Scissors” (gouche on paper), at Kingston Gallery, Boston, Dec. 1-Jan. 16.

The gallery says from her statement:

“…. Moses explores a playground game literally and metaphorically. This classic game of chance and anticipation is designed to negotiate conflicts, make decisions, and establish power; rock dominates scissors, paper binds rock, and scissors cut paper. The game is also a metaphor for art-making, in which one aesthetic or conceptual choice supplants another. This kind of improvisational response is a signature of Moses's approach to constructing images.’’

‘Uncaged and free’

View of Mission Church and the Boston skyline from near the top of Mission Hill. Mission Church is the popular name of the Basilica and Shrine of Our Lady of Perpetual Help, a Roman Catholic basilica. The Redemptorists of the Baltimore Province have ministered to the parish since the church was opened, in 1870.

“Down around here positive minds meet; Plotting dreams into plans that manifest into beats; Well here you got a problem speak it coolly and calmly; Cause we're supporting those with evolved mentalities; Boston here fluent in stroll; The people's confidence is full in control; You'll find me at 42 longitude 71 latitude; Only European-style city in the US man; It's arguable Jamaica Plain, Mission Hill, my worn out sneaks; Just hanging out on rooftops uncaged and free”

—From the song “Down Around Here” by Big D and the Kids Table (2009)

‘Blue and bluer still’

Welcome to Boston!

“When the cold comes to New England it arrives in sheets of sleet and ice. In December, the wind wraps itself around bare trees and twists in between husbands and wives asleep in their beds. It shakes the shingles from the roofs and sifts through cracks in the plaster. The only green things left are the holly bushes and the old boxwood hedges in the village, and these are often painted white with snow. Chipmunks and weasels come to nest in basements and barns; owls find their way into attics. At night, the dark is blue and bluer still, as sapphire of night.”

—Alice Hoffman (born 1952), Boston-based novelist, in Here on Earth.

The plot involves a woman named March Murray, who returns with her teenage daughter to the small Massachusetts town where she grew up, in a story inspired by the 1847 Emily Brontë novel Wuthering Heights. In the town, March is reunited with the boy she fell in love with years before. But, "{I}n heaven and in our dreams, love is simple and glorious. But it is something altogether different here on earth.…"

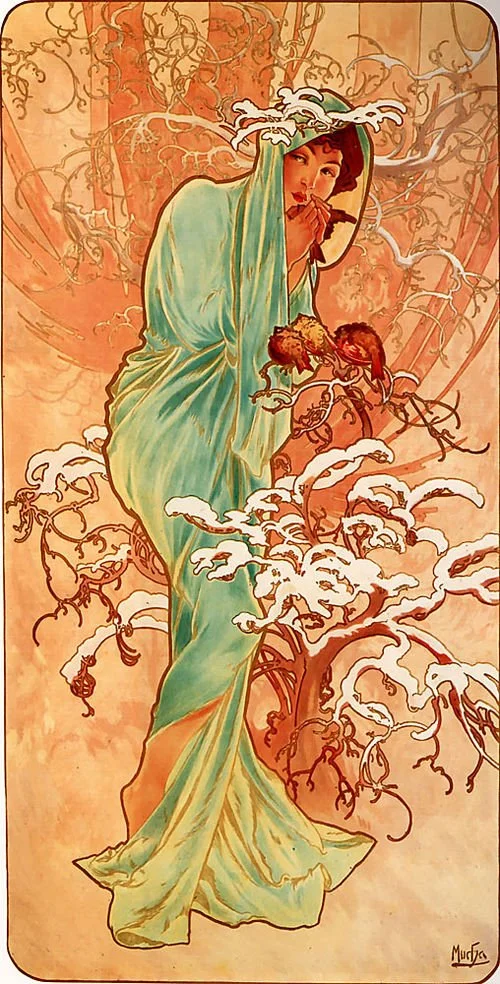

“Winter,” by Alfons Mucha (1896)

A raging ‘diminutive jock’

Coxswain, at the right and yelling, at the Head of the Charles (River) Regatta.

“In crew, contempt is important. In Boston, Boston University and Northeastern crew are treated with contempt by the college up the river. Intramural crew is treated with contempt. Nonathletic coxswains (Chinese engineering majors, poets) are treated with contempt. A true coxswain is a diminutive jock, raging against the pint size that made him the butt of so many jokes at Prep school. He runs twenty stadiums a day, his girlfriend is six feet one, and he can scream orders even when he has the flu (which he catches at least three times a winter).”

— From The Official Preppy Handbook, by Lisa Birnbach

Memory and dream ‘in transit’

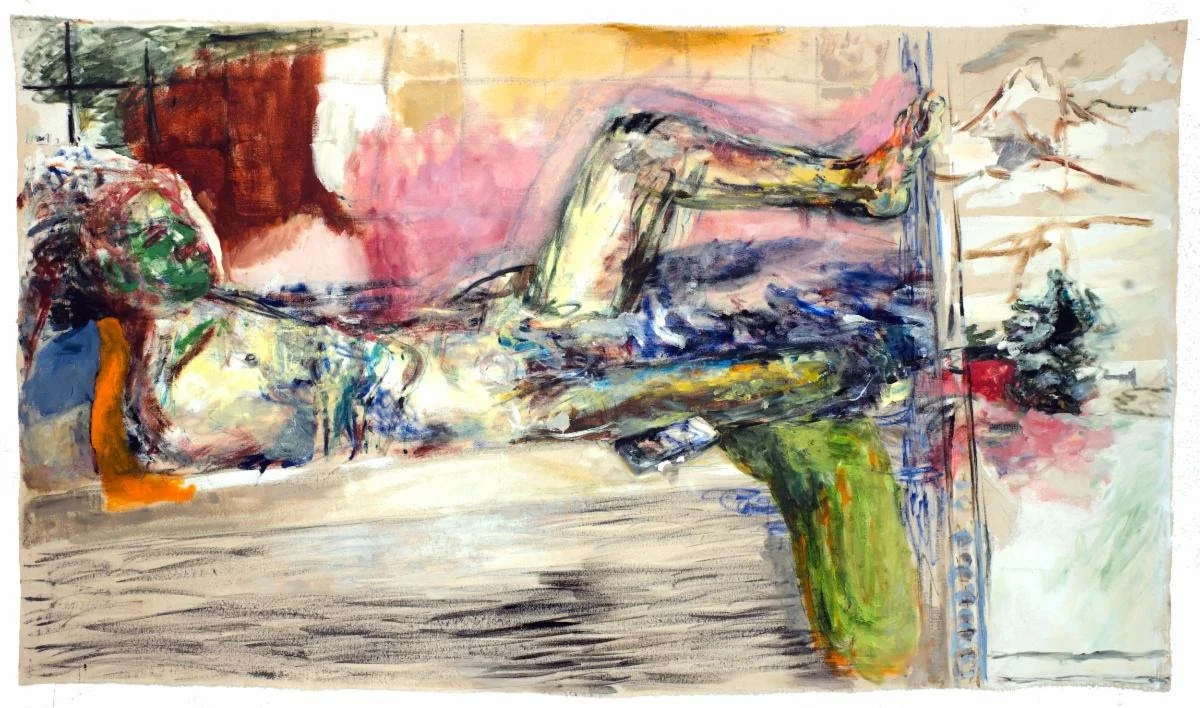

“Allan in Bathtub” (oil and mixed media on unstretched canvas), by Alexandra Thompson, in her show “Returning Trains,’’ at Gallery 444, Provincetown, Mass., through Dec. 6.

The gallery says:

“In paint, sculpture and drawing, {she creates a} landscape of memory and dream in transit between the Midwest and the Atlantic…’’ employing “a rawness of material and image.’’

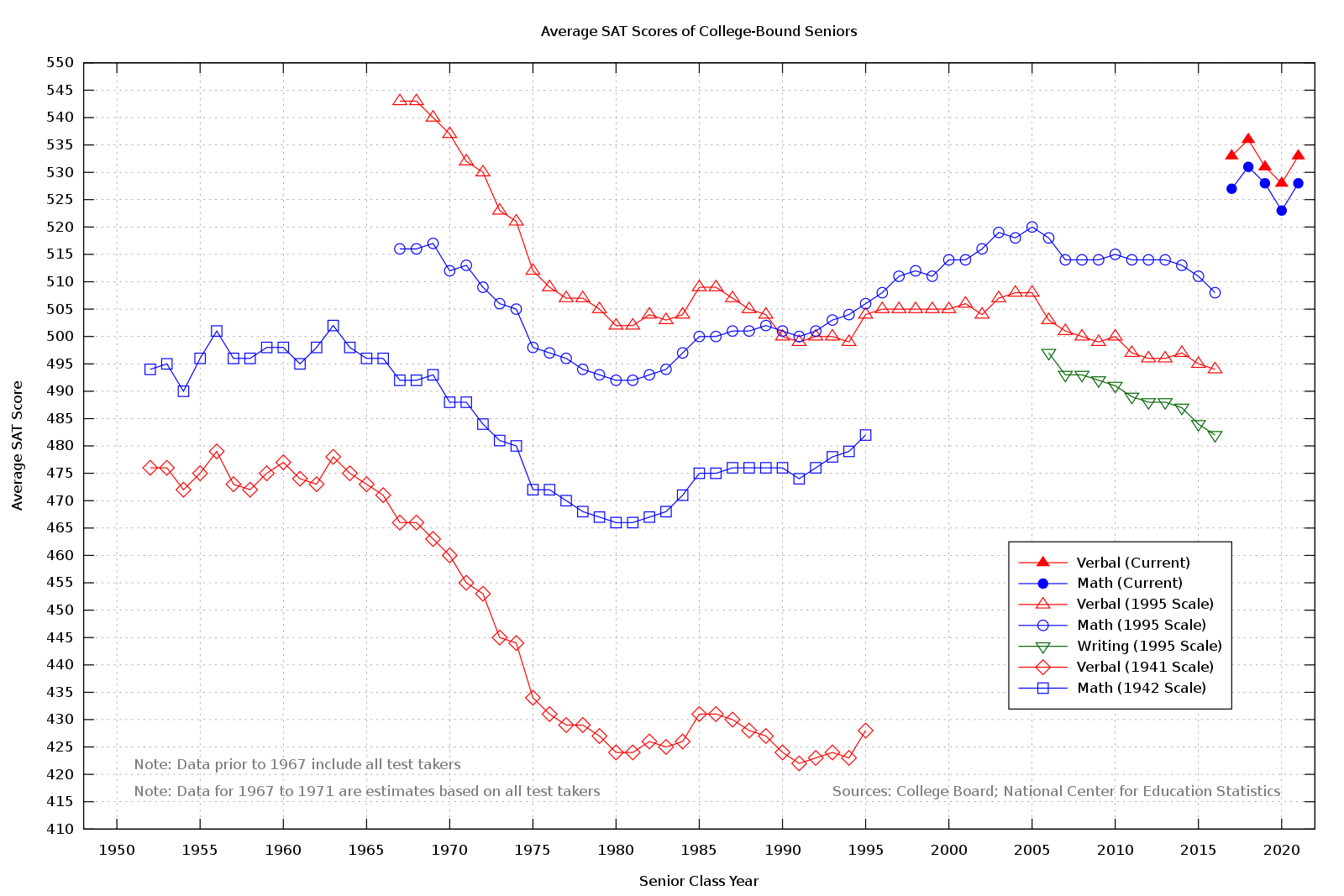

Josh M. Beach: Why we can’t measure what matters in U.S. education

Via The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

What do students learn in school? In the 21st Century, this question has become a political dilemma for countries around the globe. It is a deceptively simple question, but there has never been an easy answer.

The problem of measuring student learning appears to express an educational problem: What and how much do students learn? And yet, when you investigate the education-accountability movement, especially in the U.S. where it began, you realize that the preoccupation with student learning is not about education. Calls for accountability have always been more focused on politics and economics.

Accountability metrics were created to sort and rank students, teachers and schools in order to create a competition where some are winners and most are losers. This type of competitive environment creates fear, and it is not conducive to learning or high performance.

Most student learning, especially the most important types of social learning and formative interactions, happens outside school, especially in early childhood. These personal experiences later go on to affect students’ performance in schools. The most important variables that affect a student’s school achievement are environmental. They occur outside schools and affect children long before they ever set foot in a school. These three variables, which are deeply intertwined, are the social construction of: race, parental income and wealth, and parental education (especially the highest level of schooling that parents achieve).

All three of these variables are proxies for a wide range of social and economic resources that can help students learn and succeed in school, such as parenting skills and child development, especially the time parents spend talking to and reading with children, proper nutrition, access to tutors and extracurricular activities, access to top-quality schools with the best teachers, and also peer networks.

Most policymakers and school administrators talk as if schools and teachers have complete control over the student learning process, but most of the important variables that determine student success, especially in terms of learning and graduating, are beyond the control of teachers or schools.

As W. Edwards Deming pointed out, “Common sense tells us to rank children in school (grade them), rank people on the job, rank teams, divisions … Reward the best, punish the worst.” (This common-sense belief is wrong, especially, as Deming emphasized, when it comes to schooling, where the objectives are supposed to be student learning and personal development.)

Over the past half century, social scientists have found that there can be many unintended and adverse consequences when high-stake metrics get linked to individual or institutional evaluations tied to punishments and rewards.

This predicament is often called Campbell’s Law. The psychologist and social scientist Donald T. Campbell explained in 1976, “The more any quantitative social indicator is used for social decision-making, the more subject it will be to corruption pressures and the more apt it will be to distort and corrupt the social processes it is intended to monitor.”

A British economist put it more bluntly in what is now called Goodhart’s Law: “Any measure used for control is unreliable.”

According to Campbell, “When tests scores become the goal of the teaching process, they both lose their value as indicators of educational status and distort the educational process in undesirable ways.”

How have accountability measurements corrupted schools? Take high-stakes standardized testing as a perfect example. Many teachers now spend most of their classroom time teaching to the tests by giving students “tricks” to answer multiple-choice tests or “ways to game the rules used to score the tests,” according to Harvard Graduate School of Education Prof. Daniel Koretz. Students engage in little, if any, real or useful learning.

Grade inflation

Teachers have also been lowering their standards and inflating grades to make students look much more successful academically than they actually are. Some administrators have been manipulating the tested population of students to make sure the lowest-performing students don’t take high-stakes tests. Sometimes, this has taken the form of transferring low-achieving students to other schools or encouraging them to drop out of school. And most shamefully, some teachers and administrators have been engaging in plain old cheating by falsifying student achievement scores.

To make matters worse, because performance measures cannot be verified, judgments of quality are made on existing data, which can be manipulated, or can be partially or wholly fraudulent. This leads to the adverse selection of personnel, whereby deceitful agents who post the best performance markers get rewarded, even though their numbers may be questionable, if not fraudulent.

Often, as Koretz points out, “the wrong schools and programs” get “rewarded or punished, and the wrong practices may be touted as successful and emulated.” The opposite is also true. Honest, hard-working and effective teachers, with true but lackluster performance measures, are passed over for promotion, criticized, sanctioned or fired. Such moral hazards create a perverse Darwinian scenario: Survival of the corrupt.

When performance goals are mandated from above without employee input, subordinates are forced to follow meaningless targets without any intrinsic motivation. Thus, the only incentive for workers to succeed are extrinsic rewards, often money, which leads to shortcuts or fraud to get the monetary reward. Staff begin chasing performance markers for the monetary incentives without knowing about or caring about the fundamental purposes of the organization or the rationale behind accountability goals.

Thus, when it comes to schools, whenever lawmakers or administrators institute a single, predictable measure of academic performance linked to extrinsic rewards, whether it be for students, teachers, or the whole school, someone somewhere will be cheating to game the system.

A 2013 Government Accounting Office report concluded that “officials in 40 states reported allegations of cheating in the past two school years, and officials in 33 states confirmed at least one instance of cheating. Further, 32 states reported that they canceled, invalidated or nullified test scores as a result of cheating.” One scholarly study estimated that “serious cases of teacher or administrator cheating on standardized tests occur in a minimum of 4-5 percent of elementary school classrooms annually.” Temple University psychologist Laurence Steinberg sardonically quipped, “Fudging data on student performance” has been “the only education strategy that consistently gets results.”

Nationwide in the U.S., we are seeing the consequences of this cynical calculation. For decades, researchers have documented rampant social promotion and grade inflation in K-12 schools and in most institutions of higher education. Koretz has argued that grade inflation is not only “pervasive,” but also “severe,” so much so that he argued that this type of subtle cheating is “central to the failure of American education ‘reform.’”

In Houston, as an example, some high schools were officially reporting zero dropouts and 100% of their students planning to attend college, and yet one principal joked, most of her students “couldn’t spell college, let alone attend.” While Texas pioneered accountability reforms in K-12 education, which became national policy through George W. Bush’s landmark No Child Left Behind law, researchers have documented how those reforms led to the corruption of education in Texas. Policymakers and administrators lost sight of education in a push to fudge the numbers so they could secure public accolades, get more funding and build bigger football stadiums.

And what is the impact of grade inflation on students? While students no doubt like high grades that they have not academically earned, they are actually harmed a great deal by such educational fraud. First of all, students become complacent and are unmotivated to learn because they think they already know it all. When students are confronted with higher academic standards in the future, they are liable to wilt under the pressure and either blame themselves or the teacher for the difficulty of authentic learning.

Disadvantaged students hurt most

To make matters worse, grade inflation affects disadvantaged students the most. Poor students and ethnic minorities, who are often segregated in the lowest-performing schools in the poorest neighborhoods, often receive the most inflated grades. This is because their teachers often can’t teach effectively due to various social, economic and environmental conditions that obstruct the learning process.

And what happens when academically underachieving high-school students fail upwards and make it into college, mostly through the open-door community college? They are then confronted with the fact that they are unprepared for academic success.

Large percentages of freshmen in the U.S. have to start college with remedial classes because they were not adequately prepared in high school. Most of these remedial college students eventually drop out of college, for various reasons, never earning a degree, and often with substantial amounts of student debt. However, many are also just passed through the college system with inflated grades and little learning.

For decades, researchers have documented the lowering of academic standards and the inflation of grades at institutions of higher education all across the U.S., especially at community colleges.

Graduating with a degree

High grades also seem to be inversely correlated with the main measure of student success in college, which is graduating with a degree. Currently, over 80% of all college students in the U.S. are earning A or B grades, but less than half of students who enroll in higher education will actually graduate with a bachelor’s degree.

As college admissions rose, graduation rates declined from the 1970s to the 1990s because standards remained relatively high. But as admissions continued to rise, graduation rates began to increase starting in the 1990s. Students were no more academically prepared, in fact, they were less prepared, so the increase in completion rates was mostly likely due to political and administrative pressure. New accountability reforms most likely contributed to a lowering of standards, especially at non-selective public colleges and universities.

Education researchers Ernest T. Pascarella and Patrick T. Terenzini pointed out in 2005 that only about half of all college graduates “appear to be functioning at the most proficient levels of prose, document or quantitative literacy,” which means that all those inflated A and B grades aren’t translating into actual knowledge or skill, putting many college graduates at a disadvantage when they enter the labor market, and putting many firms at risk because they have hired ignorant and incompetent college graduates.

While it is certainly reasonable for teachers to use tests and grades to evaluate and measure student learning, these tools are not easy to implement in a valid way that promotes student learning and development. As Jack Schneider of the University of Massachusetts at Lowell, notes, “Measuring something as complicated as student learning” is very difficult, even under the best of circumstances, but almost impossible when it has to be done in a “uniform and cost-restricted way.” {Mr. Schneider is associate professor of leadership in education at UMass Lowell and director of research for the Massachusetts Consortium for Innovative Education Assessment.}

Josh M. Beach is the author of a number of interdisciplinary titles, including How Do You Know?: The Epistemological Foundations of 21st Century Literacy and Gateway to Opportunity? A History of the Community College in the United States. He is the founder and director of 21st Century Literacy, a nonprofit organization focused on literacy education and teacher training.

Georgian-style Longfellow Hall at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education, in Cambridge, Mass. It’s named for the daughter of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, the famous 19th Century poet and scholar.

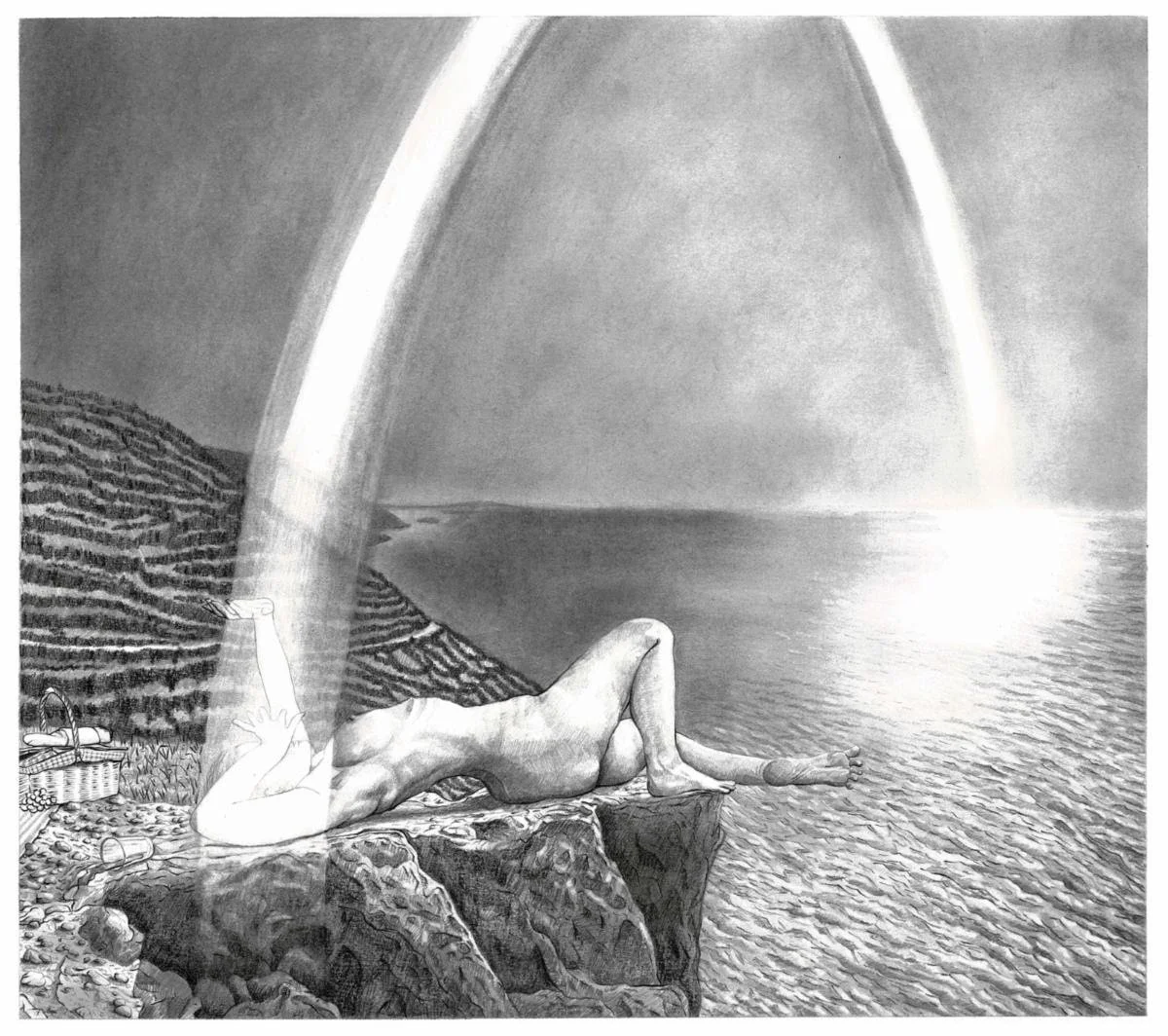

Just me and my landscape

“Light” (graphite and charcoal on paper), by New York-based Catalina Viejo Lopez de Roda, in her show “Self Care’’, at HallSpace Contemporary Art Gallery, in Boston’s Dorchester section, starting Dec. 11. {Editor’s note: This reminds me of the work of Rockwell Kent.}

The gallery says: "Dealing with a persistent virus has instigated a new direction in Viejo’s work, with the central theme being Self Care. A single woman lives in isolation in each of her drawings, paintings and animations. These women inhabit wild environments and have developed a symbiotic relationship with the landscape."

‘It’s not intellectual’

Rock of Ages granite quarry in Graniteville, Vt.

]

“Never confuse faith, or belief — of any kind — with something even remotely intellectual.’’

— From A Prayer for Owen Meany, a novel by John Irving (born 1942)

The plot centers around John Wheelwright and Owen Meany, who live in the fictional town of Gravesend, N.H. (based on Irving’s hometown of Exeter, N.H.). As boys they are close friends, although John comes from an old rich family — as the illegitimate son of Tabitha Wheelwright — and Owen is the only child of a working-class granite quarryman. John's earliest memories of Owen involve lifting him up in the air, easy because of his permanently small stature, to make him speak. And an underdeveloped larynx causes Owen to speak in a high-pitched voice. During his life, Owen comes to believe that he is "God's instrument".

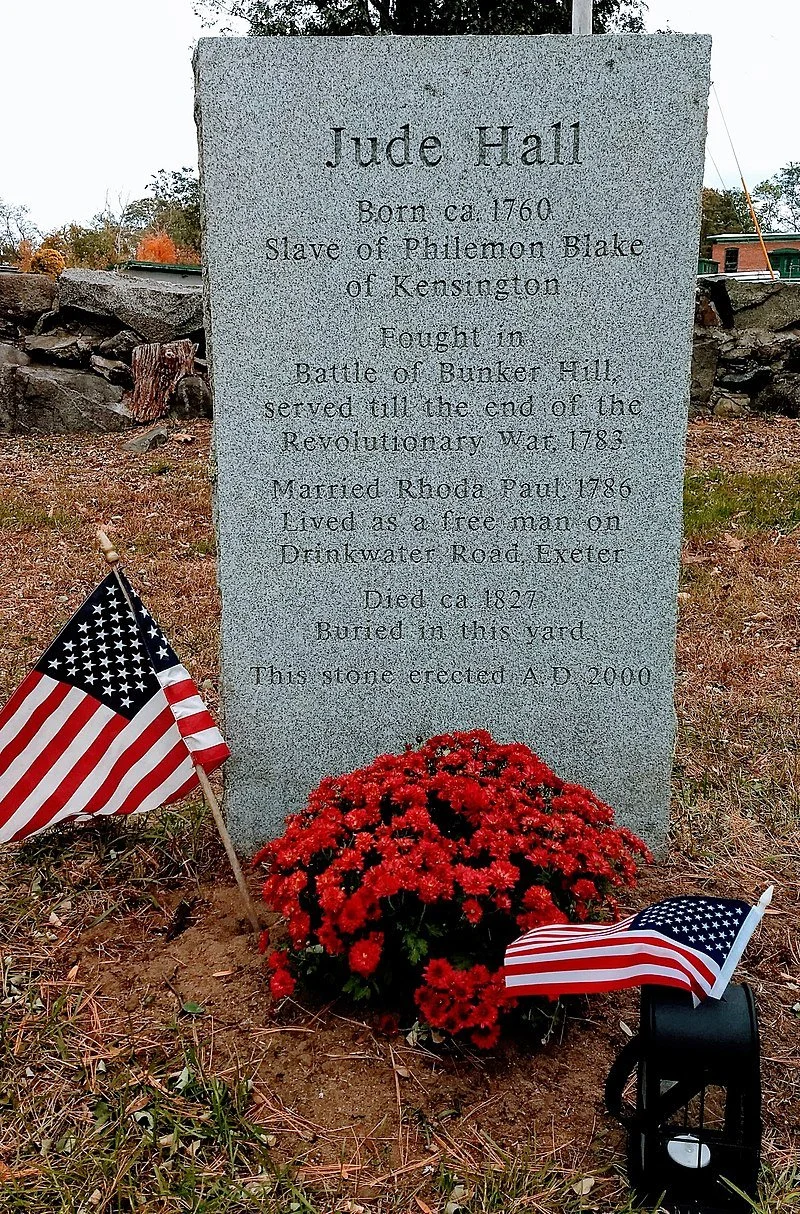

Jude Hall granite memorial stone in Exeter, N.H.

A still, very New England place for reflection, not feasting

On Thanksgiving: In Jaffrey Center, N.H., with Mt. Monadnock in the background. The celebrated novelist Willa Cather is buried in Jaffrey’s Old Burying Ground.

— Photo by William Morgan